1. Introduction

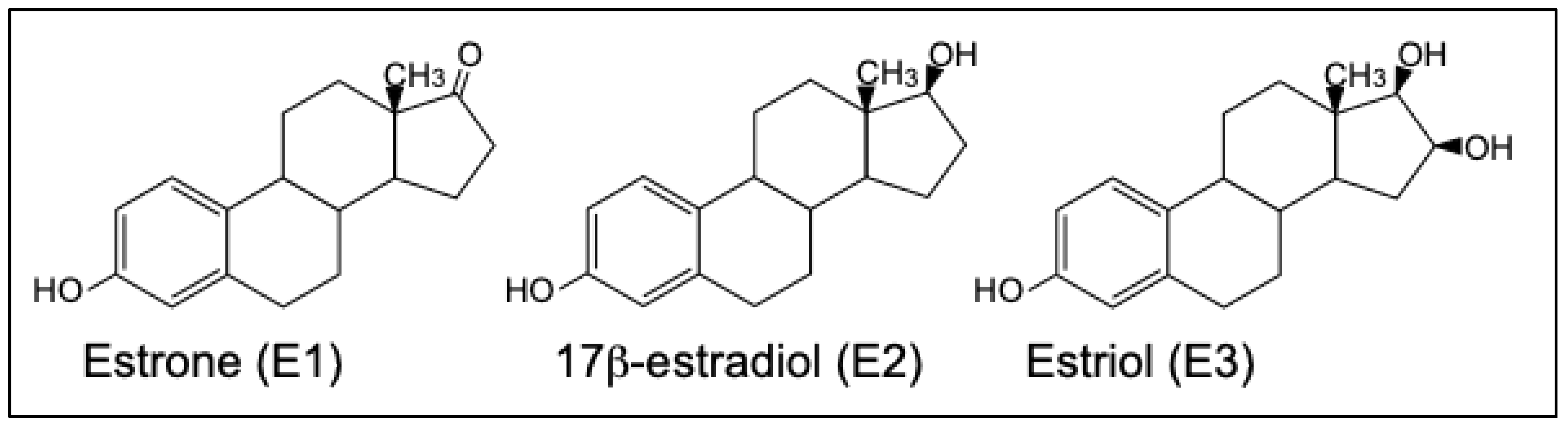

Estrogens are a class of steroid hormones that have diverse physiological activities in females and males in humans and other vertebrates [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Estrogens act by binding to estrogen receptors (ERs) [

5,

6], which are transcription factors that belong to the nuclear receptor family, which also includes receptors for progestins, androgens, and corticosteroids [

7,

8,

9]. To date, two distinct estrogen receptors: estrogen receptor alpha (ERa) and estrogen receptor beta (ERb), respectively, have been isolated in mammals and other vertebrates [

10,

11,

12]. The response of ERa and ERb in humans and other vertebrates to 17b-estradiol (E2), the main physiological estrogen, as well as to estrone (E1) and estriol (E3) (

Figure 1) has been studied extensively [

5,

6,

10,

13].

Although ERs with sequence similarity to ERa [

14,

15] and ERb [

14,

15,

16] have been isolated from elasmobranchs (sharks, rays, and skates), only the response to steroids by ERb from the cloudy catshark (

Scyliorhinus torazame) and whale shark (

Rhincodon typus) has been studied [

16]. Estrogen activation of a gnathostome ERa has not been reported. Elasmobranchs, along with Holocephali, comprise the two extant subclasses of Chondrichthyes, jawed fishes with skeletons composed of cartilage rather than calcified bone [

17]. Chondrichthyes occupy a key position relative to fish and terrestrial vertebrates,

having diverged from bony vertebrates about 450 million years ago [

14,

18]

. As the oldest group of extant jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes), the properties of ERa and ERb

in cartilaginous fishes can provide important insights into the early evolution of ERa and ERb from an ancestral ER in lamprey [

19]. Moreover, elephant shark has the slowest evolving genome of all known vertebrates, including the slowly evolving coelacanth [

14], which makes elephant shark genes windows into the past, and, thus, a good system to study the evolution of the ER, including selectivity of the ER in a basal vertebrate for steroids and the subsequent divergence in steroid selectivity in human ER, in other terrestrial vertebrate ERs and in ray-finned fish ERs [

20]. Another point of interest for the ER in elephant shark is that elephant sharks contain three full-length ERas [

14], raising the question of each how these three ERas compare with each other and with mammalian ERas in their response to estrogens.

To remedy this gap in our understanding of ERa activation in a basal jawless vertebrate, we have studied the response to estradiol, estrone, and estriol of three full-length

Callorhinchus milii ERas, as well as

C. milii ERb. Here we report that despite the strong sequence similarity among

C. milii ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERb, there are some differences in their half-maximal response (EC50) and fold-activation to these three physiological estrogens. We find that E2 had the lowest EC50 for all four ERs. E2 and E3 had a similar fold activation for ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERb. Overall, estrogen activation of

C. milii ERa and ERb was similar to that for human ERa and ERb [

5,

7], indicating substantial conservation of the vertebrate ER in the 525 million years since the divergence of cartilaginous fish and humans from a common ancestor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

C. milii elephant sharks of both sexes were collected in Western Port Bay, Victoria, Australia, using recreational fishing equipment, and transported to Primary Industries Research Victoria, Queenscliff, using a fish transporter. The animals were kept in a 10-t round tank with running seawater (SW) under a natural photoperiod for at least several days before sampling. Animals were anesthetized in 0.1% (w/v) 3-amino benzoic acid ethyl ester (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After the decapitation of the animal, tissues were dissected out, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C. All animal experiments were conducted according to the Guideline for Care and Use of Animals approved by the committees of University of Tokyo [

21].

2.2. Chemical Reagents

Estrone (E1), 17b-estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO). All chemicals were dissolved in dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO). The concentration of DMSO in the culture medium did not exceed 0.1%.

2.3. Cloning of Estrogen Receptors

When we began this project, the genome of

C. milii had not yet been sequenced [

14]. Thus, we needed to sequence an ER in

C. milii as a first step in determining the number of ERs and their sequences in

C. milii. For this goal, we used two conserved amino acid regions in the DNA-binding domain (GYHYGVW) and the ligand-binding domain (NKGM/IEH) of vertebrate ERs to design the degenerate oligonucleotides to clone

C. milii ERs. The second PCR used the first PCR amplicon, and nested primers that were selected in the DNA binding domain (CEGCKAF) and the ligand binding domain (NKGM/IEH). As a template for PCR, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using total RNA isolated from the ovary. The amplified DNA fragments were subcloned with TA-cloning plasmids pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 5’ and 3’ ends of the ER cDNAs were amplified by rapid amplification of the cDNA end (RACE) using a SMART RACE cDNA Amplification kit (BD Biosciences Clontech., Palo Alto, CA). To amplify the isoforms of elephant shark ER, we applied a PCR-based cDNA amplification technique using the primers et (5’-TGAAGTGTGATCGTCCAGGCGACAG-3’ and 5’-CAAGCTGGAGGATAAGACATCGAC -3’). Sequencing was performed using a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit and analyzed on the Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer.

We used the

C. milii extracted RNA to clone ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, ERa4, and ERb, which had sequences corresponding to the sequences of the

C. milii genome deposited by Venkatesh et al., 2014 [

14].

2.4. Database and Sequence Analysis

All sequences generated were searched for similarity using BLASTn and BLASTp at the web servers of the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI). We found four ERa genes and one ERb gene [

14], which were aligned using ClustalW [

22].

2.5. Reporter Gene Assay

Full-length estrogen receptors were amplified using specific forward and reverse primers designed at start and stop codons and cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). In addition, ERs with a FLAG-tag added to the N-terminus were also prepared by PCR. A reporter construct, pGL4.23-4xERE was produced by subcloning of oligonucleotides having 4xERE into the KpnI-HindIII site of pGL4.23 vector (Promega). All cloned DNA sequences were verified by sequencing.

Reporter gene assays using full-length ERs were performed in Human Embryonic Kidney 293 cells (HEK293 cells). HEK293 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5 x 104 cells/well in phenol-red-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% charcoal/dextran-treated fetal bovine serum. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 400 ng of reporter construct, 25 ng of pRL-TK (as an internal control to normalize the variation in transfection efficiency; contains the Renilla reniformis luciferase gene with the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter), and 200 ng of pcDNA3.1-estrogen receptor using polyethylenimine (PEI). After 5 h of incubation, ligands were applied to the medium at various concentrations. After an additional 43 h, the cells were collected, and the luciferase activity of the cells was measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System. Promoter activity was calculated as firefly (P. pyralis)-luciferase activity/sea pansy (R. reniformis)-luciferase activity. The values shown are mean ± SEM from three separate experiments, and dose-response data, which were used to calculate the half maximal response (EC50) for each steroid, were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

3. Results

3.1. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of cDNAs for four Elephant Shark ERa Genes and one ERb Gene

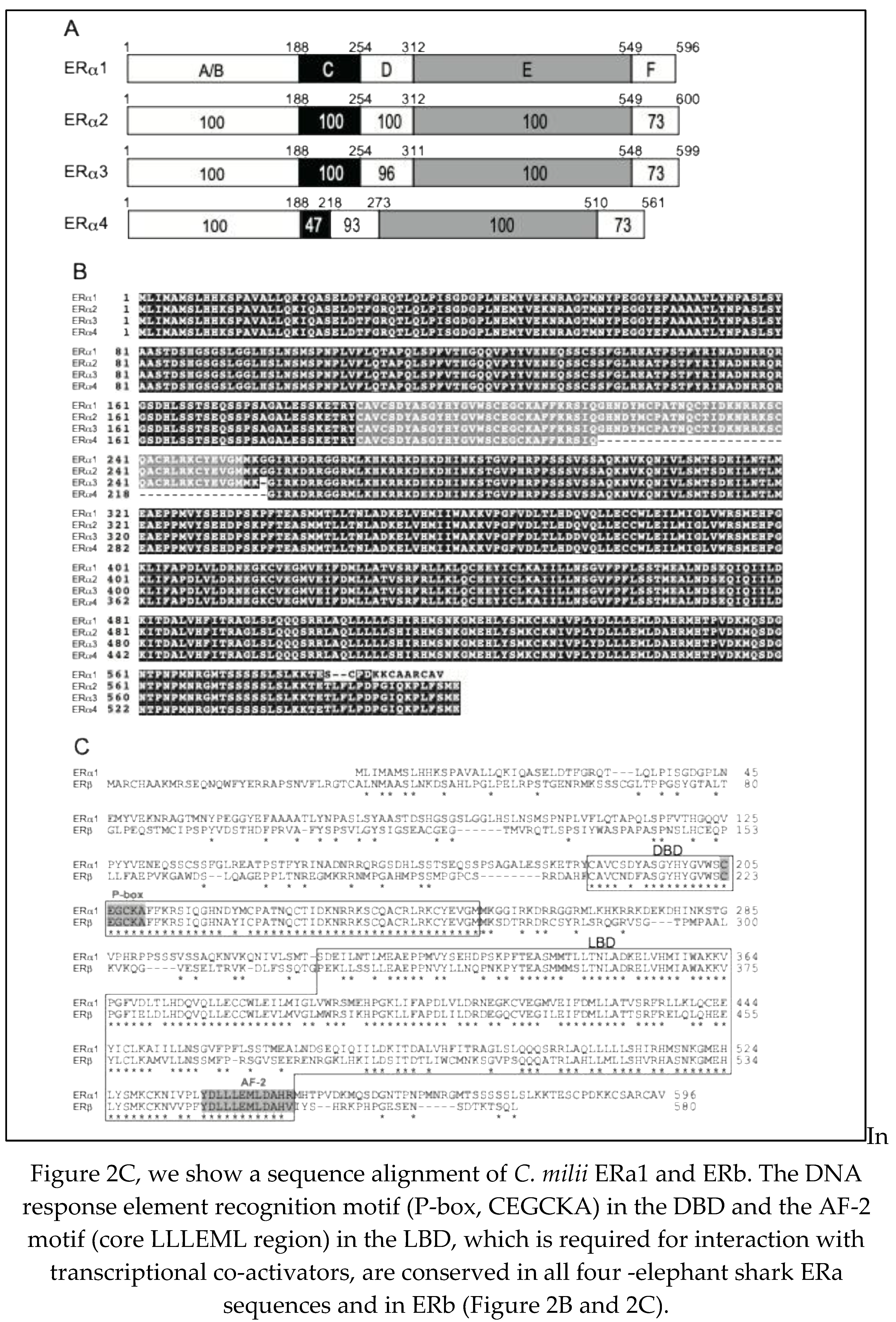

Using standard RT-PCR and RACE techniques, we successfully cloned four full-length ERs, designated as ERa1, ERa2, ERa3 (

Figure 2A, B), and ERb (

Figure 2C), from elephant shark ovary RNA. The cDNA for elephant shark ERa1 predicted a 596 amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 66.6 kDa (GenBank accession no. LC068847), and the cDNA for elephant shark ERb predicted a 580 amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 64.9 kDa (GenBank accession no. LC068848),

Figure 2A, B. In addition, we cloned the other two full-length elephant shark ERs: ERa2 and ERa3, which are found in GenBank (GenBank accession no. XM_007894403 for ERa2, XM_007894404 for ERa3

). ERa4 (GenBank accession no. XM_007894406) with a 39 amino acid deletion in the DNA-binding domain was also cloned (

Figure 2A, B).

The elephant shark ERa and ERb sequences contain the five recognizable steroid hormone receptor sub-domains in the expected order: the N-terminal region (A/B domain), DNA binding domain, DBD (C domain), hinge region (D domain), ligand binding domain, LBD (E domain), and C-terminal extension (F domain) (

Figure 2A). In

Figure 2A we compare the functional domains of ERa1, ERa2, ERa3 and ERa4.

Figure 2A shows that there is excellent conservation among these ERs of the A/B, C, D, E and F domains. This strong sequence conservation also is seen in the amino acid alignment of ERa1, ERa2, ERa3 and ERa4 shown in

Figure 2B.

Figure 2B shows the deletion in the DBD of ERa4, which probably explains the lack of binding of estrogens by

C. milii ERa4. The amino acid sequence of ERa4 is closest to ERa3. Overall,

Figure 2A and 2B show the strong sequence conservation in the four

C. milii ERa genes.

Elephant Shark ERa1, ERa2, and ERa3 show strong sequence conservation of their A/B, C, D, and E domains. ERa4 has a deletion in the DNA-binding domain [C domain], which explains its lack of transcriptional activation by estradiol. (B) Sequence alignment of Elephant Shark ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERa4. There is excellent conservation of the four-elephant shark ERa genes. (C) Aligned sequences of the elephant shark ERa1 and ERb. The DBD and LBD are indicated by open boxes. Residues are important for DNA response element recognition (the P-box), and the AF-2 region, which mediates contact of the LBD with transcriptional coactivators, is shaded gray. Numbers to the right indicate amino acid position. Asterisks indicate residues conserved in both ERa1 and ERb.

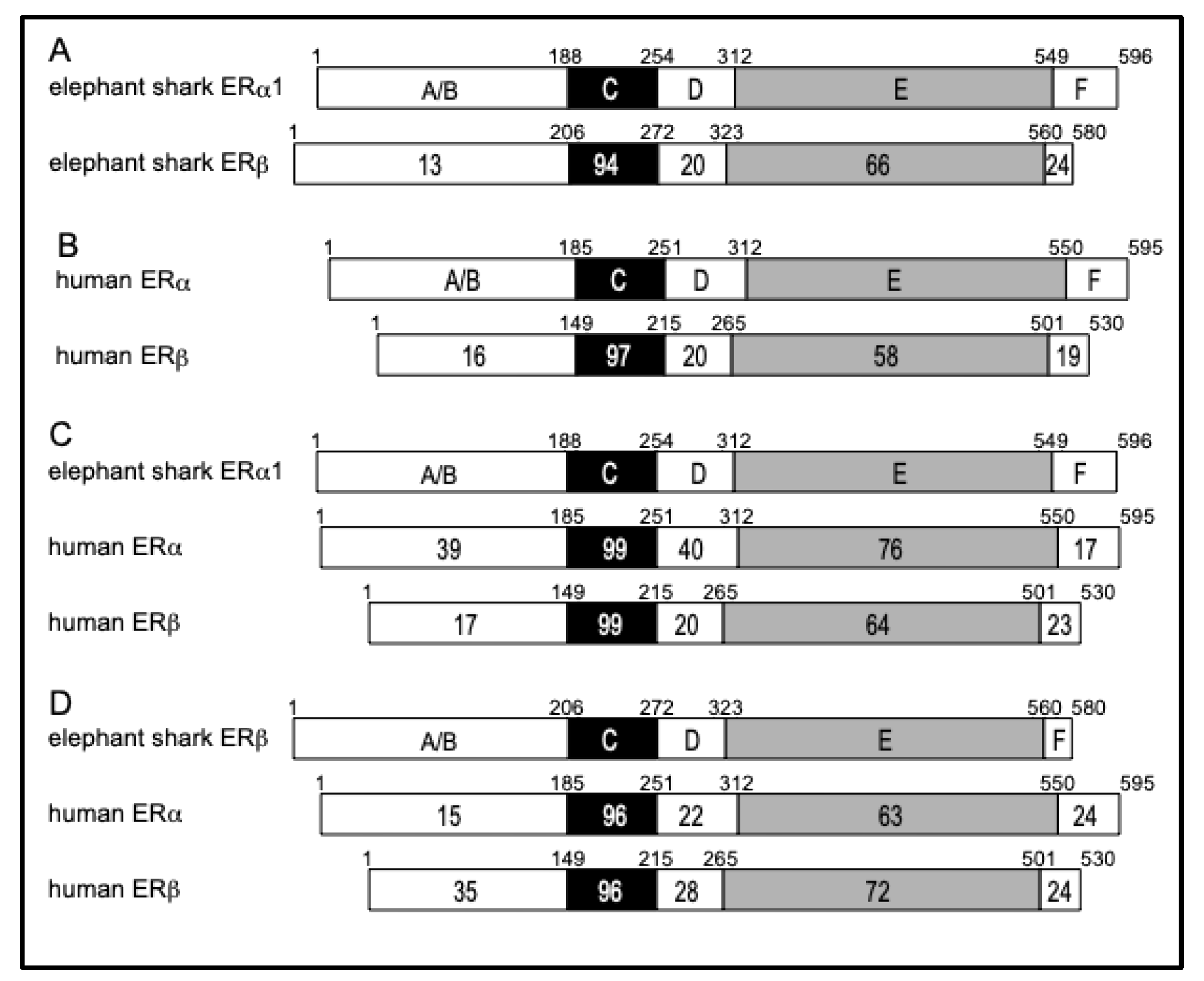

3.2. Comparison of Functional Domains on Human ERa and ERb with Functional Domains in Elephant Shark ERa and ERb

To gain additional insights into the evolution of the

C. milii ERs, we compared the functional domains of elephant shark ERa1to elephant shark ERb (

Figure 3A), of elephant shark ERa1 to human ERa and human ERb (

Figure 3C), and of elephant shark ERb to human ERa and human ERb (

Figure 3D). We also compared human ERa and ERb to each other (

Figure 3B).

The functional domains A/B through F are shown schematically with the number of amino acid residues indicated. The percentage of amino acid identity is shown. (A) Comparison of elephant shark ERa1 with elephant shark ERb. The N-terminal (A/B) domains of elephant shark ERa1 and ERb show strong divergence. There is also some divergence between the ligand (E) binding domain on elephant shark ERa1 and ERb. (B) Comparison of human ERa (accession no. NM000125) with human ERb (accession no. AB006590). The domains of human ERa with human ERb have similar sequence similarity to each other as elephant shark ERa1 and ERb. (C) Comparison of elephant shark ERa1 with human ERa and human ERb. Elephant shark ERa1 is closer to human ERa than to human ERb. (D) Comparison of elephant shark ERb with human ERa and human ERb. Elephant shark ERb is closer to human ERb than to human ERa.

Figure 3A shows the excellent conservation of the DNA-binding domains [C domains] (94% identity) and ligand-binding domains [E domains] (66% identity) in elephant shark ERa1 and ERb, in contrast to the weak conservation of the A/B domains (13% identity) at their N-terminus. Comparison of

Figure 3A and B reveals that the DBD in human ERa and

C. milii ERa1 and ERb have similar sequence conservation, while the LBD sequence in

C. milii ERa1 and

C. milii ERb are more conserved (66% identity) than the LBD in human ERa and ERb (58% identity).

Figure 3C shows the strong sequence conservation of the DBD in elephant shark ERa1 and human ERa and ERb.

Figure 3C also shows that there is stronger conservation (76%) of the LBD in elephant shark ERa1 and human ERa, compared to the similarity (64%) of the corresponding LBD in elephant shark ERa1 to human ERb.

Figure 3D shows the strong sequence conservation of the DBD in elephant shark ERa1 and human ERa and ERb.

Figure 3D also shows the stronger conservation (72%) of the LBD in elephant shark ERb and human ERb, compared to the similarity (64%) to the corresponding LBD in human ERa.

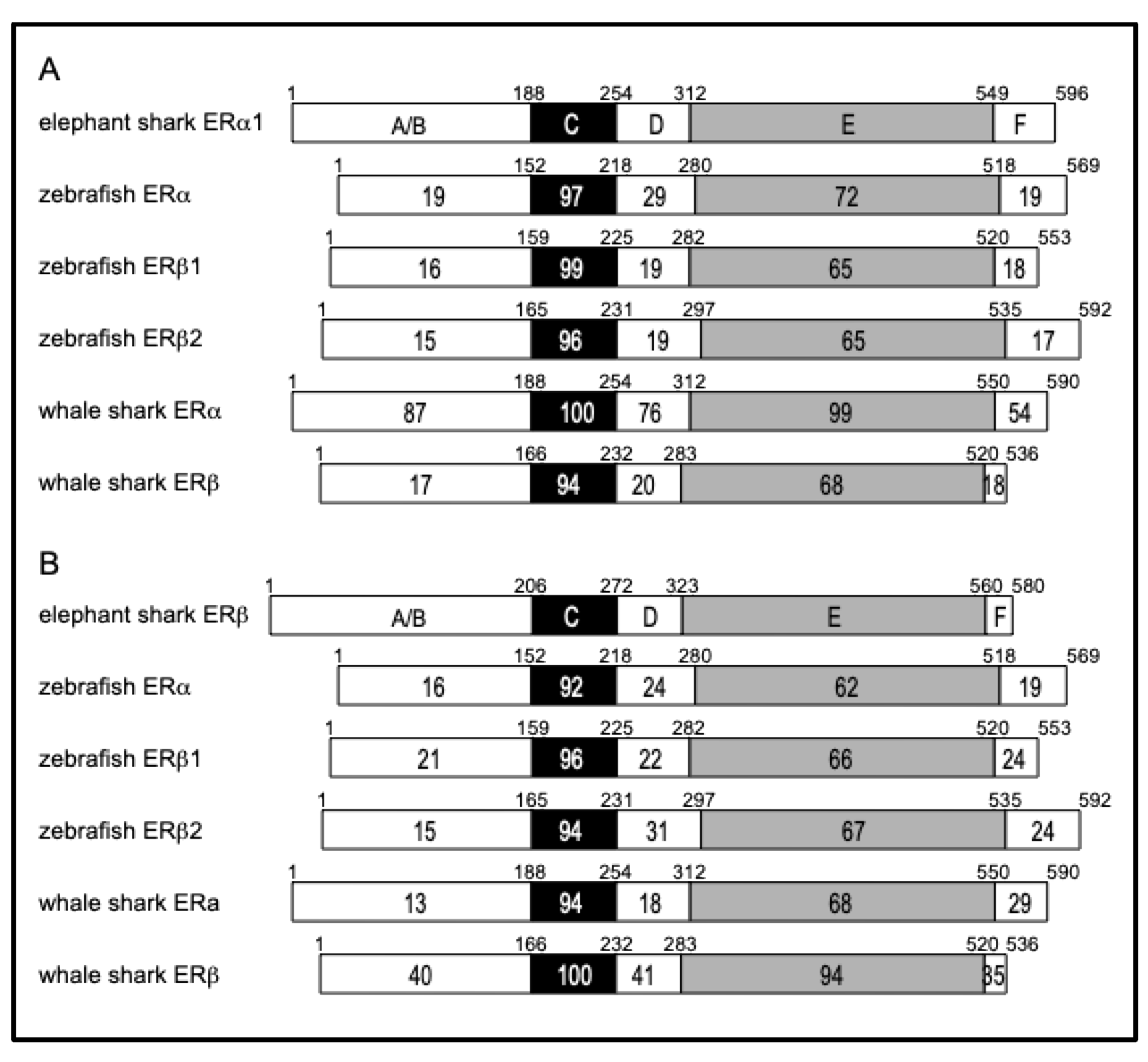

3.3. Comparison of Functional Domains on Elephant Shark ERa and ERb with Functional Domains in Zebrafish, and Whale Shark

To gain an additional insight into the evolution of elephant shark ERa and ERb, we compared their sequences to ERa and ERb sequences in zebrafish and whale shark (

Figure 4).

The functional domains A/B through F are shown schematically with the number of amino acid residues indicated. The percentage of amino acid identity is shown. (A) Comparison of elephant shark ERa1 with zebrafish and whale shark ERs. (B) Comparison of elephant shark ERb with zebrafish and whale shark ERs. Genbank accession no. NM_152959 (zebrafish ERa), AF516874 (zebrafish ERb1), AF349413 (zebrafish ERb2), XM_048600891 (whale shark ERa), and AB551716 (whale shark ERb).

The sequence comparisons between elephant shark ERa and ERb domains with ERa and ERb domains in whale shark revealed an unexpected sequence similarity (87% identity) between the A/B domain on elephant shark ERa and whale shark ERa. The A/B domain in whale shark ERb and elephant shark ERb has 40% identity. Interestingly, the A/B domains on elephant shark ERa and ERb domains have 39% and 35% sequence identity, respectively, with the A/B domains on human ERa and human ERb, respectively.

Figure 3C shows the stronger conservation of the LBD in elephant shark ERb and human ERb (72% identity), compared to the similarity to the corresponding LBD in human ERa (63% identity). The LBD of elephant shark ERa1 is closer to the LBD in human ERa than the LBD in human ERb, and the LBD of elephant shark ERb is closer to the LBD in human ERb than the LBD in human ERa.

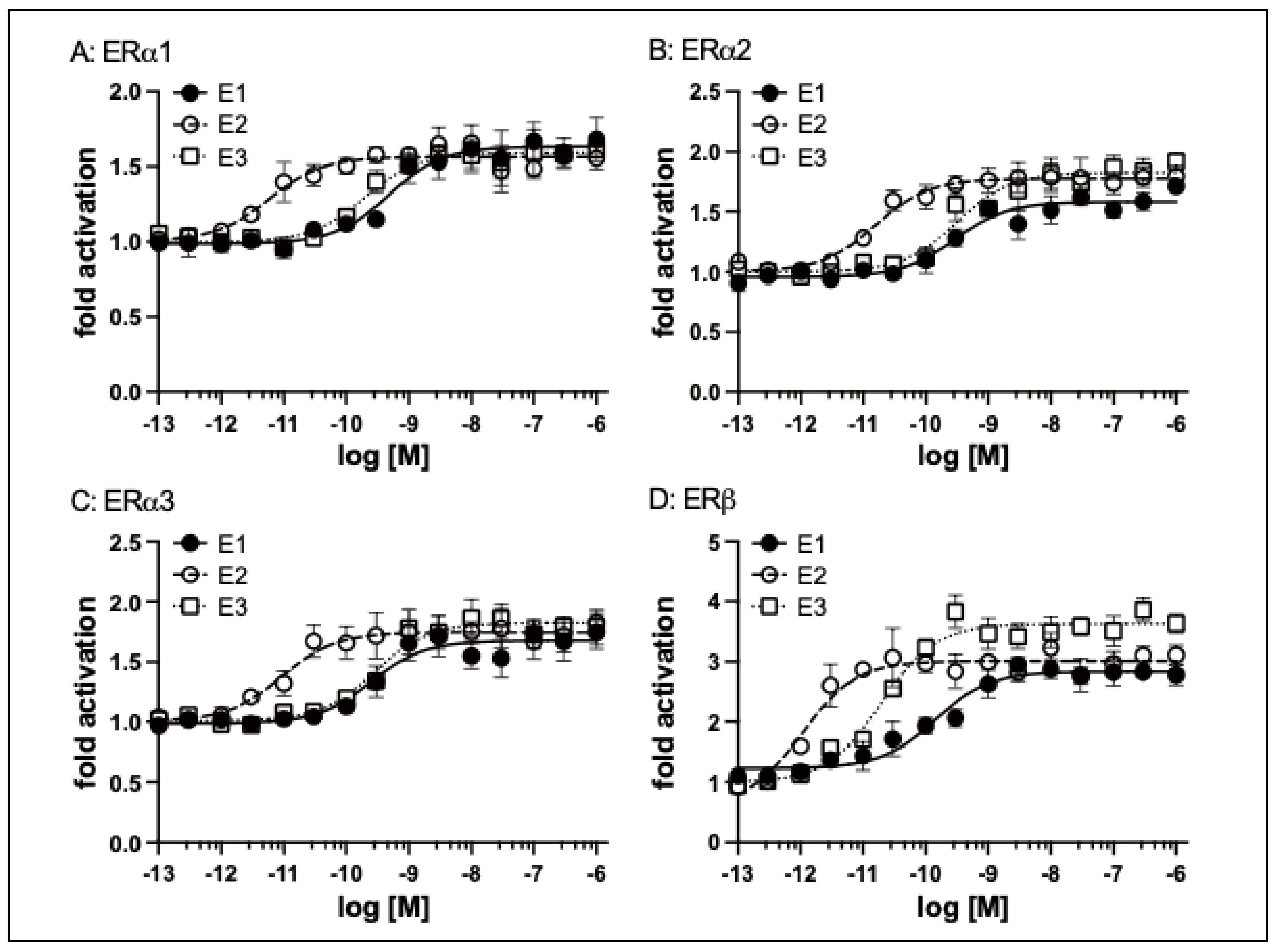

Elephant shark ERs were transfected into HEK293 cells with an ERE-driven reporter gene. Concentration-response profile for ERa1 (A), ERa2 (B), ERa3 (C), and ERb (D) for E1, E2, and E3 (10-13M to 10-6M). Data are expressed as a ratio of a vehicle (DMSO) to other test chemicals. Each point represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and vertical bars represent the mean ± SEM.

3.4. Transcriptional Activities of Elephant Shark ERa and ERb.

A transactivation assay was used to examine the response to the physiological estrogens E1, E2, and E3 of the three active isoforms of elephant shark ERa. The three isoforms, ERa showed ligand-dependent transactivation (

Figure 5A, B, C). The EC50s for transcriptional activation of ERa1, ERa2, and ERa3 were 0.49 nM, 0.29 nM, and 0.25 nM (E1), 0.0059 nM, 0.016 nM, and 0.0093 nM (E2), and 0.2 nM, 0.31 nM, and 0.29 nM (E3), respectively (

Table 1).

We also examined the induction of elephant shark ERb transcriptional activity by different concentrations of estrogens (E1, E2, and E3). All three estrogens activated transcription of elephant shark ERb in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 5D). The half-maximal response (EC50) for transcriptional activation of elephant shark ERb was 0.14 nM for E1, 0.001 nM for E2, and 0.02 nM for E3 (

Table 1). Although there was no significant difference in EC50 values for activation by an estrogen of ERa1 and ERb, the fold activation values for E2 were higher than those for E1 and E2 (

Table 1). Thus, the elephant shark estrogen receptors exhibited a ligand responsiveness observed human estrogen receptors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

4. Discussion

Significant advances have been made in elucidating the evolution of estrogen signaling in animals [

1,

2,

9,

11,

19,

23,

24]. Amphioxus, a chordate that is a close ancestor of vertebrates, contains an ER and a steroid receptor (SR) that is an ortholog of receptors for 3-keto-steroids, including testosterone, progesterone, cortisol, and aldosterone [

11,

25]. Contrary to expectations, the amphioxus ER does not bind E2 or other steroids [

11,

24,

25], while E2 and E1 are transcriptional activators of the SR [

11,

25]. Atlantic sea lamprey, a jawless fish, contains an ER [

19] that is activated by E2 and E1 [

11,

24].

The estrogen receptors in Chondrichthyes, cartilaginous fishes with jaws, are basal to lobe-finned fishes and are ancestors of terrestrial vertebrates [

14]. These ERs are still not fully characterized [

15,

26]. The identification of ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, ERa4, and ERb from the sequencing of the elephant shark [

14] provided an opportunity to investigate estrogen signaling in a basal jawless vertebrate that evolved about 525 million years ago. We investigated the response to E1, E2, and E3 of ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERb from elephant shark expressed in HEK293 cells (

Figure 5). These studies revealed that elephant shark ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERb are activated by E1, E2, and E3. We note that we found that ERa4 did not respond to an estrogen, which we propose is due to a sequence deletion in the DBD (data not shown). Thus, we did not continue studies of estrogen activation of ERa4.

Our data with estrogen activation of ERa1, ERa2, ERa3, and ERb align with the established ligand binding characteristics of ERs in other vertebrates, thereby substantiating the conserved nature of estrogen signaling pathways [

25,

27,

28,

29]. Estrogen-dependent transcriptional activity of the ERs from various species, including other sharks, revealed that the ERs from all species have a stronger response to E2 than to E3 [

16,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Instead of only one ERa gene, elephant shark contains three ERa genes with very similar sequences, which is unexpected. The strong conservation of ERa4, which is not ligand-activated, also is unexpected. Further research is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the physiological function of estrogen and the multiple estrogen receptors in elephant sharks. This data should provide clues for understanding the physiological function(s) of each isoform.

In summary, this is the first report with evidence for the conservation of elephant shark ERa and ERb compared to human ERa and ERb, which provides a valuable perspective on the early evolutionary history of these critical nuclear receptors in vertebrates. The findings from this study not only confirm the conserved nature of ER-mediated estrogen signaling across vertebrates but also open new avenues for research into the functional diversification of these receptors across vertebrates. These findings furnish researchers with critical molecular data to examine the role of ERs in future studies, such as those examining gonadal development, reproductive biology, and developmental and evolutionary endocrinology.

Author Contribution

Y.A.: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, and Data curation. H.N.: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. W. T.: Resources. S.H.: Resources. M.E.B.: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Y.K.: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (23K05839) to Y.K., and the Takeda Science Foundation to Y.K.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

All data is freely available on request to Dr. Katsu or to Dr. Baker.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Dr. Kaori Oka for her suggestions and helpful advice. We also thank colleagues in our laboratories.

References

- Bondesson, M.; Hao, R.; Lin, C.-Y.; Williams, C.; Gustafsson, J. Estrogen receptor signaling during vertebrate development. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2015, 1849, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Dahlman-Wright, K. The gene regulatory networks controlled by estrogens. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 334, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRoo, B.J.; Korach, K.S. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.J.; Hewitt, S.C.; Arao, Y.; Korach, K.S. Estrogen Hormone Biology. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2017, 125, 109–146. [Google Scholar]

- Paterni, I.; Granchi, C.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Minutolo, F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids 2014, 90, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldring, N.; Pawson, T.; McDonnell, D.; Treuter, E.; Gustafsson, J.; Pike, A.C. Structural Insights into Corepressor Recognition by Antagonist-bound Estrogen Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 10449–10455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlman-Wright, K.; Cavailles, V.; Fuqua, S.A.; Jordan, V.C.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Korach, K.S.; Maggi, A.; Muramatsu, M.; Parker, M.G.; Gustafsson, J. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, G.V.; Tavares, R.; Dauphin-Villemant, C.; Demeneix, B.A.; Baker, M.E.; Laudet, V. Independent elaboration of steroid hormone signaling pathways in metazoans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 11913–11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.E. Origin and diversification of steroids: Co-evolution of enzymes and nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 334, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, G.G.; Enmark, E.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J.A. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5925–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgham, J.T.; Brown, J.E.; Rodríguez-Marí, A.; Catchen, J.M.; Thornton, J.W. Evolution of a New Function by Degenerative Mutation in Cephalochordate Steroid Receptors. PLOS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.E.; Nelson, D.R.; Studer, R.A. Origin of the response to adrenal and sex steroids: Roles of promiscuity and co-evolution of enzymes and steroid receptors. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 151, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escande, A.; Servant, N.; Rabenoelina, F.; Auzou, G.; Kloosterboer, H.; Cavaillès, V.; Balaguer, P.; Maudelonde, T. Regulation of activities of steroid hormone receptors by tibolone and its primary metabolites. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 116, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, B.; Lee, A.P.; Ravi, V.; Maurya, A.K.; Lian, M.M.; Swann, J.B.; Ohta, Y.; Flajnik, M.F.; Sutoh, Y.; Kasahara, M.; et al. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 2014, 505, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filowitz, G.L.; Rajakumar, R.; O'Shaughnessy, K.L.; Cohn, M.J. Cartilaginous Fishes Provide Insights into the Origin, Diversification, and Sexually Dimorphic Expression of Vertebrate Estrogen Receptor Genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 2695–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsu, Y.; Kohno, S.; Narita, H.; Urushitani, H.; Yamane, K.; Hara, A.; Clauss, T.M.; Walsh, M.T.; Miyagawa, S.; Guillette, L.J.; et al. Cloning and functional characterization of Chondrichthyes, cloudy catshark, Scyliorhinus torazame and whale shark, Rhincodon typus estrogen receptors. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 168, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, J.G.; Miya, M.; Lam, K.; Tay, B.-H.; Danks, J.A.; Bell, J.; I Walker, T.I.; Venkatesh, B. Evolutionary Origin and Phylogeny of the Modern Holocephalans (Chondrichthyes: Chimaeriformes): A Mitogenomic Perspective. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 2576–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-P.; Rajasegaran, V.; Yew, K.; Loh, W.-L.; Tay, B.-H.; Amemiya, C.T.; Brenner, S.; Venkatesh, B. Elephant shark sequence reveals unique insights into the evolutionary history of vertebrate genes: A comparative analysis of the protocadherin cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 3819–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.W. Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 5671–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.E. Steroid receptors and vertebrate evolution. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 496, 110526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakumura, K.; Watanabe, S.; Bell, J.D.; Donald, J.A.; Toop, T.; Kaneko, T.; Hyodo, S. Multiple urea transporter proteins in the kidney of holocephalan elephant fish (Callorhinchus milii). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 154, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotnoir-White, D.; Laperrière, D.; Mader, S. Evolution of the repertoire of nuclear receptor binding sites in genomes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 334, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M.; Pettersson, K.; Schubert, M.; Bertrand, S.; Pongratz, I.; Escriva, H.; Laudet, V. An amphioxus orthologue of the estrogen receptor that does not bind estradiol: Insights into estrogen receptor evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 219–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsu, Y.; Kubokawa, K.; Urushitani, H.; Iguchi, T. Estrogen-Dependent Transactivation of Amphioxus Steroid Hormone Receptor via Both Estrogen and Androgen Response Elements. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awruch, C. Reproductive endocrinology in chondrichthyans: The present and the future. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 192, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Walter, P.; Kumar, V.; Krust, A.; Bornert, J.-M.; Argos, P.; Chambon, P. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature 1986, 320, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Gustafsson, J.A. Estrogen Signaling: A Subtle Balance Between ER alpha and ER beta. Mol. Interv. 2003, 3, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; A Katzenellenbogen, J. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation Estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta: regulation by selective estrogen receptor modulators and importance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000, 2, 335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsu, Y.; Lange, A.; Urushitani, H.; Ichikawa, R.; Paull, G.C.; Cahill, L.L.; Jobling, S.; Tyler, C.R.; Iguchi, T. Functional Associations between Two Estrogen Receptors, Environmental Estrogens, and Sexual Disruption in the Roach (Rutilus rutilus). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3368–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsu, Y.; Kohno, S.; Hyodo, S.; Ijiri, S.; Adachi, S.; Hara, A.; Guillette, L.J.; Iguchi, T. Molecular Cloning, Characterization, and Evolutionary Analysis of Estrogen Receptors from Phylogenetically Ancient Fish. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 6300–6310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsu, Y.; Taniguchi, E.; Urushitani, H.; Miyagawa, S.; Takase, M.; Kubokawa, K.; Tooi, O.; Oka, T.; Santo, N.; Myburgh, J.; et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of ligand- and species-specificity of amphibian estrogen receptors. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 168, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Katsu, Y.; Miyagawa, S.; Ogino, Y.; Urushitani, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Hirai, T.; Shears, J.A.; Nagae, M.; Yamamoto, J.; et al. Comparative responsiveness to natural and synthetic estrogens of fish species commonly used in the laboratory and field monitoring. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 109, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatsu, R.; Katsu, Y.; Kohno, S.; Mizutani, T.; Ogino, Y.; Ohta, Y.; Myburgh, J.; van Wyk, J.H.; Guillette, L.J.; Miyagawa, S.; et al. Characterization of evolutionary trend in squamate estrogen receptor sensitivity. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2016, 238, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhl, H. Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration. Climacteric 2005, 8, 3–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanczyk, F.Z. Metabolism of endogenous and exogenous estrogens in women. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 242, 106539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).