1. Introduction

The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT), initially developed as a speech therapy program for individuals such as Lee Silverman, a Parkinson's Disease (PD) patient with speech difficulties [

1], has evolved into LSVT LOUD. LSVT LOUD focuses on enhancing vocal loudness and addressing hypophonia, improving communication and participation [

2]. The concept of emphasizing high-amplitude movements has also given rise to LSVT BIG, which targets not only mouth and tongue muscles but also limb and torso muscles [

3].

LSVT BIG prioritizes movement amplitude over speed and is designed as an intensive program to alleviate bradykinesia and hypokinesia in PD [

4]. It involves daily, high-intensity, standardized whole-body movements emphasizing increasing complexity through multiple repetitions [

5]. Typically, it consists of face-to-face hourly sessions, four days per week, over four weeks (totaling 16 sessions), complemented by independent everyday home practice and daily carryover exercises [

4]. The primary goal is to enhance movement amplitude, promoting healthy, quality movements without discomfort or biomechanical issues [

3]. As a high-intensity program, all exercises are performed at approximately 80% of the patient’s maximal effort [

3]. Tasks are personalized based on patient goals and evolve in duration, amplitude, and complexity [

4,

5]. External cues, including tactile and visual feedback from physiotherapists, are critical components of LSVT BIG, helping PD patients recalibrate their motor and perceptual systems to execute larger movements [

6]. Sensory self-perception deficits in PD contribute to bradykinesia, and intensive, high-effort repetition in LSVT BIG encourages adoption of a new “bigger” motor output within normal limits [

4,

7,

8].

Studies have demonstrated LSVT BIG's effectiveness in increasing movement amplitude and improving coordination through functional activities in PD patients [

4,

5]. Improvements have been reported in gait parameters, including joint range of motion, stride length, functional gait, step length, and balance [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. LSVT BIG appears more effective than traditional exercises for mild PD [

3,

14,

15] and the Korean Society for Neurorehabilitation (KSNR) recommends it for balance and gait improvement [

16]. A key advantage of LSVT is its amplitude-specific training, which, combined with intensive practice and sensory recalibration, promotes neuroplasticity and enhances daily functioning [

5,

6,

11].

Given LSVT BIG's effectiveness in PD, there is growing interest in exploring its potential benefits for other central nervous system (CNS) disorders affecting mobility and coordination, such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS). MS, is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease affecting over one million individuals worldwide [

17,

18]. It leads to muscle weakness, spasticity, and fatigue, impacting balance and gait [

19,

20]. Individuals with MS exhibit reduced stride length, cadence, joint mobility, and increased energy expenditure during walking [

21]. Cognitive-motor dual-task performance further impairs walking speed[

22], highlighting the need for effective rehabilitation.

Although various rehabilitation programs exist for MS —including resistance training, aerobic exercises, Pilates, yoga, and Tai-Chi [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]— few provide a structured, hierarchical approach with standardized high-intensity exercises applicable to daily activities and they require further refinement for home-based use [

32]. Programs grounded in motor learning principles, that incorporate sensory cues and neuroplasticity, could provide substantial benefit for MS rehabilitation.

While LSVT LOUD has been applied successfully to address hypophonia in MS [

33], LSVT BIG has not been extensively explored. Notably, it has shown efficacy in improving upper extremity motor function in stroke patients [

34,

35,

36] but, to our knowledge, no data are available regarding its effects in individuals with MS. This study aims to investigate the potential benefits of LSVT-BIG's for improving balance and gait in MS patients, comparing its efficacy with that observed in PD patients, in light of the limited research on LSVT BIG in MS. It is hypothesized that LSVT BIG will produce improvements in balance and gait in MS, comparable to those seen in PD, thereby demonstrating its feasibility for this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This pilot clinical trial employed a before-between-after intervention assessment design to investigate the impact of the LSVT BIG rehabilitation program (within-subjects effects) on selected outcome measures. Both Parkinson's Disease (PD) and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patient groups participated in the same LSVT BIG program, enabling comparisons between the groups (between-subjects effects). All assessments were conducted by the same evaluator across both groups and all time points.

2.2. Participants

A convenience sample of individuals with PD and MS was recruited. Eligibility criteria required a diagnosis of PD or MS and ambulatory status with mild to moderate disease severity (Hoehn & Yahr stages I–III for PD, and a mini-BESTest score >21 for both MS and PD participants), ensuring safe participation in the exercise program without elevated fall risk.

Exclusion Criteria Included

Atypical disease characteristics

Previous participation in LSVT BIG

Use of a duodopa pump or Deep Brain Stimulation

Cognitive impairment or dementia affecting comprehension or ability to follow program instructions (Mini-Mental State Examination score ≤24) [

37]

Cardiovascular conditions limiting engagement in high-amplitude exercise

Participants were encouraged to maintain their usual daily activities throughout the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece (now named University of Patras) (Reg. No. 981/14-01-2019), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.3. Measurement Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was functional balance, while secondary outcomes included functional gait and timed mobility performance (Timed Up and Go test [TUG], one-leg standing time, and balance on foam and inclined surfaces). All assessments were performed at baseline, mid-intervention, and post-intervention.

2.3.1. Balance Assessments

Balance performance was evaluated using the mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (mini-BESTest), which includes 14 static and dynamic tasks assessing anticipatory postural adjustments, reactive postural control, sensory orientation, and dynamic gait. The maximum score is 28 points [

38]. The Greek-adapted version of the scale, which is validated for neurological patients, was used in the study [

39].

One-Leg Stance: Participants were instructed to stand on one leg (both sides tested) for up to 30 seconds. This task assessed balance in a narrow base of support and it has been suggested as an optimal assessment of postural stability in patients with PD [

40].

Standing on a Foam Surface: Participants stood with eyes closed on a 4-inch-thick foam surface, feet together, and hands on hips for a maximum of 30 seconds. This item was derived from the mini-BESTest, to evaluate the influence of sensory input (vision and somatosensation) on balance performance, particularly under unstable conditions [

38,

39].

Standing on an Inclined Surface: Balance performance was also assessed on an incline ramp, with participants standing eyes closed, feet shoulder-width apart, and arms relaxed at their sides for up to 30 seconds. This task, derived from the mini-BESTest, provided a timed measure of balance adaptations under challenging sensory conditions [

38,

39].

2.3.2. Gait Assessments

Functional gait was assessed using the Functional Gait Assessment (FGA), which includes 10 gait tasks performed under varying conditions. Each item was scored from 0 to 3, with a total maximum score of 30 [

41]. A validated Greek-adapted version of the scale was used [

42].

General mobility and dynamic balance were assessed with the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, which measures the time required to stand up from a chair, walk three meters, turn, return to the chair, and sit down [

43]. A typical completion time is approximately 7 seconds, while times above 13 seconds indicate an increased fall risk [

43,

44].

2.4. Equipment Required

The following equipment was used for the balance and gait assessments: a stopwatch for timing, floor tape for marking distances, a 6-meter walking path (width: 30.48 cm), an obstacle (stacked boxes, 22.86 cm height), a medium-density foam surface (4 inches thick), a stable chair without armrests or wheels, an inclined ramp, and floor markings for the 3-meter TUG test distance [

38,

41].

2.5. Assessors

Data collection and evaluation were conducted by two licensed physiotherapists. The primary assessor, a specialist in neurological rehabilitation, supervised the study. The secondary assessor, certified in the LSVT BIG method, delivered the intervention and was trained by the primary assessor. Both assessors remained consistent throughout all assessments. Training for the evaluation scales was provided using official mini-BESTest manuals and instructional materials from the official website (

https://www.bestest.us/training/).

2.6. Intervention

The intervention followed the standardized LSVT BIG protocol [

4], administered by a certified physiotherapist. The program lasted four weeks, consisting of four one-hour sessions per week (16 sessions total), conducted one-on-one at the participant’s home. Additional, daily homework and carryover exercises were given to participants.

The LSVT BIG program emphasized high-effort repetitions and large amplitude movements, guided by the physiotherapist's BIG cues. The program comprised six components:

Maximal Daily Exercises: Seven multidirectional, high-amplitude full-body exercises performed repetitively, with two in a seated position and five standing.

Functional Component Tasks: Five functional activities, including a standard sit-to-stand task and four individualized exercises tailored to each patient’s daily life and goals, based on clinical evaluation.

Hierarchy Tasks: One to three complex, multilevel tasks progressively increased in difficulty over the four-week program, customized to each patient’s real-life goals and interests.

BIG Walking: Gait training emphasizing increased step length, arm swing, posture, and walking speed.

Carryover Assignment: Activities assigned to patients to integrate BIG movements into real-world conditions.

Homework: Daily independent practice of “Maximal Daily Exercises,” “Functional Component Tasks,” and “Hierarchy Tasks” outside supervised sessions.

Components 5–7 were specifically designed to promote transfer of skills outside the rehabilitation setting. Patients were instructed to match the intensity and effort of supervised sessions during daily carryover and homework exercises. Home practice was structured, with exercise diaries provided for recording adherence. Brochures illustrated exercises from the “Maximal Daily Exercises” and “Functional Component Tasks” categories.

Exercise progression was individualized, incorporating increased repetitions, added complexity (e.g., dual-tasking), variable speed, reduced base of support, and directional changes, while maintaining movement amplitude and quality [

14,

15]. These strategies aimed to engage neuroplasticity and reinforce the recognition and execution of large, controlled movements in functional tasks [

45].

2.7. Experimental Procedure

Participants’ balance and gait were assessed at baseline, at the end of the second week, and after the fourth week of the LSVT-BIG protocol. Initial interviews and eligibility screenings were conducted prior to baseline assessment. The intervention began at the subsequent appointment following eligibility confirmation.

During the study, participants completed the supervised exercise sequence administered by the physiotherapist, as outlined in the intervention protocol. In addition, they independently performed the prescribed “homework practice” exercises at home, following the specified frequency and intensity. Each participant received an exercise brochure and a diary from the physiotherapist to document home practice sessions and adherence throughout the program.

2.8. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were verified using the Levene’s test. A mixed-design ANOVA was conducted to examine treatment effects. Within-subject effects were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA, while between-group comparisons were assessed with pairwise analyses to determine whether group response profiles remained parallel. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

In the present study, 12 patients (7 men and 6 women) participated in the LSVT program. Six patients (6 men) belonged to the group PD, while 6 patients (5 women & 1 man) had MS. The mean age of patients with MS was 45±8 years, whereas patients with PD were 68±3 years old. Βaseline measurements did not differ significantly between the two groups (p>0.05). The demographic characteristics and baseline data of all participants are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Balance

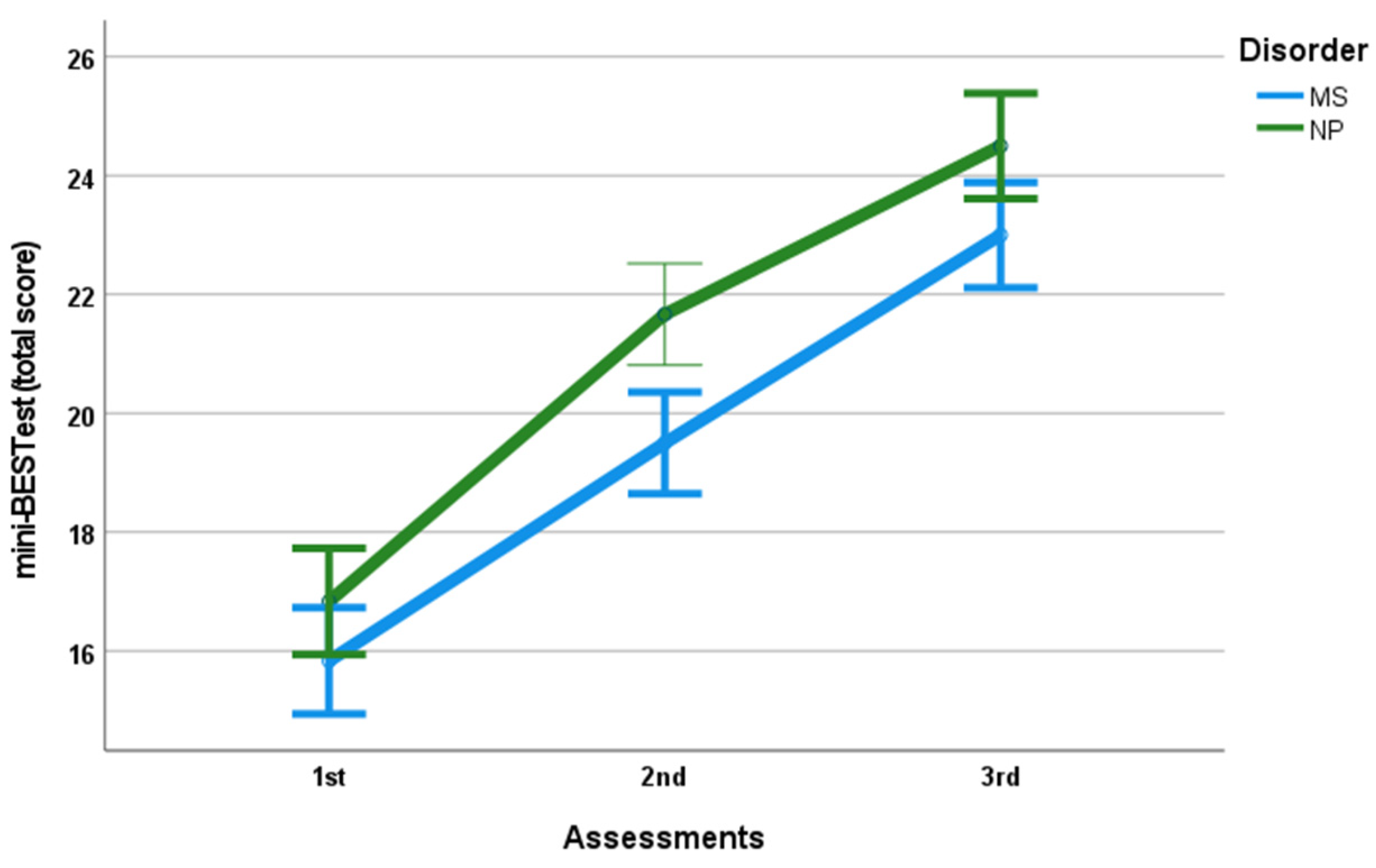

Balance improved significantly in both groups following the intervention (F

(2, 20)=325.16 p<0.001, n

2=0.97).

Figure 1 illustrates the pre-post intervention changes in mini-BESTest total scores for patients with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson's Disease (PD) displayed as separate lines.

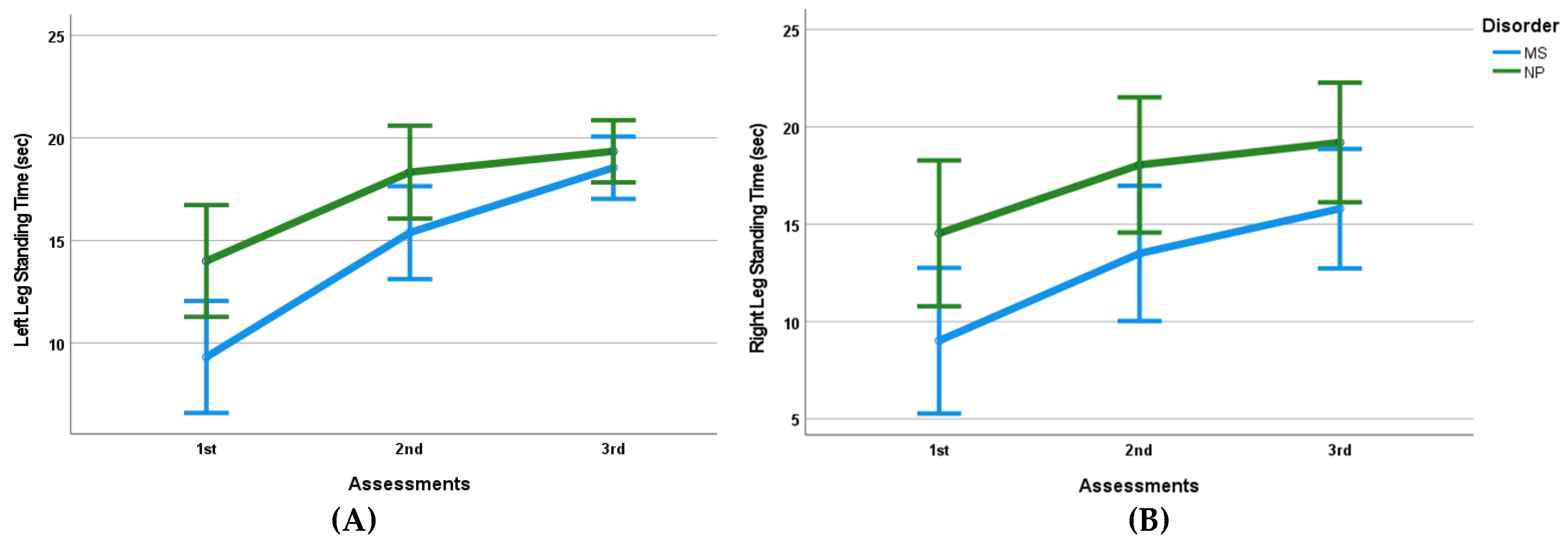

Furthermore, there was a significant increase in single-leg stance time on the left leg (F

(2, 20)=123.90, p<0.001, n

2=0.92) and on the right leg (F

(1.23, 12.33)=43.37, p<0.001, n

2=0.81). Improvements were also observed in tasks extracted from the mini-BESTest, such as standing time on a foam surface with eyes closed (F

(2, 20)=156.66, p<0.001, n

2=0.94). Standing time on an incline level with eyes closed increased significantly from baseline to post intervention (F

(1.12,12.16)=43.987, p<0.001, n

2=0.81) (

Table 2).

No significant between-group differences were found for most of the measurement outcomes, including balance (F(2, 20)=2.011, p>0.05, n2=0.17) (

Figure 1), left-leg stance time (F(2, 20)=8.316, p>0.05, n2=0.45) (

Figure 2A), or right-leg stance time (F(1.23, 12.33)=1.412, p>0.05, n2=0.12) (

Figure 2B). Consistent with these findings, the mean difference between 1st and 3rd assessments (pre–post intervention) did not differ significantly between the two groups (

Table 3).

An exception was the left-leg stance time, which showed a significant difference between groups (t9.498= 3.411, p=0.007). The MS group demonstrated a greater mean improvement (2.23±2.19 sec) compared to the PD group (5.35±1.73 sec) (

Table 3). Improvements in foam-surface stance time (F(2, 20)=0.775, p>0.05, n2=0.07) (

Figure 2C) and inclined-surface stance time (F(1.22, 12.16)=3.516, p>0.05, n2=0.26) were similar between groups (

Figure 2D).

Table 2 presents the mean scores (±SD) for all variables across the three assessments for each groups and

Table 3 presents the mean differences between the 1st and 3rd assessments.

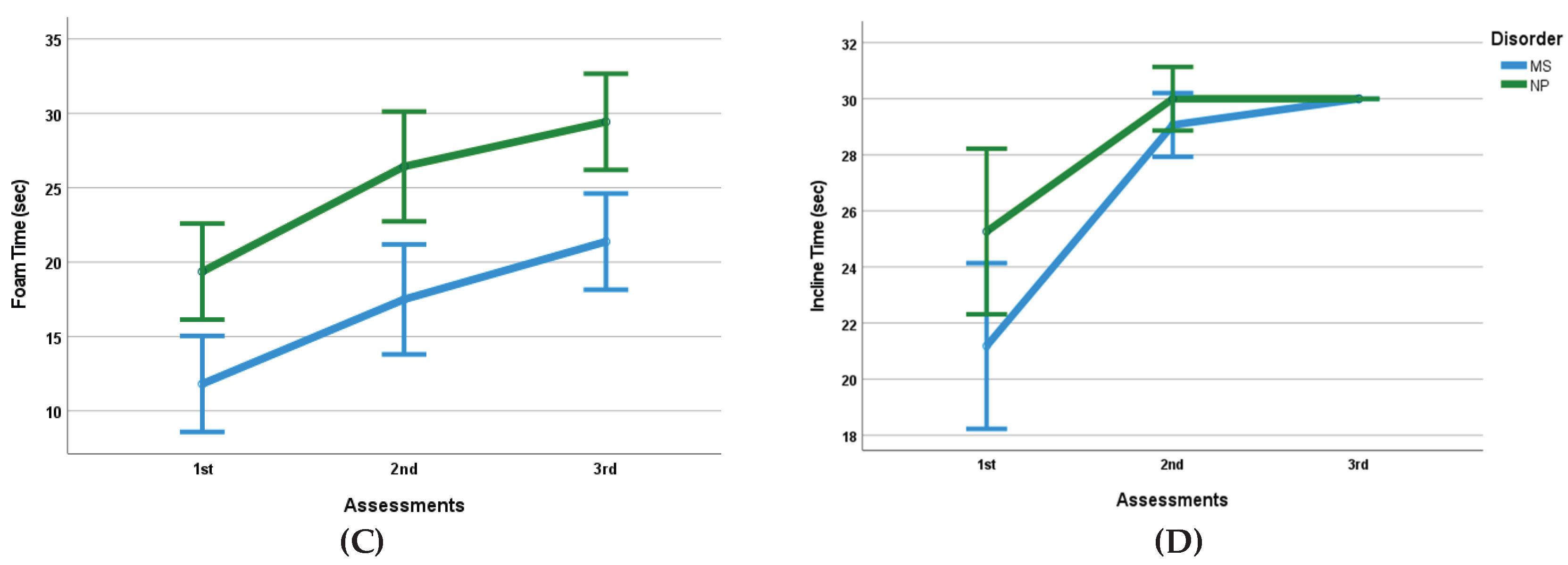

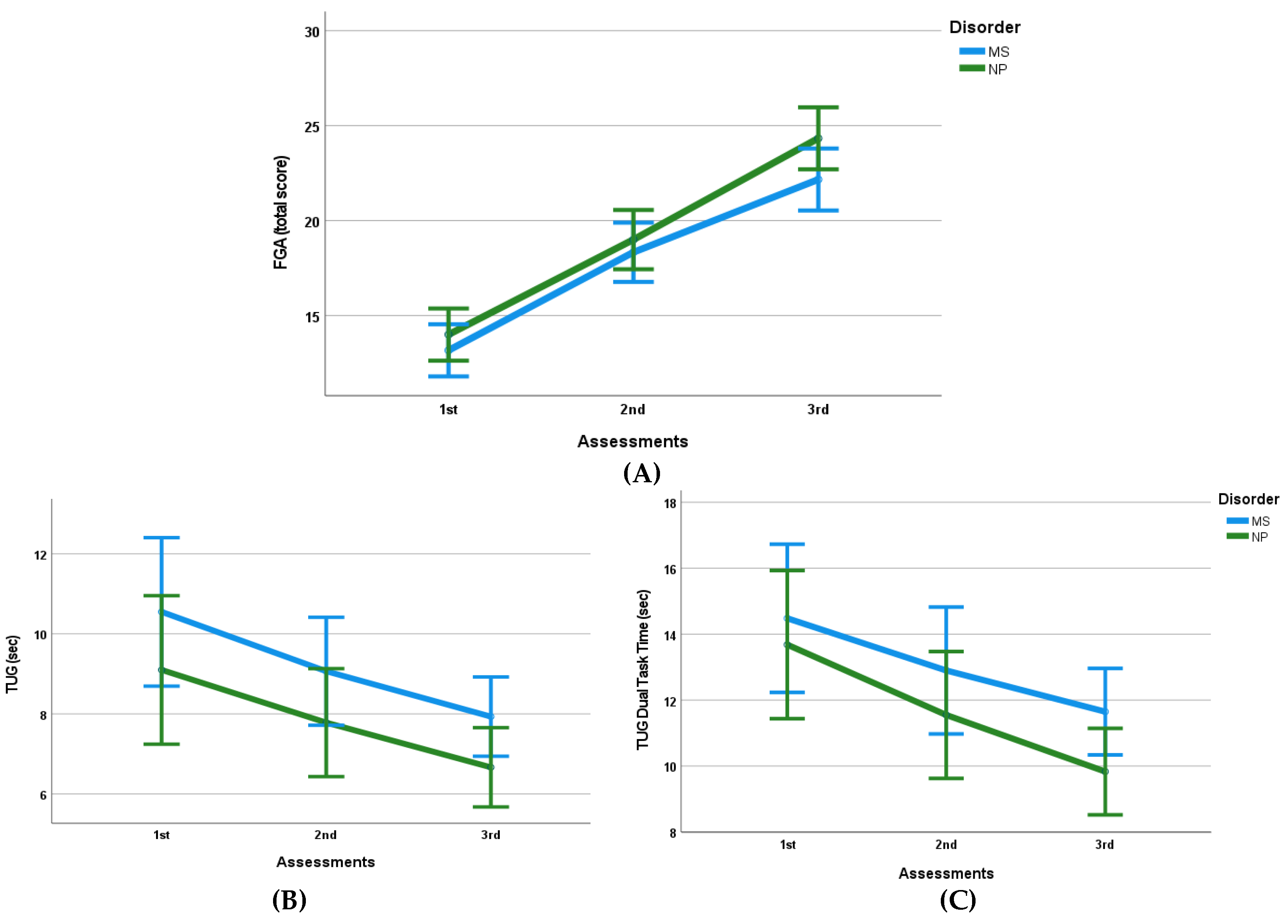

3.3. Gait Assessment

Gait performance, as this was assessed via the FGA total score, improved significantly following the intervention (F

(2, 20) = 253.79, p<0.001, n

2=0.96) (

Figure 3). The TUG test duration also improved significantly across the three measurements (F

(2,20)= 35.72, p<0.001, n

2=0.78).

No significant between-group differences were identified for either the FGA total score (F

(2,20)= 1.83, p>0.05, n

2=0.16) or TUG performance (F

(2,20)= 0.057, p>0.05, n

2=0.01) (

Figure 3B).

The dual-task TUG (counting backward by threes), extracted from the mini-BESTest, also improved significantly following the intervention (F

(2, 20) = 30.004, p<0.001, n

2=0.75). This improvement did not differ significantly between groups (F

(2,20)= 0.693, p>0.05, n

2=0.06) (

Figure 3C).

Mean differences between 1

st and 3

rd assessments were not statistically different between groups for any of the gait-related variables assessed (p>0.05) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore whether LSVT BIG — a program originally developed for improving balance and gait in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) [

3,

6,

10,

46,

47] — might likewise benefit individuals with Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Our findings indicate that, despite the fundamentally different pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MS (demyelination, axonal damage) and PD (basal ganglia degeneration), LSVT BIG produced significant and comparable improvements in balance and gait across both groups. On balance (as measured by the total score of Mini-BESTest) and on several functional parameters — including single-leg stance time (left and right), stance on foam surface with eyes closed, and stance on inclined surfaces — both MS and PD patients demonstrated notable gains. This suggests that the rehabilitative mechanisms underpinning LSVT BIG may transcend disease-specific pathology and tap into more universal principles of neural adaptation and motor relearning [

48].

One likely explanation for these improvements in MS participants is the emphasis LSVT BIG places on high-effort, task-specific, amplitude-based movements tailored to activities of daily living [

4,

5]. Long-dose rehabilitation programs with home exercises have been effective for balance rehabilitation in neurological patients [

49,

50]. Such exercises likely engage sensorimotor pathways, promote proprioceptive recalibration, and reinforce postural control strategies under varied and challenging conditions [

51,

52]. The functional nature of the LSVT program, combined with its high effort requirements, promotes neural reconstruction and neuroplasticity [

53]. Programs targeting motor functions, upper and lower limb strength, and trunk balance have improved neural tissue integrity and activation in relevant brain regions [

54,

55]. In MS — where demyelination and impaired neuronal conduction disrupt coordination and postural reflexes — repetitive high-amplitude training may support compensatory neural recruitment or strengthen residual pathways, facilitating functional reorganization, contributing to improved gait and stability [

50,

56,

57]. In this way, LSVT BIG may help mitigate deficits in balance by encouraging the central nervous system (CNS) to re-optimize motor patterns rather than relying solely on peripheral strength gains.

Moreover, the one-on-one, patient-centred delivery model of LSVT BIG may contribute to increased adherence, motivation, and engagement — factors critically important in chronic and progressive conditions such as MS [

58]. Personalized supervision and the setting of individual functional goals likely enhance patients’ commitment, leading to better quality of movement, fuller engagement with effortful tasks, and possibly greater neuroplastic change [

53,

59,

60,

61]. This stands in contrast to more generalized balance or strength training programs, which may lack specificity or intensity, and which, according to existing literature, often yield more modest improvements in neurological populations [

62,

63,

64,

65].

Compared to conventional physiotherapy or alternative modalities (e.g., Tai Chi or Pilates), LSVT BIG’s structured, intensive, amplitude-focused, task-oriented nature appears to produce larger functional gains [

10,

15]. While holistic and lower-intensity programs can improve general mobility or well being [

63], they may not sufficiently challenge the sensorimotor systems to induce the level of adaptation observed here. Furthermore, the ability of LSVT BIG to promote improvements under dual-task conditions (e.g., gait combined with cognitive load) is particularly relevant for real-world mobility, where walking rarely happens in isolation of other tasks [

46]. Improvements in dual-task TUG performance post-intervention suggest enhanced automaticity of gait and balance, possibly reflecting more efficient CNS control and better integration of motor and cognitive demands [

45,

66].

While LSVT BIG's application in MS is limited in the literature, a study applied the LSVT LOUD program for voice rehabilitation in MS patients, showing promising results in improving hypophonia [

33]. Our study extends this applicability to LSVT BIG, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing mobility, balance, and gait in MS patients. This innovative aspect underscores its significance and its clinical usefulness, promoting safer mobility in natural environments. Improved balance and gait in MS patients may reduce risk of falls, enhance safety during ambulation in daily life, and foster greater independence [

67]. Enhanced confidence in mobility can also encourage more frequent participation in physical and social activities, mitigating sedentary behavior and potentially slowing further functional decline [

5,

48]. The fact that LSVT BIG can be adapted for MS suggests that rehabilitative programs developed for one neurological disorder might, with appropriate modification, be repurposed across different conditions — promoting a more unified, neuroplasticity-based approach to neurorehabilitation. LSVT BIG has already shown promise in improving hemiplegic upper extremity function after stroke [

35,

36,

61], indicating its potential for addressing mobility in diseases affecting central motor neuronal pathways.

However, to fully substantiate these promising results, future research should include larger, ideally multicenter, cohorts of MS patients, extended follow-up to assess the durability of gains, and possibly neurophysiological or neuroimaging studies to investigate underlying CNS changes. Additionally, comparing LSVT BIG to other intensive and task-specific interventions, as well as evaluating cost effectiveness and feasibility of long-term home-based application, will be important for translating these findings into routine clinical practice.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Although the current pilot study included a number of participants comparable to previous LSVT studies [

10,

12,

47], it does not allow for definitive, population-wide conclusions. Second, this study lacked a true control group. The group of PD patients was included as a comparative cohort to indirectly evaluate the effectiveness and validity of LSVT BIG; however, the absence of a non-intervention or alternative therapy control group limits the ability to fully attribute observed improvements to the intervention. Future studies should include randomized control groups and consider comparisons with other exercise therapy programs within the same patient population. Another limitation is the absence of follow-up assessments to determine the durability of the intervention effects over time. While LSVT BIG is designed to promote neuroplasticity and motor learning, it remains unclear whether the observed gains in balance and gait are maintained in the long term. Incorporating follow-up evaluations and advanced neurophysiological assessments — such as transcranial magnetic stimulation, functional MRI, or other imaging techniques — could provide valuable insight into the neural mechanisms underlying sustained improvements..

5. Conclusions

The comparative improvements in balance and gait observed in this study suggest that LSVT BIG may confer significant benefits for patients with MS, potentially even exceeding those seen in PD patients in certain functional domains. The program’s high-intensity, task-specific, amplitude-focused exercises appear to target key motor deficits in MS, with observable carryover effects on functional activities relevant to daily living.

However, the small sample size and the absence of a healthy or non-intervention control group may limit the interpretability and generalizability of these findings. Given that research on LSVT BIG in MS is still preliminary, further studies employing randomized controlled trial designs with larger samples, detailed kinematic analyses, and long-term follow-up are warranted. Such research could confirm the efficacy, durability, and mechanistic underpinnings of LSVT BIG in MS, providing stronger evidence for its inclusion in routine neurorehabilitation programs for this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and S.L.; methodology, S.L.; software, K.A.; formal analysis, K.A. and S.L.; investigation, K.A.; resources, K.A. and S.L.; data curation, K.A. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A..; writing—review and editing, S.L., T.B., E.T., A.G., E.T.; visualization, K.A., S.L. and A.G.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece (now named University of Patras) (Reg. No. 981/14-01-2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this study is not publicly available, due to ethical restrictions. Any further reasonable requirements could be forwarded to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all patients for their voluntary participation in the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pu, T.; Huang, M.; Kong, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Wie, C.; Wenig, X.; Xu, F. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment to improve speech in Parkinson’s disease: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Parkinson’s Dis. 2021, 2021, e3366870. [CrossRef]

- Bryans, L.A.; Palmer, A.D.; Anderson, S.; Schindler, J.; Graville, D.J. The Impact of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD®) on Voice, Communication, and Participation: Findings from a Prospective, Longitudinal Study. J Commun Disord. 2020, 89, 106031. [CrossRef]

- Ebersbach, G.; Ebersbach, A.; Edler, D.; Kaufhold, O.; Kusch, M.; Kupsch, A.; Wissel, J. Comparing exercise in Parkinson’s disease-the Berlin BIG Study. Mov. Dis. 2010, 25(12), 1902-1908. [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Ebersbach, G.; Ramig, L.; Sapir, S. LSVT LOUD and LSVT BIG: Behavioral Treatment Programs for Speech and Body Movement in Parkinson Disease. Parkinson’s Dis. 2012, 2012, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Farley, B.G.; Fox, C.M.; Ramig, L.O. McFarland, DH. Intensive Amplitude-specific Therapeutic Approaches for Parkinsonʼs Disease. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24(2), 99-114. [CrossRef]

- Peterka, M.; Odorfer, T.; Schwab, M.; Volkmann, J.; Zeller, D. LSVT-BIG therapy in Parkinson’s disease: physiological evidence for proprioceptive recalibration. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20(1), 276. [CrossRef]

- Konczak, J.; Krawczewski, K.; Tuite, P.; Maschke, M. The perception of passive motion in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2007, 254(5), 655-663. [CrossRef]

- Conte, A.; Khan, N.; Defazio, G.; Rothwell, J.C.; Berardelli, A. Pathophysiology of somatosensory abnormalities in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neuro. 2013, 9(12), 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, A.; Matsushima, A.; Saito, M.; Sakurai, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Yoshiki, S. Quantitative assessment of the gait improvement effect of LSVT BIG® using a wearable sensor in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Heliyon. 2023, 9(6), e16952-e16952. [CrossRef]

- Janssens, J.; Malfroid, K.; Nyffeler, T.; Bohlhalter, S.; Vanbellingen, T. Application of LSVT BIG Intervention to Address Gait, Balance, Bed Mobility, and Dexterity in People with Parkinson Disease: A Case Series. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94(7), 1014-1023. [CrossRef]

- Clarkin, C. LSVT®BIG Exercise-Induced Neuroplasticity in People with Parkinson’s Disease: An Assessment of Physiological and Behavioral Outcomes. Open Access Dissertations. University of Rhode Island, ProQuest Number: 27741888, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Flood, M.W.; O’Callaghan, B.P.F.; Diamond, P.; Liegey, J.; Hughes, G.; Lowery, M.M. Quantitative clinical assessment of motor function during and following LSVT-BIG® therapy. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2020, 17(1), 92. [CrossRef]

- Doucet, B. M.; Blanchard, M.; Franc, I. Effects of LSVT BIG® on Bradykinesia During Activities of Daily Living. OTJR: Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2025, 0(0) 15394492251367275. [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, Z.; Tahan, N.; Ganjeh, S.; Baghban, A.A.; Khoshdel, A.; Shoeibi, A. Evaluating the Impact of Adding Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG into Routine Physiotherapy on Both Motor and Nonmotor Functions in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Dubai Medical Journal, 2025, 8(1), 12–22. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Rischbieth, B.; Schammer, T.T.; Seaforth, C.; Shaw, A.J.; Phillips, A.C. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT)-BIG to improve motor function in people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 32(5), 607-618. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Oh, H.M.; Bok, S.K.; Chang, W.H.; Choi, Y.; Chun, M.H.; Han, S.J.; Han, T.R.; Jee, S.; Jung, S.H.; Jung, H.Y.; Jung, T.D.; Kim, M.W.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Ko, S.H.; Ko, M.H.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.G.; Lim, S.H.; Oh, B.M.; … Yang, S.N.; Yoo S.D.; Yoo, W.K. KSNR Clinical Consensus Statements: Rehabilitation of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Neurorehabil. 2020, 13(2), e17. [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, O.; Wingerchuk, D. Epidemiology and natural history of multiple sclerosis: new insights. Cur. Opin. Neurol. 2006, 19(3), 248-254. [CrossRef]

- Amatya, B.; Khan, F.; Galea, M. Rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 14, 1(1), CD012732. [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, K.J.; Spence, W.; Solomonidis, S.; Apatsidis, D. The characterisation of gait patterns of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32(15), 1242-1250. [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.; Khan, F.; Kesselring, J. Rehabilitation interventions in multiple sclerosis: an overview. J. Neurol. 2012, 259(9), 1994-2008. [CrossRef]

- Barin, L.; Salmen, A.; Disanto, G.; Babačić, H.; Calabrese, P.; Chan, A.; Kamm, C.P.; Kesselring, J.; Kuhle, J.; Gobbi, C.; Pot, C.; Puhan, M.A.; von Wyl, V.; Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Registry (SMSR). The disease burden of Multiple Sclerosis from the individual and population perspective: Which symptoms matter most? Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018, 25, 12-121. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, F.; Rochester, L.; Paul, L.; Rafferty, D.; O’Leary, C.; Evans, J. Walking and talking: an investigation of cognitive—motor dual tasking in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15(10), 1215-1227. [CrossRef]

- White, L.J.; McCoy, S.C.; Castellano, V.; Gutierrez, G.; Stevens, J.E.; Walter, G.A.; Vandenborne, K. Resistance training improves strength and functional capacity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10(6), 668-674. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, AEG. Exercise in Multiple Sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2013, 24(4), 605-618. [CrossRef]

- Feltham, M.G.; Collett, J.; Izadi, H.; Wade, D.T.; Morris, M.G.; Meaney, A.J.; Howells, K.; Sackley, C.; Dawes, H. Cardiovascular adaptation in people with multiple sclerosis following a twelve week exercise programme suggest deconditioning rather than autonomic dysfunction caused by the disease. Results from a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013, 49(6), 765-774.

- Halabchi, F.; Alizadeh, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Abolhasani, M. Exercise prescription for patients with multiple sclerosis; potential benefits and practical recommendations. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17(1), 185. [CrossRef]

- Duff, W.R.D.; Andrushko, J.W.; Renshaw, D.W.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Farthing, J.P.; Danielson, J.; Evans, C.D.; Impact of Pilates Exercise in Multiple Sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018, 20(2), 92-100. [CrossRef]

- Kalron, A.; Rosenblum, U.; Frid, L.; Achiron, A. Pilates exercise training vs. physical therapy for improving walking and balance in people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 31(3), 319-328. [CrossRef]

- Soysal, Tomruk, M.; Zu, M.Z.; Kara, B.; İdiman, E. Effects of Pilates exercises on sensory interaction, postural control and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016, 7, 70-73. [CrossRef]

- Alphonsus, K.B.; Su, Y.; D’Arcy, C. The effect of exercise, yoga and physiotherapy on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019, 43, 188-195. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Taylor-Piliae, R.E. The effects of Tai Chi on physical and psychosocial function among persons with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2017, 31, 100-108. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Jing, Y.; Li, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Rehabilitation treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1168821. [CrossRef]

- Baldanzi, C.; Crispiatico, V.; Foresti, S.; Groppo, E.; Rovaris, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Vitali, C. Effects of Intensive Voice Treatment (The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment [LSVT LOUD]) in Subjects With Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. J. Voice. 2022, 36(4), 585.e1-585.e13. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, V.; Egan, M.; Sauvé-Schenk, K. LSVT BIG in late stroke rehabilitation: A single-case experimental design study. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 86, 87–94. [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, R.M.; Henderson, W.; Scholl, S.; Nettleton, M. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment BIG® for a Person With Stroke. Am J Occup Ther. 2018, 72(5), 7205210010p1-7205210010p6. [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, R.; Henderson, W.; Stupps, M.; Binder, L.; Irlmeier, B.; Knapp E. Feasibility of the Lee Silverman voice treatment-BIG intervention in stroke. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health. 2021, 41, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Fiorenzato, E.; Cauzzo,S.; Weis, L.; Garon, M.; Pistonesi, F.; Cianci, V.; Nasi, L.M.; Vianello, F.; Zecchinelli, L.A.; Pezzoli, G.; Reali, E.; Pozzi, Β.; Isaias, U.I.; Siri, C.; Santangelo, G.; Cuoco, S.; Barone, P.; Antonini, A.; Biundo, R. Optimal MMSE and MoCA cutoffs for cognitive diagnoses in Parkinson's disease: A data-driven decision tree model. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 466, 123283. [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Horak, F.; Godi, M.; Nardone, A.; Giordano, A. Using psychometric techniques to improve the Balance Evaluation Systems Test: The mini-BESTest. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulou, S.I.; Billis, E.; Gedikoglou, I.A.; Michailidou, C.; Nowicky, A.V.; Skrinou, D.; Michailidi, F.; Chandrinou, D.; Meligkoni, M. Reliability, validity and minimal detectable change of the Mini-BESTest in Greek participants with chronic stroke. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2019, 35, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.V.; Horak, F.B.; Tran, V.K.; Nutt, J.G. Multiple balance tests improve the assessment of postural stability in subjects with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006, 77(3), 322-326. [CrossRef]

- Wrisley, D.M.; Marchetti, G.F.; Kuharsky, D.K.; Whitney, S.L. Reliability, internal consistency, and validity of data obtained with the functional gait assessment. Phys Ther. 2004, 84(10), 906-18.

- Lampropoulou, S.; Kellari, A.; Gedikoglou, I.A.; Kozonaki, D.G.; Nika, P.; Sakellari, V. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Characteristics of the Greek Functional Gait Assessment Scale in Healthy Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Appl. Sci., 2024, 14(2), 520. [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Fantino, B.; Allali, G.; Muir, S.W.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Annweiler, C. Timed Up and Go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging 2011 15(10), 933-8. [CrossRef]

- Barry, E. Galvin, R.; Keogh, C.; Horgan, F.; Fahey, T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kahya, M.; Moon, S.; Ranchet, M.; Vukas, R.R.; Lyons, E.K.; Pahwa, R.; Akinwuntan, A.; Devos H. Brain activity during dual task gait and balance in aging and age-related neurodegenerative conditions: A systematic review. Exp Gerontol. 2019, 128, 110756. [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, S.; O’Brien, A.; Lazaro, J.D.; Ray, A.; Fluet, G. The JFK BIG study: the impact of LSVT BIG® on dual task walking and mobility in persons with Parkinson’s disease. J Phys Ther Sci. 2018, 30(4), 636-641. [CrossRef]

- Fishel, S.C.; Hotchkiss, M.E.; Brown, S.A. The impact of LSVT BIG therapy on postural control for individuals with Parkinson disease: A case series. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020, 36(7), 834-843. [CrossRef]

- Luna, G.; Pardo-Cocuy, .LF.; Garzón, A.; Benítez, A.; Parada-Gereda, H.M. Effectiveness of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT®BIG) for improving motor function in patients with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2025, 104(12), 1105-1112. [CrossRef]

- Boissoneault, C.; Datta, S.; Rose, D.K.; Waters, M.J.; Khanna, A.; Daly, J.J. Innovative Long-Dose Neurorehabilitation for Balance and Mobility in Chronic Stroke: A Preliminary Case Series. Brain Sci. 2020, 10(8), 555. [CrossRef]

- Corrini, C.; Gervasoni, E.; Perini, G.; et al. Mobility and balance rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023, 69, 104424. [CrossRef]

- Zemková, E.; Hamar, D. The Effect of Task-Oriented Sensorimotor Exercise on Visual Feedback Control of Body Position and Body Balance, Hum. Mov. 2010, 11(2): 119-123. [CrossRef]

- Asghari, S.H.; Ilbeigi, S.; Ahmadi, M.M.; Yousefi, M.; Mousavi-Mirzaei, M. Comparative effects of sensory motor and virtual reality interventions to improve gait, balance and quality of life MS patients. Sci Rep. 2025, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Petzinger, G.M.; Fisher, B.E.; McEwen, S.; Beeler, J.A.; Walsh, J.P.; Jakowec, M.W. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12(7), 716-26. [CrossRef]

- Procházková, M.; Tintera, J.; Špaňhelová, S.; Prokopiusova, T.; Rydlo, J.; Pavlikova, M.; Prochazka, A.; Rasova, K. Brain activity changes following neuroproprioceptive “facilitation, inhibition” physiotherapy in multiple sclerosis: a parallel group randomized comparison of two approaches. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2021, 57(3), 356-365. [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi, E.; Cazzoli, M.; Pirastru, A.; Blasi, V.; Rovaris, M.; Bergsland, N.; Baglio, F. Neuroplasticity and Motor Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review on MRI Markers of Functional and Structural Changes. Front Neurosci. 2021, 15, 707675. [CrossRef]

- Straudi, S.; Martinuzzi, C.; Pavarelli, C.; Sabbagh Charabati, A.; Benedetti, M.G.; Foti, C.; Bonato, M.; Zancato, E.; Basaglia, N. A task-oriented circuit training in multiple sclerosis: a feasibility study. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 124. [CrossRef]

- Darwish, H.M.; Shalaby, M.N.; Ali, S.A.; Soubhy, Z.H. Effect of Task Oriented Approach on Balance in Ataxic Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2019, 87 (7), 4789-4794. [CrossRef]

- Salmani, S., Mousavi, S.H., Navardi, S.; Hosseinzadeh, F.; Pashaeypoor, S. The barriers and facilitators to health-promoting lifestyle behaviors among people with multiple sclerosis during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a content analysis study. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22 (1), 490. [CrossRef]

- Bombard, Y., Baker, G.R., Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis J.L.; Pomey M.P. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implementation Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Fettes, L.; Takemura, N.; Bayly, J.; Talbot-Rice, H.; Turner, K.; Tiberini, R.; Harding, R.; Murtagh E.M.F.; Siegert, R.J.; Higginson, I.J.; Ashford, S.A.; Turner-Stokes L. Functional goals and outcomes of rehabilitation within palliative care: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2025, 24(1), 172. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, V.; Egan, M.; Sauvé-Schenk K. LSVT BIG in late stroke rehabilitation: A single-case experimental design study. Can J Occup Ther. 2019, 86(2), 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Bouça-Machado, R.; Rosário, A.; Caldeira, D.; Castro Caldas, A.; Guerreiro, D.; Venturelli, M.; Tinazzi, M.; Schena, F.; Ferreira J. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physiotherapy in Parkinson's Disease: Defining the Concepts. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2019, 7(1), 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; He, Y.; He, M. The comprehensive impact of exercise interventions on cognitive function and quality of life in alzheimer’s disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2025 25, 871. [CrossRef]

- Paltamaa, J.; Sjögren, T.; Peurala, S.; Heinonen, A. Effects of physiotherapy interventions on balance in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2012, 44(10), 811-23. [CrossRef]

- Snook, E.M.; Motl, R.W. Effect of Exercise Training on Walking Mobility in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2008, 23(2), 108-116. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.R.; Tsai, Y.A.; Wang, R.Y. Cognitive and motor dual task gait training improve dual task gait performance after stroke - A randomized controlled pilot trial. Sci Rep. 2017, 7(1), 4070. [CrossRef]

- Comber, L.; Peterson, E.; O'Malley, N.; Galvin, R.; Finlayson, M.; Coote, S. Development of the Better Balance Program for People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Complex Fall-Prevention Intervention. Int J MS Care. 2021, 23(3), 119-127. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).