1. Introduction

To date, there is no consensus on the underlying cause of insulin resistance (IR) in the pathogenesis of internal organ diseases [

1,

2]. Some authors believe that IR develops first, followed by other syndromes and diseases, such as hyperinsulinemia (HI), type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [

3,

4]. Authors suggest that IR is a fundamental pathophysiological defect in the development of T2DM and leads to compensatory HI to maintain normal glucose tolerance [

5]. These authors believe that hereditary predisposition to IR and obesity in combination with low physical activity [

6], and overnutrition determine the development of tissue IR and, as a consequence, compensatory HI [

7,

8].

In 1988, G. Reaven first suggested that many chronic diseases are based on decreased tissue sensitivity to insulin [

9]. Since then, numerous studies of IR have defined it as a continuum of cardiovascular, endocrinological, nephrological, and hepatological diseases [

10,

11]. Other studies showed that abdominal obesity is a cause of IR. High concentrations of free fatty acids secreted by adipocytes in visceral adipose tissue directly into the hepatic portal vein suppress insulin uptake by the liver, leading to IR [

12]. Isolated interventions for IR have been used for over 30 years and have shown improvement in metabolic parameters in patients with T2DM, but this has not solved the main problem – curing diabetes itself [

1,

13]. The authors also showed a simultaneous association of IR with markers of glycemic, cardiometabolic, and atherosclerotic risk in individuals who were not obese or prediabetic [

14]. Some researchers proved that when the amount of fat in the body decreases, IR disappears [

15,

16].

Long-term insulin therapy for T2DM sooner or later leads to a decrease in the synthesis of an already relatively insufficient amount of endogenous insulin, which aggravates IR, leading to an increase in the dose of exogenously administered insulin [

17,

18].

In 1993, G.M. Reaven proposed renaming metabolic syndrome as “syndrome X” given the uncertainty regarding the primacy of the components of metabolic syndrome. [

19] The term "IR" continues to stimulate thinking based on disease and the primacy of pathological processes. Many authors have shown that if a person is overweight, over time, impaired glucose tolerance develops, followed by the manifestation of T2DM [

20,

21]. However, the causal relationships between IR and T2DM and other non-communicable chronic diseases remain unclear [

22].

T2DM is usually accompanied by overweight, although within the disease, weight loss tends to decrease somewhat over time [

23]. What explains the fact that simple targeted weight loss leads to normalization of IR and blood sugar levels in T2DM, and what pathophysiological mechanisms are involved? [

24,

25,

26] What pathophysiological processes occur in cells when they oversaturated with nutrients? The aim of the study was to study the comparative effects of three main weight loss methods on IR: pharmacological, bariatric surgery and very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) in patients with T2DM and hypertension.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

A 90-day open label, prospective, multicenter, comparative clinical trial with the intention-to-treat analysis. Based on the results of a clinical trial and a literature review, a concept for the development of IR in T2DM associated with overweight dysfunction was developed.

2.2. Participants

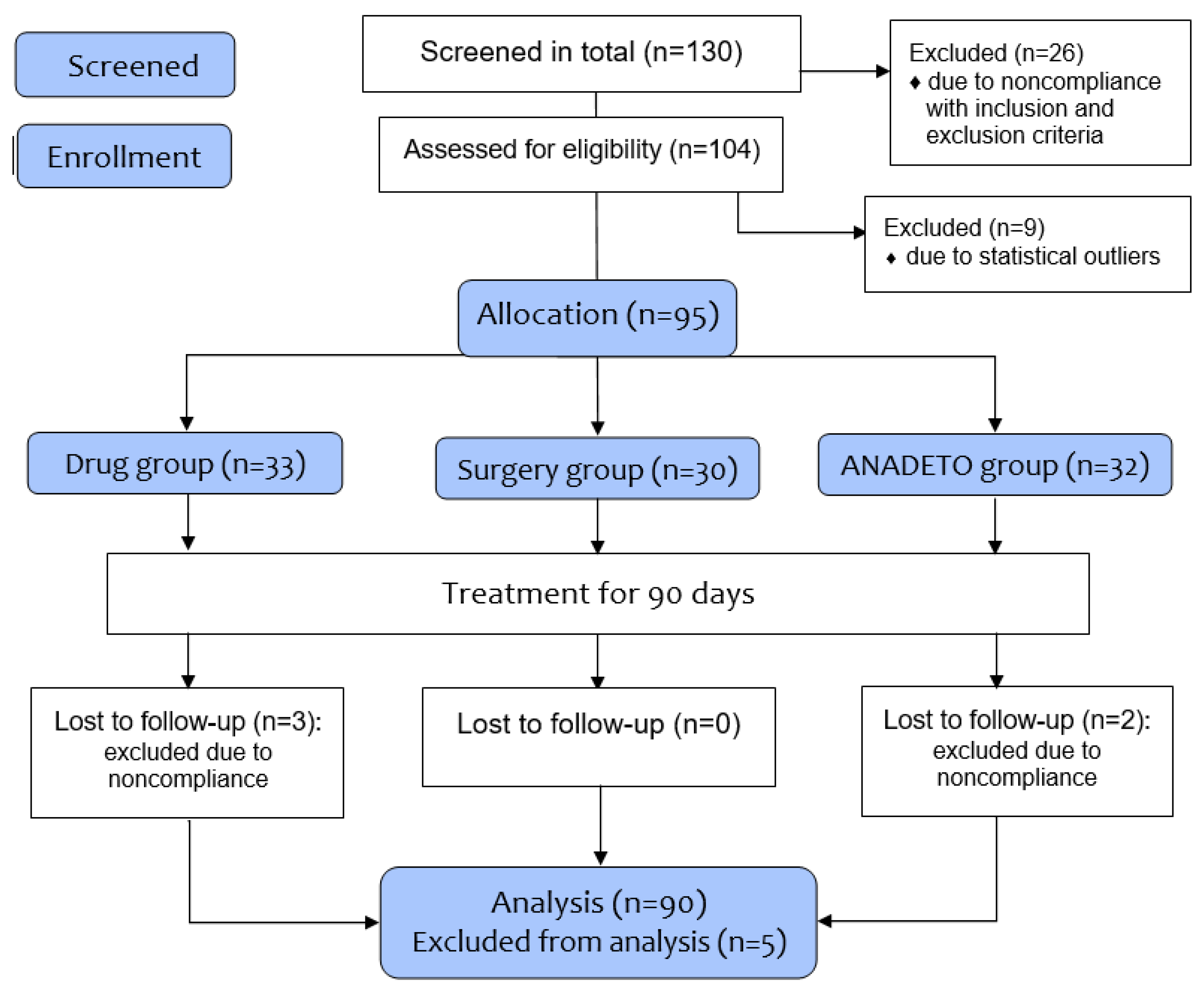

130 participants screened, and 104 adults (63 females) aged 30 to 60 years with T2DM and hypertension were included in the study to determine eligibility; 26 were excluded due to the inclusion/exclusion criteria as described below; nine patients were excluded due to statistical outliers. (

Figure 1) The remaining 95 patients were unevenly and voluntarily allocated into three groups: Drug group (pharmacological); Surgery group (bariatric surgery); and VLCD. Of these patients included in the treatment groups, five patients (three from drug group and two from VLCD group) excluded due to noncompliance and drug intolerance. Finally, 90 patients (86% from 104 patients) were included in the study for analysis.

Inclusion criteria: 1) written informed consent; 2) T2DM ≥3-year with glucose lowering therapy including insulin; 3) hypertension ≥3 years of treatment; 4) 30-60 years old; 5) BMI≥27 kg/m2 for both sexes, for Asian ethnicity; 6) weight loss at baseline. All included patients before recruiting to the study received standard-of-care treatment for T2DM and hypertension [

27].

Exclusion criteria: 1) T1DM; 2) <30 age >61 years old; 3) patients after bariatric surgery; 4) unstable cardiac disorders (New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, refractory angina, uncontrolled arrhythmias, critical valvular heart disease, or severe uncontrolled hypertension); 5) glomerular filtration rate <40 mL/min and/or dialysis within 14 days before screening; 6) ejection fraction <40%; 7) history of alcohol consumption >30 g/day within the past 3 years; 8) malignancy within the past 5 years; 9) gestation or lactation; 10) hereditary diseases; 11) known hypersensitivity to any of the test substances.

Outcome measures. Primary endpoints: The Homeostasis Model Assessment of insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR), blood insulin, weight loss; HbA1c; fasting blood glucose. Secondary endpoints: systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP); lipids.

Patient recruitment and randomization. Patient recruitment was carried out at three different clinical centers (Department for Internal medicine, Center for Endocrinology Center for Surgery). The patients were then consulted by two doctors (a surgeon and a therapist) so that the patient could choose the type of treatment that was right for him/her. Each patient was informed of the pros and cons of each treatment method. After assessing their condition and meeting all indications/contraindications, as well as inclusion/exclusion criteria, they were referred to the appropriate center for the appropriate weight loss treatment. Randomization and blinding of patients in the study were not possible due to its design. The comparative methods involve different interventions, patient allocation cannot be done ethically, informed consent cannot be concealed; results may not always correspond to the results of the comparative treatments; randomization requires clinical equipoise [

28,

29].

The patients were allocated to each group based on equal baseline characteristics according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, including adjustments for baseline and confounding characteristics. The patients were allocated to each group based on the decision of the patient and two physicians (a surgeon and a therapist) to avoid the risk of "selection bias". Parameter normalization focused on the work needed to integrate processes into statistics.

The data were collected by three different research teams, who had no access to patient data other than their own. All data (anthropometric, body composition analysis, clinical, laboratory, instrumental data) were collected in the same place. Laboratory technicians, instrument specialists, and statisticians were blinded to the group(s) to which the patient belonged. The statistician could only work with the data across all study groups once, when all the data had been collected and the database was locked, and only then could we break the code and see which treatment was best. All tests were performed in the same clinical laboratory, certified and accredited according to international quality management systems. A combination of in-person conversations and telephone calls conduct during the study period.

Definition of the term "overweight dysfunction". Lipids in the body perform various functions, such as an energy source, a shock-absorbing cushion for organs, an insulating function, a fat depot, and the adsorption of various substances. [

30,

31].

Excess weight is a component of lipids, which are stored as fat. The primary role of overweight is to serve as energy source in the absence of available food. Consequently, overweight dysfunction occurs when the body does not utilize fat for a long period of time, which leads to the interference of this fat in the body's metabolic processes [

32].

Interventions. (

Figure 1)

Drug group (n=30) received subcutaneous Semaglutide (GLP-1RA) 1 mg once a 7 day with oral Empagliflozin (SGLT-2i) 25 mg once a day additionally to standard medical treatment (metformin, sulfonylureas), including antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and symptomatic therapy; a typical low-carbohydrate, low-salt diet with an emphasis on nutrient-rich, high-fiber foods that help regulate blood sugar levels, promote satiety, and minimize gastrointestinal side effects [

26].

Surgery group (n=30) received a laparoscopic minigastric bypass (MGB) that is endo-videoscope techniques with the intraperitoneal using of synthetic/biological materials to reduce the absorption surface of the gastrointestinal tract by shunting the greater part of the stomach, the duodenum and the initial section of the small intestine, which reduces the absorption of food and leads to a decrease in the production of gastrointestinal hormones [

24].

These patients pass through additional pre-operation examination (blood tests and electrocardiography, esophagogastroscopy, ultrasound, and other necessary standard methods

). Postoperative management of the patients was carried out in accordance with traditional recommendations [

24,

33]

.

VLCD group (n=30) received a weight loss program named ‘Analimentary-detoxication’ (ANADETO; invention patents: a patent of the Republic of Kazakhstan #RK32138; Eurasian patent #EA020034) including <100 kcal/day with fat-free vegetables/greens (tomato/cucumber, dill, parsley, green onions, lemon 15-20 g/day in various combinations) and salt intake (5-6 g/day), optimal physical activity (>7000 steps per day), and sexual self-restraint. [

34] The ANADETO weight loss program was administered twice over a 90-day period.

The program

is aimed at the following outputs: a) use of own fatty store (autolipophagy

); b) control endogen metabolic

intoxication; c) reuse of interim metabolic substrates. During the 90-day treatment, the following regimen was used: the first 30 days – ANADETO; the second 30 days – a 20:4 intermittent fasting protocol [

35] for maintain the achieved weight during the first ANADETO; the third 30 days – also ANADETO.

Due to the presence of many known contraindications to the use of the drugs and surgical intervention, the pharmacologic and surgery groups included patients with a milder clinical and laboratory course of the diseases, but baseline body weight, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, and HbA1c did not differ significantly between the comparison groups [

36]. (

Table 1).

2.3. Analytical Assessment

Anthropometrical indicators included age (years), weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2), waist circumference (cm). Body composition parameters including fat mass (in % of total body weight), fat free mass, total body water, muscle mass, bone mass were measured using a Tanita MC-780MA Body Composition Analyzer (Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Physical activity was assessed as the number of steps taken by patients, as determined by individual pedometers from Roche (Switzerland) or other individual digital system.

Laboratory study.On the same blood samples, standard laboratory a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urea, creatinine, glucose, electrolytes, HbA1c, lipid profile (total-cholesterol, HDL/LDL, triglycerides), total proteins, bilirubin, hepatic enzyme activities.Hormones assay. Fasting serum insulin was determined electrochemiluminescence immunoassay “ECLIA” method (Roche diagnostics, GmbH, Cobas®, Elecsys Insulin kit, US). The value was expressed as nU/L, and hyperinsulinemia was considered >12.5 nU/L.

HOMA-IR was used as surrogate measure of insulin sensitivity as follows: HOMA-IR = ((fasting insulin in nU/L) × (fasting glucose in mmol/L)/22.5). Early insulin resistance was considered if the index was >2, and significant insulin resistance if >2.9.

Imaging. Ultrasound imaging (GE Vivid 7 Ultrasound; GE Healthcare Worldwide USA, Michigan) used for abdominal organs and kidneys.

We carried out main anthropometrical, laboratory, and instrumental examinations three times: at baseline, 30 days, and 90 days.

Criteriafor the diagnosis. Diagnosis of T2DM according to the criteria of World Health Organization and International Diabetes Federation (WHO/IDF consultation in 2006) [Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation. Geneva, Switzerland, 2006]: HbA1c≥6.5% (47.5 mmol/mol), fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, or a patient receives antidiabetic therapy [the American Diabetes Association, 2023]. Hypertension: systolic-BP≥130 and/or their diastolic-BP≥90 mm.Hg following repeated examination, or a patient receives antihypertensive drugs.

2.4. Statistics Justification of the Sample Size

The estimated treatment difference between comparison groups was set to 10% with a standard deviation of 8% and the superiority margin of 2.5% (δ=0.025) based on two-sided hypothesis testing. Using SPSS,Sample-Power,V23.0, the number of evaluable individuals needed per treatment arm ≥20. At least 130 patients we screened and recruited (including nine patients excluded due to statistical outliers), and 95 patients were assessed for eligibility in the comparative clinical trial (

Figure 1). We used two-sided Student’s t tests with Bonferroni correction (P-value/2); where P values of <0.025 were set as significant differences in intra groups, and <0.025 between groups to compensate for the small number of the groups. The study used SPSS Statistics v23 (SPSS Inc., Illinois, USA) and Microsoft Excel-2023 with normality assessed using histograms and box plots. Given the pilot nature of the study and firm hypotheses, were used. The study data is presented in Tables as Mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (M±SEM) for normally distributed data. All analyses were intention-to-treat.

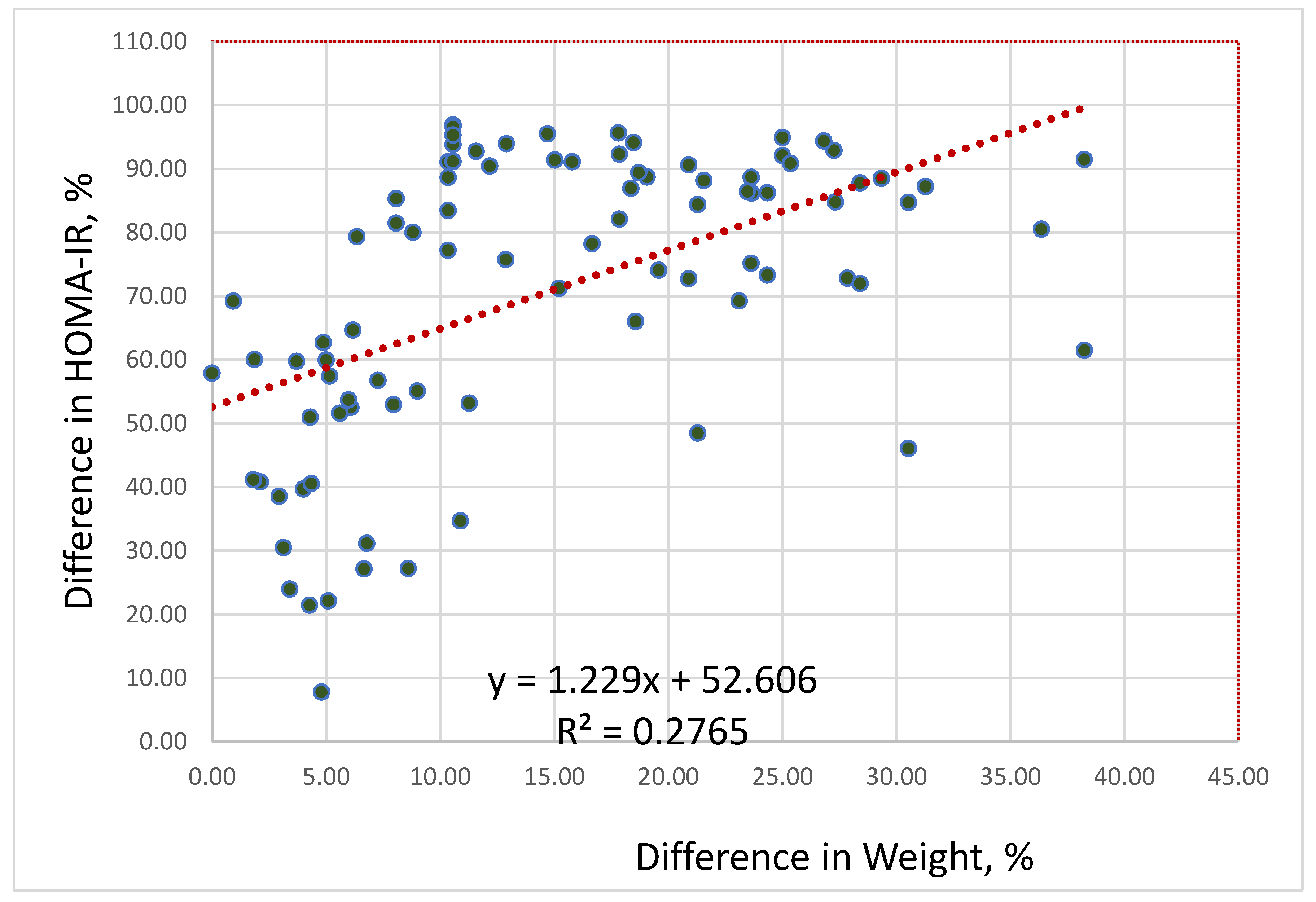

Correlation-regression analysis was used to find statistical relationship between body weight and HOMA-IR levels before and after the intervention (in percent); it quantifies how changes in one variable correspond to changes in another, indicating the direction and strength of their relationship, including determining of the type of correlation, such as positive (variables change in the same direction), negative (variables change in opposite directions), or no correlation (no apparent relationship).

We used electronic databases (Web of Science/ Medline, PubMed, Scopus/Science Direct, Google Scholar, EBSCO/Medline Complete, EndNoteClick/Kopernio, and Ovid/Wolter Kluwer, BMJ) for finding research literature.

3. Results

In

Table 1 are presented the treatment results of patients in the three comparative groups at baseline and 90 days of weight loss. Body weight decreased significantly in Surgery group (-19.8%;

P<0.0001) and VLCD group (-17.4%;

P<0.0001), while in Drug group the decrease was unsignificant (-6.5%;

P=0.06). The decrease in body weight in all comparison groups occurred due to both fat and lean mass. In Surgery and VLCD groups, the decrease in fat mass from baseline was significantly by -29.4% (

P<0.0001) and 31.3% (

P<0.0001), respectively. Fat free mass also decreased significantly from baseline in Surgery by -11.7% (

P=0.008), but not significantly in VLCD groups by -7.3% (

P=0.06).

FBG decreased in Drug group by -23.2% (P=0.0002), in Surgery group by -46.5% (P<0.0001), and in VLCD group by -46.4% (P<0.0001). HbA1c non-significantly decreased in Drug group by -8.4% (P=0.045), significantly decreased in Surgery group by -28.4% (P<0.0001), and significantly decreased in VLCD group by -36.9% (P<0.0001).

HOMA-IR improved significantly in all groups: in Drug group decreased by -42.2% (

P=0.004); in Surgery group by -87.6% (

P<0.0001), and in VLCD group by -88.7% (

P<0.0001), but in Drug group HOMA-IR did not reach the normal level (

Table 1).

Lipids improved significantly in Drug group (-8.7% for cholesterol, P=0.004; -17.3% for triglycerides, P=0.005; +12.2% for HDL, P=0.036), in Surgery group (-17.4% for cholesterol, P<0.0001; -37.7% for triglycerides, P<0.0001; +21.6% for HDL, P=0.002), and in VLCD group (-23.3% for cholesterol, P<0.0001; -64.5% for triglyceride, P<0.0001; +55.6% for HDL, P<0.0001).

Blood hemoglobin in Drug group changed insignificantly (+0.5%, P=0.42), in Surgery group it significantly decreased (-12.7%, P<0.0001), but in VLCD group blood hemoglobin significantly increased (+10.7%, P<0.0001).

SBP in Drug group significantly decreased by -9.5% (P=0.0002), but DBP non-significantly decreased by -4.1% (P=0.09). In Surgical group SBP/DBP significantly decreased by -13.6% (P<0.0001) and by -10.6% (P=0.001), respectively. SBP/DBP in VLCD group significantly decreased by -23.3% and 21.3%, respectively (P<0.0001).

In all three compared groups, HOMA-IR decreased during weight loss. We conducted a regression analysis to identify a statistical relationship between weight loss changes and HOMA-IR. Regression analysis of the differences in percent between changes in body weight and HOMA-IR before and after interventions revealed a strong direct positive correlation between weight loss and decreasing HOMA-IR (r=0.526; F=33.2,

P<0.0001): the greater the weight loss, the lower the HOMA-IR (

Figure 2).

According to the data, HOMA-IR positively correlates with weight loss. As a result of regression analysis, the following association was revealed: if body mass decreases by 10%, then HOMA-IR decreases by 65%; if body mass decreases by 25%, then HOMA-IR decreases by 82.6%.

Patients in groups which significantly weight lost (-19.8% from baseline in Surgical and -17.4% in VLCD groups) antidiabetic and antihypertensive medications gradually reduced and discontinued during the first month after baseline due to improvements in metabolic and cardiovascular health. This effect lasted for the remaining two months without laboratory and clinical signs of T2DM and hypertension. Patients in Drug group were unable to reduce the dosage of their previously taken medications within 90 days.

Side effects in VLCD group were: dizziness, weakness, fasciculation in the lower extremities and abdominal area, psychological discomfort in the first 2-5 days of weight loss; on 3-10 days of the weight loss the urines became turbid and dark (urine microscopy revealed the presence of organic salts, such as oxalates/urates/ phosphates/carbonates of calcium/magnesium); an increase in body temperature to 38oC was about a half of the patients; an increase in sputum expectoration in 2-3 times more than usually and looseness and diarrhea.

4. Discussion

The study presented positive results of three weight loss methods during 90 days to identify the comparative effects of pharmacologic (semaglutide+ empagliflozin), bariatric surgery (endoscopic mini-gastro bypass), and VLCD (analimentary detoxication) on glycemic and other metabolic parameters in patients with T2DM and hypertension. The weight loss interventions resulted in significant reductions in all glycemic parameters (FBG, HBA1c, insulin) and improvements in lipid (cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL) and blood pressure (SBP and DBP) parameters.

The Surgery and VLCD groups showed a significant reduction in body fat mass compared to baseline. However, they also showed a decrease in lean body mass compared to baseline. In Drug and VLCD groups, fat free mass decreased insignificantly. Muscle loss during weight loss is often due to catabolic processes; for example, this was clearly noticeable in the surgical group, as they also experienced blood hemoglobin loss. This group often has contraindications to effective exercise after surgery [

37].

When a person loses weight, they typically lose both fat mass (around 60-80% of the total loss) and fat free mass (muscle, water, bone mass) (around 20-40%) [

38]. A decrease in fat mass is generally accompanied by a decrease in lean mass, and a contributing factor is that the body no longer requires the extra muscle mass to support the lost excess weight. A fatty body requires more muscle and energy for daily activities. The body needs protein to maintain muscle mass and other organs during starvation. The body can use sagging skin as a protein and fuel source during prolonged fasting through a process called autophagy [

39].

In VLCD group blood hemoglobin increased whilst they also lost lean mass. Some other studies confirm that weight loss by intermittent fasting results to increase hemoglobin, and bone mineral density [

40]. Blood hemoglobin differently changed in the groups: in Drug group it did not change significantly; in Surgery group it significantly decreased; in VLCD group it significantly increased. The decrease in blood hemoglobin (anemia) is a common and often delayed consequence after reconstructive bariatric surgery, which alters the anatomical structures responsible for iron metabolism in the body [

41].

Calorie restriction can degrade of endogenous protein-conjugated substrates in different compartments in the body [

42]. Some studies showed that autophagic proteolysis with lysosomal degradation significantly improved the liver and kidney functions, increased blood hemoglobin [

43,

44,

45]. Nutrient deprivation or dietary restriction confers protection against ageing and stress in many animals and induced lysosomal autophagy is part of this mechanism.

IR parameter was improved significantly in all compared groups because it depended on weight loss. Regression analysis showed that the greater the weight loss, the lower the HOMA-IR: if body weight decreased by 10%, then HOMA-IR decreased by 65%; if body mass decreased by 25%, then HOMA-IR decreased by 83%.

The more weight was lost, the better the glycemic data and blood pressure were reduced, lipids were also improved (cholesterol and triglyceride were reduced, HDL was increased). Significant improvements in these parameters were clearly observed in Surgery and VLCD groups, i.e. the greater the weight loss, the better these parameters were. Although Surgery group had the most significant weight loss (-19.8%), anabolic parameters (HDL and blood hemoglobin) were clearly impaired compared to other groups, especially in VLCD group. For example, HDL and blood hemoglobin levels increased in VLCD group.

The weight loss interventions had antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering effects, and their effectiveness depended on the level of weight loss.

When insulin-dependent cells deposit excess lipids, their volume increases due to functional hypertrophy (cell enlargement) [

46]. Enlarged cells lead to external compression of blood vessels and circulatory disorders [

47]. An increase in the cell radius correspondingly increases the path of delivery of oxygen and nutrients from the membrane surface to the center of the cell. To prevent the creation of conditions for the emergence of necrotic processes in the center of the cell (the part furthest from the membrane surface), the transport systems of the cytoplasm will work at the limit of their capabilities, providing this hard-to-reach area with the necessary metabolites [

47,

48].

The physiological reserves of enlarged cells are reduced, so over time, the entire cell begins to experience a deficiency in synthetic, regulatory, and excretory functions. Ultimately, enlarged adipocytes (hypertrophy cells) lose their functional adaptive value and cease to be useful for the body [

2].

Overweight leads to depletion of the pancreatic islet system because the β-cells cannot secrete insulin sufficiently to compensate for the excess weight, and diabetes symptoms worsen [

49]. A relative insulin deficiency occurs. After excess weight is lost, the cells' response to insulin returns to normal [

50]. The HI observed in obesity is a secondary phenomenon. Weight loss leads to subsequent normalization of blood glucose and insulin levels in patients with T2DM [

24,

25].

Insulin synthesis in obesity usually increases proportionally to body weight [

51]. Gradually, the body's compensatory resources are depleting, and its additional synthetic and elimination functions, designed to regulate metabolism in excess biological tissues, are reducing [

52].

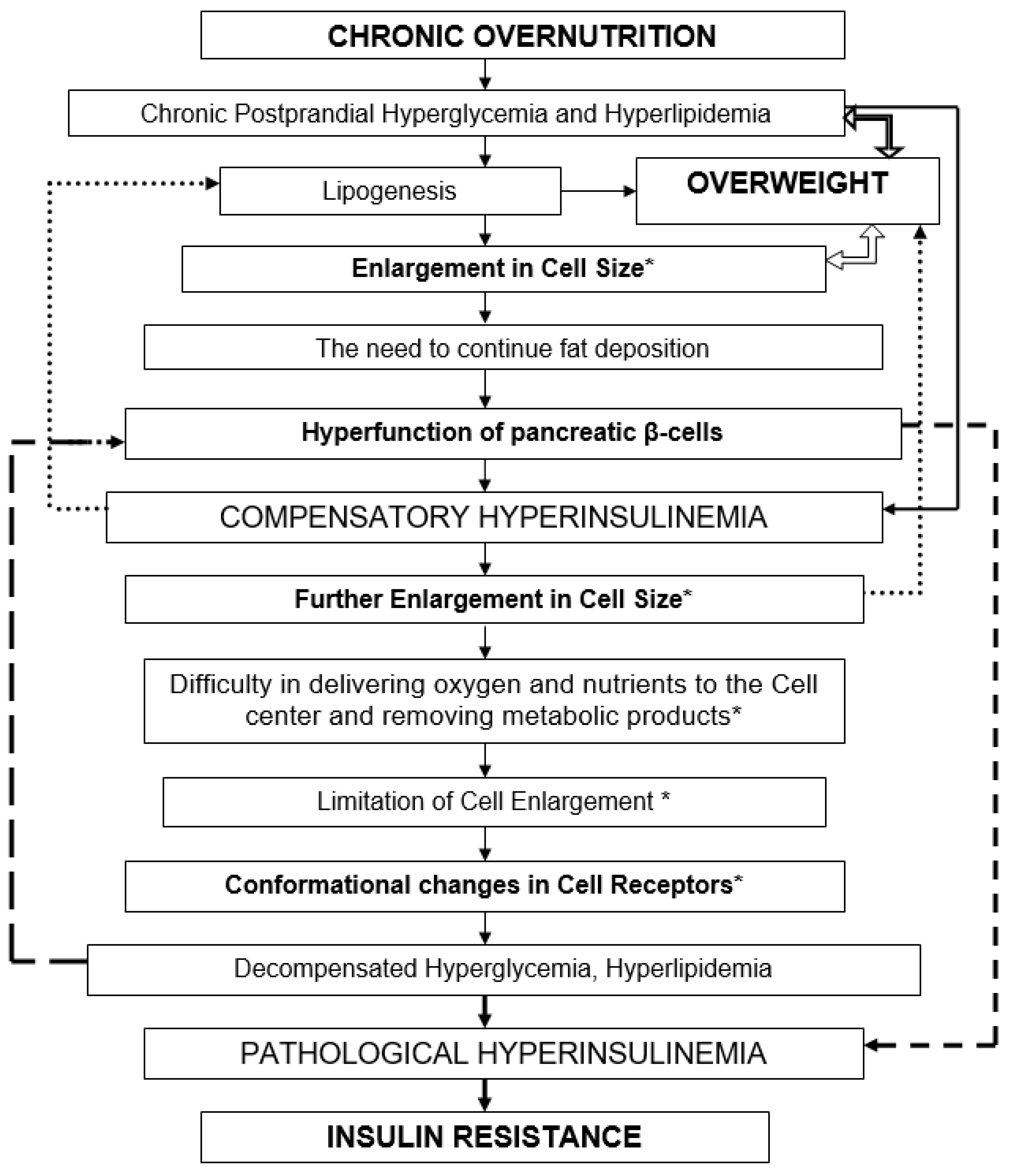

HI is a physiological response to every food consumption. Chronic overnutrition and persistent postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia lead to overweight. (

Figure 3) Forced fat accumulation in the body leads to an increase in cell size [

46]. Hyperfunction of the pancreatic β-cells leads to compensatory HI. HI occurs as compensation for the forced accumulation of fat by cells. When cells have accumulated fat to the limit, their further increase can threaten their own destruction (death, apoptosis) [

2,

53]. To limit further nutrient accumulation, HI triggers conformational changes in cell membrane receptors, specifically IR [

54]. HI gradually loses its compensatory and adaptive value.

IRis the body’s pathophysiological response to the continued flow of nutrients into the blood (hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia). IR is a rational response of the body that limits further supply of nutrients to cells. Fat reserves stored in the body themselves require metabolic attention from the body, including adequate blood circulation, thermoregulation, anabolic and catabolic metabolic processes, etc. [

54]. IR is a protective mechanism of cells against unsafe fat deposition and excessive energy expenditure [

55]. This adaptive-compensatory mechanism is limited by cell size. [

56] Under IR conditions, the HI phenomenon suppresses lipolysis, which aggravates the progression of obesity and worsens IR itself [

57]. Long-term HI under overeating and overweight depletes the secretory apparatus of pancreatic β-cells, which impairs cellular glucose tolerance. IR prevents further accumulation of fat in cells [

58]. A vicious circle arises, in which it is sometimes difficult to understand what is primary and what is secondary. Hyperglycemia, HI, IR are different links in the same pathogenetic chain of a pathological process.

In this context, the body needs to maintain the metabolism of an increased amount of metabolites, which is achieved by increasing the rate of physicochemical processes, for instance, by activating physical (increased blood pressure, body temperature) and/or chemical (increased amount of biologically active substances, hormones, oxidation-reduction reactions) processes that provide cells with increased metabolic intensity [

2,

59]. Dysfunction of overweight is a prerequisite for the development of IR. Overweight depletes and limits the reserve capacity of the body's organs and tissues, including pancreatic β-cells. IR, in the context of overweight dysfunction might be an adaptive cellular response aimed to protect cells from destruction. IR occurs when cellular spatial reserves are depleted and serves as a defense against excess fat deposition. IR is not a primary, but a secondary pathophysiological element in T2DM. We should cope with not the consequence (IR), but the cause – overweight.

5. Conclusions

HOMA-IR reduced significantly in all compared groups, which was associated with weight loss in patients with T2DM and hypertension: the HOMA-IR decreases by 65% if body weight decreases by 10%; if body mass decreases by 25%, then HOMA-IR decreases by 83%. Weight loss leads to reduce the need for antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs in the patients.

Strengths and limitations: A strength of our study is that it demonstrates for the first time that different weight loss methods may have different effects on HOMA-IR reduction. Published studies comparing the effects of different weight loss interventions (pharmacologic, bariatric surgery, VLCD) on glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure parameters in people with T2DM and hypertension are very limited in scope and number. We attempted to make a research contribution to the study of the role of insulin resistance in the development of T2DM.

This study has several limitations. First, the study included the relatively small number of patients with T2DM and hypertension. Second, the clinical trial had approximately 14% of the randomly assigned population dropped out prior to completion. There was only 90-day study that not enough to observe T2DM and hypertension outcomes. Third, the protective role of insulin resistance is a new understanding of the pathophysiology of the development of T2DM in the context of overweight.

Further high-quality multicenter clinical trials with a large sample size and longer-term follow-up are needed to confirm and extend the results of the study.

Authors' contributions

KO: design and performance, patient recruitment and treatment, data collection, bibliography review, scientific analysis, statistical advancing, scientific executor, writing draft, editing, and revision. AD: study design, patient recruitment and treatment, writing the methods and discussion, bibliography, paper review, and print. GK and NB: design and performance, bibliography review, data collection, scientific analysis, writing methods/results/discussion, editing, and paper review. AN: study design, research executor, writing the methods, editing, and revision. TS and AI: patient recruitment and treatment, preparation of e-version data collection, bibliography, and paper review, patient recruitment and treatment, preparation e-version data collection in Excel, bibliography and paper review, statistical advancing, writing the methods. GD: paper scientific review, writing the methods, and print. TSh and ZhM: writing the methods, preparation e-version data collection in Excel, laboratory collection and paper review. SR and UK: writing the methods, paper scientific review, laboratory analysis, bibliography and paper review. AA: design and performance, laboratory organization, writing methods/discussion, editing, and paper review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in the Republic of Kazakhstan from September 1, 2024, through September 30, 2025. Participants were recruited gradually as they arrived in Center for Surgery, Clinical Academic Department of Internal Medicine, Center for Endocrinology at University Medical Center (Astana).

The Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center (phone

+7 7172 69-25-86; Web:

https://umc.org.kz/en/?ethics-commission=post-2) approved the study (approval protocol #8/2024/ПЭ of 28.08.2024; monitoring and re-approval protocol #1/2025/ПЭ of 12.02.2025. Board Affiliation: University Medical Center). The committee confirms that all methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and that informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Our manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form. All authors of the manuscript affirm that they had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Those wishing to request the study data should contact Principal Investigator of a research grant: Dr. Oshakbayev Kuat (Emails: okp.kuat@gmail.com; kuat.oshakbayev@umc.org.kz, phone + 77013999394).

Conflicts of Interest disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests (financial, professional, or personal) relevant to the manuscript. We have read and understood the journal policy on the declaration of interests and have no interests to declare.

List of Abbreviations

ANADETO: analimentary detoxication

BMI: body mass index

FBG: fasting blood glucose

GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin

HDL or LDL: high- or low-density lipoprotein

HI: hyperinsulinemia

HOMA-IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment of insulin resistance index

IR: insulin resistance

MGB: minigastric bypass

SBP or DBP: systolic or diastolic blood pressure

SGLT-2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor

T1DM or T2DM: type one or two diabetes mellitus

VLCD: very-low-calorie diet.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (grants for 2024-2026 years with trial registration AP23488544, and BR24993023).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Diagnostic Center of University Medical Center, Astana Medical University and National Laboratory Astana (Nazarbayev University) for recruiting patients, collecting data for the study, and providing technical assistance.

References

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.; Craig, C.; Liu, L.-F.; Perelman, D.; Allister, C.; Spielman, D.; Cushman, S.W. Adipose Cell Size and Regional Fat Deposition as Predictors of Metabolic Response to Overfeeding in Insulin-Resistant and Insulin-Sensitive Humans. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway, F.; Loveridge, B.; Grimes, R.M.; Tucker, T.R.; Alexander, M.; Hepford, S.A.; Fontenot, J.; Nobles-James, C.; Wilson, C.; Starr, A.M.; et al. Physiologic Insulin Resensitization as a Treatment Modality for Insulin Resistance Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. From the Triumvirate to the Ominous Octet: A New Paradigm for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 2009, 58, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, H.; Baron, A. Vascular function, insulin resistance and fatty acids. Diabetologia 2002, 45, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomilehto, J.; Lindström, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Valle, T.T.; Hämäläinen, H.; Ilanne-Parikka, P.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Laakso, M.; Louheranta, A.; Rastas, M.; et al. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Changes in Lifestyle among Subjects with Impaired Glucose Tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, S.; Dekker, J.; Heine, R. Association between HbA1c and HDL-cholesterol independent of fasting triglycerides in a Caucasian population:: evidence for enhanced cholesterol ester transfer induced by in vivo glycation. Diabetologia 1998, 41, 1249–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Villagrán-Silva, F.; Loren, P.; Sandoval, C.; Lanas, F.; Salazar, L.A. Circulating microRNAs as Potential Biomarkers of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Narrative Review. Genes 2025, 16, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, G. Role of insulin resistance in human-disease. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, A.; Wolf, G. New aspects of the relationship among hypertension, obesity, and the kidneys. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2008, 10, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatti, P.; Monti, L.; Pacchioni, M.; Pontiroli, A.; Pozza, G. Forearm insulin- and non-insulin-mediated glucose uptake and muscle metabolism in man: Role of free fatty acids and blood glucose levels. Metabolism 1991, 40, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ycaza, A.E.E.; Søndergaard, E.; Morgan-Bathke, M.; Lytle, K.; Delivanis, D.A.; Ramos, P.; Leon, B.G.C.; Jensen, M.D. Adipose Tissue Inflammation Is Not Related to Adipose Insulin Resistance in Humans. Diabetes 2022, 71, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.; Siqueira, I.; Abdelhafiz, A. The Effect of Frailty on Body Composition and Its Impact on the Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors and GLP-1RA in Older Persons with Diabetes. Metabolites 2025, 15, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armato, J.; A DeFronzo, R.; Abdul-Ghani, M.; Ruby, R. Pre-Prediabetes: Insulin Resistance Is Associated With Cardiometabolic Risk in Nonobese Patients (STOP DIABETES). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, e1481–e1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołacki, J.; Matuszek, M.; Matyjaszek-Matuszek, B. Link between Insulin Resistance and Obesity—From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lu, Y.; Gokulnath, P.; Vulugundam, G.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Xiao, J. Benefits of physical activity on cardiometabolic diseases in obese children and adolescents. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2022, 10, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhr, S.; Welsh, J.B.; Bauza, C.E.; Walker, T.C. Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Residual Insulin Secretory Capacity Realize Glycemic Benefits from Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2021, 15, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyler, J.S. Importance of residual insulin secretion in type 1 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, GM. ROLE OF INSULIN RESISTANCE IN HUMAN-DISEASE (SYNDROME-X) - AN EXPANDED DEFINITION. Annual Review of Medicine 1993, 44, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, H.; He, Q.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z. Exploring insulin resistance and pancreatic function in individuals with overweight and obesity: Insights from OGTTs and IRTs. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2025, 219, 111972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, T.; Avgerinos, I.; Liakos, A.; Del Prato, S.; Matthews, D.R.; Tsapas, A.; Bekiari, E. Management of type 2 diabetes with the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Harada, S.; Toki, R.; Hirata, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Miyagawa, N.; Iida, M.; Edagawa, S.; Miyake, A.; Kuwabara, K.; et al. Causal relationship between body mass index and insulin resistance: Linear and nonlinear Mendelian randomization study in a Japanese population. J. Diabetes Investig. 2025, 16, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedick, N.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Wingard, D.L.; Addy, C.L.; Barrett-Connor, E. Insulin Resistance Precedes Weight Loss in Adults without Diabetes: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Am. J. Epidemiology 2001, 153, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, J.; Fang, F. Effect of bariatric surgery on glycemic and metabolic outcomes in people with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-evidence of 39 studies. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1603670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, A.; Mackay, A.; Carter, B.; Fyfe, C.L.; Johnstone, A.M.; Myint, P.K. Investigating the Effectiveness of Very Low-Calorie Diets and Low-Fat Vegan Diets on Weight and Glycemic Markers in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Zeng, H.; Huang, M.; Fu, W.; Chen, Z. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: a meta-analysis. Endocrine 2022, 75, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Aroda, V.R.; Collins, B.S.; Gabbay, R.A.; Green, J.; Maruthur, N.M.; et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2753–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, T.W. Scientific-Based Research and Randomized Controlled Trials, the “Gold” Standard? Alternative Paradigms and Mixed Methodologies. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J.; Mackenzie, F.J. The Randomized Controlled Trial: gold standard, or merely standard? Perspect. Biol. Med. 2005, 48, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöting, N.; Blüher, M. Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2014, 15, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Mao, Y. Association Between Percent Body Fat Reduction and Changes of the Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance in Overweight/Obese People with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 4735–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, C.; Spalding, K. White adipocyte dysfunction and obesity-associated pathologies in humans. NATURE REVIEWS MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY 2024, 25, 270–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Shikora, S.A.; Aarts, E.; Aminian, A.; Angrisani, L.; Cohen, R.V.; et al. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2022, 18, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshakbayev, K.; Dukenbayeva, B.; Togizbayeva, G.; Durmanova, A.; Gazaliyeva, M.; Sabir, A.; Issa, A.; Idrisov, A. Weight loss technology for people with treated type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, D.; Karl, S.; Weiß, J.; Zimmermann, P.; Haupt, S.; Zimmer, R.T.; Schierbauer, J.; Wachsmuth, N.B.; Erlmann, M.P.; Niedrist, T.; et al. Effects of Different Types of Intermittent Fasting Interventions on Metabolic Health in Healthy Individuals (EDIF): A Randomised Trial with a Controlled-Run in Phase. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stottlemyer, B.A.; McDermott, M.C.; Minogue, M.R.; Gray, M.P.; Boyce, R.D.; Kane-Gill, S.L. Assessing adverse drug reaction reports for antidiabetic medications approved by the food and drug administration between 2012 and 2017: a pharmacovigilance study. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermansaravi, M.; Shahsavan, M.; Hage, K.; Taskin, H.E.; ShahabiShahmiri, S.; Poghosyan, T.; Jazi, A.H.D.; Baratte, C.; Valizadeh, R.; Chevallier, J.-M.; et al. Iron deficiency anemia after one anastomosis gastric bypass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.; Berg, A. Weight Loss Strategies and the Risk of Skeletal Muscle Mass Loss. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Sellami, M.; Salem, I.; Conic, R.Z.; Kimak, M.; Pigatto, P.D.M.; Damiani, G. Fasting and Its Impact on Skin Anatomy, Physiology, and Physiopathology: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2019, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.J.; Varley, I.; Papageorgiou, M. Intermittent fasting and bone health: a bone of contention? Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, T.; Schön, J.; Glisic, C.; Pfoser, K.; Kerschbaumer, C.; Mayrl, M.S.; Schrögendorfer, K.F.; Bergmeister, K.D. Bariatric Surgery Before Abdominoplasty Is Associated with Increased Perioperative Anemia, Hemoglobin Loss and Drainage Fluid Volume: Analysis of 505 Body Contouring Procedures. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Tasset, I.; Arias, E.; Pampliega, O.; Wong, E.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Cuervo, A.M. Autophagy and the hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto-Imoto, H.; Isaka, Y.; Hamasaki, M. Autophagy and kidney aging. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 179, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Cao, P.; Lin, Y.; Yu, P.; Song, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y. Intermittent Caloric Restriction Promotes Erythroid Development and Ameliorates Phenylhydrazine-Induced Anemia in Mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 892435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Javaheri, A.; Godar, R.J.; Murphy, J.; Ma, X.; Rohatgi, N.; Mahadevan, J.; Hyrc, K.; Saftig, P.; Marshall, C.; et al. Intermittent fasting preserves beta-cell mass in obesity-induced diabetes via the autophagy-lysosome pathway. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1952–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.; Lamendola, C.; Coglan, N.; Liu, T.C.; Lerner, K.; Sherman, A.; Cushman, S.W. Subcutaneous adipose cell size and distribution: Relationship to insulin resistance and body fat. Obes. 2014, 22, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Do, M.-S. BAFF knockout improves systemic inflammation via regulating adipose tissue distribution in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Wan, X.; Khan, A.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Peng, L. Expression Analysis of circRNAs in Human Adipogenesis. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, G. The relationship between islet β-cell function and metabolomics in overweight patients with Type 2 diabetes. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.; Balaji, M.; Varghese, J.; Marconi, S.; Sudhakar, Y.; Jebasingh, F.; Venkatesan, P. Effect of short-term (4 weeks) low-calorie diet induced weight loss on beta-cell function in overweight normoglycemic subjects: A quasi-experimental pre-post interventional study. Metab. Open 2025, 27, 100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, S.; Koh, H.-C.E.; Patterson, B.W.; Yoshino, M.; LaForest, R.; Gropler, R.J.; Klein, S.; Mittendorfer, B. Obesity Is Associated With Increased Basal and Postprandial β-Cell Insulin Secretion Even in the Absence of Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J.; Maity, S.K.; Sen, A.; Nargis, T.; Ray, D.; Chakrabarti, P. Impaired compensatory hyperinsulinemia among nonobese type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional study. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, A; Hannemann, N. Mechanism of Regulation of Adipocyte Numbers in Adult Organisms Through Differentiation and Apoptosis Homeostasis. JOVE-JOURNAL OF VISUALIZED EXPERIMENTS 2016, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, M.; Fujisaka, S.; Cai, W.; Winnay, J.N.; Konishi, M.; O'Neill, B.T.; Li, M.; García-Martín, R.; Takahashi, H.; Hu, J.; et al. Adipocyte Dynamics and Reversible Metabolic Syndrome in Mice with an Inducible Adipocyte-Specific Deletion of the Insulin Receptor. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Hernández, A.; Perdomo, L.; Heras, N.d.L.; Beneit, N.; Escribano, Ó.; Otero, Y.F.; Guillén, C.; Díaz-Castroverde, S.; Gozalbo-López, B.; Cachofeiro, V.; et al. Antagonistic effect of TNF-alpha and insulin on uncoupling protein 2 (UCP-2) expression and vascular damage. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Mechanism of insulin resistance in obesity: a role of ATP. Front. Med. 2021, 15, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szosland, K.; Lewinski, A. Insulin resistance - "the good or the bad and ugly. 2018, 39, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Cao, M.-M.; Liu, H.; Xie, G.-Y.; Li, Y.-B. Autophagy regulates insulin resistance following endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 71, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Moullec, G.; Santosa, S. Factors associated with adipocyte size reduction after weight loss interventions for overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-regression. Metabolism 2017, 67, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).