Submitted:

12 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

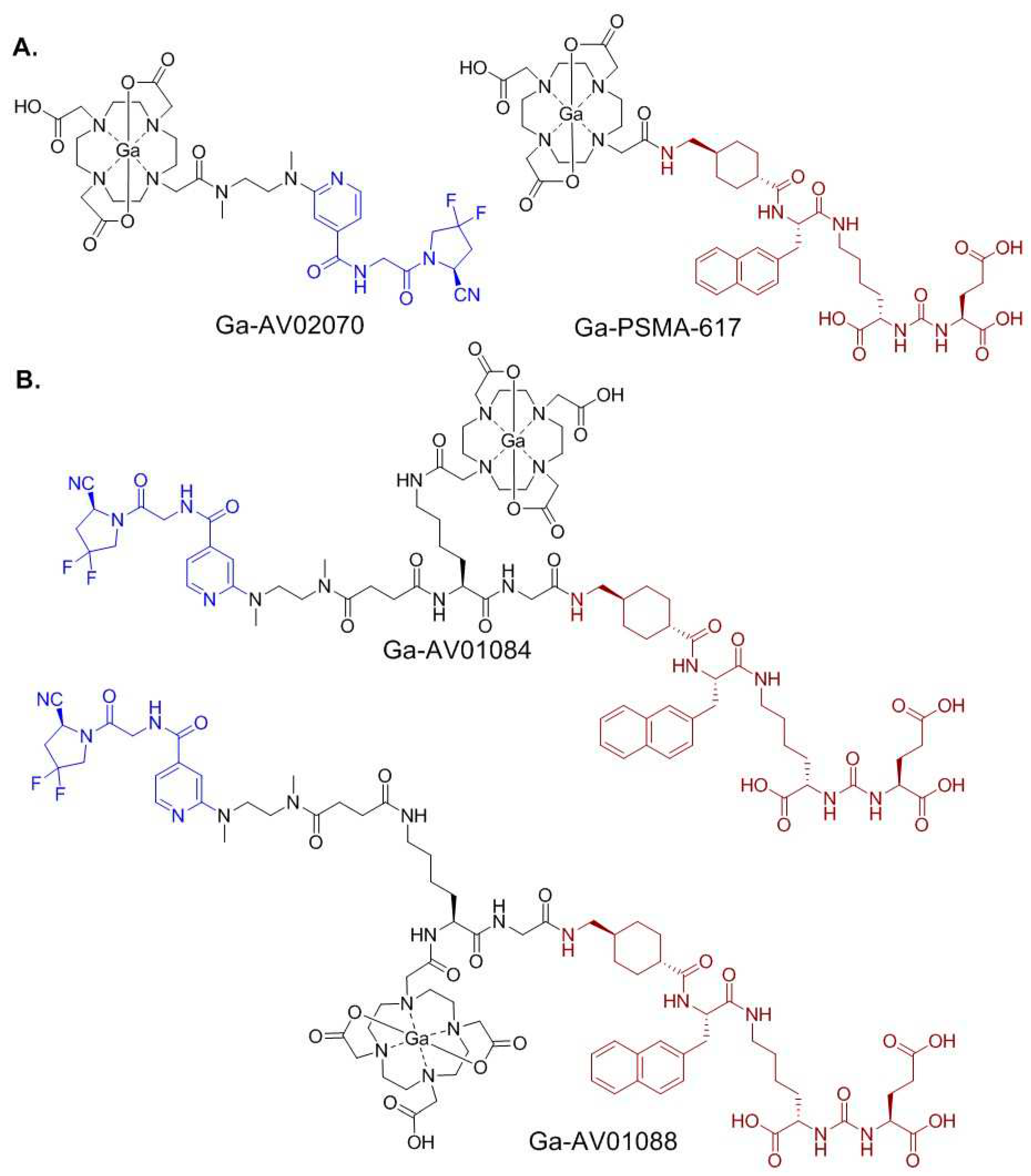

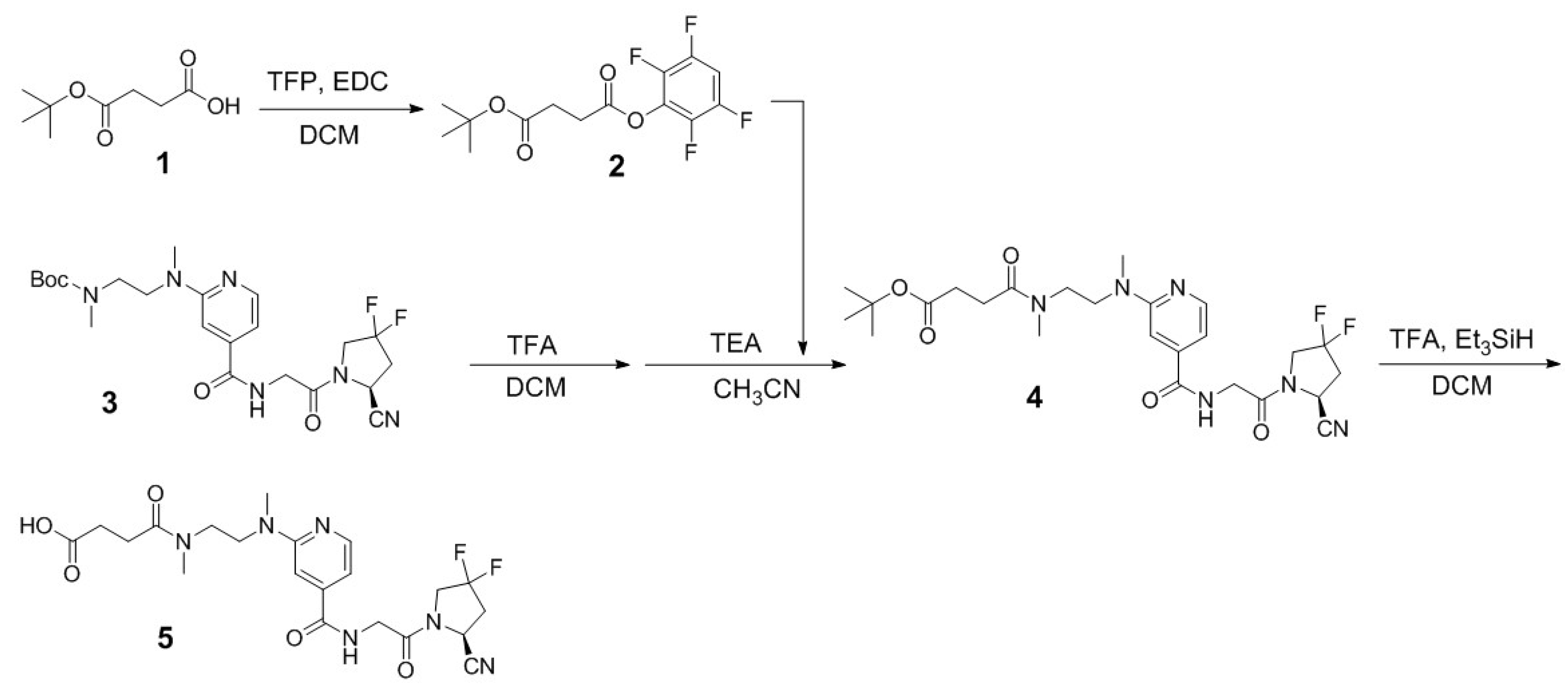

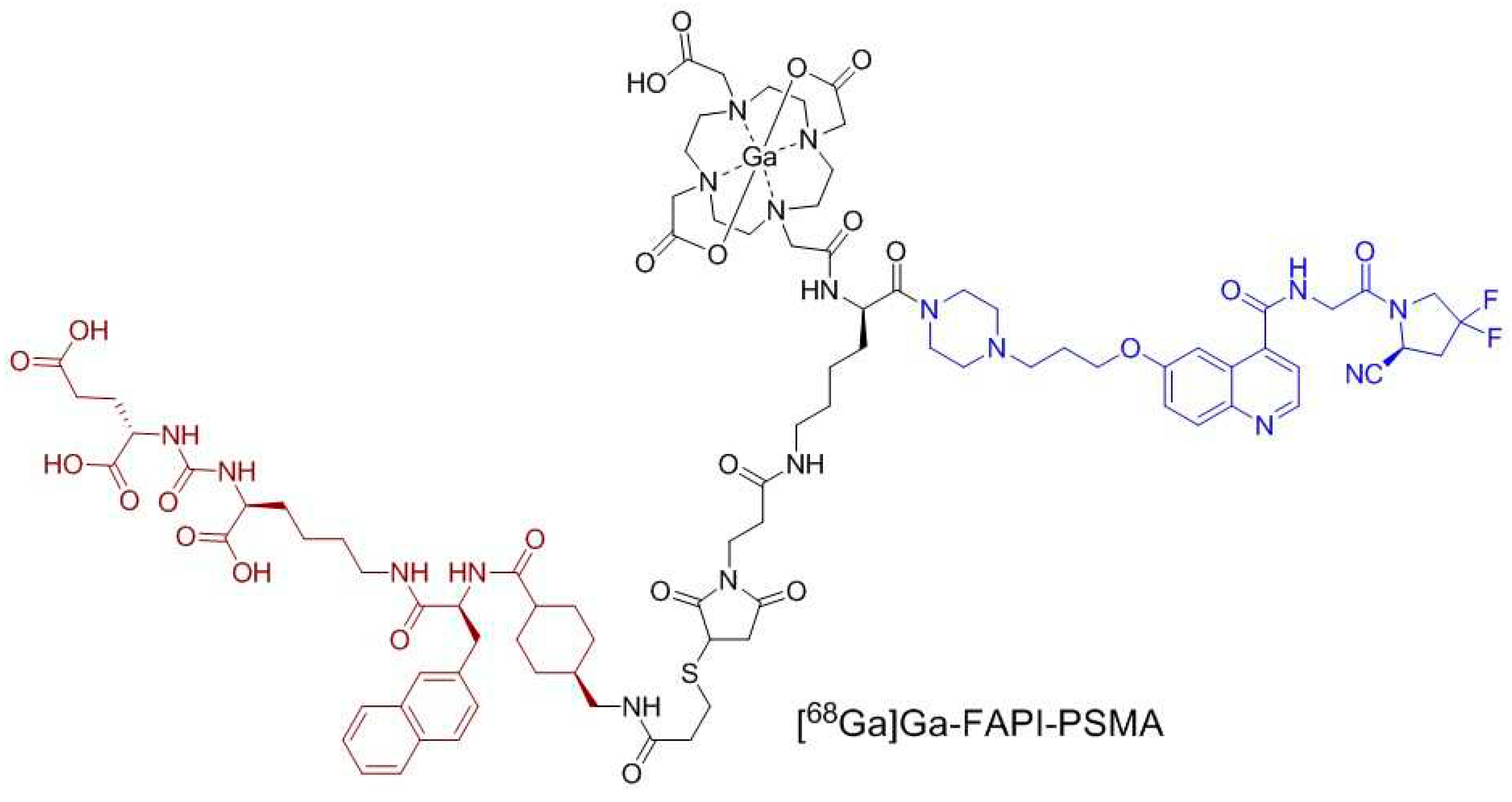

2.1. Synthesis of PSMA/FAP Bispecific Ligand

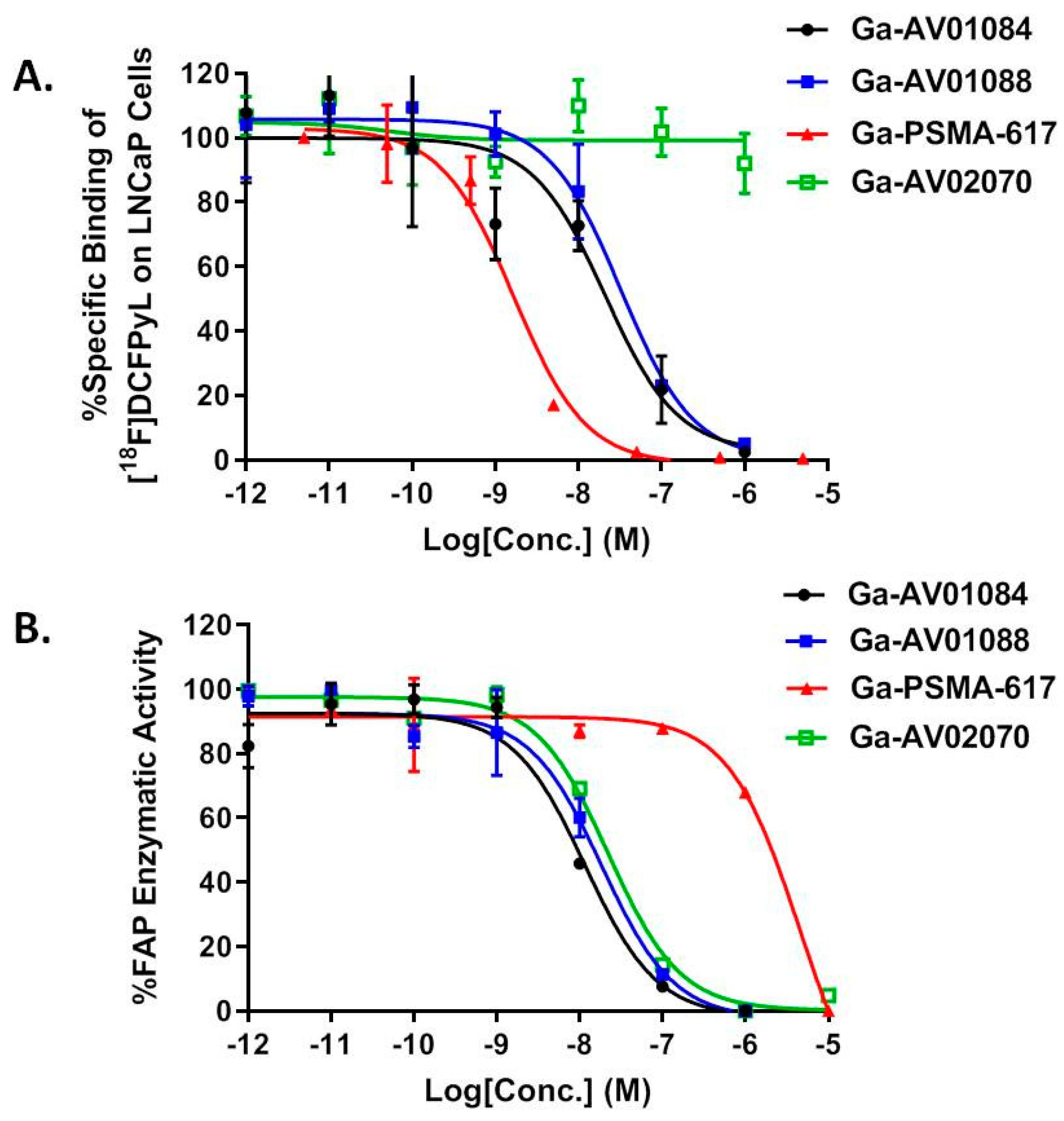

2.2. Binding Affinity and Lipophilicity

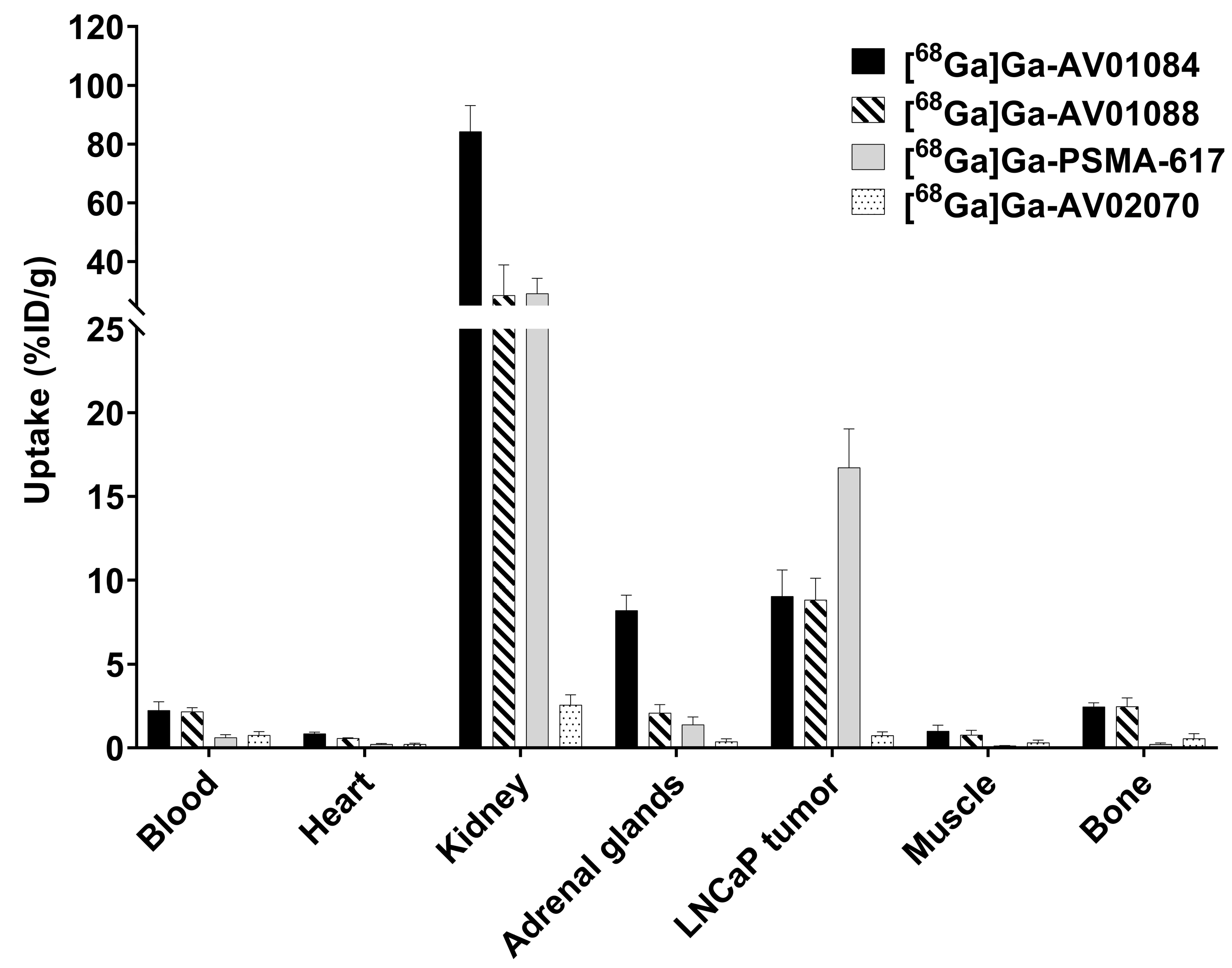

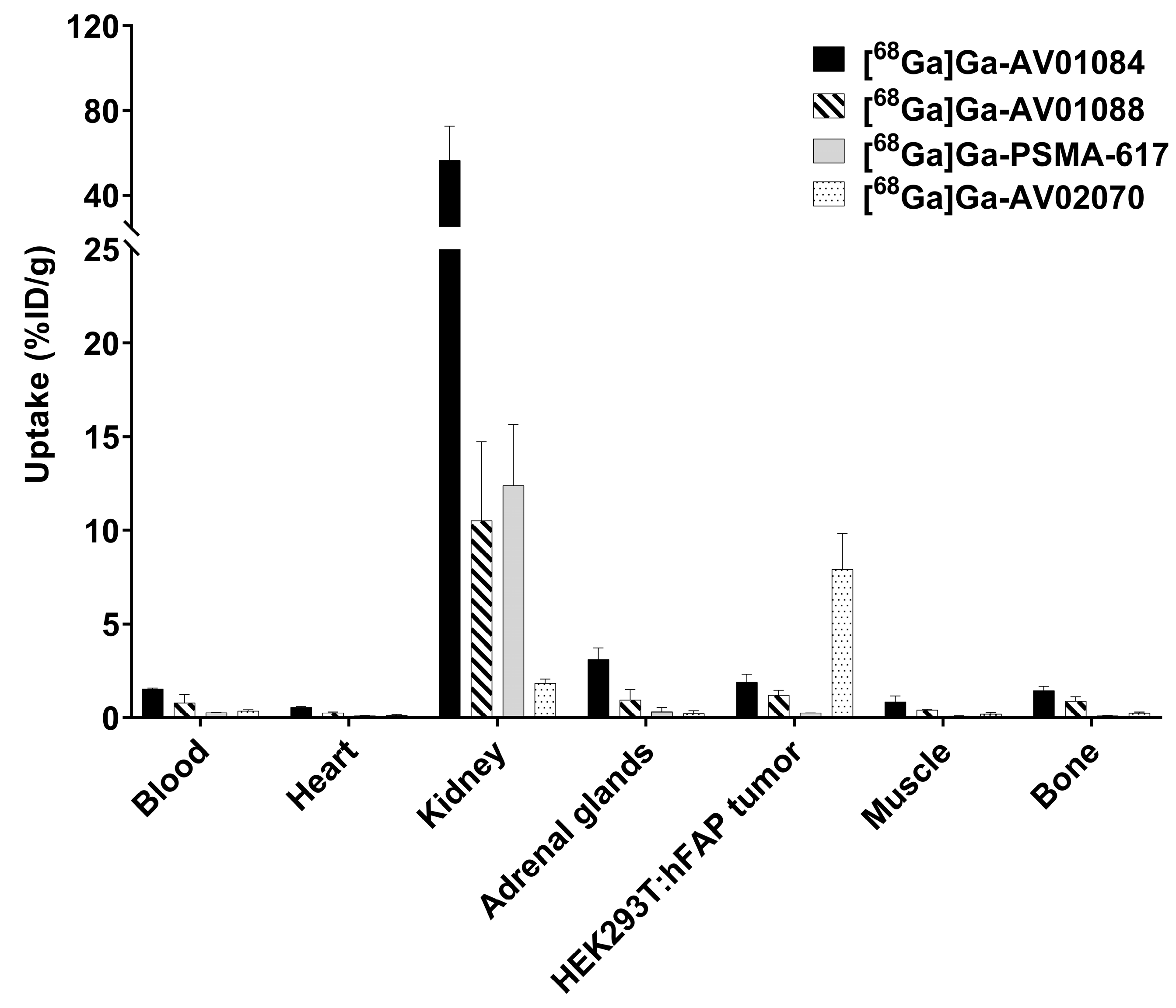

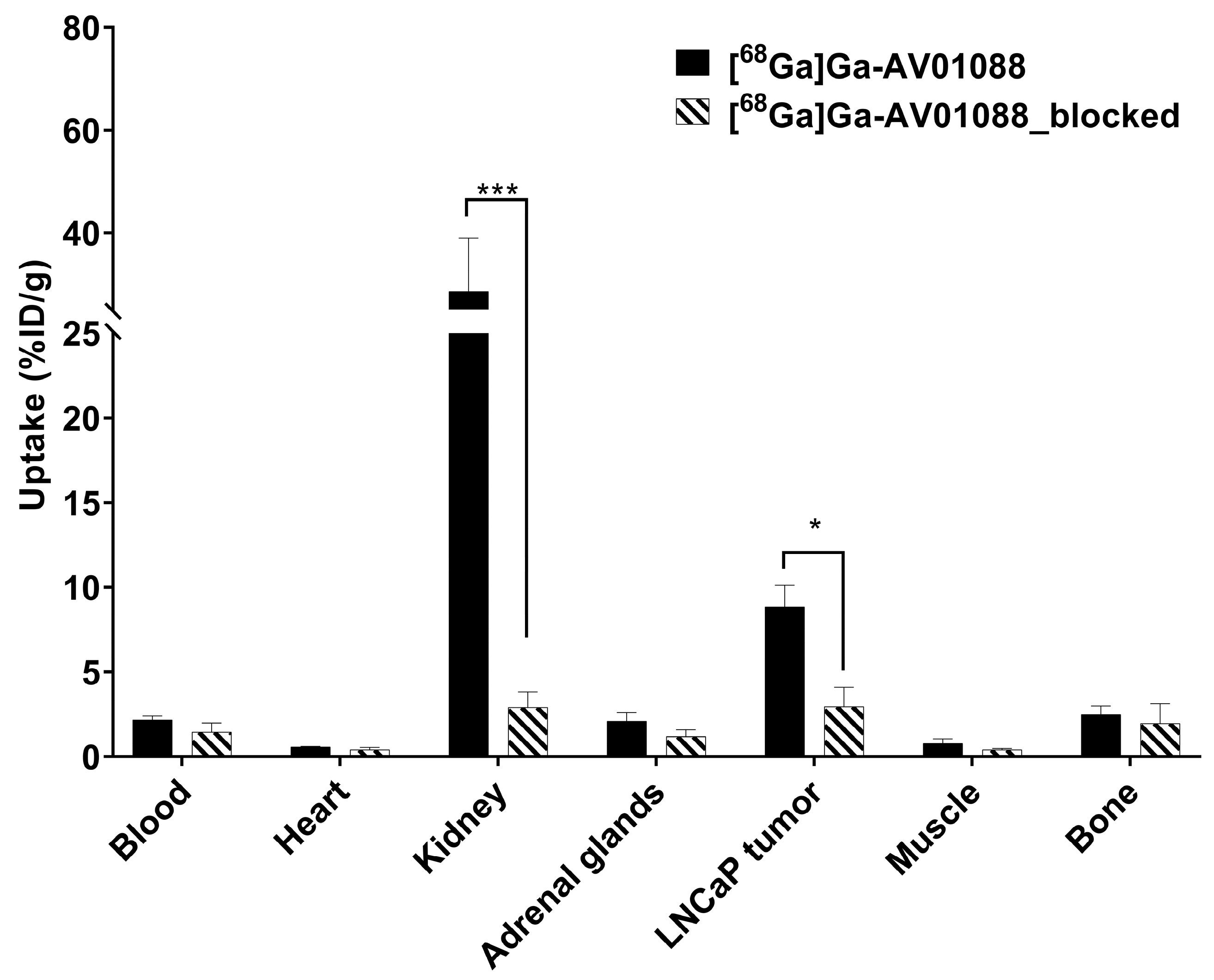

2.3. PET Imaging, ex vivo Biodistribution, and Blocking Studies

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Bispecific PSMA/FAP-targeted Ligands

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. LogD7.4 Measurement

4.4. In vitro PSMA Competition Binding Assay

4.5. In vitro FAP Fluorescence Assay

4.6. Ex vivo Biodistribution and PET/CT Imaging Studies

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R. L.; Miller, K. D.; Wagle, N. S.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, O.; de Bono, J.; Chi, K. N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S. T.; Nordquist, L. T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G.; et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassbind, S.; Ferraro, D. A.; Stelmes, J.-J.; Fankhauser, C. D.; Guckenberger, M.; Kaufmann, P. A.; Eberli, D.; Burger, I. A.; Kranzbühler, B. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET Imaging in Patients with Ongoing Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Advanced Prostate Cancer. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2021, 35, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, G.; Ippisch, R.; Slavik, R.; Mishoe, A.; Blecha, J.; Zhu, S. 68Ga-PSMA-11 NDA Approval: A Novel and Successful Academic Partnership. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, D. S.; Sachpekidis, C.; Kopka, K.; Pan, L.; Haberkorn, U.; Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss, A. Pharmacokinetic Studies of [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence of Prostate Cancer: Detection, Differences in Temporal Distribution and Kinetic Modelling by Tissue Type. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 4472 –4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaittanis, C.; Andreou, C.; Hieronymus, H.; Mao, N.; Foss, C. A.; Eiber, M.; Weirich, G.; Panchal, P.; Gopalan, A.; Zurita, J.; et al. Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Cleavage of Vitamin B9 Stimulates Oncogenic Signaling through Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 215, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, A. K.; Anilkumar, G.; Christiansen, J. J. Is Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen a Multifunctional Protein? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005, 288, C975–C981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, S.; Tolkach, Y.; Jung, K.; Stephan, C.; Busch, J.; Ralla, B.; Rabien, A.; Feldmann, G.; Brossart, P.; Bundschuh, R. A.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen Expression in the Vasculature of Renal Tumors: Implications for Imaging Studies and Prognostic Role. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernicke, A. G.; Varma, S.; Greenwood, E. A.; Christos, P. J.; Chao, K. S. C.; Liu, H.; Bander, N. H.; Shin, S. J. Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Expression in Tumor-associated Vasculature of Breast Cancers. APMIS 2014, 122, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, M. C.; Laimer, J.; Chaux, A.; Schäfer, G.; Obrist, P.; Brunner, A.; Kronberger, I. E.; Laimer, K.; Gurel, B.; Koller, J.-B.; et al. High Expression of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen in the Tumor-associated Neo-vasculature Is Associated with Worse Prognosis in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis, A.; Sheehan, B.; Riisnaes, R.; Rodrigues, D. N.; Gurel, B.; Bertan, C.; Ferreira, A.; Lambros, M. B. K.; Seed, G.; Yuan, W.; et al. Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Heterogeneity and DNA Repair Defects in Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, E. G.; Has-Simsek, D.; Sanli, O.; Sanli, Y.; Kuyumcu, S. Fibroblast Activation Protein–Targeted PET Imaging of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Compared With 68Ga-PSMA and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 47, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, R.; Seitzer, K.; Herrmann, K.; Kessel, K.; Schäfers, M.; Kleesiek, J.; Weckesser, M.; Boegemann, M.; Rahbar, K. Analysis of PSMA Expression and Outcome in Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer Receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7812–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannweiler, S.; Amersdorfer, P.; Trajanoski, S.; Terrett, J. A.; King, D.; Mehes, G. Heterogeneity of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Expression in Prostate Carcinoma with Distant Metastasis. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2009, 15, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J. E.; Lenter, M. C.; Zimmermann, R. N.; Garin-Chesa, P.; Old, L. J.; Rettig, W. J. Fibroblast Activation Protein, a Dual Specificity Serine Protease Expressed in Reactive Human Tumor Stromal Fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 36505–36512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichgräber, V.; Monasterio, C.; Chaitanya, K.; Boger, R.; Gordon, K.; Dieterle, T.; Jäger, D.; Bauer, S. Specific Inhibition of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP)-Alpha Prevents Tumor Progression in Vitro. Adv. Med. Sci. 2015, 60, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesch, C.; Yirga, L.; Dendl, K.; Handke, A.; Darr, C.; Krafft, U.; Radtke, J. P.; Tschirdewahn, S.; Szarvas, T.; Fazli, L.; et al. High Fibroblast-activation-protein Expression in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Supports the Use of FAPI-molecular Theranostics. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 49, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, T.; Zhang Paul, J.; Yingtao, B.; Celine, S.; Rajrupa, M.; Stephen, T.; Lo, A.; Haiying, C.; Carolyn, M.; June, C. H.; et al. Fibroblast Activation Protein Expression by Stromal Cells and Tumor-associated Macrophages in Human Breast Cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 2549–2557. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, L. R.; Lee, H.-O.; Lee, J. S.; Klein-Szanto, A.; Watts, P.; Ross, E. A.; Chen, W.-T.; Cheng, J. D. Clinical Implications of Fibroblast Activation Protein in Patients with Colon Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Flechsig, P.; Lindner, T.; Abderrahim, L.; Altmann, A.; Mier, W.; Adeberg, S.; Rathke, H.; Röhrich, M.; Winter, H.; et al. 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT: Tracer Uptake in 28 Different Kinds of Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegen, S.; Roth, K. S.; Weindler, J.; Claus, K.; Linde, P.; Trommer, M.; Akuamoa-Boateng, D.; van Heek, L.; Baues, C.; Schömig-Markiefka, B.; et al. First Clinical Experience With [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-46-PET/CT Versus [18F]F-FDG PET/CT for Nodal Staging in Cervical Cancer. Clin. Nucl. Med., 2023, 48, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, R. P.; Schuchardt, C.; Singh, A.; Chantadisai, M.; Robiller, F. C.; Zhang, J.; Mueller, D.; Eismant, A.; Almaguel, F.; Zboralski, D.; et al. Feasibility, Biodistribution, and Preliminary Dosimetry in Peptide-targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Diverse Adenocarcinomas Using 177Lu-FAP-2286: First-in-humans Results. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Figueroa, M. J.; Escudero-Castellanos, A.; Ramirez-Nava, G. J.; Ocampo-García, B. E.; Santos-Cuevas, C. L.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Pedraza-Lopez, M.; Avila-Rodriguez, M. A. Preparation and Preclinical Evaluation of 68Ga-iPSMA-BN as a Potential Heterodimeric Radiotracer for PET-imaging of Prostate Cancer. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 318, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boinapally, S.; Lisok, A.; Lofland, G.; Minn, I.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shin, M. J.; Merino, V. F.; Zheng, L.; Brayton, C.; et al. Hetero-bivalent Agents Targeting FAP and PSMA. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 4369–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Ye, S.; Zhong, J.; Yan, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Fu, L.; Feng, P.; Li, H. Radiosynthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of Bispecific PSMA/FAP Heterodimers for Tumor Imaging. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Liu, F.; Ren, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Z. Preclinical Evaluation of a Fibroblast Activation Protein and a Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Dual-targeted Probe for Noninvasive Prostate Cancer Imaging. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2023, 20, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verena, A.; Zhang, Z.; Kuo, H.-T.; Merkens, H.; Zeisler, J.; Wilson, R.; Bendre, S.; Wong, A. A. W. L.; Bénard, F.; Lin, K.-S. Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of Three Novel 68Ga-labeled Bispecific PSMA/FAP-targeting Tracers for Prostate Cancer Imaging. Molecules 2023, 28, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, K.; Heirbaut, L.; Verkerk, R.; Cheng, J. D.; Joossens, J.; Cos, P.; Maes, L.; Lambeir, A.-M.; De Meester, I.; Augustyns, K.; et al. Extended Structure–activity Relationship and Pharmacokinetic Investigation of (4-Quinolinoyl)glycyl-2-cyanopyrrolidine Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3053–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, S. E.; Lai, J. H.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sudmeier, J. L.; Sanford, D. G.; et al. Identification of Selective and Potent Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein and Prolyl Oligopeptidase. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3467–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verena, A.; Kuo, H.-T.; Merkens, H.; Zeisler, J.; Bendre, S.; Wong, A. A. W. L.; Bénard, F.; Lin, K.-S. Novel 68Ga-Labeled Pyridine-based Fibroblast Activation Protein-targeted Tracers with High Tumor-to-background Contrast. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benešová, M.; Schäfer, M.; Bauder-Wüst, U.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Kratochwil, C.; Mier, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Kopka, K.; Eder, M. Preclinical Evaluation of a Tailor-made DOTA-conjugated PSMA Inhibitor with Optimized Linker Moiety for Imaging and Endoradiotherapy of Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.-T.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lau, J.; Merkens, H.; Zhang, C.; Colpo, N.; Lin, K.-S.; Bénard, F. Effects of Linker Modification on Tumor-to-kidney Contrast of 68Ga-labeled PSMA-targeted Imaging Probes. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 3502–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlimthan, S.; Moon, E. S.; Rathke, H.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Rösch, F.; Rominger, A.; Gourni, E. New Frontiers in Cancer Imaging and Therapy Based on Radiolabeled Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitors: A Rational Review and Current Progress. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A. T.; Kim, H.-K. Recent Developments in PET and SPECT Radiotracers as Radiopharmaceuticals for Hypoxia Tumors. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.-T.; Lin, K.-S.; Zhang, Z.; Uribe, C. F.; Merkens, H.; Zhang, C.; Bénard, F. 177Lu-Labeled Albumin-binder-conjugated PSMA-targeting Agents with Extremely High Tumor Uptake and Enhanced Tumor-to-kidney Absorbed Dose Ratio. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanovic, I. J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Kuo, H.-T.; Colpo, N.; Zeisler, J.; Merkens, H.; Uribe, C.; Lin, K.-S.; Bénard, F. A Radiotracer for Molecular Imaging and Therapy of Gastrin-releasing Peptide Receptor-Positive Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.; Rousseau, E.; Zhang, Z.; Uribe, C. F.; Kuo, H.-T.; Zeisler, J.; Zhang, C.; Kwon, D.; Lin, K.-S.; Bénard, F. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of the Gastrin-releasing Peptide Receptor with a Novel Bombesin Analogue. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.-S.; Pan, J.; Amouroux, G.; Turashvili, G.; Mesak, F.; Hundal-Jabal, N.; Pourghiasian, M.; Lau, J.; Jenni, S.; Aparicio, S.; et al. In Vivo Radioimaging of Bradykinin Receptor B1, a Widely Overexpressed Molecule in Human Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünsch, M.; Schröder, D.; Fröhr, T.; Teichmann, L.; Hedwig, S.; Janson, N.; Belu, C.; Simon, J.; Heidemeyer, S.; Holtkamp, P.; et al. Asymmetric Synthesis of Propargylamines as Amino Acid Surrogates in Peptidomimetics. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2428–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benešová, M.; Bauder-Wüst, U.; Schäfer, M.; Klika, K. D.; Mier, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Kopka, K.; Eder, M. Linker Modification Strategies to Control the Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-targeting and Pharmacokinetic Properties of DOTA-conjugated PSMA Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).