Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

12 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. TOF-SIMS Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterization of Pure Saffron, Safflower and Turmeric

3.2. Characterization of Saffron Adulterated with Safflower and Turmeric

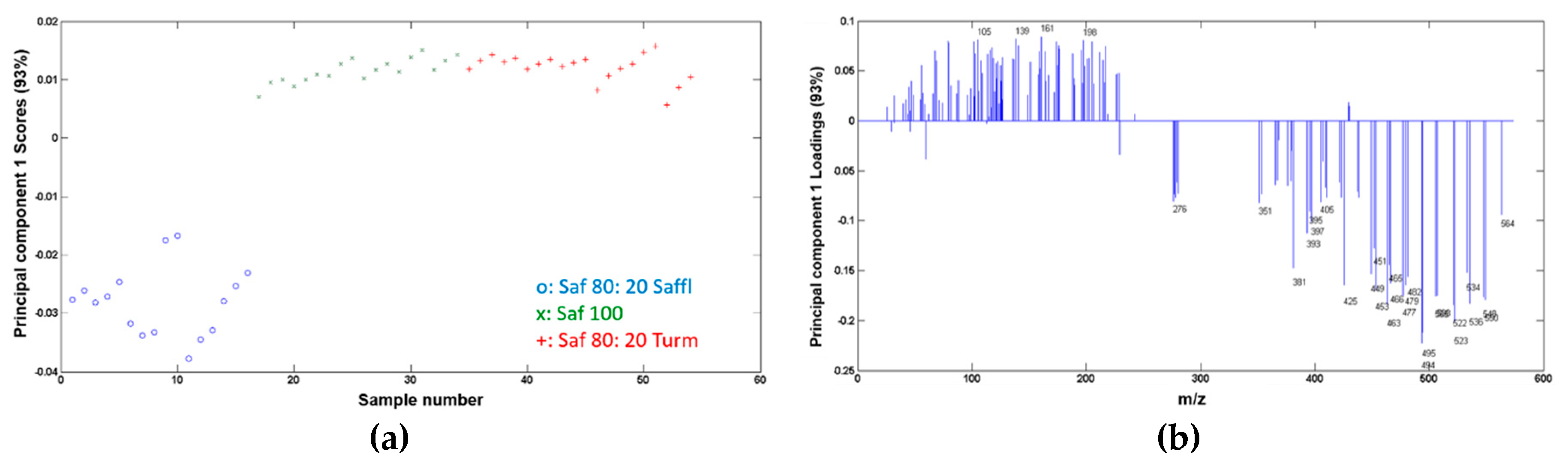

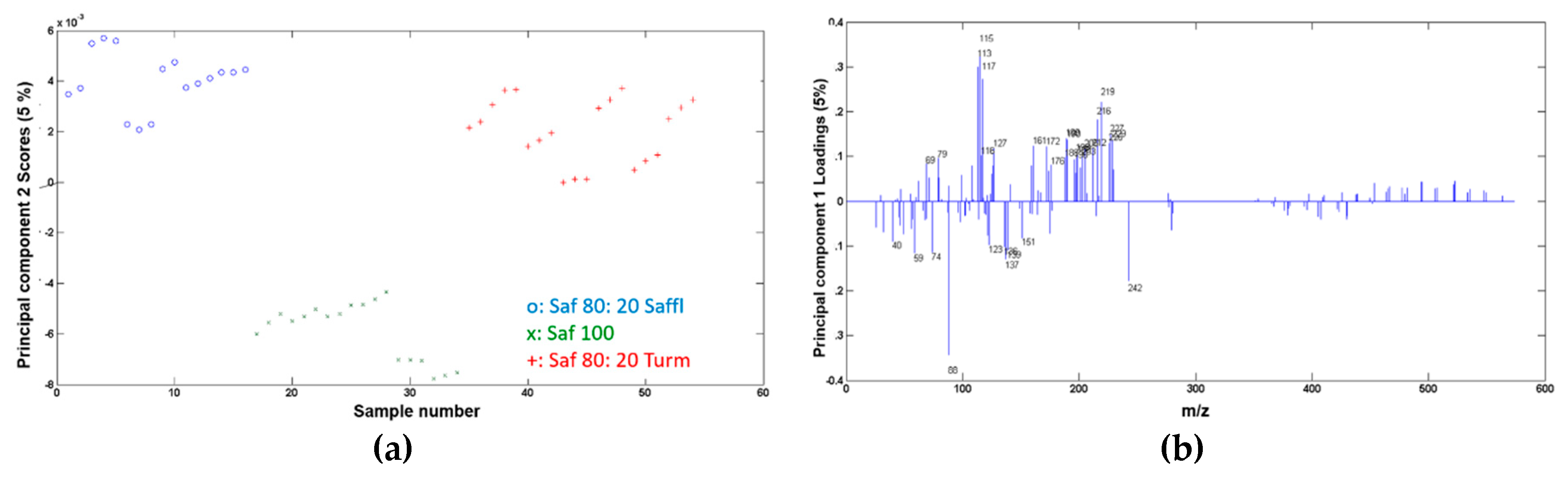

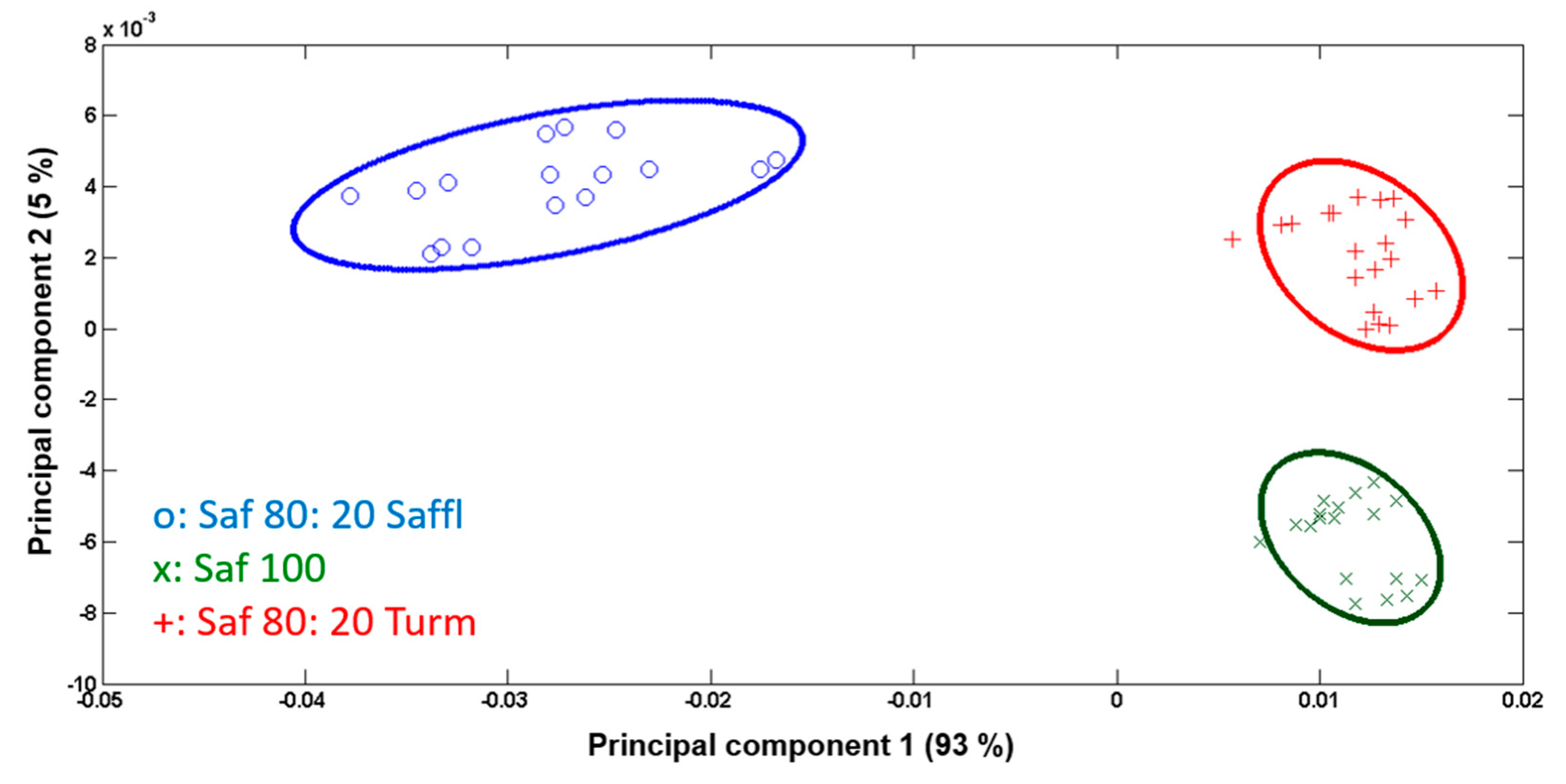

3.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

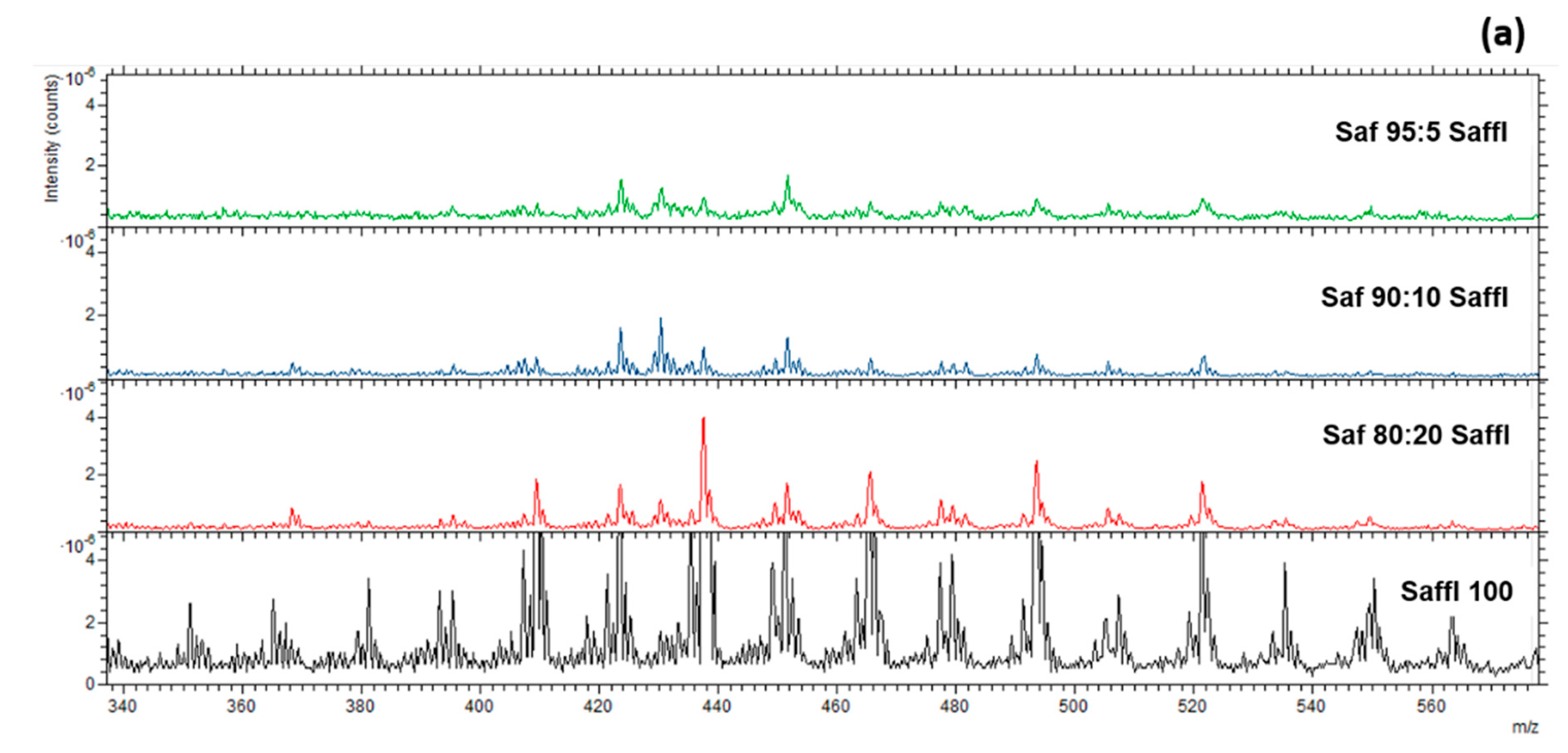

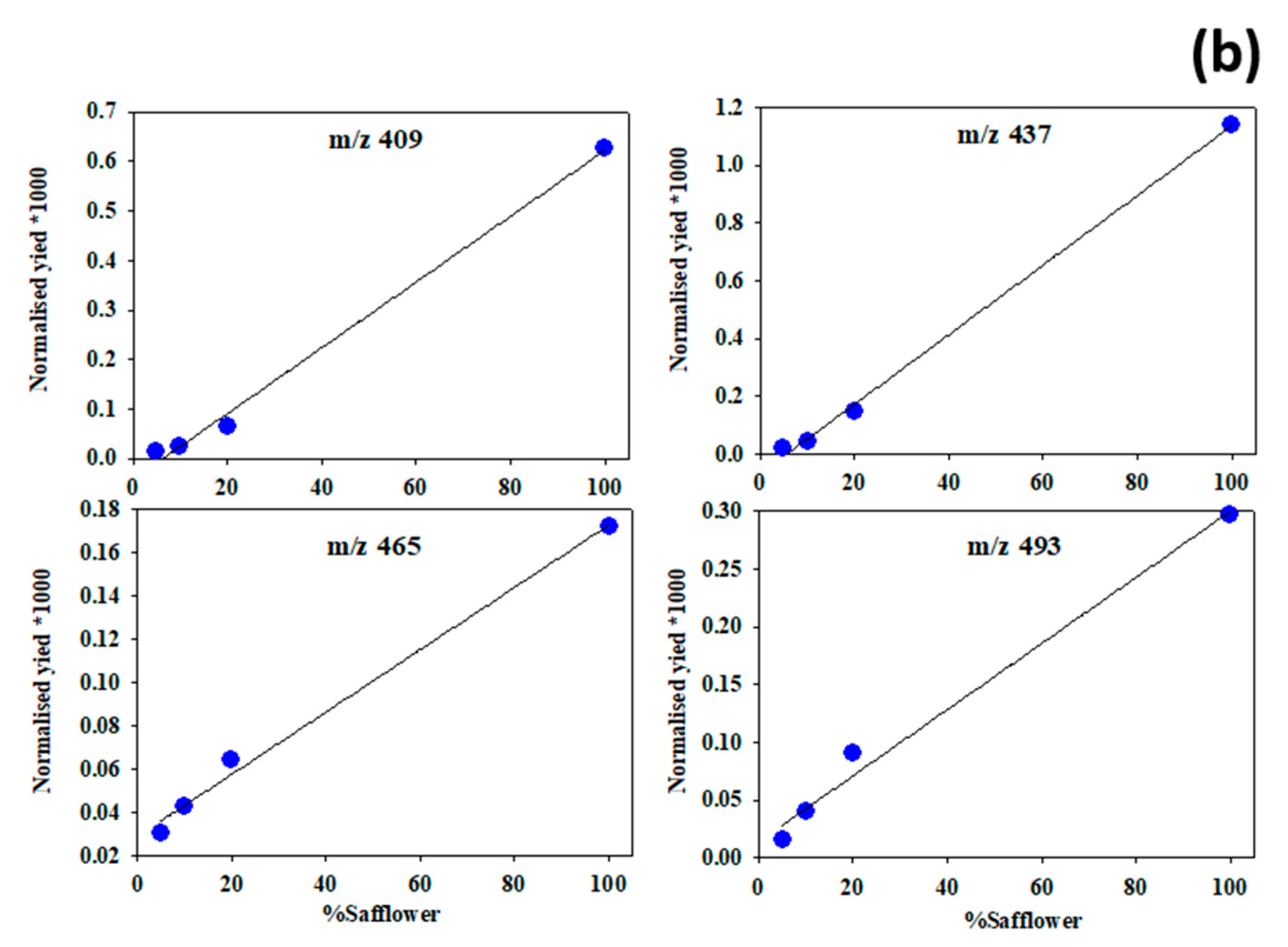

3.4. Semi-Quantification of Safflower

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eghbali, S.; Farhadi, F.; Askari, V.R. An Overview of Analytical Methods Employed for Quality Assessment of Crocus Sativus (Saffron). Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunanda, B.P.V.; Rammohan, B.; Kumar, A. The Effective Study of Aqueous Extract of Crocus Sativus Linn. (Saffron) in Depressed Mice. Int. J. PharmTech Res 2014, 6, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Poma, A.; Fontecchio, G.; Carlucci, G.; Chichiriccò, G. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Drugs from Saffron Crocus. Anti-inflamm. Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarghandian, S.; Borji, A. Anticarcinogenic Effect of Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.) and Its Ingredients. Pharmacognosy Res. 2014, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papandreou, M.A.; Kanakis, C.D.; Polissiou, M.G.; Efthimiopoulos, S.; Cordopatis, P.; Margarity, M.; Lamari, F.N. Inhibitory Activity on Amyloid-β Aggregation and Antioxidant Properties of Crocus Sativus Stigmas Extract and Its Crocin Constituents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8762–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, L.; Qian, Z.; Zheng, S.; Xi, L. Mechanism of Hypolipidemic Effect of Crocin in Rats: Crocin Inhibits Pancreatic Lipase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 543, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopresti, A.L.; Drummond, P.D. Saffron (Crocus Sativus) for Depression: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies and Examination of Underlying Antidepressant Mechanisms of Action. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 29, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Karimi, G.; Niapoor, M. Antidepressant Effect of Crocus Sativus L. Stigma Extracts and Their Constituents, Crocin and Safranal, in Mice. Acta Hortic. 2004, 650, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsikas, N.; Zisopoulou, S.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Kanakis, C.D.; Polissiou, M.G.; Sakellaridis, N. Effects of the Active Constituents of Crocus Sativus L., Crocins on Recognition and Spatial Rats’ Memory. Behav. Brain Res. 2007, 183, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliani, L.R.; Culeddu, N.; Chessa, M.; Consonni, R. NMR Investigations for a Quality Assessment of Italian PDO Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.). Food Control 2015, 50, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO-3632-2-2010 Part 1: Specification, Part 2: Test Methods. International Organisation for Standardization, Geneva.

- Kumari, L.; Jaiswal, P.; Tripathy, S.S. Various Techniques Useful for Determination of Adulterants in Valuable Saffron: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Scordino, M.; Gargano, M.; Belligno, A.; Traulo, P.; Gagliano, G. HPLC/PDA/ESI-MS Evaluation of Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.) Adulteration. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 1873–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.H.; Sun, D.W. Hyperspectral Imaging as an Effective Tool for Quality Analysis and Control of Fish and Other Seafoods: Current Research and Potential Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 37, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; He, Y.; Xiao, Y. Rapid and Non-Destructive Measurement of Spinach Pigments Content during Storage Using Hyperspectral Imaging with Chemometrics. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2017, 97, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, F.; Ben Moumen, A.; Richard, G.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Sindic, M.; Elamrani, A.; Serghini Caid, H. Proximate Composition, Amino Acid Profile, Carbohydrate and Mineral Content of Seed Meals from Four Safflower (Carthamus Tinctorius L.) Varieties Grown in North-Eastern Morocco. OCL - Oilseeds fats, Crop. Lipids 2018, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Tyagi, A.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, a Component of Golden Spice: From Bedside to Bench and Back. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological Activities of Curcuminoids, Other Biomolecules from Turmeric and Their Derivatives – A Review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawecki, M.; Bernard, L. Database of Proteinogenic Amino Acid Reference Spectra for Bismuth-Cluster ToF-SIMS. II. Positive Polarity. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizy, J.; Jahani, M.; Moradi, E.; Ahmadi, S. Measurement of Minerals in S Affron ’ s Stamens, Petals and Styles. 2022, 10, 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Pittenauer, E.; Koulakiotis, N.S.; Tsarbopoulos, A.; Allmaier, G. In-Chain Neutral Hydrocarbon Loss from Crocin Apocarotenoid Ester Glycosides and the Crocetin Aglycon (Crocus Sativus L.) by ESI-MSn (n = 2, 3). J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 48, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, E.; Pilolli, R.; Bejjani, A.; Guagnano, R.; Garino, C.; Arlorio, M.; Monaci, L. Optimization of an Untargeted Dart-Hrms Method Envisaging Identification of Potential Markers for Saffron Authenticity Assessment. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belu, A.M.; Graham, D.J.; Castner, D.G. Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry: Techniques and Applications for the Characterization of Biomaterial Surfaces. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3635–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, P. Static SIMS for Analysis of Molecular Conformation and Orientation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 6986–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benninghoven, A. Surface Analysis by Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Surf. Sci. 1994, 299–300, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejjani, A.; Noun, M.; Della-Negra, S.; Tannous, R.; Chalhoub, G.; Hamdan, M.; Nsouli, B. Topography Measurements Using High Mass Resolution Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry: Application to Banknotes. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 8864–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, B.J.; Peterson, R.E.; Lee, T.G.; Draude, F.; Pelster, A.; Arlinghaus, H.F. ToF-SIMS Imaging of Capsaicinoids in Scotch Bonnet Peppers (Capsicum Chinense). Biointerphases 2016, 11, 02A327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliff, B.; Weibel, D.E.; Lockyer, N.P.; Jungnickel, H. Detection of Chlorinated Pesticides on the Surface of Fungus Using ToF-SIMS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 204, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focardi, S.; Ristori, S.; Mazzuoli, S.; Tognazzi, A.; Leach-scampavia, D.; Castner, D.G.; Rossi, C. ToF-SIMS and PCA Studies of Seggianese Olives and Olive Oil. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006, 279, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, C.; Felicissimo, M.P.; Pireaux, J.-J.; Houssiau, L. Study of Annatto from Bixa Orellana Seeds: An Application of Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry. Spectrosc. Eur. 2005, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Piras, F.M.; Dettori, M.F.; Magnani, A. ToF-SIMS PCA Analysis of Myrtus Communis L. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 7805–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOF-SIMS: Surface Analysis by Mass Spectrometry; Vickerman, J.C., Briggs, D., Eds.; 2nd editio.; IM publications, 2013, ISBN 978-1-906715-17-5.

- Graham, D.J.; Castner, D.G. Multivariate Analysis of ToF-SIMS Data from Multicomponent Systems: The Why, When, and How. Biointerphases 2012, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Pharmacokinetic Properties of Saffron and Its Active Components. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 43, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, J.P.; Wang, S.; Marcone, M.F. Chemical and Biological Properties of the World’s Most Expensive Spice: Saffron. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, M.A.; Bisti, S.; Picco, C. Sa Ff Ron: Chemical Composition and Neuroprotective Activity. 1–15.

- Moratalla-López, N.; Bagur, M.J.; Lorenzo, C.; Martínez-Navarro, M.E.; Rosario Salinas, M.; Alonso, G.L. Bioactivity and Bioavailability of the Major Metabolites of Crocus Sativus L. Flower. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissa, R.; Ibourki, M.; Bouzid, H.A.; Bijla, L.; Oubannin, S.; Sakar, E.H.; Jadouali, S.; Hermansyah, A.; Goh, K.W.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Phytochemistry, Quality Control and Medicinal Uses of Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.): An Updated Review. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cao, J.; Deng, J.; Hou, X.; Hao, E.; Zhang, L.; Yu, H.; Li, P. Chemical Characterization of Flavonoids and Alkaloids in Safflower (Carthamus Tinctorius L.) by Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography Coupled with Hybrid Linear Ion Trap Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotha, R.R.; Luthria, D.L. Curcumin: Biological, Pharmaceutical, Nutraceutical, and Analytical Aspects. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.M.; Dahlin, J.L.; Bisson, J.; Graham, J.; Pauli, G.F.; Walters, M.A. The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1620–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, D.; Wang, R. Turmeric: A Review of Its Chemical; Elsevier Inc., 2018. ISBN 9780128115183.

- Aiello, D.; Siciliano, C.; Mazzotti, F.; Di Donna, L.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Napoli, A. Molecular Species Fingerprinting and Quantitative Analysis of Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.) for Quality Control by MALDI Mass Spectrometry†. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 36104–36113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulakiotis, N.S.; Pittenauer, E.; Halabalaki, M.; Tsarbopoulos, A.; Allmaier, G. Comparison of Different Tandem Mass Spectrometric Techniques (ESI-IT, ESI- and IP-MALDI-QRTOF and VMALDI-TOF/RTOF) for the Analysis of Crocins and Picrocrocin from the Stigmas of Crocus Sativus L. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 26, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T.; Tozu, M.; Ohashi, Y. Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry Can Replace Histochemistry Demonstration of Fatty Acids in the Retina. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 48, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, K.; Hoogland, F.; Boon, J.J.; Peggie, D.; Higgitt, C. Evaluation of the “Added Value” of SIMS: A Mass Spectrometric and Spectroscopic Study of an Unusual Naples Yellow Oil Paint Reconstruction. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 284, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjövall, P.; Rossmeisl, M.; Hanrieder, J.; Kuda, O.; Kopecky, J.; Bryhn, M. Dietary Uptake of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Mouse Tissue Studied by Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (Tof-Sims). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5101–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, K.J.; DeBord, J.D.; Fernandez-Lima, F. Lipid Specific Molecular Ion Emission as a Function of the Primary Ion Characteristics in TOF-SIMS. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B, Nanotechnol. Microelectron. Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2016, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grehk, T.M.; Berger, R.; Bexell, U. Investigation of the Drying Process of Linseed Oil Using FTIR and ToF-SIMS. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 100, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, Y.; Ishizaki, I.; Waki, M.; Ide, Y.; Hossen, M.A.; Ohnishi, K.; Miyayama, T.; Setou, M. Palmitic Acid, Verified by Lipid Profiling Using Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry, Demonstrates Anti-Multiple Myeloma Activity. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaş, S.; Mutlucan, M. Investigation of Flower Yield and Quality in Different Color Safflower Genotypes. Agronomy 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Changes of Anthocyanin and Amino Acid Metabolites in Saffron Petals (Crocus Sativus L.) during Fermentation Based on Untargeted Metabolomics. Lwt 2024, 192, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priscila del Campo, C.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Sánchez, A.M.; Maggi, L.; Carmona, M.; Alonso, G.L. Determination of Free Amino Acids and Ammonium Ion in Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.) from Different Geographical Origins. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G, C.; Lanza, B. Nutrients and Heavy Metals in Flowers and Corms of the Saffron Crocus (Crocus Sativus L.). Med. Aromat. Plants 2016, 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).