1. Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder of motile cilia that affects approximately 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 individuals worldwide [

1,

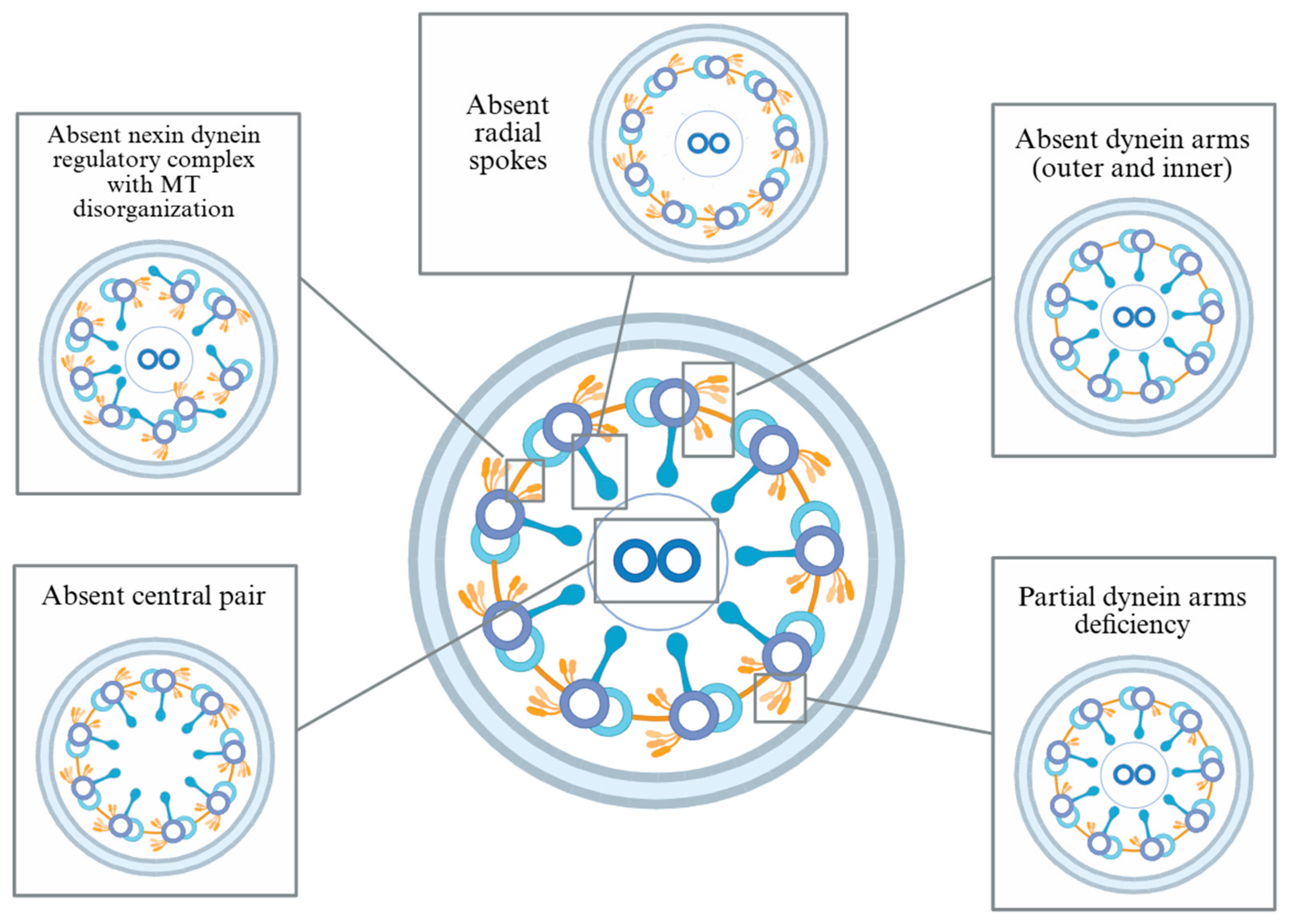

2]. Motile cilia line the respiratory tract, paranasal sinuses, middle ear, and reproductive system, where their coordinated beating is essential for mucociliary clearance. Dysfunctional or absent ciliary motion in PCD impairs this clearance, leading to chronic and recurrent infections of the upper and lower airways, including the paranasal sinuses and middle ear. The underlying cilium cross-section is normally arranged in a 9+2 microtubule (MT) configuration, and structural variants associated with PCD disrupt coordinated ciliary beating. These variants include absence of dynein motor protein arms, radial spokes, nexin-dynein regulatory complex, or the central MT pair [

3,

4,

5,

6] (

Figure 1). In children, the classic triad of PCD includes chronic wet cough, respiratory distress, and year-round nasal congestion [

6]. Approximately 50% of individuals with PCD also exhibit situs inversus totalis, a laterality defect that, when combined with bronchiectasis and rhinosinusitis, is known as Kartagener syndrome [

7,

8].

Upper airway involvement is a hallmark of the disease, yet the specific burden and diversity of otologic and sinonasal manifestations in children remain under-characterized in the literature. Previous cohort studies demonstrate that pediatric patients with PCD frequently experience chronic otitis media with effusion and varying degrees of hearing loss [

9,

10,

11]. Sinonasal involvement is similarly common, and has been shown to include chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis, nasal congestion, and imaging-confirmed paranasal sinus disease [

12,

13,

14]. These manifestations not only cause persistent symptoms but also place children at risk for long-term sequelae, including speech and language delays, impaired academic performance, and reduced quality of life.

Although otolaryngologic manifestations have been described across mixed-age and adult-focused cohorts, the pediatric phenotype has not been systematically synthesized from cohort-level patient data. Given the diagnostic and developmental implications of upper airway disease in children with PCD, as well as overall disease rarity, a focused review of pediatric-specific findings is essential.

This systematic review aims to evaluate and summarize the existing cohort-based literature on otologic and sinonasal manifestations in pediatric PCD. By identifying the most frequently reported symptoms and related interventions, this review seeks to inform clinical management and guide future research in the multidisciplinary care of children with PCD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

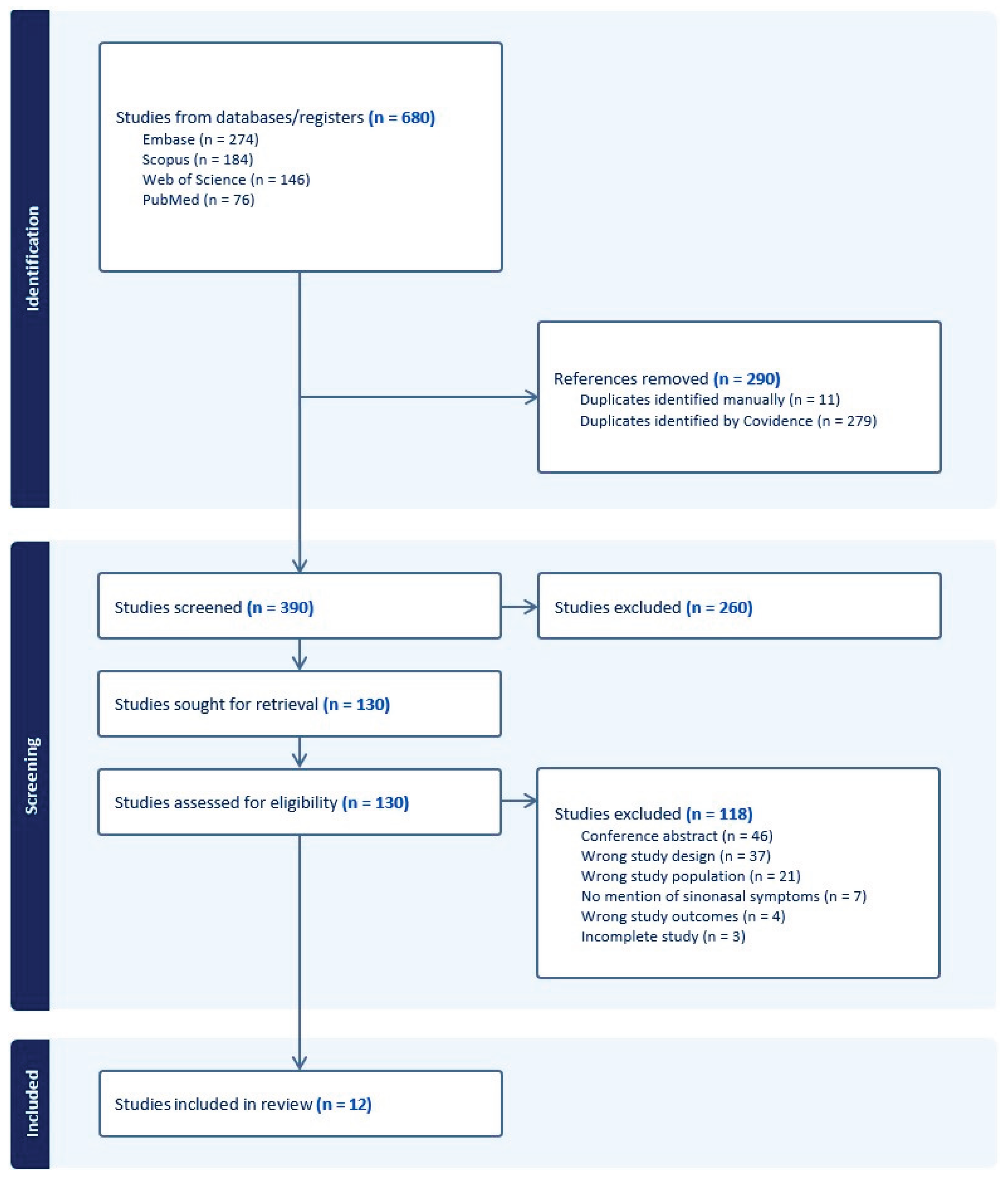

A systematic search was conducted in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

15]. A trained medical librarian (L.B.) queried the literature using the following citation databases: PubMed for MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. Databases were searched using both keywords and controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH]), when available, around the topics of primary ciliary dyskinesia of the nose or ear in children. The search was completed on July 21, 2025, and yielded 680 citations. Deduplication was performed both manually and by using Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), a web-based systematic review management tool, resulting in 390 unique records for title and abstract screening. Of these, 130 records underwent full-text screening, and 12 studies met eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis. Full database search strategies are provided in

Supplementary Item 1.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) were published on or after January 2020; 2) included only pediatric patients (age <18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of PCD, including Kartagener syndrome; and 3) reported at least one otologic or sinonasal manifestation, such as otitis media, hearing loss, or chronic rhinosinusitis. We included only observational cohort studies (retrospective or prospective), given their larger sample sizes and improved generalizability. We excluded case reports and case series due to their high risk of reporting bias and limited ability to represent typical clinical patterns. Other exclusion criteria were studies involving adult patients, review articles, editorials/commentaries, meta-analyses, conference abstracts without accessible full text, non-English publications, and studies that did not mention otologic or sinonasal manifestations.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Two reviewers (K.N. and N.B.) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance using Covidence. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (A.P.). Full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility based on predefined criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 2) outlines the full study selection process.

2.4. Data Extraction

The following was collected for each study: number of patients, otologic manifestations, sinonasal manifestations, radiographic imaging if relevant and available, and reported otologic or sinonasal interventions, including surgical procedures or medical management (e.g., nasal rinses, nasal sprays, or antibiotics). Validated symptom scoring systems (e.g., SNOT-22, SN-5) were also extracted when reported. Missing data were not inferred, and variables not reported in the original publication were coded as not reported.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version 16.0. Due to the heterogeneity in study designs, outcome measures, and reporting formats across studies, formal statistical testing and quantitative meta-analysis were not performed. Results were instead synthesized descriptively.

3. Results

Twelve cohort studies met inclusion criteria, encompassing a total 524 pediatric patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PCD [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Table 1 provide a summary of the cohort studies that were included. There was a relatively balanced sex ratio across cohorts, with a combined total of 289 males (52.4%) and 263 females (47.6%). The overall median age across studies was 8.4 years, with individual study medians ranging from 3.7 to 11.8 years. Age ranges were variably reported and included infants as young as one week to adolescents up to 18 years.

Diagnostic confirmation of PCD varied across studies. Seven of twelve applied the American Thoracic Society guidelines, which define PCD by at least one of the following: 1) two pathologic or likely pathogenic mutations in a known PCD gene, 2) identification of a hallmark ultrastructural defect on transmission electron microscopy (TEM), or 3) nasal nitric oxide (nNO) <77 nL/min on at least two occasions with cystic fibrosis ruled out. The remaining studies used combinations of nNO, TEM, high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), and/or genetic testing. One study did not specify diagnostic criteria.

Studies varied in the extent and detail of otologic/sinonasal outcomes assessed, with some focusing primarily on chronic otitis media and hearing, and others providing more comprehensive sinonasal symptom profiling. Notably, cases no. 6 and 11 were published in otolaryngology journals and therefore examined these manifestations more extensively than the other included studies.

3.1. Otologic Manifestations

Otologic symptoms were reported in 11 of 12 included studies, though the extent and method of assessment varied (

Table 2). Across the cohorts that quantified history of otitis media (OM), a total of 240 of 398 assessed patients (60.3%) had a documented history of ear infections. Prevalence varied widely, from one-quarter of children in some series to nearly all in others. Most reports did not distinguish between acute otitis media (AOM), otitis media with effusion (OME), or chronic OM, though one study instead reported a mean of 1.6

+ 2.8 annual OM episodes per patient [

21].

Hearing loss was reported in 8 studies, affecting 150 of 384 assessed children (39.1%). In each cohort, hearing loss was initially reported subjectively by patients or caregivers and subsequently confirmed through formal audiometry. Where specified, conductive hearing loss predominated. For example, Muhonen et al. found hearing loss in 40 patients (58.8%), with conductive loss accounting for 36 cases (90%), often bilateral. A small proportion of children had mixed or unspecified types of hearing loss [

26].

Several studies described the clinical impact of hearing impairment and its management. Baird et al. noted 11 of 13 children (84.6%) with hearing loss in their cohort used hearing aids [

23], while Muhonen et al. reported broader rehabilitation strategies, including softband devices and bone conduction implants in 14 of 27 (51.9%) of their patients [

26].

Other otologic symptoms beyond OM and hearing were reported in two studies. Zawawi and Shapiro’s cohort reported ear fullness in 10 (21.3%), otalgia in 6 (12.7%), and otorrhea in 11 (23.4%) [

21], while Kim el al. reported tympanic membrane perforations in 7 (17.1%) [

24]. Tympanostomy tube (TT) placement was common, reported in more than half of children in the two studies that provided this information [

21,

26]. Children often required multiple sets of tubes, with a mean of 2.04

+ 1.93 per patient in one cohort [

21] and 2.83 per patient (range 1-11 sets) in another [

26]. Post-TT complications, particularly otorrhea and tube occlusion, were frequent in Muhonen’s cohort. In addition, some patients required more advanced procedures, including mastoidectomy (3/68, 4.4%) and removal of congenital cholesteatoma (1, 1.5%).

3.2. Sinonasal Manifestations

Sinonasal symptoms were reported in 10 of 12 included studies, though prevalence estimate varied depending on assessment method and reporting detail (

Table 3). Across the cohorts that specified chronic or recurrent sinusitis, 150 of 191 assessed patients (78.5%) were affected. Rates ranged widely, from 58.5% in the series by Kim et al. to 100% in those by Guo, Lyu, and Zhang et al. [

16,

19,

24,

27]. Some studies confirmed radiographic disease: Guo et al. reported sinusitis on CT in all 42 imaged children, while Lu et al. noted CT evidence of sinusitis in 25 of 61 (41.0%) [

16,

25] (

Table 4). Where sinonasal scoring systems were used, they were recorded; one cohort reported SNOT-22 scores (case no. 6), while no studies used SN-5.

Other sinonasal complaints were inconsistently reported. Nasal obstruction and congestion were described in three studies, affecting 68 of 132 children (51.6%) [

21,

23,

25]. Rhinorrhea was noted in five series, affecting 170 of 246 assessed (69.1%), with study-level proportions ranging from 45.9% to 86.3%. Nasal polyps were less frequently described, identified in only two studies and present in 3 of 64 children (4.7%).

A broader spectrum of sinonasal complaints was described in the cohort by Zawawi and Shapiro et al. [

21]. They documented mouth breathing in 33 (70.2%), snoring in 23 (48.9%), sinus pressure in 9 (19.1%), anosmia in 11 (23.4%), and recurrent epistaxis in 11 (23.4%).

Management strategies were rarely detailed. In Zawawi and Shapiro’s series, 3 children (6.4%) underwent endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for polyposis, while medical therapies included nasal steroids in 11 (23.4%), saline spray in 16 (34.0%), and decongestants in 1 (2.1%).

3.2. Vestibular Manifestations and Objective Findings

Vestibular symptoms were infrequently reported, though two cohorts specifically evaluated balance and inner ear function. Zawawi and Shapiro et al. documented vertigo and imbalance in 19 (76.0%) of their cohort, with objective abnormalities on video head impulse testing and balance assessments in a subset of children [

21].

Several studies also described objective otolaryngologic findings. Imaging was the most frequently reported, with CT evidence of chronic sinus disease present in the majority of children who underwent imaging. Audiometric testing was also performed in one cohort, with more than half assessed (13, 52.0%) demonstrating hearing loss on formal audiograms, even in cases where patients themselves did not report symptoms of hearing loss. Patients-reported sinonasal symptom burden, as shown by SNOT-22 scores, was additionally scribed in one study [

21].

4. Discussion

Primary ciliary dyskinesia is a phenotypically heterogeneous disease that presents with frequent illnesses of the upper and lower respiratory tract, often paired with otologic and sinonasal sequelae that replicate common childhood conditions. Historically, there has been lack of consensus regarding otolaryngologic treatment approaches for this population, due in part likely to the varied presentations, disease rarity, and evidence that upper airway disease in children with PCD often begins early and persists rather than improves with age [

28,

29]. There is also debate regarding the optimal diagnostic approach. TEM has historically been the gold standard; however, studies indicate that 15-30% of affected patients demonstrate normal or near-normal ciliary ultrastructure, underscoring that TEM alone cannot exclude the diagnosis [

30,

31,

32]. Advances in genetic testing have substantially improved diagnostic yield, and in current practice is increasingly combined with nNO measurement to enable greater recognition of affected children.

History of recurrent and/or chronic ear infections feature frequently in the childhood PCD picture. OME is said to affect almost all PCD patients and, by one report, requires otolaryngologic care in approximately 50% of PCD patients [

33]. Longstanding OME can have lasting consequences of conductive hearing loss, delays in language and speech, and cholesteatoma formation [

34,

35,

36].

In our analysis, 60.3% of children assessed had a history of ear infections, although many studies did not distinguish between AOM, chronic OM, and OME. It is worth noting that dedicated PCD cohorts outside our review have reported near-universal middle ear involvement, suggesting that our pooled estimate likely underrepresents the true prevalence due to incomplete or variable reporting [

10,

37]. Better characterizing diseases of the ear for children with PCD is crucial because of the possible impact on treatment. Patients are sometimes transitioned from discontinuous to continuous antibiotic treatment for symptoms of the ear once a PCD diagnosis is made. However, both continuous antibiotics and TTs were shown in the 2010 study by Prulière-Escabasse et al. to have no impact on the condition of the middle ear in children with PCD [

37]. Their study showed improvements in the middle ear only after the age of eighteen, with continued frequency of OME into the adult years.

In the studies that referenced TT placement, it was noted to be necessary in over half of the cohorts. Proponents argue that TTs in PCD improve long-term hearing and reduce middle ear effusion, which may help prevent delays in speech and language development [

33]. However, the evidence remains limited and several factors complicate decision-making. In otherwise healthy children, guidelines recommend watchful waiting for OME lasting less than 3 months, unless hearing loss or developmental risks are present [

38]. In PCD, effusions and recurrent infections are often more severe and refractory, and children may undergo multiple sets of tubes with higher complication rates [

37,

39,

40]. Reflecting these concerns, the European Respiratory Society Consensus Statement considers otorrhea an unacceptable side effect of TTs, advocating instead for watchful waiting in PCD patients with recurrent ear infections [

37,

41]. Overall, the literature supports offering TTs selectively in PCD when hearing loss, effusion, or other comorbidities are persistent, while emphasizing individualized treatment and consideration of non-invasive alternatives when appropriate. Regardless of these treatment preferences, audiological assessment, speech therapy, and hearing aids should be offered without delay when the need presents, as effectiveness of any of these interventions increases with earlier introduction [

1,

36,

42].

Sinonasal disease is another central concern in childhood PCD. Chronic rhinitis is often one of the first PCD symptoms, presenting soon after birth [

1], and congestion tends to remain the primary sinonasal manifestation throughout childhood, present in 83% of the 47-person cohort in the study by Zawawi et al. [

21]. Nasal polyps, sinus pressure, snoring, and anosmia also afflict many individuals with PCD. These symptoms have a significant negative impact on quality of life (QoL), with the study by Stack et al. reporting a worse sinonasal QoL in PCD patients than in patients with cystic fibrosis [

43].

Treatment consensus for sinonasal symptoms in PCD is less varied than with conditions of the ear, although patient compliance is arguably worse. While sinonasal disease in PCD is sometimes resistant to treatment with traditional therapies, many of the mainstays of treatment for sinonasal inflammation still result in significant improvements with consistent use. Initial approaches to treatment include

nasal steroids, nasal lavage, and short courses of systemic antibiotics during acute exacerbations [

1]

. Regular nasal irrigation is a useful tool in this population, shown to not only improve QoL but also help decrease lower respiratory tract inflammation [

44,

45,

46,

47]. Current recommendations from PCD Clinical Centers of Excellence similar emphasize these strategies, highlighting the importance of consistent nasal lavage and topical therapies as cornerstones of care [

48].

Although sinonasal treatments were detailed in very few studies in our review, nasal steroids and saline spray were the most common management strategies. F

unctional ESS was performed in a small subset of our cohort for nasal polyposis; while less studied in the child and adolescent populations, ESS has been shown to significantly reduce chronic sinonasal symptoms in adult populations [

46,

49,

50,

51]

.

This review has several limitations. By design, we included only cohort studies to ensure a higher level of evidence, but this also introduced gaps where clinical details were incompletely reported. For instance, while nasal polyps are well-recognized in PCD, they were described in only one of the studies in our review [

29,

52]. This discrepancy likely reflects inconsistent reporting rather than true absence, emphasizing how reliance on cohort-level summaries can obscure important manifestations. In addition, many cohorts did not differentiate between types of OM or sinonasal complaints, limiting our ability to stratify outcomes. Diagnostic criteria also varied across studies, ranging from ATS guideline-based approaches to isolated use of TEM or genetic testing, contributing to heterogeneity in case definitions. Finally, patient-level data were generally unavailable, precluding meta-analysis and preventing assessment of factors associated with disease severity or treatment outcomes. These limitations highlight the importance of standardized, prospective, multicenter reporting to better characterize otolaryngologic disease in children with PCD.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the substantial burden of otologic and sinonasal disease in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Ear disease, most often manifesting as chronic otitis media and conductive hearing loss, was reported in the majority of cohorts and frequently required intervention with tympanostomy tubes, hearing aids, or bone conduction devices. Chronic sinonasal symptoms, particularly congestion, rhinorrhea, and sinusitis, were nearly universal, while nasal polyps were less commonly described but clinically significant when present. Vestibular symptoms were infrequently described, though when specifically assessed, abnormalities were identified in a notable proportion of patients.

Despite the frequency and impact of these manifestations, there remains considerable heterogeneity in reporting and limited consensus regarding management strategies. Interventions such as TT and FESS are variably employed, and evidence regarding their long-term benefit in pediatric PCD remains sparse. Early recognition, consistent audiological and sinonasal assessment, and timely initiation of supportive therapies are essential to mitigate the downstream consequences on language, learning, and quality of life.

Future research should emphasize standardized outcomes and quality-of-life measures while also advancing basic science efforts, including gene therapy to restore ciliary function. Such efforts will be critical to establish clinical pathways for the otolaryngologic care of children with PCD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Full database search strategies used in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N., V.A.P., and R.A.S.; methodology, K.N.; software, K.N.; validation, K.N., N.D.B. and A.N.P.; formal analysis, K.N.; investigation, K.N., N.D.B., and A.N.P.; resources, L.E.B.; data curation, K.N. and L.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N., L.E.B., and A.N.P.; writing—review and editing, K.N., N.D.B., A.N.P., L.E.B., V.A.P., and R.A.S.; supervision, V.A.P. and R.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its design as a systematic review of previously published literature. No new data were collected from human participants or animals, and all data included were extracted from studies already in the public domain.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOM |

Acute otitis media |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| ESS |

Endoscopic sinus surgery |

| F |

Female |

| FESS |

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery |

| MeSH |

Medical Subject Headings |

| M |

Male |

| Mo |

Month |

| nNo |

Nasal nitric oxide |

| No. |

Number |

| OM |

Otitis media |

| OME |

Otitis media with effusion |

| PCD |

Primary ciliary dyskinesia |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SNOT-22 |

Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 |

| SN-5 |

Sinus and Nasal Quality of Life Survey |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

| TT |

Tympanostomy tube |

| vHIT |

Video head impulse test |

| Yrs |

Years |

| |

|

References

- Knowles, M.R.; Daniels, L.A.; Davis, S.D.; Zariwala, M.A.; Leigh, M.W. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Recent advances in diagnostics, genetics, and characterization of clinical disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2013, 188, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirra, V.; Werner, C.; Santamaria, F. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: an update on clinical aspects, genetics, diagnosis, and future treatment strategies. Frontiers in pediatrics 2017, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cant, E.; Shoemark, A.; Chalmers, J.D. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: integrating genetics into clinical practice. Current Pulmonology Reports 2024, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, S.; King Jr, T.E.; Hollingsworth, H. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (immotile-cilia syndrome). UpToDate.com.Available online at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-ciliary-dyskinesia-immotilecilia-syndrome (accessed September 8, 2016) 2012.

- Boon, M.; Jorissen, M.; Proesmans, M.; De Boeck, K. Primary ciliary dyskinesia, an orphan disease. Eur.J.Pediatr. 2013, 172, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, V.; Zysman-Colman, Z.; Shapiro, A.J. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Paediatrics & Child Health 2025, pxae102. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M.P.; Noone, P.G.; Leigh, M.W.; Zariwala, M.A.; Minnix, S.L.; Knowles, M.R.; Molina, P.L. High-resolution CT of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am.J.Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.P.; Omran, H.; Leigh, M.W.; Dell, S.; Morgan, L.; Molina, P.L.; Robinson, B.V.; Minnix, S.L.; Olbrich, H.; Severin, T. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation 2007, 115, 2814–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, N.E.; Dell, S.D.; James, A.L.; Campisi, P. Middle ear ventilation in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int.J.Pediatr.Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutaki, M.; Lam, Y.T.; Alexandru, M.; Anagiotos, A.; Armengot, M.; Boon, M.; Burgess, A.; Caversaccio, N.; Crowley, S.; Dheyauldeen, S.A.D. Characteristics of otologic disease among patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2023, 149, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, R.Ö; Eroğlu, E.; Tellioğlu, B.; Emiralioğlu, N.; Özçelik, H.U.; Yalçın, E.; Doğru, D.; Kiper, E.N. Evaluation of otorhinolaryngological manifestations in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int.J.Pediatr.Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 168, 111520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.T.; Papon, J.; Alexandru, M.; Anagiotos, A.; Armengot, M.; Boon, M.; Burgess, A.; Caversaccio, N.; Crowley, S.; Dheyauldeen, S.A.D. Lack of correlation of sinonasal and otologic reported symptoms with objective measurements among patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: an international study. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology 2023, 16, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandru, M.; Veil, R.; Rubbo, B.; Goutaki, M.; Kim, S.; Lam, Y.T.; Nevoux, J.; Lucas, J.S.; Papon, J. Ear and upper airway clinical outcome measures for use in primary ciliary dyskinesia research: a scoping review. European Respiratory Review 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, L.; Dubois, S.; Bricmont, N.; Bonhiver, R.; Seghaye, M.; Lefèbvre, P.; Papon, J.; Kempeneers, C.; Poirrier, A. Clinical Manifestations and Management of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in ENT Practice. B-ENT 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Qian, L. Clinical and genetic spectrum of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in China. J.Pediatr. 2020, 225, 157–165. e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Yang, H.; Yao, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Hao, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Ge, W. Clinical and genetic spectrum of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in China. Chest 2021, 159, 1768–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, M.; Thouvenin, G.; Taytard, J.; Baron, M.; Le Bourgeois, M.; Tamalet, A.; Mani, R.; Jouvion, G.; Amselem, S.; Escudier, E. High nasal nitric oxide, cilia analyses, and genotypes in a retrospective cohort of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2022, 19, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Guo, Z.; Chen, C.; Duan, B.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W. CT imaging features of paranasal sinuses in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Acta Otolaryngol. 2022, 142, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawawi, F.; Papsin, B.C.; Dell, S.; Cushing, S.L. Vestibular and balance impairment is common in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Otology & Neurotology 2022, 43, e355–e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawawi, F.; Shapiro, A.J.; Dell, S.; Wolter, N.E.; Marchica, C.L.; Knowles, M.R.; Zariwala, M.A.; Leigh, M.W.; Smith, M.; Gajardo, P. Otolaryngology manifestations of primary ciliary dyskinesia: a multicenter study. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2022, 166, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseri, A.A.; Shati, A.A.; Asiri, I.A.; Aldosari, R.H.; Al-Amri, H.A.; Alshahrani, M.; Al-Asmari, B.G.; Alalkami, H. Clinical and genetic Characterization of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Southwest Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Children 2023, 10, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, S.M.; Wong, D.; Levi, E.; Robinson, P. Otolaryngological burden of disease in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Victoria, Australia. Int.J.Pediatr.Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 173, 111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, M.; Hong, S.; Yu, J.; Cho, J.; Suh, D.I.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, H.; Jung, S.; Lee, E. Clinical manifestations and genotype of primary ciliary dyskinesia diagnosed in Korea: multicenter study. Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Research 2023, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yang, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Cheng, T.; Liao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, H. Clinical Characteristics and Immune Responses in Children with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia during Pneumonia Episodes: A Case–Control Study. Children 2023, 10, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhonen, E.G.; Zhu, A.; Sempson, S.; Bothwell, S.; Sagel, S.D.; Chan, K.H. Management of middle ear disease in pediatric primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int.J.Pediatr.Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 192, 112297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z.; Yang, H.; Shen, Y. Clinical features and genetic spectrum of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in central China: a referral center retrospective analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 16, 1526675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, I.; Kimple, A.J.; Ferkol, T.W.; Sagel, S.D.; Dell, S.D.; Milla, C.E.; Li, L.; Lin, F.; Sullivan, K.M.; Zariwala, M.A. Progression of Otologic and Nasal Symptoms in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Throughout Childhood. OTO open 2025, 9, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bequignon, E.; Dupuy, L.; Zerah-Lancner, F.; Bassinet, L.; Honoré, I.; Legendre, M.; Devars du Mayne, M.; Escabasse, V.; Crestani, B.; Maître, B. Critical evaluation of sinonasal disease in 64 adults with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Journal of clinical medicine 2019, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, A.J.; Leigh, M.W. Value of transmission electron microscopy for primary ciliary dyskinesia diagnosis in the era of molecular medicine: Genetic defects with normal and non-diagnostic ciliary ultrastructure. Ultrastruct.Pathol. 2017, 41, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theegarten, D.; Ebsen, M. Ultrastructural pathology of primary ciliary dyskinesia: report about 125 cases in Germany. Diagnostic Pathology 2011, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Even Cohn, R.; Amirav, I. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) Registry in Alberta. In C25. Clinical and Translational Studies in Rare Lung Disease; Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) Registry in Alberta; American Thoracic Society, 2019; pp. A4383. pp. A4383.

- Campbell, R. Managing upper respiratory tract complications of primary ciliary dyskinesia in children. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 2012, 12, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagel, S.D.; Davis, S.D.; Campisi, P.; Dell, S.D. Update of respiratory tract disease in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2011, 8, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.J.; Zariwala, M.A.; Ferkol, T.; Davis, S.D.; Sagel, S.D.; Dell, S.D.; Rosenfeld, M.; Olivier, K.N.; Milla, C.; Daniel, S.J. Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of primary ciliary dyskinesia: PCD foundation consensus recommendations based on state of the art review. Pediatr.Pulmonol. 2016, 51, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolter, N.E.; Dell, S.D.; James, A.L.; Campisi, P. Middle ear ventilation in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int.J.Pediatr.Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prulière-Escabasse, V.; Coste, A.; Chauvin, P.; Fauroux, B.; Tamalet, A.; Garabedian, E.; Escudier, E.; Roger, G. Otologic features in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery 2010, 136, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, R.M.; Shin, J.J.; Schwartz, S.R.; Coggins, R.; Gagnon, L.; Hackell, J.M.; Hoelting, D.; Hunter, L.L.; Kummer, A.W.; Payne, S.C. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2016, 154, S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, N.B.; Tamir, S.O.; Gitin, M.; Schwarz, Y.; Marom, T. Contemporary Tympanostomy Tube Complications in Children: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Otology & Neurotology 2025, 10.1097. [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen, T.M.; van der Heijden, G.J.; Freling, H.G.; Venekamp, R.P.; Schilder, A.G. Parent-reported otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: incidence and predictors. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, A.; Frischer, T.; Kuehni, C.E.; Snijders, D.; Azevedo, I.; Baktai, G.; Bartoloni, L.; Eber, E.; Escribano, A.; Haarman, E. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: a consensus statement on diagnostic and treatment approaches in children. European Respiratory Journal 2009, 34, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerman, A.; Bisgaard, H. Longitudinal study of lung function in a cohort of primary ciliary dyskinesia. European Respiratory Journal 1997, 10, 2376–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, T.; Norris, M.; Kim, S.; Lamb, M.; Zeatoun, A.; Mohammad, I.; Worden, C.; Thorp, B.D.; Klatt-Cromwell, C.; Ebert Jr, C.S. Sinonasal quality of life in primary ciliary dyskinesia 2023, 13, 2101.

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Mullol, J.; Bachert, C.; Alobid, I.; Baroody, F.; Cohen, N.; Cervin, A.; Douglas, R.; Gevaert, P. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012 2012.

- Rollin, M.; Seymour, K.; Hariri, M.; Harcourt, J. Rhinosinusitis, symptomatology & absence of polyposis in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Rhinology 2009, 47, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Zou, J.; Liu, S. Endoscopic sinus surgery for treatment of Kartagener syndrome: a case report. Balkan medical journal 2013, 2013, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illing, E.A.; Woodworth, B.A. Management of the upper airway in cystic fibrosis. Curr.Opin.Pulm.Med. 2014, 20, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, A.J.; Zariwala, M.A.; Ferkol, T.; Davis, S.D.; Sagel, S.D.; Dell, S.D.; Rosenfeld, M.; Olivier, K.N.; Milla, C.; Daniel, S.J. Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of primary ciliary dyskinesia: PCD foundation consensus recommendations based on state of the art review. Pediatr.Pulmonol. 2016, 51, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.S.; Greene, B.A. A treatment for primary ciliary dyskinesia: efficacy of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 1993, 103, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantier, D.B.; de Rezende Pinna, F.; Olm, M.A.K.; Athanázio, R.; de Mendonça Pilan, R.R.; Voegels, R.L. Outcomes of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. International archives of otorhinolaryngology 2023, 27, e423–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanin, M.C.; Aanaes, K.; Hoiby, N.; Pressler, T.; Skov, M.; Nielsen, K.G. Sinus surgery can improve quality of life, lung infections, and lung function in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7(3), 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.T.; Papon, J.; Alexandru, M.; Anagiotos, A.; Armengot, M.; Boon, M.; Burgess, A.; Crowley, S.; Dheyauldeen, S.A.D.; Emiralioglu, N. Sinonasal disease among patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: an international study. ERJ Open Research 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).