Submitted:

06 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

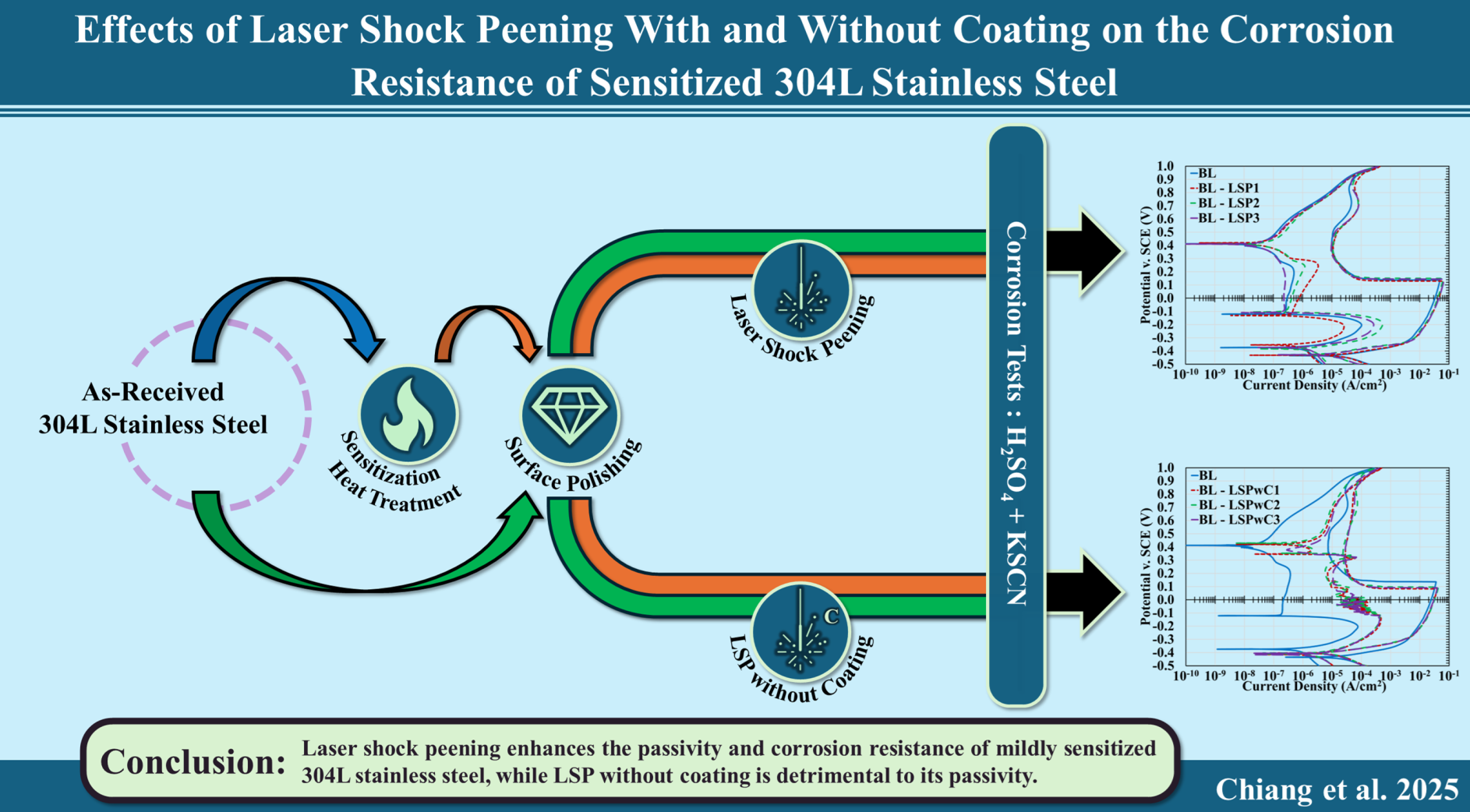

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.3. Laser Shock Peening

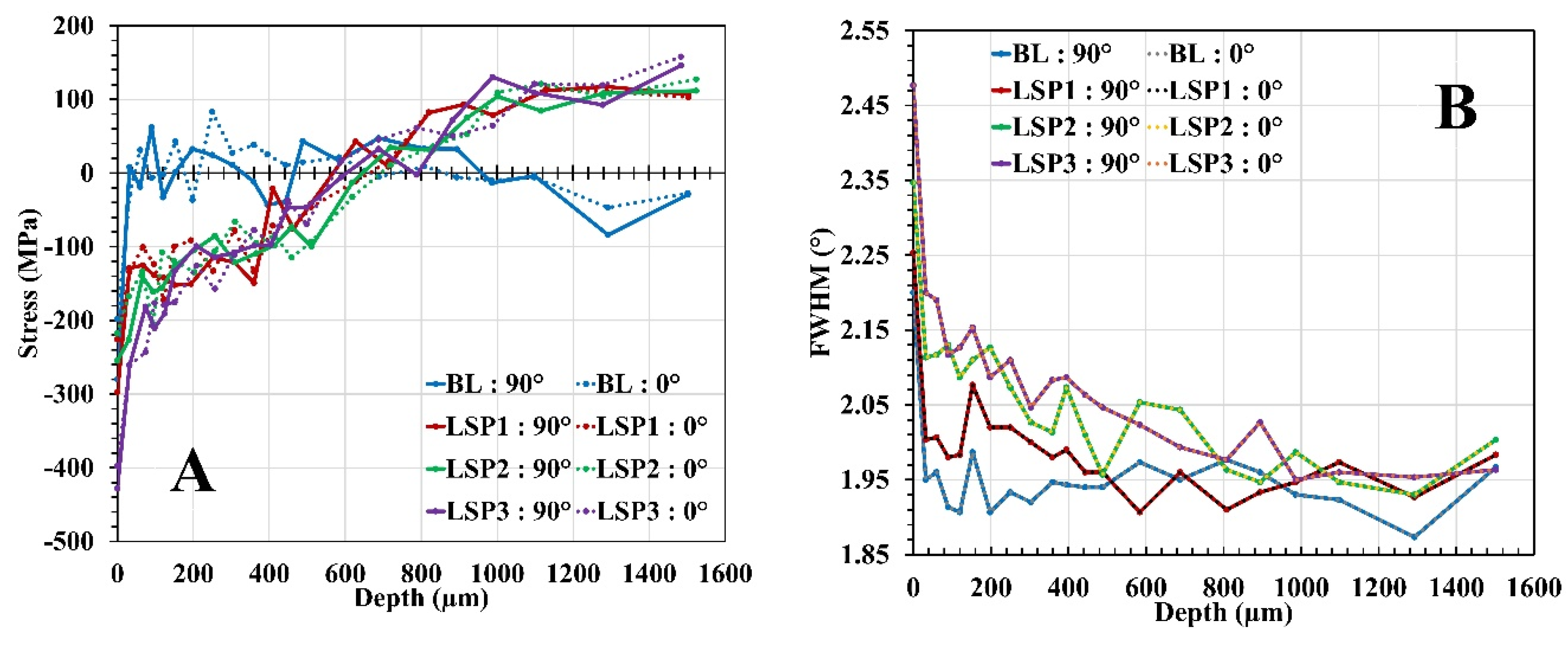

2.4. Residaul Stress Depth Profile

2.5. Cyclic Polarization Test

2.6. Surface Optical Profile

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

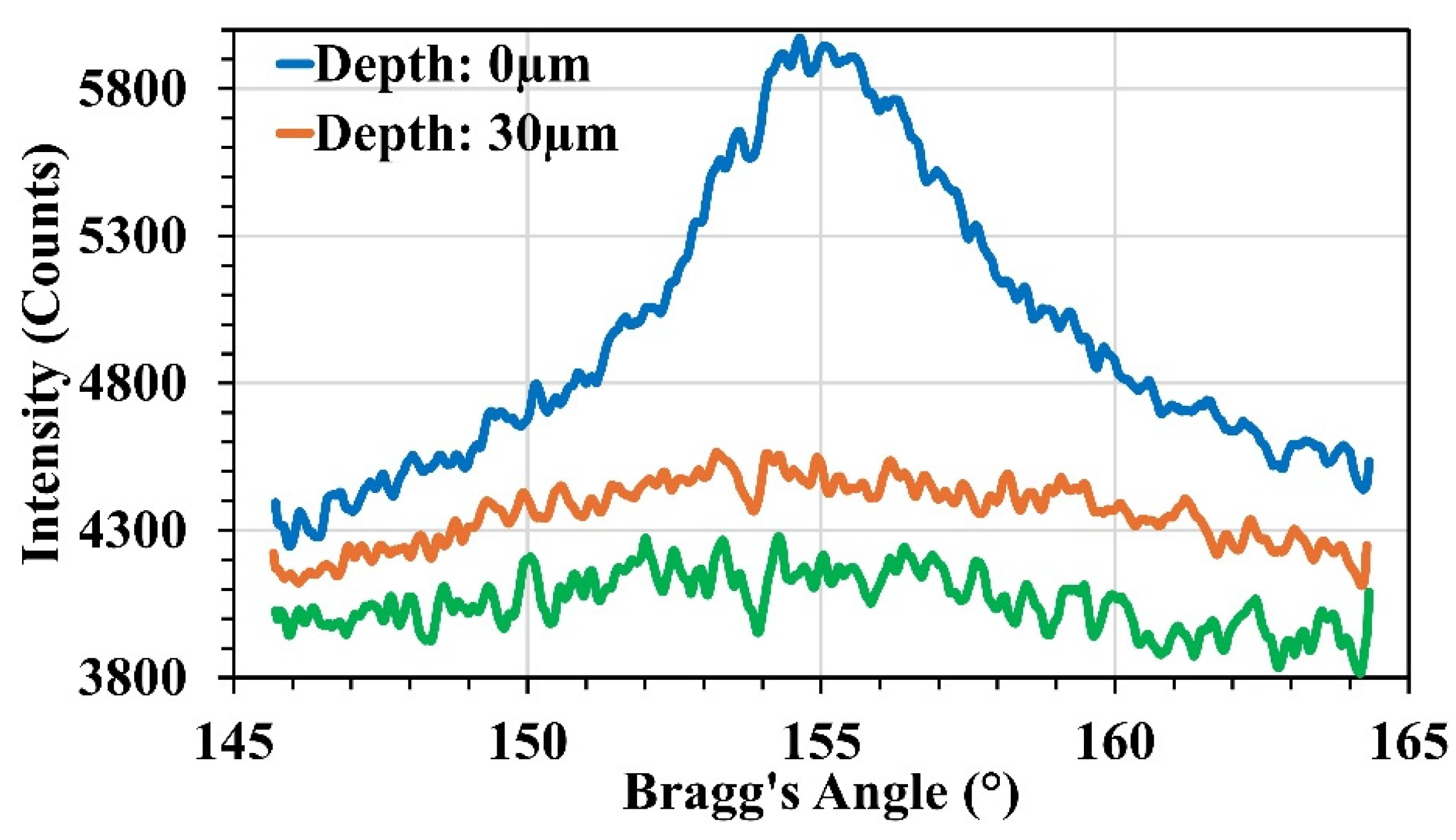

2.8. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3. Results

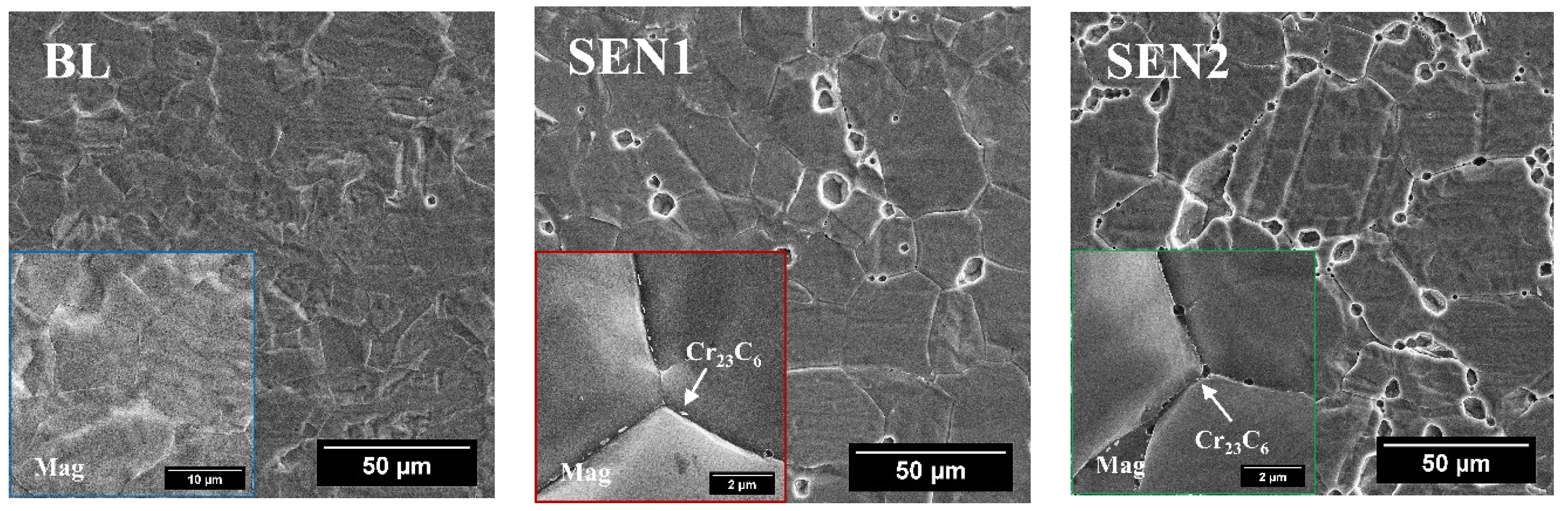

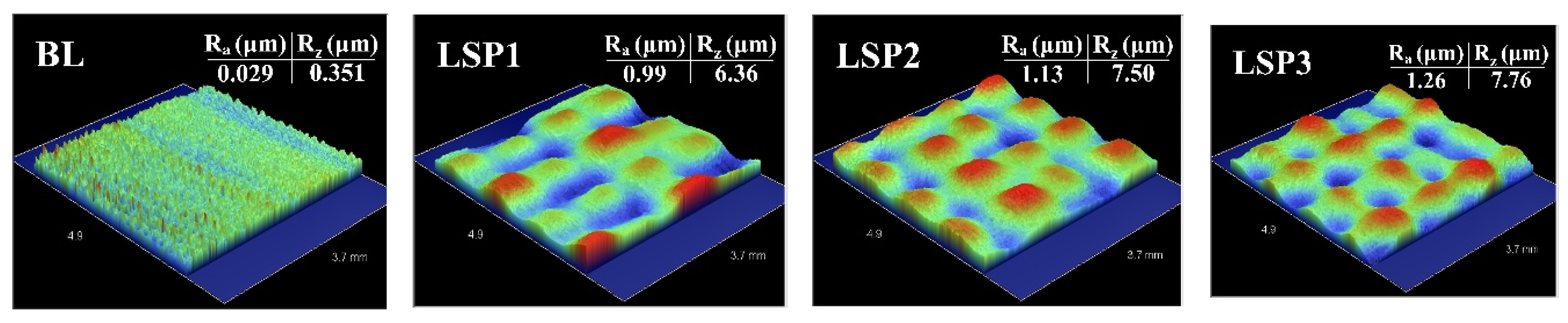

3.1. Microstructure Analysis and Surface Profile

3.2. Cyclic Polarization

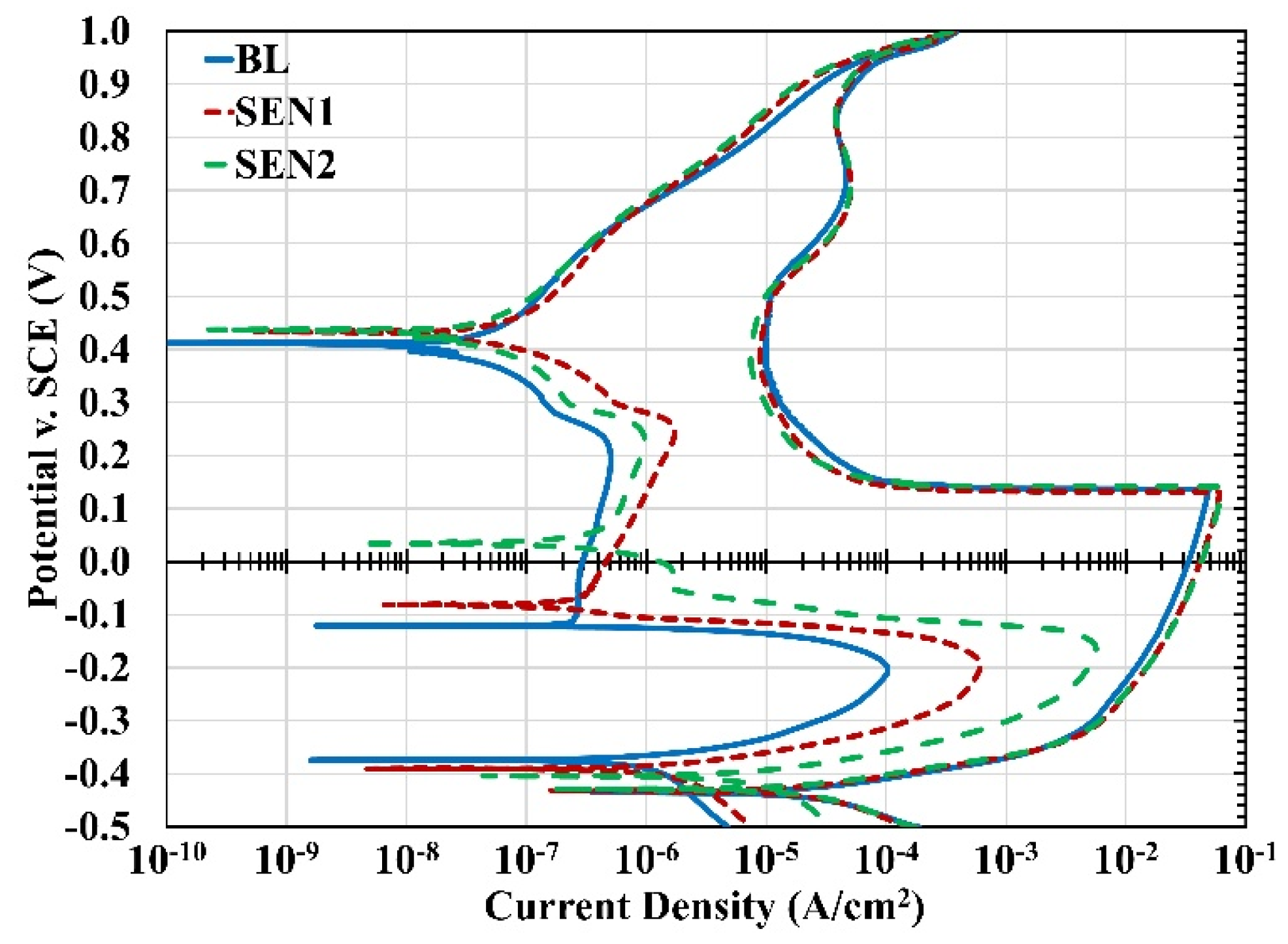

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Laser Shock Peening on 304L Stainless Steel

4.2. Effect of Laser Shock Peening Without Protective Coating on 304L Stainless Steel

5. Conclusions

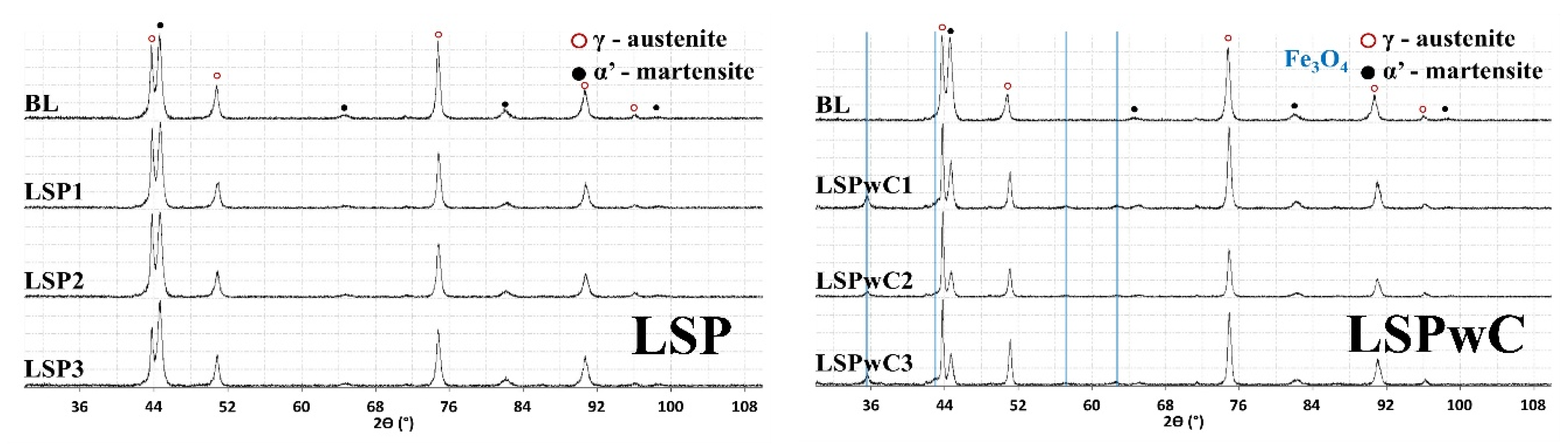

- Deformation-induced martensite was detected near the surface in both baseline and LSP-treated specimens. XRD analysis confirmed that the phase transformation resulted primarily from mechanical polishing rather than from the LSP process. The martensitic peaks disappeared after electropolishing, indicating that LSP’s high strain-rate favors deformation twinning rather than martensitic transformation in low-SFE austenitic stainless steels.

- LSP enhanced corrosion resistance in 304L stainless steel, particularly under mildly sensitized conditions (650 °C; 5hrs). This improvement is attributed to compressive residual stress and increased dislocation density, which together stabilized the passive film and lowered the corrosion rate. However, under higher peening intensities and more severe sensitization (650 °C; 24hrs) these benefits diminished, suggesting that further optimization of the LSP parameters is needed.

- LSPwC treatments degraded corrosion performance across all test conditions. The absence of a sacrificial overlay led to the formation of iron oxides at the surface, as confirmed by XRD, which interfered with passive film regeneration and increased corrosion susceptibility. These findings suggest that LSPwC may require additional post-processing (e.g., grit blasting or chemical cleaning) to restore surface integrity for corrosion-sensitive applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holtec International Final Safety Analysis Report for the HI-STORM 100 Cask System: HI-2002444; Marlton, NJ, 2006.

- Bayssie, M.; Dunn, D.; Csontos, A.; Caseres, L.; Mintz, T. Evaluation of Austenitic Stainless Steel Dry Storage Cask Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems Water Reactors; 2009; 2, pp. 1452–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Caseres, L.; Mintz, T.S. Atmospheric Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility of Welded and Unwelded 304, 304L and 316L Austenitic Stainless Steels Commonly Use for Dry Cask Storage Containers Exposed to Marine Engironments; San Antonio, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott, R.; Pitts, H. Chloride Stress Corrosion Cracking in Austenitic Stainless Steel: Assessing Susceptibility and Structural Integrity 2011.

- He, X.; Mintz, T.S.; Pabalan, R.; Miller, L.; Oberson, G. Assessment of Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility for Austenitic Stainless Steels Exposed to Atmospheric Chloride and Non-Chloride Salts; Washington, DC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EPRI Diablo Canyon Stainless Steel Dry Storage Canister Inspection: 3002002822. Palo Alto, CA, 2016.

- EPRI Calvert Cliffs Stainless Steel Dry Storage Canister Inspection: 1025209. Palo Alto, CA, 2014.

- Bryan, C.; Enos, D. Results of Stainless Steel Canister Corrosion Studies and Environmental Sample Investigations; Albuquerque, NM, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Enos, D.G.; Bryan, C.R. Understanding the Environment on the Surface of Spent Nuclear Fuel Interim Storage Containers; Albuquerque, NM, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.; Fuhr, K.; Broussard, J. Literature Review of Environmental Conditions and Chloride-Induced Degradation Relevant to Stainless Steel Canisters in Dry Cask Storage Systems; Palo Alto, CA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.M.; Pardini, A.F.; Cuta, J.M.; Adkins, H.E.; Casella, A.M.; Qiao, H.; Larche, M.R.; Diaz, A.A.; Doctor, S.R. NDE to Manage Atmospheric SCC in Canisters for Dry Storage of Spent Fuel: An Assessment; Richland, WA (United States), 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, J. Chloride-Induced Stress Corrosion Cracking of Used Nuclear Fuel Welded Stainless Steel Canisters: A Review. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 466, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedriks, J.A. Corrosion of Stainless Steels, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, 1996; ISBN 9780471007920. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, G.S. Pitting Corrosion of Metals A Review of the Critical Factors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 2186–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascali, R.; Benvenuti, A.; Wenger, D. CARBON CONTENT AND GRAIN SIZE EFFECTS ON THE SENSITIZATION OF AlSl TYPE 304 STAINLESS STEELS. Corrosion 1984, 40, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, E.C.; Abom, R.H.; Rutherford, J.J.B. The Nature and Precipitation of Intergranular Corrosion in Austenitic Stainless Steels. Trans. Am. Soc. Steel Treat. 1933, 21, 481–509. [Google Scholar]

- Enos, D.G.; Bryan, C.R. Final Report: Characterization of Canister Mockup Weld Residual Stresses; Albuquerque, NM, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, E.D.; Watkins, A.D.; Mcjunkin, T.R.; Pace, D.P.; Bitsoi, R.J. Remote Welding, NDE and Repair of DOE Standardized Canisters; Idaho Falls, ID (United States), 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peyre, P.; Scherpereel, X.; Berthe, L.; Carboni, C.; Fabbro, R.; Béranger, G.; Lemaitre, C. Surface Modifications Induced in 316L Steel by Laser Peening and Shot-Peening. Influence on Pitting Corrosion Resistance. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 280, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyre, P.; Braham, C.; Lédion, J.; Berthe, L.; Fabbro, R. Corrosion Reactivity of Laser-Peened Steel Surfaces. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2000, 9, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Qi, H.; Luo, K.Y.; Luo, M.; Cheng, X.N. Corrosion Behaviour of AISI 304 Stainless Steel Subjected to Massive Laser Shock Peening Impacts with Different Pulse Energies. Corros. Sci. 2014, 80, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Luo, K.Y.; Yang, D.K.; Cheng, X.N.; Hu, J.L.; Dai, F.Z.; Qi, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, J.S.; Wang, Q.W.; et al. Effects of Laser Peening on Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) of ANSI 304 Austenitic Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 2012, 60, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.-R.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-S. Effect of Laser Shock Peening on the Stress Corrosion Cracking of 304L Stainless Steel. Metals (Basel) 2023, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Ye, Z.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhancement of Corrosion Resistance of 304L Stainless Steel Treated by Massive Laser Shock Peening. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 154, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalainathan, S.; Sathyajith, S.; Swaroop, S. Effect of Laser Shot Peening without Coating on the Surface Properties and Corrosion Behavior of 316L Steel. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2012, 50, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Pan, Y.; Xu, F.; Tang, C. Effect of Laser Shock Peening on Stress Corrosion Sensitivity of 304 Stainless Steel C-Ring Weld Specimens. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 016516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandal, G.; Lawrence Yao, Y. Material Influence on Mitigation of Stress Corrosion Cracking Via Laser Shock Peening. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2017, 139, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, C.; Ling, X. Effects of Laser Shock Processing on Corrosion Resistance of AISI 304 Stainless Steel in Acid Chloride Solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 723, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Wen, J.; Nie, X.; Zhou, L. Study on the Effects of Multiple Laser Shock Peening Treatments on the Electrochemical Corrosion Performance of Welded 316L Stainless Steel Joints. Metals (Basel) 2022, 12, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Obata, M.; Kubo, T.; Mukai, N.; Yoda, M.; Masaki, K.; Ochi, Y. Retardation of Crack Initiation and Growth in Austenitic Stainless Steels by Laser Peening without Protective Coating. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 417, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Kulkarni, A.; Vasanth, G.; Kalainathan, S.; Shukla, P.; Vasudevan, V.K. Laser Shock Peening without Coating Induced Residual Stress Distribution, Wettability Characteristics and Enhanced Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, F.; Tang, C.; Cui, Y.; Xu, H.; Mao, J. Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility of 304 Stainless Steel Subjected to Laser Shock Peening without Coating. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 7163–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairand, B.P.; Clauer, A.H. Laser Generation of High-Amplitude Stress Waves in Materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1979, 50, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbro, R.; Fournier, J.; Ballard, P.; Devaux, D.; Virmont, J. Physical Study of Laser-Produced Plasma in Confined Geometry. J. Appl. Phys. 1990, 68, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM E915-21; Standard Practice for Verifying the Alignment of X-Ray Diffraction Instruments for Residual Stress Measurement. 2021.

- Hilley, M.E.; Larson, J.A.; Jatczak, C.F.; Ricklefs, R.E. Residual Stress Measurement by X-Ray Diffraction - SAE J784a; New York, NY, 1971; Vol. 15096. [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM G108-94; Standard Test Method for Electrochemical Reactivation ( EPR ) for Detecting Sensitization of AISI Type 304 and 304L Stainless Steels. West Conshohocken, PA, 2015.

- Devine, T.M. The Mechanism of Sensitization of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 1990, 30, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM E975-13; Standard Practice for X-Ray Determination of Retained Austenite in Steel with Near Random Crystallographic Orientation. West Conshohocken, PA, 2013.

- American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM G102-89; Standard Practice for Calculation of Corrosion Rates and Related Information from Electrochemical Measurements. West Conshohocken, PA, 2015.

- He, S.L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, D.M. Effect of Martensite Transformation on Chemical Composition, Semiconductor Property and Corrosion Resistance of Passive Film on SAE 304 Stainless Steel. Materwiss. Werksttech 2018, 49, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrrabal, G.; Bautista, A.; Guzman, S.; Gutierrez, C.; Velasco, F. Influence of the Cold Working Induced Martensite on the Electrochemical Behavior of AISI 304 Stainless Steel Surfaces. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunchun, X.; Gang, H. Effect of Deformation--induced Martensite on the Pit Propagation Behavior of 304 Stainless Steel. Anti-Corrosion Methods Mater. 2004, 51, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; Ruan, H.H.; Wang, J.; Chan, H.L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Lu, J. The Influence of Strain Rate on the Microstructure Transition of 304 Stainless Steel. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 3697–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K.; Olson, S.; Brockman, R.; Braisted, W.; Spradlin, T.; Fitzpatrick, M.E. High Strain--Rate Material Model Validation for Laser Peening Simulation. J. Eng. 2015, 2015, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Luo, K. Grain Refinement of AISI 304 SS Induced by Multiple Laser Shock Processing Impacts. In Laser Shock Processing of FCC Metals; Springer Series in Materials Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; Vol. 179, pp. 153–167. ISBN 978-3-642-35673-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ralls, A.M.; Mao, B.; Menezes, P.L. Tribological Performance of Laser Shock Peened Cold Spray Additive Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel. J. Tribol. 2023, 145, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Ralls, A.M.; Misra, M.; Menezes, P.L. Effect of Ultrasonic Impact Peening on Stress Corrosion Cracking Resistance of Austenitic Stainless-Steel Welds for Nuclear Canister Applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023, 584, 154590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyre, P.; Carboni, C.; Forget, P.; Beranger, G.; Lemaitre, C.; Stuart, D. Influence of Thermal and Mechanical Surface Modifications Induced by Laser Shock Processing on the Initiation of Corrosion Pits in 316L Stainless Steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 6866–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe | Cr | Ni | Mn | Cu | Si | Mo | N | P | C | S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304L | Bal. | 18.19 | 8.05 | 1.30 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.070 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.001 |

| Designation | Description |

|---|---|

| BL | As-Polished Baseline (600grit) |

| SEN1 | BL + 650 °C; 5hrs; Air Cooled (600grit) |

| SEN2 | BL + 650 °C; 24hr; Air Cooled (600grit) |

| Specimen Condition | Spot size (mm) | Overlap (%) | Pulse Energy (J) | Power Density (GW/cm2) | Pulse Duration (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSP1 / LSPwC1 | 2 | 50 | 1 | 1.4 | 22.3 |

| LSP2 / LSPwC2 | 2 | 50 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 20.8 |

| LSP3 / LSPwC3 | 2 | 50 | 3 | 3.2 | 30.0 |

| Parameters | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Material Phase | Austenite | Martensite |

| Detector | PSSD (Position Sensitive Scintillation Detector); 20° 2θ range | |

| Radiation Type | Mn Kα ( λ = 2.10 Å ) | Cr Kα ( λ = 2.29 Å ) / V Filter |

| Plane | {311} | {211} |

| Bragg’s Angle | 152.8° | 155.1° |

| Tilt Angles | 0.00°; ±2.61°; ±9.09°; ±12.40°; ±18.81°; ±23.00° | |

| Aperture Size | 2mm | |

| Exposure Time | 0.25s / 0.25s | 2.0s / 2.0s |

| X-Ray Elastic Constants | S1: -1.20 X 10-6 MPa-1 S2/2: 7.18 X 10-6 MPa-1 |

S1: -1.20 X 10-6 MPa-1 S2/2: 5.67 X 10-6 MPa-1 |

| Specimen Condition |

BL | LSP1 | LSP2 | LSP3 | LSPwC1 | LSPwC2 | LSPwC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Martensite | 9.42 | 10.06 | 10.77 | 11.64 | 9.07 | 9.08 | 8.18 |

| ID | Avg. Surface RS Aust. (MPa); 0° | Avg. Surface RS Aust. (MPa); 90° | Avg. Surface RS Mart. (MPa); 0° | Avg. Surface RS Mart. (MPa); 90° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | -165.2 ± 29.4 | -227.6 ± 25.6 | -561.3 ± 35.9 | -1281.0 ± 27.8 |

| LSP1 | -209.1 ± 34.3 | -266.8 ± 25.7 | -216.5 ± 37.2 | -886.9 ± 38.8 |

| LSP2 | -208.2 ± 30.2 | -249.2 ± 24.0 | -255.5 ± 35.9 | -780.5 ± 26.5 |

| LSP3 | -374.3 ± 24.1 | -397.6 ± 28.5 | -647. ± 32.99 | -935.0 ± 26.9 |

| Sample ID | ΔEcorr | ΔIcorr | %DOS | CR (mpy|mmpy) | |

| BL | +60.6 | −25.92e-6 | 0.21 | 28.24 | 0.718 |

| BL-LSP1 | +78.1 | −22.64e-6 | 0.04 | 27.25 | 0.622 |

| BL-LSP2 | +44.4 | −5.84e-6 | 0.87 | 8.55 | 0.195 |

| BL-LSP3 | +55.0 | −6.44e-6 | 0.39 | 9.53 | 0.218 |

| BL-LSPwC1 | −11.6 | −10.52e-6 | 1.21 | 17.24 | 0.394 |

| BL-LSPwC2 | −6.8 | −12.36e-6 | 1.05 | 19.41 | 0.444 |

| BL-LSPwC3 | −11.1 | −8.90e-6 | 1.10 | 15.20 | 0.348 |

| SEN1 | +41.1 | −21.52e-6 | 1.01 | 24.54 | 0.624 |

| SEN1-LSP1 | +56.6 | −7.21e-6 | 0.61 | 10.84 | 0.248 |

| SEN1-LSP2 | +43.1 | −7.99e-6 | 0.82 | 11.64 | 0.266 |

| SEN1-LSP3 | +56.9 | −12.46e-6 | 0.61 | 16.73 | 0.382 |

| SEN1-LSPwC1 | −6.1 | −6.56e-6 | 3.66 | 15.59 | 0.356 |

| SEN1-LSPwC2 | −8.8 | −8.77e-6 | 2.38 | 17.34 | 0.396 |

| SEN1-LSPwC3 | −3.7 | −3.67e-6 | 5.03 | 14.74 | 0.336 |

| SEN2 | +24.8 | −10.43e-6 | 8.86 | 23.51 | 0.597 |

| SEN2-LSP1 | +24.7 | +4.82e-6 | 11.99 | 20.50 | 0.469 |

| SEN2-LSP2 | +19.6 | +7.35e-6 | 9.66 | 11.54 | 0.264 |

| SEN2-LSP3 | +19.2 | +8.08e-6 | 11.32 | 10.27 | 0.235 |

| SEN2-LSPwC1 | −12.0 | −2.35e-6 | 11.01 | 17.16 | 0.393 |

| SEN2-LSPwC2 | −2.2 | +2.62-6 | 18.06 | 20.30 | 0.464 |

| SEN2-LSPwC3 | −7.2 | +3.06e-6 | 19.82 | 16.08 | 0.368 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).