1. Introduction

The U.S. Department of Defense is executing three of the most consequential cybersecurity transformations in its history. The National Security Agency’s Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0) mandates migration to quantum-resistant cryptography, with software and firmware signing required by 2025 and exclusive use of PQC algorithms by 2030–2035 [

1,

2]. The DoD Zero Trust Strategy requires Target Level implementation across all DoD Information Networks by September 30, 2027 (end of FY2027), encompassing 152 activities across seven pillars [

3,

4]. Simultaneously, the Chief Digital and AI Office (CDAO) is deploying Responsible AI frameworks, AI assurance toolkits, and governance mechanisms for an expanding portfolio of AI-enabled capabilities [

5,

6].

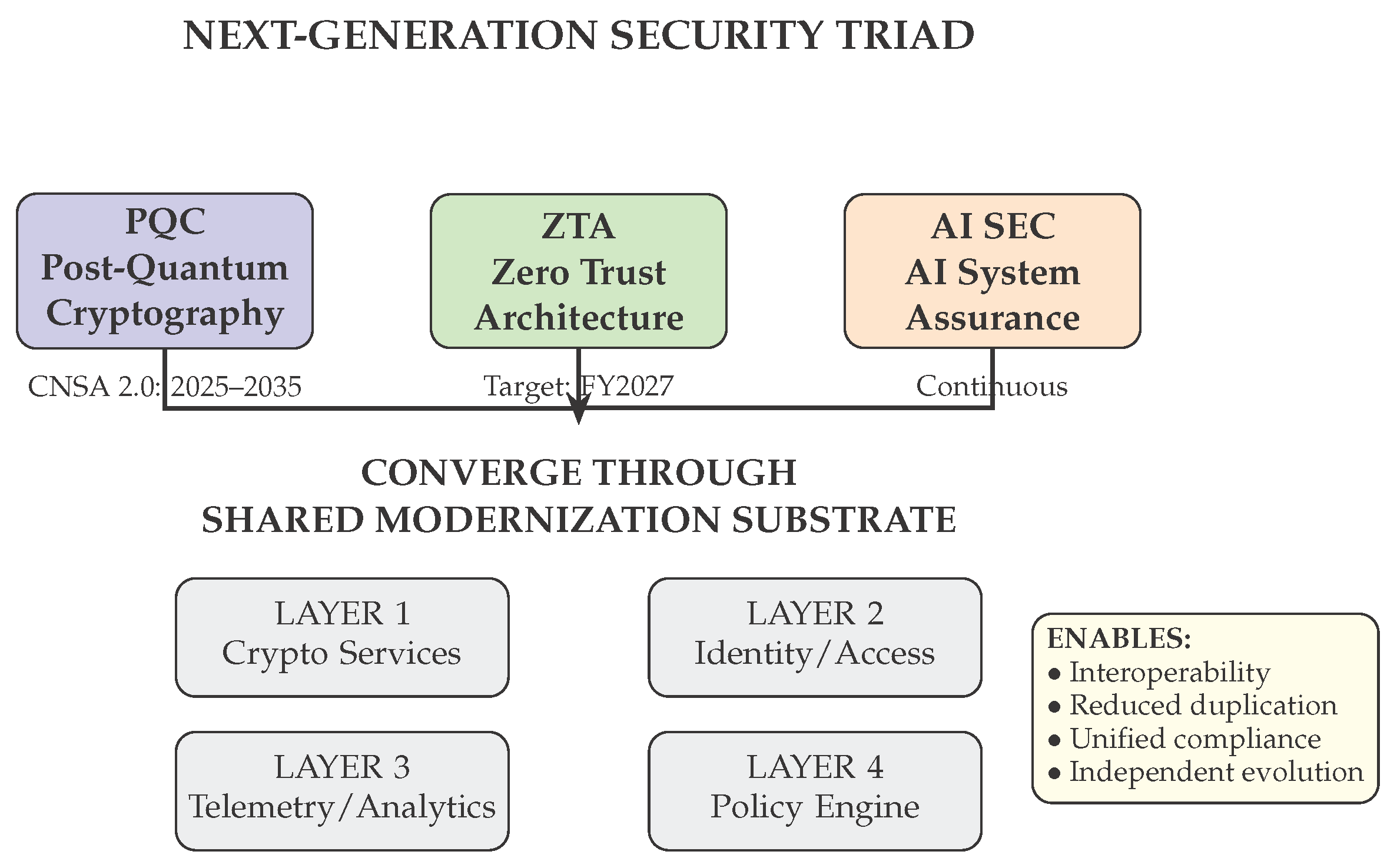

Together, these three initiatives constitute what we term the

Next-Generation Security Triad (see

Figure 1). Just as the traditional CIA Triad (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability) provides the foundational framework for information security, the Next-Generation Security Triad—PQC, ZTA, and AI Security—provides the foundational framework for defending DoD systems against 21st-century threats: quantum-equipped adversaries, sophisticated persistent threat actors operating inside network perimeters, and adversarial manipulation of AI-enabled capabilities.

The Triad components share a common objective—securing DoD systems against current and emerging threats—yet they are managed as independent programs with separate governance structures, budget lines, skill requirements, and compliance pathways. This fragmentation creates acute challenges for the personnel responsible for implementation:

CIOs must reconcile competing modernization roadmaps across enterprise architecture decisions.

Commanding Officers face operational continuity risks when multiple security upgrades affect the same systems.

PMOs struggle to sequence acquisitions when Triad requirements create interdependencies.

Authorizing Officials lack consolidated frameworks for assessing risk across all three Triad domains simultaneously.

The conventional response—merge the programs—is impractical. Each Triad component addresses fundamentally different threat models, requires distinct technical expertise, and operates under separate statutory and policy authorities. PQC migration is a cryptographic infrastructure problem; ZTA is an access control and network architecture problem; AI security is a model integrity and adversarial robustness problem.

This paper proposes an alternative: establish a shared modernization substrate—a common technical foundation that all three Triad components build upon. Rather than forcing convergence at the program level, we enable integration at the infrastructure level. Each Triad component retains its governance, timeline, and specialized focus while leveraging shared services that ensure interoperability, reduce duplication, and provide unified compliance visibility.

The contributions of this paper are: (1) the conceptualization of the Next-Generation Security Triad as a unified framework for DoD cyber modernization; (2) a systematic analysis of timeline conflicts and interdependencies across Triad components; (3) a four-layer substrate architecture that enables coordinated modernization without program merger; (4) a maturity model for measuring Triad convergence progress; and (5) validated application scenarios for representative DoD environments.

2. Background: The Next-Generation Security Triad

The traditional CIA Triad has served as the foundational model for information security for decades. However, the threat landscape facing DoD has evolved beyond what the CIA Triad alone can address. Quantum computing threatens the mathematical foundations of current cryptography (challenging Confidentiality). Sophisticated adversaries operating inside network perimeters undermine perimeter-based trust models (challenging Integrity assumptions). Adversarial machine learning attacks manipulate AI system outputs (challenging the Availability and reliability of AI-enabled capabilities). The Next-Generation Security Triad addresses these evolved threats through three complementary programs.

2.1. Triad Component 1: Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC)

The threat model driving PQC migration is “harvest now, decrypt later” (HNDL), also referred to as “store now, decrypt later” (SNDL), wherein adversaries capture encrypted data today for decryption once cryptographically relevant quantum computers (CRQCs) become available [

7]. The Cloud Security Alliance estimates that a CRQC may be capable of breaking current public-key infrastructure by approximately April 2030, though this projection remains subject to uncertainty given the pace of quantum computing advances [

8].

NSA’s CNSA 2.0 provides a phased transition timeline (see

Table 1) [

1,

2].

NIST finalized three PQC standards in August 2024: ML-KEM (FIPS 203) for key encapsulation, ML-DSA (FIPS 204) for digital signatures, and SLH-DSA (FIPS 205) for stateless hash-based signatures [

9]. A fourth standard, FN-DSA (draft FIPS 206), based on the FALCON algorithm, had its draft submitted for approval in August 2025, with finalization expected in late 2026 or early 2027. DoD implementations must achieve NIAP validation and comply with CNSSP 15 requirements [

10]. Critical implementation challenges include larger key sizes (ML-KEM-1024 public encapsulation keys are 1,568 bytes versus 256 bytes for RSA-2048 public keys), increased computational overhead, and protocol modifications required for standards like IKEv2 and TLS [

11].

During the transition period (2025–2030), systems will likely operate in hybrid mode, performing both a classical ECDH key exchange and a post-quantum ML-KEM encapsulation, then combining the derived keys to produce a session secret. This “belt and suspenders” approach ensures that even if the new PQC algorithms harbor an undiscovered flaw, classical security guarantees remain intact.

2.2. Triad Component 2: Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA)

The DoD Zero Trust Strategy, released in October 2022, mandates enterprise-wide Target Level ZTA by September 30, 2027 (end of FY2027), with Advanced Level capabilities by 2032 [

3]. The strategy encompasses seven pillars: User, Device, Network/Environment, Application & Workload, Data, Visibility & Analytics, and Automation & Orchestration [

4]. Implementation requires completion of 91 Target Level activities and 61 Advanced Level activities across these pillars [

12].

DTM 25-003, effective July 17, 2025, established the Chief Zero Trust Officer position and formalized governance through the DoD ZT Executive Committee [

13]. Key dependencies include: (a) Cryptographic agility—ZTA encryption requirements assume underlying cryptographic infrastructure can be updated without architectural redesign; (b) Identity infrastructure—continuous verification depends on robust ICAM services, with DoD PKI servicing approximately 4.5 million users as of 2020 [

14]; (c) Telemetry pipeline—trust scoring requires reliable collection and analysis of behavioral and contextual signals; and (d) Legacy modernization—many systems cannot support ZTA controls without infrastructure upgrades.

Without PQC integration, ZTA remains vulnerable to future quantum attacks against its cryptographic foundations. Without AI Security integration, AI-augmented trust engines introduce new attack surfaces.

2.3. Triad Component 3: AI Security and Assurance

AI systems introduce fundamentally different attack surfaces from traditional cybersecurity threats. NIST AI 100-2e2025, published March 24, 2025, provides a comprehensive taxonomy of adversarial machine learning (AML) attacks including: training-time attacks (data poisoning, model poisoning, backdoor insertion); deployment-time attacks (evasion attacks, adversarial examples, model inversion); privacy attacks (membership inference, training data reconstruction); and supply chain attacks (compromised pre-trained models, malicious code in ML libraries) [

15,

16].

CDAO released the Responsible AI Toolkit in 2024, operationalizing DoD’s AI Ethical Principles and providing assessment frameworks aligned with NIST AI RMF [

5,

6]. The AI Rapid Capabilities Cell (AI RCC), announced in December 2024, is deploying

$100M in FY2024–2025 for generative AI pilots across 15 warfighting and enterprise use cases [

17].

2.4. The Triad Synchronization Problem

The three Triad components create a complex web of dependencies and timeline conflicts (see

Table 2).

Current DoD IT/Cyberspace Activities funding for FY2025 is

$64.1 billion—approximately 7.5% of the total DoD budget [

18]. GAO has documented persistent challenges with DoD IT modernization programs, with planned spending of

$10.9 billion on 24 major IT business systems during FY2023-2025, experiencing significant cost overruns and schedule delays [

19].

The literature addresses each Triad component independently: PQC migration planning [

7,

20], ZTA reference architectures [

21,

22], and AI robustness frameworks [

15,

23]. No existing framework provides a synchronized modernization strategy that enables coordinated execution across all three Triad components. This paper addresses that gap.

3. Methods: The Shared Modernization Substrate

3.1. Design Principles

The substrate approach is grounded in three design principles: (1) Separation of concerns—each Triad component (PQC, ZTA, AI Security) retains its governance, timeline, budget authority, and specialized focus, with the substrate providing shared infrastructure services rather than program integration; (2) Interface standardization—Triad components interact with the substrate through well-defined APIs and service interfaces, enabling independent evolution while ensuring interoperability; and (3) Capability composability—substrate services can be consumed independently or in combination, allowing incremental adoption aligned with each Triad component’s maturity.

3.2. Four-Layer Substrate Architecture

The shared modernization substrate comprises four infrastructure layers that collectively enable Triad integration (see

Figure 1):

Layer 1: Cryptographic Services Infrastructure (CSI). The CSI layer provides enterprise-wide cryptographic services that support both current (CNSA 1.0) and quantum-resistant (CNSA 2.0) algorithms through a crypto-agility framework. Core capabilities include: cryptographic inventory management; algorithm abstraction layer enabling software-defined cryptography [

24]; HSM/KMS integration for unified key management [

25]; and certificate lifecycle services for PQC-capable PKI.

Layer 2: Identity and Access Management Fabric (IAMF). The IAMF layer provides unified identity services for both person entities (PE) and non-person entities (NPE), extending the DoD ICAM Reference Design [

14,

26]. Core capabilities include: unified identity repository; credential services for PQC-ready credential issuance; authentication services with AAL3-capable authentication [

27]; and authorization services with attribute-based access control (ABAC).

Layer 3: Telemetry and Analytics Pipeline (TAP). The TAP layer provides unified collection, aggregation, and analysis of security telemetry across the enterprise. Core capabilities include: unified log aggregation; behavioral analytics with ML-based anomaly detection; threat intelligence integration; and compliance telemetry.

Layer 4: Policy Orchestration Engine (POE). The POE layer provides unified policy definition, distribution, and enforcement across all substrate layers, extending the standard ZTA architecture of decoupled Policy Decision Points (PDPs) and Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs) as defined in NIST SP 800-207 [

21]. Core capabilities include: policy-as-code; distributed policy enforcement; cross-domain policy coordination; and compliance mapping.

3.3. Triad-Substrate Integration Points

The four substrate layers create natural integration points where Triad components converge (see

Table 3).

3.4. Triad Convergence Maturity Model

We introduce a five-level maturity model to provide DoD Components with a measurable path toward unified Triad implementation (see

Table 4).

4. Results: Application Scenarios

4.1. Triad Application to UAV and Autonomous Systems

Unmanned aerial vehicles present a concentrated Triad integration challenge: resource-constrained environments requiring all three security capabilities. Substrate application includes: CSI—PQC-secured command-and-control links using ML-KEM, PQC-signed firmware and mission software; IAMF—machine identity for UAV platform, ground control station authentication; TAP—onboard anomaly detection for command injection, behavioral monitoring of navigation AI; and POE—enforcement of geofencing constraints, AI model deployment gates.

4.2. Triad Application to DoD Enterprise Environment

Enterprise networks represent the largest attack surface and require coordinated Triad modernization across thousands of systems. Substrate application includes: CSI—enterprise PKI transition to hybrid certificates, VPN migration to PQC-capable protocols; IAMF—integration with myAuth (DMDC’s next-generation identity system [

27]); TAP—SIEM integration for unified security monitoring; and POE—Zero Trust policy enforcement points.

4.3. Triad Application to Tactical Edge Environments

Tactical environments present unique Triad challenges: intermittent connectivity, austere computing resources, and contested electromagnetic spectrum—the Disconnected, Intermittent, Low-bandwidth (DIL) conditions that characterize forward-deployed operations. Substrate adaptation includes pre-positioned PQC key material, disconnected authentication with cached credentials, and mission-tailored policy sets.

4.4. Governance and Workforce Requirements

DoD Cyber Workforce Framework (DCWF) and NICE roles can be mapped to Triad-substrate competencies (see

Table 5) [

28].

4.5. Triad Integration with JADC2

The Next-Generation Security Triad and its shared substrate align with Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) objectives for secure, interoperable data sharing across military services and mission partners [

29,

30]. GAO’s April 2025 assessment of CJADC2 identified the lack of a comprehensive framework to guide investments and track progress as a critical gap [

31]. The Triad maturity model provides such a framework for the cybersecurity dimensions of JADC2 implementation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The Next-Generation Security Triad—PQC, ZTA, and AI Security—represents the three pillars of DoD’s 21st-century cyber posture. Today, these Triad efforts remain siloed, managed by different offices, funded through different budget lines, measured against different compliance frameworks, and staffed by personnel with different skill sets. This fragmentation creates risk: systems modernized for ZTA compliance may not be crypto-agile; AI systems deployed for operational advantage may lack assurance mechanisms; PQC migration may proceed without consideration for the AI and ZTA systems that depend on cryptographic infrastructure.

The solution is not to merge Triad programs—their distinct technical requirements and policy authorities make merger impractical. The solution is to establish a shared modernization substrate that enables each Triad component to proceed according to its own timeline while ensuring architectural coherence and reducing duplicative infrastructure investment.

5.1. Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the Triad framework has not been validated through operational deployment; future work should include pilot implementations within representative DoD Components. Second, the maturity model requires calibration against real-world program data to establish appropriate thresholds and metrics. Third, the substrate architecture assumes a degree of enterprise IT governance that may not exist uniformly across all DoD organizations. Fourth, the paper does not address the budget and acquisition pathway for substrate infrastructure development. Fifth, the significant talent shortage across all three Triad domains—documented in GAO’s 2025 High Risk assessment [

32]—presents an implementation challenge that governance structures alone cannot resolve. Sixth, international interoperability considerations warrant further analysis; coalition partners may operate under different PQC migration timelines, ZTA maturity levels, and AI governance frameworks.

5.2. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents the first unified framework for conceptualizing and synchronizing DoD’s three major cyber modernization initiatives as a coherent Next-Generation Security Triad. The four-layer substrate architecture (CSI, IAMF, TAP, POE) provides concrete integration points. The five-level maturity model provides a measurable path forward. The governance, workforce, and procurement recommendations provide implementation guidance tailored to DoD organizational structures.

Future research directions include: formal verification of Triad-substrate security properties under combined threat models; performance optimization of PQC algorithms for tactical edge deployment; extension of Triad architecture to coalition partner environments; continuous red-team evaluation incorporating adversarial ML, quantum cryptanalysis, and ZTA bypass techniques; quantitative analysis of cost savings from Triad-substrate modernization versus siloed approaches; and development of training curricula for cross-domain Triad competencies.

A synchronized approach to the Next-Generation Security Triad, built on shared infrastructure, is essential to secure DoD missions against the converging threats of quantum-equipped adversaries, sophisticated cyber actors, and adversarial AI. The Triad-substrate framework presented here provides a practical path toward that objective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.; methodology, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges colleagues in the DoD post-quantum cryptography, Zero Trust, and AI security communities whose discussions informed this framework.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABAC |

Attribute-Based Access Control |

| AML |

Adversarial Machine Learning |

| CDAO |

Chief Digital and AI Office |

| CIA |

Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability |

| CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

| CNSA |

Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite |

| CRQC |

Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer |

| CSI |

Cryptographic Services Infrastructure |

| DIL |

Disconnected, Intermittent, Low-bandwidth |

| DoD |

Department of Defense |

| HNDL |

Harvest Now, Decrypt Later |

| HSM |

Hardware Security Module |

| IAMF |

Identity and Access Management Fabric |

| ICAM |

Identity, Credential, and Access Management |

| JADC2 |

Joint All-Domain Command and Control |

| ML-DSA |

Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Algorithm |

| ML-KEM |

Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NSA |

National Security Agency |

| PDP |

Policy Decision Point |

| PEP |

Policy Enforcement Point |

| PKI |

Public Key Infrastructure |

| PMO |

Program Management Office |

| POE |

Policy Orchestration Engine |

| PQC |

Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| TAP |

Telemetry and Analytics Pipeline |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| ZTA |

Zero Trust Architecture |

References

- National Security Agency. Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0). NSA Cybersecurity Advisory; NSA: Fort Meade, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Security Agency. The Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 and Quantum Computing FAQ, Version 2.1; NSA: Fort Meade, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. Department of Defense Zero Trust Strategy; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Zero Trust Capability Execution Roadmap, Version 1.1; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office. Responsible AI Strategy and Implementation Pathway; CDAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office. Responsible AI Toolkit. Available online: https://www.ai.mil (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y.-K.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Smith-Tone, D. Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography. NIST Internal Report 8105. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016.

- Cloud Security Alliance. Quantum Computing and Cryptography: The Impact and the Opportunity; CSA: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard (FIPS 203), Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard (FIPS 204), Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard (FIPS 205); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on National Security Systems. Use of Public Standards for Secure Information Sharing (CNSSP 15); CNSS: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kivinen, T.; Snyder, J. Post-quantum Hybrid Key Exchange with ML-KEM in IKEv2. IETF Draft, 2024.

- General Services Administration. DoD Zero Trust Strategy Buyer’s Guide, Version 1.4; GSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. DTM 25-003: Implementing the DoD Zero Trust Strategy. DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Identity, Credential, and Access Management Strategy; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev, A.; Oprea, A.; Fordyce, A.; Anderson, H.; Davies, X.; Hamin, M. Adversarial Machine Learning: A Taxonomy and Terminology of Attacks and Mitigations. NIST AI 100-2e2025; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Identifies Types of Cyberattacks That Manipulate Behavior of AI Systems. NIST News, 4 January 2024.

- Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office. Artificial Intelligence Rapid Capabilities Cell Announcement; CDAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Estimates: IT/Cyberspace Activities Overview; DoD Comptroller: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. DOD Efforts to Buy and Maintain IT Systems Are Billions Over Budget. GAO Blog; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, D.; Alagic, G.; Apon, D.; et al. Status Report on the Third Round of the NIST PQC Standardization. NIST IR 8413-upd1; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022.

- Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; Mitchell, S.; Connelly, S. Zero Trust Architecture. NIST SP 800-207; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Zero Trust Maturity Model, Version 2.0; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Wild Patterns: Ten Years After the Rise of Adversarial Machine Learning. Pattern Recognition 2018, 84, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Yoon, H.; Lee, C.; Kim, E.; Ahn, J.; Yu, H. Software-Defined Cryptography: A Design Feature of Cryptographic Agility. arXiv 2024, 2404.01808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryptomathic. Cryptographic Key Management in 2025 and Beyond. Cryptomathic White Paper, 2025.

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Enterprise ICAM Reference Design; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peraton. Peraton Helps DMDC Launch Next-Generation Identity Management System (myAuth). Peraton News, 27 August 2025.

- Department of Defense. DoD Cyber Workforce Framework (DCWF); DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) Strategy; DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) Initial Capabilities Document; DoD Joint Staff: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Defense Command and Control: Further Progress Hinges on Framework. GAO-25-106454; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More. GAO-25-108125; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).