Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

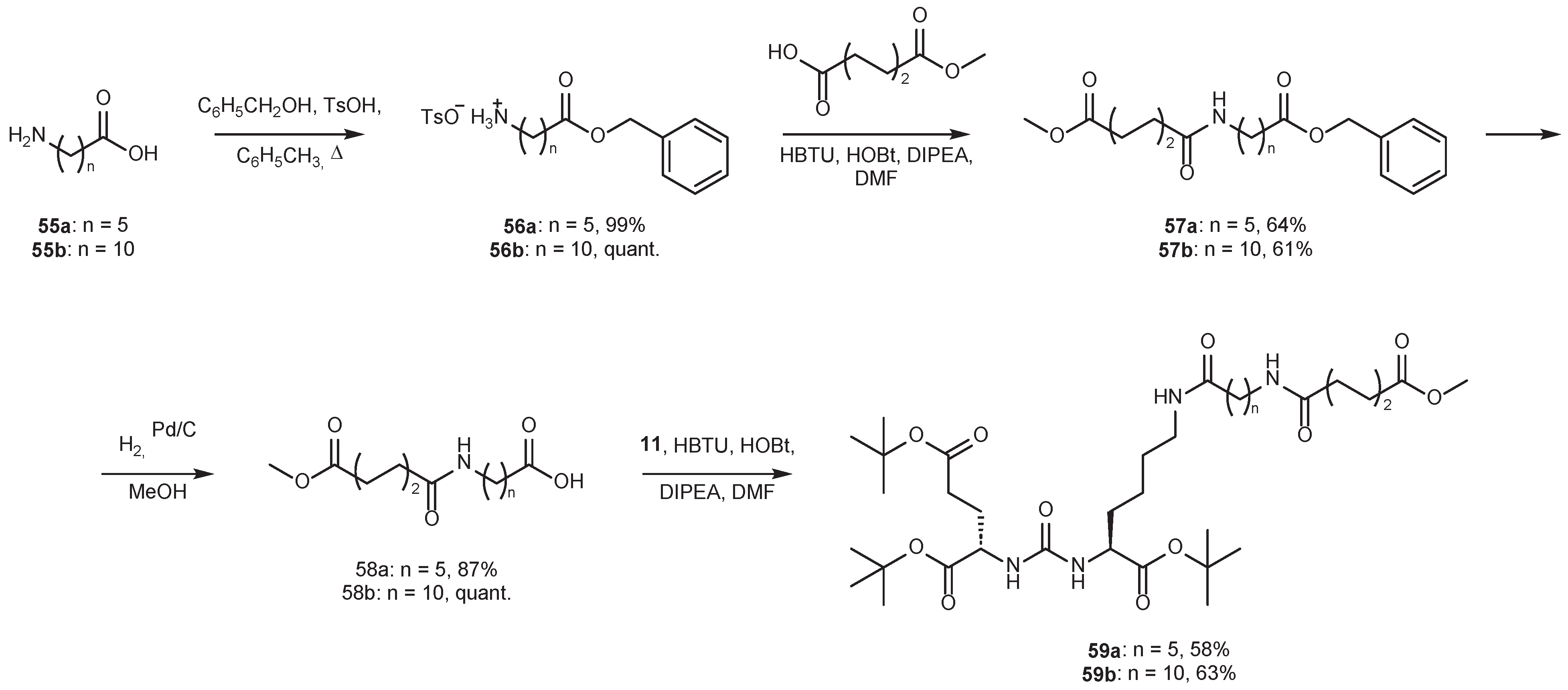

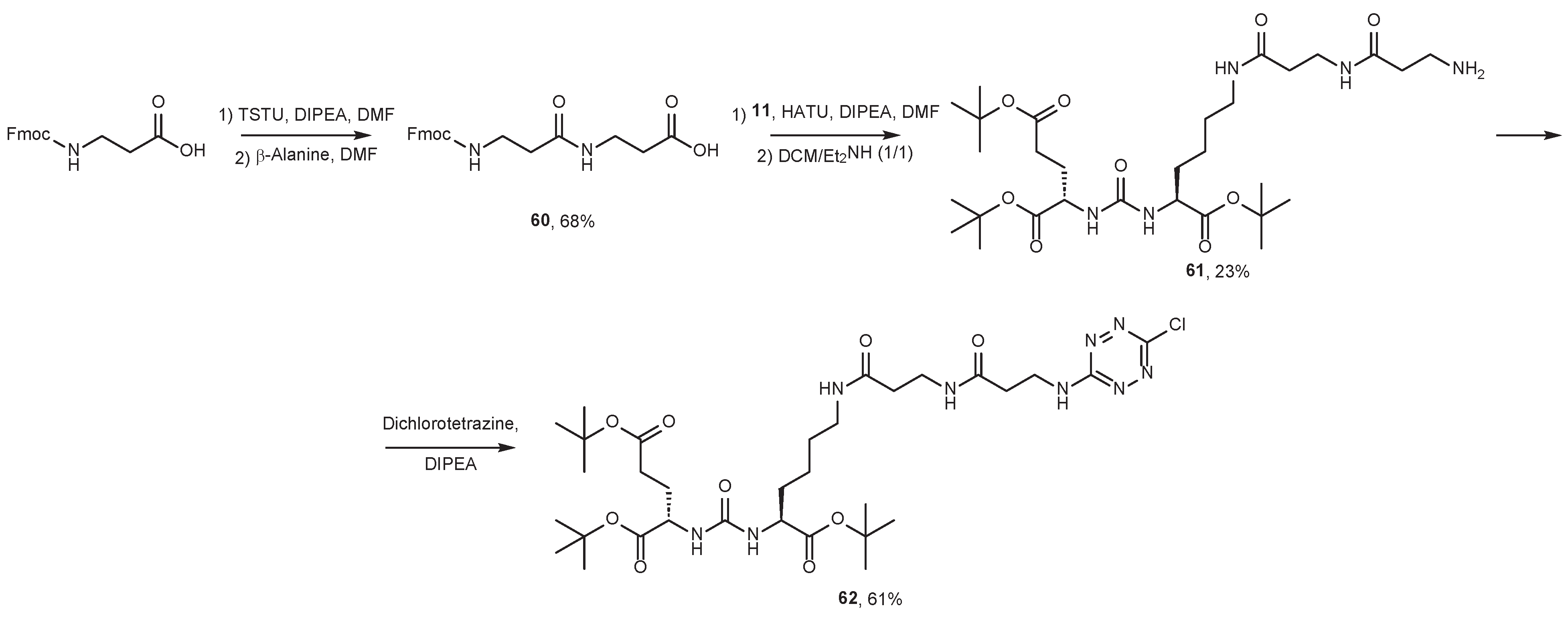

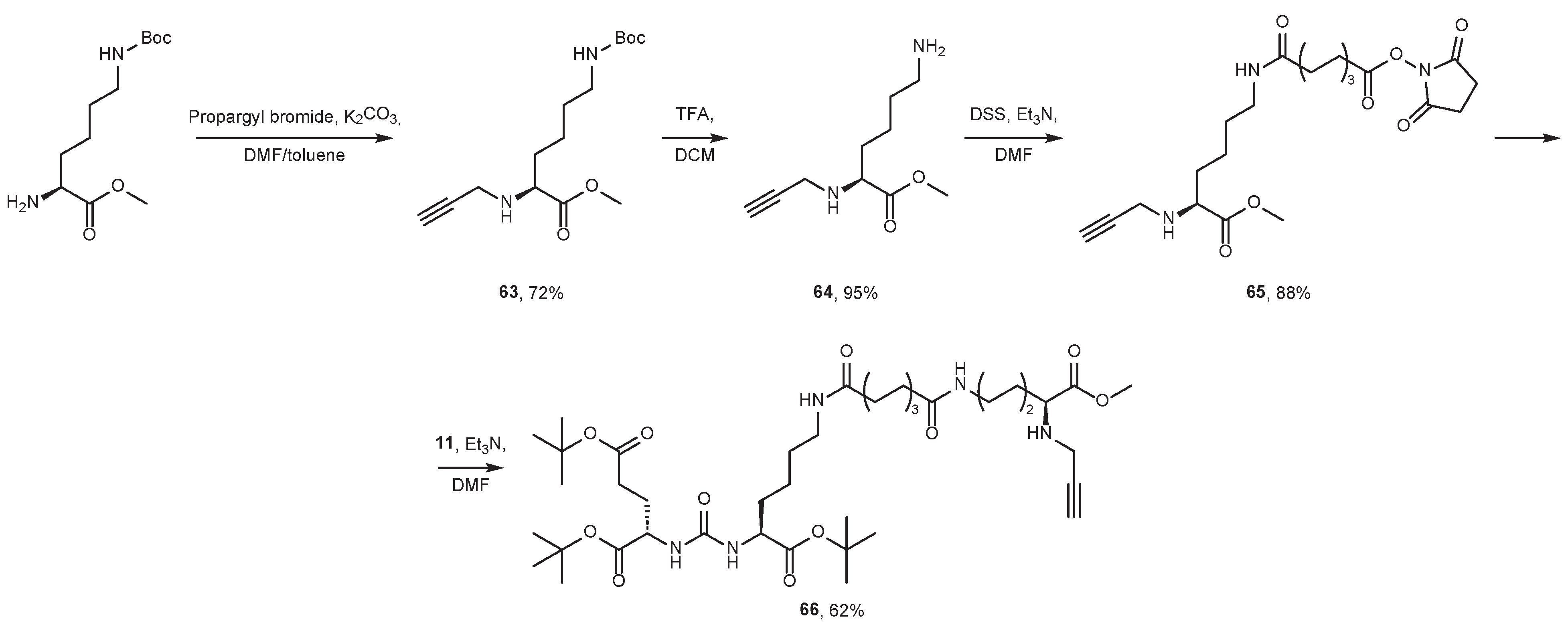

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

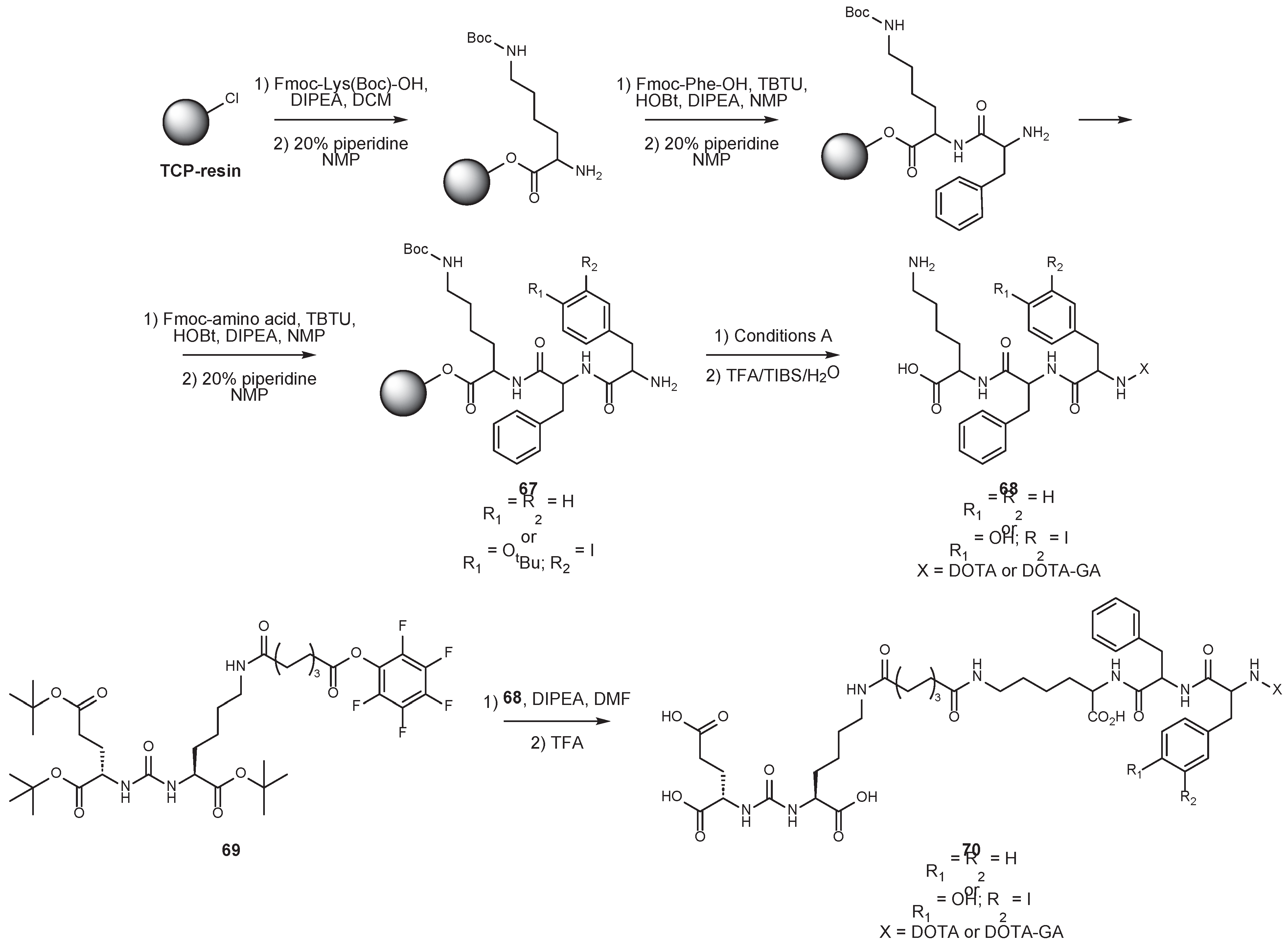

Keywords:

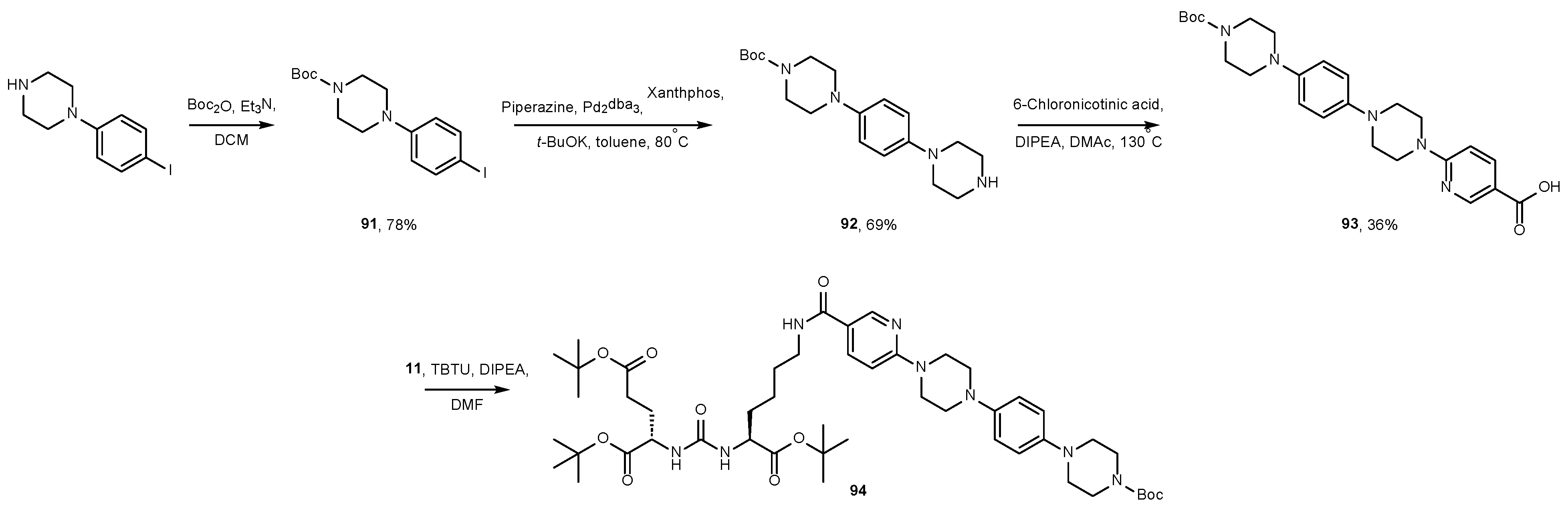

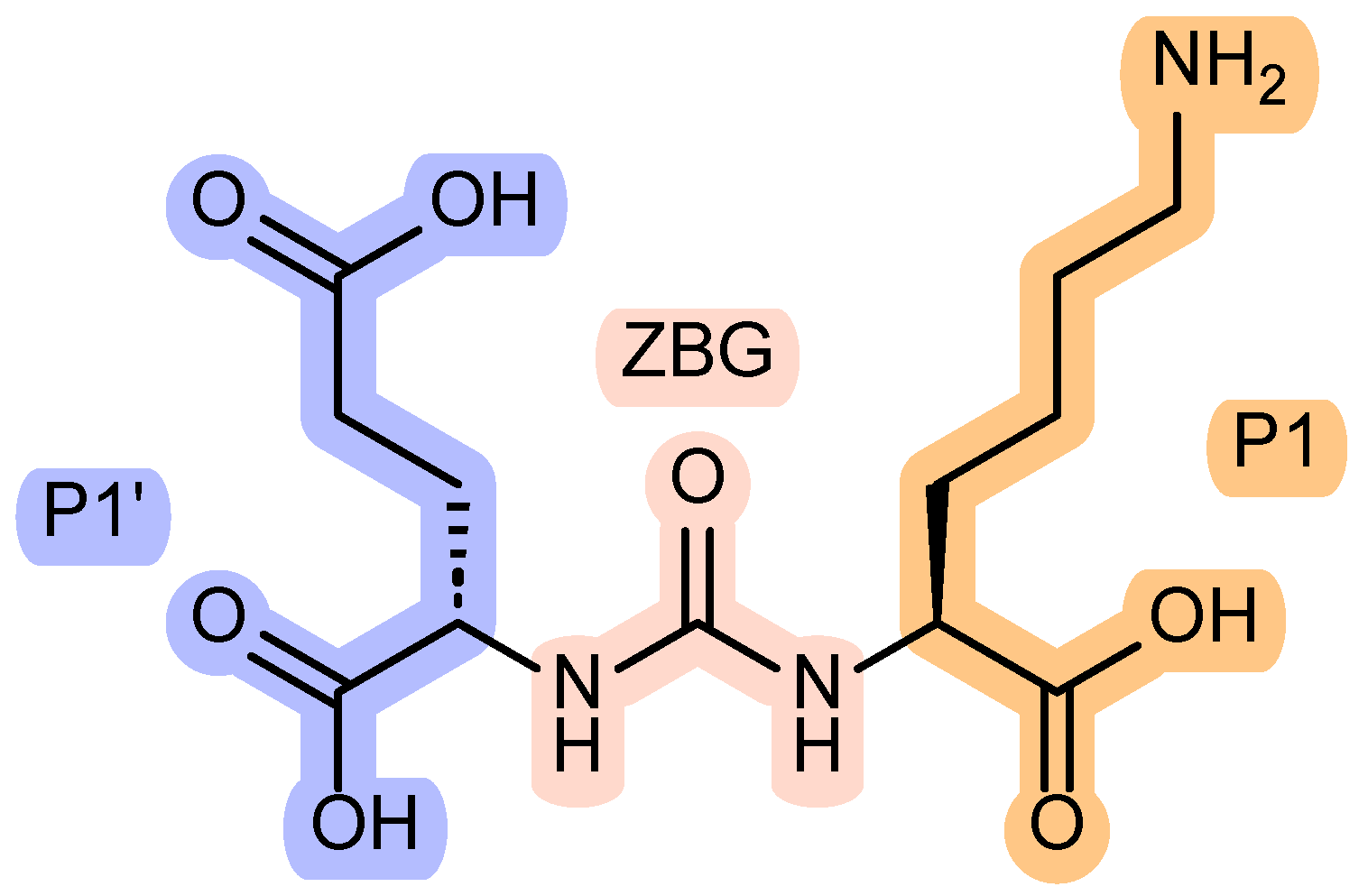

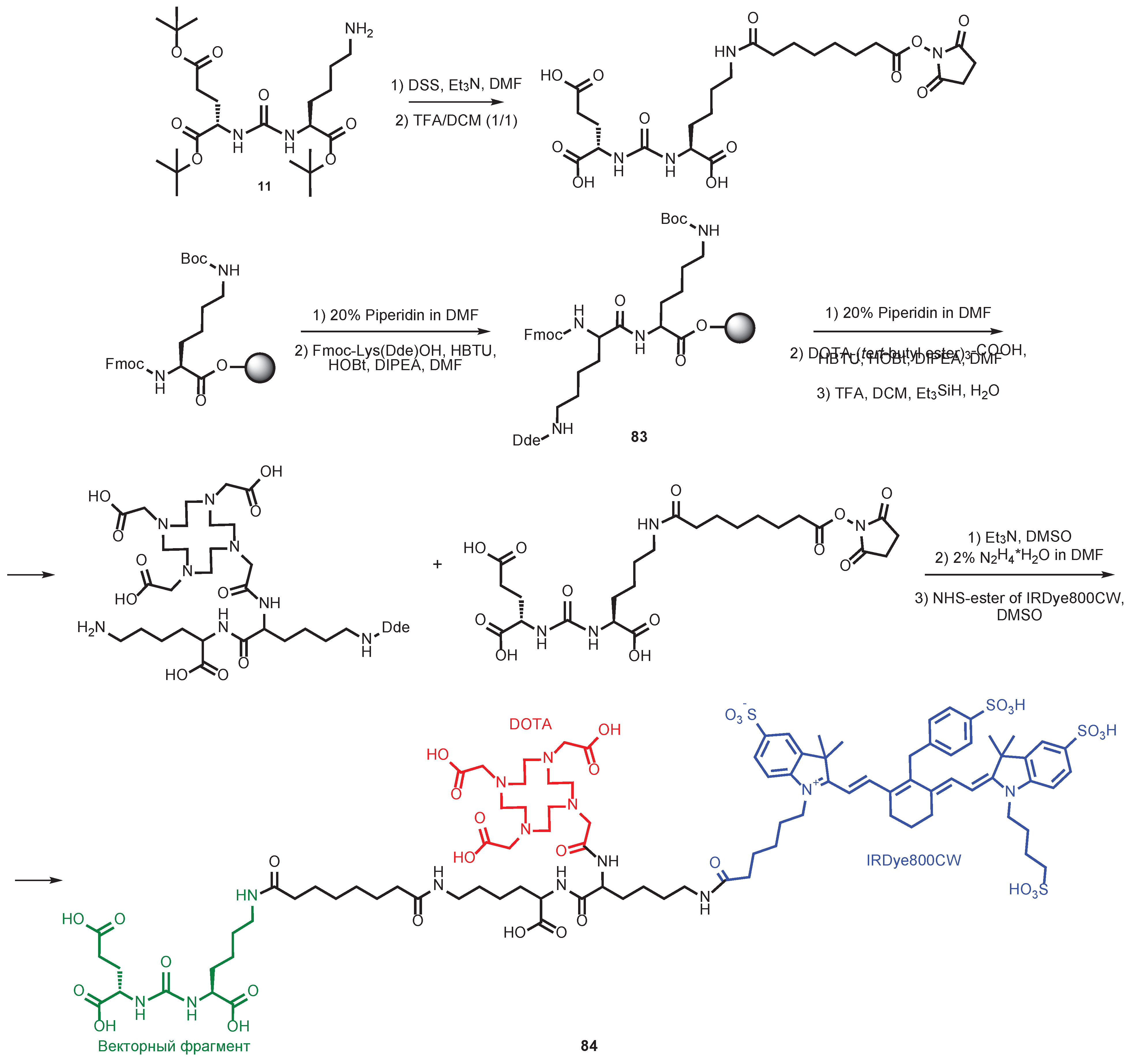

1. Introduction

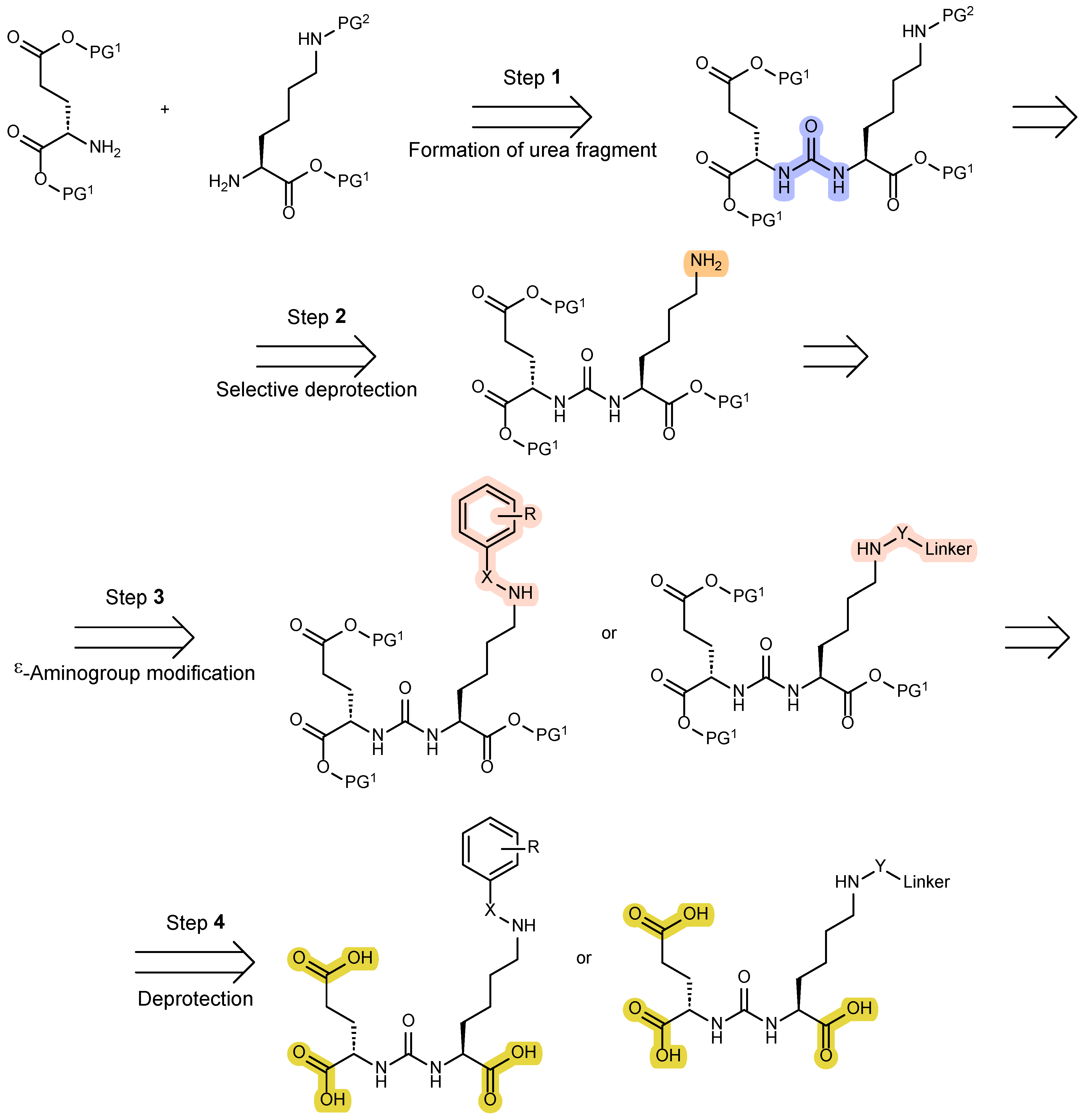

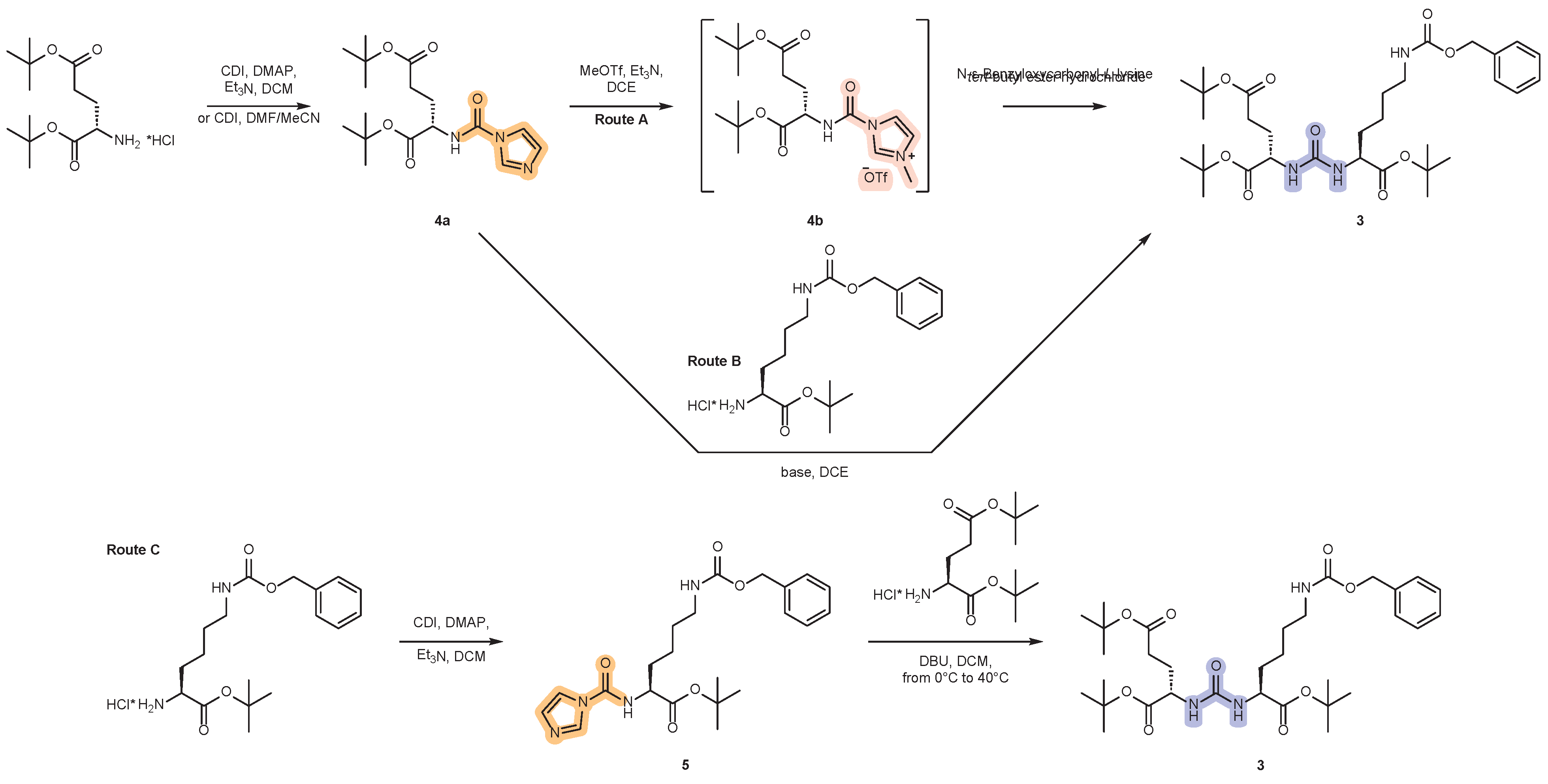

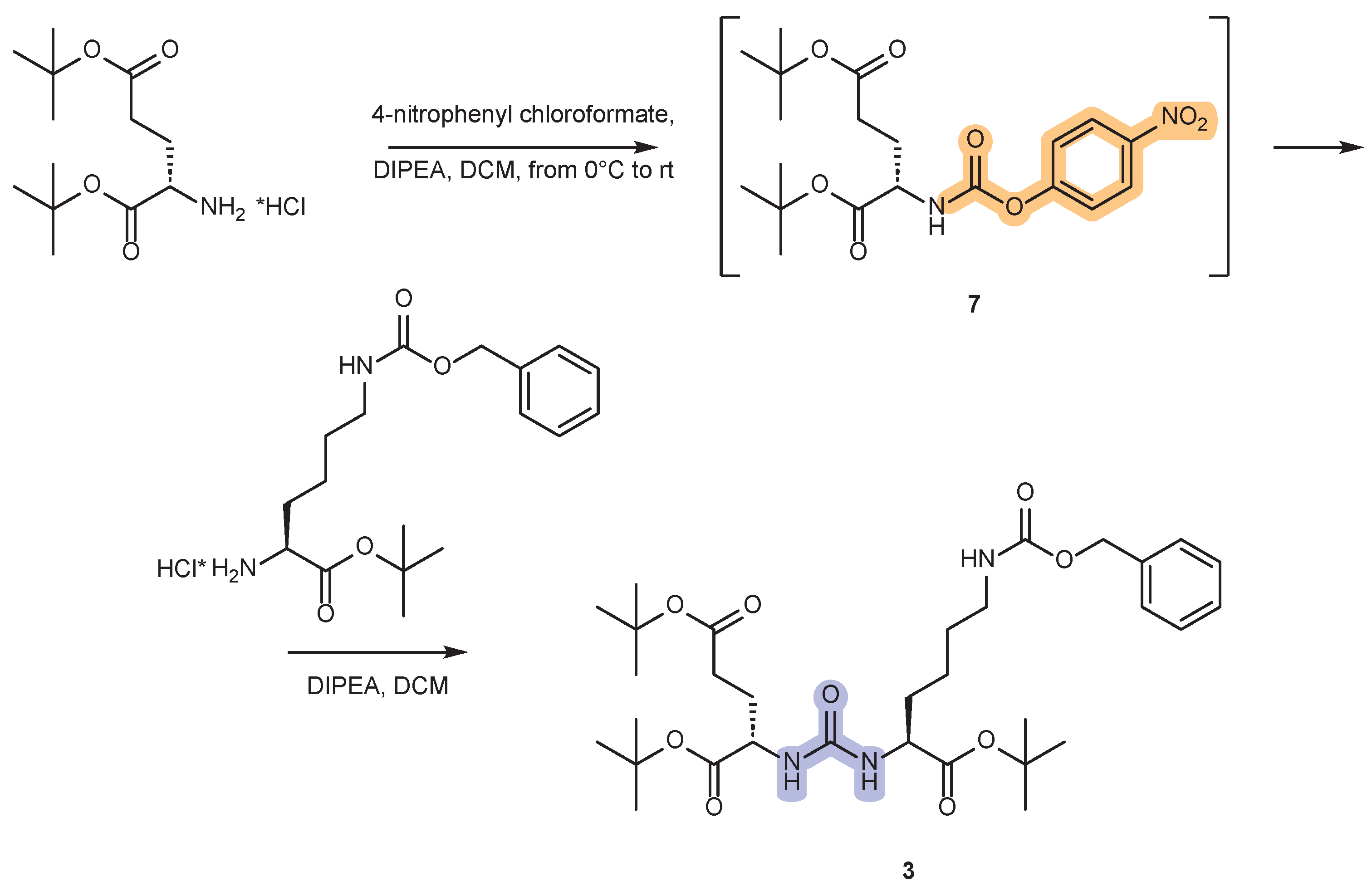

2. Methods of Creating a Urea Fragment

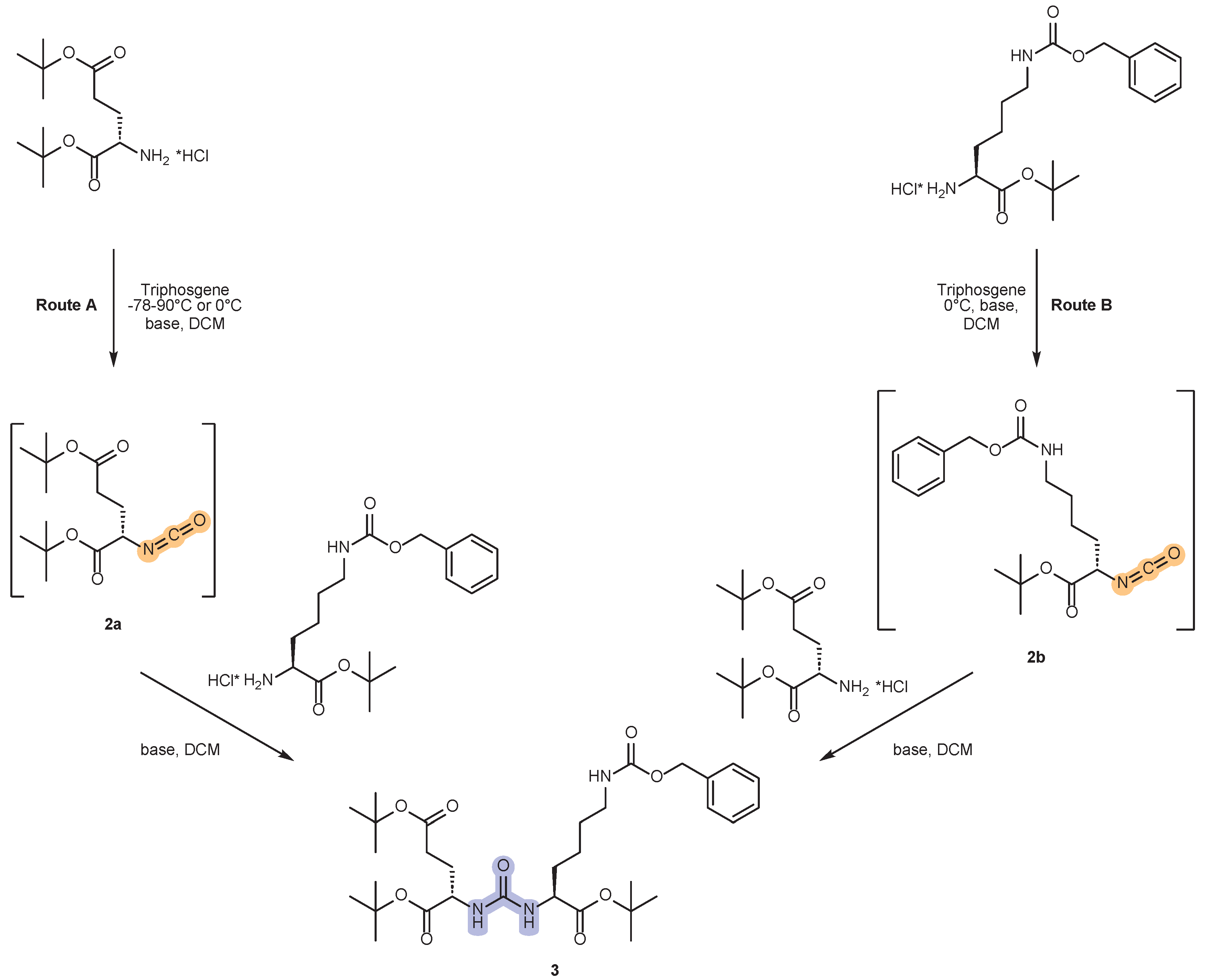

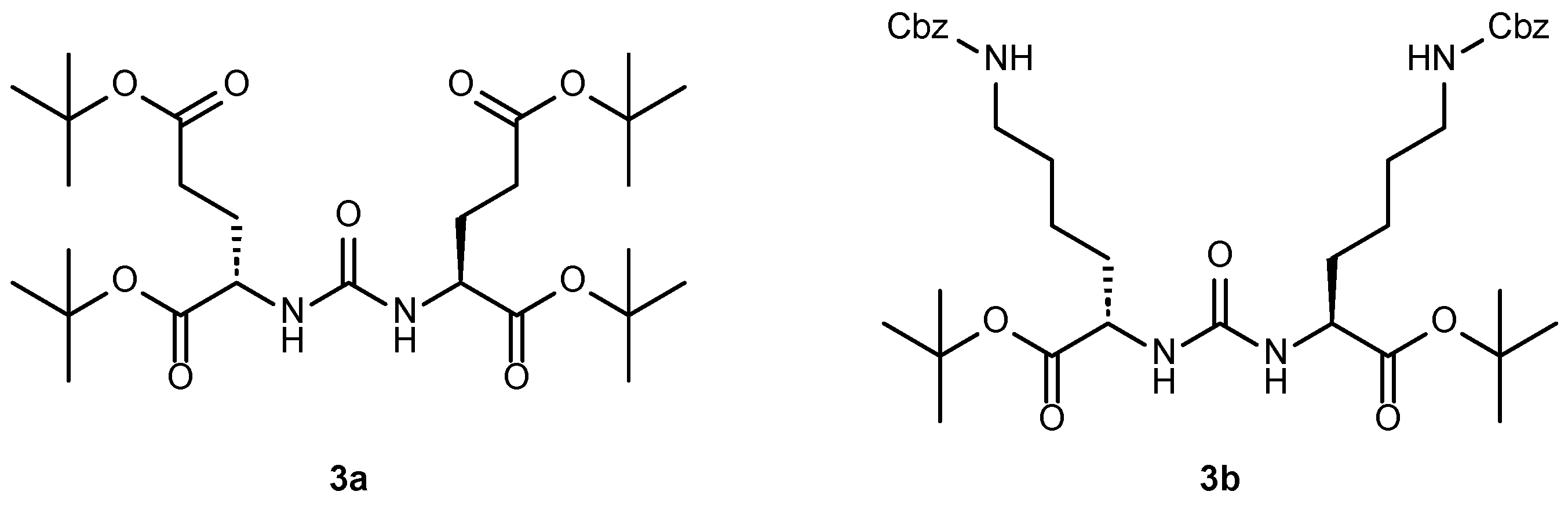

2.1. Approaches to the Synthesis of DCL Urea Protected by Tert-Butyl- and Cbz-Groups

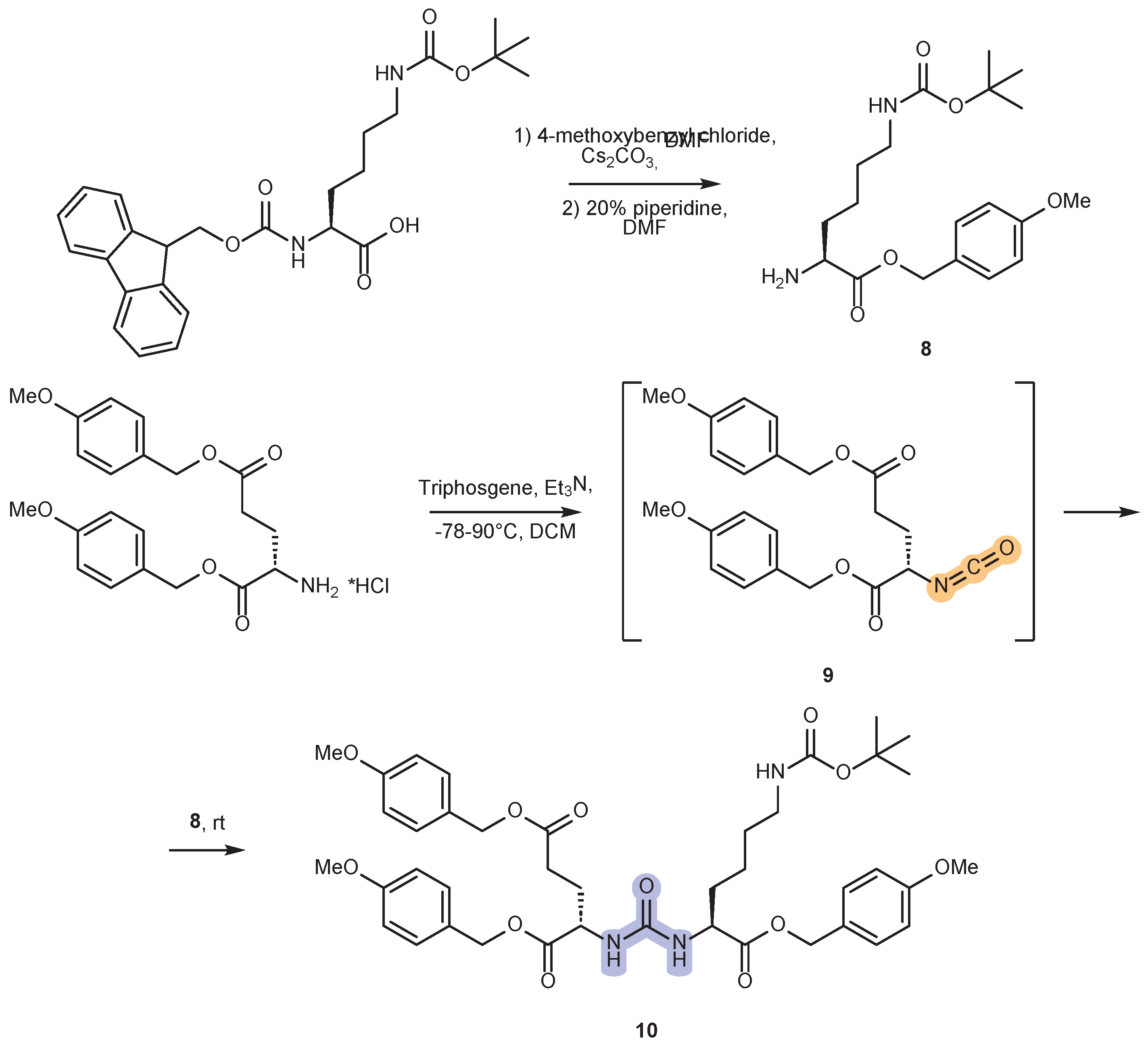

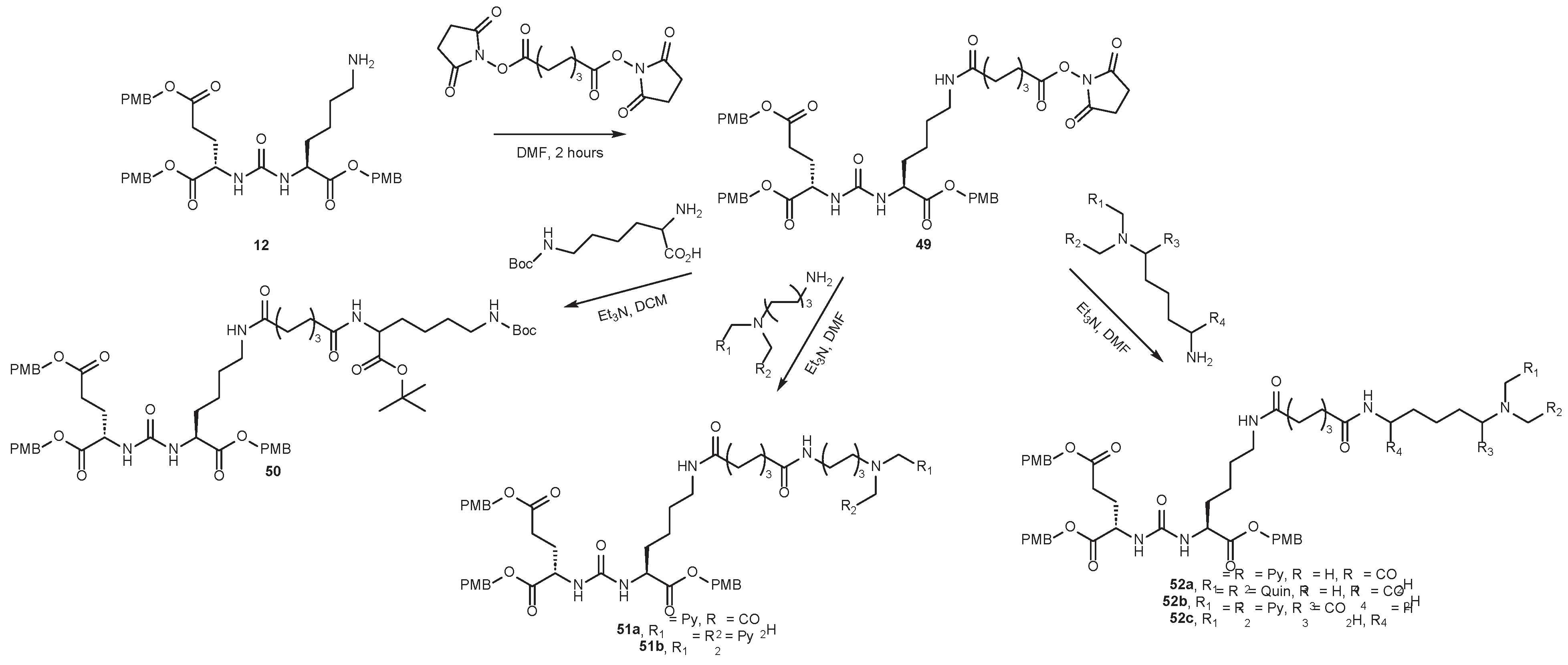

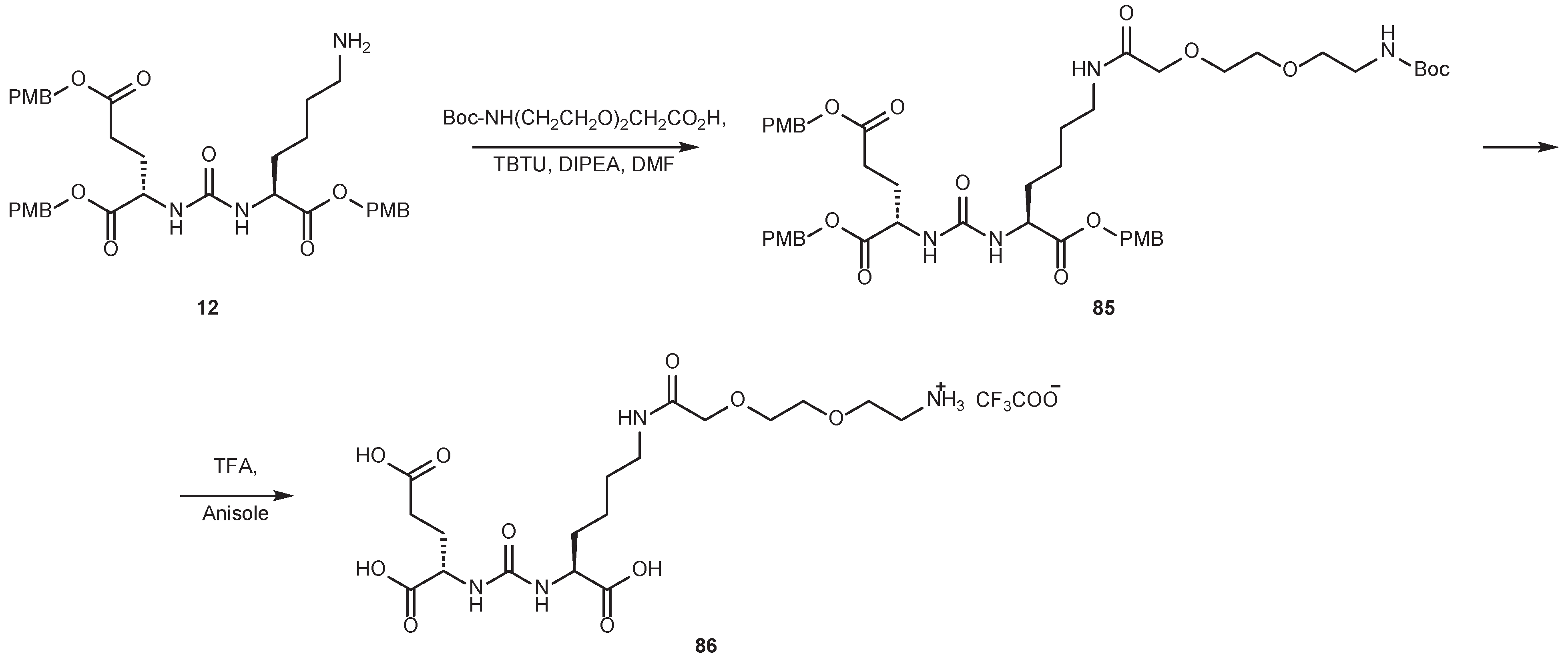

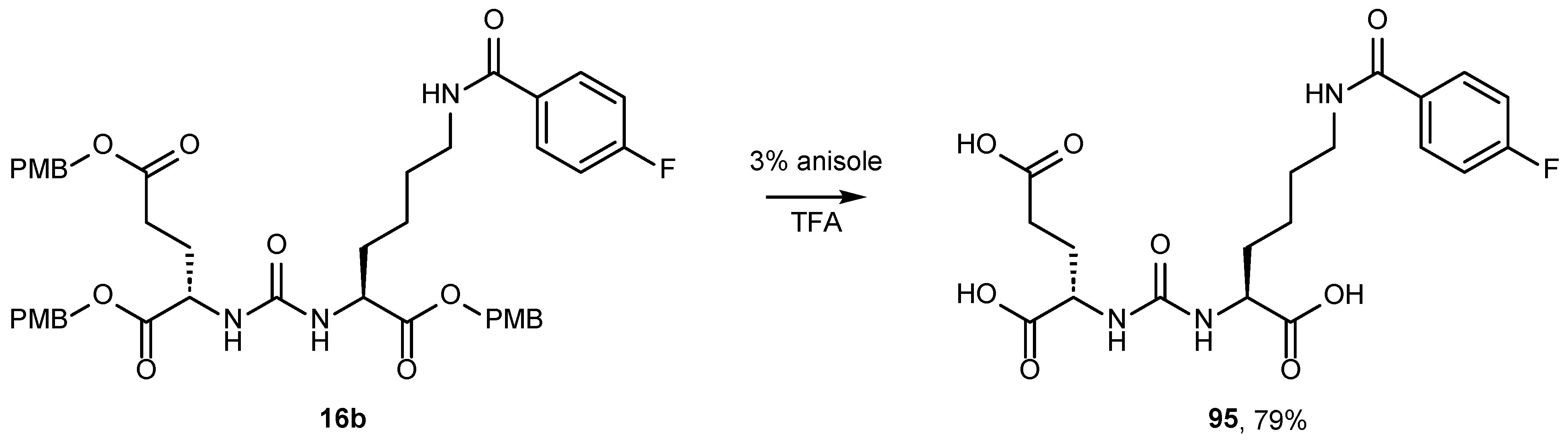

2.2. Synthesis of the PMB-Protected form of Urea DCL

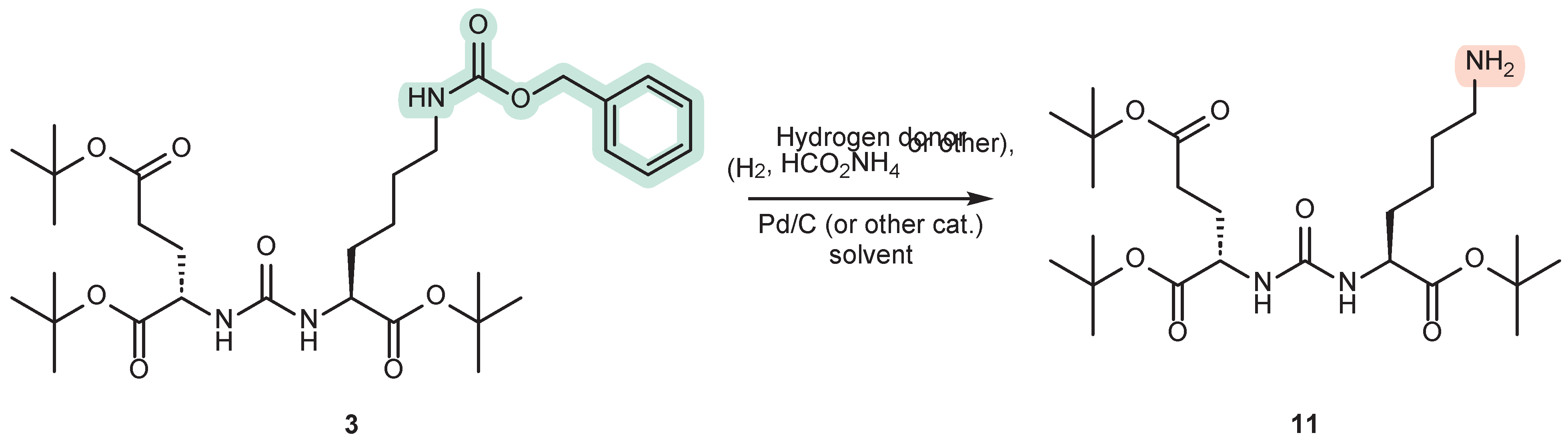

3. Existing Approaches to Removing the Protective Group at the E-Amino Group of Lysine

3.1. Removing the Cbz Protectiv Group

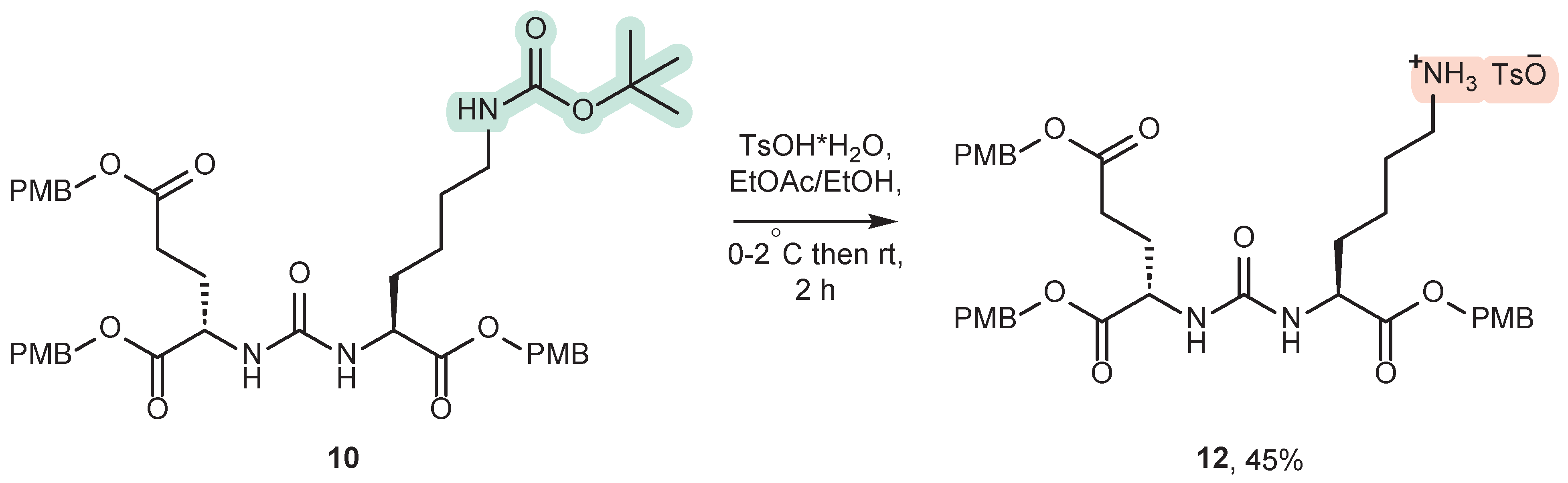

3.2. Removal of the Boc-Protective Group at the ε-Amino Group

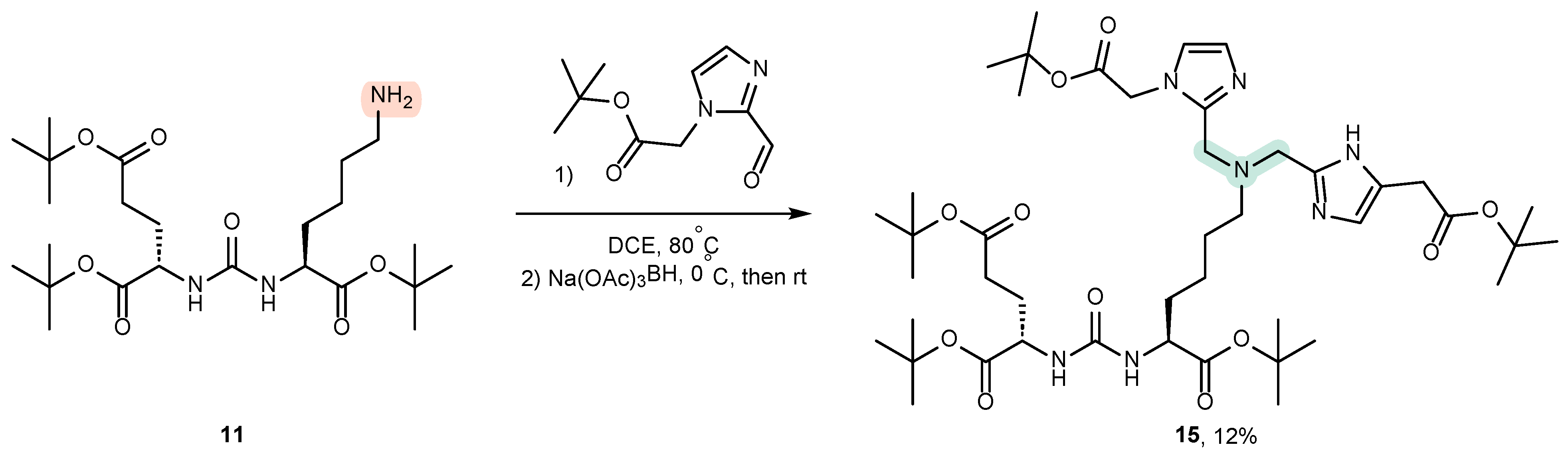

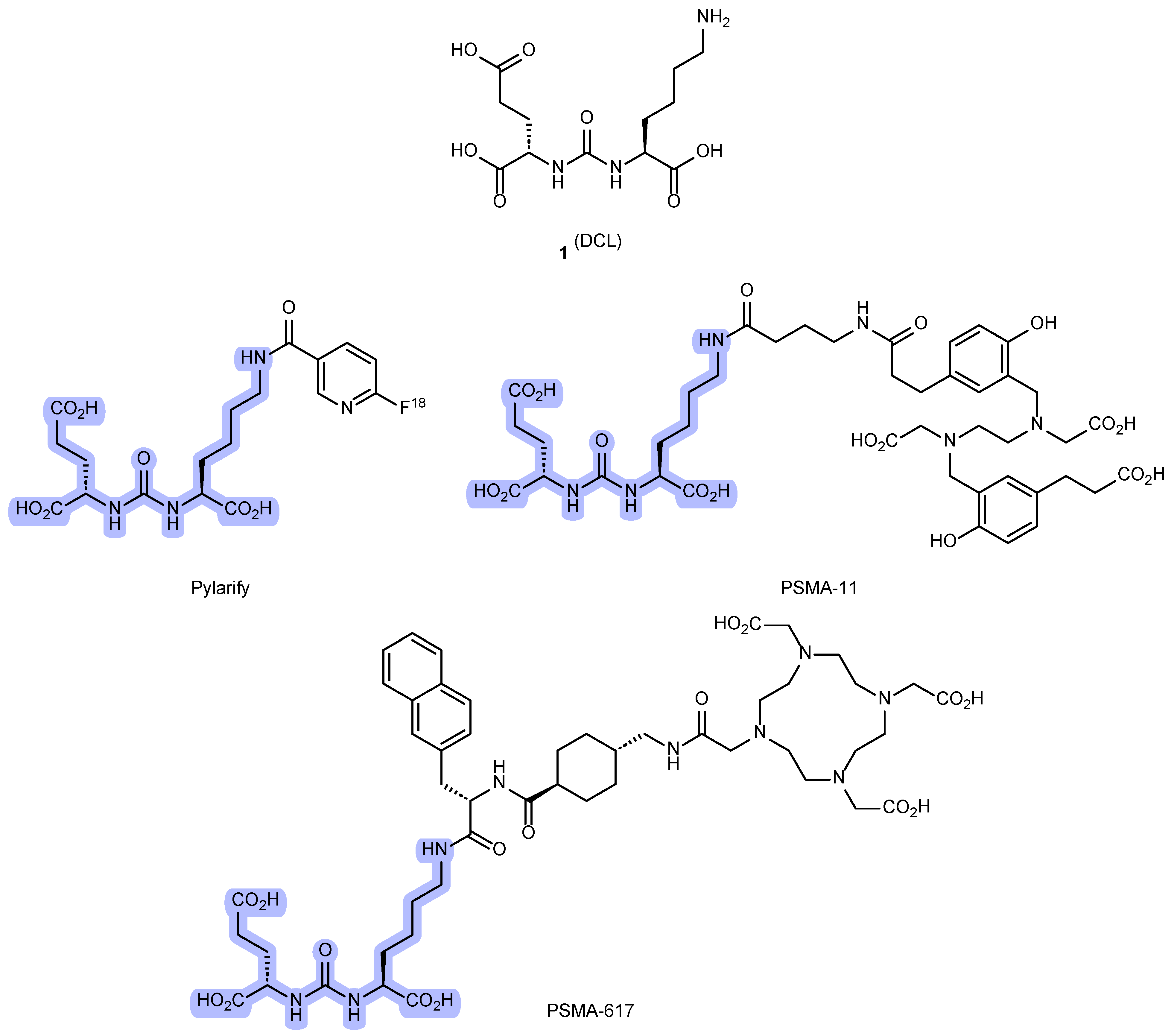

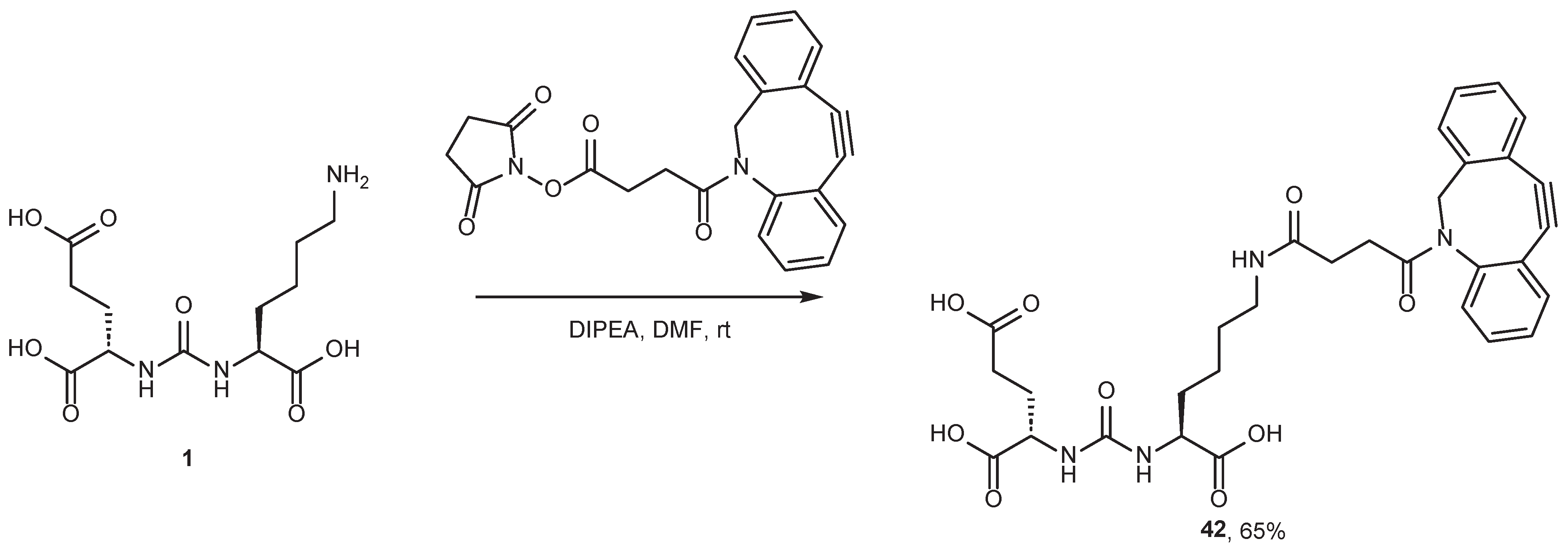

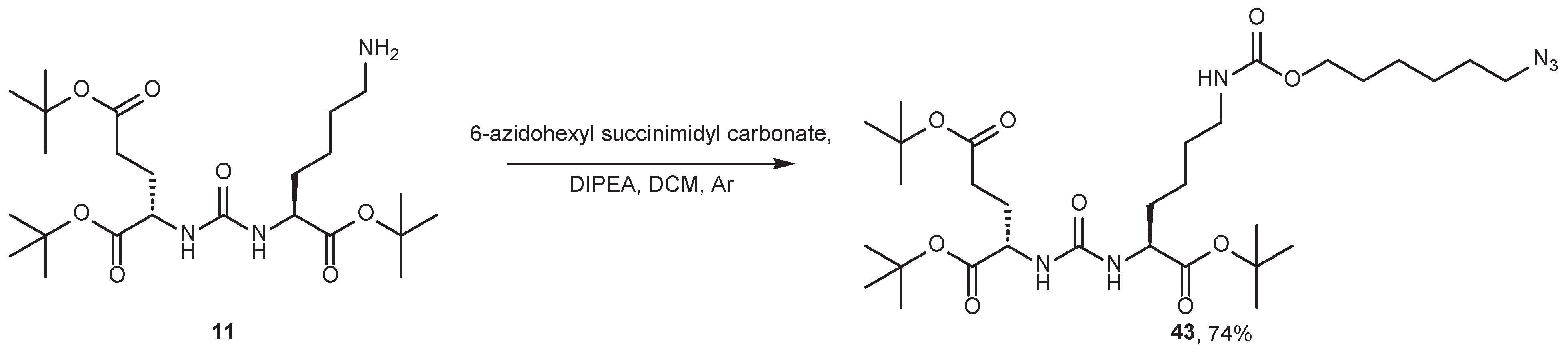

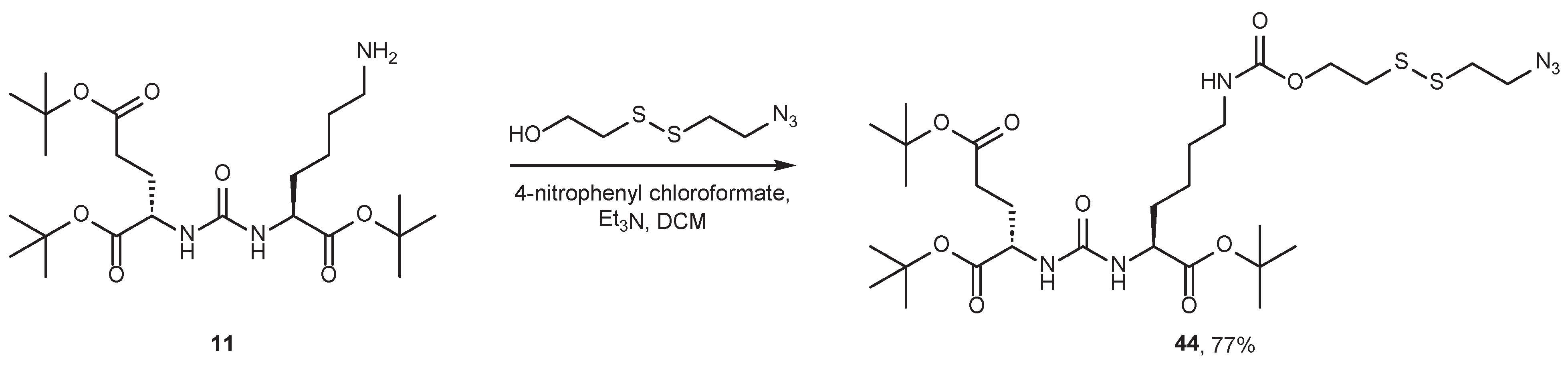

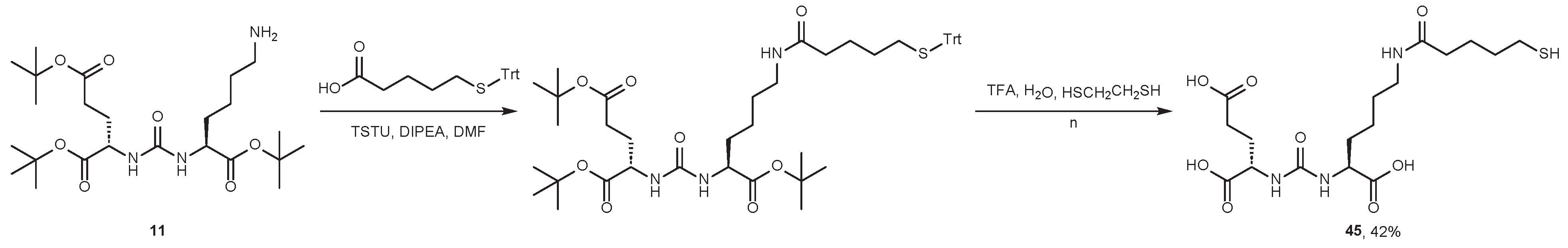

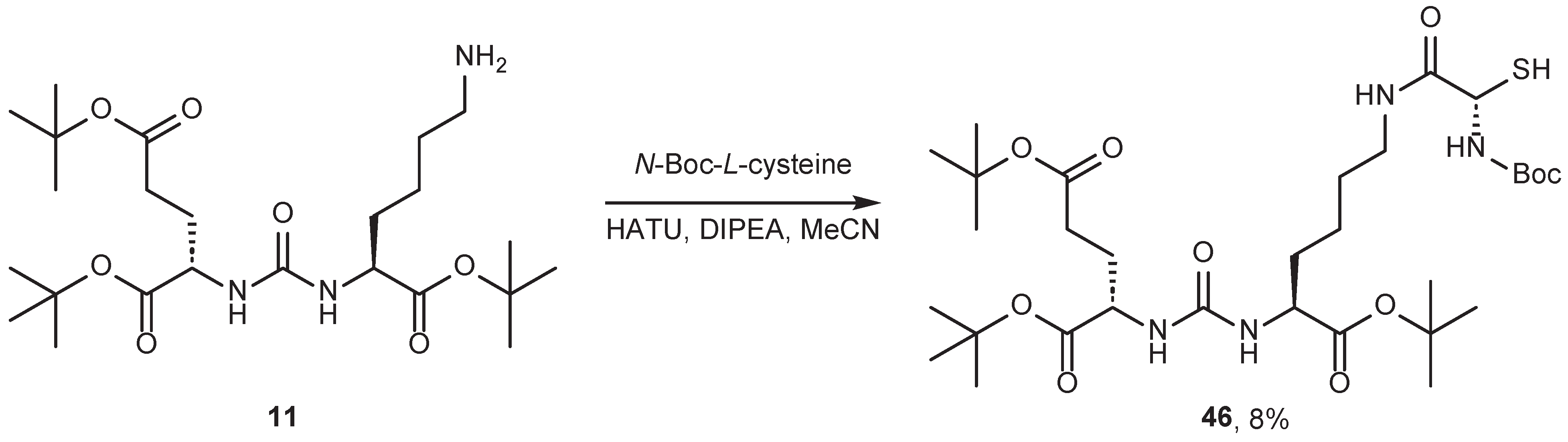

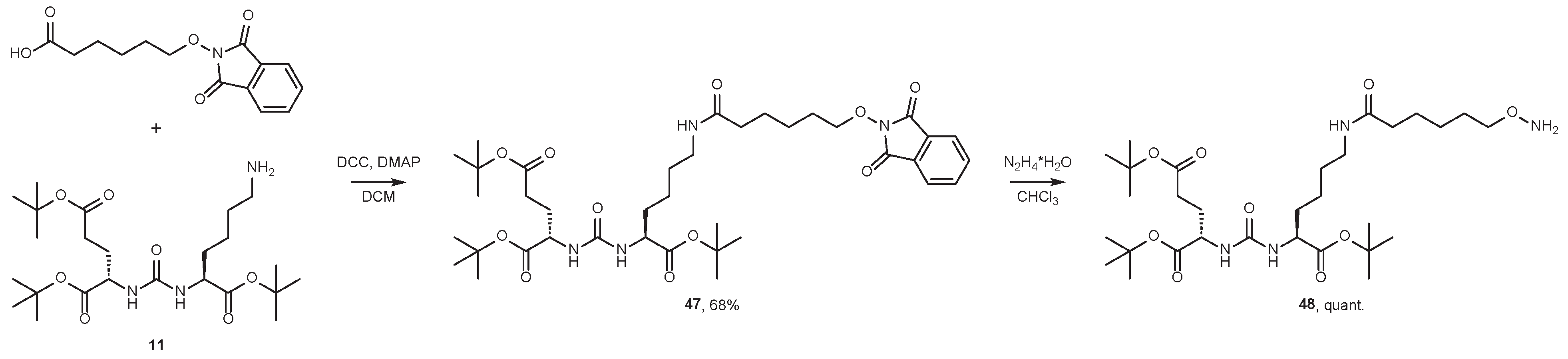

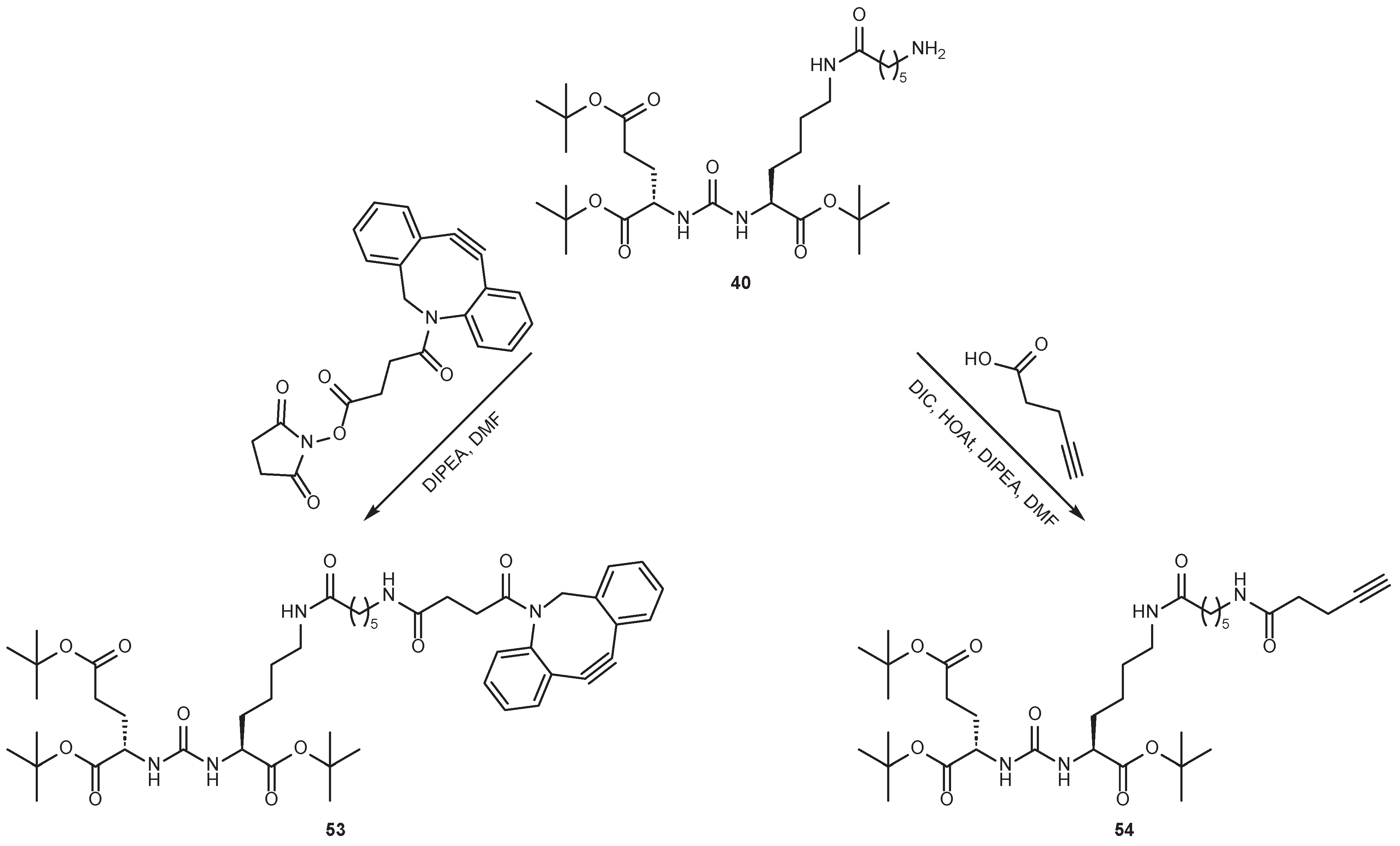

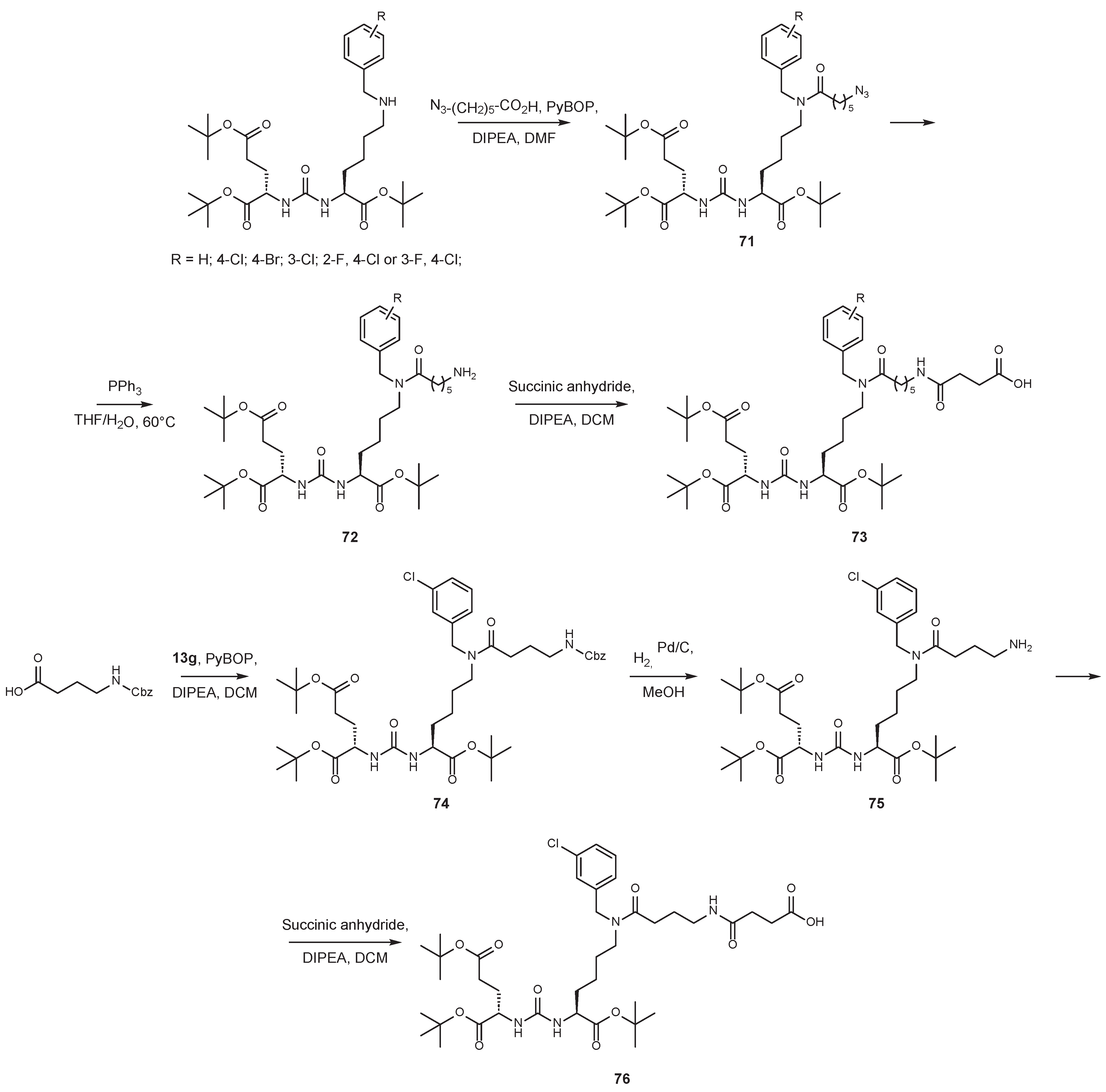

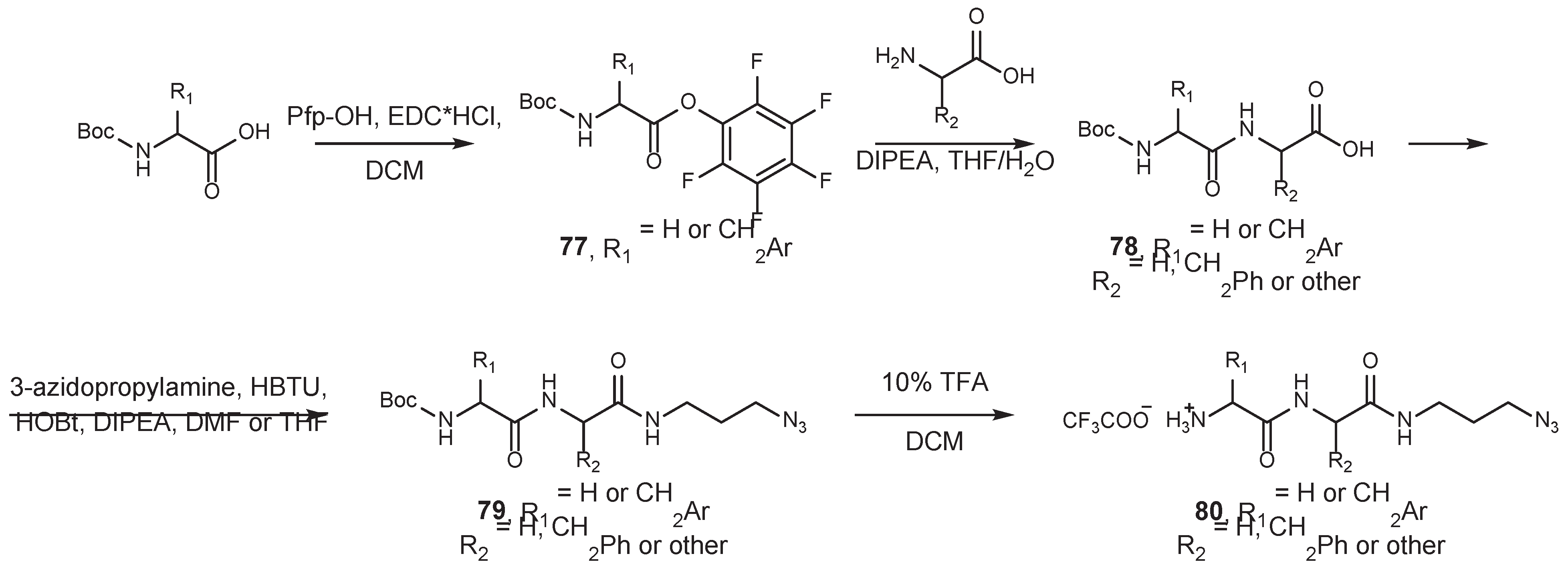

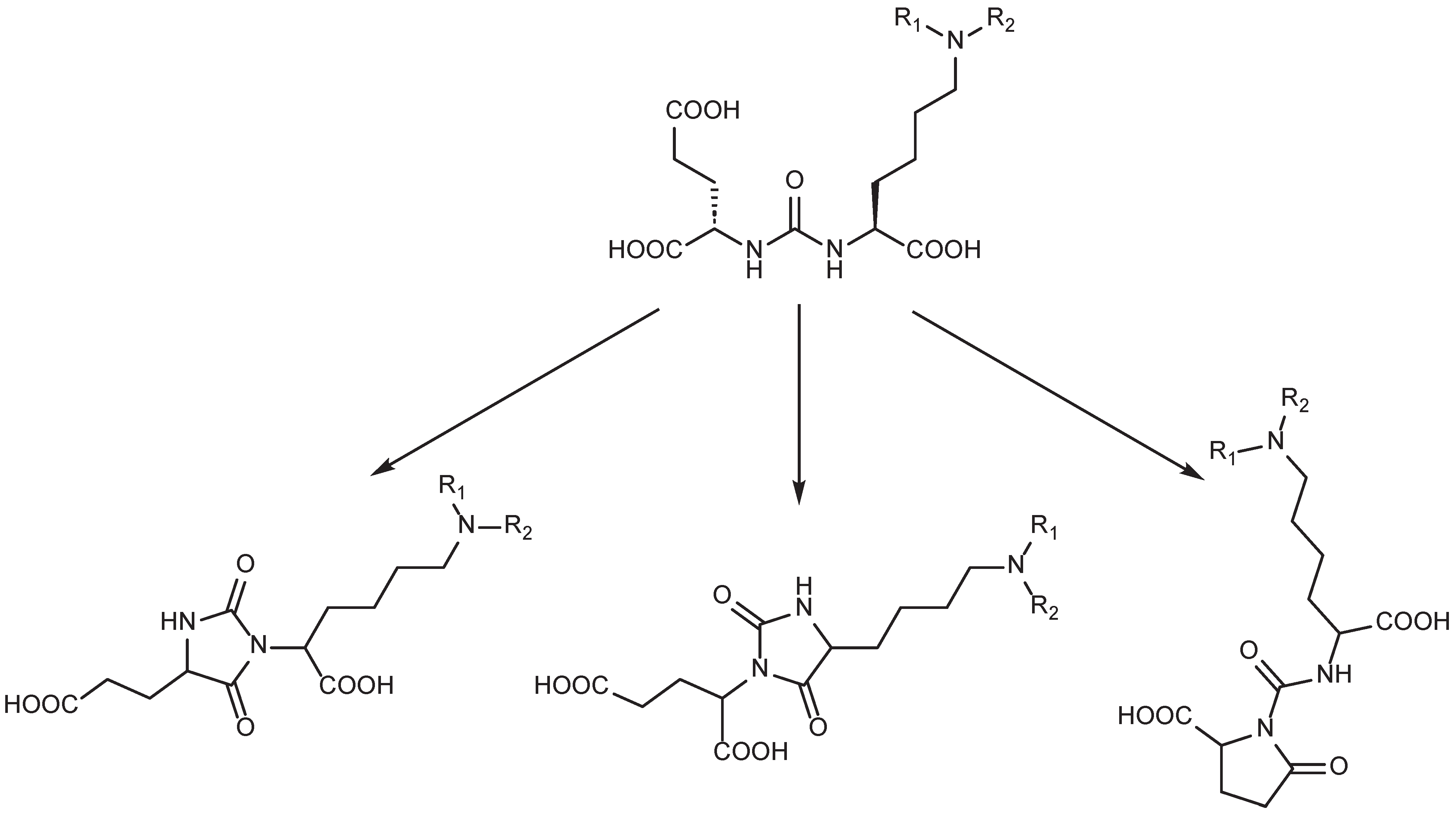

4. Modification of the ε-Amino Group of Lysine

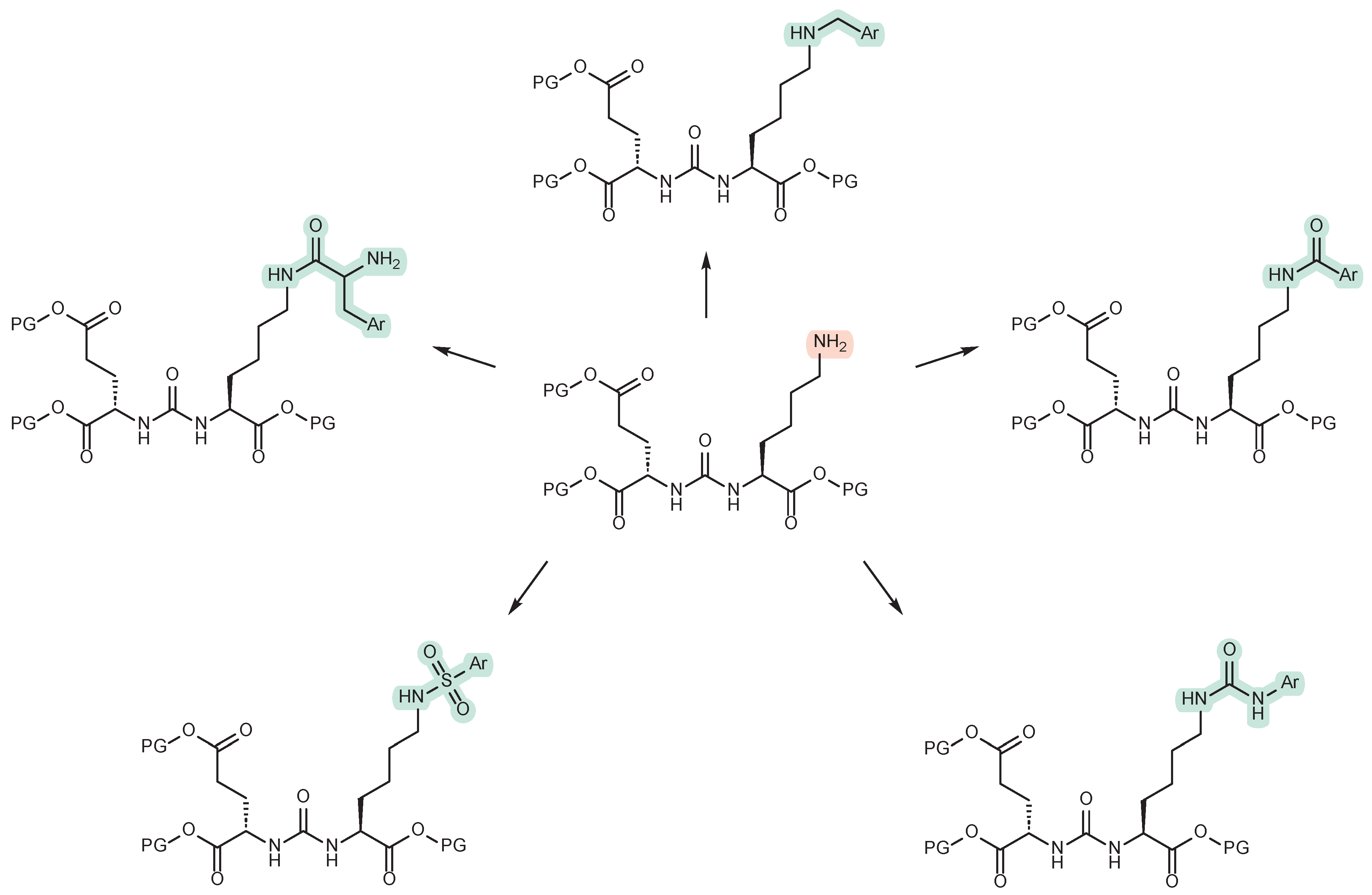

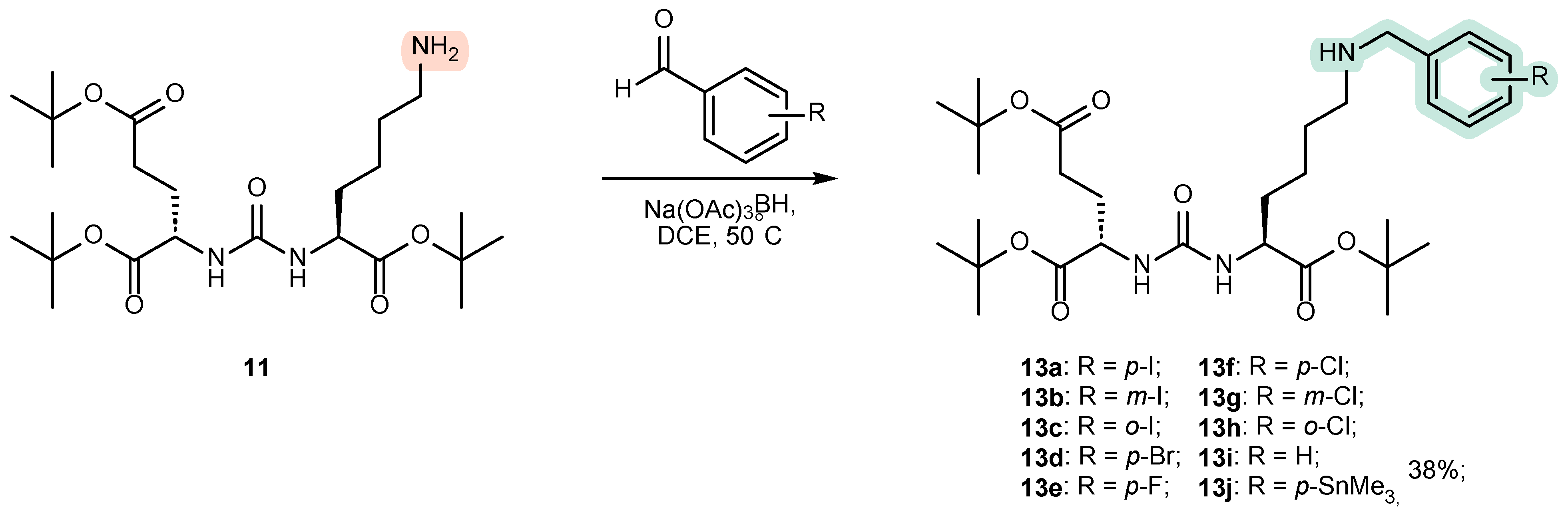

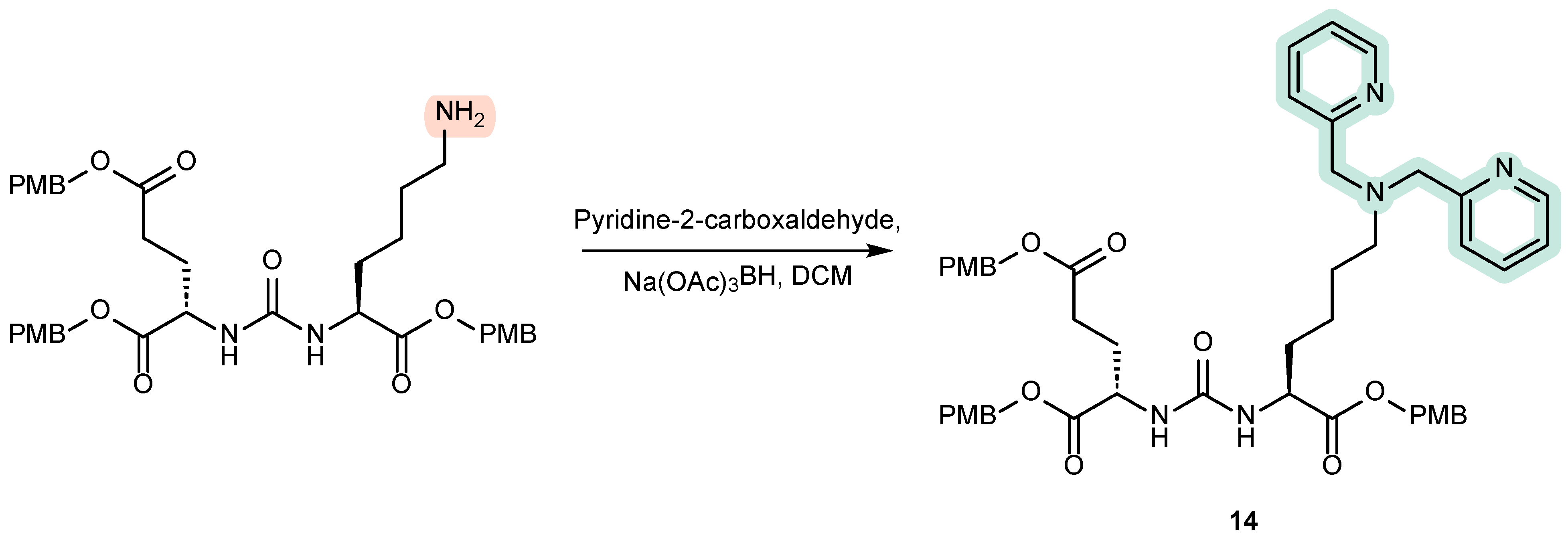

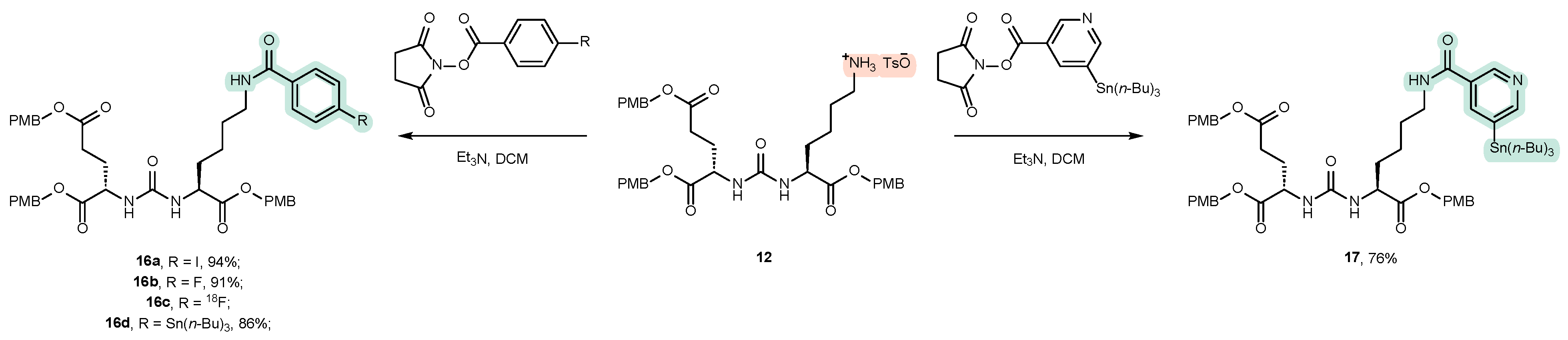

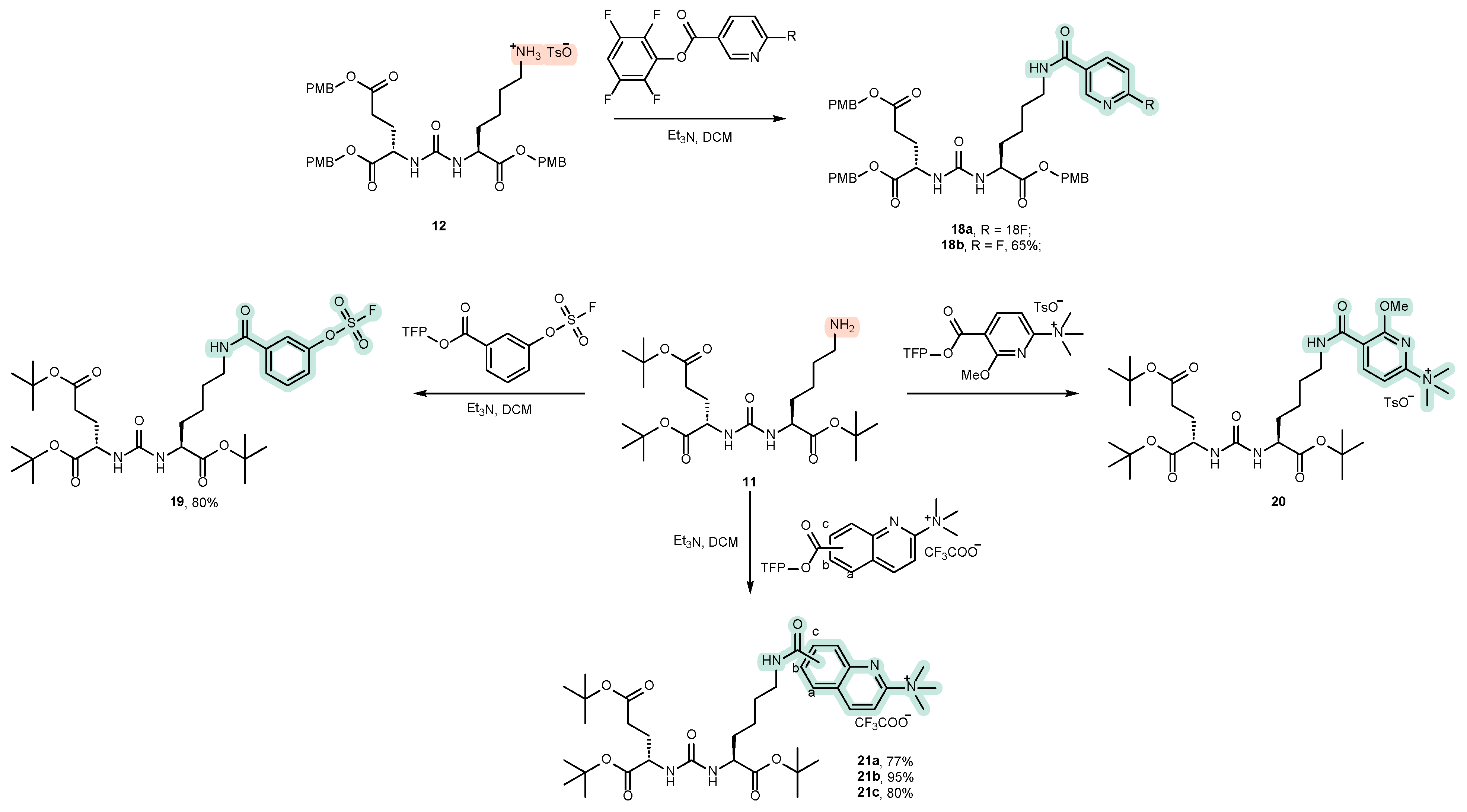

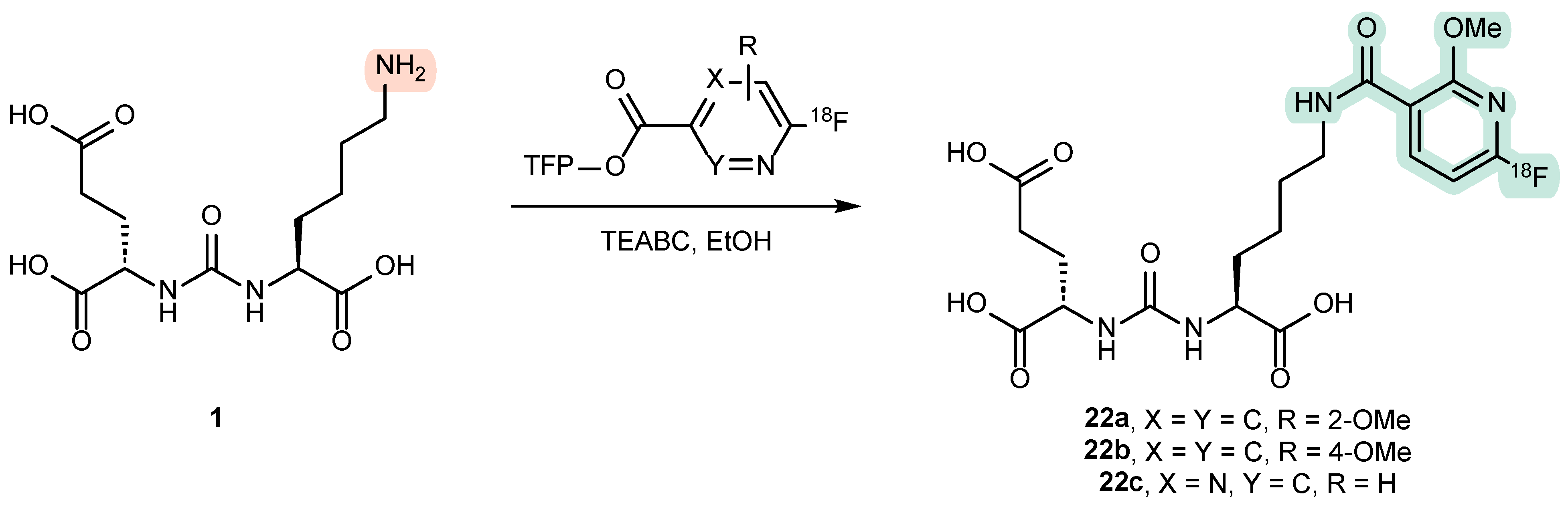

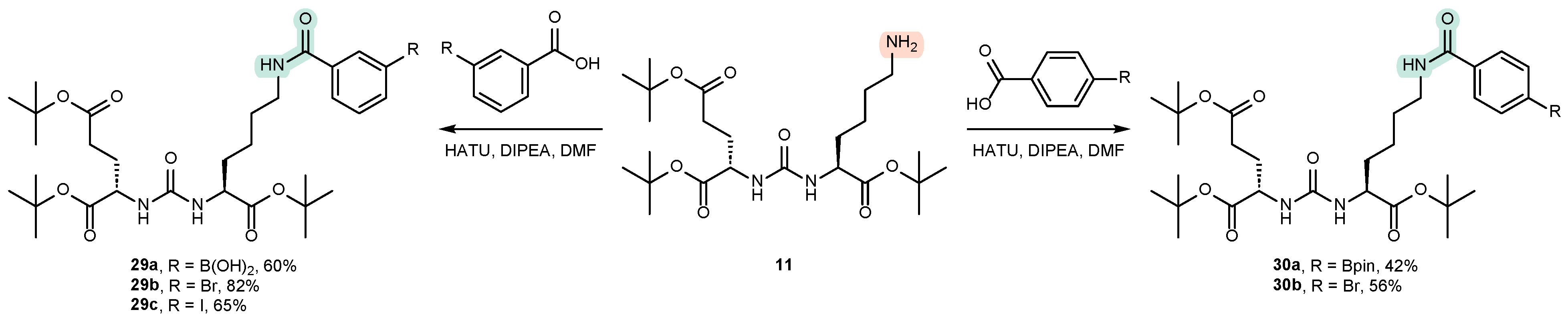

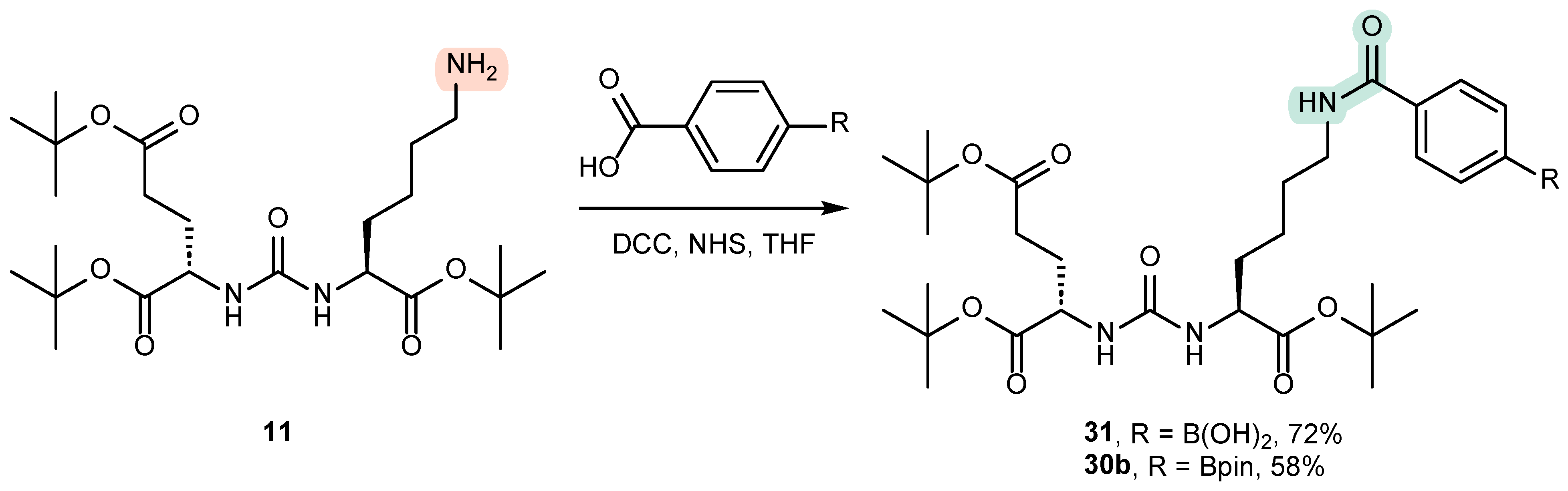

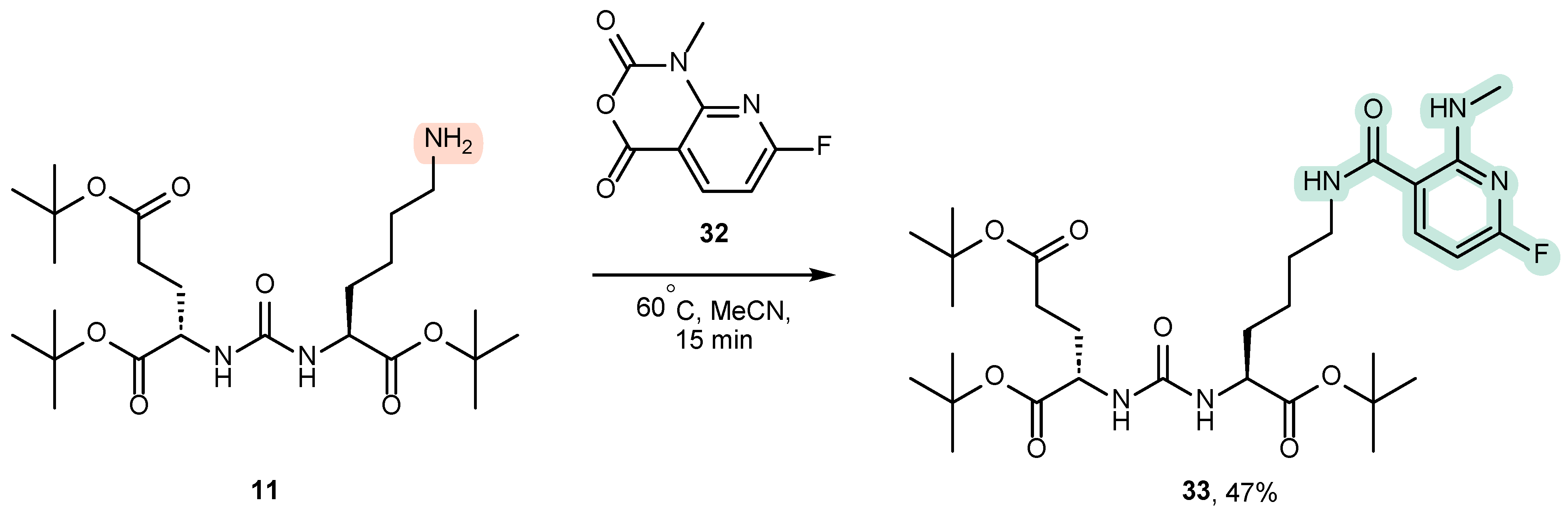

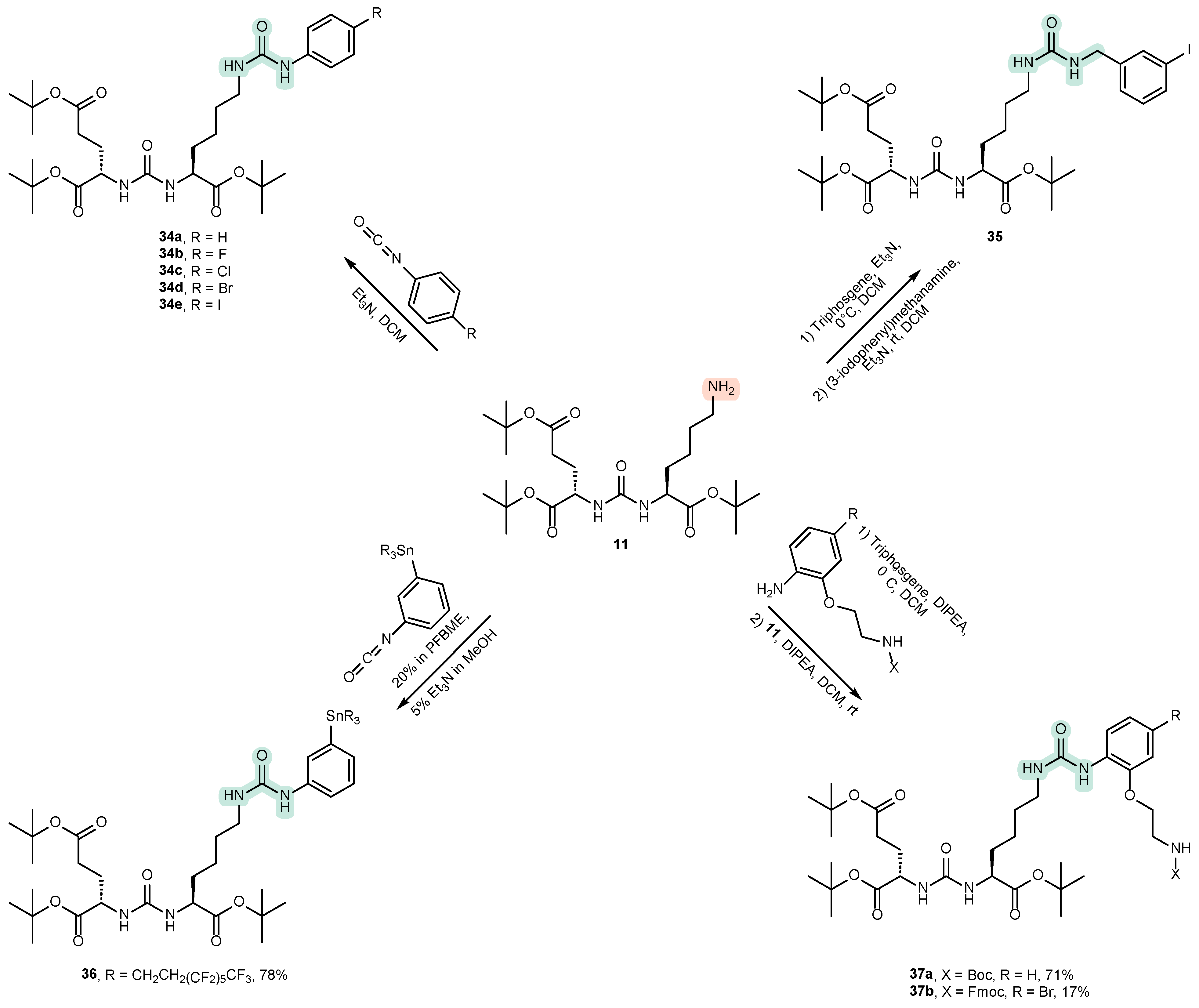

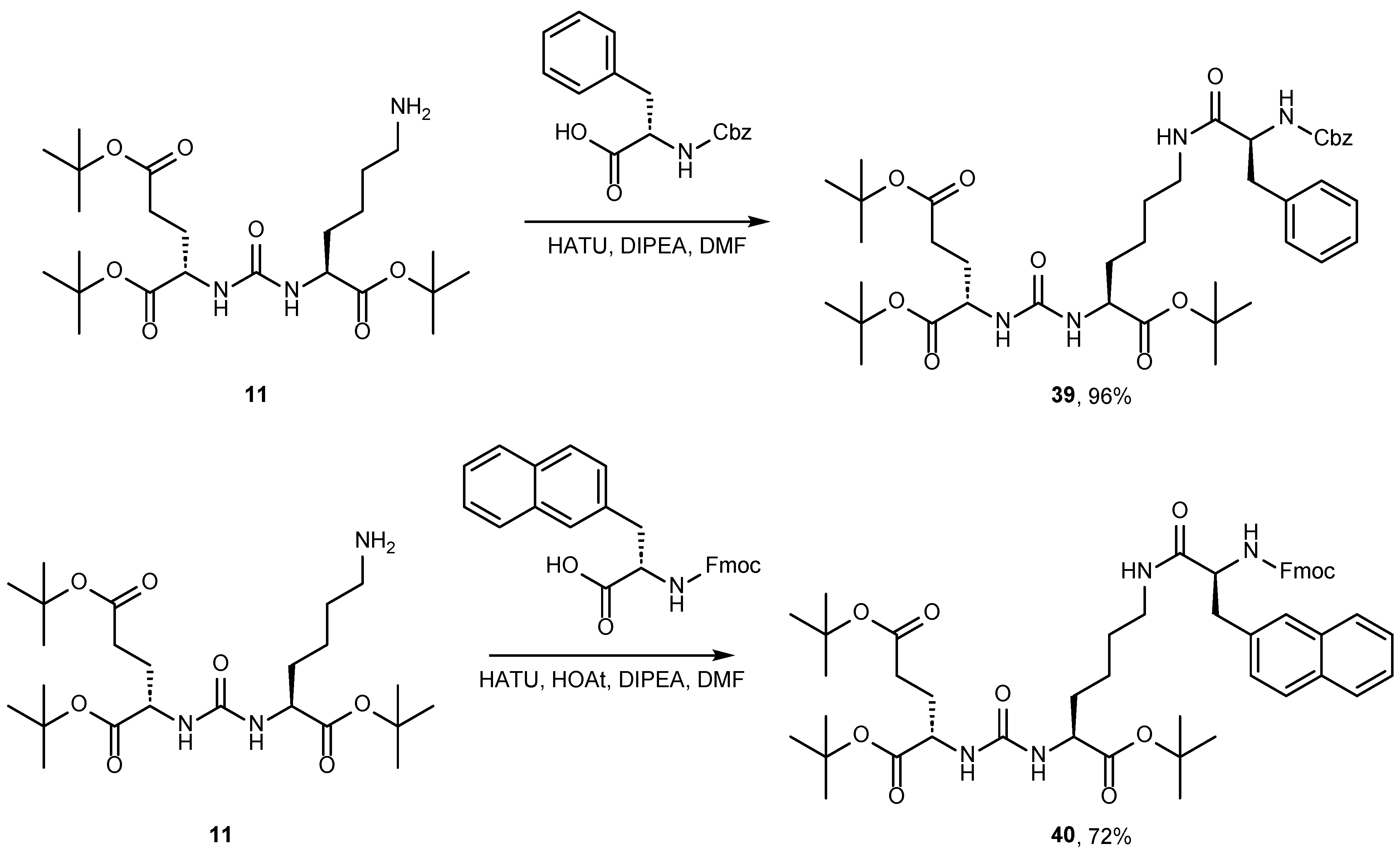

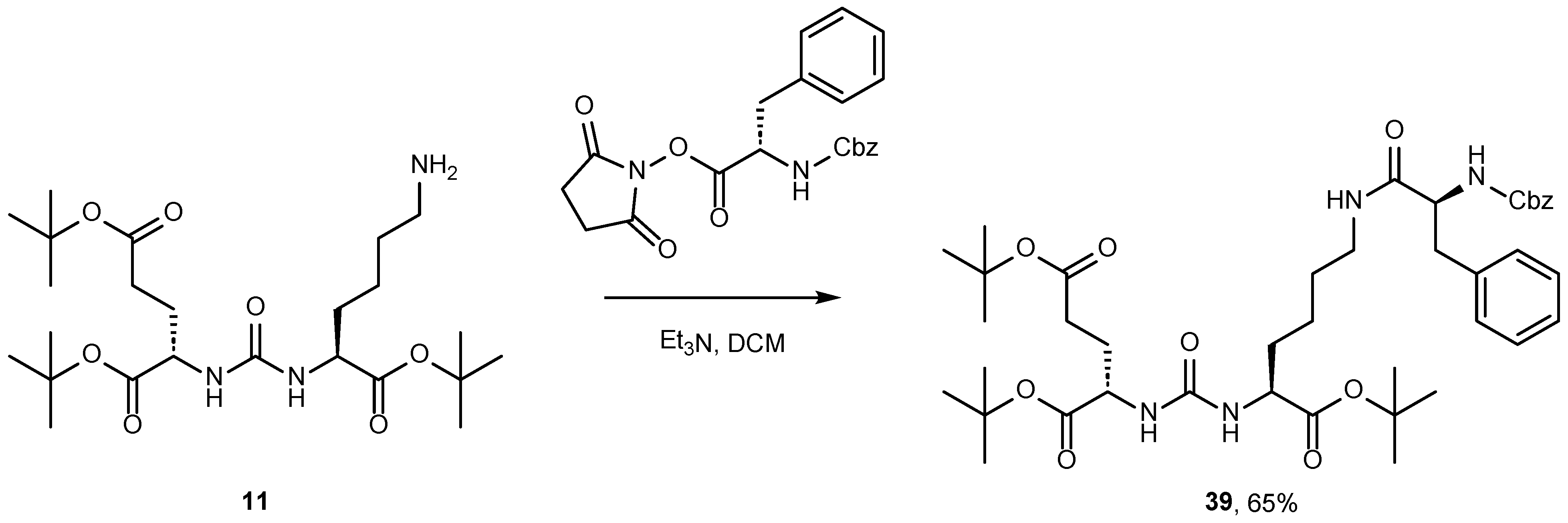

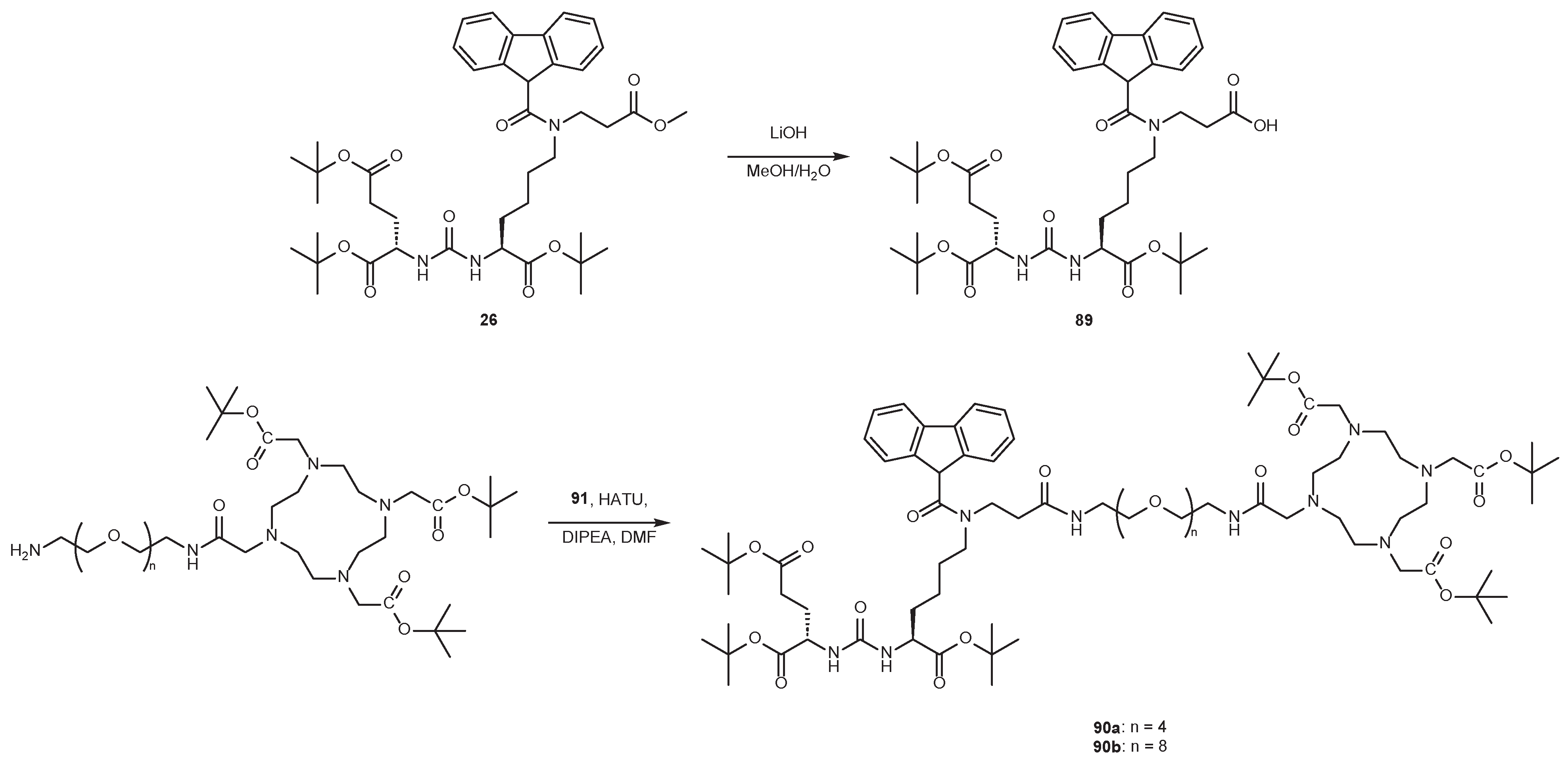

4.1. Existing Synthetic Approaches to the Introduction of an Aromatic Fragment

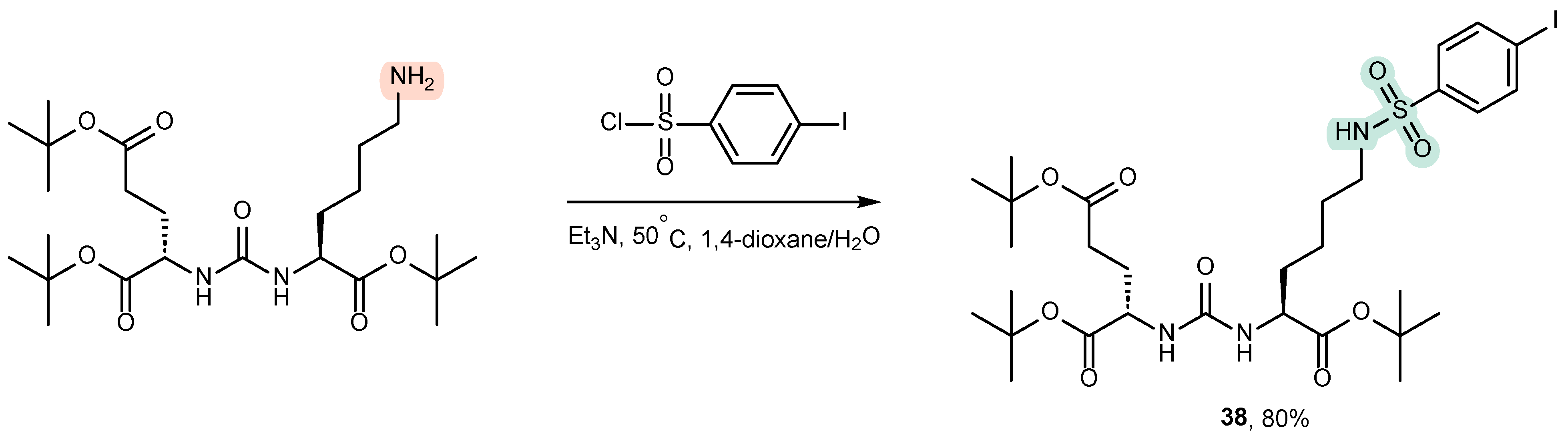

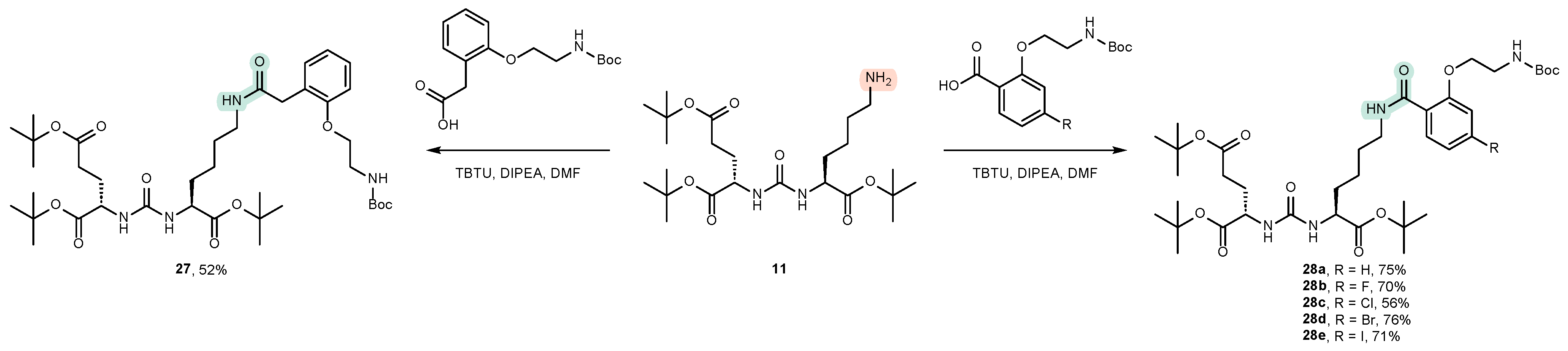

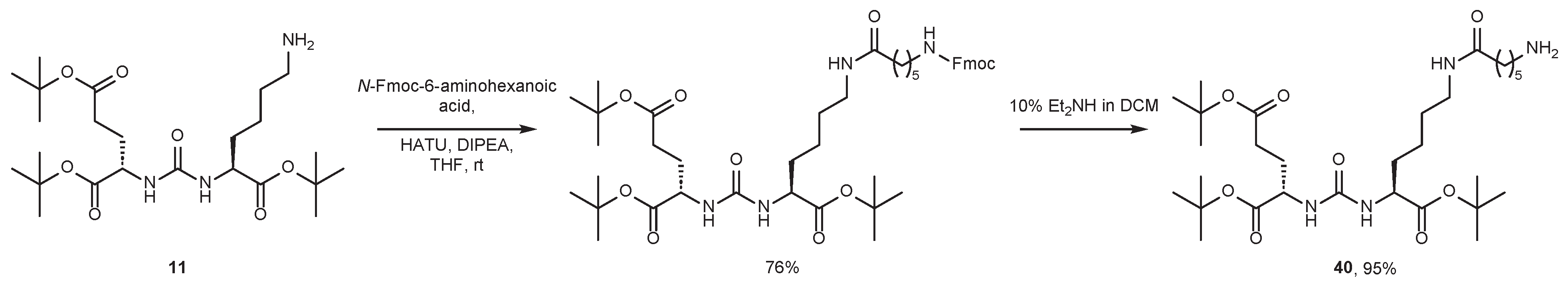

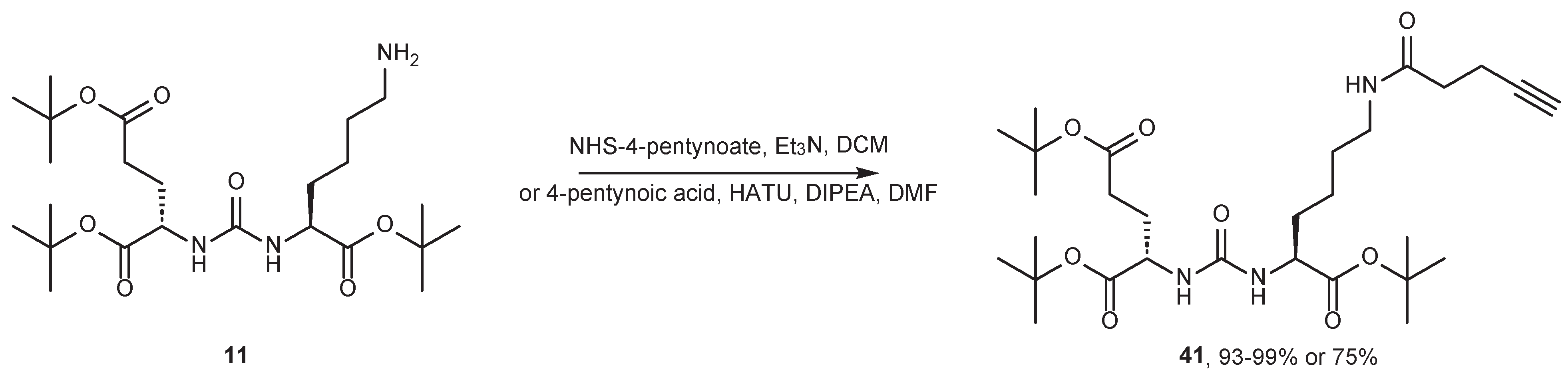

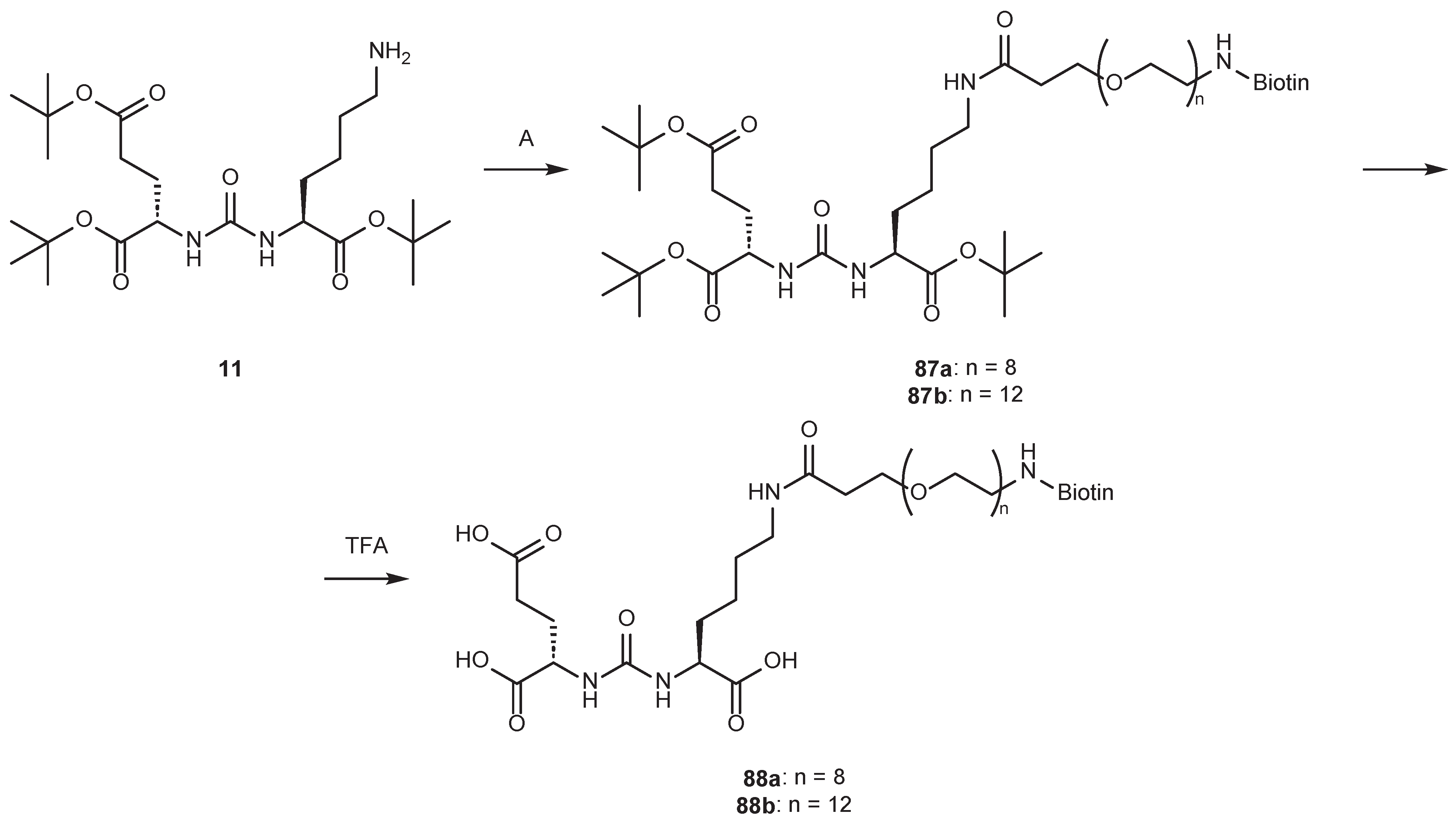

4.2. Existing Synthetic Approaches to Linker Introduction

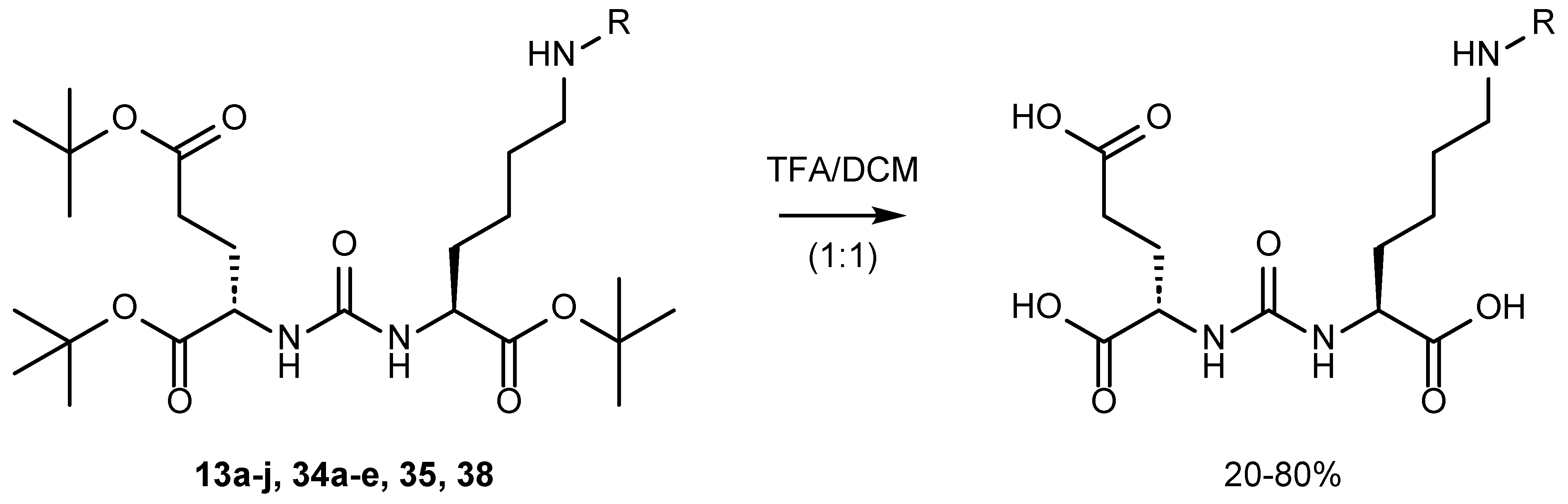

5. Approaches to Removing Protective Groups

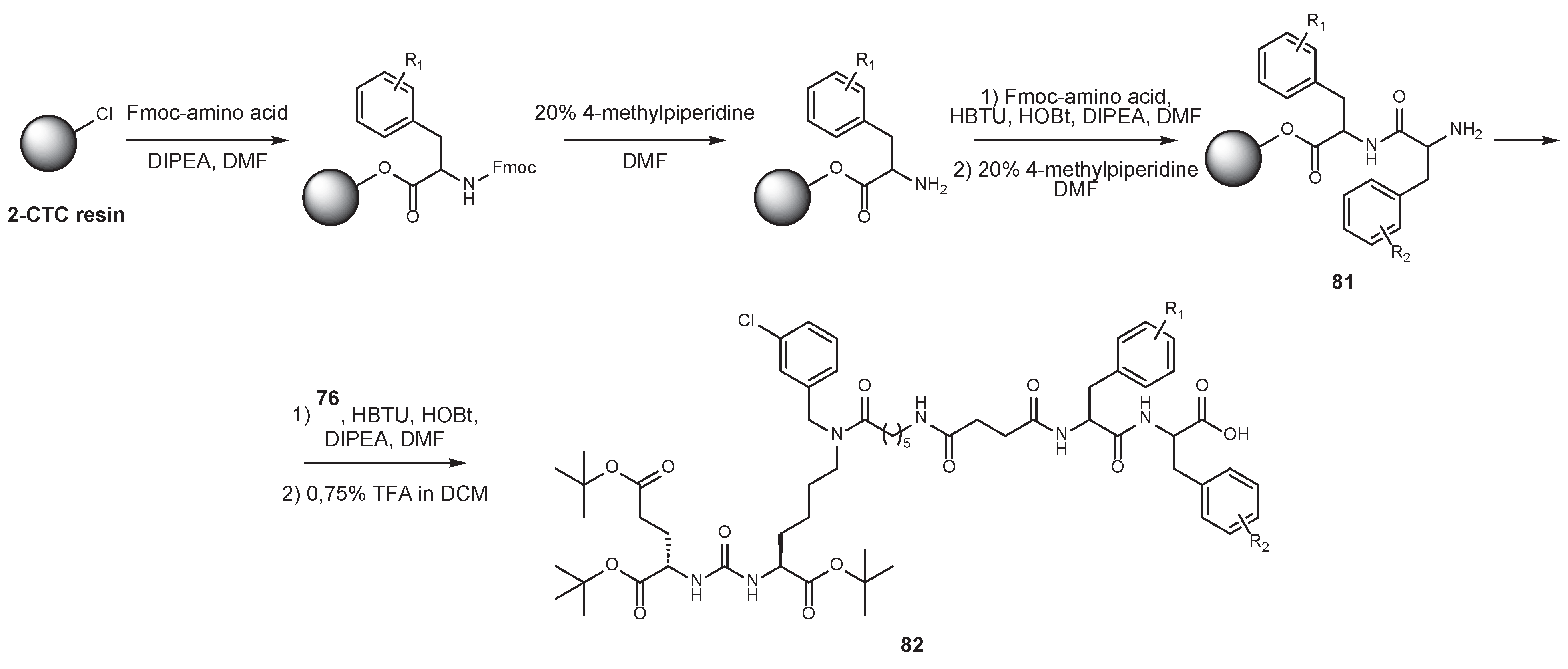

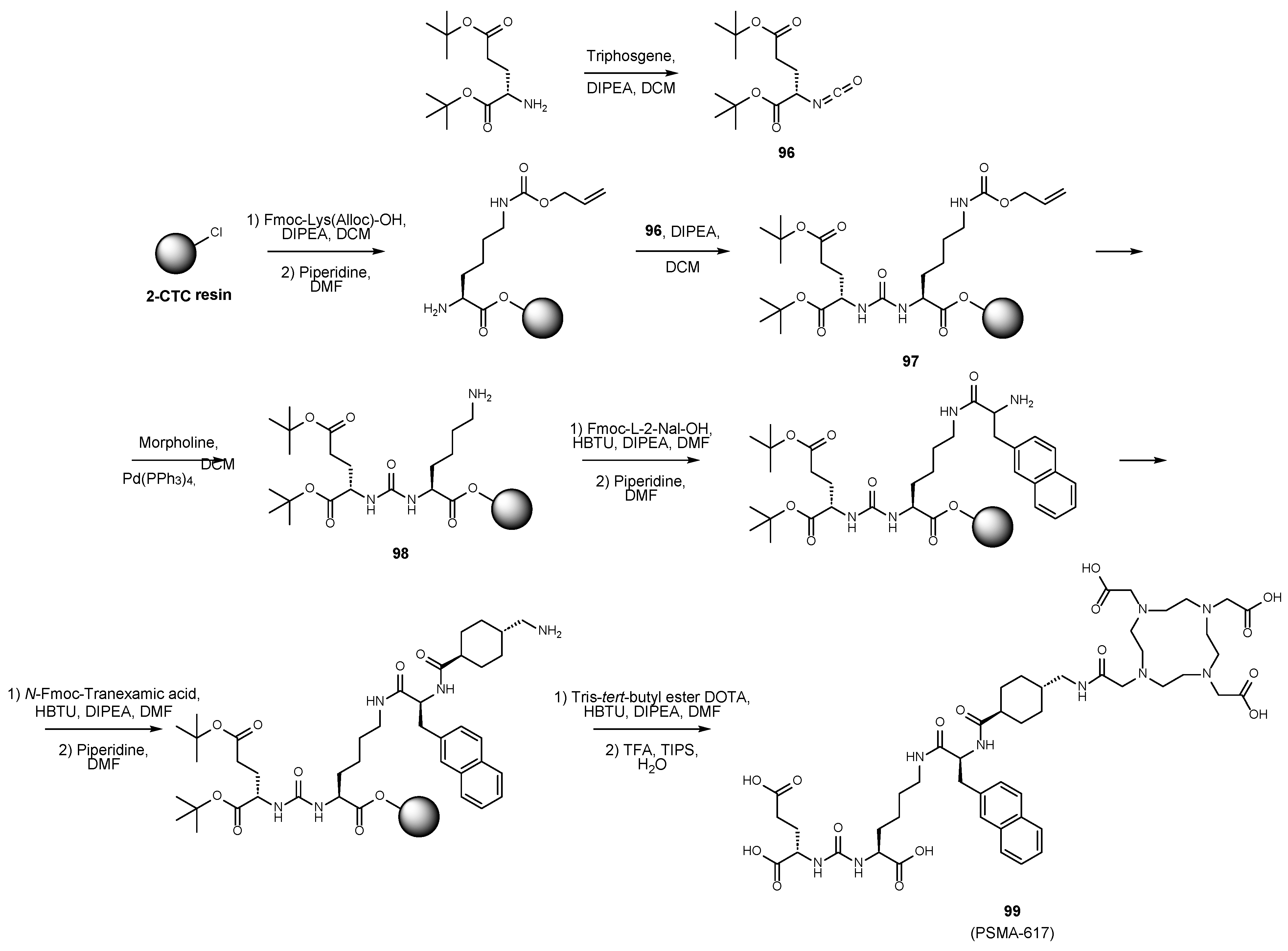

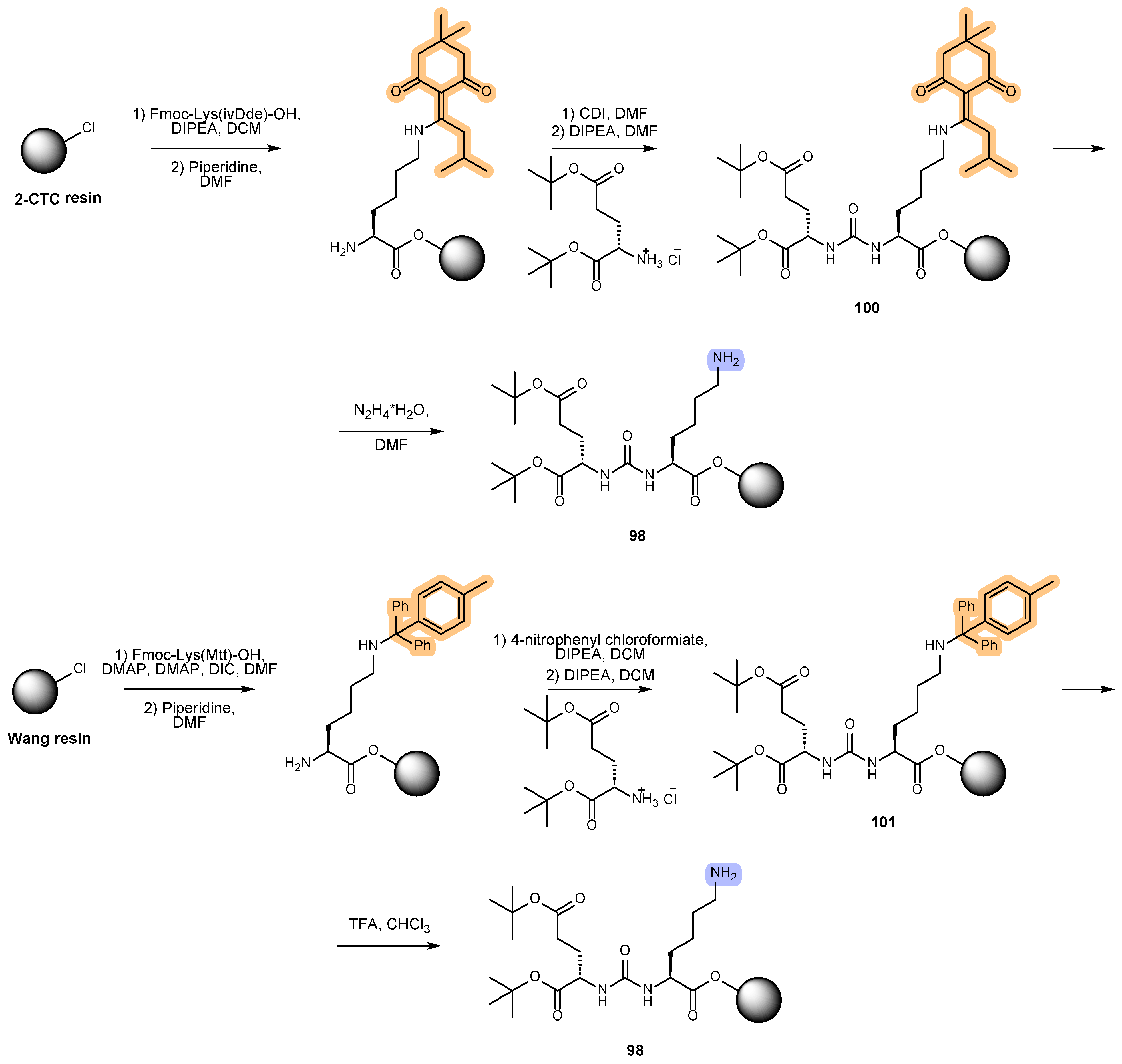

6. Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis as an Approach to Synthesis of PSMA Ligands

7. Alternative Approaches to the Modification of DCL Urea

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ar | Aryl |

| Boc | tert-Butoxycaronyl |

| Bpin | Pinacolborane group |

| tBu | tert-Butyl |

| Cbz, Z | Benzyloxycarbonyl |

| CDI | Carbonyldiimidazole |

| DBU | 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene |

| DCC | N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide |

| DCE | Dichloroethane |

| DCL | N-[N-[(S)-1,3-Dicarboxypropyl]carbamoyl]-(S)-L-lysine |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| Dde | 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl |

| DIPEA | N,N-Diisopropylethylamine |

| DMAc | N,N-Dimethylacetamide |

| DMAP | 4-(Dimethylamino)pyridine |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| DSC | N,N′-Disuccinimidyl carbonate |

| DSS | Disuccinimidyl suberate |

| Fmoc | Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl group |

| GRPr | Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor |

| HATU | 1-[Bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate |

| HBTU | N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate |

| HOAt | 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole |

| HOBt | 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole |

| MeOTf | Methyl trifluoromethanesulfonate |

| NAAG | N-Acetylaspartylglutamate |

| NHS | N-Hyrdoxysuccinimid |

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PFBME | Perfluorobutyl methyl ether |

| Pfp | Pentafluorophenyl group |

| PG | Protective group |

| PMB | para-Methoxybenzyl |

| PSMA | Prostate specific membrane antigen |

| PyBOP | (Benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate |

| rt | Room temperature |

| STAB | Sodium triacetoxyborohydride |

| TBTU | N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium tetrafluoroborate |

| TEABC | Tetraethylammonium bicarbonate |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TFP | 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-phenyl |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| TIBS | Tri-iso-butylsilane |

| TIPS | Tri-iso-propylsilane |

| Trt | Trityl group |

| TsOH | para-Toluenesulfonic acid |

| TSTU | N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(N-succinimidyl)uronium tetrafluoroborate |

| ZBG | Zinc-binding group |

References

- Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Soerjomataram, I., and Jemal, A., CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, vol. 74, no. 3, p. 229. [CrossRef]

- Potosky, A. L., Davis, W. W., Hoffman, R. M., Stanford, J. L., Stephenson, R. A., Penson, D. F., and Harlan, L. C., JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004, vol. 96, no. 18, p. 1358. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. G., Canfield, S. E., and Du, X. L., Cancer. 2009, vol. 115, no. 11, p. 2388. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. M., Chen, V. E., Miller, R. C., and Greenberger, B. A., Res Rep Urol. 2020, vol. 12, p. 533. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, M., and Nakayama, J., Cancer Res. 1997, vol. 57, no. 12, p. 2321.

- Mhawech-Fauceglia, P., Zhang, S., Terracciano, L., Sauter, G., Chadhuri, A., Herrmann, F. R., and Penetrante, R., Histopathology. 2007, vol. 50, no. 4, p. 472. [CrossRef]

- Lauri, C., Chiurchioni, L., Russo, V. M., Zannini, L., and Signore, A., J Clin Med. 2022, vol. 11, no. 21, p. 6590. [CrossRef]

- Bakht, M. K., and Beltran, H., Nat Rev Urol. 2025, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 26. [CrossRef]

- Barinka, C., Rojas, C., Slusher, B., and Pomper, M., Curr Med Chem. 2012, vol. 19, no. 6, p. 856. [CrossRef]

- Machulkin, A. E., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Aladinskaya, A. V., Veselov, M. S., Aladinskiy, V. A., Beloglazkina, E. K., Koteliansky, V. E., Shakhbazyan, A. G., Sandulenko, Y. B., and Majouga, A. G., J Drug Target. 2016, vol. 24, no. 8, p. 679. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, S. A., Zyk, N. Y., Machulkin, A. E., Beloglazkina, E. K., and Majouga, A. G., Eur J Med Chem. 2021, vol. 225, p. 113752. [CrossRef]

- Ha, H., Kwon, H., Lim, T., Jang, J., Park, S.-K., and Byun, Y., Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2021, vol. 31, no. 6, p. 525. [CrossRef]

- Capasso, G., Stefanucci, A., and Tolomeo, A., Eur J Med Chem. 2024, vol. 263, p. 115966. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J., Zhang, J., Wen, W., Qin, W., and Chen, X., Theranostics. 2024, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 2736. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, R., Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2024, vol. 72, no. 2, p. c23. [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, Z., Zargari, F., Nowroozi, A., and Bavi, O., Biophys Rev. 2022, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 303. [CrossRef]

- Hennrich, U., and Eder, M., Pharmaceuticals. 2021, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 713. [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J., Agrawal, S., Gittleman, H., Fiero, M. H., Subramaniam, S., John, C., Chen, W., Ricks, T. K., Niu, G., Fotenos, A., Wang, M., Chiang, K., Pierce, W. F., Suzman, D. L., Tang, S., Pazdur, R., Amiri-Kordestani, L., Ibrahim, A., and Kluetz, P. G., Clinical Cancer Research. 2023, vol. 29, no. 9, p. 1651. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. J., Rowe, S. P., Gorin, M. A., Saperstein, L., Pouliot, F., Josephson, D., Wong, J. Y. C., Pantel, A. R., Cho, S. Y., Gage, K. L., Piert, M., Iagaru, A., Pollard, J. H., Wong, V., Jensen, J., Lin, T., Stambler, N., Carroll, P. R., and Siegel, B. A., Clinical Cancer Research. 2021, vol. 27, no. 13, p. 3674. [CrossRef]

- Uspenskaya, A. A., Nimenko, E. A., Machulkin, A. E., Beloglazkina, E. K., and Majouga, A. G., Curr Med Chem. 2022, vol. 29, no. 2, p. 268. [CrossRef]

- Berrens, A.-C., Knipper, S., Marra, G., van Leeuwen, P. J., van der Mierden, S., Donswijk, M. L., Maurer, T., van Leeuwen, F. W. B., and van der Poel, H. G., Eur Urol Open Sci. 2023, vol. 54, p. 43. [CrossRef]

- Mesters, J. R., Barinka, C., Li, W., Tsukamoto, T., Majer, P., Slusher, B. S., Konvalinka, J., and Hilgenfeld, R., EMBO J. 2006, vol. 25, no. 6, p. 1375. [CrossRef]

- Bařinka, C., Rovenská, M., Mlčochová, P., Hlouchová, K., Plechanovová, A., Majer, P., Tsukamoto, T., Slusher, B. S., Konvalinka, J., and Lubkowski, J., J Med Chem. 2007, vol. 50, no. 14, p. 3267. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. I., Bennett, M. J., Thomas, L. M., and Bjorkman, P. J., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005, vol. 102, no. 17, p. 5981. [CrossRef]

- Kozikowski, A. P., Nan, F., Conti, P., Zhang, J., Ramadan, E., Bzdega, T., Wroblewska, B., Neale, J. H., Pshenichkin, S., and Wroblewski, J. T., J Med Chem. 2001, vol. 44, no. 3, p. 298. [CrossRef]

- Kozikowski, A. P., Zhang, J., Nan, F., Petukhov, P. A., Grajkowska, E., Wroblewski, J. T., Yamamoto, T., Bzdega, T., Wroblewska, B., and Neale, J. H., J Med Chem. 2004, vol. 47, no. 7, p. 1729. [CrossRef]

- Murelli, R. P., Zhang, A. X., Michel, J., Jorgensen, W. L., and Spiegel, D. A., J Am Chem Soc. 2009, vol. 131, no. 47, p. 17090. [CrossRef]

- McEnaney, P. J., Fitzgerald, K. J., Zhang, A. X., Douglass, E. F., Shan, W., Balog, A., Kolesnikova, M. D., and Spiegel, D. A., J Am Chem Soc. 2014, vol. 136, no. 52, p. 18034. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A. K., Rolfe, B. E., Russell, P. J., Tse, B. W.-C., Whittaker, A. K., Fuchs, A. V., and Thurecht, K. J., Polym. Chem. 2014, vol. 5, no. 24, p. 6932. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R. K., Basu, U., Ahmad, A., Sarkar, S., Kumar, A., Surnar, B., Ansari, S., Wilczek, K., Ivan, M. E., Marples, B., Kolishetti, N., and Dhar, S., Biomaterials. 2018, vol. 187, p. 117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., McNitt, C. D., Wang, H., Ma, X., Scarry, S. M., Wu, Z., Popik, V. V., and Li, Z., Chemical Communications. 2018, vol. 54, no. 56, p. 7810. [CrossRef]

- Machulkin, A. E., Skvortsov, D. A., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Ber, A. P., Kavalchuk, M. V., Aladinskaya, A. V., Uspenskaya, A. A., Shafikov, R. R., Plotnikova, E. A., Yakubovskaya, R. I., Nimenko, E. A., Zyk, N. U., Beloglazkina, E. K., Zyk, N. V., Koteliansky, V. E., and Majouga, A. G., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2019, vol. 29, no. 16, p. 2229. [CrossRef]

- Lesniak, W. G., Boinapally, S., Banerjee, S. R., Behnam Azad, B., Foss, C. A., Shen, C., Lisok, A., Wharram, B., Nimmagadda, S., and Pomper, M. G., Mol Pharm. 2019, vol. 16, no. 6, p. 2590. [CrossRef]

- Ivanenkov, Y. A., Machulkin, A. E., Garanina, A. S., Skvortsov, D. A., Uspenskaya, A. A., Deyneka, E. V., Trofimenko, A. V., Beloglazkina, E. K., Zyk, N. V., Koteliansky, V. E., Bezrukov, D. S., Aladinskaya, A. V., Vorobyeva, N. S., Puchinina, M. M., Riabykh, G. K., Sofronova, A. A., Malyshev, A. S., and Majouga, A. G., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2019, vol. 29, no. 10, p. 1246. [CrossRef]

- Son, S.-H., Kwon, H., Ahn, H.-H., Nam, H., Kim, K., Nam, S., Choi, D., Ha, H., Minn, I., and Byun, Y., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020, vol. 30, no. 3, p. 126894. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D., Duan, X., Gan, Q., Zhang, X., and Zhang, J., Molecules. 2020, vol. 25, no. 23, p. 5548. [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, V. I., Szymanski, W., van den Berg, K., Mulder, C., Kobauri, P., Helbert, H., van der Born, D., Reeβing, F., Huizing, A., Klopstra, M., Samplonius, D. F., Antunes, I. F., Sijbesma, J. W. A., Luurtsema, G., Helfrich, W., Visser, T. J., Feringa, B. L., and Elsinga, P. H., Chemistry – A European Journal. 2020, vol. 26, no. 47, p. 10871. [CrossRef]

- Machulkin, A. E., Shafikov, R. R., Uspenskaya, A. A., Petrov, S. A., Ber, A. P., Skvortsov, D. A., Nimenko, E. A., Zyk, N. U., Smirnova, G. B., Pokrovsky, V. S., Abakumov, M. A., Saltykova, I. V., Akhmirov, R. T., Garanina, A. S., Polshakov, V. I., Saveliev, O. Y., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Aladinskaya, A. V., Finko, A. V., Yamansarov, E. U., Krasnovskaya, O. O., Erofeev, A. S., Gorelkin, P. V., Dontsova, O. A., Beloglazkina, E. K., Zyk, N. V., Khazanova, E. S., and Majouga, A. G., J Med Chem. 2021, vol. 64, no. 8, p. 4532. [CrossRef]

- Maujean, T., Marchand, P., Wagner, P., Riché, S., Boisson, F., Girard, N., Bonnet, D., and Gulea, M., Chemical Communications. 2022, vol. 58, no. 79, p. 11151. [CrossRef]

- Mixdorf, J. C., Hoffman, S. L. V., Aluicio-Sarduy, E., Barnhart, T. E., Engle, J. W., and Ellison, P. A., J Org Chem. 2023, vol. 88, no. 4, p. 2089. [CrossRef]

- Maresca, K. P., Hillier, S. M., Femia, F. J., Keith, D., Barone, C., Joyal, J. L., Zimmerman, C. N., Kozikowski, A. P., Barrett, J. A., Eckelman, W. C., and Babich, J. W., J Med Chem. 2009, vol. 52, no. 2, p. 347. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yang, D., Che, X., Wang, J., Chen, F., and Song, X., Journal of Dalian Medical University. 2012, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Cleeren, F., Lecina, J., Billaud, E. M. F., Ahamed, M., Verbruggen, A., and Bormans, G. M., Bioconjug Chem. 2016, vol. 27, no. 3, p. 790. [CrossRef]

- Frei, A., Fischer, E., Childs, B. C., Holland, J. P., and Alberto, R., Dalton Transactions. 2019, vol. 48, no. 39, p. 14600. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J., Fischer, E., Rosillo-Lopez, M., Salzmann, C. G., and Holland, J. P., Chem Sci. 2019, vol. 10, no. 38, p. 8880. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, P. T., Dall’Angelo, S., Fleming, I. N., Piras, M., Zanda, M., and O’Hagan, D., Org Biomol Chem. 2019, vol. 17, no. 6, p. 1480. [CrossRef]

- Yap, S. Y., Savoie, H., Renard, I., Burke, B. P., Sample, H. C., Michue-Seijas, S., Archibald, S. J., Boyle, R. W., and Stasiuk, G. J., Chemical Communications. 2020, vol. 56, no. 75, p. 11090. [CrossRef]

- Søborg Pedersen, K., Baun, C., Michaelsen Nielsen, K., Thisgaard, H., Ingemann Jensen, A., and Zhuravlev, F., Molecules. 2020, vol. 25, no. 5, p. 1104. [CrossRef]

- Lahnif, H., Grus, T., Pektor, S., Greifenstein, L., Schreckenberger, M., and Rösch, F., Molecules. 2021, vol. 26, no. 21, p. 6332. [CrossRef]

- d’Orchymont, F., and Holland, J. P., Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2022, vol. 61, no. 29, p. e202204072. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Gai, Y., Li, M., Fang, H., Xiang, G., and Ma, X., Bioorg Med Chem. 2022, vol. 60, p. 116687. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, K., Li, Y., Xu, X., and Xu, B., Molecules. 2022, vol. 27, no. 9, p. 2736. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Wu, Z., Zhu, H., Zhang, X., Yu, Y., and Chen, W., J Med Chem. 2024, vol. 67, no. 21, p. 19586. [CrossRef]

- Weineisen, M., Simecek, J., Schottelius, M., Schwaiger, M., and Wester, H.-J., EJNMMI Res. 2014, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 63. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-H., Hong, M. K., Kim, Y. J., Lee, Y.-S., Lee, D. S., Chung, J.-K., and Jeong, J. M., Bioorg Med Chem. 2018, vol. 26, no. 9, p. 2501. [CrossRef]

- Gade, N. R., Kaur, J., Bhardwaj, A., Ebrahimi, E., Dufour, J., Wuest, M., and Wuest, F., ACS Med Chem Lett. 2023, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 943. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Benson, S., Mendive-Tapia, L., Nestoros, E., Lochenie, C., Seah, D., Chang, K. Y., Feng, Y., and Vendrell, M., Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2024, vol. 63, no. 30, p. e202404587. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zhu, B., Jiang, F., Chen, X., Wang, G., Ding, N., Song, S., Xu, X., and Zhang, W., Bioorg Med Chem. 2024, vol. 106, p. 117753. [CrossRef]

- Kapcan, E., Lake, B., Yang, Z., Zhang, A., Miller, M. S., and Rullo, A. F., Biochemistry. 2021, vol. 60, no. 19, p. 1447. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Tang, L., Liu, Y., Wu, H., Liu, Z., Li, J., Pan, Y., and Akkaya, E. U., Chemical Communications. 2022, vol. 58, no. 12, p. 1902. [CrossRef]

- Lake, B., Serniuck, N., Kapcan, E., Wang, A., and Rullo, A. F., ACS Chem Biol. 2020, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 1089. [CrossRef]

- Leamon, C. P., Reddy, J. A., Bloomfield, A., Dorton, R., Nelson, M., Vetzel, M., Kleindl, P., Hahn, S., Wang, K., and Vlahov, I. R., Bioconjug Chem. 2019, vol. 30, no. 6, p. 1805. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J. J., Wuest, M., Wagner, M., Bhardwaj, A., Wängler, C., Wängler, B., Valliant, J. F., Schirrmacher, R., and Wuest, F., J Med Chem. 2021, vol. 64, no. 21, p. 15671. [CrossRef]

- Hensbergen, A. W., Buckle, T., van Willigen, D. M., Schottelius, M., Welling, M. M., van der Wijk, F. A., Maurer, T., van der Poel, H. G., van der Pluijm, G., van Weerden, W. M., Wester, H.-J., and van Leeuwen, F. W. B., Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2020, vol. 61, no. 2, p. 234. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T. H., Eno-Amooquaye, E. A., Searle, F., Browne, P. J., Osborn, H. M. I., and Burke, P. J., J Med Chem. 1999, vol. 42, no. 6, p. 951. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. R., Foss, C. A., Castanares, M., Mease, R. C., Byun, Y., Fox, J. J., Hilton, J., Lupold, S. E., Kozikowski, A. P., and Pomper, M. G., J Med Chem. 2008, vol. 51, no. 15, p. 4504. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Foss, C. A., Byun, Y., Nimmagadda, S., Pullambhatla, M., Fox, J. J., Castanares, M., Lupold, S. E., Babich, J. W., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., J Med Chem. 2008, vol. 51, no. 24, p. 7933. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Pullambhatla, M., Banerjee., S. R., Byun, Y., Stathis, M., Rojas, C., Slusher, B. S., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., Bioconjug Chem. 2012, vol. 23, no. 12, p. 2377. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Pullambhatla, M., Foss, C. A., Byun, Y., Nimmagadda, S., Senthamizhchelvan, S., Sgouros, G., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., Clinical Cancer Research. 2011, vol. 17, no. 24, p. 7645. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ishai, D., and Berger, A., J Org Chem. 1952, vol. 17, no. 12, p. 1564. [CrossRef]

- Chelucci, G., Falorni, M., and Giacomelli, G., Synthesis (Stuttg). 1990, vol. 1990, no. 12, p. 1121. [CrossRef]

- Yajima, H., Fujii, N., Ogawa, H., and Kawatani, H., J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1974, no. 3, p. 107. [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z., Wu, Q., Zhang, F., Cao, Y., Liu, C., Shieh, W.-C., Xue, S., McKenna, J., Prasad, K., Prashad, M., Baeschlin, D., and Namoto, K., J Org Chem. 2008, vol. 73, no. 22, p. 9016. [CrossRef]

- Felber, M., Bauwens, M., Mateos, J. M., Imstepf, S., Mottaghy, F. M., and Alberto, R., Chemistry – A European Journal. 2015, vol. 21, no. 16, p. 6090. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-D., Chung, H.-J., Lee, S. J., Lee, S.-H., Jeong, B.-H., and Kim, H.-K., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018, vol. 28, no. 4, p. 572. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. Do, Oh, J. M., La, M. T., Chung, H. J., Lee, S. J., Chun, S., Lee, S. H., Jeong, B. H., and Kim, H. K., Bioconjug Chem. 2018, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 90. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G., McDaniel, J. W., and Murphy, J. M., Org Lett. 2021, vol. 23, no. 2, p. 530. [CrossRef]

- Barinka, C., Byun, Y., Dusich, C. L., Banerjee, S. R., Chen, Y., Castanares, M., Kozikowski, A. P., Mease, R. C., Pomper, M. G., and Lubkowski, J., J Med Chem. 2008, vol. 51, no. 24, p. 7737. [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, S. A., Zhou, Z., Yang, J., Post, C. B., and Low, P. S., Mol Pharm. 2009, vol. 6, no. 3, p. 790. [CrossRef]

- Tykvart, J., Schimer, J., Bařinková, J., Pachl, P., Poštová-Slavětínská, L., Majer, P., Konvalinka, J., and Šácha, P., Bioorg Med Chem. 2014, vol. 22, no. 15, p. 4099. [CrossRef]

- Šácha, P., Knedlík, T., Schimer, J., Tykvart, J., Parolek, J., Navrátil, V., Dvořáková, P., Sedlák, F., Ulbrich, K., Strohalm, J., Majer, P., Šubr, V., and Konvalinka, J., Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016, vol. 55, no. 7, p. 2356. [CrossRef]

- Zyk, N. Y., Ber, A. P., Nimenko, E. A., Shafikov, R. R., Evteev, S. A., Petrov, S. A., Uspenskaya, A. A., Dashkova, N. S., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Skvortsov, D. A., Beloglazkina, E. K., Majouga, A. G., and Machulkin, A. E., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2022, vol. 71, p. 128840. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G., Maresca, K. P., Hillier, S. M., Zimmerman, C. N., Eckelman, W. C., Joyal, J. L., and Babich, J. W., Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013, vol. 23, no. 5, p. 1557. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y., Wang, X., Cui, M., Liu, Y., and Wang, B., Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2025, vol. 27, no. 4, p. 2260. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Wu, Y., Zeng, Q., Xie, T., Yao, S., Zhang, J., and Cui, M., J Med Chem. 2021, vol. 64, no. 7, p. 4179. [CrossRef]

- Krapf, P., Wicher, T., Zlatopolskiy, B. D., Ermert, J., and Neumaier, B., Pharmaceuticals. 2025, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 119. [CrossRef]

- Zlatopolskiy, B. D., Endepols, H., Krapf, P., Guliyev, M., Urusova, E. A., Richarz, R., Hohberg, M., Dietlein, M., Drzezga, A., and Neumaier, B., Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2019, vol. 60, no. 6, p. 817. [CrossRef]

- Cai, P., Tang, S., Xia, L., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Feng, Y., Liu, N., Chen, Y., and Zhou, Z., Mol Pharm. 2023, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 1435. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Xia, L., Li, H., Cai, P., Tang, S., Feng, Y., Liu, G., Chen, Y., Liu, N., Zhang, W., and Zhou, Z., EJNMMI Res. 2024, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y., Kimura, H., Sasaki, I., Watanabe, S., Ohshima, Y., Yagi, Y., Hattori, Y., Koda, M., Kawashima, H., Yasui, H., and Ishioka, N. S., Bioorg Med Chem. 2022, vol. 69, p. 116915. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Blaha, C., Santos, R., Huynh, T., Hayes, T. R., Beckford-Vera, D. R., Blecha, J. E., Hong, A. S., Fogarty, M., Hope, T. A., Raleigh, D. R., Wilson, D. M., Evans, M. J., VanBrocklin, H. F., Ozawa, T., and Flavell, R. R., Mol Pharm. 2019, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 3831. [CrossRef]

- Gröner, B., Willmann, M., Donnerstag, L., Urusova, E. A., Neumaier, F., Humpert, S., Endepols, H., Neumaier, B., and Zlatopolskiy, B. D., J Med Chem. 2023, vol. 66, no. 17, p. 12629. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A. C., and Valliant, J. F., J Org Chem. 2009, vol. 74, no. 21, p. 8133. [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z., Ploessl, K., Choi, S. R., Wu, Z., Zhu, L., and Kung, H. F., Nucl Med Biol. 2018, vol. 59, p. 36. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X., Zha, Z., Ploessl, K., Choi, S. R., Zhao, R., Alexoff, D., Zhu, L., and Kung, H. F., Bioorg Med Chem. 2020, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 115319. [CrossRef]

- Potemkin, R., Strauch, B., Kuwert, T., Prante, O., and Maschauer, S., Mol Pharm. 2020, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 933. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y., Kimura, H., Chisaka, R., Hattori, Y., Kawashima, H., and Yasui, H., Chemical Communications. 2024, vol. 60, no. 6, p. 714. [CrossRef]

- Cordonnier, A., Boyer, D., Besse, S., Valleix, R., Mahiou, R., Quintana, M., Briat, A., Benbakkar, M., Penault-Llorca, F., Maisonial-Besset, A., Maunit, B., Tarrit, S., Vivier, M., Witkowski, T., Mazuel, L., Degoul, F., Miot-Noirault, E., and Chezal, J.-M., J Mater Chem B. 2021, vol. 9, no. 36, p. 7423. [CrossRef]

- Meher, N., Ashley, G. W., Bidkar, A. P., Dhrona, S., Fong, C., Fontaine, S. D., Beckford Vera, D. R., Wilson, D. M., Seo, Y., Santi, D. V., VanBrocklin, H. F., and Flavell, R. R., ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022, vol. 14, no. 45, p. 50569. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Luo, D., Yuan, C., Wang, X., Wang, J., Basilion, J. P., and Meade, T. J., J Am Chem Soc. 2021, vol. 143, no. 41, p. 17097. [CrossRef]

- Borré, E., Dahm, G., Guichard, G., and Bellemin-Laponnaz, S., New Journal of Chemistry. 2016, vol. 40, no. 4, p. 3164. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Dhara, S., Banerjee, S. R., Byun, Y., Pullambhatla, M., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009, vol. 390, no. 3, p. 624. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. R., Pullambhatla, M., Byun, Y., Nimmagadda, S., Green, G., Fox, J. J., Horti, A., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., J Med Chem. 2010, vol. 53, no. 14, p. 5333. [CrossRef]

- Ray Banerjee, S., Pullambhatla, M., Foss, C. A., Falk, A., Byun, Y., Nimmagadda, S., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., J Med Chem. 2013, vol. 56, no. 15, p. 6108. [CrossRef]

- Ray Banerjee, S., Chen, Z., Pullambhatla, M., Lisok, A., Chen, J., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., Bioconjug Chem. 2016, vol. 27, no. 6, p. 1447. [CrossRef]

- Wurzer, A., Seidl, C., Morgenstern, A., Bruchertseifer, F., Schwaiger, M., Wester, H., and Notni, J., Chemistry – A European Journal. 2018, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 547. [CrossRef]

- Bailly, T., Bodin, S., Goncalves, V., Denat, F., Morgat, C., Prignon, A., and Valverde, I. E., ACS Med Chem Lett. 2023, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 636. [CrossRef]

- Weineisen, M., Schottelius, M., Simecek, J., Baum, R. P., Yildiz, A., Beykan, S., Kulkarni, H. R., Lassmann, M., Klette, I., Eiber, M., Schwaiger, M., and Wester, H.-J., Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2015, vol. 56, no. 8, p. 1169. [CrossRef]

- Robu, S., Schottelius, M., Eiber, M., Maurer, T., Gschwend, J., Schwaiger, M., and Wester, H.-J., Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2017, vol. 58, no. 2, p. 235. [CrossRef]

- Uspenskaya, A. A., Machulkin, A. E., Nimenko, E. A., Shafikov, R. R., Petrov, S. A., Skvortsov, D. A., Beloglazkina, E. K., and Majouga, A. G., Mendeleev Communications. 2020, vol. 30, no. 6, p. 756. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. R., Pullambhatla, M., Byun, Y., Nimmagadda, S., Foss, C. A., Green, G., Fox, J. J., Lupold, S. E., Mease, R. C., and Pomper, M. G., Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2011, vol. 50, no. 39, p. 9167. [CrossRef]

- Tykvart, J., Schimer, J., Jančařík, A., Bařinková, J., Navrátil, V., Starková, J., Šrámková, K., Konvalinka, J., Majer, P., and Šácha, P., J Med Chem. 2015, vol. 58, no. 10, p. 4357. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S., Tönnesmann, R., Hierlmeier, I., Maus, S., Rosar, F., Ruf, J., Holland, J. P., Ezziddin, S., and Bartholomä, M. D., J Med Chem. 2021, vol. 64, no. 8, p. 4960. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D. A., Blanchette, M., Baker, M. Lou, and Guindon, C. A., Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, vol. 30, no. 21, p. 2739. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. S. A., and Mathur, A., European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports. 2022, vol. 6, p. 100084. [CrossRef]

- Eder, M., Schäfer, M., Bauder-Wüst, U., Hull, W.-E., Wängler, C., Mier, W., Haberkorn, U., and Eisenhut, M., Bioconjug Chem. 2012, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 688. no. 4). [CrossRef]

- Benešová, M., Bauder-Wüst, U., Schäfer, M., Klika, K. D., Mier, W., Haberkorn, U., Kopka, K., and Eder, M., J Med Chem. 2016, vol. 59, no. 5, p. 1761. [CrossRef]

- Liolios, C., Schäfer, M., Haberkorn, U., Eder, M., and Kopka, K., Bioconjug Chem. 2016, vol. 27, no. 3, p. 737. [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, F., Olanders, G., Rinne, S. S., Abouzayed, A., Orlova, A., and Rosenström, U., Pharmaceutics. 2022, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 1098. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchihashi, S., Nakashima, K., Tarumizu, Y., Ichikawa, H., Jinda, H., Watanabe, H., and Ono, M., J Med Chem. 2023, vol. 66, no. 12, p. 8043. [CrossRef]

- Derks, Y. H. W., Rijpkema, M., Amatdjais-Groenen, H. I. V., Kip, A., Franssen, G. M., Sedelaar, J. P. M., Somford, D. M., Simons, M., Laverman, P., Gotthardt, M., Löwik, D. W. P. M., Lütje, S., and Heskamp, S., Theranostics. 2021, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 1527. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).