Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

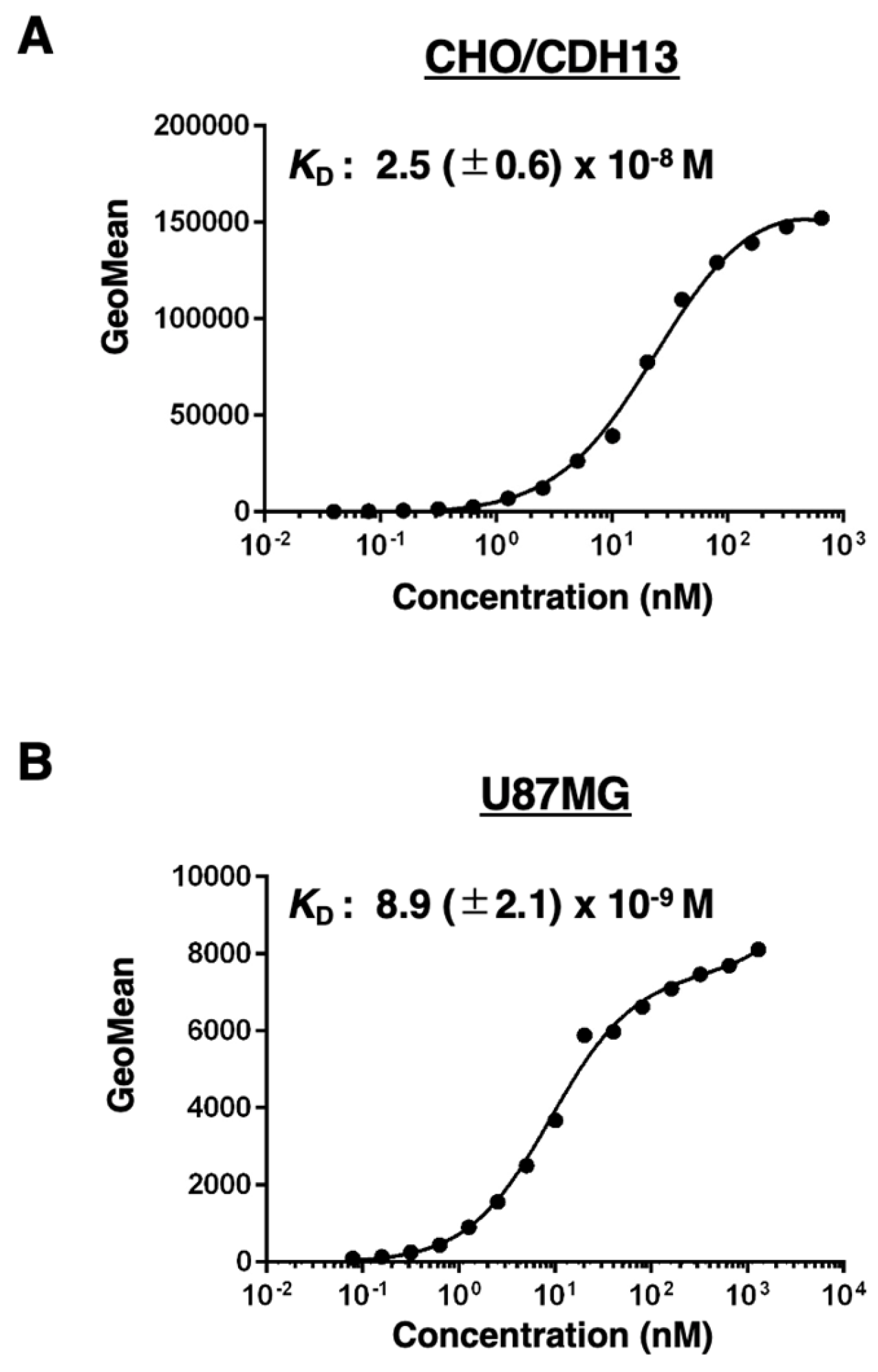

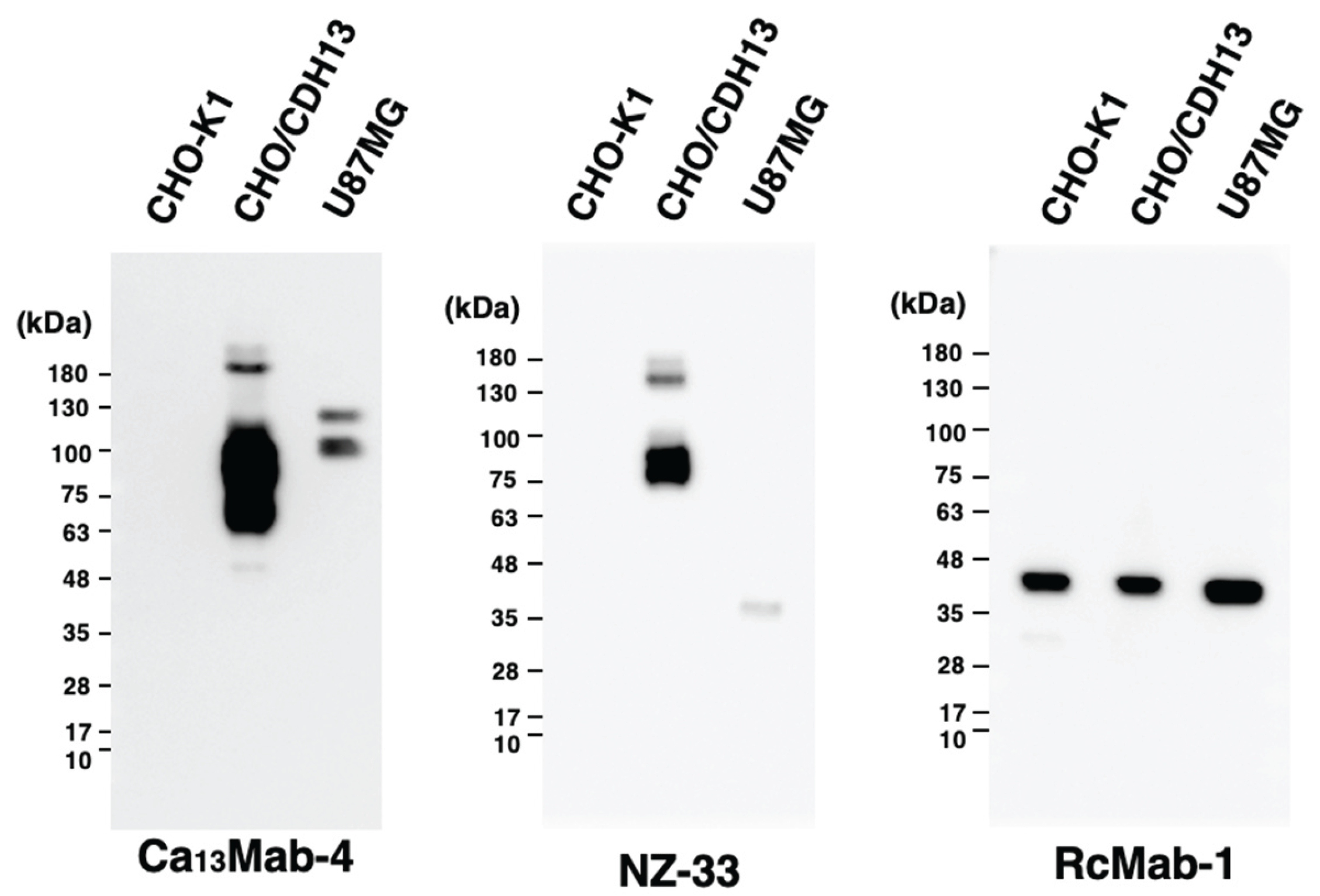

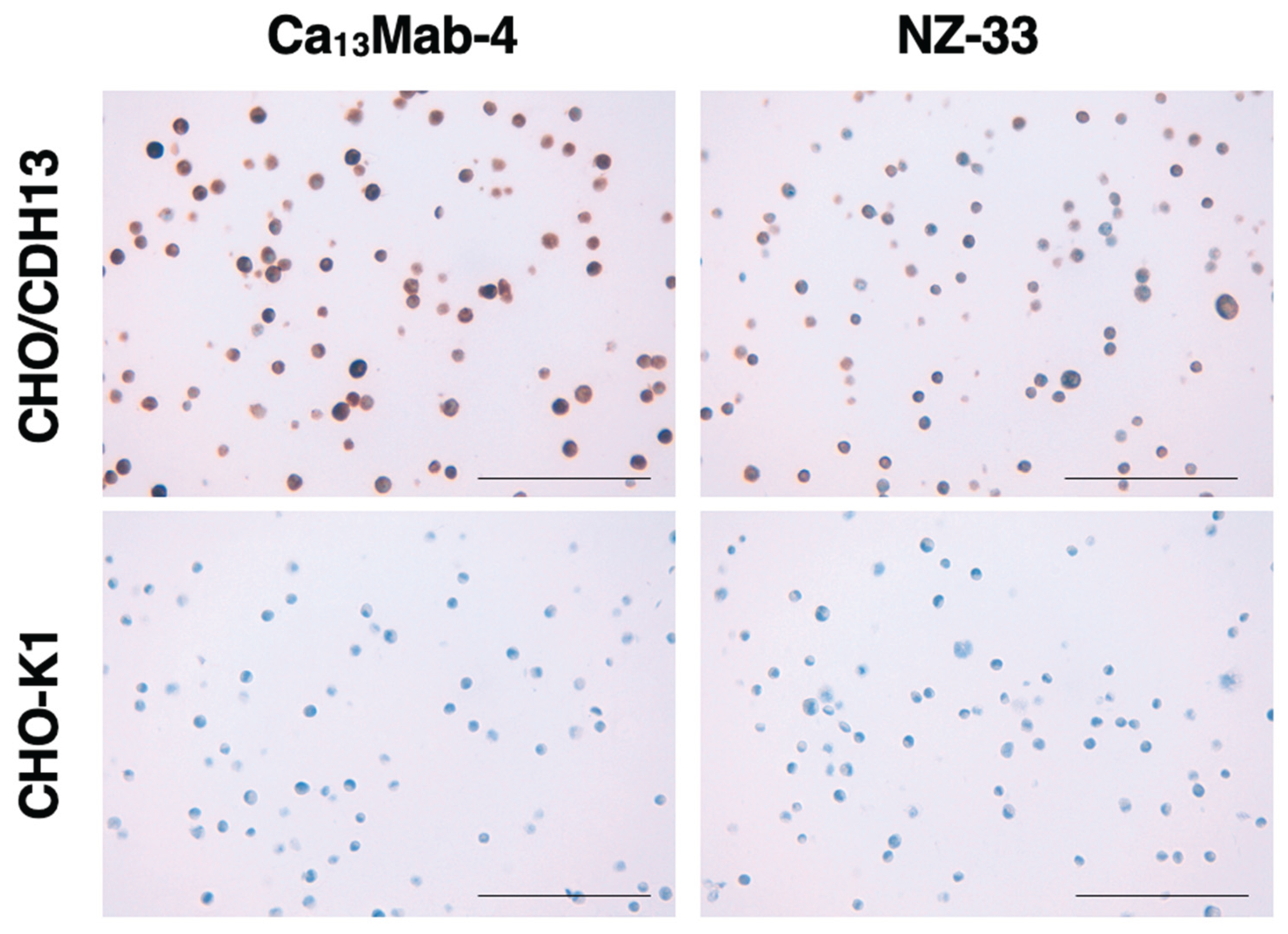

Cadherin 13 (CDH13), also known as T-cadherin or H-cadherin, is a member of the cadherin superfamily. CDH13 is anchored to the plasma membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol. CDH13 plays an essential role in the development of the heart and nervous systems, including the brain. Many reports have identified CDH13 as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders. Furthermore, CDH13 has been shown to be expressed in numerous cancers, but its role as a cancer-promoting or -suppressing factor remains unclear. Therefore, the development of highly sensitive and specific anti-CDH13 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is necessary to elucidate the biological and pathological functions of CDH13. In this study, we established a novel anti-human CDH13 mAb (clone Ca13Mab-4) using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method. Ca13Mab-4 can be used for flow cytometric analysis. Ca13Mab-4 binds specifically to CDH13 and not to other cadherin family members. The dissociation constant values of Ca13Mab-4 for CDH13-overexpressed CHO-K1 and U87MG glioma cells were determined as 2.5 (± 0.6) x 10-8 M and 8.9 (± 2.1) x 10-9 M, respectively. Furthermore, Ca13Mab-4 clearly detected CDH13 in the western blot and immunohistochemistry of cell sections. Therefore, the Ca13Mab-4, established by CBIS method, could be a valuable tool for basic research and is expected to contribute to elucidating the relationship between CDH13 and diseases, including neurodevelopmental disorders and cancer.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Establishment of Stable Transfectants

2.3. Antibodies

2.4. Development of Hybridomas

2.5. Flow Cytometry

2.6. Determination of Dissociation Constant Values Using Flow Cytometry

2.7. Western Blotting

2.8. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Using Cell Blocks

3. Results

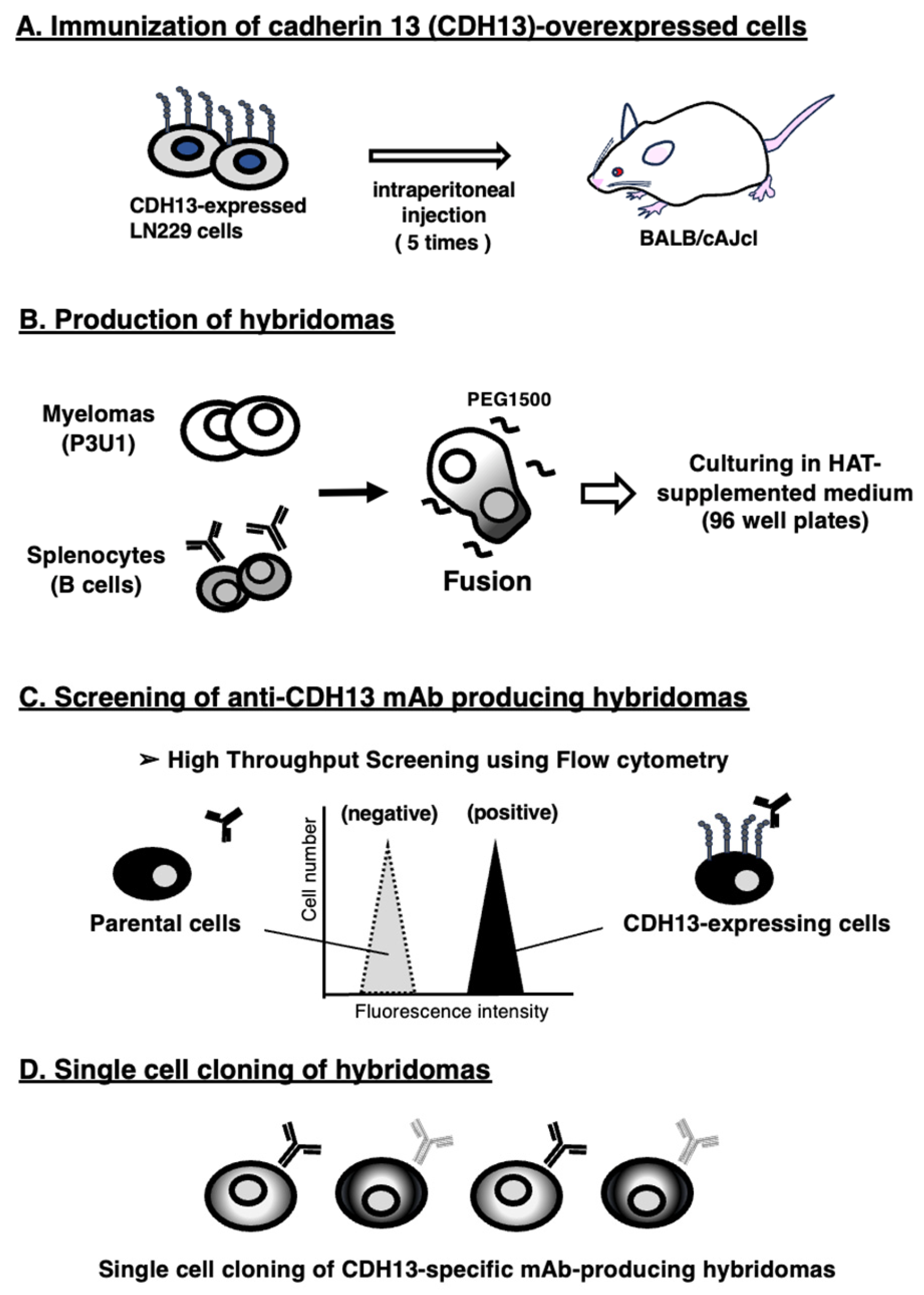

3.1. Development of Anti-CDH13 mAbs Using the CBIS Method

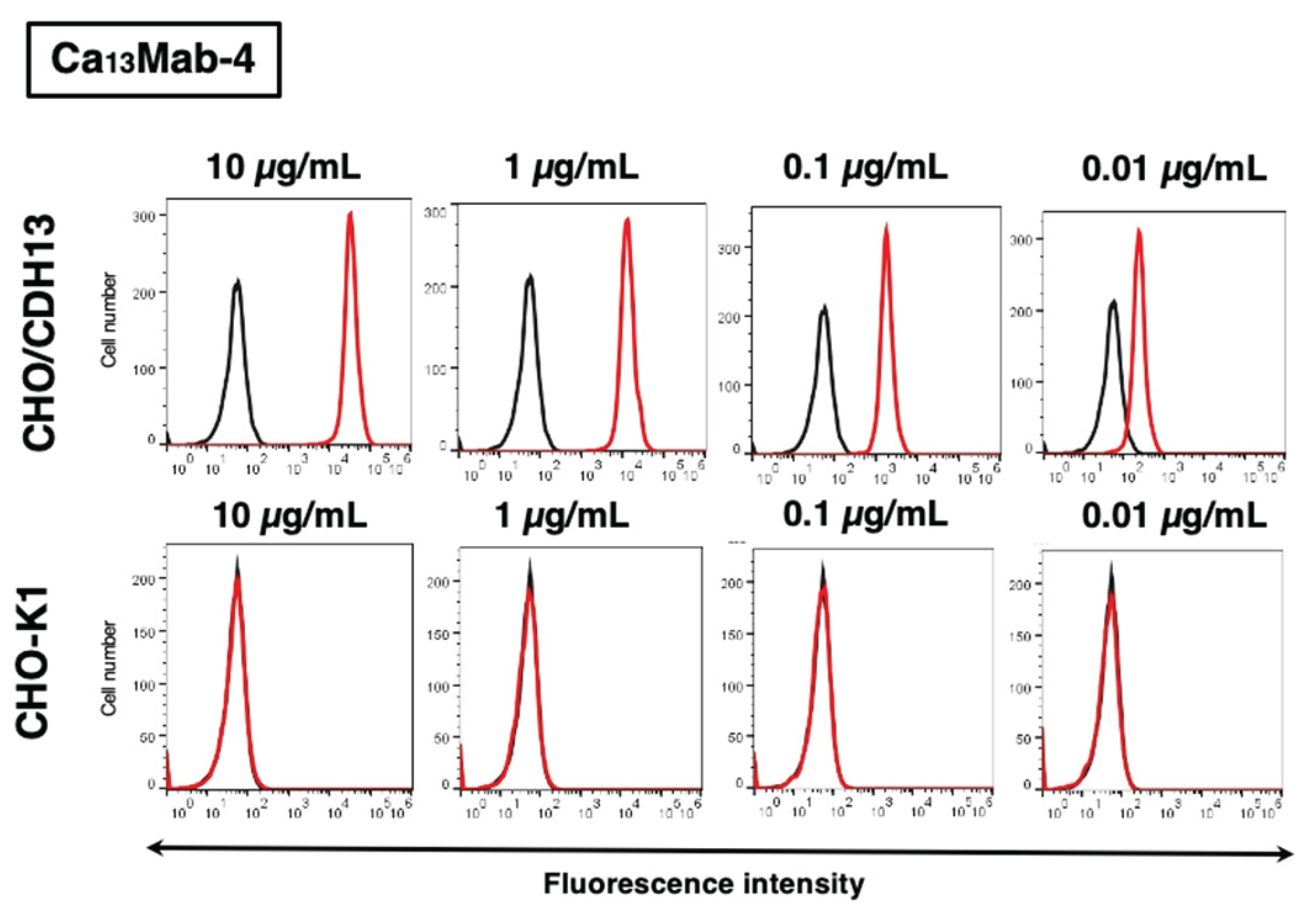

3.2. Evaluation of Ca13Mab-4 Reactivity Using Flow Cytometry

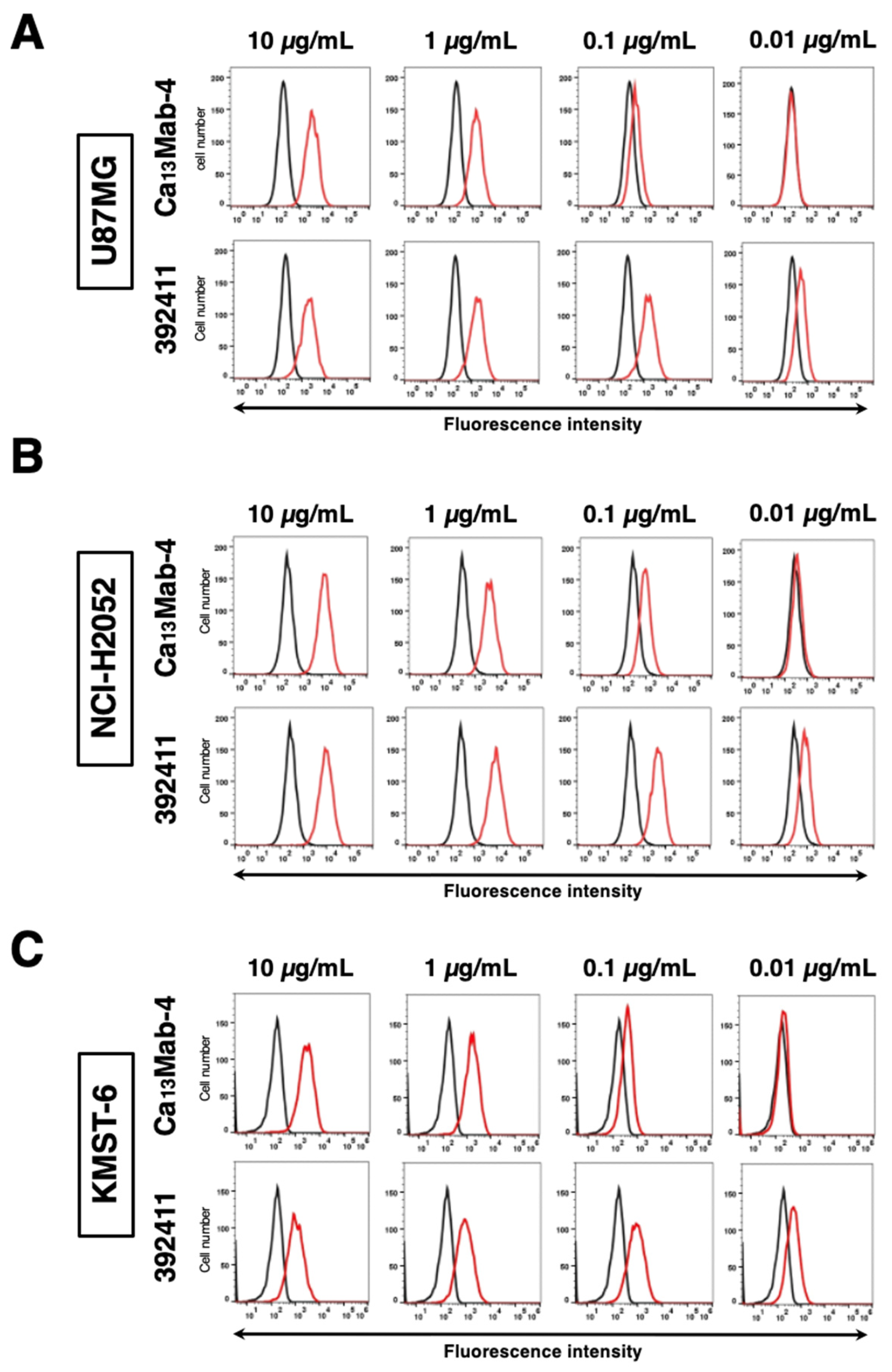

3.3. Evaluation of Anti-CDH13 mAbs Reactivity Against Endogenous CDH13 Using Flow Cytometry

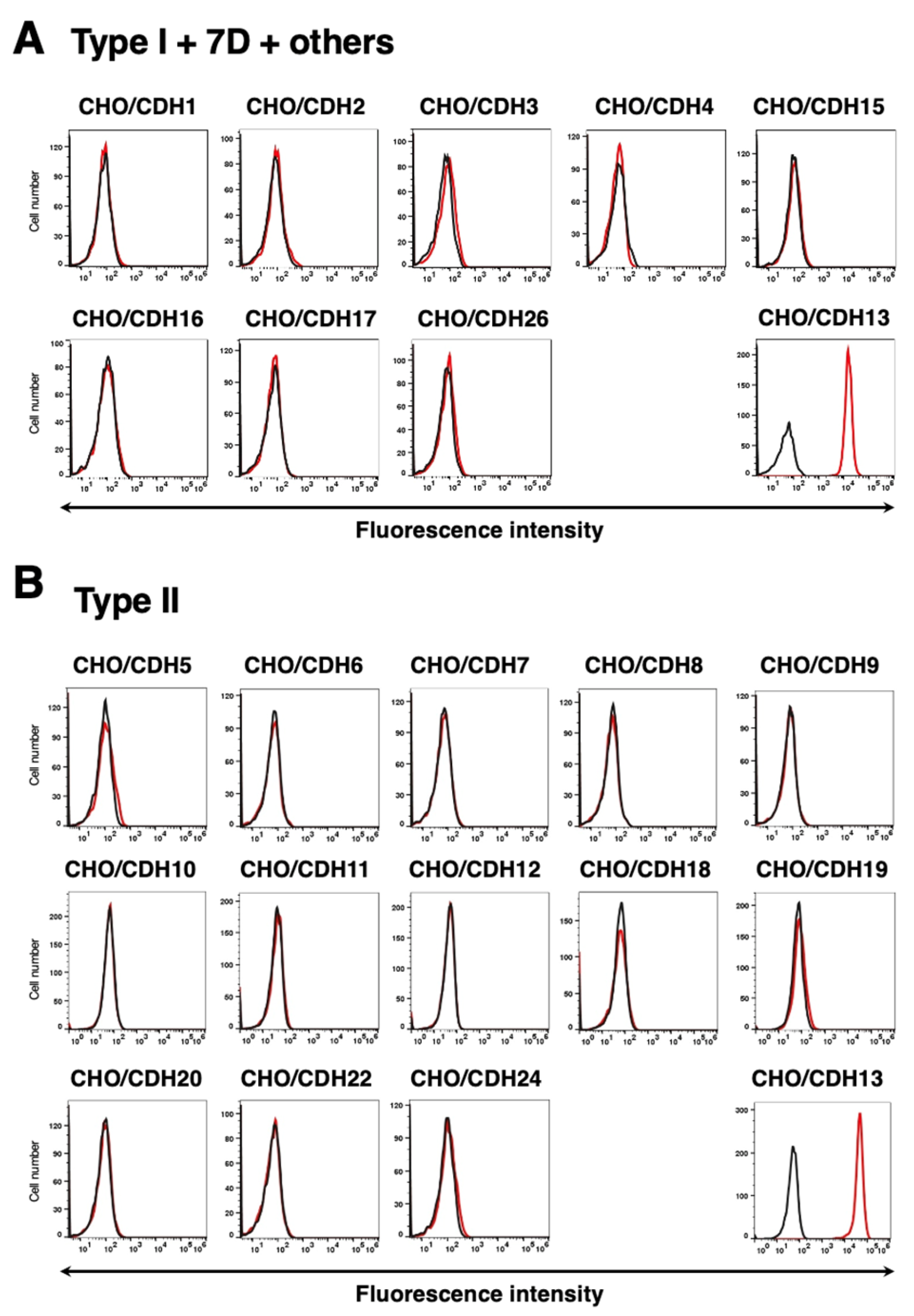

3.4. Specificity of Ca13Mab-4 to CDHs-Overexpressed CHO-K1 Cells

3.5. Calculation of the Apparent Binding Affinity of Ca13Mab-4 Using Flow Cytometry

3.6. Western Blot Analyses Using Ca13Mab-4

3.7. Immunohistochemistry Using Ca13Mab-4

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Credit authorship contribution statement

Funding Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yulis, M.; Kusters, D.H.M.; Nusrat, A. Cadherins: Cellular adhesive molecules serving as signalling mediators. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3883–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpiau, P.; van Roy, F. Molecular evolution of the cadherin superfamily. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roy, F. Beyond E-cadherin: Roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, M.; Harvey, T.S.; Bagby, S.; Tong, K.I.; Yau, P.; Takeichi, M.; Ikura, M. Solution structure of the epithelial cadherin domain responsible for selective cell adhesion. Science 1995, 267, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.; Fannon, A.M.; Kwong, P.D.; Thompson, A.; Lehmann, M.S.; Grübel, G.; Legrand, J.-F.; Als-Nielsen, J.; Colman, D.R.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structural basis of cell-cell adhesion by cadherins. Nature 1995, 374, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranscht, B.; Dours-Zimmermann, M.T. T-cadherin, a novel cadherin cell adhesion molecule in the nervous system lacks the conserved cytoplasmic region. Neuron 1991, 7, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Tao, L.; Ambrosio, A.; Yan, W.; Summer, R.; Lau, W.B.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X. T-cadherin deficiency increases vascular vulnerability in T2DM through impaired NO bioactivity. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Misaki, A.; Liang, S.-B.; Tachibana, A.; Hayashi, N.; Sonobe, H.; Ohtsuki, Y. Expression of T-Cadherin (CDH13, H-Cadherin) in Human Brain and Its Characteristics as a Negative Growth Regulator of Epidermal Growth Factor in Neuroblastoma Cells. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.G.; Scherer, P.E. Metabolic Messengers: Adiponectin. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemura, Y.; Ouchi, N.; Shibata, R.; Aprahamian, T.; Kirber, M.T.; Summer, R.S.; Kihara, S.; Walsh, K. Adiponectin modulates inflammatory reactions via calreticulin receptor-dependent clearance of early apoptotic bodies. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Kihara, S.; Arita, Y.; Maeda, K.; Kuriyama, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Hotta, K.; Nishida, M.; Takahashi, M.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation 1999, 100, 2473–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischon, T.; Girman, C.J.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Rifai, N.; Hu, F.B.; Rimm, E.B. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA 2004, 291, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Funahashi, T.; Arita, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Matsuda, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Iwahashi, H.; Kuriyama, H.; Ouchi, N.; Maeda, K.; et al. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S.; Kita, S.; Obata, Y.; Fujishima, Y.; Nagao, H.; Masuda, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Nishizawa, H.; Funahashi, T.; Takagi, J.; et al. The unique prodomain of T-cadherin plays a key role in adiponectin binding with the essential extracellular cadherin repeats 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 7840–7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, C.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, N.S.; Bogan, J.S.; Tsao, T.-S.; Lodish, H.F. T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10308–10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbard, L.W.; Garlatti, M.l.; Young, L.J.T.; Cardiff, R.D.; Oshima, R.G.; Ranscht, B. T-cadherin Supports Angiogenesis and Adiponectin Association with the Vasculature in a Mouse Mammary Tumor Model. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, S.; Fukuda, S.; Maeda, N.; Shimomura, I. Native adiponectin in serum binds to mammalian cells expressing T-cadherin, but not AdipoRs or calreticulin. eLife 2019, 8, e48675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, O.; Selten, M.M.; Sich, S.; Popp, S.; Bacmeister, L.; Amendola, E.; Negwer, M.; Schubert, D.; Proft, F.; Kiser, D.; et al. Cadherin-13, a risk gene for ADHD and comorbid disorders, impacts GABAergic function in hippocampus and cognition. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, S.J.; Ercan-Sencicek, A.G.; Hus, V.; Luo, R.; Murtha, M.T.; Moreno-De-Luca, D.; Chu, S.H.; Moreau, M.P.; Gupta, A.R.; Thomson, S.A.; et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron 2011, 70, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cohen-Woods, S.; Chen, Q.; Noor, A.; Knight, J.; Hosang, G.; Parikh, S.V.; De Luca, V.; Tozzi, F.; Muglia, P.; et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in Canadian and UK populations corroborates disease loci including SYNE1 and CSMD1. BMC Med. Genet. 2014, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, I.; Watanabe, Y.; Hishimoto, A.; Boku, S.; Mouri, K.; Shiroiwa, K.; Okazaki, S.; Nunokawa, A.; Shirakawa, O.; Someya, T.; et al. Association analysis of the Cadherin13 gene with schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Neuropsychiatry Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.C.; Aliev, F.; Bierut, L.J.; Bucholz, K.K.; Edenberg, H.; Hesselbrock, V.; Kramer, J.; Kuperman, S.; Nurnberger, J.I.J.; Schuckit, M.A.; et al. Genome-wide association study of comorbid depressive syndrome and alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Genet. 2012, 22, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Harrar, D.B.; Lin, Y.; Koon, A.C.; Hauser, J.L.; Griffith, E.C.; Zhu, L.; Brass, L.F.; Chen, C.; Greenberg, M.E. An RNAi-based approach identifies molecules required for glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse development. Neuron 2007, 53, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, A.; Rivero, O.; Wäldchen, S.; Ku, H.-P.; Kiser, D.P.; Gärtner, Y.; Pennington, L.S.; Waider, J.; Gaspar, P.; Jansch, C.; et al. Cadherin-13 Deficiency Increases Dorsal Raphe 5-HT Neuron Density and Prefrontal Cortex Innervation in the Mouse Brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciatto, C.; Bahna, F.; Zampieri, N.; VanSteenhouse, H.C.; Katsamba, P.S.; Ahlsen, G.; Harrison, O.J.; Brasch, J.; Jin, X.; Posy, S.; et al. T-cadherin structures reveal a novel adhesive binding mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayano, Y.; Zhao, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Takeuchi, K.; Norioka, S.; Yamamoto, N. The role of T-cadherin in axonal pathway formation in neocortical circuits. Development 2014, 141, 4784–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodbury-Smith, M.; Lamoureux, S.; Begum, G.; Nassir, N.; Akter, H.; O’rielly, D.D.; Rahman, P.; Wintle, R.F.; Scherer, S.W.; Uddin, M. Mutational Landscape of Autism Spectrum Disorder Brain Tissue. Genes 2022, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Li, P.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Bischof, E.; Han, J. Exon 1 methylation status of CDH13 is associated with decreased overall survival and distant metastasis in patients with postoperative colorectal cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Wang, J. CDH13 promoter methylation regulates cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 5715–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Huang, T.; Ren, Y.; Wei, J.; Lou, Z.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, Y.; Weng, G.; Yao, X. Clinical significance of CDH13 promoter methylation as a biomarker for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2016, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmelarova, M.; Baranova, I.; Ruszova, E.; Laco, J.; Hrochova, K.; Dvorakova, E.; Palicka, V. Importance of Cadherins Methylation in Ovarian Cancer: A Next Generation Sequencing Approach. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019, 25, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.; Setien, F.; Voelter, C.; Casado, S.; Quesada, M.P.; Schackert, G.; Esteller, M. CpG island promoter hypermethylation of the pro-apoptotic gene caspase-8 is a common hallmark of relapsed glioblastoma multiforme. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1264–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Song, X.; Zhang, L.; He, Q.; Ye, B.; Wu, L.; Wu, R.; et al. Aberrant promoter methylation of T-cadherin in sera is associated with a poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasma 2021, 68, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, L.; He, Q.; Ye, B.; Wu, L.; Huang, X.; et al. High PD-L1 expression associates with low T-cadherin expression and poor prognosis in human papillomavirus-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head. Neck 2023, 45, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbard, L.W.; Garlatti, M.; Young, L.J.; Cardiff, R.D.; Oshima, R.G.; Ranscht, B. T-cadherin supports angiogenesis and adiponectin association with the vasculature in a mouse mammary tumor model. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situ, Y.; Deng, L.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Liang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Shao, Z.; et al. CDH2 and CDH13 as potential prognostic and therapeutic targets for adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2428469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, D.; Philippova, M.; Kyriakakis, E.; Maslova, K.; Rupp, K.; A Buechner, S.; Iezzi, G.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Erne, P.; Resink, T.J. Paradoxical effects of T-cadherin on squamous cell carcinoma: Up- and down-regulation increase xenograft growth by distinct mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2011, 225, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Fujisawa, S.; Li, G.; Satofuka, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Development of a novel anti-human glypican 5 monoclonal antibody (G5Mab-1) for multiple applications. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 43, 102140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Sakata, T.; Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Kaneko, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a novel anti-mouse CD73 monoclonal antibody C73Mab-9 by the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening method. MI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Taruta, H.; Saga, A.; Li, G.; Fujisawa, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-human EphA1 Monoclonal Antibody, Ea(1)Mab-30, for Multiple Applications. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2025, 44, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Hosono, H.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of Anti-Mouse CC Chemokine Receptor 8 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2021, 40, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2016, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a monoclonal antibody PMab-233 for immunohistochemical analysis against Tasmanian devil podoplanin. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019, 18, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of Anti-Human Cadherin-26 Monoclonal Antibody, Ca26Mab-6, for Flow Cytometry. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Development and characterization of Ea7Mab-10: A novel monoclonal antibody targeting ephrin type-A receptor 7. MI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; Kato, Y.; Ishizawa, K.; Hirose, T.; Yokoo, H. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpiau, P.; Gul, I.S.; van Roy, F. New insights into the evolution of metazoan cadherins and catenins. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 116, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rubina, К.А.; Smutova, V.А.; Semenova, М.L.; Poliakov, А.А.; Gerety, S.; Wilkinson, D.; Surkova, Е.I.; Semina, Е.V.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Tkachuk, V.А. Detection of T-Cadherin Expression in Mouse Embryos. ActaNaturae 2015, 7, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.S.; Brodsky, I.B.; Balatskaya, M.N.; Balatskiy, A.V.; Ozhimalov, I.D.; Kulebyakina, M.A.; Semina, E.V.; Arbatskiy, M.S.; Isakova, V.S.; Klimovich, P.S.; et al. T-Cadherin Deficiency Is Associated with Increased Blood Pressure after Physical Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Org, E.; Eyheramendy, S.; Juhanson, P.; Gieger, C.; Lichtner, P.; Klopp, N.; Veldre, G.; Döring, A.; Viigimaa, M.; Sõber, S.; et al. Genome-wide scan identifies CDH13 as a novel susceptibility locus contributing to blood pressure determination in two European populations. Human. Molecular Genet. 2009, 18, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippova, M.; Banfi, A.; Ivanov, D.; Gianni-Barrera, R.; Allenspach, R.; Erne, P.; Resink, T. Atypical GPI-Anchored T-Cadherin Stimulates Angiogenesis In Vitro and In Vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2222–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, H.; Shi, D. Decoding the enigmatic role of T-cadherin in tumor angiogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1564130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Joshi, M.B.; Ivanov, D.; Feder-Mengus, C.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Martin, I.; Erne, P.; Resink, T.J. Use of multicellular tumor spheroids to dissect endothelial cell–tumor cell interactions: A role for T-cadherin in tumor angiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4523–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, V.A.; Bochkov, V.N.; Philippova, M.P.; Stambolsky, D.V.; Kuzmenko, E.S.; Sidorova, M.V.; Molokoedov, A.S.; Spirov, V.G.; Resink, T.J. Identification of an atypical lipoprotein-binding protein from human aortic smooth muscle as T-cadherin. FEBS Lett. 1998, 421, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatskaya, M.N.; Sharonov, G.V.; Baglay, A.I.; Rubtsov, Y.P.; Tkachuk, V.A. Different spatiotemporal organization of GPI-anchored T-cadherin in response to low-density lipoprotein and adiponectin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 129414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Tobe, T.; Choi-Miura, N.H.; Mazda, T.; Tomita, M. Isolation and characterization of GBP28, a novel gelatin-binding protein purified from human plasma. J. Biochem. 1996, 120, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Nio, Y.; Maki, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Takazawa, T.; Iwabu, M.; Okada-Iwabu, M.; Kawamoto, S.; Kubota, N.; Kubota, T.; et al. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada-Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iwabu, M.; Honma, T.; Hamagami, K.-I.; Matsuda, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tanabe, H.; Kimura-Someya, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 2013, 503, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okita, T.; Kita, S.; Fukuda, S.; Fukuoka, K.; Kawada-Horitani, E.; Iioka, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujishima, Y.; Nishizawa, H.; Kawamori, D.; et al. Soluble T-cadherin promotes pancreatic β-cell proliferation by upregulating Notch signaling. iScience 2022, 25, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, A.; Aubert, R.; Bellili-Muñoz, N.; Balkau, B.; Bonnet, F.; Tichet, J.; Velho, G.; Marre, M.; Roussel, R.; Fumeron, F. T-cadherin gene variants are associated with type 2 diabetes and the Fatty Liver Index in the French population. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 43, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S.; Kita, S.; Miyashita, K.; Iioka, M.; Murai, J.; Nakamura, T.; Nishizawa, H.; Fujishima, Y.; Morinaga, J.; Oike, Y.; et al. Identification and Clinical Associations of 3 Forms of Circulating T-cadherin in Human Serum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, R.; Nigro, E.; Fei, L.; De Magistris, L.; Monaco, M.L.; D’Amico, R.; Naviglio, S.; Signoriello, G.; Daniele, A. Adiponectin Is Inversely Associated With Tumour Grade in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 3751–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Epitope Mapping System: RIEDL Insertion for Epitope Mapping Method. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2021, 40, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of an Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody Using PA Scanning and RIEDL Scanning. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2024, 43, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippova, M.; Joshi, M.B.; Kyriakakis, E.; Pfaff, D.; Erne, P.; Resink, T.J. A guide and guard: The many faces of T-cadherin. Cell. Signal. 2009, 21, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K. A cancer-specific monoclonal antibody recognizes the aberrantly glycosylated podoplanin. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimori, T.; Mihara, E.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Takagi, J.; Kato, Y. Locally misfolded HER2 expressed on cancer cells is a promising target for development of cancer-specific antibodies. Structure 2024, 32, 536–549.e535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).