Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Type

Population, Sample, and Inclusion Criteria

Justification and Sample Size Calculation:

Variables

Instrument

GADS

BDI

BAI

Data Collection

Handling of Missing Data

Data Confidentiality and Ethical Considerations

Data Analysis

3. Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

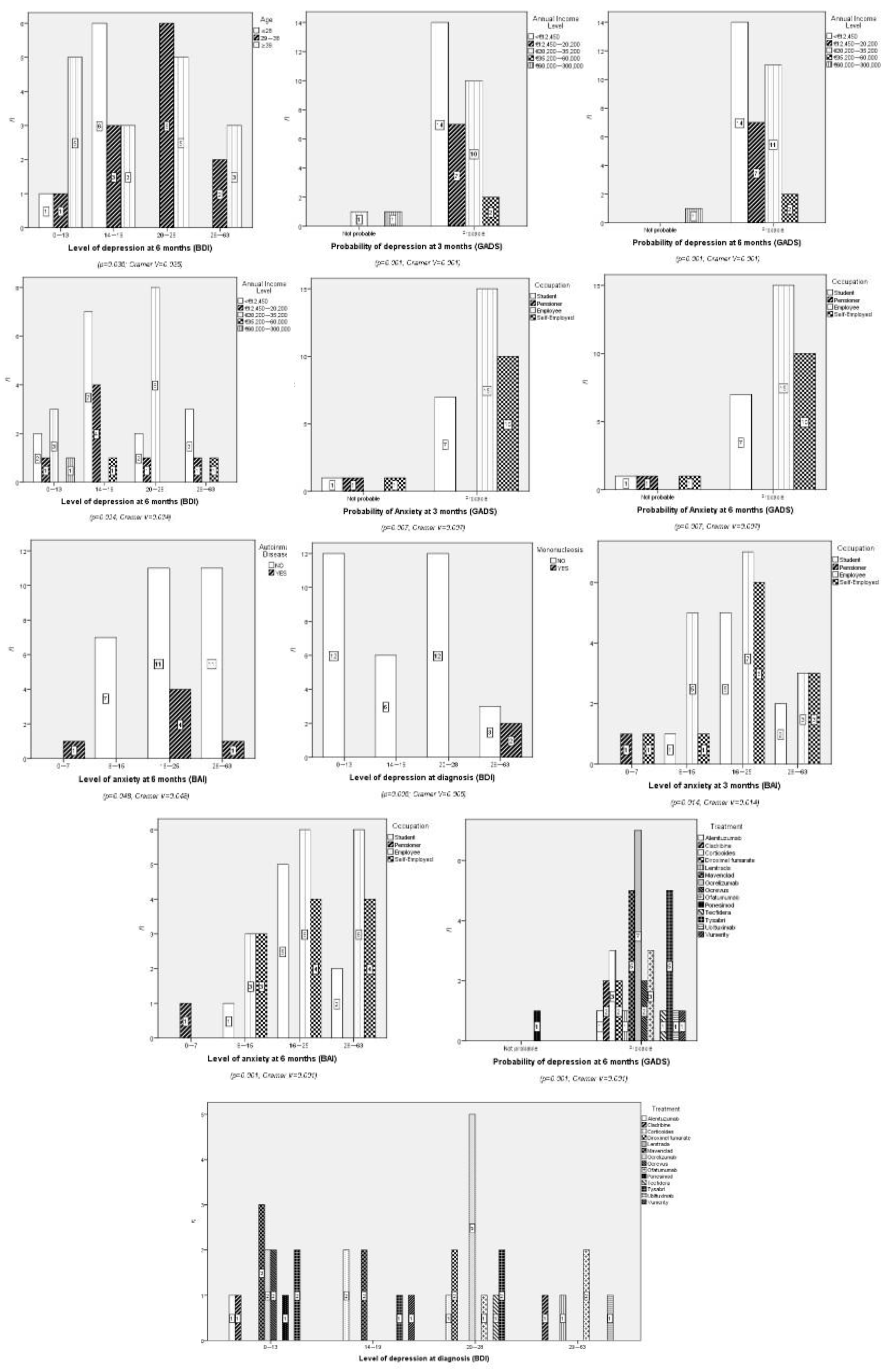

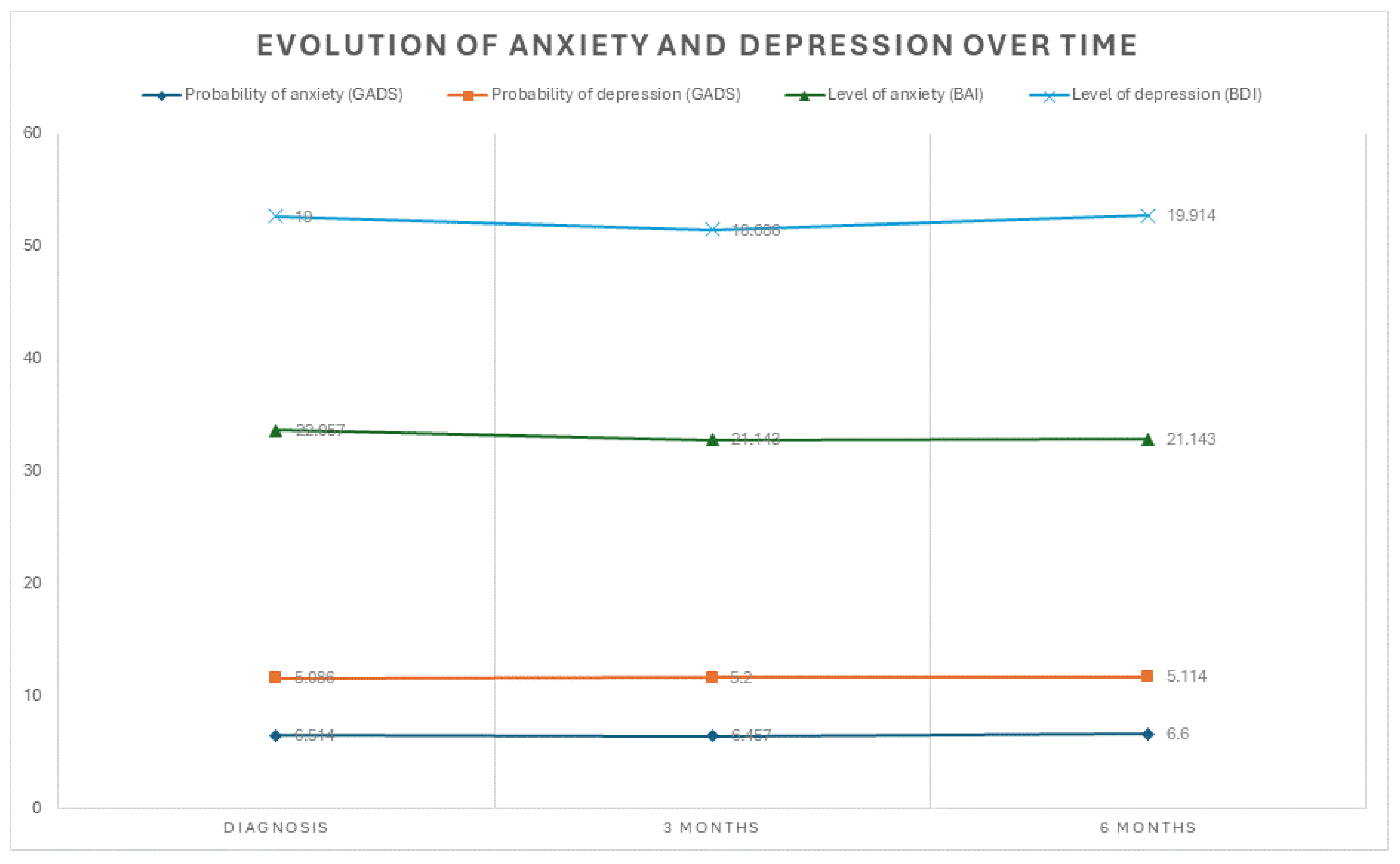

Psychological Impact

Depression

Anxiety

4. Discussion

Implications for Clinical Practice

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

References

- Margoni, M.; Preziosa, P.; Rocca, M.A.; Filippi, M. Depressive symptoms, anxiety and cognitive impairment: emerging evidence in multiple sclerosis. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyanfard, S.; Mohammadpour, M.; ParviziFard, A.A.; Sadeghi, K. Effectiveness of mindfulness-integrated cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety, depression and hope in multiple sclerosis patients: a randomized clinical trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 42, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, A.; Calabrese, P. Comparing underlying mechanisms of depression in multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2021, 20, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, D.D.; Ahmed, D.O.; Al-Bajalan, S.J. Demographic, Clinical, and Molecular Determinants of Quality of Life and Oxidative Stress in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Study from Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 75, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péloquin, S.; Schmierer, K.; Leist, T.P.; Oh, J.; Murray, S.; Lazure, P. Challenges in multiple sclerosis care: Results from an international mixed-methods study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 50, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Jolfayi, A.G.; Mousavi, S.E.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Kolahi, A.-A. Global burden of multiple sclerosis and its attributable risk factors, 1990–2019. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1448377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.E.; Lakin, L.; Binns, C.C.; Currie, K.M.; Rensel, M.R. Patient and Provider Insights into the Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liao, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Huo, S.; Qin, L.; Xiong, Y.; He, T.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, T. Mesenchymal stem cells in treating human diseases: molecular mechanisms and clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.R.P.; López, M.L.B.; Fernández, E.G.; Arnés, M.d.R.M.; Vázquez, M.F.; Hernández, M.I.N.; García, E.G. Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.M.; Bartz-Overman, C.; Parikh, T.; Thielke, S.M. Associations Between Activities of Daily Living Independence and Mental Health Status Among Medicare Managed Care Patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O.; Maskuriy, R.; Abu Bakar, N.A.; Selamat, A.; Truhlarova, Z.; Horak, J.; Joukl, M.; Vítkova, L. Challenges and opportunity in mobility among older adults – key determinant identification. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, F.; Khoshravesh, S.; Ayubi, E.; Bashirian, S.; Barati, M. Psychosocial determinants of functional independence among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heal. Promot. Perspect. 2024, 14, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Strober, L.B. Anxiety and depression in Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Antecedents, consequences, and differential impact on well-being and quality of life. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 44, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, G.; Mhizha-Murira, J.R.; Griffiths, H.; Bale, C.; Drummond, A.; Fitzsimmons, D.; Potter, K.-J.; Evangelou, N.; das Nair, R. Experiences of receiving a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Disabil. Rehabilitation 2022, 45, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.R.; das Nair, R. The psychological impact of the unpredictability of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative literature meta-synthesis. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2013, 9, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.S.; Casado, S.E.; Payero, M.Á.; Pueyo, Á.E.E.; Bernabé, Á.G.A.; Zamora, N.P.; Ruiz, P.D.; González, A.M.L. Tratamientos modificadores de la enfermedad en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple en España. Farm. Hosp. 2023, 47, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołtuniuk, A.; Pawlak, B.; Krówczyńska, D.; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J. The quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis – Association with depressive symptoms and physical disability: A prospective and observational study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1068421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, M.M.B.; Yastremiz, C.; Ciufia, N.; Roman, M.S.; Alonso, R.; Silva, B.A.; Garcea, O.; Cáceres, F.; Vanotti, S. Relevance and Impact of Social Support on Quality of Life for Persons With Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 25, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Latinsky-Ortiz, E.M.; Strober, L.B. Keeping it together: The role of social integration on health and psychological well-being among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, E4074–E4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acoba, E.F. Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1330720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Barbosa, E.A.; Guancha Aza, L.J.; Ávila Gelvez, J.A.; Gómez Alfonzo, A.E. Calidad de vida en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple. RECIAMUC. 2021, 5, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, L.G.; Izquierdo-Sanchez, L.; Hashizume, P.H.; Carlino, Y.; Baca, E.L.; Zambrano, C.; Sepúlveda, S.A.; Bolomo, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Riaño, I.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma in Latin America: a multicentre observational study alerts on ethnic disparities in tumour presentation and outcomes. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Am. 2024, 40, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Warren, J.L.; Harries, A.D.; Croda, J.; A Espinal, M.; Olarte, R.A.L.; Avedillo, P.; Lienhardt, C.; Bhatia, V.; Liu, Q.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of tuberculosis incidence and case detection among incarcerated individuals from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet Public Heal. 2023, 8, e511–e519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Brasil, T.P.; Silva, C.S.; Frota, C.C.; Sardinha, D.M.; Figueira, L.R.T.; Neves, K.A.S.; dos Santos, E.C.; Lima, K.V.B.; Ghisi, N.d.C.; et al. Comparative analysis of the leprosy detection rate regarding its clinical spectrum through PCR using the 16S rRNA gene: a scientometrics and meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1497319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.G.; García-Merino, A.; Alcalde-Cabero, E.; de Pedro-Cuesta, J. Incidencia y prevalencia de la esclerosis múltiple en España. Una revisión sistemática. Neurol. 2022, 39, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meca-Lallana, J.; Yélamos, S.M.; Eichau, S.; Llaneza, M.; Martínez, J.M.; Martínez, J.P.; Lallana, V.M.; Torres, A.A.; Torres, E.M.; Río, J.; et al. Documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Neurología sobre el tratamiento de la esclerosis múltiple y manejo holístico del paciente 2023. Neurol. 2024, 39, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waubant, E.; Lucas, R.; Mowry, E.; Graves, J.; Olsson, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Langer-Gould, A. Environmental and genetic risk factors for MS: an integrated review. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019, 6, 1905–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombash, S.E.; Lee, P.W.; Sawdai, E.; Lovett-Racke, A.E. Vitamin D as a Risk Factor for Multiple Sclerosis: Immunoregulatory or Neuroprotective? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 796933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazou, V.; Schluep, M.; Du Pasquier, R. Environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. 2015, 44, e113–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitturi, B.K.; Cellerino, M.; Boccia, D.; Leray, E.; Correale, J.; Dobson, R.; van der Mei, I.; Fujihara, K.; Inglese, M. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffary, E.M.; Panah, M.Y.; Vaheb, S.; Ghoshouni, H.; Shaygannejad, A.; Mazloomi, M.; Shaygannejad, V.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Clinical and psychological factors associated with fear of relapse in people with multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 135, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.; Mora, S. Evaluación de la calidad de vida mediante cuestionario PRIMUS en población española de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple. Neurol. 2013, 28, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, T.W.; Cha, Y.; Wolf, S.; Khan, M. Household economic instability: Constructs, measurement, and implications. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105502–105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineddine, M.; Ismail, G.; Issa, M.; El-Hajj, T.; Tfaily, H.; Dassouki, M.; Assaf, E.; Abboud, H.; Salameh, P.; Al-Hajje, A.; et al. Quality of life and access to treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis during economic crisis: the Lebanese experience. Qual. Life Res. 2025, 34, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A.; Hiltner, S. Unsettled Employment, Reshuffled Priorities? Career Prioritization among College-Educated Workers Facing Employment Instability during COVID-19. Socius: Sociol. Res. a Dyn. World 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Fung, V. Health Care Affordability Problems by Income Level and Subsidy Eligibility in Medicare. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2532862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.M. Barriers to health equity in the United States of America: can they be overcome? Int. J. Equity Heal. 2025, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, M.A.; Bieu, R.K.; Schroeder, R.W. Development of a Symptom Validity Index for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2025, 39, 1944–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, EP; Zablotsky, B. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019 and 2022. Natl Health Stat Report 2024, (213), CS353885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okutucu, F.T.; Ceyhun, H.A. The impact of anxiety and depression levels on the Big Five personality traits. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0321373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z. The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on mental health among university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1259250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montón, C.; Pérez Echevarría, M.J.; Campos, R.; García Campayo, J.; Lobo, A. Escalas de ansiedad y depresión de Goldberg: una guía de entrevista eficaz para la detección del malestar psicológico. Atención Primaria 1993, 12, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, J.; Navarro, M.E.; Vázquez, C. Adaptación española del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI) en estudiantes universitarios. Ansiedad y Estrés. 2003, 9, 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alswat, A.M.; Altirkistani, B.A.; Alserihi, A.R.; Baeshen, O.K.; Alrushid, E.S.; Alkhudair, J.; Aldbas, A.A.; Wadaan, O.M.; Alsaleh, A.; Al Malik, Y.M.; et al. The prevalence of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in patients with multiple sclerosis in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional multicentered study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1195101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, L.M.; Tingey, J.L.; Newman, A.K.; von Geldern, G.; Alschuler, K.N. A comparison of anxiety symptoms and correlates of anxiety in people with progressive and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, M.; Arıkanoğlu, A.; Aluçlu, M.U. Depression, Anxiety, and MSQOL-54 Outcomes in RRMS Patients Receiving Fingolimod or Cladribine: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbestad, A.; Willumsen, J.S.; Aarseth, J.H.; Grytten, N.; Midgard, R.; Wergeland, S.; Myhr, K.M.; Torkildsen, Ø. Increasing age of multiple sclerosis onset from 1920 to 2022: a population-based study. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghachem, I.; Kacem, A.B.H.; Romdhane, I.; Younes, S. Variation in the prevalence of multiple sclerosis according to gender and year of birth: 70 cases. J. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagici, O.; Karakas, H.; Kaya, E. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Persons with Multiple Sclerosis with Psychiatric Disorders. J. Mult. Scler. Res. 2023, 3, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, D.A.P.; Eusebio, J.R.; Amezcua, L.; Vasileiou, E.S.; Mowry, E.M.; Hemond, C.C.; (Pizzolato), R.U.; Morales, I.B.; Radu, I.; Ionete, C.; et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on mental health and health-seeking behavior across race and ethnicity in a large multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 58, 103451–103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Bhattarai, J.“.; Naismith, R.T.; Hyland, M.; Calabresi, P.A.; Mowry, E.M. Socioeconomic status and race are correlated with affective symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 41, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, I.; Sharmin, S.; Malpas, C.; Ozakbas, S.; Lechner-Scott, J.; Hodgkinson, S.; Alroughani, R.; Madueño, S.E.; Boz, C.; van der Walt, A.; et al. Effectiveness of cladribine compared to fingolimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab and alemtuzumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2024, 30, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisi, I.; Malimpensa, L.; Manzini, V.; Brandi, R.; di Sturmeck, T.G.; D’aMelio, C.; Crisafulli, S.; Ferrazzano, G.; Belvisi, D.; Malerba, F.; et al. Cladribine and ocrelizumab induce differential miRNA profiles in peripheral blood mononucleated cells from relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1234869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Roos, I.; Merlo, D.; Kalincik, T.; Ozakbas, S.; Skibina, O.; Kuhle, J.; Hodgkinson, S.; Boz, C.; et al. Comparing switch to ocrelizumab, cladribine or natalizumab after fingolimod treatment cessation in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeschoten, R.E.; Braamse, A.M.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Cuijpers, P.; van Oppen, P.; Dekker, J.; Uitdehaag, B.M. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in Multiple Sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 372, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Han, K.-D.; Jung, J.H.; Bin Cho, E.; Chung, Y.H.; Park, J.; Choi, H.L.; Jeon, H.J.; Shin, D.W.; Min, J.-H. Risk of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Mult. Scler. J. 2024, 30, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Yildiz, S.; Kılıçaslan, A.K.; Emir, B.S.; Kurt, O.; Sehlikoğlu, S. Does anxiety, depression, and sleep levels affect the quality of life in patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis? 2024, 28, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.B.; Davis, B.; Kidd, J.; Chiong-Rivero, H. Understanding Depression in People Living with Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Review of Recent Literature. Neurol. Ther. 2025, 14, 681–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Wei, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, X.; Yi, L. The prevalence and risk factors of anxiety in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, R.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, X. Fatigue and its correlation with anxiety and depression in patients with multiple sclerosis in China. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1604540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, F.; Ghajarzadeh, M.; Mohammadifar, M.; Azimi, A.; Sahraian, M.A.; Owji, M. Anxiety in patients with multiple sclerosis: association with disability, depression, disease type and sex. 2014, 52, 889–892. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, R.A.; Krug, I.; Rickerby, N.; Dang, P.L.; Forte, E.; Kiropoulos, L. Personality and cognitive factors implicated in depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 17, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Number | Symptom | Diagnosis | 3 months | 6 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frecuency | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 1 | Pessimism | 0 | 8 | 22.9 | 7 | 20 | 8 | 22.9 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 20 | 57.1 | 16 | 45.7 | ||

| 2 | 12 | 34.3 | 7 | 20 | 11 | 31.4 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | Mood | 0 | 7 | 20 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 |

| 1 | 23 | 65.7 | 23 | 65.7 | 22 | 62.9 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 11.4 | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | Failure | 0 | 24 | 68.6 | 22 | 62.9 | 23 | 65.7 |

| 1 | 7 | 20 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 11.4 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | Dissatisfaction | 0 | 10 | 28.6 | 5 | 14.3 | 4 | 11.4 |

| 1 | 15 | 429 | 23 | 65.7 | 22 | 62.9 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 22.9 | 7 | 20 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | Feelings of guilt | 0 | 21 | 60 | 20 | 57.1 | 18 | 51.4 |

| 1 | 12 | 34.3 | 12 | 34.3 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 5.7 | 3 | 8.6 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | Feelings of punishment | 0 | 25 | 71.4 | 24 | 68.6 | 24 | 68.6 |

| 1 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 7 | Self-disapproval | 0 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 28.6 | 9 | 25.7 |

| 1 | 17 | 48.6 | 23 | 65.7 | 19 | 54.3 | ||

| 2 | 5 | 14.3 | 2 | 5.7 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 8 | Self-criticism | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 15 | 42.9 | 7 | 20 |

| 1 | 17 | 48.6 | 15 | 42.9 | 20 | 57.1 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 11.4 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9 | Suicidal thoughts or ideas | 0 | 29 | 82.9 | 26 | 74.3 | 27 | 77.1 |

| 1 | 5 | 14.3 | 9 | 25.7 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 10 | Crying | 0 | 7 | 20 | 8 | 22.9 | 9 | 25.7 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 15 | 42.9 | 13 | 37.1 | ||

| 2 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 28.6 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.7 | 3 | 8.6 | ||

| 11 | Fatigability | 0 | 7 | 20 | 5 | 14.3 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 18 | 51.4 | 17 | 48.6 | ||

| 2 | 12 | 34.3 | 11 | 31.4 | 13 | 37.1 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 12 | Social withdrawal | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 8 | 22.9 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 1 | 12 | 34.3 | 23 | 65.7 | 21 | 60 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 22.9 | 4 | 11.4 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 13 | Indecisiveness | 0 | 11 | 31.4 | 10 | 28.6 | 6 | 17.1 |

| 1 | 17 | 48.6 | 18 | 51.4 | 22 | 62.9 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 7 | 20 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 14 | Changes in physical appearance | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 12 | 34.3 | 15 | 42.9 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 18 | 51.4 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 5 | 14.3 | 5 | 14.3 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 15 | Loss of energy | 0 | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 11.4 | 2 | 5.7 |

| 1 | 14 | 40 | 14 | 40 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 15 | 42.9 | 16 | 45.7 | 21 | 60 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16 | Changes in sleep patterns | 0 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 15 | 42.9 | 17 | 48.6 | ||

| 2 | 11 | 31.4 | 13 | 37.1 | 11 | 31.4 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 17 | Irritability | 0 | 10 | 28.6 | 8 | 22.9 | 6 | 17.1 |

| 1 | 15 | 42.9 | 17 | 48.6 | 20 | 57.1 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 28.6 | 10 | 28.6 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 18 | Loss of appetite | 0 | 18 | 51.4 | 22 | 62.9 | 25 | 71.4 |

| 1 | 11 | 31.4 | 6 | 17.1 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 19 | Difficulty concentrating | 0 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 1 | 16 | 45.7 | 17 | 48.6 | 16 | 45.7 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 28.6 | 10 | 28.6 | 13 | 37.1 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 20 | Fatigue or tiredness | 0 | 6 | 17.1 | 3 | 8.6 | 3 | 8.6 |

| 1 | 13 | 37.1 | 19 | 54.3 | 14 | 40 | ||

| 2 | 11 | 31.4 | 12 | 34.3 | 17 | 48.6 | ||

| 3 | 5 | 14.3 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 21 | Loss of libido | 0 | 10 | 28.6 | 11 | 31.4 | 11 | 31.4 |

| 1 | 13 | 37.1 | 15 | 42.9 | 18 | 51.4 | ||

| 0 | 11 | 31.4 | 8 | 22.9 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| Number of item | Symptom | Diagnosis | 3 months | 6 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frecuency | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 1 | Tingling or numbness | 0 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 |

| 1 | 9 | 25.7 | 10 | 28.6 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 22.9 | 11 | 31.4 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 3 | 11 | 31.4 | 7 | 20 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 2 | Feeling of heat | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 16 | 45.7 | 15 | 42.9 |

| 1 | 11 | 31.4 | 10 | 28.6 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 6 | 17.1 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 8.6 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 3 | Leg tremors | 0 | 23 | 65.7 | 19 | 54.3 | 21 | 60 |

| 1 | 5 | 14.3 | 7 | 20 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 7 | 20 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.7 | 3 | 8.6 | ||

| 4 | Inability to relax | 0 | 8 | 22.9 | 6 | 17.1 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 1 | 7 | 20 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 28.6 | 8 | 22.9 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 28.6 | 12 | 34.3 | 11 | 31.4 | ||

| 5 | Fear of the worst happening | 0 | 5 | 14.3 | 7 | 20 | 9 | 25.7 |

| 1 | 8 | 22.9 | 9 | 25.7 | 7 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 28.6 | 12 | 34.3 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 34.3 | 7 | 20 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 6 | Dizziness or lightheadedness | 0 | 22 | 62.9 | 21 | 60 | 21 | 60 |

| 1 | 9 | 25.7 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 7 | Palpitations or tachycardia | 0 | 22 | 62.9 | 18 | 51.4 | 22 | 62.9 |

| 1 | 8 | 22.9 | 15 | 42.9 | 11 | 31.4 | ||

| 2 | 5 | 14.3 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 8 | Feeling of instability or physical insecurity | 0 | 7 | 20 | 3 | 8.6 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 1 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 9 | 25.7 | 14 | 40 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 28.6 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 9 | Terrifying thoughts | 0 | 9 | 25.7 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 |

| 1 | 6 | 17.1 | 8 | 22.9 | 11 | 31.4 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 28.6 | 13 | 37.1 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 28.6 | 7 | 20 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 10 | Nervousness | 0 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 2.9 |

| 1 | 10 | 28.6 | 10 | 28.6 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 7 | 20 | 14 | 40 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 3 | 16 | 45.7 | 9 | 25.7 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 11 | Feeling of suffocation | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 19 | 54.3 | 16 | 45.7 |

| 1 | 9 | 25.7 | 7 | 20 | 12 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 6 | 17.1 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 3 | 5 | 14.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 12 | Hand tremors | 0 | 26 | 74.3 | 26 | 74.3 | 25 | 71.4 |

| 1 | 4 | 11.4 | 4 | 11.4 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 8.6 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 13 | Generalized trembling | 0 | 10 | 28.6 | 11 | 31.4 | 8 | 22.9 |

| 1 | 5 | 14.3 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 22.9 | 5 | 14.3 | 15 | 42.9 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 28.6 | 3 | 8.6 | ||

| 14 | Fear of losing control | 0 | 14 | 40 | 12 | 34.3 | 16 | 45.7 |

| 1 | 10 | 28.6 | 9 | 25.7 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 11 | 31.4 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 3 | 5 | 14.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 15 | Difficulty breathing | 0 | 24 | 68.6 | 23 | 65.7 | 24 | 68.6 |

| 1 | 4 | 11.4 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 2 | 5 | 14.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 3 | 8.6 | ||

| 16 | Fear of dying | 0 | 19 | 54.3 | 20 | 57.1 | 21 | 60 |

| 1 | 4 | 11.4 | 9 | 25.7 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 17.1 | 3 | 8.6 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 3 | 6 | 17.1 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 17 | Startling | 0 | 9 | 25.7 | 6 | 17.1 | 4 | 11.4 |

| 1 | 7 | 20 | 11 | 31.4 | 9 | 25.7 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 22.9 | 13 | 37.1 | 17 | 48.6 | ||

| 3 | 11 | 31.4 | 5 | 14.3 | 5 | 14.3 | ||

| 18 | Digestive or abdominal discomfort | 0 | 23 | 65.7 | 22 | 62.9 | 19 | 54.3 |

| 1 | 8 | 22.9 | 9 | 25.7 | 10 | 28.6 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.7 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 19 | Pallor | 0 | 33 | 94.3 | 33 | 94.3 | 34 | 97.1 |

| 1 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 2.9 | ||

| 20 | Facial flushing | 0 | 25 | 71.4 | 27 | 77.1 | 24 | 68.6 |

| 1 | 5 | 14.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 11.4 | 3 | 8.6 | 3 | 8.6 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

| 21 | Sweating (not due to heat) | 0 | 19 | 54.3 | 19 | 54.3 | 18 | 51.4 |

| 1 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 8 | 22.9 | ||

| 0 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 20 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.7 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).