1. Introduction

According to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is classified as class IA as a method of treating patients after myocardial infarction, after myocardial revascularization, with chronic coronary syndrome, and with heart failure. In Poland, until 12 December 2015, telemedicine functioned rather as a theoretical concept, without any real possibility of its application. It was not until the Act of the 9th of October 2015 on the change of the Act on the Healthcare Information System and of certain other Acts (Journal of Laws, item 1991) and the amendment of the Act on the Medical and Dental Professions in December 2015 that its practical application was possible. One of the factors which had a major impact on the rapid development of cardiac telerehabilitation was the COVID-19 pandemic, when the availability of inpatient cardiac rehabilitation (CR) was completely abolished, and patients immediately after acute coronary syndromes (ACS) required careful monitoring and provision of rehabilitation opportunities.

The aim of this study was to assess whether remote cardiac rehabilitation conducted during the epidemic threat (the study group) provided a similar improvement in exercise capacity as inpatient rehabilitation before the COVID-19 pandemic (the reference group).

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, we analyzed data from 60 patients in the study group, who participated in cardiac telerehabilitation between 30 July 2021 and 30 June 2022, and 359 patients in the reference group, who participated in inpatient rehabilitation in the years preceding the pandemic at a tertiary referral centre. The patients in the study group and in the reference group were referred for rehabilitation after ACS and percutaneous coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting.

In accordance with the requirements of the insurer (the National Health Fund), the telerehabilitation programme [

1] took place during 24 sessions within a maximum of 90 consecutive days. Our centre preferred the patients to have rehabilitation sessions without breaks other than the days off from work, but if necessary, the patient could take breaks between sessions. On the first day of the programme, the patient was admitted to the centre and qualified for the rehabilitation programme by a cardiologist. This qualification consisted in conducting an interview with the patient, a physical examination, and in determining the pharmacological treatment and its compliance with the ESC standards (the percentages of patients from the study group taking various medications are presented in

Table 1), and in an analysis of the laboratory tests performed so far, in measuring the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, body mass and height, as well as in an assessment of the patient’s mental state by a psychologist. It was also checked whether the patient had any contraindications to rehabilitation, such as: anaemia with haemoglobin concentration below 10 g/l, inflammation, unstable angina pectoris, myocarditis, pulmonary embolism, peripheral embolism, heart failure in the period of decompensation or atrioventricular conduction disorders requiring an implantation of a cardiac pacemaker.

On the second day of the programme, the physician qualifying the patient for telerehabilitation performed an electrocardiographic stress test (ECG) according to the Bruce-Ramp protocol, assessed the heart rhythm, the fact of reaching the heart rate limit, the presence of electrocardiographic signs of myocardial ischemia or new disturbances of rhythm or conduction.

On days 3, 4, and 5 of the programme, patients from the study group were educated on how to use the telerehabilitation device. This included learning how to use the telerehabilitation monitoring equipment: measuring the heart rate, blood pressure, body mass, following the planned exercise programme, assessing the level of exertion according to the Borg scale. The patients also took part in meetings with a psychologist, who helped them to cope with possible symptoms of depression and anxiety related to the disease, and with a dietitian, who taught them the principles of preparing a healthy diet. On days 6-23, the actual rehabilitation of the patients took place. Before each training session, during a telephone conversation, the patients answered questions about their current health, well-being, and the medications taken. Then, they sent their resting ECG record as well as their blood pressure and body mass measurements to the monitoring center. If there were no contraindications, the patient obtained consent to start the training session. In order to improve exercise capacity, three forms of exercise were recommended: endurance training, respiratory muscle training, and resistance and stretching training. On the last day, a final exercise ECG test was performed according to the Bruce–Ramp protocol.

Having been educated in the use of the telerehabilitation device, the patients performed training outside the centre; this included walking, cycling, training on a stationary cycloergometer or treadmill (if available). If the training went according to plan, immediately after the training session, the telerehabilitation device, following a signal from the patient, sent an ECG to the monitoring center via a mobile phone network. All the data sent by the patient were collected, analyzed and stored in the monitoring center in order to assess the safety, effectiveness and correctness of the rehabilitation carried out by the patients. On the basis of the assessment of the intensity of the exertion as perceived by the patients according to the Borg scale and of the electrocardiograms recorded during the training, decisions were made about the further rehabilitation process, and especially about the possibility or necessity of increasing or decreasing the load.

For patients from the reference group, training at the inpatient centre included morning gymnastics, endurance training on a cycloergometer (twice a day for 10-20 minutes), resistance training on a multi-gym, a rowing machine or an elliptical bike, Nordic walking and breathing training. The patients had also specially organized meetings with a psychologist, who conducted relaxation therapy and with a dietitian, who analyzed individual eating habits and recommended dietary modifications if necessary.

Both cardiac telerehabilitation and inpatient rehabilitation were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Working Group on Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Polish Cardiac Society. The electrocardiogram, blood pressure and body mass of patients participating in the remote rehabilitation program were monitored by means of the telemedicine platform manufactured by Pro-PLUS S.A. Polska.

Statistical analysis included the Mann-Whitney U test, Student’s t-test and chi-square test.

3. Results

Patients from both groups were compared in terms of demographic and anthropomorphic as well as clinical characteristics, and exercise test results. The results are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Statistical analysis showed a statistically significant difference only in the age of patients participating in the study in comparison with the reference group. The median age for the group of centre-based patients was 60, and for the patients participating in telerehabilitation it was 65.

There was also a numerical difference between the percentage of women in the study group and in the reference group, but (like the difference in mean BMI values) it turned out to be statistically not significant.

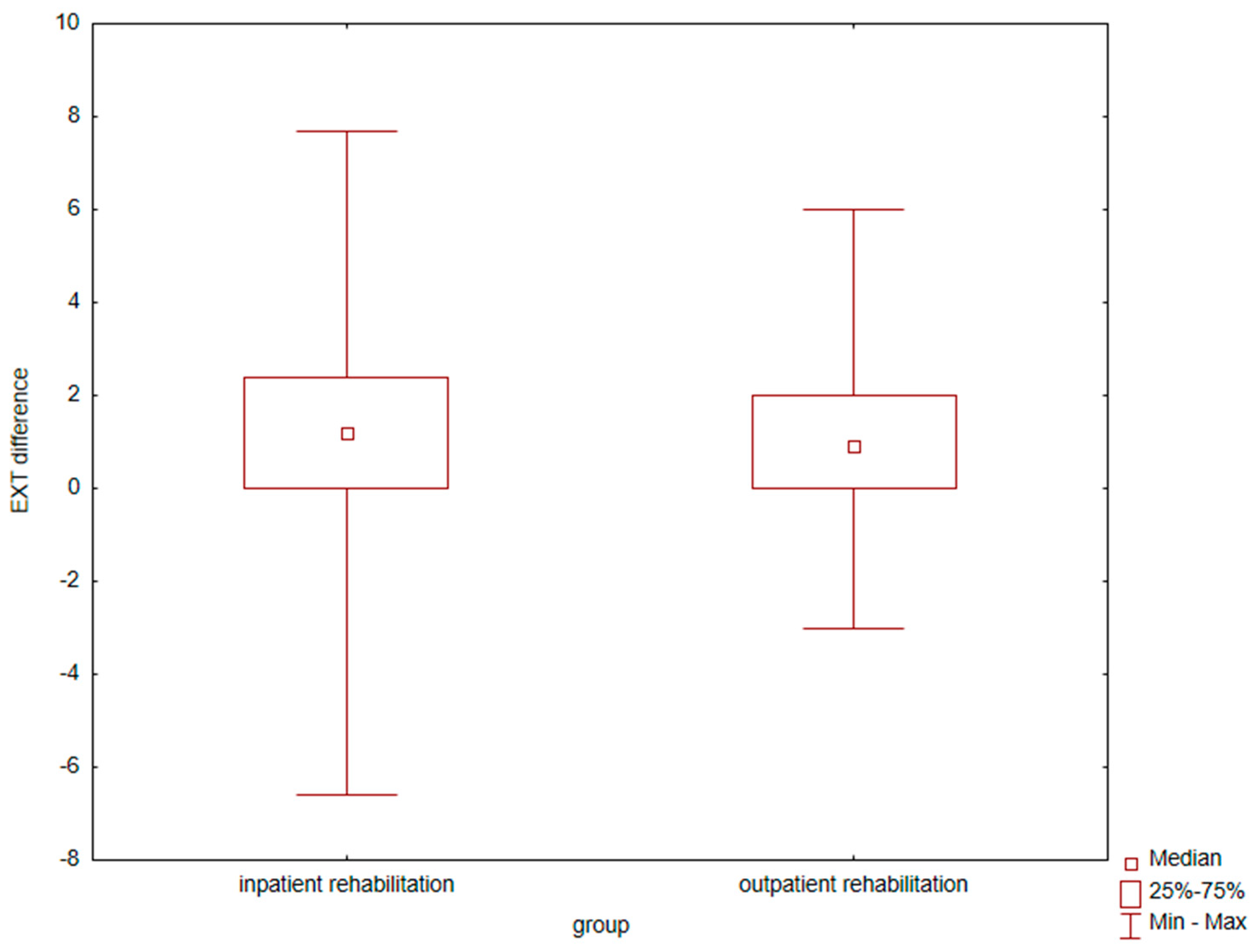

The result of the comparison of the increase in exercise capacity expressed in METs in the final exercise test as compared to the initial test and a comparison of these differences between the groups of patients from the centre-based group and those participating in telerehabilitation indicate no significant difference, as presented in

Figure 1.

During the telerehabilitation of patients from the study group, adverse events occurred, presented in

Table 4. However, they did not ultimately affect the deterioration of the final results of rehabilitation in terms of exercise capacity. They did not require interruption of the rehabilitation process and they disappeared when the pharmacotherapy used was modified or when new drugs were introduced.[

2]

4. Discussion

The most important result of our work has been to show that there is no statistically significant difference in the improvement of exercise capacity between the group of patients participating in cardiac telerehabilitation and the group of patients participating in inpatient rehabilitation at the centre as assessed by an electrocardiographic exercise test performed according to the Bruce-Ramp protocol. This study also answers the question often asked by patients before they start cardiac telerehabilitation, which is: what will be the probable result of the improvement in exercise capacity after the completion of the rehabilitation programme and whether it will be similar to what they would obtain by participating in inpatient cardiac rehabilitation.

Studies conducted to date indicate that during cardiac rehabilitation patients improve their exercise capacity by an average of 1,5 METs [

3]. Uznańska-Loch et al. [

4] showed in their study that the highest probability of achieving the maximum improvement in exercise tolerance after cardiac rehabilitation is associated with the co-occurrence of left ventricular ejection fraction of >43% and a result of ≤8.4 METs in the initial exercise test. Significant differences in the results occur in patients with normal and with reduced ejection fractions [

5]. Heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction is a strong predictor of mortality after ACS on admission. Differences in the results achieved during cardiac rehabilitation are also related to gender [

6]. Women achieve less improvement during cardiac rehabilitation, which can be explained by the higher age of the female population with ACS and with worse clinical results upon admission to the rehabilitation programme. The conclusion from the study by A. Bielecka-Dabrowa et al. (the aim of which was to implement a health care model for patients with heart failure (HF) and to assess clinical and psychosocial differences between women and men in the study population) provides information that women suffer from HF symptoms more often and have a worse quality of life as assessed by the EQ-5D-5L than men despite a better left ventricular ejection fraction [

7].

Most studies conducted by other centres provide results similar to ours – cardiac telerehabilitation brings comparable results to centre-based cardiac rehabilitation in terms of exercise capacity and quality of life.

The study by Piotrowicz et al. [

8], conducted, however, before the pandemic, included 152 patients with heart failure, mean age 58,1±10,2 years, NYHA class II and III, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%. Patients were randomised to home-based cardiac rehabilitation with ECG telemonitoring (n = 77) or to outpatient standard cardiac rehabilitation (n = 75). All the patients completed 8 weeks of cardiac rehabilitation. Both groups were comparable in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics and pharmacotherapy. The effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation was assessed on the basis of changes in the NYHA class, peak oxygen consumption during exercise ergospirometry, the distance covered during a 6-minute walk test, and the score on the SF-36 questionnaire. Cardiac rehabilitation resulted in significant improvement in all the above-mentioned parameters both in the standard cardiac rehabilitation group and in the cardiac telerehabilitation group.

Another study confirming the good effects of telerehabilitation is the study by Avila A et al. [

9], in which 90 patients with coronary artery disease (80 men) were randomly assigned to 3 months of home rehabilitation (30), centre-based rehabilitation (30) or the control group not undergoing rehabilitation (30) at the ratio of 1:1:1. Rehabilitation based on exercising at home proved to be as effective as centre-based rehabilitation and did not result in a lower level of final exercise capacity and exercise activity in comparison with the other two groups.

In another study, Bernocchi et al. [

10] evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of an integrated home telerehabilitation programme (Telereab-HBP), which lasted 4 months, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) concomitant with chronic heart failure (CHF). As far as their methodology is concerned, as the primary endpoint they used the result of the six-minute walk test (6MWT), and the secondary endpoints were time to the event (hospitalization and death), dyspnea, exercise activity profile, disability, and quality of life. The Telereab-HBP programme included a remote monitoring of cardiorespiratory parameters, weekly telephone calls with a nurse, and an exercise programme monitored weekly by a physiotherapist. All the results were re-evaluated after a 2-month period without intervention. A total of 112 patients were randomised, 56 in each group. Their mean age ±SD was 70±9 years, and 82.1% of the study participants were men. Incidentally, the gender distribution was similar in our study: 82% of the patients participating in telerehabilitation were men, while among the patients participating in inpatient rehabilitation the percentage of men was 72. The study by Bernocchi et al. showed that after 4 months of the rehabilitation programme, the walking distance of the patients in the study group increased in comparison with their initial distance, which allowed the authors to conclude that the 4-month rehabilitation programme with a remote monitoring of cardiorespiratory parameters and with telephone consultations with a nurse and a physiotherapist was feasible and effective in the group of older patients with COPD and CHF.

In the study by Kraal et al. [

11] 90 patients at a low or moderate cardiovascular risk, who were starting cardiac rehabilitation, were randomised to 3 months of home-based training with telemonitoring advice or to in-centre training. Physical fitness improved significantly at discharge and at 1-year follow-up (p < 0.01) in both groups, with no significant differences between the two groups. The levels of exercise activity did not change significantly during the 1-year follow-up. The health care costs were numerically lower in the "home" group, but this difference was not statistically significant. The authors of that study reached similar conclusions to the ones that we present in our article; telerehabilitation yielded equally good results as in-hospital cardiac rehabilitation. Although adherence to the training recommendations was similar in both groups, satisfaction with the rehabilitation programme was higher in the home-based group. Although in our study we did not conduct a survey on the degree of satisfaction with the form of rehabilitation, no patient reported any problems with operating the telerehabilitation equipment or barriers related to this form of training.

The randomised study by Bravo-Escobar et al. [

12] included 28 patients with stable coronary artery disease at a moderate cardiovascular risk. Of these, 14 were assigned to a traditional hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation program (the control group) and 14 were assigned to a home-based mixed-supervision program (the study group). The mean BMI values and the mean age of the patients were similar to those in our study, and similarly to our study, the mean age of the home-based group was slightly higher than the mean age of the hospital-based group. There were no significant differences between the traditional cardiac rehabilitation group and the home-based mixed-supervision group in terms of exercise time and METS achieved during the exercise test and the recovery index in the first minute (which increased in both groups after CR).

An interesting modern method for monitoring the course of telerehabilitation is the use of smartwatches by patients described by Mitropoulos et al. [

13] A randomised trial was designed to assess the effects of real-time monitoring of cardiac telerehabilitation using smartwatches in people who had recently had a myocardial infarction. All the patients completed baseline and follow-up measurements after 24 weeks, which assessed peak oxygen uptake, the mean daily step count, distance, and calories. The online group showed similar improvements in the mean daily step count and the mean daily walking distance after 24 weeks as the gym-based exercise group. There were no adverse events related to exercise during the study. The results of the study indicate that a real-time spurvised exercise programme of cardiac rehabilitation using smartwatch technology to monitor the haemodynamic response in patients with coronary artery disease and after a myocardial infarction is as effective as the gym-based exercise programme.

Researchers compared also the effectiveness of outpatient hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation and telerehabilitation in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery. [

14] Similarly to our study, the mean age of patients in the “home group” was slightly higher than the mean age of patients in the “hospital group”. Measurements included the results of the incremental shuttle walk test (ISWT), psychosocial test scores, and body composition recorded at baseline, eight weeks after the intervention, and after a four-week follow-up. After the intervention, there was an increase in the duration of ISWT from baseline in both the home-based and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation groups. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation was as effective as outpatient hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation in improving exercise capacity in patients after CABG surgery. Moreover, home-based cardiac rehabilitation seemed to be more effective in maintaining this improvement in the long run.

Interesting results are presented in the study by Gu et al. [

15]. They analyzed a cohort of stable patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) who had undergone percutaneous coronary angioplasty and who participated in two different modes of the cardiac rehabilitation programme after being discharged from hospital; CR took place in two periods: from January 2019 to December 2019 (inpatient CR) and from May 2020 to May 2021 (remote CR). Exercise capacity was assessed using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), oxygen uptake at peak exercise (VO2max), and anaerobic respiratory threshold (VO2AT) before discharge, after 8 weeks of CR and after 12 weeks of CR, performed either in the centre or remotely at home. No adverse events occurred during the programme. Patients from both groups increased their walking distance in the 6MWT test with higher VO2max after 8 and 12 weeks. The patients participating in telerehabilitation showed better results in terms of anxiety and depression levels in comparison with the patients from inpatient rehabilitation.

The limitation of our work is the small size of the study group, but this group comes from a unique period during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the only form of cardiac rehabilitation for patients after a myocardial infarction was telerehabilitation. Gathering a similar group of patients in the current period – outside the period of restrictions related to the pandemic – would be impossible owing to the fact that currently patients and doctors have a choice between three forms of cardiac rehabilitation – inpatient rehabilitation, outpatient rehabilitation in the centre and telerehabilitation (outside the centre).

5. Conclusions

In our centre, telerehabilitation after acute coronary syndrome, performed during the COVID-19 pandemic guaranteed an equally good improvement in exercise capacity as that observed in patients undergoing inpatient rehabilitation, regardless of the difference in the age profile of the compared groups. These results, compared with studies from different centers and from different periods, encourage the popularization of the mode of cardiac rehabilitation based on the remote monitoring of ECG, arterial blood pressure and body mass.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R. and B.B.; methodology, T.R.; software, J.W.; validation, J.W., and B.B.; formal analysis, T.R.; investigation, E.W.; resources, U.C-G.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.; writing—review and editing, T.R.; visualization, B.B.; supervision, JD.K.; project administration, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature and the use of patient data for which consent is not required as in experimental studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Janusz Wróblewski, for his linguistic help with the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jegier, A.; Szalewska, D.; Mawlichanów, A.; et al. Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation as the keystone in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Kardiol Pol 2021, 79, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bralewska, B.; Wykrota, J.; Kurpesa, M.; Kasprzak, J.D.; Cieślik-Guerra, U.; Wądołowska, E.; Rechciński, T. Analysis of adverse events during a cardiac telerehabilitation program: A single-center study. Kardiol Pol. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Haniyeh, A.; Shah, N.P.; Wu, Y.; Cho, L.; Ahmed, H.M. Predictors of cardiorespiratory fitness improvement in phase II cardiac rehabilitation. Clin Cardiol. 2018, 41, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uznańska-Loch, B.; Wądołowska, E.; Wierzbowska-Drabik, K.; Cieślik-Guerra, U.; Kasprzak, J.D.; Kurpesa, M.; Rechciński, T. Left ventricular systolic function and initial exercise capacity—their importance for results of cardiac rehabilitation after acute coronary syndrome. Explor Cardiol. 2023, 1, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelshtein Brezinov Olga, M.D.; Klempfner Robert, M.D.; Zekry Sagit Ben, M.D.; Goldenberg Ilan, M.D.; Kuperstein Rafael, M.D. Prognostic value of ejection fraction in patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome: A real world study. Medicine 2017, 96, e6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feola, M.; Garnero, S.; Daniele, B.; Mento, C.; Dell'Aira, F.; Chizzolini, G.; Testa, M. Gender differences in the efficacy of cardiovascular rehabilitation in patients after cardiac surgery procedures. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015, 12, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bielecka-Dąbrowa, A.; Trzmielak, D.; Sakowicz, A.; Janikowski, K.; Banach, M. Gender differences in efficiency of the telemedicine care of heart failure patients. The results from the TeleEduCare-HF study. Archives of Medical Science. 2024, 20, 1797–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Baranowski, R.; Bilinska, M.; et al. A new model of home-based telemonitored cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure: effectiveness, quality of life, and adherence. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, A.; Claes, J.; Buys, R.; et al. Home-based exercise with telemonitoring guidance in patients with coronary artery disease: Does it improve long-term physical fitness? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020, 27, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernocchi, P.; Vitacca, M.; La Rovere, M.T.; et al. Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2018, 47, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraal, J.J.; Van den Akker-Van Marle, M.E.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Stut, W.; Peek, N.; Kemps, H.M. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of home-based cardiac rehabilitation compared to conventional, centre-based cardiac rehabilitation: Results of the FIT@Home study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bravo-Escobar, R.; González-Represas, A.; Gómez-González, A.M.; Montiel-Trujillo, A.; Aguilar-Jimenez, R.; Carrasco-Ruíz, R.; Salinas-Sánchez, P. Effectiveness and safety of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme of mixed surveillance in patients with ischemic heart disease at moderate cardiovascular risk: A randomised, controlled clinical trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitropoulos, A.; Anifanti, M.; Koukouvou, G.; Ntovoli, A.; Alexandris, K.; Kouidi, E. Exploring the effects of real-time online cardiac telerehabilitation using wearable devices compared to gym-based cardiac exercise in people with a recent myocardial infarction: a randomised controlled trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 11, 1410616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- M Taktoni, M T Morg Thow, C S Seenan, Coronary Artery ByPass Population , A randomized controlled trial of an eight-week cardiac rehabilitation home versus hospital exercise programme for post coronary cardiac bypass patients, European Heart Journal, Volume 45, Issue Supplement_1, October 2024, ehae666.1443. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Tong, X.; Meng, S.; Xu, S.; Huang, J. Remote cardiac rehabilitation program during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with stable coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2023, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).