1. Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) occurring in adults younger than 45 years represents an increasingly recognized and complex cardiovascular entity with profound clinical, epidemiological, and societal implications [

1]. Traditionally perceived as a disease of middle-aged and elderly individuals, AMI is now emerging in younger cohorts at a pace that mirrors shifts in global health determinants. The rising incidence of premature AMI reflects an intricate interplay between biological predispositions, behavioral factors, and environmental influences, together with rapid changes in metabolic health and psychosocial stress exposure. This trend is particularly alarming because it affects individuals in their most productive decades, amplifying the long-term consequences of morbidity, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, and healthcare expenditure [

2,

3,

4].

From an epidemiological standpoint, early-onset AMI exhibits distinctive characteristics compared with its late-onset counterpart. While classical risk factors remain highly prevalent, younger adults frequently display a different risk profile, characterized by a predominance of smoking, dyslipidemia with pronounced atherogenic profiles, early vascular aging, obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. In addition, non-traditional and emerging risk determinants - including chronic low-grade inflammation, psychosocial distress, sleep disorders, recreational drug use (particularly cocaine and cannabis), and genetic variants affecting lipoprotein metabolism or thrombosis - play a proportionally greater role in precipitating premature coronary events [

5,

6].

These elements collectively contribute to a more heterogeneous pathogenic pathway, ranging from plaque rupture and erosion to coronary vasospasm and microvascular dysfunction, adding further complexity to diagnosis and long-term risk stratification. Although modern reperfusion strategies, improved emergency networks, and adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy have significantly reduced early mortality across age groups, young survivors of AMI face a unique trajectory of long-term vulnerability. Even in the presence of angiographically mild or single-vessel disease, they are at risk of recurrent ischemic episodes, arrhythmic events, adverse ventricular remodeling, and impaired cardiopulmonary fitness. Moreover, persistence of unhealthy behaviors, socioeconomic instability, and psychological distress - including post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrent cardiac events - substantially influence prognosis and quality of life. The intersection between biological recovery and psychosocial adaptation is particularly relevant in this population, given their high expectations for rapid functional reintegration and return to work [

7,

8]. The complexity of this recovery trajectory has highlighted the limitations of traditional follow-up approaches, which rely on episodic, clinic-based assessments that only capture static snapshots of the patient’s physiological status. Advances in digital health technologies have therefore opened a transformative frontier in secondary prevention and long-term cardiovascular monitoring. Wearable devices - equipped with accelerometers, photoplethysmography (PPG), biosensors, and wireless connectivity - enable continuous, real-time acquisition of physiological, behavioral, and environmental data. These technologies support a transition from reactive, physician-driven care to proactive, patient-centered, data-rich models of disease management [

9,

10,

11].

In particular, the integration of wearable systems in the post-AMI setting offers unprecedented opportunities to quantify recovery dynamics with high temporal resolution. Continuous monitoring of heart rate and variability, motor activity, energy expenditure, oxygen saturation, sleep architecture, and circadian rhythms allows for granular assessment of autonomic function, physical conditioning, endothelial health, and behavioral adherence. Patterns of daily activity - such as step count variability, sedentary burden, and intensity of exertion - reflect important correlates of cardiovascular performance and are increasingly recognized as independent predictors of morbidity, mortality, and rehospitalization. Additionally, wearable-derived metrics allow early recognition of maladaptive recovery patterns, such as persistently elevated resting heart rate, reduced physical activity, or dysregulated sleep, which may signal ventricular dysfunction, poor fitness recovery, or psychological distress The potential added value of these technologies becomes even more relevant when combined with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Instruments such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) provide validated insight into subjective dimensions of recovery, including functional capacity, mood, emotional burden, fatigue, and perceived quality of life. The combination of continuous biosignal monitoring with PROMs creates a multidimensional framework capable of capturing both objective and experiential aspects of post-AMI health, aligning with emerging principles of precision cardiology and holistic cardiovascular rehabilitation. Nevertheless, despite their extensive availability and rapid adoption in the consumer market, the integration of wearable devices into routine cardiovascular care remains hindered by several knowledge gaps. Concerns persist regarding data accuracy, inter-device variability, sensor drift, and the validity of surrogate parameters for clinical decision-making. Furthermore, challenges related to interoperability, data governance, long-term adherence, digital literacy, and patient privacy raise important questions about feasibility and scalability. These issues are especially relevant in young AMI patients, who represent a heterogeneous and highly dynamic subgroup with diverse expectations, lifestyles, and technology use behaviors. Against this background, the present research provides a comprehensive, multidimensional evaluation of wearable device–enabled monitoring in young adults recovering from AMI. This thesis integrates: 1. objective biosignal analytics focused on motor activity and autonomic markers; 2. validated PROMs capturing psychological, behavioral, and functional recovery; 3. usability and acceptability analyses exploring the patient experience with digital monitoring; 4. methodological evaluation of data quality, adherence, and feasibility within real-world clinical pathways. Through this approach, the study seeks to elucidate the clinical relevance, predictive value, and translational potential of continuous remote monitoring in the early post-AMI phase.

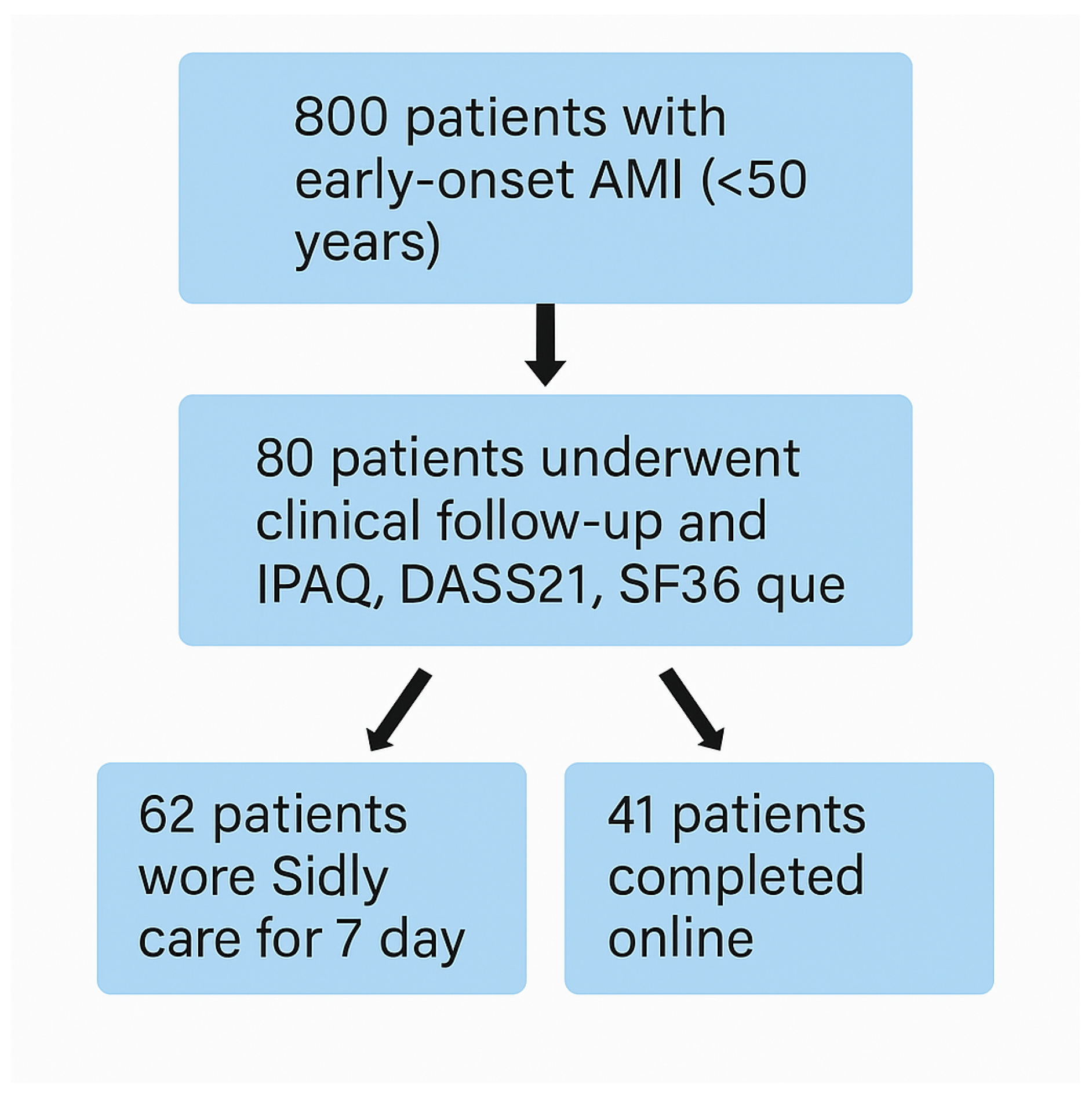

Figure 1 summarizes the study design, outlining the recruitment process, group allocation, and multimodal data acquisition pipeline that forms the methodological backbone of the subsequent chapters. By integrating clinical cardiology, digital health science, behavioral medicine, and data analytics, this work aims to contribute to a more personalized, anticipatory, and technologically enabled model of cardiovascular care for young AMI survivors.

1.1. Risk Factors

Recent evidence confirms that the predominant pathophysiological drivers of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in young adults remain coronary atherosclerotic plaque rupture and erosion, which collectively account for approximately 90 percent of cases in this population [

12]. Plaque rupture is typically associated with large lipid cores, thin fibrous caps, and heightened inflammatory activity, whereas plaque erosion, more frequently observed in younger patients - especially women - is characterized by endothelial denudation, superficial proteoglycan accumulation, and reduced inflammatory infiltrate. The remaining 10 percent of AMI presentations arise from non-atherosclerotic mechanisms, including spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), coronary vasospasm, microvascular dysfunction, hypercoagulable states, coronary embolism, myocarditis, and autoimmune-mediated vascular inflammation. These alternative etiologies underscore the heterogeneity of AMI pathogenesis in young adults and highlight the need for tailored diagnostic and therapeutic pathways. Both modifiable and non-modifiable factors intricately modulate susceptibility to these pathogenic processes. Non-modifiable risk factors comprise age, sex, ethnicity, menopausal status, and family history of cardiovascular disease. Young males remain disproportionately affected, a pattern attributed to sex hormone–mediated differences in endothelial function, plaque composition, and thrombogenicity. Genetic predisposition plays a central role: monogenic conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia, homocystinuria, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and fibromuscular dysplasia significantly elevate risk through mechanisms involving dyslipidemia, hypercoagulability, or structural arterial fragility [

13] Beyond monogenic disorders, genome-wide association studies have revealed a continuum of risk determined by the cumulative burden of common genetic variants. Polygenic risk scores (PRS), derived from hundreds to thousands of loci associated with lipid metabolism, inflammation, and vascular biology, have emerged as strong predictors of early-onset AMI, often outperforming traditional risk calculators in young individuals with otherwise unremarkable clinical profiles [

14].

Recent attention has also shifted toward non-traditional risk contributors, which exert profound vascular effects through chronic inflammatory activation, immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. Conditions such as HIV infection, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, chronic kidney disease, and obstructive sleep apnea significantly accelerate atherogenesis, promote plaque vulnerability, and impair coronary microvascular function [

15]. Inflammatory cytokines—including IL-6, TNF, and interferons—drive endothelial activation, promote leukocyte adhesion, and mediate prothrombotic states, while intermittent nocturnal hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea induces sympathetic overactivity, oxidative stress, and cardiometabolic dysregulation. These emerging determinants expand the conventional understanding of cardiovascular risk in younger populations, emphasizing the need for integrated assessment models that incorporate immune, metabolic, and neurohormonal factors. Modifiable risk factors remain highly prevalent among young AMI patients and represent critical intervention targets. Tobacco use stands as the most dominant risk factor, often present in up to 70–90 percent of young AMI cohorts. Smoking induces endothelial dysfunction, increases platelet reactivity, accelerates atherosclerotic plaque formation, and potentiates coronary vasospasm. Excessive alcohol consumption exerts dose-dependent cardiovascular effects, contributing to hypertension, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and pro-inflammatory lipid profiles. Metabolic disorders—including obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and overt diabetes—are increasingly common among younger adults, driven by lifestyle changes, nutritional habits, and rising prevalence of sedentary behavior. Diabetes and metabolic syndrome exhibit particularly aggressive coronary phenotypes in young individuals, characterized by diffuse non-calcified plaque, enhanced inflammatory activity, impaired vascular reactivity, and early endothelial senescence. Sedentary behavior, now recognized as an independent cardiovascular risk factor, further contributes to AMI susceptibility by promoting visceral adiposity, dysglycemia, systemic inflammation, and autonomic imbalance. Physical inactivity not only predisposes individuals to a first ischemic event but also markedly amplifies the risk of recurrent events and long-term mortality among AMI survivors [

16].

Modifiable risk factors—tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity—further shape AMI incidence and progression. Sedentary behavior is particularly detrimental, not only predisposing to first events but also amplifying cardiovascular risk in post-AMI survivors [

17]. Conversely, robust evidence supports the protective effect of regular physical activity through improvements in endothelial function, nitric oxide bioavailability, lipid metabolism, autonomic regulation, and plaque stability [

18]. Exercise also exerts beneficial effects on psychosocial health, reducing depressive symptoms, stress, and sleep disturbances—factors that themselves modulate cardiovascular risk. Nevertheless, despite growing recognition of its prognostic relevance, long-term outcome data specifically examining the impact of structured physical activity interventions in young AMI survivors remain limited, highlighting a critical need for targeted research within this demographic. Collectively, these risk factors illustrate the multifactorial and often overlapping pathways contributing to premature AMI. Their complex interactions underscore the importance of comprehensive, individualized risk assessment strategies that integrate genetic, metabolic, behavioral, inflammatory, and psychosocial dimensions. Understanding this intricate risk architecture is fundamental not only for elucidating disease mechanisms but also for optimizing prevention, early detection, and long-term management in young adults with AMI.

1.2. Wearable Devices

The contemporary landscape of cardiovascular medicine increasingly relies on wearable medical devices equipped with sophisticated multisensor architectures capable of capturing continuous, high-resolution physiological and behavioral data. These systems represent a crucial technological interface between patients and healthcare providers, enabling remote surveillance, early risk detection, and longitudinal monitoring in both clinical and real-world environments. Modern wearables integrate different sensing modalities, including photoplethysmography (PPG), single- and multi-lead electrocardiography (ECG), bioimpedance analysis, accelerometry, gyroscopy, and reflectance oximetry, thereby supporting the acquisition of parameters such as heart rate, cardiac rhythm, heart rate variability (HRV), oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate, blood pressure (through pulse wave analysis), sleep stages, and step-based physical activity patterns [

19]. These sensor modalities exploit advanced signal processing pipelines. PPG signals, for example, extract cardiac pulsatility via green- or infrared-based optical wavelengths, while embedded computational filters mitigate motion artefacts through adaptive noise cancellation and frequency-domain correction. ECG modules capture depolarization morphology, allowing detection of arrhythmias, premature ventricular complexes, and ischemia-related alterations when configured for multi-lead acquisition. Accelerometers and gyroscopes provide multidimensional kinematic data that enable quantification of gait dynamics, sedentary time, energy expenditure, circadian rhythmicity, and physiologic tremor patterns. Increasingly, wearable devices incorporate environmental sensors (temperature, barometric pressure) to contextualize physiological responses within external conditions. When integrated into secure telemedicine platforms, these wearables support encrypted, bidirectional, and continuous data transmission through Wi-Fi, LTE, and Bluetooth Low Energy channels. Clinicians and algorithmic systems can access dashboard visualizations that display temporal trends, threshold alerts, and multi-sensor summaries, enabling proactive intervention and remote triage.

The SiDLY Care Pro wristband represents a clinically certified Class IIa medical-grade device developed according to the Medical Devices Regulation (EU 2017/745) and ISO 13485 standards. Its design prioritizes accuracy, reliability, and telecare functionality for high-risk cardiovascular populations. The device continuously records: 1. Heart rate and rhythm via dual-channel PPG and optional ECG electrodes 2. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) using reflectance oximetry validated against hospital-grade co-oximeters 3. Blood pressure (in selected configurations) utilizing pulse wave analysis and individualized calibration algorithms 4. Autonomic surrogates, including HRV-based stress indices 5. Motor activity and posture, assessed using tri-axial accelerometry and gyroscopy

From a safety standpoint, the SiDLY Care Pro integrates real-time fall detection algorithms, which combine free-fall vector recognition with impact kinetics to discriminate between true and false alarms. Immediate SOS alerting is enabled through a dedicated panic button that establishes automatic voice or message contact with caregivers, emergency medical services, or a 24/7 telemonitoring call center. GPS tracking and customizable geo-fencing functions support location monitoring, sending automatic notifications when users exit predefined safe zones—an essential feature for vulnerable or cognitively impaired individuals. Direct two-way voice communication transforms the wristband into an active telecare node, allowing rapid clinician–patient interaction even in areas with fluctuating cellular signal coverage. This functionality ensures real-time assessment during symptomatic episodes and facilitates guided first-aid support when emergency services are required.

All measurements and alerts are processed within a secure, GDPR-compliant cloud ecosystem. Data undergo segmentation into timestamped epochs and pre-processing steps including:

1. artefact suppression via wavelet decomposition and adaptive filtering 2. feature extraction (e.g., RR intervals, PPG pulse amplitude variability, activity bout segmentation) 3. dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis (PCA)

4. pattern recognition through unsupervised clustering (k-means, DBSCAN) to identify phenotypic trajectories

For cardiac time-series, dynamic time warping (DTW) is applied to compare temporally misaligned rhythm patterns and detect deviations from the individual baseline. The analytics layer includes anomaly detection algorithms that signal sudden changes in heart rate, oxygen saturation, or motion consistency, which may indicate arrhythmic events, heart failure decompensation, respiratory compromise, or post-AMI autonomic instability. Clinical dashboards present multi-day trend maps, cumulative activity metrics, nocturnal physiology comparisons, outlier detection, and patient-specific alerts. These visualizations support both retrospective review (e.g., identifying recurrent symptom-associated patterns) and prospective monitoring (e.g., early identification of worsening health status). The platform’s infrastructure enables role-based access control, granting differentiated permissions to clinicians, caregivers, researchers, and patients. Through mobile and web applications, real-time monitoring, historical trends, and emergency alerts become accessible in a user-centered interface optimized for varying levels of digital literacy.

A key innovation lies in the integration of proprietary artificial intelligence algorithms designed to predict imminent health deterioration. These models synthesize multisensor data - including PPG morphology, HRV indices, circadian activity patterns, gait variability, and SpO2 trends - to identify high-risk transitions associated with arrhythmic events, ischemic symptoms, anxiety-related hyperarousal, and post-AMI autonomic dysregulation. Predictive alerts allow for early therapeutic adjustments and may reduce preventable rehospitalizations.

The multilevel data architecture created by wearable devices such as the SiDLY Care Pro provides a scalable environment for:

1. precision cardiovascular phenotyping 2. remote rehabilitation monitoring 3. real-world epidemiological data collection 4. refinement of predictive algorithms through continuous learning 5. rapid clinical decision-making supported by algorithmic triage

Ultimately, wearable-enabled telemonitoring enhances continuity of care, supports post-AMI recovery trajectories, and contributes to a future in which real-time, personalized cardiovascular management becomes a central pillar of secondary prevention strategies [

20].

1.3. Statement of Significance

| Section |

Summary |

| Problem or Issue |

Early myocardial infarction (MI) in adults under 50 is rising, yet post-discharge monitoring remains limited. Traditional follow-up often fails to capture day-to-day physiological fluctuations and physical inactivity, both of which are critical predictors of recovery and recurrent events. |

| What is Already Known |

Wearable devices can monitor heart rate, oxygen saturation, and activity levels, and telemedicine improves follow-up and adherence. However, evidence specific to young MI survivors—regarding real-world usability, clinical relevance, and patient acceptance—is scarce, and existing studies rarely integrate objective biosignals with patient-reported outcomes. |

| What this Paper Adds |

This study provides a multidimensional, real-world evaluation of a certified medical wearable for early MI survivors. It combines time-series analytics, clinical metrics, and usability data, showing that continuous monitoring is feasible, clinically meaningful, and strongly accepted by patients when clinician feedback is integrated. |

| Who Would Benefit |

Clinicians, digital-health researchers, policymakers, and rehabilitation specialists seeking evidence for implementing remote monitoring in young post-MI populations. |

2. Materials and Methods

The remote monitoring of patients with early myocardial infarction using wearable devices represents a progressive trend in healthcare, reflecting the increased integration of wearable technologies for continuous, real-time health assessment. This approach is particularly relevant in an era where telemedicine and remote patient management are pivotal for chronic disease care and risk mitigation of acute cardiac events. Wearable devices enable continuous data collection, optimizing patient management and reducing the risk of post-infarction complications. The present work aligns with the evolving landscape of personalized medicine, where technology-driven solutions enhance both treatment effectiveness and patient engagement.

This study specifically targets a younger cohort with early myocardial infarction—an important choice given their extended post-event life expectancy and heightened risk for developing long-term complications. Personalized monitoring in this group, addressing both physiological and psychological aspects, is critical for proactive management and improved long-term outcomes. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the utility of wearable devices for remote monitoring of motor activity in patients following early myocardial infarction.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients were randomly selected from a large institutional database comprising approximately 800 individuals who had experienced an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) before the age of 50. This registry includes patients with confirmed ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), documented according to current ESC and ACC/AHA diagnostic criteria, integrating biochemical, electrocardiographic, and imaging-based evidence. For the purposes of this study, stringent inclusion criteria were applied to ensure homogeneity of the analytical cohort and relevance to the research objectives. Eligible participants met the following conditions:

1. Age at the time of the AMI index less than 50 years, ensuring that the sample reflects the population with premature myocardial infarction. 2. A minimum of 12 months elapsed since the index event, permitting stabilization of acute-phase physiological alterations and enabling reliable assessment of long-term recovery patterns. 3. Evidence of myocardial infarction documented by troponin elevation, ischemic symptoms, and compatible ECG or imaging findings. 4. Clinical stability at the time of enrolment, defined as absence of acute coronary syndromes, decompensated heart failure, or significant arrhythmias in the preceding 3 months. 5. Ability to provide informed consent and willingness to participate in remote monitoring through wearable technology.

From the total eligible pool, 80 participants were randomly selected following a stratified approach to balance sex distribution, index MI type, and treatment modality (PCI vs. conservative). Among these, 62 individuals were equipped with a Sidly Care Pro wearable device, which enabled continuous monitoring of physiological and behavioral parameters relevant to post-AMI recovery. A schematic representation of the recruitment process and allocation strategy is provided in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 ensured a representative, clinically stable, and methodologically coherent sample suitable for downstream analyses involving biosignal acquisition, behavioral profiling, and patient-reported outcomes.

2.2. Clinical and Instrumental Evaluation

After obtaining written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional ethical board approval, all enrolled patients underwent a comprehensive and standardized clinical assessment. This multidimensional evaluation was designed to capture cardiovascular status, comorbidity burden, pharmacological regimens, and potential opportunities for therapeutic optimization. A detailed medical history was collected, including: 1. demographic information and cardiovascular risk profile 2. characteristics of the index AMI (STEMI/NSTEMI, culprit vessel, revascularization strategy, complications); 3. comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and obstructive sleep apnea; 4. family history of premature coronary artery disease; 5. lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity habits); 6. pharmacological therapies, with assessment of adherence and potential drug–drug interactions. A comprehensive physical examination was performed, evaluating vital signs, cardiovascular auscultation, evidence of heart failure (NYHA class, peripheral edema, jugular venous pressure), and anthropometric parameters (weight, BMI, waist circumference). Each participant underwent a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram, analyzed for residual ischemic changes, Q-waves, conduction abnormalities, ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmic patterns. Additional non-invasive hemodynamic evaluation included heart rate, blood pressure measurement following ESC guidelines, and assessment of autonomic tone through resting heart rate variability when feasible. Venous blood samples were collected in the fasting state to obtain: 1. lipid profile (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides); 2. glycemic parameters (fasting glucose, HbA1c); 3. renal and hepatic function tests; 4. inflammatory markers when indicated (hs-CRP); 5. cardiac biomarkers if clinically appropriate. Laboratory results were used to guide therapeutic optimization, with tailored adjustments in lipid-lowering agents, antihypertensives, glucose-lowering medications, or antiplatelet therapy where necessary.

2.3. Tele-Monitoring System Application

At the conclusion of the clinical visit, patients were provided with instructions and fitted with the Sidly wearable device for a seven-day monitoring period. The device records electrical signals from cardiac contractions, converting them into digital heart rate (bpm) readouts. Selection criteria ensured exclusion of confounding factors such as pre-existing cardiac disease, pharmacological interventions, or lifestyle modifiers (e.g., smoking, caffeine, recent vigorous exercise). Participants received comprehensive instructions to avoid strenuous activity, caffeine, or food intake at least two hours prior to measurement.

The Sidly device was worn on the non-dominant wrist, ensuring good electrode-skin contact and minimal motion artifact. Device placement and baseline signal stability were verified by trained personnel before starting the measurement period.

This device facilitates remote health monitoring via an online platform directly connected to a Telecenter, enabling real-time health status surveillance and individualized safety thresholds for vital sign alerts. Parameters monitored include heart rate, oxygen saturation, step count, positional changes (syncope risk), and medication timing. All sensors were calibrated prior to the experimental phase to ensure cross-device fidelity.

2.4. Online Questionnaire

After completing seven days of tele-monitoring, patients completed an online questionnaire with three sections. The first collected demographic data (age range, gender, educational attainment). The second section assessed computer literacy, including skills in email use, online transactions, information retrieval, social media, and video conferencing. The third section evaluated attitudes toward tele-monitoring (e.g., preference for integration with smartwatch/phone, desire for manual vs. automated updates, importance of data access, and preferences for direct or clinician-mediated feedback).

2.5. IPAQ

Participants completed the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) to assess physical activity over the preceding week. The IPAQ quantifies time spent in vigorous, moderate, and walking activities, as well as sedentary behavior, considering only activities of at least 10 minutes duration.

2.6. SF36

The Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) questionnaire was administered to quantify patient health status and quality of life. The SF-36 measures eight health domains using 36 items, with responses scored on Likert scales. The final item assesses perceived health changes over the past year.

2.7. DASS21

To evaluate psychological status, the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used, assessing symptoms with seven items for each domain.

2.8. Heart Rate Data Analysis

Heart rate data were acquired automatically every 15 minutes by the Sidly device and stored securely. Data were collected in three time windows: long (24 readings/6 hours), medium (12 readings/3 hours), and short (6 readings/1.5 hours), capturing both acute and circadian variations. After transfer to the secure server, data underwent:

Artifact removal for sensor loss, motion, extreme values (<40 or >180 bpm)

Normalization by z-score for interindividual comparison

Segmentation into time windows

Imputation of isolated missing data by linear interpolation (up to 2 consecutive samples)

Manual and automated annotations defined periods of rest, tachycardia, or bradycardia.

2.9. Dynamic Time Warping Barycenter Averaging (DBA)

The Dynamic Time Warping Barycenter Averaging (DBA) algorithm was applied to compute average heart rate patterns from time series of variable length/alignment. Series within each group were aligned and averaged using DTW, iteratively updated until convergence, to obtain a barycentric profile representative of the group.

2.10. Computational Workflow

The analysis comprised three main stages:

Clustering based on DTW distance to group time series by similarity.

DBA computation within each cluster to create barycentric patterns.

Cluster and barycenter validation by silhouette score, variance, and visual assessment (including PCA-based projection for pattern visualization).

PCA projections facilitated visualization of cluster separability and pattern structure. These analyses identified diverse dynamic profiles such as rest–tachycardia–rest and sustained tachycardia.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Group differences were assessed with ANOVA or t-tests, using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Variance in barycenter patterns and group membership was related to physiological and subjective variables, providing context for the time series findings.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Online Questionnaire

Given the paramount importance of patient confidence in the use of Sidly remote monitoring devices, we developed an online questionnaire to evaluate satisfaction and perceived security associated with device wear. Robust engagement with device features is essential not only for facilitating timely detection of health deterioration in home settings, but also for ensuring effective communication with remote clinical teams.

The cohort predominantly comprised individuals aged 41–50 years (56.1%), male (85.4%), and those with a middle school education (39%). Digital literacy varied: 36.6% demonstrated excellent competency in email communications, with substantial proficiency in online news reading (43.9%) and moderate abilities in banking apps (31.7%), recreational gaming (26.8%), television applications (36.6%), video calling/conferencing (31.7%), social media (36.6%), and messaging systems (36.6%).

Nearly half the respondents (48.8%) regarded remote monitoring as essential for both personal health and broader healthcare system efficacy. Preferences were pronounced for smartwatch-connected systems (73.2%) and those featuring automatic updates (87.8%). A majority favored direct connectivity with specialist telehealth teams (68.3%) and full reimbursement by the national health system (90.2%). The value of continuous home monitoring of vital parameters was underscored by 61%, with over half desiring health feedback directly from the device (53.7%;

Figure 2,

Figure 3), and a clear preference for clinician-generated feedback over AI-based analysis (90.2%).

3.2. Results of the IPAQ Questionnaire

Patient responses were analysed to determine time spent on physical activities during the past seven days. The initial section of the survey addressed occupational activity, revealing that while most participants were employed outside the home, the predominant group neither engaged in vigorous nor moderate work-related physical activity, with walking during work hours typically lasting less than ten minutes.

Assessment of commuting patterns showed that, over the preceding week, the majority relied on cars for daily travel, averaging approximately two hours per day in the vehicle. Active modalities such as cycling and walking were uncommon; most participants reported no use of bicycles and limited walking for their journeys.

Regarding domestic activity, patients performed minimal physical tasks in or around the home, including chores, gardening, repairs, and family care. The largest subgroup did not undertake vigorous activities (such as heavy lifting, chopping wood, or shoveling snow) or moderate activities (such as light lifting, cleaning windows, or polishing) in the prior week.

Recreational and leisure activity levels were similarly low: most patients did not walk for at least ten minutes nor participate in vigorous or moderate exercise or sport during their free time within the last seven days.

The final section of the questionnaire focused on sedentary behaviour, capturing time spent seated at work, home, during training courses, or leisure activities (such as desk work, reading, socializing, or watching television). On both weekdays and weekends, most participants spent approximately two hours each day in sedentary positions.

Demographic profiling identified the largest groups as unemployed, predominantly male, and chiefly holding a middle school diploma.

3.3. Results of the SF36 Questionnaire

The majority of patients consider their health to be good and described their health as about the same as the previous year. The largest portion considers themselves partially limited in performing demanding activities like running, lifting heavy objects, or engaging in strenuous sports. In contrast, they do not consider themselves limited in activities requiring moderate physical effort (like carrying grocery bags, climbing one floor of stairs), bending or kneeling, walking one kilometer, 100 meters, or a few hundred meters, taking a bath, or dressing themselves. However, a perception of partial limitation in climbing a few flights of stairs emerged. In the last 4 weeks, due to physical health, the majority of patients did not reduce the time spent at work, did not perform less than they would have liked, did not perceive greater difficulty in doing their work or other activities, but had to limit some types of work. The predominant group did not reduce their time at work due to emotional health but did perform less due to it, feeling a drop in concentration. In contrast, their physical and emotional health did not interfere with normal social activities with family and friends. The perception of physical pain was mild and did not interfere with their usual work. Over part of the time in the last 4 weeks, the largest number of patients felt “lively and bright,” “very agitated,” “calm and serene,” “full of energy,” “discouraged and sad”; almost never down or without energy; tired for a long time; equally divided between “almost always” and “some of the time” happy.

The majority believed their health and emotional state hardly interfered with social activities, and also stated that they enjoyed excellent health. The patients examined did not have a clear perception of being more likely to get sick than others, nor could they say whether their health was the same as others’ or if there was a possibility of worsening.

3.4. Results of the DASS21 Questionnaire

The DASS21 questionnaire required patients to self-assess symptom frequency over the preceding week, rating each item from zero (never) to three (very often). Most respondents reported rarely experiencing difficulty relaxing, and equally infrequent complaints of dry mouth. The largest proportion indicated never feeling unable to experience positive emotions, nor did they report difficulties in breathing (such as increased respiratory rate or dyspnoea at rest) or initiating activities.

Excessive reactions to specific situations were uncommon, with responses divided between “never” and “sometimes.” Tremors, significant nervousness, panic episodes, or overwhelming feelings of inadequacy were also notably absent among most patients.

Virtually no participants endorsed hopelessness about the future, while symptoms of stress and difficulty relaxing were rare. The prevailing majority did not report depression, persistent discouragement, intolerance of obstacles, feelings related to imminent panic, widespread lack of enthusiasm, or worthlessness.

Feelings of irritability were infrequent, and very few patients noted palpitations or tachycardic sensations in the absence of physical exertion. Nearly all respondents ruled out unprovoked fear or a sense that life was meaningless.

3.5. Results Regarding the Application of the Sidly Telemonitoring System

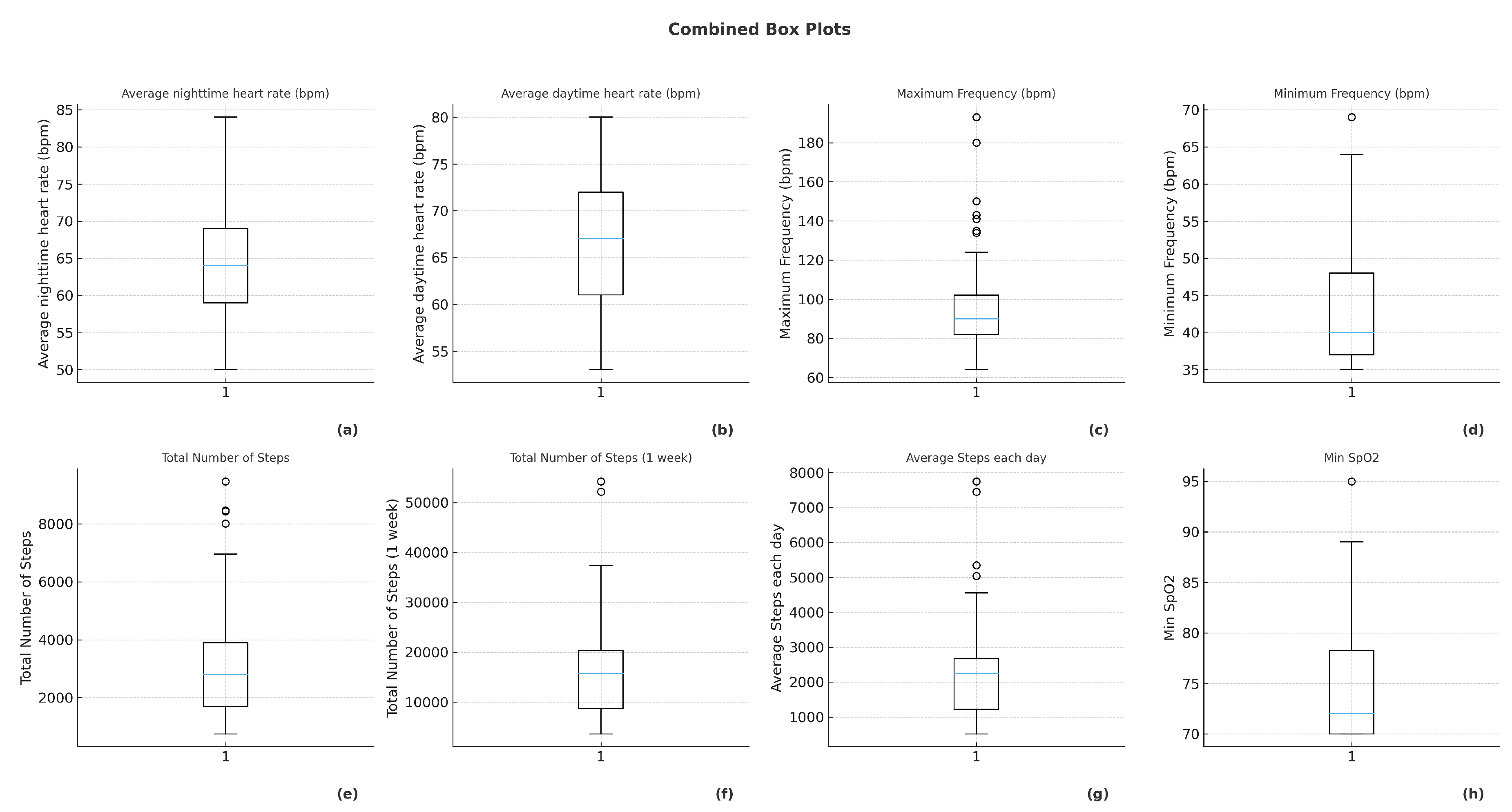

One of the major applications of artificial intelligence is certainly in the field of telemedicine and "smart-home technologies." Thanks to remote patient monitoring and management platforms, it is possible to personalize treatment planning, define the correct medication dosage, and identify patients at risk of adverse events, anticipating potential readmissions. The concept of the “Internet of Things” (IoT) is also increasingly developed: it is based on the use of various electronic devices with embedded sensors in everyday objects, which are then associated with online platforms. The sensor records specific data related to the patient’s health status and transmits them to the remote device via specific connectors. By leveraging IoT, medical staff can monitor numerous vital parameters, recognizing early signs of potential health deterioration. The device chosen for our study was the Sidly watch, with the goal of assessing the usefulness of wearable devices in monitoring motor activity in patients with early myocardial infarction. We examined a total of 80 patients, randomly selected from a database of patients with early myocardial infarction. All patients underwent a follow-up visit, but only 66 agreed to use the device for 7 days. The device enables remote monitoring of heart rate, oxygen saturation, and the number of steps taken each day; it also signals sudden position changes that may indicate syncopal episodes, as well as the exact time to take medication. The average total number of steps over 24 hours was between 2,000 and 4,000 steps (depicted in

Figure 4), the daytime steps were between 1,200 and 2,500 (as depicted in

Figure 4), and the total steps in a week were between 10,000 and 20,000 (

Figure 4). The average oxygen saturation was consistently around 99% with minimum values between 70 percent and 78 percent as depicted in

Figure 4

The minimum heart rate was between 37 and 48 beats per minute as depicted in

Figure 4, and the maximum heart rate was between 80 and 100 beats per minute (see

Figure 4).

The average night-time heart rate was between 58 and 78 beats per minute (shown in

Figure 4), and the average daytime heart rate was between 61 and 72 beats per minute (depicted in

Figure 4).

3.6. Results on Time-Series Clustering

This section presents the outcomes of our heart rate analysis using a multi-scale window extraction approach. By segmenting the raw heart rate time series into short-, medium-, and long-range windows, we characterize patterns and variability at different temporal resolutions. This methodology enables robust assessment of heart rate dynamics, capturing both rapid fluctuations and sustained trends, while handling missing data through interpolation.

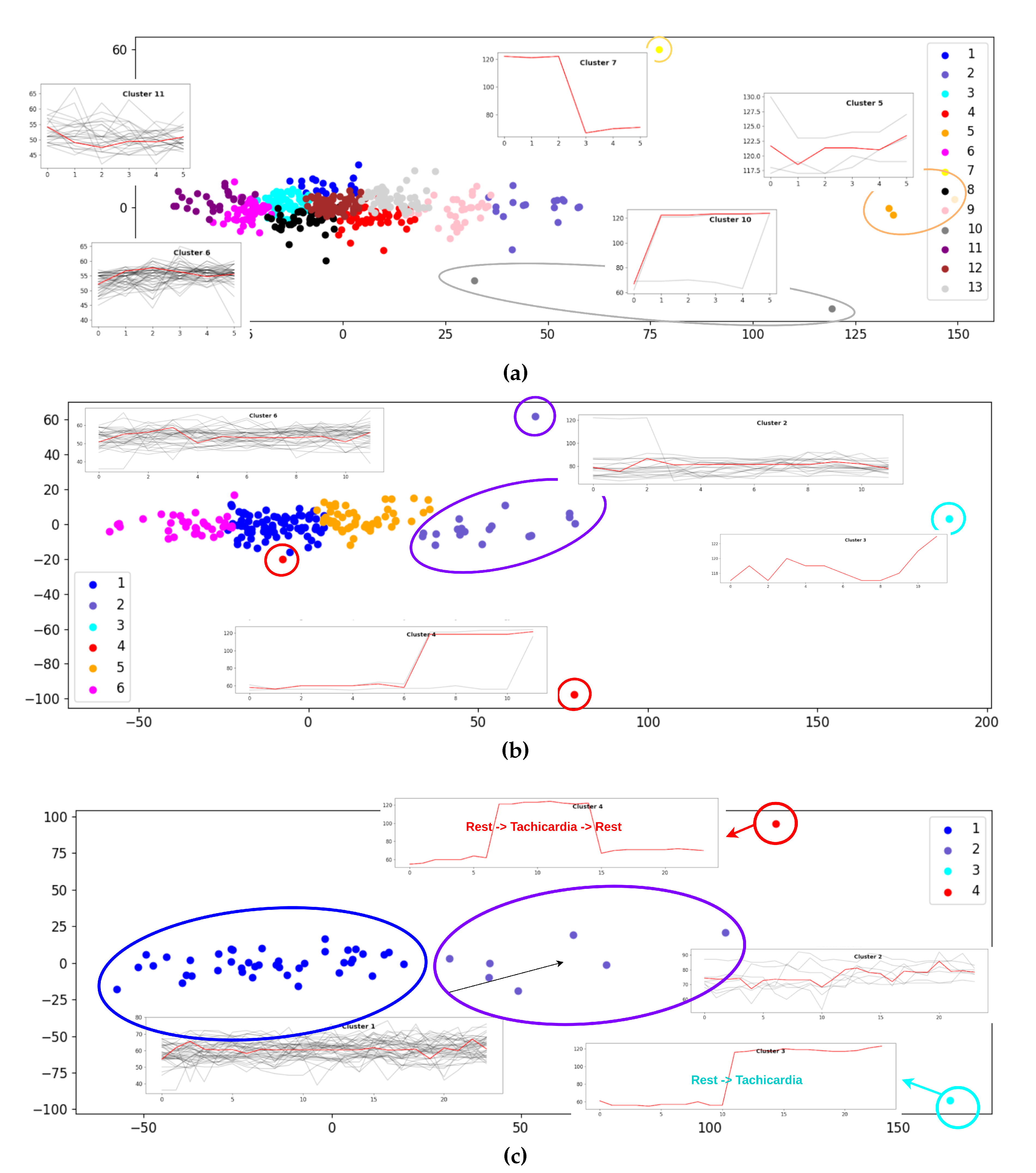

Figure 5 illustrates the representative heart rate patterns derived from short-, medium-, and long-range window segmentation.

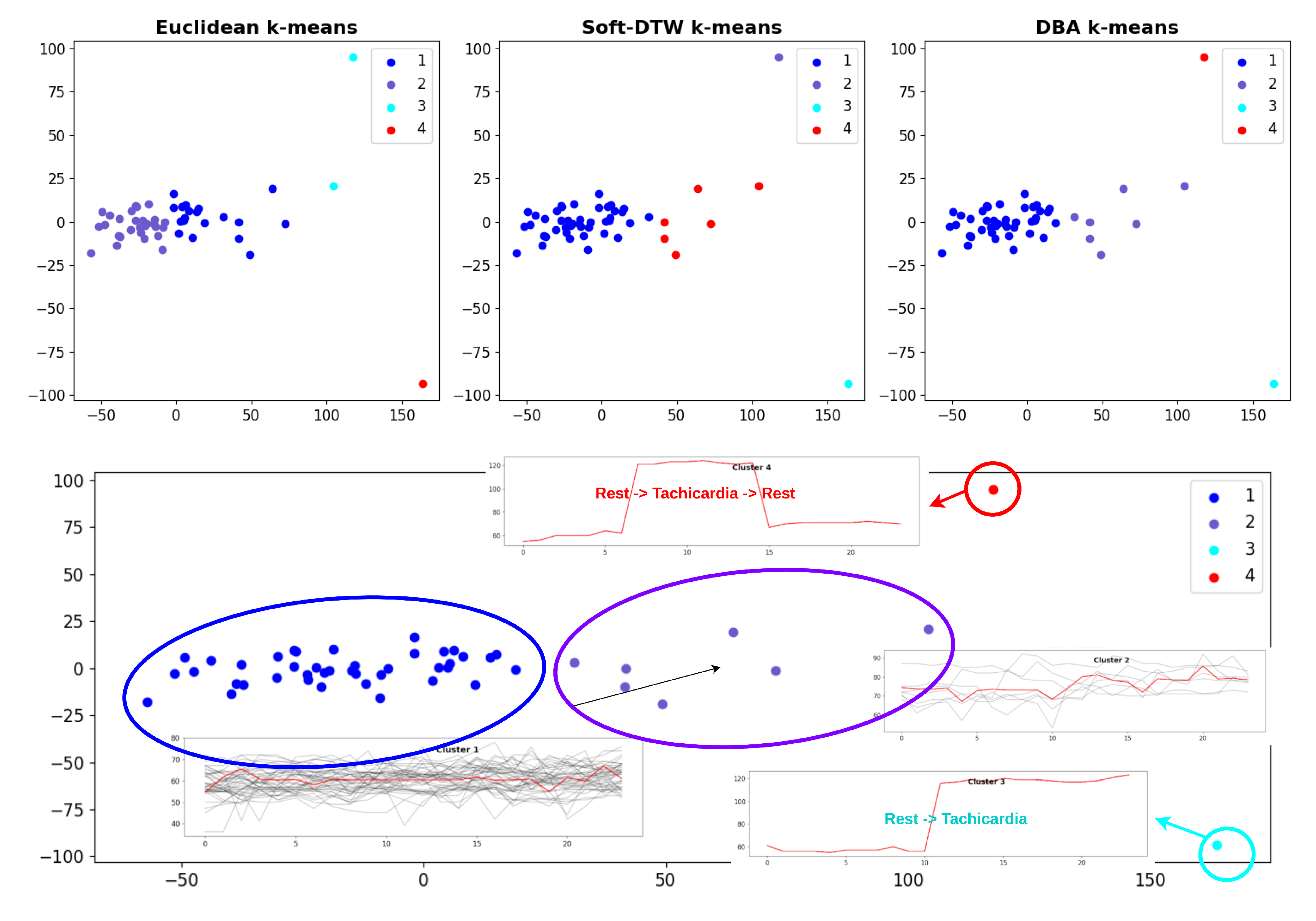

(a) Short-range windows: Show prominent rapid variability and transient dynamics among clusters, emphasizing the system’s responsiveness to brief episodes or artifacts. Each window type is represented by up to 6 measurements, with a tolerance for up to 0 missing values. Number of DBA kmeans clusters extracted is equal to 13. Clusters 7, 10, and 5 are predominantly associated with tachycardic events. Cluster 10 primarily contains windows that capture the transition from resting states to episodes of tachycardia, reflecting a marked increase in heart rate at the onset of activity. Cluster 7, in contrast, includes the unique pattern showing a recovery phase, where heart rate transitions from tachycardia back to rest. Cluster 5 is distinguished by windows representing prolonged, severe tachycardia, characterized by heart rate measurements consistently above 120 bpm for extended durations, notably up to two hours. Conversely, clusters 11 and 6 are more frequently linked to bradycardia or sleep-related patterns. These clusters feature windows with lower heart rate values and stability, indicative of periods of reduced physiological activity such as deep rest or sleep cycles. This differentiation highlights the capability of the clustering approach to identify and segregate physiologically meaningful states within long-term heart rate data. (b) Medium-range windows: Capture intermediate patterns, offering insight into ongoing physiological fluctuations and moderate temporal trends not visible in shorter segments. Each window type is represented by up to 12 measurements, with a tolerance for up to 1 missing values imputed by interpolation. Number of DBA kmeans clusters extracted is equal to 6. (c) Long-range windows: Reveal broad temporal dynamics, supporting the identification of sustained shifts or gradual modulations in heart rate over time. Each window type is represented by up to 24 measurements, with a tolerance for up to 2 missing values imputed by interpolation. Number of DBA kmeans clusters extracted is equal to 4. Clusters 3 and 4 are comprised of two distinct outlier patterns: one portrays a complete cycle from rest to tachycardia and back to rest, while the other exhibits a transition exclusively from rest to tachycardia. In contrast, differences between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 are primarily reflected in their average heart rate; Cluster 1 displays a mean of approximately 60 bpm, whereas Cluster 2 centers around 75 bpm.

The clustering of windows across these scales supports nuanced temporal analysis, enabling differentiation between brief, intermediate, and persistent heart rate changes—tools valuable for physiological interpretation and clinical segmentation.

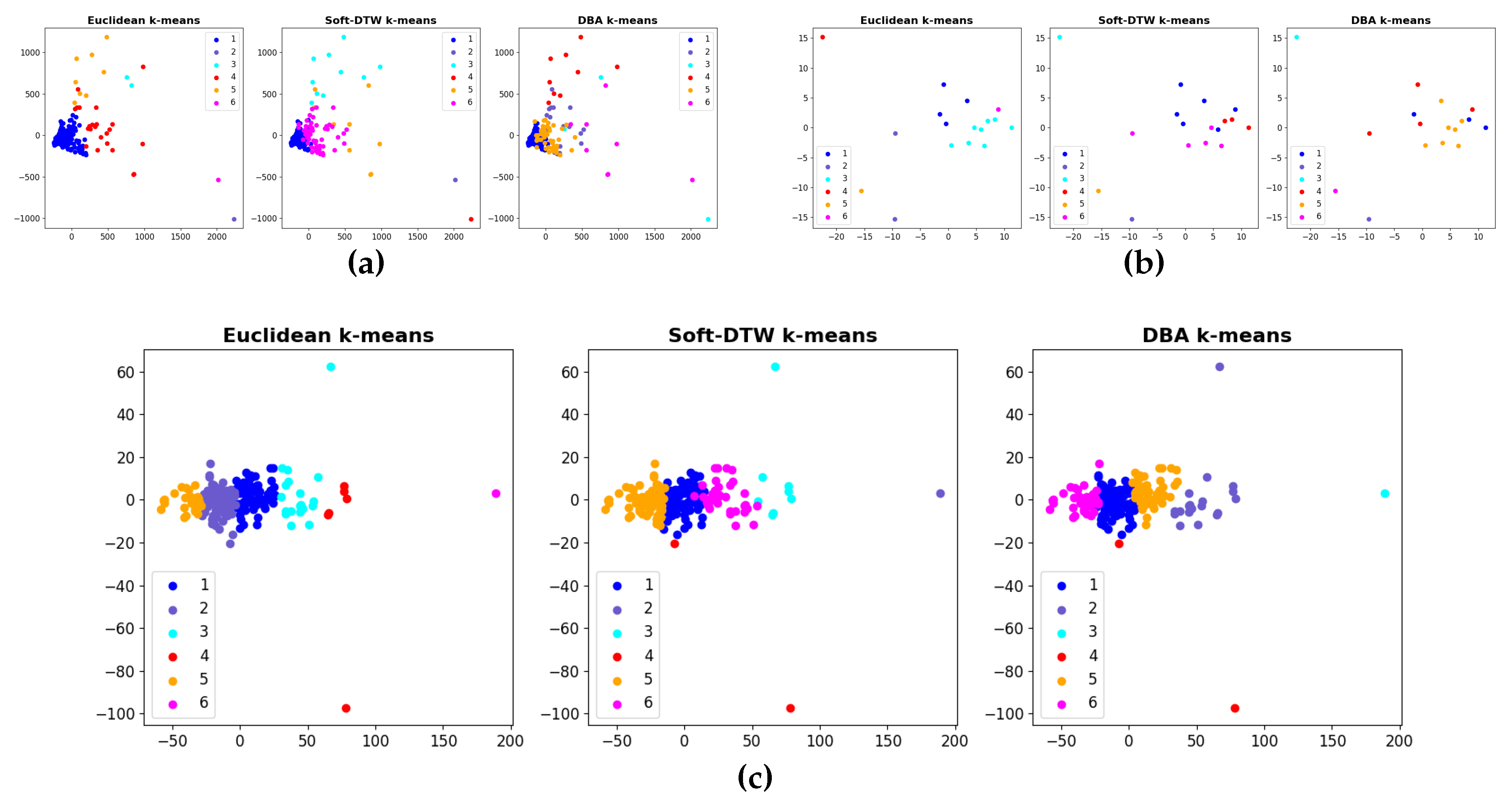

To further evaluate the capability of our clustering methodology across heterogeneous physiological signals, we extended our analysis to multiple data modalities, including pedometer activity counts, oxygen saturation (

) levels, and heart rate measurements. This multi-sensor approach enables the identification of distinct behavioral and physiological patterns, supporting integrated insights into daily activity, cardiorespiratory status, and dynamic transitions between states.

Figure 6 summarizes clustering results obtained for each data type, revealing characteristic groupings and transitions reflected in step activity, oxygen saturation fluctuations, and heart rate variability over time. For this analysis, medium-range windows were utilized with the number of clusters fixed at six. While the cluster count was kept constant, we varied the clustering distance metric to compare three different configurations of TimeSeries KMeans: Euclidean KMeans, Soft-DTW KMeans, and DBA KMeans. This approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of how different distance measures impact the clustering results when applied to time-series physiological data, allowing us to assess both shape-based and alignment-based similarities across heart rate segments. Following this comprehensive comparison, DBA KMeans was chosen as the primary clustering method for subsequent analyses. This selection is based on DBA’s ability to effectively capture the temporal dynamics of time series data by computing barycenters under the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) metric. Unlike traditional Euclidean-based KMeans, DBA KMeans better accommodates temporal shifts and distortions within the sequences, yielding more meaningful and coherent clusters for physiological signals.

Finally,

Figure 7 presents an in-depth analysis of long-range heart rate patterns, revealing sustained temporal dynamics that extend across extended time intervals. By examining these patterns, we capture slow physiological modulations and trends that are often overlooked in short or medium-term analyses. This comprehensive long-range perspective enables the identification of persistent states such as prolonged tachycardia, bradycardia, or recovery phases, which have critical implications for understanding autonomic regulation and cardiovascular health. Through clustering of these extended windows, distinct phenotypic behaviors emerge, highlighting the significance of temporal scale in heart rate variability analysis and its potential clinical applications. This approach facilitates improved characterization of chronic conditions and dynamic physiological responses over hours or longer periods.

4. Discussion

Early myocardial infarction (MI) presents a significant clinical challenge, necessitating rigorous monitoring during the recovery phase to minimize long-term sequelae and optimize rehabilitation. Wearable technologies, exemplified by the Sidly device used in this study, offer promising opportunities for continuous remote surveillance of vital signs and motor activity, enabling timely intervention in cases of acute physiological deterioration. Our findings provide meaningful insights into both the effectiveness of such technologies and patient experience in a young post-MI population, while also introducing an advanced analytical dimension through multiscale time-series clustering.

4.1. Patient Acceptance, Usability, and Behavioral Insights

Our data indicate strong patient satisfaction and acceptance of digital remote monitoring. Most participants expressed a preference for smartwatch-based systems (73.2 percent) and emphasized the critical role of national health system reimbursement (90.2 percent) in promoting equitable adoption. Moreover, 90.2 percent of patients favored personalized feedback delivered by clinical staff, underscoring that, despite technological advances, human interaction remains a cornerstone of trust, reassurance, and adherence in digital cardiology. Consistent with prior literature, IPAQ-derived metrics revealed profound sedentary habits, characterized by reliance on vehicular transport and minimal engagement in sustained physical activity. Only a minority reached recommended daily walking targets, highlighting a substantial unmet need in secondary prevention for young MI survivors. Wearables may thus serve not only as monitoring tools, but also as behavioral activators capable of delivering real-time prompts, goal setting, and motivational feedback. Although most patients reported no major limitations in daily living, partial difficulties persisted during high-exertion tasks, suggesting residual functional compromise. Nevertheless, preserved social and occupational participation indicates a high level of resilience in this demographic, which may facilitate long-term adherence to technology-assisted rehabilitation.

4.2. Objective Physiological Monitoring and Clinical Implications

Sidly-enabled continuous monitoring revealed: 1. low overall physical activity (2,000–4,000 steps/day), 2. stable oxygen saturation (mean 99 percent, with occasional transient minima) 3. predominantly normal heart rate profiles, punctuated by rare bradycardic episodes (37–48 bpm). These observations align with known post-MI trajectories, where reduced physical activity and autonomic imbalance may coexist despite apparent symptomatic stability. The detection of episodic bradycardia highlights the value of continuous monitoring for recognizing asymptomatic but potentially relevant arrhythmic patterns. Continuous, real-time data capture enables precise treatment adjustment, early detection of deterioration, and targeted rehabilitation strategies—approaches shown to reduce hospitalizations and accelerate recovery. Importantly, remote monitoring minimizes the burden of outpatient visits and improves care continuity while reducing overall healthcare costs.

4.3. Multiscale Heart Rate Time-Series Clustering: Physiological and Clinical Interpretation

A key innovation of this study lies in the integration of multi-scale, unsupervised clustering applied to heart rate dynamics. This advanced analytical approach allowed the characterization of different temporal levels of autonomic behavior (short, medium, and long range) revealing clinically interpretable patterns that extend far beyond simple mean heart rate analysis.

Short-range clustering: autonomic reactivity and transient states

Short-range windows captured rapid fluctuations and transient states. Among 13 identified clusters: - Cluster 10 reflected transitions from rest to tachycardia, indicating rapid autonomic activation during activity onset. - Cluster 7 uniquely represented recovery trajectories from tachycardia to rest—patterns associated with parasympathetic reactivation. - Cluster 5 highlighted sustained, severe tachycardia (>120 bpm for up to two hours), a clinically relevant signal potentially indicative of deconditioning, stress, or arrhythmic substrates. - Clusters 11 and 6 corresponded to bradycardic or sleep-related states, capturing periods of autonomic quiescence and deep rest.

These findings demonstrate the system’s ability to distinguish meaningful physiological states and may support individualized risk stratification. For example, prolonged tachycardia clusters may identify subjects requiring intensified rehabilitation or medication titration.

Medium-range clustering: intermediate autonomic patterns

Medium-range windows provided an intermediate temporal resolution, revealing autonomic modulations that are not apparent in short-term segments. Six clusters captured moderate fluctuations, offering insight into diurnal patterns, the stability of recovery phases, and activity-related oscillations. Long-range clustering: sustained physiological states and recovery phenotypes. Long-range clustering identified 4 stable patterns, reflecting sustained physiological behaviors across hours: - Clusters 3 and 4 contained outlier sequences representing full cycles (rest → tachycardia → rest) or unidirectional transitions (rest → tachycardia). - Clusters 1 and 2 differed primarily by baseline heart rate (60 vs. 75 bpm), highlighting heterogeneity in resting autonomic profiles in young post-MI patients. Notably, long-range phenotyping enables identification of individuals with chronic sympathetic predominance, maladaptive circadian trends, or inadequate recovery—all factors associated with poorer long-term cardiovascular prognosis.

4.4. Multimodal Clustering Across Heart Rate, SpO2, and Activity

By extending clustering to pedometer counts and oxygen saturation, the system identified recurring multimodal patterns linking: 1. reduced activity with stable oxygen saturation 2. higher activity periods with predictable tachycardic responses 3. sporadic desaturation clusters requiring clinical correlation. Comparing Euclidean, Soft-DTW, and DBA KMeans, DBA KMeans emerged as the superior method due to its capacity to handle temporal misalignment—a critical advantage for physiological time series. This reinforces its value for chronic disease monitoring where temporal dynamics carry essential biological information.

These findings echo prior evidence supporting remote monitoring’s ability to improve therapy adherence, detect abnormalities earlier, and facilitate personalized rehabilitation [21,22,23]. Our data extend these insights by demonstrating that time-series clustering offers a new dimension of “digital phenotyping”, capturing physiological states not detectable via traditional averages or threshold-based alerts.

This approach has potential applications in: autonomic risk profiling, arrhythmia surveillance, rehabilitation intensity tuning, early warning systems powered by machine learning. Importantly, the population studied (<50 years) is often underrepresented in cardiovascular research despite their long-term vulnerability, making these findings particularly relevant for the development of targeted secondary prevention strategies [

21].

In sum, our findings affirm remote monitoring’s utility as an adjunct to conventional post-MI management. When supported by appropriate clinical oversight and human interaction, wearable technologies can facilitate improved recovery trajectories, reduced hospitalizations, and the emergence of a more proactive, responsive, and sustainable model of cardiovascular care.

5. Limitations

Although wearable devices such as Sidly have provided good accuracy for basic monitoring (heart rate, oxygen saturation, and motor activity), some parameters, such as detecting postural changes in cases of syncope episodes, may be influenced by errors or false positives. It is important to improve the sensitivity of the sensors to minimize such limitations, perform rigorous validation of wearable devices in real clinical scenarios, and, if necessary, integrate data from the devices with other forms of monitoring or medical consultations. Moreover, the economic sustainability and reimbursement of the device by the national healthcare system were seen as essential for wider technology dissemination. Cost and accessibility are determining factors for the continuation of long-term monitoring and for expanding its use. An additional limitation of the study is the small sample size of patients monitored. The small sample size may compromise the generalizability of the results and increase the risk of biases, as limited samples may not adequately represent the general population. This could lead to unreliable conclusions or an overestimation or underestimation of the effectiveness of the monitored devices. Expanding the sample in future studies will provide more robust and meaningful results, improving the validity and reliability of the conclusions.

A critical aspect that requires attention is the limited duration of monitoring (only 7 days), which, while allowing for immediate and useful data collection to assess the initial treatment response, limits the ability to analyze the long-term effects of wearable devices on post-myocardial infarction recovery and recurrence prevention. Monitoring patients over a more extended period would allow observation of how the consistency of device use may affect vital parameters over time and whether adopting wearable technologies can indeed reduce the risk of future cardiovascular events.

The heterogeneity of the sample represents another limitation, as the lack of detailed stratification based on relevant factors such as the severity of the cardiac event, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), and the level of physical activity before the infarction can introduce significant biases into the results. Patients with different severities of infarction or pre-existing health conditions may respond very differently to wearable device use, making it more challenging to draw universal conclusions about the effectiveness of remote monitoring. In the future, it would be useful to stratify data for these factors in order to better understand how remote monitoring adapts to the specific needs of different patient types.

These limitations must be considered when planning future large-scale implementation of remote monitoring through wearable devices. Overcoming the limited study duration, addressing sample heterogeneity, and improving measurement precision are crucial steps to ensure that wearable devices can be truly useful in clinical practice to monitor early myocardial infarction patients effectively and safely over the long term.

6. Future Developments

Future developments of this study aim to expand the sample and extend the follow-up period to collect long-term data that can provide a more comprehensive view of the effectiveness of remote monitoring and recurrence prevention in young patients with early myocardial infarction. Additionally, we plan to include an economic analysis to assess the sustainability of the proposed model, aiming to analyze not only clinical benefits but also the costs associated with large-scale implementation. The economic component is crucial to evaluate the practical feasibility and potential impact of remote monitoring in the healthcare context. Finally, another step may include direct comparison between different wearable devices to strengthen technological recommendations and select the most effective and cost-efficient solutions to integrate and expand the results obtained so far.

7. Conclusion

The results of this study confirm that wearable devices like Sidly offer significant benefits in monitoring motor activity and vital parameters in patients with early myocardial infarction. Remote monitoring, combined with continuous and personalized feedback, can facilitate recovery and reduce the risk of complications. However, it is necessary to improve the precision of the data (especially regarding acute event detection) and ensure that the healthcare system adequately supports the adoption of these technologies.

Additionally, the active participation of patients, which proved to be crucial in our study, suggests that technology should be integrated into a context that includes both self-management by the patient and continuous support from healthcare professionals. Only through an integrated approach, combining technological innovation and effective communication between the patient and the medical team, will it be possible to maximize the effectiveness of remote monitoring for patients with early myocardial infarction.

Future developments may include the improvement of wearable devices, integration with other healthcare technologies, and a deeper evaluation of the long-term impact of these devices on physical recovery and quality of life for patients.

What emerged from our study could have a significant impact on the applicability of such devices in clinical practice. We consider it essential to promote the implementation of a remote monitoring protocol by integrating wearable devices such as Sidly into the post-infarction follow-up routine. Healthcare professionals could define personalized protocols for each patient, using real-time data to intervene promptly in case of vital parameter anomalies or during physical activity. The creation of automatic alerts for critical events, such as reduced oxygen saturation or bradycardia episodes, could enhance treatment effectiveness.

At the same time, we believe that patient education and awareness are critical: active patient participation was a crucial component of our study. To maximize the benefits of remote monitoring, it is essential that patients receive proper training on the correct use of devices and the interpretation of the data collected. Targeted education sessions could improve self-management and patient awareness of their health status. This would enable the definition of individualized therapeutic paths: data collected via wearable devices could be used to further personalize post-infarction treatment. For example, a patient showing signs of low physical activity or an irregular heart rate could benefit from a more targeted cardiovascular rehabilitation program. In this context, remote monitoring would allow dynamic adaptation of therapies.

However, economic sustainability and the reformulation of healthcare policies represent the biggest challenges. An important next step for the widespread adoption of technologies like Sidly is the support of the healthcare system. Policies should include incentives for healthcare professionals to adopt remote monitoring devices and ensure financial coverage for patients. Economic sustainability is crucial to make it an available and accessible tool on a large scale. Finally, we recommend that wearable device manufacturers invest in technological improvements, focusing on sensor accuracy and refining the ability to detect acute events. Additionally, further clinical studies should explore the long-term impact of remote monitoring, assessing not only the clinical benefits but also its effect on quality of life, reduction in relapses, and adherence to therapy.

In conclusion, the introduction of remote monitoring devices in the management of myocardial infarction could represent a breakthrough in treatment personalization and complication prevention. However, the real success of this approach will depend on the synergistic integration of technology, healthcare professionals, and patients.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Only synthetic data were generated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. Journal of the American college of cardiology 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Gautam, N.; Garg, N. Acute myocardial infarction in very young adults. Indian Heart Journal 2016, 68, 808–813. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren, A.; Ghaffari, S. Acute Myocardial Infarction: Etiologies and Mimickers in Young Adults. Journal of the American Heart Association 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, X. Risk factor differences in acute myocardial infarction between young and older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2019, 21, 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Elabbassi, H.; Bahadi, A. Acute myocardial infarction among young adults under 40 years of age. Risk factors, clinical and angiographic characteristics. Cor Vasa 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, S.; colleagues. Trends in Risk Factor Prevalence and Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Advances 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.; et al. Wearable Devices in Cardiovascular Medicine. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; et al. Mobile Apps and Wearable Devices for Cardiovascular Health. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.; et al. Wearable technology and the cardiovascular system. The Lancet Digital Health 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duncker, D.; Svennberg, E. Wearable Devices for Cardiac Rhythm Monitoring. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; et al. Selecting Wearable Devices to Measure Cardiovascular Functions. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Behfar, A.; Narula, J.; Kanwar, A.; Lerman, A.; Cooper, L.; Singh, M. Acute myocardial infarction in young individuals. Proceedings of the Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2020, 95, 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Stitziel, N.O.; MacRae, C.A. A clinical approach to inherited premature coronary artery disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics 2014, 7, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Zekavat, S.M.; Collins, R.L.; Roselli, C.; Natarajan, P.; Lichtman, J.H.; D’onofrio, G.; Mattera, J.; Dreyer, R.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing to characterize monogenic and polygenic contributions in patients hospitalized with early-onset myocardial infarction. Circulation 2019, 139, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krittanawong, C.; Luo, Y.; Mahtta, D.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Z.; Jneid, H.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Mahboob, A.; Baber, U.; Mehran, R.; et al. Non-traditional risk factors and the risk of myocardial infarction in the young in the US population-based cohort. IJC Heart & Vasculature 2020, 30, 100634. [Google Scholar]

- Nou, E.; Lo, J.; Grinspoon, S.K. Inflammation, immune activation, and cardiovascular disease in HIV. Aids 2016, 30, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardoku, R.; Blair, C.; Demmer, R.; Prizment, A. Association between physical inactivity and health-related quality of life in adults with coronary heart disease. Maturitas 2019, 128, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, T.; Haffner, S.M.; Schulte, P.J.; Thomas, L.; Huffman, K.M.; Bales, C.W.; Califf, R.M.; Holman, R.R.; McMurray, J.J.; Bethel, M.A.; et al. Association between change in daily ambulatory activity and cardiovascular events in people with impaired glucose tolerance (NAVIGATOR trial): a cohort analysis. The Lancet 2014, 383, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsack, J.C.; Coravos, A.; Bakker, J.P.; Bent, B.; Dowling, A.V.; Fitzer-Attas, C.; Godfrey, A.; Godino, J.G.; Gujar, N.; Izmailova, E.; et al. Verification, analytical validation, and clinical validation (V3): the foundation of determining fit-for-purpose for Biometric Monitoring Technologies (BioMeTs). npj digital Medicine 2020, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccuto, F.; De Rosa, S.; Torella, D.; Veltri, P.; Guzzi, P.H. Will artificial intelligence provide answers to current gaps and needs in chronic heart failure? Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, P.X.; Chan, W.K.; Ying, D.K.F.; Rahman, M.A.A.; Peariasamy, K.M.; Lai, N.M.; Mills, N.L.; Anand, A. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Digital Health 2022, 4, e676–e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Study cohort and data collection workflow. Flow diagram illustrating patient selection and data acquisition. From an initial cohort of 800 individuals with early-onset acute myocardial infarction (AMI; age <50 years), 80 participants underwent clinical follow-up and completed standardized questionnaires (IPAQ, DASS21, and SF-36). Among these, 62 patients wore the Sidly Care device for 7 consecutive days, while 41 participants completed the online questionnaire only.

Figure 1.

Study cohort and data collection workflow. Flow diagram illustrating patient selection and data acquisition. From an initial cohort of 800 individuals with early-onset acute myocardial infarction (AMI; age <50 years), 80 participants underwent clinical follow-up and completed standardized questionnaires (IPAQ, DASS21, and SF-36). Among these, 62 patients wore the Sidly Care device for 7 consecutive days, while 41 participants completed the online questionnaire only.

Figure 2.

Results about self-monitoring importance.

Figure 2.

Results about self-monitoring importance.

Figure 3.

Importance of wearable feedback for improving health status.

Figure 3.

Importance of wearable feedback for improving health status.

Figure 4.

Measured parameters. Box plots summarizing eight physiological and behavioral metrics recorded across participants. Each panel (a–h) displays the distribution of a distinct parameter: (a) average nighttime heart rate (bpm), (b) average daytime heart rate (bpm), (c) maximum frequency (bpm), (d) minimum frequency (bpm), (e) total number of steps, (f) total number of steps over one week, (g) average steps per day, and (h) minimum SpO2. Boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent the median, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and outliers are shown as individual points.

Figure 4.

Measured parameters. Box plots summarizing eight physiological and behavioral metrics recorded across participants. Each panel (a–h) displays the distribution of a distinct parameter: (a) average nighttime heart rate (bpm), (b) average daytime heart rate (bpm), (c) maximum frequency (bpm), (d) minimum frequency (bpm), (e) total number of steps, (f) total number of steps over one week, (g) average steps per day, and (h) minimum SpO2. Boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent the median, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and outliers are shown as individual points.

Figure 5.

Patterns extracted from heart rate data using short-, medium-, and long-range window segmentation and DBA kmeans with different number of clusters. (a) Representative heart rate patterns identified from short-range windows, capturing rapid variability and transient dynamics. Number of clusters: 13. (b) Patterns from medium-range windows, illustrating intermediate trends and fluctuations. Number of clusters: 6. (c) Long-range window patterns, highlighting broader temporal dynamics in heart rate signals. Number of clusters: 4. Each pattern set is derived from windows containing up to 6/12/24 measurements, allowing no more than 0/1/2 missing values, which are imputed by interpolation when present.

Figure 5.

Patterns extracted from heart rate data using short-, medium-, and long-range window segmentation and DBA kmeans with different number of clusters. (a) Representative heart rate patterns identified from short-range windows, capturing rapid variability and transient dynamics. Number of clusters: 13. (b) Patterns from medium-range windows, illustrating intermediate trends and fluctuations. Number of clusters: 6. (c) Long-range window patterns, highlighting broader temporal dynamics in heart rate signals. Number of clusters: 4. Each pattern set is derived from windows containing up to 6/12/24 measurements, allowing no more than 0/1/2 missing values, which are imputed by interpolation when present.

Figure 6.

Comparison of clustering results on three types of physiological measurements using different algorithms. (a) Pedometer data clustered with Euclidean k-means, soft-DTW k-means, and DBA k-means, showing distinct activity distribution patterns. (b) Oxygen saturation measurements clustered with the same three methods, highlighting variability and group separation. (c) Heart rate data clustered by Euclidean k-means, soft-DTW k-means, and DBA k-means, demonstrating temporal pattern diversity. Each clustering is performed on windows containing up to 12 measurements, with a maximum of 1 missing values imputed by interpolation.

Figure 6.

Comparison of clustering results on three types of physiological measurements using different algorithms. (a) Pedometer data clustered with Euclidean k-means, soft-DTW k-means, and DBA k-means, showing distinct activity distribution patterns. (b) Oxygen saturation measurements clustered with the same three methods, highlighting variability and group separation. (c) Heart rate data clustered by Euclidean k-means, soft-DTW k-means, and DBA k-means, demonstrating temporal pattern diversity. Each clustering is performed on windows containing up to 12 measurements, with a maximum of 1 missing values imputed by interpolation.

Figure 7.

Example of heart rate pattern analysis with medium-range windows extracted from raw data. (a) Clusters of heart rate measurements identified using our methodology for pattern discovery, with each window containing up to 24 measurements and allowing a maximum of 2 NaN values. Missing values in these windows are interpolated. (b) Representative long-term heart rate patterns corresponding to these DBA clusters, illustrating temporal dynamics and variability.

Figure 7.

Example of heart rate pattern analysis with medium-range windows extracted from raw data. (a) Clusters of heart rate measurements identified using our methodology for pattern discovery, with each window containing up to 24 measurements and allowing a maximum of 2 NaN values. Missing values in these windows are interpolated. (b) Representative long-term heart rate patterns corresponding to these DBA clusters, illustrating temporal dynamics and variability.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).