Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Preparation

- ○

- Temperature range: 25–323 K (varied per substance to cover subcritical, critical, and supercritical regimes).

- ○

- Pressure range: 0.001–300 MPa (encompassing low-pressure ideal-like behavior to high-pressure compression).

- ○

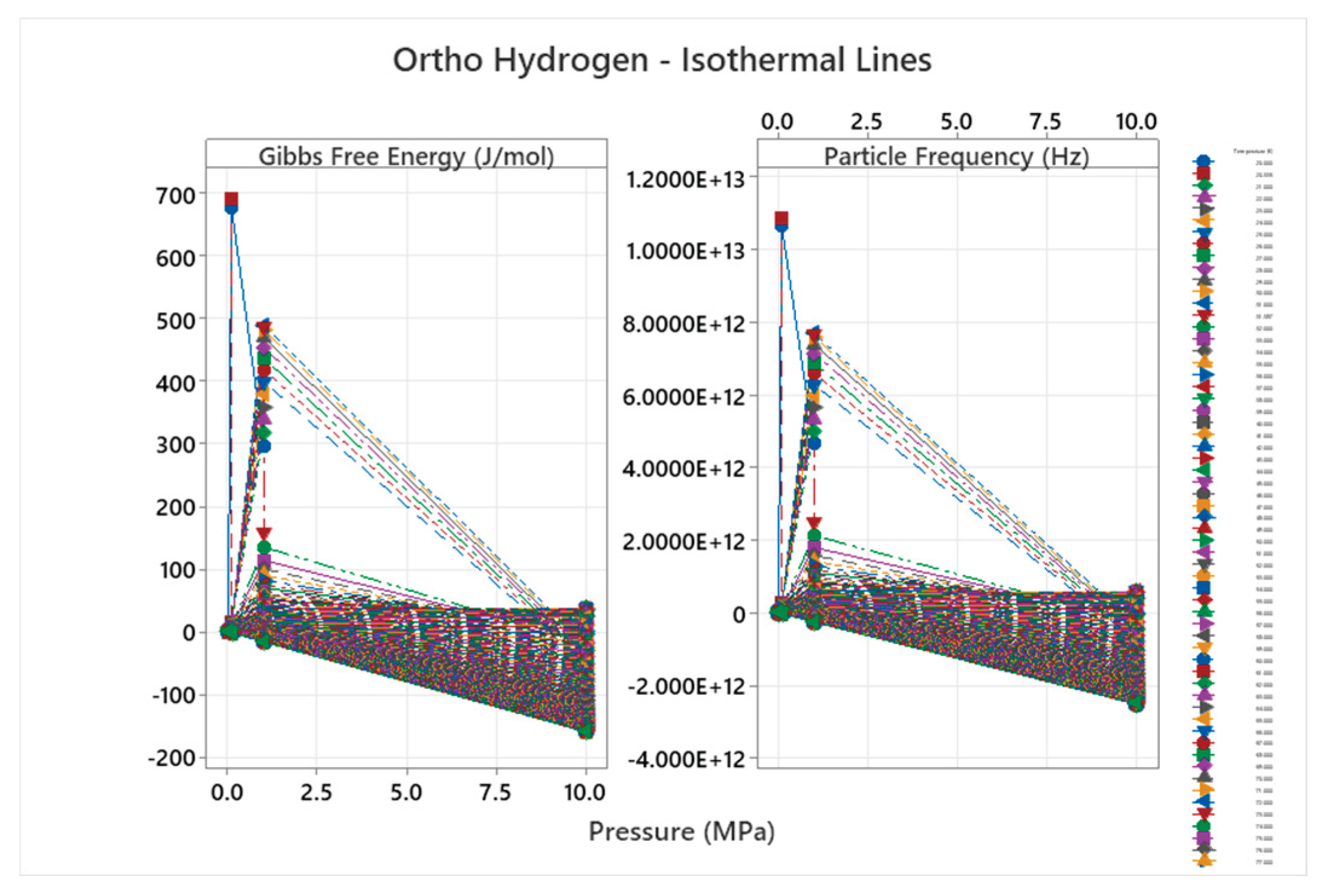

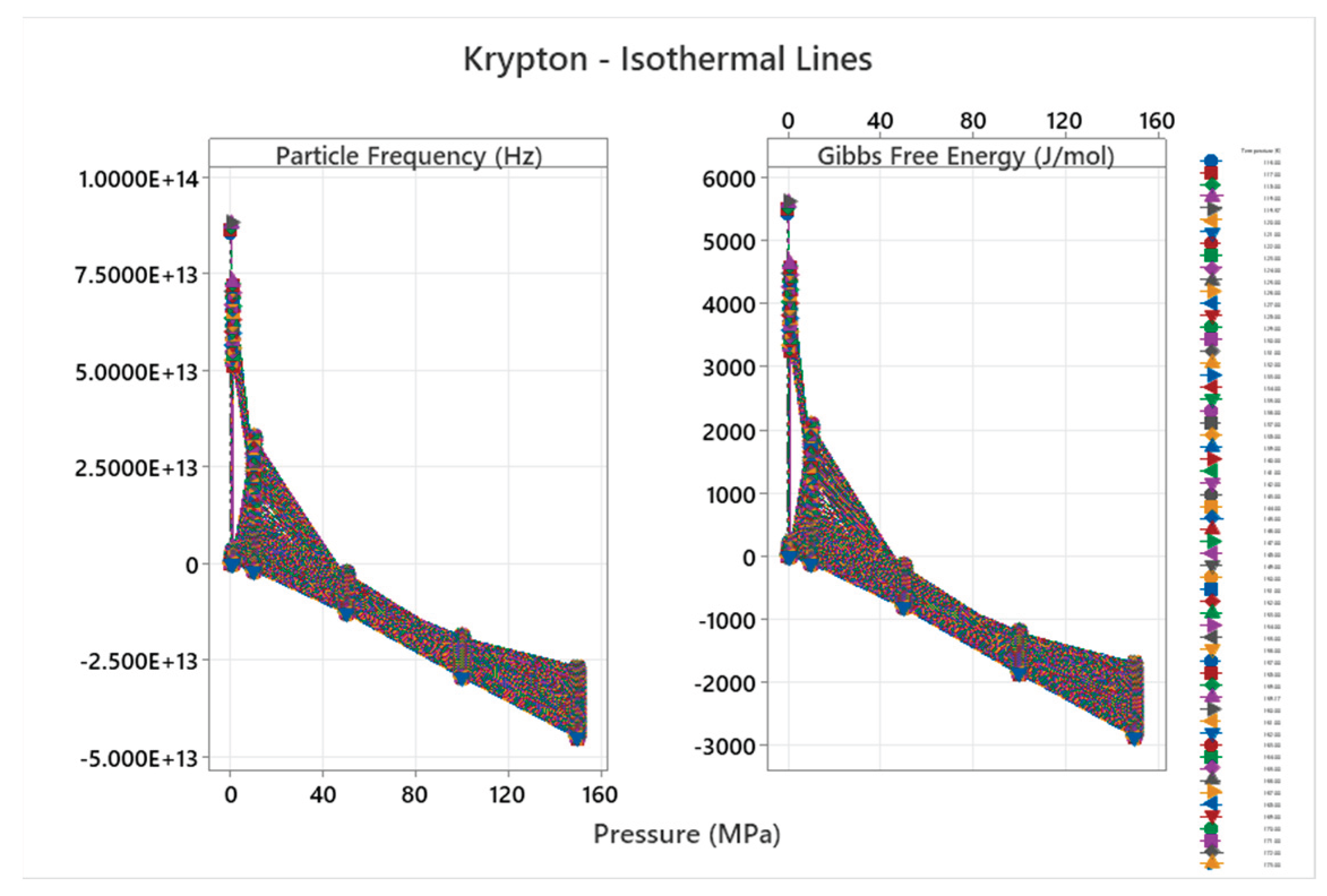

- Key properties extracted: T (K), P (MPa), ρ (kg/m³), (m³/mol), Z, fugacity (MPa), and G (J/mol, computed as absolute via G = -RT ln Z).

- ○

- ○

- Data from NIST REFPROP or equivalent correlations, focusing on liquid-vapor equilibria (VLE) and supercritical branches.

- ○

- Data were downloaded as CSV files from NIST queries (e.g., for Neon: T from 25–275 K in 1 K steps, P from 0.001–100 MPa in logarithmic increments).

- ○

- Sheets were organized with columns for T (K), P (MPa), ρ (kg/m³), specific volume (m³/kg), (m³/mol), Z, fugacity (MPa), exp(G/RT), and G (J/mol).

- ○

- For mixtures, composite prime was used to generalize equations.

- ○

- No preprocessing (e.g., smoothing) was applied to raw data to preserve empirical integrity.

- ○

- All data are publicly accessible via NIST WebBook searches with the specified ranges, ensuring full reproducibility.

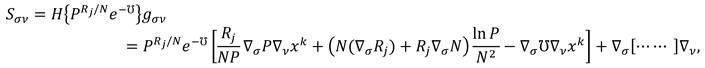

3.2. Theoretical Models and Equations

- ○

- ○

- ○

- ○

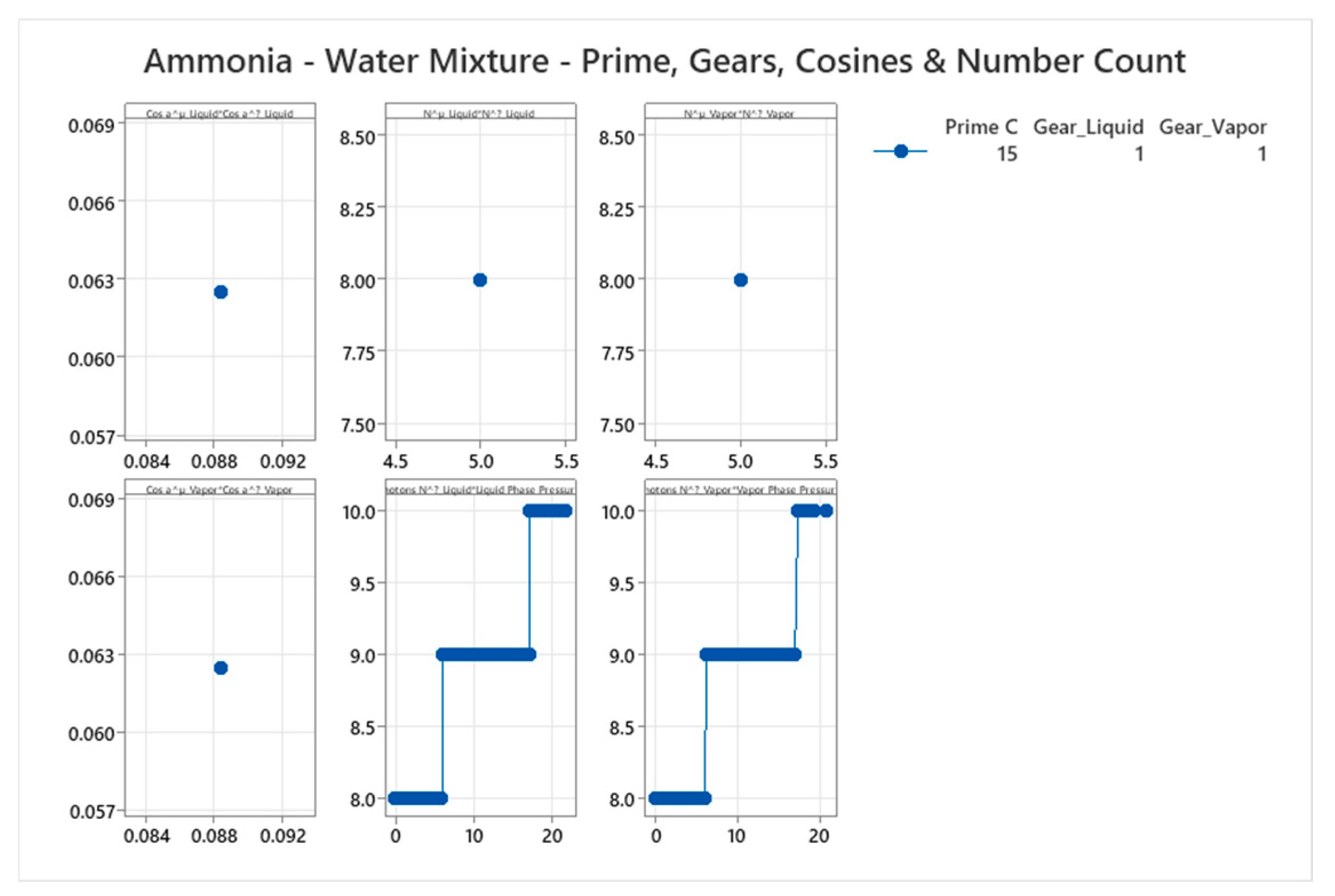

- For binary mixtures (e.g., NH₃-H₂O), (e.g., 15 for 3 and 5), enforcing joint indivisibility. Weighted averages for and , with phase shift emergent from interactions . UEOS for mixtures: weighted interference terms, deriving , unifying non-idealities (azeotropes via ∙sign).

3.3. Computational Methods and Simulations

- ○

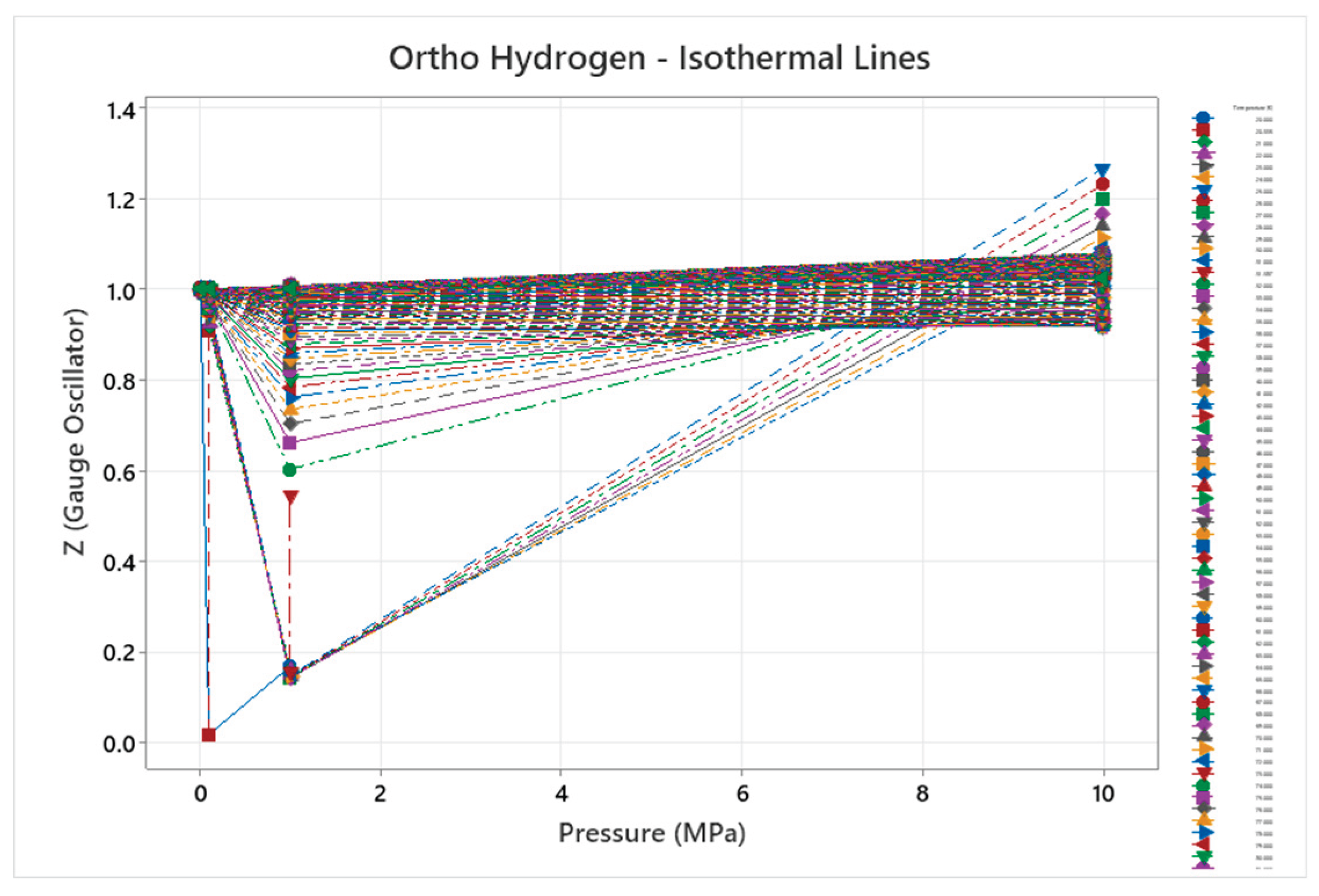

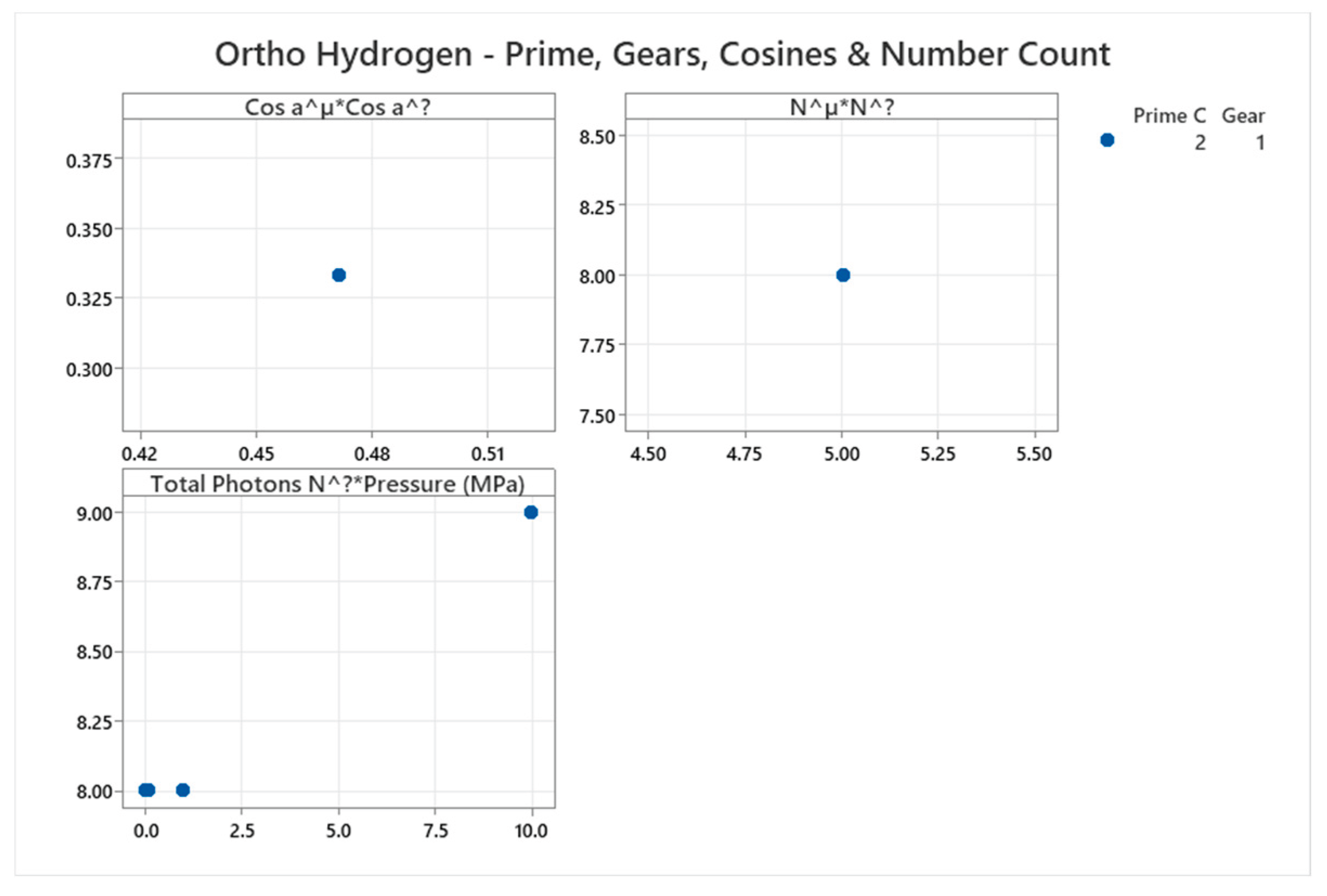

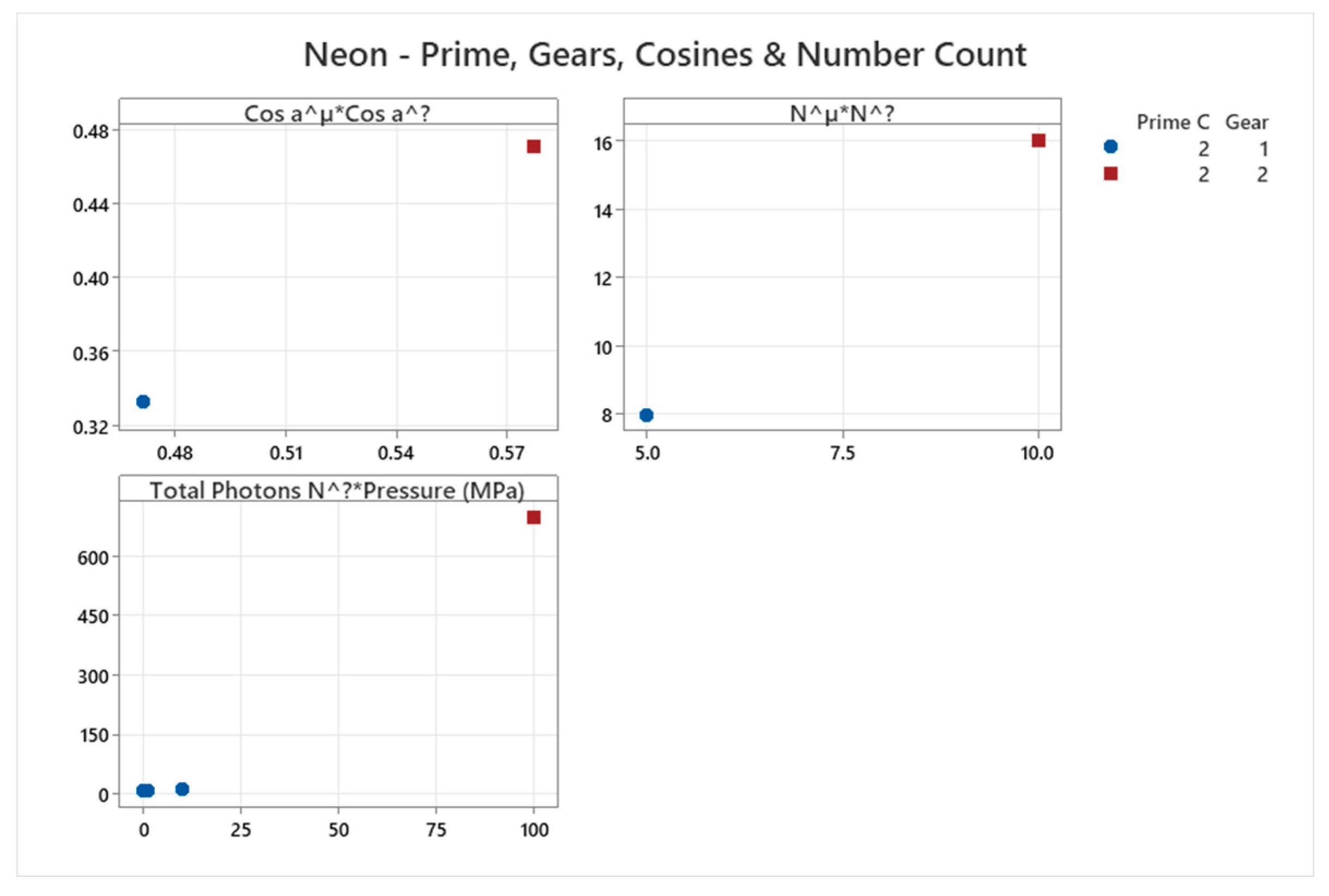

- Triad parameters (Gear, cos α, , , = - ).

- ○

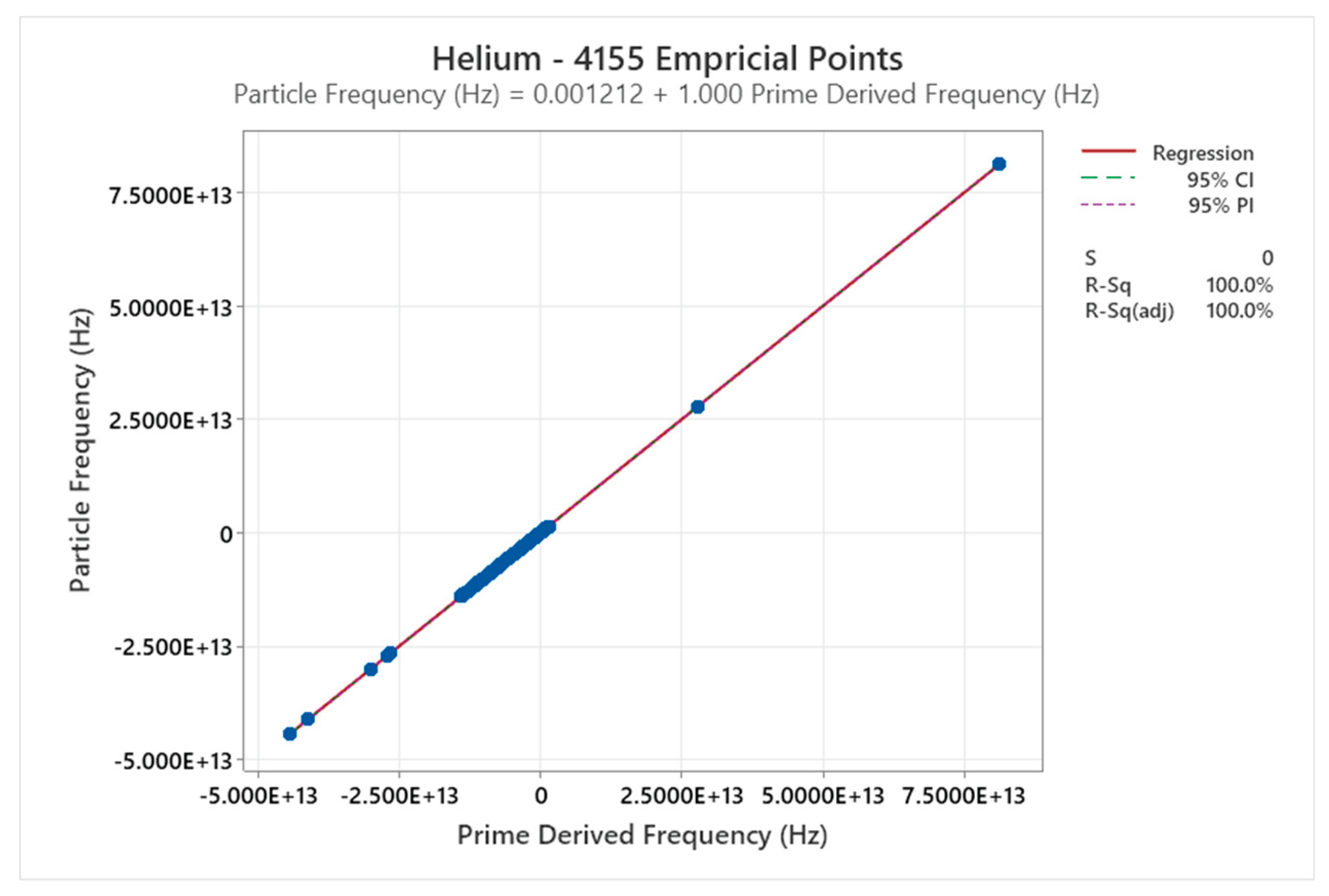

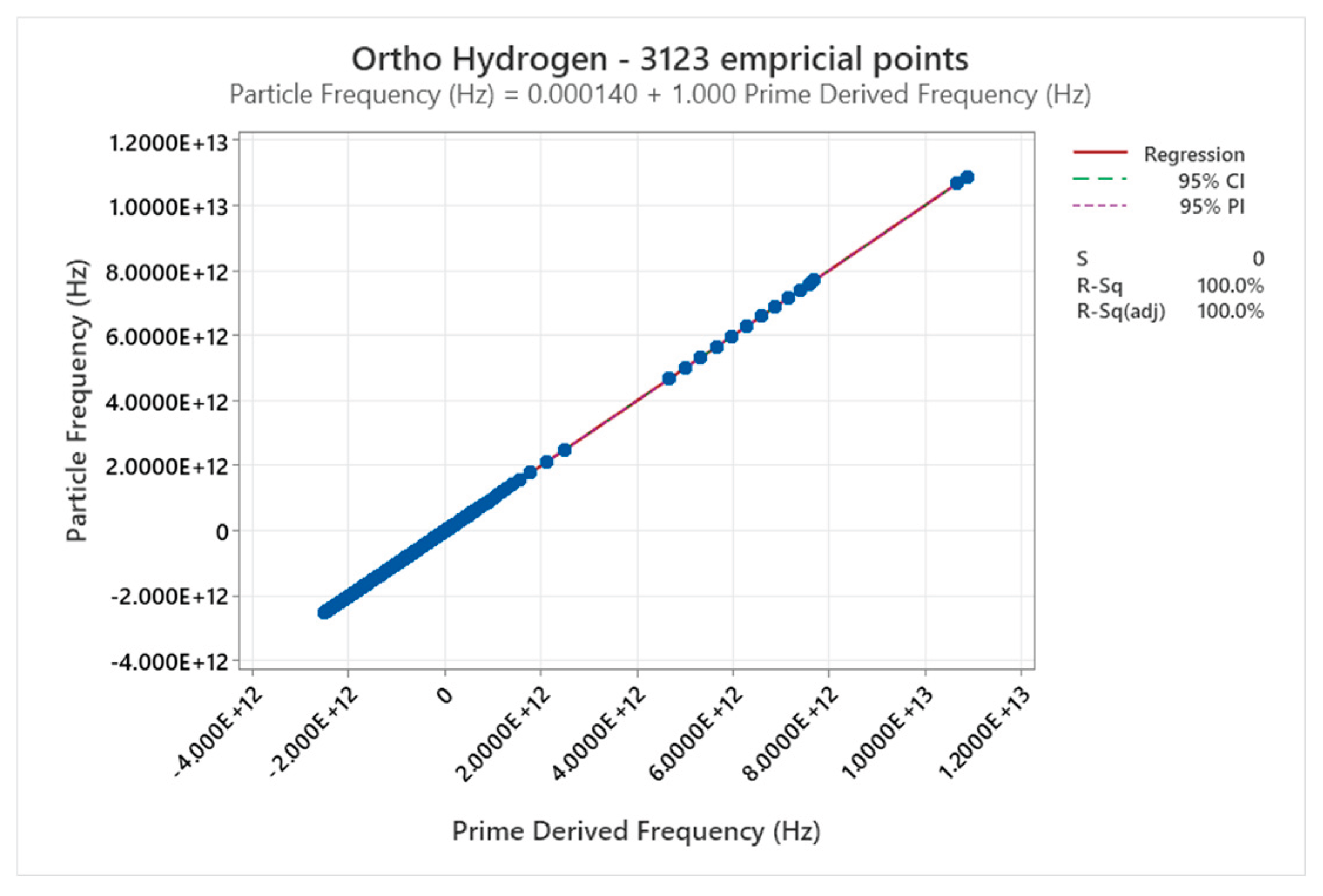

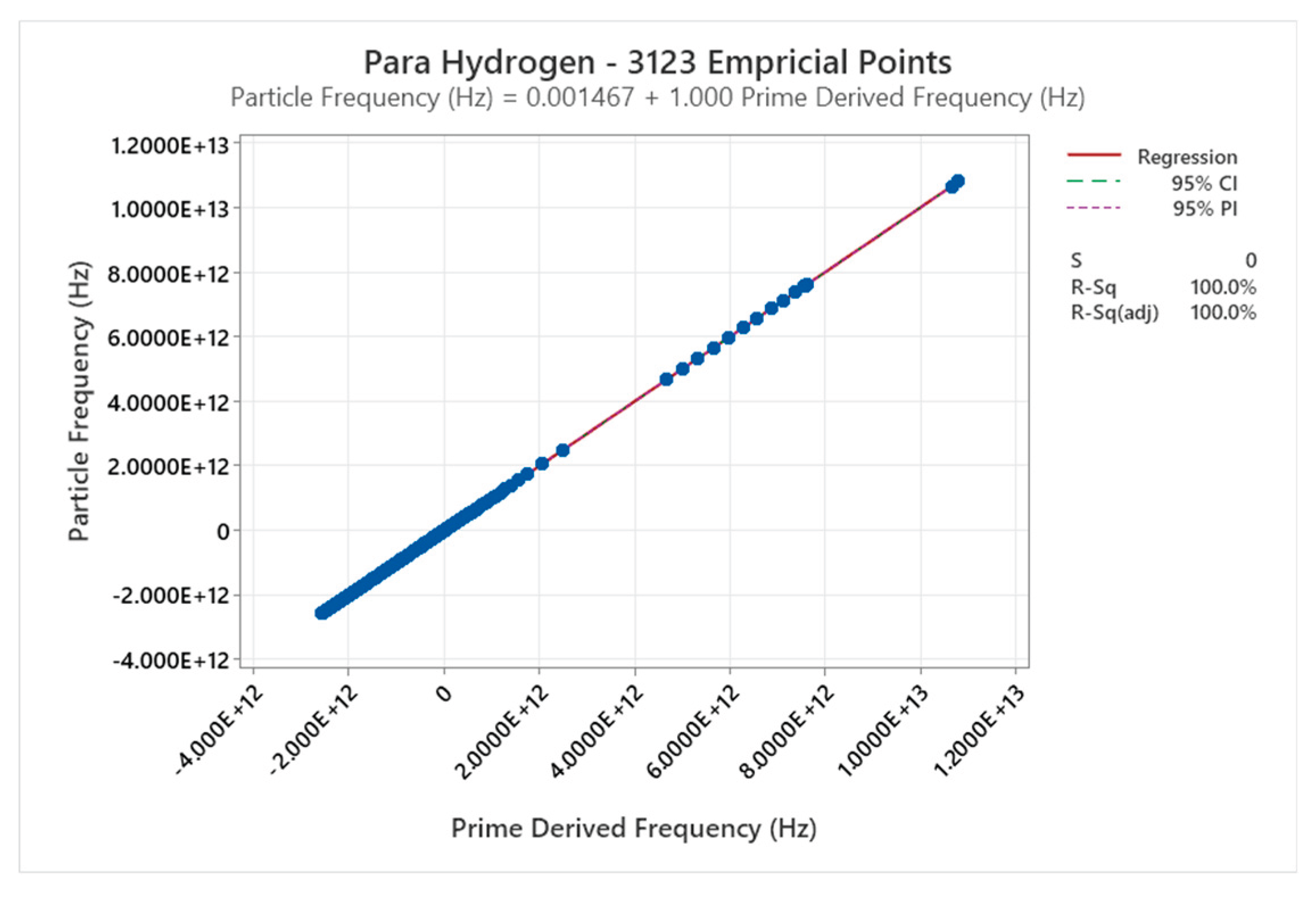

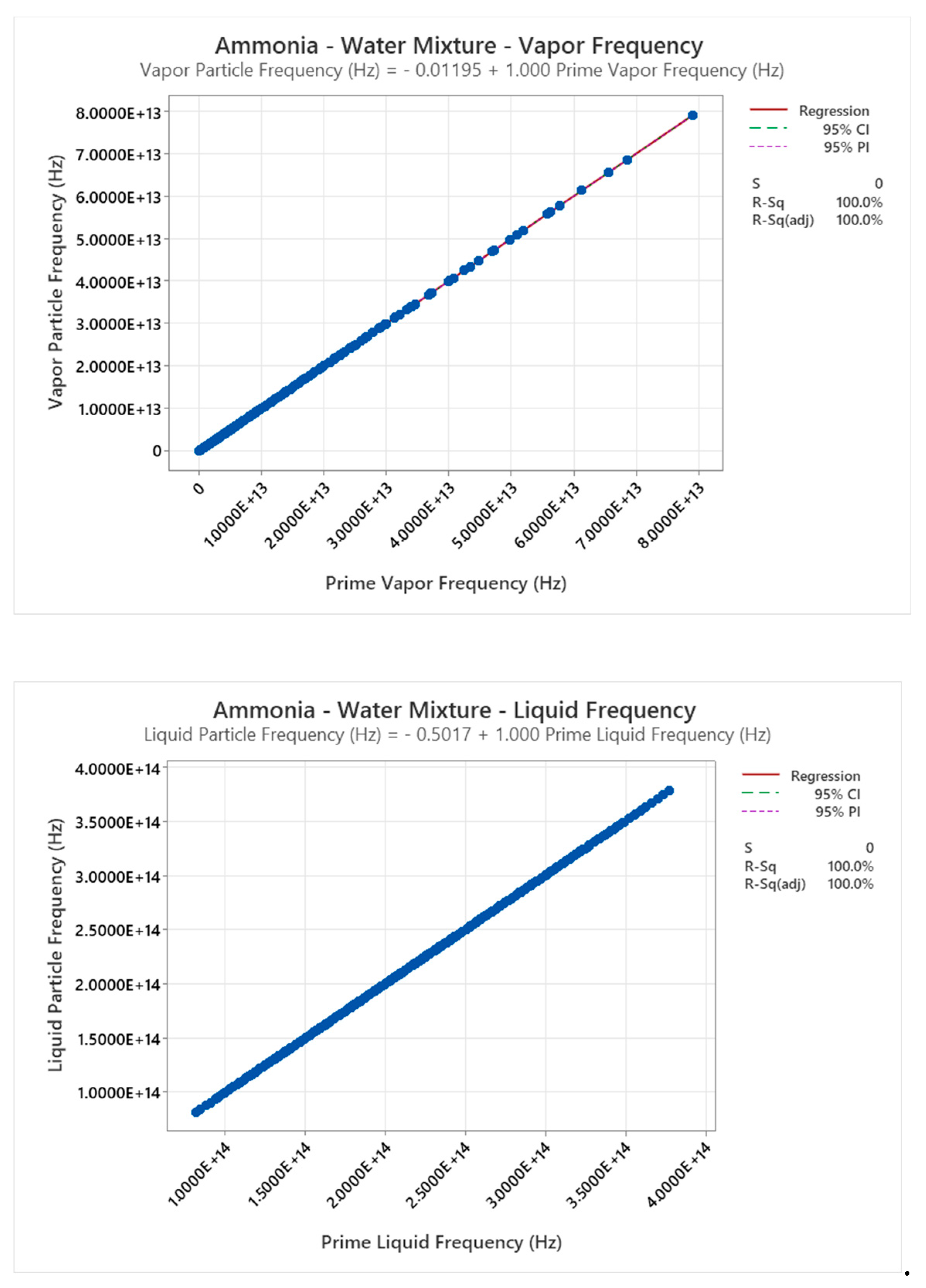

- Frequency from UEOS, with exact from Z: .

- ○

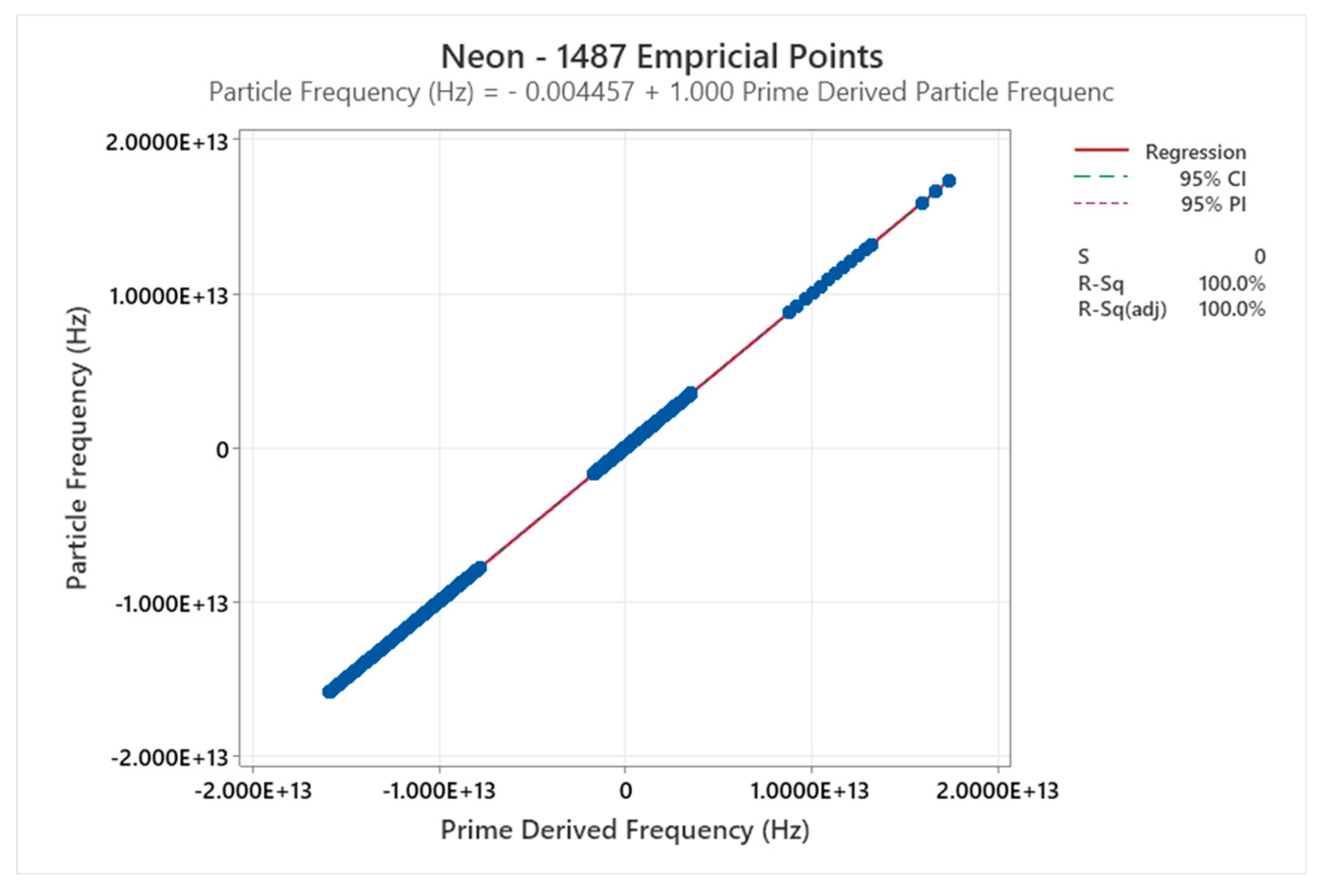

- Code logic: Loop over rows, group by T, sort by P, compute values starting from column M (as in provided code for Methane, adapted for Neon with C=2).

3.4. Verification and Analysis Techniques

4. Results

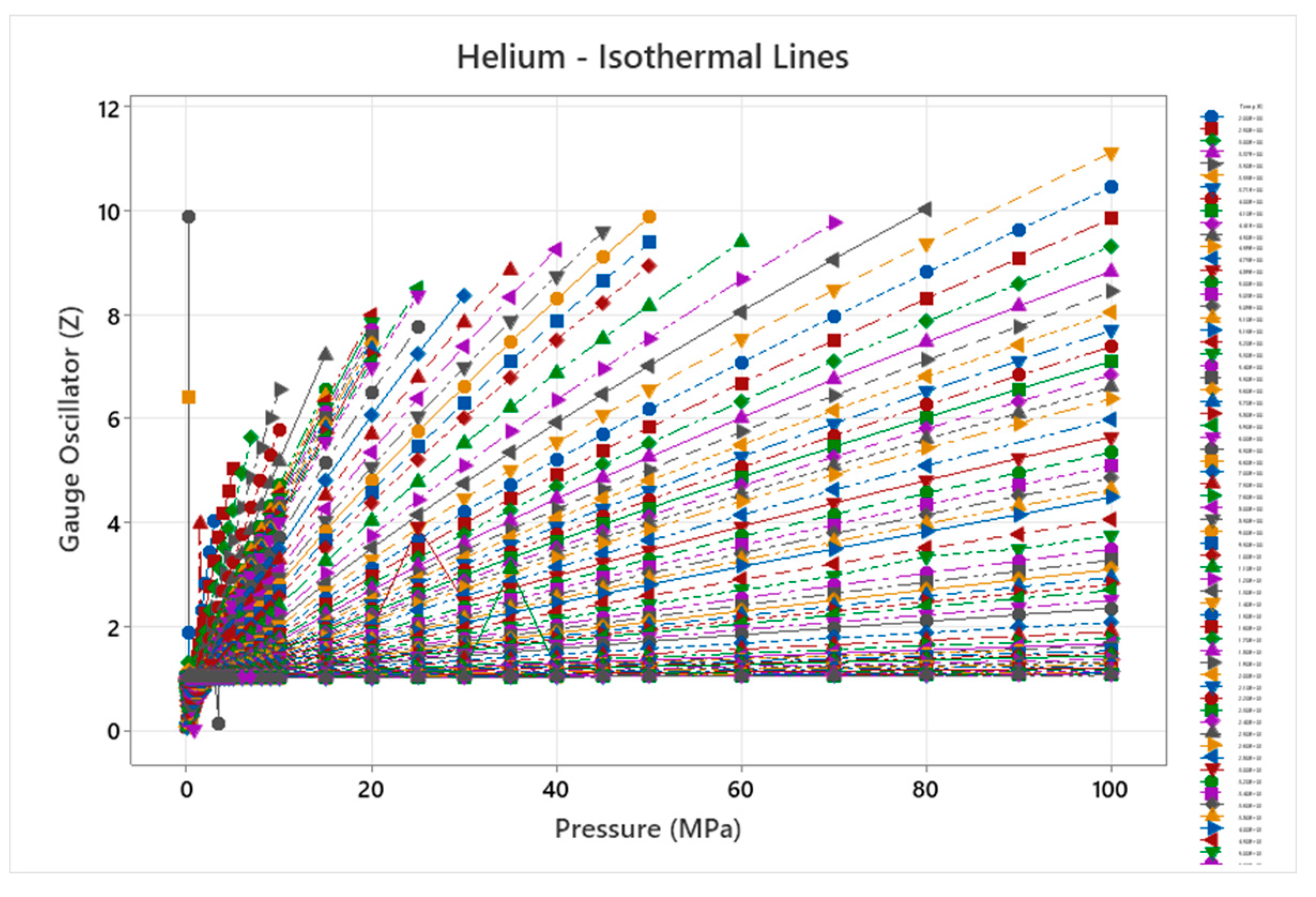

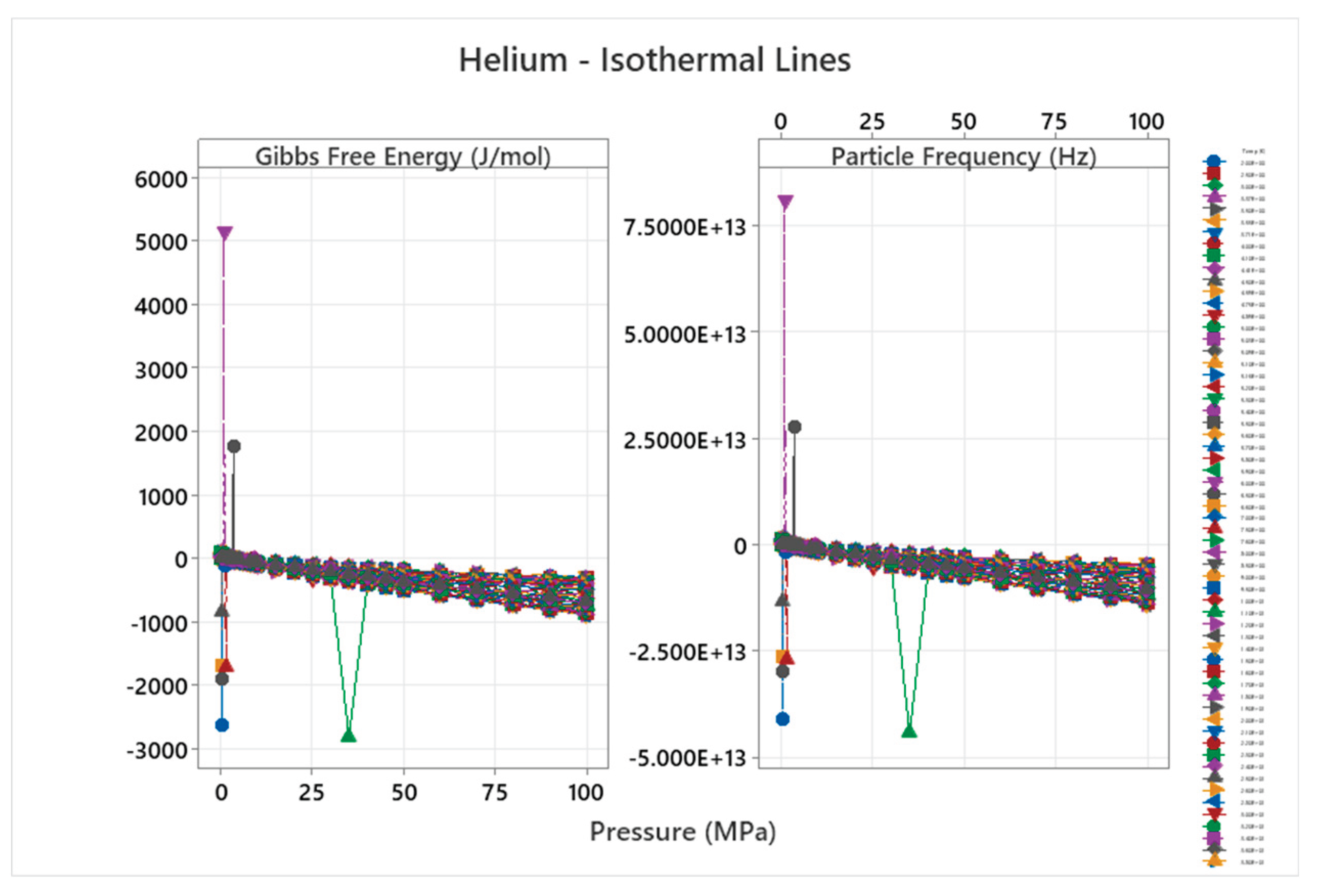

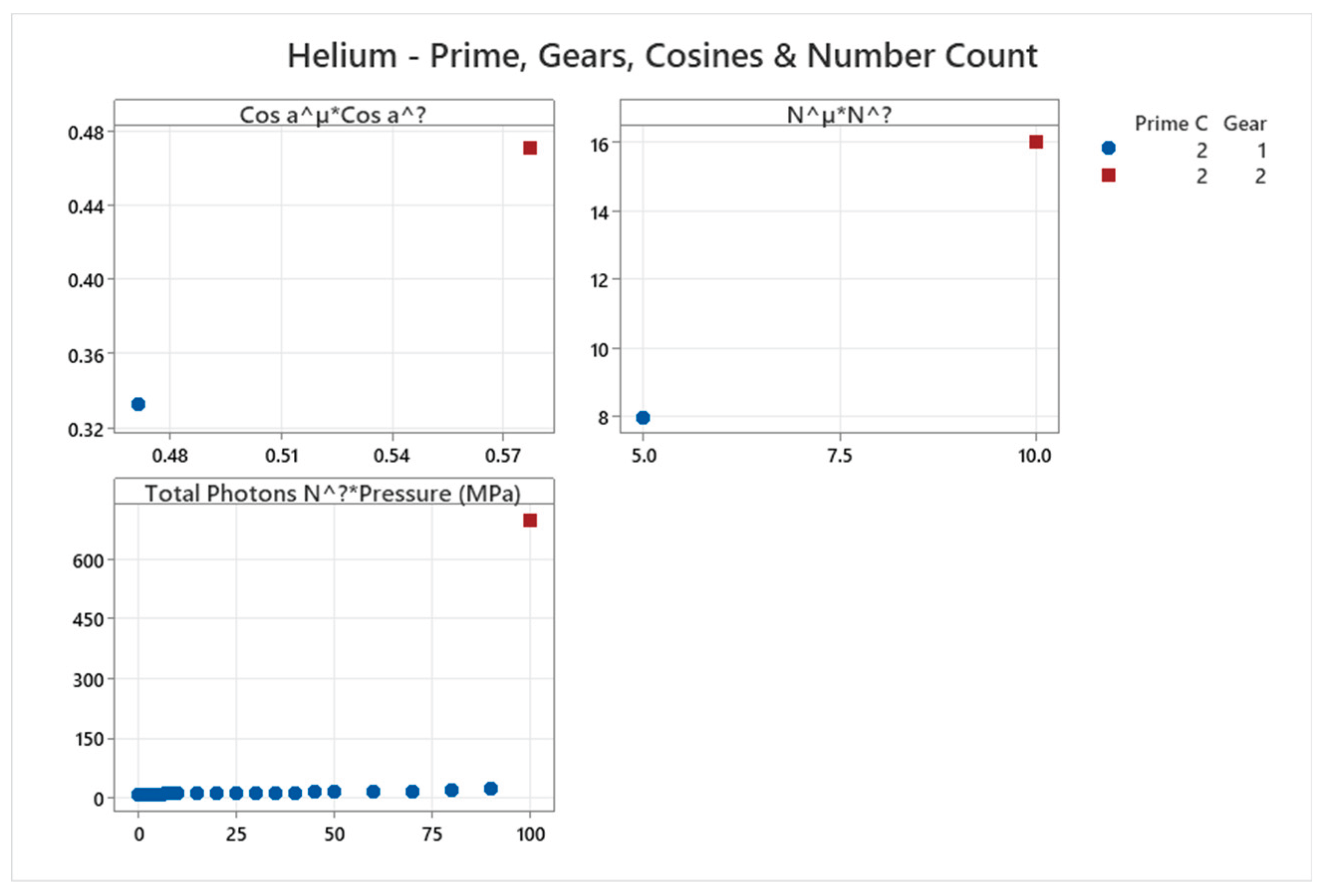

4.1. Helium Phase Diagram

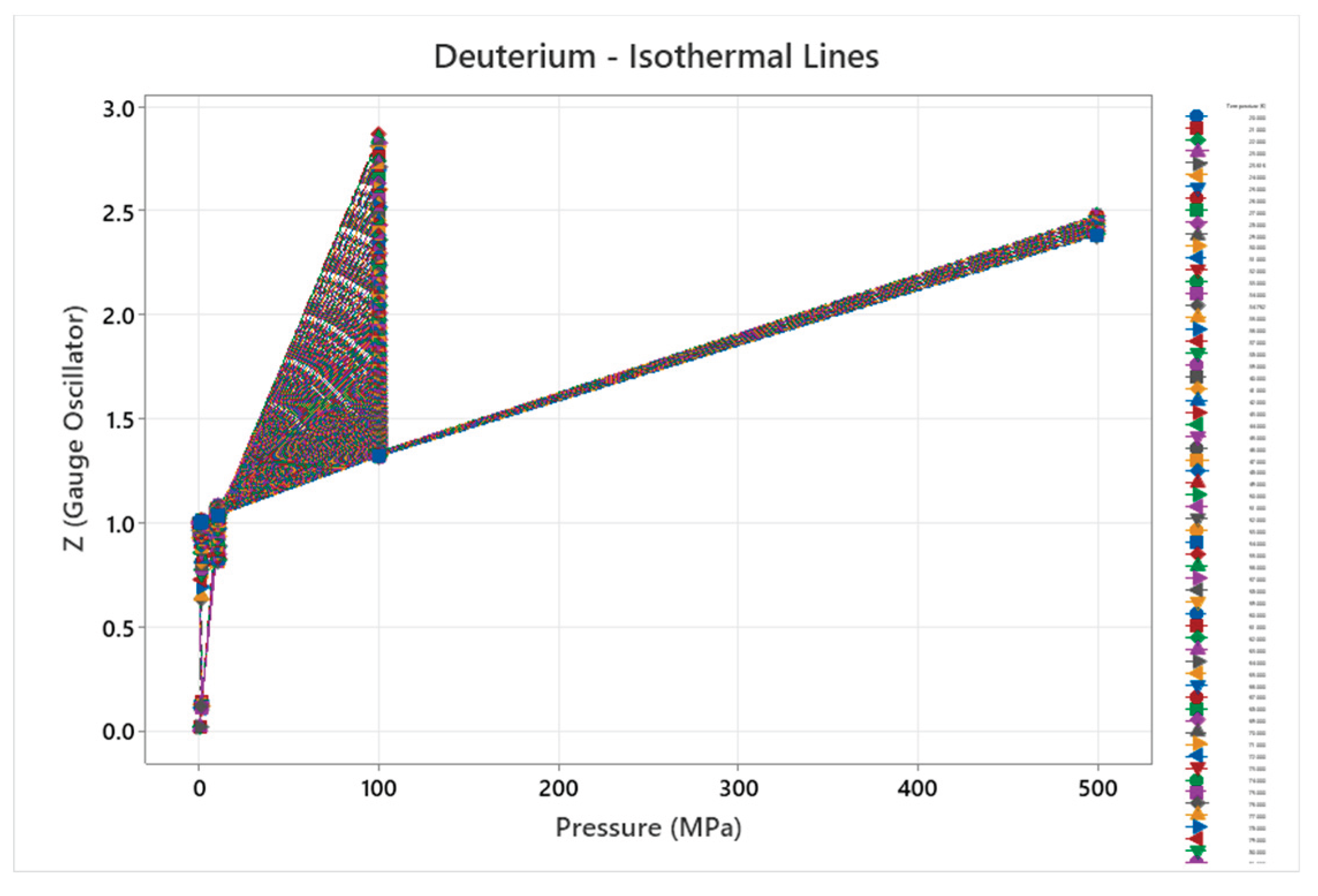

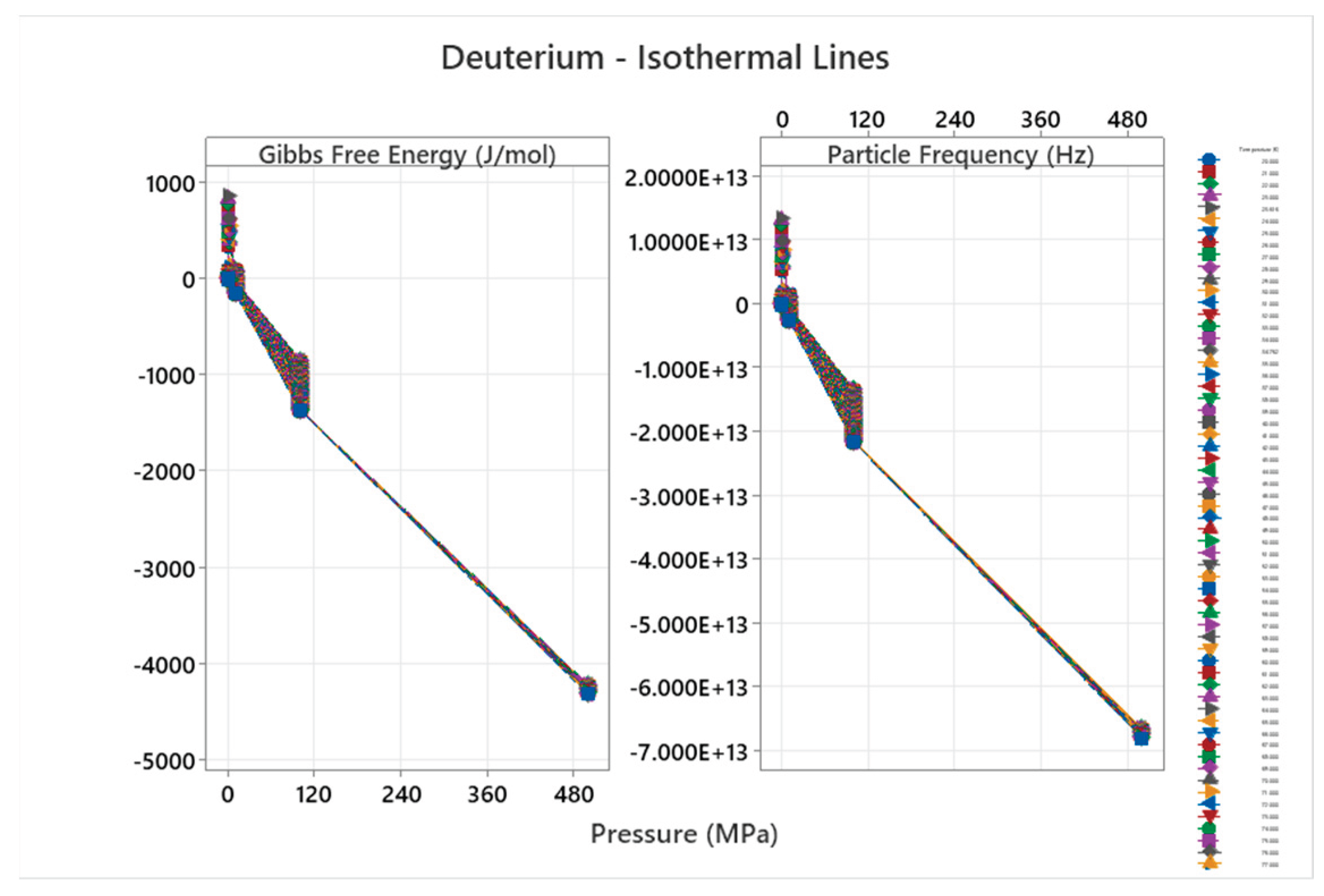

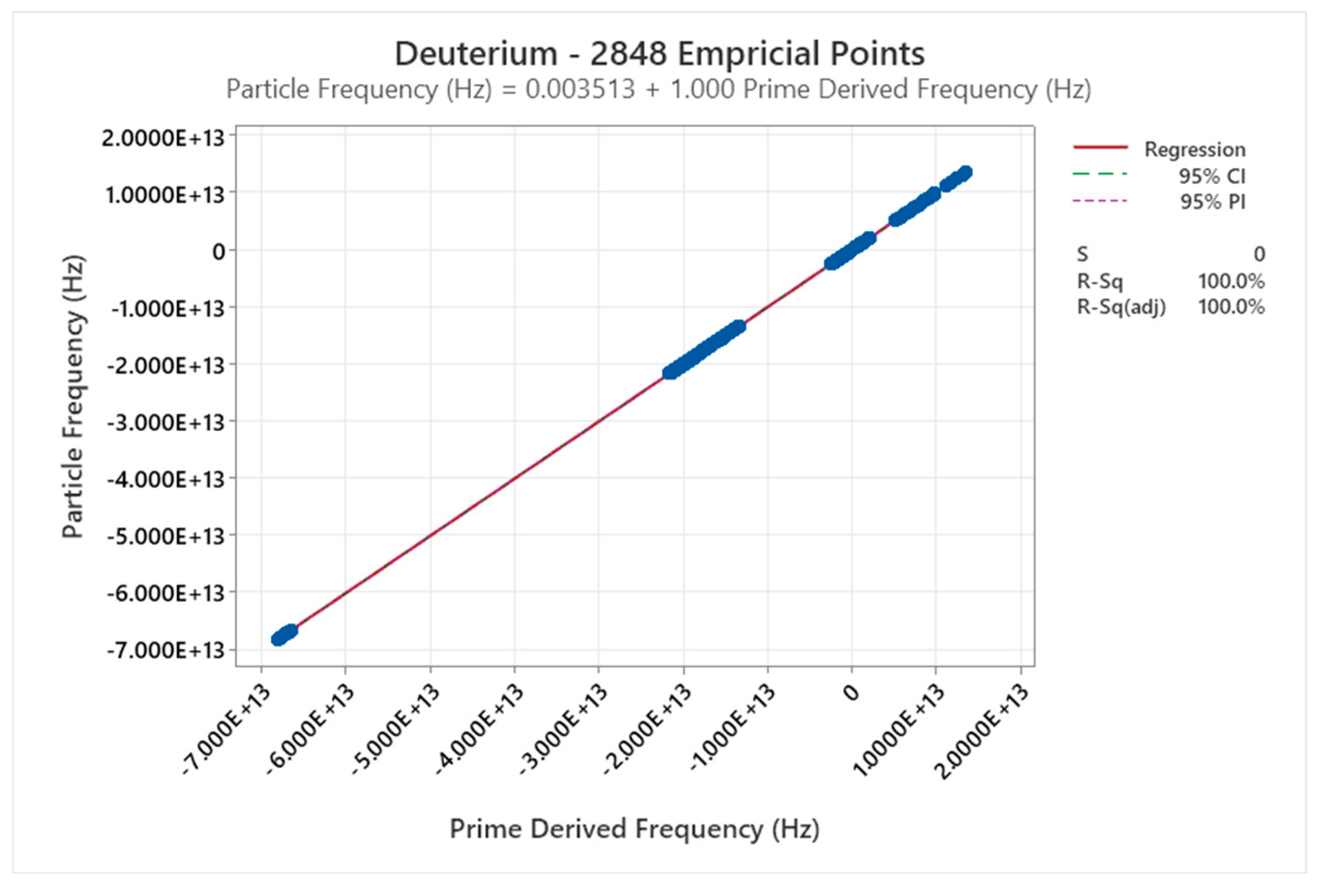

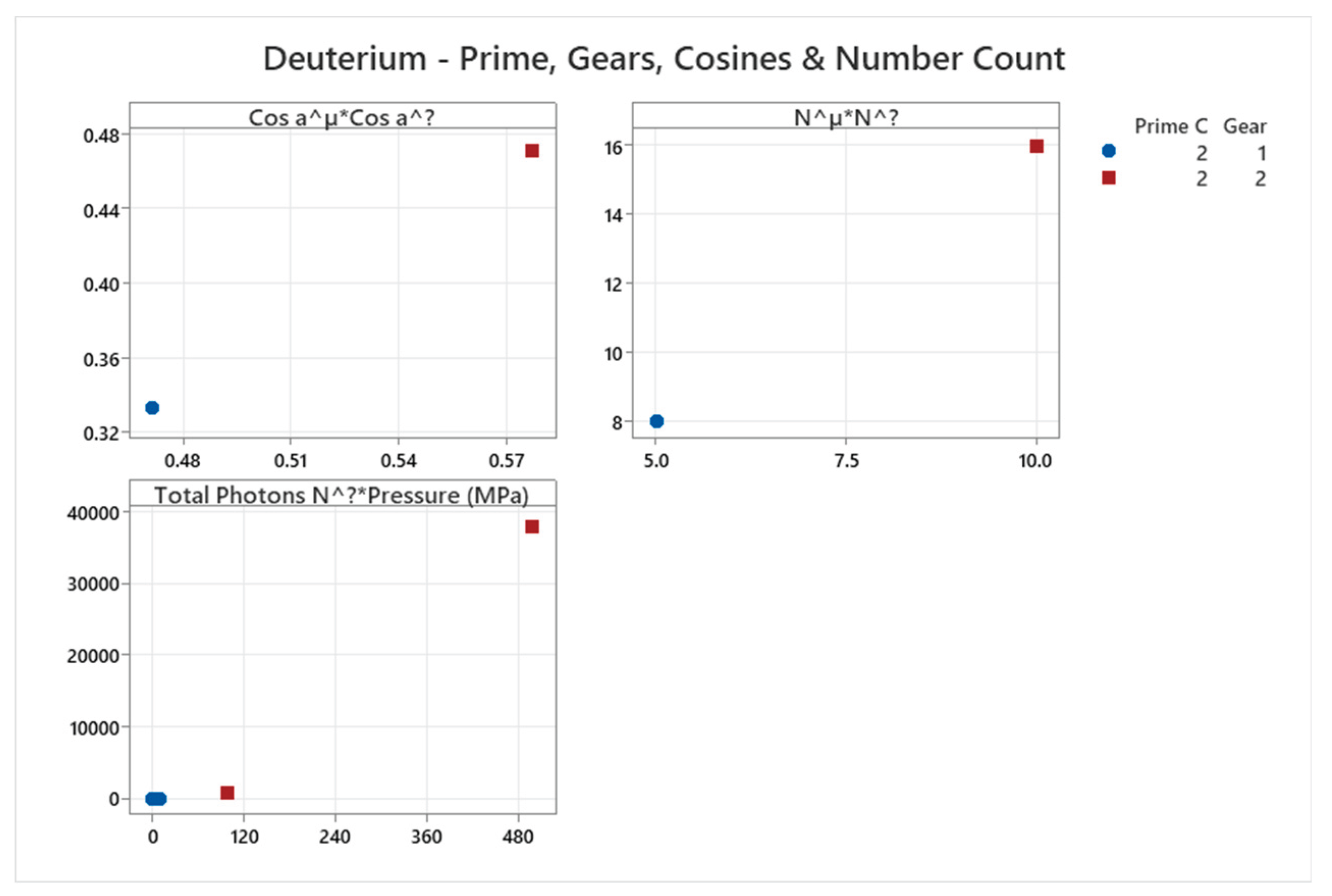

4.2. Deuterium Phase Diagram

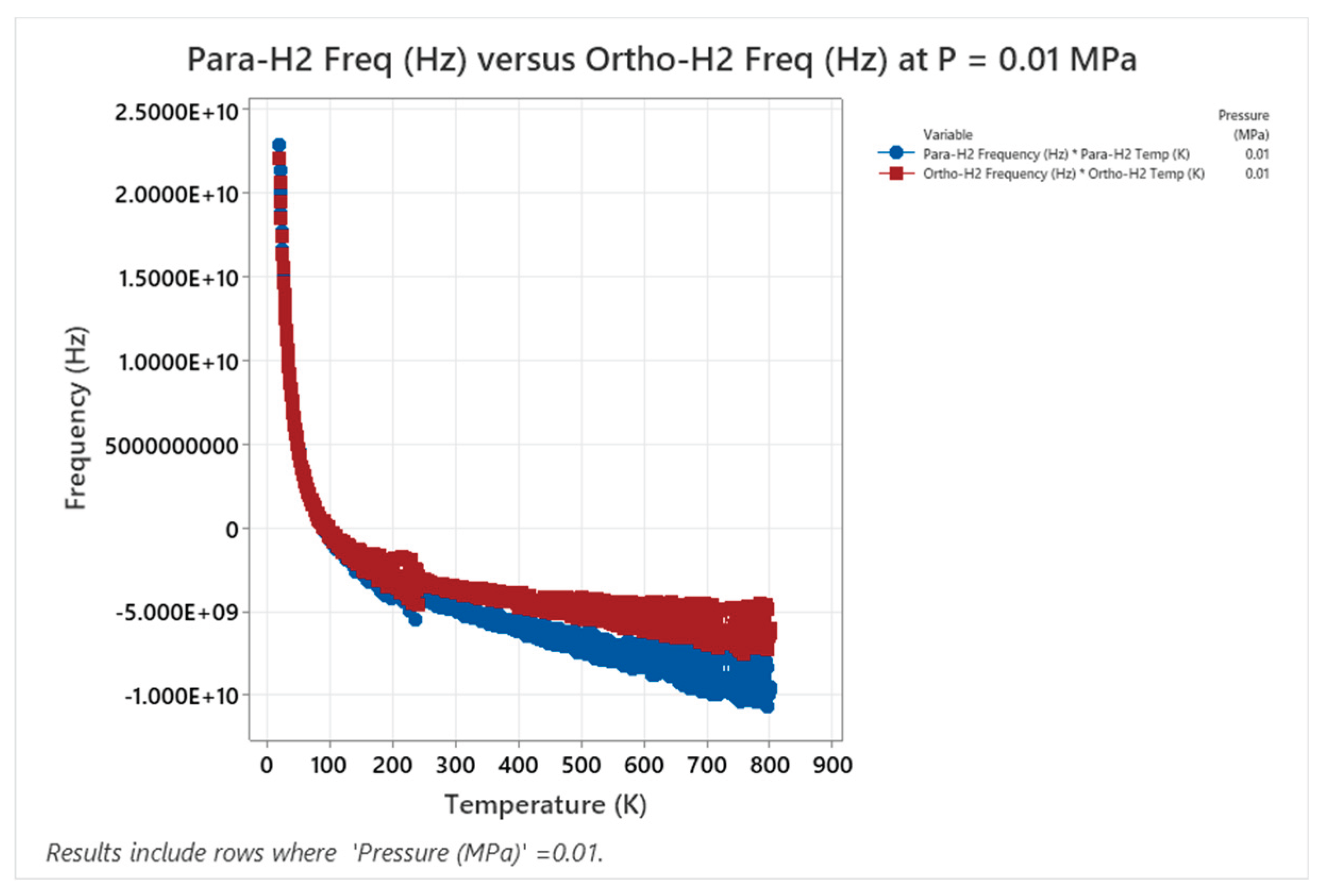

4.3. Ortho Hydrogen Phase Diagram

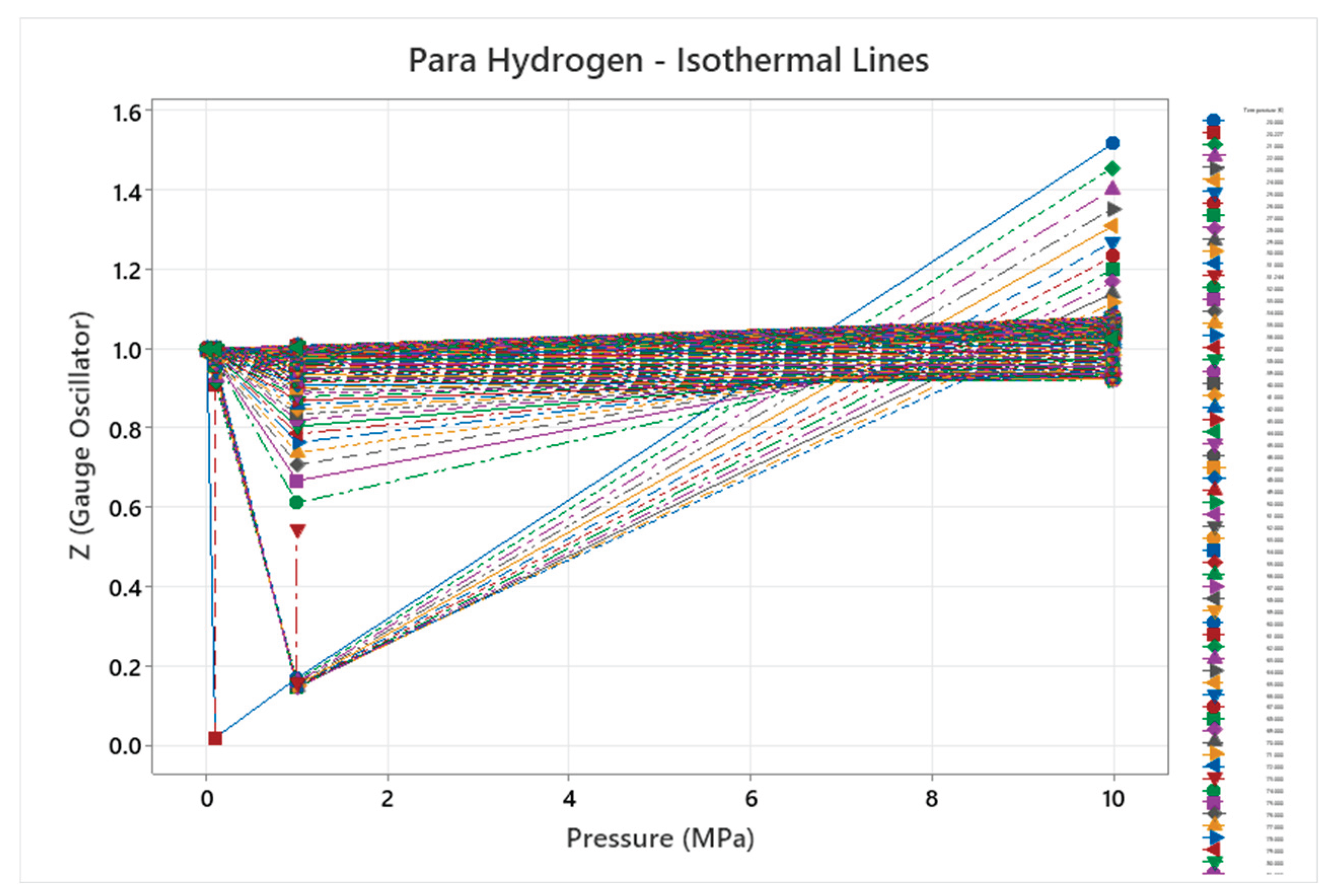

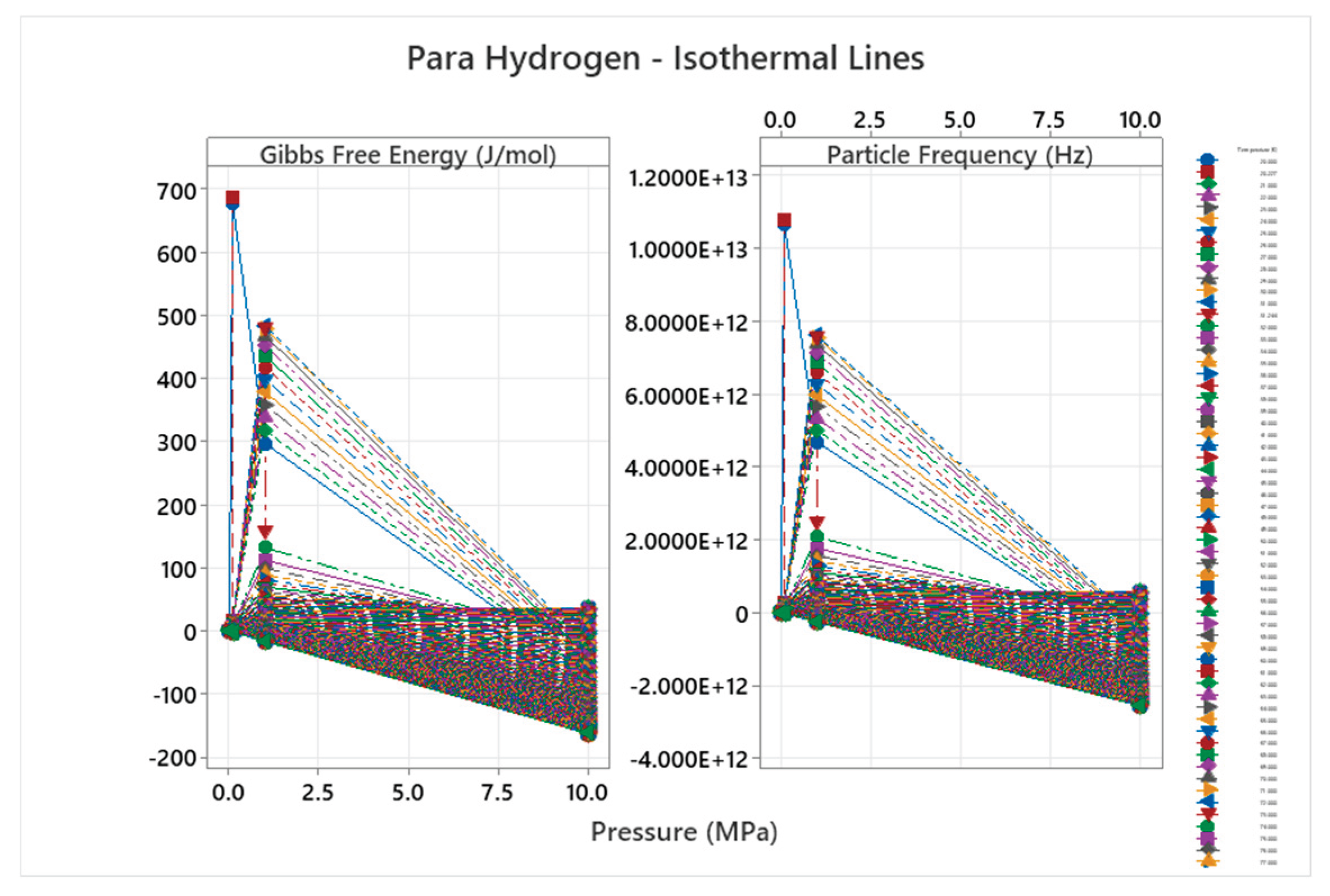

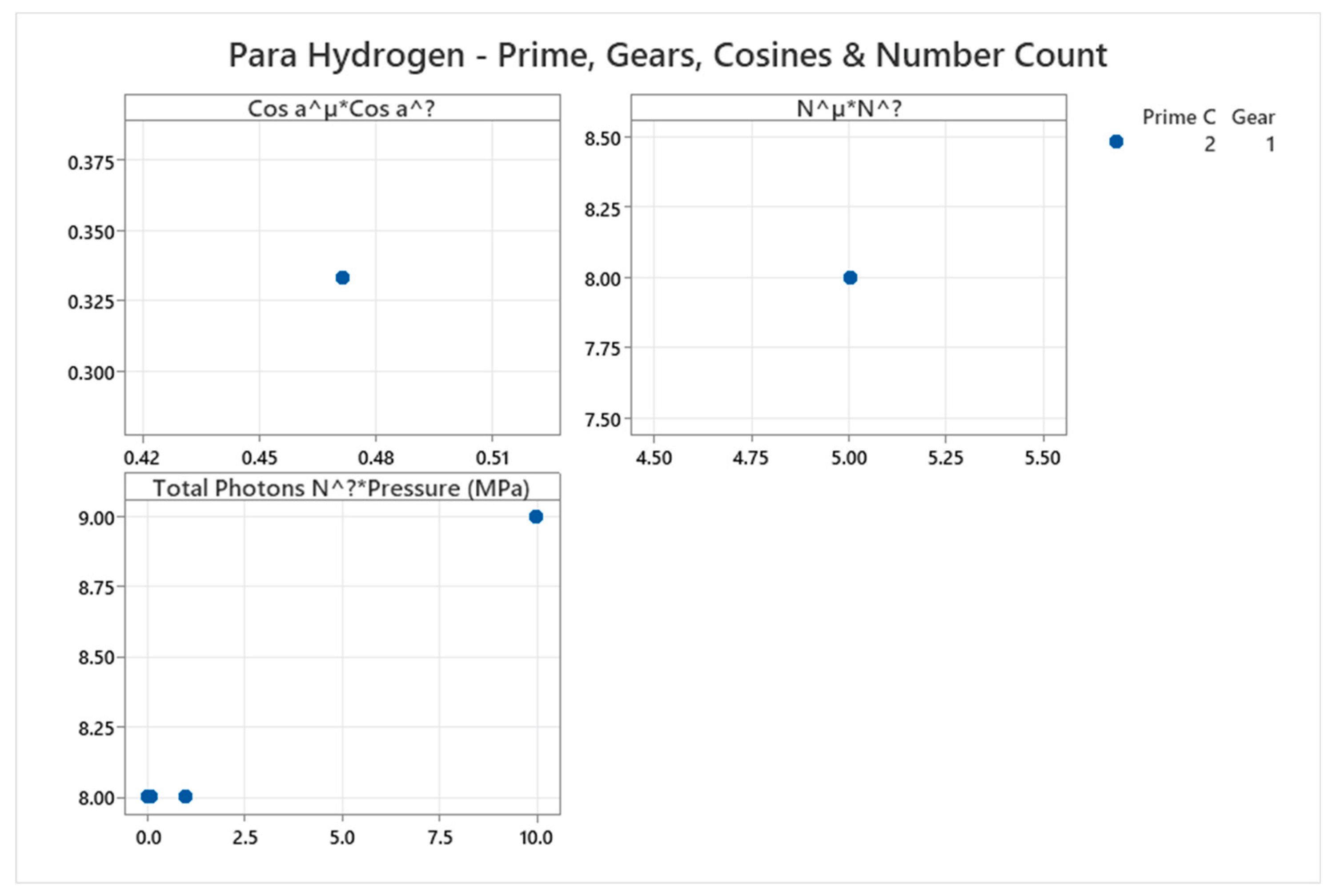

4.4. Para Hydrogen Phase Diagram

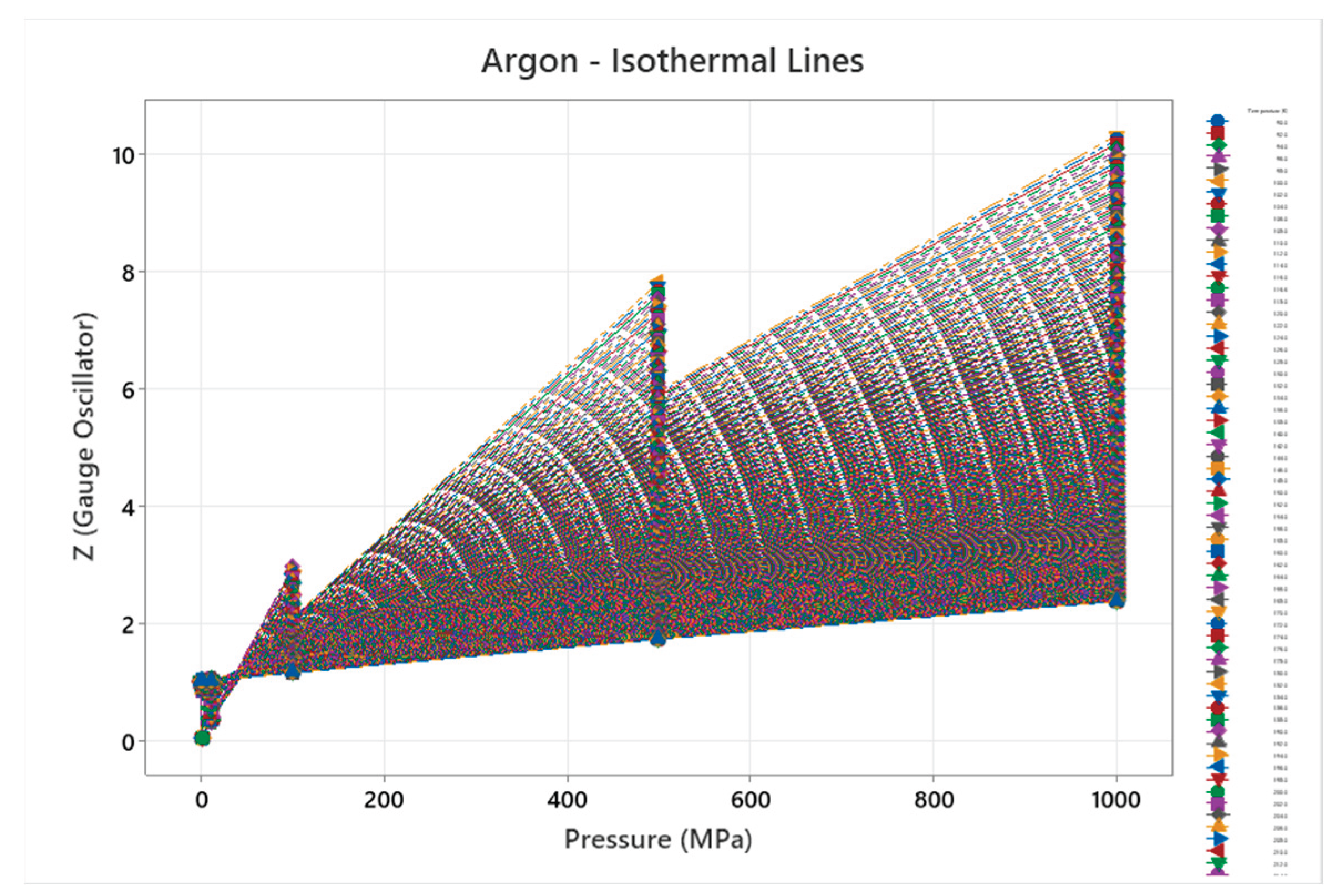

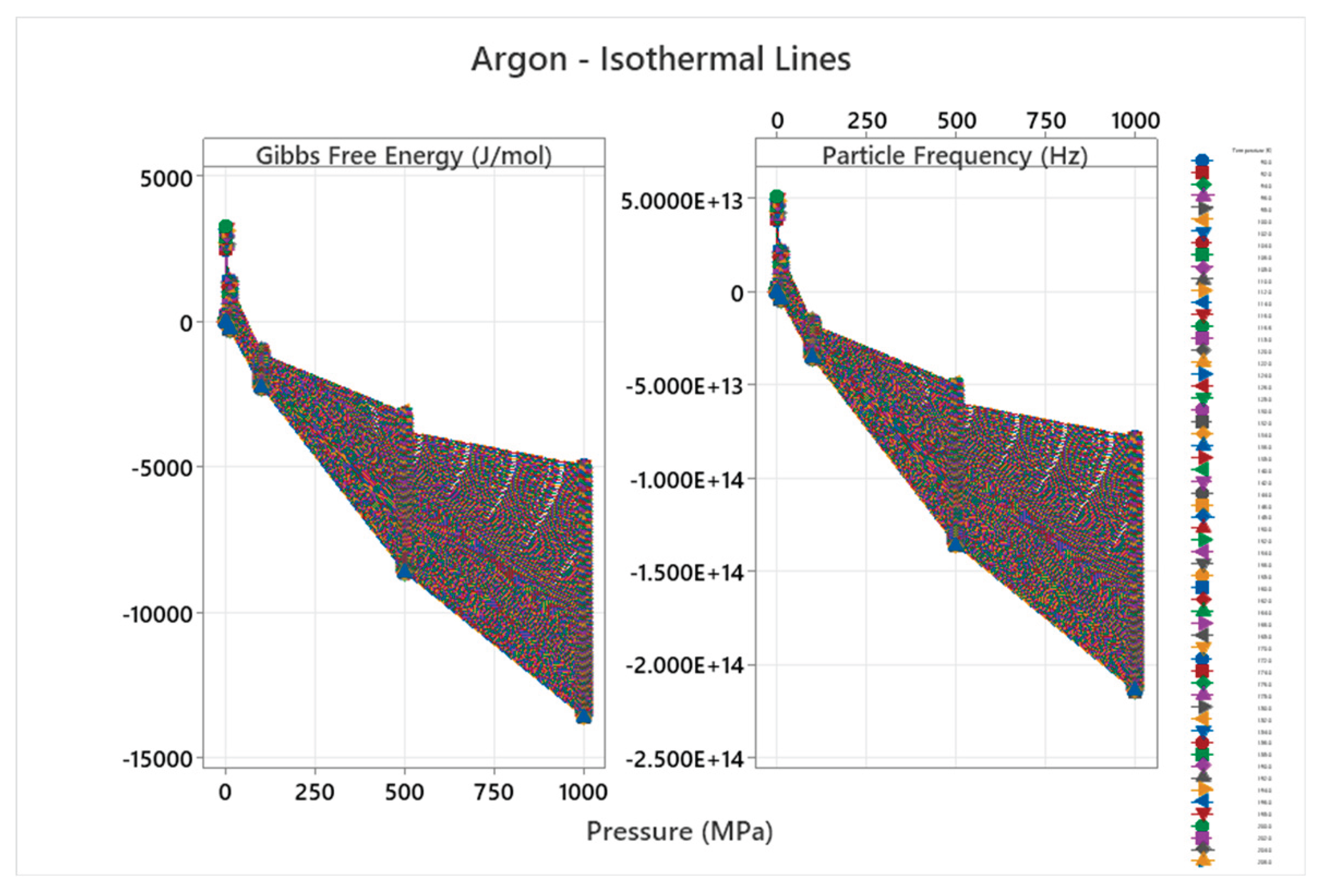

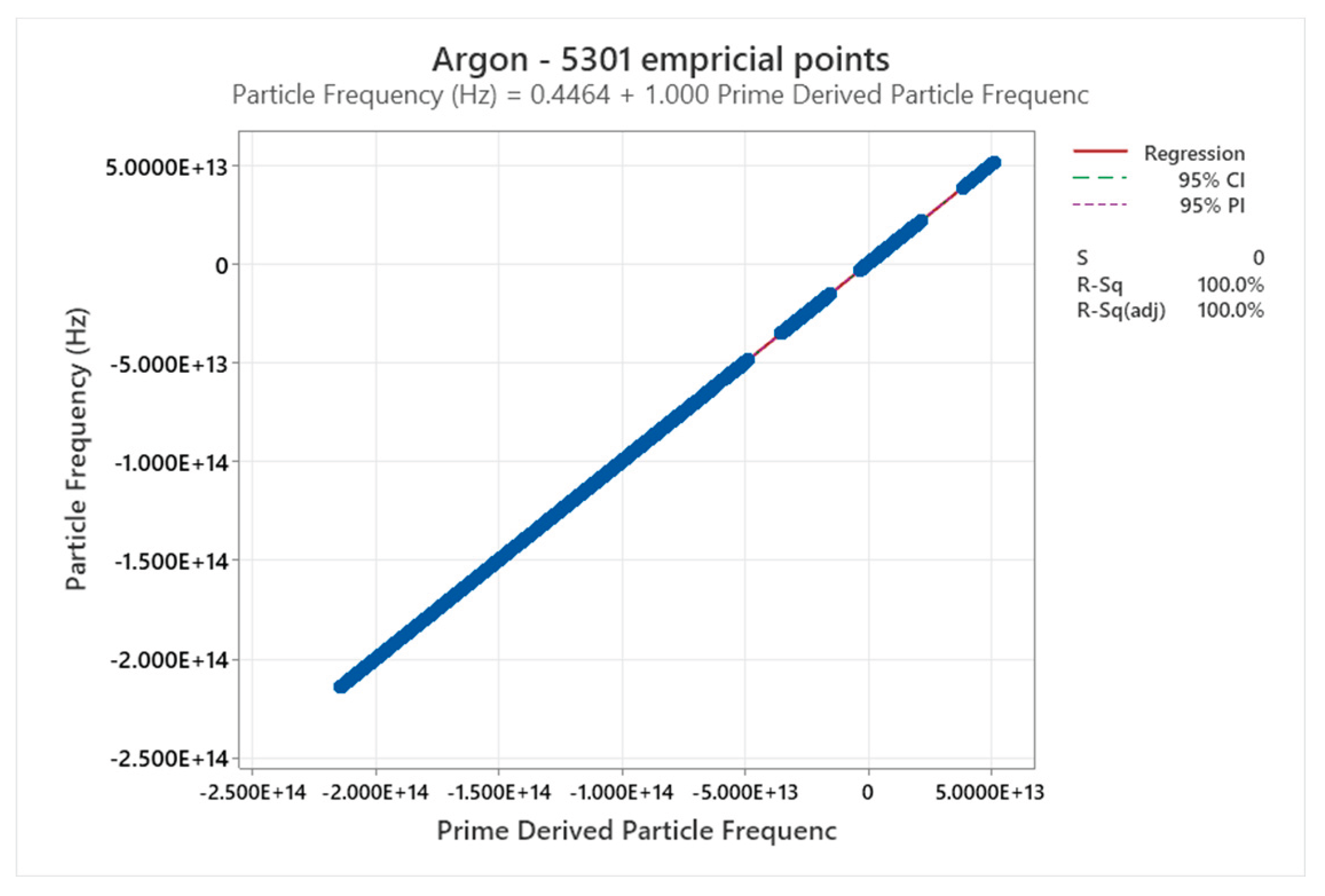

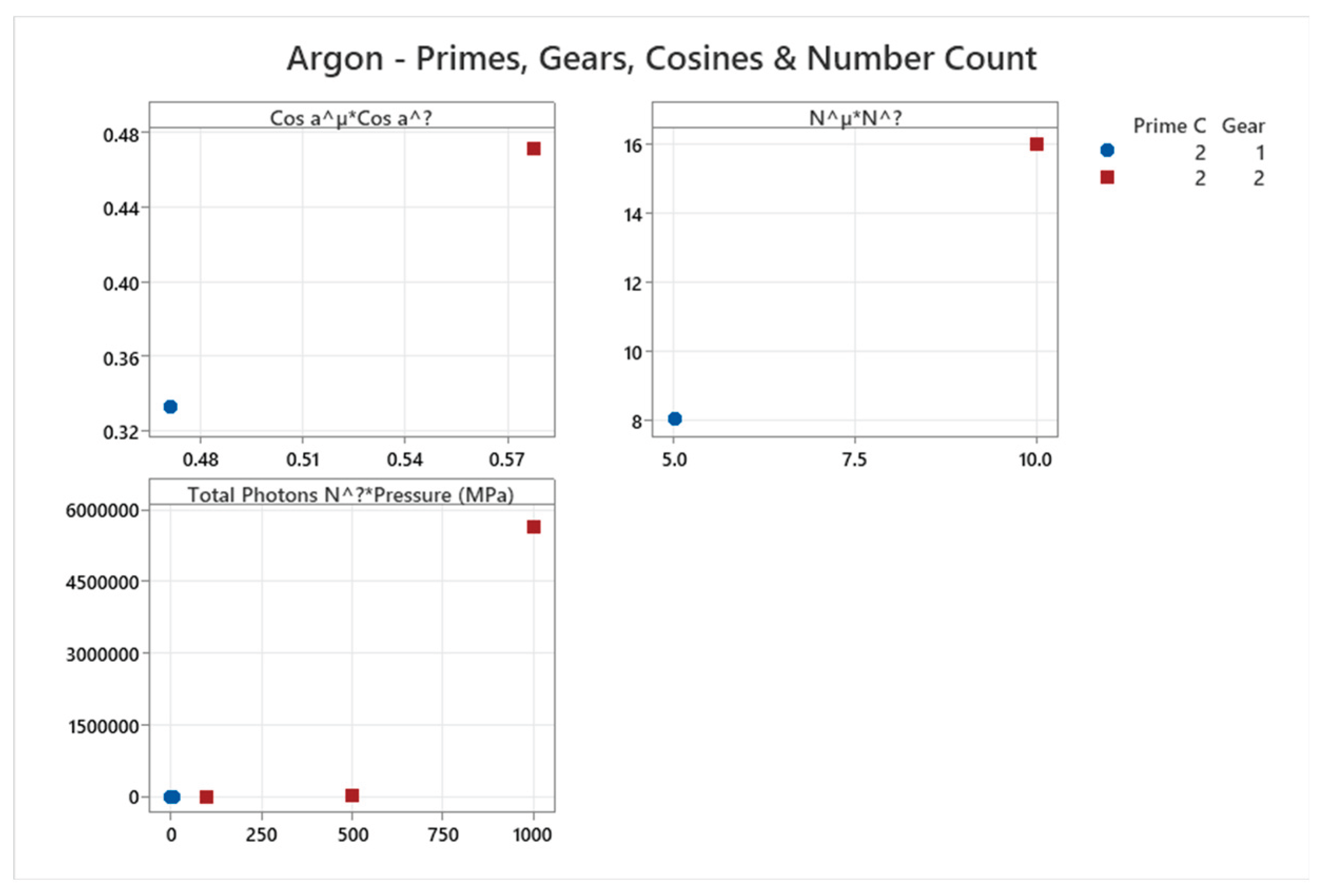

4.5. Argon Phase Diagram

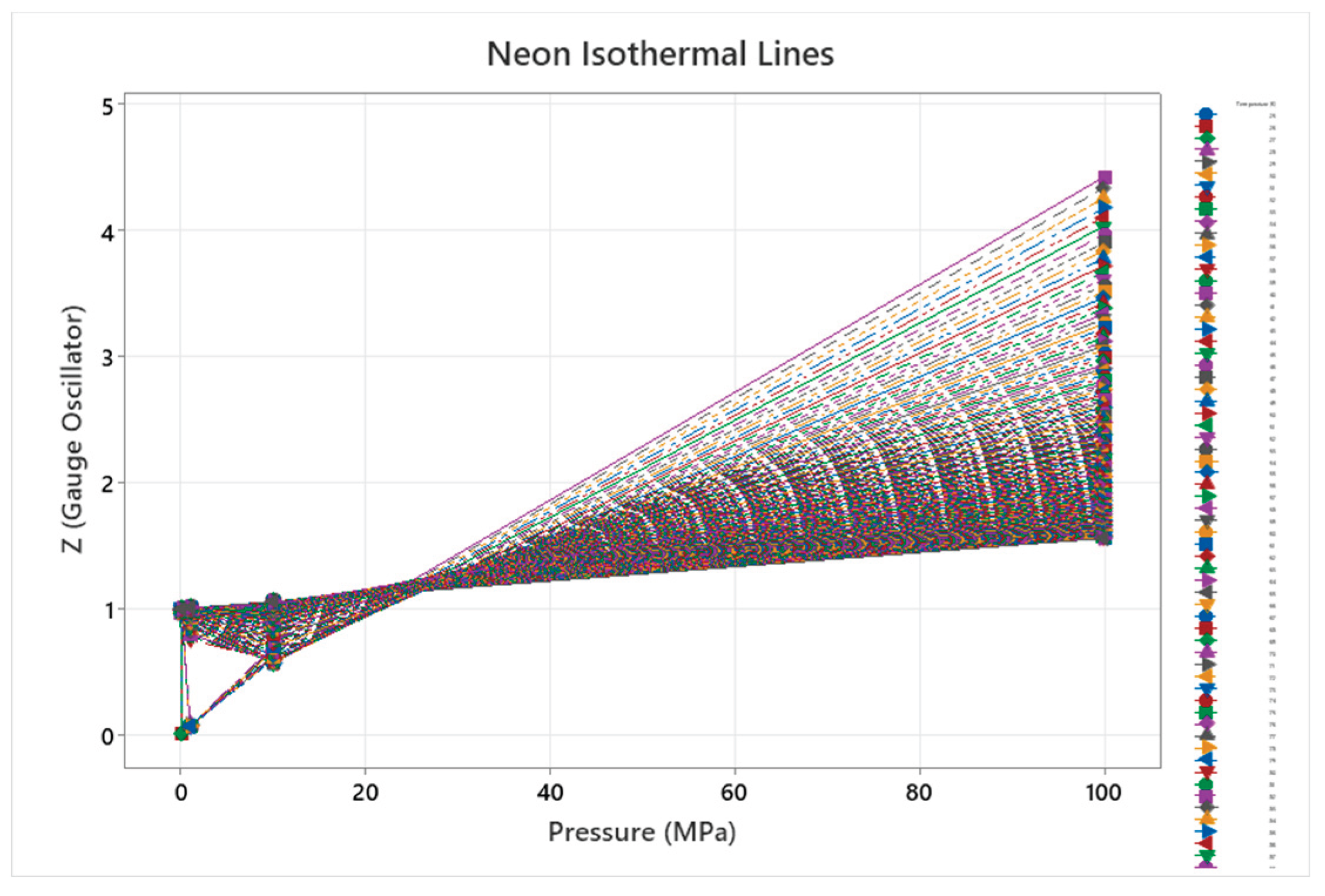

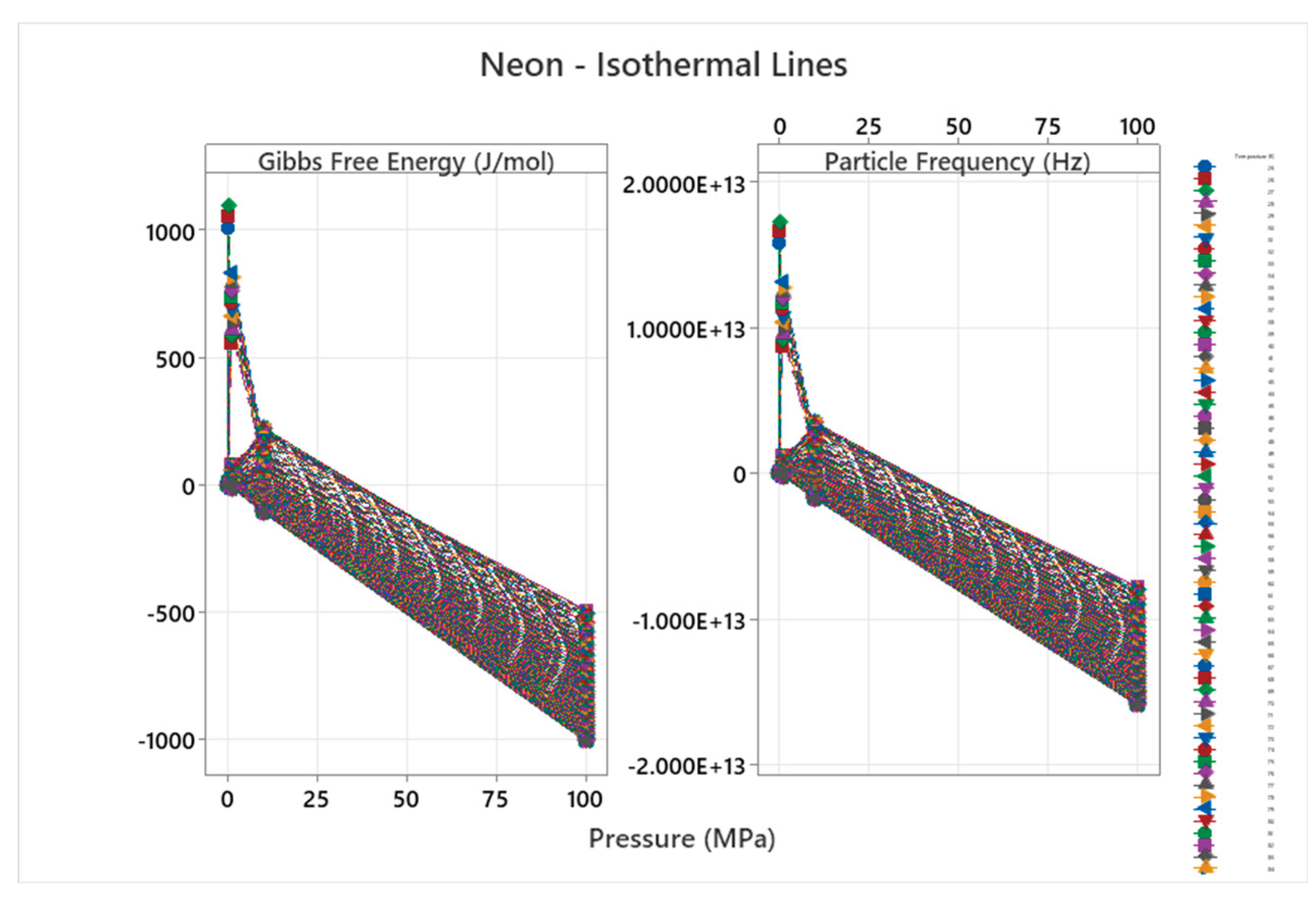

4.6. Neon Phase Diagram

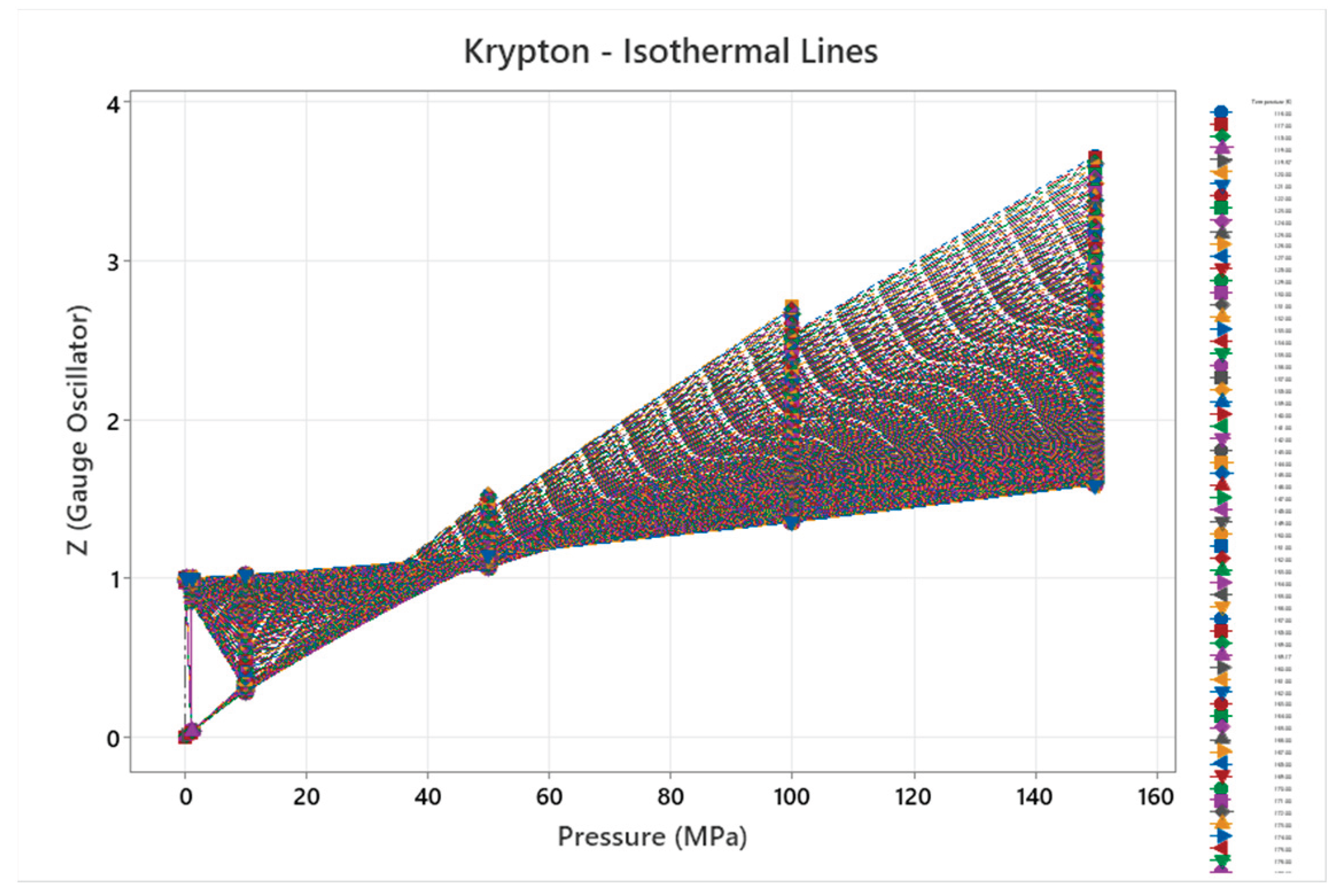

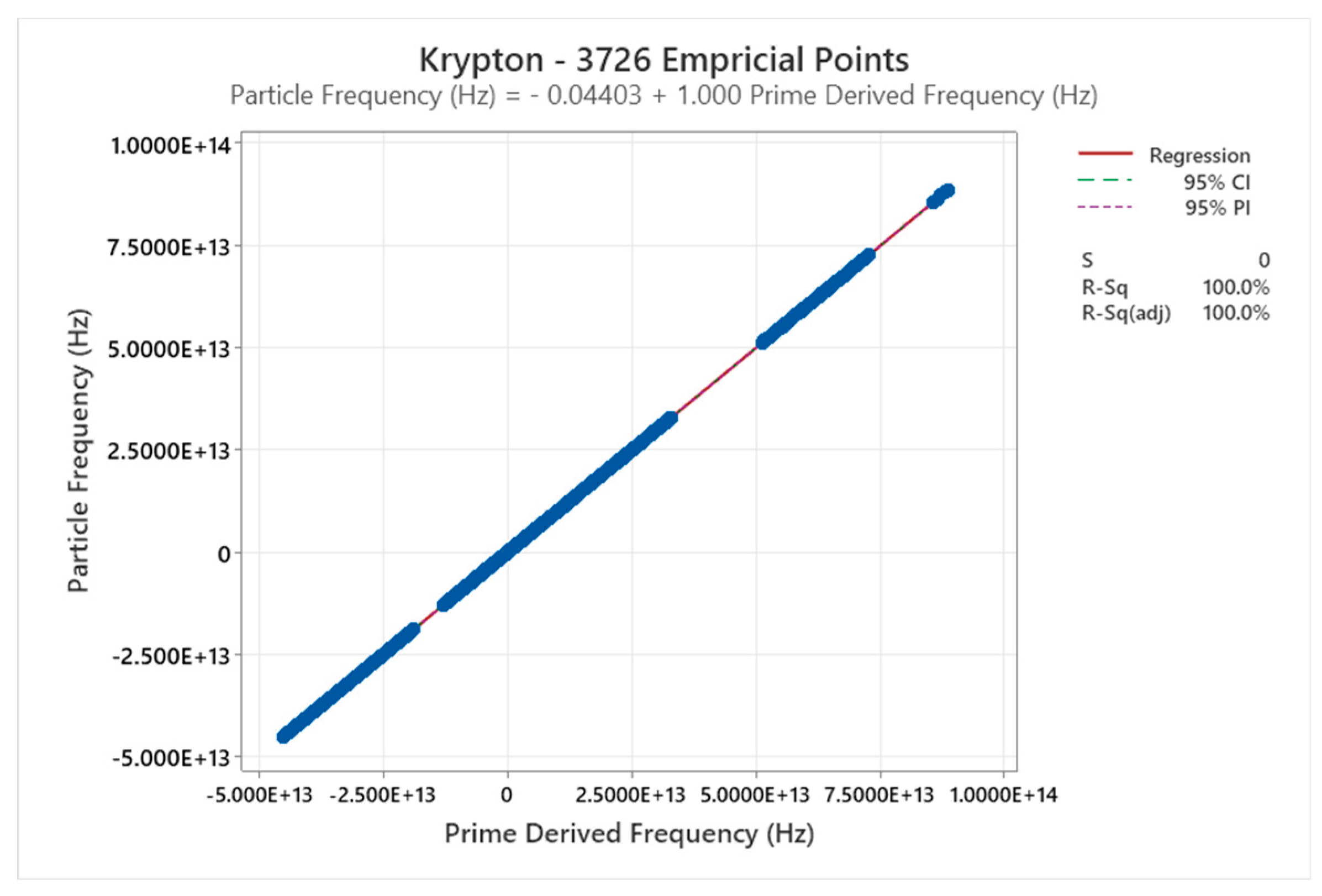

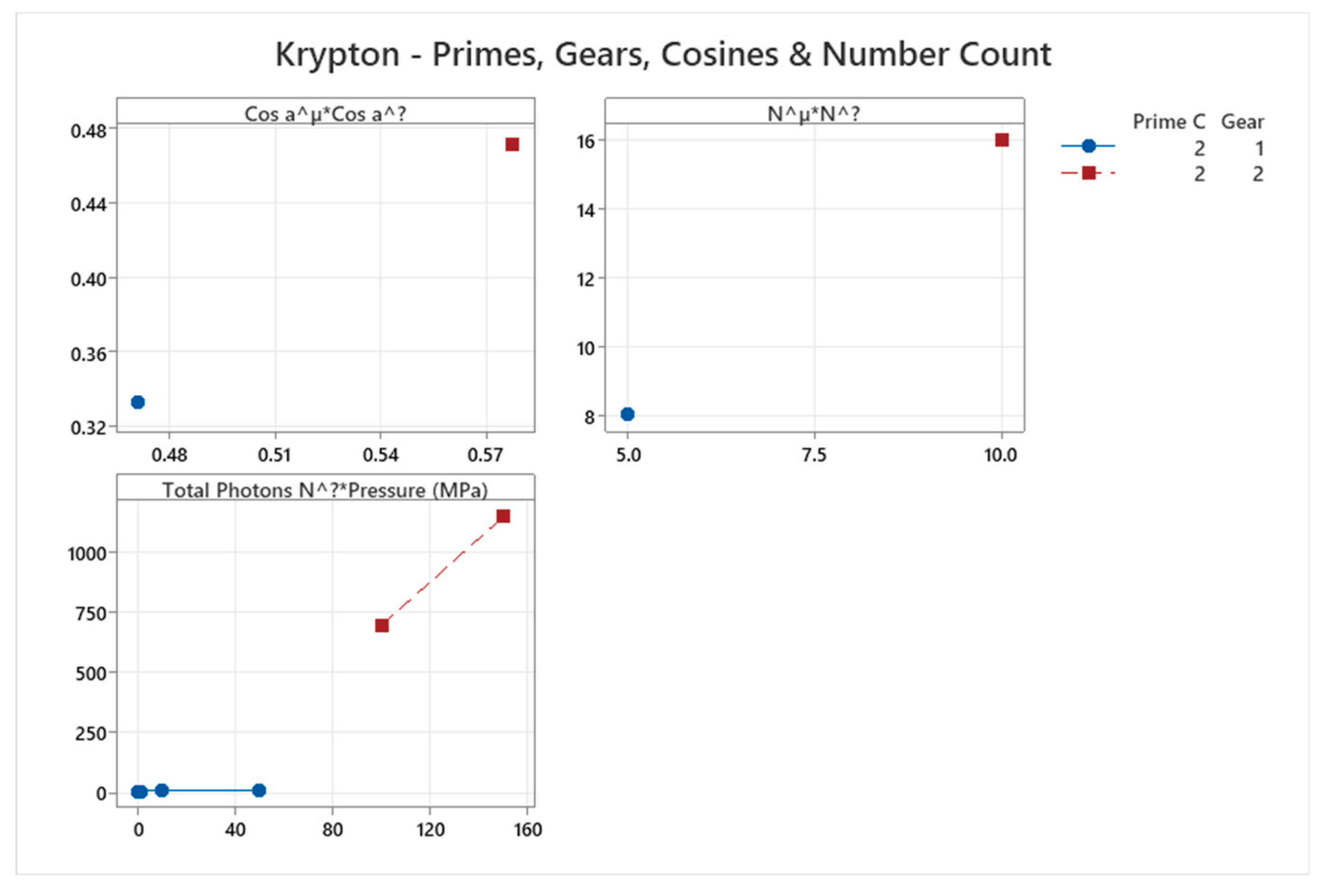

4.7. Krypton Phase Diagram

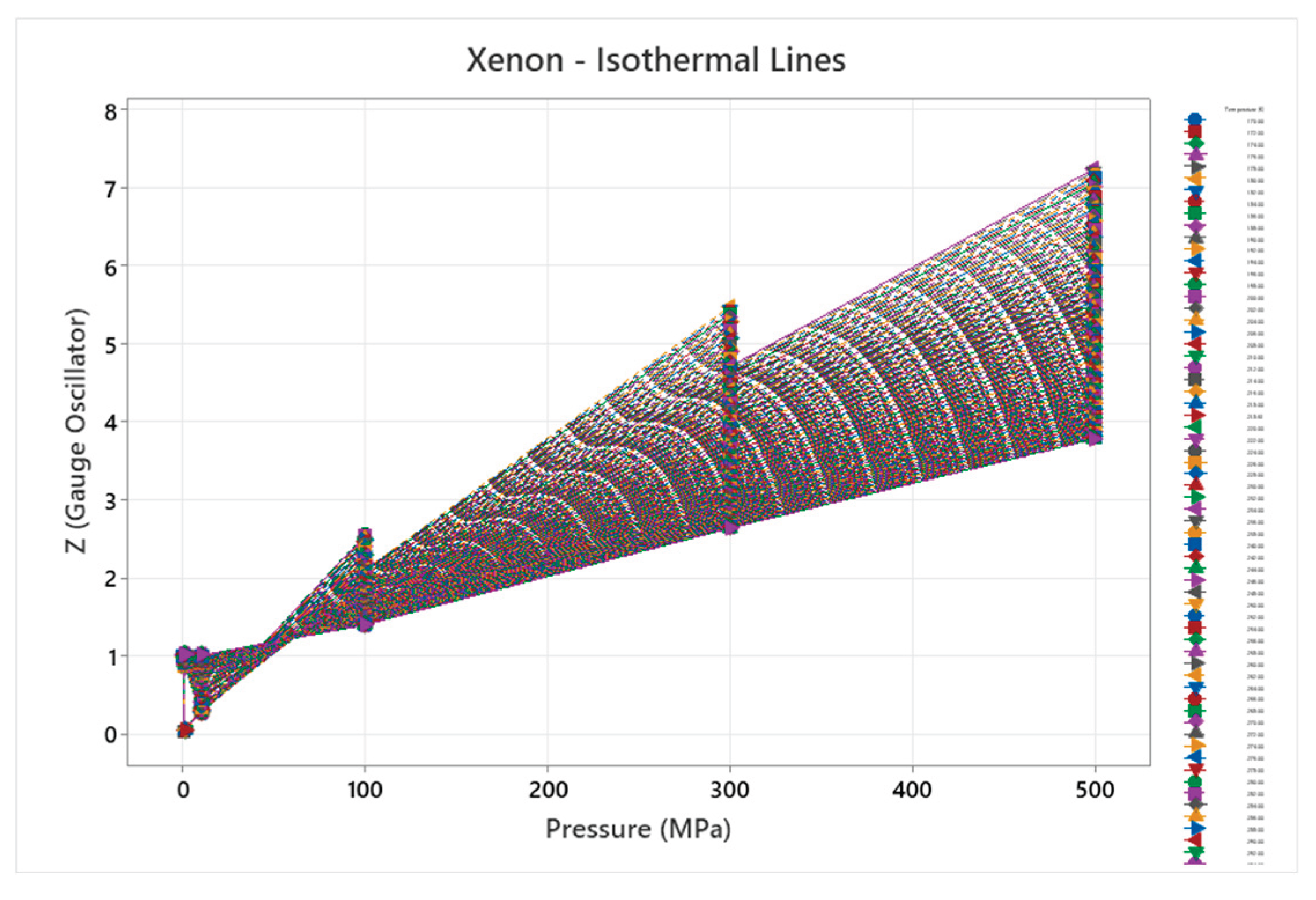

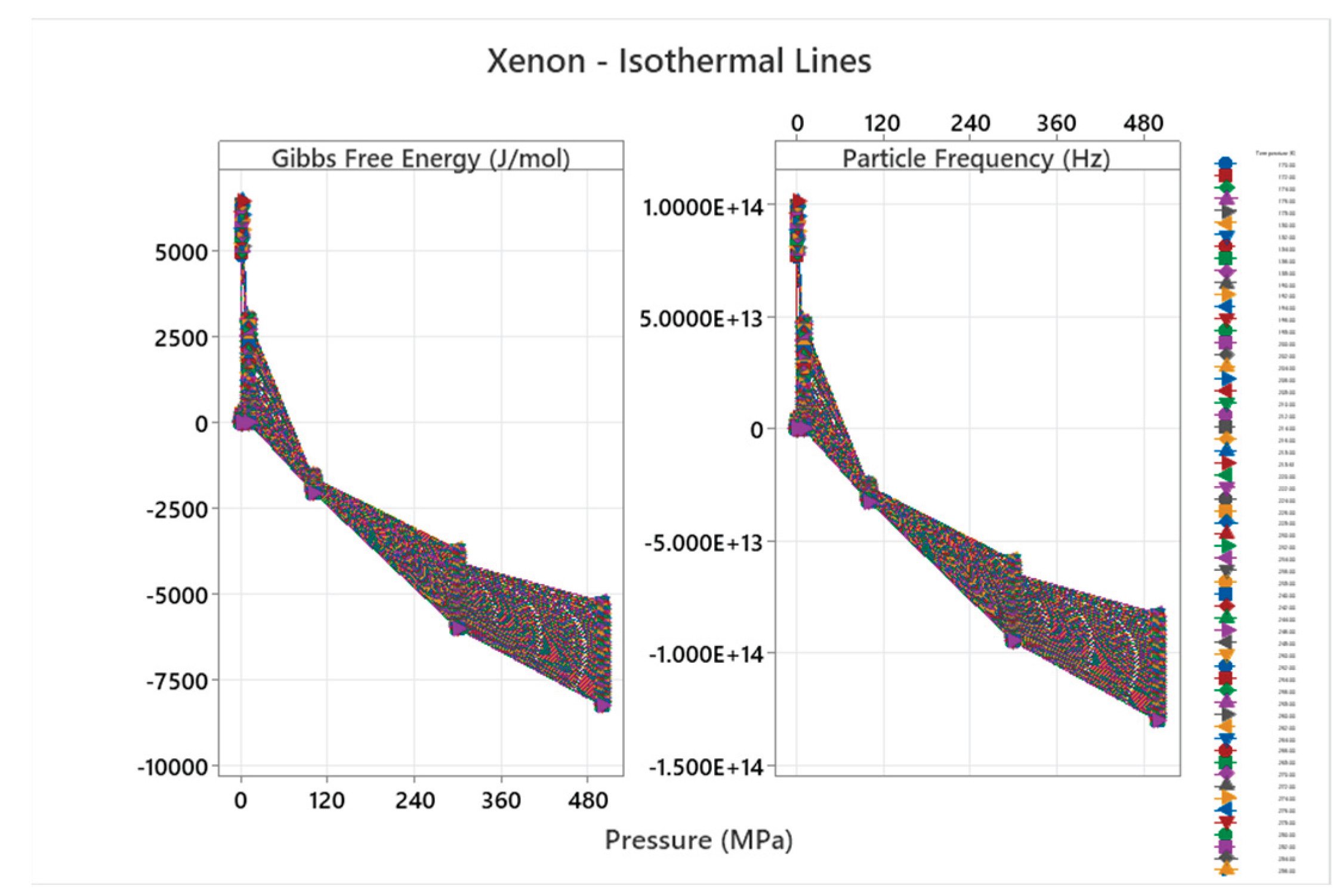

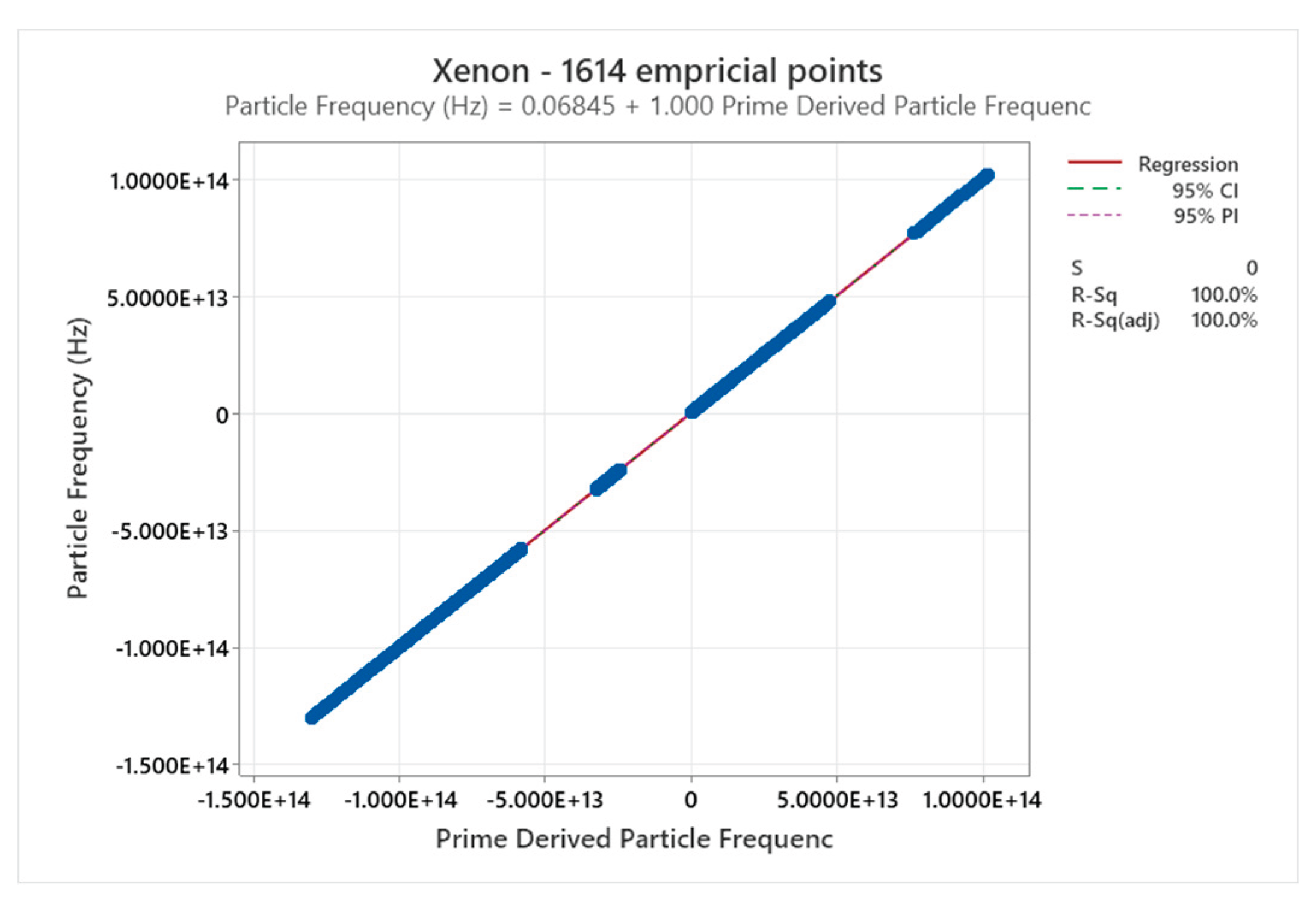

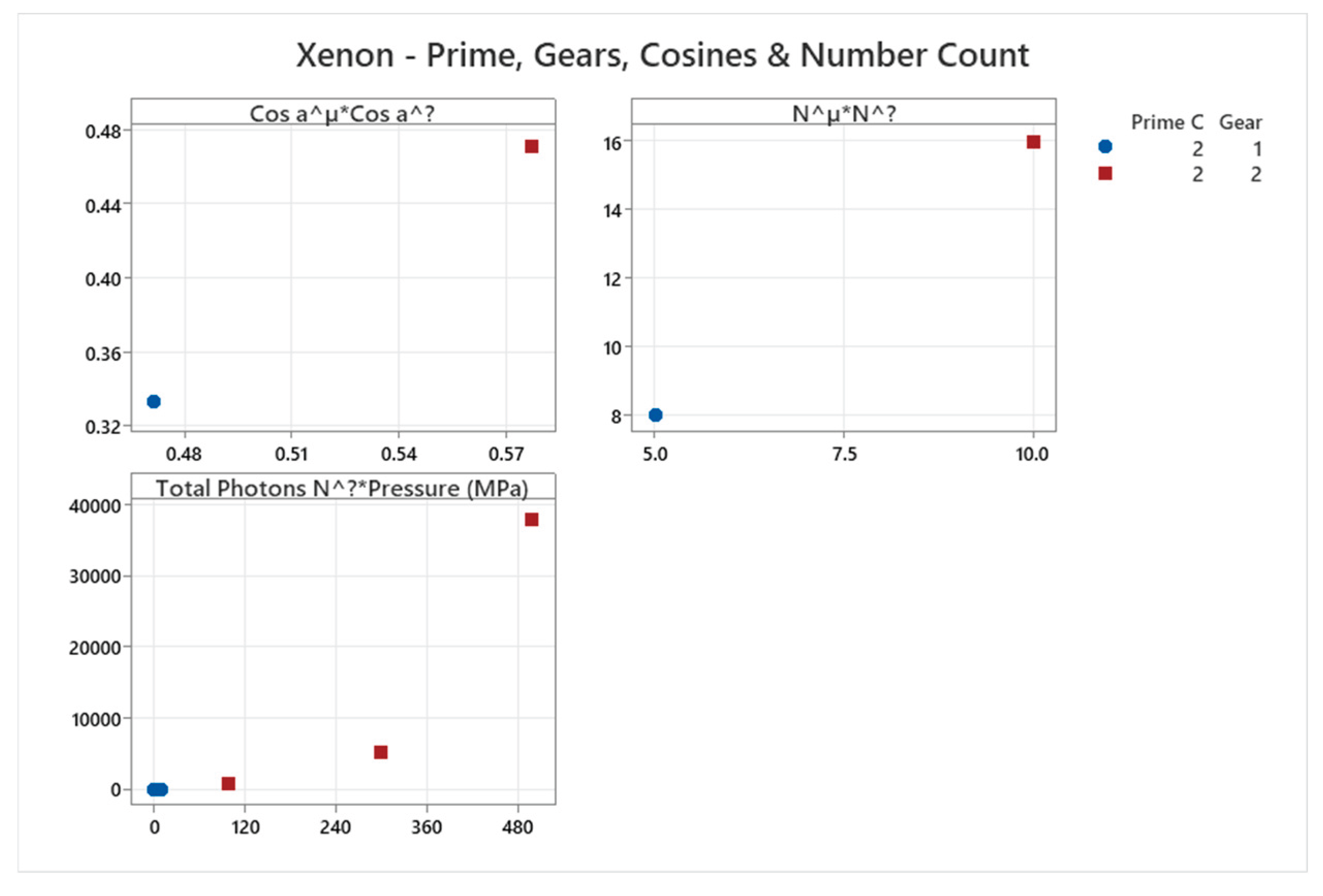

4.8. Xenon Phase Diagram

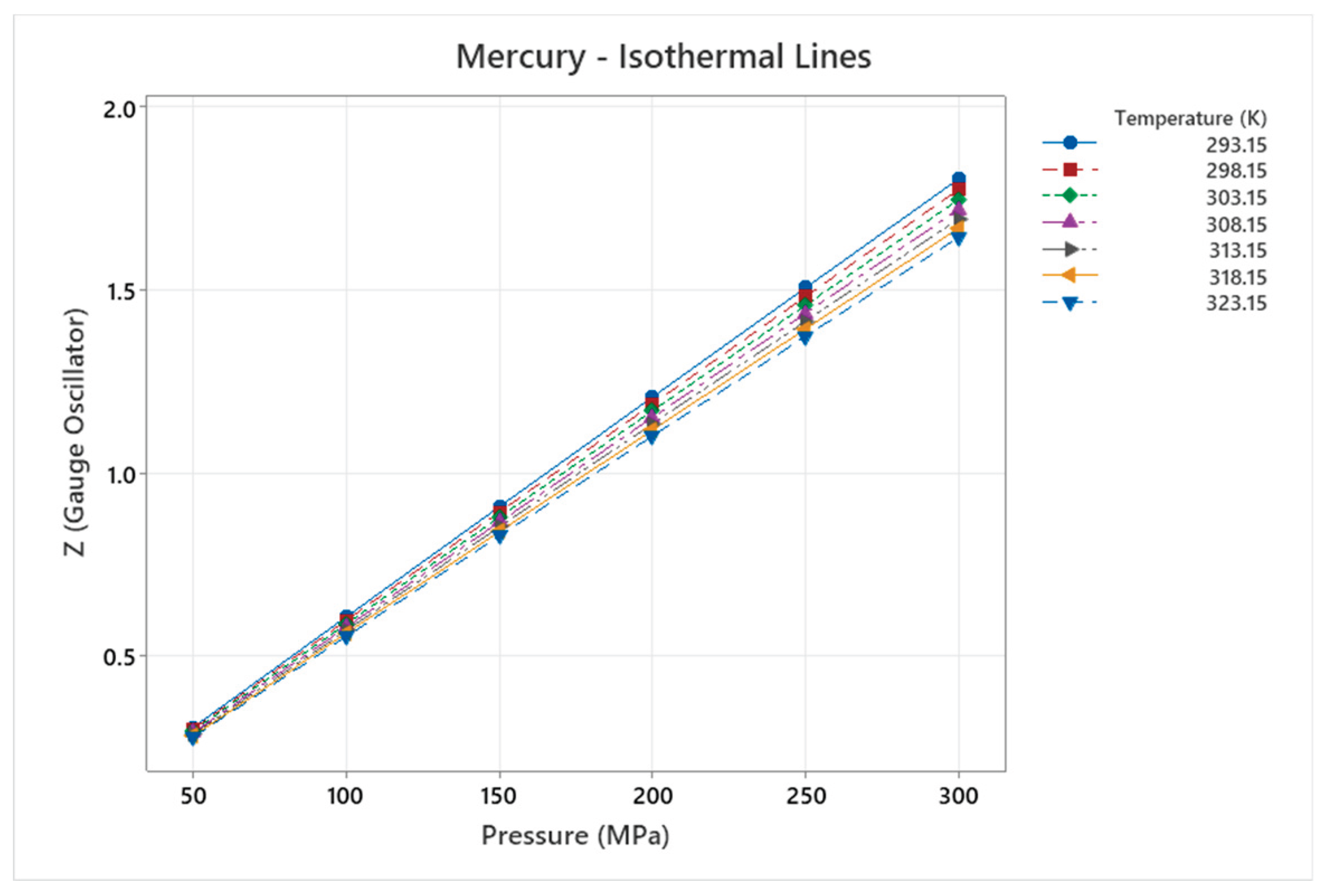

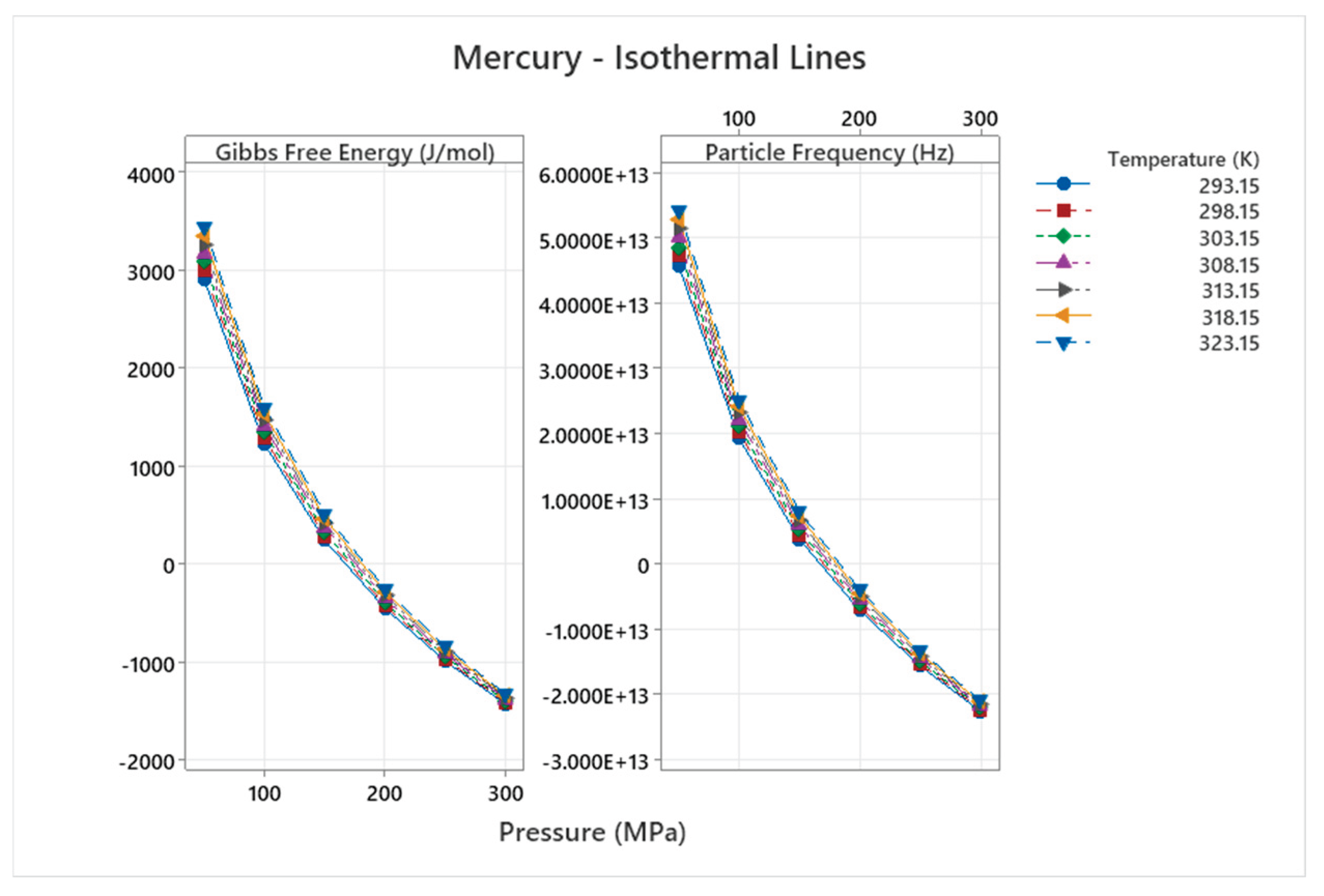

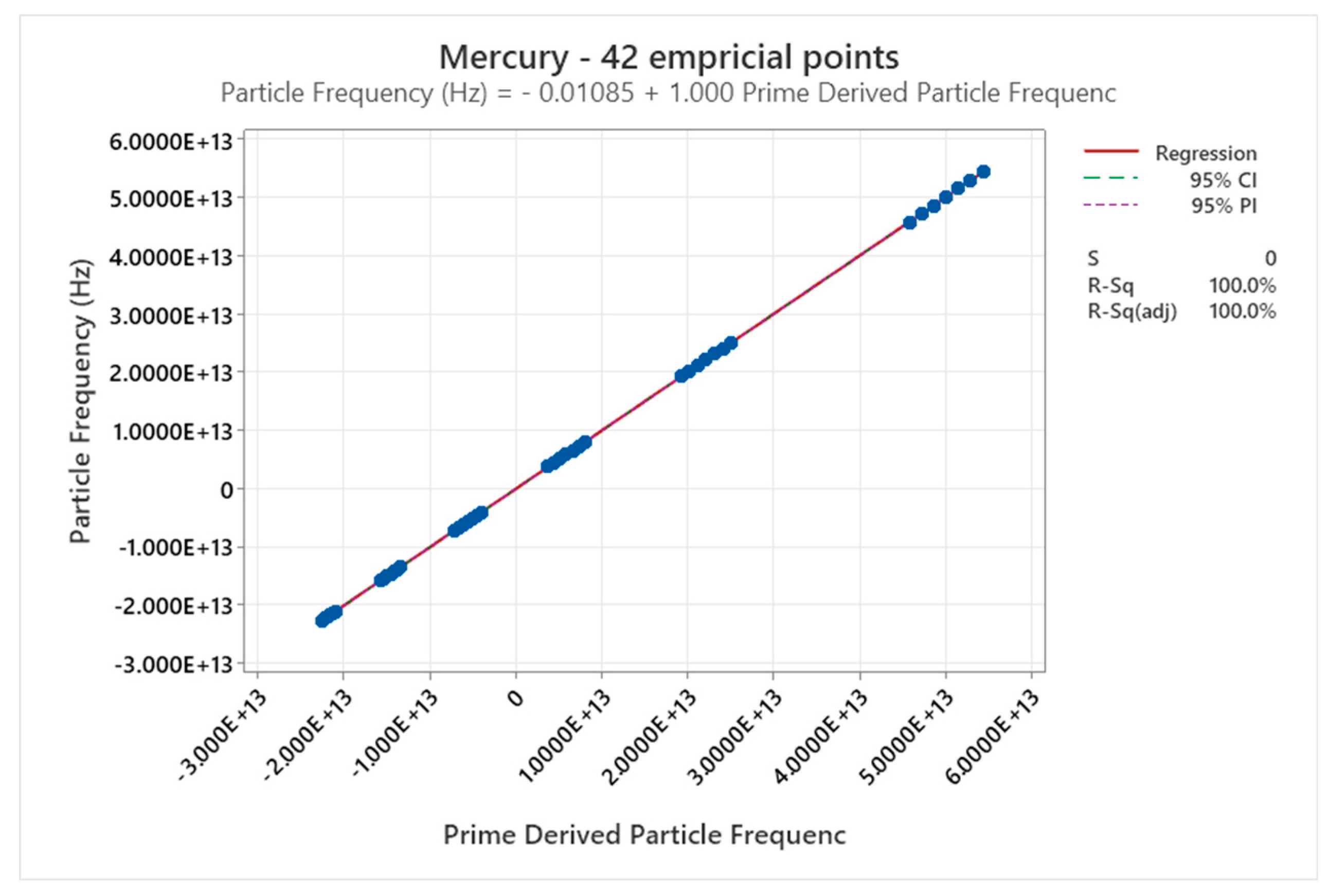

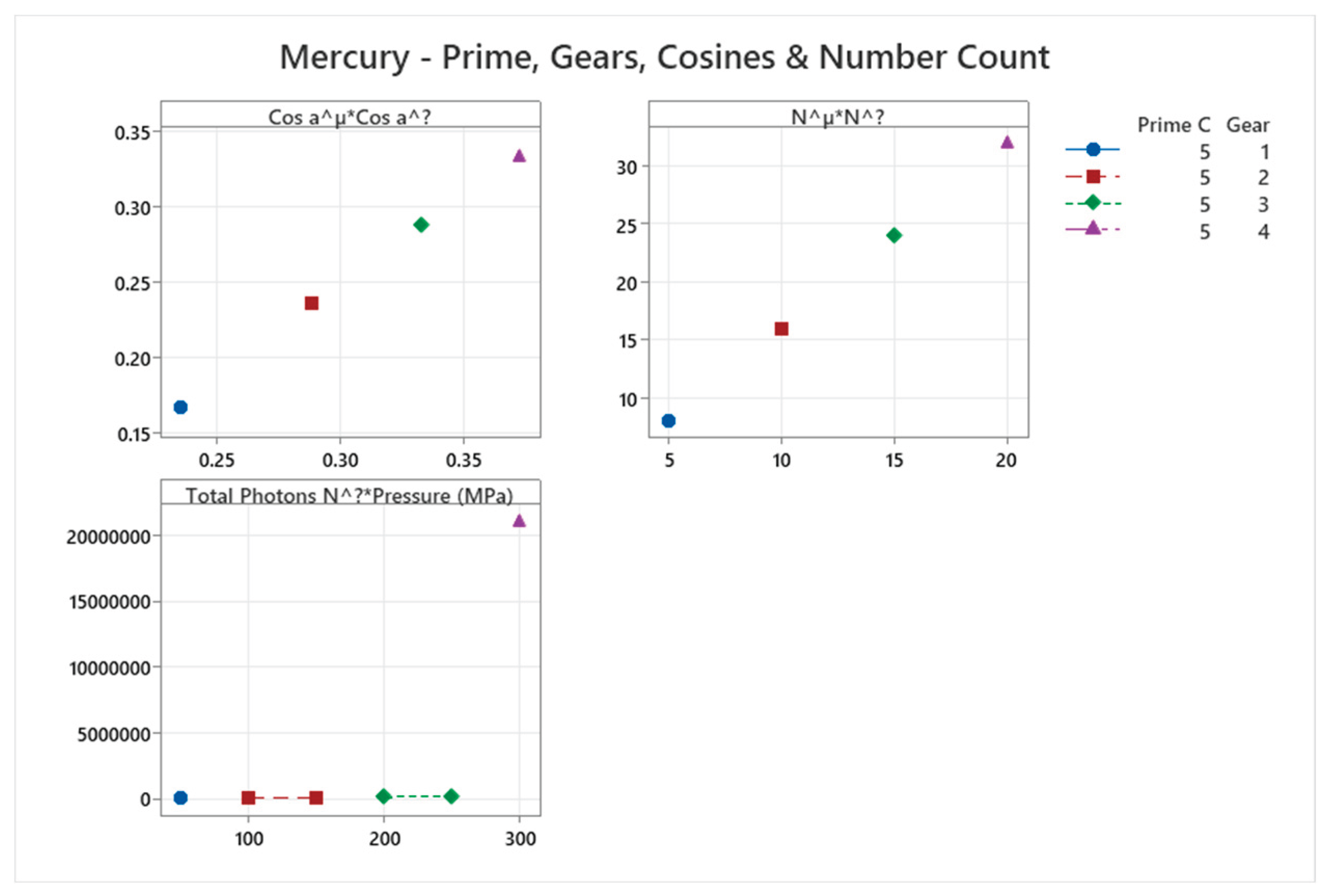

4.9. Mercury Phase Diagram

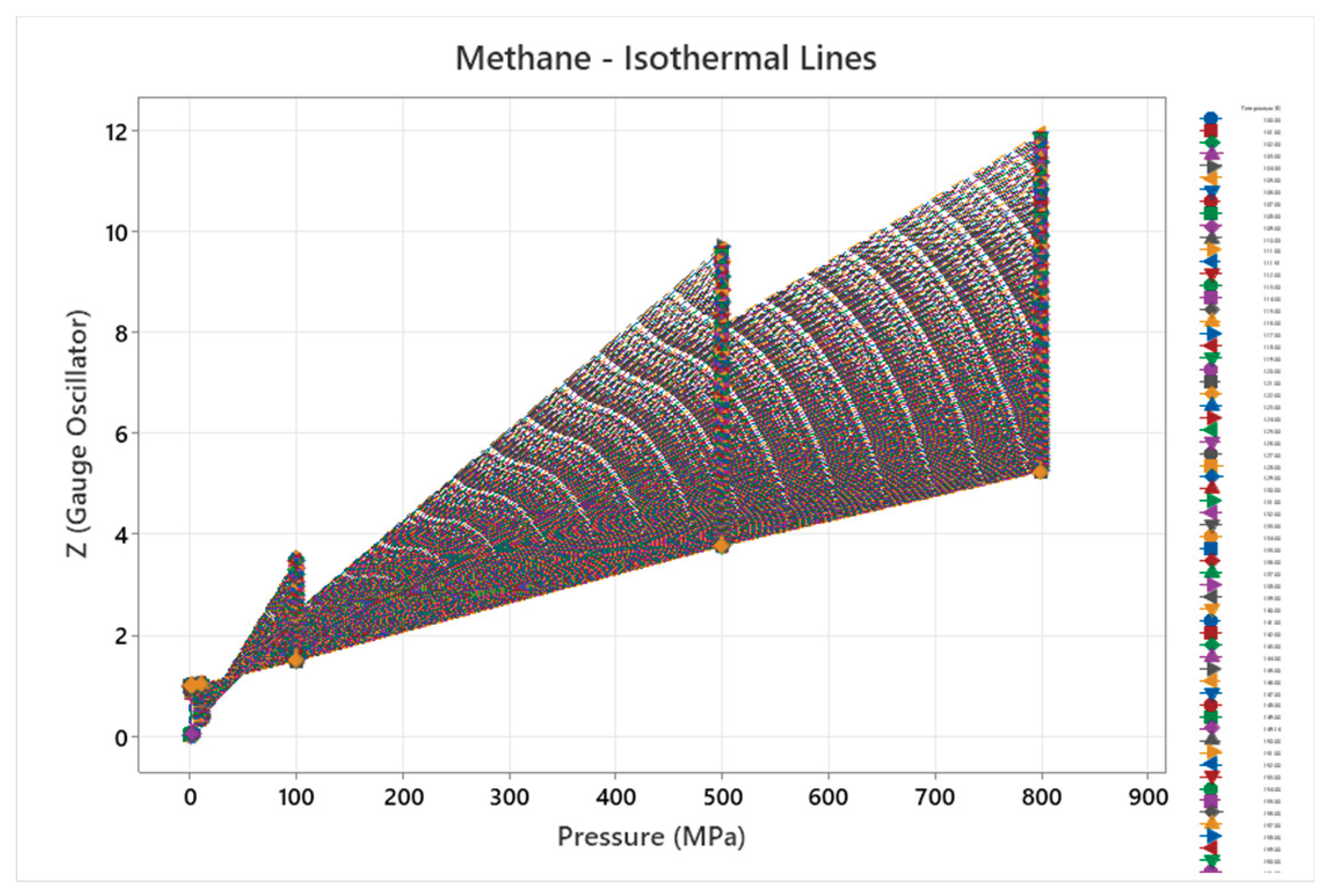

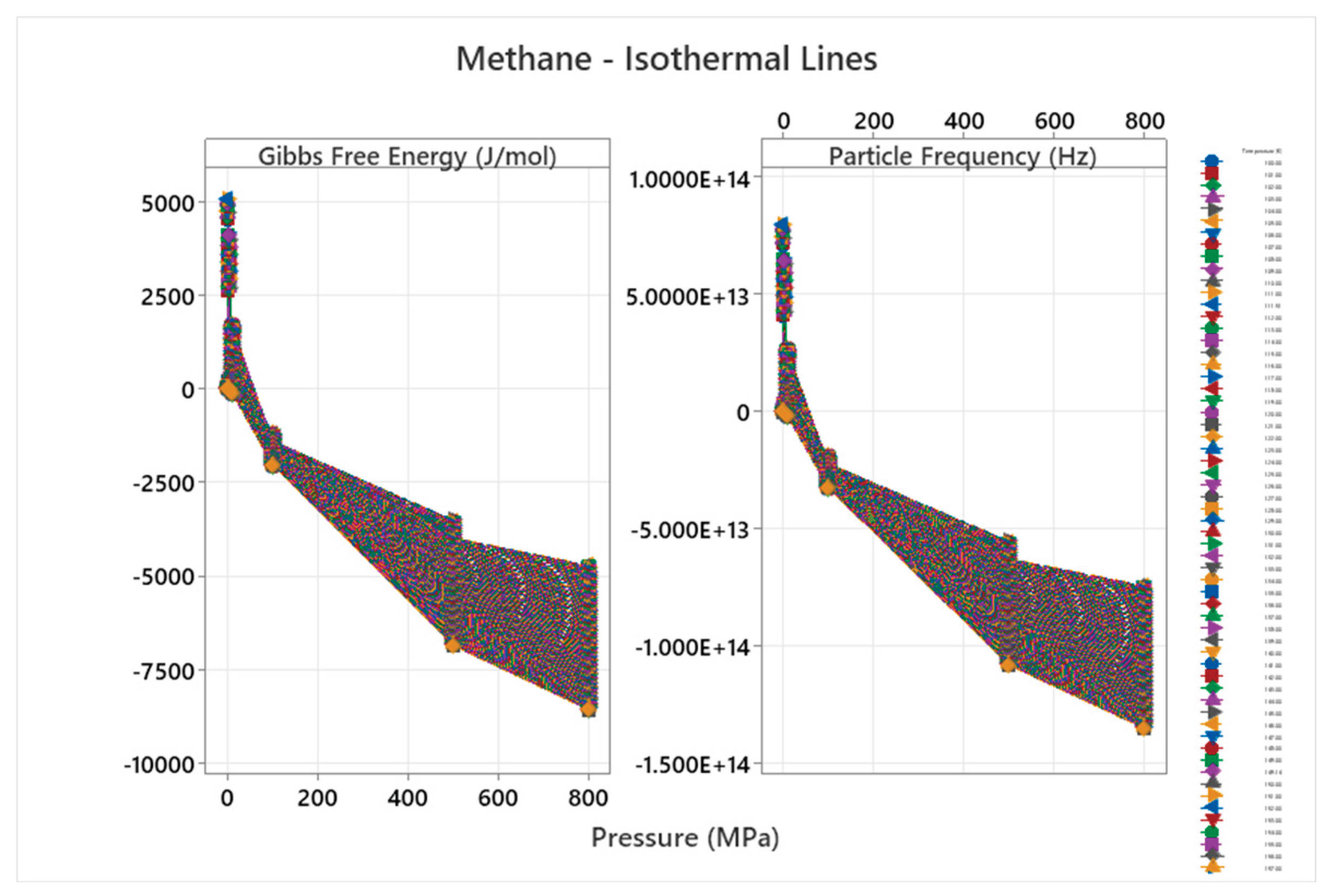

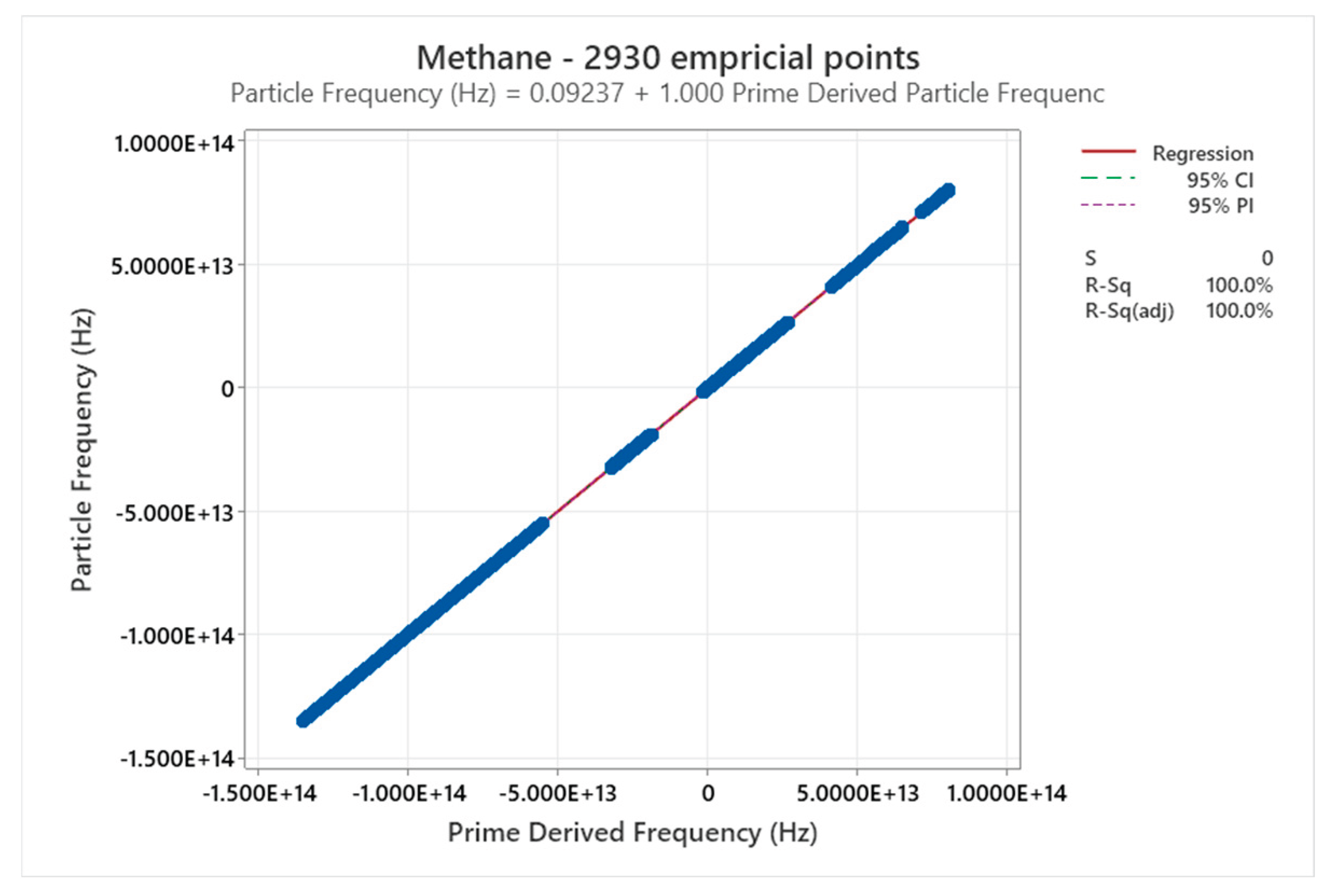

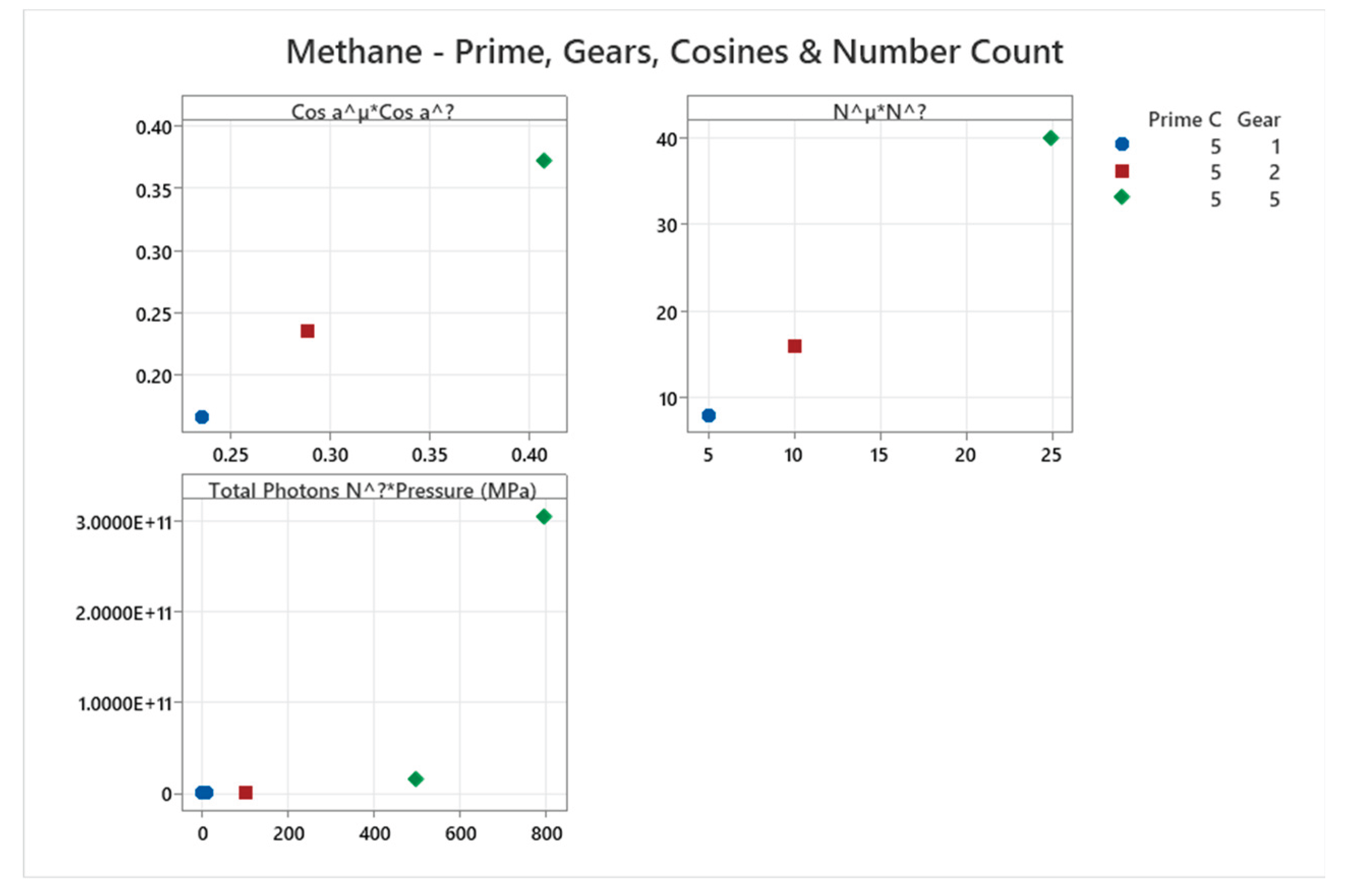

4.10. Methane Phase Diagram

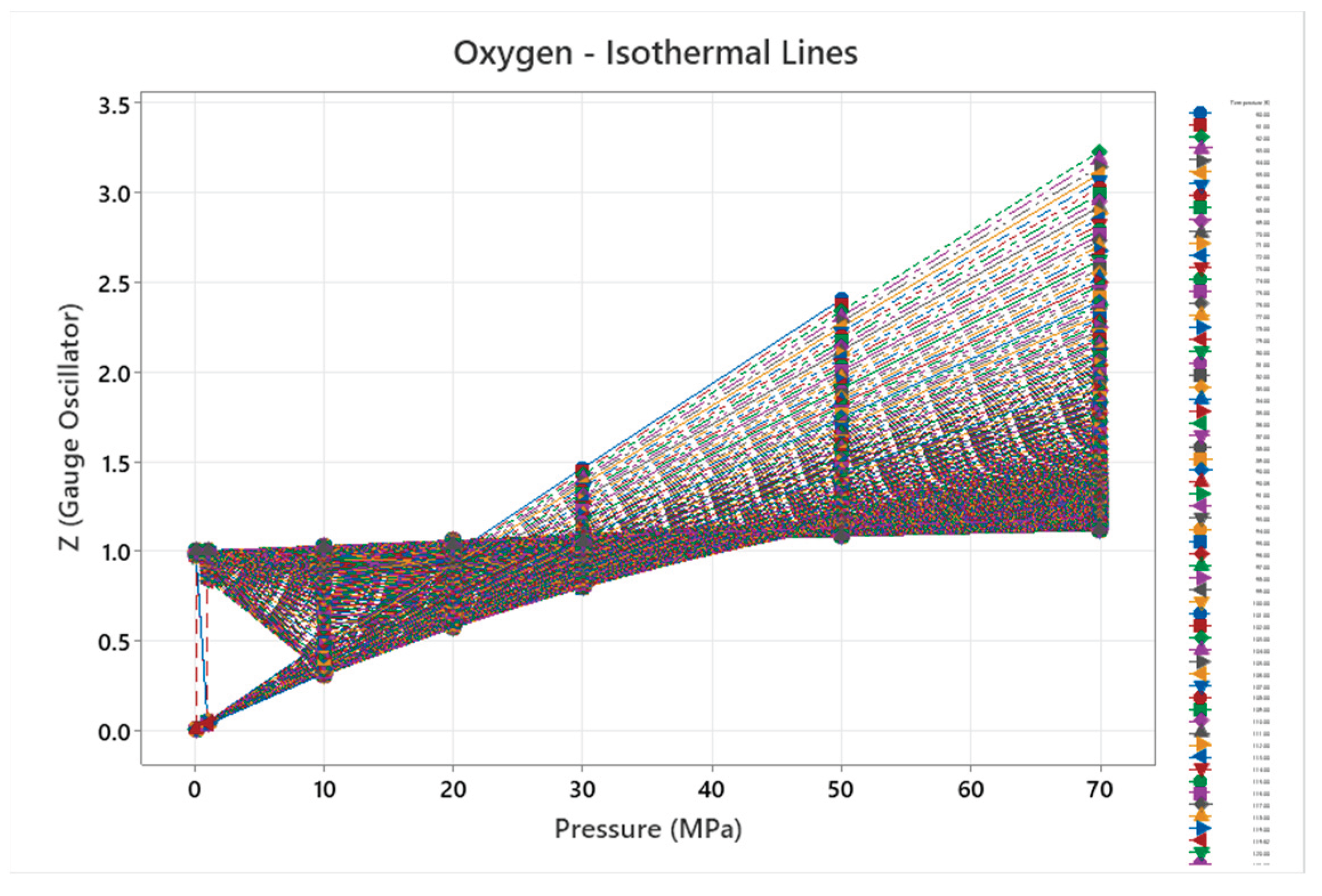

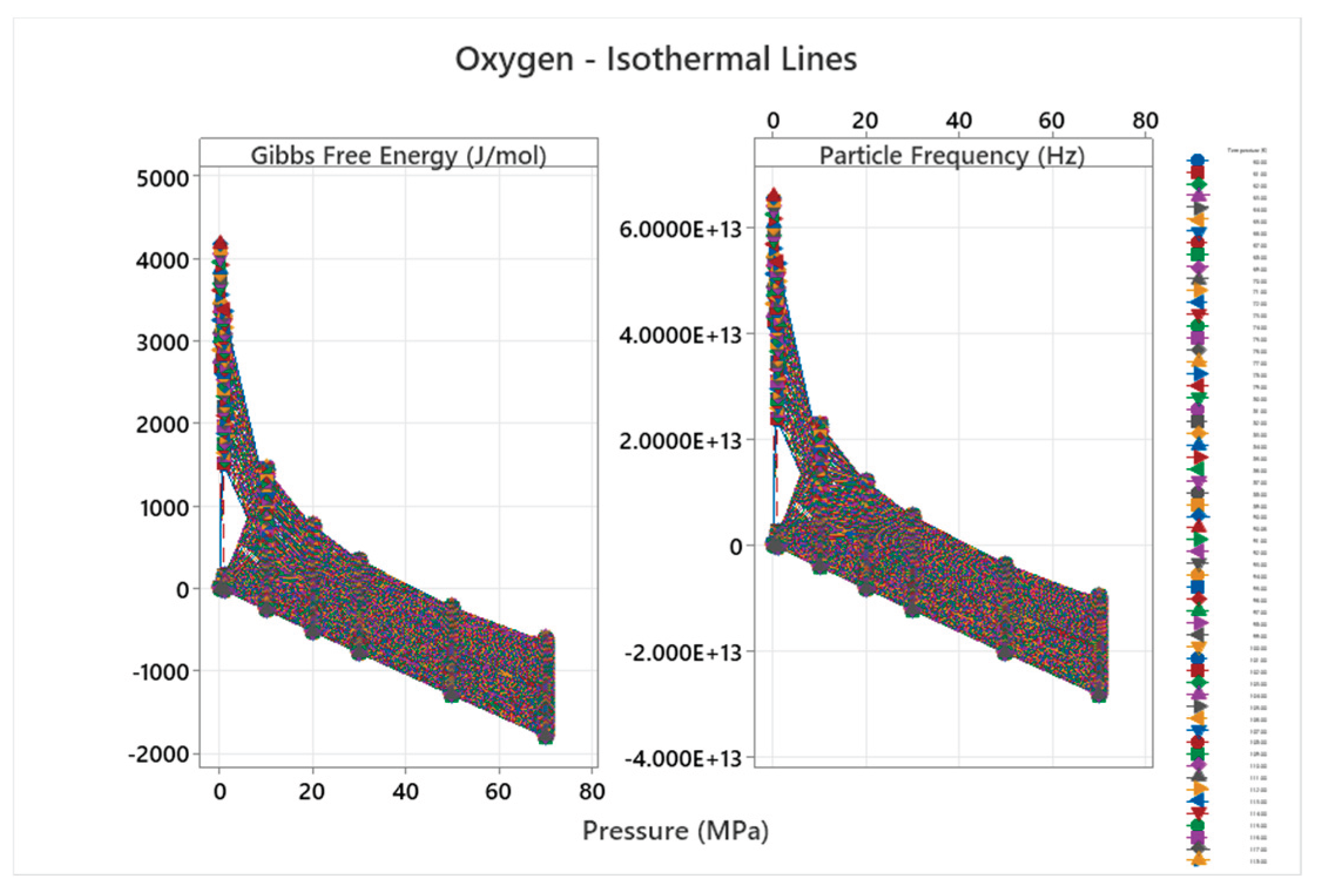

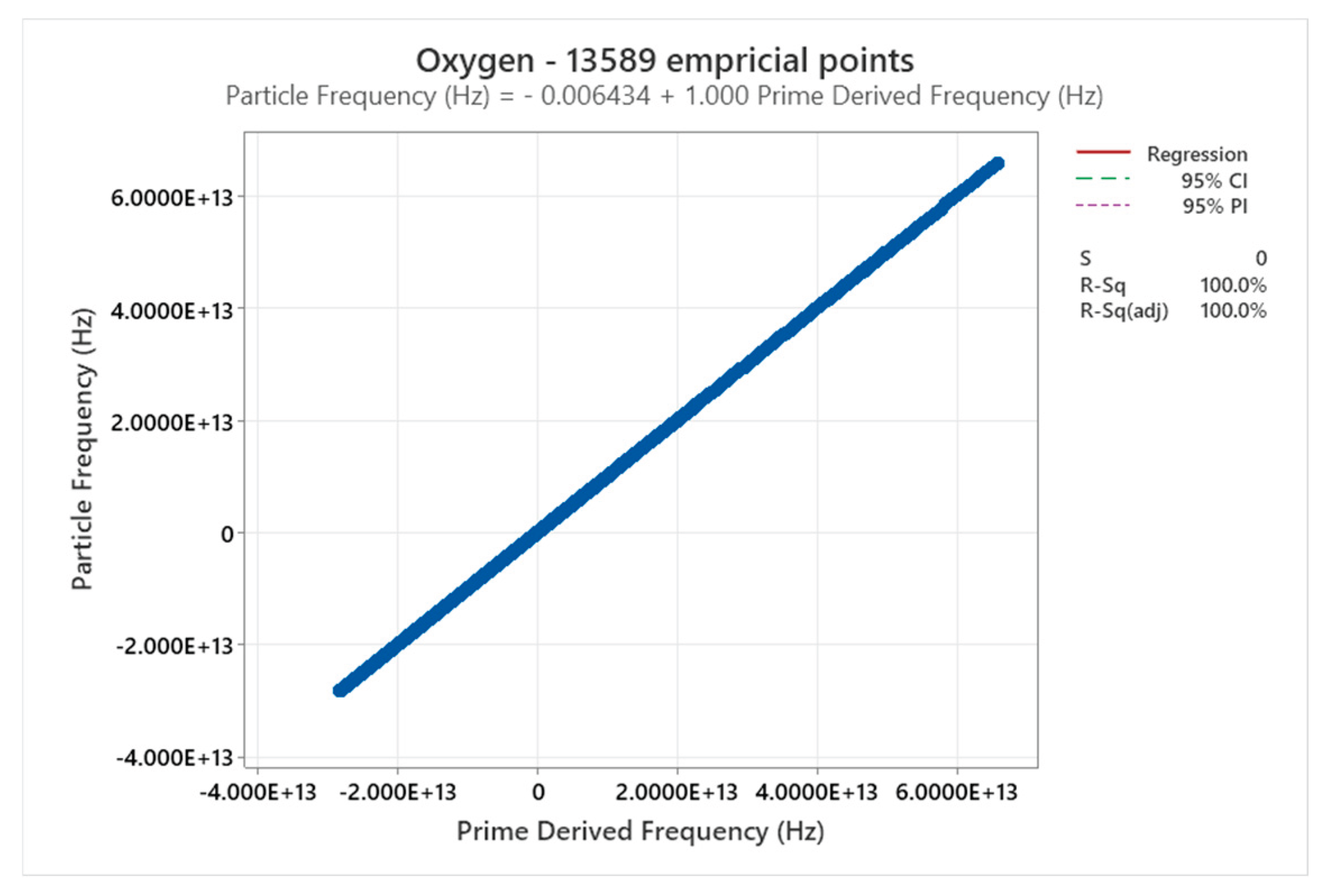

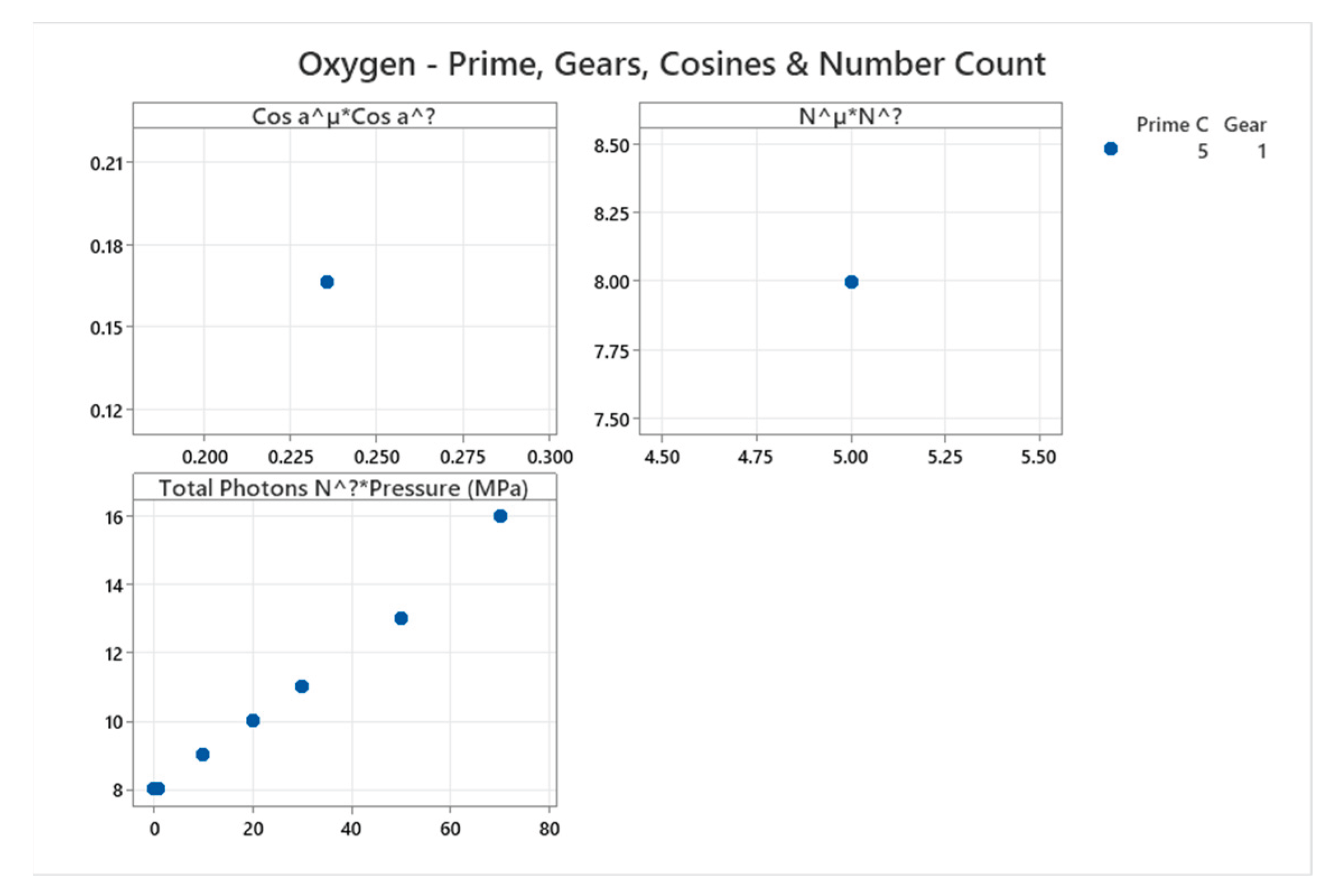

4.11. Oxygen Phase Diagram

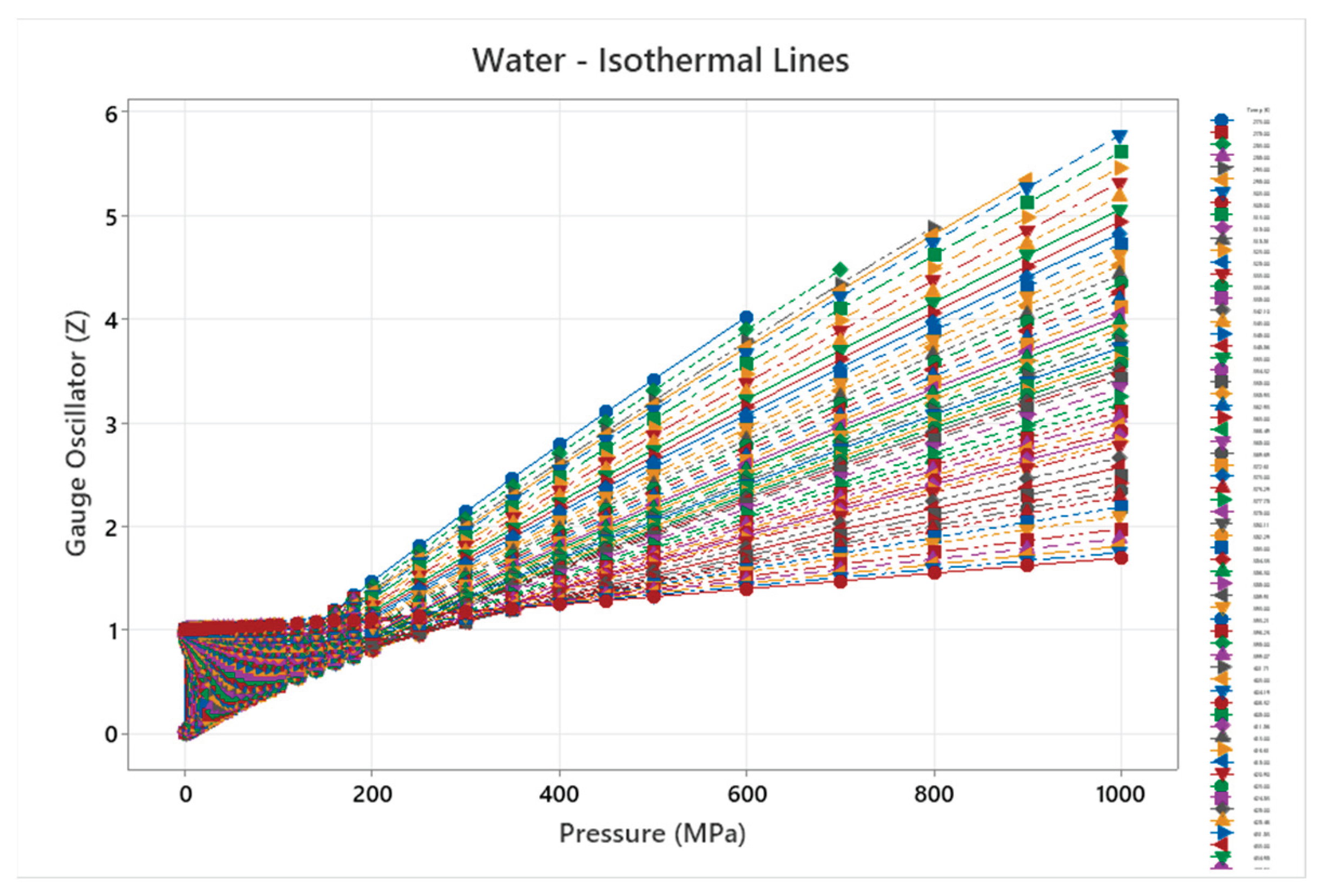

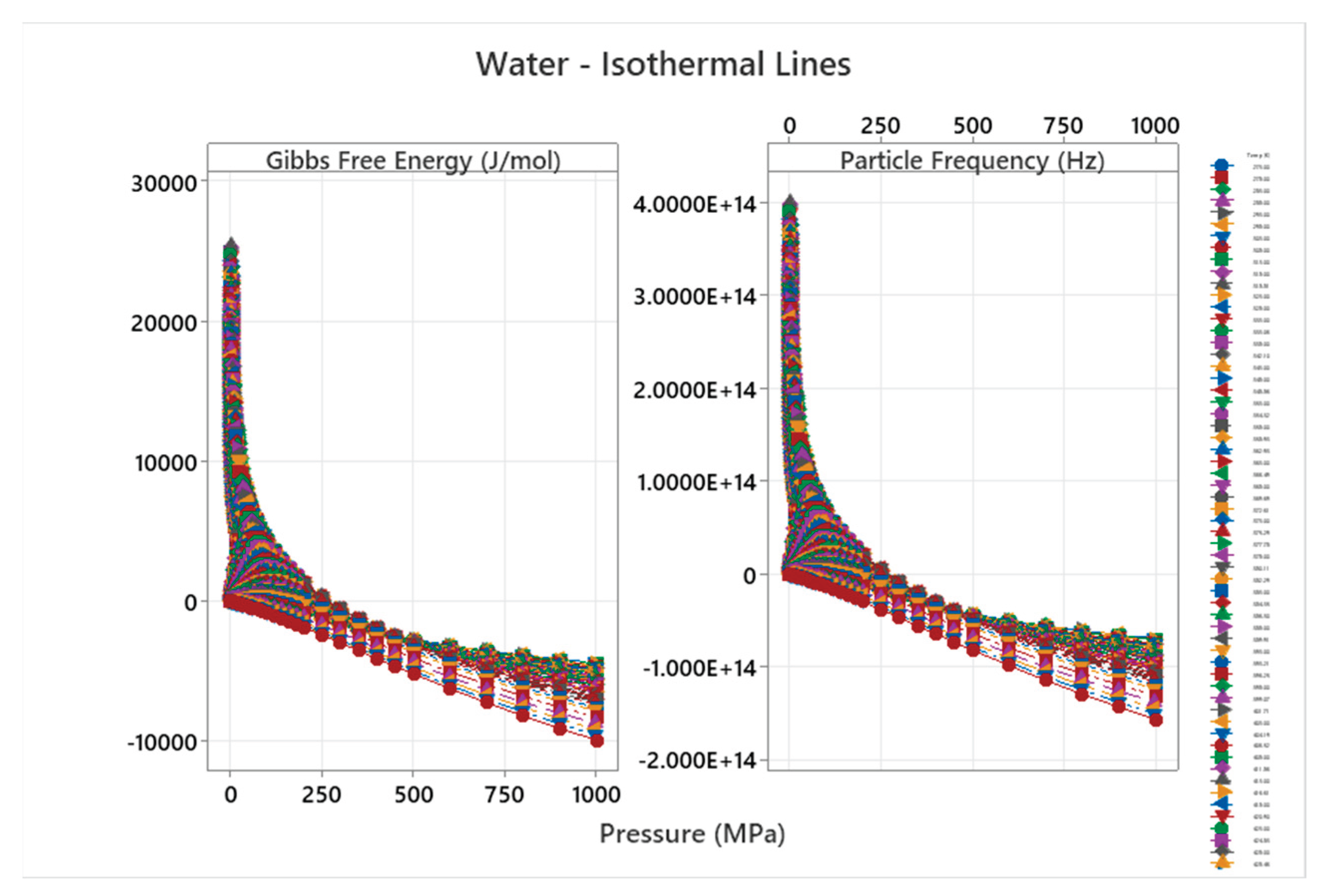

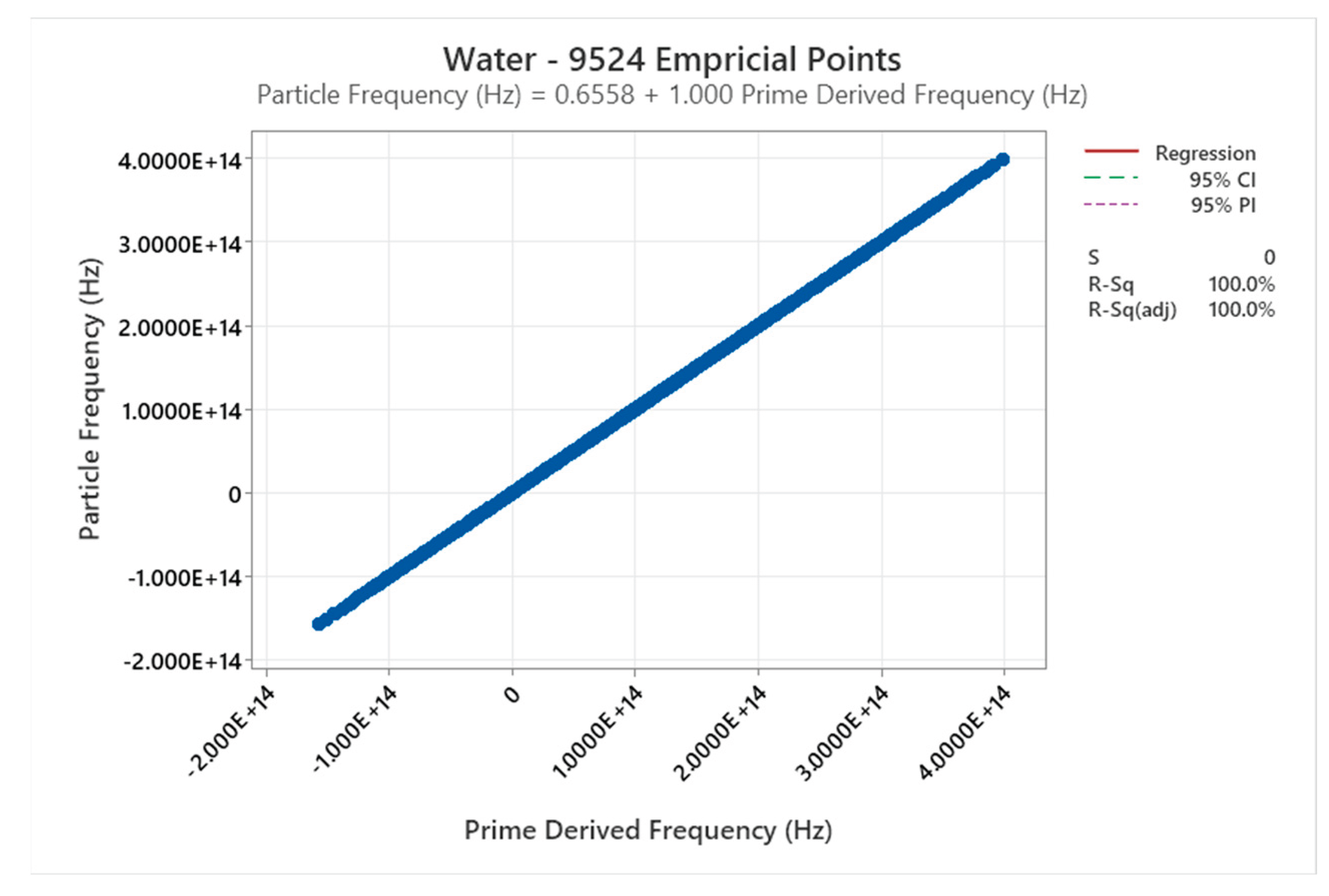

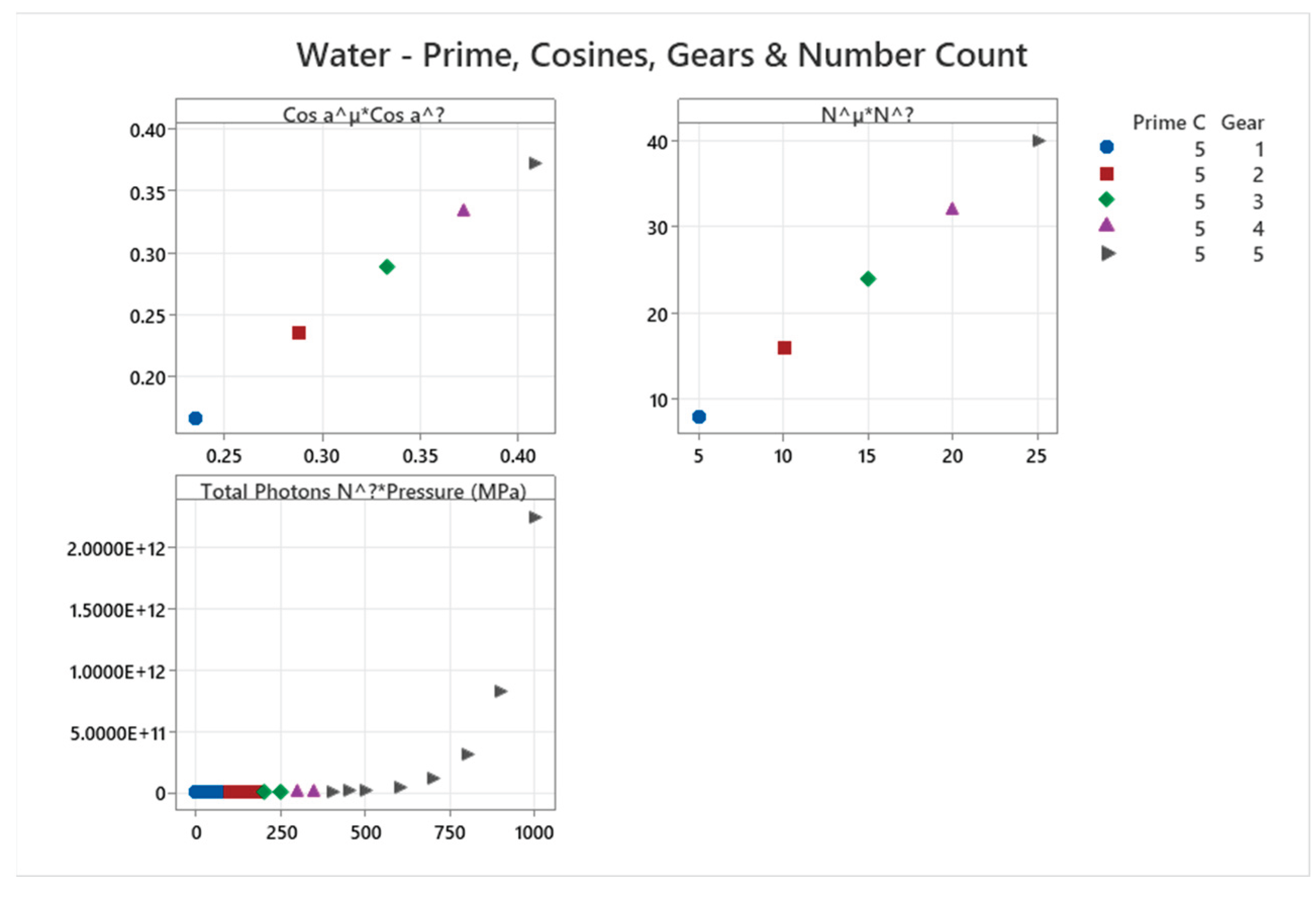

4.12. Water Phase Diagram

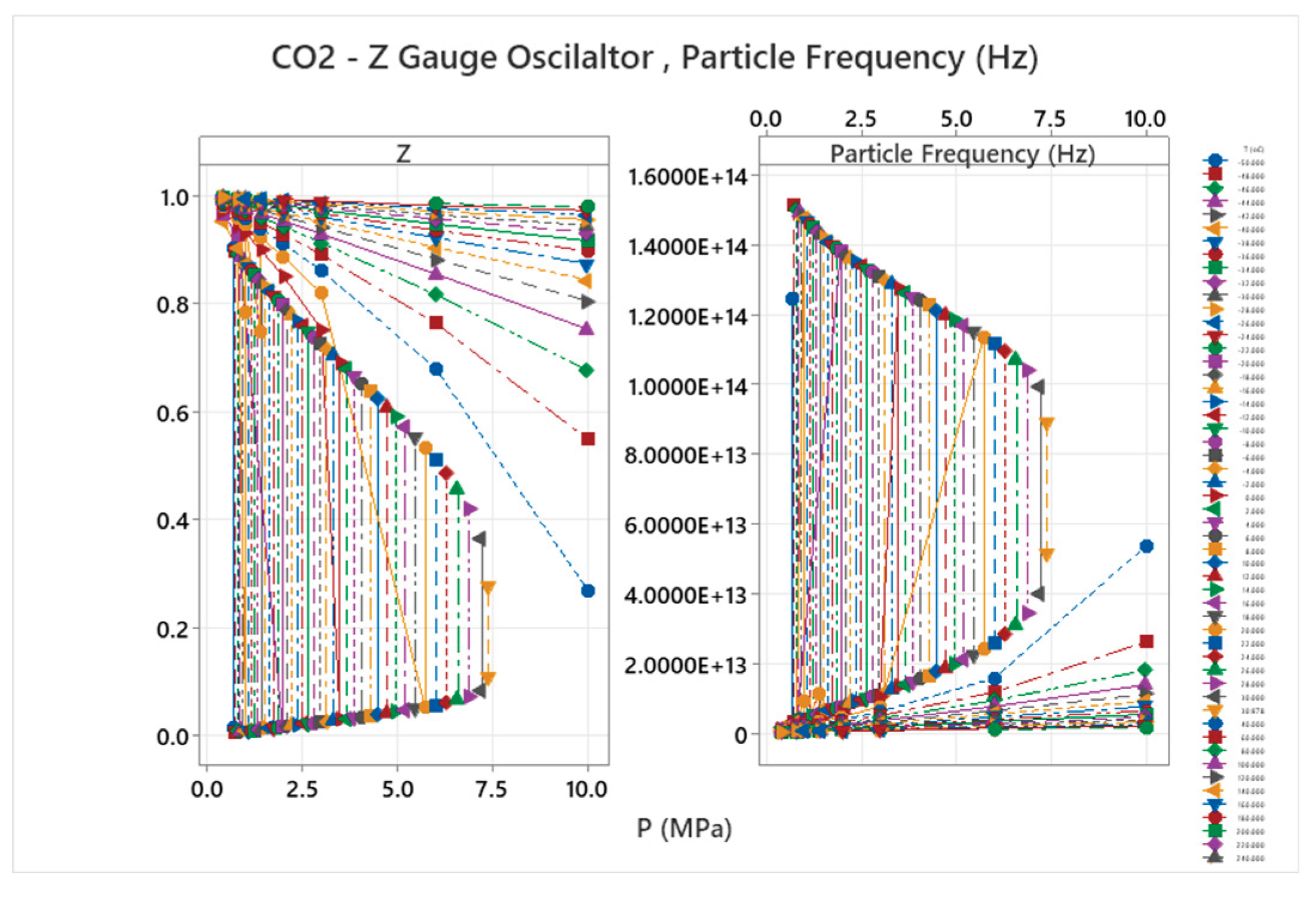

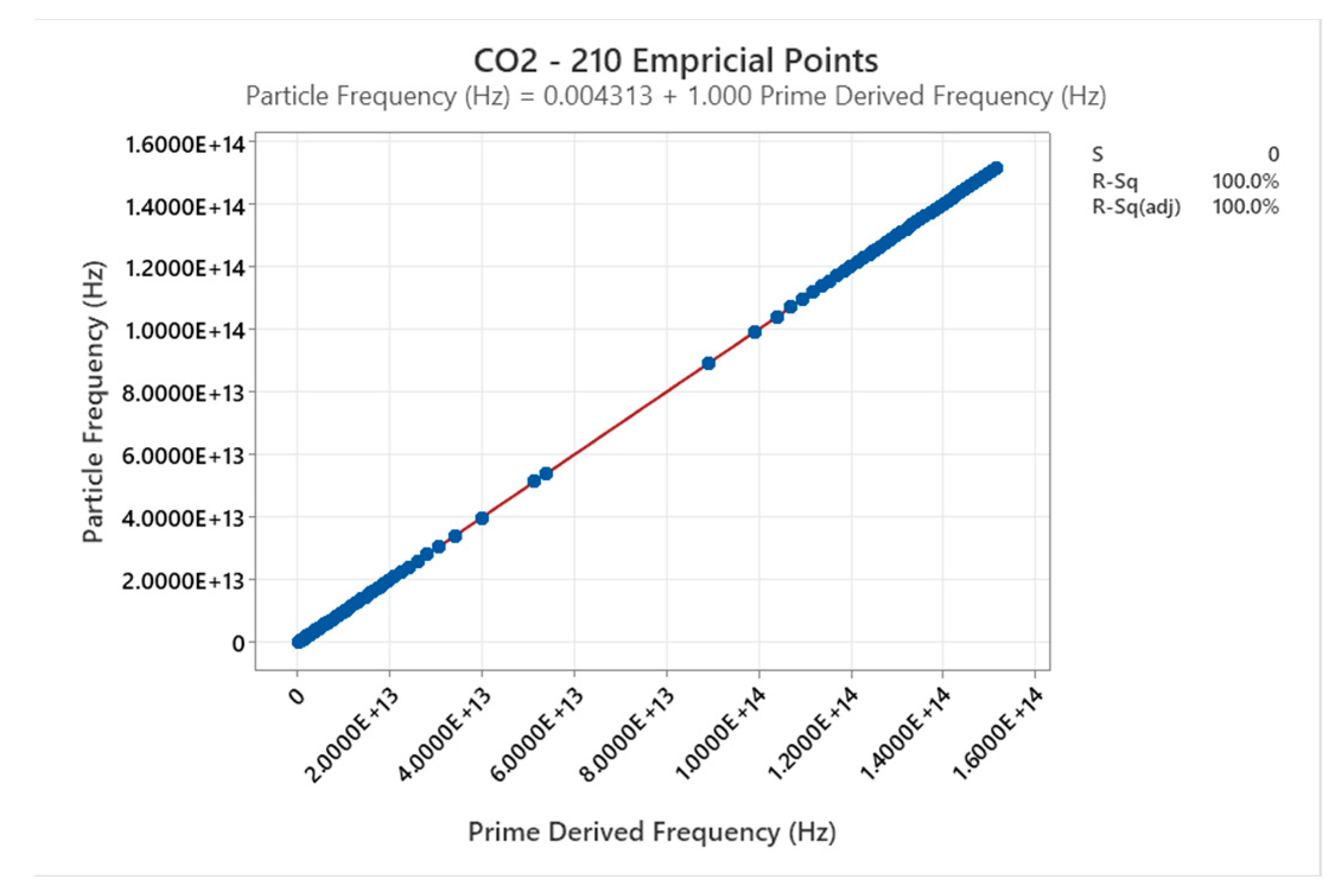

4.13. Carbon Dioxide Phase Diagram

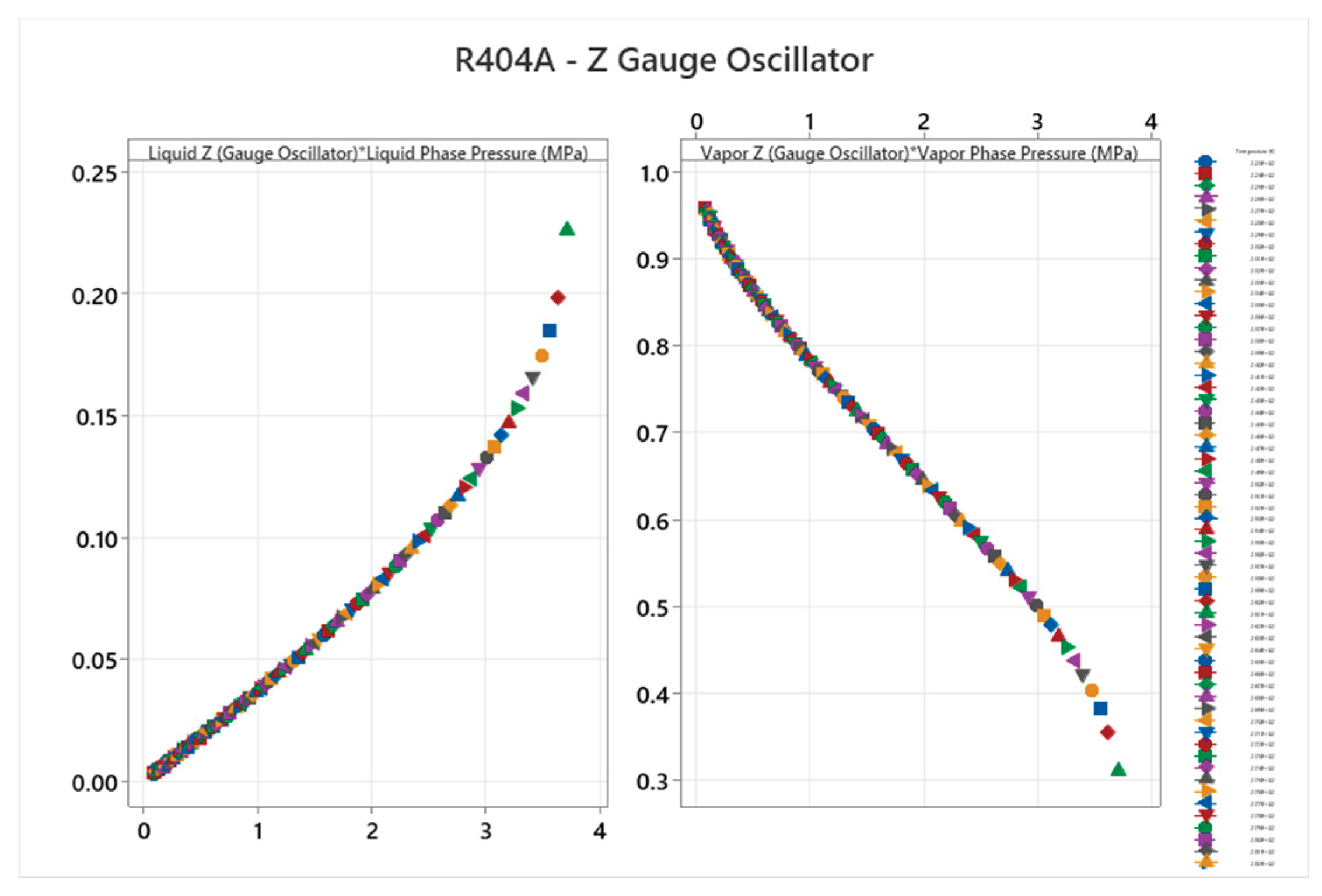

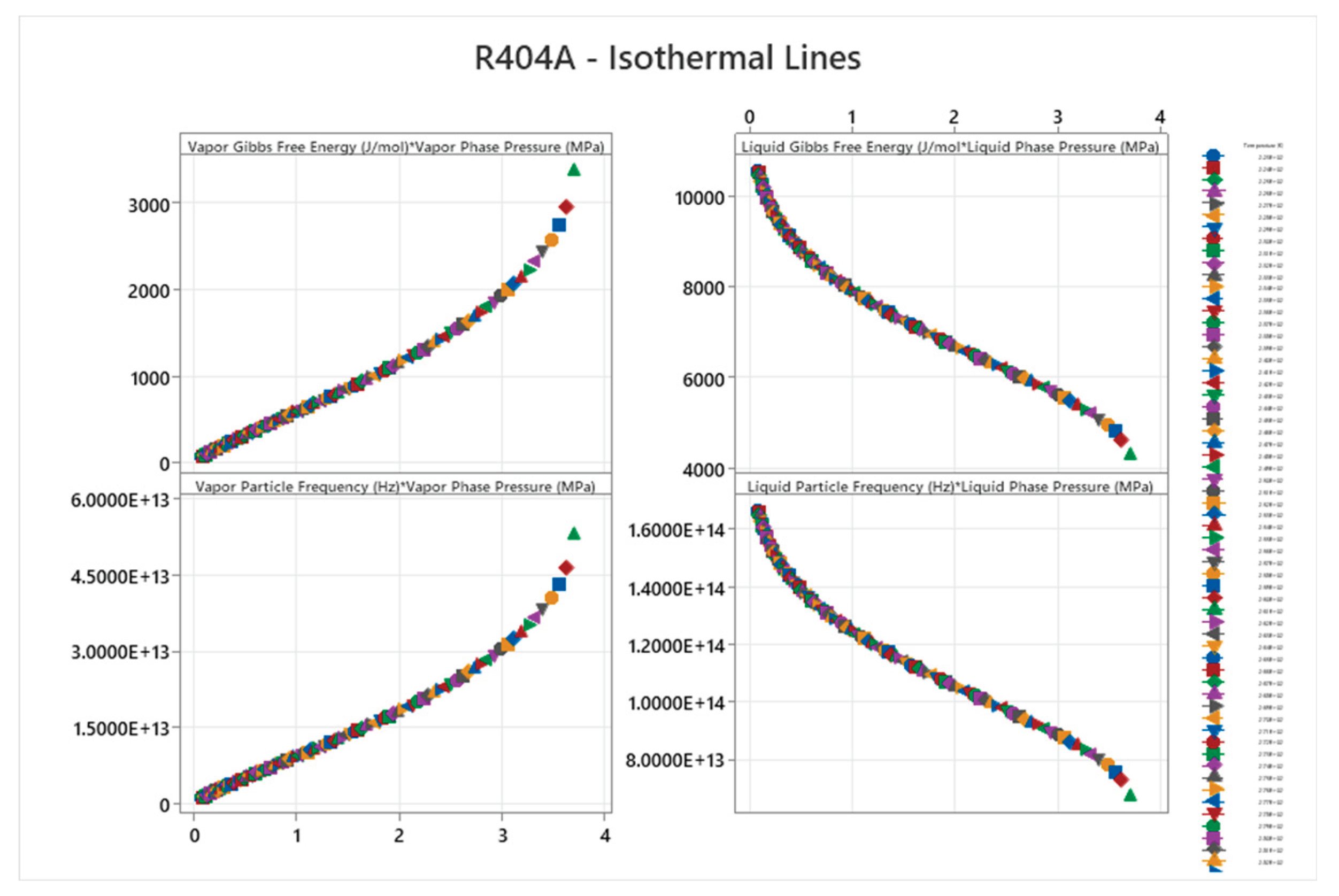

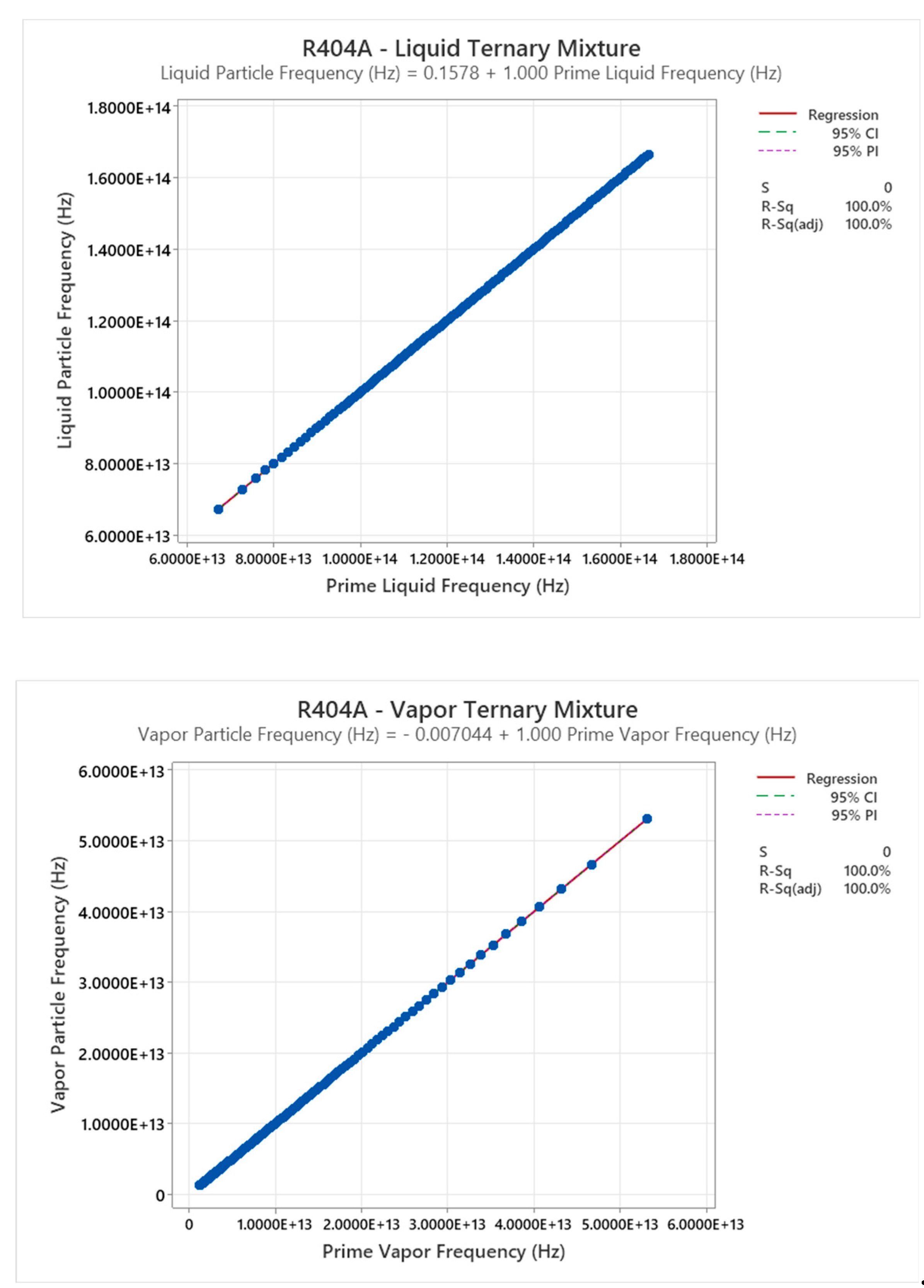

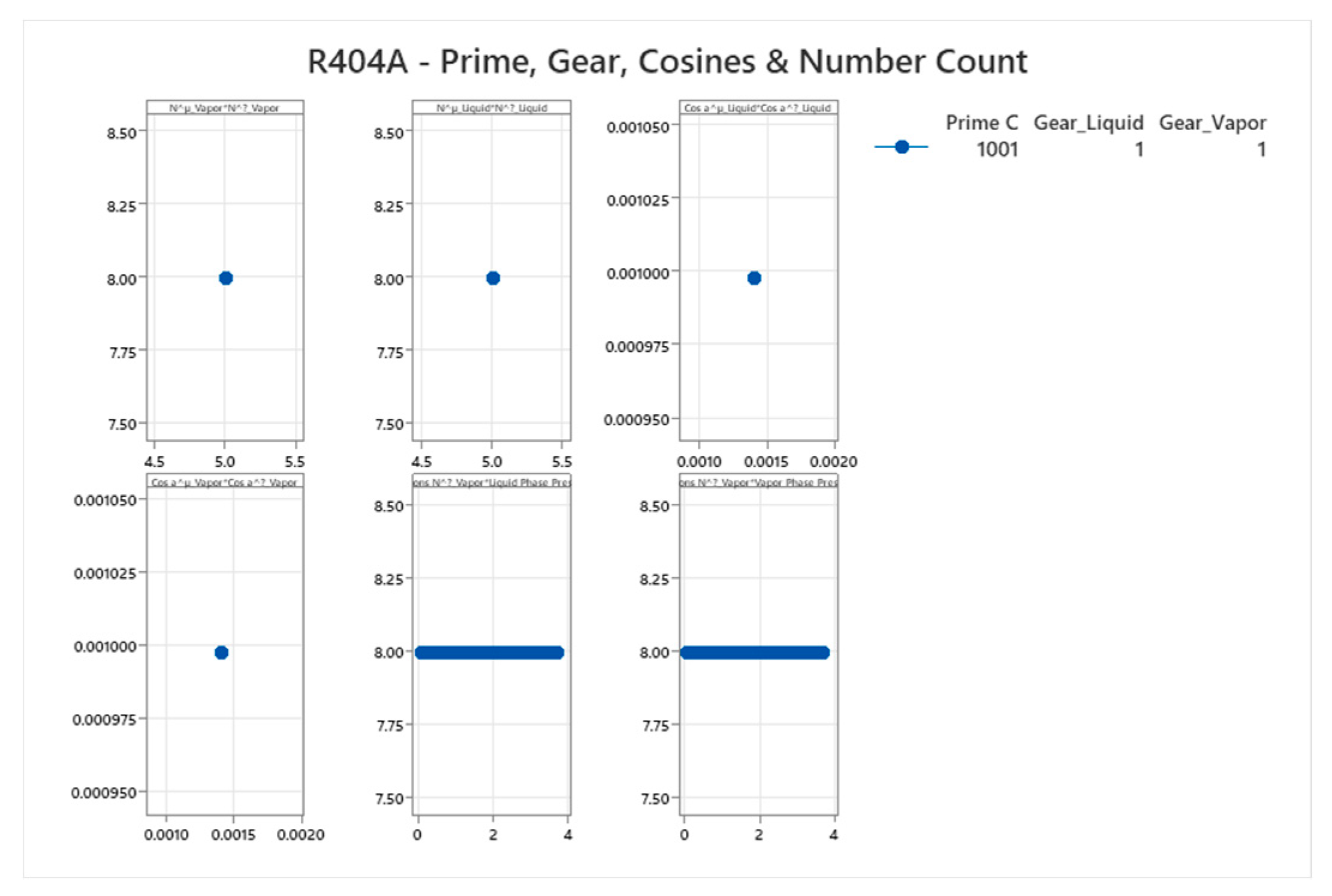

4.14. R404A Phase Diagram

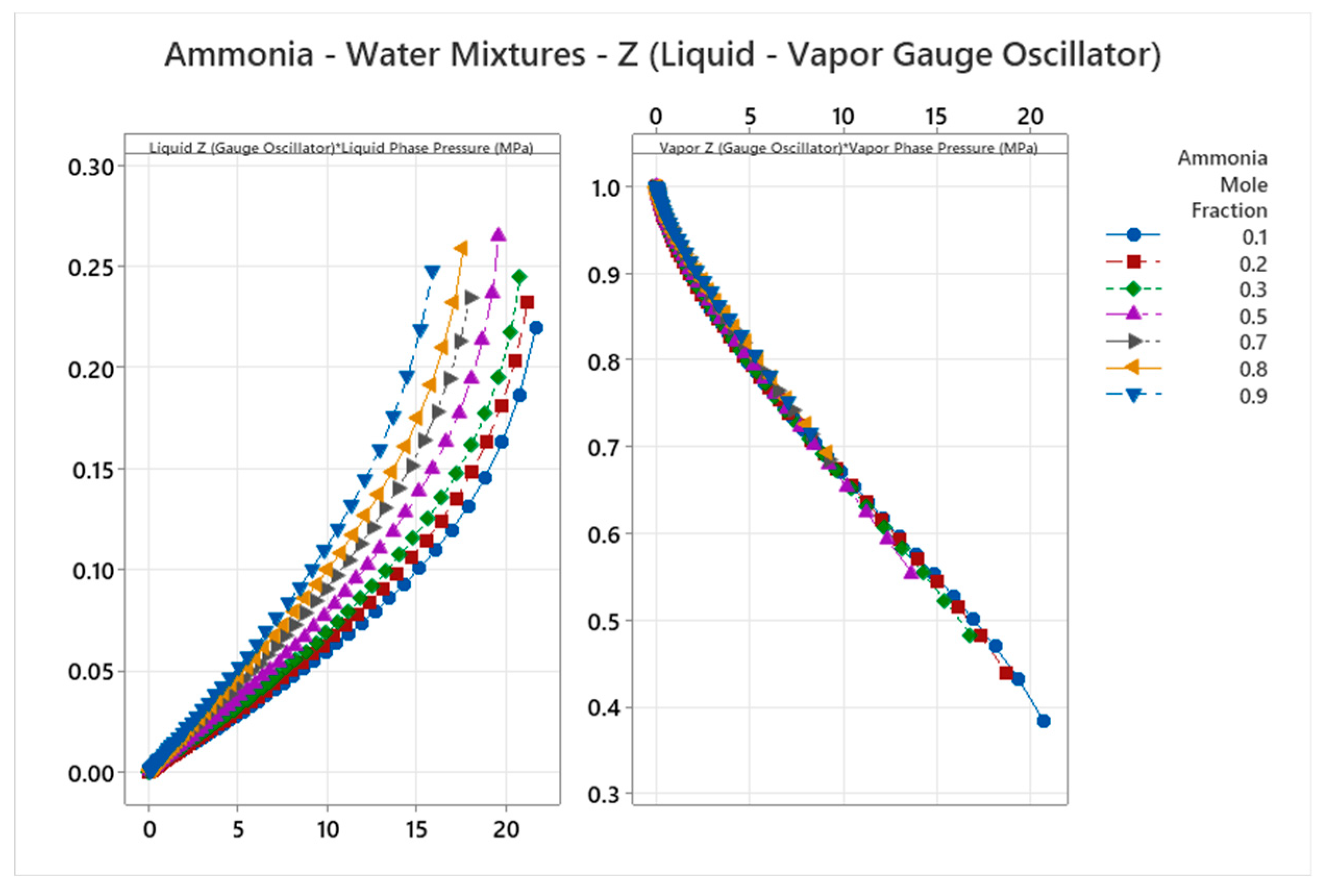

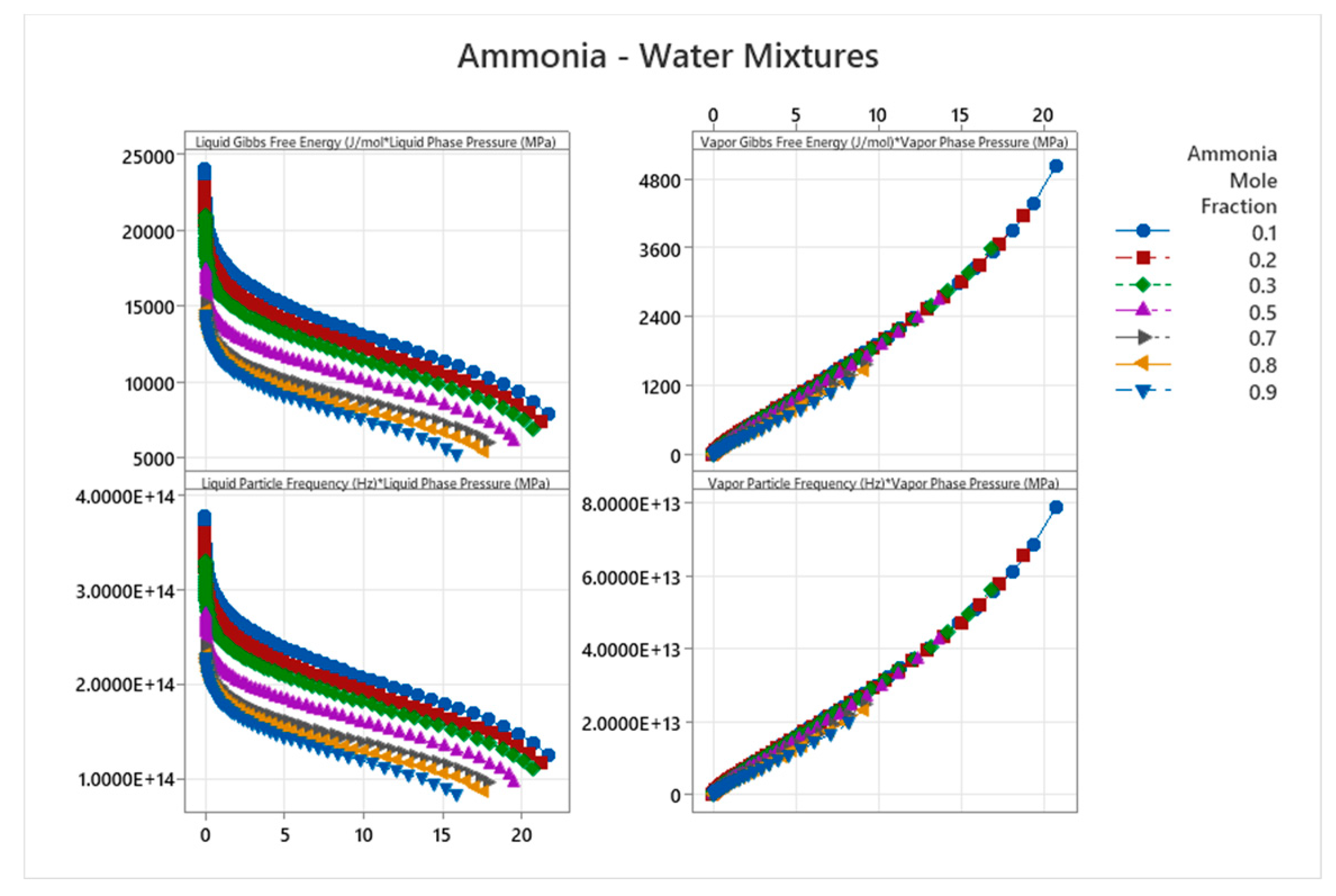

4.15. Ammonia-Water Mixture Phase Diagram

5. Discussion

| Component | Prime C | Gears Used | Cosines Examples (for Gear=1) | Literature Notes (Confirming Complexity) |

| Helium | 2 | 1-2 | = 1/3 ≈0.333, = √2/3 ≈0.471 | Helium has minimal phases (gas, liquid, superfluid); no solid-liquid-vapor triple point; simplest noble gas diagram[41,42] |

| Neon | 2 | 1-2 | = 1/3 ≈0.333, = √2/3 ≈0.471 | Neon shows simple fcc/hcp solid phases; low complexity similar to helium [43,44] |

| Argon | 2 | 1-2 | = 1/3 ≈0.333, = √2/3 ≈0.471 | Argon has straightforward phase diagram with fcc solid; minimal transitions among nobles[45,46] |

| Krypton | 2 | 1-2 | = 1/3 ≈0.333, cos α^η = √2/3 ≈0.471 | Krypton exhibits simple phase behavior with fcc solid; complexity increases slightly with atomic mass but remains low [47,48] |

| Xenon | 2 | 1-2 | = 1/3 ≈0.333, = √2/3 ≈0.471 | Xenon has a basic phase diagram with fcc solid; higher pressure phases but overall minimal complexity for nobles[49,50] |

| Mercury | 5 | 1-5 | = 1/6 ≈0.167, = √2/6 ≈0.236 | Mercury shows complex high-pressure phases (e.g., with Fe-FeSi-like diagram); unique liquid metal at ambient, anomalous behaviors [51,52] |

| Methane | 5 | 1,2,5 | = 1/6 ≈0.167, = √2/6 ≈0.236 | Methane has a phase diagram with critical point and solid polymorphs; moderate complexity for hydrocarbons [53,54] |

| Oxygen | 5 | 1 (stuck) | = 1/6 ≈0.167, = √2/6 ≈0.236 | Oxygen exhibits multiple solid phases and reactivity; complex diagram for diatomic gas [55,56] |

| Ammonia-Water | 15 | 1-15 | Weighted averages; e.g., for Gear=1: mixed cos ~0.25 | Ammonia-water forms maximum-boiling azeotrope with complex VLE; strong interactions and buffering[57,58] |

| R404A (ternary) | 1001 | 1-1001 | Weighted averages; e.g., for Gear=1: mixed cos ~0.001 | R404A has near-azeotropic behavior with small glide; complex ternary for refrigeration[59,60] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Van der Waals, J. D. (1873). Over de Continuïteit van den Gas- en Vloeistoftoestand [Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University]. Sijthoff.

- Baehr, H. D., & Kabelac, S. (2009). Thermodynamik: Grundlagen und technische Anwendungen (14th ed.). Springer.

- Dieterici, C. (1899). Über das Verhalten der Gase in der Nähe des kritischen Punktes. Annalen der Physik, 305(12), 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Kamerlingh Onnes, H. (1901). Expression of the equation of state of gases and liquids by means of series. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 4, 125–147.

- Redlich, O., & Kwong, J. N. S. (1949). On the thermodynamics of solutions. V. An equation of state. Fugacities of gaseous solutions. Chemical Reviews, 44(1), 233–244. [CrossRef]

- Soave, G. (1972). Equilibrium constants from a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state. Chemical Engineering Science, 27(6), 1197–1203. [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.-Y., & Robinson, D. B. (1976). A new two-constant equation of state. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Fundamentals, 15(1), 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, M. S. (1984). Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. I. Statistical thermodynamics. Journal of Statistical Physics, 35(1-2), 19–34. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W., & Pruß, A. (2002). The IAPWS formulation 1995 for the thermodynamic properties of ordinary water substance for general and scientific use. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 31(2), 387–535. [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, M. (2008). Water Structure and Science: Anomalies of Water. London South Bank University. Retrieved from https://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/water_anomalies.html.

- Gross, D. H. E. (2001). Microcanonical Thermodynamics: Phase Transitions in "Small" Systems. World Scientific. (Chapter on PC-SAFT; full book).

- Huygens, C. (1690). Traité de la lumière. Pierre vander Aa, Leiden.

- Fresnel, A. (1818). Mémoire sur la diffraction de la lumière. Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 11, 239–281.

- Maxwell, J. C. (1865). A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 155, 459–512. [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. (1901). Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum. Annalen der Physik, 309(3), 553–563. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1905). Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt. Annalen der Physik, 322(6), 132–148. [CrossRef]

- de Broglie, L. (1924). Recherches sur la théorie des quanta [Doctoral dissertation, University of Paris]. Published in Annales de Physique (10e série), 3, 22–128 (1925). [CrossRef]

- Davisson, C., & Germer, L. H. (1927). Diffraction of electrons by a crystal of nickel. Physical Review, 30(6), 705–740. [CrossRef]

- Linstrom, P. J., & Mallard, W. G. (Eds.). (n.d.). NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved December 01, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ (DOI: 10.18434/T4D303; last update March 2025).

- Fouad, M. F. (2025). Thermodynamic unified field theory: Emergent unification of fundamental forces via photrino composites and entropy maximization. Applied Physics Research, 17(2), 198. [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M. F. (2025). Covariant fugacity-Hessian symmetry constraints: A unified derivation of heat, mass, and momentum transport with applications to catalytic effectiveness factors [Preprint]. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M. (2025). Helical triad quantization: Covariant fugacity constraints unifying catalysis, superfluidity, and phase behaviors via primes [Preprint]. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E. W., Bell, I. H., Huber, M. L., & McLinden, M. O. (2023). NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP, Version 10.0. National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://www.nist.gov/srd/refprop.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. U.S. Department of Commerce.

- Lemmon, E. W., & Jacobsen, R. T. (2004). Equations of state for mixtures of R-32, R-125, R-134a, R-143a, and R-152a. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 33(2), 593–620. (Note: While for mixtures, it includes neon references; for pure neon, use WebBook.). [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Neon. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7440019.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Mercury. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7439976.

- Huber, M. L., Laesecke, A., & Perkins, R. A. (2003). Model for the viscosity and thermal conductivity of refrigerants, including a new correlation for the viscosity of R134a. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 42(13), 3163–3178. (Relevant for fluid properties; mercury-specific data in WebBook.). [CrossRef]

- Leachman, J. W., Jacobsen, R. T., Penoncello, S. G., & Lemmon, E. W. (2009). Fundamental equations of state for parahydrogen, normal hydrogen, and orthohydrogen. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 38(3), 721–748. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Hydrogen. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C1333740.

- Tillner-Roth, R., Harms-Watzenberg, F., & Baehr, H. D. (1993). An international standard formulation for the thermodynamic properties of ammonia. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 22(5), 1099–1121. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Ammonia. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7664417.

- Wagner, W., & Pruß, A. (2002). The IAPWS formulation 1995 for the thermodynamic properties of ordinary water substance for general and scientific use. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 31(2), 387–535. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Water. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7732185.

- Span, R., & Wagner, W. (1996). A new equation of state for carbon dioxide covering the fluid region from the triple-point temperature to 1100 K at pressures up to 800 MPa. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 25(6), 1509–1596. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Carbon dioxide. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C124389.

- Ortiz Vega, D. O. (2013). A new wide range equation of state for helium-4 (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Available from https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/149499.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Helium. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7440597.

- Tillner-Roth, R., & Friend, D. G. (1998). A Helmholtz free energy formulation of the thermodynamic properties of the mixture {water + ammonia}. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 27(1), 63–96. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). Ammonia-water mixtures. In NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Retrieved November 29, 2025, from https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/fluid/ (Search for ammonia + water).

- Kofler, L. (1950). The phase diagram of helium. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A, 5(4), 198-200. [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. E., & Swenson, C. A. (1950). The liquid-solid transition in helium near absolute zero. Nature, 165(4203), 829-830. [CrossRef]

- Clusius, K., & Riccoboni, L. (1937). The phase diagram of neon. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie, B38, 81-88.

- Hansen, M., & Verlet, L. (1969). Phase transitions of the Lennard-Jones system. Physical Review, 184(1), 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C. S., & Meyer, L. (1967). Argon—Oxygen phase diagram. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 47(2), 740-745. [CrossRef]

- Gosman, A. L., McCarty, R. D., & Hust, J. G. (1968). Thermodynamic properties of argon from the triple point to 300 K at pressures to 1000 atmospheres. National Standard Reference Data Series, National Bureau of Standards, 27.

- Beaumont, R. H., Chihara, H., & Morrison, J. A. (1961). A study of the solid phases of krypton and xenon at pressures up to 35,000 atm. Proceedings of the Physical Society, 78(6), 1462-1474. [CrossRef]

- Losee, D. L., & Simmons, R. O. (1968). Thermal-expansion measurements and thermodynamics of solid krypton. Physical Review, 172(3), 934-946. [CrossRef]

- Lahr, P. H., & Eversole, W. G. (1962). Solid-liquid-vapor equilibrium in the argon-methane system. The Journal of Chemical Engineering Data, 7(1), 42-44. [CrossRef]

- Yen, J., & Zhao, Y. (1999). Thermodynamic properties of xenon from the triple point to 800 K with pressures up to 350 MPa. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 28(6), 1671-1705. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, O., & Holzapfel, W. B. (1993). Phase diagram for mercury up to 67 GPa and 500 K. Physical Review B, 48(19), 14009-14012. [CrossRef]

- Kechin, V. V. (1995). Phase diagram of mercury to 100 GPa. Physical Review B, 51(13), 8336-8338. [CrossRef]

- Hazlehurst, J., & Murphy, K. P. (1934). Measurement of the vapor pressures of methane. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 56(8), 1655-1658. [CrossRef]

- Barmby, J. G., Lu, D. C., & Kim, G. T. (1955). Phase equilibria in binary and ternary hydrocarbon systems. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 77(12), 3299-3301. [CrossRef]

- Freiman, Y. A., & Jodl, H. J. (2004). Solid oxygen revisited. Physics Reports, 401(1-4), 1-228. [CrossRef]

- Desgreniers, S., Vohra, Y. K., & Ruoff, A. L. (1990). Optical response of very high density solid and liquid oxygen to 132 GPa. Physical Review B, 41(13), 9104-9107. [CrossRef]

- Bosio, L., Johari, G. P., & Teixeira, J. (1983). Phase diagram for ammonia-water mixtures at high pressures. Physical Review Letters, 51(15), 1324-1327. [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, D. L., & Giauque, W. F. (1953). The vapor pressure and vapor densities of ammonium hydroxide–water mixtures. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 75(11), 2811-2818. [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E. W., & Jacobsen, R. T. (2005). An international standard formulation for the thermodynamic properties of 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (HFC-134a) for temperatures from 170 to 455 K and pressures up to 70 MPa. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 34(1), 69-108. [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J., Jacobson, R. T., & Lemmon, E. W. (1995). Thermodynamic properties of R-404A (R-125/R-143a/R-134a). International Journal of Thermophysics, 16(1), 273-284. [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, D., Pan, J.-W., Mattle, K., Eibl, M., Weinfurter, H., & Zeilinger, A. (1997). Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature, 390(6660), 575-579. [CrossRef]

- Chruscinski, D., & Kossakowski, A. (2006). On the structure of entanglement witnesses. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 39(41), L603-L609. [CrossRef]

- D'Ariano, G. M., Lo Presti, P., & Paris, M. G. A. (2001). Using entanglement improves the precision of quantum measurements. Physical Review Letters, 87(27), 270404. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D. (1996). Class of quantum error-correcting codes saturating the quantum Hamming bound. Physical Review A, 54(3), 1862-1868. [CrossRef]

- ]Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P., & Horodecki, R. (1996). Separability of mixed states: Necessary and sufficient conditions. Physics Letters A, 223(1-2), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Jozsa, R. (1998). Entanglement and quantum computation. In S. Huggett (Ed.), Geometric issues in the foundations of science (pp. 137-158). Oxford University Press.

- Kakazu, K., & Matsumoto, S. (1996). General parametrization of black hole spacetimes and its application to entropy calculations. Progress of Theoretical Physics, 95(6), 1503-1515. [CrossRef]

- Kempe, J. (1999). Multiparticle entanglement and its applications to cryptography. Physical Review A, 60(2), 910-916. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2000). Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Perelman, G. (2002). The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications. arXiv preprint math/0211159. https://arxiv.org/abs/math/0211159.

- Peres, A. (1996). Separability criterion for density matrices. Physical Review Letters, 77(8), 1413-1415. (Note: Provides criteria for separability in Hilbert spaces, highlighting how prime dimensions lead to inherent indivisibility.). [CrossRef]

- Rains, E. M. (1999). Rigorous treatment of distillable entanglement. Physical Review A, 60(1), 173-178. (Note: On entanglement distillation in prime-. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).