Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

Ethical Approval

Sampling Strategy and Recruitment

Survey Instruments

- The Patient Action Inventory for Self-Care: this is a validated tool assessing 57 self-care behaviors across 11 domains (e.g., medication use, physical activity, emotional regulation) using dichotomous (yes/no) responses. It measures perceived importance, willingness, and ability to perform each behavior. This tool has demonstrated strong reliability and construct validity in older adult populations [25,26].

- A tailored health assessment questionnaire: adapted from a similar study conducted in the U.S. and modified for Saskatchewan’s healthcare context [27,28]. This instrument captured participant demographics (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, education level, first three digits of postal code, immigration status), as well as health indicators including self-rated health, access to care, healthcare service utilization, transportation availability, and presence of chronic conditions.

Key Variables and Outcome Measures

Data Analysis

Results

Sample Characteristics

Prevalence and Patterning of Multimorbidity

Quality of Life and Self-Perceived Health

Access to Care and Unmet Needs

Acute Care Utilization

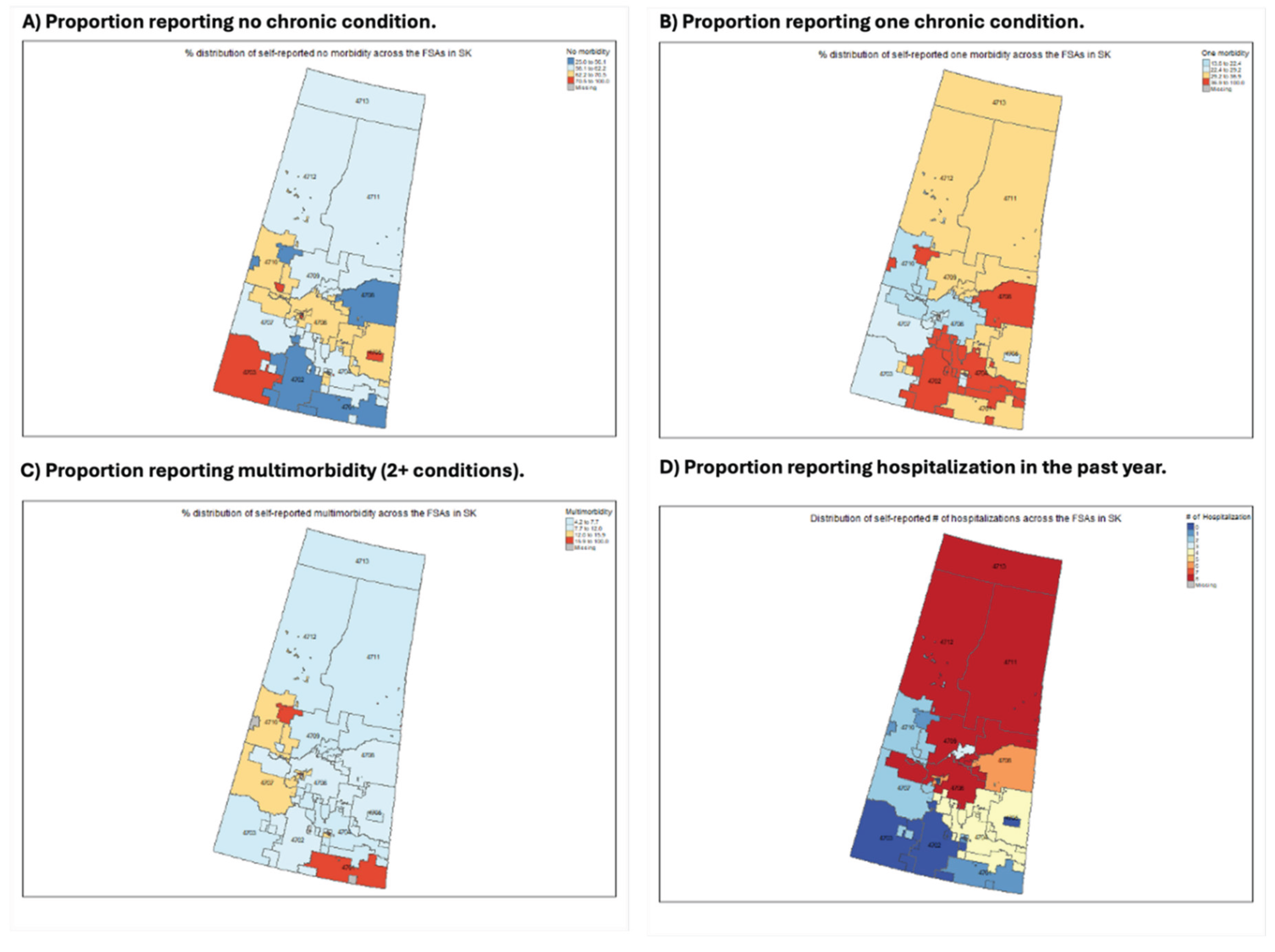

Geographic Variation in Multimorbidity

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Future Directions and Implications

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Seniors and aging dashboard. 2025. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/dashboards/seniors-and-aging.

- Fortin, M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: a closer look. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K. The co-occurrence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy among middle-aged and older adults in Canada: A cross-sectional study using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) and the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN). PLoS One 2025, 20, e0312873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geda, N.R.; Janzen, B.; Pahwa, P. Chronic disease multimorbidity among the Canadian population: prevalence and associated lifestyle factors. Arch Public Health 2021, 79, 60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnston, M.C. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur J Public Health 2019, 29, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, L.E. Multimorbidity Frameworks Impact Prevalence and Relationships with Patient-Important Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019, 67, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Mortey, O. Prevalence and risk factors of the most common multimorbidity among Canadian adults. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0317688. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Stranges, S.; Sarma, S. Investigation of rural-urban differences in hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions: Analysis of linked survey, hospitalization, and tax data from Canada. J Rural Health 2025, 41, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugravot, A. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: a 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e42–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, L.M.; Weiner, J.P. An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2011, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, K.J.; Wen, H. K.E. Joynt Maddox, Lack Of Access To Specialists Associated With Mortality And Preventable Hospitalizations Of Rural Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019, 38, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, E. Household and area-level social determinants of multimorbidity: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021, 75, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. The impact of place on multimorbidity: A systematic scoping review. Soc Sci Med 2024, 361, 117379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Beach, J.; Senthilselvan, A. Prevalence and determinants of multimorbidity in the Canadian population. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0297221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kone, A.P. Rising burden of multimorbidity and related socio-demographic factors: a repeated cross-sectional study of Ontarians. Can J Public Health 2021, 112, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.L. Beyond the grey tsunami: a cross-sectional population-based study of multimorbidity in Ontario. Can J Public Health 2018, 109, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, P. Geographic variation in preventable hospitalisations across Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. Lancet 2018, 391, 1718–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A. Effect of socio-demographic and health factors on the association between multimorbidity and acute care service use: population-based survey linked to health administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res 2021, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, B. Exploring diversity in socioeconomic inequalities in health among rural dwelling Canadians. J Rural Health 2015, 31, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.; Ryan, B. Ecology of health care in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2015, 61, 449–453. [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo, R. Association between physical activity and life satisfaction among adults with multimorbidity in Canada. Can J Public Health 2022, 113, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josewski, V.; de Leeuw, S.; Greenwood, M. Grounding Wellness: Coloniality, Placeism, Land, and a Critique of “Social” Determinants of Indigenous Mental Health in the Canadian Context. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Arcy, C. D. Physical activity and social support mediate the relationship between chronic diseases and positive mental health in a national sample of community-dwelling Canadians 65+: A structural equation analysis. J Affect Disord 2022, 298, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.M.; Pierson, J. Marcus. Measuring patient engagement: which healthcare engagement behaviours are important to patients? J Adv Nurs 2017, 73, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.M.; Pierson, J.M. What are the highly important and desirable patient engagement actions for self-care as perceived by individuals living in the southern United States? Patient Prefer Adherence 2017, 11, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.M.; Okpalauwaekwe, U.; Yin, C.Y. Older adults’ suggestions to engage other older adults in health and healthcare: a qualitative study conducted in western Canada. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019, 13, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, H.M. Do patients’ demographic characteristics affect their perceptions of self-care actions to find safe and decent care? Appl Nurs Res 2018, 43, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.H.B. Examining the prevalence and correlates of multimorbidity among community-dwelling older adults: cross-sectional evidence from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) first-follow-up data. Age Ageing 2022, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K. Examining early and late onset of multimorbidity in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021, 69, 1579–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salive, M.E. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 2013, 35, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, J.K. Trends and inequalities in multimorbidity from 2001/2002 to 2019/2020: A population-based study in British Columbia. Health Rep 2025, 36, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ketter, N.I. Describing the Profile of Individuals at Heightened Risk for Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity: A Secondary Analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging Data. Am J Health Promot 2025, 8901171251374738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahunja, K.M. Multimorbidity among the Indigenous population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol 2024, 98, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpalauwaekwe, U. Enhancing health and wellness by, for and with Indigenous youth in Canada: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Stranges, S.; Le, B. Social and health determinants of wait times for primary care in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2025, 71, 646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, A.S. Preventing and managing multimorbidity by integrating behavioral health and primary care. Health Psychol 2019, 38, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.W.; Kuluski, K.; Im, J. “It’s a fight to get anything you need” - Accessing care in the community from the perspectives of people with multimorbidity. Health Expect 2017, 20, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpalauwaekwe, U. Facilitators, barriers, and priorities for enhancing primary care recruitment and retention in Saskatchewan, Canada. BMC Prim Care 2025, 26, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.I.; Milosavljevic, S.; Bath, B. Determining geographic accessibility of family physician and nurse practitioner services in relation to the distribution of seniors within two Canadian Prairie Provinces. Soc Sci Med 2017, 194, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S. Emergency department and inpatient utilization among U.S. older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a post-reform update. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M. Individual and contextual predictors of emergency department visits among community-living older adults: a register-based prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P. Association between multimorbidity and hospitalization in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.P. Multimorbidity patterns and hospitalisation occurrence in adults and older adults aged 50 years or over. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pong, R.W. Patterns of health services utilization in rural Canada. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2011, 31, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total (N = 1,093) | No Chronic Condition (N = 673) | 1 Chronic Condition (N = 304) | 2+ Chronic Conditions (N = 116) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65–74 | 642 (58.7%) | 409 (60.8%) | 163 (53.6%) | 70 (60.3%) |

| 75–84 | 345 (31.6%) | 201 (29.9%) | 107 (35.2%) | 37 (31.9%) |

| 85+ | 99 (9.1%) | 58 (8.6%) | 32 (10.5%) | 9 (7.8%) |

| Missing | 7 (0.6%) | 5 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 779 (71.3%) | 488 (72.5%) | 209 (68.8%) | 82 (70.7%) |

| Male | 314 (28.7%) | 185 (27.5%) | 95 (31.2%) | 34 (29.3%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 977 (89.4%) | 611 (90.8%) | 267 (87.8%) | 99 (85.3%) |

| Indigenous | 66 (6.0%) | 31 (4.6%) | 22 (7.2%) | 13 (11.2%) |

| Asian | 6 (0.5%) | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Black | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 43 (3.9%) | 27 (4.0%) | 13 (4.3%) | 3 (2.6%) |

| Highest Education Completed | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 329 (30.1%) | 229 (34.0%) | 75 (24.7%) | 25 (21.6%) |

| Associate/diploma | 251 (23.0%) | 150 (22.3%) | 69 (22.7%) | 32 (27.6%) |

| High school | 308 (28.2%) | 172 (25.6%) | 95 (31.2%) | 41 (35.3%) |

| Some education | 124 (11.3%) | 74 (11.0%) | 37 (12.2%) | 13 (11.2%) |

| Other | 69 (6.3%) | 38 (5.6%) | 26 (8.6%) | 5 (4.3%) |

| Missing | 12 (1.1%) | 10 (1.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Language | ||||

| English as first language | 950 (86.9%) | 586 (87.1%) | 261 (85.9%) | 103 (88.8%) |

| Not English | 139 (12.7%) | 83 (12.3%) | 43 (14.1%) | 13 (11.2%) |

| Missing | 4 (0.4%) | 4 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Chronic Condition | Total (N = 1,093) | No Chronic Condition (N = 673) | 1 Chronic Condition (N = 304) | 2+ Chronic Conditions (N = 116) |

| Asthma | 90 (8.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 52 (17.1%) | 38 (32.8%) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 51 (4.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (4.3%) | 38 (32.8%) |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | 77 (7.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (8.9%) | 50 (43.1%) |

| Depression | 145 (13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 56 (18.4%) | 89 (76.7%) |

| Diabetes | 102 (9.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (12.8%) | 63 (54.3%) |

| Heart Failure | 38 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.3%) | 34 (29.3%) |

| Variable | Total (N = 1,093) | No Chronic Condition (N = 673) | 1 Chronic Condition (N = 304) | 2+ Chronic Conditions (N = 116) |

| Access to healthcare when needed | ||||

| Yes (all services) | 572 (52.3%) | 367 (54.5%) | 151 (49.7%) | 54 (46.6%) |

| Yes (some services) | 410 (37.5%) | 242 (36.0%) | 123 (40.5%) | 45 (38.8%) |

| No | 64 (5.9%) | 39 (5.8%) | 16 (5.3%) | 9 (7.8%) |

| Missing | 47 (4.3%) | 25 (3.7%) | 14 (4.6%) | 8 (6.9%) |

| Transportation available when needed | ||||

| Yes | 1,050 (96.1%) | 645 (95.8%) | 294 (96.7%) | 111 (95.7%) |

| No | 32 (2.9%) | 19 (2.8%) | 9 (3.0%) | 4 (3.4%) |

| Missing | 11 (1.0%) | 9 (1.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Able to meet healthcare needs (past 3 months) | ||||

| Yes | 1,030 (94.2%) | 641 (95.2%) | 285 (93.8%) | 104 (89.7%) |

| No | 56 (5.1%) | 26 (3.9%) | 18 (5.9%) | 12 (10.3%) |

| Missing | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Quality of life (self-rated) | ||||

| Satisfied | 1,050 (96.1%) | 645 (95.8%) | 294 (96.7%) | 111 (95.7%) |

| Not satisfied | 32 (2.9%) | 19 (2.8%) | 9 (3.0%) | 4 (3.4%) |

| Missing | 11 (1.0%) | 9 (1.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Satisfaction with physical health | ||||

| Satisfied | 972 (88.9%) | 622 (92.4%) | 259 (85.2%) | 91 (78.4%) |

| Not satisfied | 105 (9.6%) | 43 (6.4%) | 37 (12.2%) | 25 (21.6%) |

| Missing | 16 (1.5%) | 8 (1.2%) | 8 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Satisfaction with mental health | ||||

| Satisfied | 838 (76.7%) | 563 (83.7%) | 209 (68.8%) | 66 (56.9%) |

| Not satisfied | 238 (21.8%) | 100 (14.9%) | 90 (29.6%) | 48 (41.4%) |

| Missing | 17 (1.6%) | 10 (1.5%) | 5 (1.6%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Satisfaction with emotional health | ||||

| Satisfied | 1,010 (92.4%) | 639 (94.9%) | 275 (90.5%) | 96 (82.8%) |

| Not satisfied | 68 (6.2%) | 24 (3.6%) | 25 (8.2%) | 19 (16.4%) |

| Missing | 15 (1.4%) | 10 (1.5%) | 4 (1.3%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Satisfaction with spiritual health | ||||

| Satisfied | 989 (90.5%) | 625 (92.9%) | 266 (87.5%) | 98 (84.5%) |

| Not satisfied | 83 (7.6%) | 33 (4.9%) | 34 (11.2%) | 16 (13.8%) |

| Missing | 21 (1.9%) | 15 (2.2%) | 4 (1.3%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Variable | Total (N = 1,093) | No Chronic Condition (N = 673) | 1 Chronic Condition (N = 304) | 2+ Chronic Conditions (N = 116) |

| Emergency Room Visit (past 3 months) | ||||

| Yes | 116 (10.6%) | 51 (7.6%) | 41 (13.5%) | 24 (20.7%) |

| No | 974 (89.1%) | 619 (92.0%) | 263 (86.5%) | 92 (79.3%) |

| Missing | 3 (0.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hospitalization (past 3 months) | ||||

| Yes | 67 (6.1%) | 27 (4.0%) | 26 (8.6%) | 14 (12.1%) |

| No | 1,023 (93.6%) | 643 (95.5%) | 278 (91.4%) | 102 (87.9%) |

| Missing | 3 (0.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unmet Healthcare Needs (past 3 months) | ||||

| Yes | 56 (5.1%) | 26 (3.9%) | 18 (5.9%) | 12 (10.3%) |

| No | 1,030 (94.2%) | 641 (95.2%) | 285 (93.8%) | 104 (89.7%) |

| Missing | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).