1. Introduction

Adequate immobilization of the spine in severely injured patients is a key component of acute care and aims to prevent secondary neurological injury, particularly in the cervical spine (C-spine). Approximately 10% of all polytrauma cases involve C-spine injuries. The leading causes are road traffic collisions (50%), followed by falls (30%). Age peaks occur among young adults (20–29 years) and older individuals (>60 years), the latter mainly due to age-related falls (Noonan 2012).

In Germany, roughly 1,600 people per year sustain traumatic spinal cord injury, about 600 of them involving the cervical region. The consequences of spinal cord injury are far-reaching—physical, psychological, and economic—with lifelong impact on patients and the healthcare system.

The first 24 hours after trauma are decisive for neurological outcome. An essential part of prehospital identification of spinal injury is history taking, including a precise description of the mechanism of injury. According to the S3 guideline on polytrauma/severely injured patients (hereinafter referred to as the S3 guideline), a targeted physical examination of the spine should already be performed prehospital. If spinal injury is suspected, the S3 guideline recommends immediate immobilization, particularly of the C-spine. In unconscious patients, a spinal injury must be assumed until proven otherwise.

A variety of immobilization tools are used in prehospital and in-hospital practice (

Figure 1).

Immobilization tools in clinical use:

- a)

Cervical collar. The evidence base is heterogeneous. The collar primarily serves C-spine immobilization and is often used in combination with whole-body devices. Potential adverse effects such as increased intracranial pressure or impeded airway access are discussed (Hood & Considine 2015; Goutcher & Lochhead 2005). Some studies question clinical benefit when whole-body immobilization is intact (Hauswald et al. 1998; Haut et al. 2010).

- b)

Long spine board. A prehospital mainstay with straps and head blocks, providing stable fixation and frequently used for in-hospital transport and positioning of trauma patients (Luscombe & Williams 2003; Gather 2020). As no superiority over the vacuum mattress has been proven and strap-related soft-tissue pressure increases the risk of pressure injury, in-hospital use is increasingly viewed critically (Pernik 2016).

- c)

Vacuum mattress. The S3 guideline recommends it as the standard procedure when spinal injury is suspected, including in-hospital. Its anatomical conformity enables good immobilization with low motion scores; however, handling can be cumbersome in a hectic trauma-room environment (Kornhall et al. 2017; Prasarn et al. 2017).

- d)

TraumaMattress. Enables rapid stabilization and safe in-hospital transport of trauma patients without requiring repacking. It reduces unintended movements, improves patient safety, and spares the patient (Gather 2020; Nolte et al. 2021). It is suitable for radiography and CT without relevant imaging artifacts.

- e)

Recent developments. Foldable systems, modular positioning aids, and electronic monitoring using inclinometer systems are increasingly discussed and may contribute to individualized, objective stabilization in the future. Corresponding approaches are currently in development or early testing (Benger & Blackham 2009).

Differences in training and experience of clinical staff, as well as structural conditions—such as availability of positioning aids or spatial constraints in the trauma room—can influence the choice of immobilization method (Wnent 2023; Häske et al. 2024).

Whereas the prehospital phase is guided by evidence-based recommendations—such as the use of cervical collar and vacuum mattress—per the S3 guideline (German Society for Trauma Surgery 2023), standardized approaches for the in-hospital phase are still lacking. The in-hospital phase is not merely a continuation of prehospital care but a distinct, highly dynamic environment. The period between arrival in the trauma room and completion of imaging is particularly critical, as clinical transition with multiple transfers, diagnostic imaging, and OR preparation constitutes a vulnerable window in which unstable injuries may deteriorate (Gather 2020; Middleton et al. 2014). During this transition, the risk of secondary injury due to insufficient spinal immobilization is high—especially where standardized procedures are not established (Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2021; Maschmann et al. 2019).

The first 24 hours after trauma are particularly decisive for neurological outcome (Gather 2020). Early, adequate immobilization substantially affects the clinical course—both in terms of mortality and secondary complications. Nevertheless, evidence-based in-hospital recommendations for immobilization remain scarce. The S3 guideline refers to “common precautions,” such as positioning on a vacuum mattress, but does not provide a concrete standardized protocol for the trauma room. This lack of clarity allows heterogeneity in clinical care, potentially affecting immobilization quality and the risk of secondary injury.

The aim of this article is to compare the effectiveness of different immobilization tools with respect to C-spine stability during the in-hospital phase. Building on experimental motion analyses, we seek to contribute to the development of standardized in-hospital care strategies. The focus is on practice-relevant insights for daily work in the trauma room and adjacent clinical areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cervical Spine Motion Analysis During Immobilization

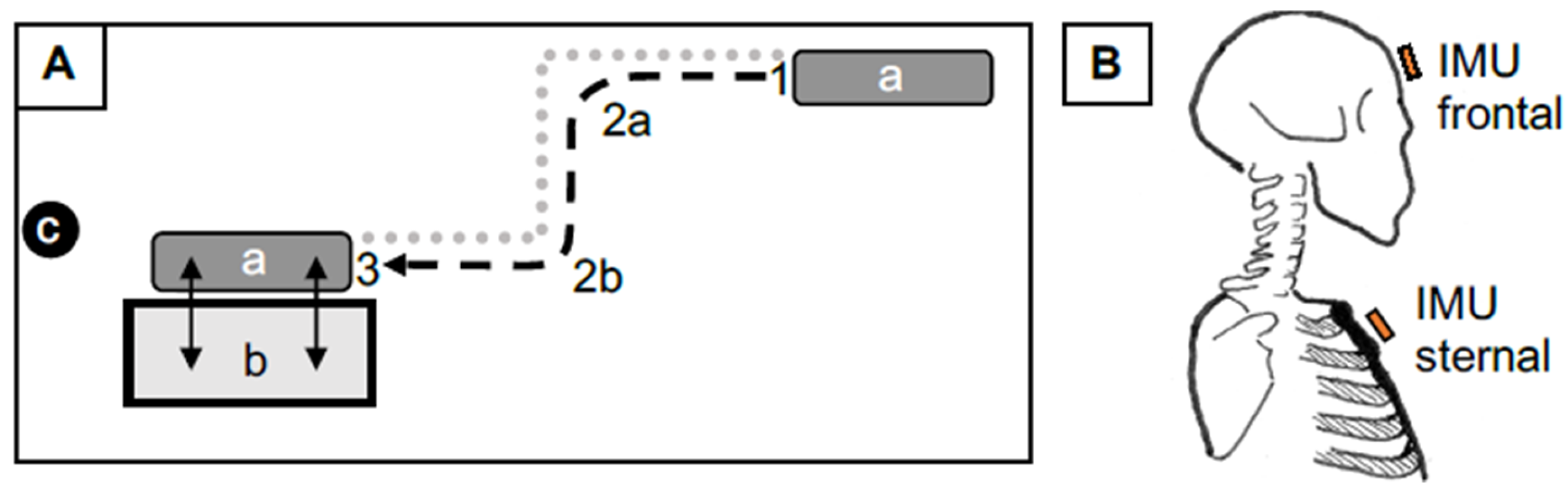

To analyze cervical spine (C-spine) motion across different immobilization devices, a wireless human motion tracker (Xsens Technologies® MTi 10) was used. Two inertial measurement units (IMUs) recorded angular deviations in all three planes (flexion/extension, rotation, lateral flexion) (

Figure 2). Measurements were performed within a standardized trauma-room scenario simulating patient transport on a stretcher, including defined curve driving and two sequential transfers onto and off an examination table. Each measurement was video-documented to ensure reproducibility and allow verification of potential artifacts (

Figure 2).

2.2. Experimental Arms and Devices

Four commonly used whole-body immobilization devices were compared: a long spine board (with straps/head blocks), a soft positioning mattress, the TraumaMattress (with T-Fix head fixation), and a vacuum mattress. In all experimental arms, a cervical collar was applied to reflect clinical practice (

Figure 1). Repeated runs were performed per device (n = 7); mean values are summarized in

Table 1.

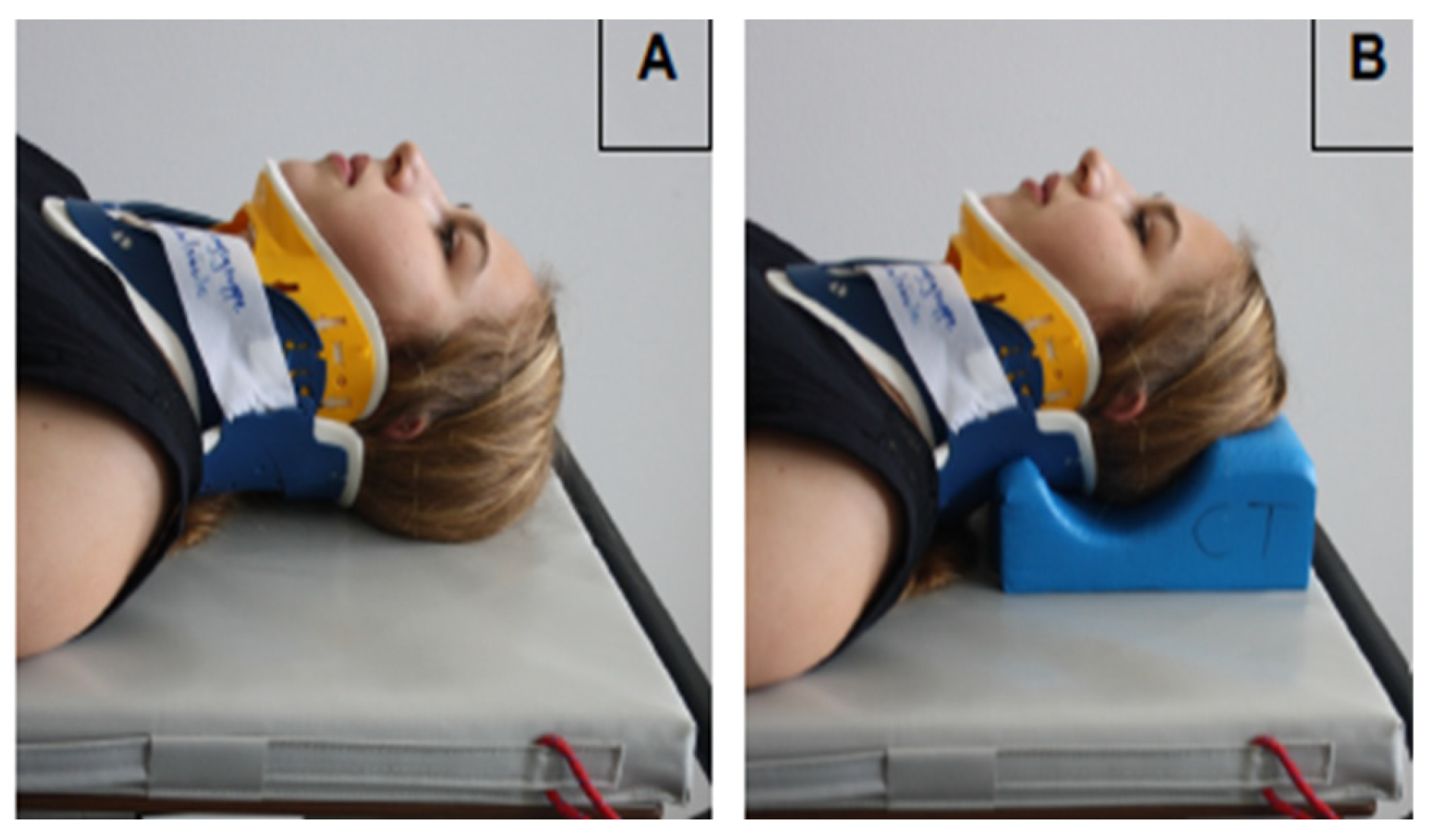

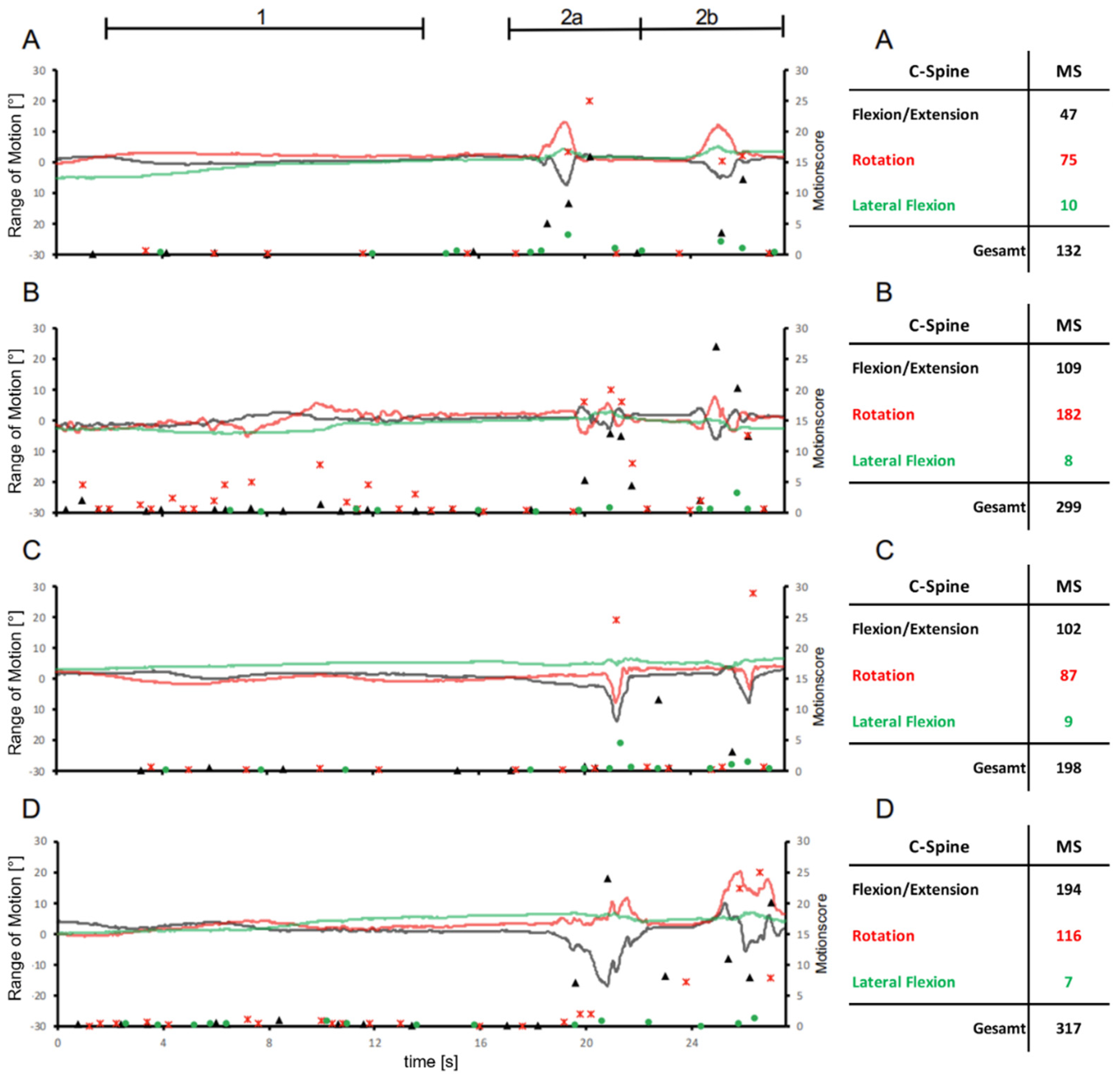

2.3. Ancillary Experiment (Stabilization Pillow)

An additional experiment assessed the effect of a stabilization pillow on the soft positioning mattress. Identical measurement protocols were conducted without and with the pillow (

Figure 3) to determine its influence on axis-specific and total motion scores. Exemplary time series of angular motion and corresponding motion score tables are presented in

Figure 4.

2.4. Outcome Measures and Data Processing

For each axis, motion magnitude was transformed into a motion score; a total motion score was calculated as the sum of the axis-specific scores. The motion score reflects the extent of motion deviation and is discussed in the literature as a surrogate for potential injury risk due to undesired C-spine motion (Nolte et al. 2021).

3. Results

This study examined the use of different immobilization devices for spinal stabilization under clinical conditions and thus represents the first quantitative investigation of motion reduction during in-hospital cervical spine (C-spine) immobilization in which established devices were compared in a controlled setting. The results are based on precise motion measurements using motion tracking and therefore provide a robust basis for assessing the clinical effectiveness of these systems.

Four commonly used immobilization devices were evaluated with regard to their effectiveness in reducing cervical mobility. Analysis of the total motion (sum of angles) across the three axes of movement (flexion/extension, lateral flexion, rotation) revealed significant differences among the tested systems (

Table 1).

The spine board showed the lowest mean total motion score of 122.0 compared with all other devices. Movements were greatest in rotation with a mean motion score of 58.7, followed by flexion/extension (54.1) and lateral flexion (9.1). This suggests that, with respect to C-spine motion, the spine board provides moderate stabilization, with rotation being the least restricted.

With a markedly higher mean total motion score of 238.7, the soft positioning mattress exhibited greater overall motion. Rotation (149.7) and flexion/extension (71.9) were particularly pronounced, whereas lateral flexion was lowest at 17.1. The soft positioning mattress is therefore less effective for C-spine immobilization than the spine board.

The TraumaMattress achieved a mean total motion score of 138.7 and thus ranked between the spine board and the soft positioning mattress. Rotation (68.7) was slightly more pronounced than flexion/extension (61.1), while lateral flexion was lowest at 8.9. Overall, the TraumaMattress stabilizes the C-spine better than the soft positioning mattress but is less effective than the spine board.

With a mean total motion score of 276.3, the vacuum mattress showed the highest motion values of all systems tested. Flexion/extension was most pronounced at 152.0, followed by rotation (110.1) and lateral flexion (14.1). This indicates that the vacuum mattress provides the least effective support for C-spine immobilization. Overall, the results show substantial differences in the immobilizing effect of the devices. Under experimental in-hospital conditions, the vacuum mattress provided the least effective C-spine immobilization, whereas the spine board and the TraumaMattress achieved the lowest total motion scores.

Comparison of C-spine immobilization on the soft positioning mattress shows that the additional stabilization pillow has no significant effect on overall mobility but specifically reduces rotation, while lateral flexion and flexion/extension increase slightly with the pillow.

4. Discussion

The clinical relevance of the measured differences in motion scores between positioning aids warrants careful consideration and should not be underestimated given the vulnerable anatomy of the cervical spine (C-spine). Although no validated threshold exists beyond which C-spine motion is deemed harmful, even small additional movements may pose a relevant risk due to the susceptibility of cervical injuries (Theodore et al. 2013). The cumulative effect of small movements along the entire care pathway can become clinically meaningful. Even minor motions may precipitate neurological deterioration in unstable injuries. Accordingly, the marked reduction in motion observed with the TraumaMattress may contribute to reducing the risk of secondary neurological deterioration.

Beyond measurable motion reduction, subjective parameters, including comfort and perceived safety, are clinically relevant. Studies show that patients on a spine board report back pain and discomfort after as little as 30 minutes (Chan et al. 1994; Hamilton & Pons 1996). These factors matter not only for humane care but also because they influence patient cooperation during diagnostics and transport.

It must also be acknowledged that this study was conducted under experimental conditions with healthy volunteers. Generalizability to real clinical situations—featuring pain, stress, altered muscle tone, and variable cooperation—is therefore limited. Nevertheless, the findings provide a sound basis for reappraising current immobilization practices.

A commonly cited drawback of classic systems such as the spine board is elevated interface pressure, which may lead to pressure injuries with longer dwell times; subjective discomfort is likewise frequently reported. Here, the TraumaMattress may offer an additional advantage due to its softer, more conforming structure. In discussions of patient-centered care, this aspect is particularly relevant.

The present results support the hypothesis that there is considerable variance in clinical application of immobilization tools—both in the choice of device and in handling and duration of immobilization. This is especially problematic because, during the in-hospital phase—through transitions among diagnostics, transport, and operating room preparation—clinically relevant spinal movements can still occur. Our investigation shows that repeated transfers, CT moves, and organizational factors in this phase may raise the risk of secondary neurological injury if adequate immobilization is not ensured. Incorporating a motion-tracking approach provides a novel avenue for quantitatively assessing immobilization effectiveness.

Furthermore, the findings highlight a clinically relevant trade-off among practical handling, imaging compatibility, and patient comfort. This is particularly evident for classic systems such as the spine board, which, despite offering comparatively high stability, can increase pressure-related risk. These considerations underscore the importance of patient-centered solutions such as the TraumaMattress, which—according to internal practical testing—showed high imaging compatibility without causing relevant imaging artifacts..

5. Conclusions

The present results clearly support the superiority of the TraumaMattress over the spine board and the vacuum mattress in terms of motion reduction during in-hospital cervical spine immobilization. Its use may meaningfully contribute to preventing secondary neurological injury while also accommodating patient-centered aspects such as comfort and pressure-injury prophylaxis.

For clinical practice, we recommend critically reassessing existing immobilization protocols and, particularly in trauma rooms, relying on evidence-based tools such as the TraumaMattress. Further studies in clinical settings—ideally including injured patients—are warranted to strengthen external validity.

Our findings underscore the persistent lack of standardized in-hospital immobilization protocols. Application of immobilization tools is often situational and personnel-dependent—an issue that requires urgent correction. A standardized recommendation could be oriented toward a combination of soft, anatomically conforming positioning with robust fixation, as provided by the TraumaMattress. This approach not only yields reliable motion reduction but also meets practical requirements in routine care, including imaging and patient transport.

Future guidelines should incorporate quantitative motion analysis and clinical validation studies. The results of the present work provide a solid foundation for this.

Countries such as Denmark, Norway, and the United Kingdom have already revised their spinal immobilization guidelines. Notably, these emphasize a targeted avoidance of cervical collars in favor of patient-centered positioning and manual stabilization (Maschmann et al., 2019; SEC Ambulance Service, 2020). These developments illustrate a paradigm shift toward more flexible and individually tailored care strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., M.K. and P.R.; methodology, A.G., E.O.; formal analysis, E.O. and M.K.; investigation, A.G., M.K., M.J.; data curation, A.G., E.O., M.K., P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., E.O., M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.J., P.A.G., P.R.; visualization, E.O., M.K.; supervision, A.G., P.A.G., P.R.; project administration, A.G., M.K., P.A.G., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by BG Klinik Ludwigshafen.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benger, J.; Blackham, J. (2009). Why do we put cervical collars on conscious trauma patients? Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 17(1), 44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernik, M. N.; Seidel, H. H.; Blalock, R. E.; Burgess, A. R.; Horodyski, M.; Rechtine, G. R.; Prasarn, M. L. (2016). Comparison of tissue-interface pressure in healthy subjects lying on two trauma splinting devices: The vacuum mattress splint and long spine board. Injury 47(8), 1801–1805. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.; Goldberg, R.; Tascone, A.; Harmon, S.; Chan, L. (1994). The effect of spinal immobilization on healthy volunteers. Annals of emergency medicine 23(1), 48–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie (DGU). (2023). S3-Leitlinie Polytrauma/Schwerverletzten-Behandlung (AWMF-Registernummer 187-023, Version 4.0). Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/187-023l_S3_Polytrauma-Schwerverletzten-Behandlung_2023-06.pdfThieme+8.

- Wnent, J. (2023). Wann macht eine Immobilisation der Wirbelsäule Sinn? retten! 12(05), 350. [CrossRef]

- Gather, A.; Spancken, E.; Münzberg, M.; Grützner, P. A.; Kreinest, M. (2020). Spinal Immobilization in the Trauma Room - a Survey-Based Analysis at German Level I Trauma Centers. Die Immobilisation der Wirbelsäule im Schockraum – eine umfragebasierte Analyse in den deutschen überregionalen Traumazentren. Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und Unfallchirurgie 158(6), 597–603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutcher, C. M.; Lochhead, V. (2005). Reduction in mouth opening with semi-rigid cervical collars. British journal of anaesthesia 95(3), 344–348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, R. S.; Pons, P. T. (1996). The efficacy and comfort of full-body vacuum splints for cervical-spine immobilization. The Journal of emergency medicine 14(5), 553–559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauswald, M., Ong, G., Tandberg, D., & Omar, Z. (1998). Out-of-hospital spinal immobilization: its effect on neurologic injury. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 5(3), 214–219. [CrossRef]

- Haut, E. R.; Kalish, B. T.; Efron, D. T.; Haider, A. H.; Stevens, K. A.; Kieninger, A. N.; Cornwell, E. E., 3rd; Chang, D. C. (2010). Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: more harm than good? The Journal of trauma 68(1), 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Hood, N.; Considine, J. (2015). Spinal immobilisaton in pre-hospital and emergency care: A systematic review of the literature. Australasian emergency nursing journal: AENJ 18(3), 118–137. [CrossRef]

- Häske, D.; Dorau, W.; Eppler, F.; Heinemann, N.; Metzger, F.; Schempf, B. (2024). Prevalence of prehospital pain and pain assessment difference between patients and paramedics: a prospective cross-sectional observational study. Scientific reports 14(1), 5613. [CrossRef]

- Kornhall, D. K.; Jørgensen, J. J.; Brommeland, T.; Hyldmo, P. K.; Asbjørnsen, H.; Dolven, T.; Hansen, T.; Jeppesen, E. (2017). The Norwegian guidelines for the prehospital management of adult trauma patients with potential spinal injury. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine 25(1), 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luscombe, M. D.; Williams, J. L. (2003). Comparison of a long spinal board and vacuum mattress for spinal immobilisation. Emergency medicine journal: EMJ 20(5), 476–478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschmann, C.; Jeppesen, E.; Rubin, M. A.; Barfod, C. (2019). New clinical guidelines on the spinal stabilisation of adult trauma patients - consensus and evidence based. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine 27(1), 77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, J. M.; Sharwood, L. N.; Cameron, P.; Middleton, P. M.; Harrison, J. E.; Brown, D.; McClure, R.; Smith, K.; Muecke, S.; Healy, S. (2014). Right care, right time, right place: improving outcomes for people with spinal cord injury through early access to intervention and improved access to specialised care: study protocol. BMC health services research 14, 600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, P. C.; Uzun, D. D.; Häske, D.; Weerts, J.; Münzberg, M.; Rittmann, A.; Grützner, P. A.; Kreinest, M. (2021). Analysis of cervical spine immobilization during patient transport in emergency medical services. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 47(3), 719–726. [CrossRef]

- Noonan, V. K.; Fingas, M.; Farry, A.; Baxter, D.; Singh, A.; Fehlings, M. G.; Dvorak, M. F. (2012). Incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: A national perspective. Neuroepidemiology 38(4), 219–226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasarn, M. L.; Hyldmo, P. K.; Zdziarski, L. A.; Loewy, E.; Dubose, D.; Horodyski, M.; Rechtine, G. R. (2017). Comparison of the Vacuum Mattress versus the Spine Board Alone for Immobilization of the Cervical Spine Injured Patient: A Biomechanical Cadaveric Study. Spine 42(24), E1398–E1402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodore, N.; Hadley, M. N.; Aarabi, B.; Dhall, S. S.; Gelb, D. E.; Hurlbert, R. J.; Rozzelle, C. J.; Ryken, T. C.; Walters, B. C. (2013). Prehospital cervical spinal immobilization after trauma. Neurosurgery 72 Suppl 2, 22–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018, 115, 697–704. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).