Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Recombinant mAb Production

2.3. Animals

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. ADCC

2.6. CDC

2.7. Antitumor Activities in Xenografts of Human Tumors

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

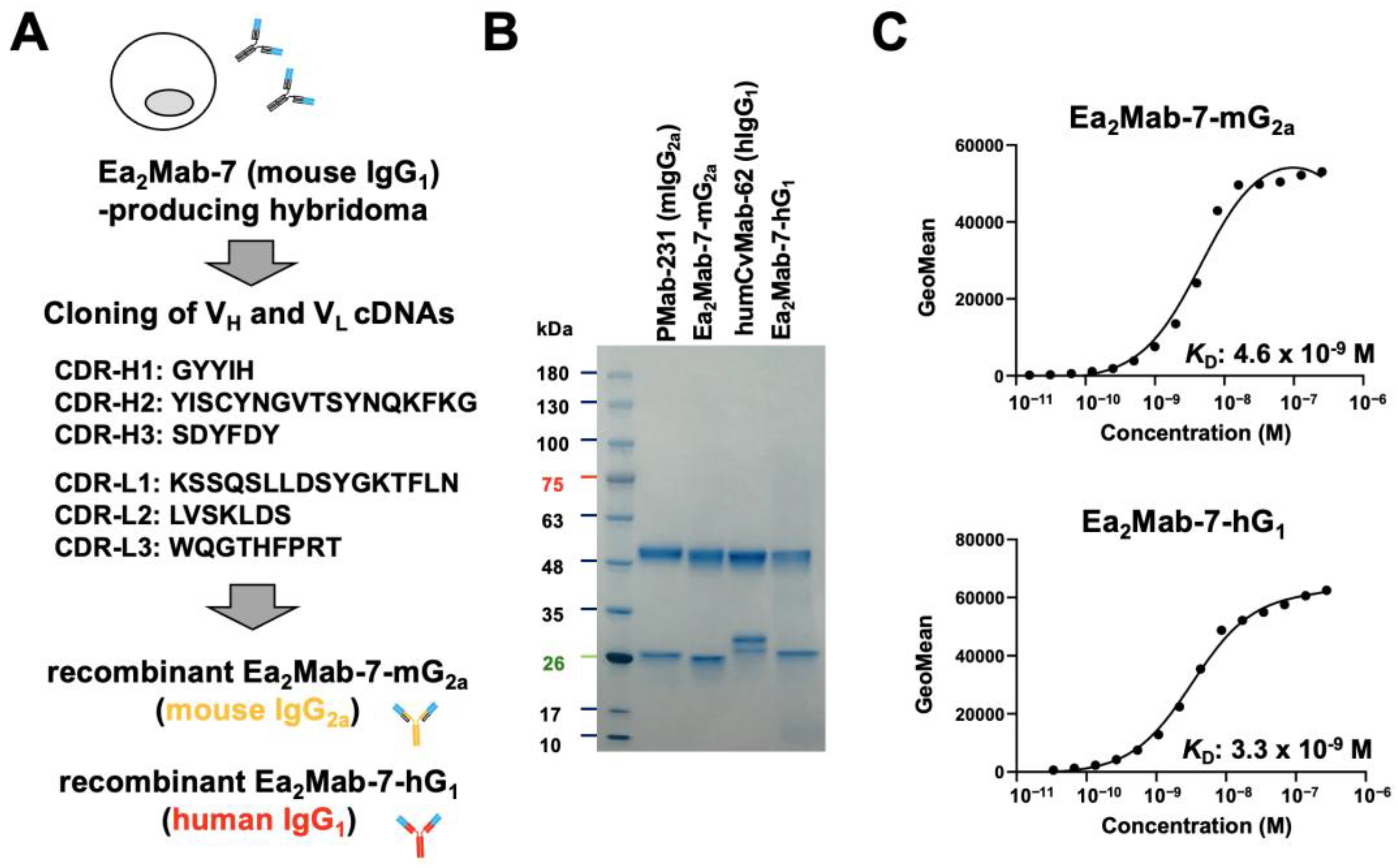

3.1. Production of Class-Switched mAbs from Ea2Mab-7

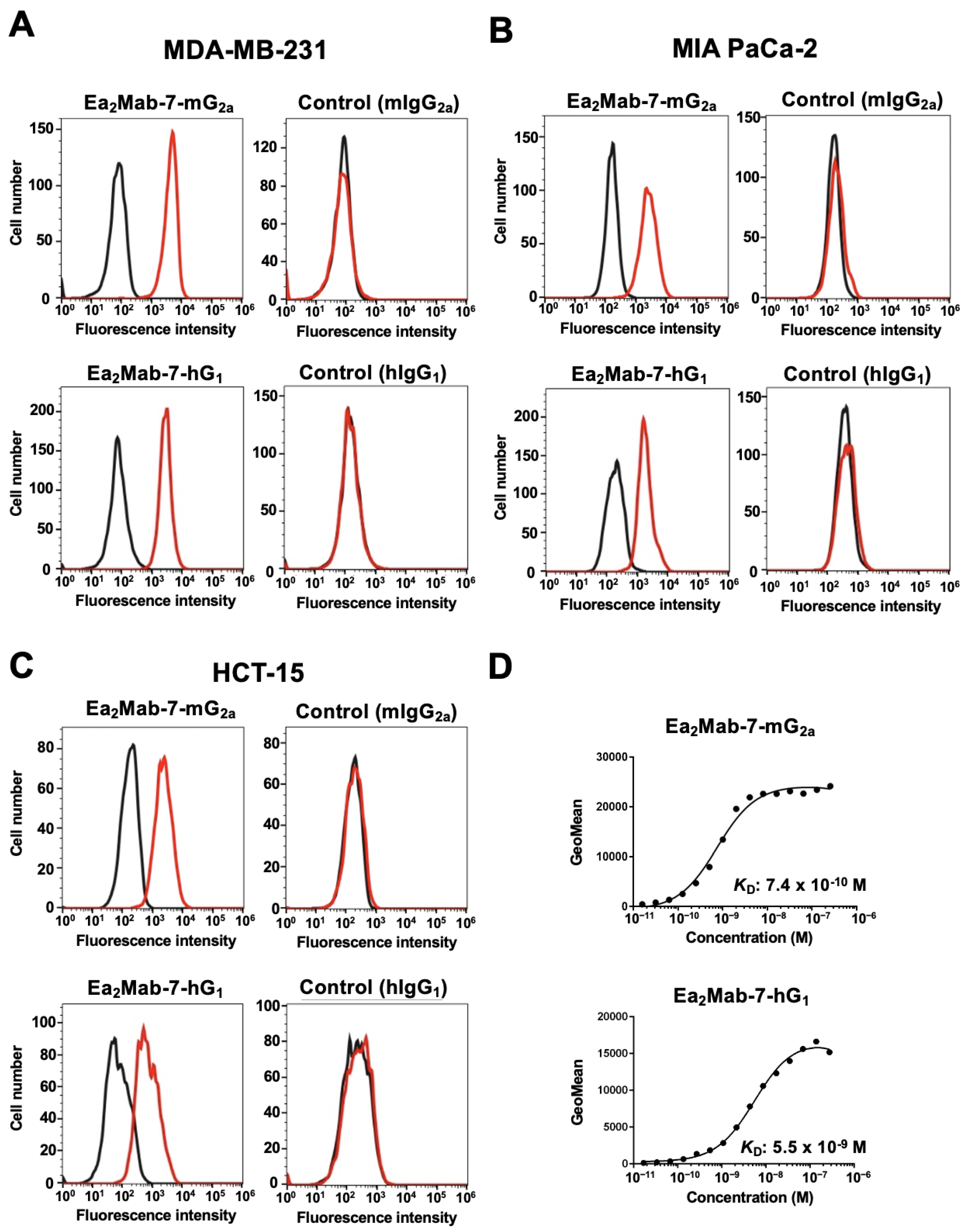

3.2. Flow Cytometry Using Ea2Mab-7-mG2a and Ea2Mab-7-hG1 in EphA2-Positive Cancer Cells

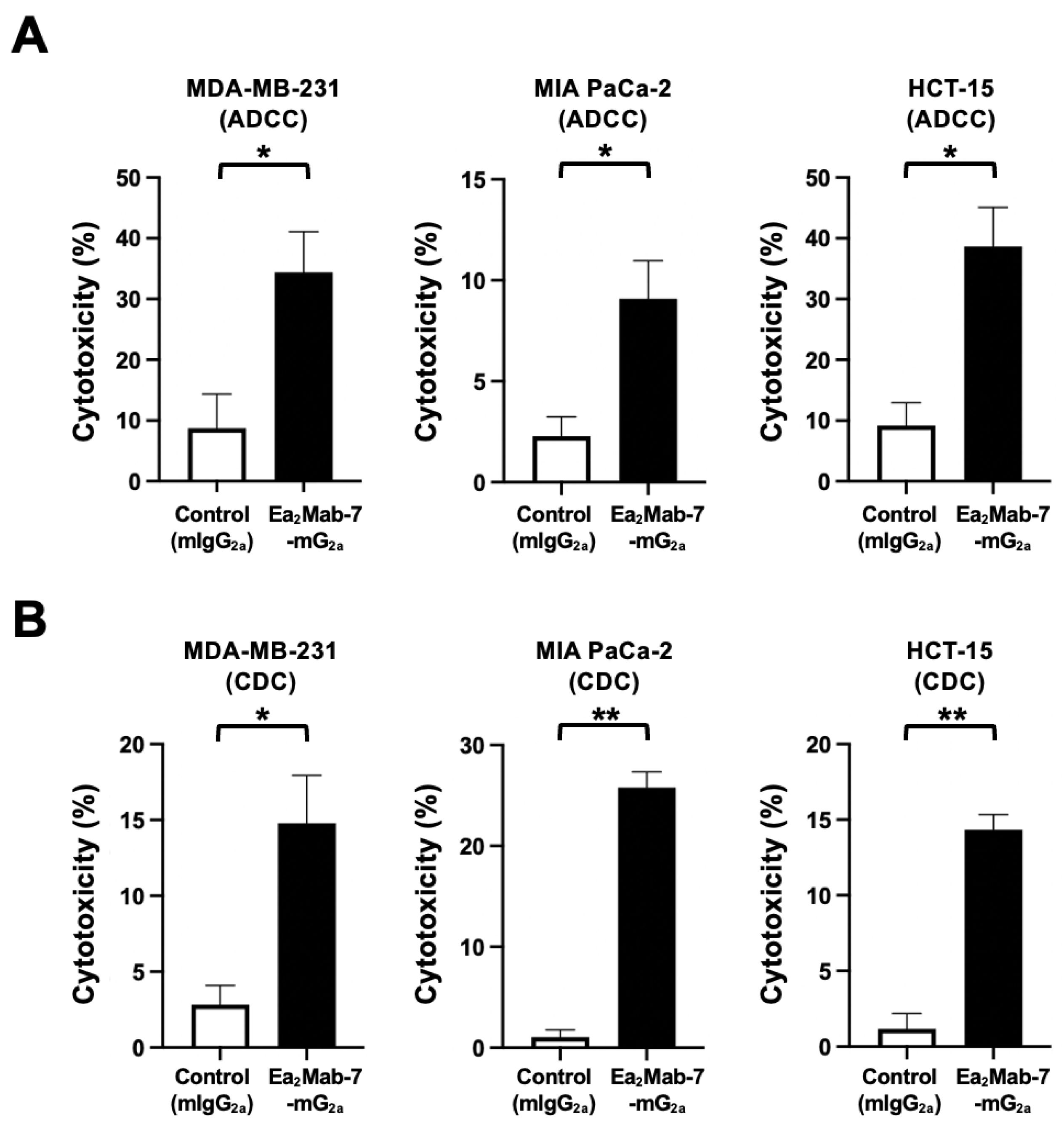

3.3. ADCC and CDC Elicited by Ea2Mab-7-mG2a Against EphA2-Positive Cancer Cells

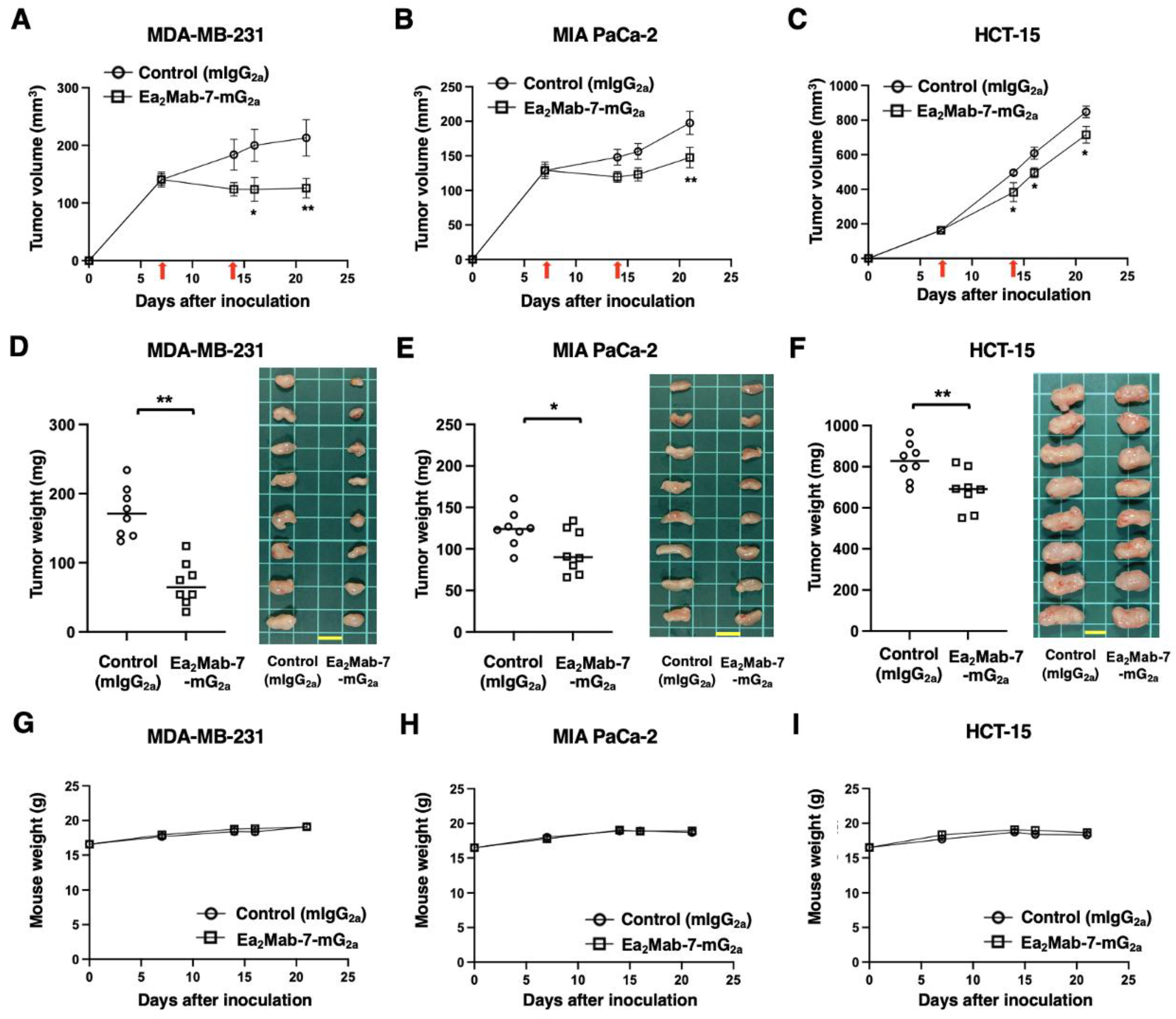

3.4. Antitumor effects of Ea2Mab-7-mG2a Against EphA2-Positive Cancer Cells

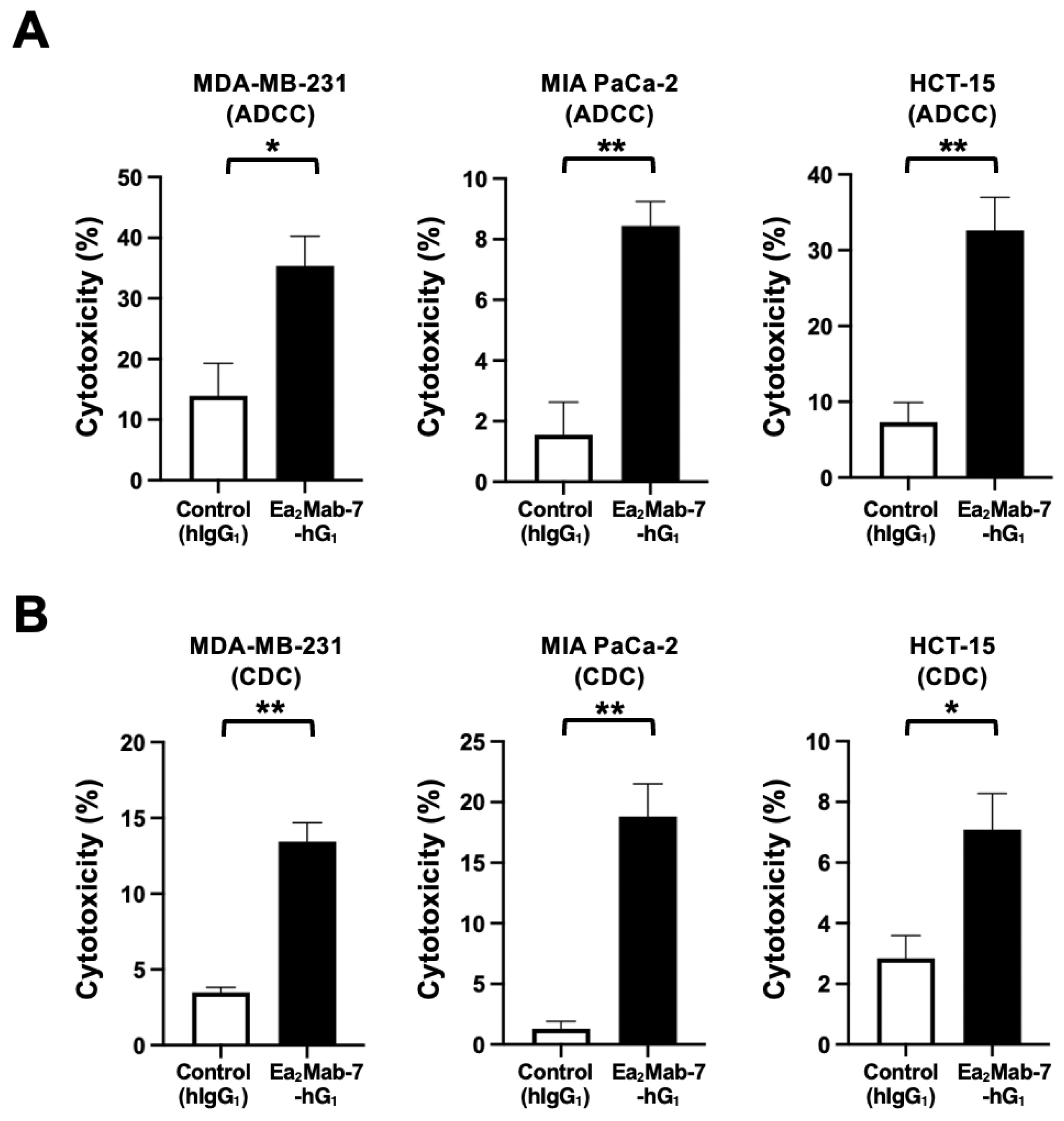

3.5. ADCC and CDC Elicited by Ea2Mab-7-hG1 Against EphA2-Positive Cancer Cells

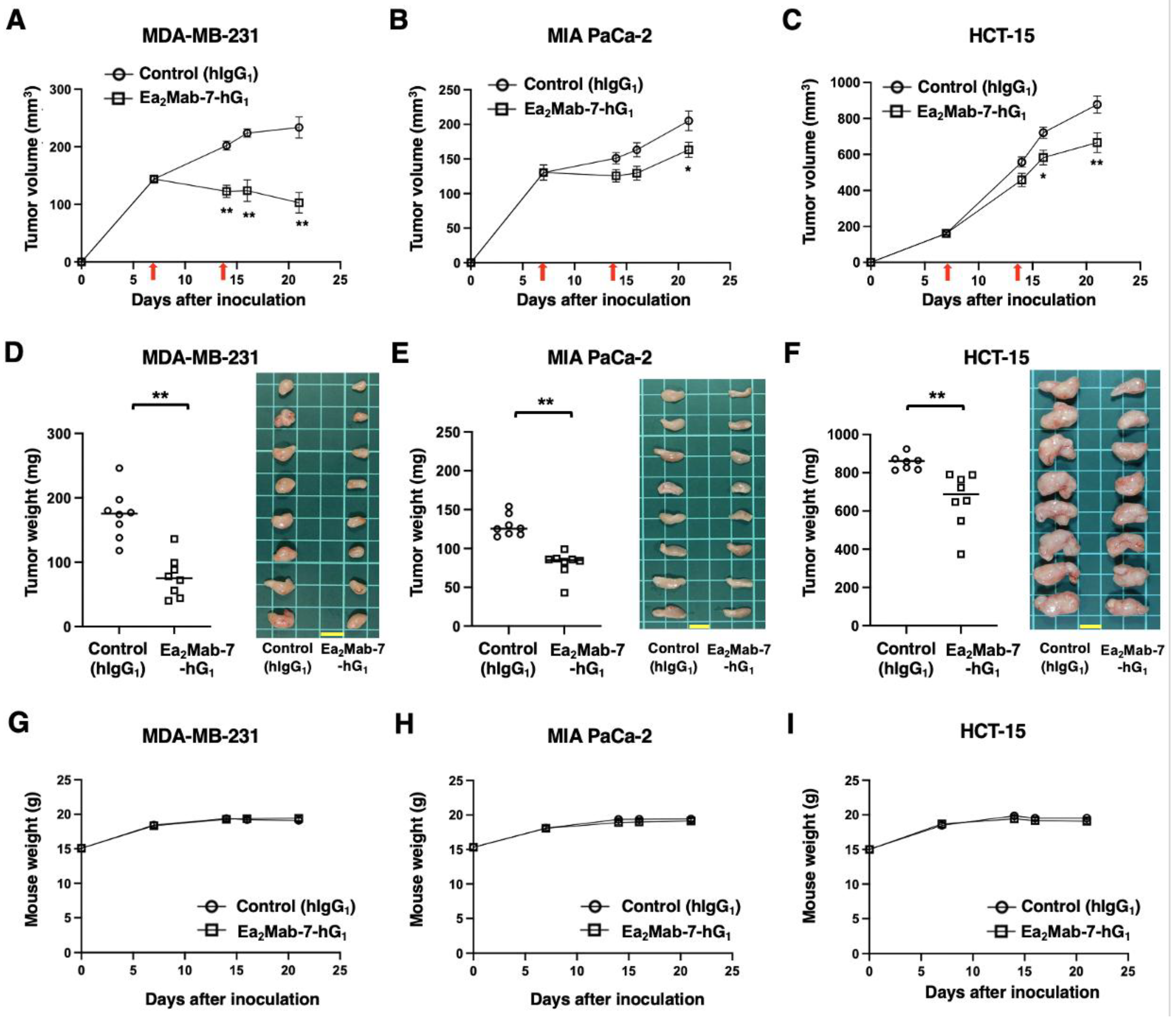

3.6. Antitumor Effects of Ea2Mab-7-hG1 Against EphA2-Positive Cancer Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2024, 24, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Wang, B. EphA receptor signaling--complexity and emerging themes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2012, 23, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell 2008, 133, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Su, S.A.; Shen, J.; Ma, H.; Le, J.; Xie, Y.; Xiang, M. Recent advances of the Ephrin and Eph family in cardiovascular development and pathologies. iScience 2024, 27, 110556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, J.; Schell, B.; Nasser, H.; Rachid, M.; Ruaud, L.; Couque, N.; Callier, P.; Faivre, L.; Marle, N.; Engwerda, A.; et al. EPHA7 haploinsufficiency is associated with a neurodevelopmental disorder. Clin Genet 2021, 100, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, T.; Cong, Y.; Luo, X.; Liu, C.; Gong, T.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-1 competitively blocks Ephrin receptor A2-mediated Epstein-Barr virus entry into epithelial cells. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Li, D.Q.; Mukherjee, A.; Guo, H.; Petty, A.; Cutter, J.; Basilion, J.P.; Sedor, J.; Wu, J.; Danielpour, D.; et al. EphA2 mediates ligand-dependent inhibition and ligand-independent promotion of cell migration and invasion via a reciprocal regulatory loop with Akt. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toracchio, L.; Carrabotta, M.; Mancarella, C.; Morrione, A.; Scotlandi, K. EphA2 in Cancer: Molecular Complexity and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.W.; Bartlett, P.F.; Lackmann, M. Therapeutic targeting of EPH receptors and their ligands. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2010, 10, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechtenberg, B.C.; Gehring, M.P.; Light, T.P.; Horne, C.R.; Matsumoto, M.W.; Hristova, K.; Pasquale, E.B. Regulation of the EphA2 receptor intracellular region by phosphomimetic negative charges in the kinase-SAM linker. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yamada, N.; Tanaka, T.; Hori, T.; Yokoyama, S.; Hayakawa, Y.; Yano, S.; Fukuoka, J.; Koizumi, K.; Saiki, I.; et al. Crucial roles of RSK in cell motility by catalysing serine phosphorylation of EphA2. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquilla, A.; Lamberto, I.; Noberini, R.; Heynen-Genel, S.; Brill, L.M.; Pasquale, E.B. Protein kinase A can block EphA2 receptor-mediated cell repulsion by increasing EphA2 S897 phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell 2016, 27, 2757–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porazinski, S.; de Navascués, J.; Yako, Y.; Hill, W.; Jones, M.R.; Maddison, R.; Fujita, Y.; Hogan, C. EphA2 Drives the Segregation of Ras-Transformed Epithelial Cells from Normal Neighbors. Curr Biol 2016, 26, 3220–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harly, C.; Joyce, S.P.; Domblides, C.; Bachelet, T.; Pitard, V.; Mannat, C.; Pappalardo, A.; Couzi, L.; Netzer, S.; Massara, L.; et al. Human γδ T cell sensing of AMPK-dependent metabolic tumor reprogramming through TCR recognition of EphA2. Sci Immunol 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioce, M.; Fazio, V.M. EphA2 and EGFR: Friends in Life, Partners in Crime. Can EphA2 Be a Predictive Biomarker of Response to Anti-EGFR Agents? Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, K.R.; Wang, S.; Tan, L.; Hastings, A.K.; Song, W.; Lovly, C.M.; Meador, C.B.; Ye, F.; Lu, P.; Balko, J.M.; et al. EPHA2 Blockade Overcomes Acquired Resistance to EGFR Kinase Inhibitors in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraiso, K.H.; Das Thakur, M.; Fang, B.; Koomen, J.M.; Fedorenko, I.V.; John, J.K.; Tsao, H.; Flaherty, K.T.; Sondak, V.K.; Messina, J.L.; et al. Ligand-independent EPHA2 signaling drives the adoption of a targeted therapy-mediated metastatic melanoma phenotype. Cancer Discov 2015, 5, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volz, C.; Breid, S.; Selenz, C.; Zaplatina, A.; Golfmann, K.; Meder, L.; Dietlein, F.; Borchmann, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Siobal, M.; et al. Inhibition of Tumor VEGFR2 Induces Serine 897 EphA2-Dependent Tumor Cell Invasion and Metastasis in NSCLC. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Alam, N.; Sen, S.; Mitra, S.; Mandal, S.; Vignesh, S.; Majumder, B.; Murmu, N. Phosphorylation of EphA2 receptor and vasculogenic mimicry is an indicator of poor prognosis in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020, 179, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vankelecom, H.; Van Eijsden, R.; Govaere, O.; Topal, B. Molecular markers associated with outcome and metastasis in human pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2012, 31, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, P.D.; Dasgupta, S.; Blayney, J.K.; McArt, D.G.; Redmond, K.L.; Weir, J.A.; Bradley, C.A.; Sasazuki, T.; Shirasawa, S.; Wang, T.; et al. EphA2 Expression Is a Key Driver of Migration and Invasion and a Poor Prognostic Marker in Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, W.S.; Kirpotin, D.B.; Huang, Z.R.; Tipparaju, S.K.; Noble, C.O.; Hayes, M.E.; Luus, L.; Koshkaryev, A.; Kim, J.; Olivier, K.; et al. Antitumour activity and tolerability of an EphA2-targeted nanotherapeutic in multiple mouse models. Nat Biomed Eng 2019, 3, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; Gooya, J.; Mao, S.; Kinneer, K.; Xu, L.; Camara, M.; Fazenbaker, C.; Fleming, R.; Swamynathan, S.; Meyer, D.; et al. A human antibody-drug conjugate targeting EphA2 inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 9367–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, J.; Sue, M.; Yamato, M.; Ichikawa, J.; Ishida, S.; Shibutani, T.; Kitamura, M.; Wada, T.; Agatsuma, T. Novel anti-EPHA2 antibody, DS-8895a for cancer treatment. Cancer Biol Ther 2016, 17, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, C.M.; Kohn, E.C.; LoRusso, P.; Houston, N.D.; Coleman, R.L.; Buzoianu, M.; Robbie, G.; Lechleider, R. Phase 1, open-label study of MEDI-547 in patients with relapsed or refractory solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2013, 31, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Lozza, I.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Actively Targeted Nanomedicines in Breast Cancer: From Pre-Clinal Investigation to Clinic. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Satoh, T.; Iwasa, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Muro, K.; Komatsu, Y.; Nishina, T.; Esaki, T.; Hasegawa, J.; Kakurai, Y.; et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the afucosylated, humanized anti-EPHA2 antibody DS-8895a: a first-in-human phase I dose escalation and dose expansion study in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody Ea(2)Mab-7 for multiple applications. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 42, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, M.; Satofuka, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a highly sensitive and specific anti-EphB2 monoclonal antibody (Eb2Mab-12) for flow cytometry. Microbes & Immunity 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a Novel Cancer-Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody H(2)Mab-250/H(2)CasMab-2 for Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kato, Y. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kato, Y. Antitumor Activities of a Humanized Cancer-Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody, humH(2)Mab-250 in Human Breast Cancer Xenografts. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, R.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. EphB2-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies Exerted Antitumor Activities in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Lung Mesothelioma Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Anti-HER2 Cancer-Specific mAb, H(2)Mab-250-hG(1), Possesses Higher Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity than Trastuzumab. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody Ea2Mab-7 for multiple applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overdijk, M.B.; Verploegen, S.; Ortiz Buijsse, A.; Vink, T.; Leusen, J.H.; Bleeker, W.K.; Parren, P.W. Crosstalk between human IgG isotypes and murine effector cells. J Immunol 2012, 189, 3430–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, M.; Hsu, S.; Lewis, G.; Pietras, R.; Beryt, M.; Sliwkowski, M.; Coombs, D.; Baly, D.; Kabbinavar, F.; Slamon, D. Inhibitory effects of combinations of HER-2/neu antibody and chemotherapeutic agents used for treatment of human breast cancers. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2241–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietras, R.J.; Pegram, M.D.; Finn, R.S.; Maneval, D.A.; Slamon, D.J. Remission of human breast cancer xenografts on therapy with humanized monoclonal antibody to HER-2 receptor and DNA-reactive drugs. Oncogene 1998, 17, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, J.; Norton, L.; Albanell, J.; Kim, Y.M.; Mendelsohn, J. Recombinant humanized anti-HER2 antibody (Herceptin) enhances the antitumor activity of paclitaxel and doxorubicin against HER2/neu overexpressing human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 1998, 58, 2825–2831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gan, H.K.; Parakh, S.; Lee, F.T.; Tebbutt, N.C.; Ameratunga, M.; Lee, S.T.; O'Keefe, G.J.; Gong, S.J.; Vanrenen, C.; Caine, J.; et al. A phase 1 safety and bioimaging trial of antibody DS-8895a against EphA2 in patients with advanced or metastatic EphA2 positive cancers. Invest New Drugs 2022, 40, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, G.; Cardone, C.; Vitiello, P.P.; Belli, V.; Napolitano, S.; Troiani, T.; Ciardiello, D.; Della Corte, C.M.; Morgillo, F.; Matrone, N.; et al. EPHA2 Is a Predictive Biomarker of Resistance and a Potential Therapeutic Target for Improving Antiepidermal Growth Factor Receptor Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2019, 18, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markosyan, N.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.H.; Richman, L.P.; Lin, J.H.; Yan, F.; Quinones, L.; Sela, Y.; Yamazoe, T.; Gordon, N.; et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic EPHA2 suppresses anti-tumor immunity by regulating PTGS2 (COX-2). J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 3594–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon-Lowe, C.; Rickinson, A. The Global Landscape of EBV-Associated Tumors. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.S.; Yap, L.F.; Murray, P.G. Epstein-Barr virus: more than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Luo, M.L.; Desmedt, C.; Nabavi, S.; Yadegarynia, S.; Hong, A.; Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Gabrielson, E.; Hines-Boykin, R.; Pihan, G.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Infection of Mammary Epithelial Cells Promotes Malignant Transformation. EBioMedicine 2016, 9, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathmanathan, R.; Prasad, U.; Sadler, R.; Flynn, K.; Raab-Traub, N. Clonal proliferations of cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus in preinvasive lesions related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1995, 333, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutt-Fletcher, L.M. Epstein-Barr virus entry. J Virol 2007, 81, 7825–7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sathiyamoorthy, K.; Zhang, X.; Schaller, S.; Perez White, B.E.; Jardetzky, T.S.; Longnecker, R. Ephrin receptor A2 is a functional entry receptor for Epstein-Barr virus. Nat Microbiol 2018, 3, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C.; Dong, X.D.; Xie, C.; Liu, Y.T.; Lin, R.B.; Kong, X.W.; Hu, Z.L.; Ma, X.Y.; et al. R9AP is a common receptor for EBV infection in epithelial cells and B cells. Nature 2025, 644, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, D.N.K.; Ho, H.P.T.; Wu, L.S.; Chen, Y.Y.; Trinh, H.T.V.; Lin, T.Y.; Lim, Y.Y.; Tsai, K.C.; Tsai, M.H. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of Ganoderma microsporum immunomodulatory protein: Targeting glycoprotein gB to inhibit EBV and HSV-1 infections via viral fusion blockage. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 307, 142179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosking, M.P.; Shirinbak, S.; Omilusik, K.; Chandra, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Gentile, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Shrestha, B.; Grant, J.; Boyett, M.; et al. Preferential tumor targeting of HER2 by iPSC-derived CAR T cells engineered to overcome multiple barriers to solid tumor efficacy. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1087–1101.e1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).