Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

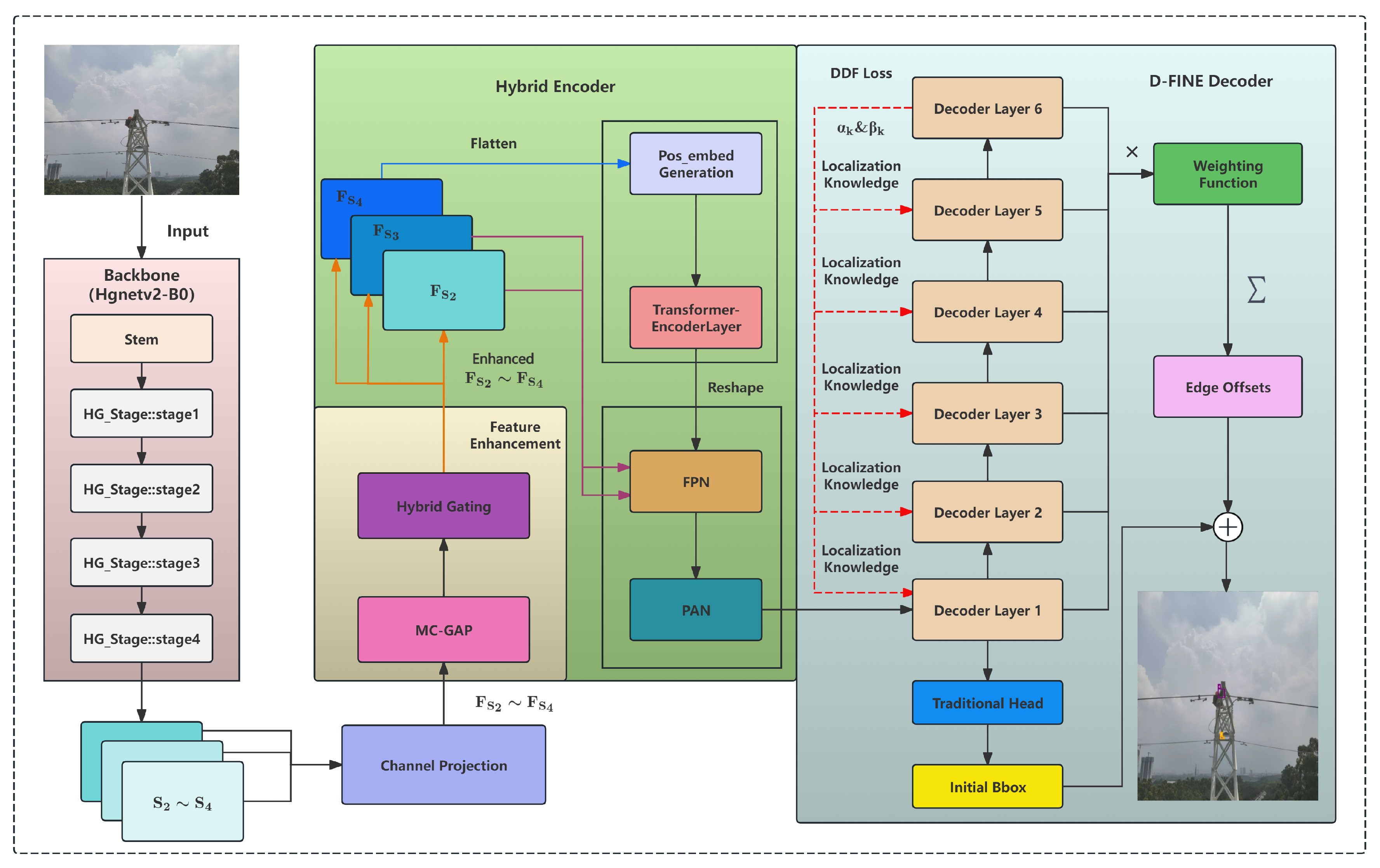

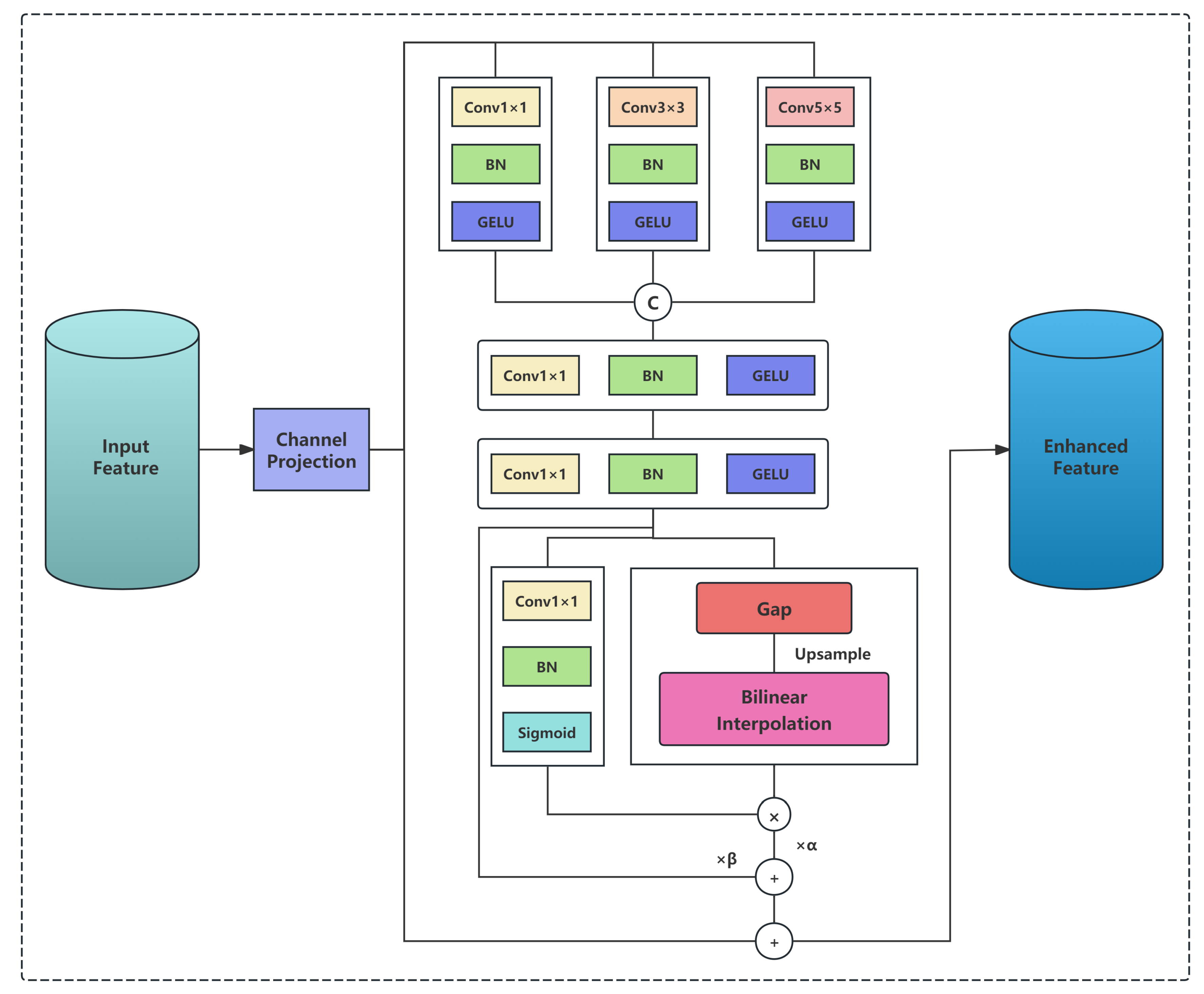

- MC-GAP for Small-Target Enhancement: We develop an MC-GAP module that aggregates features from different receptive fields via multi-scale convolutions, followed by concatenation, fusion, and global average pooling augmented with frequency-domain information. By jointly exploiting spatial and frequency cues in a multi-scale manner, MC-GAP strengthens the representation of fine textures and global context for small OPGW targets, leading to notably improved detection accuracy under complex backgrounds.

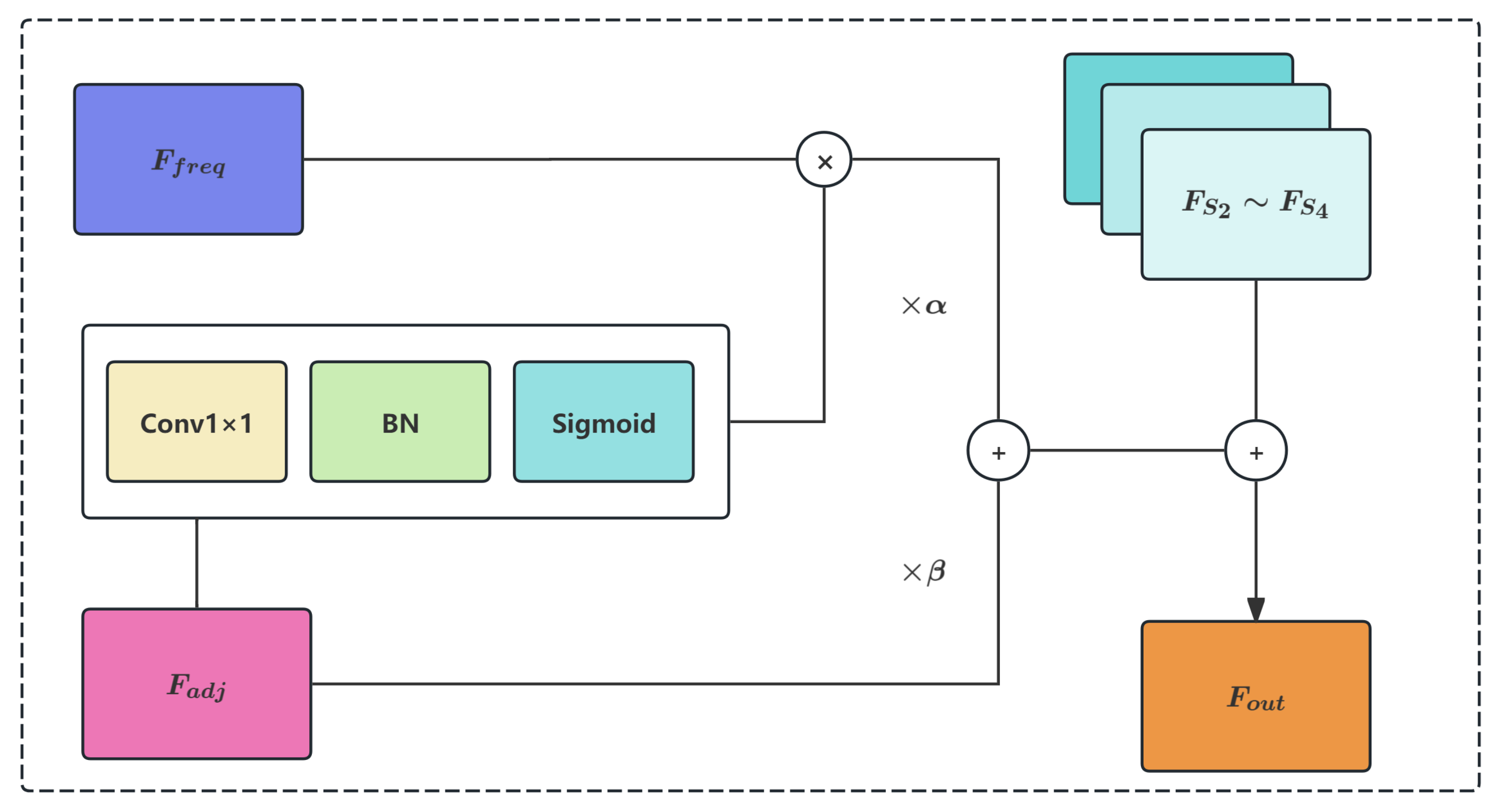

- Hybrid Gating for Frequency-Spatial Feature Balancing: We design a hybrid gating mechanism that combines global learnable scalars (, ) with spatial-adaptive gate maps to dynamically weight frequency-enhanced and spatial-enhanced features. The global scalars provide coarse-grained balance control, while the gate maps enable pixel-wise adaptivity. Together with residual connections that preserve the original feature information, this scheme enriches feature diversity and robustness, and alleviates the limitations of conventional convolutional layers constrained by single receptive fields and limited feature expressiveness.

2. Related Work

2.1. Transmission Line Inspection Technologies

2.2. Learning-based Object Detection

3. OPGW-DETR with Frequency-Spatial Feature Fusion for UAV Inspection Images

3.1. Multi-scale Convolution-based Global Average Pooling (MC-GAP)

3.1.1. Multi-scale Parallel Convolution Processing

-

Step 1 - Parallel Multi-scale Convolution: Three convolutional layers with kernel sizes , , and are applied in parallel to extract multi-scale spatial features. All convolutions include Batch Normalization and GELU activation:The convolution captures point-wise information, the convolution aggregates local fine textures enhancing the cable’s fibrous details, and the convolution integrates semantic and textural continuity over a larger spatial range.

- Step 2 - Channel Concatenation: The three branches are concatenated along the channel dimension:

- Step 3 - Feature Fusion: A convolution is used to fuse and reduce the dimensionality back to D channels:

3.1.2. Approximate Extraction of Low-Frequency Information

3.2. Hybrid Gating Mechanism and Residual Connection

- Spatial Adaptivity: The map varies across spatial locations, enabling the model to emphasize frequency features in regions where global structural information is crucial while preserving spatial details where fine textures dominate;

- Global Balance: The scalar parameters and provide coarse-grained control over the relative importance of frequency versus spatial pathways across the entire feature map, allowing the model to learn task-specific optimal weighting strategies.

4. Numerical Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Detection Performance and Efficiency Comparison

4.3. Performance Gains from MC-GAP and Hybrid Gating

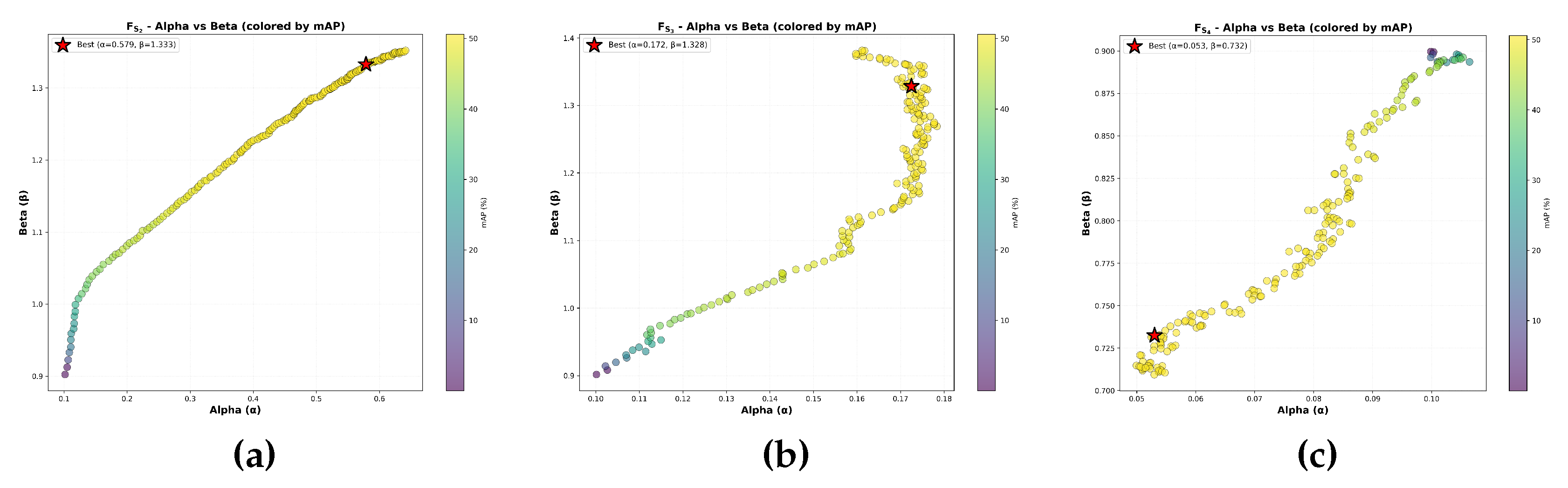

- Low-level features () require substantial frequency-domain enhancement () to amplify fine-grained textures and edge information. The relatively balanced ratio indicates that low-level representations benefit nearly equally from both domains. The high absolute values () suggest that both frequency and spatial enhancements are necessary to compensate for the inherently limited semantic discriminability of low-level features.

- Mid-level features () exhibit a pronounced shift toward spatial-domain dominance. While maintaining a high , the substantial reduction in indicates that mid-level semantic abstractions are susceptible to frequency-domain perturbations. At this level, features encode partially hierarchical patterns and compositional structures, relying on spatial coherence rather than high-frequency details. Excessive frequency enhancement () may introduce artifacts that compromise semantic information acquisition.

- High-level features () demonstrate an extreme spatial bias, with frequency enhancement nearly eliminated. The minimal value reflects that high-level semantic representations exhibit minimal dependence on frequency-domain information while being particularly sensitive to high-frequency noise therein. Notably, also falls below 1.0, indicating that high-level features obtained from the pretrained backbone already possess sufficient representational capacity, requiring only conservative spatial refinement.

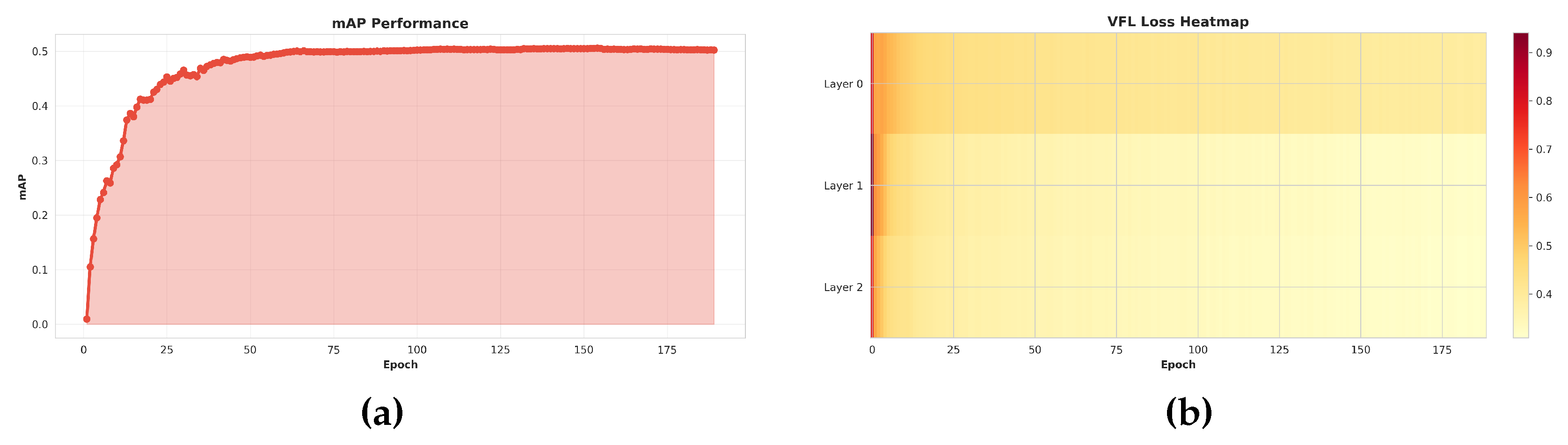

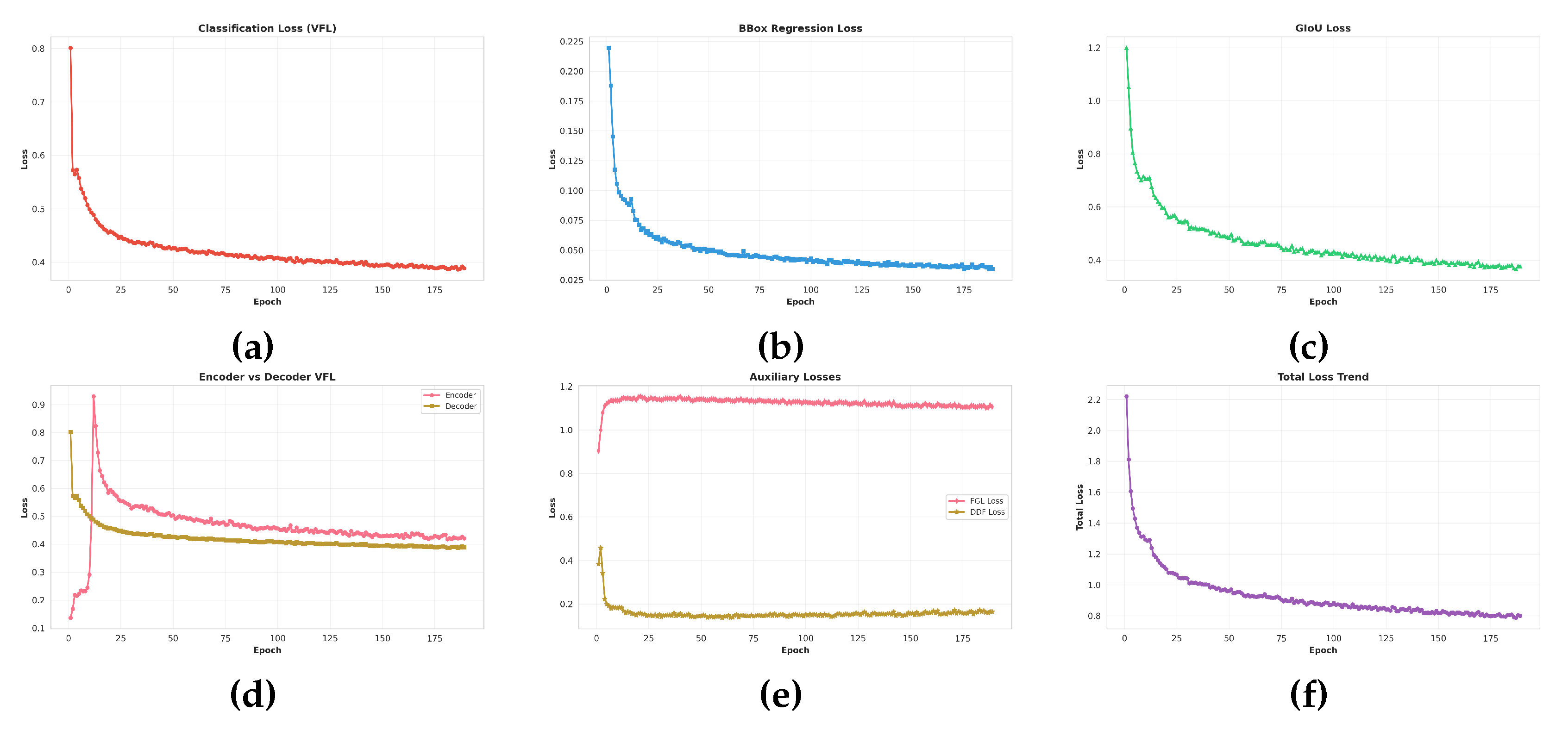

4.4. Analysis of Accuracy Improvement and Loss Stabilization in OPGW-DETR

5. Discussion on UAV Images Detection with OPGW-DETR

6. Conclusions

References

- Song, J.; Sun, K.; Wu, D.; Cheng, F.; Xu, Z. Fault Analysis and Diagnosis Method for Intelligent Maintenance of OPGW Optical Cable in Power Systems. Proc. Int. Conf. Appl. Tech. Cyber Intell. (ATCI) 2021, pp. 186–191.

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV) 2020, pp. 213–229.

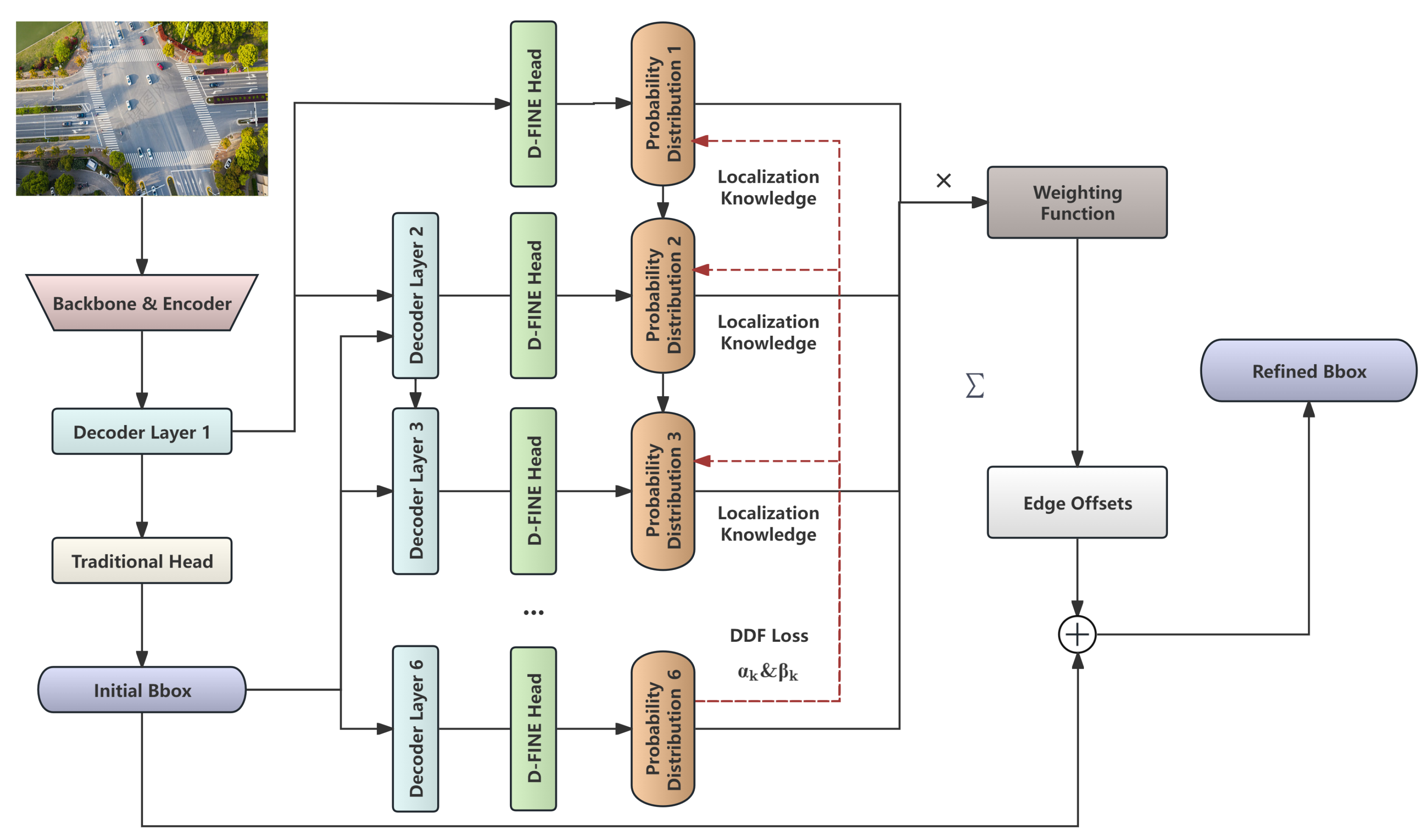

- Peng, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wu, F. D-FINE: Redefine Regression Task in DETRs as Fine-grained Distribution Refinement. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.13842. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Xu, H. Power transmission line inspection robots: A review, trends and challenges for future research. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Mohanta, J.C.; Keshari, A. Power Transmission Line Inspections: Methods, Challenges, Current Status and Usage of Unmanned Aerial Systems. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferbin, F.J.; Meganathan, L.; Esha, M.; Thao, N.G.M.; Doss, A.S.A. Power Transmission Line Inspection Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle – A Review. Proc. Innov. Power Adv. Comput. Technol. (i-PACT) 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. UAV-DETR: An Enhanced RT-DETR Architecture for Efficient Small Object Detection in UAV Imagery. Sensors 2025, 25, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ICCV) 2015, pp. 1440–1448.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV) 2016, pp. 21–37.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement, 2018, [arXiv:cs.CV/1804.02767].

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ICCV) 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2017, pp. 2117–2125.

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2018, pp. 8759–8768.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2020, 10778–10787. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.; Chen, X.; Fan, Z.; Zeng, G.; Li, H.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, J. Conditional DETR for Fast Training Convergence. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ICCV) 2021, 3631–3640. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Qi, X.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. DAB-DETR: Dynamic Anchor Boxes are Better Queries for DETR. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Sun, J. Anchor DETR: Query Design for Transformer-Based Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2109.07107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Ai, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, C. Efficient DETR: Improving End-to-End Object Detector with Dense Prior. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.01318. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Ni, L.M.; Zhang, L. DN-DETR: Accelerate DETR Training by Introducing Query DeNoising. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2022, 13619–13627. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.Y. DINO: DETR with Improved DeNoising Anchor Boxes for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03605. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2024, 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Shen, W.; Hu, T.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Huang, J. Dynamic-DETR: Dynamic Perception for RT -DETR. Proc. Int. Conf. Robot. Comput. Vis. (ICRCV) 2024, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Gan, Z.; Zhu, G.N. UAV-DETR: Efficient End-to-End Object Detection for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01855. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Lu, Z.; Cun, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X. DEIM: DETR with Improved Matching for Fast Convergence. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2025, 15162–15171. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, E.O.; Morrow, R.E. The fast Fourier transform. IEEE Spectr. 1967, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network In Network. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1312.4400. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV) 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

| Model Scale | Backbone Size | Returned Stages | D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | B0 | , | (512, 1024, –) | (16, 32, –) | 128 |

| S | B0 | , , | (256, 512, 1024) | (8, 16, 32) | 256 |

| M | B2 | , , | (384, 768, 1536) | (8, 16, 32) | 256 |

| X | B5 | , , | (512, 1024, 2048) | (8, 16, 32) | 384 |

| Model | InputSize | Param(M) | GFLOPs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-FINE-N [3] | 640 × 640 | 69.0 | 41.0 | 3.6 | 7.1 |

| D-FINE-S [3] | 640 × 640 | 76.0 | 46.7 | 9.7 | 24.8 |

| D-FINE- [3] | 640 × 640 | 76.1 | 47.7 | 18.3 | 56.4 |

| D-FINE- [3] | 640 × 640 | 78.5 | 48.5 | 58.7 | 202.2 |

| OPGW-DETR-N(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 71.3 | 42.2 | 4.8 | 9.7 |

| OPGW-DETR-S(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 78.5 | 50.6 | 17.2 | 68.9 |

| OPGW-DETR-(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 78.3 | 49.8 | 25.8 | 100.4 |

| OPGW-DETR-(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 77.3 | 48.8 | 75.6 | 301.3 |

| Model | InputSize | Param(M) | GFLOPs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-DETR-R50 [24] | 640 × 640 | 70.9 | 45.2 | 40.8 | 130.5 |

| RT-DETR-R101 [24] | 640 × 640 | 72.8 | 46.7 | 58.9 | 191.4 |

| RT-DETR-X [24] | 640 × 640 | 74.1 | 46.3 | 65.5 | 222.5 |

| UAV-DETR-Ev2 [26] | 640 × 640 | 71.2 | 43.0 | 12.6 | 44.0 |

| UAV-DETR-R18 [26] | 640 × 640 | 72.6 | 44.7 | 20.5 | 73.9 |

| UAV-DETR-R50 [26] | 640 × 640 | 75.4 | 47.1 | 43.4 | 166.4 |

| YOLOv9-T [31] | 640 × 640 | 68.5 | 41.7 | 1.9 | 7.9 |

| YOLOv9-S [31] | 640 × 640 | 72.8 | 46.8 | 6.9 | 27.4 |

| YOLOv10-S [32] | 640 × 640 | 69.6 | 44.3 | 7.7 | 24.8 |

| YOLOv10-N [32] | 640 × 640 | 64.0 | 39.0 | 2.6 | 8.4 |

| OPGW-DETR-N(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 71.3 | 42.2 | 4.8 | 9.7 |

| OPGW-DETR-S(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 78.5 | 50.6 | 17.2 | 68.9 |

| OPGW-DETR-(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 78.3 | 49.8 | 25.8 | 100.4 |

| OPGW-DETR-(Ours) | 640 × 640 | 77.3 | 48.8 | 75.6 | 301.3 |

| Baseline | MC-GAP | Gate | Params(M) | GFLOPs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 9.7 | 24.8 | 74.6 | 46.3 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 17.1 | 67.8 | 78.4 | 49.4 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 17.2 | 68.9 | 78.5 | 50.6 |

| Features | Level | / | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | ||||

| Mid | ||||

| High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).