1. Introduction

More than 1.5 billion people are at risk of soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH), with the majority residing in sub-Saharan Africa [

1,

2,

3]. STH continues to be a neglected tropical disease of public health importance and is targeted for control by 2030 [

2,

3].

Ascaris lumbricoides,

Trichuris trichiura, and hookworms (

Necator americanus and

Ancylostoma duodenale) are the four common parasitic nematodes causing STH, and are intensively transmitted in areas where inadequate sanitation, unsafe water, and poor hygiene practices persist [

4,

5,

6,

7]. School-aged children are particularly vulnerable and have been the target of existing preventive chemotherapy control programs, which involve the mass administration of albendazole or mebendazole (MDA) without prior diagnosis in endemic areas [

3,

8,

9]. Over the past decade, the World Health Organisation has supported PC programs by distributing over 600 million donated anthelmintic medicines [

10].

The implementation of PC programs is guided by endemicity thresholds at the implementing unit (IU), usually the local government areas (LGAs), districts, or provinces [

9]. For instance, biannual PC (twice-per-year mass administration) is implemented in areas where prevalence exceeds 50%, annual PC is implemented in areas where prevalence is between 20–49.9%, and clinical case management is implemented when prevalence is below 20% [

9,

10]. As part of programmatic guidelines, PC program is considered only effective on the parasite population when more than 75% of the targeted school-aged children within an IU receive treatment, over a sustained period of 5-6 years [

10]

PC programs for STH are expensive and do not need to continue when the endemic threshold falls below 20% [

15]. Updating the STH endemicity map through impact assessments is therefore recommended after 5-6 years of effective implementation to determine program effectiveness, optimise resource allocation, and ascertain progress toward elimination [

10]. Nigeria remains the most highly endemic country for STH in sub-Saharan Africa [

11,

12]. With extensive PC campaigns implemented over five years in Ondo State [

13], it is expected that formerly endemic areas may now have reduced transmission. A recent evaluation of the endemicity of STH in three LGAs in Ondo State highlighted the need for an update on the endemicity profile in other LGAs [

13]. Hence, in this study, we evaluated STH prevalence and intensity across ten LGAs with varying PC exposure histories to evaluate the impact of the PC program and update the state STH endemicity map.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study received approval from the Ondo State Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC/18/08/2016) and the Federal Ministry of Health Neglected Tropical Diseases Unit (NSCP/6/7/IV/23). Community sensitisation meetings were conducted, and written consent from parents/guardians and assent from children (5–14 years) were obtained prior to participation.

2.2. Study Area

Ondo State is in the southwest zone of Nigeria, comprising 18 LGAs and 206 wards, with a population exceeding three million. The tropical climate and diverse vegetation zones (freshwater swamps, rainforests, and Guinea savannah) influence helminth transmission dynamics. The state contains numerous rivers and ponds that support agriculture, fishing, and recreational activities, which increase the risk of water-related exposure. The state has a population of 5,540,403, of which 1,551,313 are SAC [

13].

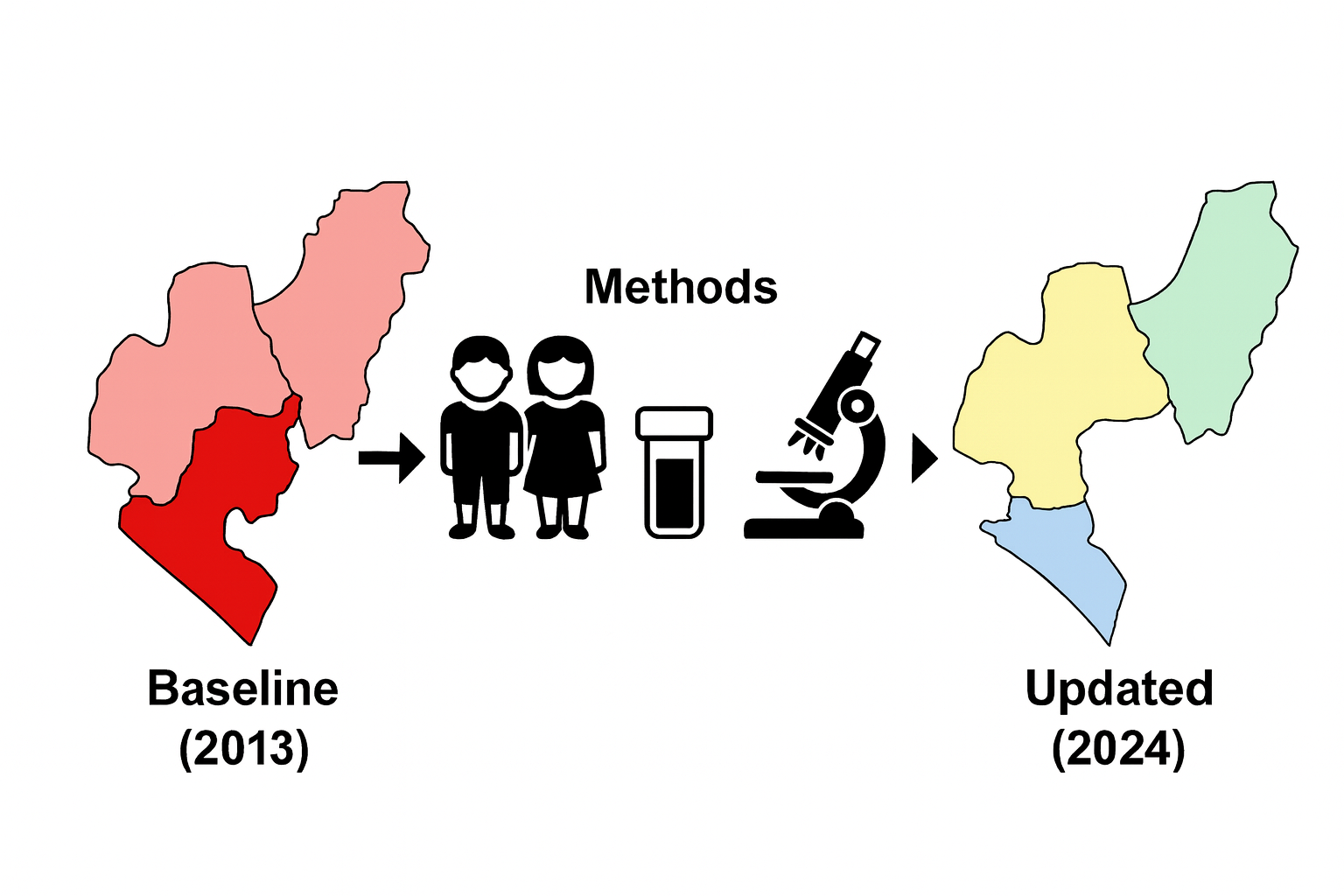

2.3. Selection of Study LGAs

Baseline epidemiological mapping for STH in Ondo revealed that 12 LGAs had endemicity between 20-50%, and 2 LGAs had endemicity >50% [

14]. These endemic LGAs benefited from an average of nine rounds of PC with albendazole. Hence, for this study, we selected LGAs based on their baseline prevalence and PC history. We stratified into three categories (C1-C3), with C1 being endemic LGAs with ≥ 5 effective rounds of PC (n=9), C2 being endemic LGAs with < 5 effective rounds of PC (n=5), and C3 being low endemicity (STH prevalence <20%; PC not required, n=4). In C1, three LGAs (Ese-Odo, Ile-Oluji, and Irele) had been previously assessed, with findings published elsewhere [

13], and were excluded from the sampling frame. Of the remaining six LGAs, four (Akoko Southwest, Akure North, Ifedore, and Ondo East) were selected for the study. In C2, four LGAs (Akure South, Ose, Owo, and Odigbo) were selected, and in C3, two LGAs (Idanre and Akoko Northwest) were selected. The selection of LGAs across all categories was purposive, guided by the need to include areas co-endemic for schistosomiasis, which allowed for an integrated assessment of both diseases and ensured optimal use of available resources (

Figure 1).

2.4. Study Design and Sampling

We employed a cross-sectional sampling design and collected stool samples and questionnaire data from school-aged children (SAC) between July and August of 2024. SAC were sampled across 151 systematically selected communities (15 per LGA) in ten LGAs using methods previously described [

13]. The sample size followed WHO guidelines of recruiting 30 SAC per community [

15].

2.5. Stool Collection and Processing

Fresh stool samples were collected from the participating school children with the help of their parents and teachers. A pre-labelled sterile specimen bottle was provided and retrieved from the SAC after 1 h of distribution and specimens. Participants were provided with applicator sticks, plain sheets of paper, tissue paper, and soap to assist with stool collection. Samples were transported in iceboxes to the laboratory at the Ondo State College of Health Technology, Akure, for processing using the Kato-Katz technique within two hours of collection. A single thick smear was prepared from each sample and allowed to clear for 30 min. The smears were examined microscopically for Ascaris, Trichuris, or hookworm parasite eggs. For quality assurance, each slide was re-examined by a second microscopist, and the egg counts were verified. A participant was classified as positive if at least one egg from any target parasite was detected per slide.

2.6. Questionnaire Administration

We utilised closed-ended electronic questionnaires deployed on Kobocollect platform to collect demographic data, including age and sex, and document parasitological results from examined stool samples. Interviews were conducted in either Yoruba or English and held confidentially, with a legal guardian or parent present when necessary.

2.7. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using R Studio (version 4.3.2). The overall infection status (i.e. any STH infection) and species-specific prevalence were determined using the WHO threshold (<2%, 2% to <10%, 10% to <20%, and ≥20%). Intensity was expressed as eggs per gram (EPG), as described previously [

13]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise categorical variables, with a 95% confidence interval computed for proportions. Risk Ratio were also used to compute the impact of PC between baseline and endline estimates. Spatial distribution maps of STH across the LGAs were generated using ArcGIS version 10.8.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Table 1. presents a comprehensive profile of the study locations in the LGAs. The coverage within the subunits of the LGAs ranged from 73.3% to 100%, with Akure North being the only LGA to achieve full coverage across its subunits. Other LGAs encountered challenges such as insecurity, which limited their coverage. Despite these challenges, the number of communities sampled exceeded the target (151 vs. 150), as did the total number of participants recruited (4,507 vs. targeted 4,500). Although most LGAs surpassed their target sample size, a few recruited fewer participants than anticipated: Akure South (n=421, 93.6%), Ifedore (n=444, 98.7%), and Owo (n=430, 95.6%). Stool and urine samples were collected from 98.7% of the participants. There were no significant differences in recruitment by gender (p = 0.063) and age (p =0.061), although slightly more younger children aged 5-9 years (n=2,300, 51%) were recruited than those aged 10-15 years (n=2,207, 49%). (

Table 3).

Table 1.

Profile of study locations and participants.

Table 1.

Profile of study locations and participants.

| |

|

Endemic LGAs with ≥ 5 effective rounds |

Endemic LGAs with ≤ 5 effective rounds |

Low endemicity and no PC required |

| |

|

AKSW |

AKN |

IFE |

ONE |

AKS |

OSE |

OWO |

ODI |

IDA |

AKNW |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Administrative units |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of sub-units/wards |

112 |

15 |

12 |

10 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

11 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

| Sub-units/wards surveyed |

95 (84.8) |

11 (73.3) |

12 (100) |

9 (90.0) |

9 (90.0) |

9 (81.8) |

9 (75.0) |

9 (81.8) |

9 (81.8) |

9 (90.0) |

9 (90) |

| Communities targeted |

150 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

| Number of communities surveyed |

151 (100.6) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

16 (106.7) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

15 (100) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Study participants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SAC targeted |

4500 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

450 |

| SAC recruited |

4507 (100.1) |

460 (102.2) |

454 (100.9) |

444 (98.7) |

471 (104.7) |

421 (93.6) |

451 (100.2) |

430 (95.6) |

453 (100.7) |

450 (100) |

473 (105.1) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Demography |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Females |

2,272 (50.4) |

221 (48) |

251 (55) |

235 (53) |

234 (50) |

191 (45) |

241 (53) |

223 (52) |

232 (51) |

225 (50) |

219 (46) |

| Males |

2,235 (49.6) |

239 (52) |

203 (45) |

209 (47) |

237 (50) |

230 (55) |

210 (47) |

207 (48) |

221 (49) |

225 (50) |

254 (54) |

| Age [5-9years] |

2,300 (51) |

238 (52) |

210 (46) |

227 (51) |

255 (54) |

219 (52) |

258 (57) |

212 (49) |

204 (45) |

235 (52) |

242 (51) |

| Age [10-14years] |

2,207 (49) |

222 (48) |

244 (54) |

217 (49) |

216 (46) |

202 (48) |

193 (43) |

218 (51) |

249 (55) |

215 (48) |

231 (49) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Samples collected |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of SAC with stool* |

4449 (98.7) |

456 (99.1) |

452 (99.6) |

444 (100) |

441 (93.6) |

416(98.8) |

447 (99.1) |

430 (100) |

453 (100) |

450 (100) |

459 (97.0) |

3.2. Prevalence and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis Across the LGAs

Table 2 summarises the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) across local government areas (LGAs). Across the LGAs surveyed, the prevalence of any soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infection significantly decreased during the impact assessment compared to baseline levels. In the first category, the baseline prevalence was reduced significantly by 60-96%. In Akoko Southwest, the prevalence of any STH decreased from 28.2% to 0.4%, resulting in a 99% reduction and a risk ratio of 0.01. In Akure North, the prevalence decreased from 39% at baseline to 1.5%, resulting in a 96.2% reduction, with a risk ratio of 0.04. Ifedore experienced a decrease from 25% to 2.5%, representing a 90% reduction, with a risk ratio of 0.10. Ondo East recorded a decrease from 45.2% to 8.2%, resulting in an 81.9% reduction and a risk ratio of 0.18.

In the second category, endemicity from baseline was reduced significantly by 66-100%. Akure South experienced a reduction from 29% to 1.2%, leading to a 95.9% decrease and a risk ratio of 0.04. In Ose, the prevalence decreased from 20% to 2.2%, leading to an 89% reduction, with a risk ratio of 0.11. In Owo, no infections were detected during the impact assessments, leading to a 100% reduction. Odigbo showed a reduction from 38% to 12.8%, marking a 66.3% decrease and a risk ratio of 0.34.

In the third category, infections were significantly below the baseline threshold. In Akoko Northwest, there was a significant decrease of 82% from 5.2% baseline prevalence to 0.9%. In Idanre, there was a reduction from 14.2% at baseline to 1.8%, reflecting an 87.3% decrease and a risk ratio of 0.13. Overall, significant reductions in STH prevalence were observed across the surveyed LGAs, with risk ratios ranging from 0.04 to 0.40 (

Table 2). Additionally, there were no moderate or heavy infections in any STH species (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthiasis across LGAs and comparisons with the baseline survey.

Table 2.

Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthiasis across LGAs and comparisons with the baseline survey.

| |

|

|

Impact assessment |

Baseline |

Comparisons |

| |

|

|

Ascaris lumbricoides |

Hookworm |

Trichuris trichiura |

Any STH |

Any STH |

Any STH |

| |

|

N |

n(%) |

95% CI |

n(%) |

95% CI |

n(%) |

95% CI |

n (%) |

95% CI |

% |

RR |

d |

| Endemic LGAs with ≥ 5 effective rounds |

AKSW |

460 |

1 (0.2%) |

-0.21, 0.64 |

1 (0.2%) |

-0.21, 0.64 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

2 (0.4%) |

-0.17,1.04 |

28.2 |

0.01 |

-99.9 |

| AKN |

452 |

6 (1.3%) |

0.27, 2.38 |

0 (0.0% |

- |

1 (0.2%) |

-0.21,0.65 |

7 (1.5%) |

0.41, 2.68 |

39 |

0.04 |

-96.2 |

| IFE |

444 |

8 (1.8%) |

0.56,3.04 |

2 (0.5%) |

-0.17, 1.07 |

1 (0.2%) |

-0.22,0.67 |

11 (2.5%) |

1.03, 3.92 |

25 |

0.10 |

-90.0 |

| ONE |

471 |

27 (6.1%) |

3.63, 7.83 |

10 (2.3%) |

0.82, 3.43 |

1 (0.2%) |

-0.20, 0.62 |

36 (8.2%) |

5.24, 10.04 |

45.2 |

0.18 |

-81.9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endemic LGAs with ≤ 5 effective rounds |

AKS |

421 |

3 (0.7%) |

-0.09, 1.51 |

2 (0.5%) |

-0.18,1.13 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

5 (1.2%) |

0.15, 2.22 |

29 |

0.04 |

-95.9 |

| OSE |

451 |

2 (0.4%) |

-0.17,1.05 |

8 (1.8%) |

0.56, 2.99 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

10 (2.2%) |

0.86, 3.58 |

20 |

0.11 |

-89.0 |

| OWO |

430 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

43 |

0.00 |

-100 |

| ODI |

453 |

34 (7.5%) |

5.08, 9.93 |

29 (6.4%) |

4.15, 8.66 |

2 (0.4%) |

-0.17, 1.05 |

58 (12.8%) |

9.73, 15.9 |

38 |

0.34 |

-66.3 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low endemicity and no PC required |

IDA |

450 |

5 (1.1%) |

0.14,2.07 |

3 (0.7%) |

-0.08, 1.41 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

8 (1.8%) |

0.55,2.99 |

14.2 |

0.13 |

-87.3 |

| AKNW |

473 |

2 (0.4%) |

-0.16, 1.01 |

2 (0.4%) |

-0.16, 1.01 |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

4 (0.9%) |

0.02-1.67 |

5.2 |

0.17- |

-82.7 |

Table 3.

Intensity of soil-transmitted helminthiasis infections across the LGAs.

Table 3.

Intensity of soil-transmitted helminthiasis infections across the LGAs.

| |

|

Endemic LGAs with ≥ 5 effective rounds |

Endemic LGAs with ≤ 5 effective rounds |

Low endemicity and no PC required |

| |

|

AKSW |

AKN |

IFE |

ONE |

AKS |

OSE |

OWO |

ODI |

IDA |

AKNW |

| N |

4507 |

460 |

454 |

444 |

471 |

421 |

451 |

430 |

453 |

450 |

473 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ascaris lumbricoides |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

4,364 (98.0%) |

455 (99.8%) |

446 (98.7%) |

436 (98.2%) |

414 (93.9%) |

414 (99.3%) |

446 (99.6%) |

430 (100.0%) |

419 (92.5%) |

445 (98.9%) |

459 (99.6%) |

| Light infection |

88 (2.0%) |

1 (0.2%) |

6 (1.3%) |

8 (1.8%) |

27 (6.1%) |

3 (0.7%) |

2 (0.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

34 (7.5%) |

5 (1.1%) |

2 (0.4%) |

| Moderate infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Heavy infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hookworms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

4,395 (98.7%) |

455 (99.8%) |

452 (100.0%) |

442 (99.5%) |

431 (97.7%) |

415 (99.5%) |

440 (98.2%) |

430 (100.0%) |

424 (93.6%) |

447 (99.3%) |

459 (99.6%) |

| Light infection |

57 (1.3%) |

1 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.5%) |

10 (2.3%) |

2 (0.5%) |

8 (1.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

29 (6.4%) |

3 (0.7%) |

2 (0.4%) |

| Moderate infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Heavy infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Trichuris trichiura |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

4,447 (99.9%) |

456 (100.0%) |

451 (99.8%) |

443 (99.8%) |

440 (99.8%) |

417 (100.0%) |

448 (100.0%) |

430 (100.0%) |

451 (99.6%) |

450 (100.0%) |

461 (100.0%) |

| Light infection |

5 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (0.2%) |

1 (0.2%) |

1 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Moderate infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Heavy infection |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

3.3. Programmatic Interpretation of STH Prevalence Data Across the LGAs

Table 4 presents the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations for MDA based on the varying prevalence of STH. For LGAs with a prevalence rate between 0-2%, the recommended action is to conduct MDA during selected events and to establish and maintain surveillance. The LGAs in this category include Owo, which has a prevalence rate of 0%, Idanre at 1.8%, Akoko Southwest at 0.4%, Akure South at 1.2%, Akoko Northwest at 0.9%, and Akure North at 1.5%. These areas are considered low-risk for STH and require careful monitoring to ensure that their prevalence remains low. In the 2-10% prevalence category, the recommendation is to conduct MDA once every two years for five years, along with establishing and maintaining surveillance. The LGAs that fall under this category are Ifedore (2.5 %), Ondo East (8.2 %), and Ose (2.2 %). These areas are recognised as having moderate prevalence, necessitating more frequent interventions to prevent escalation and sustain public health. For LGAs with a prevalence between 10-20%, MDA should be conducted once for five years, combined with ongoing surveillance. Odigbo was the only LGA identified in this category, with a prevalence rate of 12.8%. This area presents a greater concern and requires targeted interventions to mitigate health risks effectively (

Figure 2).

3.4. Elimination Insights for STH Across Ten LGAs

All LGAs met the first (prevalence is less than 20%) and second (prevalence of MHI infection is less than 2%) conditions outlined by the WHO for progressing towards elimination. However, open defaecation, which is a proxy for poor WASH access, is still a predominant practice across the LGA (ranging from 8.9-60.1%). In addition, MDA programs are still largely targeted at SAC and seldom delivered to WRA during community-based interventions involving the treatment of lymphatic filariasis. Efforts to improve WASH and expand MDA to WRA are essential (

Table 5;

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This impact assessment shows substantial progress in STH elimination in Ondo State. LGAs with ≥5 effective PC rounds achieved the greatest reduction, highlighting the value of sustained coverage. LGAs with fewer PC rounds and non-endemic LGAs exhibited significant reductions in STH prevalence. The importance of this assessment is threefold: first, to determine the effectiveness of preventive chemotherapy (PC) in reducing worm burden; second, to prevent misallocation of resources to areas where interventions are no longer necessary, thus optimising investment in underserved regions; and third, to generate evidence essential for tracking progress and refining PC programs for maximum impact [

15]. Across all four endemic LGAs that completed the

required PC rounds, the prevalence declined by 81–99%. Endemic LGAs with fewer than five effective PC rounds recorded reductions of 66–100%. For the Lowly endemic LGAs with baseline prevalence below 20% and where no PC is required, there was also a positive decline between 82.7% and 87.3%. Overall, LGAs with more than five years of effective implementation experienced the largest reduction. These findings align with other evidence on the impact of effective PC [

13,

16]. Infection intensity, a more reliable measure of disease burden, remains very low across all LGAs and met WHO targets of reducing the prevalence of moderate or heavy intensity of infection to below 2% [

15].

Programmatically, two LGAs (Akure South-west and Akure North) with 5 rounds of effective PC no longer require MDA, while two others (Ifedore and Ondo East) will need biennial MDA for the next five years. Two LGAs (Owo and Akure South) with less than five required rounds of PC no longer require MDA, while Ose LGA requires biennial and Odigbo LGA require annual MDA for the next five years. These findings reinforce the importance of completing at least five effective rounds of MDA, especially in LGAs with baseline endemicity [

13,

15,

16].

Achieving STH elimination requires four conditions: (1) reducing overall prevalence to <20%; (2) reducing moderate/heavy infections to <2%; (3) ensuring treatment coverage among women of reproductive age (WRA); and (4) improving access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), particularly eliminating open defecation. All LGAs met the first two conditions, but progress on WRA coverage and WASH remains limited. Open defecation remains common and threatens the sustainability of gains. Recent evidence from within the shows that poor hygiene practices—especially not washing hands with soap after defecation – pose the highest infection risk, followed by unimproved latrines and unsafe water sources [

13]. Similar findings have been reported in Ethiopia [

17], Angola [

18] and Kenya [

19], where inadequate WASH infrastructure undermined the success of PC outcomes [

19,

20]. Integrating strong WASH intervention into PC program is therefore essential for long-term success [

21].

From a policy perspective, these results emphasise the continued need for MDA investment, regular impact assessments, and complementary WASH interventions. A major strength of the study is its inclusion of both enrolled and non-enrolled school-aged children, reducing bias inherent in school-based sampling. Although deworming through Lymphatic Filariasis program - albendazole and ivermectin – may have contributed to observed reductions, this reflects real-world implementation. A key limitation is the absence of baseline WASH, which restricts assessment of WASH-related progress over time.

5. Conclusion

Preventive chemotherapy has significantly reduced STH prevalence and intensity across Ondo State. To maintain progress toward elimination, integrated strategies combining PC, WASH improvement, and expanded coverage for women of reproductive age are essential.

Author Contributions

UFE, HOM conceptualised the study; UFE, HOM prepared the protocol; JS, FOO, FO, IA, OOO, AYK, FO participated in supervised field surveys and data collection; HOM performed all statistical analyses; HOM prepared the first draft of the manuscript; UFE, MA, LKM, FOO revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to the development of the final manuscript and approved its submission.

Funding

This study was funded by The Ending Neglected Diseases (END) Fund. The funder has no specific role in the conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study can be obtained upon reasonable request from mogajihammed@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the community leaders, health workers, education secretaries, and staff of the NTDs Control Department, Ondo State Ministry of Health, for their unwavering support and cooperation throughout this study. We sincerely acknowledge the contributions of individuals who served as field supervisors, technicians, interviewers, and members of the technical support team. We also appreciate the broader health community for their support and collaboration in this endeavour.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hotez, PJ; Kamath, A. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009, 3, e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO); World Health Organisation. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030; Geneva; Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Fact Sheet: Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Ziegelbauer, K; Speich, B; Mäusezahl, D; Bos, R; Keiser, J; et al. Effect of sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunz, EC; Addiss, DG; Stocks, ME; Ogden, S; Utzinger, J; et al. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarini-Serra, L. Prevention of Soil-transmitted Helminth Infection. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011, 3, 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekpo, UF; Mogaji, HO. Feasibility of Helminth Worm Burden as a Marker for Assessing the Impact and Success of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions (WASH) for the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases. NJPAR. 2023, (1). Available online: https://njpar.com.ng/index.php/home/article/view/382.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Preventive Chemotherapy. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/interventions/strategies/preventive-chemotherapy (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Helminth Control in School-Age Children: A Guide for Managers of Control Programmes. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/resources/9789241548267/en/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Montresor, A; Mupfasoni, D; Mikhailov, A; Mwinzi, P; Lucianez, A; et al. The global progress of soil-transmitted helminthiases control in 2020, and World Health Organisation targets for 2030. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020, 14, e0008505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyeyemi, OT; Okunlola, OA. Soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) endemicity and performance of preventive chemotherapy intervention programme in Nigeria (in year 2021). Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotez, PJ; Asojo, OA; Adesina, AM. Nigeria: “Ground Zero” for the high prevalence of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012, 6, e1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogaji, HO; Olamiju, FO; Oyinlola, F; Achu, I; Adekunle, ON; Udofia, LE; Edelduok, EG; Yaro, CA; Oladipupo, OO; Kehinde, AY; Oyediran, F; Aderogba, M; Makau-Barasa, LK; Ekpo, UF. Prevalence, intensity and risk factors of soil-transmitted helminthiasis after five effective rounds of preventive chemotherapy across three implementation units in Ondo State, Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2025, 19, e0012533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nduka, F; Nebe, O J; Njepuome, N.; et al. Epidemiological mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis for intervention strategies in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 2019, 40, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Assessing schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases control programmes: monitoring and evaluation framework Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379352/9789240099364-eng.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Okoyo, C; Campbell, SJ; Williams, K; Simiyu, E; Owaga, C; et al. Prevalence, intensity and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Kenya: Impact assessment after five rounds of mass drug administration in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. Available at. 2020, 14, e0008604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, AE; Ower, AK; Mekete, K; Liyew, EF; Maddren, R; et al. Association between water, sanitation, and hygiene access and the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Wolayita, Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors 2022, 15, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, AW; Mendes, EP; Dahmash, L; Palmeirim, MS; de Almeida, MC; et al. School-based preventive chemotherapy program for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth control in Angola: 6-year impact assessment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0010849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwandawiro, C.; Okoyo, C.; Kihara, J.; Simiyu, E; Kepha, S; et al. Results of a national school-based deworming programme on soil-transmitted helminths infections and schistosomiasis in Kenya: 2012–2017. Parasit Vectors Available at. 2019, 12(1), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olamiju, F; Nebe, OJ; Mogaji, H; Marcus, A; Amodu-Agbi, P; et al. Schistosomiasis outbreak during COVID-19 pandemic in Takum, Northeast Nigeria: Analysis of infection status and associated risk factors. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogaji, HO; Dedeke, GA; Jaiyeola, OA; Adeniran, AA; Olabinke, DB; et al. A preliminary survey of school-based water, sanitation, hygiene (WASH) resources and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in eight public schools in Odeda LGA, Ogun State, Nigeria. Parasitol Open. 2017, 3, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).