1. Introduction

Modern distributed systems, for example, Internet of Things and autonomous vehicle networks, have requirements for decentralisation, security, trust and consensus that often conflict with each other. Traditional approaches to security often rely on centralised authorities for key management and identity verification, which are ill-suited to environments consisting of power-limited and intermittently connected devices. The use of centralised authorities introduces single points of failure, bottlenecks and high-value targets for attack - undermining the resilience that distributed systems can offer [

1,

2,

3].

Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) are aircraft that operate without a pilot or crew on board. They are frequently referred to as Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS), Unmanned Aircraft Vehicles (UAV) or Drones, with the preferred nomenclature being dependent on the organisation operating or developing the system. These devices were initially piloted aircraft retrofitted for remote control and used for high-risk or one-way operations [

4]. As technology improved, their use for reconnaissance and electronic warfare became more widespread, with armed platforms becoming prevalent during the Global War on Terror and the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. These operations highlighted the security challenges involved in deploying relatively simple systems to an operational environment [

5].

With improvements in battery, electric motor and radio-frequency (RF) connectivity technologies, UAS have become accessible to consumers and non-military users. UAS now range from small devices that can be held in the palm of your hand, with a range measured in metres, to traditional aircraft-sized platforms with a range measured in 1000 km. Regardless of the scale, the key components of a UAS are an aircraft vehicle and a ground control station. These are linked with an RF connection that provides control and data link capabilities [

6]. Extensive research shows the vulnerability of these connections either to direct attack or as an attack vector to access the aircraft vehicle or control station [

6,

7]. The use of fibre-optic data links to remove this attack vector is a recent and well-documented operational example from the Russia-Ukraine war, which further highlights the importance of cybersecurity to UAS operations and the vulnerability created through the use of COTS products in a military capability [

8].

1.1. Regulatory Framework

In the UK, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and Military Aviation Authority (MAA) are responsible for the regulatory oversight of civilian and military Unmanned Aircraft Systems, respectively [

9,

10]. Both agencies adopt the European Union Aviation Safety Agency’s (EASA) three-tiered structure for categorising UAS (Open, Specific, Certified). These frameworks ensure that regulatory requirements are proportional to the level of risk associated with the type of UAS being considered. A key principle in the framework’s approach is to remain technology agnostic, specifying what level of security/performance is required, without defining how to achieve it. This gives UAS developers the freedom to innovate and create new ways of securely deploying these technologies[

11].

The maturation of AI and Machine Learning technologies means that autonomous UAS are now feasible. The emphasis of CAA and MAA regulations differs. The CAA focus is on ensuring deterministic behaviour by autonomous platforms in order to maintain an equivalent level of safety to crewed platforms[

9]. In addition to flight safety, the MAA and wider Ministry of Defence emphasis is on compliance with international laws relating to armed conflict and ensuring a human remains ’in the loop’ and responsible for the use of lethal weapons [

10,

12].

Recognising the potential risks resulting from autonomous UAS operations, the CAA encourages a

Secure by Design methodology. This requires cybersecurity to be considered from the start of the design process and addresses both the network security of the system and the specific risk of AI and machine learning systems being manipulated in ways that could compromise their operational safety[

11]. As such, there is a clear requirement for nodes within an autonomous UAS network to be able to communicate securely and for an architecture which can robustly handle compromised nodes attempting to maliciously undermine UAS operations.

One potential solution to these issues combines applied cryptography and distributed computing, focusing on methods to achieve Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) and decentralised security. The Byzantine Generals’ Problem [

13] highlights the fundamental difficulty of achieving unanimous agreement among distributed entities when some participants may behave maliciously. Overcoming this requires cryptographic primitives that can ensure authenticity, integrity, and verifiability without relying on a central authority.

Fundamental to these solutions is the concept of secret sharing, which was independently defined in the works of Shamir [

14] and Blakley [

15]. Shamir’s scheme, based on polynomial interpolation, offers a relatively simple method to divide a secret into multiple shares such that only a predefined threshold of shares can reconstruct the original secret, while fewer shares reveal no information. However, these initial secret sharing schemes required a "trusted dealer" to generate and distribute the shares, creating a single point of trust. This limitation led to the development of Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS), pioneered by Feldman [

16] and Pedersen [

17]. Feldman’s VSS introduced mechanisms for participants to verify the validity of their shares against public commitments, ensuring the honest behaviour of the dealer. Pedersen advanced VSS further and proposed DKG, where multiple parties collaboratively generate a shared secret key without any single party ever knowing the complete key [

18]. This eliminates the trusted dealer entirely, achieving true decentralisation in key creation, but at the expense of increased communication overheads.

These advancements enable the construction of cryptographic schemes, such as threshold signatures, where a group can collectively perform a cryptographic operation (e.g., sign a message) only when a threshold of members contributes their secret shares. This collective signing capability provides a useful tool for decentralised authentication and verifiable group decision-making, offering a viable alternative to centralised models in the context of highly distributed and autonomous device networks, with clear relevance to contemporary problems faced by UK Defence as they increase the proportion of combat mass provided by unmanned vehicles [

19].

This paper seeks to assess the performance of cryptographic libraries that could enable a decentralised key management and consensus mechanism for autonomous devices and reduce reliance on centralised control architectures. The main contributions of the paper are:

Provide a comprehensive comparison of current solutions for distributed key management and consensus.

Benchmark the performance of open source solutions, to demonstrate the selected technologies and analyse their performance. Identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for further improvement.

Assessing the viability of adopting existing solutions versus building a custom solution based on theoretical principles.

2. Related Work

This section will define the core cryptographic protocols that enable the project’s key functions: secure, scalable group communication and decentralised consensus. All of these protocols are built on the fundamental concept of a cryptographic key. Much like a physical key secures a lock, a cryptographic key is a string of digital data (1’s and 0’s) that secures a message by applying an algorithm to it to make it readable only to those with the corresponding key. These keys can be public or private, and symmetric or asymmetric, but they all serve the same core function.

We will begin by exploring secret sharing, a technique for securely distributing a secret across multiple participants. Next, we will see how these secrets can be used to create digital signatures that verify a message’s authenticity and integrity. Finally, we will define the methods used for secure group communication over otherwise insecure channels.

2.1. Secret Sharing

The three schemes outlined enable the division of a secret, for instance, a password, between multiple parties and then at a later time, a minimum threshold of those parties can reconvene and recreate the secret. Once implemented into usable libraries, these schemes require varying communication channels between the parties; the impact of those channels is not discussed here. Instead, the focus is on the mathematical principles that enable the schemes.

2.1.1. Shamir’s Secret Sharing

Shamir’s Secret Sharing is a threshold scheme where a secret is split into n shares such that any t shares can reconstruct the secret, but fewer than t reveal nothing. It has two phases: sharing and reconstruction. It relies on a trusted dealer to take the original secret and honestly follow the protocols to divide the secret into shares and likewise to reconstruct the secret.

2.1.2. Sharing Phase

Let

be the secret. The secret is shared as follows [

14]:

- 1.

Choose a random polynomial

of degree

over

:

- 2.

Generate and privately distribute n shares to each participant .

Reconstruction Phase

Given any

t shares from a set of participants

J, the secret

can be reconstructed using Lagrange Interpolation:

Shamir’s scheme is

information-theoretically secure, meaning that with fewer than

t shares, the secret remains completely unknown, regardless of an adversary’s computing power or time [

14,

20]. It is dependent on the honesty of the dealer and assumes that an adversary can eavesdrop on the various messages required to communicate the sharing, but not to modify them or the dealer’s actions.

2.2. Verifiable Secret Sharing

Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS) schemes enhance secret sharing by allowing participants to verify that a dealer has behaved honestly. This protects against a malicious dealer who might distribute invalid shares and ensures that a valid secret can be reconstructed when required.

2.2.1. Feldman’s Verifiable Secret Sharing

Feldman’s VSS is an extension of Shamir’s scheme, which allows participants to verify that their shares originate from a single polynomial. The scheme’s verifiability is based on homomorphic commitments and the computational difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem [

16,

20].

Let G be a cyclic group of large prime order q with a publicly known generator g. The secret s and the polynomial coefficients are elements of .

Sharing Phase

The dealer performs the following steps to share the secret :

- 1.

Choose a random polynomial

of degree

:

- 2.

Compute and broadcast public commitments to the coefficients:

- 3.

Generate and privately distribute shares to each participant .

Verification Phase

Each participant

j verifies their private share

against the public commitments by checking:

If the equality holds, the share is valid. This works because the right side expands to a commitment to

:

Reconstruction Phase

Given any

t valid shares from a set of participants

J, the secret

s is recovered using Lagrange Interpolation:

Unlike Shamir’s scheme, Feldman’s VSS is not information-theoretically secure but is computationally secure. Its security relies on the assumption that the discrete logarithm problem is hard in the group G. The validity of that assumption in the face of Quantum Computing will be considered during the design section of this paper.

2.2.2. Pedersen’s Verifiable Secret Sharing

Pedersen’s VSS enhances Feldman’s scheme to provide perfect hiding of the secret. While Feldman’s scheme is computationally hiding, Pedersen’s scheme is information-theoretically hiding. This is achieved by using a second random polynomial to blind the secret-carrying polynomial [

18] [

20].

The scheme operates in a group G of large prime order q. It requires two different generators, g and h, where the discrete logarithm of h with respect to g is unknown to all parties, including the dealer.

Sharing Phase

The dealer executes the following steps to share the secret :

- 1.

Choose two random polynomials,

and

, both of degree

:

- 2.

Compute and broadcast public commitments using both polynomials:

- 3.

Generate and privately distribute a pair of shares to each participant .

Verification Phase

Each participant

j verifies their pair of shares

against the public commitments with the check:

The verification works because the right-hand side is a commitment to the evaluation of both polynomials:

Reconstruction Phase

Any group of

t or more participants can reconstruct the secret. They pool their verified shares. The reconstruction only requires the primary shares,

. The blinding shares,

, are discarded after verification. Given

t valid shares from a set of participants

J, the secret

s is recovered using Lagrange Interpolation on the

values:

Pedersen’s VSS is information-theoretically hiding because the commitment perfectly hides s thanks to the random . The scheme remains computationally binding, as the dealer cannot find an alternative set of values to open the commitment without solving the discrete logarithm problem.

2.3. Distributed Key Generation

While Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS) protects against a dishonest dealer, DKG removes the need for a dealer entirely. In a DKG protocol, a group of participants jointly generate a public key and a corresponding set of private key shares, without any single party ever knowing the full private key.

2.3.1. Pedersen’s Distributed Key Generation

This protocol is a method for jointly creating a key pair by having all participants run Feldman’s VSS in parallel. Each participant acts as a dealer for their own randomly chosen secret, and the final group secret is the sum of all secrets that were shared correctly [

17,

21].

The protocol operates in a group of prime order q with a public generator g.

Sharing Phase

- 1.

-

Each participant

chooses a random polynomial

of degree

t over

:

The value is participant ’s individual secret contribution, which we can denote as .

- 2.

-

broadcasts public commitments to the coefficients of their polynomial:

The commitment to the secret contribution is .

- 3.

computes and privately sends the share to each other participant .

Verification and Complaint Phase

- 1.

Each participant

verifies the shares they received from every other participant

by checking if the share is consistent with the public commitments:

- 2.

If the check fails for a share from , participant broadcasts a complaint against .

- 3.

If a participant receives more than t complaints, they are disqualified. Otherwise, for each complaint from a participant , must broadcast the correct share . If any revealed share is still invalid, is disqualified.

Key Computation Phase

- 1.

The set of all non-disqualified participants is established, often called the qualifying set.

- 2.

The final group public key,

y, is computed by multiplying the initial commitments of all qualified participants:

- 3.

-

The final group secret key,

x, is the sum of the individual secret contributions. This key is never computed in a single location.

Each participant holds a private share of this final key, which is the sum of all the valid shares they received: .

2.4. Digital Signatures

Digital signatures are another fundamental cryptographic function that allows the authenticity and integrity of a message to be verified. Proving that a message has not been altered and has been sent by the claimed originator. This section will provide an introduction to signatures and a more detailed explanation of Schnorr, BLS and FROST signatures.

Digital signature schemes have three phases:

- 1.

Key Generation. An algorithm that creates a public/private key pair (P,x). The private key is used for signing, and the public key is used for verification.

- 2.

Signing. A process that uses the private key to produce a unique signature for a given message.

- 3.

Verification. A process that takes a message, the signature and a public key as its input and will output "true" if the signature is valid for that message and public key ( or "false" if verification fails).

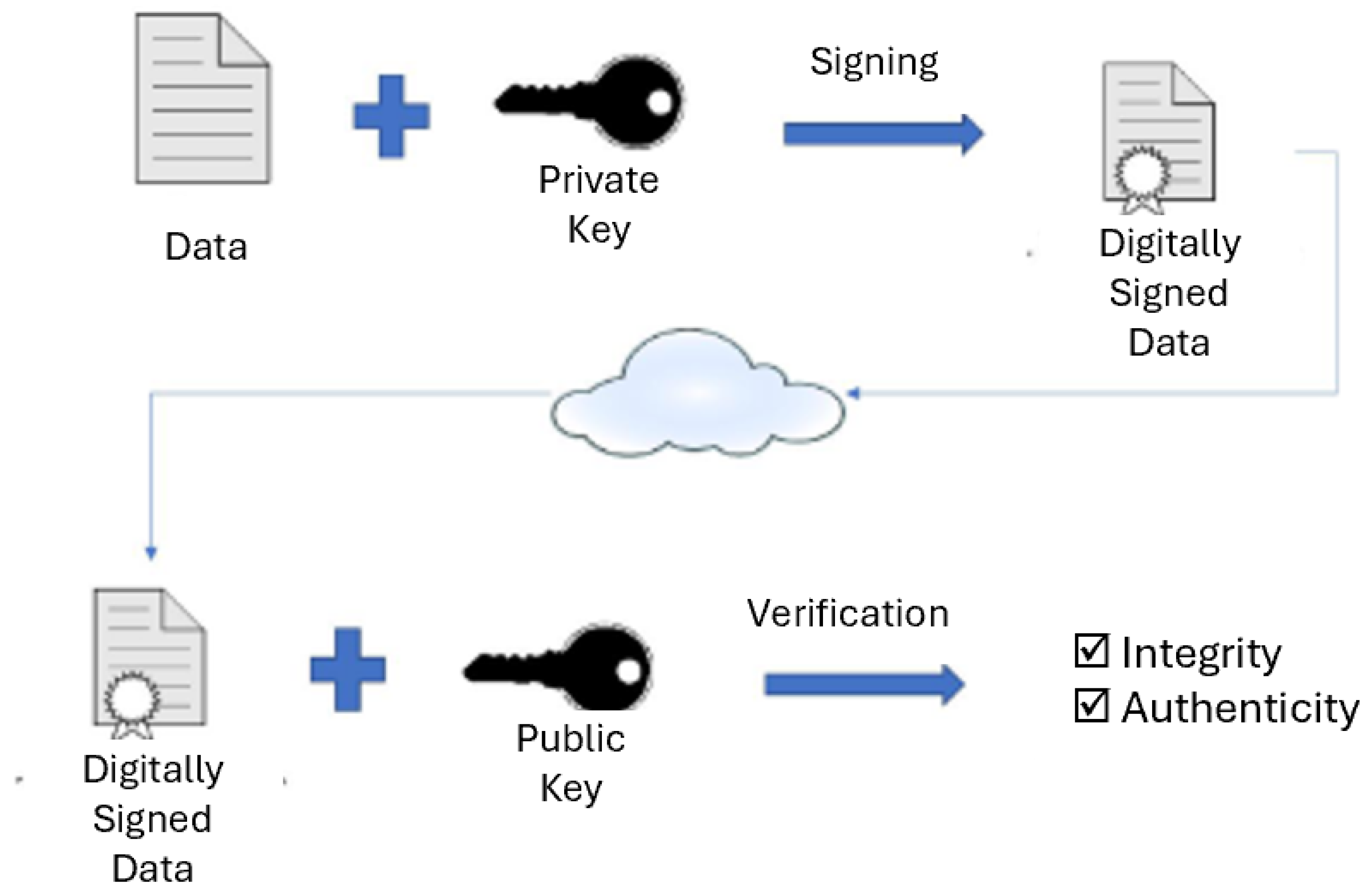

The signing and verification phases are shown in

Figure 1.

The security of the signature stems from the fact that it is impossible for an attacker to forge without knowing the private key. The signature schemes considered in this research all derive their security from the difficulty of the Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP). Although this currently remains a difficult problem, the forecast imminent arrival of stable quantum computers threatens this difficulty [

23]. The suitability of these signature schemes in the face of a quantum threat will be considered throughout this work.

2.4.1. Schnorr’s Signature Scheme

Clauss Schnorr’s signature scheme is a widely used protocol that was developed for use with resource-constrained devices and now forms the foundation for numerous signature protocols. It implements pre-processing, independent of the message being signed, to exploit idle processor time and reduce active signing time [

24].

These signatures operate within a finite cyclic group where arithmetic is performed modulo a large prime number

p. The group has a prime order

q and is generated by a publicly known element

g. Private keys and nonces are selected from the set

, and public keys are derived using exponentiation of

g modulo

p [

25].

Key Generation

The signer selects a private key and computes the corresponding public key .

Message Signing

To sign a message M, the signer performs the following steps:

- 1.

Select a random nonce .

- 2.

Compute the commitment .

- 3.

Compute the challenge value , where H is a cryptographic hash function.

- 4.

Compute .

The signature is the pair .

Verification

To verify a signature on a message M using the public key P, the verifier:

- 1.

Computes .

- 2.

Accepts the signature if and only if:

2.4.2. BLS Signatures

The BLS signature scheme is a short, aggregate signature protocol based on bilinear pairings[

26,

27]. It is particularly useful in environments where signatures need to be short, such as low-bandwidth systems. The scheme’s security relies on the difficulty of the Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) problem in certain groups, even when the Decision Diffie-Hellman (DDH) problem is easy.

The protocol operates within a pair of groups, and , of prime order p, with a bilinear map .

Key Generation

To create a key pair, a signer selects a private key, , at random. The corresponding public key is then computed as , where g is a publicly known generator of the group. In the case of BLS signatures built on elliptic curves, this results in a public key v that is a point in the group .

Message Signing

To sign a message, M, the signer performs the following steps:

- 1.

Compute the hash of the message, , where h is a full-domain hash function that maps the message to a point in the group .

- 2.

The signature, , is then computed as , where x is the signer’s private key.

The resulting signature, , is a single element in .

Verification

To verify a signature, , on a message M using the public key, v, the verifier:

- 1.

Computes the hash of the message, , mapping it to a point in .

- 2.

Accepts the signature if and only if the following equation holds:

where g is the generator of the group, e is the bilinear map, and v is the public key. This equation is a pairing-based check that verifies the signature without revealing the private key.

2.5. Secure Group Communications

One of the key challenges to enabling communication within a dynamic group is the secure distribution of a shared encryption key amongst its members. Traditional key exchange protocols such as Diffie-Hellman and Module Lattice-based Key Encapsulation Mechanism (ML-KEM) enable key exchange between a pair of clients. These pairwise connections can be utilised to implement a naive group solution, where a single client establishes a connection to every proposed member of a group and acts as a trusted dealer to share a group key.

However, this approach is time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially for large groups and those with a regularly changing membership. This approach is also dependent on the trustworthiness of the dealer. To address the limitations of this approach, a range of group key agreement protocols have been proposed. In this paper, we will show the progression from Group Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange to more scalable and secure methods such as Asynchronous Ratcheting Trees (ART) and Tree-based Key Encapsulation Mechanism (TreeKEM), which underpin modern protocols like Messaging Layer Security (MLS).

2.5.1. Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

In 1976, Diffie and Hellman’s key-exchange protocol showed how two parties (Alice and Bob) could derive a shared secret over insecure channels using collaborative exponentiation [

28]. In their protocol, the parties publicly agree on a generator value

g and a large prime number

N.

They each choose their own private secret value,

y for Alice and

x for Bob. Alice calculates her public value

a and Bob calculates his public value

b:

They exchange the public values a and b with each other and can both then independently calculate the same shared secret key, K, as follows:

Bob’s Calculation:

Since , both parties arrive at the identical shared secret key K.

2.5.2. Group Diffie-Hellman

To extend this protocol to a group setting, Steiner et al developed Group Diffie-Hellman (GDH) key exchange, which allowed additional parties to pass their shared values sequentially in a ring around the group [

29]. Each member adds their own secret exponent to the value passed from the previous member, effectively chaining the above calculations and allowing everyone on the ring to derive a shared key.

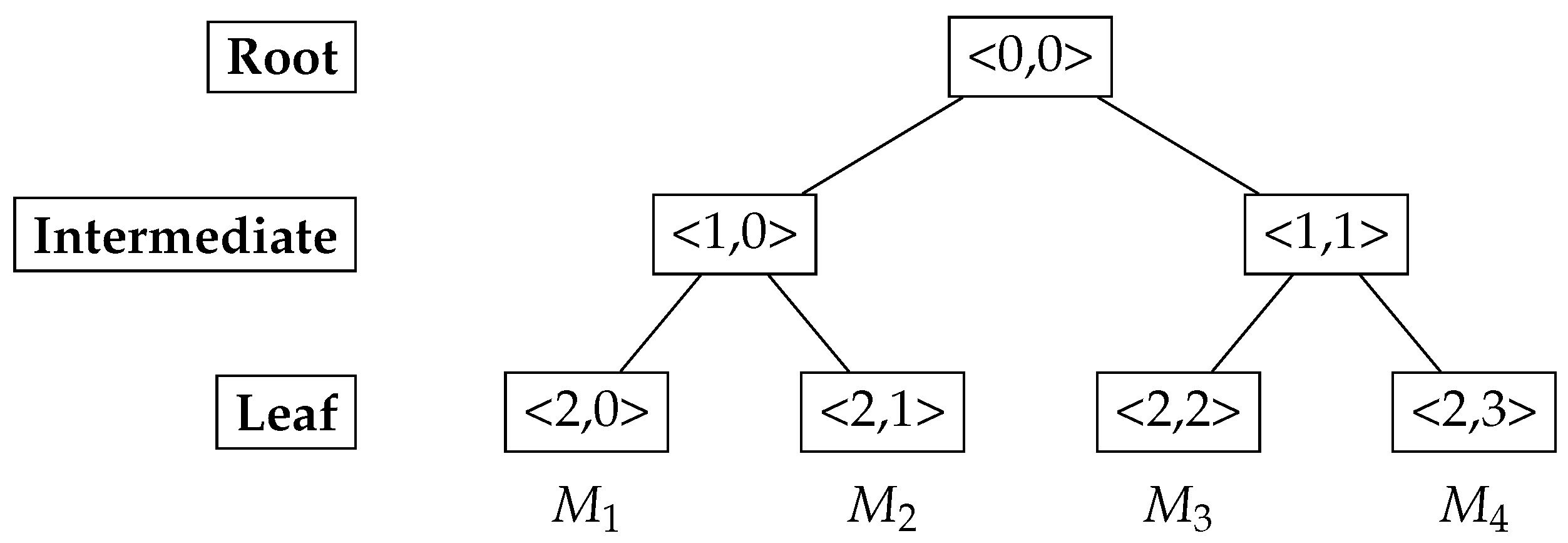

2.5.3. Tree Diffie-Hellman

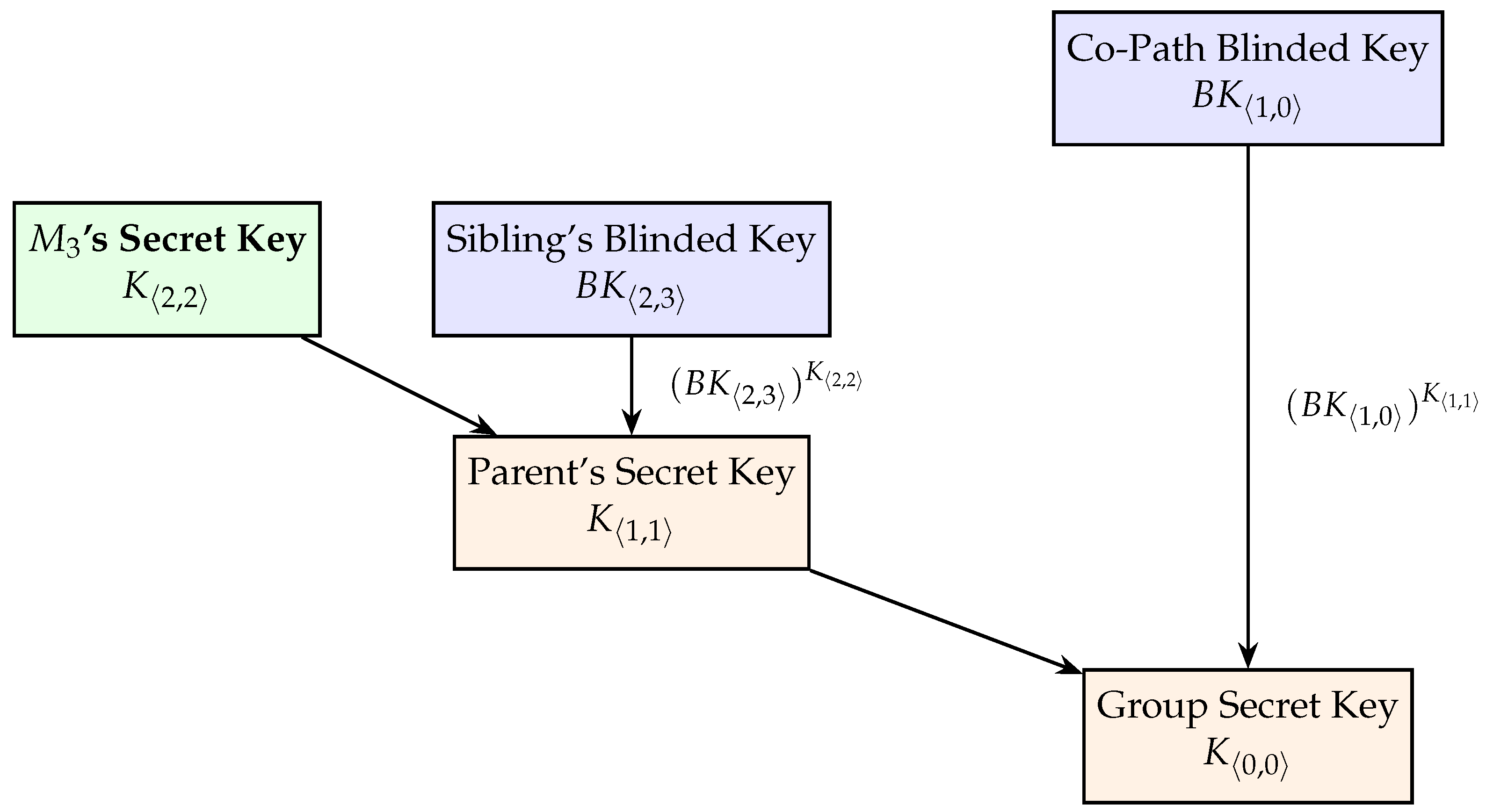

While GDH allowed the sharing of a group key, it is a sequential protocol that scales linearly (O(n)), requiring significant computational and communication resources as a group expands. Tree-based Group Diffie-Hellman protocols were developed to improve efficiency. In this protocol, group members are organised in a binary tree structure, rather than in a ring. Here, the tree is structured into leaf, intermediate and root nodes as shown in

Figure 2 (where nodes are identified by two digits that indicate their vertical and horizontal position in the tree).

Each member is assigned a leaf node, every leaf and intermediate node above them has an associated secret key (

K) and a public “blinded” key. These secret keys provide the entropy for the final group key, which each member derives independently using their secret key and the blinded keys. The blinded key (

) is derived in the same way as the public share of a leaf’s Diffie–Hellman exchange, i.e.,

To derive the group key, a node must know its own secret key and the blinded keys of its co-path nodes along the path to the root, as shown in

Figure 3. Blind keys need to be broadcast to other members of the tree to allow them to derive the group key. When a new member is added (or departs) from the group, they are allocated as a new leaf node, updating the blind keys on their path to the root, requiring all members to recalculate the Group Key.

The use of a tree structure brings a significant increase in efficiency, from linear scaling with GroupDH to logarithmic scaling (O(log n)) with TGDH. However, the ability of the protocol to handle changes to a group membership and the impact of a compromised member on confidentiality remained sub-optimal. Requiring multiple rounds of communication for updates and without the Post Compromise Security provided by other protocols.

2.5.4. Asynchronous Ratcheting Trees

Cohn-Gordon et al. [

30] highlighted the challenge of securely sharing a key for group messaging that can be scaled for large groups and can easily handle changes to group membership. Their Asynchronous Ratcheting Tree (ART) protocol was proposed as a fully asynchronous tree-based group key exchange protocol that allows clients to derive a group key without members needing to be online, that scales sub-linearly with the group size and provides robust security features, such as forward secrecy and post-compromise security.

ART defines three group operations: Join, Leave, and Update. The group is formed and expanded through a series of Join operations. No single member establishes the group key; rather, key derivation is collaborative. During an Update, a member changes their secret, allowing others to derive a fresh group key—enabling forward secrecy. Asynchronous operation is supported by an untrusted centralised server that hosts public keys and allows offline members to query updates upon reconnection. The system must maintain a strong ordering constraint to ensure consistent group key derivation.

The scheme operates in a cryptographic group G of large prime order q with a generator g, and uses a key derivation function H. The core cryptographic primitive is the Diffie-Hellman function: .

Tree Structure and Key Derivation

Group key material is structured as a binary tree:

- 1.

Nodes and Members: Each member u is assigned a leaf node. Each node v in the tree has a key pair , where .

- 2.

-

Key Derivation Path: For an intermediate node

v, the secret key is derived via the DH exchange between its children

L and

R:

This recursion continues up to the root node.

- 3.

Group Key: The group key

K is the secret key of the root node:

Update Operation (Ratcheting)

Let member u be the updater:

- 1.

Leaf Update: Member u generates a new ephemeral key pair: .

- 2.

Path Update: Member

u updates the secret keys along their direct path to the root. For each node

v on this path, where

lies on

u’s path and

does not:

- 3.

Broadcast and Key Recalculation: Member

u broadcasts the new public leaf key

and the updated public keys for sibling nodes along their path. Other members recompute the new root key:

2.6. Tree-Based Key Encapsulation Method

The ART protocol was a major step towards scalable, secure group messaging and underpins the Tree-based Key Encapsulation Method (TreeKEM). Developed by Bhargavan et al., this method uses the tree structure outlined above, but replaces Diffie-Hellman with an alternative key exchange method to reduce the computational complexity of the system and improve handling of concurrent update requests by group members [

31].

TreeKEM uses a collision-resistant hash function, a public-key encryption mechanism, a pseudo-random key derivation function, and an authenticated encryption scheme. These primitives form the foundation of the protocol’s functionality and through their elegant and sparing use, the creators achieved significant improvements over ART, particularly on recipient-side efficiency and more robust handling of concurrent updates.

The protocol defines four primary group operations: CREATE, ADD, REMOVE, and UPDATE. While the tree structure is nearly identical to that of ART, the method for deriving keys is fundamentally different.

Tree Structure and Key Derivation

TreeKEM uses a binary tree structure where members are assigned to leaf nodes. However, its key derivation method is non-contributive, which simplifies state updates.

- 1.

Nodes and Members: Each member is a leaf on the tree. Each node in the tree has a secret key and a corresponding public key.

- 2.

-

Key Derivation Path: Unlike ART, where an intermediate node’s key is derived from a Diffie-Hellman exchange between both its children, a TreeKEM node’s key is derived from a hash of the secret key of just one child, specifically the last child in that subtree to have performed an update.

This non-contributive approach is what allows TreeKEM to more easily merge concurrent updates, as conflicting operations do not require complex resolution at the cryptographic level.

- 3.

Group Key: The final group encryption key is derived from a chain of keys at the root of the tree, incorporating contributions from all updates over time to ensure security.

Update Operation

The update process in TreeKEM shifts the computational model from collaborative derivation (as in ART) to direct distribution via KEM. As an example, if member u is the updater:

- 1.

Leaf Update: Member u generates a new key pair for their leaf node, .

- 2.

Path Update: Member u calculates the new secret keys for all nodes on its direct path to the root by successively hashing its new leaf key: , .

- 3.

-

Key Distribution via KEM: Instead of broadcasting public values for others to re-calculate the path, member

u encrypts the newly computed secret keys for the other members. For each node on its direct path, it encrypts the new secret key for the corresponding sibling node. This is done using the sibling node’s public key.

This message is then sent to the members of that sibling group.

This change significantly reduces the work for receiving members. To receive an update, a member only needs to perform one KEM decryption and a series of fast hash operations, versus the multiple, more computationally intensive Diffie-Hellman operations required in ART. This makes TreeKEM more efficient, particularly for recipients.

2.7. Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Modern autonomous systems are made up of numerous components. To be resilient, they must cope not only with the complete failure of a component, but also with faulty or unreliable components that provide erroneous signals, or components that have been compromised by an adversary and are being directed to provide deliberately harmful signals[

32].

A useful metaphor for this situation is the Byzantine Generals Problem. Here, we imagine several divisions of the Byzantine Army surrounding a city. Each division is commanded by a general, and the generals are connected to each other by messenger. The generals may be loyal or they may be traitors, with the traitors seeking to prevent the loyal generals from agreeing on a successful plan of attack.

Lamport et al. [

13] proved that in such a situation, a simple majority vote would be insufficient to ensure that an honest majority could reach consensus in the presence of Byzantine faults. With

oral messages—where a general can send conflicting messages to different recipients—a system with

m traitors requires at least

total participants to achieve consensus. When

signed messages are used—ensuring authenticity and integrity—a system can tolerate up to

traitors, provided that honest nodes can communicate either directly or indirectly with one another.

These theoretical limitations directly impact the ability of Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS) and (DKG) schemes to tolerate Byzantine faults. Asynchronous systems, where paths between nodes are not guaranteed, can behave like systems with oral messages and are typically limited to fault tolerance of , where m is the number of traitors and n is the total group size. For systems with public commitments or signed messages, that tolerance increases to .

3. Related Work

The development of these cryptographic primitives into mature libraries and algorithms has taken many years and seen numerous weaknesses identified and mitigated. This section will chart some of these developments and provide a clear understanding of the current state of the art within the fields of group key distribution and threshold cryptosystems, with a focus on their applications within distributed systems, such as UAS.

3.1. Key Distribution in UAS

As research into Internet of Things (IoT), Internet of Vehicles (IoV), multi-vehicle UAS swarms and systems that combine all three has developed. The challenge of providing secure communications between devices to enable autonomy has been approached in multiple different ways, largely driven by the underpinning architecture and its constraints. These approaches have adopted both purpose-built designs as well as adapted pre-existing protocols; the efficacy of these approaches and lessons for the development of our implementation are outlined next.

Although the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to both sides using commercial cellular technology to provide C2 links for their UAS, [

33,

34], Abdalla et al. [

7] highlight the difficulty of securing cellular networks to enable civilian UAS operations. However, their work focuses on UAV to Ground Control Station (GC) connections, and suggests authentication and latency times that would be unsuitable for drone-to-drone communication. What is more, for UAS intended to operate in a degraded or denied EM environment, reliance on an adversary’s cellular network would be a serious tactical weakness.

3.1.1. A Centralised Approach

Noguchi [

35] devised a key-sharing system that utilised Shamir Secret Sharing to achieve an order of magnitude improvement in encoding times compared to RSA for resource-constrained devices (Raspberry Pi 3s). The approach relied on a trusted central architecture and pre-shared secrets to authenticate devices, with no authentication by the management nodes to verify user devices. This shows that the very lightweight approach to authentication and the use of Message Queuing Telemetry Transport MQTT, which is common for constrained devices, would not be suitable for our use case. Their methodology identified key performance metrics that were visible in multiple papers, namely encoding delay, reconstruction delay and total key-sharing delay.

Building on a more robust architectural model, Tan [

36] approached the challenge of group key distribution in an innovative way, with a trusted dealer using certificateless authentication, disseminated during a configuration phase by a central Trust Authority pre-flight, to verify nodes. Similar to Shamir’s sharing scheme, their proposal utilises the mathematical properties of polynomials, but this time employing the Chinese Remainder Theorem CRT to enable individual reconstruction of the group secret key. Their approach depends on a powerful tethered UAV as the trusted dealer, removing the power limitation inherent to most UAS swarms. While this is feasible for enabling devices in an Internet of Vehicles IoV architecture, it is absolutely unsuited to our use case.

3.1.2. Shifting to Decentralisation

Mitigating the reliance on a single management node, Wang et al [

37] expanded the CRT polynomial technique with the addition of a token system. This reduces the computational overhead of the system and gives it greater utility across a wider range of UAV use cases; however, for larger swarms (100+), the token size would remain very large in order for the CRT to function correctly. A multi-stage, threshold approach to authentication included Shamir Secret Sharing to provide added resilience, but requires a threshold of management nodes to be operational during authentication. The batch injection of certificateless identities expedites configuration times and has merit, but constrains the ability for nodes to be added on an ad-hoc basis if a mission unexpectedly needed a capability that had not been included during the configuration phase.

Moving away from purely cryptographic solutions, Jangsher et al’s [

1] approach was to introduce dedicated hardware to their system (Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) and emulators (PUFe’s). During a configuration phase, devices are provided with the digital fingerprint for a cohort of devices. Multiple overlapping cohorts will form a swarm. During key sharing, a pair of devices initiates a connection, using the PUF and PUFe to verify each other. The devices then create a pairwise key to secure their connection using a physical measurement of their link (i.e signal strength or similar). One device at a time, UAVs are added to the swarm, and gradually, the group’s shared key is formed. The use of PUFs and physical measurements removes the requirement for Public Key Cryptography (PKC), reducing the cryptographic computation required by the devices. However, the time to form a swarm increases linearly with its size and can stall with mid-sized groups (those over 10).

In contrast to hardware-dependent models, Yang [

38] proposes a Group Authenticated Key Exchange protocol based on Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman ECDH and authenticated using Boneh-Lynn-Shacham BLS short signatures. The protocol utilises authentication to mitigate Man In The Middle MITM attacks and the authors highlight its relevance to UAS Swarms, where devices may be captured by an adversary or temporarily lost. However, it uses a member of the group to act as the Group Controller (GC), which then coordinates the key generation and update process. The cryptologic burden of creating keys and then distributing them securely is placed on the GC, and this becomes a significant challenge for larger swarms that have a dynamic composition with significant churn.

3.1.3. A Modern Group Authenticated Key Exchange Protocol

Taking a broader perspective, Leon and Britt reviewed eight open and proprietary protocols to assess their suitability for use in military Unmanned Systems [

39]. Due to its provision of FS, PCS, support for asynchronicity and logarithmic scaling efficiency, MLS was assessed to be the most suitable. MLS was successfully tested with a small three-member group of UAS and USV (Unmanned Surface Vessel), proving the utility of the protocol in this environment. The study identified a number of areas for future work that limited the resilience of their implementation, specifically with their manual approach to Authentication and Delivery Services.

During the development of MLS, Wallez et al. proved the ability of MLS to robustly maintain group authentication and integrity, making it highly suitable for use by UAS operating in a contested environment [

40]. Specifically, the ability of the protocol to ensure all legitimate members have a consistent and authenticated view of the group’s membership is resilient to an attacker attempting to insert an illegitimate member and is capable of securely handling a high rate of member turnover/churn.

Finally, offering the most comprehensive solution for dynamic groups, Marstrander’s [

41] research took a different approach, exploiting the IETF ratified Message Layer Security (MLS) Protocol and existing libraries and applications to develop the Flamingo MLS system for key management within meshed UAS networks. MLS utilises the TreeKEM scheme for securely generating encryption keys across large groups. While still requiring centralised nodes for a coordinating function, the cryptographic load is distributed across the nodes, minimising the computational load on a single device. It is commonly used within secure messaging apps to protect group chats, and is optimised for the rapid distribution of keys across large group sizes and can robustly handle both frequent addition and revocation of group members. Marstrander’s work, grounded in the reality of military UAS operations, recognised the challenges of identifying a compromised node, the requirement for a decentralised consensus mechanism to respond coherently to compromised nodes and proved a decentralised DS using the Totem protocol. This novel study proved the utility of MLS on a small network of resource-limited devices, while identifying a number of limitations within their experiment that warrant further investigation.

3.2. Threshold Cryptosystems

Among many possible applications, threshold cryptosystems can form the foundation for secure consensus or voting, as they allow a threshold t out of n members to jointly complete a cryptographic operation — for example, applying a digital signature to a proposal. A common way to realise such systems is through polynomial-based Distributed Key Generation (DKG), which ensures that no single party ever learns the full private key. On top of this shared foundation, different signature constructions can be used to enforce the threshold property. This research focuses on two specific approaches: bilinear-pairing-based signatures, represented by BLS, and Schnorr-based protocols, represented by FROST.

NASA’s Ames Research Centre’s SAFE50 Autonomy Reference Architecture defines the extensive range of hazards, environmental effects, and operational considerations that necessitate a consensus approach [

42]. Overall, the UAS must navigate an environment filled with static and dynamic objects in three dimensions, all while contending with environmental challenges and potential system failures. In our conceptual architecture, multiple devices will provide different sensor capabilities and perspectives. While SAFE50 does not propose specific cryptographic mechanisms, this work highlights threshold signatures as one potential means of increasing confidence in the decisions being made by autonomous UAS.

3.3. Distributed Key Generation

The starting point for these systems is DKG.

Section 2.3 showed that Pedersen’s development of DKG enables a group to jointly create a key pair without relying on a centralised trusted dealer. The core of the protocol is that each participant generates a random polynomial of degree

, where

t is a predefined threshold (equal to

n in the original theorem). By reducing

t, any quorum of at least

t participants can work together to perform cryptographic operations—without ever reconstructing the private key in full. This scheme can tolerate up to

malicious parties, where

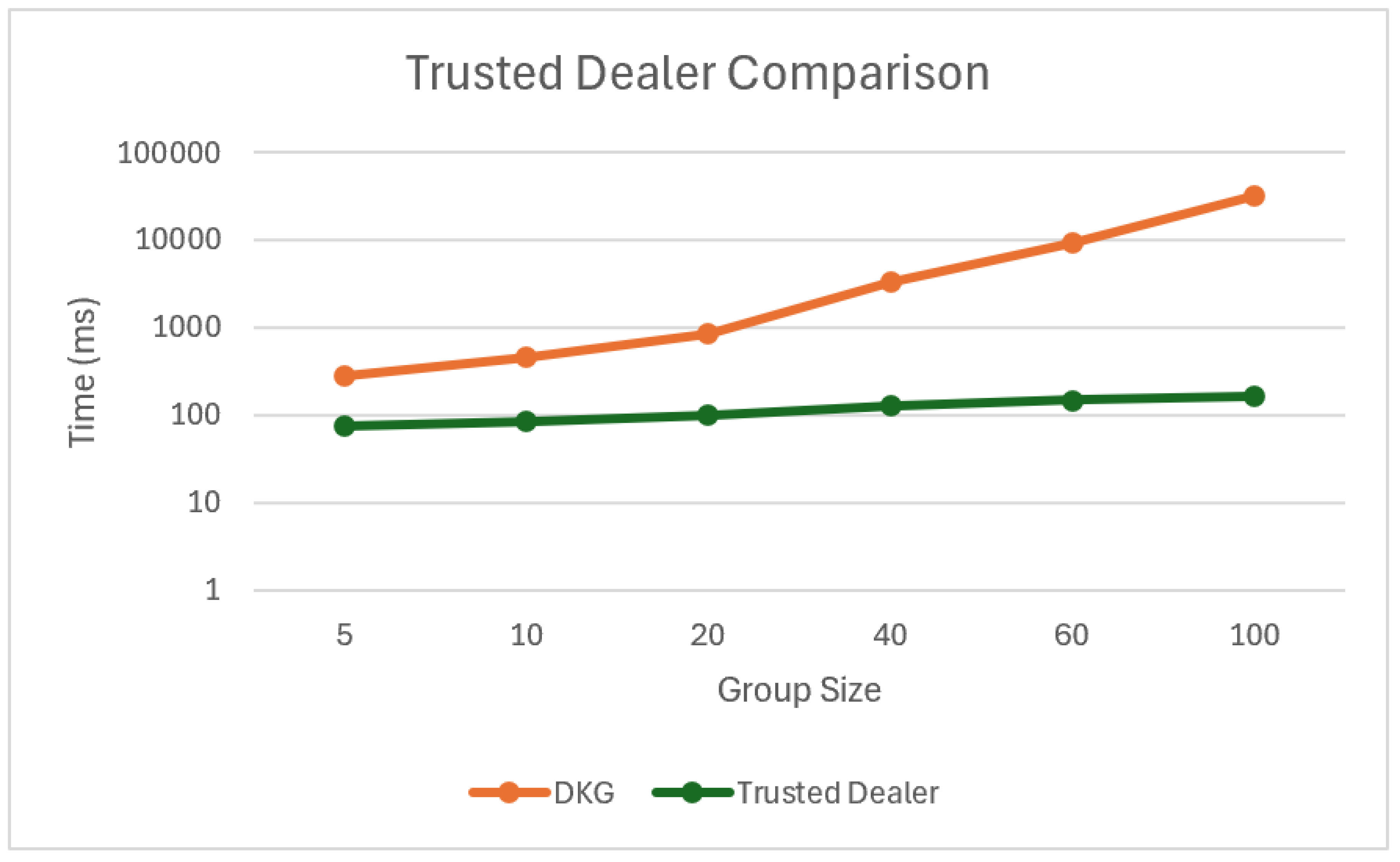

m is the number of malicious parties. As with all DKG protocols, multiple rounds of communication are required to ensure honest behaviour. While this decentralised approach aligns with our design objectives by removing any single point of trust, it is more costly in terms of communication and setup time compared to the trusted dealer model. This trade-off will be highlighted during the benchmarking process, where both decentralised DKG and trusted dealer configurations are evaluated, with libraries supporting them.

3.4. BLS Signing

While Pedersen’s DKG relies on polynomial secret sharing for key generation, in 2003, Boldyreva extended the BLS signature scheme to apply a similar threshold principle using bilinear pairings. In this pairing-based approach, each participant chooses a random secret value and computes a public commitment . The group public key is the product of all individual public commitments. As with the polynomial-based scheme, the full private key is never reconstructed.

To sign a message

M, each of the

t participants computes a partial signature using their private share:

The final signature is aggregated by multiplying the partial signatures:

To verify, a verifier checks:

This BLS threshold scheme tolerates up to

malicious parties, which is the theoretical optimum and functions with a single round signing phase, an improvement over the multiple rounds needed by other schemes. However, the pairing function required for verification and aggregation is computationally intensive[

43].

3.5. FROST Signing

BLS offers a single-round signing phase (albeit with computationally expensive pairing operations for verification and aggregation), whereas earlier robust threshold Schnorr protocols, such as those described by Gennaro et al., required three signing rounds [

44].

These signing rounds are a significant cost for resource-constrained networks. Komlo and Goldberg sought to design a threshold signature scheme that maintained security while improving performance [

45]. Their Flexible Round-Optimised Schnorr Threshold (FROST) signatures improved the state of the art and showed it possible to have either a two-round signing protocol, or a single-round signing protocol with pre-processing and a centralised, semi-trusted signature-aggregator (due to better alignment with our design objectives, we will focus on the decentralised version).

The FROST protocol consists of three main stages: Key Generation, Signing and Verification. FROST typically employs Pedersen’s DKG with an added Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) to protect against rogue-key attacks, to provide participants with a long-lived secret key share and produce a public key that is known to all participants.

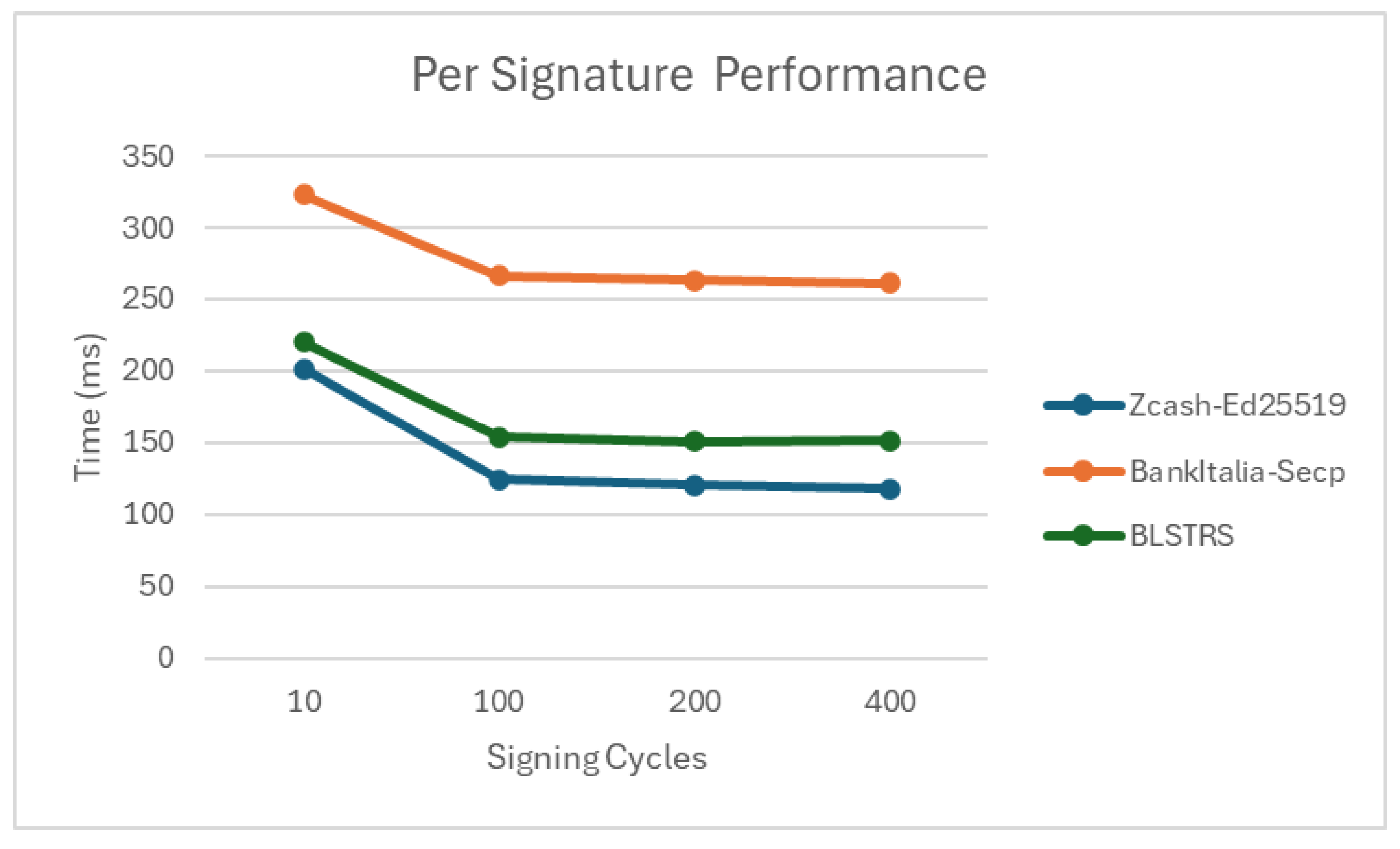

In the first round of signing, each participant generates two single-use nonces and their corresponding public commitments. The commitments are broadcast to all participants. In the second round, the broadcast commitments are used to calculate a group commitment and a binding value that ties the message, participants and commitments together. They then use their secret share, nonces and the binding value to compute their signature share. The signature shares can then be broadcast and aggregated into a final group signature. Verification is identical to the single-party Schnorr signature verification method. In summary, BLS minimises interactive latency at the cost of expensive pairing-based verification, while FROST reduces computational load but requires an additional round of communication. Both schemes were therefore selected for benchmarking to evaluate how these trade-offs manifest in practice.

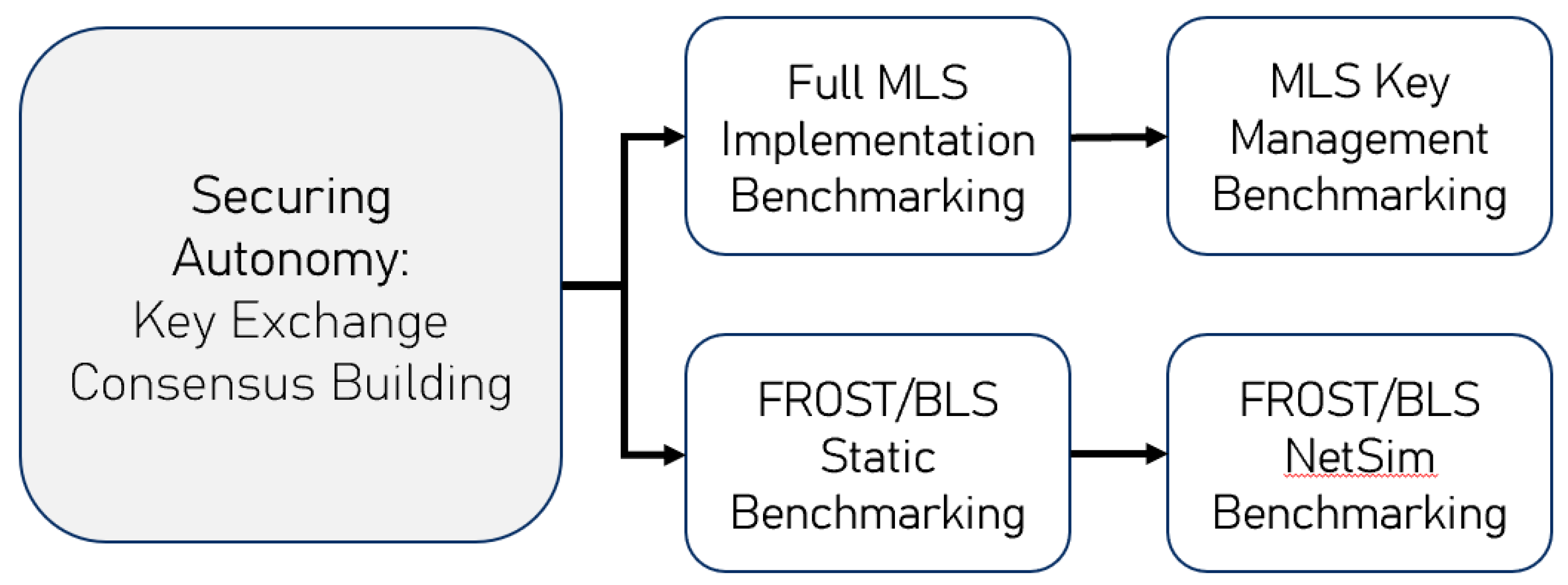

4. Methodology

This section applies concepts from the literature review to the performance benchmarking of MLS and threshold signature libraries. These protocols may address two challenges relating to security within autonomous UAS — encryption key generation/distribution and consensus-based decision making. The benchmarking aims to identify suitable libraries for use in a related project and evaluate their performance under conditions relevant to a UAS network. A high-level outline is shown in

Figure 4 .

This paper will focus on the computational efficiency of the libraries under test, the impact of network performance on their operation and the optimum way to utilise them. It will use a range of benchmarks that sequentially run through the operations of a protocol, allowing their performance to be accurately measured. As the communication pattern for FROST and BLS varies, a dual approach of static and network-simulated benchmarks is used. In this way, the "computation time" and "communication time" can be separated and analysed [

46,

47,

48].

4.0.1. UAS Concept of Employment

The wider project is developing a UAS cloud architecture that will create a meshed network with utility across a range of applications. The intention is for swarms ranging in size from 5-100 to be able to operate with significant autonomy, either through choice or as a result of lost C2 links. It is anticipated that individual UAVs will join or leave the swarm during a mission if a particular capability is required, and the network will be able to adapt gracefully to these changes.

4.0.2. Design Requirements

Although the project considers two different technologies/protocols, there are common design principles for both:

- 1.

Decentralisation is a priority, but an initial centralised configuration phase is acceptable.

- 2.

A majority of nodes will be available during the configuration phase.

- 3.

Security must be maintained if a UAV is permanently lost

- 4.

A UAV can be temporarily out of communication and seamlessly rejoin the network.

- 5.

The UAS network must function without a connection to the C2 or configuration node during normal operation.

4.0.3. Test Environment

The specification of the hardware solution for the wider project was not available prior to testing. Therefore, all the benchmark tests were run on a virtualised Linux system - Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12450H processor. The instance was allocated 12 logical processors (6 cores with 2 threads per core) and 7.6Gi of RAM. This configuration provided ample computational resources and memory for the test suites and ensuring the performance results were a valid measure of the libraries’ efficiency.

4.1. MLS Benchmark Design

The requirement was for a protocol that could support group key distribution over 100 + clients in order to enable secure broadcast messaging required for threshold signature schemes (and other applications requiring encrypted messaging between nodes). The selected protocol needed to be well-proven from a security perspective, future-proof, and be able to support the addition and subtraction of clients during a mission. It should be capable of running with as much decentralisation as possible. The IETF MLS protocol has been shown to meet all these requirements.

4.1.1. High Level Operation

Users of MLS are referred to as clients and are organised into Groups and Epochs. A group consists of two or more clients and the epoch defines the current chronological state of the group. The clients within a group agree on a common secret epoch key, using a tree-based sharing structure (Tree-based Key Encapsulation Method).

TreeKEM shares the epoch key, which is then used by each client to individually derive a ’Secret Tree’. This structure allows a client to locally derive a unique, symmetric key for each message they send, using a Key Derivation Function (KDF) with their branch of the Secret Tree and a message sequence number. Message encryption can either be done using the MLS framing layer or by exporting a key for use within another application. Messages sent through the framing layer are protected with a per-message encryption key and are also signed by the sender, assuring the confidentiality, integrity and authenticity of the message. Use of the key export function loses the additional assurance of per-message signatures, but allows applications that MLS does not support, such as streaming Full Motion Video (FMV), to still utilise the Group AKE functionality.

TreeKEM solves the scalability problem faced by the trusted dealer model. It allows clients to hold keys for the nodes on its path to the root. When an update occurs, only a portion of the tree needs to be re-encrypted and re-distributed, not the entire key. This reduces the complexity of operations from linear to logarithmic with group size, making it far more efficient for large groups than a trusted dealer. The ability of an MLS library to realise these benefits and the comparative performance of different libraries is the focus of this research.

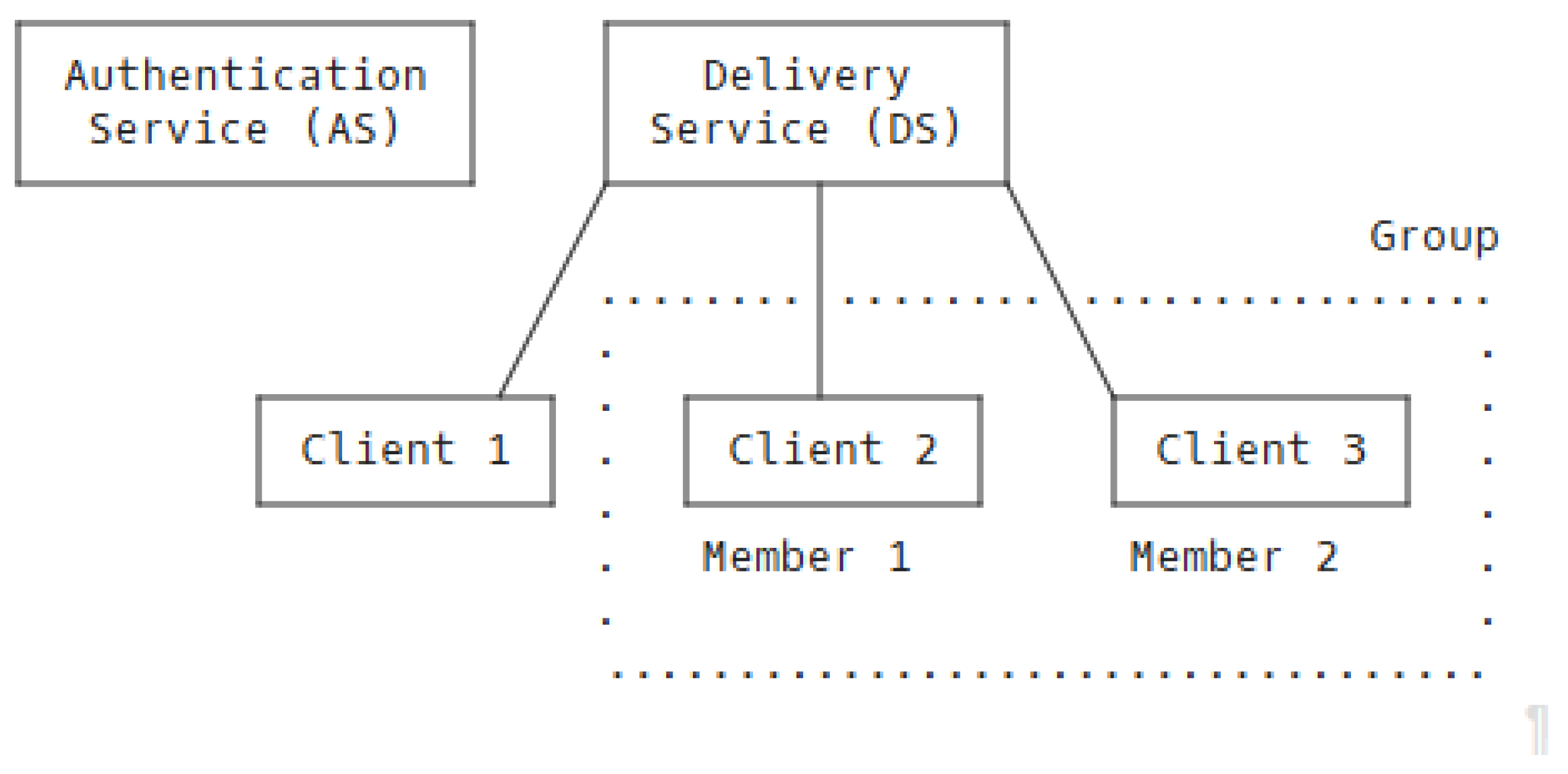

4.1.2. MLS Architecture

A simple MLS architecture is shown in

Figure 5. The protocol relies on the availability of an Authentication Service (AS) and a Delivery Service (DS). The AS allows a client to authenticate credentials presented by another group member, or a proposed group member and the AS is assumed to be a trusted entity.

The MLS RFC supports the use of PKC as an acceptable means of implementing a DS, and this approach is compatible with our pre-mission configuration phase concept. The DS is responsible for managing group membership, the scheduling of key updates (epoch changes) and for routing messages amongst the group for messages sent within the MLS framing layer. Within the MLS protocol message, ordering is critical for success, and the DS is the key component to enable that. When employed in a mobile messaging app, this would be a fixed server. This centralised approach could be replicated within our UAS architecture, with replication providing resilience to a DS becoming unavailable. However, the RFC supports the concept of a decentralised peer-to-peer DS, and previous work by Marstrander [

41] has shown this to be feasible. His implementation is publicly available as a proof of concept and would provide a starting point to develop a DS for a specific architecture and hardware configuration.

4.1.3. MLS Operations

This extensive capability, defined in IETF RFC 9420, is provided by a complex arrangement of binary tree structures and multiple encryption keys. The foundational theoretical concepts are discussed in the preliminary chapters, and a full explanation can be found in the RFC [

49]. However, to understand the research undertaken within this project, a deeper understanding of the following operations will be beneficial:

- 1.

Group Formation This is a computation and communication-intensive process for large groups and should be completed during the pre-mission configuration phase. This operation establishes the binary tree structures, populating the leaf nodes with identity information and initial key material that produce the epoch and synchronous keys.

- 2.

Add Member This operation tests the cost of integrating a new client into an existing group’s tree structure. It generates an Add proposal for the new client, creates a Commit message for the proposal, then re-computes the groups tree to accommodate the new leaf node. Finally, it generates a Welcome message for the new client. This contains all the cryptographic material they would need to join the group and be part of the current epoch.

- 3.

Remove Member This operation tests the costs of removing a client from a group and updating the remaining members. It generates a Remove proposal for the target client. Then creates a Commit message that includes this proposal and then recomputes the cryptographic tree to remove the target client’s leaf node.

- 4.

Update Member This operation tests the cost for a single client to initiate an update. This has the effect of shifting to the next epoch and rekeying the system. It generates a new private-public key pair for the client. Recomputes the member’s cryptographic data and updates its leaf node in the tree structure. Constructs a Commit message to update the group.

- 5.

Process Update This operation tests the costs for a client to receive and apply an update message. When the client receives a Commit message, it must process it to synchronise its group state. The client must authenticate the Commit message by verifying the signatures within the message, then recompute and update its local copy of the group’s cryptographic tree to reflect the change. Derive the new group keys for the next epoch.

- 6.

Protect Message This operation tests the cost for a client to encrypt a message for the group. This requires the client to generate an encryption key using the Secret Tree, encrypt the message and then sign the message.

- 7.

Unprotect Message This operation tests the cost for a client to decrypt a message sent by another member of the group. This requires the client to generate an encryption key (as per Protect Message) and then use it to decrypt and authenticate the message.

- 8.

Key Export This operation tests the costs for a client to generate a symmetric encryption key and present it via an API call for use by another application. It generates this key from the Secret Tree. This is computed ’locally’ by the client, requires no inputs from other clients and is a relatively efficient operation.

4.1.4. Library Selection

The MLS Working Group maintain a list of active MLS libraries [

50]. The Cisco MLSpp library has been proven to work on a UAS network in previous work [

41], so a second library was selected for comparison. The aim is to identify a library less susceptible to the performance issues Marstrander had identified. At the time of selection, OpenMLS was the most recently updated and provided a professional level of documentation and example code. This would provide a reliable way of creating two high-quality benchmark test harnesses to measure the library’s cryptographic performance.

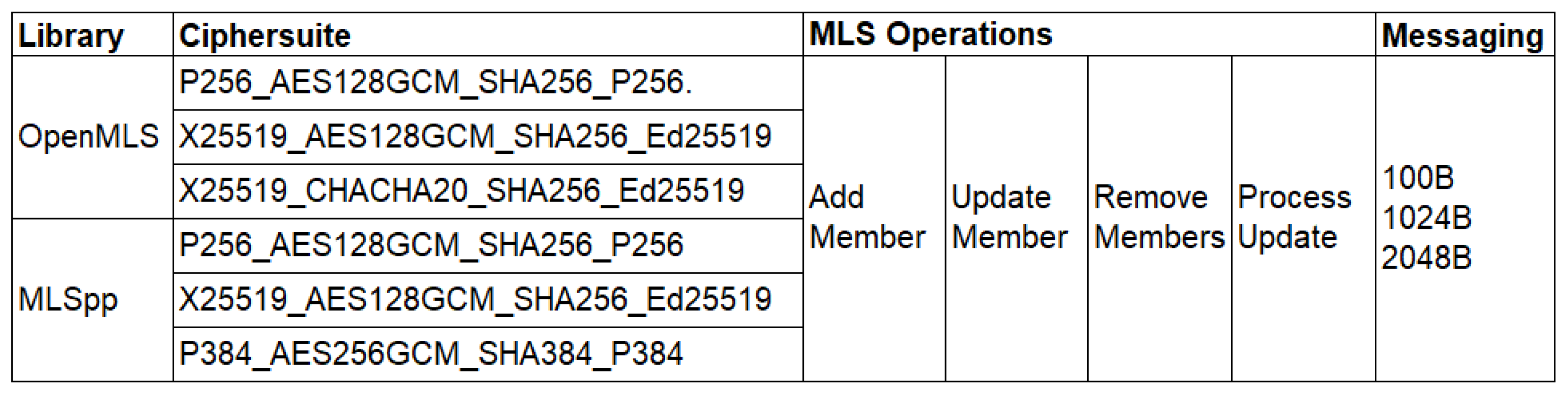

4.1.5. Benchmark Variables

Following an initial familiarisation period to ensure the libraries performed as expected and functionality was fully understood, a test plan was developed. For each implementation, this would test a range of cipher suites across multiple group sizes and measure the time taken to complete four group management operations and three messaging operations.

Figure 6 shows the test variables.

4.1.6. Benchmark Tests

The benchmarks were designed to assess the performance of each library in two modes. Full MLS functionality - where MLS is used for key management and message encryption. Key management mode - where the MLS key export function is used to produce symmetric encryption keys.

The full MLS functionality benchmarks completed the following:

- 1.

Configure a group (sized 10,20,50,100)

- 2.

Complete an add member operation

- 3.

Complete a remove member operation

- 4.

Complete a update member operation

- 5.

Complete a process update operation

- 6.

Complete a protect message and unprotect message operation for a message (sizes 100B, 1024B, 2048B).

The key management mode benchmarks completed the following:

- 1.

Process an export key request

- 2.

Use the symmetric key to encrypt a message (sizes 100B, 1024B, 2048B)

- 3.

Use the symmetric key to decrypt a message (sizes 100B, 1024B, 2048B)

The unit of cost for these operations is the time taken to complete them. Care was taken for only the time required for the actual operation to be measured. As both libraries implement the same protocol, the benchmarks test how efficiently they implement the protocol. There is no transport layer activity or difference in messaging complexity, so no attempt was made to simulate network activity.

4.1.7. Benchmark Development

All the benchmark tests were run in the previously defined WSL environment and code was written within nano via the WSL command line. AI assistance in the form of Google Gemini was used to iteratively develop the benchmarks and troubleshoot errors. Functional design, validation and analysis were carried out by the researcher. The developed code provided a test harness to manage the input/output of variables into MLS library functions and manage the benchmarking process. A working benchmark was created for the first library and it was used as a template for the second. The benchmark code used during this research and example prompts are published on GitHub [

51].

The Rust-based, OpenMLS library is supplied with ’Large_groups.rs’ example code. This was used as the foundation of our benchmarks and provided a sound understanding of how the OpenMLS library should be used. The code was then modified to utilise Rust’s Criterion crate to apply a more rigorous timing and sample management framework and the send message functionality was created. This was then used as a template for the creation of the MLSpp benchmarks in C++.

In total, four benchmark codes were developed that tested the cryptographic efficiency of two MLS implementations with six cypher suites and groups sized from ten to one hundred. The results showed the impressive scalability and flexibility of the MLS protocol and provided a clear performance comparison between the two libraries. The second half of this research builds on the secure channels established by MLS, considering a different cryptographic problem: proving consensus on a decision within the group.

4.2. Threshold Signature Benchmark Design

In order to verifiably make consensus-based decisions across an autonomous UAS swarm, a method is required to obtain the consent/approval of a threshold number of participating UAS nodes. Threshold signatures provide a mechanism for a node to ’vote for’ or securely approve a decision and then for the wider network to only implement that decision if a pre-defined quorum of nodes concur. From the literature review, FROST and BLS signatures appeared best suited to our application:decentralised networks, high group turnover rate, unreliable communications. Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm ECDSA was ruled out due to the complexity of implementing threshold signatures with this algorithm.

Signature performance is driven by curve, protocol and library language. Of these, the chosen protocol drives the message complexity - how many messages the system must send to generate a distributed key or sign a proposal.

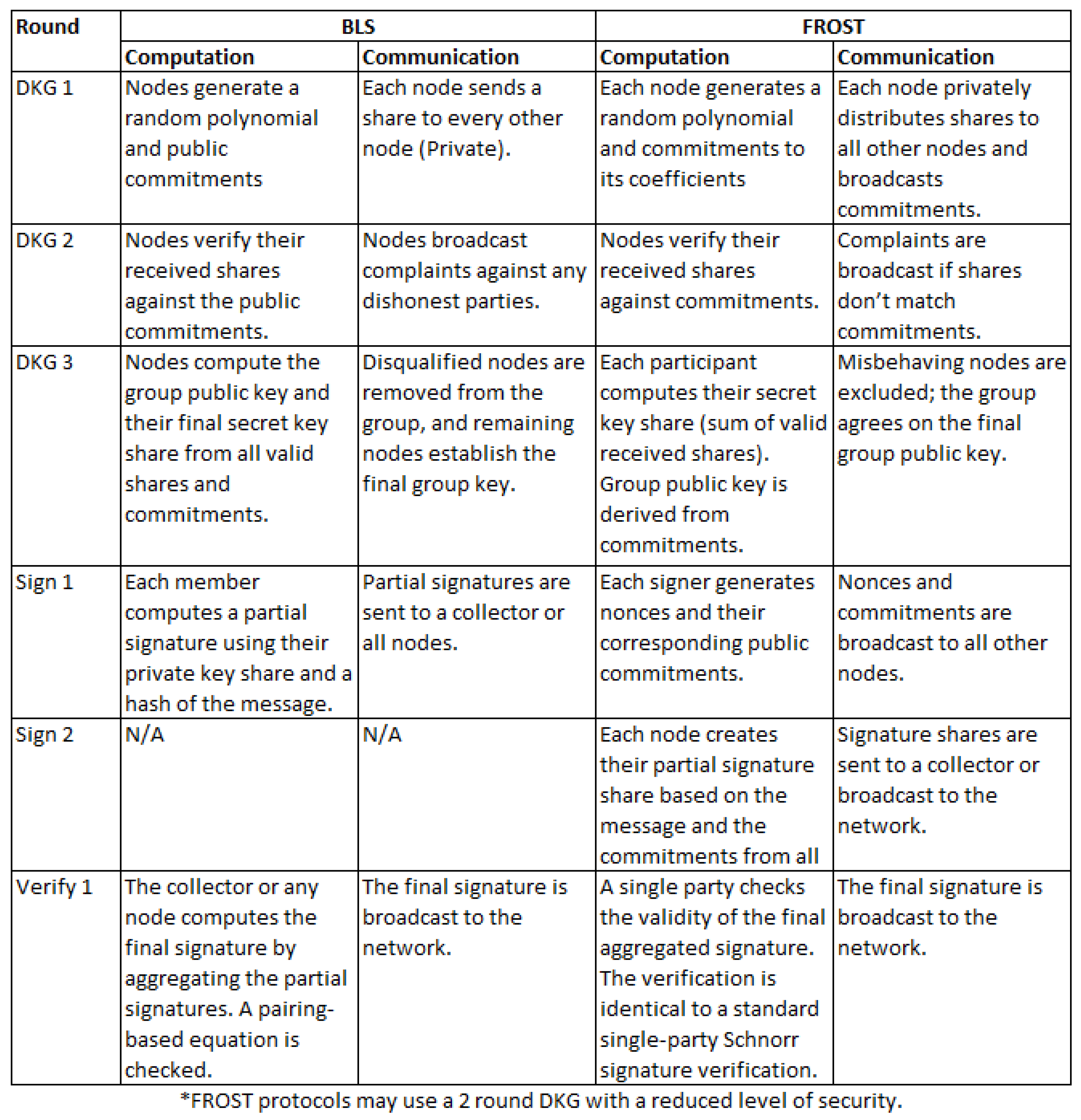

Figure 7 compares each protocol’s computation and communication processes.

4.2.1. Library Selection

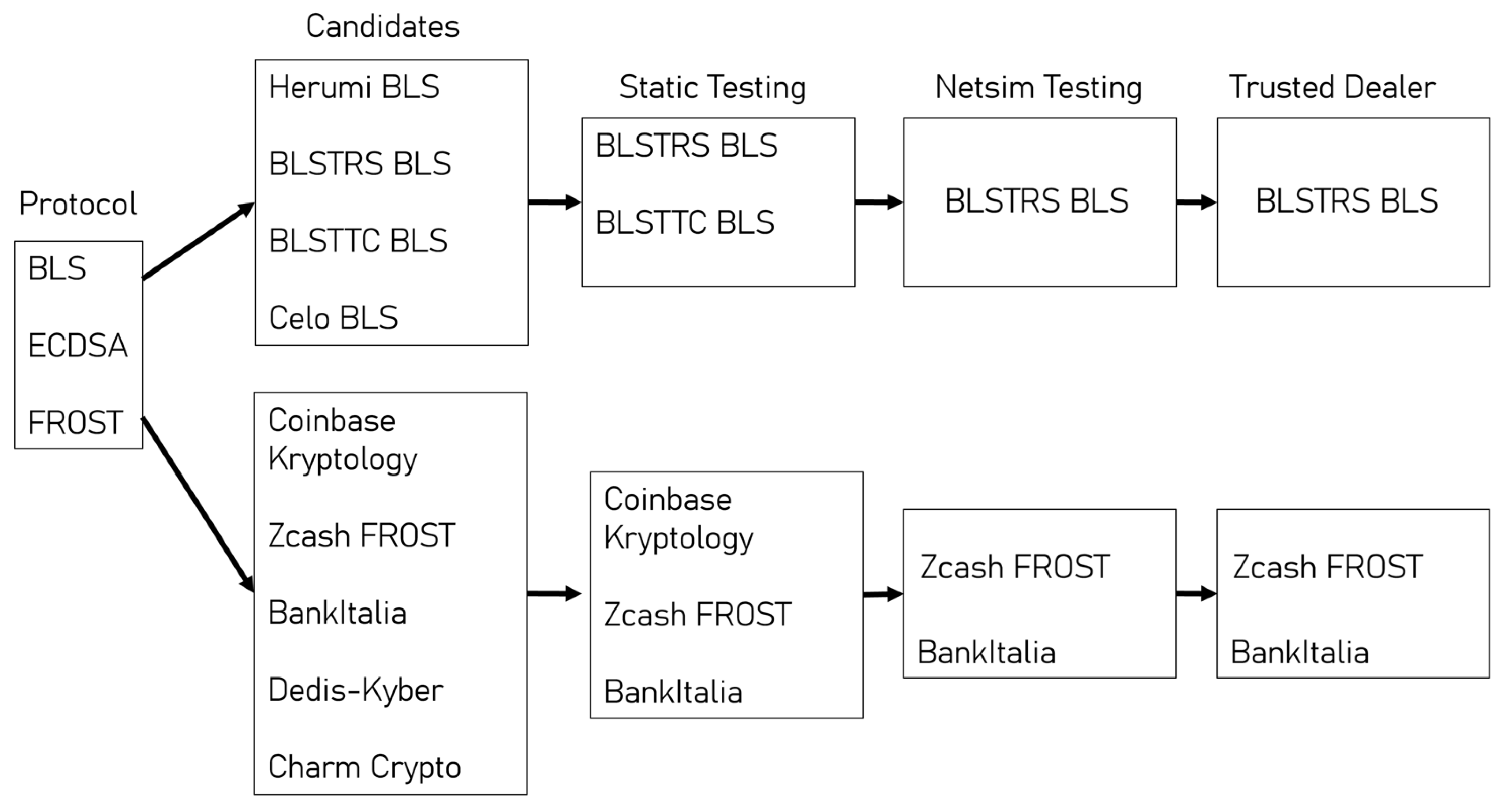

Figure 8 shows the initial candidate libraries and the incremental approach taken to developing these benchmarks to ensure reliable data across all aspects of performance were obtained.

Starting with static benchmarks that isolated the library’s cryptographic functions and ran tests that would allow a comparison to be made of both the library and the protocol’s computational efficiency. Network simulations (netsims) shift from a sequential to a concurrent approach and introduce network latency and loss, providing a realistic simulation of real-world performance. Only the three best-performing libraries were progressed to this stage. This reduced the development burden while maintaining coverage of protocols and cryptographic curves. The benchmarking process was iterative. After conducting the initial single-cycle netsims, the results indicated that the high, one-time cost of DKG was a significant performance bottleneck. To better reflect a realistic use case, where a single key is reused for many signatures, an additional bulk signing benchmark was designed and implemented. Finally, where trusted dealer functionality also existed in the library, the benchmarks were re-run. Allowing the performance cost of the decentralised key generation to be quantified.

4.2.2. Benchmark Variables

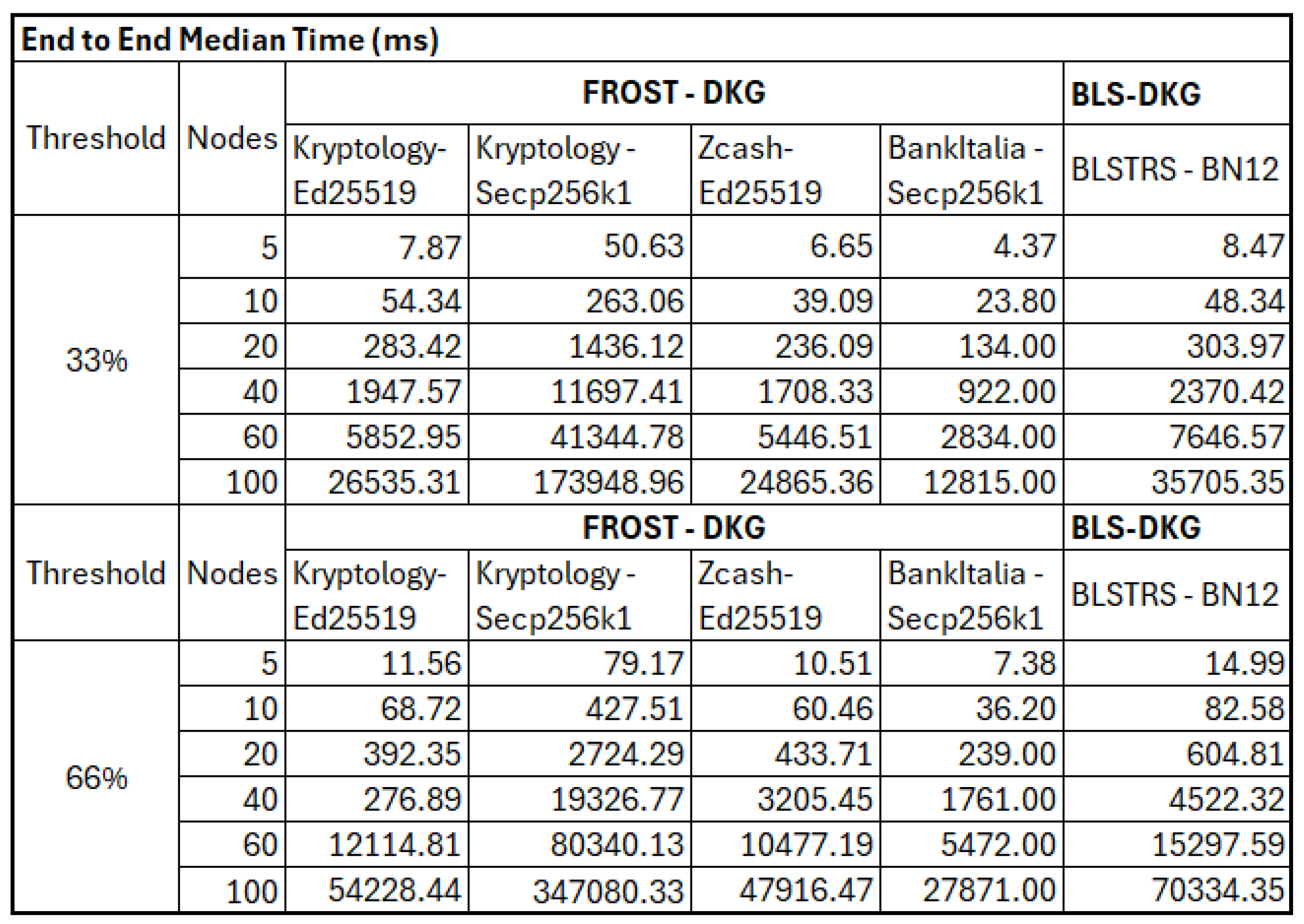

The variables tested during the static benchmarking process were group size and threshold number. With groups of 5, 10, 20, 40, 60 and 100 all tested with a threshold size of 33 % and 66 %. The group sizes are relevant for a range of tactical and operational use cases and within the scope of the parent project. The thresholds model two scenarios. The first is a highly contested operating environment, where a large number of UAS may be unavailable (due to attrition or signal jamming/obstructions), leading to a requirement for a lower threshold to ensure a quorum. Alternatively, the lower threshold may be deemed sufficient for the type of proposals being approved, in which case the reduced threshold would be expected to improve performance. In the second scenario, a higher threshold is applied, and this could reasonably be expected for decisions that create a risk to the mission (loss of a key capability) or risk to life, trading performance for additional confidence in a proposal’s approval. A summary of the tested libraries is in

Table 1.

4.2.3. Benchmark Tests

For each library benchmarked, the following operations would be tested:

- 1.

DKG Measuring time to generate a group key and provide each participant with their share of the secret key. Expected to be the most resource-intensive operation and required during swarm configuration or when adding a new node.

- 2.

Signing Measuring time to generate a threshold signature. Expected to be the second most demanding operation, keys can be reused to sign multiple proposals, so this is expected to be the dominant operation.

- 3.

Signature verification Measuring time to verify a signature. Frequency will match signing, with FROST and BLS having different verification processes and resource demands.

- 4.

End-to-end operation Complete protocol timing for all phases, providing a comprehensive metric for comparison.

4.3. Network Simulations

To capture the effect of communication overheads, benchmarks incorporating simulated network conditions were developed. Artificial delays were introduced to emulate message latency, and randomised message drops were used to represent packet loss. The implementation of this simulation was language-specific: in Rust, delays and drops were introduced directly at the benchmark harness level; in C++ and Go, equivalent logic was implemented using the respective concurrency and timing libraries. This ensured consistency in the simulated conditions across all tested libraries, while allowing each benchmark to be executed natively within its language environment. The network scenarios vary the latency and packet loss with a normal distribution as shown in

Table 2.

4.4. Trusted Dealer

For comparison against decentralised Distributed Key Generation (DKG), benchmarks were also conducted using a trusted dealer (TD) model. In these tests, a single client acted as the dealer, distributing secret key shares to each participant. This simplified protocol incurs only one round of communication latency and packet loss (dealer-to-participant), avoiding the multiple broadcast and verification stages of DKG. Including TD benchmarks provides an equivalent reference point for computation and communication costs, allowing the overhead of decentralisation to be quantified.

4.4.1. Benchmark Environment

Microsoft Visual Studio Code with integrated GitHub AI Copilot was used for code development. This allowed rapid prototyping of

11 benchmarks in three different programming languages. The code provided a test harness to manage the input/output of variables into the FROST/BLS library functions, group participant data and orchestrate the signing operations and generate statistical data. A working benchmark was created for the first library and it was then used as a template for subsequent prompts, all code and prompts are published on GitHub [

51].

When developing and testing the code, care was taken to ensure consistent performance measurements were being taken, with the Coefficient of Variation data used to measure stability of the benchmarking process. Time measurements for individual phases of the signing process were recorded in order to allow identification of bottlenecks in the signing process, which may be incompatible with the real-world concept of employment for the UAS network. To ensure similar levels of precision timing, Criterion (Rust), Google Benchmark (C++) and testing.B (Go) frameworks were used to manage iteration/sample sizes, timing and collation of results for each operation. The exception to this was the netsim benchmarks, where these formal benchmarking frameworks proved too time-consuming (in excess of 24hrs) for the largest groups/worst network conditions. As an alternative, a fixed number of 10-20 iterations was performed for each data point. This pragmatic trade-off allowed for the collection of essential performance data in realistic scenarios, while acknowledging a reduced level of statistical precision compared to the static benchmarks.

A language-appropriate method of passing messages between the simulated group participants was used (Channels, Maps and Arrays). For the static benchmarks, this did not attempt to introduce variations in network performance as a variable, but provided a method for simulated clients to pass messages in an ordered manner. Supporting DKG for both protocols and signing for the FROST benchmarks (with BLS only having a single signing round, this was not required). Network performance was isolated and tested separately.

5. Results and Discussion

This project aimed to comprehensively assess the performance of MLS and Threshold Signature libraries and, in doing so, identify suitable implementations for use within a decentralised network of UAS.

Table 3 summarises the benchmarks that were completed. Combined, these provide an extensive dataset from which to produce insights on the performance impacts of cryptographic curve, protocol and language implementation.

5.1. MLS Results

The benchmark results showed a clear performance advantage for the OpenMLS library compared to the MLSpp library. Full results, for all the cipher suites tested can be found in Appendix A. The following sections will consider the performance of each library in turn, highlighting key results and providing supporting data and analysis of their implications.

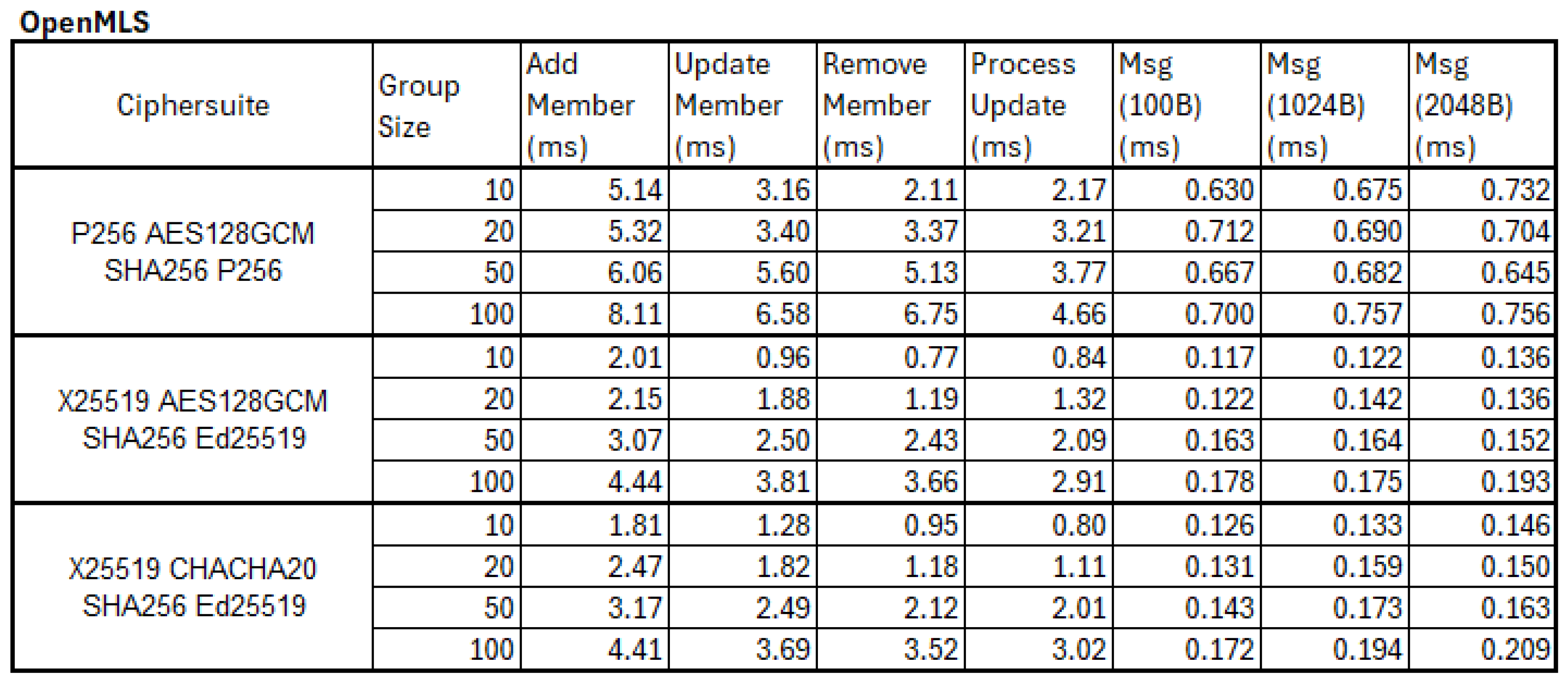

5.2. OpenMLS Results

5.2.1. Full MLS Mode Benchmark

OpenMLS showed consistently high levels of performance across all cipher suites. Increasing client number from 10 to 100 had a relatively small impact on performance, with the Add Member operations increasing by a factor of 1.5x to 2.4x as the group size increased from 10 to 100. Send Message performance showed no measurable difference as group size increased and only a slight increase as message size increased.

Figure 9.

OpenMLS Full Results

Figure 9.

OpenMLS Full Results

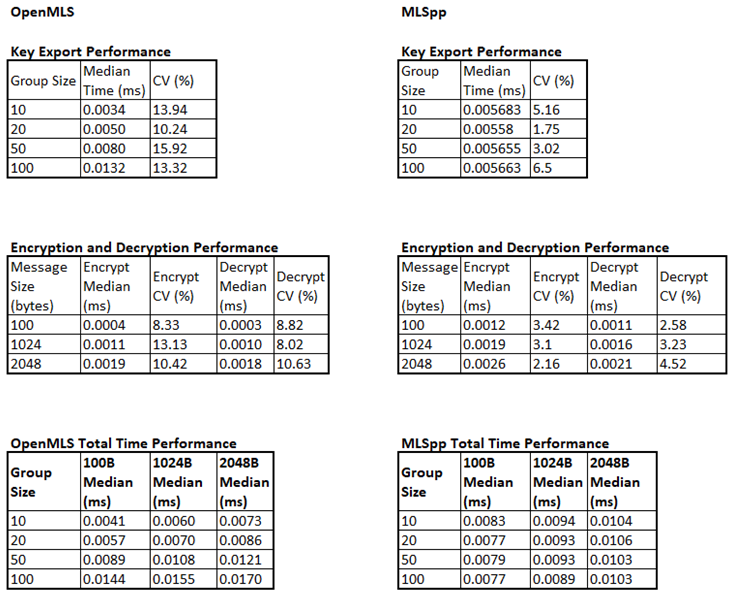

5.2.2. MLS Key Management Mode Benchmark

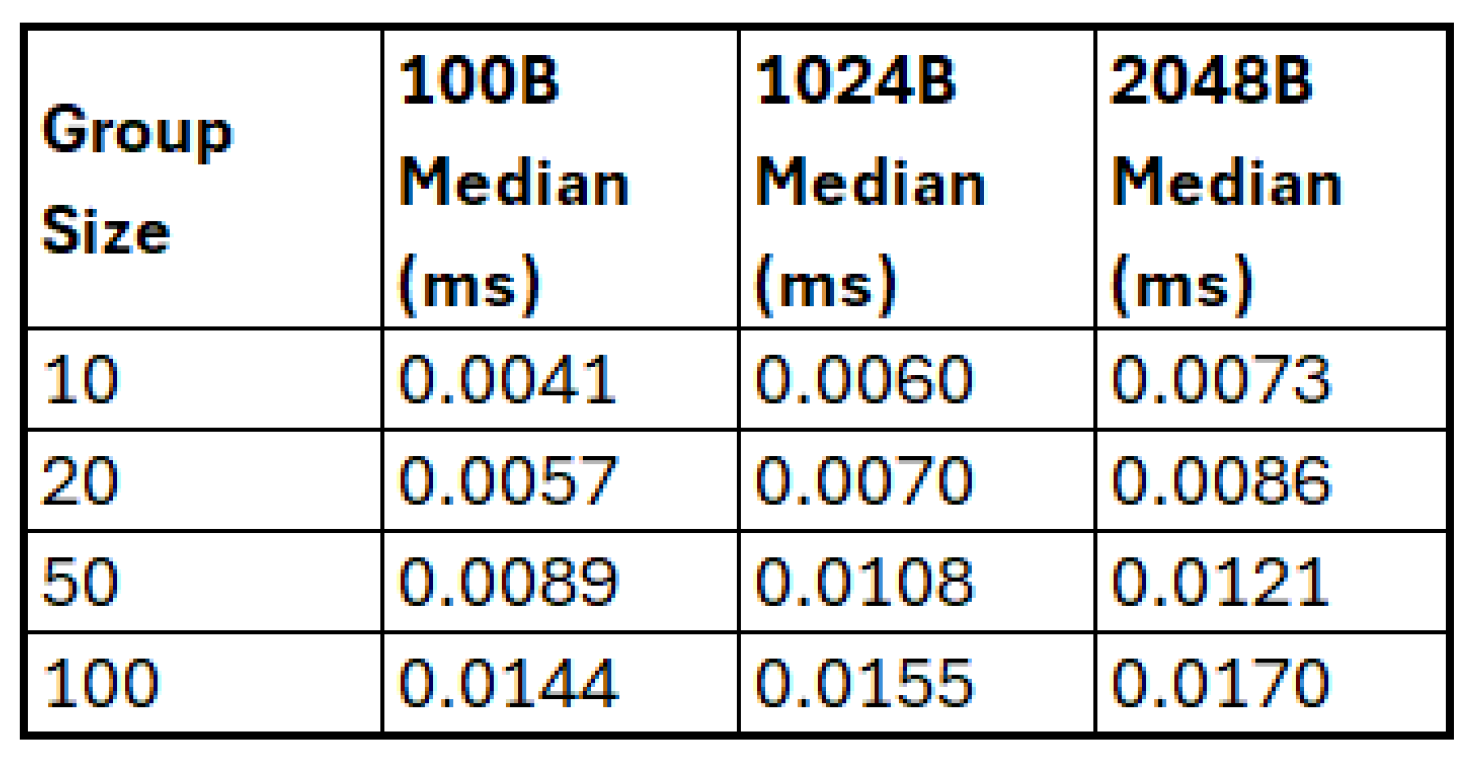

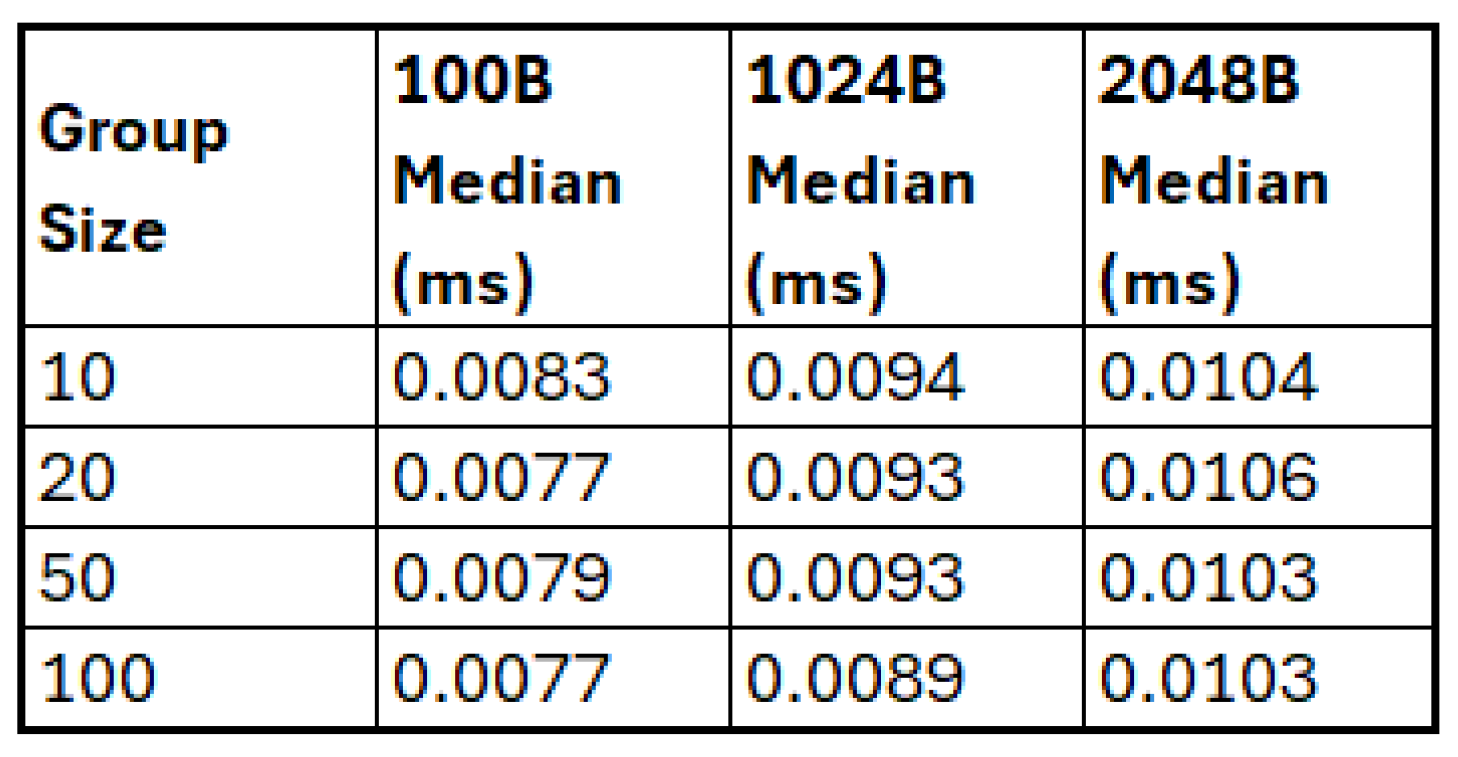

The combined results for a single Key Export, Encrypt, Decrypt cycle, using the X25519 AES 128 SHA256 Ed25519 cipher suite (also used for equivalent MLSpp benchmark) are shown in

Figure 10. This shows performance reducing as both message size and group size increase. Key export times dominate these results, for 100 client groups a performance reduction between 2.3x and 3.5x was observed relative to the 10 client group. A smaller reduction in performance was seen as message size increased from 100B to 2048B, between 1.2x and 1.8x.

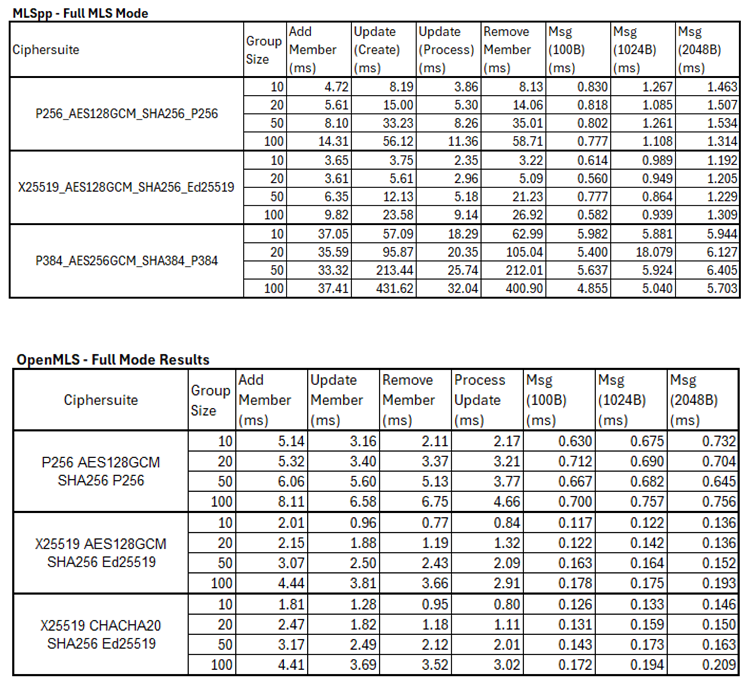

5.3. MLSpp Results

5.3.1. Full MLS Mode Benchmark Results

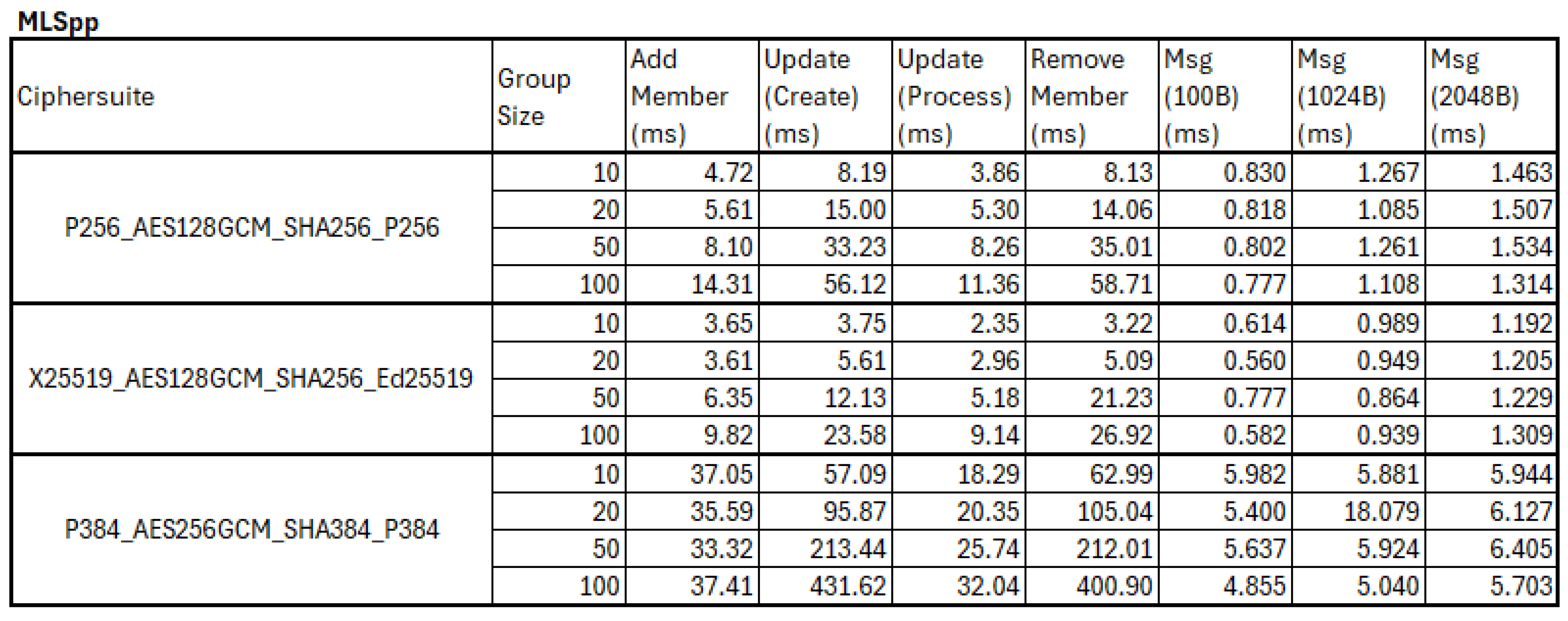

MLSpp showed lower levels of performance, with far more variation across all operations.

Add Member operations scaled from 1 to 3x as group sized increased from 10 to 100.

Update Member/Remove Member/Process Update showed even larger increases, up to 8.3x in the worst case (X25519 -

Remove Member -10 to 100 clients). This is a particularly significant finding, as it shows that a core group management function scales linearly, failing to achieve the theoretical logarithmic scaling of the MLS protocol. Send message performance remained consistent as group size increased, but showed an average increase of 1.6x as message size increased from 100B to 2048B (and 2.2x in the worst case.). These results are shown in

Figure 11

5.3.2. Key Management Mode Benchmark Results

In this mode, MLSpp showed far less variation across all operations and end-to-end performance. The key export performance showed no measurable difference as the group size increased. Encryption and decryption performance showed a 2.1x and 1.9x increase in time as message size increased from 100B to 2048B. Again key export times dominated the end to end results. With OpenMLS performing twice as well as MLSpp for the 100B message across a 10 person group, and the results reversed for the largest group size, where a 1.65x advantage was observed for MLSpp.

Figure 12 shows the end to end results for MLSpp.

5.3.3. Open MLS vs MLSpp

OpenMLS comprehensively outperforms MLSpp for all aspects of the MLS Full Mode benchmark.

Figure 13 visualises this result. It is noteworthy that MLSpp’s update and remove member performance scale so poorly. While these operations involve modifying data stored within the secret tree, they are less cryptographically demanding than the add member operation. This suggests that the library is less well optimised for this data management task, particularly for larger group sizes. In comparison, OpenMLS achieved close to the theoretical O(log n) performance limit for all operations. This result corroborates the findings of Marstrander [

41], that MLSpp suffered data marshalling issues and was a sub-optimal choice for this type of application.

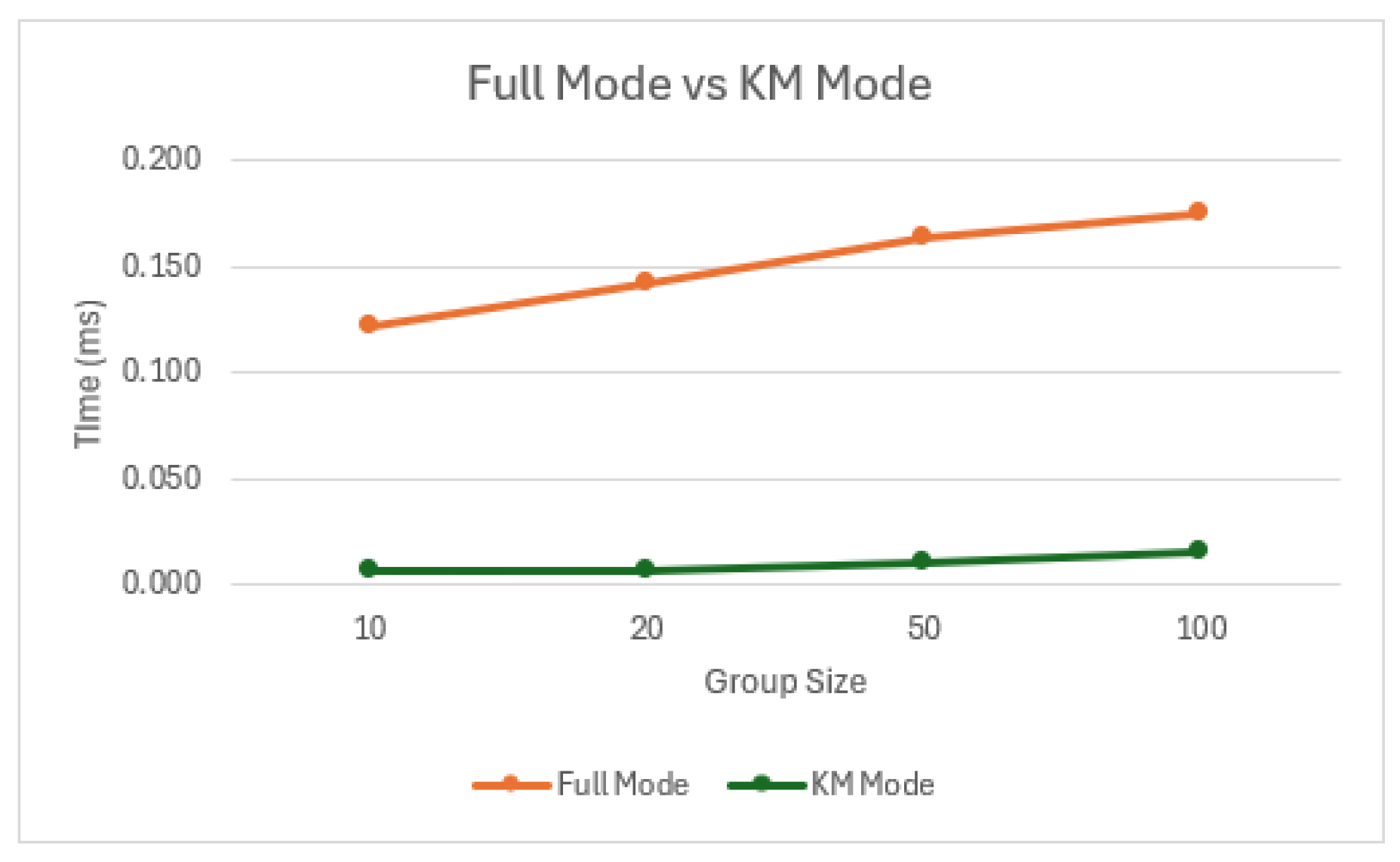

5.3.4. Full vs Key Management Mode

The key export function allows the production of a symmetric session key that can be used by a separate application for encryption. This results in far higher throughput rates than using the

Message Protect and

Message Unprotect operations in ’Full MLS Mode’. Messages are no longer signed, so there is a reduction in assurance, there is also a corresponding reduction in demand on the system. So it is unsurprising that performance is significantly greater in Key Management mode, this difference is shown in

Figure 14, where the time taken for OpenMLS to complete one encryption cycle is 20x greater for a 1024B message and a group size of 10. Both libraries showed similar stand alone encryption/decryption performance (within one microsecond of each other), although MLSpp showed a 7.5 microsecond advantage over OpenMLS when exporting a key. However, this small advantage becomes irrelevant if a key is used more than eight times (in the worse case scenario) due to OpenMLS’ superior encryption/decryption performance.

There are benefits beyond just increased throughput. Messages sent using the Message Protect and Message Unprotect operation are dependent on the Delivery Service (DS) to correctly order messages as they are distributed to the group, if the DS is temporarily unavailable messages cannot be sent. The DS also has to be available for handshake messages to be sent, however the frequency with which these occur is controlled by the system integrating MLS and a DS outage is tolerable. The existing key will still work and when the DS is restored, the system will rekey, with any compromises that have occurred being healed. The practical limit of this tolerance would be an appropriate area for further study. A second additional benefit is that removing encryption/decryption duties reduces the processing load on the system. For UAS systems with limited processing and battery power, this is an important consideration. No attempt was made to resource constrain these benchmarks to model representative hardware, but it is likely that MLS as a Key Management plane has greater utility on these kinds of systems and this should also be a focus of further study.

The trade-off for increased performance in this case is a loss of assurance from the application of digital signatures to every message. It can be argued that this is useful in a messaging application (Wickr/Signal), where attribution of who sent a message is vital to the integrity of the group conversation. However that has less utility in a machine to machine exchange where 1000’s of messages are being sent and the cost overhead quickly becomes unsustainable. The use of MLS in this way is recognised in the RFC and is not a subversion of the protocol.

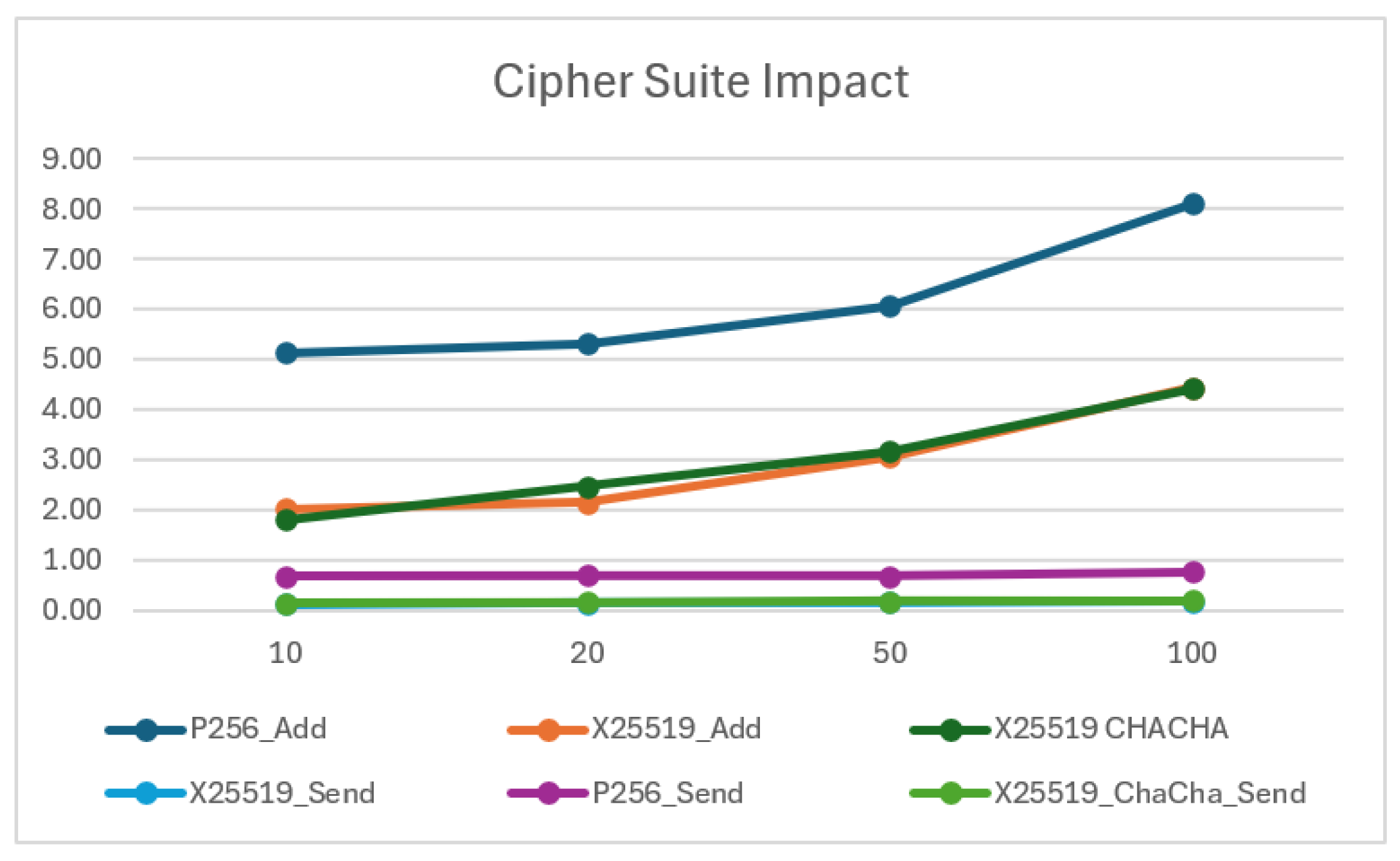

5.3.5. Impact of Cipher Suite

While library selection has a much greater impact on performance, the choice of cipher suite also has an effect. In

Figure 15, the top 3 graphs show that the time taken to complete an

Add Member increased with group size. The slowest suite (top line) utilised the NIST P256 signature algorithm, which is used multiple times during this operation, with a similar impact on the send message performance. In comparison, the two curves that utilise the faster Ed25519 signature scheme have near identical performance, despite their use of different symmetric encryption keys. Previous work [

39,

41] utilised the suites containing P256 due to that algorithm being certified by NIST for use with Government contracts. This is an understandable approach, and customer requirements may dictate future specifications. However, the forecast arrival of quantum computers will undermine these classical algorithms security. Neither library fully supports a post-quantum secure cipher suite but integration of ML-KEM into OpenMLS is imminent [

52]. However, no digital signature solution is yet available. In the meantime, focussing customer requirements on selecting enduring key exchange and encryption algorithms in order to maintain confidentiality is likely to be a higher priority than the use of a NIST approved digital signature. The likely increase in size and processing requirements for PQC secure signatures, will further reduce the performance of the ’Full MLS Mode’ within our use case and strengthens the argument in for adopting it as a Key Management plane.

5.3.6. MLS Results Conclusion

The chosen metrics and specific MLS operations benchmarked provided sufficient insight into the protocols operation and the libraries performance for an in depth assessment of their suitability to be made. With OpenMLS shown to be the highest performing library across all benchmarks and the performance issues identified with MLSpp corroborated by our test. The use of MLS in Key Management mode was shown to be significantly higher performing at encryption/decryption than in full mode, and this mode is likely to have benefits for low power/compute networks like our UAS concept beyond just speed, although these remain unproven and would be a key test for future extensions of this work.

While the primary MLS group managmenet operations were tested, the group setup phase was not. Having been deliberately excluded from the benchmark, following the OpenMLS example benchmark. This configures the group states as a separate operation outside of the benchmarking process. It would also be completed during the configuration phase within our proposed concept of operation, so timeliness is important but not critical. However, its inclusion within the benchmark would have further informed the development of that concept and is a small missed opportunity.

5.4. Threshold Signature Benchmarks

Full, raw results for each of the benchmarks discussed can be found in Appendix B. More focussed snapshots are provided within this chapter where it is appropriate.

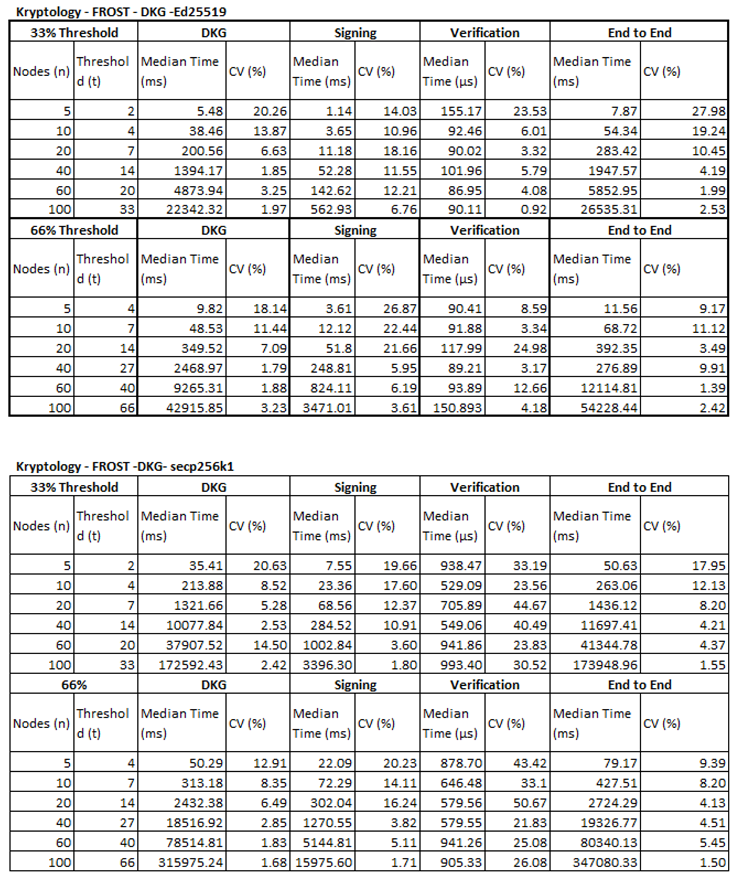

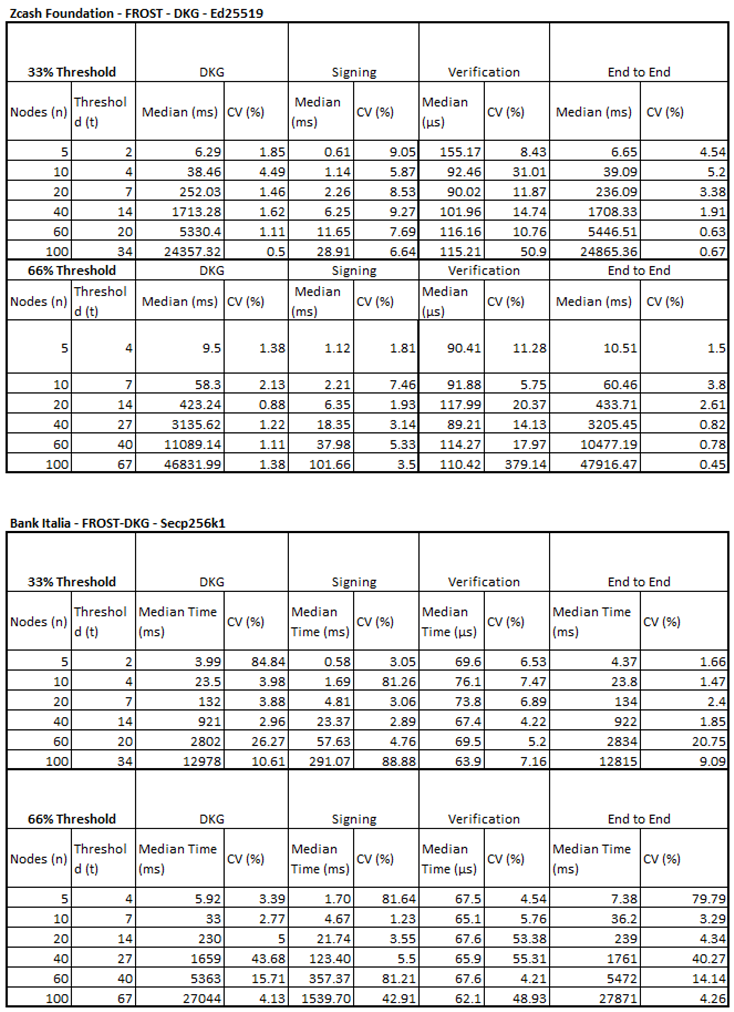

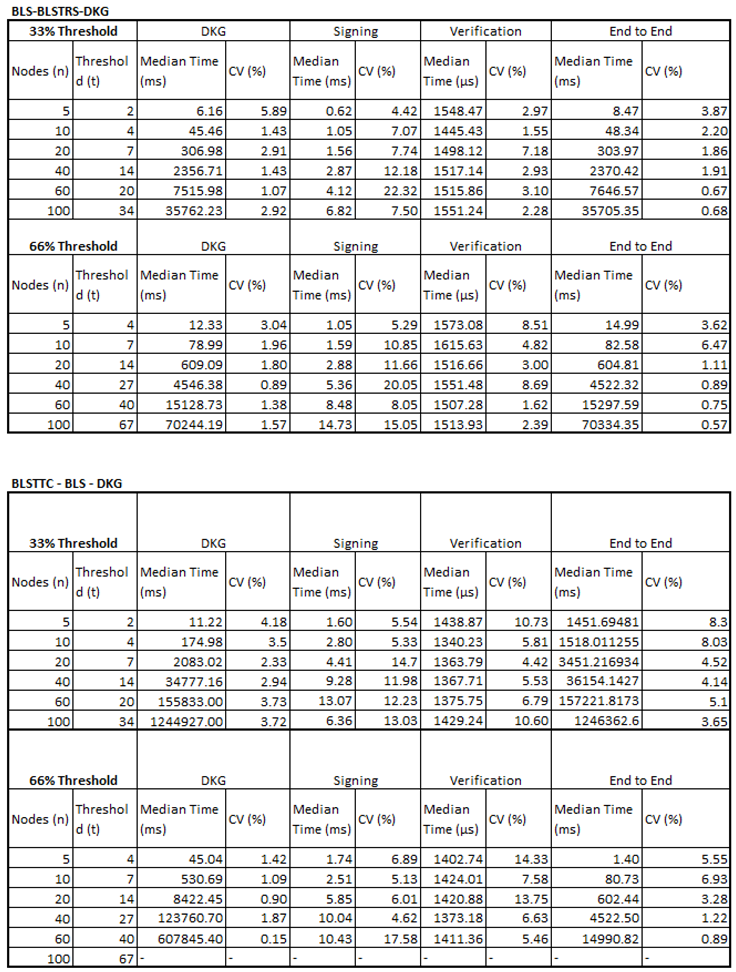

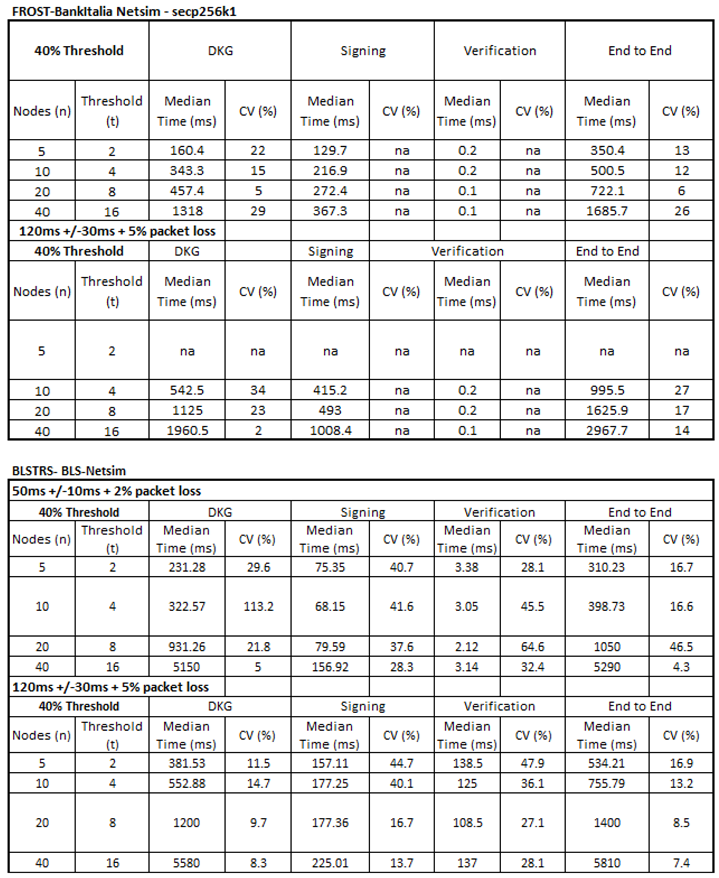

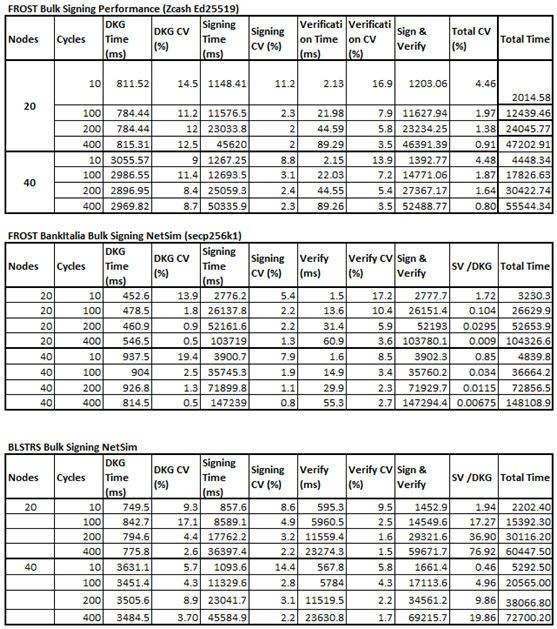

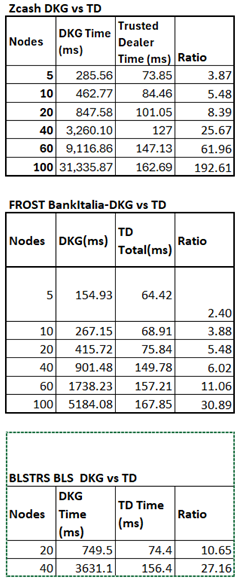

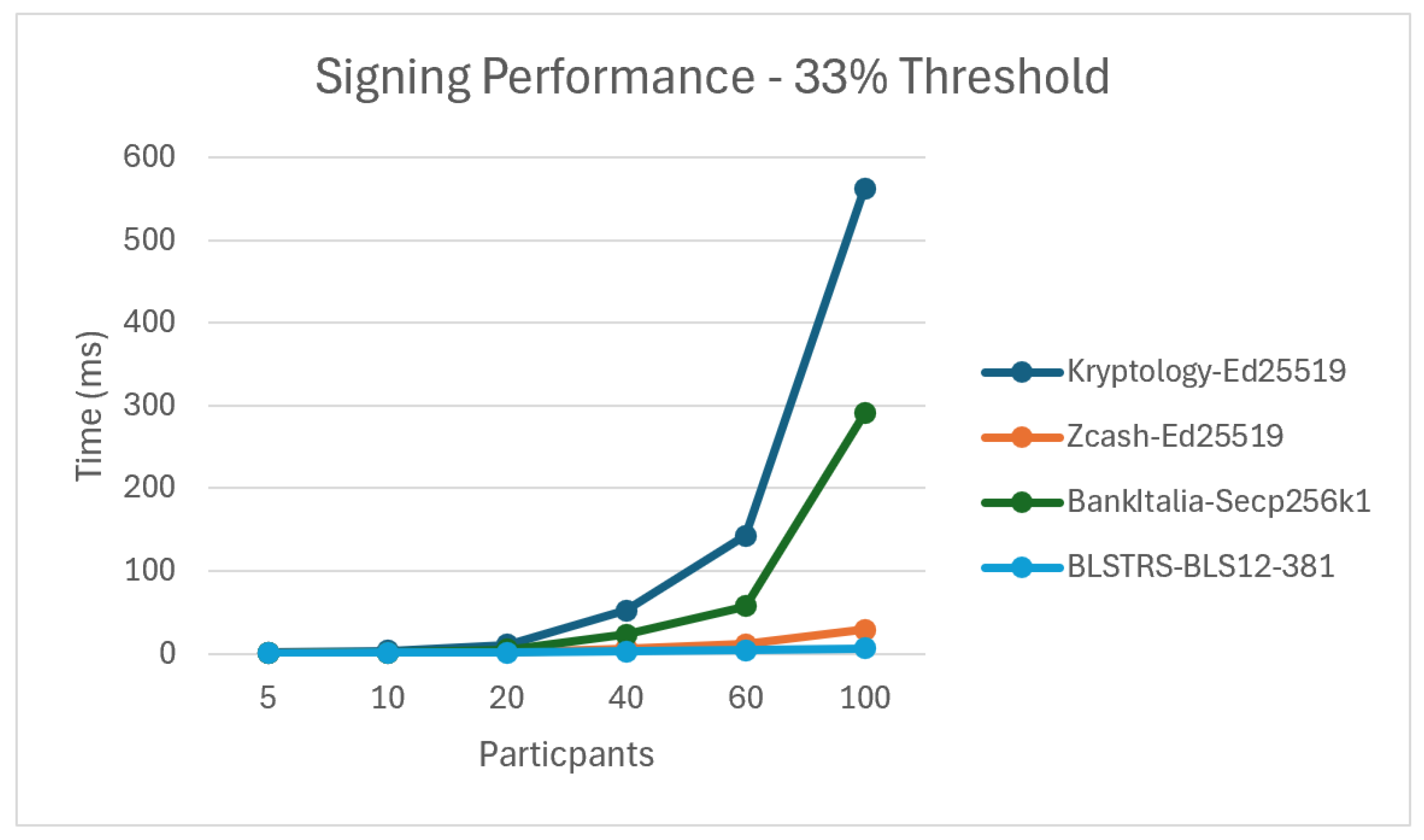

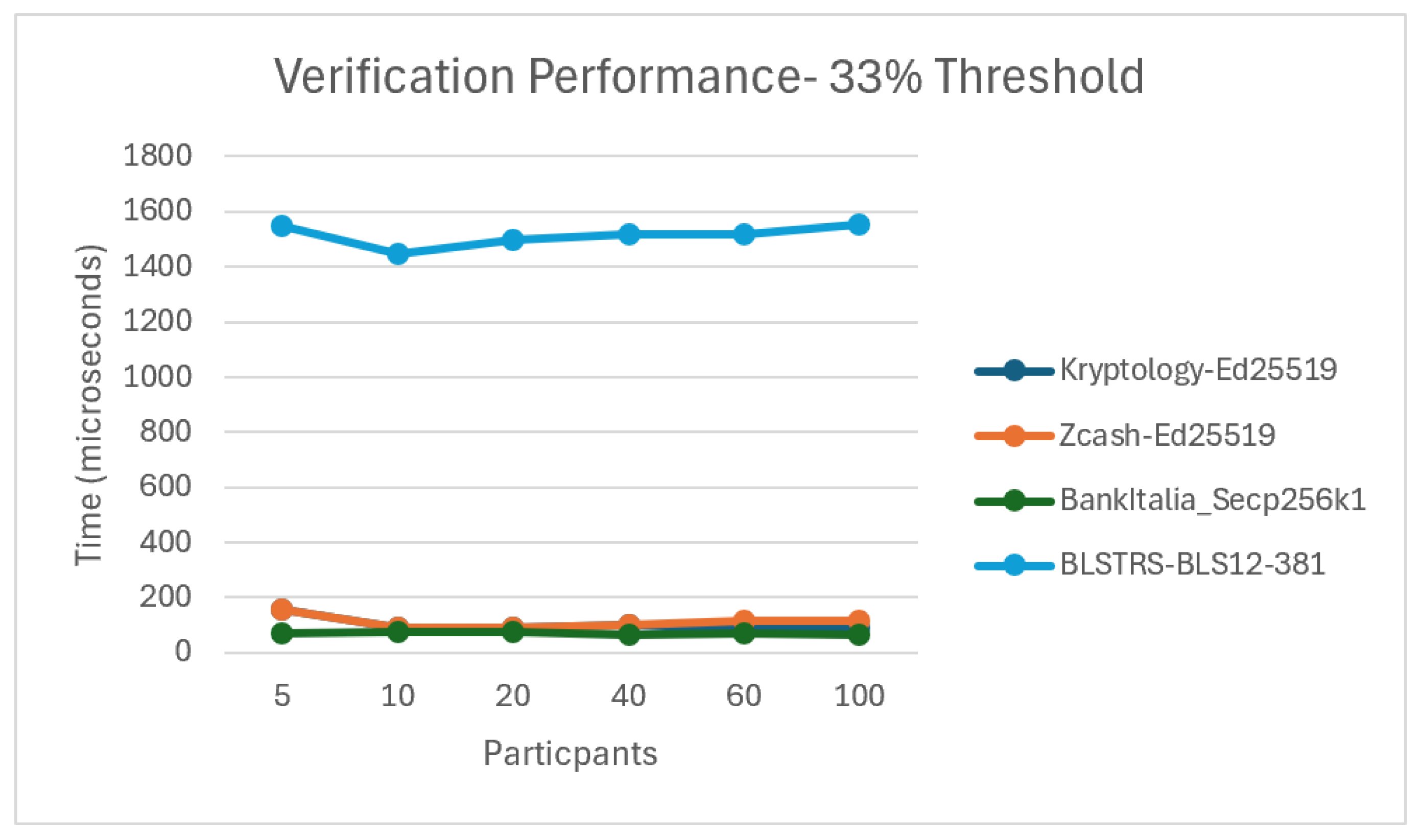

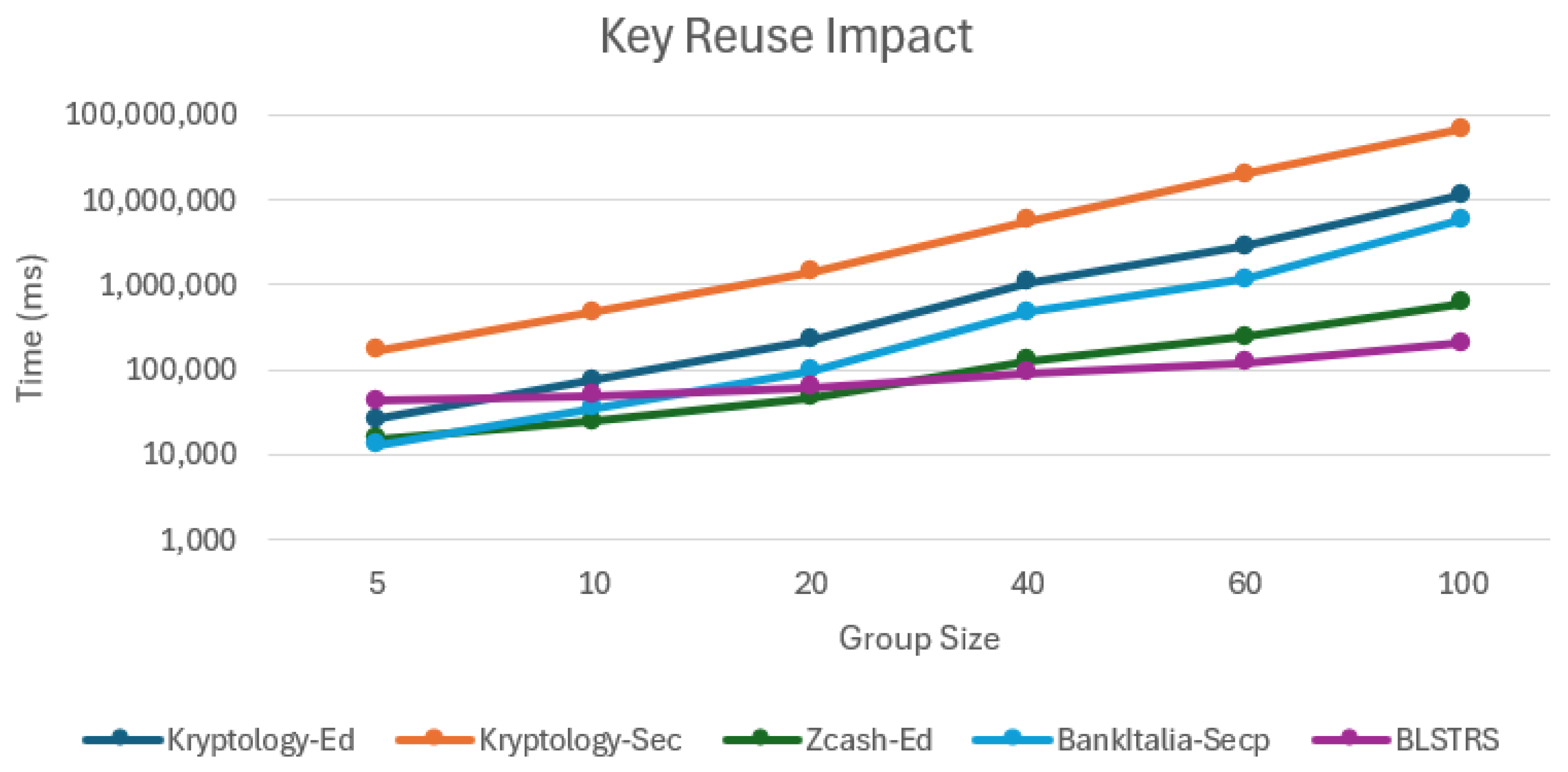

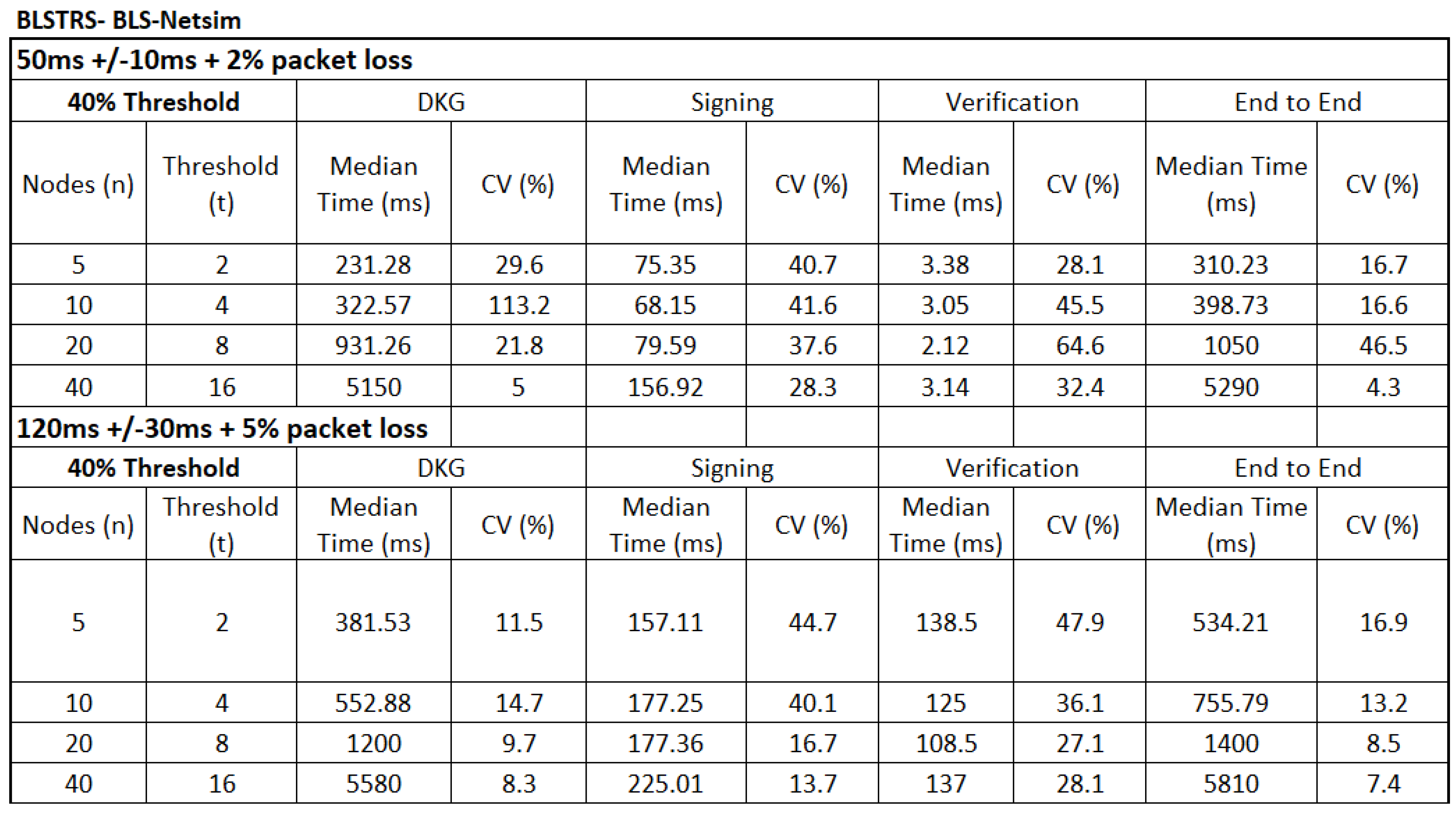

5.4.1. Static Results