Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. OECTs Preparation

2.3. Adsorption on Polymeric Films

2.4. SPR

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

2.6. Data Curation

3. Results and Discussion

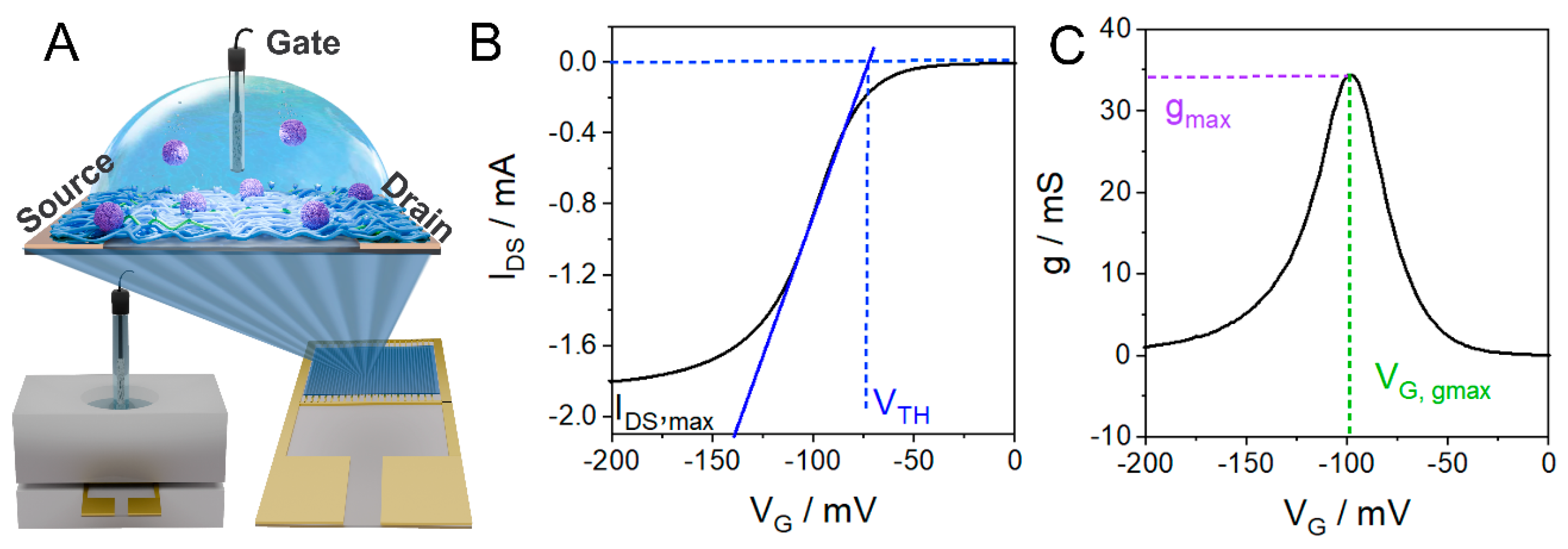

3.1. OECT Characteristic Parameters Determination

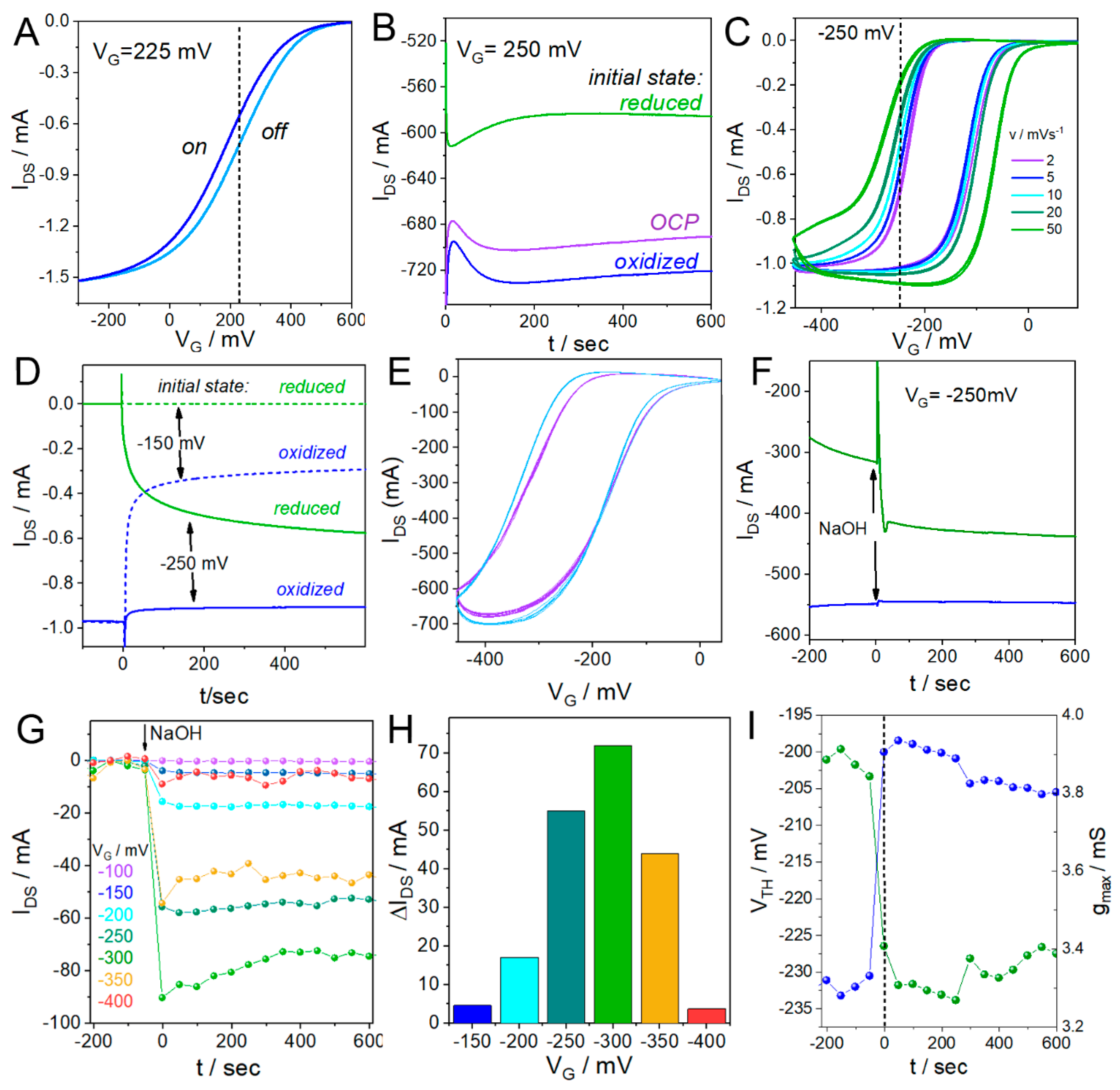

3.2. Limitations of Traditional OECT Measurements and Introduction to Continuous Cycling Methodology (CCM)

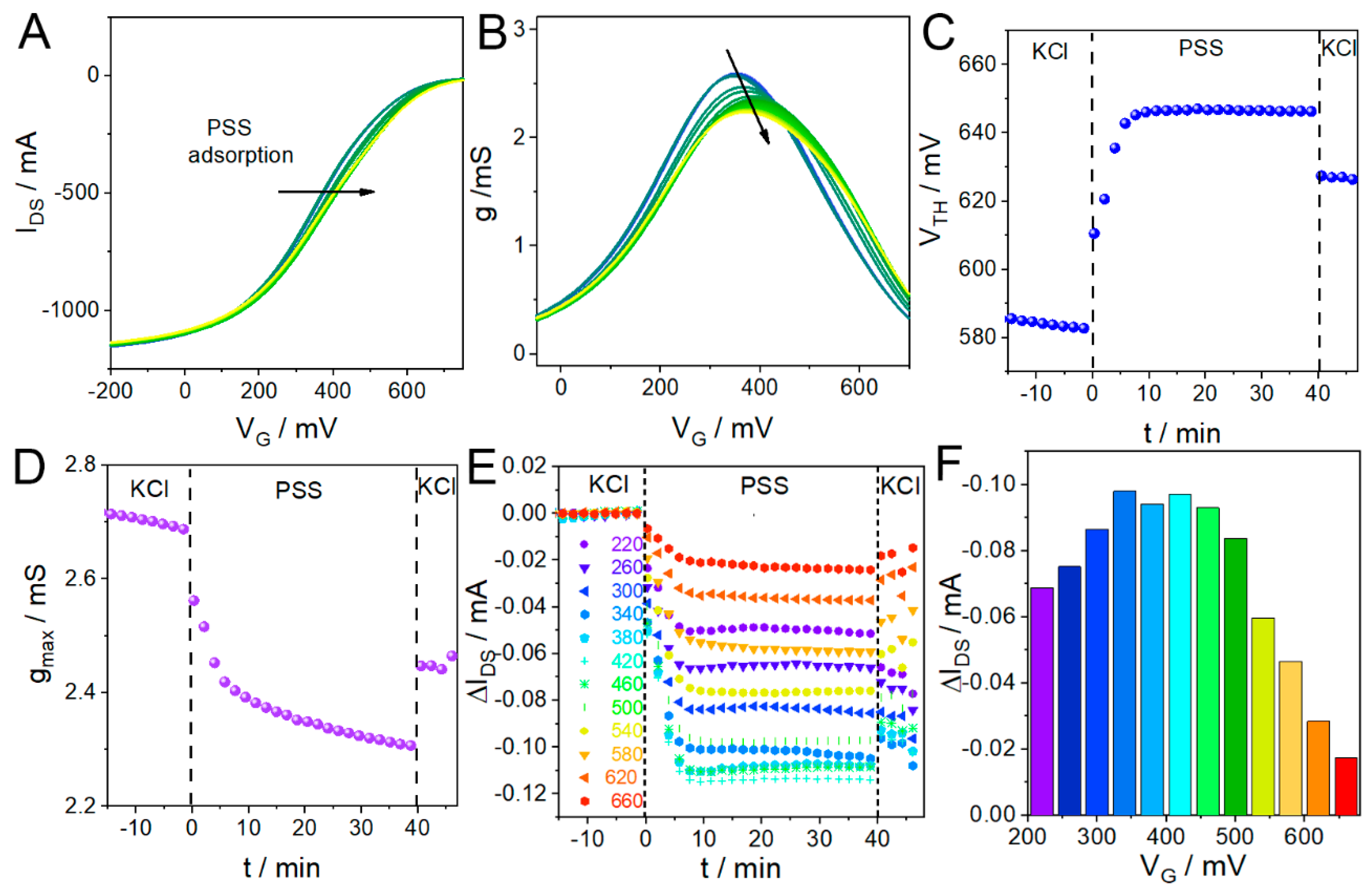

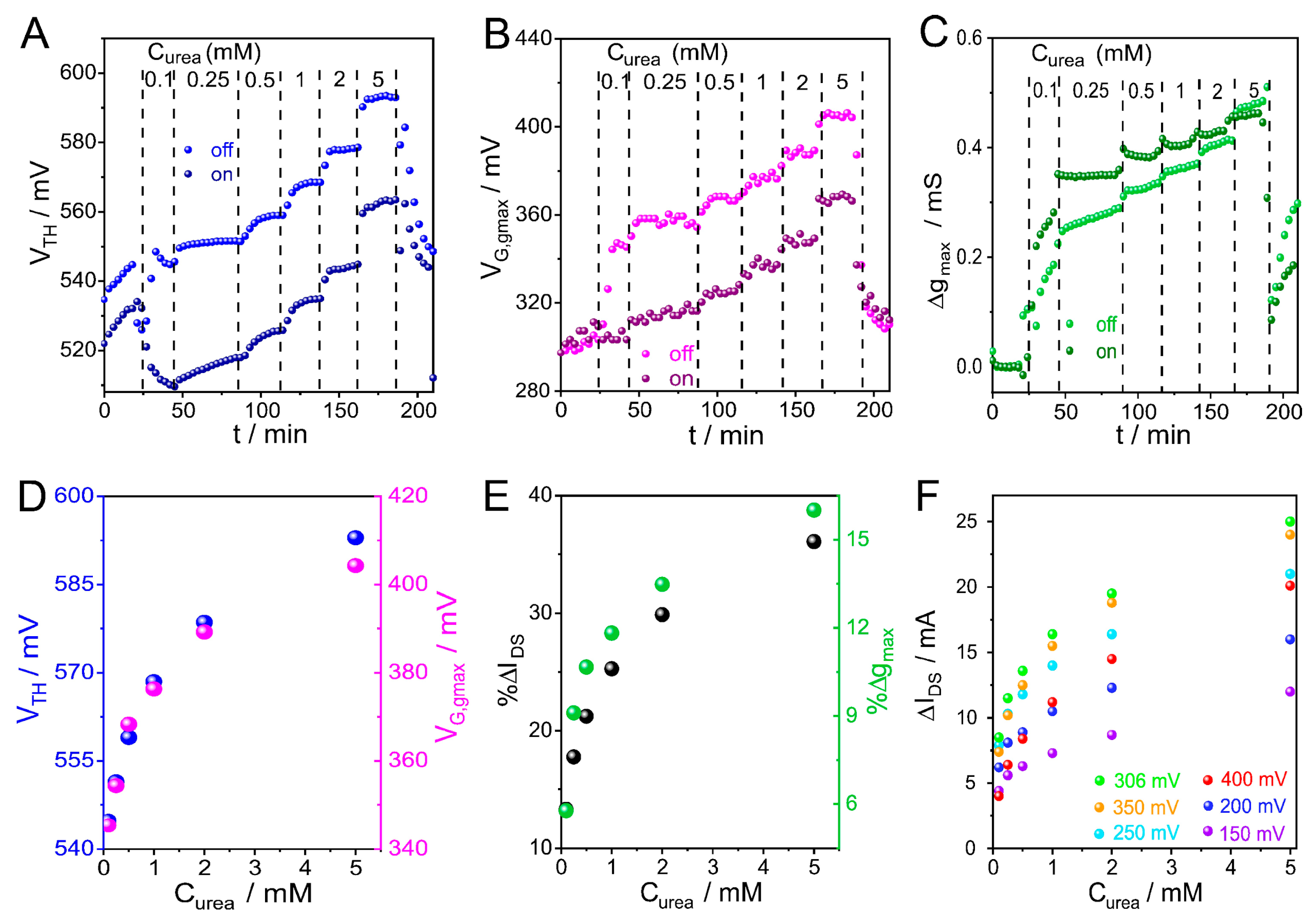

3.3. CCM Applied to Polyelectrolyte Adsorption Monitoring with OECTs

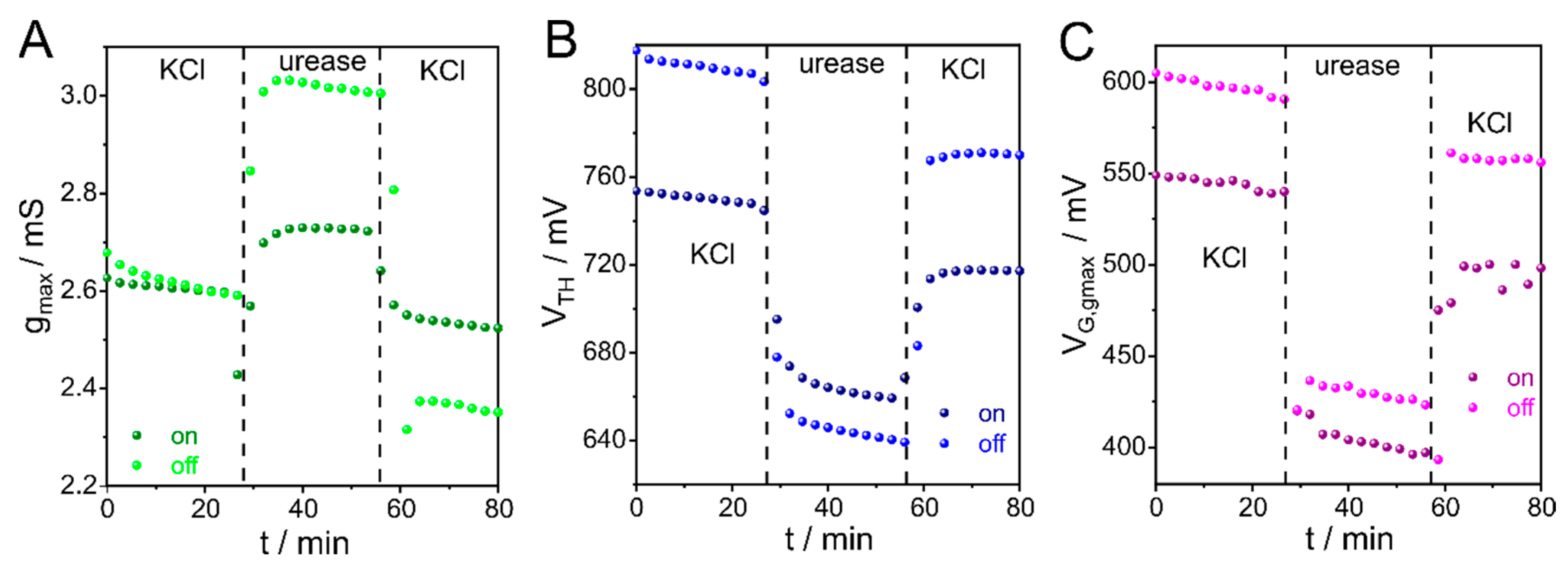

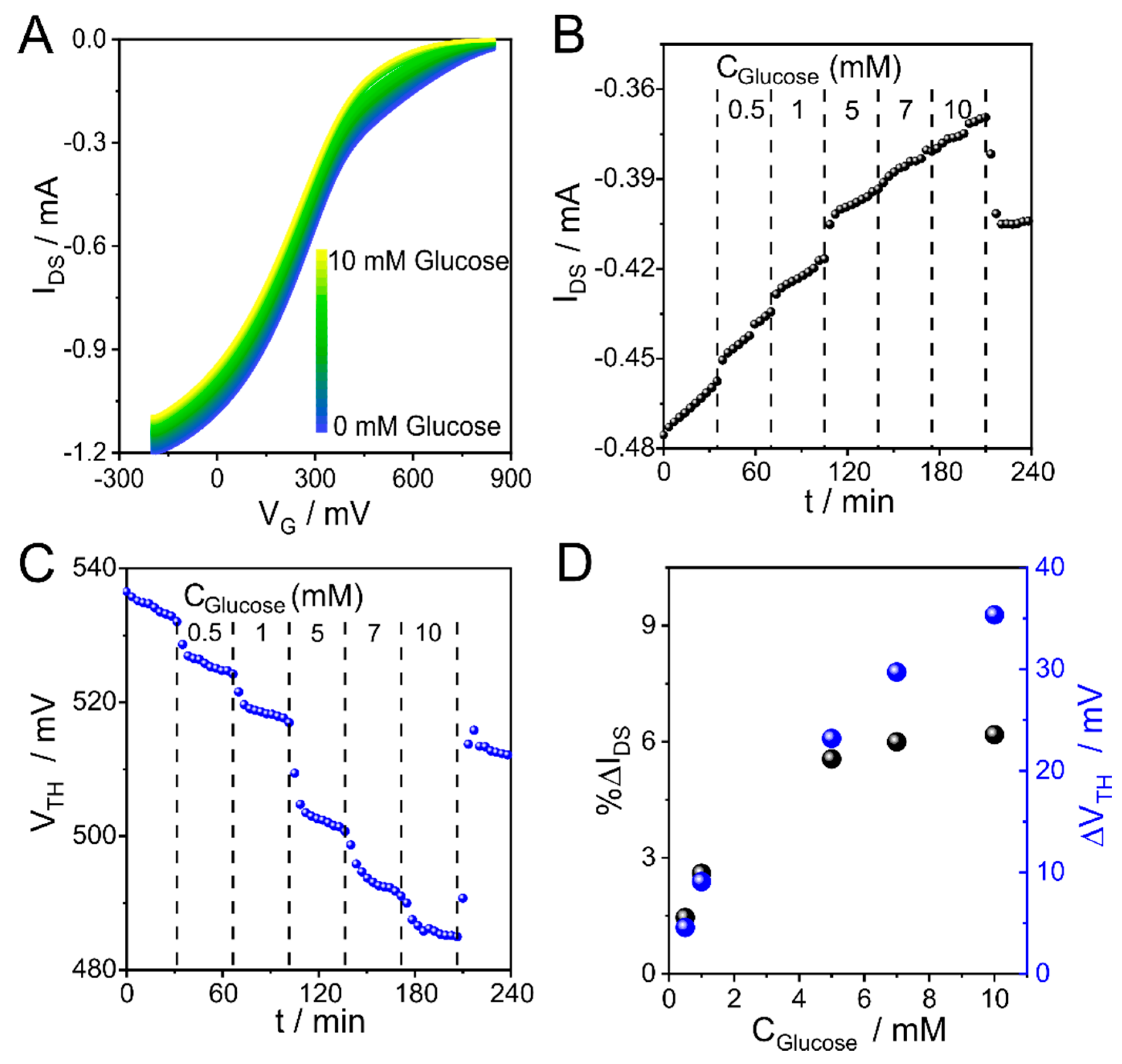

3.4. CCM Applied to Enzyme Adsorption Monitoring with OECTs

3.5. CCM Applied to the Biosensing of Catalytic Reaction with OECTs

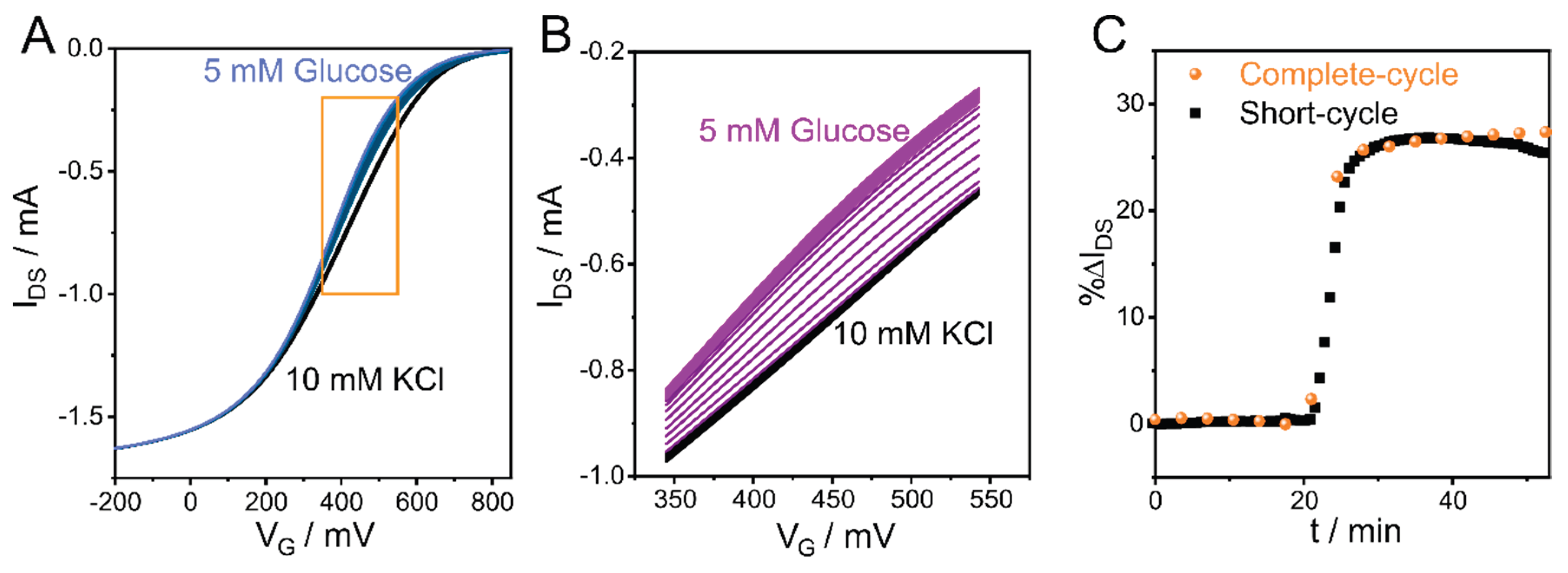

3.6. Sensing Rapid Processes with CCM

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, R.; Gupta, R.; Bansal, D.; Bhateria, R.; Sharma, M. A Review on Recent Trends and Future Developments in Electrochemical Sensing. ACS Omega 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, J.; Barse, B.; Gatto, G.; Broncova, G.; Kumar, A. Electrochemical Sensors and Their Applications: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Halsall, H.B.; Heineman, W.R. Electrochemical biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1747–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, A.; Ahmed, A.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Furukawa, H.; Arya, S.; Khosla, A. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Biosensors: Applications, Challenges, and Future Scope. Biosensors 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Du, D.; Lin, Y. Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors Based on Nanomaterials and Nanostructures. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Capitán, M.; Baldi, A.; Fernández-Sánchez, C. Electrochemical Paper-Based Biosensor Devices for Rapid Detection of Biomarkers. Sensors 2020, 20, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviana, E.; McCord, C.P.; Clark, K.M.; Jang, I.; Henry, C.S. Electrochemical paper-based devices: sensing approaches and progress toward practical applications. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivnay, J.; Inal, S.; Salleo, A.; Owens, R.M.; Berggren, M.; Malliaras, G.G. Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 17086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeglio, E.; Inganäs, O. Active Materials for Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, D.; Druet, V.; Inal, S. A guide for the characterization of organic electrochemical transistors and channel materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Knoll, W.; Azzaroni, O. Highly sensitive urine glucose detection with graphene field-effect transistors functionalized with electropolymerized nanofilms. Sensors & Diagnostics 2022, 1, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, E.; Fenoy, G.E.; Cantillo, A.L.; Allegretto, J.A.; Scotto, J.; Piccinini, J.M.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Biofunctionalization of Graphene-Based FET Sensors through Heterobifunctional Nanoscaffolds: Technology Validation toward Rapid COVID-19 Diagnostics and Monitoring. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, C.-A.; Chen, W.-Y. Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Biomedical Applications: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Sensors 2019, 19, 4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, F. Organic electrochemical transistor in wearable bioelectronics: Profiles, applications, and integration. Wearable Electron. 2024, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, E.; Allegretto, J.A.; Scotto, J.; Cantillo, A.L.; Fenoy, G.E.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Surface Engineering of Graphene through Heterobifunctional Supramolecular-Covalent Scaffolds for Rapid COVID-19 Biomarker Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 43696–43707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graphene Field-Effect Transistors: Advanced Bioelectronic Devices for Sensing Applications; Azzaroni, O., Knoll, W., Eds.; VCH-Wiley: Weinheim, 2023; ISBN 3527349901. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T.; Okuda, S.; Ushiba, S.; Kanai, Y.; Matsumoto, K. Challenges for Field-Effect-Transistor-Based Graphene Biosensors. Materials (Basel) 2024, 17, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Peng, C.; Shi, W.; Hu, S.; Cao, Y.; Wei, H.; Chen, P.; Xia, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. An Interlayer Strategy for Low-Voltage Thin-Film Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Small Methods 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, H. Expanding the potential of biosensors: a review on organic field effect transistor (OFET) and organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) biosensors. Mater. Futur. 2023, 2, 042401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliani, M.; Diacci, C.; Berto, M.; Sensi, M.; Beni, V.; Berggren, M.; Borsari, M.; Simon, D.T.; Biscarini, F.; Bortolotti, C.A. Flexible Printed Organic Electrochemical Transistors for the Detection of Uric Acid in Artificial Wound Exudate. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decataldo, F.; Grumiro, L.; Marino, M.M.; Faccin, F.; Giovannini, C.; Brandolini, M.; Dirani, G.; Taddei, F.; Lelli, D.; Tessarolo, M. Fast and real-time electrical transistor assay for quantifying SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, A.M.; Ohayon, D.; Giovannitti, A.; Maria, I.P.; Savva, A.; Uguz, I.; Rivnay, J.; McCulloch, I.; Owens, R.M.; Inal, S. Direct metabolite detection with an n-type accumulation mode organic electrochemical transistor. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat0911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, N.; Woods, E.R.; Peppler, M.; Seal, S. Highly selective aptamer based organic electrochemical biosensor with pico-level detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 117, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, A.; Araki, T.; Nishimura, K.; Akiyama, M.; Uemura, T.; Kiriyama, K.; Koot, J.M.; Kasai, Y.; Kurihira, N.; Osaki, S. Fully Transparent, Ultrathin Flexible Organic Electrochemical Transistors with Additive Integration for Bioelectronic Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2204746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, D.; Ji, X.; Feng, L.-W.; Moore, D.; Glavin, N.R.; Xie, M.; Chen, Y.; et al. Vertical organic electrochemical transistors for complementary circuits. Nature 2023, 613, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; von Bilderling, C.; Knoll, W.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. PEDOT:Tosylate-Polyamine-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors for High-Performance Bioelectronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Hasler, R.; Quartinello, F.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Lorenz, C.; Azzaroni, O.; Bäuerle, P.; Knoll, W. “Clickable” Organic Electrochemical Transistors. JACS Au 2022, 2, 2778–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, A.; Griggs, S.; Gasparini, N.; Moser, M. Organic Electrochemical Transistors: An Emerging Technology for Biosensing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, A.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, F. Functionalized Organic Thin Film Transistors for Biosensing. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklu, A.; Ohayon, D.; Wustoni, S.; Druet, V.; Saleh, A.; Inal, S. Organic Bioelectronic Devices for Metabolite Sensing. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 4581–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Yan, F. Organic Thin-Film Transistors for Chemical and Biological Sensing. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernards, D.A.; Malliaras, G.G. Steady-State and Transient Behavior of Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 3538–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukhta, N.A.; Marks, A.; Luscombe, C.K. Molecular Design Strategies toward Improvement of Charge Injection and Ionic Conduction in Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors for Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 4325–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, B.D.; Tybrandt, K.; Stavrinidou, E.; Rivnay, J. Organic mixed ionic–electronic conductors. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, S.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, H.; Huang, W. Functional gate modification for OECT-based sensors. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 48, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Forero Pico, A.A.; Gupta, M. A functionalization study of aerosol jet printed organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) for glucose detection. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 7445–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, P.; Yan, F. Flexible Organic Transistors for Biosensing: Devices and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, K.; Xiao, K.; Xu, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, D.; Bai, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Biomolecule sensors based on organic electrochemical transistors. npj Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Ma, W. Transient Response and Ionic Dynamics in Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Mak, C.; Zhang, M.; Chan, H.L.W.; Yan, F. Flexible Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Highly Selective Enzyme Biosensors and Used for Saliva Testing. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, A.; Law, H.K.; Li, L.; Yan, F. Highly Sensitive Detection of Protein Biomarkers with Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Geng, Z.; Tang, K.; Erdem, A.; Zhu, B. Ready-to-Use OECT Biosensor toward Rapid and Real-Time Protein Detection in Complex Biological Environments. ACS Sensors 2025, 10, 3369–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currano, L.J.; Sage, F.C.; Hagedon, M.; Hamilton, L.; Patrone, J.; Gerasopoulos, K. Wearable Sensor System for Detection of Lactate in Sweat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braendlein, M.; Pappa, A.; Ferro, M.; Lopresti, A.; Acquaviva, C.; Mamessier, E.; Malliaras, G.G.; Owens, R.M. Lactate Detection in Tumor Cell Cultures Using Organic Transistor Circuits. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kukhta, N.A.; Marks, A.; Luscombe, C.K. The effect of side chain engineering on conjugated polymers in organic electrochemical transistors for bioelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 2314–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Jimenez, M.; Lugli-Arroyo, J.; Fenoy, G.E.; Piccinini, E.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Transduction of Amine–Phosphate Supramolecular Interactions and Biosensing of Acetylcholine through PEDOT-Polyamine Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Scotto, J.; Allegretto, J.A.; Piccinini, E.; Cantillo, A.L.; Knoll, W.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. Layer-by-Layer Assembly Monitored by PEDOT-Polyamine-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 5953–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Hasler, R.; Lorenz, C.; Movilli, J.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O.; Huskens, J.; Bäuerle, P.; Knoll, W. Interface Engineering of “Clickable” Organic Electrochemical Transistors toward Biosensing Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 10885–10896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Song, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Tian, Z.; Yan, F. Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Biomarker Detections. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodagholy, D.; Rivnay, J.; Sessolo, M.; Gurfinkel, M.; Leleux, P.; Jimison, L.H.; Stavrinidou, E.; Herve, T.; Sanaur, S.; Owens, R.M.; et al. High transconductance organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yue, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, L.; Ren, G.; Lu, G.; Yu, H.-D.; Huang, W. Flexible organic electrochemical transistors for chemical and biological sensing. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 2433–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, B.; Mattana, G.; Zrig, S.; Anquetin, G.; Battaglini, N.; Capitao, D.; Maurin, A.; Reisberg, S. Fabrication and Use of Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Sensing of Metabolites in Aqueous Media. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qing, X.; Zhong, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Liu, K.; Wang, D. Ion sensors based on novel fiber organic electrochemical transistors for lead ion detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 5779–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.T.M.; Keene, S.; Giovannitti, A.; Melianas, A.; Moser, M.; McCulloch, I.; Salleo, A. Operation mechanism of organic electrochemical transistors as redox chemical transducers. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 12148–12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.A.; Wu, R.; Meli, D.; Tropp, J.; Moser, M.; McCulloch, I.; Paulsen, B.D.; Rivnay, J. Sources and Mechanism of Degradation in p-Type Thiophene-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ding, P.; Ruoko, T.; Wu, R.; Stoeckel, M.; Massetti, M.; Liu, T.; Vagin, M.; Meli, D.; Kroon, R.; et al. Toward Stable p-Type Thiophene-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, J.; Lei, D.; Chen, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Y. Recent Progress in Organic Electrochemical Transistor-Structured Biosensors. Biosensors 2024, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, S.T.; Fogarty, D.; Cooke, R.; Casadevall, C.D.; Salleo, A.; Parlak, O. Wearable Organic Electrochemical Transistor Patch for Multiplexed Sensing of Calcium and Ammonium Ions from Human Perspiration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandi, I.; Marzocchi, M.; Scavetta, E.; Calienni, M.; Bonfiglio, a.; Fraboni, B. A simple all-PEDOT:PSS electrochemical transistor for ascorbic acid sensing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 6753–6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qing, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. The woven fiber organic electrochemical transistors based on polypyrrole nanowires/reduced graphene oxide composites for glucose sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 95, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Wu, D.; Tang, W.; Xi, X.; Su, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, R. Carbonized silk fabric-based flexible organic electrochemical transistors for highly sensitive and selective dopamine detection. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majak, D.; Fan, J.; Kang, S.; Gupta, M. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ 9 -THC) sensing using an aerosol jet printed organic electrochemical transistor (OECT). J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 2107–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, C.; Qu, H.; Chen, W.; Ma, A.; Zheng, L. Highly sensitive real-time detection of tyrosine based on organic electrochemical transistors with poly-(diallyldimethylammonium chloride), gold nanoparticles and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 799, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yan, F.; Lin, P.; Xu, J.; Chan, H.L.W. Highly Sensitive Glucose Biosensors Based on Organic Electrochemical Transistors Using Platinum Gate Electrodes Modified with Enzyme and Nanomaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 2264–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; von Bilderling, C.; Knoll, W.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. PEDOT:Tosylate-Polyamine-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors for High-Performance Bioelectronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Jimenez, M.; Neyra Recky, J.R.; von Bilderling, C.; Scotto, J.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. PEDOT: Tosylate-polyamine-based enzymatic organic electrochemical transistors for high-performance glucose biosensing in human urine samples. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2025, 978, 118867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyra Recky, J.R.; Montero-Jimenez, M.; Scotto, J.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. Urea Biosensing through Integration of Urease to the PEDOT-Polyamine Conducting Channels of Organic Electrochemical Transistors: pH-Change-Based Mechanism and Urine Sensing. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappia, L.D.; Piccinini, E.; von Binderling, C.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.; Azzaroni, O. PEDOT-polyamine composite films for bioelectrochemical platforms - flexible and easy to derivatize. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wustoni, S.; Surgailis, J.; Zhong, Y.; Koklu, A.; Inal, S. Designing organic mixed conductors for electrochemical transistor applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ratcliff, E.L. Tuning Organic Electrochemical Transistor (OECT) Transconductance toward Zero Gate Voltage in the Faradaic Mode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 50176–50186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Jimenez, M.; Amante, F.L.; Fenoy, G.E.; Scotto, J.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisolle, W.A. PEDOT-Polyamine-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Monitoring Protein Binding. Biosensors 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C. From Enzymatic Dopamine Biosensors to OECT Biosensors of Dopamine. Biosensors 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandi, I.; Tessarolo, M.; Mariani, F.; Arcangeli, D.; Possanzini, L.; Tonelli, D.; Fraboni, B.; Scavetta, E. Layered Double Hydroxide-Modified Organic Electrochemical Transistor for Glucose and Lactate Biosensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Turner, C.; Case, L.; Mehrehjedy, A.; He, X.; Miao, W.; Guo, S. Organic Electrochemical Transistor with Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Modified Gate for the Real-Time Selective Detection of Dopamine. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 2337–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Azzaroni, O.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A. Functionalization Strategies of PEDOT and PEDOT:PSS Films for Organic Bioelectronics Applications. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaie, N.; Daneshpour, M.; Azimzadeh, M.; Mahshid, S.; Khoshfetrat, S.M.; Jahanpeyma, F.; Gholaminejad, A.; Omidfar, K.; Foruzandeh, M. Electrochemical sensors and biosensors based on the use of polyaniline and its nanocomposites: a review on recent advances. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demuru, S.; Kunnel, B.P.; Briand, D. Thin film organic electrochemical transistors based on hybrid PANI/PEDOT:PSS active layers for enhanced pH sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2021, 7, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Noureen, B.; Du, L.; Wu, C. Functional Organic Electrochemical Transistor-Based Biosensors for Biomedical Applications. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Yu, J.; Tian, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Zang, L. Application of pedot:Pss and its composites in electrochemical and electronic chemosensors. Chemosensors 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, R.; Michinobu, T. PEDOT:PSS versus Polyaniline: A Comparative Study of Conducting Polymers for Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasch, G.; Scheinert, S.; Herasimovich, A.; Hörselmann, I.; Lindner, T. Characteristics and mechanisms of hysteresis in polymer field-effect transistors. Phys. status solidi 2008, 205, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotto, J.; Florit, M.I.; Posadas, D. pH dependence of the voltammetric response of Polyaniline. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 785, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).