1. Introduction – Why Tailings Recovery Matters Now

Across every continent, legacy mine tailings are accumulating faster than they are being rehabilitated. Each tonne of concentrate generates several tonnes of fine waste stored in impoundments requiring long-term monitoring. These deposits are both a liability and a latent resource, containing metals now designated as critical by major industrial economies. Studies show that germanium, gallium, and indium remain in high demand for advanced electronics and low-carbon technologies, reflecting persistent supply-security risks [

1]. Historically, tailings were dismissed as uneconomic because earlier mining focused on a few commodities, used higher cut-off grades, and lacked technologies to recover minor elements. As a result, many legacy deposits contain metals suitable for modern applications [

2].

Recent U.S. International Trade Commission analyses show how Chinese export controls on germanium and gallium reshaped strategic-material markets and exposed downstream industries to greater vulnerability [

3]. These shifts have prompted governments and manufacturers to pursue recovery from legacy mine waste to reduce reliance on concentrated imports. The European Critical Raw Materials Act supports recovery of strategic elements from mine waste and industrial residues to strengthen supply security and circularity, calling on Member States to improve information access and remove regulatory, economic, and technical barriers [

4].

At the same time, the environmental and social consequences of tailings mismanagement have become increasingly visible. The 2014 Mount Polley incident in Canada [

5] and the 2019 Brumadinho collapse in Brazil, which killed 248 people [

6], showed how failures can escalate into major humanitarian and environmental disasters. These events have reshaped how investors, insurers, and regulators perceive mining risk, with liability now influencing access to capital, project approvals, and community trust. This duality – tailings as both risk and resource – defines a central challenge for the mining sector. Facilities that require long-term storage could, if responsibly reprocessed, yield cobalt, nickel, tungsten, and rare earths needed for low-carbon technologies.

The Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management highlights that large volumes of tailings worldwide require responsible storage aligned with best practice [

7]. Unlocking even a modest fraction could reduce pressure on new greenfield projects, shorten permitting cycles, and improve the sector’s overall footprint [

7].

Addressing this opportunity requires more than technology. It demands governance, transparency, and intelligent systems linking technical feasibility with social responsibility. This paper integrates developments across three fronts: (i) governance standards including GISTM, MAC, and LPSDP, (ii) disclosure practices that make facility data accessible, and (iii) data-driven methods using artificial intelligence to prioritise sites, design flowsheets, and assess ESG performance. The result is a Responsible Recovery framework connecting risk management, process technology, and verifiable disclosure into a single auditable chain. Before technological solutions can scale, governance structures must provide a consistent basis for accountability and public confidence.

2. Governance and Disclosure Landscape

Tailings governance has evolved from an internal engineering matter into a multi-stakeholder discipline that shapes how mining companies are evaluated by investors, regulators, and society. The 2020 Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) established the first international baseline for accountability and disclosure [

7]. Informed by the Global Tailings Review, it introduced consequence-based classifications of tailings storage facilities (TSFs), strengthened independent review, enhanced emergency preparedness, reinforced corporate accountability, and expanded public disclosure [

8]. Its 15 principles span the full facility life-cycle and require each company to appoint an “Accountable Executive” responsible for performance and reporting. The standard was developed through a global consultation process involving online submissions and in-country discussions in Australia, Chile, China, Ghana, Kazakhstan, and South Africa, ensuring broad stakeholder input [

9]. Global distribution of these mining regions is shown schematically in

Figure 1.

This shift reflects wider recognition that catastrophic failures rarely arise from a single technical flaw, but from gaps in organisational awareness, unclear accountability, or inconsistent controls. Since 2020, governance frameworks have therefore moved toward system-wide alignment, requiring operators to integrate governance, risk management, and disclosure within a coherent corporate structure. This evolution underpins the operational guidance developed by national associations and regulators.

The Mining Association of Canada (MAC) Tailings Management Protocol anchors its performance system in the Tailings Guide and the Operation, Maintenance and Surveillance Manual for Tailings and Water Management Facilities (OMS Guide), emphasising that safe management depends on sound engineering applied consistently throughout the life-cycle [

10]. Roles are clearly defined: the Engineer-of-Record (EoR) acts as the Owner’s technical authority, verifying design, construction, and performance against objectives, indicators, standards, and legal requirements [

10]. Independent Review provides third-party assessment of planning, design, operation, and maintenance, ensuring that changes, including potential reprocessing, are evaluated against original design intent. Critical controls are those essential to preventing high-consequence events or mitigating their effects, and their absence significantly increases overall risk [

10].

National and regional frameworks complement this architecture. Canada’s MAC Tailings Guide and Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) protocols connect GISTM principles to detailed checklists [

10]. Australia’s Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program (LPSDP) and the UNECE Global Tailings Review introduce environmental metrics and harmonised terminology. South Africa’s Mining and Biodiversity Guideline highlights the need to align land-use planning, ecological assessment, and post-closure stewardship with broader sustainability objectives [

11].

The Global Tailings Management Institute (GTMI) provides the assurance mechanism through which GISTM is implemented and externally verified. As an independent non-profit co-founded by ICMM, UNEP, and the PRI, it oversees conformance, accredits auditors, and reinforces accountability through public disclosures by mining companies [

12].

Reprocessing and tailings minimisation are emphasised in the LPSDP handbook as strategies for reducing long-term storage risk, noting that many streams retain recoverable value as technologies advance. It cautions against disposal approaches that could render future recovery uneconomic and identifies uses that may reduce storage requirements and support resource efficiency [

13].

Major mining companies now publish portfolio-wide conformance statements. Anglo American provides a leading example, reporting facility-level data across multiple jurisdictions through GISTM Stage-5 submissions [

14]. These disclosures include consequence classifications, assurance cycles, audit findings, and closure progression, enabling benchmarking and identification of candidate sites for reprocessing.

However, inconsistencies persist. Terminology varies, assurance intervals differ, and most disclosures emphasise governance indicators rather than process parameters such as deposition method, water balance, or geochemistry. Without harmonised schemas, comparisons remain difficult and automated extraction unreliable.

These gaps highlight the need for a unified structure that makes facility data comparable across sites and jurisdictions. A minimum fields list provides that step by aligning common elements from GISTM, MAC, LPSDP, and UNECE guidance into a standard dataset for assessing risk, reprocessing readiness, and compliance. When organised in this way, disclosure can feed directly into intelligent tools for site screening and ESG evaluation, turning reporting into a practical digital layer for Intelligent Green Mining.

3. The Responsible Recovery Framework

Most tailings standards focus on preventing harm, but the Responsible Recovery framework extends this logic toward creating value under the same governance discipline. Its core premise is that decisions to reprocess mine waste should meet the same standards of accountability, transparency, and risk control that apply to new mining operations, shifting the narrative from waste management to resource stewardship.

Uptake of reprocessing remains limited, and professional familiarity is equally scarce. A recent industry-wide survey found that only 24 percent of Qualified Persons had evaluated a tailings-reprocessing project, indicating a significant capability gap within the sector [

15]. This suggests that expertise in tailings characterisation, metallurgical recovery, and risk-modelling remains unevenly distributed, even among senior practitioners. For reprocessing to become a mainstream operating model, routine familiarity with these competencies must increase. Moreover, the 24 percent figure may overstate experience. Survey authors noted that it is likely inflated by self-selection bias, implying that the proportion of Qualified Persons with first-hand involvement in reprocessing is probably even lower [

15]. Combined with emerging evidence from legacy sites, this underscores the need for a coherent, stepwise method to assess recovery potential responsibly.

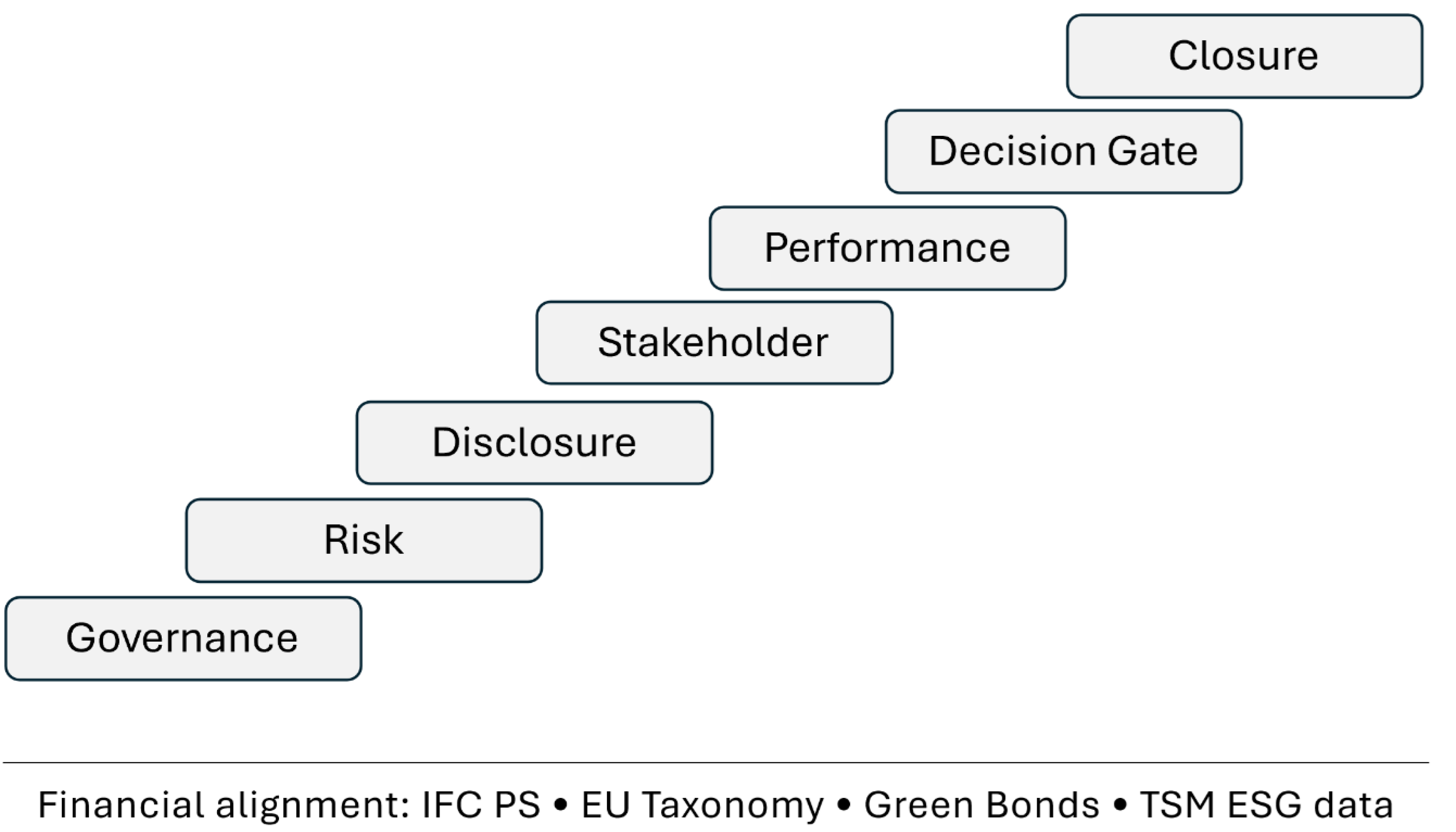

The framework is organised around seven checkpoints that translate high-level ESG principles into auditable project milestones. International guidance emphasises that tailings recovery must be embedded within formal corporate policy, endorsed at executive level, and aligned with broader commitments to responsible tailings management [

10]. Under the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management, each operator must designate an Accountable Executive with overarching responsibility for safety, environmental performance, and governance, also including a clear approval of design criteria, oversight of emergency preparedness, and appointment of key technical roles such as the Responsible Tailings Facility Engineer (RTFE), Engineer of Record (EoR), and independent reviewers [

7].

Governance and accountability

A named executive must hold responsibility for tailings recovery, with roles documented in the corporate management system and aligned with MAC and GISTM requirements. This ensures recovery is treated as a governed function rather than a technical add-on.

Risk and consequence class

Facilities must be reassessed using updated risk matrices that cover structural stability, flow, reagent hazards, and risks introduced by reprocessing. This ensures consequence classifications reflect legacy conditions and new operational realities, supporting clear communication.

Disclosure and assurance

Recovery data – including test work, pilots, and environmental monitoring – should follow the same cadence and structure as GISTM reporting. Independent assurance strengthens confidence in consistency and prevents selective disclosure, enabling long-term tracking of progress.

Stakeholder engagement and emergency readiness

Communities and authorities must be informed of risks and potential benefits through clear communication protocols, access to monitoring data, and demonstrated emergency preparedness. This sustains social licence and continuity with previous stewardship obligations.

Performance KPIs

Indicators such as recovery efficiency, energy and water intensity, reagent use, and residual toxicity translate outcomes into governance metrics. They support benchmarking and allow financiers and regulators to assess whether recovery improves environmental performance.

Recovery decision gate

Progression must pass a formal gate integrating techno-economic analysis, life-cycle assessment, geometallurgical compatibility, environmental externalities, and social-licence considerations. This ensures recovery advances only when feasibility, ESG acceptability, and viability are demonstrated.

Closure and post-closure

Closure plans must address altered physical, geochemical, and hydrological conditions resulting from reprocessing. Post-closure monitoring should extend to verified stability milestones and no-net-impact criteria, ensuring recovery does not compromise long-term facility safety.

By applying these checkpoints, mining companies can demonstrate due diligence, strengthen access to responsible financing, and integrate digital traceability from planning through closure. The Responsible Recovery framework therefore acts as a bridge between governance and innovation, enabling circular mining to scale without eroding public trust. It reinforces the principle that risk mitigation and resource recovery are two components of the same intelligent system.

This structured approach aligns with the governance, risk, and performance principles articulated across the GISTM, MAC, and LPSDP frameworks, integrating them into a unified method for evaluating and executing tailings-recovery opportunities [

7,

10,

13].

Recent technical studies demonstrate that legacy tailings facilities can contain significant quantities of recoverable critical elements. Sampling across diverse climatic zones and ore-deposit types shows that decades-old tailings may retain economically meaningful metal concentrations, making historic sites an essential component of Responsible Recovery assessments [

16].

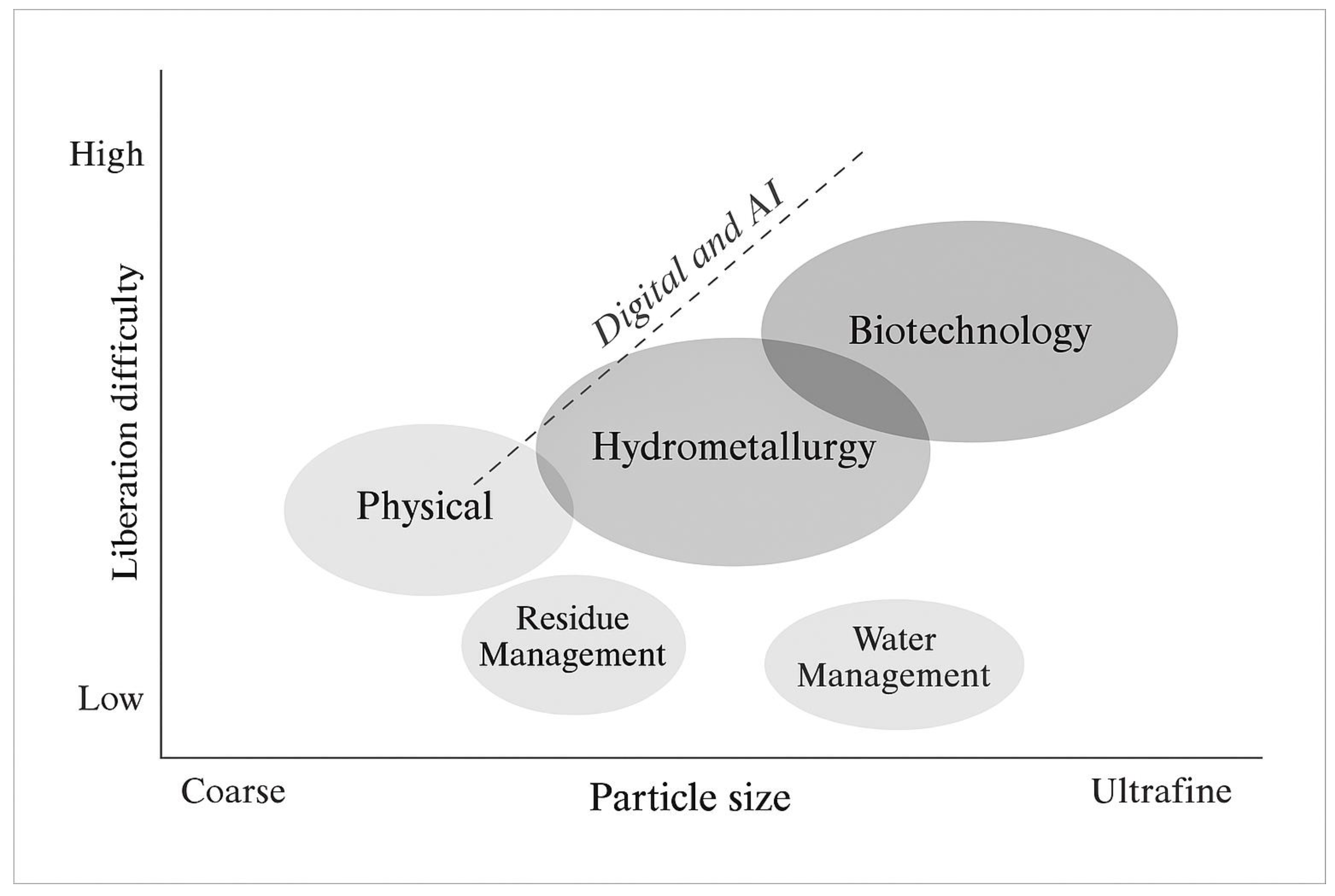

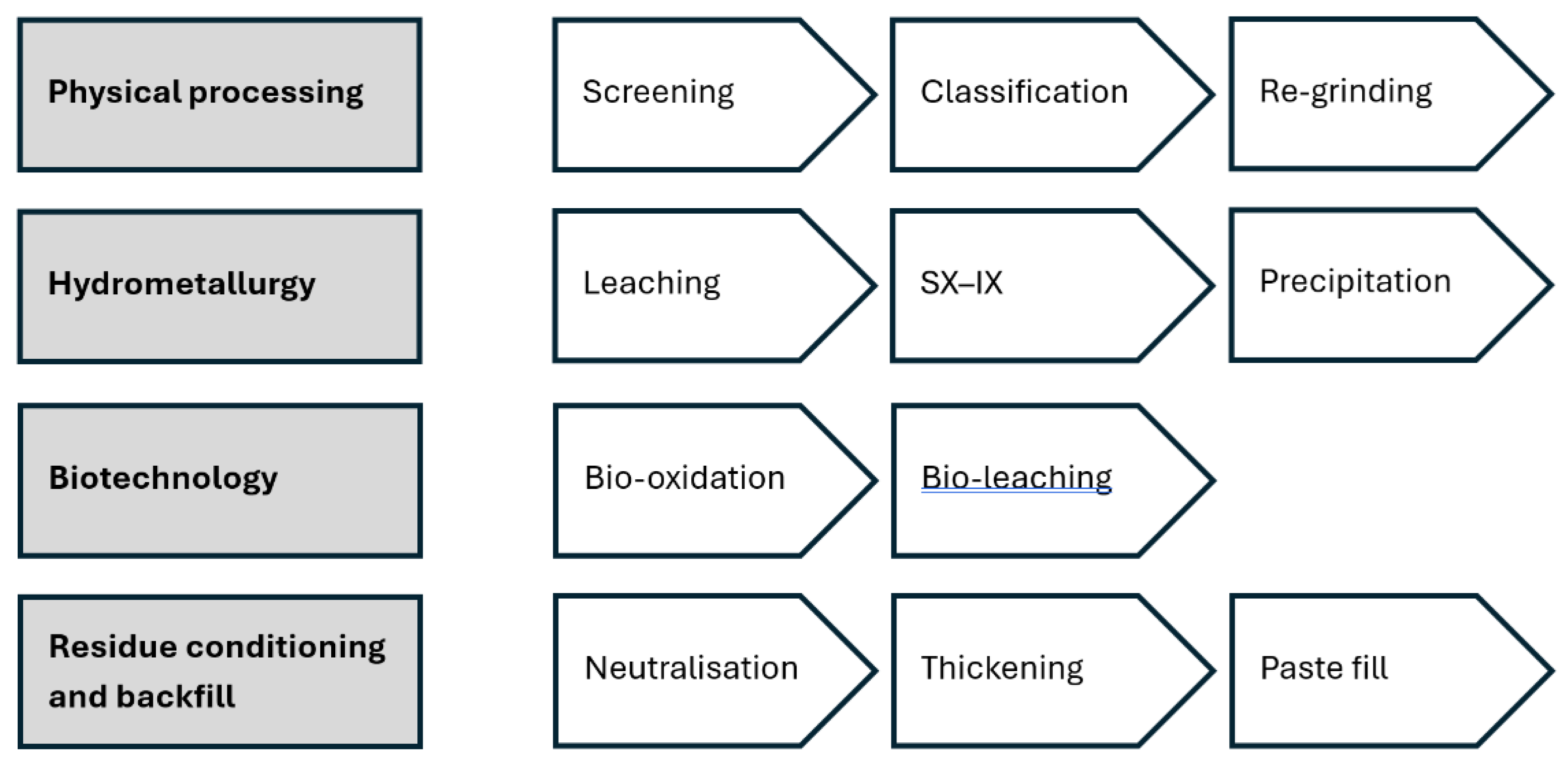

Figure 2 summarises the applicability of major tailings-reprocessing technologies.

4. Technology Pathways – From Waste to Value

Technology is the mechanism that converts responsible governance into measurable recovery. The economic potential of tailings depends on how effectively minerals can be liberated, separated, and purified without generating new liabilities. Material once regarded as fine waste is now understood as a multi-phase mixture containing sulphides, oxides, silicates, and trace critical elements, requiring both proven metallurgical routes and targeted innovations.

Historic waste piles from copper, iron, and other base-metal operations may contain economically relevant tellurium, while sulphide-rich dumps and ancient slag heaps show potential for critical elements. Modern geochemical analysis confirms that legacy tailings and waste rock can hold previously unrecognised value [

17].

Recent work on oil sand tailings shows this shift clearly. Companies are adapting acid-leaching, smelting, and proprietary separation systems to recover rare earth elements from tailings-derived solutions, demonstrating how mature hydrometallurgical routes can be extended to complex residues [

18].

Rare-earth molten-salt electrolytic slags (REMSES) have emerged as high-value secondary resources. A low-temperature sequence combining lime transformation with conditional sulphuric-acid leaching has achieved dissolution efficiencies above 95 percent for REEs and 99 percent for lithium, followed by precipitation of high-purity REO and Li₃PO₄ [

19]. This highlights the potential of integrated hydrometallurgical circuits for critical-element recovery.

At the simplest level, reprocessing may involve physical upgrading. Screening, classification, and re-grinding expose locked grains, while magnetic and gravity separation remove gangue. Even modest improvements can add metal production, reduce waste volumes, and improve facility stability.

Field evidence supports this trend. Sampling shows that decades-old tailings can retain economically meaningful metal concentrations, underscoring the need to include historic sites in Responsible Recovery assessments [

16], [

17,

20]. Early studies identified tellurium enrichment [

16], and USGS work provides confirmation, suggesting some legacy facilities may represent viable secondary resources [

20].

Hydrometallurgical pathways have advanced substantially. Compared with pyrometallurgy, they offer flexibility, lower energy demand, and reduced emissions, although often with higher water requirements and limitations for some products [

21]. Acidic or alkaline leaching, followed by solvent extraction, ion exchange, or selective precipitation, enables recovery of cobalt, nickel, vanadium, rare earths, and other elements. Intensification tools such as membrane contactors, electro-reduction, and bio-leaching improve yields while lowering reagent and energy use.

Microbial systems reinforce this trend. Bio-oxidation can break down sulphide matrices at low pressures and temperatures, reducing reagent consumption and enabling cleaner downstream recovery. Trials show that species such as A. thiooxidans can catalyse dissolution of copper, zinc, and lead minerals while decreasing cyanicidal interference [

22].

Residue conditioning and backfilling form another technological pillar. After metal extraction, remaining solids are neutralised, thickened, and stored or reused. Paste backfill allows treated tailings to be reintegrated underground, reducing surface footprints and immobilising residual metals and sulphates [

23].

A simplified comparative overview of major process pathways is presented in

Figure 3.

Water and reagent recovery are equally important. Modern circuits often employ closed-loop systems with high recovery rates, linking process efficiency to ESG performance, while neutralisation steps regenerate reagents and reduce toxicity.

Because tailings are heterogeneous, technology selection requires data-driven classification. Optical and spectral systems, including VIS–NIR mineral analysis, can sort mixed wastes into categories, enabling representative flowsheets and predicting recovery potential. Digital twins and AI-assisted modelling extend this further. By simulating leach kinetics and reagent interactions, they define operating windows before pilot testing and quantify energy use, carbon intensity, and water demand.

Technological maturity now aligns with governance maturity. Intelligent selection, modelling, and integration of these technologies convert tailings from a liability into a contributor to the circular economy – the essence of Intelligent Green Mining.

5. Intelligent Systems – Where AI Adds Value

Intelligent systems link governance data, process variables, and environmental indicators into decision frameworks aligned with GISTM [

7], the ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12], and MAC’s Tailings Guide 3.2 [

10].

The first layer is data integration and inventory mapping. Public registers released under GISTM, MAC, or corporate disclosures can be processed using natural language tools to identify facilities with signatures such as critical-metal potential, stable geotechnical conditions, and sufficient infrastructure [

7,

10]. Persistent information gaps documented in critical-materials research justify intelligent tools that harmonise fragmented datasets [

24]. Automated extraction of coordinates, ore types, and risk categories from thousands of PDF reports converts static files into a searchable recovery database.

The second layer is process optimisation and predictive modelling. Machine learning models trained on laboratory and pilot data forecast leach recovery, reagent use, or water balance where multi-parameter interactions influence performance [

25]. In hydrometallurgy, surrogate models approximate reaction kinetics, allowing engineers to explore parameter windows before testing, as recognised in studies on recycling and transformation pathways in mineral residues [

21]. These tools reduce experimental effort and accelerate flowsheet design, linking AI to sustainability metrics [

26].

A third application is real-time monitoring and anomaly detection. Streaming data from piezometers, drones, and satellite imagery can feed AI dashboards that flag deviations in water level, stability, or effluent chemistry, consistent with expectations in the ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12] and the Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program [

13]. Early-warning analytics enhance safety and provide transparent audit trails, reinforcing assurance principles in the GISTM [

7].

AI also contributes at the disclosure level. Schema-checking algorithms validate whether published data meet minimum-field requirements in the GISTM [

7] and MAC’s Tailings Guide Version 3.2 [

10]. They highlight missing entries and assign automated data-quality scores, helping companies benchmark performance and enabling lenders to quantify ESG risk, reflecting research on how regulatory frameworks influence digital reporting in mining [

27].

Emerging work extends these capabilities into large language model (LLM) architectures that learn mining terminology and reasoning patterns. LLMs can summarise conformance statements, flag governance anomalies, and support assurance teams by drafting structured audit summaries, particularly when applied to standardised formats defined in the GISTM [

7], ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12], and MAC’s Tailings Guide 3.2 [

10].

Collectively, these modules support the shift toward evidence-driven tailings management. Embedded within the Responsible Recovery framework, AI links governance and technology, ensuring decisions from site selection to closure remain transparent, data-supported, and aligned with governance systems such as the Global Tailings Review [

6] and broader sustainability objectives outlined in green development analyses [

28].

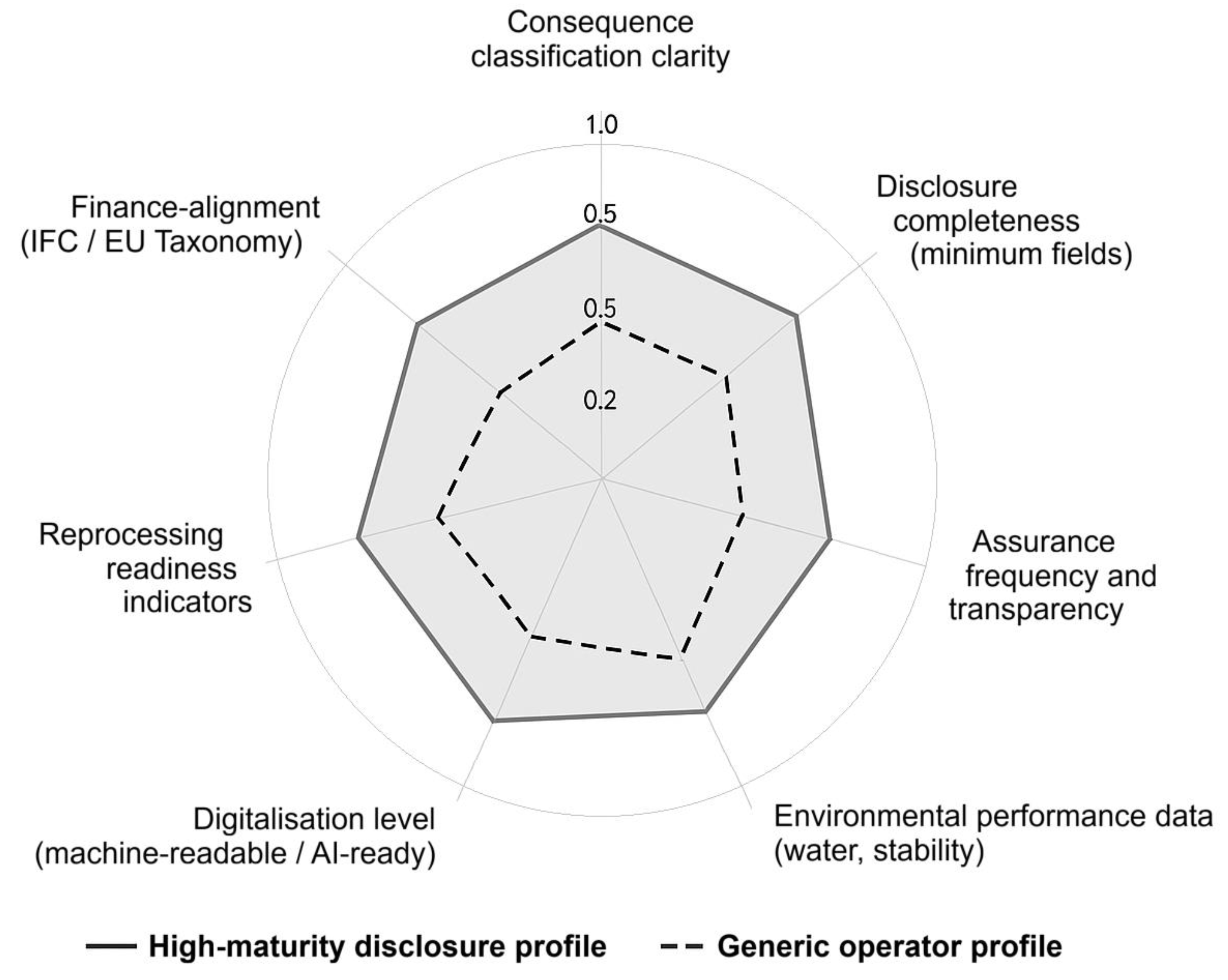

6. Comparative Disclosure – Toward a Minimum Fields List

Effective governance depends not only on what information is disclosed but also on how consistently it is presented across different facilities. Although many operators now publish tailings data under the GISTM or national frameworks, formats and terminology remain fragmented [

7]. Disclosures range from narrative PDFs to spreadsheets and map interfaces, reflecting variation noted in the ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12] and MAC’s Tailings Guide Version 3.2 [

10]. This diversity limits comparison, and to make disclosure actionable, tailings information must be standardised, structured, and machine readable.

A practical response is a minimum fields list – a concise dataset with common definitions. It should capture the technical and governance attributes that determine facility risk, recovery potential, and compliance status, aligned with terminology embedded in the GISTM [

7] and MAC’s Tailings Guide Version 3.2 [

10]. Core categories include facility identifier and location; consequence classification [

10]; assurance record; deposition and process data; environmental performance indicators; emergency readiness; and recovery or rehabilitation activity, as reflected in recent disclosure formats used by major operators [

14,

29].

Publishing these attributes in structured formats such as CSV, JSON, or XBRL enables automated benchmarking across portfolios and regions. Intelligent systems can validate completeness, identify outliers, and visualise progress. For example, an AI-based schema checker can detect missing assurance data or inconsistent classification, prompting corrective updates and reflecting the link between regulatory frameworks and digital reporting in mining [

27], as well as governance expectations in the ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12] and the GISTM [

7].

A comparative disclosure-maturity profile is shown in

Figure 4, illustrating how structured reporting enables clearer distinctions between high-maturity and generic operators across key governance dimensions.

Such harmonisation benefits all stakeholders. Companies avoid ad hoc requests; investors and lenders receive comparable ESG metrics; regulators can automate compliance screening; and researchers can model links between governance maturity, innovation, and recovery success, consistent with evidence on the role of structured data in enabling recovery pathways and policy development [

2]. Over time, aggregated disclosure may guide national strategies for reprocessing legacy tailings, turning transparency into infrastructure for circular mining. This aligns with green development objectives in regional sustainability analyses [

28] and with governance principles in the Global Tailings Review [

6].

Ultimately, the minimum fields approach transforms disclosure from a compliance obligation into a foundation for Intelligent Green Mining, where digital governance, performance data, and AI analytics make sustainability measurable and comparable across the global mining sector. This is consistent with the governance architecture in the ICMM Good Practice Guide [

12] and the green growth objectives discussed in regional analyses of mining and sustainability transitions [

28].

7. Case Snapshots – What Good Looks Like

The practical value of structured disclosure becomes clearer in industry practice. Patterns outlined in Chapter 6 show that transparency has become a functional component of tailings governance rather than an administrative formality. Chapter 7 examines how leading operators translate disclosure into operational discipline and early circular reprocessing assessment. Recent practice demonstrates that responsible tailings management and recovery are now scalable, and that GISTM-aligned disclosure has matured into a governance tool supporting portfolio risk screening, legacy-asset prioritisation, and systematic identification of sites with reprocessing potential. The following examples show how transparency, digitalisation, and structured reporting reinforce one another within the Responsible Recovery framework.

BHP offers a clear demonstration of portfolio-scale governance. Its 2025 GISTM Public Disclosure consolidates 70 tailings storage facilities across multiple regions [

29]. The register integrates conformance status, consequence classification, assurance records, and closure progression in a structured dataset. By publishing validation summaries, independent review findings, failure-mode assessments, and next-audit dates, BHP turns disclosure from a static requirement into a portfolio-management instrument that supports early identification of reprocessing candidates and clustering of similar facilities.

Anglo American provides a complementary regional model. It issues six GISTM Stage-5 reports aligned with specific business units or jurisdictions [

14]. Together they cover 27 TSFs across Brazil, Chile, Australia, Peru, Kumba Iron Ore, and De Beers. Using a unified format while preserving regional geological, hydrological, and regulatory context improves interpretability for local stakeholders and allows each region to align recovery and stewardship options with its particular mineralogy and conditions.

Two features are especially relevant for Responsible Recovery. First, both companies provide consistent, structured facility-level data, including consequence classification, raising method, water balance, assurance cycles, and independent technical reviews. These attributes align with minimum fields recommended for reprocessing readiness and enable early screening of TSFs for circular-recovery opportunities. Second, increasing transparency is becoming an enabling condition for finance. Lenders and insurers use structured GISTM data to quantify governance maturity and ESG risk, linking access to capital with disclosure quality and reducing perceived uncertainty.

Sector-wide initiatives such as the Global Tailings Management Institute (GTMI) reinforce this shift by providing guidance, case documentation, and capacity building. Their emphasis on accessibility allows good practice to be transferred beyond major producers to smaller companies and regulators. Combined with portfolio- and region-level reporting, these initiatives show how governance, technology, and transparency function as mutually reinforcing pillars of Intelligent Green Mining, enabling tailings to transition from liabilities into auditable sources of critical materials.

These implications extend directly into financing and assurance, the focus of Chapter 8. The convergence of structured disclosure, ESG data quality, and reprocessing potential is reshaping how lenders, regulators, and operators evaluate risk. Chapter 8 examines how this governance architecture translates into investment criteria and how Responsible Recovery can be integrated into emerging sustainable-finance frameworks.

8. Financing and Assurance

Financing tailings recovery remains one of the least developed dimensions of the circular mining transition. Conventional debt structures and project finance models were designed for new extraction projects with proven reserves and predictable revenues, not legacy facilities characterised by heterogeneous materials, inherited liabilities, and shifting regulatory expectations. Lenders therefore perceive elevated uncertainty and require strong evidence of governance quality and environmental transparency. International frameworks such as the IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability [

30] and the EU Taxonomy Regulation [

31] now shape investment screening criteria, reinforcing expectations that mining projects demonstrate credible ESG risk management before accessing capital. Operators pursuing reprocessing must provide structured, verifiable disclosure to align with sustainable finance norms and reduce perceived risk.

The Responsible Recovery framework addresses this financing gap by converting qualitative ESG commitments into quantifiable checkpoints that can be audited and priced into investment decisions. Each of the seven checkpoints is linked to indicators that mirror expectations in sustainable finance regulations. Frameworks such as the IFC Performance Standards [

30] and the EU Taxonomy Regulation [

31] emphasise that capital allocation should reflect demonstrable performance rather than stated intent. By linking reduced risk weightings, lower borrowing costs, or eligibility for green instruments to verified outcomes, financiers can translate responsible practice into tangible financial value.

Growth in sustainability-linked finance expands these opportunities. The EU Green Bond Standard [

32], China’s Green Industry Guidance Catalogue [

33], and verified ESG datasets such as MAC’s TSM Performance Reports [

34] recognise waste reduction and resource-efficiency initiatives as sustainable investments. Demonstrating conformance with governance standards such as the GISTM [

7], MAC’s Tailings Guide [

10], or UNECE-linked frameworks strengthens eligibility for such instruments and broadens access to compliant capital. These taxonomies establish a connection between responsible operational practice and sustainable financing.

Independent assurance reinforces this shift. External auditors verify technical outcomes and the accuracy of ESG data, increasing confidence among lenders and regulators. Over time, digital platforms may enable continuous assurance, where AI monitors facility data in near-real time and flags deviations from agreed benchmarks. This transition from periodic audits to ongoing validation would enhance disclosure credibility and support risk-based financing models.

Collectively, these mechanisms redefine how capital flows into mining. Financing becomes linked not only to ore grades or market conditions, but also to governance quality and environmental integrity. Embedding Responsible Recovery within financial architecture ensures that strong ESG performance translates into improved access to capital, supporting long-term resilience within the Intelligent Green Mining economy. As financing and assurance evolve, the broader strategic implications of tailings recovery become clearer.

Figure 5 summarises the seven governance checkpoints introduced in Chapter 2, carried through the technical and governance analysis in Chapters 3–7, and applied in Chapter 8 to financing and assurance, presenting them as a unified stepwise pathway for Responsible Recovery.

9. Conclusions and Next Steps

Mine tailings remain one of the most persistent challenges in the mining sector. They reflect extraction methods that prioritised primary commodities while discarding associated minerals, yet many deposits contain metals now essential for modern technologies, energy systems, and national resource strategies. This dual reality marks a turning point: tailings are no longer solely a liability but a potential strategic reserve that can support supply security, reduce reliance on greenfield projects, and improve resource efficiency.

However, this opportunity cannot be realised through technology alone. The past decade has shown that technical capability without strong governance creates risk rather than resilience. Effective recovery requires policy clarity, transparent disclosure, and organisational accountability alongside credible engineering and environmental practice. When governance structures, operational controls, and assurance mechanisms align, recovery becomes a controlled, auditable process rather than an experimental activity at the margins of mining.

Digital tools are accelerating this shift. The sector is moving from static reporting toward dynamic, data-driven systems that track performance across entire portfolios. Artificial intelligence, digital twins, and automated data-quality checks enable faster assessment of recovery potential, earlier identification of risks, and clearer demonstration of progress to regulators, communities, and financiers. Recovery therefore becomes part of a wider transition toward intelligent mining, where real-time information supports responsible planning and stewardship.

The Responsible Recovery framework shows how governance checkpoints, technology pathways, and digital systems can be integrated into a single verifiable chain. It provides operators with a structured method for screening sites, designing flowsheets, planning assurance activities, and communicating performance. It also offers regulators and lenders a clearer basis for evaluating whether recovery projects meet acceptable standards of safety, transparency, and environmental responsibility.

Implementation now becomes the priority. Three actions stand out: establishing open repositories of flowsheets and benchmark data for early assessment; developing a universal minimum-fields disclosure schema for consistent comparison across regions; and piloting AI-assisted tools that support site selection, parameter optimisation, and ESG verification in operating environments. Each step strengthens confidence in recovery decisions and accelerates uptake of responsible practice.

Progress will require collaboration. Shared standards, shared data, and shared evaluation methods can reduce duplication and enable smaller operators to participate. As sustainable finance frameworks increasingly link capital access with governance performance, transparency becomes not only a compliance requirement but an economic driver.

By treating tailings as data-rich material rather than static waste, the sector can align environmental responsibility with economic value. Responsible Recovery offers a pathway toward long-term safety, reduced land disturbance, and strengthened mineral supply. Intelligent Green Mining is therefore not a distant aspiration but a practical direction for the industry, capable of transforming legacy liabilities into future assets and building resilience, competitiveness, and public trust in a resource-constrained world.

References

- Sahlström, F; Arribas, A; Dirks, P; Corral, I; Chang, Z. Mineralogical distribution of germanium, gallium, and indium at the Mt Carlton high-sulfidation epithermal deposit, NE Australia, and comparison with similar deposits worldwide. Minerals 2017, 7(11), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre (JRC). PDF code: KJ1A29744ENN; Recovery of critical and other raw materials from extractive waste and landfills. Publications Office of the European Union, 2019.

- Blackwood, M; DeFilippo, C. Germanium and gallium: U.S. trade and Chinese export controls. U.S. International Trade Commission, Executive Briefings on Trade, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials (Critical Raw Materials Act). Official Journal of the European Union 2024, OJ L 202, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Expert Engineering Investigation and Review Panel. Report on Mount Polley Tailings Storage Facility Breach. Province of British Columbia, Canada. 2015. Available online: https://www.mountpolleyreviewpanel.ca/sites/default/files/report/ReportonMountPolleyTailingsStorageFacilityBreach.pdf.

- Global Tailings Review Global Tailings Review – Project Documents and Draft Standard. ICMM, UNEP, PRI. 2020. Available online: https://globaltailingsreview.org/.

- Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) Global Tailings Review: ICMM, UNEP, PRI. 2020.

- Global Tailings Review Objective. In Global Tailings Review Secretariat; 2019; p. 3.

- Global Tailings Review Consultation. In Global Tailings Review Secretariat; 2019; p. 8.

- Mining Association of Canada (MAC). Tailings Guide: A Guide to the Management of Tailings Facilities, Version 3.2.; Mining Association of Canada: Ottawa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environmental Affairs; Department of Mineral Resources; Chamber of Mines of South Africa; South African Mining and Biodiversity Forum; South African National Biodiversity Institute. Mining and biodiversity guideline: mainstreaming biodiversity into the mining sector.; Pretoria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). Tailings Management: Good Practice Guide, 2nd Edition.; ICMM: London, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government; Department of Industry; Innovation and Science. Tailings Management: Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry.; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anglo American. GISTM Stage-5 Disclosure Reports (August 2025):De Beers Group; Kumba Iron Ore Limited (KIO); Copper Peru; Steelmaking Coal (SMC), Australia; Copper Chile; Iron Ore Brazil; Anglo American plc, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Holley, E; Klinger, J M; Reilly, C; et al. U.S. Industry Practices and Attitudes Towards Reprocessing Mine Tailings for Metal Recovery. Resources Policy 2025, 86, 104150, p. 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S M; Piatak, N M; McAleer, R J. Potential for Tellurium Recovery from Legacy Mine Wastes. Goldschmidt 2024 Abstracts 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Critical Mineral Resources of the United States – Tellurium (Professional Paper 1802–R); U.S. Department of the Interior: Washington, D.C, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, K; Magdouli, S; Kaur, K; Brar, S K. Strategies for Hydrocarbon Removal and Bioleaching-Driven Metal Recovery from Oil Sand Tailings. Minerals 2024, 14, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Luo, P; Liu, Z; Tang, X; Zhang, B; Guo, J. Recovery of rare earths and lithium from rare-earth molten-salt electrolytic slag by lime transformation, co-leaching, and stepwise precipitation. Physicochemical Problems of Mineral Processing 2024, 60(2), Article 186333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S M; Piatak, N M; McAleer, R J. Potential for Tellurium Recovery from Legacy Mine Wastes. In U.S. Geological Survey, Geology, Energy and Minerals Science Center; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, F S M; Taborda Llano, I; Fantucci, H; Nunes, E B; Santos, R M. Recycling strategies of mine tailings, with environmental, safety, technical and materials considerations. 202207.0010.v1. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martell-Nevárez, M A; Medina-Torres, L; Ríos-Fránquez, F J; et al. Bio-Oxidation Process of a Polymetallic Sulfide Mineral Concentrate for Silver Recovery. Minerals 2025, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, M; Benzaazoua, M; Ouellet, S. Experimental characterization of cemented paste backfill. Minerals Engineering 2005, 18(1), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylä-Mella, J; Pongrácz, E. Drivers and constraints of critical materials recycling: the case of indium. Resources 2016, 5(4), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigiobbe, V; Jazari, O; Liguori, S; Brombin, V; Pasquali, N; Nardello, A. Recovery of critical minerals from mine tailings integrated with CO2 mineralization. EGUsphere 2025, EGU25-7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiya, M; Darade, M M; Shinde, B A; Kumbhare, M P; Taware, R D; Chougule, S M; Dixit, S M; Kurhade, A S. AI Applications in Tailings and Waste Management: Improving Safety, Recycling, and Water Utilization. Applied Chemical Engineering 2025, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M; Noailly, J. Environmental regulations in the mining sector and their effect on technological innovation. In Global challenges for innovation in mining industries; Daly, A, Humphreys, D, Raffo, J, Valacchi, G, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Mining and green growth in the EECCA region. In OECD Green Growth Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BHP. GISTM Conformance Statement and Public Disclosure 2025; BHP Group Limited, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. IFC, World Bank Group. 2012. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/ifc-performance-standards.pdf.

- European Parliament and the Council. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment. Official Journal of the European Union 2020, L 198/13. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council. Regulation (EU) 2023/2631 on European Green Bonds and optional disclosures. Official Journal of the European Union, L 2023/2631. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202302631.

- NDRC; MIIT; MNR; MEE; MOHURD; PBoC; NEA. 绿色产业指导目录 (2019年版 [Green Industry Guidance Catalogue (2019 Edition)]. NDRC Circular No. 293. Official PDF. 2019. Available online: https://fgw.beijing.gov.cn/gzdt/tztg//202109/P020210909659122770907.pdf.

- Mining Association of Canada (MAC). Performance reports and awards – Towards Sustainable Mining. 2025. Available online: https://mining.ca/towards-sustainable-mining/tsm-progress-report.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).