1. Introduction

The Fas, also known as Apo-1 or CD95, is a 45 kDa type I transmembrane protein that belongs to the nerve growth factor-tumor necrosis factor receptor family [

1] whereas its natural ligand, Fas ligand (FasL), is a 40 kDa type II membranous protein belonging to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ligand superfamily [

2]. FasL binding to Fas induces apoptotic death of cells expressing functional Fas with Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis being an important pathway in the regulation of immune response and tissue homeostasis [

3,

4,

5].

Fas is constitutively expressed in most human tissues and in lymphocytes [

5,

6] whereas FasL is expressed abundantly in activated T lymphocytes and natural killer cells and in immunoprivileged tissues such as the placenta [

7], the testis and the anterior chamber of the eye [

8] where FasL-expressing cells induce apoptosis in Fas-expressing infiltrating lymphocytes [

6,

7]. Apart from their membrane bound form, both Fas and FasL also exist in a soluble form. Soluble Fas (sFas) is generated by alternative mRNA splicing [

9] whereas soluble FasL (sFaL) is produced by metalloprotease cleavage of the membrane bound protein [

10,

11].

Alterations in the expression of both Fas and FasL have been documented in hemopoietic and solid malignancies including pancreatic cancer [

12,

13,

14,

15] and may represent a mechanism by which cancer cells escape immune surveillance [

16,

17,

18]. FasL-expressing tumor cells counterattack the host immune system by inducing apoptosis in Fas-expressing antitumor T lymphocytes whereas loss of Fas expression and/or function allows cancer cells to escape the physiological Fas-mediated apoptotic pathways resulting in tumor progression and metastasis as has been shown in experimental studies [

19,

20].

Elevated levels of sFas have been detected in the serum of patients with hemopoietic malignancies and solid tumors in a manner directly related to tumor stage and burden [

21,

22,

23]. Tumor-derived sFas may suppress tumor cell apoptosis by blocking FasL on lymphocytes thus facilitating tumor progression [

24,

25]. The proteolytically cleaved sFasL has been shown to be an inducer of apoptosis although less active than the membrane-bound FasL [

26] and, therefore, elevated serum levels of sFasL in cancer patients [

27,

28,

29] may represent an additional mechanism of immune escape [

30,

31]. These findings underline the complex interactions between Fas and FasL within the Fas/FasL system and suggest more complex roles for these molecules at the interface of tumor cells with the host immune system. Therefore, simultaneous evaluation of both Fas and FasL levels is very important when studying their expression and/or function in cancers patients. The clinical significance of both sFas and sFasL in patients with pancreatic and papilla of Vater carcinomas has not been studied before, and their prognostic value is unknown.

In this study, we evaluated the serum concentrations of sFas and sFasL and their ratio in patients with pancreatic and papilla of Vater carcinomas in comparison with healthy controls and assessed their relationship to clinicopathological features and patient survival. The changes in preoperative sFas and sFasL levels after tumor surgery were also evaluated.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients and Healthy Controls

One hundred twenty-three consecutive patients with the presumptive diagnosis of pancreatic or papilla of Vater carcinoma were studied prospectively. In 27 patients, the final diagnosis was benign disease or tumors of the periampullary area other than pancreatic or papilla of Vater adenocarcinomas. These patients were excluded from further analysis. The remaining 96 patients (67 men and 29 women; mean age 70±9 (range, 43-93) years) had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (82 patients) or adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater (14 patients) and were included in the study. No patient had received chemotherapy, irradiation or any intervention for the relief of jaundice before blood sampling. Tumor staging was based on radiological reports (abdominal ultrasonography, computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging), operative findings and pathology reports and was made according to 6th edition of the TNM classification of the International Union Against Cancer. Patients were followed prospectively and the dates and causes of death recorded.

The control group consisted of 53 healthy volunteers (35 men and 18 women, mean age 67±11 (range 42-82) years). The absence of disease was assessed by clinical history, physical examination and routine laboratory tests including liver and renal function tests.

The study was performed according to the Helsinki declaration with an informed consent obtained from all patients and controls.

2.2. Blood Samples and Assays

Venous blood samples were collected into sterile glass tubes (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, UK) in the morning between 8.00 and 9.00 h after an overnight fast. Blood samples were allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 2000g for 10 minutes. Serum was separated, aliquoted and stored at -80oC until assay. Serum samples from cancer patients were collected on admission and 30 days after surgery.

Serum sFas and sFasL concentrations were determined using solid phase, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) designed to measure soluble levels of Fas and FasL in cell culture supernatant, serum and plasma (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Both assays employ the quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique using recombinant human Fas and FasL with antibodies raised against the recombinant proteins, respectively. Their sensitivity was 20 pg/ml for sFas and 1 pg/ml for sFasL. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microtitre plate reader (Anthos 2001, Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, VA, USA). The serum concentrations of sFas and sFasL were extracted from the standard curves and their ratio was calculated. All samples were assayed in duplicate by an investigator who was blinded to the diagnosis and clinical details.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The distributions of the data were found to be normally distributed, and hence the results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD), with parametric tests being employed to assess statistically significant differences. The analysis of variance (ANOVA), the unpaired t-test and the paired t-test test were used to evaluate differences between multiple groups, unpaired and paired observations, respectively. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for the multivariate analysis after univariate analysis had defined relevant prognostic variables. Survival curves were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons were made with the log-rank test. Significance was presumed at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL, and sFas/sFasL Ratio in Carcinoma Patients and Healthy Controls

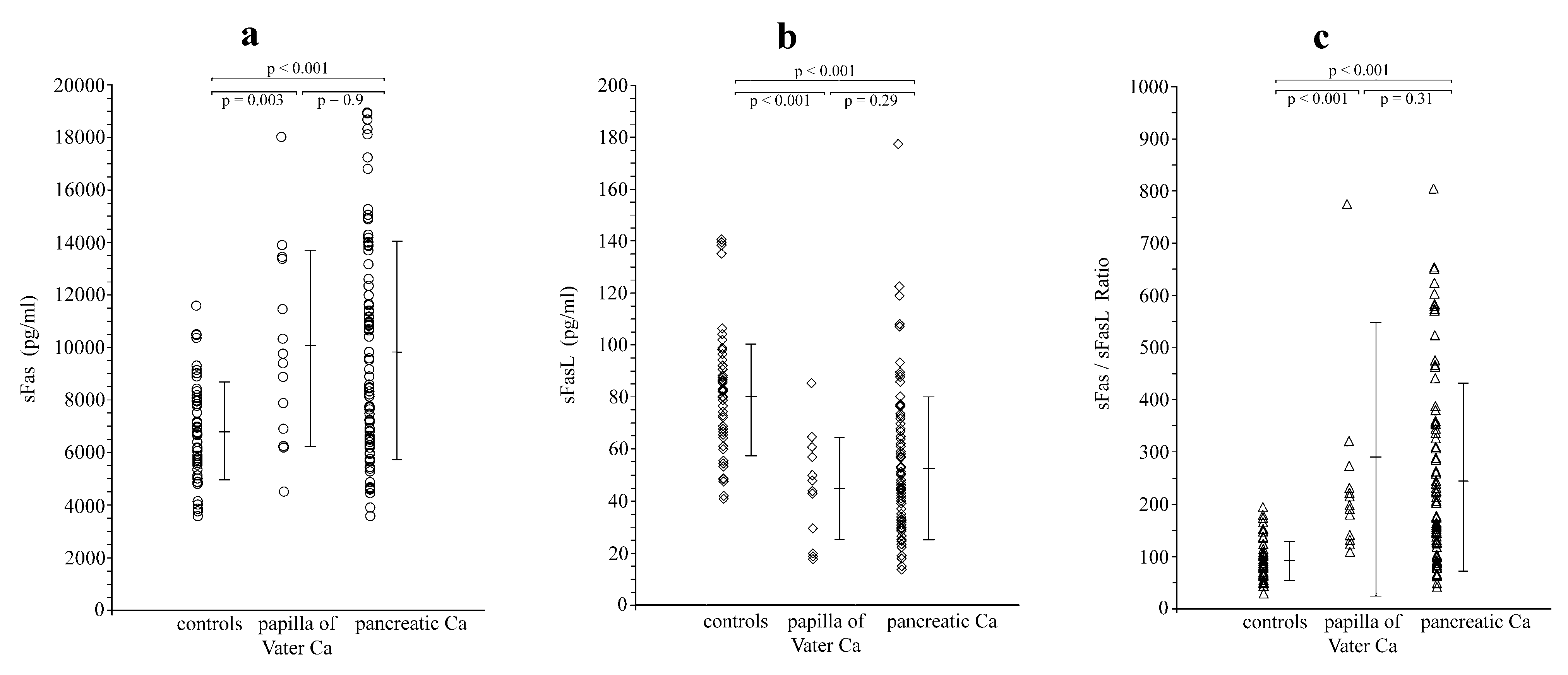

Serum levels of sFas and sFasL in control subjects were 6,784±1,864 pg/ml and 80.6±23.2 pg/ml, respectively. Their sFas/sFasL ratio was 91.2±37.5. Pancreatic and papilla of Vater carcinoma patients as a group showed significantly higher preoperative sFas levels (9,871±4,078 pg/ml;

p < 0.001), significantly lower sFasL levels (51.7±26.2 pg/ml;

p < 0.001), and a significantly higher sFas/sFasL ratio (251.9±188.6;

p < 0.001) when compared with healthy controls. These findings remained valid also when pancreatic and ampullary carcinoma patients were considered as separate groups and compared with the healthy controls (

Figure 1).

There were no statistically significant differences regarding sFas and sFasL levels and their ratio among patients with pancreatic or ampullary carcinoma (

Table 1).

3.2. Correlations Between Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL, and sFas/sFasL Ratio in Carcinoma Patients and Pathological Features

Patients with lymph node metastases had significantly (

p = 0.04) higher sFas levels, significantly (

p = 0.03) lower sFasL levels and a significantly (

p = 0.04) higher sFas/sFasL ratio when compared with those without lymph node involvement. The patients with distant metastases also had significantly (

p < 0.001) higher sFas levels, significantly (

p = 0.03) lower sFasL levels and a significantly (

p < 0.001) higher sFas/sFasL ratio in comparison with patients without distant metastases. The levels of sFas correlated significantly (

p < 0.001, ANOVA) with disease stage with higher sFas levels detected as the disease stage increased. The levels of sFasL also correlated significantly (

p = 0.04, ANOVA) with disease stage with lower sFasL levels related to increased stage of disease. Finally, the sFas/sFasL ratio correlated significantly (

p < 0.001, ANOVA) with disease stage with higher ratios reflecting advanced disease stage (

Table 2).

There were no significant relationships between sFas and sFasL levels and their ratio with tumor size (T class) and degree of differentiation.

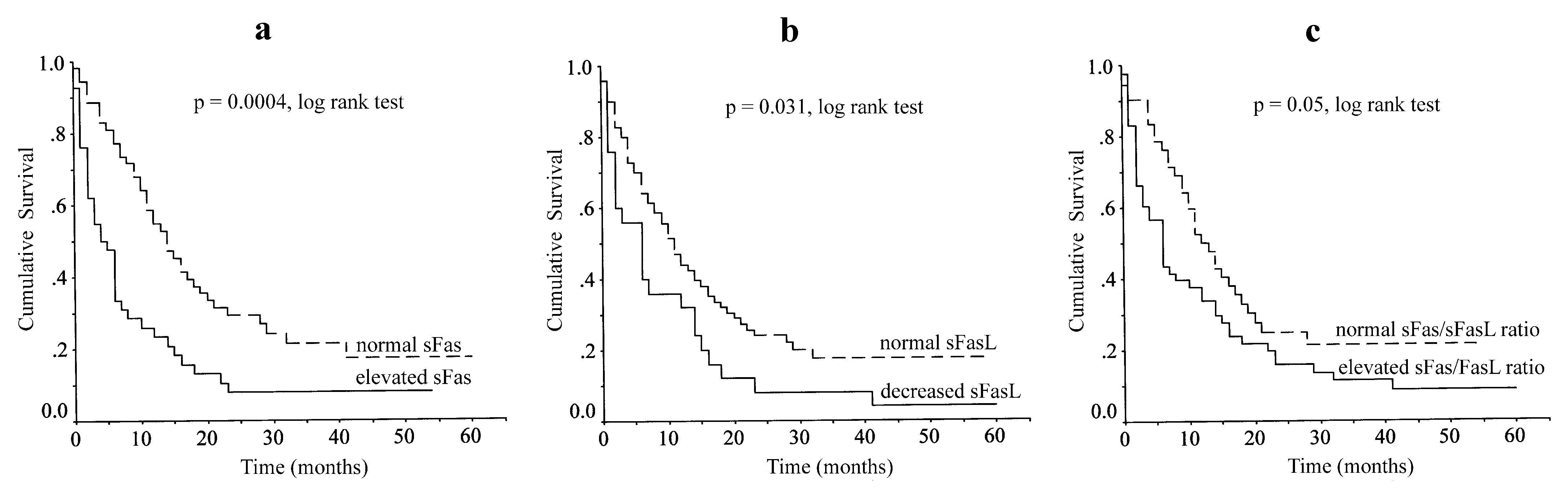

3.3. Correlations Between Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL, and sFas/sFasL Ratio and Patient Survival

Since data were normally distributed, the normal ranges for sFas, sFasL and sFas/sFasL ratio were defined as the mean ± 2SD of the respective values in the healthy control group. The resulted ranges were 3,055-10,513 pg/ml for sFas, 34-127 pg/ml for sFasL, and 16-166 for their ratio. Using these cut-off limits, abnormally elevated sFas levels were found in 42/96 patients (43.7%); 37/82 (45.1%) and 5/14 (35.7%) in pancreatic and Vater adenocarcinoma respectively. Abnormally low sFasL levels were found in 25/96 patients (26%); 21/82 (25.6%) and 4/14 (28.6%) in pancreatic and Vater adenocarcinoma respectively, whereas 53/96 patients (55.2%); 43/82 (52.4%) and 10/14 (71.4%) in pancreatic and Vater adenocarcinoma respectively, showed an abnormally elevated sFas/sFasL ratio.

In this series, there were 4 deaths during the first postoperative month because of postoperative complications. These patients were also included in survival analysis as censored cases. Patient follow-up ranged between 17-62 months (mean 40.4±12.8 months) with only1 patient being lost to follow-up. During this period, 75 patients died from disease progression and 16 patients remained alive. Log-rank analysis showed elevated sFas levels (

p = 0.0004), decreased sFasL levels (

p = 0.031) and elevated sFas/sFasL ratio (

p = 0.05) to correlate with poor overall survival (

Figure 2).

Univariate analysis showed tumor type, tumor resection, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, TNM stage, sFas and sFasL levels to be significant factors affecting overall survival. The prognostic value of the sFas/sFasL ratio was found to be marginally significant (

Table 3). Multivariate regression analysis revealed that the type of the tumor (hazard ratio (HR): 3.04; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.27-7.27;

p = 0.012), tumor resection (HR: 1.71; 95% CI: 0.94-3.11;

p = 0.077), sFas levels (HR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.15-3.22;

p = 0.013), and disease stage (HR: 1.5; 95% CI: 1.08-2.08;

p = 0.014), are independent prognostic factors for patient survival.

3.4. The Effect of Surgery on Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL, and sFas/sFasL Ratio

Radical resection for cure of the primary tumor was performed in 39 patients whereas 57 patients underwent either palliative bypass surgery (52 patients) or endoscopic stenting (5 patients). To avoid any interference on the serum levels of Fas and FasL, 4 patients in each group (4 patients who died in the postoperative period and another 4 patients with septic postoperative complications) were excluded from the analysis.

One month following radical tumour resection, there was a significant decrease in the serum levels of sFas (

p = 0.026) and a significant increase in the serum levels of sFasL (

p = 0.0001) with their values being not statistically different from those in the healthy control group. The sFas/sFasL ratio also decreased significantly (

p = 0.002) following radical resection of the tumor when compared with preoperative values (

p = 0.0002) but remained significantly higher than in control subjects (

Table 4).

In contrast, postoperative serum levels of sFas, sFasL and their ratio in patients undergoing palliative bypass or endoscopic stenting did not differ from their corresponding values before intervention.

4. Discussion

In this study, both pancreatic and papilla of Vater carcinoma patients showed significantly higher serum levels of sFas, lower sFasL levels and higher sFas/sFasL ratio, when compared with healthy controls, that were associated with advanced disease and poor overall survival but only sFas levels were found to be an independent prognostic factor for patient survival.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most aggressive tumors with poor response to therapy and dismal prognosis. Alterations in cell apoptosis such as diminished Fas/FasL induced apoptosis may contribute to tumor progression and resistance to therapy [

17,

31,

32,

33]. Although multiple mechanisms are involved in the escape of transformed cells from the host immune surveillance and in the apoptotic elimination of tumor cells, the Fas/FasL pathway plays a pivotal role in apoptosis. Our findings of aberrant serum levels of the soluble forms of Fas and FasL in cancer patients suggest a possible function in the loss of sensitivity of cancer cells to the induction of apoptosis. Pancreatic cells express both Fas and FasL and loss of Fas has been correlated with malignant transformation and biologic aggressiveness in pancreatic adenocarcinoma [

32]. Pancreatic cells have been shown to be resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis, a mechanism that possibly contributes to their malignant transformation, and this is not due to receptor down regulation or Fas-associated phosphatase up-regulation [

16,

34]. Interestingly, endogenous decoy receptor 3, a soluble receptor against FasL, has been correlated to FasL loss of sensitivity of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by antagonistically blocking the growth inhibition signals [

26,

35]. It has been suggested that sFas could provide apoptosis resistance to pancreatic carcinoma cells acting in an autocrine manner with tumor-derived sFasL exerting a paracrine pro-apoptotic effect in the microenvironment of pancreatic cancers [

29].

Our results are in accordance to those reported by Bellone et al. [

29], showing significantly higher sFas levels in the serum of pancreatic cancer patients when compared to healthy controls. In our study, sFas levels were examined in both pancreatic and Vater adenocarcinoma patients and were found elevated in both groups. In contrast, sFasL levels were found to be significantly lower in carcinoma patients compared to healthy controls. These results are in agreement to previous findings showing detectable serum levels of sFasL in only few patients with metastatic disease despite elevated sFasL secretion by pancreatic cancer cells [

31,

36]. Very low or no measurable levels of sFasL have been reported in prostate cancer patients [

37]. Hepatocellular and bile duct carcinoma patients have also decreased serum sFasL levels compared to healthy subjects [

38,

39]. We also calculated the sFas/sFasL ratio and found significantly higher ratios in carcinoma patients compared to healthy controls suggesting a relative predominance of sFas. Considering these findings, it could be postulated that high levels of sFas secreted by tumor cells bind and neutralise a considerable fraction of sFasL, resulting in lower sFasL levels in the serum.

Correlation of serum levels of sFas, sFasL and their ratio with clinicopathological parameters revealed significant relationships with features of tumor aggressiveness such as lymph node and distant metastases and advance stage. Furthermore, elevated sFas, decreased sFasL levels and elevated sFas/sFasL ratio correlated significantly with poor overall survival with sFas level being an independent prognostic factor for patient survival. Increased serum sFas levels have been reported in a variety of human malignancies including gynaecological malignancies, melanoma and hepatocellular, bladder and renal cell carcinomas [

23,

28,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Serum sFas levels have been correlated with poor prognosis and decreased overall survival in bladder cancer or metastatic prostate cancer and renal cell carcinoma [

23,

28,

37,

42,

44], with shortened disease-free and overall survival in ovarian cancer [

41]. Although aberrant Fas and FasL expression has been shown in pancreatic cancer their prognostic value remains uncertain [

14,

15,

17] and there is no evidence on their soluble forms as prognostic factors. Our findings of sFas being an independent prognostic factor for patient survival underline its prognostic potential. We also evaluated the ratio of sFas/sFasL, suggesting that the ratio may better reflect changes in both factors during cancer progression, and showed that elevated sFas/sFasL ratio correlates with poor overall survival but failed to achieve an independent significance.

In this study, for the first time, we studied changes in sFas and sFasL levels after treatment. Serum levels of sFas decreased and of sFasL increased significantly and their ratio was accordingly affected after resection for cure but such changes were not observed in cases of palliative treatment. These findings suggest that the elevated sFas levels in cancer patients associate with the presence of the tumor which is probably the source of Fas secretion, since following radical resection, sFas levels decreased, becoming not significantly different from those in the healthy control group. There is in vivo evidence that pancreatic tumors secrete sFas in the serum as opposed to the absence of sFas in the culture media of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines [

25]. Differently, serum sFasL levels increased after surgery, becoming not significantly different to those measured in the control group, possibly as a result of the absence of high sFas concentration in the patient serum that would neutralize them. The sFas/sFasL ratio also decreased significantly but remained significantly higher than in control subjects. Whether these changes may serve as a possible indicator for potentially curative tumor resection remains to be documented.

Apoptosis is the physiological process of eliminating harmed cells and its suppression is an essential step in carcinogenesis and in the development of resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [

17,

31,

32]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms involved could be crucial for carcinoma prognosis, but also in designing new therapeutic anti-cancer strategies, aiming to restore the apoptotic regulation of tumor cells. Fas-mediated apoptosis is one of the major induction pathways and is often impaired in cancer cells thus allowing their irregular growth. Nevertheless, the exact relationship between membrane and soluble forms of Fas and FasL has not been fully elucidated. Multiple mechanisms could be involved, including loss of the cell-surface Fas, rendering carcinoma cells resistant to apoptosis or receptor activation by a truncated ligand, such as the soluble form of FasL. Alternatively, neutralization of FasL by sFas would prevent the ligand from triggering apoptosis. There is some evidence that sFas suppresses Fas/FasL mediated apoptosis whereas sFasL induces apoptosis by binding to Fas expressing target cells [

10,

24,

30]. Our findings of elevated sFas and decreased sFasL levels in cancer patients are in agreement with these observations. It is conceivable that increased sFas levels may correspond to suppressed apoptosis and decreased sFasL levels may reflect diminished apoptosis in pancreatic and papilla of Vater carcinoma patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in this study we found elevated levels of sFas in the serum of pancreatic and papilla of Vater adenocarcinoma patients compared to healthy controls. Our results suggest that a possible mechanism that cancer cells develop in order to escape apoptosis induction is neutralization of FasL by increased concentrations of sFas. High sFas and low sFasL serum levels along with high sFas/sFasL ratio in cancer patients correlated significantly with clinicopathological features of aggressive tumors and with poor overall patient survival. These chances were specific to the presence of the tumor since as seen by their changes after surgery. Serum level of sFas was shown to be an independent prognostic factor for patient survival suggesting its potential clinical usefulness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., H.B. and A.J.K.; methodology, B.A. and A.J.K.; validation, B.A.; formal analysis, S.A., H.B. and B.A.; investigation, D.O., M.K., S.P.; resources, S.A., H.B. and I.T.; data curation, D.O., M.K., S.P. and B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A., H.B. and A.J.K.; writing—review and editing, B.A. and A.J.K.; visualization, D.O., M.K., S.P.; supervision, A.J.K.; project administration, H.B. and I.T.; funding acquisition, B.A., and I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Fotini Papachristou for her valuable assistance in analyzing the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oehm, A.; Behrmann, I.; Falk, W.; Pawlita, M.; Maier, G.; Klas, C.; Li-Weber, M.; Richards, S.; Dhein, J.; Trauth, B.C. Purification and molecular cloning of the APO-1 cell surface antigen, a member of the tumor necrosis factor/nerve growth factor receptor superfamily. Sequence identity with the Fas antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 10709–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, T.; Takahashi, T.; Golstein, P.; Nagata, S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell 1993, 75, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, N.; Yonehara, S.; Ishii, A.; Yonehara, M.; Mizushima, S.; Sameshima, M.; Hase, A.; Seto, Y.; Nagata, S. The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for human cell surface antigen Fas can mediate apoptosis. Cell 1991, 66, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderson, M.R.; Tough, T.W.; Davis-Smith, T.; Braddy, S.; Falk, B.; Schooley, K.A.; Goodwin, R.G.; Smith, C.A.; Ramsdell, F.; Lynch, D.H. Fas ligand mediates activation-induced cell death in human T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 181, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithäuser, F.; Dhein, J.; Mechtersheimer, G.; Koretz, K.; Bruderlein, S.; Henne, C.; Schmidt, A.; Debatin, K.M.; Krammer, P.H.; Moller, P. Constitutive and induced expression of APO-1, a new member of the nerve growth factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, in normal and neoplastic cells. Lab. Inves.t 1993, 69, 415–429. [Google Scholar]

- Xerri, L.; Devilard, E.; Hassoun, J.; Mawas, C.; Birg, F. Fas ligand is not only expressed in immune privileged human organs but is also coexpressed with Fas in various epithelial tissues. Mol. Pathol. 1997, 50, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckan, D.; Steele, A.; Cherry; Wang, B.Y.; Chamizo, W.; Koutsonikolis, A.; Gilbert-Barness, E.; Good, R.A. Trophoblasts express Fas ligand: a proposed mechanism for immune privilege in placenta and maternal invasion. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 3, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, P.M.; Pan, F.; Plambeck, S.; Ferguson, T.A. FasL-Fas interactions regulate neovascularization in the cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, I.; Fiucci, G.; Papoff, G.; Ruberti, G. Three functional soluble forms of the human apoptosis-inducing Fas molecule are produced by alternative splicing. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 2706–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Suda, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nagata, S. Expression of the functional soluble form of human fas ligand in activated lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayagaki, N.; Kawasaki, A.; Ebata, T.; Ohmoto, H.; Ikeda, S.; Inoue, S.; Yoshino, K.; Okumura, K.; Yagita, H. Metalloproteinase-mediated release of human Fas ligand. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 82, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Shimosegawa, T.; Masamune, A.; Hirota, M.; Koizumi, M.; Toyota, T. Fas ligand is frequently expressed in human pancreatic duct cell carcinoma. Pancreas 1999, 19, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornmann, M.; Ishiwata, T.; Kleeff, J.; Beger, H.G.; Korc, M. Fas and Fas-ligand expression in human pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 2000, 231, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernick, N.L.; Sarkar, F.H.; Tabaczka, P.; Kotcher, G.; Frank, J.; Adsay, N.V. Fas and Fas ligand expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2002, 25, e36–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Elnemr, A.; Kitagawa, H.; Kayahara, M.; Takamura, H.; Fujimura, T.; Nishimura, G.; Shimizu, K.; Yi, S.Q.; Miwa, K. Fas ligand expression in human pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 12, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungefroren, H.; Voss, M.; Jansen, M.; Roeder, C.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Kremer, B.; Kalthoff, H. Human pancreatic adenocarcinomas express Fas and Fas ligand yet are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar]

- von Bernstorff, W.; Spanjaard, R.A..; Chan, A.K.; Lockhart, D.C.; Sadanaga, N.; Wood, I.; Peiper, M.; Goedegebuure, P.S.; Eberlein, T.J. Pancreatic cancer cells can evade immune surveillance via nonfunctional Fas (APO-1/CD95) receptors and aberrant expression of functional Fas ligand. Surgery 1999, 125, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnemr, A.; Ohta, T.; Yachie, A.; Kayahara, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Fujimura, T.; Ninomiya, I.; Fushida, S.; Nishimura, G.I.; Shimizu, K.; Miwa, K. Human pancreatic cancer cells disable function of Fas receptors at several levels in Fas signal transduction pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen-Schaub, L.B.; van Golen, K.L.; Hill, L.L.; Price, J.E. Fas and Fas ligand interactions suppress melanoma lung metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 188, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnemr, A.; Ohta, T.; Yachie, A.; Kayahara, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Ninomiya, I.; Fushida, S.; Fujimura, T.; Nishimura, G.; Shimizu, K.; Miwa, K. Human pancreatic cancer cells express non-functional Fas receptors and counterattack lymphocytes by expressing Fas ligand; a potential mechanism for immune escape. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipping, E.; Debatin, K.M.; Stricker, K.; Heilig, B.; Eder, A.; Krammer, P.H. Identification of soluble APO-1 in supernatants of human B- and T-cell lines and increased serum levels in B- and T-cell leukemias. Blood 1995, 85, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midis, G.P.; Shen, Y.; Owen-Schaub, L.B. Elevated soluble Fas (sFas) levels in nonhematopoietic human malignancy. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 3870–3874. [Google Scholar]

- Ugurel, S.; Rappl, G.; Tilgen, W.; Reinhold, U. Increased soluble CD95 (sFas/CD95) serum level correlates with poor prognosis in melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, C.; Shapiro, J.P.; Brauer, M.J.; Kiefer, M.C.; Barr, P.J.; Mountz, J.D. Protection from Fas-mediated apoptosis by a soluble form of the Fas molecule. Science 1994, 263, 1759–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, G.; Smirne, C.; Carbone, A.; Mareschi, K.; Dughera, L.; Farina, E.C.; Alabiso, O.; Valente, G.; Emanuelli, G.; Rodeck, U. Production and pro-apoptotic activity of soluble CD95 ligand in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P.; Holler, N.; Bodmer, J.L.; Hahne, M.; Frei, K.; Fontana, A.; Tschopp, J. Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 187, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, S.; Kuwano, H.; Shimura, T.; Morinaga, N.; Mochiki, E.; Asao, T. Circulating soluble Fas ligand in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 89, 2560–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, Y.; Hongo, F.; Sato, N.; Ogawa, O.; Yoshida, O.; Miki, T. Significance of serum soluble Fas ligand in patients with bladder carcinoma. Cancer 2001, 92, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, G.; Smirne, C.; Carbone, A.; Mareschi, K.; Dughera, L.; Farina, E.C.; Alabiso, O.; Valente, G.; Emanuelli, G.; Rodeck, U. Production and pro-apoptotic activity of soluble CD95 ligand in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar]

- Suda, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Tanaka, M.; Ochi, T.; Nagata, S. Membrane Fas ligand kills human peripheral blood T lymphocytes, and soluble Fas ligand blocks the killing. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plate, J.M.; Shott, S.; Harris, J.E. Immunoregulation in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1999, 48, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichmann, E. The biological role of the Fas/FasL system during tumor formation and progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2002, 12(4), 309–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Liang, W.B.; Zhu, R.; Wang, B.; Miao, Y.; Xu, Z.K. Pancreatic cancer counterattack: MUC4 mediates Fas-independent apoptosis of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medema, J.P.; de Jong, J.; van Hall, T.; Melief, C.J.; Offringa, R. Immune escape of tumors in vivo by expression of cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 1033–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Song, S.; He, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, D.; Zhu, D. Silencing of decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) expression by siRNA in pancreatic carcinoma cells induces Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Suda, T.; Haze, K.; Nakamura, N.; Sato, K.; Kimura, F.; Motoyoshi, K.; Mizuki, M.; Tagawa, S.; Ohga, S.; Hatake, K.; Drummond, A.H.; Nagata, S. Fas ligand in human serum. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, Y.; Nagakawa, O.; Fuse, H. Prognostic significance of serum soluble Fas level and its change during regression and progression of advanced prostate cancer. Endocr. J. 2003, 50, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Nakajima, Y.; Hisanaga, M.; Kayagaki, N.; Kanehiro, H.; Aomatsu, Y.; Ko, S.; Yagita, H.; Yamada, T.; Okumura, K.; Nakano, H. The alteration of Fas receptor and ligand system in hepatocellular carcinomas: how do hepatoma cells escape from the host immune surveillance in vivo? Hepatology 1999, 30, 413–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Sasaki, T.; Miyata, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Chayama, K. Fas and Fas ligand: Expression and soluble circulating levels in bile duct carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 11, 1183–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, R.; Tadao, T.; Shinji, S.; Akira, Y. Serum soluble Fas level as a prognostic factor in patients with gynaecological malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 3576–3580. [Google Scholar]

- Hefler, L.; Mayerhofer, K.; Nardi, A.; Reinthaller, A.; Kainz, C.; Tempfer, C. Serum soluble Fas levels in ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 96, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo, P.; Solano, T.; Vazquez, B.; Bauza, A.; Idoate, M. Fas and Fas ligand: expression and soluble circulating levels in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodo, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakajima, Y.; Matsunaga, T.; Nakayama, N.; Ogura, N.; Kayagaki, N.; Okumura, K.; Koike, T. Elevated serum levels of soluble Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 112, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonomura, N.; Nishimura, K.; Ono, Y.; Fukui, T.; Harada, Y.; Takaha, N.; Takahara, S.; Okuyama, A. Soluble Fas in serum from patients with renal cell carcinoma. Urology 2000, 55, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).