1. Introduction

Neural cell regeneration offers the potential to counteract the progression, or even reverse, common neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and prion diseases; multiple sclerosis; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; tauopathies; and multiple system atrophy [

1]. These disorders have a significant social and economic impact [

2,

3]. Reports indicate that the problem is significant at the global scale, but counteracting such diseases poses a multifaceted challenge, especially in aging societies in Western countries [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, not surprisingly, nervous system repair approaches pose a significant challenge for modern medicine.

Neural tissue, the primary component of the nervous system, is found in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Unfortunately, it is characterized by poor regenerative capacity; therefore, research aimed at supporting its growth is considered. Whereas the ideal solution would be reversing the tissue disruption by supporting natural cellular self-regeneration, research is focused on cell therapies and/or biomaterials. Furthermore, the associated technologies have been developed.

As concerns cell therapies, especially neural stem cell-based therapies for central nervous system restoration, are developed, neural stem cells, which proliferate and can self-renew over the long term, unlike mature neurons, which do not proliferate, have attracted interest due to their potential for reconstructing damaged tissue through exogenous neural cell transplantation.

Concerning biomaterials capable of supporting neural regeneration engineering, it addresses nerve growth inhibition and the loss of long-distance control, allowing for the expansion of therapy beyond cell-based approaches. Materials that influence the function, growth, and differentiation of neural cells have been developed, and polyelectrolyte materials offer some promise in this regard.

Moreover, the materials nanoparticles are used for, among other reasons, their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, biomaterials that deliver growth factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, or vascular endothelial growth factor, to stimulate neurogenesis at the injured site can be mentioned [

8].

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Table 1.

Materials.

| Material |

Producer |

| (3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) |

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| Anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) antibody |

Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody |

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| Poly(ethyleneimine), branched, Mn ~60,000, Mw 750,000, analytical standard, 50% (w/v) in H2O |

Sigma-Aldrich, München, Germany |

| Copper nanopowder (CuNPs) |

3D-nano, Kraków, Poland |

| iron(II, III) oxide (Fe3O4NPs) |

3D-nano, Kraków, Poland |

| Cells: The NE-4C neuroectodermal mouse stem cell line |

ATCC |

Methods

Cell Culture

The NE-4C neuroectodermal cell line was maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) (ATCC) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ATCC), 2 mM L-Glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10−6 M all-trans retinoic acid (RA) (Sigma Aldrich) in the culture flasks pre-coated with 15 µg/mL poly-L-lysine (Sigma Aldrich). NE-4C cells from the 17th passage were used in the study. The cells were seeded onto 24-well plates coated with a nanoscale polyelectrolyte membrane at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and maintained in standard cell culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity).

Mouse neural cells of the NE-4C line were cultured for two weeks or 72 h on poly-L-lysine or polyethylenimine membrane layer coatings, with CuNPs or Fe3O4NPs at a concentration of 10 ppm, 50 ppm, and 100 ppm. The control was the culture of the above-mentioned cells on a polyelectrolyte membrane coating without nanoparticles.

To verify the function of cells and the morphology of the layer-coating-cells system, mitochondrial activity was assessed, and SEM and fluorescence microscopy were performed.

Coating Preparation

The membrane coatings were prepared based on polyethyleneimine solution at a 1 mg/mL concentration in PBS (PEI) or poly-L-lysine solution at a 1 mg/mL concentration in PBS (PLL). To obtain the coatings:

polyethyleneimine with CuNPs composite (PEI-Cu) at 100 ppm, 50 ppm, or 10 ppm: 200 ppm, 100 ppm, or 20 ppm CuNPs solution in PBS was added to PEI at a 1:1 ratio, respectively, and stirred for 4 h at room temperature.

polyethyleneimine with Fe3O4NPs composite (PEI-Fe3O4NPs) at 100 ppm, 50 ppm, or 10 ppm:a 200 ppm, 100 ppm, or 20 ppm Fe3O4NPs solution in PBS was added to PEI at a 1:1 ratio, respectively, and the mixture was stirred for 4 h at room temperature.

poly-L-lysine with CuNPs composite (PLL-Cu) at 100 ppm, 50 ppm, or 10 ppm: a 200 ppm, 100 ppm, or 20 ppm CuNPs solution in PBS was added to PLL at a 1:1 ratio, respectively, and stirred for 4 h at room temperature.

poly-L-lysine with Fe3O4NPs composite (PLL-Fe3O4NPs)—at 100 ppm, 50 ppm, or 10 ppm:a 200 ppm, 100 ppm, or 20 ppm Fe3O4NPs solution in PBS was added to PLL at a 1:1 ratio, respectively, and stirred for 4 h at room temperature.

Alamar Blue Assessment

The viability of cells immobilized on a polyelectrolyte membrane layer was assessed using the resazurin-based metabolic assay (Alamar Blue). Briefly, wells of 96-well plates were covered with polyelectrolyte membranes at the indicated densities and cultured for 72 h at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO

2 atmosphere. After this time, Alamar Blue reagent (Invitrogen) was added directly to each well at 10% (v/v) of the culture. Plates were gently mixed and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO

2 atmosphere for 24 h. Reduction of resazurin to resorufin by metabolically active cells was quantified by measuring absorbance at 540 nm and 620 nm on a microplate reader. Percent reduction of Alamar Blue was calculated using the two-wavelength formula:

where

O1 – molar extinction coefficient (E) of oxidized Alamar Blue at 540 nm;

O2 – molar extinction coefficient (E) of oxidized alamarBlue at 620 nm;

A1 – absorbance of test wells at 540 nm;

A2 – absorbance of test wells at 620 nm

P1 – absorbance of positive growth control well at 540 nm;

P2 – absorbance of positive growth control well at 620 nm.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the cells were seeded onto glass coverslips coated with a nanoscale polyelectrolyte membrane, placed in culture wells, and cultured. Cells were cultured for 3, 6, and 10 days, after which they were fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde. Following fixation, the samples were dehydrated and coated with a thin layer of gold using a sputtering system to prepare them for scanning electron microscopy analysis.

Atomic Forces Microscopy Evaluation

To examine the surface morphology of the prepared samples, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was used. A Multimode 8 Nanoscope atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to image the samples’ surfaces. Silicon cantilevers with a spring constant of ca. 5 Nm−1 (TapDLC-150, BudgetSensors, Sofia, Bulgaria) were applied for imaging in PeakForce TappingTM microscopy mode. The sample preparation procedure includes applying 10 μL of solution to a clean V1-grade mica plate (NanoAndMore GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). After 10 min, the plates were rinsed with deionized water and dried under a gentle argon stream.

Transmission Electron Microscopy Evaluation

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using a Talos F200X microscope at 200 kV. The measurements were performed in TEM modes using the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector. EDX was used to check the chemical composition. The specimens for TEM investigations were dropped onto amorphous thin carbon embedded on a Ni grid (300 Mesh Ni Pacific Grid Tech) and examined after solvent evaporation.

Immunostaining

To differentiate cell types within the scaffolds, specific dyes and antibodies were employed. Neurons were identified by immunostaining with anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), which targets neuronal cytoskeletal components. Astrocytes were detected using anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker specific to glial cells. To analyze neural cells to distinguish their components: neurons and astrocytes, cells fixed in 4% PFA were permeabilized using TRITON X-100 detergent (this allows antibodies to penetrate individual cells). Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the samples with a 5% solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following this step, the cultures were incubated for 1 h with a primary antibody targeting microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), a specific neuronal marker. After washing the specimens, they were incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to the fluorochrome Alexa Fluor 555 (red). The specimen was washed and incubated with the primary anti-GFAP antibody (an astrocyte marker) and, similarly, with the secondary conjugated antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome (green). Cell nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33342. Observations and photos were taken using an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Polyelectrolyte Layer Coatings Characterization

3.1.1. Surface Morphology and Topography Analysis

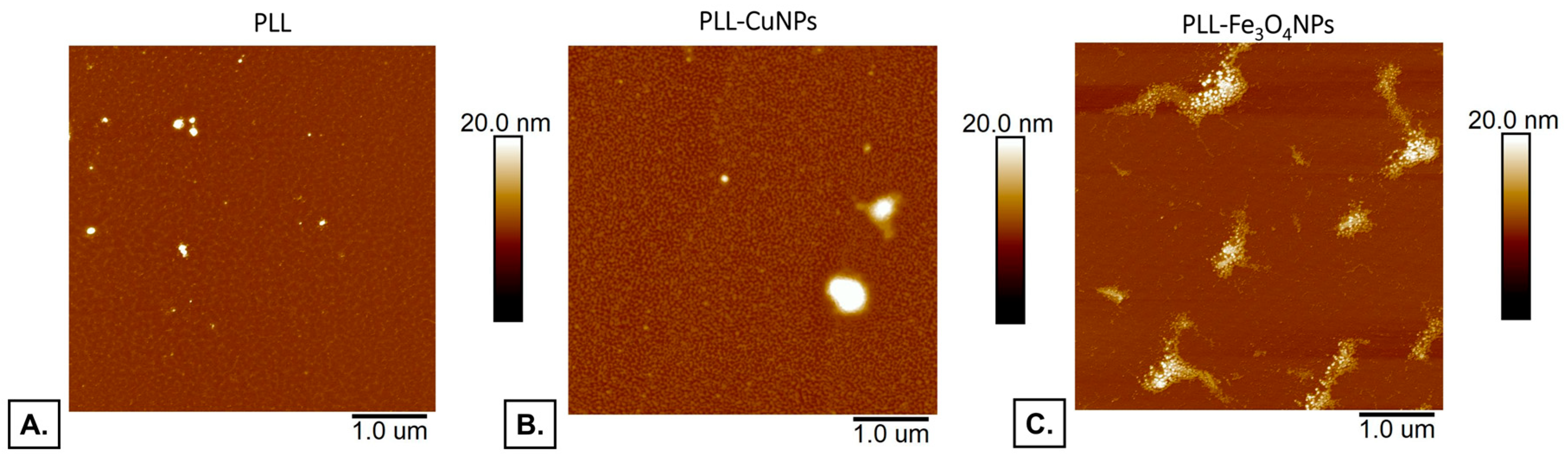

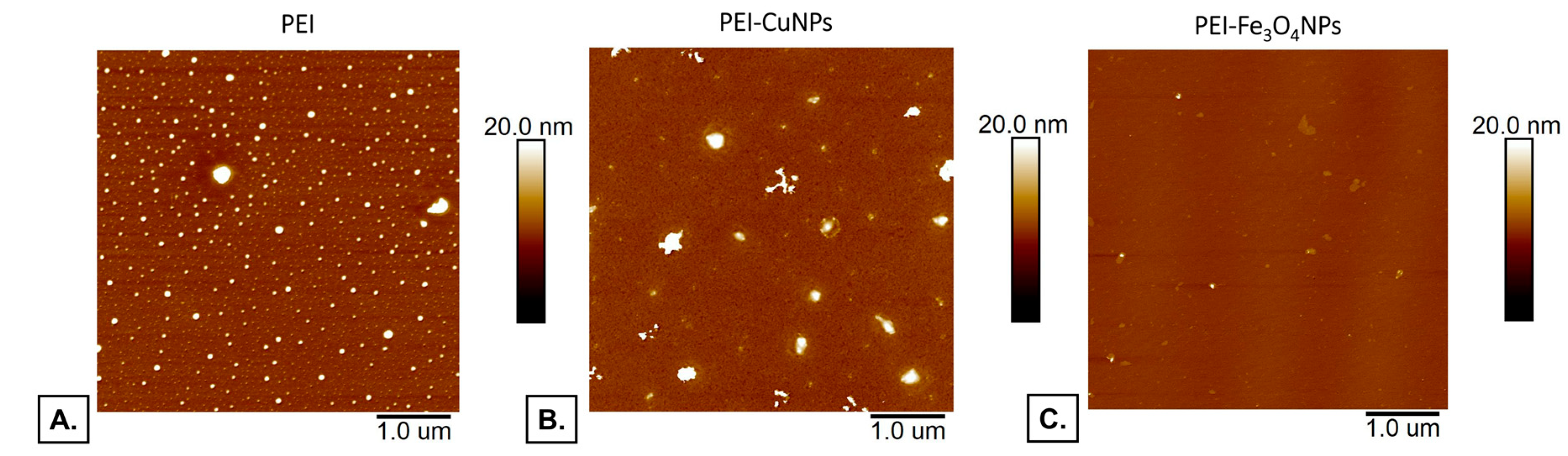

Microscopic techniques, such as atomic force microscopy, were used to assess the material’s topography and surface.

Figure 1 demonstrates the AFM images of the PLL and PLL copper nanoparticles or iron oxide nanoparticles incorporating layers placed onto the mica substrate covered by gold.

Figure 2 demonstrates the AFM images of the PEI and PEI copper nanoparticles or iron oxide nanoparticles incorporating layers placed onto the mica substrate covered by gold.

The PLL and PLL-CuNPs layers exhibit a structure with evenly distributed active centers over the entire surface.

In the case of Fe3O4NPs incorporation in the PLL sample (PLL-Fe3O4NPs), the appearance of significant centers can be observed compared with PLL alone and PLL-CuNPs, which can be caused by positively charged PLL interaction with negatively charged Fe3O4NPs.

The reflection of Fe3O4NPs involvement is not visible in the case of PLL-Fe3O4NPs material.

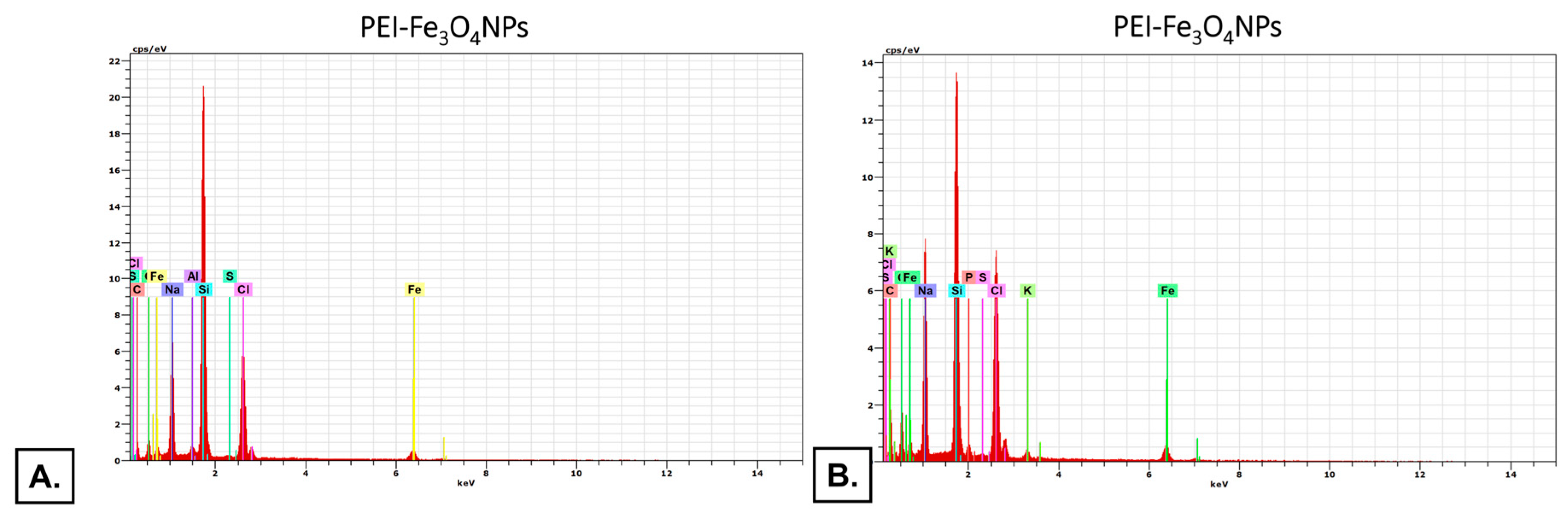

3.1.2. Chemical Composition Analysis

The high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) in STEM (scanning transmission electron microscope) mode was applied. The energy-dispersive X-ray mapping (EDX) instrument, coupled with a microscope, was applied to assess the chemical composition of membranes.

Samples’ mapping spectra showed the membrane incorporating elements. For PLL and PEI membranes incorporating Fe

3O

4NPs, the mean Fe share values were as follows: 5.61±1.90 and 7.25±0.90, respectively (

Figure 3). presents the representative images of the spectrum.

As a result of PLL and PEI incorporating CuNPs, only a slight signal corresponding to Cu (0.14 and 0.07, respectively) was observed in the EDX spectra.

3.2. Polyelectrolytes for Interface with Neural Cells

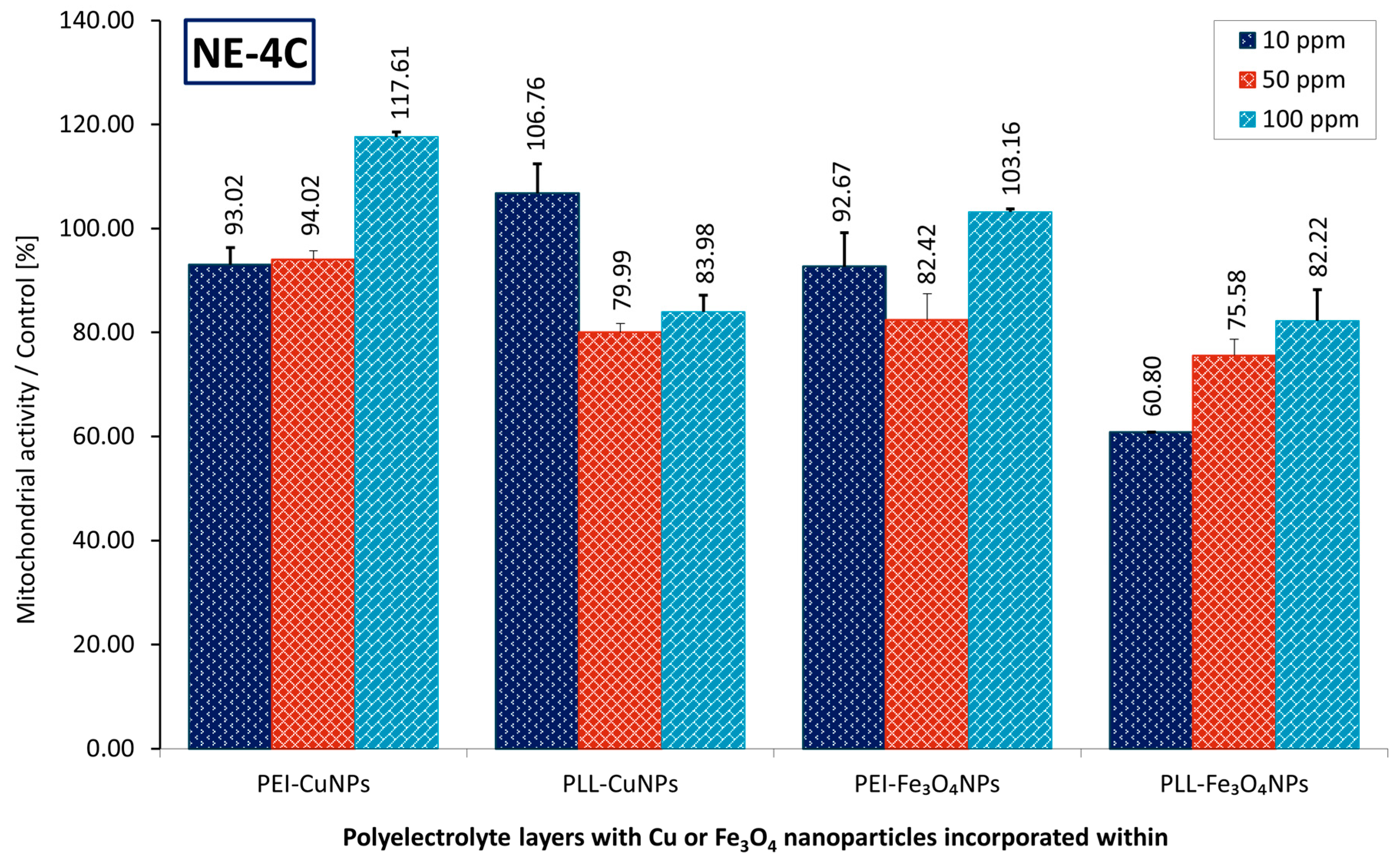

Polyethylenimine and poly-L-lysine incorporating CuNPs or Fe3O4NPs have been shown to interact with the mouse neural stem cell line NE-4C. The effect of different concentrations of CuNPs and Fe3O4NPs incorporated within the membrane shells was verified.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial activity of NE-4C cells immobilized on the coating layer NPs was assessed over a 72-h culture period, with results expressed as a ratio relative to the control. Key to the symbols: PEI-CuNPs – polyethylenimine CuNPs incorporating, PEI-Fe3O4NPs – polyethylenimine Fe3O4NPs incorporating, PLL-CuNPs – poly-L-lysine CuNPs incorporating, PLL- Fe3O4NPs - poly-L-lysine Fe3O4NPs incorporating. 10 ppm, 50 ppm, 100 ppm – share of NPs incorporating. The values are presented as mean ± SD.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial activity of NE-4C cells immobilized on the coating layer NPs was assessed over a 72-h culture period, with results expressed as a ratio relative to the control. Key to the symbols: PEI-CuNPs – polyethylenimine CuNPs incorporating, PEI-Fe3O4NPs – polyethylenimine Fe3O4NPs incorporating, PLL-CuNPs – poly-L-lysine CuNPs incorporating, PLL- Fe3O4NPs - poly-L-lysine Fe3O4NPs incorporating. 10 ppm, 50 ppm, 100 ppm – share of NPs incorporating. The values are presented as mean ± SD.

In the case of PEI-CuNPs material, after 72-h culture, no significant difference was observed between PEI-CuNPs 10 ppm and PEI-CuNPs 50 ppm membranes. There was a substantial variation compared with PEI-CuNPs at 100 ppm; the discrepancies in cell viability cultured within membranes with CuNPs at 10 ppm and 50 ppm exceeded 24% on average.

In the case of the PLL-CuNPs material, after 72-h culture, no marked difference was seen between PEI-CuNPs 50 ppm and PEI-CuNPs 100 ppm membranes. However, analysis revealed a meaningful difference compared with PEI-CuNPs at 10 ppm; the variability in cell viability cultured within membranes with CuNPs at 50 ppm and 100 ppm exceeded 25% on average.

For the PEI-Fe3O4NPs material, after 72 h of culture, no substantial difference emerged between the PEI-Fe3O4NPs 10 ppm and 50 ppm membranes, but the results indicated a significant disparity compared with PEI-Fe3O4NPs at 100 ppm; the divergence in cell viability cultured within membranes with CuNPs at 10 ppm and 50 ppm exceeded 16% on average.

In the case of the PLL-Fe3O4NPs material, after 72 h of culture, no notable difference was observed between PLL-Fe3O4NPs 50 ppm and PEI-Fe3O4NPs 100 ppm membranes. There was a significant difference compared with PEI-Fe3O4NPs 10 ppm; the variations in cell viability cultured within membranes with Fe3O4NPs 50 ppm and 100 ppm exceeded 18% on average.

Regarding differences in mitochondrial activity of cells cultured on materials at the interface with varying shares of applied nanoparticles, in the case of PEI-Fe3O4NPs 10 ppm and PEI-Fe3O4NPs 50 ppm, no substantial difference in mitochondrial activity was observed between cells on materials with NPs and those without NPs. There was a marked disparity compared with PEI-Fe3O4NPs at 100 ppm. Similarly, in the case of PEI-CuNPs 10 ppm and PEI-CuNPs 50 ppm, results indicated no clear distinction in mitochondrial activity between cells on materials with NPs and on the material without NPs. There was a marked difference compared with PEI-CuNPs 100 ppm.

It was observed that, for the PEI-based material, a larger share of NPs is beneficial for cell mitochondrial activity in both the CuNPs and Fe3O4NPs cases. Moreover, it can be noted that for the PLL-based material containing Fe3O4NPs, the effect of a higher proportion of NPs is beneficial for the mitochondrial activity of cells as well. However, in the case of PLL-based material containing CuNPs, the lower share of NPs corresponds to the increased mitochondrial activity of cells. Generally, a higher share of Fe3O4NPs increases mitochondrial activity in neural cells in both PLL- and PEI-based materials.

3.3. Visualization of Layer Coating Scaffold-Neuronal Cells Systems

Microscopic observation of neural cell morphology in a system with an immobilizing material can be a simple way to provide insight into their interactions with the immobilizing substrate.

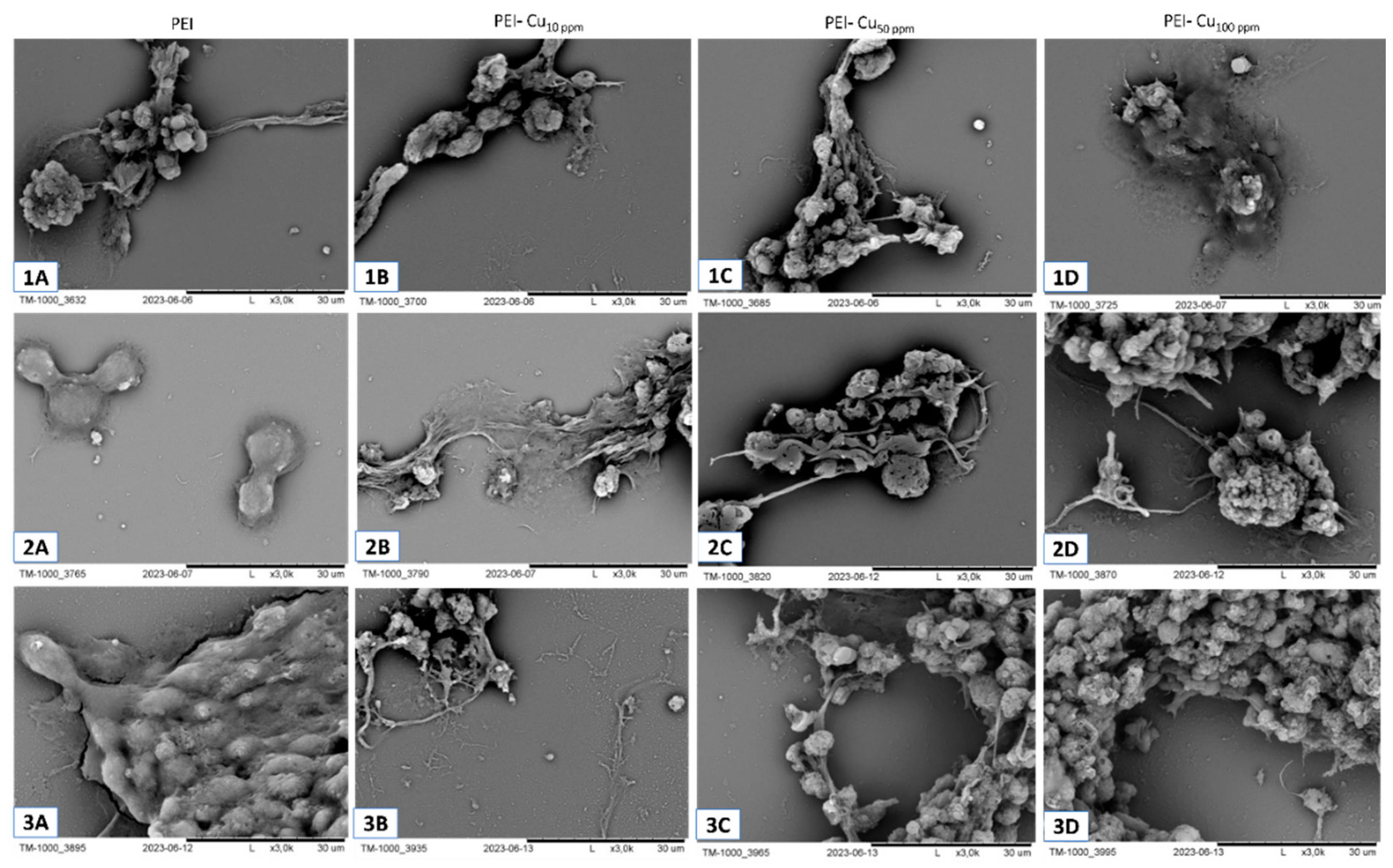

Scanning electron microscopy is a valuable technique for examining the morphological features of layer membrane coating scaffold-cells systems, particularly polyelectrolyte (PE) membrane–immobilized cells.

Below, we present an exemplary SEM analysis of a PEI-based coating layer incorporating copper nanoparticles at different concentrations (10-, 50-, and 100 ppm), after 72-h culture (

Figure 5).

No noticeable alterations in cell morphology may be observed using SEM during 72 h of culture in the presence of nanocomposites containing varying CuNPs content.

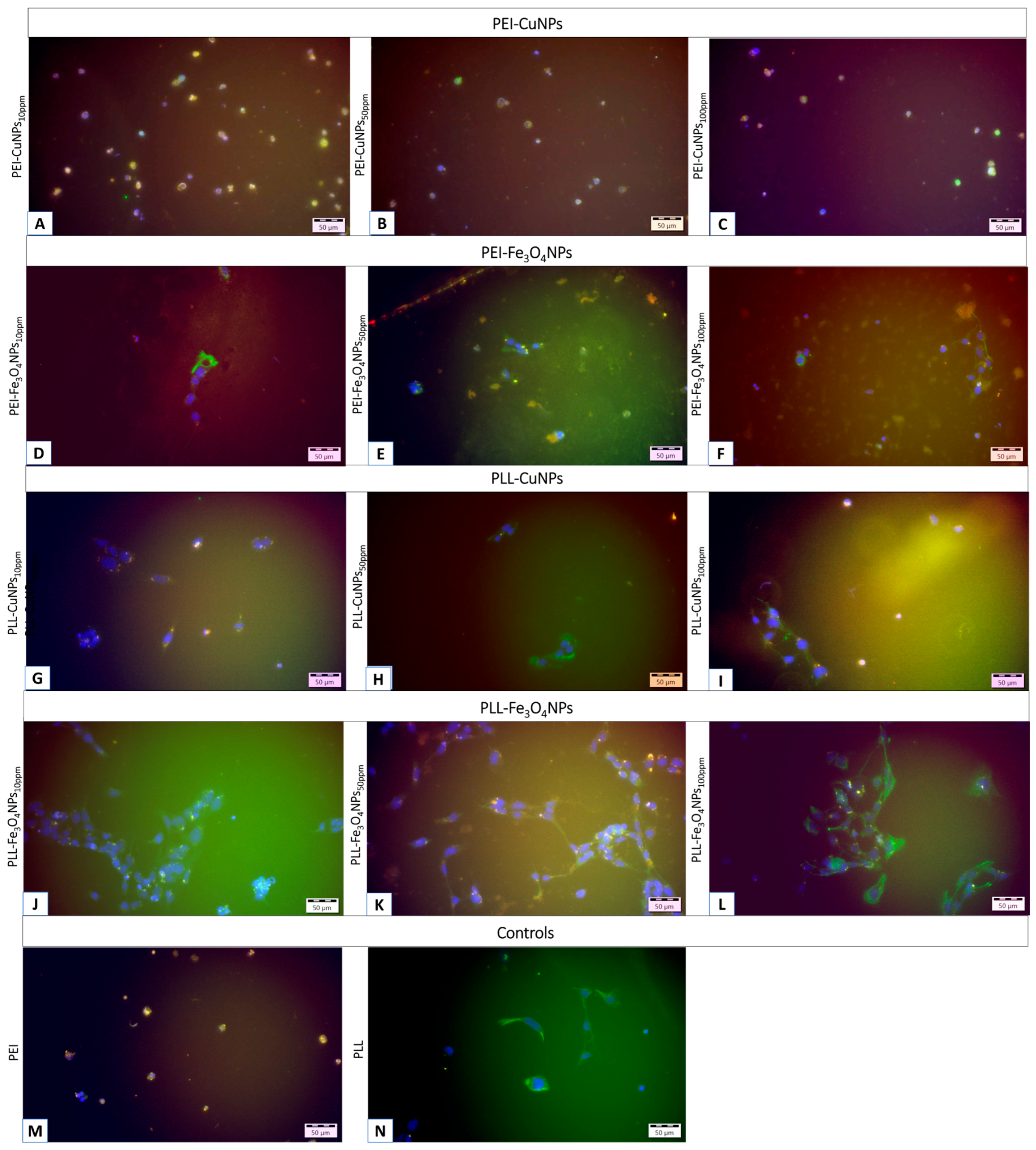

Thus, for further assessment, the effort to distinguish neurons and astrocytes was undertaken.

The application of selective dyes that distinguish between neurons and astrocytes enables visualization of the functional architecture of neural cells within the scaffolds. For example, cells can be simultaneously labeled with anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), a marker for the neural skeleton, and anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an indicator of astrocytes. Furthermore, fluorescent labeling can be accomplished by conjugating fluorochromes such as Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 555, facilitating the identification and delineation of specific cellular components under fluorescence microscopy.

The efficacy assessment of scaffolds based on poly-L-lysine or polyethylenimine incorporating copper or iron oxide nanoparticles is presented below.

Figure 6 shows the neural cells immobilized within the nanocomposite scaffolding shell after 72 h of culture (5% CO

2, 37◦C). An examination of the system by immunostaining revealed neural cell populations. The light green fluorescence indicates cells expressing glial fibrillary protein, while the orange/red fluorescence reveals neurons.

However, microscopic observations confirmed the presence of both astrocytes and neurons on all selected scaffolds; the neurons showed morphological features that differed from the typical characteristics of this cell type. Cells with a bundle shape predominate, with a few showing a tendency to form a spindle shape. The culture of the material containing Fe3O4NPs indicates a more significant share of neurons in the cell population than the material containing CuNPs.

It should be noted that the use of selected metallic nanoparticles affects both the morphology and function of neural cells, in addition to the anticipated antibacterial effects and the possibility of mediating electrical stimulation of neural cells.

4. Discussion

It is worth noting that some metal-based NPs may serve as electrostimulating agents for theranostic applications. For example, copper nanoparticles (CuNPs), which show high conductivity (Cu, σ = 5.96 × 10

7 S m

−1) [

8]. The electrical conductivity of Fe

3O

4 is 2.99×10

−3 S cm

−1 [

9]. Incorporation of Fe

3O

4 and Cu nanoparticles was chosen due to the electrostimulating properties of these nanoparticles. At the same time, the goal was to obtain a material containing electrostimulating elements that would support neuronal growth. From the perspective of mitochondrial activity, the material with a higher share of Fe

3O

4NPs showed increased mitochondrial activity in neural cells compared with lower shares of those nanoparticles, in both PLL- and PEI-based materials.

In the case of PLL-based material containing CuNPs, the lower share of NPs corresponds to the increased mitochondrial activity of cells.

Analyzing the effect of selected nanoparticles incorporated at the same proportion/concentration in different PLL or PEI base materials, it can be observed that for both Fe3O4NPs and CuNPs in the PLL base material, the mitochondrial activity of cells immobilized in it is significantly lower in 72-h culture, except for the CuNPs at 10 ppm. A more beneficial effect on neural cell activity was observed for the PLL-based material with the lowest proportion of incorporated CuNPs. Similarly, in Lipko et al., increasing the CuNPs content to 100 ppm decreased A549 mitochondrial activity for the PLL- and PEI-based materials.

The effects mentioned above may result from cellular material striving to adopt a spindle-shaped structure, enabled by the selected material configuration. In the case of Fe3O4NPs: 100 ppm share in PLL and PEI, while in the case of CuNPs: 100 ppm share in PEI and 10 ppm share in PLL.

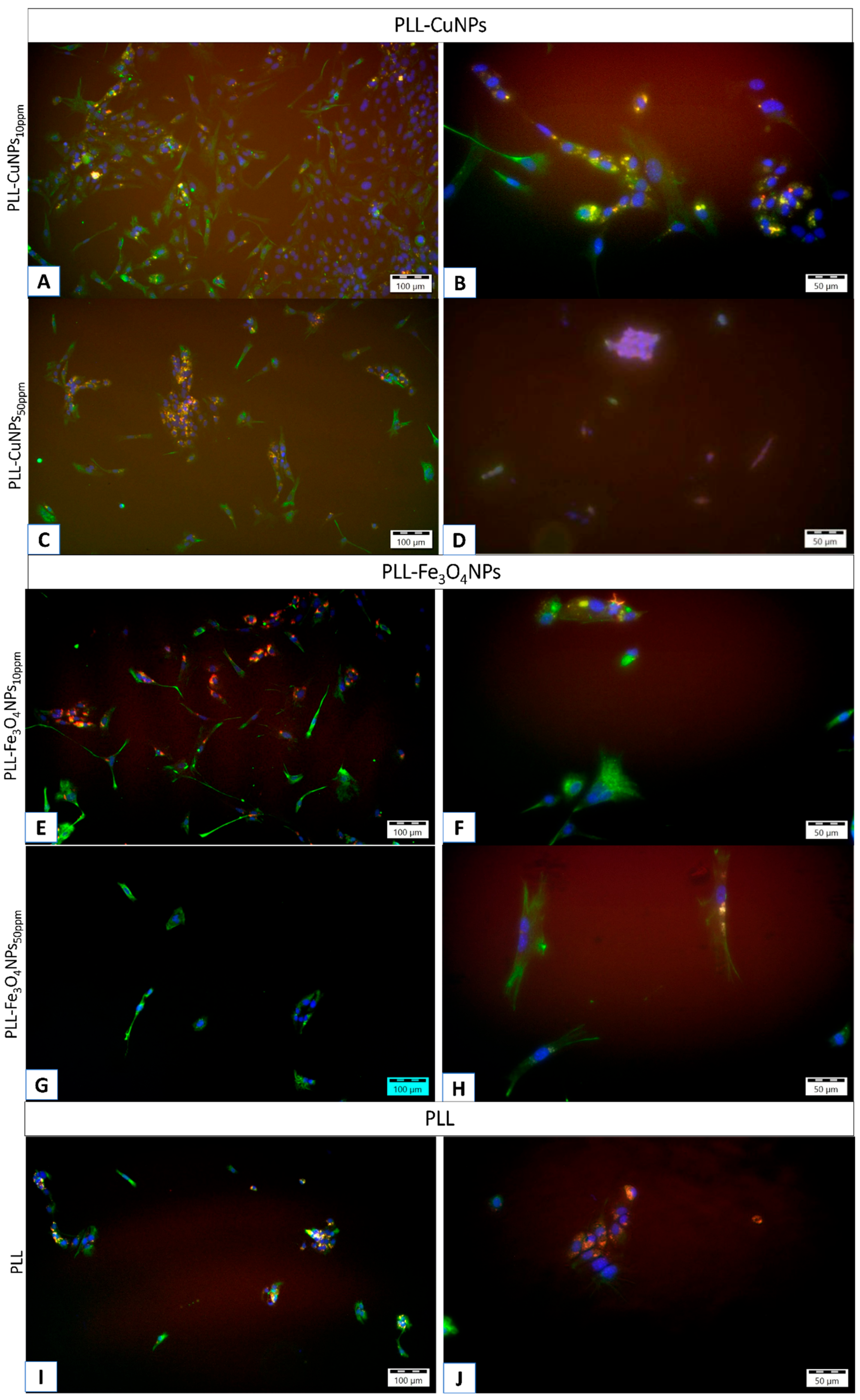

It should be noted that the fluorescence image indicates a tendency for a higher proportion of neurons in the configuration containing the Fe3O4NPs material compared to the CuNPs incorporating material.

This tendency persists even after a more extended culture period, as shown in the example picture of a 2-week culture (

Figure 7).

It can be explained by findings that negatively charged NPs, when administered at low concentrations, interact with the neuronal membrane and the synaptic cleft, whereas positively and neutrally charged NPs do not localize to neurons. The presence of negatively charged NPs on neuronal cell membranes alters neuronal excitability, increasing the amplitude and frequency of spontaneous postsynaptic currents at the single-cell level. Negatively charged NPs bind exclusively to excitable neuronal cells and never to non-excitable glial cells [

10].

Fe

3O

4NPs have been studied in various configurations to assess their effects on nerve growth. For example, Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles coated with omega-3 at a dose of 30 mg/kg showed an impact on sciatic nerve regeneration in Wistar rats” [

11].

Some authors observed that mesoporous hollow Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles at a concentration of 40 μg mL-1 can, among other things, promote the proliferation of neural stem cells, an effect that can be enhanced upon application of an alternating magnetic field [

12].

Our research indicates that the PEI-based material with incorporated 100 ppm Fe3O4 NPs can be recommended for further studies on its suitability for supporting neuronal growth. However, further studies are necessary, including genetic assessment, e.g., of Map2 mRNA expression levels.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, nanoparticle incorporation can modulate the interfacial material-cell environment, which influences neural cells. The PEI-based material with a higher share of Fe3O4NPs (100 ppm) can be recommended for further studies on its suitability for supporting neuronal growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and L.H.G.; Methodology, A.G.; Validation, L.H.G.; Formal analysis, L.H.G. and A.K.; Investigation, A.G., A.L. and M.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.K., L.H.G. and A.G.; Writing—review and editing, L.H.G.; Visualization, A.K.; A.G.; Supervision, L.H.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFM |

Atomic Forces Microscopy |

| PBS |

Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| CuNPs |

Copper nanoparticles |

| EDX |

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| EMEM |

Eagle’s minimum essential medium |

| |

|

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| Fe3O4NPs |

Iron(II, III) oxide nanoparticles |

| GFAP |

Anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| HRTEM |

High-resolution transmission electron microscope |

| MAP2 |

Anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| MTT |

(3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PEI |

Poly(ethyleneimine) |

| PLL |

Poly-L-lysine |

| RA |

Retinoic acid |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| STEM |

Scanning transmission electron microscope |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

References

- Ashraf, S.S.; Hosseinpour Sarmadi, V.; Larijani, G.; Naderi Garahgheshlagh, S.; Ramezani, S.; Moghadamifar, S.; Mohebi, S.L.; Brouki Milan, P.; Haramshahi, S.M.A.; Ahmadirad, N.; et al. Regenerative medicine improve neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Tissue Bank. 2023, 24, 639–650. [CrossRef]

- The Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegenerative Diseases | ScienceDirect Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128113042/the-molecular-and-cellular-basis-of-neurodegenerative-diseases?via=ihub= (accessed on May 31, 2025).

- Ciurea, A.V.; Mohan, A.G.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Costin, H.P.; Glavan, L.A.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Saceleanu, V.M. Unraveling Molecular and Genetic Insights into Neurodegenerative Diseases: Advances in Understanding Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s Diseases and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10809. [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.I.; Borchelt, D.R. Phenotypic diversity in ALS and the role of poly-conformational protein misfolding. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V. V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Mechanisms of Degeneration and Therapeutic Approaches with Their Clinical Relevance. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99. [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Van Schependom, J.; D’haeseleer, M. Advances in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2023, Vol. 12, Page 1709 2023, 12, 1709. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.N.; Zamboni, F.; Serafin, A.; Escobar, A.; Stepanian, R.; Culebras, M.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Emerging scaffold- and cellular-based strategies for brain tissue regeneration and imaging. Vitr. Model. 2022 12 2022, 1, 129–150. [CrossRef]

- Sirivat, A.; Paradee, N. Facile synthesis of gelatin-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticle: Effect of pH in single-step co-precipitation for cancer drug loading. Mater. Des. 2019, 181. [CrossRef]

- Dante, S.; Petrelli, A.; Petrini, E.M.; Marotta, R.; Maccione, A.; Alabastri, A.; Quarta, A.; De Donato, F.; Ravasenga, T.; Sathya, A.; et al. Selective Targeting of Neurons with Inorganic Nanoparticles: Revealing the Crucial Role of Nanoparticle Surface Charge. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 6630–6640. [CrossRef]

- Tamjid, M.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Mahmoudi, F.; Mirzaee, S.; Tamjid, M.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Mahmoudi, F.; Mirzaee, S.; Tamjid, M.; Abdolmaleki, A.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Coated with Omega-3 as a Novel Drug for Recovery of Sciatic Nerve Injury in Rats. Gene, Cell Tissue 2023 102 2023, 10, e127688. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wu, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Dai, H. Mesoporous hollow Fe3O4 nanoparticles regulate the behavior of neuro-associated cells through induction of macrophage polarization in an alternating magnetic field. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 5633–5643. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).