1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is widely recognized as one of the most successful orthopedic procedures, capable of providing substantial pain relief and significant functional improvement for individuals with advanced hip osteoarthritis [

1,

2]. However, favorable clinical scores and satisfactory radiographic findings do not necessarily imply full recovery of neuromuscular control [

3].

Many patients already exhibit degenerative alterations of the periarticular muscles and tendons before surgery, arising from prolonged disuse, compensatory movement patterns, and disease-related degenerative processes [

4,

5]. Furthermore, the surgical procedure itself may introduce additional neuromuscular modifications due to tissue trauma, periarticular muscle dissection, altered joint mechanics, and potential vascular injury [

6,

7]. Additional risks include traction, irritation, or partial injury of periarticular nerves [

8,

9,

10], with incidence varying according to the surgical approach employed [

11]. Taking together, these factors may lead to long-lasting deviations in neuromuscular activation patterns, even when the implant is technically sound [

12].

Therefore, electromyography (EMG) has become a central tool for characterizing these alterations. EMG provides information that cannot be obtained through clinical examination, radiographic imaging, or kinematic analysis. Traditionally employed in neurophysiological assessments, needle EMG enables a detailed evaluation of motor unit integrity and allows the detection of denervation or reinnervation phenomena [

13]. Early investigations using this technique, conducted during the initial postoperative phase, revealed impaired voluntary activation and reduced recruitment capacity of the hip abductors [

14,

15]. Subsequently, the use of surface EMG made it possible to noninvasively quantify activation timing, signal amplitude, and intermuscular coordination during functional tasks [

16].

These analyses showed that abnormalities in muscle activity—often still present several months after surgery—involve not only the abductors but also other hip-related muscles during gait and load-bearing activities [

17,

18]. More recent developments, such as high-density surface electromyography (HD-sEMG) and other multimodal EMG-based analytical approaches, have demonstrated that postoperative neuromuscular reorganization extends beyond the hip region and involves coordinated adjustments along the entire limb and trunk [

19]. Notably, these non-physiological patterns can persist well beyond pain resolution and basic functional recovery and may remain detectable up to a year or more after surgery [

20]. The widening gap between biomechanical recovery and neuromuscular reorganization underscores a significant blind spot in current postoperative evaluation models.

Despite these insights, the nature, consistency, and clinical implications of reported EMG alterations remain difficult to interpret. A major source of uncertainty lies in the substantial methodological heterogeneity of available studies. Existing investigations range from treadmill and overground gait analysis to static load tests and diagnostic maneuvers such as the Trendelenburg test [

17,

21], and more recently have also included EMG assessments during standardized rehabilitation or mobilization exercises performed in lying, sitting, or standing positions [

19]. This diversity in motor tasks, experimental conditions, and measurement protocols makes it difficult to identify robust and reproducible neuromuscular patterns.

Such heterogeneity is further compounded by differences in electrode placement, filtering methods, and normalization strategies—including maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC), percentage of maximum voluntary contraction (%MVC), and root mean square (RMS) values—as well as variability in the muscles examined, postoperative time points, surgical approaches, and prosthesis types. A further limitation is that many investigations have focused primarily on individual muscles, typically the gluteus medius (GMED)—rather than examining the broader organization of motor control. As a result, intermuscular coordination, bilateral load distribution, and compensatory strategies influenced by contralateral pathology or previous arthroplasty remain only partially understood.

In this context, a systematic reappraisal of the EMG literature after THA is warranted. The main objectives of this review are to determine the extent to which postoperative EMG patterns resemble those of healthy individuals or preoperative conditions, to identify the most consistent neuromuscular alterations, and to explore how factors such as surgical approach, nerve integrity, and load management contribute to the persistence of dysfunction. Another aim is to translate this evidence into practical clinical recommendations and outline future research directions that may deepen our understanding of motor recovery after THA.

2. Materials and Methods.

2.1. Guidelines and Protocol

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

22]. The methodological protocol, including the search strategy, eligibility criteria, screening procedures, data extraction framework, and planned approach to synthesis, was defined as a priori and preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF; DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/DA5JT).

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL, IEEE Xplore, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Google Scholar (first 200 records). The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms related to THA, surface and needle EMG techniques, and both dynamic and static functional tasks. Search strings were adapted to the syntax and indexing structure of each database. No language restrictions were applied. The search was last updated in December 2025.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies were original peer-reviewed research involving adult participants undergoing primary or revision THA and reporting quantitative EMG analyses of hip or lower-limb muscles. Assessments could include dynamic locomotor tasks such as gait or stair ambulation, static or isometric contractions, Trendelenburg or load-modified conditions, or intraoperative neuromonitoring. Studies were required to report at least one interpretable EMG parameter, such as activation timing, amplitude (normalized or raw), motor unit characteristics, frequency-domain features, or advanced EMG descriptors. Studies were excluded if they used EMG solely for biofeedback, provided no analyzable EMG data, involved mixed populations without separable THA results, or consisted of non-original material such as conference abstracts, theses, or narrative reviews. In addition, studies employing needle EMG exclusively for intraoperative neuromonitoring—not for quantitative assessment of postoperative muscle activation—were excluded.

2.4. Screening Process

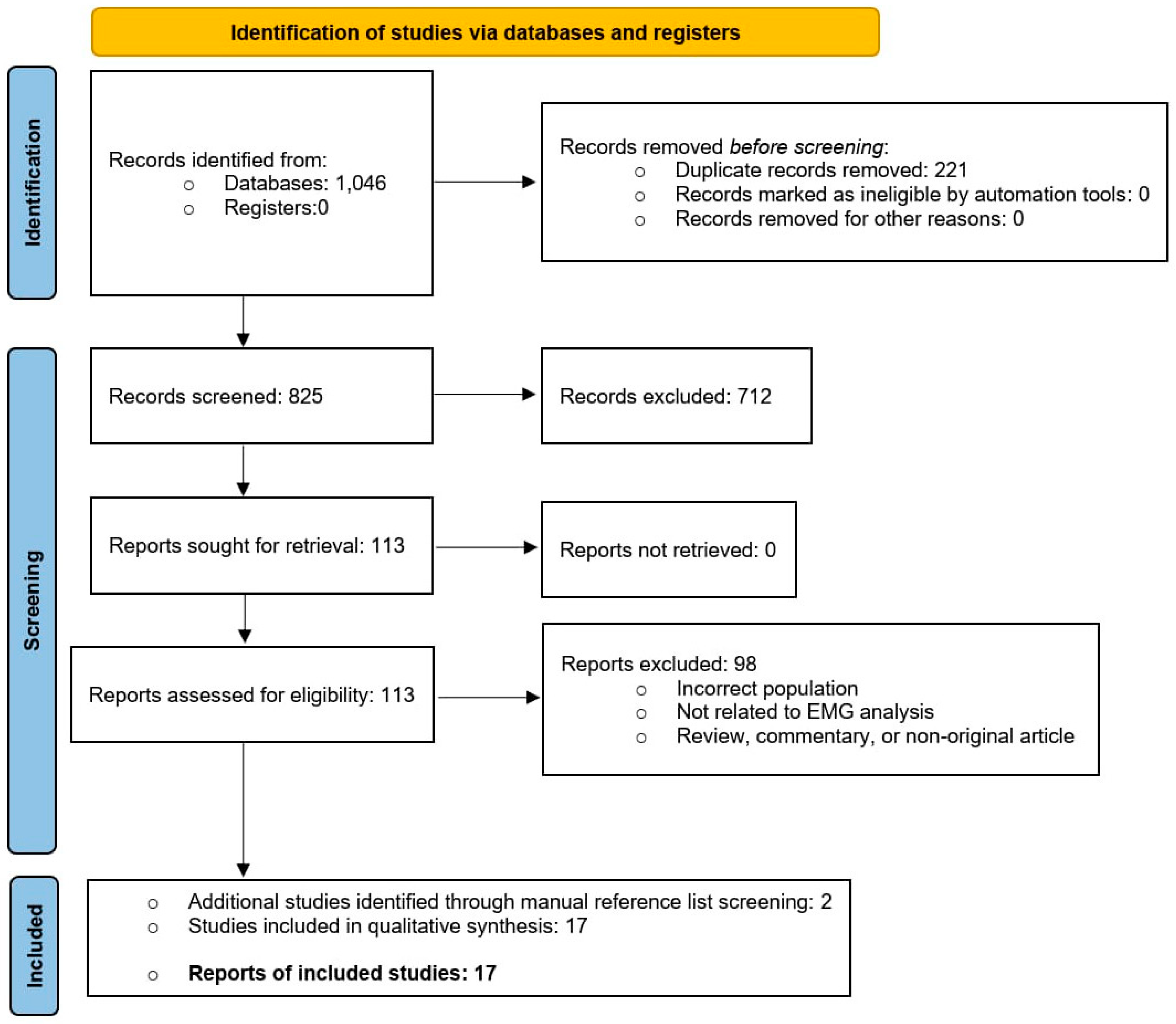

All records retrieved from the search were imported into a reference manager, duplicates were removed, and the remaining records were screened independently by two reviewers based on title and abstract. Full texts judged potentially eligible were then retrieved and assessed in detail according to the predefined criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. The flow of studies through the screening stages is reported in the Results section and illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. For each included study, we recorded the study design and sample characteristics, as well as the postoperative follow-up intervals considered. We also extracted information on the surgical approach adopted—classified as posterolateral, direct lateral, direct anterior, minimally invasive anterior, or other variants—and on the specific muscles examined, with particular attention to the GMED, gluteus maximus (GMAX), tensor fasciae latae (TFL), rectus femoris (RF), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST) and sartorius (S).

Details regarding the functional protocols were documented, including the type of task performed, walking speed, support conditions, and any load modifications. The EMG methodology was also collected, distinguishing between surface, needle, fine-wire, and multimodal neurophysiological monitoring techniques. Normalization procedures were recorded when available, such as the use of MVIC, %MVC, RMS normalization, or the absence of normalization.

Finally, for each study we extracted the analyzed EMG parameters—encompassing timing metrics, amplitude (normalized or raw), motor unit action potential (MUAP) characteristics, and frequency-domain features—and summarized the primary EMG-related results together with the authors’ main interpretations and conclusions.

2.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was evaluated using the relevant Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools [

23]. Particular attention was given to transparency and reproducibility of EMG acquisition, preprocessing, and normalization; robustness of timing detection methods; adherence to standards for needle or quantitative EMG; and clarity of statistical reporting. Quality assessments were performed independently by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. These appraisals informed the interpretation of findings but did not determine study inclusion.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 1,046 records were identified through database searching. After removal of 221 duplicates, 825 unique records underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 712 were excluded because they did not involve THA populations, did not include EMG outcomes, or adopted ineligible designs. The remaining 113 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility; none were excluded due to retrieval failure. Following full-text evaluation, 98 studies were excluded because they investigated non-THA samples, lacked analyzable EMG parameters, provided in-sufficient methodological detail, or were classified as non-original re-search (review, commentary, or technical note). A total of 15 studies met all inclusion criteria, and two additional eligible study were identified through manual reference screening, resulting in 17 studies included in the qualitative synthesis. The full selection process is presented in

Figure 1 (PRISMA Flow Diagram).

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

Methodological quality varied across the included studies, as summarized in

Table 1. Investigations focusing on activation timing, such as those by Agostini [

24], Vogt [

25], Horstmann [

17], and Ajemian [

26], generally provided clear descriptions of onset/offset detection and burst quantification, although not all incorporated amplitude normalization, limiting cross-study comparability. Studies employing MVIC-normalized amplitude, including Martinez [

27], Bernard [

18], Kopeć [

21], and Robbins [

28], demonstrated stronger methodological consistency, particularly in relation to electrode placement, preprocessing pipelines, and normalization strategies. Robbins’ integration of waveform principal component analysis represented one of the most analytically sophisticated approaches [

28].

Needle EMG and quantitative EMG investigations—particularly those by Baker & Bitounis [

15], Moreschini [

14], Chomiak [

11], and Khalifa [

29]—showed high technical rigor, supported by detailed reporting of motor-unit morphology, spontaneous activity, and recruitment characteristics. Advanced EMG descriptors used by Ippolito [

30] (full width at half maximum, FWHM) and Robbins [

28] (principal component analysis, PCA) added valuable analytical depth, though these methods were less widely adopted. HD-sEMG, as applied in Morsch et al. [

19], further expanded methodological sophistication by incorporating spatial activation mapping, spectral features, and coordination indices within a longitudinal framework.

Conversely, studies relying on raw, non-normalized amplitude or qualitative pattern description—such as Novo [

20]—showed good technical execution but lower evidence strength due to limited reproducibility and reduced comparability. The main sources of heterogeneity across studies were differences in normalization strategy, preprocessing detail, sampling consistency, and the complexity of the analytical frameworks.

Despite this variability, all included studies met the minimum standards required for EMG acquisition and reporting, allowing for their retention in the review and enabling structured synthesis across methodological subgroups.

3.3. Alterations in EMG Patterns During Gait After THA

Six studies [

17,

20,

24,

25,

27,

30] examined EMG activity during walking after THA. Follow-up intervals ranged from approximately six weeks to 12 months, with one long-term case assessed more than 10 years post-surgery [

20]. Despite differences in locomotor settings (overground vs treadmill, self-selected vs-controlled speed) and normalization methods (MVIC, standardized isometric contractions, or no normalization), all studies analyzed either timing parameters (onset, offset, burst duration) or normalized amplitude, and all reported deviations from physiological patterns.

GMED emerged as the most consistently altered muscle. According to studies, it showed delayed onset [

25], reduced pre-activation before heel strike [

24], and prolonged activation during stance [

20,

24]. These abnormalities were observed in both cross-sectional comparisons with healthy controls [

25,

27,

30] and longitudinal pre–post analyses [

17], indicating that the abductor complex fails to fully recover its anticipatory and stabilizing role during gait.

Posterior biarticular muscles, particularly BF and ST, displayed markedly sustained activity during late stance in both longitudinal [

17] and cross-sectional [

20] studies. This pattern suggests a compensatory use of the hamstrings as secondary stabilizers, potentially offsetting persistent abductor weakness or inefficient hip extension. Abnormalities were also reported in the flexors and lateral stabilizers, including RF, TFL, and sartorius, with patterns that varied according to surgical approach. In studies focusing on lateral or posterolateral approaches [

17,

24,

25], these muscles tended to exhibit prolonged bursts with delayed peaks, whereas in anterior approaches [

27,

30] the abnormalities were characterized more by reduced amplitude and less well-defined temporal profiles. Despite these differences, both patterns represent deviations from normal intermuscular coordination.

Overall, the available gait studies show that improvements in walking capacity and spatiotemporal parameters do not coincide with normalization of EMG patterns. Persistent delays in GMED activation, hamstring overactivity, and flexor inefficiencies suggest a non-physiological recovery trajectory extending beyond the first postoperative year. Full details are presented in

Table 2.

3.4. Surgical Approach and EMG Patterns

Four studies directly compared EMG outcomes across surgical approaches [

11,

14,

15,

28]. Two early investigations used needle EMG to assess postoperative denervation and voluntary recruitment [

14,

15], while Chomiak et al. [

11] expanded this approach to three surgical techniques, and Robbins et al. [

28] examined MVIC-normalized surface EMG during gait one year after THA.

In the early postoperative period, both Baker and Moreschini reported a higher incidence of denervation potentials in TFL and impaired voluntary recruitment of GMED after lateral-based approaches compared with posterolateral access [

14,

15]. These changes implicated branches of the superior gluteal nerve, which are more exposed during lateral dissections. Neither study observed spontaneous activity in GMAX or sartorius, suggesting that denervation was localized to specific gluteal-muscle nerve branches.

Chomiak et al. [

11] provided one of the most comprehensive comparative analyses of gluteal nerve involvement, examining 70 patients before and 3–9 months after surgery with anterolateral, transgluteal, or posterior approaches. Needle EMG revealed clear approach-specific patterns: the anterolateral approach resulted in the highest rate of TFL denervation (73%) but largely preserved GMED and GMAX; the transgluteal approach produced the most frequent partial denervation of GMED (81.8%) and also affected TFL and GMAX; the posterior approach showed higher rates of GMAX involvement (71.4%) and moderate GMED changes (53.3%). Notably, despite substantial EMG abnormalities, clinical abductor strength was not significantly reduced, supporting the presence of compensatory strategies that mask underlying deficits.

At later follow-up, Robbins et al. [

28] found no significant differences in mean activation amplitude between lateral and posterior approaches during gait. However, the underlying neuromuscular strategies diverged: lateral approaches showed increased GMED activity during stance, whereas posterior approaches were characterized by greater GMAX and hamstring activation. Both patterns differed from those observed in healthy controls, reflecting persistent deviations in neuromuscular coordination rather than complete recovery.

Taken together, these four studies consistently indicate that lateral-based approaches carry greater early risk to branches of the superior gluteal nerve, particularly those supplying TFL and GMED, while posterior approaches tend to spare TFL but may impact GMAX. Over time, however, approach-specific patterns tend to be replaced by more global compensatory strategies, and clinical performance may not reliably mirror the extent of EMG-detected abnormalities. Comparative results are summarized in

Table 3.

3.5. EMG Approaches: Needle and High-Density EMG

Three studies employed advanced EMG techniques—needle EMG, fine-wire EMG, or HD-sEMG —to provide a deeper characterization of neuromuscular status after THA [

19,

29,

31].

Khalifa et al. [

29] documented clear early postoperative abnormalities six weeks after a modified direct lateral approach, including fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, and prolonged MUAP duration in GMED, GMIN, and TFL, with partial resolution by twelve weeks. These findings were consistent with transient involvement of branches of the superior gluteal nerve, indicating that neurophysiological disturbances may persist even when clinical presentation appears satisfactory.

Chopra et al. [

31] combined surface and fine-wire EMG with frequency-domain analysis to assess neuromuscular organization up to one year after THA performed through a direct anterior approach. Despite clinical improvement, none of the evaluated muscles—including GMED, GMAX, iliopsoas, and paraspinals—showed fully normalized temporal or spectral profiles, suggesting ongoing reorganization of motor control.

A third study applied HD-sEMG to provide a high-resolution assessment of neuromuscular recovery. Morsch et al. [

19] used a wearable 64-channel array to longitudinally track GMED activity, deriving multidimensional indices of activation, spatial efficiency, coordination, and pattern fidelity. These indices frequently revealed persistent compensatory activation or incomplete normalization of spatiotemporal patterns, even in participants reporting substantial clinical improvement.

Taking together, evidence from needle EMG, fine-wire EMG, and HD-sEMG indicates that neuromuscular recovery after THA is often incomplete, asymmetric, and characterized by persistent compensatory strategies, even when clinical and radiographic outcomes appear satisfactory. Detailed results are presented in

Table 4.

3.6. EMG Activity Under Load-Bearing and Assisted Conditions

Four studies investigated EMG activity of hip abductors and stabilizers under conditions that alter load distribution or stabilizing demands, including walking with a cane, the Trendelenburg test, and static balance tasks [

18,

21,

26,

32].

Neumann et al. [

32] found that using a contralateral cane significantly reduced GMED activity on the operated side during mid-stance, consistent with the mechanical unloading of the hip abductor moment. In contrast, combining an ipsilateral cane with a contralateral weight led to a marked increase in GMED activation, indicating that subtle changes in external support and load placement can substantially modify the neuromuscular demands imposed on the operated hip.

Ajemian et al. [

26] reported that contralateral cane use shortened the burst duration of GMED and TFL, whereas walking without assistive devices preserved a temporal pattern similar to the preoperative one, even eight months after surgery. These findings suggest that external assistance may modulate neuromuscular activation without necessarily promoting normalization of the underlying control strategies.

During the Trendelenburg test, Kopeć et al. [

21] observed a reversal of typical abductor activation patterns at six months: GMED activity decreased on the operated limb under full load, while it increased on the contralateral limb, especially in patients with bilateral osteoarthritis. This redistribution suggests an unstable strategy in which the contralateral limb assumes a disproportionate share of the stabilizing demand.

Bernard et al. [

18] studied bipedal and unipedal stance 6–8 weeks after anterior THA and found high levels of activation in GMED, GMAX, and TFL, indicating that postural control relies on elevated muscular effort even in relatively simple static conditions. These data support the hypothesis that compensatory patterns are not limited to dynamic tasks but also extend to everyday balance and load-bearing situations.

Taken together, these studies show that EMG organization after THA is highly sensitive to how load is managed and how external support is used. The compensation strategies that emerge appear to reflect enduring neuromuscular adaptations rather than transient transitional states. Complete results are summarized in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

The methodological appraisal demonstrated that all included studies met acceptable standards for EMG acquisition and reporting, despite notable heterogeneity in normalization procedures, preprocessing, and analytical depth. Within this context, the findings of the review indicate that neuromuscular recovery after THA is slower and more complex than suggested by clinical scales, radiographic findings, or basic gait parameters. Across 17 studies using surface, needle, fine-wire, or HD-sEMG, consistent abnormalities were documented in activation timing, amplitude regulation, and motor unit behavior for months—and in some cases up to a year or more—after surgery. These results collectively suggest that the reorganization of hip muscle activation is not a simple byproduct of restored joint mechanics, but rather reflects a prolonged process of neural adaptation, altered load management, and persistent compensatory strategies.

4.1. EMG Alterations During Gait: A Non-Physiological Recovery Trajectory

The available gait studies reveal a clear dissociation between clinical recovery and neuromuscular normalization. Walking ability, pain, and basic functional measures often improve within the first months after THA [

17,

27], yet EMG patterns remain markedly abnormal at all examined follow-up points. A similar dissociation has been documented in total knee arthroplasty, where improvements in pain, range of motion, and spatiotemporal parameters coexist with persistent abnormalities in timing and co-contraction of key muscle groups [

33]. This convergence across joints suggests that standard clinical indices substantially underestimate the persistence of neuromuscular dysregulation after joint replacement.

GMED appears to be a central element in this process. All studies assessing its activation timing [

24,

25,

30] reported delayed onset and reduced pre-activation, indicating a long-standing deficit in anticipatory control of pelvic stability. Even at very long-term follow-up [

20], GMED bursts remain prolonged in phases where activity would normally decline, pointing to a reorganized motor control strategy rather than a transient postoperative impairment.

Alterations in posterior muscles—particularly the biceps femoris and semitendinosus—further reinforce the presence of compensatory recruitment. Posterolateral and lateral approaches consistently show prolonged or persistent hamstring activation during late stance [

17,

24], while long-term observations also document continuous semitendinosus activity across the gait cycle [

20]. This sustained activation pattern suggests that the hamstrings may adopt an atypical stabilizing role, compensating either for residual abductor weakness or for reduced hip extensor efficiency, the latter supported by decreased sagittal-plane hip moments in anterior-approach cohorts [

27]. Such compensations likely alter load distribution across both the hip and lumbar spine.

Different, but comparably dysfunctional, activation patterns are also observed in the flexor and lateral muscle groups, namely the RF, S, and TFL. In lateral and posterolateral approaches [

17,

24], these muscles frequently exhibit prolonged bursts and delayed peaks, reflecting an expanded contribution to frontal-plane stabilization. In contrast, anterior approaches [

27,

30] are characterized by reduced activation amplitudes and poorly defined temporal profiles, suggesting diminished neuromuscular drive and blunted phase specificity. Although the specific manifestations differ, both configurations indicate incomplete restoration of intermuscular coordination and highlight the persistent influence of approach-specific biomechanical perturbations.

Overall, the gait literature strongly suggests that restoration of pain-free walking and acceptable spatiotemporal parameters does not equate to normal neuromuscular control. Persistent delays, compensatory hamstring activity, and approach-specific dysfunctions in flexor–lateral muscles support the need for rehabilitation strategies that explicitly target timing, coordination, and pelvic stability rather than focusing solely on gross functional outcomes.

4.2. Influence of Surgical Approach: Early Divergence, Late Convergence

Studies comparing surgical approaches reveal a two-phase pattern: marked early differences followed by partial convergence over time. In the initial postoperative period, Baker and Moreschini consistently showed that lateral-based approaches produce greater impairment of the abductor complex than posterolateral access, with higher rates of TFL denervation and reduced voluntary recruitment of GMED—findings that point to the vulnerability of superior gluteal nerve branches during lateral dissections [

14,

15]. Chomiak et al. [

11] reinforced this perspective by demonstrating approach-specific denervation profiles: anterolateral access predominantly affecting TFL, transgluteal approaches more frequently compromising GMED, and posterior access showing greater involvement of GMAX. Despite these differences, clinical abductor strength was often preserved, suggesting early compensatory activation.

At longer follow-up, the picture becomes more nuanced. Robbins et al. [

28] observed no major differences in overall activation amplitude between lateral and posterior approaches at 12 months, although the underlying strategies diverged: lateral approaches showed increased GMED activation during stance, whereas posterior approaches relied more on GMAX and hamstrings. These patterns remain distinct from each other and from healthy controls, indicating that long-term neuromuscular organization reflects adaptive compensation rather than a persistent imprint of the surgical route.

In summary, lateral-based approaches impose a higher early neuromuscular burden, with more pronounced deficits in abductor-related muscles, whereas long-term outcomes across approaches shift toward different—but equally non-physiological—compensatory patterns. This highlights the need for targeted early rehabilitation after lateral access and for later interventions focused on correcting the specific compensatory strategies that emerge over time.

4.3. Evidence from Needle and High-Density EMG

Needle EMG provides direct insight into the neurophysiological consequences of THA by identifying denervation signs, impaired recruitment, and early reinnervation processes that remain undetectable through clinical examination alone [

34,

35]. Khalifa et al. [

29] demonstrated that postoperative abnormalities—including fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, and prolonged MUAP duration—are common six weeks after a lateral-based approach, with partial resolution by twelve weeks. These findings indicate that transient involvement of superior gluteal nerve branches may occur more frequently than clinically recognized yet often follows a reversible neurapraxic pattern.

Complementary evidence comes from studies using fine-wire EMG combined with frequency-domain analysis. Chopra et al. [

31] showed that, even one year after direct anterior THA, temporal organization and spectral characteristics of muscle activation remain atypical across several hip and trunk muscles. These persistent deviations suggest that reorganization of motor control extends beyond the timeframe in which clinical outcomes and basic gait parameters appear normalized.

HD-sEMG adds a non-invasive, high-resolution perspective on postoperative neuromuscular status. Longitudinal data from Morsch et al. [

19] revealed that indices reflecting spatial coordination, activation efficiency, and pattern fidelity often remain abnormal despite improvements in patient-reported outcomes. Such dissociations highlight that neuromuscular recovery progresses along a trajectory distinct from subjective or functional recovery.

Taken together, evidence from needle, fine-wire, and high-density EMG indicates a multifaceted pattern of neuromuscular adaptation after THA: early neural vulnerability, incomplete reorganization of activation timing and spectral features, and persistent deviations in coordination. These approaches shift the focus from whether muscles activate to how effectively they are recruited and integrated within the broader motor strategy, offering deeper insight into the quality of neuromotor restoration after surgery.

4.4. EMG Under Load-Bearing Conditions: Compensation Beyond Gait

Weight-bearing tests and tasks that manipulate external support shed light on how the neuromuscular system manages load after THA. In this domain, the use of canes and the distribution of weight between limbs emerge as particularly important determinants of EMG organization.

The reduction in GMED activity with contralateral cane use observed by Neumann and Ajemian is consistent with biomechanical models showing that contralateral support reduces the abductor moment required at the operated hip [

26,

32]. Conversely, the combination of an ipsilateral cane and contralateral load markedly increases GMED activation, highlighting how small changes in external support can dramatically modulate muscular demand.

The Trendelenburg findings reported by Kopeć et al. [

21] further demonstrate that, months after surgery, abductor activation is often redistributed toward the contralateral limb, particularly when that limb is itself affected by osteoarthritis. Rather than restoring symmetrical load sharing, the system appears to favor strategies that shift the stabilization burden to the less symptomatic or more mechanically favorable side.

Bernard et al. [

18] added another layer by demonstrating that even in static conditions—bipedal and unipedal stance—GMED, GMAX, and TFL activation remains high shortly after surgery, suggesting that postural stability is achieved at the cost of increased muscular effort. These findings support the view that compensatory patterns after THA are not limited to dynamic locomotion but extend across the spectrum of everyday weight-bearing tasks.

Collectively, the evidence indicates that load modulation, external assistance, and postural control strategies play a central role in shaping postoperative EMG patterns. If not specifically addressed in rehabilitation, these compensations may become entrenched, potentially contributing to residual fatigue, altered loading of adjacent joints, and suboptimal functional outcomes.

4.5. Practical Implications

The EMG evidence summarized in this review has several practical implications for postoperative assessment and rehabilitation.

First, the dissociation between clinical recovery and neuromuscular normalization suggests that routine follow-up should not rely exclusively on pain scores, ROM, and general functional tests. Targeted evaluation of muscle activation timing, amplitude, and symmetry—at least in high-risk or symptomatic patients—may help identify persistent deficits that are invisible to standard clinical examination.

Second, the central role of GMED and the consistent presence of hamstring compensations argue in favor of rehabilitation programmes that prioritize abductor pre-activation, pelvic stability, and selective recruitment of hip extensors and stabilizers. Exercises that challenge frontal-plane control and anti-rotation in both dynamic and static conditions may be particularly beneficial.

Third, the marked sensitivity of EMG patterns to load distribution and cane use implies that assistive devices should be prescribed and monitored as active elements of rehabilitation rather than as passive supports. Training patients to use contralateral support correctly and to gradually rebalance load between limbs may reduce the persistence of asymmetric compensations.

Finally, in patients with bilateral osteoarthritis or previous contralateral arthroplasty, special attention should be paid to the “apparently healthy” limb, which may become the primary source of asymmetry and overuse. EMG-informed protocols could help tailor rehabilitation to these complex scenarios.

4.6. Future Directions

The available literature highlights substantial methodological heterogeneity and the need for more sensitive and standardized approaches to characterize neuromuscular reorganization after THA. Several directions for future research can be identified.

First, there is a clear need to standardize EMG protocols, including a minimal set of key muscles (e.g., GMED, GMAX, TFL, RF, BF, ST), shared definitions for onset and offset detection, robust criteria for burst duration, and agreed normalization procedures (e.g., MVIC or standardized isometric tasks). Reproducible locomotor tasks and clearly defined static or load-modified paradigms should be adopted to enable meaningful comparisons across studies.

Second, higher-resolution methods such as HD-EMG, spatiotemporal activation maps, and spinal maps of motor output should be more widely used to infer segmental spinal contributions and to capture subtle reorganizations of motor commands that are not evident in traditional single-channel recordings [

36,

37,

38,

39]. These techniques can reveal microstructural changes in motor unit behavior and intermuscular coordination.

Third, the analysis of multi-muscle coordination through muscle synergy models represents a promising avenue. Approaches such as non-negative matrix factorization, space-by-time decompositions, and newer non-matrix frameworks [

40,

41] can provide insight into the structure, variability, and fragmentation of motor modules, helping to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive reorganization.

Fourth, electrophysiological manifestation of muscular fatigue deserves greater attention. Fourier analysis, short-time Fourier transform (STFT), and wavelet-based methods are well suited for non-stationary EMG and can be applied to isometric and dynamic tasks [

42,

43,

44]. Frequency-based indices such as median and mean power frequency, spectral compression, and related measures may offer complementary information on load-sustaining capacity and endurance after THA.

Finally, extended longitudinal studies with bilateral assessments are needed to determine whether EMG patterns ultimately normalize or whether stable compensatory strategies become the “new normal.” Such designs would help clarify the time course and determinants of neuromuscular reorganization and could inform the optimal timing, intensity, and content of rehabilitation interventions.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that neuromuscular recovery after THA proceeds at a markedly slower pace—and with greater complexity—than clinical and radiographic outcomes alone would suggest. Across surface, needle, fine-wire, and high-density EMG methodologies, persistent abnormalities in muscle activation were consistently documented well into the first postoperative year and, in some cases, beyond.

GMED emerged as the most robust indicator of impaired recovery, showing systematic delays in onset, reduced pre-activation, and prolonged activation during stance across dynamic tasks. Posterior musculature, particularly the hamstrings, frequently assumed an atypical stabilizing role, while anterior and lateral muscles displayed either inefficient or blunted activation patterns depending on the surgical approach. These disruptions were evident during gait, balance tasks, and load-bearing conditions, and they often persisted despite substantial improvements in pain and function.

Although lateral-based approaches were associated with greater early vulnerability—manifested by higher rates of transient denervation and disturbed recruitment of GMED and TFL—the long-term neuromuscular profiles of different approaches converged toward non-physiological compensatory strategies rather than complete normalization. Needle EMG and high-density EMG further revealed that electrophysiological abnormalities may persist even when structural and clinical evaluations appear satisfactory, underscoring a fundamental dissociation between joint reconstruction and neuromuscular integrity.

Taken together, the evidence indicates that neuromuscular recovery after THA is neither automatic nor guaranteed. Instead, it reflects a slow and incomplete process shaped by nerve integrity, compensatory motor behavior, and complex load-management adaptations. The absence of consistent normalization across EMG domains highlights the need for rehabilitation paradigms that explicitly target temporal coordination, abductor pre-activation, selective muscle recruitment, and symmetrical loading, rather than focusing exclusively on strength or ROM.

Within this framework, EMG emerges as an indispensable modality for detecting subtle yet clinically meaningful deficits, guiding postoperative rehabilitation, and refining our understanding of functional recovery following THA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.M., A.Z. and E.G.; methodology, L.P.; software, L.M.; validation, L.P., M.F. and C.T.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, M.C.M., A.Z. and E.G.; resources, C.T. and A.F.; data curation, M.C.M., A.Z. and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.M. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.P.; visualization, C.T. and A.F.; supervision, C.T. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Learmonth, I.D.; Young, C.; Rorabeck, C. The Operation of the Century: Total Hip Replacement. The Lancet 2007, 370, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsdotter, A.-K.; Petersson, I.F.; Roos, E.M.; Lohmander, L.S. Predictors of Patient Relevant Outcome after Total Hip Replacement for Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2003, 62, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasch, A.; Dalén, N.; Berg, H.E. Muscle Strength, Gait, and Balance in 20 Patients with Hip Osteoarthritis Followed for 2 Years after THA. Acta Orthopaedica 2010, 81, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, M.D.; Wilson, S.J.; Hayes, D.A.; Hides, J.A. Hip Muscle Atrophy in Patients with Acetabular Labral Joint Pathology. Clinical Anatomy 2020, 33, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.E.; Eiken, O.; Miklavcic, L.; Mekjavic, I.B. Hip, Thigh and Calf Muscle Atrophy and Bone Loss after 5-Week Bedrest Inactivity. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007, 99, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, A.K.; Kalberer, F.; Pfirrmann, C.W.A.; Dora, C. Soft-Tissue Changes in Hip Abductor Muscles and Tendons after Total Hip Replacement: COMPARISON BETWEEN THE DIRECT ANTERIOR AND THE TRANSGLUTEAL APPROACHES. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 2011, 93-B, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Pulido, L.; Slenker, N.; Macgibeny, M.; Purtill, J.J.; Rothman, R.H. Vascular Injuries After Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2008, 23, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P.; O’Brien, C.P.; Synnott, K.; Walsh, M.G. Damage to the Superior Gluteal Nerve after Two Different Approaches to the Hip. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 1999, 81-B, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.; O’Byrne, J.M.; McCarthy, N.; Jarvis, A.; Mahalingham, K.; Cashman, W.F. DAMAGE TO THE SUPERIOR GLUTEAL NERVE AFTER THE HARDINGE APPROACH TO THE HIP. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 1996, 78-B, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picado, C.H.F.; Garcia, F.L.; Marques, W. Damage to the Superior Gluteal Nerve after Direct Lateral Approach to the Hip. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2007, 455, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomiak, J.; Huráček, J.; Dvořák, J.; Dungl, P.; Kubeš, R.; Schwarz, O.; Munzinger, U. Lesion of Gluteal Nerves and Muscles in Total Hip Arthroplasty through 3 Surgical Approaches. An Electromyographically Controlled Study. HIP International 2015, 25, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, A.; Richardson, C.; Stanton, W.; Durbridge, G.; Donnelly, W.; Hides, J. The Association between Degenerative Hip Joint Pathology and Size of the Gluteus Medius, Gluteus Minimus and Piriformis Muscles. Manual Therapy 2009, 14, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daube, J.R.; Rubin, D.I. Needle Electromyography. Muscle and Nerve 2009, 39, 244–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreschini, O.; Giordano, M.C.; Margheritini, F.; Chiatti, R. A Clinical and Electromyographic Review of the Lateral and Postero-Lateral Approaches to the Hip after Prosthetic Replacement. HIP International 1996, 6, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Bitounis, V. Abductor Function after Total Hip Replacement. An Electromyographic and Clinical Review. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 1989, 71-B, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, F. Can Muscle Coordination Be Precisely Studied by Surface Electromyography? Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2011, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, T.; Listringhaus, R.; Haase, G.-B.; Grau, S.; Mündermann, A. Changes in Gait Patterns and Muscle Activity Following Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Six-Month Follow-Up. Clinical Biomechanics 2013, 28, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.; Razanabola, F.; Beldame, J.; Van Driessche, S.; Brunel, H.; Poirier, T.; Matsoukis, J.; Billuart, F. Electromyographic Study of Hip Muscles Involved in Total Hip Arthroplasty: Surprising Results Using the Direct Anterior Minimally Invasive Approach. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2018, 104, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsch, R.; Böckenförde, T.; Wolf, M.; Landgraeber, S.; Strauss, D.J. Enhanced Rehabilitation after Total Joint Replacement Using a Wearable High-Density Surface Electromyography System. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2025, 6, 1657543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, C.D.; Castillo, M.G.; Dupuy, J.B.; Correa, M.V.; López, M.M.; Gargano, F.G. Gait Analysis of a Subject with Total Hip Arthroplasty. JBM 2022, 10, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, K.; Bereza, P.; Sobota, G.; Hajduk, G.; Kusz, D. The Electromyographic Activity Characteristics of the Gluteus Medius Muscle before and after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, M. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (Product Review). J Can Health Libr Assoc 2024, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, V.; Ganio, D.; Facchin, K.; Cane, L.; Moreira Carneiro, S.; Knaflitz, M. Gait Parameters and Muscle Activation Patterns at 3, 6 and 12 Months After Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, L.; Banzer, W.; Pfeifer, K.; Galm, R. Muscle Activation Pattern of Hip Arthroplasty Patients in Walking. Research in Sports Medicine 2004, 12, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajemian, S.; Thon, D.; Clare, P.; Kaul, L.; Zernicke, R.F.; Loitz-Ramage, B. Cane-Assisted Gait Biomechanics and Electromyography after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2004, 85, 1966–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Noé, N.; Beldame, J.; Matsoukis, J.; Poirier, T.; Brunel, H.; Van Driessche, S.; Lalevée, M.; Billuart, F. Quantitative Gait Analysis after Total Hip Arthroplasty through a Minimally Invasive Direct Anterior Approach: A Case Control Study. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2022, 108, 103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.M.; Gomes, S.K.; Huk, O.L.; Zukor, D.J.; Antoniou, J. The Influence of Lateral and Posterior Total Hip Arthroplasty Approaches on Muscle Activation and Joint Mechanics During Gait. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2020, 35, 1891–1899.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, Y.E.; Hamed, M.; Abdelhameed, M.A.; El-Hamed, M.A.A.; Bakr, H.; Rageh, T.; Abdelnasser, M.K. Hip Abductor Dysfunction Following Total Hip Arthroplasty by Modified Direct Lateral Approach: Assessment by Quantitative Electromyography. EGOJ 2023, 58, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, G.; Serrao, M.; Conte, C.; Castiglia, S.F.; Rucco, F.; Bonacci, E.; Miscusi, M.; Pierelli, F.; Bini, F.; Marinozzi, F.; et al. Direct Anterior Approach for Total Hip Arthroplasty: Hip Biomechanics and Muscle Activation during Three Walking Tasks. Clinical Biomechanics 2021, 89, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, S.; Taunton, M.; Kaufman, K. Muscle Activation Pattern during Gait and Stair Activities Following Total Hip Arthroplasty with a Direct Anterior Approach: A Comprehensive Case Study. Arthroplasty Today 2018, 4, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.A. An Electromyographic Study of the Hip Abductor Muscles as Subjects With a Hip Prosthesis Walked With Different Methods of Using a Cane and Carrying a Load. Physical Therapy 1999, 79, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovachev, N.; Ghayyad, K.; Hashimi, M.; Yakkanti, R. The Role of Electromyography in Postoperative Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. Journal of Orthopaedics 2025, 65, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheriazam, A.; Baghbani, S.; Malakooti, M.; Jahanshahi, F.; Allahyari, M.; Dindar Mehrabani, A.; Amiri, S. Neuromonitoring in Pre-Post and Intraoperative Total Hip Replacement Surgery in Type 4 High-Riding Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 28, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, J.J.; Gendron, D.; Laurin, C.A.; Beaulieu, M.A. Gluteal Nerve Damage Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 1990, 5, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merletti, R.; Holobar, A.; Farina, D. Analysis of Motor Units with High-Density Surface Electromyography. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2008, 18, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, G.; Stegeman, D.F.; Van Engelen, B.G.M.; Zwarts, M.J. Clinical Applications of High-Density Surface EMG: A Systematic Review. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2006, 16, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sîmpetru, R.C.; Cnejevici, V.; Farina, D.; Del Vecchio, A. Influence of Spatio-Temporal Filtering on Hand Kinematics Estimation from High-Density EMG Signals*. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 026014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellitto, A.; De Luca, A.; Gamba, S.; Losio, L.; Massone, A.; Casadio, M.; Pierella, C. Clinical, Kinematic and Muscle Assessment of Bilateral Coordinated Upper-Limb Movements Following Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 3607–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbi, M.F.; Pizzolato, C.; Lloyd, D.G.; Carty, C.P.; Devaprakash, D.; Diamond, L.E. Non-Negative Matrix Factorisation Is the Most Appropriate Method for Extraction of Muscle Synergies in Walking and Running. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborri, J.; Agostini, V.; Artemiadis, P.K.; Ghislieri, M.; Jacobs, D.A.; Roh, J.; Rossi, S. Feasibility of Muscle Synergy Outcomes in Clinics, Robotics, and Sports: A Systematic Review. Applied Bionics and Biomechanics 2018, 2018, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotellessa, F.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Trompetto, C.; Marinelli, L.; Mori, L.; Faelli, E.; Schenone, C.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Biz, C.; Ruggieri, P.; et al. Improvement of Motor Task Performance: Effects of Verbal Encouragement and Music—Key Results from a Randomized Crossover Study with Electromyographic Data. Sports 2024, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merletti, R.; Afsharipour, B.; Dideriksen, J.; Farina, D. Muscle Force and Myoelectric Manifestations of Muscle Fatigue in Voluntary and Electrically Elicited Contractions. In Surface Electromyography : Physiology, Engineering, and Applications; Merletti, R., Farina, D., Eds.; Wiley, 2016; pp. 273–310. ISBN 978-1-118-98702-5. [Google Scholar]

- Puce, L.; Pallecchi, I.; Marinelli, L.; Mori, L.; Bove, M.; Diotti, D.; Ruggeri, P.; Faelli, E.; Cotellessa, F.; Trompetto, C. Surface Electromyography Spectral Parameters for the Study of Muscle Fatigue in Swimming. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 644765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).