1. Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an acute inflammatory disease of the pancreas that may result in local pancreatic injury, systemic inflammatory response, and organ failure [

1]. It represents one of the most common gastrointestinal emergencies with an unpredictable clinical course and uncertain outcomes [

2].

The global incidence of AP ranges from 4.9 to 73.4 cases per 100,000 population, with a rising trend worldwide [

3,

4]. The incidence varies across Europe: it is lower in England, the Netherlands, and Croatia, moderate in Germany and Scotland, and highest in Finland and Poland, largely related to high alcohol consumption [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Overall mortality in AP is about 5%, but rises to 10–30% in severe forms, and in some studies reaches up to 50% [

9,

10]. The most frequent causes are gallstone disease and alcohol abuse, followed by hyperlipidemia, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), pancreatic neoplasms, certain drugs, metabolic disorders, hereditary syndromes, and idiopathic forms [

1,

11,

12].

The diagnosis of AP is established if at least two of the following three requirements have been met: abdominal pain, three-fold increase of the pancreatic amylase and/or lipase values with respect to the upper reference limit and a positive finding on the contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or, magnetic resonance (MR) or transabdominal ultrasonography (US) [

4]. Upon diagnosis establishment, it is very important to assess the severity of the disease and the treatment outcome. According to the Atlanta classification from 2012, there are three grades of this disease: mild, moderate and severe AP [

8,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Early mortality is most often due to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ failure (MOF), while late mortality is related to sepsis from infected pancreatic necrosis [

17].

The aim of this study was to identify simple and objective predictors of early and one-year mortality in patients with AP, and to evaluate the discriminative ability of commonly used scoring systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted at the ICU University Hospital Center Bežanijska Kosa, Belgrade. The research was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee and management of the University Hospital Center Bezanijska Kosa which is responsible for educational, scientific and research activities. Number 3442/3 date 10.05.2018.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant patients

Presence of chronic pancreatitis

Occurrence of AP following a multiple trauma episode

Patients who were admitted to the University Hospital Center Bežanijska Kosa from another healthcare facility, and more than 48 hours had passed since the diagnosis of acute pneumonia (AP)

Having history of organ transplant.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical data

Etiology of AP

Laboratory parameters (CRP, PCT, routine biochemistry)

Imaging (US, CT, MRI)

Severity scores: Ranson, Pancreas Score, APACHE II, BISAP, MEWS

Study protocol

Scores were calculated at admission (day 0), at 48–72 h, and on day 7. Outcomes were assessed at discharge and at 12 months by direct patient/family contact.

Endpoints

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test, Chi-square, Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis, ANOVA, Spearman rank correlation, and Cox regression were applied. Significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

A total of 50 patients were included (52% male, 48% female). The overall mortality rate was 16%. No significant differences were observed between survivors and non-survivors regarding sex, pancreatic necrosis, or total length of hospitalization. Mortality was significantly associated with: presence of sepsis/septic shock (p<0.001), longer duration of mechanical ventilation (p<0.001), prolonged ICU stay (p=0.018) and severe AP (p=0.001). (

Table 1.)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with acute pancreatitis in relation to outcome.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with acute pancreatitis in relation to outcome.

| Characteristic |

Total n=50 |

Survivors n=42 (84%) |

Non-survivors n=8 (16%) |

p |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

| Male |

26 (52.0) |

22 (52.4) |

4 (50.0) |

0.902 |

| Female |

24 (48.0) |

20 (47.6) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| Etiology |

|

|

|

|

| Gallstones |

30 (60.0) |

26 (61.9) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Hyperlipidemia |

8 (16.0) |

6 (14.3) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| Alcohol abuse |

4 (8.0) |

4 (9.5) |

0 (0) |

|

| Unknown |

8 (16.0) |

6 (14.3) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| Necrosis |

|

|

|

0.902 |

| Present |

24 (48.0) |

20 (47.6) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| Absent |

26 (52.0) |

22 (52.4) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| Complications |

|

|

|

<0.001* |

| Without complications |

22 (44.0) |

22 (52.4) |

0 (0) |

|

| Pleural effusion |

18 (36.0) |

16 (38.1) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| Sepsis / septic shock |

10 (20.0) |

4 (9.5) |

6 (75.0) |

|

| BMI |

|

|

|

|

| Normal weight |

17 (40.5) |

17 (40.5) |

0 (0) |

|

| Overweight |

24 (47.6) |

20 (47.6) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| Obesity |

8 (16.0) |

5 (11.9) |

3 (37.5) |

|

| Morbid obesity |

1 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (12.5) |

|

| Duration of MV (days), median (range) |

0 (0–20) |

0 (0–2) |

4.5 (0–20) |

<0.001* |

| Duration of ICU stay (days), median (range) |

2 (0–20) |

1.5 (0–20) |

3.0 (0–3) |

0.018* |

| Length of hospitalization (days), median (range) |

15 (6–62) |

12.5 (6–62) |

17.5 (9–27) |

0.183 |

| Form of pancreatitis |

|

|

|

0.001* |

| Mild |

20 (40.0) |

18 (42.9) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| Moderately severe |

20 (40.0) |

19 (45.2) |

1 (12.5) |

|

| Severe |

10 (20.0) |

5 (11.9) |

5 (62.5) |

|

Table 2.

Predictive value of severity scores and biomarkers in acute pancreatitis.

Table 2.

Predictive value of severity scores and biomarkers in acute pancreatitis.

| Parameter |

AUROC |

95% CI |

Cut-off |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Day 0

(at admission)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ranson (0h) |

0.693 |

0.547–0.816 |

≤2.0 |

59.5 |

87.5 |

| APACHE II (0h) |

0.813 |

0.677–0.909 |

≤15.0 |

69.0 |

87.5 |

| Pancreas (0h) |

0.695 |

0.549–0.817 |

≤2.0 |

50.0 |

87.5 |

| BISAP (0h) |

0.807 |

0.670–0.905 |

≤2.0 |

69.0 |

87.5 |

| CRP (0h) |

0.753 |

0.611–0.864 |

≤46.3 |

64.3 |

87.5 |

| PCT (0h) |

0.580 |

0.432–0.718 |

≤0.3 |

66.7 |

75.0 |

| 48 hours after admission |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ranson (48h) |

0.856 |

0.727–0.939 |

≤5.0 |

92.9 |

87.5 |

| APACHE II (48h) |

0.917 |

0.803–0.976 |

≤17.0 |

90.5 |

87.5 |

| Pancreas (48h) |

0.729 |

0.585–0.845 |

≤2.0 |

57.1 |

87.5 |

| BISAP (48h) |

0.789 |

0.650–0.891 |

≤2.0 |

69.0 |

87.5 |

| CRP (48h) |

0.667 |

0.519–0.794 |

≤183.2 |

90.5 |

50.0 |

| PCT (48h) |

0.545 |

0.398–0.686 |

≤2.1 |

97.6 |

37.5 |

The present analysis demonstrates that clinical scoring systems, particularly APACHE II and Ranson scores, provide the most reliable prediction of outcome in acute pancreatitis. At admission, APACHE II and BISAP scores showed good discriminative ability, with AUROC values above 0.80, confirming their utility as early prognostic tools. In contrast, serum biomarkers such as CRP and PCT demonstrated only moderate accuracy, with procalcitonin performing poorly at baseline.

Reassessment at 48 hours markedly improved prognostic accuracy. The APACHE II score achieved excellent predictive value (AUROC 0.917) with both high sensitivity and specificity, while the Ranson score also showed strong performance (AUROC 0.856). Although BISAP maintained acceptable accuracy, it was less powerful than APACHE II and Ranson at this time point. Among biomarkers, CRP showed only modest accuracy, whereas PCT achieved very high sensitivity but lacked specificity, making it unsuitable as a standalone marker.

These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that dynamic scoring systems, which incorporate evolving physiological and clinical data, outperform static biochemical markers in predicting severity and mortality in acute pancreatitis. In clinical practice, early use of APACHE II or BISAP at admission may help in risk stratification, but repeated evaluation at 48 hours with APACHE II or Ranson scores provides the most reliable prognostic information for guiding intensive management strategie.

Table 3.

Association of severity scores with final outcome in acute pancreatitis.

Table 3.

Association of severity scores with final outcome in acute pancreatitis.

| Score / Time |

Category |

Total n (%) |

Survivors n (%) |

Non-survivors n (%) |

p |

| Ranson (0h) |

3–4 |

25 (50.0) |

17 (40.5) |

8 (100.0) |

0.002* |

| Ranson (48h) |

3–4 |

16 (32.0) |

16 (38.1) |

0 (0) |

|

| |

>5 |

21 (42.0) |

13 (31.0) |

8 (100.0) |

0.0012* |

| Pancreas (0h) |

3–8(high risk for severe AP) |

29 (58.0) |

21 (50.0) |

8 (100.0) |

0.009* |

| Pancreas (48h) |

3–8 |

27 (54.0) |

19 (45.2) |

8 (100.0) |

0.004* |

| APACHE II (0h) |

10–19 |

32 (64.0) |

28 (66.7) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| |

20–29 |

10 (20.0) |

6 (14.3) |

4 (50.0) |

0.021* |

| APACHE II (48h) |

10–19 |

32 (64.0) |

30 (71.4) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| |

20–29 |

10 (20.0) |

4 (9.5) |

6 (75.0) |

<0.001* |

| BISAP (0h) |

3–4 |

17 (34.0) |

11 (26.2) |

6 (75.0) |

0.008* |

| |

5 |

4 (8.0) |

2 (4.8) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| BISAP (48h) |

3–4 |

11 (22.0) |

9 (21.4) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| |

5 |

10 (20.0) |

4 (9.5) |

6 (75.0) |

0.002* |

| BISAP (72h) |

3–4 |

8 (16.0) |

4 (9.5) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| |

5 |

8 (16.0) |

4 (9.5) |

4 (50.0) |

|

| BISAP (7d) |

3–4 |

8 (17.4) |

4 (10.5) |

2 (25.0) |

|

| |

5 |

8 (17.4) |

4 (10.5) |

4 (50.0) |

<0.001* |

Scores of 3–4 on Ranson at admission were significantly associated with mortality (p=0.002). Scores >5 at 48 hours were highly predictive of death (p=0.0012). Pancreas scores between 3–8 at both time points correlated significantly with mortality (p=0.009 and p=0.004). Higher APACHE II scores (20–29) at baseline and 48h predicted mortality, with a stronger association at 48h (p<0.001). BISAP scores ≥3 at admission and ≥5 at 48h, 72h, and 7 days showed strong correlation with mortality, especially at 48h and 7 days (p=0.002–<0.001). Dynamic evaluation of severity scores, particularly APACHE II and BISAP during the initial 48 hours, provides reliable prediction of mortality, aiding clinical decision-making.

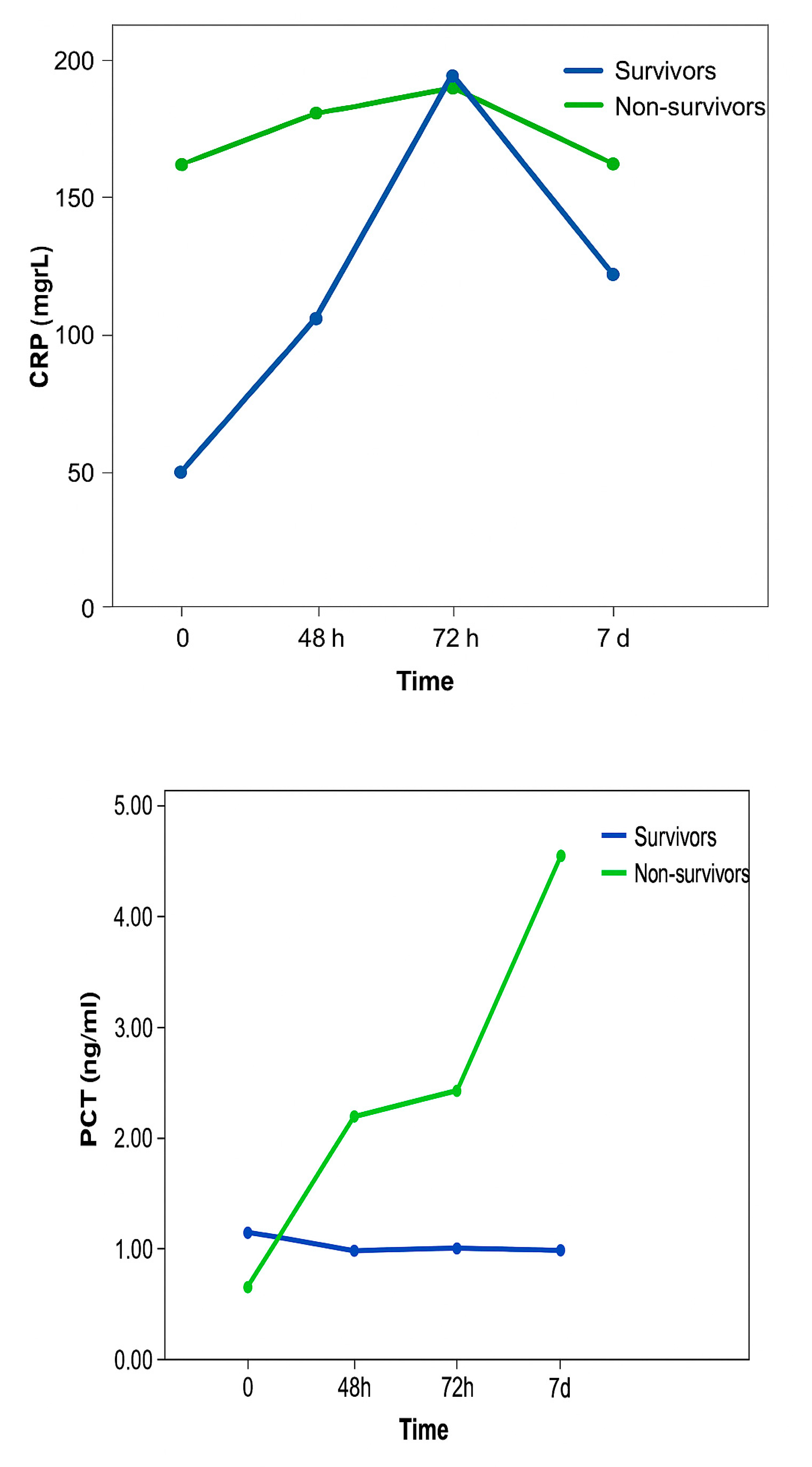

Figure 1.

CRP and PCT values between patients with fatal outcomes and patients who survived, and the relationship of CRP values over the observed time.

Figure 1.

CRP and PCT values between patients with fatal outcomes and patients who survived, and the relationship of CRP values over the observed time.

CRP values did not differ statistically significantly between patients with a fatal outcome and patients who survived. In patients who survived, there was a constant sharp increase in CRP values, which reached a maximum after 72 hours and then a decline was recorded. In patients with a fatal outcome, there were smaller oscillations between measurements, but the values were significantly higher compared to CRP values in patients who survived. The change in CRP values was not statistically significantly different in the observed time in both groups of patients.

PCT values were statistically significantly higher in patients with a fatal outcome compared to patients who survived. Also, PCT values differed statistically significantly over the observed time. Namely, over the examined time there was a statistically significant linear trend of PCT value growth, without significant differences in PCT values between individual measurements. Changes in PCT values did not differ statistically significantly over the observed time in both groups of patients.

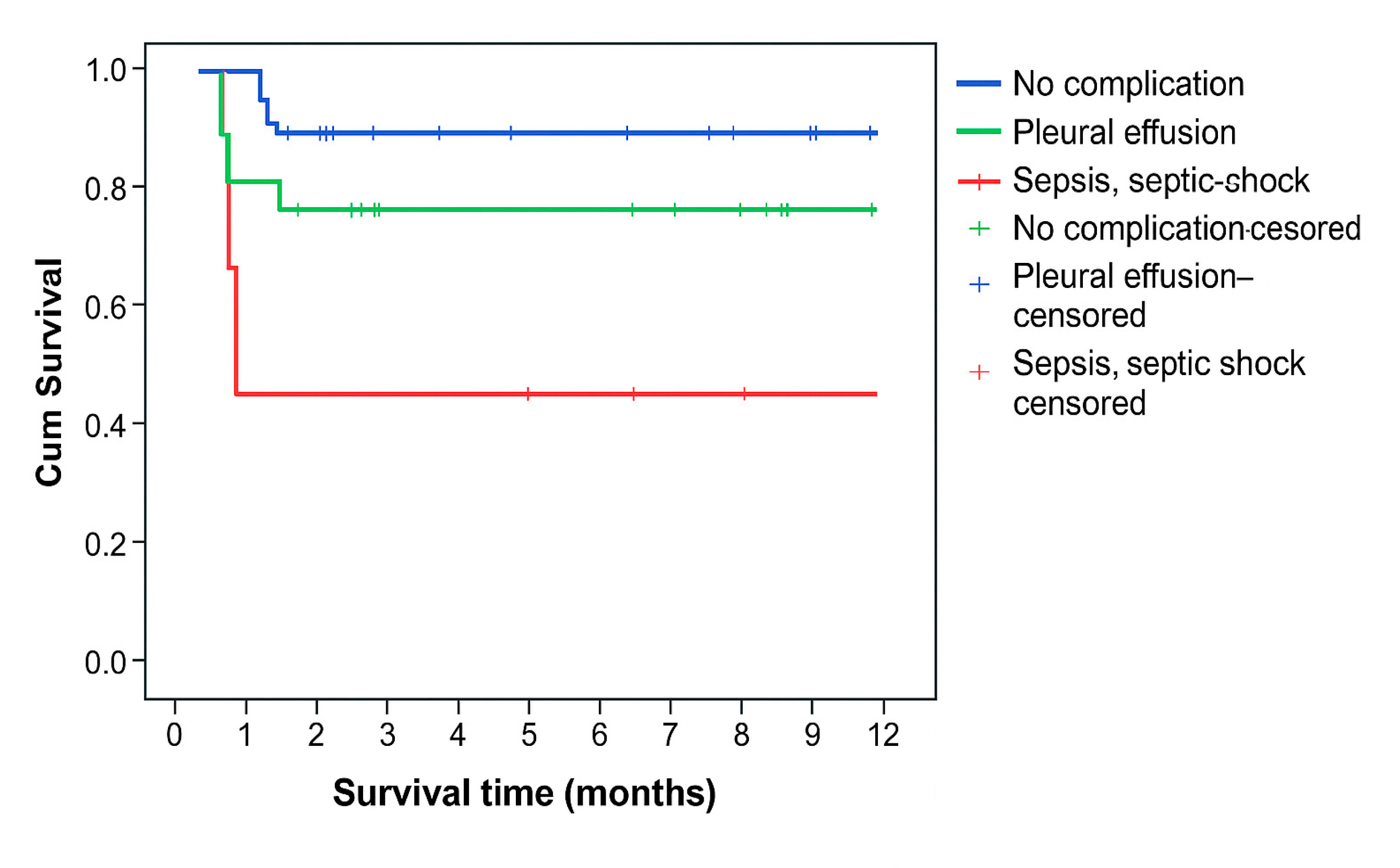

Survival time was statistically significantly shorter in patients who had sepsis or septic shock as a complication (p=0.023) (

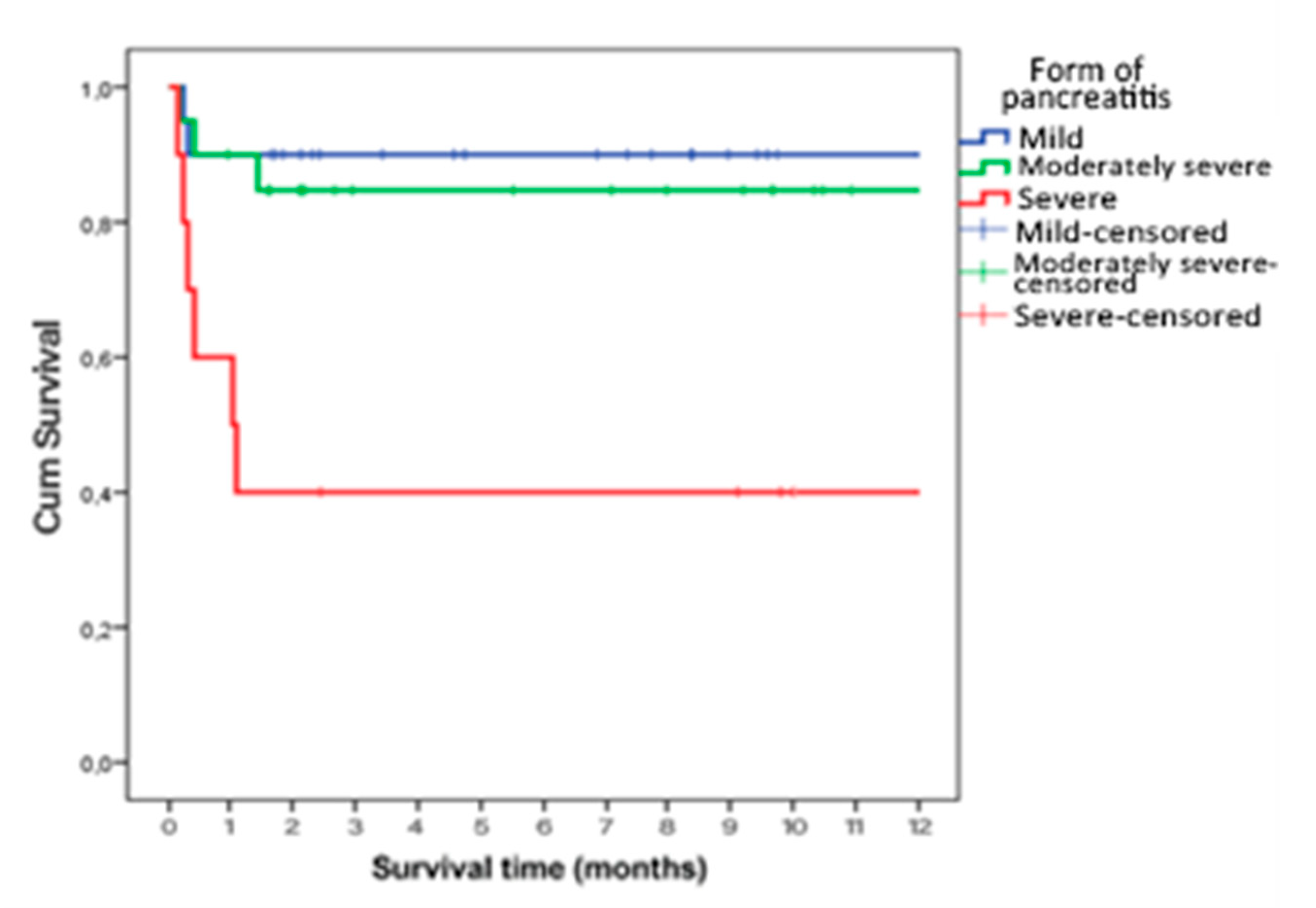

Figure 2), who had severe AP (p=0.002) (

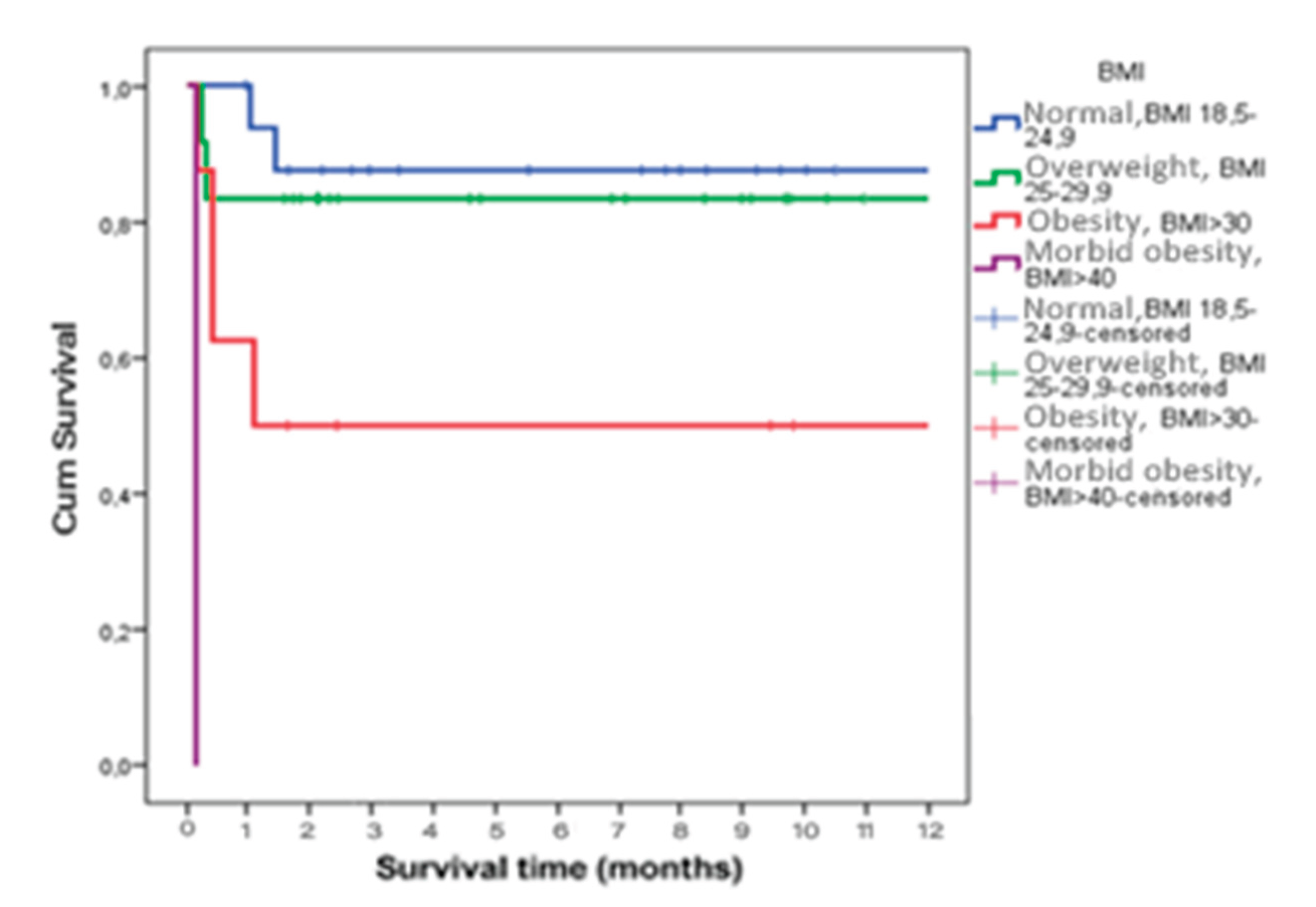

Figure 3) and who were obese (p<0.001) (

Figure 4).

Table 4 presents the results of the Cox regression analysis for different severity scoring systems in acute pancreatitis. The BISAP score demonstrated a consistent and statistically significant association with mortality at all time points (0h, 48h, 72h, 7d), with each 1-point increase being associated with an almost twofold increase in the risk of death (HR 1.70–1.95, p < 0.01).

The Ranson score was not a significant predictor at admission (p = 0.078), but became a strong and independent predictor of mortality after 48 hours (HR 2.21, p < 0.001).

The APACHE score was already significant at admission (HR 1.22, p = 0.001), and its predictive strength further increased at 48 hours (HR 1.36, p < 0.001).

The Pancreas score showed a significant association with mortality at admission (HR 1.84, p = 0.017), while this association was no longer statistically significant at 48 hours (p = 0.105).

Table 5 presents the results of the Cox regression analysis for CRP, PCT, duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU stay, and total length of hospitalization.

CRP levels during the first 72 hours were not significant predictors of mortality, whereas after 7 days a statistically significant but modest association with poor outcome was observed. In contrast, PCT emerged as a strong and consistent predictor of mortality from 48 hours onwards, with higher values significantly increasing the risk of death. That means that PCT has greater prognostic value than CRP in predicting mortality among patients with acute pancreatitis, particularly after 48 hours of hospitalization.

Among clinical parameters, prolonged mechanical ventilation and longer ICU stay were identified as independent predictors of mortality. In contrast, the overall length of hospitalization showed no statistically significant association with survival.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated predictive factors of early and one-year mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis (AP). Acute pancreatitis (AP) remains a clinically heterogeneous disease, ranging from mild localized inflammation to severe forms involving multiple organ systems [

18]. Approximately 15 to 25 percent of all patients with acute pancreatitis (AP) develop moderately severe or severe AP. Although 95% to 98% of patients survive the disease, it is still one of the leading causes of death among patients hospitalized with gastrointestinal disorders in the United States and Europe. [

19]. About 50% of deaths occur within the first 2 weeks of the disease and early death is usually associated with persistent multiple organ failure (MOF) [

10,

20]. Organ failure in AP is associated with up to 30% mortality rates [

21].

In our study, overall mortality was 16%, with the majority of deaths occurring in patients with severe AP and those who developed complications such as sepsis or septic shock. Most patients with a fatal outcome (62.5%) had a severe form of AP. Pancreatic necrosis was present in 48% of patients compared to the total number of patients studied and 50% compared to the number of patients with a severe form of AP, but this was not statistically significant in relation to the outcome of treatment. Complications such as sepsis and septic shock were statistically significantly more common in patients with a fatal outcome compared to the survivor group.

Our findings confirm that systemic complications, particularly sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ failure (MOF), remain the main determinants of early mortality, whereas infection of necrotic pancreatic tissue is strongly associated with late mortality. These observations are consistent with prior studies, which emphasize that mortality in AP follows a biphasic pattern: early deaths due to overwhelming systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction, and late deaths linked to septic complications [

9,

17,

21].

Consistent with previous literature, gallstones and alcohol abuse were the leading etiologies of AP in our cohort, although the relative distribution differed slightly between sexes. Hyperlipidemia, increasingly reported in Asian populations, was identified as the predominant cause in large Chinese cohorts [

22]. Obesity and overweight were common in our population, with 47.6% of patients exceeding normal body weight. Importantly, obese patients demonstrated significantly shorter one-year survival, highlighting the role of excess body weight as a risk factor for severe AP and associated mortality [

23].

Several clinical scoring systems are widely used to predict severity and mortality in AP. In our cohort:

BISAP score consistently predicted mortality at all time points (0h, 48h, 72h, 7d), with each point increase nearly doubling the risk of death. This aligns with evidence demonstrating its comparable or superior accuracy relative to APACHE II and Ranson scores [

24,

25].

APACHE II showed high predictive value already at admission, improving at 48 hours, consistent with its established role in identifying patients requiring intensive care and early resuscitation [

26].

Ranson score was not predictive at admission but became a reliable predictor after 48 hours, reflecting its calculation requirements and delayed application [

27].

Pancreas score demonstrated significant prognostic value at admission but lost statistical significance after 48 hours, suggesting limited utility for longer-term risk stratification [

28].

These results underscore that different scoring systems have optimal predictive performance at different time points during hospitalization. Early use of BISAP and APACHE II can guide immediate triage decisions, whereas Ranson and Pancreas scores may provide more relevant information after the first 48 hours. Analysis of one-year survival revealed that the APACHE II and Ranson scoring system are a statistically significant predictor of mortality. The degree of calibration of the Pancreas0 scoring system in terms of treatment outcome was quite high, immediately after the BISAP0 scoreand proved to be a significant predictor of one-year survival.

C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) remain valuable adjuncts in prognostic evaluation. In our study, CRP measured at day 7 was a significant predictor of one-year mortality, while PCT values at 48h, 72h, and day 7 strongly correlated with mortality. Previous studies report that CRP ≥150 mg/L at 48 hours distinguishes severe from mild AP with good sensitivity and specificity [

27], while PCT is particularly sensitive for detecting early organ dysfunction and multi-organ failure [

29,

30]. Although initial CRP measurements may better predict mortality than initial PCT, monitoring the dynamic trends of both biomarkers offers additional prognostic information, with CRP reflecting disease severity and PCT providing early sensitivity to systemic complications [

31]. However, it has also been proved that in order to predict the progression of AP the initial PCT values were less accurate than the Ranson and BISAP scores, which showed significantly better correlation [

32]. Most guidelines on AP advise against the use of a single marker to triage patients [

27]. In our research, after 48 hours, both inflammatory biomarkers had lower prognostic value for treatment outcome compared to scoring systems [

34] . We have proven in our research that PCT, in combination with clinical indicators of treatment intensity, may serve as a reliable marker for risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

Therefore, while clinical scoring systems are most useful at the time of admission, biomarkers may provide incremental value during the early hospital course, particularly in guiding decisions about antibiotic therapy and invasive interventions. [

17].

Our study also confirmed that prolonged need for mechanical ventilation and extended intensive care unit (ICU) stay are strongly associated with mortality. This finding underscores the importance of timely escalation of care, as patients requiring prolonged organ support represent the subgroup at highest risk of death. Previous studies have shown that the presence of persistent organ failure beyond 48 hours is the single strongest predictor of mortality [

10,

13,

34].

One-year survival was significantly shorter among patients with sepsis, septic shock, severe AP, and prolonged ICU stay. These findings are consistent with prior reports highlighting age, comorbidities, diabetes, elevated CRP on admission, pleural effusions, pancreatic necrosis, and systemic complications as independent risk factors for reduced long-term survival [

35]. Importantly, etiology influenced short-term outcomes but appeared less relevant for long-term survival. Some studies have found that higher scores on the scoring system (Ransonov, Pancreas, BISAP) and longer ICU stay may be predictors of mortality and long-term survival in univariate but not multivariate analyses. [

35,

36].

Clinical implications

Our findings support a multimodal approach for risk stratification in AP, integrating clinical scoring systems with inflammatory biomarkers. Early identification of high-risk patients can guide intensive monitoring, prompt intervention, and appropriate allocation of resources. While scoring systems such as BISAP and APACHE II provide robust early prediction, Ranson and Pancreas scores remain useful for ongoing assessment, and serial CRP and PCT measurements offer additional insights into disease progression [

24].

Limitations

This study is limited by its single-center design and relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of results. Larger, multicenter studies are warranted to validate these findings and explore the utility of emerging machine learning models, which have demonstrated superior predictive accuracy in recent investigations [

37].

5. Conclusions

Dynamic assessment using APACHE II and BISAP within the first 48 hours provides reliable mortality prediction in acute pancreatitis. Ranson and Pancreas scores offer complementary prognostic information. Serial PCT measurement is a sensitive early predictor, whereas CRP trends contribute to the evaluation of disease progression. Integrating these tools allows for effective risk stratification, targeted intervention, and improved patient management in both short- and long-term outcomes [

36].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. (Ana Sekulic) and O.M.; methodology, A.S. (Ana Sekulic), O.M. and N.N.; software, S.T. and A.P.; validation, D.Z. (Darko Zdravkovic), formal analysis, A.S. (Ana Sekulic), O.M., T.A. and J.G.; investigation, A.S. (Ana Sekulic), O.M., I.N., S.G. and B.L.; S.N., V.P., and B.L.; data curation, A.S. (Ana Sekulic) and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. (Ana Sekulic), O.M. and S.T. writing—review and editing, D.Z. and A.P.; supervision, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Medical Center Bezanijska Kosa (protocol number 3442/3 date 10.05.2018.).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (A.S.) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AP |

Acute pancreatitis |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| MV |

Mechanical ventilation |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| APACHE II |

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score |

| BISAP |

Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| PCT |

Procalcitonin |

References

- Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1096–1101. PMID: 29409760. [CrossRef]

- Bezmarević M, Micković S, Lekovski V, i sar. Akutni pankreatitis: procena težine i ishoda. Timočki medicinski glasnik. 2011;36(3):93–102. ISSN 0350-2899.

- Fagenholz PJ, Castillo CF, Harris NS, et al. Increasing United States hospital admissions for acute pancreatitis, 1988–2003. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):491–497. PMID: 17448682. [CrossRef]

- Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33(4):323–330. PMID: 17079934. [CrossRef]

- Štimac D, Mikolasevic I, Krznaric-Zrnic I, et al. Epidemiology of acute pancreatitis in the North Adriatic region of Croatia during the last ten years. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:956149. PMID: 23476641. PMCID: PMC3586513. [CrossRef]

- Jakkola M, Nordback I. Pancreatitis in Finland between 1970 and 1989. Gut. 1993;34(9):1255–1260. PMCID: PMC1375465. PMID: 8406164. [CrossRef]

- Sand J, Välikoski A, Nordback I. The incidence of acute alcoholic pancreatitis follows the change in alcohol consumption in Finland. Pancreatology. 2006;6(3):323–405.

- UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 3):iii1–iii9. [CrossRef]

- American College of Gastroenterology. Management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400–1415. PMID: 23896955. [CrossRef]

- Nesvaderani M, Eslick GD, Vagg D, et al. Epidemiology, aetiology and outcomes of acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;23:68–74. PMID: 26384834. [CrossRef]

- Conti Bellocchi MC, Campagnola P, Frulloni L. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis. Pancreapedia. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Parenti DM, Steinberg W, Kang P. Infectious causes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996;13(4):356–371. PMID: 8899796 . [CrossRef]

- Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379–2400. PMID: 17032204. [CrossRef]

- Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, et al. IAP Guidelines for the surgical management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2(6):565–573. PMID: 12435871. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, De Maertelaere V, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(3):715–723. PMID: 14988825. [CrossRef]

- Bollen TL, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et al. Update on acute pancreatitis: ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging features. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2007;28(5):371–383.

- Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, et al. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):813–820. PMID: 20540942. [CrossRef]

- Madhu PC, Reddy DV. A comparison of the Ranson score and serum procalcitonin for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Int J Sci Res (IJSR). 2016;5(11):1308–1313. ISSN: 2319-7064.

- Vege SS. Predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. UpToDate. 2025.

- Johnson C, Lévy P. Detection of gallstones in acute pancreatitis: when and how? Pancreatology. 2010;10(1):27–32. PMID: 20299820. [CrossRef]

- Husu HL, Leppäniemi AK, Lehtonen TM, Puolakkainen PA, Mentula PJ. Short- and long-term survival after severe acute pancreatitis: a retrospective 17 years’ cohort study. J Crit Care. 2019;53:81–86.

- Zhu Y, Pan X, Zeng H, et al. A study on the etiology, severity, and mortality of 3260 patients with acute pancreatitis according to the revised Atlanta classification in Jiangxi, China over an 8-year period. Pancreas. 2017;46(4):504–509. PMID: 28196012. [CrossRef]

- Kim HG, Han J. Obesity and pancreatic diseases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59(1):35–39. PMID: 22289952. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Vaz P, Abrantes AM, Castelo-Branco M, et al. Multifactorial scores and biomarkers of prognosis of acute pancreatitis: applications to research and practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(1):338.

- Papachristou GI, et al. Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications, and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):435–441.

- Kumar HA, Singh GM. A comparison of APACHE II, BISAP, Ranson’s score and modified CTSI in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2018;6(2):127–131.

- Lee DW, Cho CM. Predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(6):787.

- Mounzer R, et al. Comparison of existing clinical scoring systems to predict persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1476–1482.

- Kylänpää-Bäck ML, Takala A, Kemppainen E, Puolakkainen P, Haapiainen K, Repo H. Procalcitonin strip test in the early detection of severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2001;88(2):222–227.

- Modrau IS, Floyd AK, Thorlacius-Ussing O. The clinical value of procalcitonin in early assessment of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(7):1593–1597.

- Komolafe O, Pereira SP, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS. Serum C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and lactate dehydrogenase for the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD012645.

- Taylor SL, Morgan DL, Denson KD, et al. A comparison of the Ranson, Glasgow, and APACHE II scoring systems to a multiple organ system score in predicting patient outcome in pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189(2):219–222.

- Kim BG, Noh MN, Ryu CH, et al. A comparison of the BISAP score and serum procalcitonin for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28(3):322–329.

- Blum T, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, et al. Fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis: its occurrence and early prediction. Pancreatology. 2001;1(3):237–241. PMID: 12120201. [CrossRef]

- Czapári D. Post-discharge mortality in acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(4):682–695.

- Giorga A, Hughes M, Parker S, Smith A, Young A. Quality of life after severe acute pancreatitis: systematic review. BJS Open. 2023;7(4):zrad067. [CrossRef]

- Halonen KI, Leppäniemi AK, Lundin JE, et al. Predicting fatal outcome in the early phase of severe acute pancreatitis by using novel prognostic models. Pancreatology. 2003;3(4):309–315.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).