Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

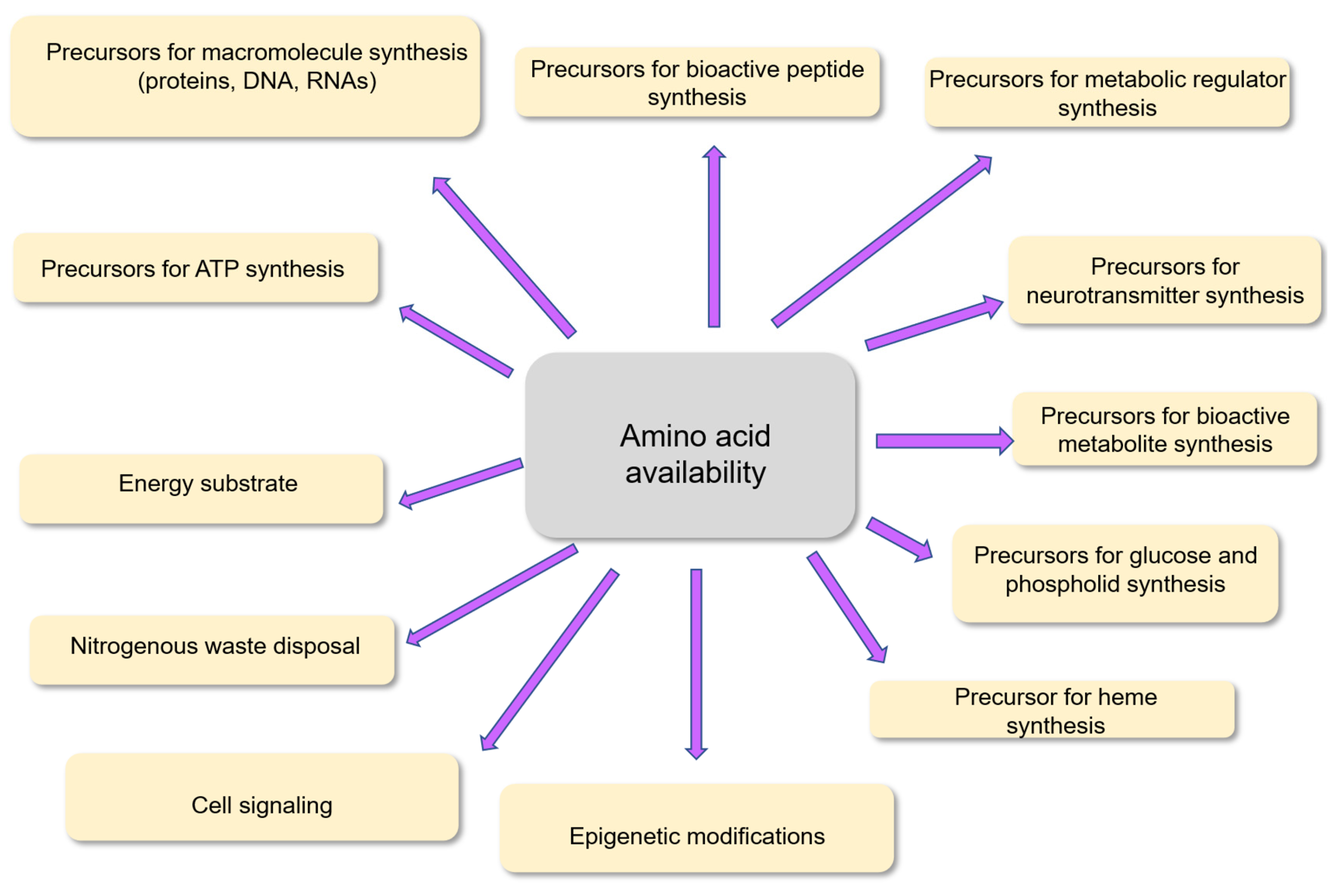

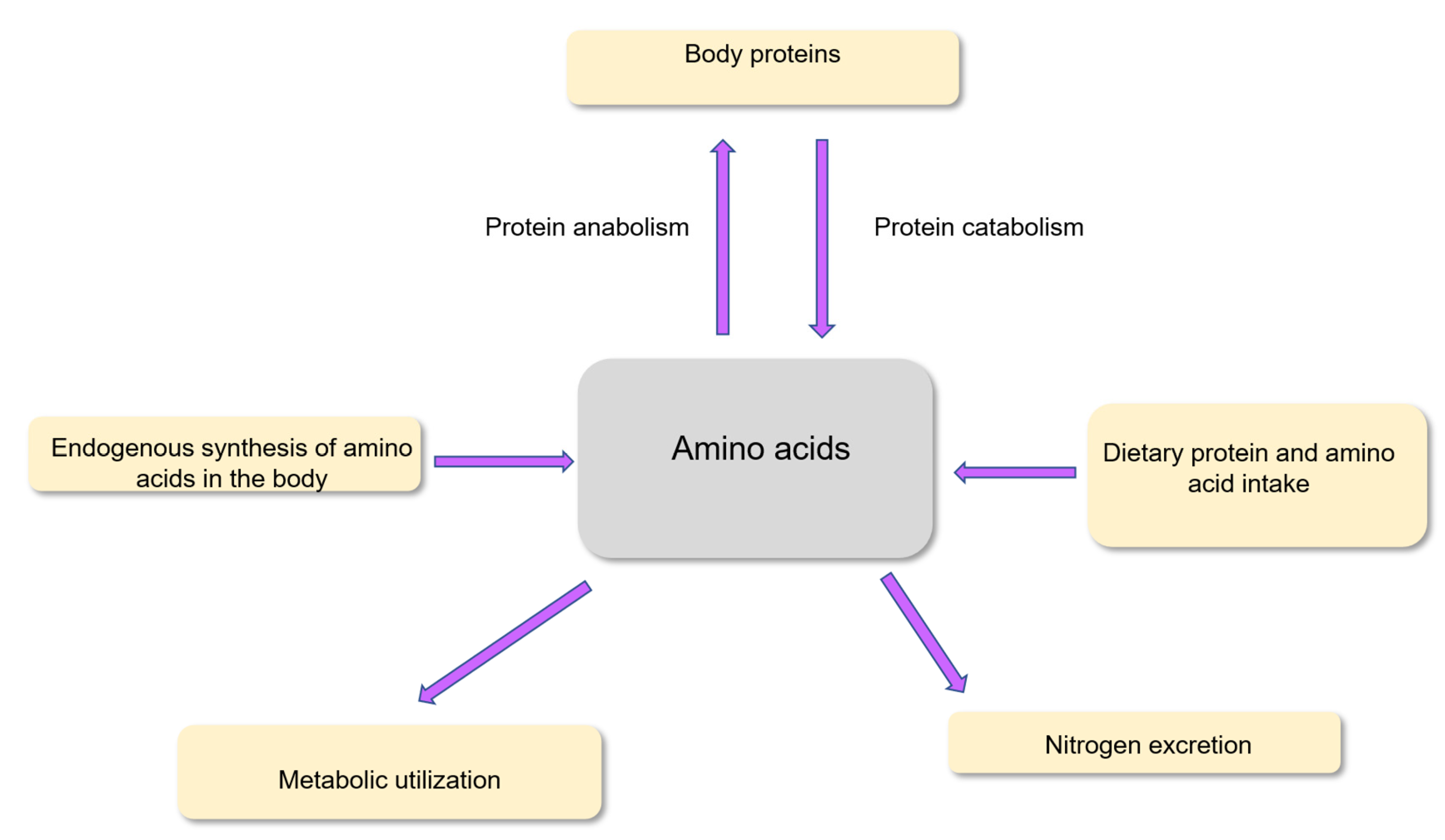

1. Introduction

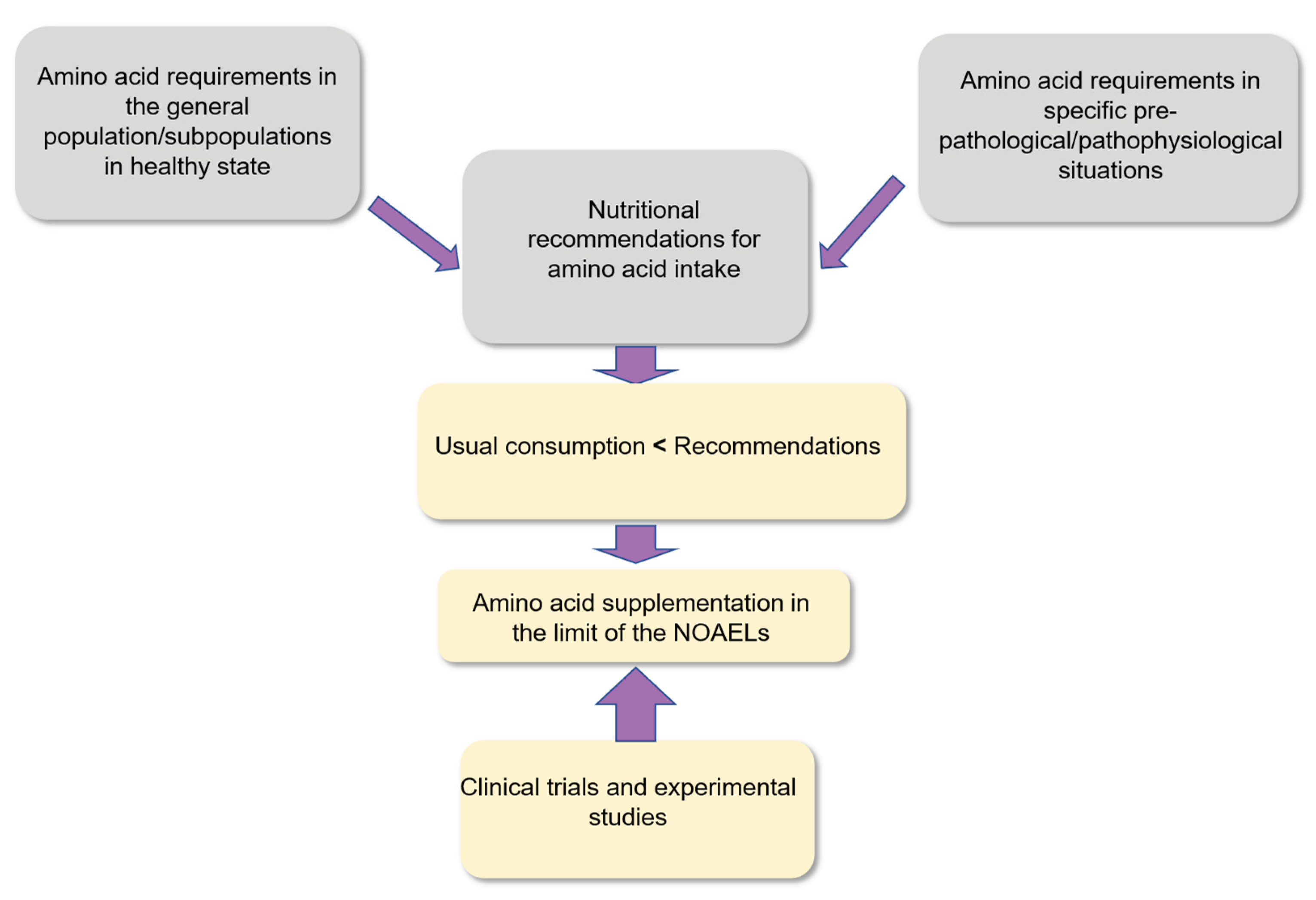

2. Protein and Amino Acid Requirement Along the Life Cycle and Comparison with Usual Consumption in Different Geographical Areas

2.1. Protein Requirement in Different Situations

2.2. Indispensable Amino Acid Requirement in Adults and Comparison with Usual Consumption in Western Countries

3. Amino Acid Supplementation in Specific Situations: Lessons from Clinical Trials and Experimental Studies

3.1. Leucine Supplementation in the Sarcopenic Elderly

3.2. Amino Acid Supplementation in Athletes

3.3. Amino Acid Supplementation for Intestinal Mucosa Healing

3.4. Amino Acid Supplementation During Weight Loss Programs

3.5. Amino Acid Supplementation in Metabolic Syndrome

3.6. Amino Acid Supplementation in Miscellaneous Situations

4. Safe Utilization of Amino Acids in Supplements

5. Conclusions and Prospects

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blachier, F. Amino acid metabolism for human physiology. In The evolutionary journey of amino acids. From the origin of life to human metabolism; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bechaux, J.; Gatellier, P.; Le Page, J.F.; Drillet, Y.; Sante-Lhoutellier, V. A comprehensive review of bioactive peptides obtained from animal byproducts and their applications. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6244–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldovic, L.; Tuchman, M. N-acetylglutamate and its changing role through evolution. Biochem. J. 2003, 372, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Procopio, J.; Lima, M.M.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; Curi, R. Glutamine and glutamate--their central role in cell metabolism and function. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2003, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahren, J.; Ekberg, K. Splanchnic regulation of glucose production. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 329–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neinast, M.; Murashige, D.; Arany, Z. Branched Chain Amino Acids. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignarro, L.J. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide: actions and properties. FASEB J. 1989, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J. T.; Brosnan, M.E. The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1636S–1640S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etchegaray, J.P.; Mostoslavsky, R. Interplay between metabolism and epigenetics: a nuclear adaptation to environmental changes. Mol. Cell. 2016, 62, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmezat, T.; Breuillé, D.; Capitan, P.; Mirand, P.P.; Obled, C. Glutathione turnover is increased during the acute phase of sepsis in rats. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémond, D.; Buffière, C.; Pouyet, C.; Papet, I.; Dardevet, D.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Williamson, G.; Faure, M.; Breuillé, D. Cysteine fluxes across the portal-drained viscera of enterally fed minipigs: effect of an acute intestinal inflammation. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, Y. Protein turnover, ureagenesis and gluconeogenesis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2011, 81, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietzen, D.W.; Rogers, QR. Nutritional homeostasis and indispensable amino acid sensing: a new solution to an old puzzle. Trends Neurosci. 2006, 29, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeds, P.J. Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1835S–1840S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, A.; Nishimura, Y.; Ono, H.; Sakura, N. Betaine and homocysteine concentrations in foods. Pediatr. Int. 2002, 44, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F.; Andriamihaja, M.; Blais, A. Sulfur-containing amino acids and lipid metabolism. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2524S–2531S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manary, M.J.; Wegner, D.R.; Maleta, K. Protein quality malnutrition. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1428810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, P.; Stehle, P. What are the essential elements needed for the determination of amino acid requirements in humans? J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1558S–1565S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Castillo, L.; Lu, X.M.; Beaumier, L.; Tompkins, R.G.; Young, V.R. Arginine and ornithine kinetics in severely burned patients: increased rate of arginine disposal. Am. J. Physiol. 2001, 280, E509–E517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, R.A.; Hardy, G. Clinical and nutritional benefits of cysteine-enriched protein supplements. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, T.; Mao, F.; Mao, Z. The emerging role of oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1390351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, I.; Biswas, S.K.; Jimenez, L.A.; Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Glutathione, stress responses, and redox signaling in lung inflammation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2005, 7, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, J.M.; Wilmore, D.W. Is glutamine a conditionally essential amino acid? Nutr. Rev. 1990, 48, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, B.F.; Ennis, M.A.; Dyer, R.A.; Lim, K.; Elango, R. Glycine, a dispensable amino acid, is conditionally indispensable in late stages of human pregnancy. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Dietary protein intake and human health. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, W.M.; Pellett, P.L.; Young, V.R. Meta-analysis of nitrogen balance studies for estimating protein requirements in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuisson, C.; Lioret, S.; Touvier, M.; Dufour, A.; Calamassi-Tran, G.; Volatier, J.L.; Lafay, L. Trends in food and nutritional intakes of French adults from 1999 to 2007: results from the INCA surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasiakos, S.M.; Agarwal, S.; Lieberman, H.R.; Fulgoni, V.L, 3rd. Sources and amounts of animal, dairy, and plant protein intake of US adults in 2007-2010. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7058–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Halloran, A.; Rippin, H.L.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dardavesis, T.I.; Williams, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3503–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of sociodemographic and nutritional characteristics between self-reported vegetarians, vegans, and meat-eaters from the NutriNet-Santé study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hasan, S.M.; Saulam, J.; Mikami, F.; Kanda, K.; Ngatu, N.R.; Yokoi, H.; Hirao, T. Trends in per capita food and protein availability at the national level of the Southeast Asian countries: An Analysis of the FAO’s Food Balance Sheet Data from 1961 to 2018. Nutrients 2022, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asayehu, T.T.; Lachat, C.; Henauw, S.; Gebreyesus, S.H. Dietary behaviour, food and nutrient intake of women do not change during pregnancy in Southern Ethiopia. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2017, 13, e12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments/ French Agency for Food Safety. Protein intake: dietary intake, quality, requirements and recommendations. 2007.

- Burstad, K.M.; Lamina, T.; Erickson, A.; Gholizadeh, E.; Namigga, H.; Claussen, A.M.; Slavin, J.L.; Teigen, L.; Hill Gallant, K.M.; Stang, J.; Steffen, L.M.; Harindhanavudhi, T.; Kouri, A.; Duval, S.; Butler, M. Evaluation of dietary protein and amino acid requirements: a systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogeri, P.S.; Zanella, R., Jr.; Martins, G.L.; Garcia, M.D.A.; Leite, G.; Lugaresi, R.; Gasparini, S.O.; Sperandio, G.A.; Ferreira, L.H.B.; Souza-Junior, T.P.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. Strategies to prevent sarcopenia in the aging process: role of protein intake and exercise. Nutrients 2021, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Miller, S.L.; Miller, K.B. Optimal protein intake in the elderly. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Baerlocher, K.; Bauer, J.M.; Elmadfa, I.; Heseker, H.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Stangl, G.; Volkert, D.; Stehle, P.; on behalf of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Revised Reference Values for the Intake of Protein. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancha, A.H., Jr.; Zanella, R., Jr.; Tanabe, S.G.; Andriamihaja, M.; Blachier, F. Dietary protein supplementation in the elderly for limiting muscle mass loss. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, M.; Craven, D.; Mackay, H.; Marx, W.; de van der Schueren, M.; Marshall, S. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition: associations with geographical region and sex. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Van Loon, L.J. Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, S29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Nutrition Board (FNB); Institute of Medicine (IOM). Dietary reference intake for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids; The National Academies Press: Washington DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. Report of a Joints WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blachier, F.; Blais, A.; Elango, R.; Saito, K.; Shimomura, Y.; Kadowaki, M.; Matsumoto, H. Tolerable amounts of amino acids for human supplementation: summary and lessons from published peer-reviewed studies. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguacel, I.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Schmidt, J.A.; Van Puyvelde, H.; Travis, R.; Casagrande, C.; Nicolas, G.; Riboli, E.; Weiderpass, E.; Ardanaz, E.; et al. Evaluation of protein and amino acid intake estimates from the EPIC dietary questionnaires and 24-h dietary recalls using different food composition databases. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elango, R. Tolerable upper intake for individual amino acids in humans: a narrative review of recent clinical studies. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; Schneider, S.M.; Sieber, C.C.; Topinkova, E.; Vandewoude, M.; Visser, M.; Zamboni, M. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2.Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagopal, P.; Rooyackers, O.E.; Adey, D.B.; Ades, P.A.; Nair, K.S. Effects of aging on in vivo synthesis of skeletal muscle myosin heavy-chain and sarcoplasmic protein in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 273, E790–E800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooyackers, O.E.; Adey, D.B.; Ades, P.A.; Nair, K.S. Effect of age on in vivo rates of mitochondrial protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1996, 93, 15364–15369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.R.; Bigelow, M.L.; Kahl, J.; Singh, R.; Coenen-Schimke, J.; Raghavakaimal, S.; Nair, K.S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2005, 102, 5618–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezze, C; Sandri, M; Tessari, P. Anabolic resistance in the pathogenesis of sarcopenia in the elderly: role of nutrition and exercise in young and old people. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.; K. Nicklas, B.J.; Ding, J.; Harris, T.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Newman, A.B.; Lee, J.S.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Visser, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Health ABC Study. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Rasmussen, B.B. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Kong, X.; Feng, Z.; Anthony, T.G.; Watford, M.; Hou, Y.; Wu, G; Yin, Y. The role of leucine and its metabolites in protein and energy metabolism. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; He, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G.; Ma, X. Branched chain amino acids: beyond nutrition metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.; Koscien, C.P.; Monteyne, A.J.; Wall, B.T.; Stephens, F.B. Association of postprandial postexercise muscle protein synthesis rates with dietary leucine: A systematic review. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieu, I.; Balage, M.; Sornet, C.; Giraudet, C.; Pujos, E.; Grizard, J.; Mosoni, L.; Dardevet, D. Leucine supplementation improves muscle protein synthesis in elderly men independently of hyperaminoacidaemia. J. Physiol. 2006, 575, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.D.; Hirsch, K.R.; Park, S.; Kim, I.Y.; Gwin, J.A.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Wolfe, R.R.; Ferrando, A.A. Essential amino acids and protein synthesis: insights into maximizing the muscle and whole-body response to feeding. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Klersy, C.; Terracol, G.; Talluri, J.; Maugeri, R.; Guido, D.; Faliva, M.A.; Solerte, B.S.; Fioravanti, M.; Lukaski, H.; Perna, S. Whey protein, amino acids, and vitamin D supplementation with physical activity increases fat-free mass and strength, functionality, and quality of life and decreases inflammation in sarcopenic elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Cereda, E.; Klersy, C.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Nichetti, M.; Gasparri, C.; Iannello, G.; Spadaccini, D.; Infantino, V.; Caccialanza, R.; Perna, S. Improving rehabilitation in sarcopenia: a randomized-controlled trial utilizing a muscle-targeted food for special medical purposes. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1535–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.M.; Verlaan, S.; Bautmans, I.; Brandt, K.; Donini, L.M.; Maggio, M.; McMurdo, M.E.; Mets, T.; Seal, C.; Wijers, S.L.; Ceda, G.P.; De Vito, G.; Donders, G.; Drey, M.; Greig, C.; Holmbäck, U.; Narici, M.; McPhee, J.; Poggiogalle, E.; Power, D.; Scafoglieri, A.; Schultz, R.; Sieber, C.C.; Cederholm, T. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the PROVIDE study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Huma, N.; Pasha, I.; Sameen, A.; Mukhtar, O.; Khan, MI. Chemical composition, nitrogen fractions and amino acids profile of milk from different animal species. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwiega, S.; Pencharz, P.B.; Rafii, M.; Lebarron, M.; Chang, J.; Ball, R.O.; Kong, D.; Xu, L.; Elango, R.; Courtney-Martin, G. Dietary leucine requirement of older men and women is higher than current recommendations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispoglou, T.; Witard, O.C.; Duckworth; L, C.; Lees, M.J. The efficacy of essential amino acid supplementation for augmenting dietary protein intake in older adults: implications for skeletal muscle mass, strength and function. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Hoogendijk, E.O.; Visvanathan, R.; Wright, O.R.L. Malnutrition screening and assessment in hospitalised older people: a review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, R.A.; Landi, F.; Smoyer, K.E.; Tarasenko, L.; Groarke, J. Association of anorexia/appetite loss with malnutrition and mortality in older populations: A systematic literature review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 706–729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, M.; Lees, M.; Harlow, P.; Hind, K.; Duckworth, L.; Ispoglou, T. Acute effects of essential amino acid gel-based and whey protein supplements on appetite and energy intake in older women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Ispoglou, T.; Deighton, K.; King, R.F.; White, H.; Lees, M. Novel essential amino acid supplements enriched with L-leucine facilitate increased protein and energy intakes in older women: a randomised controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Opizzi, A.; Antoniello, N.; Boschi, F.; Iadarola, P.; Pasini, E.; Aquilani, R.; Dioguardi, F.S. Effect of essential amino acid supplementation on quality of life, amino acid profile and strength in institutionalized elderly patients. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispoglou, T.; White, H.; Preston, T.; McElhone, S.; McKenna, J.; Hind, K. Double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of L-Leucine-enriched amino-acid mixtures on body composition and physical performance in men and women aged 65-75 years. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komar, B.; Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G. Effects of leucine-rich protein supplements on anthropometric parameter and muscle strength in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, E.; Beckwée, D.; Delaere, A.; De Breucker, S.; Vandewoude, M.; Bautmans, I.; Sarcopenia Guidelines Development Group of the Belgian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (BSGG). Nutritional interventions to improve muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in older people: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Lepe, M.A.; Miranda-Gil, M.I.; Valbuena-Gregorio, E.; Olivas-Aguirre, F.J. Exercise programs combined with diet supplementation improve body composition and physical function in older adults with sarcopenia: A systematic review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, A.; Barrile, G.C.; Mansueto, F.; Rondanelli, M. The nutritional support to prevent sarcopenia in the elderly. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1379814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde Maldonado, E.; Marqués-Jiménez, D.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Bach-Faig, A. Effect of supplementation with leucine alone, with other nutrients or with physical exercise in older people with sarcopenia: a systematic review. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2022, 69, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.R.; Tan, Z.J.; Zhang, Q.; Gui, Q.F.; Yang, Y.M. The effectiveness of leucine on muscle protein synthesis, lean body mass and leg lean mass accretion in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, D.L.; Delcastillo, K.; Van Every, D.W.; Tipton, K.D.; Aragon, A.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Isolated leucine and branched-chain amino acid supplementation for enhancing muscular strength and hypertrophy: a narrative review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2021, 31, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hall, G.; Raaymakers, J.S.; Saris, W.H.; Wagenmakers, A.J. Ingestion of branched-chain amino acids and tryptophan during sustained exercise in man: failure to affect performance. J. Physiol. 1995, 486, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.S.; Schwartz, R.G.; Welle, S. Leucine as a regulator of whole body and skeletal muscle protein metabolism in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 263, E928–E934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomstrand, E.; Saltin, B. BCAA intake affects protein metabolism in muscle after but not during exercise in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 2001, 281, E365–E374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jahn, L.A.; Long, W.; Fryburg, D.A.; Wei, L.; Barrett, E.J. Branched chain amino acids activate messenger ribonucleic acid translation regulatory proteins in human skeletal muscle, and glucocorticoids blunt this action. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 2136–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipton, K.D.; Ferrando, A.A.; Phillips, S.M.; Doyle, D., Jr.; Wolfe, R.R. Postexercise net protein synthesis in human muscle from orally administered amino acids. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, E628–E634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.W.; Burd, N.A.; Coffey, V.G.; Baker, S.K.; Burke, L.M.; Hawley, J.A; Moore, D.R.; Stellingwerff, T.; Phillips, S.M. Rapid aminoacidemia enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis and anabolic intramuscular signaling responses after resistance exercise. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, Y.; Murakami, T.; Nakai, N.; Nagasaki, M.; Harris, R.A. Exercise promotes BCAA catabolism: effects of BCAA supplementation on skeletal muscle during exercise. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1583S–1587S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, Y.; Fujii, H.; Suzuki, M.; Murakami, T.; Fujitsuka, N.; Nakai, N. Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex in rat skeletal muscle: regulation of the activity and gene expression by nutrition and physical exercise. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1762S–1765S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonio, J.; Candow, D.G.; Forbes, S.C.; Gualano, B.; Jagim, A.R.; Kreider, R.B.; Rawson, E.S.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; VanDusseldorp, T.A.; Willoughby, D.S.; et al. Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show? J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, R.; Piñero, A.; Coleman, M.; Mohan, A.; Sapuppo, M.; Augustin, F.; Aragon, A.A.; Candow, D.G.; Forbes, S.C.; Swinton, P.; et al. The effects of creatine supplementation combined with resistance training on regional measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Zielińska, M.; Sokal, A.; Filip, R. Genetic and epigenetic etiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an update. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lochs, H.; Löfberg, R.; Modigliani, R.; Present, D.H.; Rutgeerts, P.; Schölmerich, J.; Stange, E.F.; Sutherland, L.R. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Haens, G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Geboes, K.; Hanauer, S.B.; Irvine, E.J.; Lémann, M.; Marteau, P.; Rutgeerts, P.; Schölmerich, J.; et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, G.R.; Rutgeerts, P. Importance of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineton de Chambrun, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Lémann, M.; Colombel, J.F. Clinical implications of mucosal healing for the management of IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, M.; Loftus, E.V., Jr. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease-a true paradigm of success? Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (N Y) 2012, 8, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Neurath, M.F.; Travis, S.P. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut 2012, 61, 1619–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D.; Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, A.; Blachier, F.; Benamouzig, R.; Beaumont, M.; Barrat, C.; Coelho, D.; Lancha, A., Jr.; Kong, X.; Yin, Y.; Marie, J.C.; et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: is there a place for nutritional supplementation? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Dignass, A.U. Epithelial restitution and wound healing in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alastair, F.; Emma, G.; Emma, P. Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2011, 35, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulnigg, S.; Gasche, C. Systematic review: managing anaemia in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 24, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Munsell, M.; Harris, M.L. Nationwide prevalence and prognostic significance of clinically diagnosable protein-calorie malnutrition in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.; Eliakim, R.; Shamir, R. Nutritional status and nutritional therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 2570–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Huix, F.; de León, R.; Fernández-Bañares, F.; Esteve, M.; Cabré, E.; Acero, D.; Abad-Lacruz, A.; Figa, M.; Guilera, M.; Planas, R.; et al. Polymeric enteral diets as primary treatment of active Crohn’s disease: a prospective steroid controlled trial. Gut 1993, 34, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Banares, F.; Cabré, E.; Esteve-Comas, M.; Gassull, M.A. How effective is enteral nutrition in inducing clinical remission in active Crohn’s disease ? A meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 1995, 19, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messori, A.; Trallori, G.; D’Albasio, G.; Milla, M.; Vannozzi, G.; Pacini, F. Defined-formula diets versus steroids in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 31, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.M.; Ohlsson, A.; Sherman, P.M.; Sutherland, L.R. Meta-analysis of enteral nutrition as a primary treatment of active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, A.; Escher, J.; Hébuterne, X.; Kłęk, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Schneider, S.; Shamir, R.; Stardelova, K.; Wierdsma, N.; Wiskin, A.E.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Lletjós, S.; Khodorova, N.V.; Piscuc, M.; Gaudichon, C.; Blachier, F.; Lan, A. Tissue-specific effect of colitis on protein synthesis in mice: impact of the dietary protein content. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Lletjós, S.; Andriamihaja, M.; Blais, A.; Grauso, M.; Lepage, P.; Davila, A.M.; Viel, R.; Gaudichon, C.; Leclerc, M.; Blachier, F.; et al. Dietary Protein Intake Level Modulates Mucosal Healing and Mucosa-Adherent Microbiota in Mouse Model of Colitis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F.; Beaumont, M.; Andriamihaja, M.; Davila, A.M.; Lan, A.; Grauso, M.; Armand, L.; Benamouzig, R.; Tomé, D. Changes in the luminal environment of the colonic epithelial cells and physiopathological consequences. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, M; Mettraux, C; Moennoz, D; Godin, JP; Vuichoud, J; Rochat, F; Breuillé, D; Obled, C; Corthésy-Theulaz, I. Specific amino acids increase mucin synthesis and microbiota in dextran sulfate sodium-treated rats. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, F.; Karrasch, T.; Ben-Horin, S.; Schirbel, A.; Ehehalt, R.; Wehkamp, J.; de Haar, C.; Velin, D.; Latella, G.; Scaldaferri, F.; et al. Results of the 2nd scientific workshop of the ECCO (III): basic mechanisms of intestinal healing. J. Crohns Colitis 2012, 6, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiesslich, R.; Goetz, M.; Angus, E.M.; Hu, Q.; Guan, Y.; Potten, C.; Allen, T.; Neurath, M.F.; Shroyer, N.F.; Montrose, M.H.; et al. Identification of epithelial gaps in human small and large intestine by confocal endomicroscopy. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.J.; Chu, S.; Sieck, L.; Gerasimenko, O.; Bullen, T.; Campbell, F.; McKenna, M.; Rose, T.; Montrose, M.H. Epithelial barrier function in vivo is sustained despite gaps in epithelial layers. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, M.; Moënnoz, D.; Montigon, F.; Mettraux, C.; Breuillé, D.; Ballèvre, O. Dietary threonine restriction specifically reduces intestinal mucin synthesis in rats. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Beaumont, M.; Walker, F.; Chaumontet, C.; Andriamihaja, M.; Matsumoto, H.; Khodorova, N.; Lan, A.; Gaudichon, C.; Benamouzig, R.; et al. Beneficial effects of an amino acid mixture on colonic mucosal healing in rats. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F.; Boutry, C.; Bos, C.; Tomé, D. Metabolism and functions of L-glutamate in the epithelial cells of the small and large intestines. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 814S–821S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthi, S.; Jessop, C.E.; Bulleid, N.J. The role of glutathione in disulphide bond formation and endoplasmic-reticulum-generated oxidative stress. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, M.; Go, Y.M.; Jones, D.P. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of thiol/disulfide redox systems: a perspective on redox systems biology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, T.; Mao, F.; Mao, Z. The emerging role of oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1390351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedijk, M.A.; Stoll, B.; Chacko, S.; Schierbeek, H.; Sunehag, A.L.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Burrin, D.G. Methionine transmethylation and transsulfuration in the piglet gastrointestinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2007, 104, 3408–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yin, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. An elemental diet enriched in amino acids alters the gut microbial community and prevents colonic mucus degradation in mice with colitis. mSystems 2022, 7, e0088322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.X.; Quek, K.F.; Ramadas, A. Dietary and lifestyle risk factors of obesity among young adults: a scoping review of observational studies. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.M. On the causes of obesity and its treatment: The end of the beginning. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Yan, Y.; Qiu, X.; Lin, S.; Wen, J. Endoscopic bariatric surgery for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2025, 49, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, I.; Anyiam, O. The latest evidence and guidance in lifestyle and surgical interventions to achieve weight loss in people with overweight or obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, E.; Yeat, N.C.; Mittendorfer, B. Preserving healthy muscle during weight loss. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 511–519. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D.; Berg, A. Weight loss strategies and the risk of skeletal muscle mass loss. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuijten, M.A.H.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; Monpellier, V.M.; Janssen, I.M.C.; Hazebroek, E.J.; Hopman, M.T.E. The magnitude and progress of lean body mass, fat-free mass, and skeletal muscle mass loss following bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sargeant, J.A.; Henson, J.; King, J.A.; Yates, T.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. A review of the effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on lean body mass in humans. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2019, 34, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, E.; Kelsey, R.J.; Sargeant, J.A.; Henson, J.; Yates, T.; Wilkinson, T.J. Nutritional supplementation to preserve healthy lean mass and function during periods of pharmacological and nonpharmacological-induced weight loss: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70219. [Google Scholar]

- Wycherley, T.P.; Moran, L.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Noakes, M.; Brinkworth, G.D. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; >Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320S–1329S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villareal, D.T.; Chode, S.; Parimi, N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Hilton, T.; Armamento-Villareal, R.; Napoli, N.; Qualls, C.; Shah, K. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimel, T,N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Villareal, D.T. Exercise attenuates the weight-loss-induced reduction in muscle mass in frail obese older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, E.; Kumahara, H.; Tobina, T.; Matsuda, T.; Watabe, K.; Matono, S.; Ayabe, M.; Kiyonaga, A.; Anzai, K.; Higaki, Y.; et al. Aerobic exercise attenuates the loss of skeletal muscle during energy restriction in adults with visceral adiposity. Obes. Facts 2014, 7, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavaro, D.; Leva, F.; Caturano, A.; Berra, C.C.; Bonfrate, L.; Conte, C. Optimizing body composition during weight loss: the role of amino acid supplementation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, M.S.; Barati, Z.; Murphy, C.J.; Bateman, T.; Newcomer, B.R.; Wolfe, R.R.; Coker, R.H. Essential amino acid enriched meal replacement improves body composition and physical function in obese older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 51, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunani, A.; Cancello, R.; Gobbi, M.; Lucchetti, E.; Di Guglielmo, G.; Maestrini, S.; Cattaldo, S.; Piterà, P.; Ruocco, C.; Milesi, A.; et al. Comparison of protein- or amino acid-based supplements in the rehabilitation of men with severe obesity: a randomized controlled pilot study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhulaifi, F.; Darkoh, C. Meal timing, meal frequency and metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Després, J.P.; Lemieux, I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2006, 444, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.L. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis. Model Mech. 2009, 2, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassi, E.; Pervanidou, P.; Kaltsas, G.; Chrousos, G. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterseim, C.M.; Jabbour, K.; Kamath Mulki, A. Metabolic syndrome: an updated review on diagnosis and treatment for primary care clinicians. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241309168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, N.; Bains, K. Interplay between proteins and metabolic syndrome-A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2483–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucotti, P.; Setola, E.; Monti, L.D.; Galluccio, E.; Costa, S.; Sandoli, E.P.; Fermo, I.; Rabaiotti, G.; Gatti, R.; Piatti, P. Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am. J. Physiol. 2006, 291, E906–E912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piatti, P.M.; Monti, L.D.; Valsecchi, G.; Magni, F.; Setola, E.; Marchesi, F.; Galli-Kienle, M.; Pozza, G.; Alberti, K.G. Long-term oral L-arginine administration improves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonatto, J.; Cavalari, J.V. A single dosage of l-arginine oral supplementation induced post-aerobic exercise hypotension in hypertensive patients. J. Diet. Suppl. 2023, 20, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, L.D.; Setola, E.; Lucotti, P.C.; Marrocco-Trischitta, M.M.; Comola, M.; Galluccio, E.; Poggi, A.; Mammì, S.; Catapano, A.L.; Comi, G.; et al. Effect of a long-term oral l-arginine supplementation on glucose metabolism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wascher, T.C.; Graier, W.F.; Dittrich, P.; Hussain, M.A.; Bahadori, B.; Wallner, S.; Toplak, H. Effects of low-dose L-arginine on insulin-mediated vasodilatation and insulin sensitivity. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 27, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D. Impairment and restoration of nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 1997, 62, S101–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, T.D. Aspects of nitric oxide in health and disease: a focus on hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2006, 8, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginato, G.S.; de Jager, L.; Martins, A.B.; Lucchetti, B.F.C.; de Campos, B.H.; Lopes, F.N.C.; Araujo, E.J.A.; Zaia, C.T.B.V.; Pinge-Filho, P.; Martins-Pinge, M.C. Differential benefits of physical training associated or not with l-arginine supplementation in rats with metabolic syndrome: Evaluation of cardiovascular, autonomic and metabolic parameters. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 268, 114251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagami, K.; Okuzawa, T.; Yoshida, K.; Mishima, R.; Obara, N.; Kunimatsu, A.; Koide, M.; Teranishi, T.; Itakura, K.; Ikeda, K.; et al. L-arginine ameliorates hypertension and cardiac mitochondrial abnormalities but not cardiac injury in male metabolic syndrome rats. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Kauter, K.; Withers, K.; Sernia, C.; Brown, L. Chronic l-arginine treatment improves metabolic, cardiovascular and liver complications in diet-induced obesity in rats. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, T.; Nomura, M.; Nisikado, A.; Nakaya, Y.; Ito, S. Supplementation of L-arginine improves hypertension and lipid metabolism but not insulin resistance in diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2003, 73, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiordelisi, A.; Cerasuolo, F.A.; Avvisato, R.; Buonaiuto, A.; Maisto, M.; Bianco, A.; D’Argenio, V.; Mone, P.; Perrino, C.; D’Apice, S.; et al. L-arginine supplementation as mitochondrial therapy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felig, P.; Marliss, E.; Cahill, G.F., Jr. Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1969, 281, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, P.; Van Horn, C.; Reid, T.; Hutson, S.M.; Cooney, R.N.; Lynch, C.J. Obesity-related elevations in plasma leucine are associated with alterations in enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 2007, 293, E1552–E1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shao, J.; Wu, C.Y.; Shu, L.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Wynn, R.M.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Targeting BCAA catabolism to treat obesity-associated insulin resistance. Diabetes 2019, 68, 1730–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbertz, P.; Padberg, I.; Rein, D.; Ecker, J.; Höfle, A.S.; Spanier, B.; Daniel, H. Metabolite profiling in plasma and tissues of ob/ob and db/db mice identifies novel markers of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2133–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Holmes, M.V.; Davey Smith, G.; Ala-Korpela, M. Genetic support for a causal role of insulin resistance on circulating branched-chain amino acids and inflammation. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Vijayakumar, A.; White, P.J.; Xu, Y.; Ilkayeva, O.; Lynch, C.J.; Newgard, C.B.; Kahn, B.B. BCAA supplementation in mice with diet-induced obesity alters the metabolome without impairing glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q.; Cao, J.H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, B.D.; Wei, Z.H.; Li, R.; Li, C.Y.; et al. Elevated branched-chain amino acid promotes atherosclerosis progression by enhancing mitochondrial-to-nuclear H(2)O(2)-disulfide HMGB1 in macrophages. Redox Biol. 2023, 62, 102696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Zhao, Y.; Calton, E.K.; James, A.P.; Newsholme, P.; Sherriff, J.; Soares, M.J. The impact of leucine supplementation on body composition and glucose tolerance following energy restriction: an 8-week RCT in adults at risk of the metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 78, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberg, A.; Petzke, K.J.; Klaus, S. Comparison of high-protein diets and leucine supplementation in the prevention of metabolic syndrome and related disorders in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J.; Masaki, T.; Arakawa, M.; Seike, M.; Yoshimatsu, H. Isoleucine prevents the accumulation of tissue triglycerides and upregulates the expression of PPARalpha and uncoupling protein in diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Flores, M.; Cruz, M.; Duran-Reyes, G.; Munguia-Miranda, C.; Loza-Rodríguez, H.; Pulido-Casas, E.; Torres-Ramírez, N.; Gaja-Rodriguez, O.; Kumate, J.; Baiza-Gutman, L.A.; et al. Oral supplementation with glycine reduces oxidative stress in patients with metabolic syndrome, improving their systolic blood pressure. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hafidi, M.; Franco, M.; Ramírez, A.R.; Sosa, J.S.; Flores, J.A.P.; Acosta, O.L.; Salgado, M.C.; Cardoso-Saldaña, G. Glycine increases insulin sensitivity and glutathione biosynthesis and protects against oxidative stress in a model of sucrose-induced insulin resistance. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 2101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.N.; Niu, Y.C.; Sun, X.W.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C.; Wang, C.; Guo, F.C.; Sun, C.H.; Li, Y. Histidine supplementation improves insulin resistance through suppressed inflammation in obese women with the metabolic syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, L.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Xia, F. L.; et al. Phenylalanine promotes liver steatosis by inhibiting BNIP3-mediated mitophagy. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, S.; Poon, S.; Robbins, J.; Bui, M.; Wang, X.; De Groot, L.; Van Loan, M.; Zadeh, A.G.; Nguyen, T.; Seeman, E. Effect of dietary sources of calcium and protein on hip fractures and falls in older adults in residential care: cluster randomised controlled trial. B.M.J 2021, 375, n2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.W.; Seidlitz, E.P.; Singh, G. Glutamate signaling in healthy and diseased bone. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2012, 3, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H.; Yang, R.S.; Tang, C.H.; Wu, M.Y.; Fu, W.M. Regulation of the maturation of osteoblasts and osteoclastogenesis by glutamate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 589, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Dolder, S.; Siegrist, M.; Wetterwald, A.; Hofstetter, W. Glutamate receptor agonists and glutamate transporter antagonists regulate differentiation of osteoblast lineage cells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 99, 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatokun, A.A.; Stone, T.W.; Smith, R.A. Hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1 cells: The effects of glutamate and protection by purines. Bone 2006, 39, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinoi, E.; Takarada, T.; Uno, K.; Inoue, M.; Murafuji, Y.; Yoneda, Y. Glutamate suppresses osteoclastogenesis through the cystine/glutamate antiporter. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blais, A.; Rochefort, G.Y.; Moreau, M.; Calvez, J.; Wu, X.; Matsumoto, H.; Blachier, F. Monosodium glutamate supplementation improves bone status in mice under moderate protein restriction. J.B.M.R. Plus 2019, 3, e10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeds, P.J.; Burrin, D.G.; Jahoor, F.; Wykes, L.; Henry, J.; Frazer, E.M. Enteral glutamate is almost completely metabolized in first pass by the gastrointestinal tract of infant pigs. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 270, E413–E418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeczko, M.J.; Stoll, B.; Chang, X.; Guan, X.; Burrin, D.G. Extensive gut metabolism limits the intestinal absorption of excessive supplemental dietary glutamate loads in infant pigs. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2384–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorres, K.L.; Raines, R.T. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 45, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaugh, V.L.; Mukherjee, K.; Barbul, A. Proline precursors and collagen synthesis: biochemical challenges of nutrient supplementation and wound healing. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtas, S.; Reggiardo, G.; Contu, R.; Cadeddu, M.; Secci, R.; Putzu, P.; Mocco, C.; Leoni, M.; Gigante, Maria V.; Marras, C.; et al. Replacement of the massive amino acid losses induced by hemodialysis: A new treatment option proposal for a largely underestimated issue. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siramolpiwat, S.; Limthanetkul, N.; Pornthisarn, B.; Vilaichone, R.K.; Chonprasertsuk, S.; Bhanthumkomol, P.; Nunanan, P.; Issariyakulkarn, N. Branched-chain amino acids supplementation improves liver frailty index in frail compensated cirrhotic patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Meng, Q.; Zu, C.; Wei, Y.; Su, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, M.; Ye, Z. Dietary low- and high-quality carbohydrate intake and cognitive decline: A prospective cohort study in older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.S.; Yuan, C.; Ascherio, A.; Rosner, B.A.; Blacker, D.; Willett, W.C. Long-term dietary protein intake and subjective cognitive decline in US men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.; Hill, E.; Li, Y.; He, M. Energy and macronutrient intakes at breakfast and cognitive declines in community-dwelling older adults: a 9-year follow-up cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, M.; Fenaroli, F.; Ruocco, C.; Segala, A.; D’Antona, G.; Nisoli, E.; Valerio, A. A balanced formula of essential amino acids promotes brain mitochondrial biogenesis and protects neurons from ischemic insult. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1197208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroudi, W.; Garami, J.; Garrido, S.; Hornberger, M.; Keri, S.; Moustafa, AA. Factors underlying cognitive decline in old age and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of the hippocampus. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 28, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronier, É.; Morici, J.F.; Girardeau, G. The role of the hippocampus in the consolidation of emotional memories during sleep. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheller, M.E.; Vermeylen, F.; Handzlik, M.K.; Gheller, B.J.; Bender, E.; Metallo, C.; Aydemir, T.B.; Smriga, M.; Thalacker-Mercer, AE. Tolerance to graded dosages of histidine supplementation in healthy human adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencharz, P.B.; Elango, R.; Ball, R.O. Determination of the tolerable upper intake level of leucine in adult men. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2220S–2224S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, R.; Rasmussen, B.; Madden, K. Safety and tolerability of leucine supplementation in elderly men. J Nutr. 2016, 146, 2630S–2634S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayamizu, K.; Oshima, I.; Fukuda, Z.; Kuramochi, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Izumo, N.; Nakano, M. Safety assessment of L-lysine oral intake: a systematic review. Amino Acids 2019, 51, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, N.E.; Simbo, S.Y.; Ligthart-Melis, G.C.; Cynober, L.; Smriga, M.; Engelen, MP. Tolerance to increased supplemented dietary intakes of methionine in healthy older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, N.; Matsumoto, H.; Cynober, L.; Stover, P.J.; Elango, R.; Kadowaki, M.; Bier, D.M.; Smriga, M. Subchronic tolerance trials of graded oral supplementation with phenylalanine or serine in healthy adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Miura, N.; Naito, M.; Elango, R. Evaluation of safe utilization of L-threonine for supplementation in healthy adults: a randomized double blind controlled trial. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boirie, Y.; Dangin, M.; Gachon, P.; Vasson, M.P.; Maubois, J.L.; Beaufrère, B. Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1997, 94, 14930–14935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttikhold, J.; van Norren, K.; Buijs, N.; Ankersmit, M.; Heijboer, A.C.; Gootjes, J.; Rijna, H.; van Leeuwen, P.A.; van Loon, L.J. Jejunal casein feeding is followed by more rapid protein digestion and amino acid absorption when compared with gastric feeding in healthy young men. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2033–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, C.; Fukuwatari, T.; Sano, M.; Saito, K.; Sasaki, S.; Shibata, K. Supplementing healthy women with up to 5.0 g/d of L-tryptophan has no adverse effects. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeal, C.J.; Meininger, C.J.; Wilborn, C.D.; Tekwe, C.D.; Wu, G. Safety of dietary supplementation with arginine in adult humans. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.; Hathcock, J.N. Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, L-glutamine and L-arginine. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 50, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Murata, M.; Sumino, A.; Sone, H.; Hayamizu, K. Safety assessment of L-Arg oral intake in healthy subjects: a systematic review of randomized control trials. Amino Acids 2023, 55, 1949–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, L.R.; Hickson, J.F., Jr.; Wolinsky, I.; Pivarnik, J.M. Ornithine supplementation and insulin release in bodybuilders. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1992, 2, 287–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadia, C.; Osowska, S.; Cynober, L.; Forbes, A. Citrulline in health and disease. Review on human studies. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, K.N.; Kang, Y.; Maharaj, A.; Martinez, M.A.; Fischer, S.M.; Figueroa, A. L-Citrulline supplementation attenuates aortic pressure and pressure waves during metaboreflex activation in postmenopausal women. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, N.; Morishita, K.; Yasuda, T.; Akiduki, S.; Matsumoto, H. Subchronic tolerance trials of graded oral supplementation with ornithine hydrochloride or citrulline in healthy adults. Amino Acids 2023, 55, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kuramochi, Y.; Sato, S.; Sakai, R.; Hayamizu, K. Safety assessment of L-ornithine oral intake in healthy subjects: a systematic review. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubuku, S.; Hatayama, K.; Katsumata, T.; Nishimura, N.; Mawatari, K.; Smriga, M.; Kimura, T. Thirteen-week oral toxicity study of branched-chain amino acids in rats. Int. J. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibui, Y.; Manabe, Y.; Kodama, T.; Gonsho, A. 13-week repeated dose toxicity study of l-tyrosine in rats by daily oral administration. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 87, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibui, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Masuzawa, Y.; Ohishi, T.; Fukuwatari, T.; Shibata, K.; Sakai, R. Thirteen week toxicity study of dietary l-tryptophan in rats with a recovery period of 5 weeks. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018, 38, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailliard, M.E.; Stevens, B.R.; Mann, G.E. Amino acid transport by small intestinal, hepatic, and pancreatic epithelia. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 888–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munck, L.K.; Munck, B.G. The rabbit jejunal ‘imino carrier’ and the ileal ‘imino acid carrier’ describe the same epithelial function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1116, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soultoukis, G.A.; Partridge, L. Dietary protein, metabolism, and aging. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016, 85, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indispensable AA Requirements Usual Consumption |

| (mg/kg body weight/day) |

| FNB/IOM1 WHO2 AFSSA3 FNB/IOM4 NMCD5 |

| Histidine 11 10 11 31 28 |

| Isoleucine 15 20 18 51 45 |

| Leucine 34 39 39 87 80 |

| Lysine 31 30 30 75 71 |

| Methionine 10a 10 15b 25 23 |

| Phenylalanine 27c 25c 27d 49 46 |

| Threonine 16 15 16 43 40 |

| Tryptophan 4 4 4 13 11 |

| Valine 19 26 18 57 54 |

| Amino acids NOAEL values (g/day) References |

| Histidine 8.0 Gheller et al. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020 |

| Lysine 6.0 Hayamizu et al. Amino Acids 2019 |

| Methionine 3.2 Deutz et al. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017 |

| Phenylalanine 12.0 Miura et al. Nutrients 2021 |

| Threonine 12.0 Matsumoto et al. Amino Acids 2025 |

| Tryptophan 5.0 Hiratsuka et al. J. Nutr. 2013 |

| Arginine 7.5-20 Kuramochi et al. Amino Acids 2023, Shao et al. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008 |

| Serine 12.0 Miura et al. Nutrients 2021 |

| Ornithine 12.0 Miura et al. Amino Acids 2023, Yang et al. Amino Acids 2025 |

| Citrulline 24.0 Miura et al. Amino Acids 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).