Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

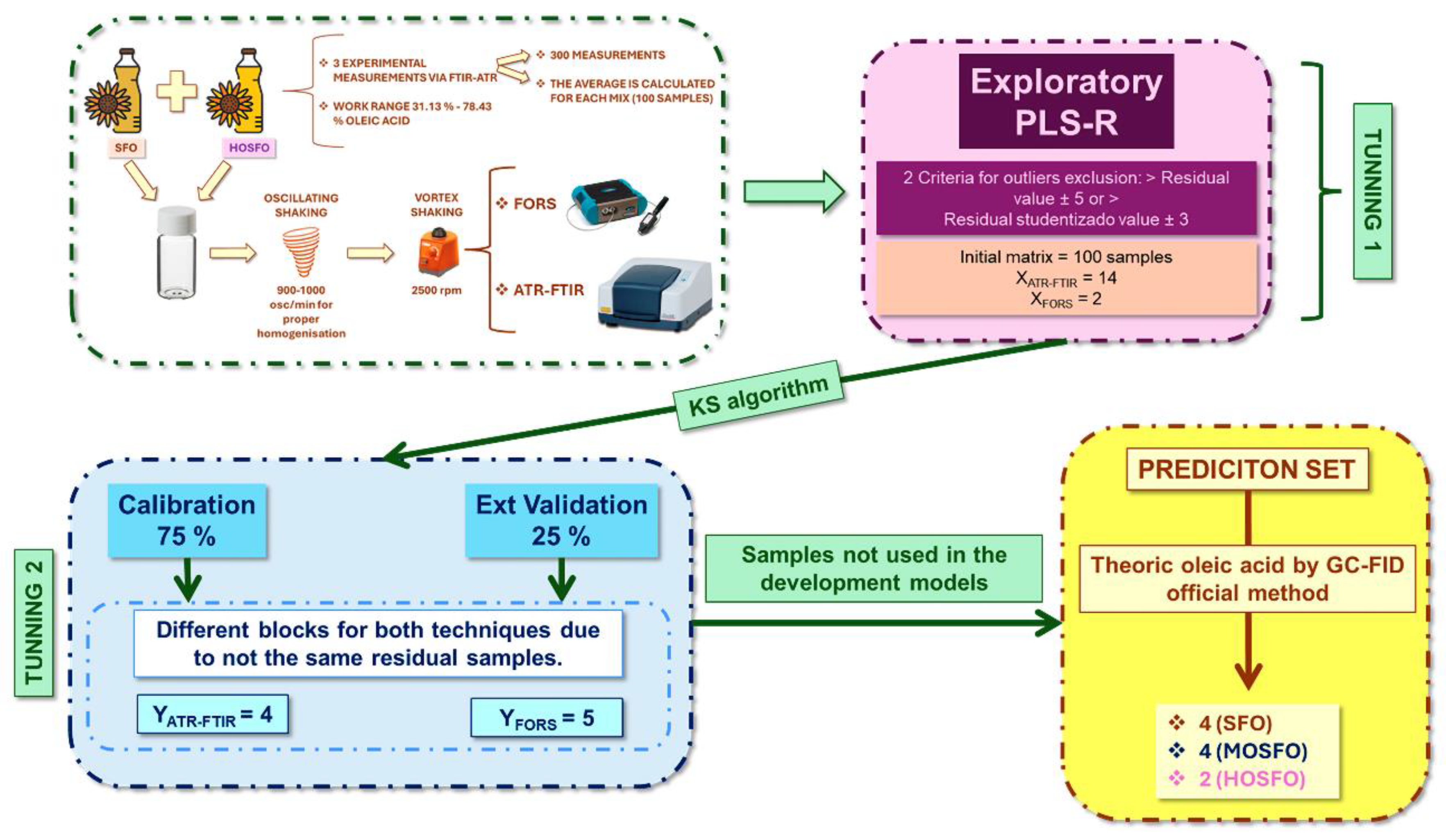

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Bank

2.1.1. Commercial Sunflower Oils

2.1.2. Binary Blends (SFO/HOSFO and MOSFO/HOSFO)

2.2. GC-FID for the Determination of Oleic Acid Content in Commercial Sunflower Oils

2.2.1. Reagents and Solvents

2.2.2. Chromatographic Conditions

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. ATR-FTIR Benchtop Instrument – Specifications and Methodology

2.3.2. FORS Portable Device - Specifications

2.4. Spectroscopic Analysis

2.4.1. ATR-FTIR – Data Pre-Processing and Spectral Elucidation

2.4.2. FORS – Data Pre-Processing and Spectral Elucidation

2.5. Chemometric Methodology

2.5.1. Authentication of All Types of Commercial Sunflower Oils

2.5.2. Quantification of Oleic Acid in Commercial Sunflower Oils

3. Results and Discussion

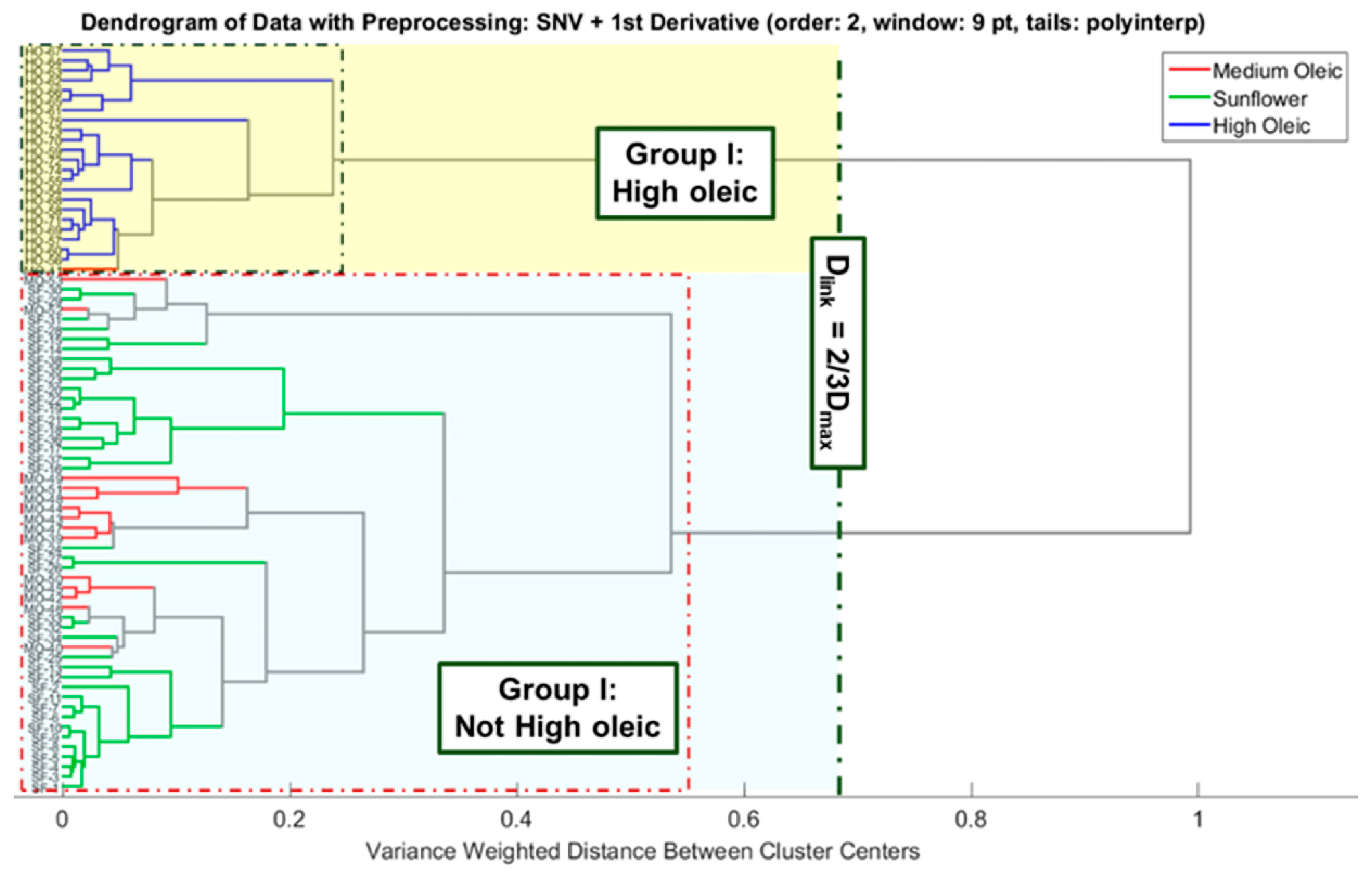

3.1. Unsupervised Pattern Recognition Methods of ATR-FTIR Sunflower Oil Fingerprints

3.1.1. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA)

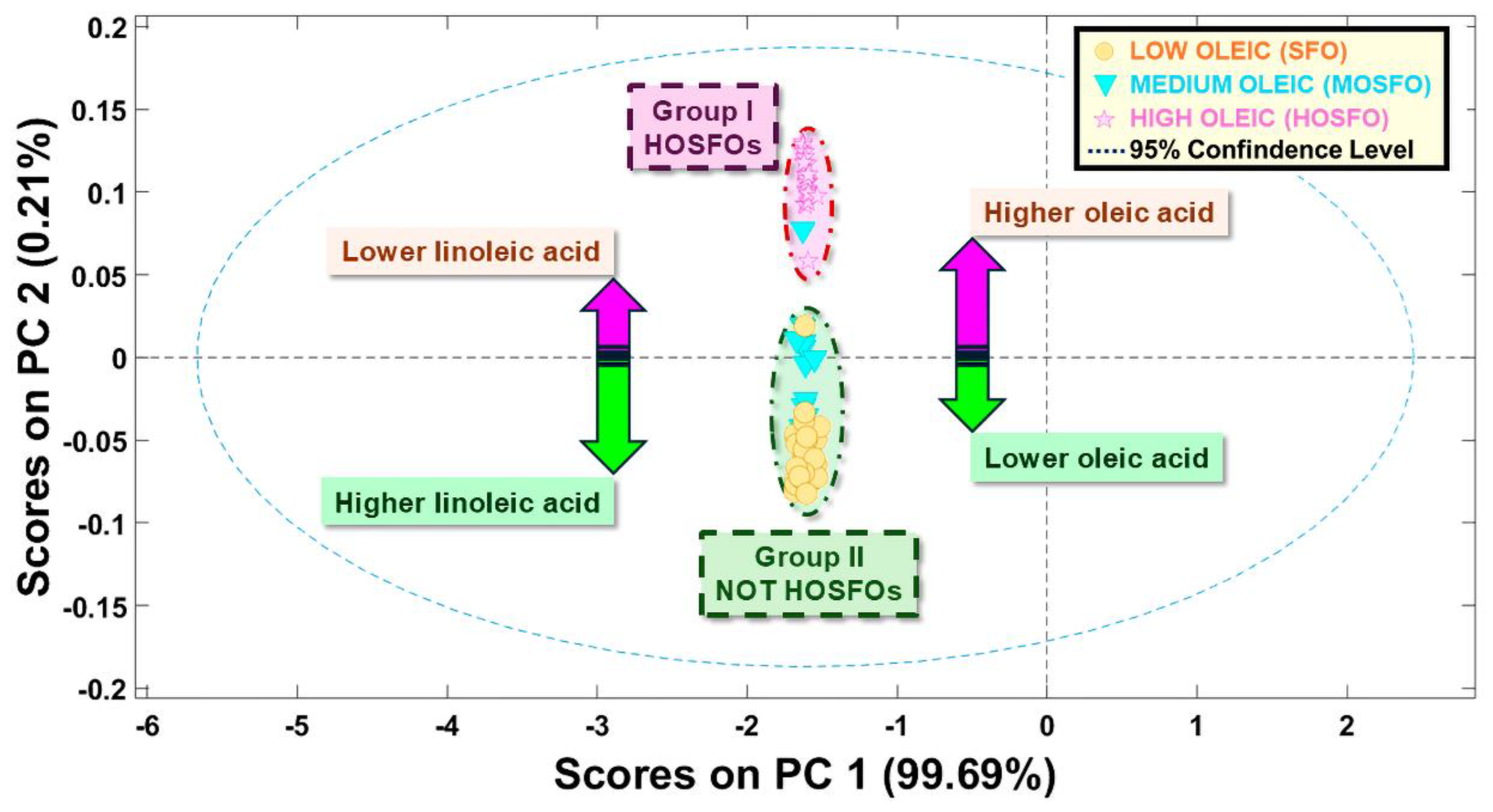

3.1.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.2. Supervised Chemometric Models of ATR-FTIR Sunflower Oil Fingerprints

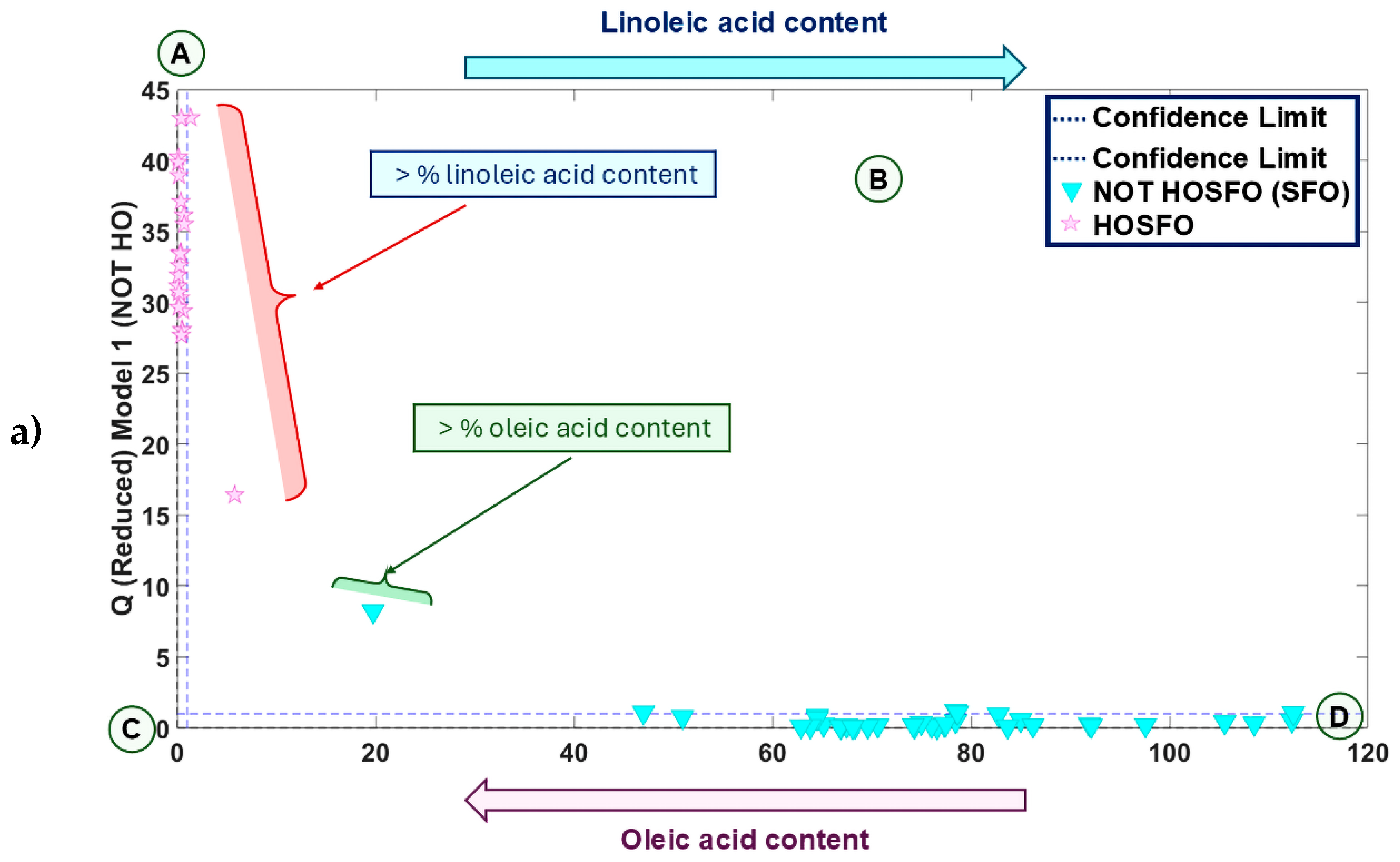

3.2.1. SIMCA Model for Authentication of All Sunflower oil Types

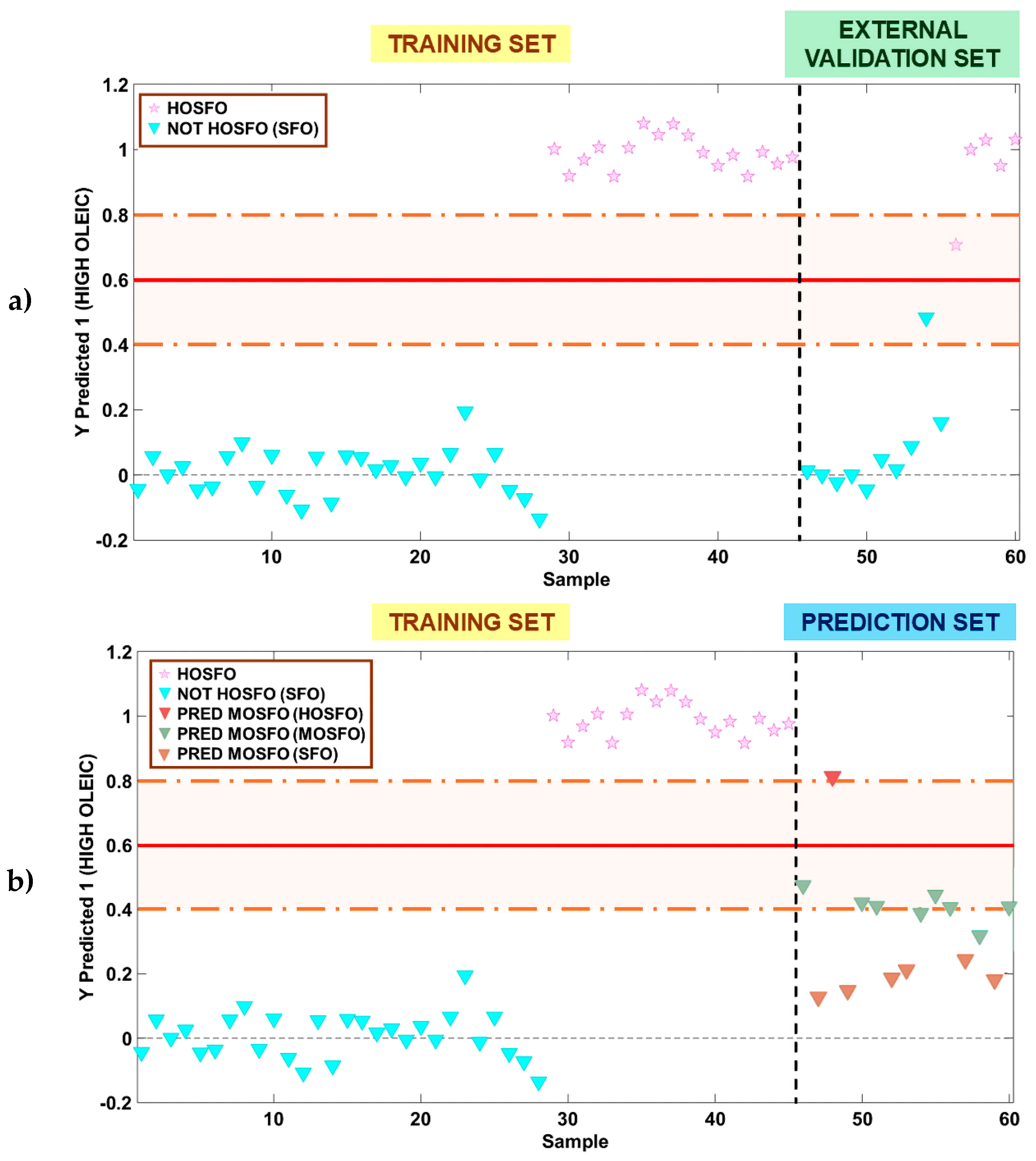

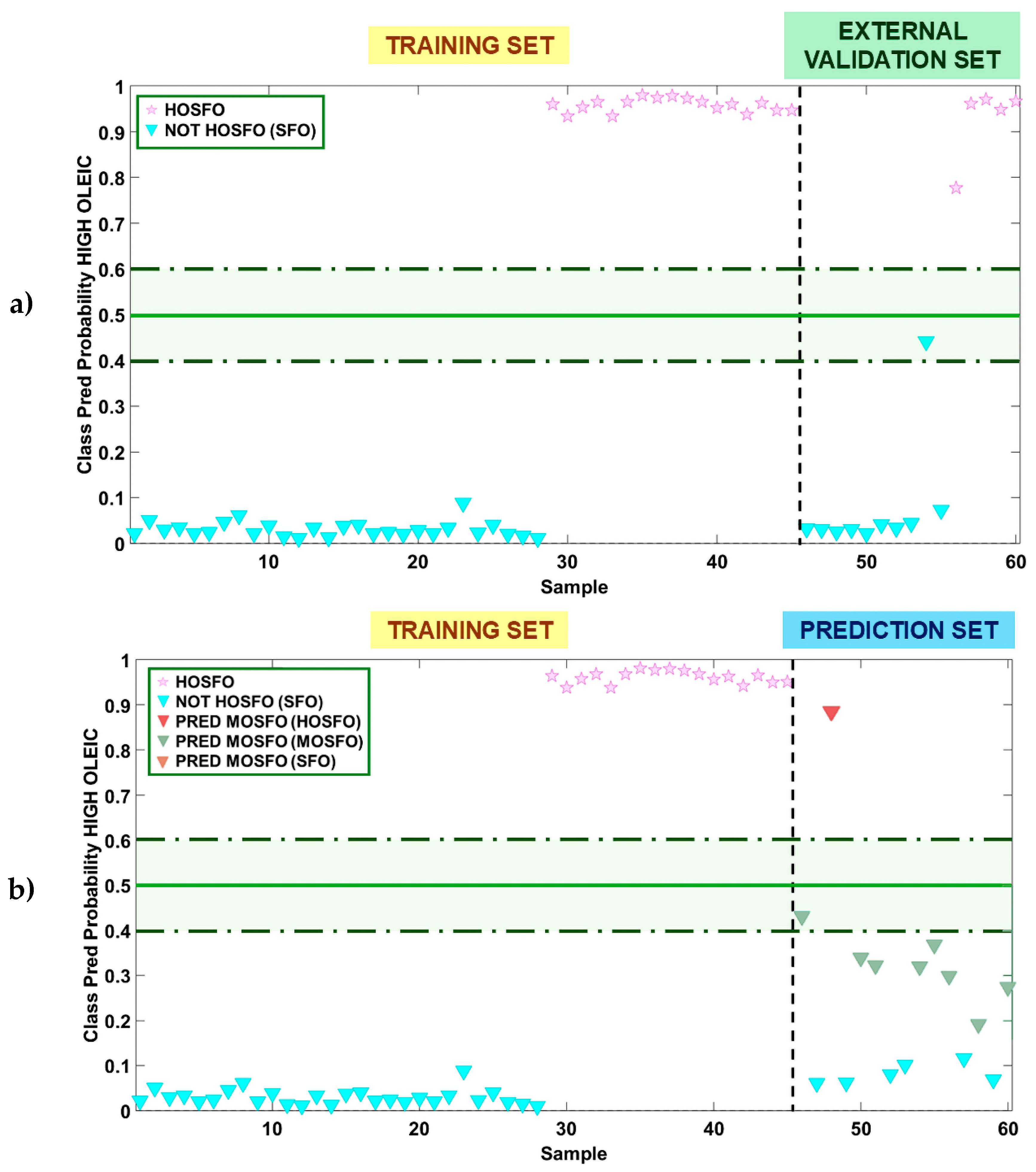

3.2.2. PLS-DA Model for Authentication of All Sunflower Oil Types

3.2.3. SVM Model for Authentication of All Sunflower Oil Types

3.3. Quantification of Oleic Acid in Commercial Sunflower Oils by PLS-R Model

- i)

- Model 1: built with ATR-FTIR. MIR fingerprints

- ii)

- Model 2: built with FORS. NIR fingerprints

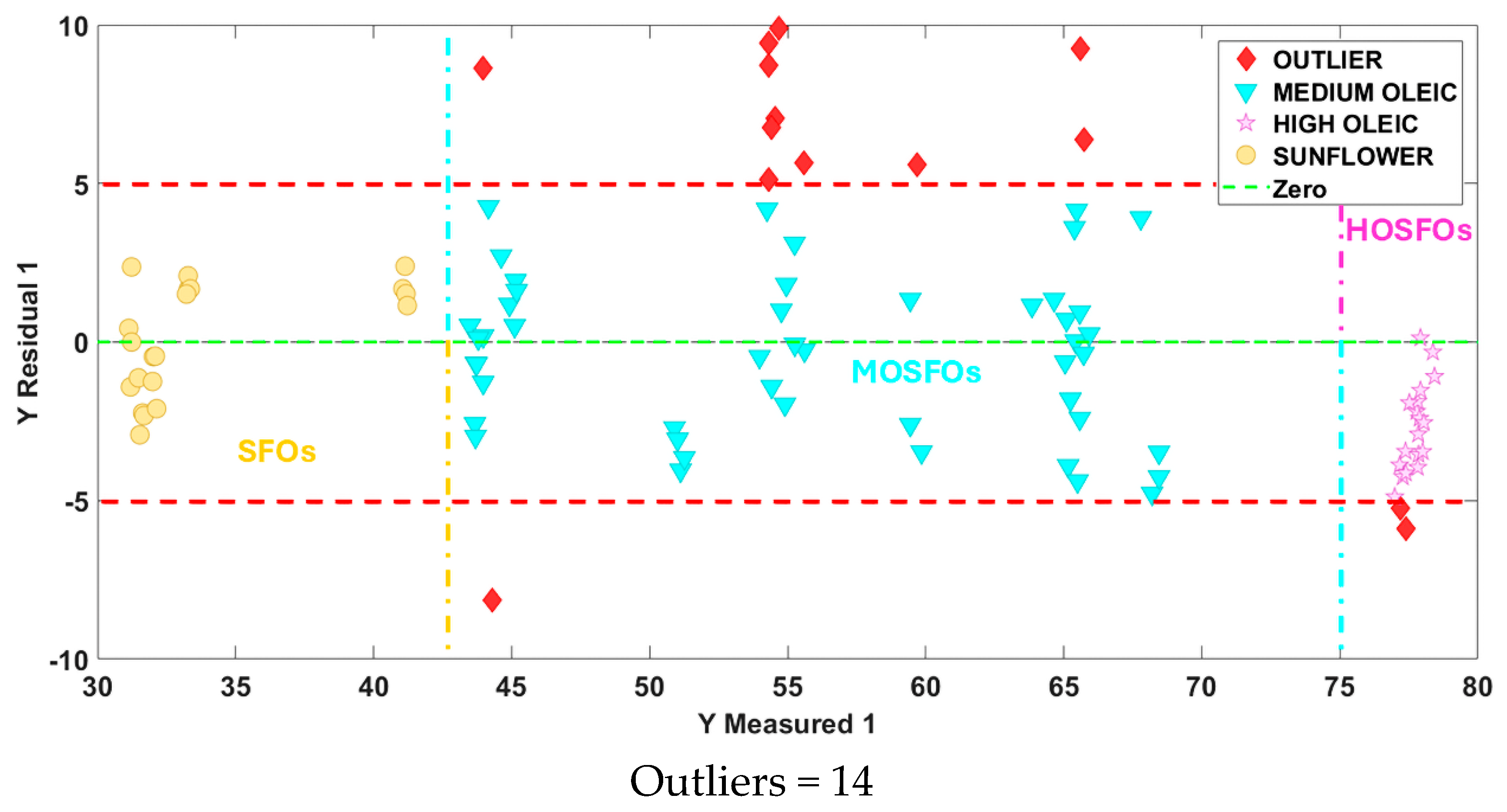

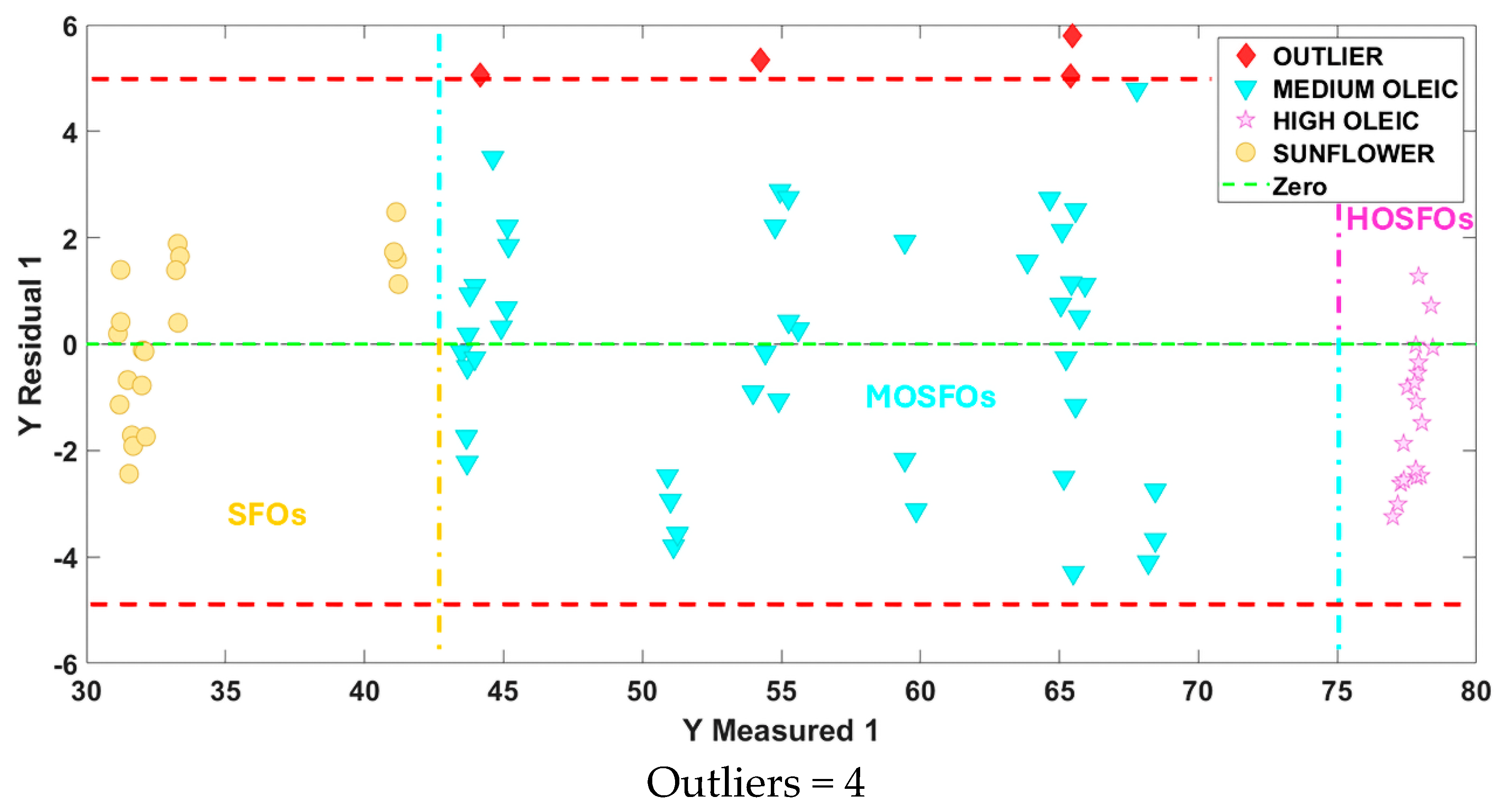

3.4.1. PLS-R Model 1 Built with ATR-FTIR. MIR Fingerprints

3.4.1.1. Tuning 1: Exploratory PLS-R

3.4.1.2. Tuning 2: Establishment of the PLS-R Model 1

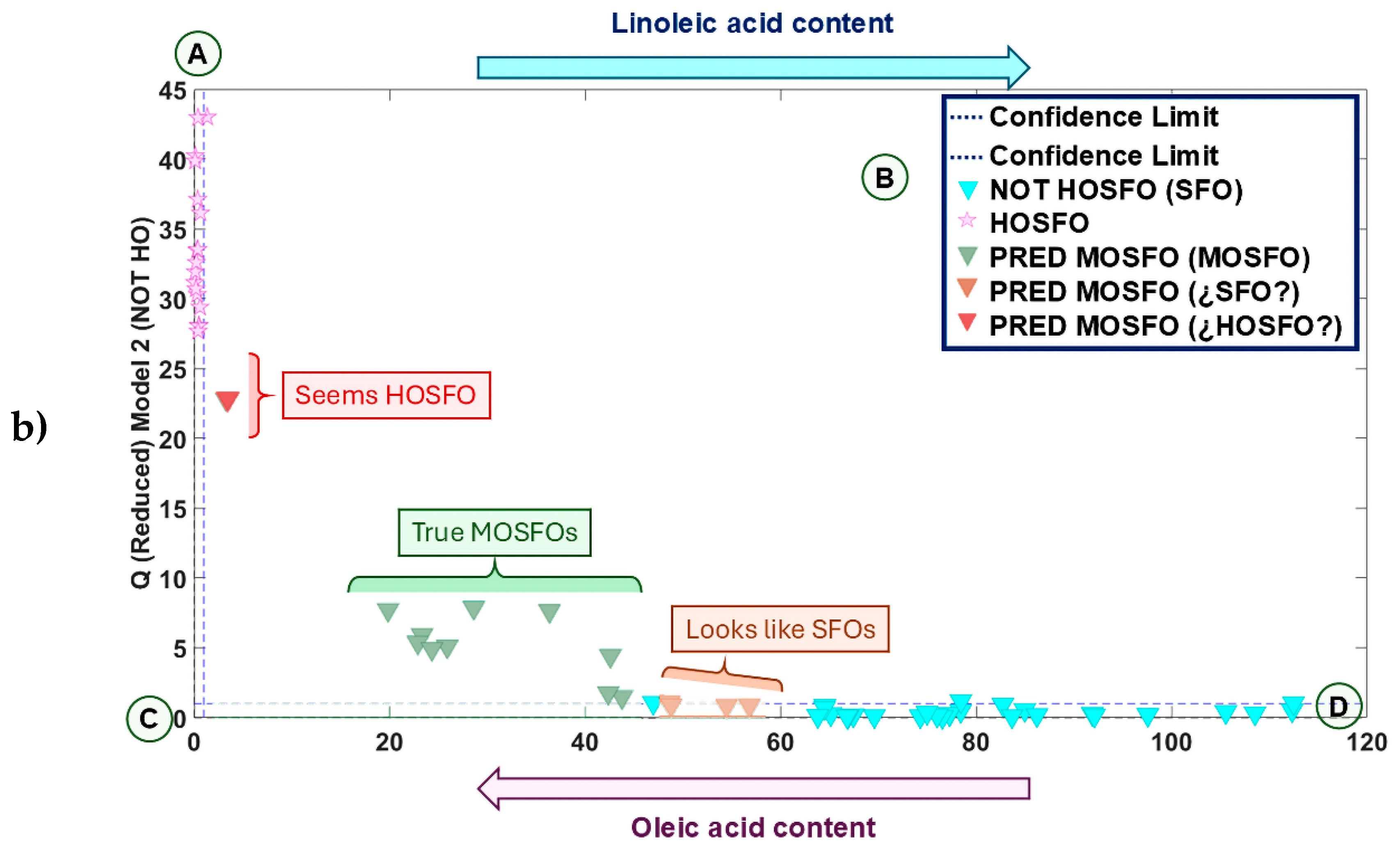

3.4.2. PLS-R Model 2 Development with FORS. NIR Fingerprints

3.4.2.1. Tuning 1: Exploratory PLS-R

3.4.2.2. Tuning 2: Establishment of the PLS-R Model 2

3.4.3. Evaluation of the Predictive Capability of the PLS-R Models

3.4.4. Quantification of Oleic Acid in MOSFOs and Inconclusive Samples of the Study of Authentication Using ATR FTIR Fingerprints

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Murphy, D. J. Agronomy and Environmental Sustainability of the Four Major Global Vegetable Oil Crops: Oil Palm, Soybean, Rapeseed, and Sunflower. Agronomy 2025, 15(6), 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, V.; Topalov, A.; Khudolii, L.; Honcharuk, Y.; Bondar, V. Profiling and geographical distribution of seed oil content of sunflower in Ukraine. Oil crop sci. 2023, 8(2), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilorgé, E. Sunflower in the global vegetable oil system: situation, specificities and perspectives. OCL 2020, 27(34). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonechna, K.; Ilko, V.; Berčíková, M.; Vietoris, V.; Panovská, Z.; Doležal, M. Nutritional, utility, and sensory quality and safety of sunflower oil on the central European market. Agriculture 2024, 14(4), 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Standard for named vegetable oils CSX 210-1999. Codex Alimentarius (2025). Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/es/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B210-1999%252FCXS_210e.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Real Decreto 351/2025 (30th april) approving the quality standard for edible vegetable oils. Boletín Oficial del Estado, No. 119, of 17 May 2025; BOE A 2025 9738. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?lang=es&id=BOE-A-2025-9738.

- Soldatov, K. Chemical Mutagenesis in Sunflower Breeding. Proceedings of the 7th International Sunflower Conference, Krasnodar, USSR, International Sunflower Association, Vlaardingen, The Netherlands (1976), pp. 352-357.

- Dunford, N. T. Martínez-Force, E.; Salas, J. J. (2022). Chapter 5 – High-oleic sunflower seed oil. In High Oleic Oils. Flider, F. J. (Ed.), Development, Properties, and Uses (pp. 109-124). American Oil Chemist’s Society Press. [CrossRef]

- Uslu, Y. Z.; Ural, B. N.; Cebrailoglu, N.; Aydın, Y.; Ciftci, Y. O.; Uncuoglu, A. A. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of FAD2-1 gene for oleic acids composition in sunflower. G&A 2022, 6(2), 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, A.; León, A.; Garcés, R. Mutagenesis in sunflower. In Sunflower; AOCS Press, 2015; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Graña, S.; Abarquero, D.; Claro, J.; Combarros-Fuertes, P.; Fresno, J.M.; Eugenia; Tornadijo, M. Behaviour of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) oil and high oleic sunflower oil during the frying of churros. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Graña, S.; Abarquero, D.; Claro, J.; Combarros-Fuertes, P.; Fresno, J.M.; Eugenia; Tornadijo, M. Behaviour of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) oil and high oleic sunflower oil during the frying of churros. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 20/Rev. 4; Method of Analysis. Difference between Actual and Theoretical Content of Triacyclglycerols with ECN 42. International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 33/Rev.1 2017. Determination of fatty acid methyl esters by gas chromatography. Madrid: International Olive Council (IOC).

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 26/Rev. 4; Determination of the Sterol Composition and Content and Alcoholic Compounds by Capillary Gas Chromatography. International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Pointner, T.; Rauh, K.; Auñon-Lopez, A.; Veličkovska, S. K.; Mitrev, S.; Arsov, E.; Pignitter, M. Comprehensive analysis of oxidative stability and nutritional values of germinated linseed and sunflower seed oil. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, H.; Drira, M.; Bouaziz, M. Targeted authentication approach for the control of the contamination of refined olive oil by refined seeds oils using chromatographic techniques and chemometrics models. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247(10), 2455–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Zhu, M.; Shi, T.; Luo, X.; Gan, B.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y. Adulteration detection of corn oil, rapeseed oil and sunflower oil in camellia oil by in situ diffuse reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Control 2021, 121, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taous, F.; El Ghali, T.; Marah, H.; Laraki, K.; Islam, M.; Cannavan, A.; Kelly, S. Geographical classification of authentic Moroccan Argan oils and the rapid detection of soya and sunflower oil adulteration with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15(11), 3032–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Srivastava, S.; Mishra, H. N.; Banerjee, S. Determination of curcumin content in sunflower oil by fourier transform near infrared spectroscopy. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Hernández, G.; Ortega-Gavilán, F.; González-Casado, A.; Bagur-González, M. G. Using a portable Raman-SORS spectrometer as an easy way to authenticate high oleic sunflower oil. Food Control 2025, 111443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, J.; Ghosh, M.; Mishra, H. N. Rapid quantification of cholesterol in dairy powders using Fourier transform near infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Control 2017, 78, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehany, T.; González-Sáiz, J. M.; Pizarro, C. The Quality Prediction of Olive and Sunflower Oils Using NIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics: A Sustainable Approach. Foods 2025, 14(13), 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Saona, L. E.; Allendorf, M. E. Use of FTIR for rapid authentication and detection of adulteration of food. ARFST 2011, 2(1), 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, N.; Weng, S.; Wang, L.; Xu, T. Reflectance spectroscopy with multivariate methods for non-destructive discrimination of edible oil adulteration. Biosensors 2021, 11(12), 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García del Moral, L.F.; Morgado, A.; Esquivel, J.A. Espectroscopia de Reflectancia de Fibra Óptica (FORS) de las principales canteras de rocas silíceas de Andalucía y su aplicación a la identificación de la procedencia de artefactos líticos tallados durante la Prehistoria. Complutum 2022, 33, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Stephen, J.; Mathew, J. Fiber Optic Device for the Detection of Adulteration of Olive Oil With Palm Oil. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2025, 67(5), e70210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, N.; Pawluczyk, O.; Dugan, M. E. R.; Aalhus, J. L. A review of the principles and applications of near-infrared spectroscopy to characterize meat, fat, and meat products. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 71(7), 1403–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, S.; Pereira, J. A.; Silva, P.; Perestrelo, R.; Câmara, J. S. Food Fingerprints – A Valuable Tool to Monitor Food Authenticity and Safety. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M. J. E. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36(8), 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M.; Pan, T.; Chen, X. D. Application of second derivative spectrum prepares in quantification measuring glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate using a FTIR/ATR method. Optics and Precision Engineering 2006, 14(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bathini, V.; Kalakandan, S. K.; Pakkirisamy, M.; Ravichandran, K. Structural elucidation of peanut, sunflower and gingelly oils by using FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy. Phcog J. 2018, 10(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiana, M. A.; Mousdis, G.; Alexa, E.; Moigradean, D.; Negrea, M.; Mateescu, C. Application of FT-IR spectroscopy to assess the olive oil adulteration. J. Agroaliment. Process Technol. 2012, 18(4), 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; Yao, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, L. M.; Wang, H. X. Investigation on the quality diversity and quality-FTIR characteristic relationship of sunflower seed oils. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 27347–27360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, M.D.; Cabo, N. Usefulness of the frequencies of some Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic bands for evaluating the composition of edible oil mixtures. Lipids/fett 1999, 101(1), 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Pan, T.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Ren, X. Joint optimization of Savitzky-Golay smoothing models and partial least squares factors for near-infrared spectroscopic analysis of serum glucose. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2010, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, B. G.; Fearn, T.; Hindle, P. H. Practical NIR spectroscopy with applications in food and beverage analysis; 1993; 227. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sánchez, N.; Gómez-Del-Campo, M. From NIR spectra to singular wavelengths for the estimation of the oil and water contents in olive fruits. Grasas Y Aceites 2018, 69(4), e278–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourant, P.; Baeten, V.; Morales, M. T.; Meurens, M.; Aparicio, R. Oil and fat classification by selected bands of near-infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000, 54(8), 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Cuevas, M. M.; Garrido-Varo, A. M.; Marini, F.; Sánchez, M. T.; Pérez-Marín, D. Enhancing virgin olive oil authentication with Bayesian probabilistic models and near infrared spectroscopy. J Food Eng. 2025, 391, 112443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, R.; Stone, L. Computer Aided Design of Experiments. Technometrics 1969, 11, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. C., & Sobering, D. C. (1996). How do we do it: a brief summary of the methods we use in developing near infrared calibrations. Near infrared spectroscopy: The future waves, 185-188.

- Guerrero, C.; Zornoza, R.; Perez-Belmonte, A.; Bejarano, J.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Gómez- Lucas, I.; García-Orenes, F. Uso de la espectroscopía en el infrarrojo cercano (NIR) para la estimación rápida del carbono orgánico y la respiración basalen suelos forestales. Cuad. Soc. Esp. Cienc. For. 2008, 25, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, J.; McGoverin, C.; Oey, I.; Frew, R.; Kebede, B. Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy accurately predicted isotope and elemental compositions for origin traceability of coffee. Food Chem. 2023, 427, 136695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SEP | RPD | RER |

|---|---|---|

| 2.11 | 7.37 | 23.34 |

| SEP | RPD | RER |

|---|---|---|

| 2.24 | 6.51 | 22.67 |

| PLS-R | SEP | RPD | RER |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATR-FTIR (MODEL 1) | 3.07 | 7.09 | 17.82 |

| FORS (MODEL 2) | 4.73 | 4.60 | 11.58 |

| CODE | PREDICTED OLEIC ACID CONTENT (%) USING PLS-R MODEL 1 (ATR-FTIR) | SUNFLOWER OIL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| SFO-24 | 56.02 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-39 | 56.40 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-40 | 39.19 | SFO |

| MOSFO-41 | 72.29 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-42 | 39.19 | SFO |

| MOSFO-43 | 53.23 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-44 | 52.40 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-45 | 41.03 | SFO |

| MOSFO-46 | 42.51 | SFO |

| MOSFO-47 | 53.49 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-48 | 56.91 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-49 | 53.86 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-50 | 43.83 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-51 | 50.88 | MOSFO |

| MOSFO-52 | 39.45 | SFO |

| MOSFO-53 | 50.88 | MOSFO |

| HOSFO-54 | 67.32 | MOSFO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).