Introduction

Bipolar disorder complicated by obsessive–compulsive symptoms is notoriously hard to treat. Surveys place the lifetime prevalence of OCD in bipolar samples between 15% and 24%, climbing to almost 30% in paediatric-onset illness or bipolar I—four to five times the rate seen in the general population (3,4,5).

When the two conditions overlap, the obsessions and compulsions usually track the mood cycle: they intensify during depression, ease in hypomania or mania, and more often centre on aggressive, sexual, symmetry, or somatic themes than on classic contamination rituals (6,7). This “bipolar-OCD” pattern predicts more frequent depressive relapses, higher hospital use, and a greater risk of suicide than bipolar disorder alone (7).

Conventional OCD therapy—high-dose SSRIs, sometimes combined with exposure and response prevention—poses problems in this group. Without firm mood stabilisation, serotonergic monotherapy can drive manic or mixed switches in up to 60% of cases (7). Yet mood stabilisers by themselves often leave the obsessive–compulsive symptoms untouched, so many patients remain disabled.

Rapid-acting glutamatergic treatments such as intravenous ketamine or intranasal esketamine shorten depressive and obsessive episodes within hours, with response rates near 50–70% (1,2). Nevertheless, high cost, need for monitoring, and transient dissociation restrict their routine use.

Cheung (8) described a fully oral, inexpensive protocol designed to mimic ketamine’s plasticity cascade. The regimen pairs:

dextromethorphan, an NMDA-receptor antagonist and sigma-1 agonist;

a CYP2D6 inhibitor to lengthen dextromethorphan exposure;

piracetam, which positively modulates AMPA receptors; and

optional L-glutamine to restore presynaptic glutamate and temper excitotoxicity.

Early uncontrolled reports suggest fast, sometimes striking gains in refractory depression, mood-linked OCD, trauma-related states, and executive dysfunction—including in bipolar spectra (9,10,11,12).

We add three further cases of bipolar disorder with prominent obsessive–compulsive features—trichotillomania/onychophagia, somatic fixation on bladder emptying, and compulsive arranging with somatic delusions—in which standard serotonergic or dopaminergic approaches had failed or worsened mood. Stepwise use of the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen, adjusted for individual pharmacokinetics and mood stability, produced lasting remission of both affective and obsessive–compulsive symptoms, underscoring the promise of targeted NMDA–AMPA modulation for this difficult comorbidity.

Methods

Between May and November 2025, three adults attending a psychiatric clinic in Hong Kong SAR were treated with the glutamatergic protocol described in the accompanying cases. All met DSM-5 criteria for bipolar disorder (two bipolar I, one bipolar II) and displayed prominent obsessive-compulsive manifestations. Each had already failed several evidence-based trials that included high-dose selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, serotonin–noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors, atypical antipsychotics, and standard mood stabilisers, and all were symptomatic at the time of first contact.

Because every change formed part of routine, individualised care, no experimental procedures were introduced. Nevertheless, written permission to publish anonymised details of illness course, rating-scale scores and medication adjustments was obtained from all three patients in keeping with local guidelines for case-series reporting.

Follow-up appointments were scheduled roughly every two to four weeks, with telephone check-ins when necessary. At each encounter the psychiatrist carried out an unstructured clinical interview and full mental-state examination, then asked patients to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Additional questioning covered manic or hypomanic symptoms—elevated or irritable mood, curtailed sleep, impulsive spending, pressured speech—and the frequency and distress attached to their specific compulsions (hair-pulling, nail-biting, somatic worries, arranging rituals or checking). No structured instruments such as the Young Mania Rating Scale or the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale were employed; diagnostic and outcome judgments rested on longitudinal clinical observation supported by the two self-report measures.

Doses of dextromethorphan, the accompanying CYP2D6 inhibitor, piracetam, and other psychotropics were altered solely on the basis of clinical response, tolerability, and early warning signs of hypomania. When overactivation emerged, the first intervention was to lower the dextromethorphan and/or the metabolic inhibitor while maintaining, and occasionally increasing, the piracetam component.

After the last in-person review in late November 2025, the treating psychiatrist extracted all relevant information from the electronic medical record and handwritten progress notes to prepare the present account.

Case 1

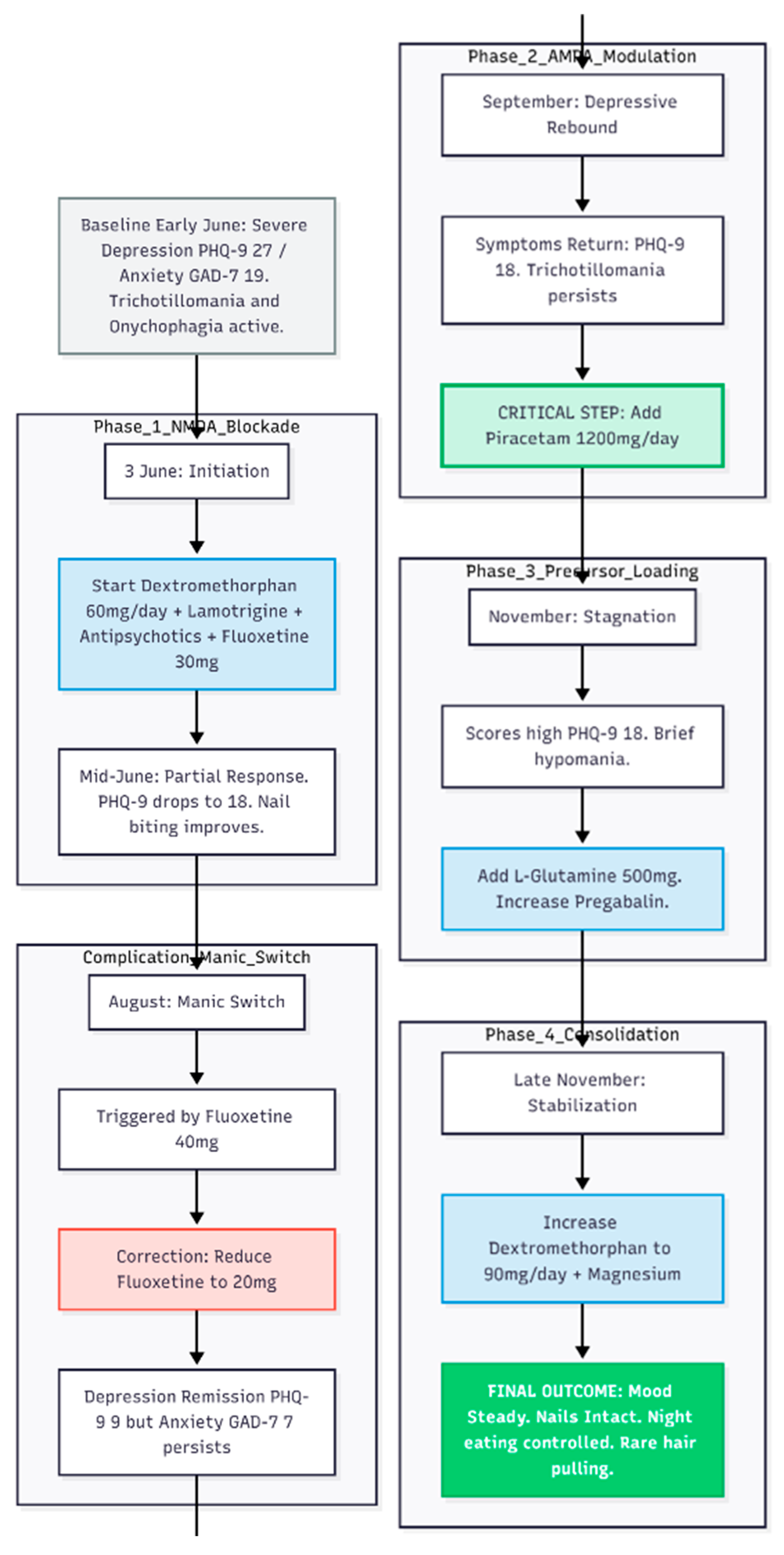

A 24-year-old woman with long-standing bipolar disorder and obsessive–compulsive features, chiefly trichotillomania (hair pulling) and onychophagia (nail biting), came to the clinic in early June 2025 (

Figure 1). Past treatment elsewhere had included fluoxetine, quetiapine, lamotrigine, aripiprazole and intermittent oxazepam, yet she still cycled between agitated highs—marked by pressured speech and occasional aggression—and deep lows. On arrival she was in a depressive episode; the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scored 27 and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scored 19. She slept fitfully, woke at night to raid the fridge and doubted her ability to keep her job.

First Therapeutic Step: 3 June 2025

Management began with the Cheung glutamatergic protocol. Dextromethorphan (DXM) 30 mg twice daily was started as the NMDA-receptor antagonist backbone. Lamotrigine 50 mg twice daily was added for mood stabilisation, together with quetiapine 25 mg nightly, aripiprazole 5 mg each morning and risperidone 0.5 mg at night to contain psychotic agitation. Fluoxetine was titrated to 30 mg each morning. For sleep and nocturnal anxiety she received lemborexant (Dayvigo) 2.5 mg at bedtime and a half-milligram of zolpidem if required.

Early Response and Dose Titration: Mid-June

Two weeks later the PHQ-9 had fallen to 18. Nail biting was clearly better, though hair pulling continued. Lamotrigine was doubled to 100 mg twice daily and fluoxetine to 40 mg daily (20 mg twice daily); DXM remained at 30 mg twice daily.

Additional Anxiolysis: July

Night eating and residual anxiety persisted. Pregabalin 50 mg nightly was introduced for sleep optimization.

Manic Switch: Early August

After one week of elevated mood the patient returned on 9 August. Fluoxetine was cut back to 10 mg twice daily (total 20 mg). Depression was now in remission (PHQ-9 = 9) but some anxiety lingered (GAD-7 = 7).

Depressive Rebound and Full Glutamatergic Stack: September

By early September low mood had crept in again (PHQ-9 = 18) and trichotillomania persisted. On 6 September piracetam 600 mg twice daily was added to provide AMPA-receptor modulation, completing the core DXM–piracetam pairing.

Fine-Tuning: October

Insomnia led to the introduction of lorazepam 0.5 mg nightly on 4 October. Other medicines were unchanged.

Precursor Loading and Further Adjustment: November

Though the patient said she felt “better,” scores remained high (PHQ-9 = 18, GAD-7 = 18) and a brief hypomanic spell was recorded. On 1 November L-glutamine 500 mg each morning was started to support glutamate–GABA cycling, and pregabalin was raised to 75 mg nightly.

Consolidation and High-Dose DXM: Late November

By the end of the month she described only occasional hair pulling, no significant overspending and night-eating urges that no longer led to food intake. On 29 November DXM was increased to 45 mg twice daily (total 90 mg) to cement stability, and magnesium 400 mg daily was added for general support.

Status at 29 November 2025: Mood steady; no depressive or manic symptoms; Minimal OCD behaviour: rare hair pulling, nails intact; Night eating limited to thoughts, not actions ; Sleeping through most nights.

Current Medication

Dextromethorphan 45 mg twice daily (90 mg/day)

Piracetam 600 mg twice daily (1 200 mg/day)

L-glutamine 500 mg nightly

Lamotrigine 100 mg twice daily (200 mg/day)

Fluoxetine 10 mg twice daily (20 mg/day)

Pregabalin 75 mg nightly

Quetiapine 25 mg nightly, aripiprazole 5 mg each morning, risperidone 0.5 mg nightly

Magnesium 400 mg nightly

Lemborexant 2.5 mg and zolpidem 0.5 mg at bedtime as needed

Lorazepam 0.5 mg nightly

Outcome

Sequential layering of NMDA blockade (DXM), AMPA modulation (piracetam) and a glutamine precursor, backed by conventional mood stabilisers and low-dose antipsychotics, produced a durable response where previous regimens had fallen short. Three months after initiation the patient was working, sleeping, and coping with only minor residual compulsive urges.

Case 2

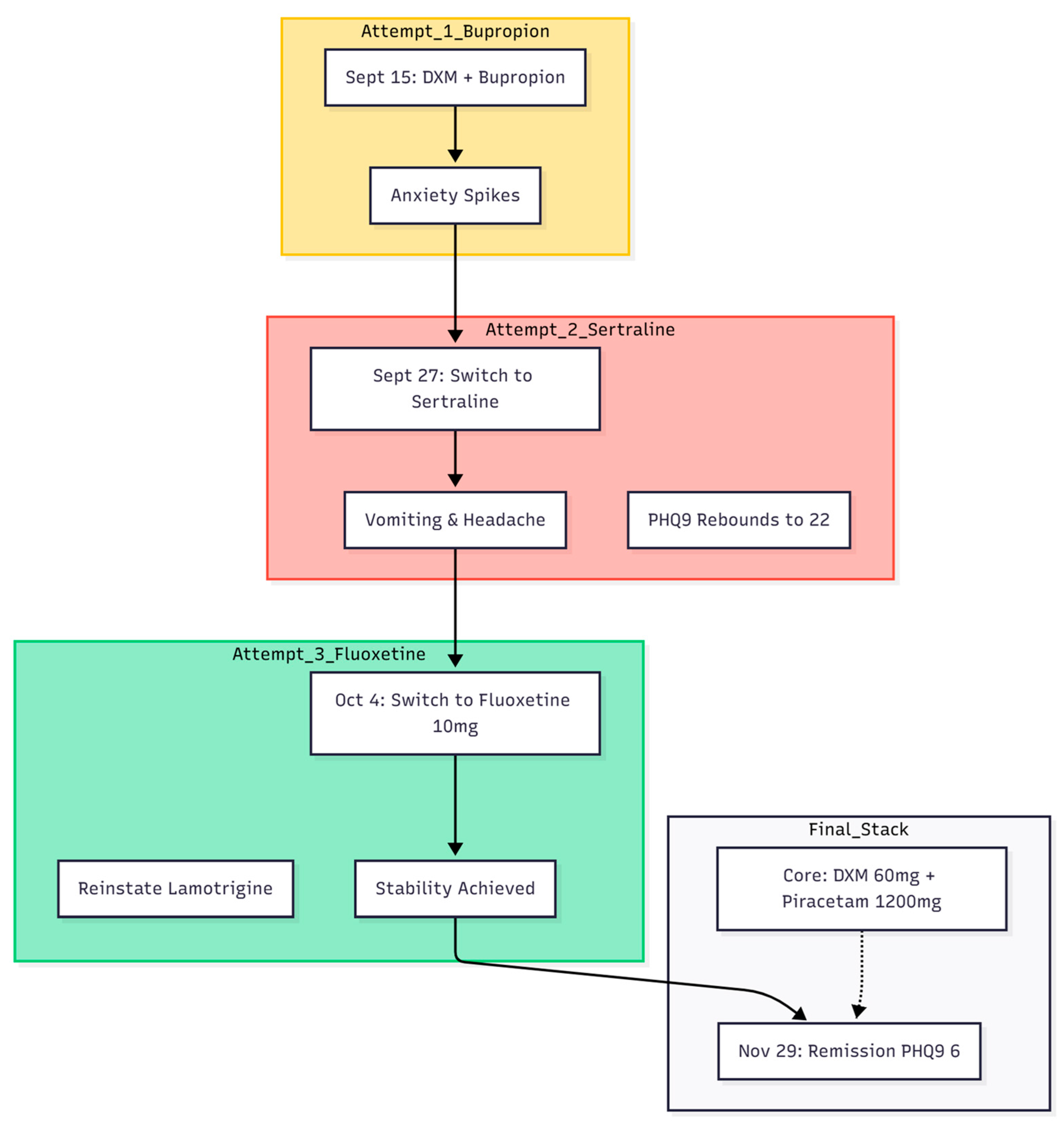

A 31-year-old woman with an eight-year history of bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder attended the clinic in mid-September 2025 (

Figure 2). Her chief complaints were intense anxiety, depressive mood, and intrusive somatic ideas—she was convinced that her bladder never emptied and visited the washroom repeatedly. Impulsivity had recently taken the form of buying large numbers of dolls and enrolling in multiple on-line courses. Earlier treatment elsewhere had included lamotrigine 150 mg, brexpiprazole, and clonazepam, yet she continued to experience dizziness at work, unprovoked crying spells, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Baseline scores were PHQ-9 = 21 and GAD-7 = 19.

First Therapeutic Attempt (15 September 2025)

The Cheung glutamatergic protocol was started. Dextromethorphan (DXM) 30 mg/day and piracetam 600 mg/day were prescribed, together with bupropion XL 150 mg and lemborexant (Dayvigo) 2.5 mg for sleep.

Early Adjustment and Glutamine Add-On (27 September 2025)

Although her PHQ-9 fell to 13, she attributed a rise in anxiety to bupropion. Bupropion was replaced by sertraline 25 mg. To reinforce glutamatergic balance, L-glutamine 1 g/day and a GABA supplement 500 mg/day (with vitamin B6) were added. DXM was increased to 45 mg/day.

Switch to Fluoxetine and Further Titration (4 October 2025)

Headache, vomiting, and return of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 = 22) led to withdrawal of sertraline. Fluoxetine 10 mg/day was introduced as a stronger CYP2D6 inhibitor; lamotrigine was reinstated at 150 mg; brexpiprazole 0.5 mg/day was continued. Zolpidem 15 mg and clonazepam 0.5 mg were given as needed for acute distress.

Optimising the Glutamatergic Stack (18 October 2025)

DXM was raised to 60 mg/day (30 mg twice daily) and piracetam to 1 200 mg/day (600 mg twice daily) for fluctuating OC symptoms.

Consolidation Phase (1 November 2025)

New stresses (The start of practicum) led to persisting anxiety and OC symptoms. Palpitations and continuing bladder anxiety prompted the addition of propranolol 20 mg/day. The core regimen—DXM 60 mg, piracetam 1 200 mg, and L-glutamine 1 g—was otherwise unchanged.

Outcome (29 November 2025)

By the end of November the patient met remission thresholds: PHQ-9 = 6, GAD-7 = 6. She no longer feared urinary retention, managed a work trip to Japan without incident, and reported steady mood, absence of crying spells, relief from headaches, and normal gastrointestinal function.

Current Medication List

Dextromethorphan 30 mg twice daily

Piracetam 600 mg twice daily

L-Glutamine 1 000 mg nocte

Fluoxetine 10 mg nocte

Lamotrigine 150 mg nocte

Brexpiprazole 0.5 mg nocte

GABA 500 mg nocte

Propranolol, zolpidem, and Dayvigo as required

This course illustrates how combined NMDA antagonism (dextromethorphan), AMPA facilitation (piracetam), and precursor support (glutamine) can relieve refractory bipolar depression with somatic OCD features when conventional serotonergic and dopaminergic approaches have failed.

Case 3

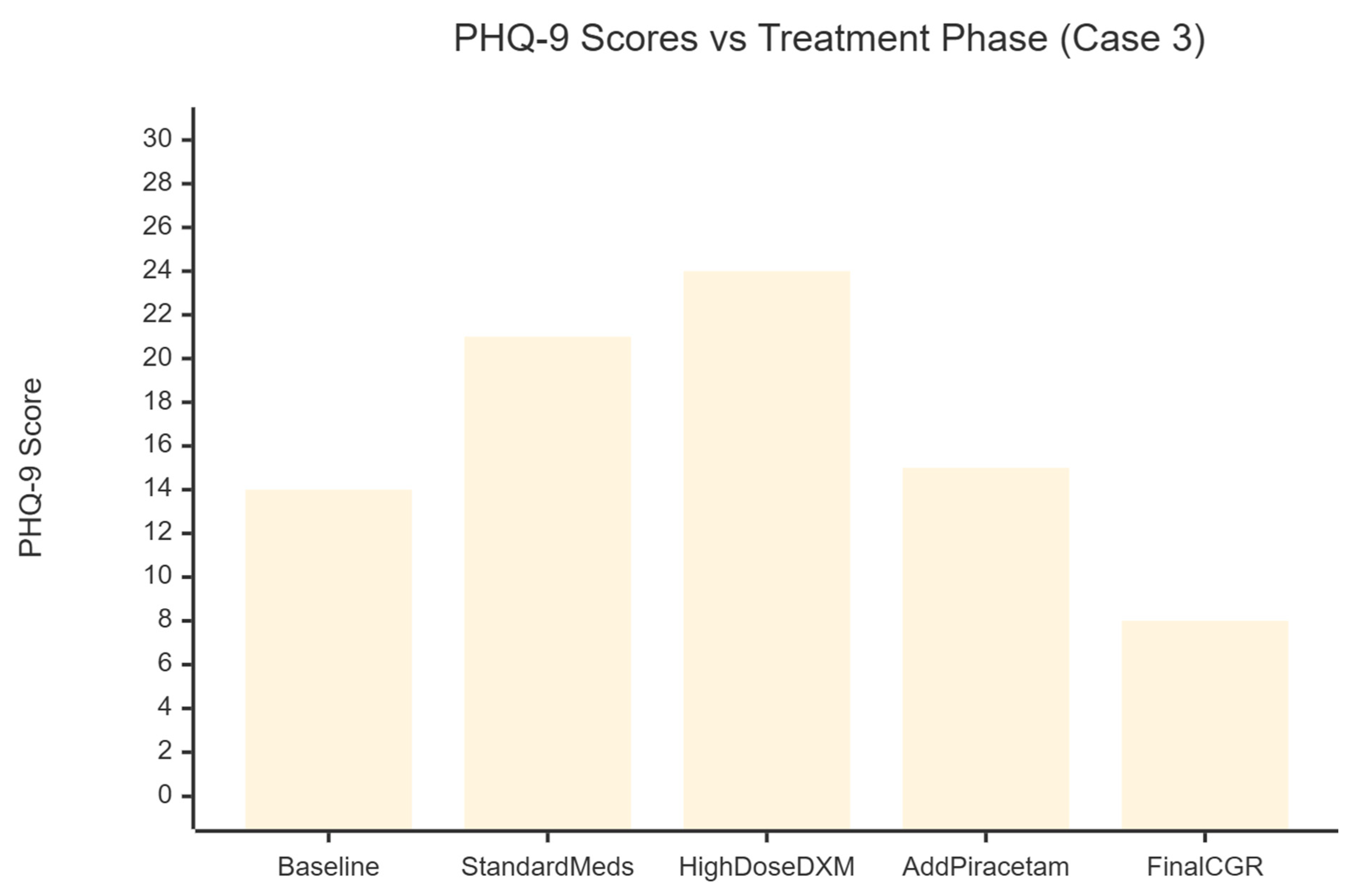

A 46-year-old man with a long--standing diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obsessive–compulsive disorder sought care in May 2025 for worsening mood, anxiety and insomnia (

Figure 3). His history included clear-cut hypomanic spells—irritability, pressured speech, impulsive spending and even blocking police vehicles while driving—and depressive episodes marked by profound anhedonia and hours of pre-sleep rumination. Several antidepressant trials given by psychiatrists before, yet offered little relief; paroxetine and dothiepin failed outright, while desvenlafaxine aggravated his insomnia.

Conventional Treatment and Early Deterioration (May–June 2025)

At presentation his Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score was 14 and his Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) score 15, consistent with moderate symptom burden. He began sodium valproate 500 mg nightly, paroxetine CR 12.5 mg, risperidone 0.5 mg, lorazepam 1 mg and one tablet of Deanxit (flupentixol + melitracen) daily. Within four weeks mood and anxiety had worsened (PHQ-9 = 21, GAD-7 = 17). Pregabalin 50 mg, clonazepam 0.5 mg and olanzapine 0.5 mg were added, but irritability persisted and compulsive arranging of household furniture emerged.

Shift to a Glutamatergic Strategy (Late June 2025)

Given the poor response to serotonergic and dopaminergic agents, therapy was redirected toward the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen. Paroxetine was tapered and replaced by fluoxetine 10 mg; lamotrigine 50 mg was introduced. Dextromethorphan 30 mg daily (15 mg ×2) was started while Deanxit was retained.

Dose Escalation (July–August 2025)

Anxiety remained troublesome, so dextromethorphan was raised to 45 mg daily and fluoxetine to 20 mg. By late August the patient presented in a severe depressive state (PHQ-9 = 23) accompanied by somatic delusions; dextromethorphan was increased to 90 mg daily (15 mg ×3, twice-daily dosing) and olanzapine to 5 mg to calm agitation.

Addition of AMPA Modulation (September 2025)

Despite high-dose NMDA antagonism the PHQ-9 climbed to 24 in mid-September. Piracetam, an AMPA positive allosteric modulator, was therefore added at 600 mg twice daily (total 1 200 mg). Simultaneously, dextromethorphan reached 120 mg daily (15 mg ×4, twice daily).

Optimisation and Remission (October–November 2025)

Residual low mood prompted an increase of fluoxetine to 20 mg BD. The core glutamatergic stack—dextromethorphan 60 mg BD, piracetam 600 mg BD and Deanxit—was held steady. Over the next six weeks depressive and obsessive symptoms receded. By November the PHQ-9 had fallen to 8 and the GAD-7 to 9; crying spells stopped, somatic complaints eased and sleep normalised. Clonazepam was discontinued. The maintenance regimen consisted of dextromethorphan 60 mg twice daily, piracetam 600 mg twice daily, one tablet of Deanxit daily for CYP2D6 inhibition, fluoxetine 20 mg twice daily and pregabalin 100–150 mg in divided doses for residual anxiety.

This course highlights the value of combining high-dose dextromethorphan with piracetam to create a robust NMDA-AMPA glutamatergic profile. In a patient whose bipolar depression with OCD features had resisted conventional polypharmacy, the strategy produced sustained remission and functional recovery within five months.

Conclusion

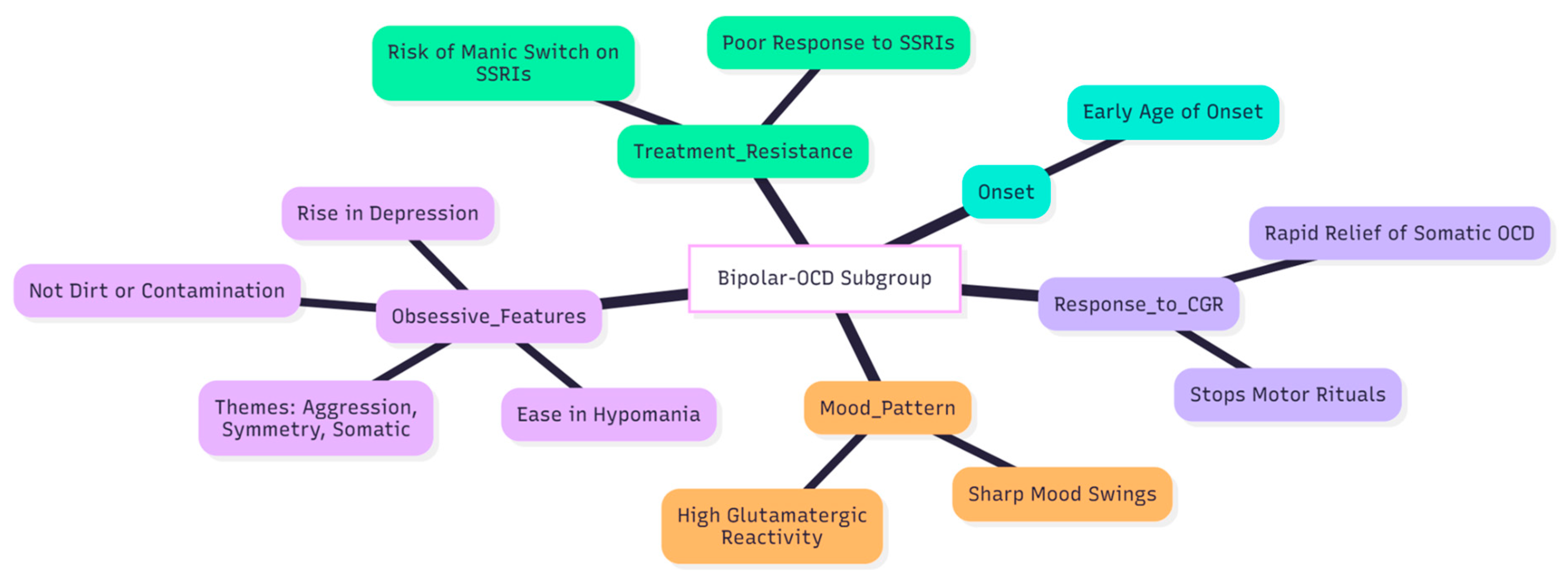

The experience with the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen in this and two earlier patients points to a practical way of helping the hard-to-treat “bipolar-OCD” subgroup (

Figure 4). People in this cluster usually fall ill early, swing sharply between mood poles, and carry obsessive worries that rise in depression and ease in hypomania; they also tend to do poorly on standard serotonin-based treatment (3,5,7,6). In every case, stepwise use of dextromethorphan, then piracetam, and, when needed, L-glutamine brought clear and lasting relief from low mood, intrusive thoughts, and compulsive acts that had resisted earlier drug trials (8).

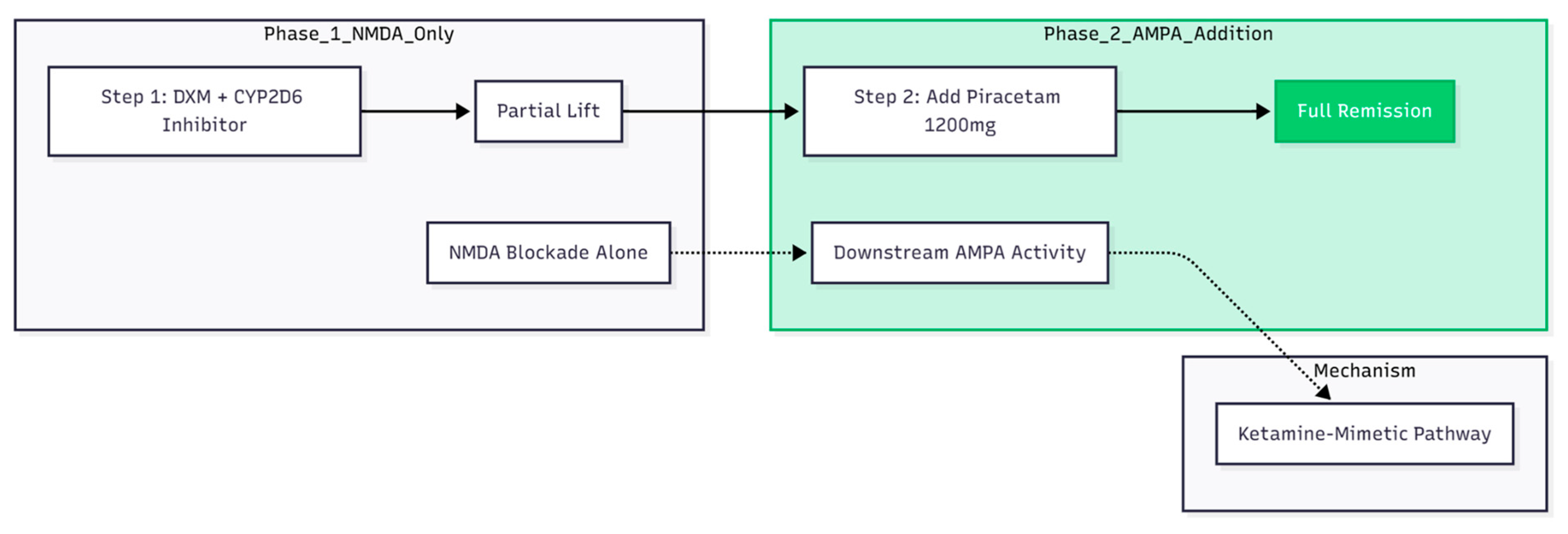

A repeated pattern emerged (

Figure 5). Dextromethorphan on its own—its blood level boosted by CYP2D6 inhibition—produced only a partial lift. Full remission appeared only after piracetam was introduced, echoing animal and human data that the maintained benefit of ketamine-like agents relies more on downstream AMPA activity than on NMDA blockade alone (14,15). Cheung’s other series reports the same “second-step” effect: once piracetam is pushed to 1 200 mg/day, patchy gains often settle into steady wellness (9,11,12).

All three patients met classic bipolar-OCD criteria: mood-linked obsessions, themes centred on aggression, symmetry, or bodily states rather than dirt, and either no response or frank worsening on high-dose SSRIs (7). The quick disappearance of bodily obsessions—such as the urethral retention fear highlighted in the second case—and of motor rituals such as hair and nail picking fits newer reports that NMDA-AMPA modulation can calm somatic and mood-congruent OCD symptoms in particular (11,8).

Drug-interaction management mattered. Strong, long-acting CYP2D6 blockers like fluoxetine and paroxetine raise serum dextromethorphan cheaply but can also push a bipolar patient into hypomania, as happened early in our first case (10). Cutting fluoxetine to 10–20 mg or replacing it with a shorter-acting inhibitor preserved the kinetic benefit while limiting drive and agitation, illustrating the need for reversible inhibitors in this setting (10). With adequate blockade, daily dextromethorphan rarely had to exceed 60–120 mg, keeping both cost and side-effects far below those of intravenous ketamine or intranasal esketamine.

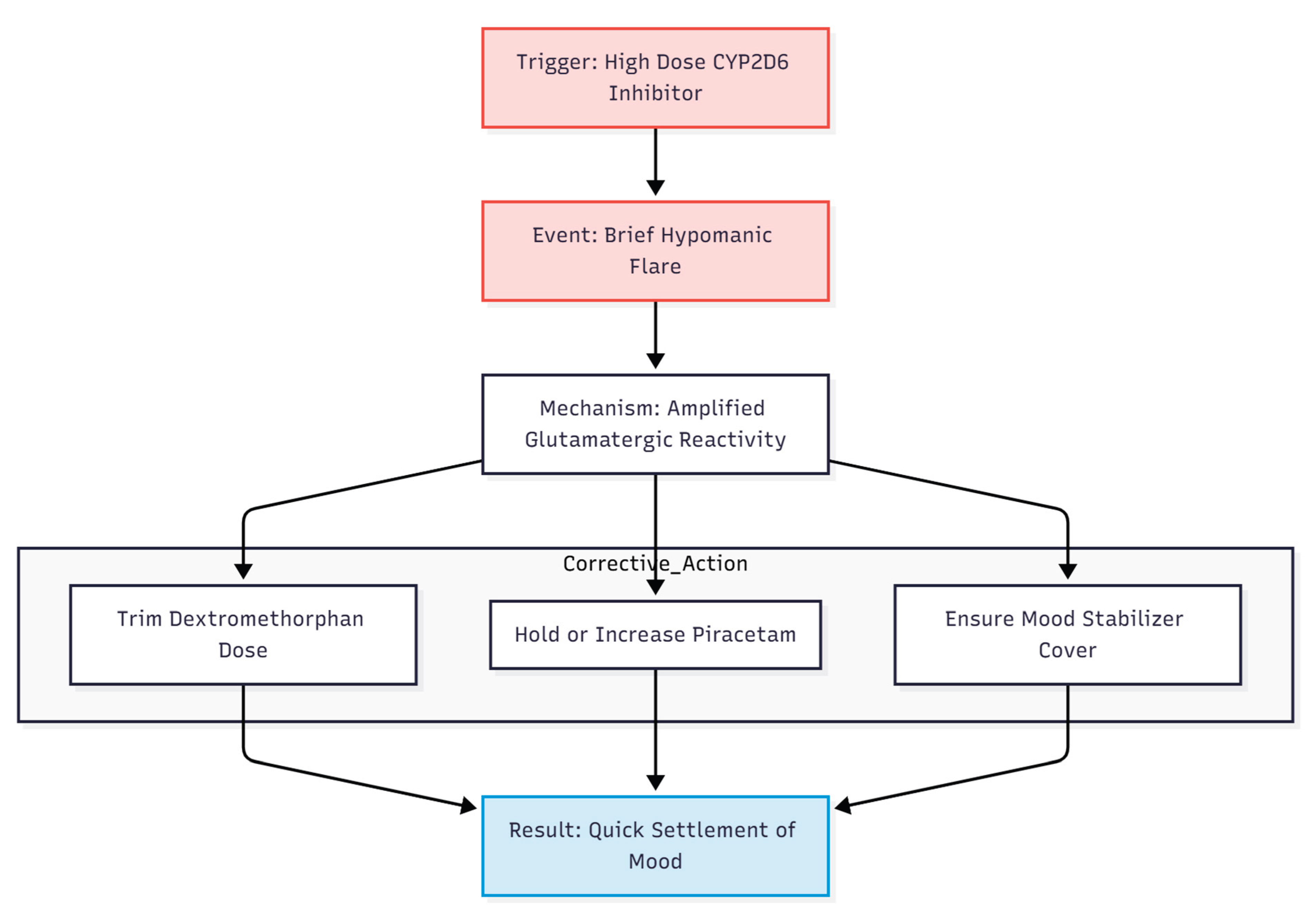

Brief hypomanic flares—seen here and reported by Cheung in other series—probably reflect the amplified glutamatergic reactivity of bipolar cortex (7). They settled quickly when the dextromethorphan dose was trimmed while piracetam was held or even increased, a tactic Cheung repeatedly recommends (9,10). Reliable mood-stabiliser cover with lamotrigine, valproate, or low-dose atypical antipsychotics remains essential, in line with current guidance for bipolar-OCD (13) (

Figure 6).

Taken together, these observations extend earlier anecdotes: a completely oral NMDA–AMPA strategy can deliver ketamine-level speed and depth of response in patients who combine bipolar disorder with OCD traits (9,11,8,12). In this niche population, it may outperform the usual practice of ever-higher SSRI doses, sparing patients the well-documented risk of manic switch on serotonergic monotherapy (7). The next step is clear: well-designed randomised trials must test how far these promising single-clinician findings can be generalised, and must map the safest dosing range for long-term use of this low-cost, ketamine-mimetic approach.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

References

- Berman, RM; Cappiello, A; Anand, A; et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry 2000, 47(4), 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarate, CA, Jr.; Brutsche, NE; Ibrahim, L; et al. Replication of ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: A randomized controlled add-on trial. Biological Psychiatry 2012, 71(11), 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerio, A; Stubbs, B; Odone, A; et al. The prevalence and predictors of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015, 186, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerio, A; Stubbs, B; Odone, A; et al. Bipolar I and II disorders; a systematic review and meta-analysis on differences in comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 10(3), e3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferentinos, P; Preti, A; Veroniki, AA; et al. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar spectrum disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 263, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Prisco, M; Tapoi, C; Oliva, V; et al. Clinical features in co-occuring obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 80, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filippis, R; Aguglia, A; Costanza, A; et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder as an epiphenomenon of comorbid bipolar disorder? An updated systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13(5), 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. An oral “ketamine-like” NMDA/AMPA modulation stack restores cognitive capacity in a young man with schizoaffective disorder—Case report. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Clinical experience and optimisation of the Cheung glutamatergic regimen for refractory psychiatric diseases. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, N. Oral glutamatergic augmentation for trauma-related disorders with fluoxetine-/bupropion-potentiated dextromethorphan ± piracetam: A four-patient case series. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Amerio, A; Costanza, A; Aguglia, A. Differentiating comorbid bipolar disorder and OCD. Psychiatric Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/differentiating-comorbid-bipolar-disorder-and-ocd.

- Maeng, S; Zarate, CA, Jr.; Du, J; et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of AMPA receptors. Biological Psychiatry 2008, 63(4), 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, P; Moaddel, R; Morris, PJ; et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016, 533(7604), 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).