Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

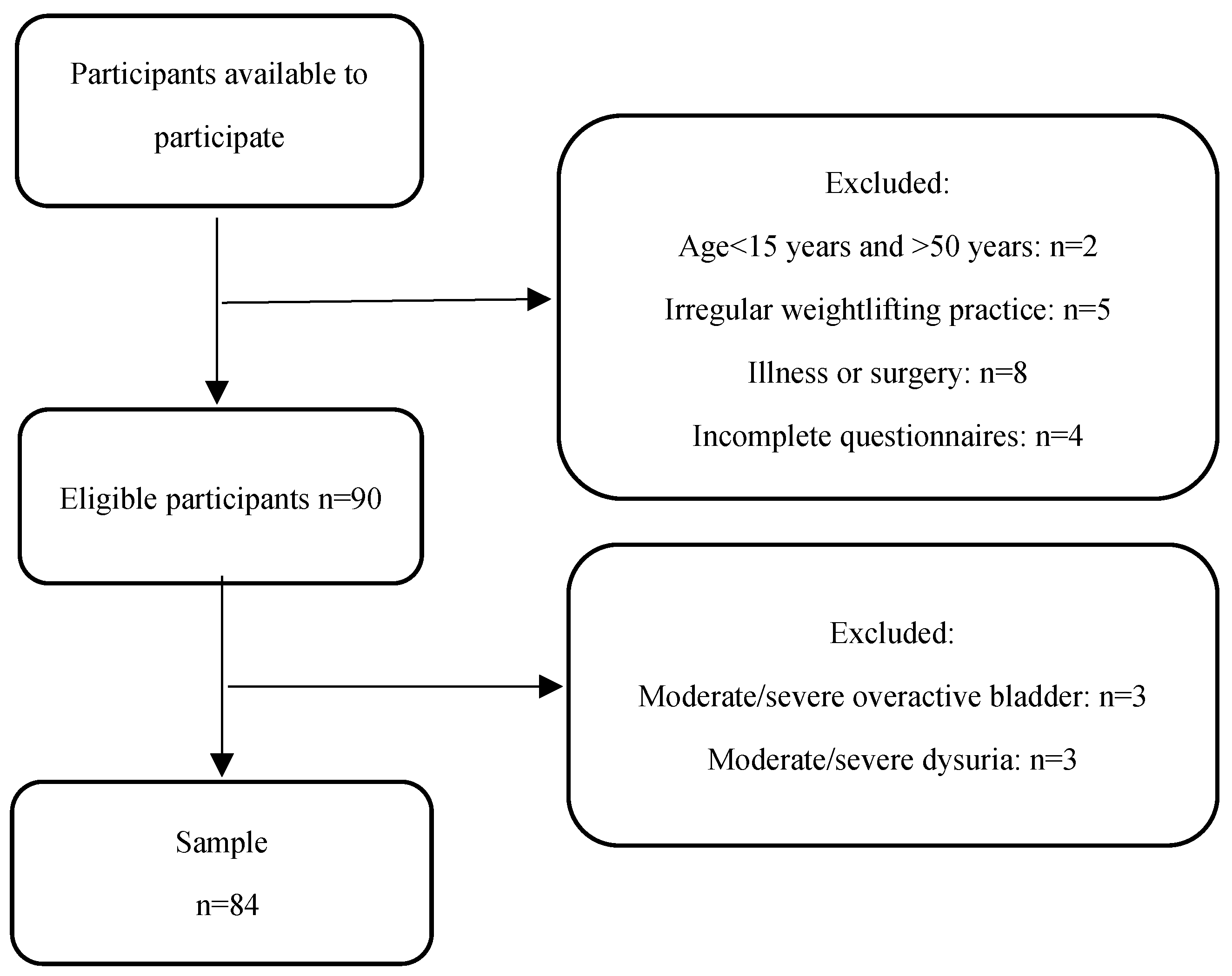

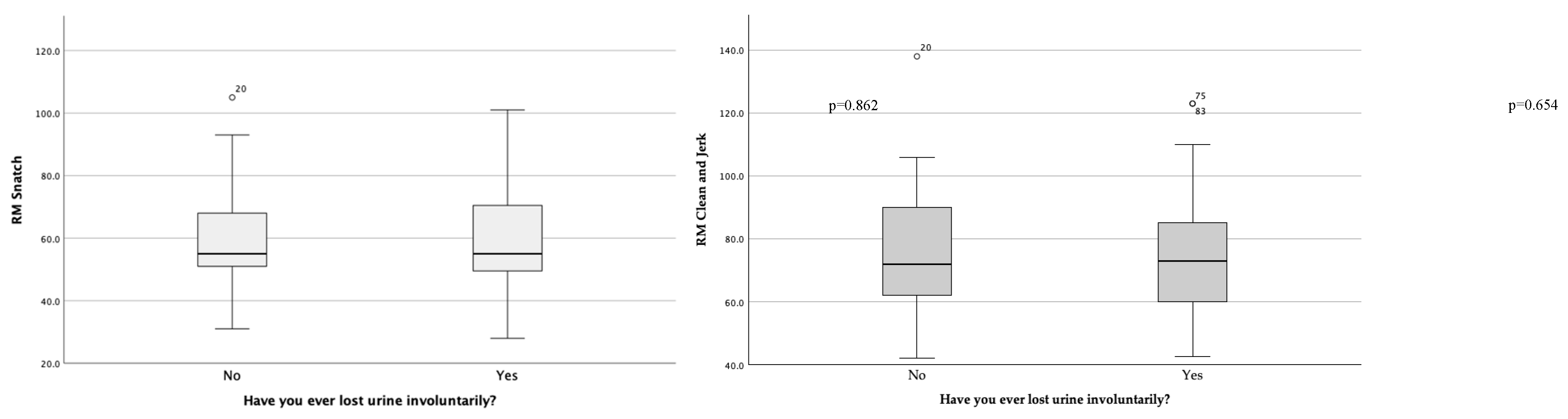

Background/Objectives: Urinary incontinence (UI) is common among women practicing sports, particularly those involving heavy lifting or high-impact movements that increase intra-abdominal pressure. UI can negatively affect social life, self-confidence, and motivation to remain active. This study aimed to examine the associations of sociodemographic, training-related, obstetric and surgical factors with UI in female weightlifters. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 84 French women regularly practicing weightlifting. Participants completed a sociodemographic and gynecological questionnaire, along with the Urinary Symptom Profile (USP). Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U, Student’s t-test, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests (95% confidence level). Results: Among participants (aged 15–49 years), 51 (60.7%) reported involuntary urine leakage, and 31 (36.9%) scored 1–3 on the USP stress incontinence subscale. Most participants were non-smokers (73.8%), with a median of 3.5 years of weightlifting experience, 4 weekly training sessions, and 6–7 competitions per year. No significant associations were found between UI and sociodemographic factors, obstetric history, previous surgeries, or training characteristics. Maximal lifts in Clean & Jerk and Snatch exercises were also similar between participants with and without UI. Slight trends suggested higher UI prevalence among women with vaginal deliveries, episiotomies, or vaginal lacerations. Conclusions: UI is common among female weightlifters, but in this study, was not associated with sociodemographic factors or weightlifting practices. These findings indicate that UI prevalence cannot be explained by the variables studied and highlight the need for further research into other potential contributing factors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002, 187, 116-126. [CrossRef]

- Grimes, W.R.; Stratton, M. Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing.

- In Copyright © 2025; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025; 3. Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Linde, J.M.; Nijman, R.J.M.; Trzpis, M.; Broens, P.M.A. Urinary incontinence in the Netherlands: Prevalence and associated risk factors in adults. Neurourol Urodyn 2017, 36, 1519-1528. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Brown, H.W.; Brubaker, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Daly, J.O.; Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17097. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, S.W.; Tran, L.N.; Puckett, Y. Urinary Incontinence. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Pierce, H.; Perry, L.; Gallagher, R.; Chiarelli, P. Pelvic floor health: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2015, 71, 991-1004. [CrossRef]

- Cacciari, L.P.; Dumoulin, C.; Hay-Smith, E.J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: a cochrane systematic review abridged republication. Braz J Phys Ther 2019, 23, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- Raizada, V.; Mittal, R.K. Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2008, 37, 493-509, vii. [CrossRef]

- Eickmeyer, S.M. Anatomy and Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2017, 28, 455-460. [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, R.P.; Colla, C.; Darski, C.; Paiva, L.L. Influence of pelvic floor muscle fatigue on stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2018, 29, 197-204. [CrossRef]

- de Mattos Lourenco, T.R.; Matsuoka, P.K.; Baracat, E.C.; Haddad, J.M. Urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2018, 29, 1757-1763. [CrossRef]

- Jacome, C.; Oliveira, D.; Marques, A.; Sa-Couto, P. Prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence among female athletes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011, 114, 60-63. [CrossRef]

- Storey, A.; Smith, H.K. Unique aspects of competitive weightlifting: performance, training and physiology. Sports Med 2012, 42, 769-790. [CrossRef]

- Karkos, P.; Kuśmierczyk, K.; Jurga, M.; Gastoł, B.; Mikołap, K.; Kras, M.; Staroń, A.; Sztemberg, E.; Plizga, J.; Głuszczyk, A. Application of the Valsalva maneuver in medicine and sport. Quality in Sport 2024, 20, 53363. [CrossRef]

- Bo, K.; Nygaard, I.E. Is Physical Activity Good or Bad for the Female Pelvic Floor? A Narrative Review. Sports Med 2020, 50, 471-484. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Sapsford, R.; Pengel, L.H. Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. Neurourol Urodyn 2007, 26, 362-371. [CrossRef]

- Ashton-Miller, J.A.; DeLancey, J.O. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1101, 266-296. [CrossRef]

- Wikander, L.; Kirshbaum, M.N.; Waheed, N.; Gahreman, D.E. Urinary Incontinence in Competitive Women Powerlifters: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Sports Med Open 2021, 7, 89. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I.; Girts, T.; Fultz, N.H.; Kinchen, K.; Pohl, G.; Sternfeld, B. Is urinary incontinence a barrier to exercise in women? Obstet Gynecol 2005, 106, 307-314. [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, F.; Oskouei, A.E. Physiotherapy for women with stress urinary incontinence: a review article. J Phys Ther Sci 2014, 26, 1493-1499. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.L.; Miller, L.D.; Mishra, K. Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2019, 31, 485-493. [CrossRef]

- Da Roza, T.; Natal Jorge, R.; Mascarenhas, T.; Duarte, J. Urinary Incontinence in Sport Women: from Risk Factors to Treatment – A Review. Current Women s Health Reviews 2013, 9, 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Waetjen, L.E.; Ye, J.; Feng, W.Y.; Johnson, W.O.; Greendale, G.A.; Sampselle, C.M.; Sternfield, B.; Harlow, S.D.; Gold, E.B. Association between menopausal transition stages and developing urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2009, 114, 989-998. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004, 36, 674-688. [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations. Sports Med 2018, 48, 765-785. [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Agarwal, P.; Verma, M.L.; Dalela, D.; Singh, N.; Shankhwar, P. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence in Indian women: A hospital-based survey. Indian J Urol 2013, 29, 31-36. [CrossRef]

- Seret, R.; Launois, C.; Barbe, C.; Larre, S.; Léon, P. Évolution du score USP et IPSS après appareillage du syndrome d’apnées du sommeil par pression positive continue nocturne. Progrès en Urologie 2022, 32, 130-138, doi:. [CrossRef]

- Haab, F.; Richard, F.; Amarenco, G.; Coloby, P.; Arnould, B.; Benmedjahed, K.; Guillemin, I.; Grise, P. Comprehensive evaluation of bladder and urethral dysfunction symptoms: development and psychometric validation of the Urinary Symptom Profile (USP) questionnaire. Urology 2008, 71, 646-656. [CrossRef]

- Wikander, L.; Kirshbaum, M.N.; Waheed, N.; Gahreman, D.E. Urinary Incontinence in Competitive Women Weightlifters. J Strength Cond Res 2022, 36, 3130-3135. [CrossRef]

- Huebner, M.; Ma, W.; Harding, S. Sport-related risk factors for moderate or severe urinary incontinence in master female weightlifters: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0278376. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, X.; Jia, G.; Jiang, H. Risk Factors for Postpartum Stress Urinary Incontinence: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Reprod Sci 2020, 27, 2129-2145. [CrossRef]

- Feldner, P.; Bezerra, L.; Girão, M.; Castro, R.; Sartori, M.; Chada, B.; de, L. Correlação entre a pressão de perda à manobra de Valsalva e a pressão máxima de fechamento uretral com a história clínica em mulheres com incontinência urinária de esforço. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia 2002, 24. [CrossRef]

| n (%) | Median [P25-P75] | |

| Age (years) | 27.0 [24.0-33.0] | |

| Weight (kg) | 64.0 [57.3-72.8] | |

| Height (cm) | 163.5 [158.5-169.0] | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 [21.7-26.5] | |

| Time spent weightlifting (years) | 3.5 [2.0-6.0] | |

| Number of training sessions per week | 4.0 [3.0-5.0] | |

| Number of competitions per year | 6.5 [4.0-8.0] | |

| RM Clean and Jerk (kg) | 72.5 [60.0-86.8] | |

| RM Snatch (kg) | 55.0 [49.3-70.0] | |

| Number of births | 22 (26.2) | |

| Vaginal birth | 19 (22.6) | |

| Cesarean birth | 6 (7.1) | |

| Episiotomy | 8 (36.4) | |

| Manual intervention | 4 (31.8) | |

| Vaginal lacerations | 11 (50.0) | |

| Non-smoker | 62 (73.8) | |

| Smoker | 9 (10.7) | |

| Nº of cigarettes/week | 49.0 [28.0-70.0] | |

| Years of smoking | 7.0 [5.0-15.0] | |

| Ex-smoker | 13 (15.5) | |

| Nº of cigarettes/week | 70.0 [28.0-102.0] | |

| Years of smoking | 7.0 [6.0-10.5] | |

| Time since abstinence from tobacco (years) | 5.0 [2.0-12.5] |

|

With UI (n =51) |

Without UI (n = 33) |

p | |

| n (%) | |||

| Age (years) (n=84) | |||

| 15-24 | 15 (17.8) | 11 (13.1) | 0.143a |

| 25-44 | 33 (39.3) | 22 (26.2) | |

| 45-50 | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n=84) | |||

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0.086b |

| 18.5-24.9 (normal weight) | 30 (35.7) | 23 (27.4) | |

| 25-29.9 (pre-obesity) | 15 (17.8) | 5 (5.9) | |

| ≥ 30 (obesity) | 5 (6.0) | 3 (3.6) | |

| Daily water consumption (L) (n=84) | |||

| < 1.75 | 23 (27.4) | 19 (22.6) | 0.148b |

| 1.75-2.5 | 17 (20.2) | 9 (10.7) | |

| >2.5 | 11 (13.1) | 5 (6.0) | |

| Smoking habits (n=84) | |||

| Non-smoker | 38 (45.2) | 24 (28.5) | 0.945c |

| Ex-smoker | 8 (9.5) | 5 (6.0) | |

| Smoker | 5 (6.0) | 4 (4.8) | |

| Time in practice (years) (n=84) | |||

| < 2 | 7 (8.3) | 2 (2.4) | 0.796b |

| 2-5 | 24 (28.6) | 21 (25.0) | |

| ≥ 5 | 20 (23.8) | 10 (11.9) | |

| Nº of training sessions/week (n=84) | |||

| < 3 | 8 (9.5) | 5 (6.0) | 0.167b |

| 3-4 | 29 (34.5) | 11 (13.1) | |

| ≥ 5 | 14 (16.7) | 17 (20.2) | |

| Nº of competitions/year (n=84) | |||

| < 5 | 14 (16.7) | 7 (8.3) | 0.128a |

| 5-10 | 24 (28.6) | 16 (19.0) | |

| ≥ 10 | 13 (15.5) | 10 (11.9) | |

| Use of a powerlifting belt (n=44) | 26 (59.0) | 18 (41.0) | 0.749c |

| Breathing phase during load lifting (n=72) | |||

| Expiration | 16 (22.2) | 13 (18.1) | 0.381c |

| Inspiration | 10 (13.9) | 7 (9.7) | |

| Apnea | 15 (20.8) | 11 (15.3) | |

| Number of births (n=22) | |||

| 1 | 7 (31.8) | 3 (13.7) | 0.810a |

| 2 | 9 (41.0) | 1 (4.5) | |

| 3 | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Vaginal birth (n=19) | 15 (79.0) | 4 (21.0) | 0.953a |

| Cesarean birth (n=6) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0.480b |

| Episiotomy (n=8) | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0.613c |

| Manual intervention (n=4) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1.000c |

| Vaginal lacerations (n=11) | 10 (91.0) | 1 (9.0) | 0.311c |

| Pelvic surgery (n=8) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0.471e |

| Abdominal surgery (n=8) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 1.000e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).