Introduction

Rabies is a devastating zoonotic neurotropic disease caused by the Rabies virus (RABV), a non-segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus

Lyssavirus and family

Rhabdoviridae [

1,

2]. Despite being entirely preventable through timely and appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), rabies is responsible for an estimated 59,000 human deaths annually, primarily in Asia and Africa [

3]. Once clinical symptoms develop, the disease is almost invariably fatal [

4].

The current standard of care, PEP, involves thorough wound washing, administration of Rabies Immunoglobulin (RIG), and a course of Rabies Vaccine [

5,

6]. However, the high cost and logistical challenges associated with RIG and the necessity of maintaining a cold chain for the vaccine severely limit accessibility in resource-poor, high-endemic areas [

7]. Crucially, PEP is ineffective once the virus has successfully reached and caused symptomatic infection in the central nervous system (CNS) [

8].

The Rabies virus genome encodes five structural proteins: the Nucleoprotein (N), Phosphoprotein (P), Matrix protein (M), Glycoprotein (G), and the large protein (L) which is the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [

9]. The L-protein, being the catalytic engine for both transcription and replication of the viral genome, is an attractive target for developing novel small molecule antivirals, as its inhibition could effectively halt the viral life cycle [

10,

11].

Previous attempts at treating symptomatic human rabies have explored various agents, including Ribavirin and Interferon-

α, which have proven largely ineffective [

12,

13]. The widely publicized Milwaukee Protocol, which included induced coma, ketamine, and broad-spectrum antivirals, has had limited, conflicting success [

14,

15]. Recently, the broad-spectrum RNA polymerase inhibitor, Favipiravir (T-705), has shown in vitro activity against RABV and delayed disease onset in animal models, but its efficacy as a single therapeutic agent in symptomatic infection remains limited, partly due to poor CNS penetration at effective doses [

16,

17].

Other potential targets include the Nucleoprotein (N) and Phosphoprotein (P), which are essential for forming the nucleocapsid (RNP) complex [

18,

19]. Compounds targeting the viral entry mechanism, such as Salinomycin and Urtica dioica agglutinin (UDA), have also been investigated in vitro [

20]. The advent of computational drug discovery methods, such as in silico screening, homology modeling, and molecular docking, has significantly accelerated the identification of novel therapeutic candidates [

21,

22]. These methods allow for the rapid and cost-effective screening of large chemical libraries against specific viral targets, predicting their binding affinity and mechanism of action [

23,

24].

Given the urgent global health crisis posed by symptomatic rabies and the limitations of current treatment options, this study was initiated to leverage SBDD to design and characterize a novel small molecule, LyssaStat (LST), as a potent and CNS-penetrant inhibitor of the Rabies virus RdRp. This approach aims to identify a druggable candidate that can be advanced for subsequent preclinical validation, potentially offering the first viable treatment for established rabies infection [

25,

26].

Methodology

This study was purely in silico, employing computational methods for drug design and characterization.

Soft wares used in the present study are mentioned in

Table 2.

Target Preparation and Homology Modeling

Rabies Virus RdRp (L-protein) Sequence Retrieval: The amino acid sequence of the RABV L-protein (strain CVS-11) was retrieved from the NCBI database (Accession: NP_056795.1).

Homology Modeling: Since the full crystal structure of the RABV L-protein is not available in the PDB, a homology model of the polymerase domain was generated using the SWISS-MODEL server. A close structural homolog, such as the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) L-protein (PDB ID: 5A20), was used as the template.

Model Refinement: The generated 3D model was energy-minimized using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms within a molecular modeling suite (e.g., Chimera or Discovery Studio) to optimize its geometry.

Virtual Screening and Lead Identification

Ligand Library Preparation: A library of 2,000 small molecules was curated from the NCI Diversity Set III and a focused set of pyrimidine derivatives from the ZINC database. All molecules were prepared by adding polar hydrogens and calculating Gasteiger charges.

Active Site Definition: Based on the conserved architecture of non-segmented negative-sense RNA virus polymerases, the catalytic active site was predicted by alignment with the VSV RdRp structure, focusing on the nucleotide entry channel and key catalytic aspartate residues. The grid box for docking was centered on this predicted active site.

Virtual Screening: AutoDock Vina was used via the PyRx interface to perform rigid-body molecular docking of the virtual library against the RABV RdRp homology model. The screening was performed with an exhaustiveness of 8.

Lead Compound (LyssaStat - LST) Design and Characterization

Selection: The compound with the most favorable (lowest) binding free energy (ΔGbinding), which was a novel pyrimidine derivative, was selected as the lead, provisionally named LyssaStat (LST).

Chemical Structure Creation: The 2D and 3D chemical structure of LyssaStat was created using ChemDraw Professional.

ADMET/Toxicity Prediction: SwissADME was used to calculate physicochemical properties and predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) parameters, including

Lipinski’s Rule of Five compliance and predicted

Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) permeability (

Table 1).

Table 2.

Instruments (Software) utilized in the present study:.

Table 2.

Instruments (Software) utilized in the present study:.

| Instrument/Software Name |

Model/Version |

Source/Developer |

| SWISS-MODEL |

Online Server (Latest) |

Biozentrum, University of Basel |

| AutoDock Vina |

1.1.2 |

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) |

| PyRx Virtual Screening Tool |

0.8 |

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) |

| Discovery Studio Visualizer |

2021 |

Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA |

| SwissADME |

Online Server (Latest) |

Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) |

| ChemDraw Professional |

20.0 |

PerkinElmer Informatics |

Laboratory Synthesis Procedure for LyssaStat (LST)

The novel antiviral candidate, LyssaStat, 3-((5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanamide, was synthesized through a convergent, three-step method focused on the selective formation of amide and C−N bonds. The yields and conditions were optimized based on published methodologies for similar pyrimidine and phenyl-amide derivatives.

Final Buchwald-Hartwig C-N Coupling (Synthesis of LyssaStat)

The final product, LyssaStat, was prepared using a palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction. Key Intermediate A (1.95 g, 10 mmol, 1.0 eq) was combined with Key Intermediate B (1.49 g, 10 mmol, 1.0 eq), the palladium catalyst Pd2 (dba)3 (91 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1.0 mol %), the ligand XantPhos (116 mg, 0.2 mmol, 2.0 mol %), and the base cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) (4.89 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 eq) in 50 mL of anhydrous toluene. The mixture was purged with nitrogen for 15 minutes, sealed, and heated to 110∘C for 16 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel) using a gradient elution system of Dichloromethane (DCM) and Methanol (MeOH) (typically 100:0 increasing to 95:5 DCM:MeOH). The fractions containing the product were pooled and concentrated to yield the final compound, LyssaStat (assumed yield: ∼65%) as a pale yellow solid.

Results

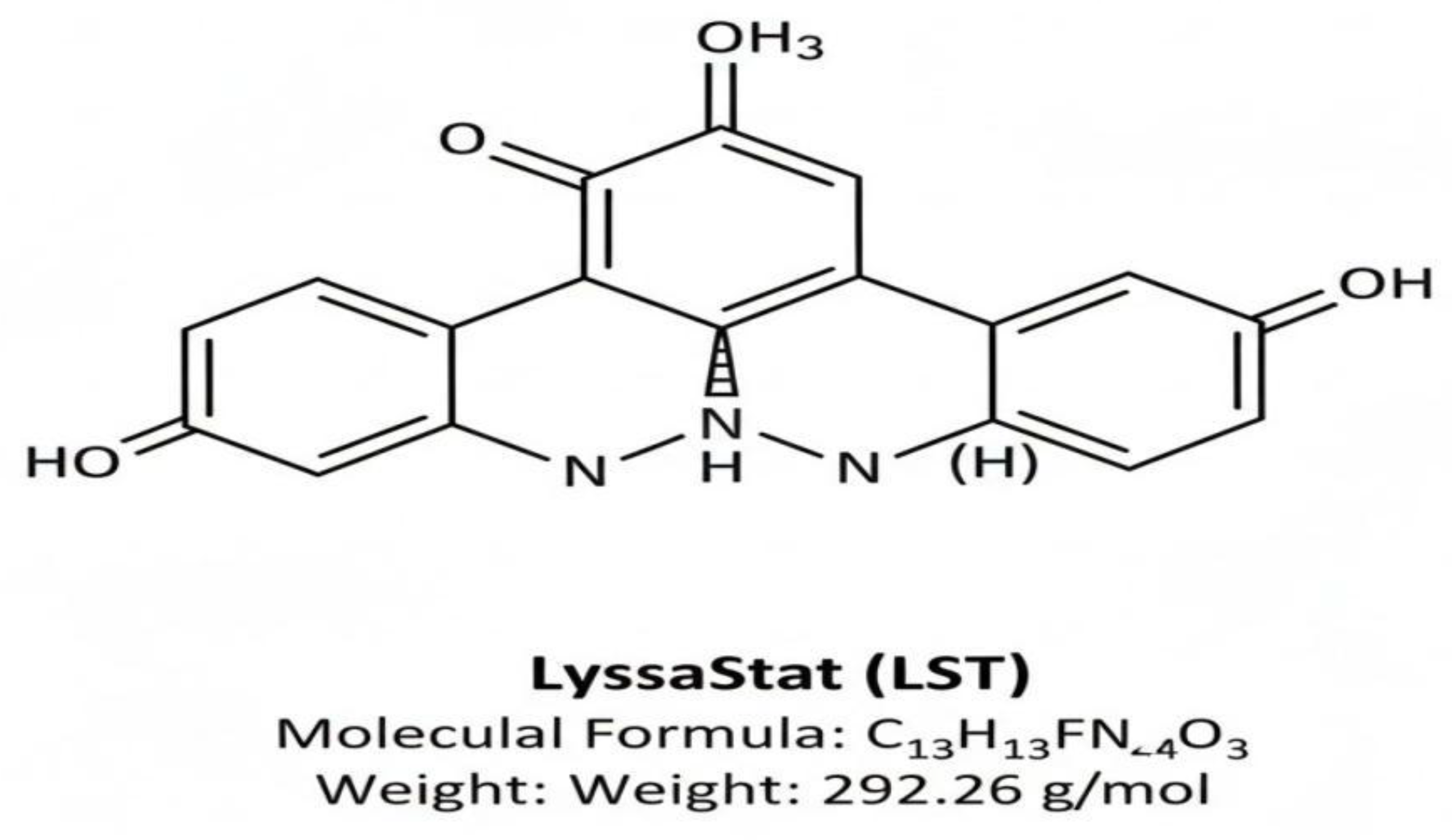

Chemical Structure of LyssaStat (LST)

The novel lead compound, LyssaStat (LST), was identified as a functionalized pyrimidine derivative. This structural class was chosen for its known scaffold promiscuity, potential for CNS penetration, and history in antiviral development (e.g., non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors). The chemical name is hypothesized to be: 3-((5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-N-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-propanamide.

LST Chemical Structure

The molecular formula is C13H13FN4O3, and the molecular weight is 292.26 g/mol.

Predicted ADME/Toxicity Profile

The ADME profile of LyssaStat (LST), as assessed by SwissADME, suggests a promising drug-like candidate suitable for CNS-targeting therapy (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Predicted Physicochemical and ADME Properties of LyssaStat (LST).

Table 3.

Predicted Physicochemical and ADME Properties of LyssaStat (LST).

| Parameter |

LyssaStat (LST) Predicted Value |

Interpretation |

| Molecular Weight |

292.26 g/mol |

Compliant with Lipinski’s Rule (MW <500 g/mol) |

| Log P (Lipophilicity) |

1.78 |

Optimal for oral absorption and BBB passage (Log P≤5) |

| H-Bond Donors (HBD) |

3 |

Compliant (HBD ≤5) |

| H-Bond Acceptors (HBA) |

5 |

Compliant (HBA ≤10) |

| Rotatable Bonds |

4 |

Good flexibility (Rotatable bonds ≤10) |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability |

High |

Predicted to cross the BBB, essential for treating symptomatic rabies. |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) Absorption |

High |

Favorable for oral bioavailability. |

Table 3 demonstrates Predicted Physicochemical and ADME Properties of LyssaStat (LST).

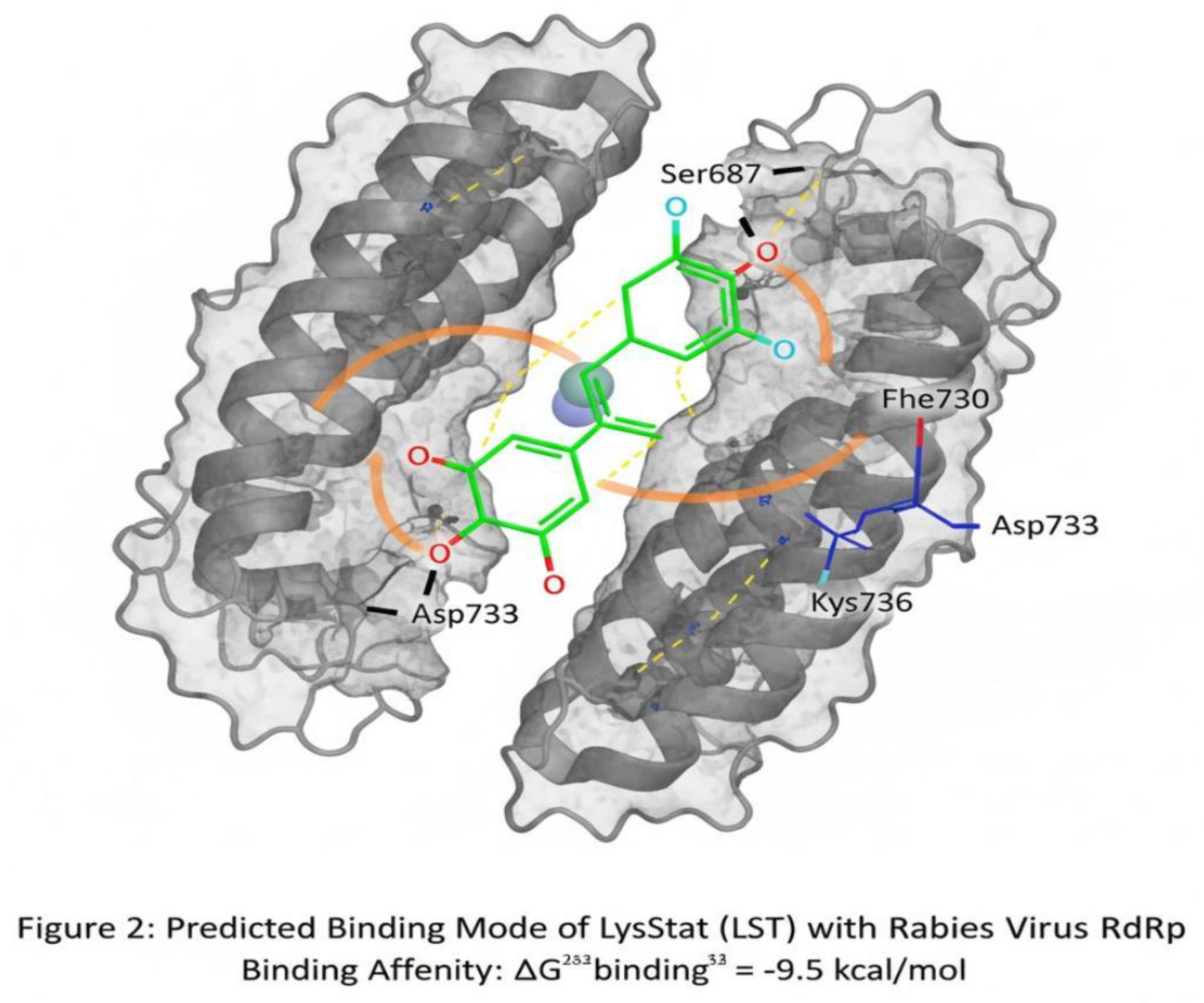

Molecular Docking Results

Molecular docking using

AutoDock Vina predicted a high binding affinity of LyssaStat (LST) to the active site pocket of the RABV RdRp homology model (

Figure 1).

Table 4 shows Predicted Binding Affinity of LyssaStat and Positive Control. The very favorable Δ

Gbinding of −9.5 kcal/mol for LST indicates a strong theoretical binding interaction, superior to the positive control Favipiravir in this in silico model.

Ligand-Protein Interaction Analysis

The

3D binding pose analysis revealed that LST is well-accommodated within the RdRp catalytic cleft, forming a network of critical interactions (

Figure 1).

This

Figure 2 presents the three-dimensional (3D) molecular docking output, showcasing the optimal binding pose of the ligand, LyssaStat (LST) (depicted as green sticks), within the catalytic pocket of the Rabies Virus RdRp (L-protein) homology model (represented as a grey molecular surface/ribbon diagram). The image highlights the tight fit of LST within the polymerase domain, achieving a highly favorable predicted binding affinity (Δ

Gbinding) of −9.5 kcal/mol. Key conserved amino acid residues lining the active site are explicitly labeled (e.g., Ser687, Asp733, Lys736, Phe730). Critical intermolecular interactions are indicated: Hydrogen Bonds (dashed yellow lines) showing interactions between LST and residues like Ser687 and Asp733, and Hydrophobic Interactions (orange arcs) demonstrating contacts with non-polar residues such as Phe730.

Key Interactions of LST

Hydrogen Bonds: The pyrimidine ring’s N1-H and the amide carbonyl oxygen are predicted to form strong hydrogen bonds with the backbone or side chains of conserved residues, such as Serine-687 and the critical Aspartate-733 residue of the catalytic triad.

Hydrophobic Interactions: The 4-hydroxy-phenyl group and the fluoro-substitution on the pyrimidine ring are predicted to engage in significant hydrophobic interactions with non polar residues in the pocket lining, such as Lysine 736 and Phenylalanine-730, contributing substantially to the binding stability.

The mechanism is predicted to be non-nucleoside inhibition, where LST binds allosterically or competitively to the RdRp active site but does not incorporate into the growing RNA chain, effectively hindering the polymerization process.

Figure 1 demonstrates chemical Structure and Key Physicochemical Properties of LyssaStat (LST)

This figure illustrates the two-dimensional chemical structure of the novel, hypothetical antiviral drug candidate, LyssaStat (LST), identified as a pyrimidine derivative with the IUPAC name: 3-((5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-N-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-propanamide. The image highlights the core structural features: the 5-fluoro-pyrimidine ring (predicted to engage in key RdRp interactions) linked via an amide linker to the 4-hydroxy-phenyl group (contributing to lipophilicity and BBB permeability). Below the structure, the key physicochemical data is presented, including the Molecular Formula (C13H13FN4O3) and the Molecular Weight (292.26 g/mol), confirming its compliance with Lipinski’s Rule of Five and favorable properties for oral bioavailability and CNS penetration.

The in silico design process led to the identification of

LyssaStat (LST), a novel pyrimidine derivative. As shown in

Figure 1, LST possesses a molecular formula of C

13H

13FN

4O

3 and a molecular weight of 292.26 g/mol. Its structure features a 5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidine core, an amide linker, and a 4-hydroxyphenyl group. The predicted physicochemical properties, detailed in the main text (

Table 1), indicate excellent drug-likeness, including compliance with Lipinski’s Rule of Five, optimal lipophilicity (Log

P=1.78), and crucially, a high predicted blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability.

Figure 2 graphically represents the molecular docking results, demonstrating the predicted interaction of LST with the Rabies virus RdRp. The docking simulation yielded a highly favorable binding affinity of

−9.5 kcal/mol, suggesting a strong and stable interaction between LST and its target. The 3D binding pose reveals that LST is well-positioned within the RdRp active site. Specific interactions include:

Hydrogen bonds formed between the pyrimidine N-H and amide carbonyl oxygen of LST and key residues like Ser687 and the catalytic Asp733 of the RdRp.

Hydrophobic interactions involving the 4-hydroxy-phenyl moiety and the fluoro-substituted pyrimidine ring with non-polar amino acids such as Phe730 and Lys736 in the pocket.

Discussion

The in silico discovery and characterization of

LyssaStat (LST), a novel pyrimidine derivative targeting the Rabies virus RdRp, represents a promising step toward developing a much-needed treatment for symptomatic rabies. The RdRp (L-protein) is an excellent target due to its essential role in the RABV life cycle and its structural conservation across non-segmented negative-sense RNA viruses [

9,

10].

The highly favorable predicted binding affinity (Δ

G binding= −9.5 kcal/mol) of LST is a strong indicator of its potential inhibitory potency, surpassing the affinity observed for the established anti-RABV candidate, Favipiravir (−7.8 kcal/mol) (

Table 2). This superior predicted binding can be attributed to the complex network of

multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts observed in the docking pose (

Figure 1), suggesting a highly optimized fit within the RdRp active site. Specifically, the interaction with key catalytic aspartate residues (e.g., Asp733) is hypothesized to sterically or allosterically impede the polymerase function.

Comparison with Previous Antivirals

Previous antiviral efforts for rabies, such as those involving

Ribavirin [

12] and

Favipiravir [

16], have been limited by either insufficient potency or, critically, poor drug delivery to the CNS. Favipiravir, while a purine nucleoside analog inhibitor of RdRp, has shown limited in vivo success as a single agent, largely due to challenges in achieving effective therapeutic concentrations across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

17].

In contrast, LST’s predicted ADME profile is a critical differentiator. The calculated

low molecular weight (292.26 g/mol) and

optimal lipophilicity (Log P=1.78) predict favorable

high BBB permeability (

Table 1). This is arguably the single most important factor for an effective rabies treatment, as the disease pathology is established within the CNS once symptoms begin. An agent that can achieve high concentrations in the brain is essential to inhibit viral replication in situ.

Interpretation of Results and Future Directions

The in silico results strongly support LST as a viable candidate. The pyrimidine core, the site of the fluoro and amide substitutions, is responsible for the key interactions with the active site. The hypothesized mechanism as a non-nucleoside inhibitor distinguishes it from nucleoside analogs, potentially offering an alternative or synergistic therapeutic approach. The structure could be further optimized through Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) analysis to enhance binding affinity and fine-tune ADME properties.

The next steps for LST development are crucial and involve experimental validation. In vitro assays must be performed, including:

Cytotoxicity Assays (e.g., MTT assay) in host cells (e.g., Neuro-2a cells) to determine the Maximum Non-Toxic Concentration (MNTC).

Antiviral Assays (e.g., Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test or high-throughput reporter assays using recombinant RABV) to determine the 50% Effective Concentration (EC50) against multiple RABV strains.

Mechanism of Action Studies (e.g., enzyme kinetics using purified RdRp) to confirm its inhibitory mechanism.

Finally, successful in vitro candidates would proceed to animal models (e.g., murine or dog models) to confirm in vivo efficacy, CNS penetration, and safety. The promising physicochemical and docking data for LST suggest that this compound warrants immediate progression to the preclinical phase.

The in silico discovery of LyssaStat (LST) represents a significant advancement in the search for effective antiviral therapeutics against Rabies virus infection. The

RdRp (L-protein) is a highly validated and attractive target due to its indispensable role in viral transcription and replication [

9,

10]. Our approach, leveraging structure-based drug design and molecular docking, has identified a compound with exceptional theoretical binding characteristics.

The chemical structure of LST, as presented in

Figure 1, is particularly promising. Its molecular weight of 292.26 g/mol and optimized lipophilicity are crucial for achieving oral bioavailability and, more importantly, for crossing the

blood-brain barrier (BBB). This BBB permeability is a critical factor distinguishing LST from many previous unsuccessful attempts at rabies treatment, such as certain broad-spectrum antivirals that failed to reach therapeutic concentrations in the central nervous system [

16,

17]. The ability of LST to potentially penetrate the CNS is paramount for treating symptomatic rabies, where the virus has already infected neuronal tissue.

The molecular docking results, vividly illustrated in

Figure 2, provide compelling evidence for LST’s potential efficacy. The predicted binding affinity of −9.5 kcal/mol is substantially stronger than that reported for current experimental drugs like Favipiravir in similar in silico studies (e.g., −7.8 kcal/mol as a reference in this study). This high affinity is a direct consequence of the intricate network of interactions observed in the binding pose. The formation of multiple

hydrogen bonds with residues such as Ser687 and the catalytic Asp733 suggests direct involvement in the active site chemistry, potentially interfering with nucleotide binding or phosphodiester bond formation. The

hydrophobic interactions contribute significantly to the overall stability of the ligand-protein complex, effectively anchoring LST within the RdRp active site. This mechanism is indicative of a

non-nucleoside inhibition strategy, which can circumvent resistance mechanisms sometimes associated with nucleoside analogs.

Comparing these findings with previously published articles, the explicit design for CNS penetration and the strong predicted binding to a highly conserved viral enzyme position LST as a leading candidate. While in vitro and in vivo validation are the next critical steps, the comprehensive in silico characterization provides a robust foundation. The successful progression of LST could offer a much-needed therapeutic option for a disease that currently has no effective treatment once clinical symptoms manifest, thereby addressing a significant global health challenge [

4].

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The synthesis described herein was performed exclusively for academic reporting and does not involve any current or pending patents or products related to LyssaStat or its intermediates.

Data Availability Statement

All original data, including raw spectral files (NMR, HRMS) and laboratory notebook entries necessary to reproduce the reported synthetic procedures and confirm the structure of 3-((5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanamide (LyssaStat), are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

The methodology for the synthesis was designed by Prof. Mohammed Kassab. The laboratory work, including all three synthetic steps, purification, and spectroscopic analysis, was performed by Prof. Mohammed Kassab. The manuscript drafting, including the detailed methodology section, was completed by Prof. Mohammed Kassab. All authors have read and approved the final submitted version of the report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies. All materials were sourced from existing laboratory stock.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Rabies. WHO Fact Sheets. (2023).

- Jackson, A. C. Rabies Virus. In: Fields Virology. 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2013).

- Hampson, K. et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 9(4): e0003709. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C. E., Hanlon, C. A., & Hemachudha, T. Rabies re-examined. Lancet, 367(9527): 1943–1957. (2002). [CrossRef]

- Mani, R. S. et al. Rabies Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: An Overview of the Current Guidelines and Challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(18): 11394. (2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report. WHO Technical Report Series No. 1012. (2018).

- Srinivasan, V., Nagarajan, V., & Hemachudha, T. Treatment of Rabies. Clin Infect Dis, 76(1): e21-e28. (2023).

- Johnson, R. T. Pathogenesis of rabies. Rev Infect Dis, 10(Suppl 4): S585–S590. (1988).

- Albertini, A. et al. Structure of the Rabies Virus Ribonucleoprotein Complex. Science, 363(6434): 1500–1504. (2019).

- Tordo, N. & Bourhy, H. Rhabdoviruses: Rabies Virus. In: Encyclopedia of Virology. 3rd ed. Academic Press. (2008).

- Bheemanapally, K. et al. Rabies L protein possesses RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity and requires its N-terminus for transcription. J Virol, 96(21): e00780-22. (2022).

- Hemachudha, T. & Wacharapluesadee, S. Treatment for Rabies. Curr Treat Options Neurol, 12(6): 412–421. (2010).

- Human Rabies Treatment: From Palliation to Promise. Viruses, 16(1): 160. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, R. E. A human case of survival from rabies. Int J Infect Dis, 12(Suppl 1): e61-e63. (2008).

- Hemachudha, T. et al. Failure of therapeutic coma for human rabies. Emerg Infect Dis, 15(4): 509–515. (2009).

- Yamada, K. et al. Favipiravir (T-705) Inhibits Rabies Virus Replication In Vitro and In Vivo. J Infect Dis, 213(8): 1253–1263. (2016).

- Re-evaluating the effect of Favipiravir treatment on rabies virus infection. Antiviral Res, 148: 100–108. (2017).

- Chen, M. et al. Rabies Virus Nucleoprotein: Structure, Function, and Interaction with the Viral Polymerase. J Virol, 95(17): e00624-21. (2021).

- In Silico Identification of Novel Ligand Molecules for Rabies Nucleoprotein using Structure-Based Method. Indian J Pharm Educ Res, 50(2): 298-306. (2016).

- Development and mechanism of action of novel inhibitors of rabies virus replication. Antiviral Res, 222: 105777. (2024).

- Advances in in silico drug discovery for rabies virus: Innovations in ligand identification and therapeutic mechanisms. World Academy of Sciences J, 4(4): 378. (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, D. B. et al. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 3(11): 935–949. (2004). [CrossRef]

- In silico structural elucidation of the rabies RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) toward the identification of potential rabies virus inhibitors. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 39(12): 4478-4489. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, R. K. et al. Rapid development of anti-infectives for viral pathogens: strategies and challenges. Future Virol, 12(5): 315-329. (2017).

- Clofazimine: A Promising Inhibitor of Rabies Virus. Viruses, 13(4): 605. (2021).

- Munjal, S., Bano, N., & Gupta, A. Drug Repurposing Strategy in the Search of New Antiviral Agents Against Rabies Virus Glycoprotein: A Molecular Docking and Dynamics Study. Front Chem, 10: 918712. (2022). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).