Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin Preparation

2.2. Semen Collection, Treatment, and Cryopreservation

2.3. Motion Analyses

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analyses

2.4.1. Membrane and Acrosome Integrities

2.4.2. Membrane Stability and Viability

2.4.3. Calcium Level

2.4.4. Mitochondrial Activity

2.5. Sperm Binding and Interaction with Oviduct Cells

2.6. IVF Experiment

2.7. Experimental Design

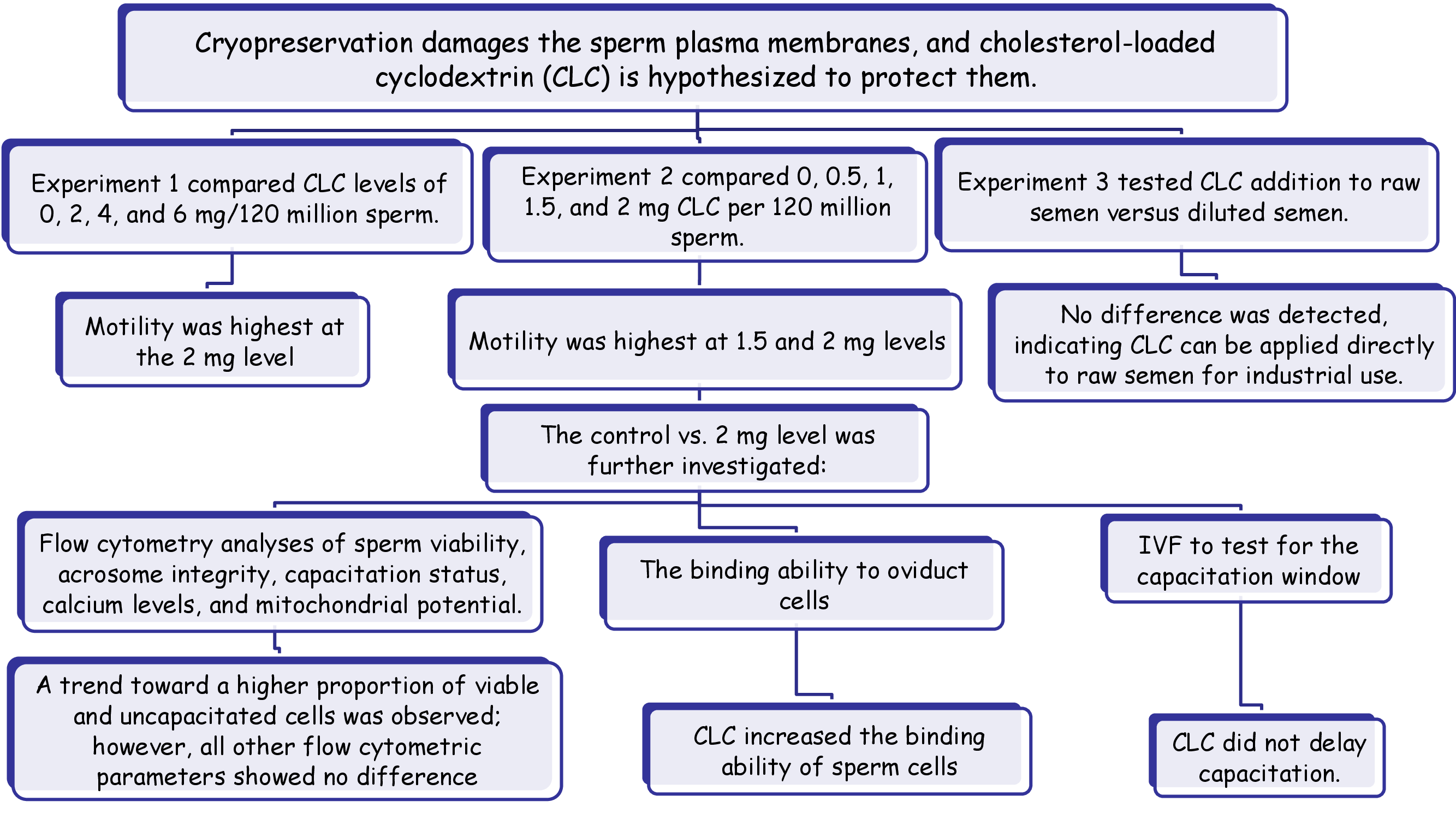

2.7.1. Experiment 1

2.7.2. Experiment 2

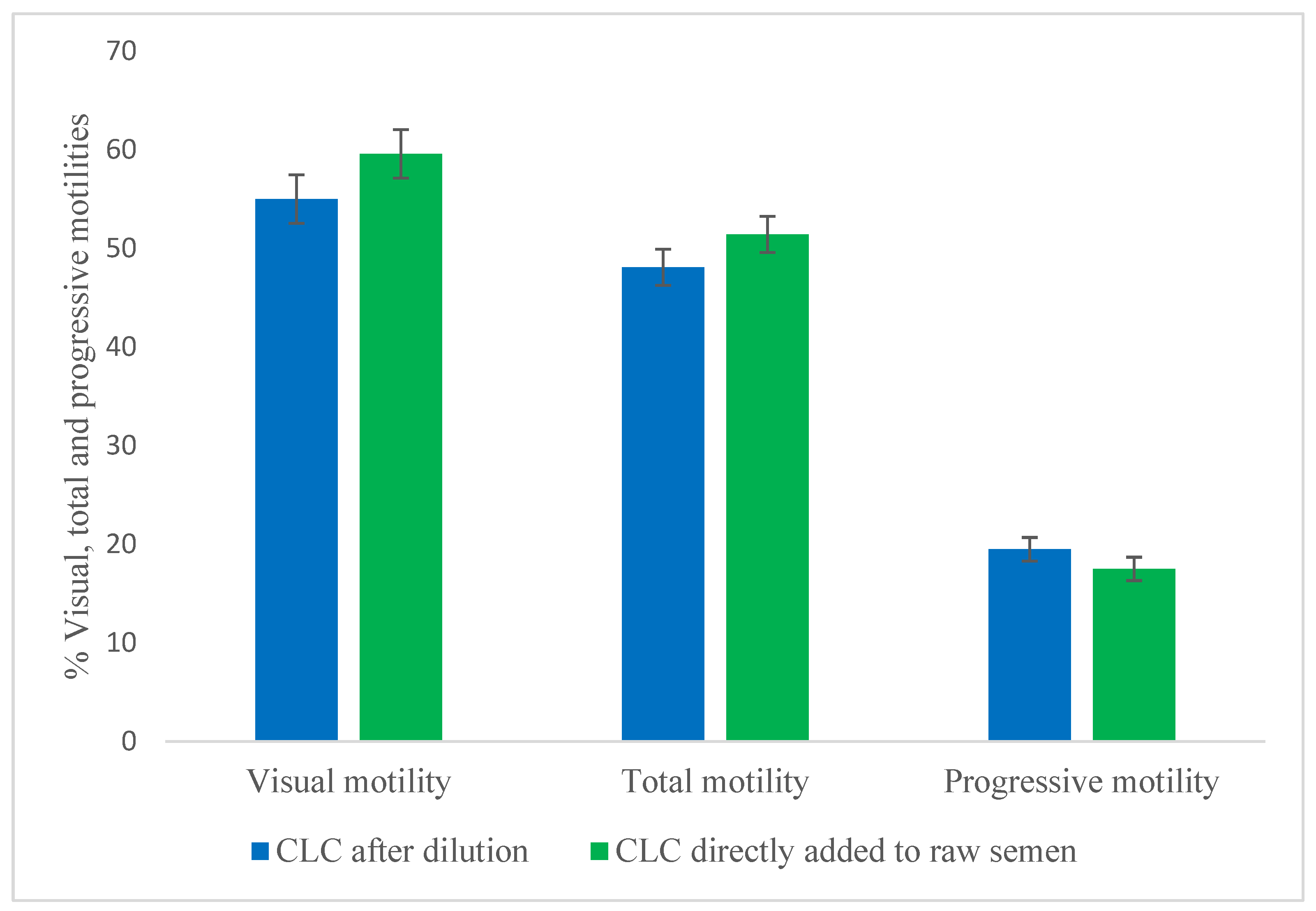

2.7.3. Experiment 3

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

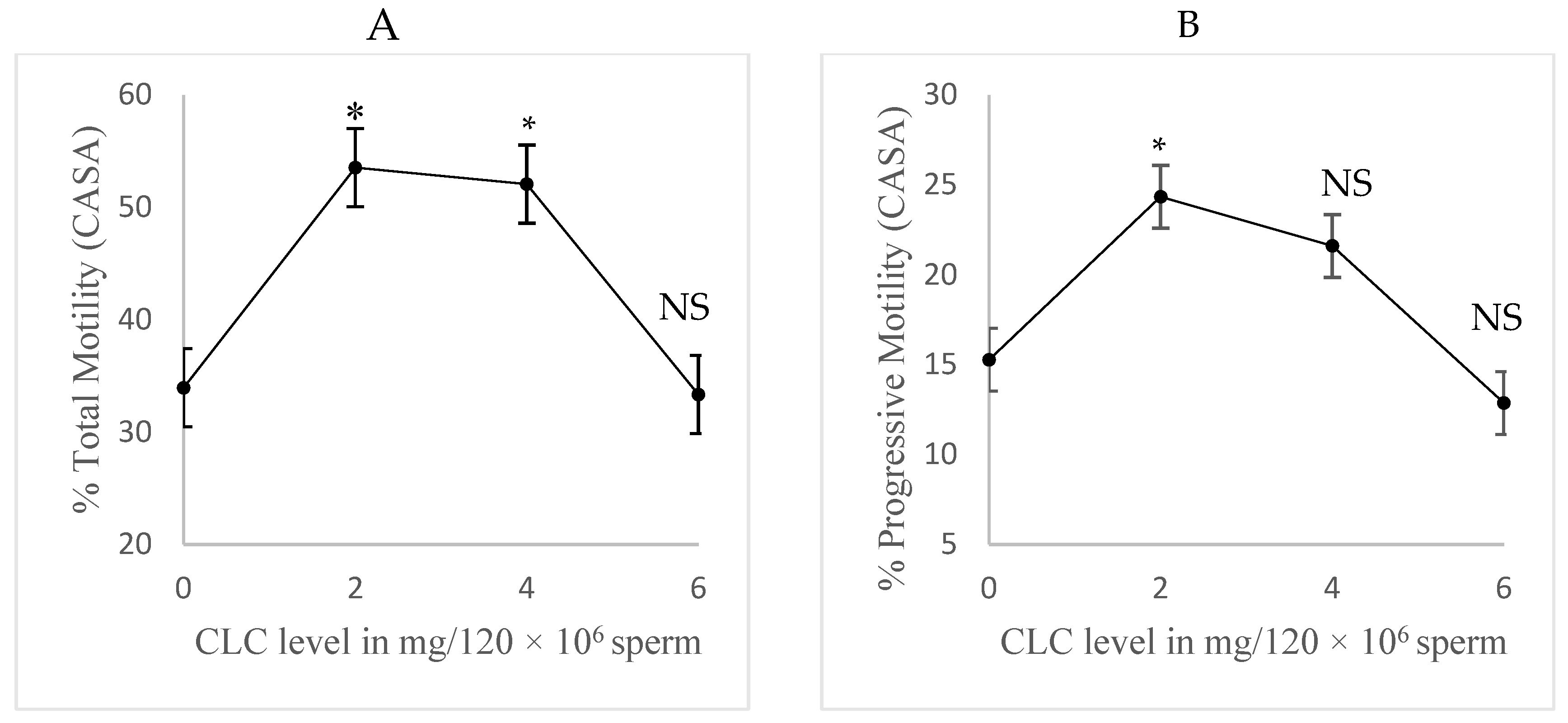

3.1. Experiment 1

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Motion Analyses

| CLC-level (mg/120 × 106 sperm cells) | Total Motility via CASA (%) | Progressive Motility via CASA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 22.2 ± 2.8 | 5.2 ± 1.1 |

| 0.5 | 29.6 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 1.1 |

| 1 | 34.7* ± 2.8 | 8.4 ± 1.1 |

| 1.5 | 35.7* ± 2.8 | 10.4* ± 1.1 |

| 2 | 36.1* ± 2.8 | 9.2* ± 1.1 |

| Post-thaw time (min.) | Total Motility via CASA (%) | Progressive Motility via CASA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 43 ± 2.1 | 12 ± 0.8 |

| 30 | 37.4** ± 2.5 | 10.2** ± 1.1 |

| 60 | 26.9** ± 2.1 | 6.8** ± 0.8 |

| 120 | 19.5** ± 2.1 | 3.6** ± 0.6 |

3.2.2. Flow Cytometric Analyses

3.2.3. Oviduct Experiment

3.2.4. IVF Experiment

3.3. Experiment 3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leahy, T.; Gadella, B.M. Sperm Surface Changes and Physiological Consequences Induced by Sperm Handling and Storage. Reproduction 2011, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkavukcu, S.; Erdemli, E.; Isik, A.; Oztuna, D.; Karahuseyinoglu, S. Effects of Cryopreservation on Sperm Parameters and Ultrastructural Morphology of Human Spermatozoa. J Assist Reprod Genet 2008, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieme, H.; Oldenhof, H.; Wolkers, W.F. Sperm Membrane Behaviour during Cooling and Cryopreservation. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2015, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugur, M.R.; Saber Abdelrahman, A.; Evans, H.C.; Gilmore, A.A.; Hitit, M.; Arifiantini, R.I.; Purwantara, B.; Kaya, A.; Memili, E. Advances in Cryopreservation of Bull Sperm. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F. The Causes of Reduced Fertility with Cryopreserved Semen. In Proceedings of the Animal Reproduction Science; 2000; Vol. 60–61. [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F. Recent Developments and Concepts in the Cryopreservation of Spermatozoa and the Assessment of Their Post-Thawing Function. Reprod Fertil Dev 1995, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, J.; Morrier, A.; Cormier, N. Semen Cryopreservation: Successes and Persistent Problems in Farm Species. Can J Anim Sci 2003, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernecic, N.C.; Gadella, B.M.; Leahy, T.; de Graaf, S.P. Novel Methods to Detect Capacitation-Related Changes in Spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2019, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.D.; Meyers, S.A.; Ball, B.A. Capacitation-like Changes in Equine Spermatozoa Following Cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2006, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Cao, Z.; Liu, H.; Khan, A.; Rahman, S.U.; Khan, M.Z.; Sathanawongs, A.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Cryopreservation on Spermatozoa Freeze-Thawed Traits and Relevance OMICS to Assess Sperm Cryo-Tolerance in Farm Animals. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, V.M.; Leclerc, P.; Bailey, J.L. Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin Increases the Cholesterol Content of Goat Sperm to Improve Cold and Osmotic Resistance and Maintain Sperm Function after Cryopreservation. Biol Reprod 2016, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, F.; Ďuračka, M.; Baňas, Š.; Lukáč, N.; Tvrdá, E. Biological Relevance of Free Radicals in the Process of Physiological Capacitation and Cryocapacitation. Oxygen 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, F.; Fialková, V.; Žiarovská, J.; Ďuračka, M.; Lukáč, N.; Tvrdá, E. In Vitro versus Cryo-Induced Capacitation of Bovine Spermatozoa, Part 2: Changes in the Expression Patterns of Selected Transmembrane Channels and Protein Kinase A. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfalewicz, B.; Dietrich, M.A.; Mostek, A.; Partyka, A.; Bielas, W.; Niżański, W.; Ciereszko, A. Analysis of Bull (Bos Taurus) Seminal Vesicle Fluid Proteome in Relation to Seminal Plasma Proteome. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, F.; Mohammadi-Sangcheshmeh, A.; Ďuračka, M.; Lukáč, N.; Tvrdá, E. In Vitro versus Cryo-Induced Capacitation of Bovine Spermatozoa, Part 1: Structural, Functional, and Oxidative Similarities and Differences. PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, J.J. Bovine in Vitro Fertilization: In Vitro Oocyte Maturation and Sperm Capacitation with Heparin. Theriogenology 2014, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abah, K.O.; Fontbonne, A.; Partyka, A.; Nizanski, W. Effect of Male Age on Semen Quality in Domestic Animals: Potential for Advanced Functional and Translational Research? Vet Res Commun 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.P.; DeJarnette, J.M. Impact of Genomic Selection of AI Dairy Sires on Their Likely Utilization and Methods to Estimate Fertility: A Paradigm Shift. Theriogenology 2012, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.M.; Kelly, A.K.; O’Meara, C.; Eivers, B.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, S. Influence of Bull Age, Ejaculate Number, and Season of Collection on Semen Production and Sperm Motility Parameters in Holstein Friesian Bulls in a Commercial Artificial Insemination Centre. J Anim Sci 2018, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJarnette, J.M.; Marshall, C.E.; Lenz, R.W.; Monke, D.R.; Ayars, W.H.; Sattler, C.G. Sustaining the Fertility of Artificially Inseminated Dairy Cattle: The Role of the Artificial Insemination Industry. J Dairy Sci 2004, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocé, E.; Blanch, E.; Tomás, C.; Graham, J.K. Use of Cholesterol in Sperm Cryopreservation: Present Moment and Perspectives to Future. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2010, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, P.H.; Graham, J.K. Effect of Adding Cholesterol to Bull Sperm Membranes on Sperm Capacitation, the Acrosome Reaction, and Fertility. Biol Reprod 2004, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, F.P.; Lisboa, F.P.; Hartwig, F.P.; Monteiro, G.A.; Maziero, R.R.D.; Freitas-Dell’Aqua, C.P.; Alvarenga, M.A.; Papa, F.O.; Dell’Aqua, J.A. Use of Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin: An Alternative for Bad Cooler Stallions. Theriogenology 2014, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, P.H.; Graham, J.K. Effect of Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin on the Cryosurvival of Bull Sperm. Cryobiology 2004, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligocka, Z.; Partyka, A.; Schäfer-Somi, S.; Mucha, A.; Niżański, W. Does Better Post-Thaw Motility of Dog Sperm Frozen with CLC Mean Better Zona Pellucida Binding Ability? Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Rosa, J.; de Paula Freitas Dell’Aqua, C.; de Souza, F.F.; Missassi, G.; Kempinas, W.D.G. Multiple Flow Cytometry Analysis for Assessing Human Sperm Functional Characteristics. Reproductive Toxicology 2023, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ferrusola, C.; Anel-López, L.; Martín-Muñoz, P.; Ortíz-Rodríguez, J.M.; Gil, M.C.; Alvarez, M.; De Paz, P.; Ezquerra, L.J.; Masot, A.J.; Redondo, E.; et al. Computational Flow Cytometry Reveals That Cryopreservation Induces Spermptosis but Subpopulations of Spermatozoa May Experience Capacitation-like Changes. Reproduction 2017, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, M.; Kroetsch, T.; Boswall, L. Cryopreservation of Bull Semen Shipped Overnight and Its Effect on Post-Thaw Sperm Motility, Plasma Membrane Integrity, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Normal Acrosomes. Anim Reprod Sci 2011, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanc, M.E.; Gungor, S.; Ozturk, C.; Korkmaz, F.; Bastan, I.; Cil, B. Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin plus Trehalose Improves Quality of Frozen-Thawed Ram Sperm. Vet Med (Praha) 2019, 64, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallap, T.; Nagy, S.; Jaakma, Ü.; Johannisson, A.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Usefulness of a Triple Fluorochrome Combination Merocyanine 540/Yo-Pro 1/Hoechst 33342 in Assessing Membrane Stability of Viable Frozen-Thawed Spermatozoa from Estonian Holstein AI Bulls. Theriogenology 2006, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, F.J.; Saravia, F.; Johannisson, A.; Walgren, M.; Rodríguez-Martínez, H. A New and Simple Method to Evaluate Early Membrane Changes in Frozen-Thawed Boar Spermatozoa. Int J Androl 2005, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckler, D.; Stout, T.A.E.; Durandt, C.; Nöthling, J.O. Validation of Merocyanine 540 Staining as a Technique for Assessing Capacitation-Related Membrane Destabilization of Fresh Dog Sperm. Theriogenology 2015, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.A.P.; Ashworth, P.J.C.; Miller, N.G.A. Bicarbonate/CO2, an Effector of Capacitation, Induces a Rapid and Reversible Change in the Lipid Architecture of Boar Sperm Plasma Membranes. Mol Reprod Dev 1996, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, H.D.; Welch, G.R. Effects of Hypothermic Liquid Storage and Cryopreservation on Basal and Induced Plasma Membrane Phospholipid Disorder and Acrosome Exocytosis in Boar Spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, J.J.; Susko-Parrish, J.L.; Graham, J.K. In Vitro Capacitation of Bovine Spermatozoa: Role of Intracellular Calcium. Theriogenology 1999, 51, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spizziri, B.E.; Fox, M.H.; Bruemmer, J.E.; Squires, E.L.; Graham, J.K. Cholesterol-Loaded-Cyclodextrins and Fertility Potential of Stallions Spermatozoa. Anim Reprod Sci 2010, 118, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.S. Regulation of Sperm Storage and Movement in the Mammalian Oviduct. International Journal of Developmental Biology 2008, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, J.E.; Samper, J.C.; Jones, A.E.; Oliver, S.A.; Burnett, K.M.; Wright, R.W. In Vitro Interactions of Cryopreserved Stallion Spermatozoa and Oviduct (Uterine Tube) Epithelial Cells or Their Secretory Products. Anim Reprod Sci 1999, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, A.; Duncan, A.E.; Watson, P.F.; Holt, W. V. Sperm-Oviduct Interaction: Induction of Capacitation and Preferential Binding of Uncapacitated Spermatozoa to Oviductal Epithelial Cells in Porcine Species. Biol Reprod 1999, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, J.J.; Susko-Parrish, J.; Winer, M.A.; First, N.L. Capacitation of Bovine Sperm by Heparin. Biol Reprod 1988, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, K.; Kang, S.S.; Huang, W.; Yanagawa, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagano, M. Estimation of the Optimal Timing of Fertilization for Embryo Development of in Vitro-Matured Bovine Oocytes Based on the Times of Nuclear Maturation and Sperm Penetration. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2014, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocé, E.; Graham, J.K. Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrins Added to Fresh Bull Ejaculates Improve Sperm Cryosurvival. J Anim Sci 2006, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.S.; Rozeboom, K.J.; Parrish, J.J. Using Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin to Improve Cryo-Survivability and Reduce Capacitation-Like Changes in Gender-Ablated Jersey Semen. Animals 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, M.; Rajapaksha, K.; Boswall, L. Egg Yolk-Free Cryopreservation of Bull Semen. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, G.M.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Martín-Hidalgo, D.; Ritagliati, C.; Puga Molina, L.C.; Romarowski, A.; Balestrini, P.A.; Schiavi-Ehrenhaus, L.J.; Gilio, N.; Krapf, D.; et al. Only a Subpopulation of Mouse Sperm Displays a Rapid Increase in Intracellular Calcium during Capacitation. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravance, C.G.; Garner, D.L.; Miller, M.G.; Berger, T. Fluorescent Probes and Flow Cytometry to Assess Rat Sperm Integrity and Mitochondrial Function. Reproductive Toxicology 2000, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.S.; Moraes, J.G.N.; Patterson, D.J.; Smith, M.F.; Behura, S.K.; Poock, S.; Spencer, T.E. Influences of Sire Conception Rate on Pregnancy Establishment in Dairy Cattle. Biol Reprod 2018, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Sanchez, J.F.; Preis, K.; Seidel, G.E. Metabolic Regulation of In-Vitro-Produced Bovine Embryos. I. Effects of Metabolic Regulators at Different Glucose Concentrations with Embryos Produced by Semen from Different Bulls. Reprod Fertil Dev 2006, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Lamb, D.J. The Sperm Penetration Assay for the Assessment of Fertilization Capacity. Methods in Molecular Biology 2013, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Jiang, L.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Li, K.; Sheng, H.Q.; Ni, Y.; Lu, J.X.; Xu, W.X.; Zhang, S.Y.; Shi, Q.X. CFTR Is Essential for Sperm Fertilizing Capacity and Is Correlated with Sperm Quality in Humans. Human Reproduction 2010, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, Y.; Abe, R.; Geshi, M.; Matoba, S.; Nagai, T.; Somfai, T. Sex-Sorting of Spermatozoa Affects Developmental Competence of in Vitro Fertilized Oocytes in a Bull-Dependent Manner. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2016, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkwart, K.; Schneider, F.; Lukoseviciute, M.; Sauka-Spengler, T.; Lyman, E.; Eggeling, C.; Sezgin, E. Nanoscale Dynamics of Cholesterol in the Cell Membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2019, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöhnl, M.; Trollmann, M.F.W.; Böckmann, R.A. Nonuniversal Impact of Cholesterol on Membranes Mobility, Curvature Sensing and Elasticity. Nat Commun 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.Q.; Jin, Q.G.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Luo, X.T.; Han, Y.; Cheng, M.M.; Qu, X.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Jin, Y. Effects of Partially Replacing Glycerol with Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin on Protamine Deficiency, in Vitro Capacitation and Fertilization Ability of Frozen–Thawed Yanbian Yellow Cattle Sperm. Theriogenology 2022, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.S. Impact of Some Cryoprotectant Agents on Freezing Ability and Fertility of Rabbit Buck Spermatozoa. MSc., Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University: Cairo, 2014.

- Davis, B.K. Timing of Fertilization in Mammals: Sperm Cholesterol/Phospholipid Ratio as a Determinant of the Capacitation Interval. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1981, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocé, E.; Tomás, C.; Blanch, E.; Graham, J.K. Effect of Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrins on Bull and Goat Sperm Processed with Fast or Slow Cryopreservation Protocols. Animal 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernecic, N.C.; Zhang, M.; Gadella, B.M.; Brouwers, J.F.H.M.; Jansen, J.W.A.; Arkesteijn, G.J.A.; de Graaf, S.P.; Leahy, T. BODIPY-Cholesterol Can Be Reliably Used to Monitor Cholesterol Efflux from Capacitating Mammalian Spermatozoa. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batissaco, L.; de Arruda, R.P.; Alves, M.B.R.; Torres, M.A.; Lemes, K.M.; Prado-Filho, R.R.; de Almeida, T.G.; de Andrade, A.F.C.; Celeghini, E.C.C. Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin Is Efficient in Preserving Sperm Quality of Cryopreserved Ram Semen with Low Freezability. Reprod Biol 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVelle, G.; Cairo, B.; Barfield, J.P. Effect of Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin Treatment of Bovine Sperm on Capacitation Timing. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.H.; Vasconcelos, A.B.; Souza, F.A.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Silva, M.X.; Varago, F.C.; Lagares, M.A. Cholesterol Addition Protects Membrane Intactness during Cryopreservation of Stallion Sperm. Anim Reprod Sci 2010, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Leoni, V.; Caccia, C.; Berdeaux, A.; Morin, D. Cardioprotection by the TSPO Ligand 4′-Chlorodiazepam Is Associated with Inhibition of Mitochondrial Accumulation of Cholesterol at Reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res 2013, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Gong, J.S.; Ko, M.; Garver, W.S.; Yanagisawa, K.; Michikawa, M. Altered Cholesterol Metabolism in Niemann-Pick Type C1 Mouse Brains Affects Mitochondrial Function. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Kennedy, B.E.; Karten, B. Mitochondrial Cholesterol: Mechanisms of Import and Effects on Mitochondrial Function. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2016, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, S.A. Possible Mechanisms of Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrin Action on Sperm during Cryopreservation. Anim Reprod Sci 2018, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Cassina, A.; Irigoyen, P.; Ford, M.; Pietroroia, S.; Peramsetty, N.; Radi, R.; Santi, C.M.; Sapiro, R. Increased Mitochondrial Activity upon CatSper Channel Activation Is Required for Mouse Sperm Capacitation. Redox Biol 2021, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccagli, M.M.; Gómez-Elías, M.D.; Herzfeld, J.D.; Marín-Briggiler, C.I.; Cuasnicú, P.S.; Cohen, D.J.; Da Ros, V.G. Capacitation-Induced Mitochondrial Activity Is Required for Sperm Fertilizing Ability in Mice by Modulating Hyperactivation. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.M.; Romarowski, A.; Gervasi, M.G.; Navarrete, F.; Balbach, M.; Salicioni, A.M.; Levin, L.R.; Buck, J.; Visconti, P.E. Capacitation Increases Glucose Consumption in Murine Sperm. Mol Reprod Dev 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansegundo, E.; Tourmente, M.; Roldan, E.R.S. Energy Metabolism and Hyperactivation of Spermatozoa from Three Mouse Species under Capacitating Conditions. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrageta, D.F.; Guerra-Carvalho, B.; Sousa, M.; Barros, A.; Oliveira, P.F.; Monteiro, M.P.; Alves, M.G. Mitochondrial Activation and Reactive Oxygen-Species Overproduction during Sperm Capacitation Are Independent of Glucose Stimuli. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, J.; Lin, H.; Fritch, M.R.; Tuan, R.S. Influence of Cholesterol/Caveolin-1/Caveolae Homeostasis on Membrane Properties and Substrate Adhesion Characteristics of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás, C.; Blanch, E.; Fazeli, A.; Mocé, E. Effect of a Pre-Freezing Treatment with Cholesterol-Loaded Cyclodextrins on Boar Sperm Longevity, Capacitation Dynamics, Ability to Adhere to Porcine Oviductal Epithelial Cells in Vitro and DNA Fragmentation Dynamics. Reprod Fertil Dev 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, C. Bovine Sperm Interaction with Oviductal Epithelial Cells. Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1999.

- Petrunkina, A.M.; Waberski, D.; Günzel-Apel, A.R.; Töpfer-Petersen, E. Determinants of Sperm Quality and Fertility in Domestic Species. Reproduction 2007, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Role of the Oviduct in Sperm Capacitation. Theriogenology 2007, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwanath, R.; Moreno, J.F. Review: Semen Sexing - Current State of the Art with Emphasis on Bovine Species. Animal 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Toni, L.; Sabovic, I.; De Filippis, V.; Acquasaliente, L.; Peterle, D.; Guidolin, D.; Sut, S.; Di Nisio, A.; Foresta, C.; Garolla, A. Sperm Cholesterol Content Modifies Sperm Function and Trpv1-mediated Sperm Migration. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CLC-level (mg/120 × 106 sperm cells) | Subpopulation with intact membranes and acrosomes (%) | Subpopulation with viable un-capacitated sperm cells (%) | Mitochondrial potential (ratio of JC1 orange to green florescence) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 20.9 ± 2.9 | 20.4 ± 3.7 | 0.99 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | 30.5 ± 2.9 | 32.8 ± 3.7 | 0.91 ± 0.04 |

| CLC level (mg/67x106 sperm cells) | No Ionomycin | Ionomycin | overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 569 ± 129 | 1476** ± 129 | 1022 ± 91 |

| 2 | 622 ± 129 | 1491** ± 129 | 1056 ± 91 |

| Overall | 595 ± 105 | 1484 ± 105 |

| Coincubation time (h) | CLC-level (mg/120 × 106 sperm cells) | Number of viable bound sperm cells/ area of 1.65x106 µm2 oviduct cells |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0 | 209 ± 15 |

| 2 | 424*** ± 15 | |

| 3 | 0 | 118 ± 15 |

| 2 | 267*** ± 15 | |

| 7 | 0 | 70 ± 15 |

| 2 | 127* ± 15 | |

| 20 | 0 | 28 ± 15 |

| 2 | 63 ± 15 |

| Coincubation time (h) | CLC-level (mg/120 × 106 sperm cells) | Penetration (%) | Overall | Pronuclei formation/penetrated oocytes (%) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0 | 72 ± 4 | 72 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 |

| 2 | 73 ± 4 | 2 ± 2 | |||

| 8 | 0 | 73 ± 3 | 77 ± 2 | 53 ± 7 | 47*** ± 5 |

| 2 | 81 ± 3 | 41 ± 7 | |||

| 12 | 0 | 81 ± 4 | 82* ± 2 | 66 ± 7 | 69*** ± 5 |

| 2 | 83 ± 4 | 72 ± 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).