Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Cohort

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

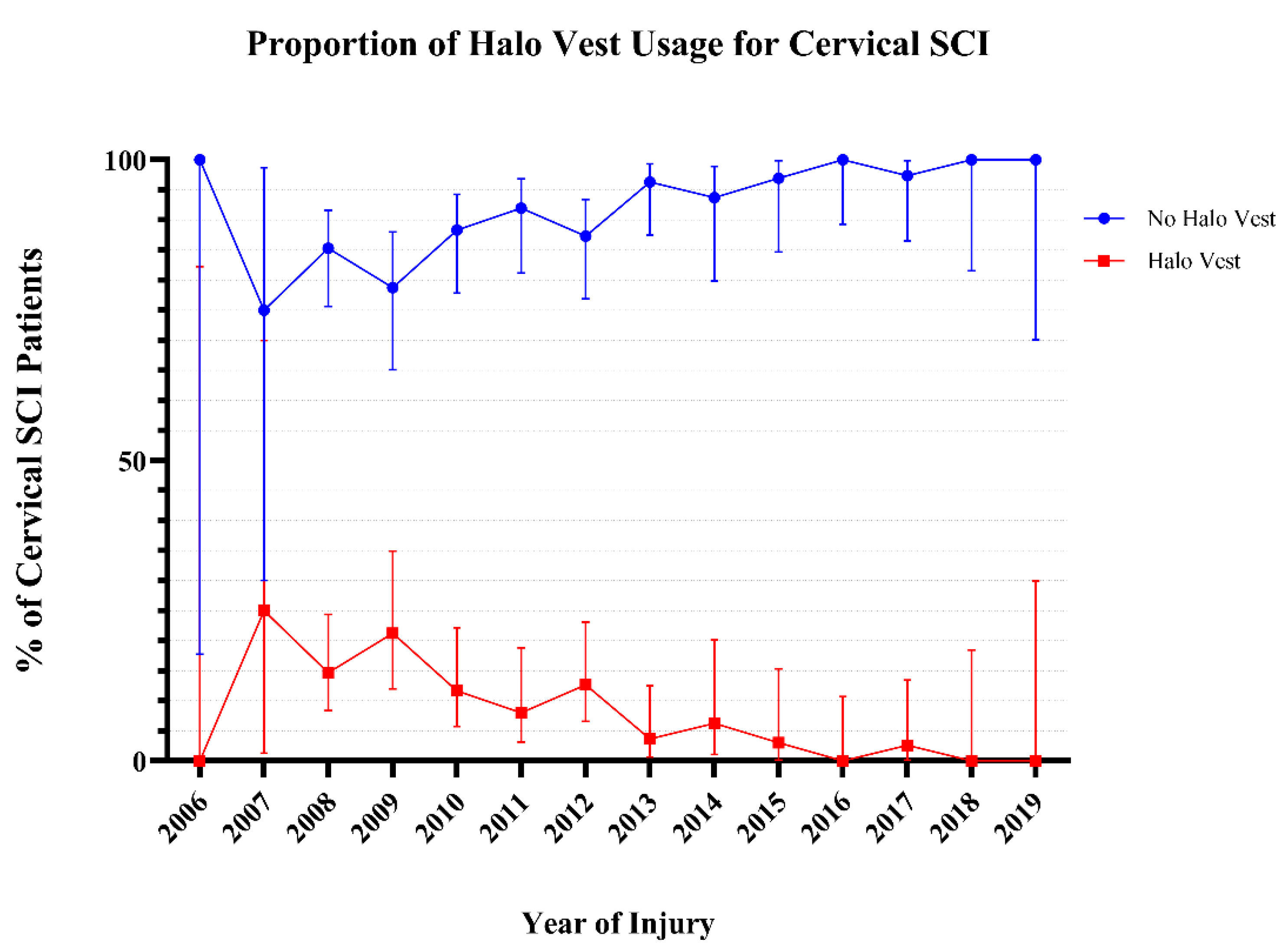

3.2.1. Comparison of Patients Treated with Halo Vest to No Halo Vest

4. Discussion

5. Conclusionห

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | ASIA Impairment Scale |

| ASIA | American Spinal Injury Association |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| GI/GU | Gastrointestinal / Genito Urinary |

| HV | Halo Vest |

| MOI | Mechanism of Injury |

| MVA | Motor Vehicle Accident |

| NACTN | North American Clinical Trials Network |

| OF | Odontoid Fracture |

| SCI | Spinal Cord injury |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Perry, J.; Nickel, V.L. Total Cervical-Spine Fusion for Neck Paralysis. JBJS 1959, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsogiannis, P.; Weisbrod, L.J.; Dowling, T.J. Halo brace. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: 2024.

- Parry, H.; Delargy, M.; Burt, A. Early mobilisation of patients with cervical cord injury using the halo brace device. Spinal Cord 1988, 26, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, R.; Iacopino, G.; Giorgiutti, F.; Veltri, C.; Copetti, E.; Imbrucè, P.; Cappelletto, B. Halo Vest Immobilization: Is It Still a Valid Treatment for Atlantoaxial Fractures? World Neurosurgery 2025, 193, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.G.; Ko, J.H.; Park, J.B.; Ju, G.I. Anterior Dens Screw Fixation for Traumatic C1-2 Lateral Subluxation With 3-Part Fractures of the C2 Axis (Dens, Lateral Mass, and Hangman Fractures): A Case Report. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Okawa, A.; Misawa, S.; Sakuma, T.; Takahashi, H.; Kato, K.; Kuwabara, S.; Takahashi, K. Cervical myelopathy in patients with athetoid cerebral palsy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38, E151–E157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati, A.; Oni, P. Three-point atlantoaxial fixation with C1-C2 transarticular screws and C1 lateral mass screws. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019, 27, 2309499019854201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, M.R.; Gstrein, A.; Müller, E.J. Treatment of Dens Fractures with Anterior Screw Fixation. JBJS Essent Surg Tech 2014, 4, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D.; Goncalves, S.; Kerezoudis, P.; Alvi, M.A.; Freedman, B.A.; Nassr, A.; Bydon, M. Comparison of Outcomes for Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion With and Without Anterior Plate Fixation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018, 43, E413–e422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, B.; Ollier, E.; Pelletier, J.-B.; Castel, X.; Vassal, F.; Tetard, M.-C. Conservative versus Surgical Treatment for Odontoid Fracture: Is the Surgical Treatment Harmful? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurgery 2020, 141, 490–499.e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Matur, A.V.; Street, S.; Shukla, G.; Garcia-Vargas, J.; Mehta, J.; Childress, K.; Duah, H.O.; Gibson, J.; Cass, D.; et al. No Difference in Surgical Outcomes Between Stand-Alone Devices and Anterior Plating for 1-2 Level Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion: A 1:1 Exact Matched Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2024, 49, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Kurimoto, M.; Hayashi, N.; Ohmori, T.; Hirashima, Y.; Endo, S. [Atlas burst fracture (Jefferson fracture) requiring surgical treatment after conservative treatment--report of two cases]. No Shinkei Geka 2002, 30, 987–991. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancic, P.C.; Beauchman, N.N.; Mo, F.; Lawrence, B.D. Biomechanics of halo-vest and dens screw fixation for type II odontoid fracture. Spine 2009, 34, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.A.; Nickel, V.L. The halo vest: an evaluation of motion and forces across the neck. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1978, 3, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, B.; Sihlbom, H.; Nordwall, A. Forces and motions across the neck in patients treated with halo-vest. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988, 13, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvis, T.A.; Carlin, B.; Driscoll, P. The definite risks and questionable benefits of liberal pre-hospital spinal immobilisation. Am J Emerg Med 2017, 35, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, M.; Arrigo, R.T.; Kalanithi, P.S.; Chen, Y.R. Impact of age, injury severity score, and medical comorbidities on early complications after fusion and halo-vest immobilization for C2 fractures in older adults: a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012, 37, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bransford, R.J.; Stevens, D.W.; Uyeji, S.; Bellabarba, C.; Chapman, J.R. Halo vest treatment of cervical spine injuries: a success and survivorship analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009, 34, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnik, S.L.; Scott, K.W.; Kuhn, M.Z.; Alcindor, D.; Tavanaiepour, K.; Tavanaiepour, D.; Crandall, M.; Rahmathulla, G. Halo vest immobilization—an institutional review of safety in acute cervical spine injury from 2013 to 2017. Br J Neurosurg 2021, 35, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Middendorp, J.J.; Slooff, W.-B.M.; Nellestein, W.R.; Öner, F.C. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Complications Associated with Halo-Vest Immobilization: A Prospective, Descriptive Cohort Study of 239 Patients. JBJS 2009, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toups, E.G.; Ugiliweneza, B.; Howley, S.P.; Neal, C.J.; Harrop, J.S.; Guest, J.D.; Grossman, R.G.; Fehlings, M.G. North American Clinical Trials Network for Spinal Cord Injury Registry: Methodology and Analysis. J Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, B.; Ren, J. A cross-sectional study on interference control: age affects reactive control but not proactive control. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, M.T.; Harrop, J.S.; Houten, J.K. Traumatic Central Cord Syndrome. Clin Spine Surg 2024, 37, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebeyehu, T.F.; Mong, E.R.; Thalheimer, S.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Harrop, J. Epidemiology of Spinal Cord Injury and Associated Mortality, Past and Present. Is There a Difference? World Neurosurg 2024, 192, e494–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, S.R.; Botte, M.J.; Waters, R.L.; Nickel, V.L. Complications in the use of the halo fixation device. JBJS 1986, 68, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, J.A.; Whitehill, R.; Stamp, W.G.; Jane, J.A. Complications associated with the halo-vest: A review of 245 cases. Journal of Neurosurgery 1986, 65, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurucan, E.; Sulovari, A.; Thirukumaran, C.; Greenstein, A.; Molinari, R.; Mesfin, A. Volume-outcome relationship in halo vest utilization for C2 fractures. Spine J 2020, 20, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcourt, T.; Bégué, T.; Saintyves, G.; Mebtouche, N.; Cottin, P. Management of upper cervical spine fractures in elderly patients: current trends and outcomes. Injury 2015, 46 (Suppl 1), S24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.B.; Reichmann, W.M.; Bono, C.M.; Bouchard, K.; Corbett, K.L.; Warholic, N.; Simon, J.B.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; Maciolek, L.; Corsello, P.; et al. Mortality in Elderly Patients After Cervical Spine Fractures. JBJS 2010, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, J.S.; Hart, R.; Anderson, P.A. Optimal Treatment for Odontoid Fractures in the Elderly. Spine 2010, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, E.M.; Theodore, N.; Feiz-Erfan, I.; Lekovic, G.P.; Dickman, C.A.; Sonntag, V.K.H. Complications of halo fixation in the elderly. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine SPI 2006, 5, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koech, F.; Ackland, H.M.; Varma, D.K.; Williamson, O.D.; Malham, G.M. Nonoperative Management of Type II Odontoid Fractures in the Elderly. Spine 2008, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majercik, S.; Tashjian, R.Z.; Biffl, W.L.; Harrington, D.T.; Cioffi, W.G. Halo Vest Immobilization in the Elderly: A Death Sentence? Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2005, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelalis, I.D.; Christoforou, G.; Motsis, E.; Arnaoutoglou, C.; Xenakis, T. Brain abscess and generalized seizure caused by halo pin intracranial penetration: case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J 2009, 18 (Suppl 2), 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, A.W.; Zakaria, R.; May, P.; Barrett, C. Overtightening of halo pins resulting in intracranial penetration, pneumocephalus, and epileptic seizure. Int J Spine Surg 2013, 7, e42–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, R.; Peters, J.M.; Coene, L.N. Intracranial penetration of a halo pin causing an epileptic seizure. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006, 88, 1654–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Adeoye, A.L.; Dahdaleh, N.S. Indications and complications of crown halo vest placement: A review. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2017, 40, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashjian, R.Z.; Majercik, S.; Biffl, W.L.; Palumbo, M.A.; Cioffi, W.G. Halo-Vest Immobilization Increases Early Morbidity and Mortality in Elderly Odontoid Fractures. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2006, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taitsman, L.A.; Altman, D.T.; Hecht, A.C.; Pedlow, F.X. Complications of cervical halo-vest orthoses in elderly patients. Orthopedics 2008, 31, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Kepler, C.K.; Kopjar, B.; Chapman, J.; Shaffrey, C.; Arnold, P.; Gokaslan, Z.; Brodke, D.; France, J.; Dekutoski, M.; et al. Functional and quality-of-life outcomes in geriatric patients with type-II dens fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013, 95, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, A.; Piccirilli, M.; Pescatori, L.; Santoro, A.; D’Elia, A. Single institute experience on 108 consecutive cases of type II odontoid fractures: surgery versus conservative treatment. Turk Neurosurg 2014, 24, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean Age (SD, range) | 48.9 (17.8, 14.7–88.4) years | ||

| Count | % | 95% CI | |

| Halo Vest Use (n = 516) | |||

| Yes | 47 | 9.1 | 6.9–11.9 |

| No | 469 | 90.9 | 88.1–93.1 |

| Age Category (n = 516) | |||

| Pediatric (0–18) | 1 | 0.2 | 0–1.1 |

| Young Adult (19–25) | 64 | 12.4 | 9.8–15.5 |

| Adult (26–44) | 119 | 23.1 | 19.6–26.9 |

| Middle Age (45–59) | 147 | 28.5 | 24.8–32.5 |

| Above 60 | 142 | 27.5 | 23.8–31.5 |

| Unknown | 43 | 8.3 | 6.2–11.0 |

| Sex (n = 483) | |||

| Male | 381 | 78.9 | 75–82.3 |

| Female | 102 | 21.1 | 17.7–25 |

| Race (n = 472) | |||

| Caucasian | 332 | 70.3 | 66.1–74.3 |

| Black | 94 | 19.9 | 16.6–23.8 |

| Other | 46 | 9.7 | 7.4–12.8 |

| Type of Injury (n = 516) | |||

| Blunt | 460 | 89.1 | 86.2–91.5 |

| Crush | 32 | 6.2 | 4.4–8.6 |

| Penetrating | 10 | 1.9 | 1.1–3.5 |

| Other | 14 | 2.7 | 1.6–4.5 |

| Mechanism of Injury (n = 503) | |||

| MVA | 184 | 36.6 | 32.5–40.9 |

| Fall | 214 | 42.5 | 38.3–46.9 |

| Sport/Recreation | 69 | 13.7 | 11.0–17.0 |

| Assault | 18 | 3.6 | 2.3–5.6 |

| Other | 18 | 3.6 | 2.3–5.6 |

| Neurologic Level of Injury (n = 516) | |||

| C1 | 17 | 3.3 | 2.1–5.2 |

| C2 | 35 | 6.8 | 4.9–9.3 |

| C3 | 122 | 23.6 | 20.2–27.5 |

| C4 | 96 | 18.6 | 15.5–22.2 |

| C5 | 133 | 25.8 | 22.2–29.7 |

| C6 | 94 | 18.2 | 15.1–21.8 |

| C7 | 19 | 3.7 | 2.4–5.7 |

| ASIA Impairment Scale (n = 390) | |||

| A | 142 | 36.4 | 31.8–41.3 |

| B | 48 | 12.3 | 9.4–15.9 |

| C | 59 | 15.1 | 11.9–19.0 |

| D | 141 | 36.2 | 31.5–41 |

| Central Cord Syndrome (n = 388) | 174 | 44.8 | 40.0–49.8 |

| Comorbidities (n = 497) | |||

| Hypertension | 166 | 33.3 | 29.3–37.5 |

| Diabetes | 133 | 26.8 | 23.1–30.9 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 19 | 3.8 | 2.5–5.9 |

| Pulmonary co-morbidities | 114 | 23 | 19.5–26.9 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 0 | 0 | |

| Malignancy | 8 | 1.6 | 0.8–3.2 |

| Tobacco | 10 | 2 | 1.1–3.7 |

| Drug Abuse | 47 | 9.5 | 7.2–12.4 |

| Complications (n = 516) | |||

| Cardiac | 173 | 33.5 | 29.6–37.7 |

| GI/GU | 210 | 40.7 | 36.5–45.0 |

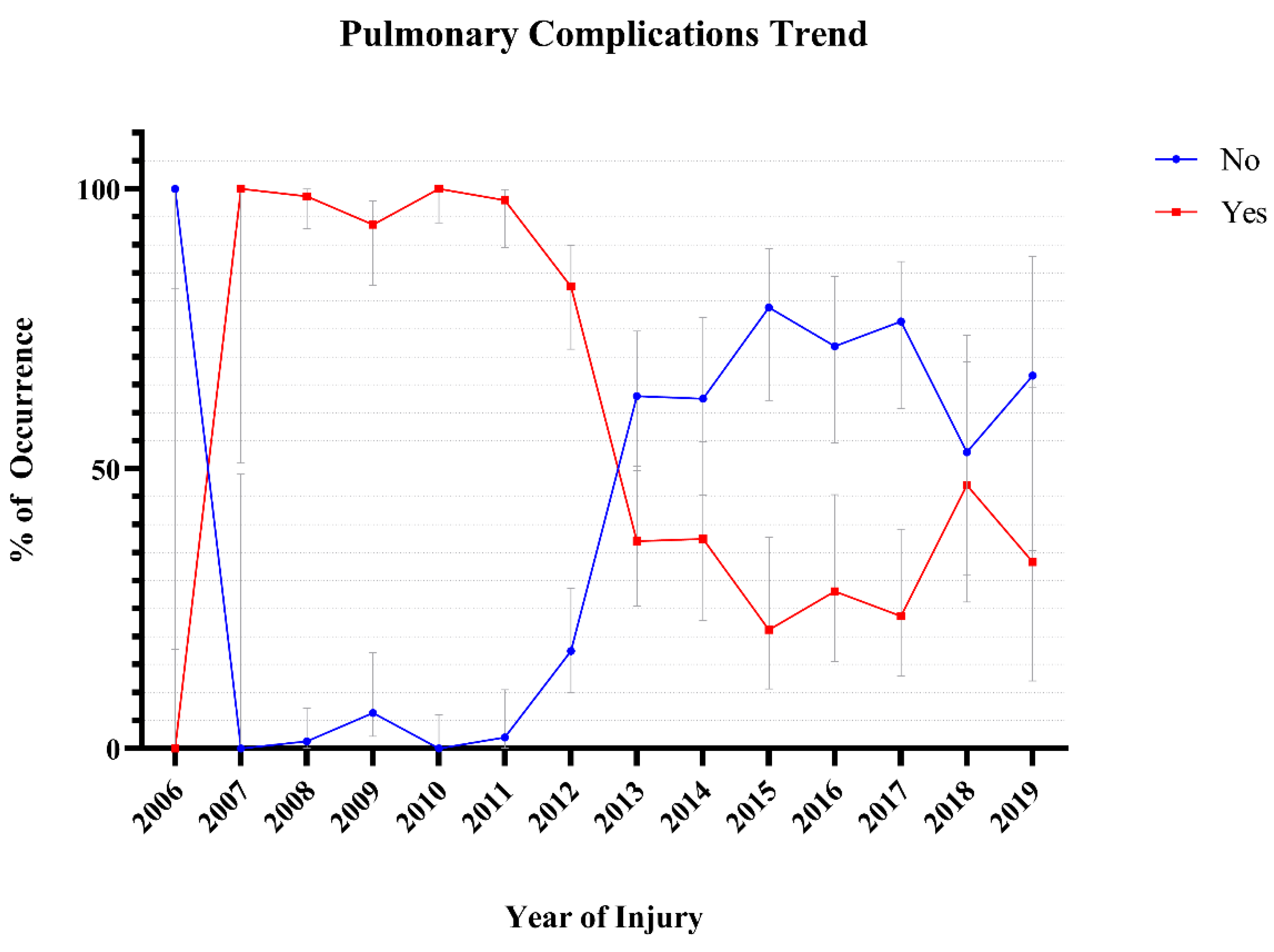

| Pulmonary | 351 | 68 | 63.9–71.9 |

| Skin | 71 | 16.2 | 11.1–17.0 |

| Halo Vest | No-Halo Vest | P-Value | |||||

| Mean Age (SD, range) | 37.4 (17.4, 19.9–83.5) | 50.0 (17.5, 14.7–88.4) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Count | % | 95% CI | Count | % | 95% CI | ||

| Age Category (n = 516) | |||||||

| Pediatric (0–18) | 0 | 0 | 0.0–94.9 | 1 | 100 | 5.1–100 | <0.0001 |

| Young Adult (19–25) | 13 | 20.3 | 12.3–31.7 | 51 | 79 | 68.3–87.7 | |

| Adult (26–44) | 19 | 16 | 10.5–23.6 | 100 | 84 | 76.4–89.5 | |

| Middle Age (45–59) | 5 | 3.4 | 1.5–7.7 | 142 | 96.6 | 92.3–98.5 | |

| Above 60 | 4 | 2.8 | 1.1–7.0 | 138 | 97.2 | 93.0–98.9 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 14 | 6.6–27.3 | 37 | 86 | 72.7–93.4 | |

| Sex (n = 483) | |||||||

| Male | 33 | 8.7 | 6.2–11.9 | 348 | 91.3 | 6.9–19.4 | 0.3402 |

| Female | 12 | 11.8 | 6.9–19.4 | 90 | 88.2 | 80.6–88.2 | |

| Race (n = 472) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 302 | 9.0 | 6.4–12.6 | 30 | 91.0 | 87.4–93.6 | 0.4236 |

| Black | 82 | 12.8 | 7.5–21 | 12 | 87.2 | 79.0–92.5 | |

| Other | 43 | 6.5 | 2.2–17.5 | 3 | 93.5 | 82.5–97.8 | |

| Type of Injury (n = 516) | |||||||

| Blunt | 44 | 9.6 | 7.2–12.6 | 416 | 90.4 | 87.4–92.8 | 0.6286 |

| Crush | 1 | 3.1 | 0.2–15.7 | 31 | 96.9 | 84.3–99.8 | |

| Penetrating | 1 | 10.0 | 0.5–40.4 | 9 | 90.0 | 59.6–99.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 7.1 | 0.4–31.5 | 13 | 92.9 | 68.5–99.6 | |

| Mechanism of Injury (n = 503) | |||||||

| MVA | 24 | 13.0 | 8.9–18.7 | 160 | 87.0 | 81.3–91.1 | 0.0295 |

| Fall | 10 | 4.7 | 2.6–8.4 | 204 | 95.3 | 91.6–97.4 | |

| Sport/Recreation | 8 | 11.6 | 6.0–21.2 | 61 | 88.4 | 78.8–94.0 | |

| Assault | 2 | 11.1 | 2.0–32.8 | 16 | 88.9 | 67.2–98.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 5.6 | 0.3–25.8 | 17 | 94.4 | 74.2–99.7 | |

| Neurologic Level of Injury (n = 516) | |||||||

| C1 | 1 | 5.9 | 0.3–27.0 | 16 | 94.1 | 73.0–99.7 | 0.078 |

| C2 | 6 | 17.1 | 8.1–32.7 | 29 | 82.9 | 67.3–91.9 | |

| C3 | 5 | 4.1 | 1.8–9.2 | 117 | 95.9 | 90.8–98.2 | |

| C4 | 6 | 6.3 | 2.9–13.0 | 90 | 93.8 | 87.0–97.1 | |

| C5 | 16 | 12.0 | 7.5–18.6 | 117 | 88.0 | 81.4–92.5 | |

| C6 | 12 | 12.8 | 7.5–21.0 | 82 | 87.2 | 79.0–92.5 | |

| C7 | 1 | 5.3 | 0.3–24.6 | 18 | 94.7 | 75.4–99.7 | |

| ASIA Impairment Scale (n = 390) | |||||||

| A | 16 | 11.3 | 7.1–17.5 | 126 | 88.7 | 82.5–92.9 | 0.2714 |

| B | 4 | 8.3 | 3.3–19.6 | 44 | 91.7 | 80.4–96.7 | |

| C | 5 | 8.5 | 3.7–18.4 | 54 | 91.5 | 81.6–96.3 | |

| D | 7 | 5.0 | 2.4–9.9 | 134 | 95.0 | 90.1–97.6 | |

| Central Cord Syndrome (n = 388) | 8 | 4.6 | 2.3–8.8 | 166 | 95.4 | 91.2–97.7 | 0.0004 |

| Comorbidities (n = 497) | |||||||

| Hypertension | 19 | 11.4 | 7.5–17.2 | 147 | 88.6 | 82.8–92.5 | 0.1878 |

| Diabetes | 6 | 4.5 | 2.1–9.5 | 127 | 95.5 | 90.5–97.9 | 0.0339 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 2 | 10.5 | 1.9–31.4 | 17 | 89.5 | 68.6–98.1 | 0.6871 |

| Pulmonary Co-morbidities | 13 | 88.6 | 81.5–93.2 | 101 | 11.4 | 6.8–18.5 | 0.3535 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0–32.4 | 8 | 100.0 | 67.6–100 | > 0.9999 |

| Tobacco | 1 | 10.0 | 0.5–40.4 | 9 | 90.0 | 59.6–99.5 | > 0.9999 |

| Drug Abuse | 3 | 6.4 | 2.2–17.2 | 44 | 93.6 | 82.8–97.8 | 0.6043 |

| Complications (n = 516) | |||||||

| Cardiac | 18 | 38.3 | 25.8–52.6 | 155 | 33.0 | 28.9–37.4 | 0.5174 |

| GI/GU | 25 | 53.2 | 39.2–66.7 | 185 | 39.4 | 33.3–60.8 | 0.086 |

| Pulmonary | 42 | 89.4 | 77.4–95.4 | 309 | 65.9 | 61.5–70.0 | 0.0008 |

| Skin | 9 | 19.1 | 10.4–32.5 | 62 | 13.2 | 10.5–16.6 | 0.2671 |

| Age Group | No | % | 95% CI | Yes | % | 95% CI |

| Pediatric (0–18) | 1 | 100.0 | 5.1–100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0–94.9 |

| Young Adult (19–25) | 46 | 75.4 | 63.3–84.5 | 15 | 24.6 | 15.5–36.7 |

| Adult (26–44) | 81 | 69.8 | 60.9–77.4 | 35 | 30.2 | 22.6–39.1 |

| Middle Age (45–59) | 103 | 74.1 | 66.2–80.7 | 36 | 25.9 | 19.3–33.8 |

| Above 60 | 114 | 83.8 | 76.7–89.1 | 22 | 16.2 | 10.9–23.3 |

| Unknown | 36 | 85.7 | 72.2–93.3 | 6 | 14.3 | 6.7–27.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).