Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Behavioral Testing

2.2.1. Grip Strength Test

2.2.2. Inverted Grid Test

2.2.3. Accelerating Rotarod Test

2.2.4. Open Field Test

2.2.5. Y-Maze

2.2.6. Elevated Plus Maze

2.2.7. Morris Water Maze

2.3. Survival Analysis

2.4. Analysis of Synaptic Markers

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

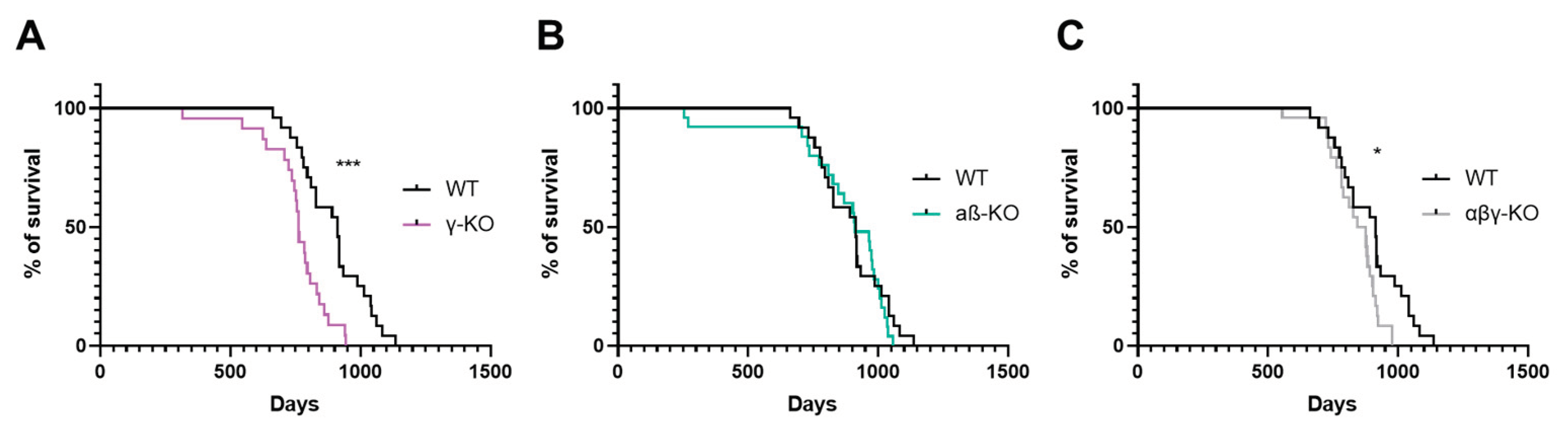

3.1. γ-Synuclein KO Mice Exhibit Reduced Lifespan

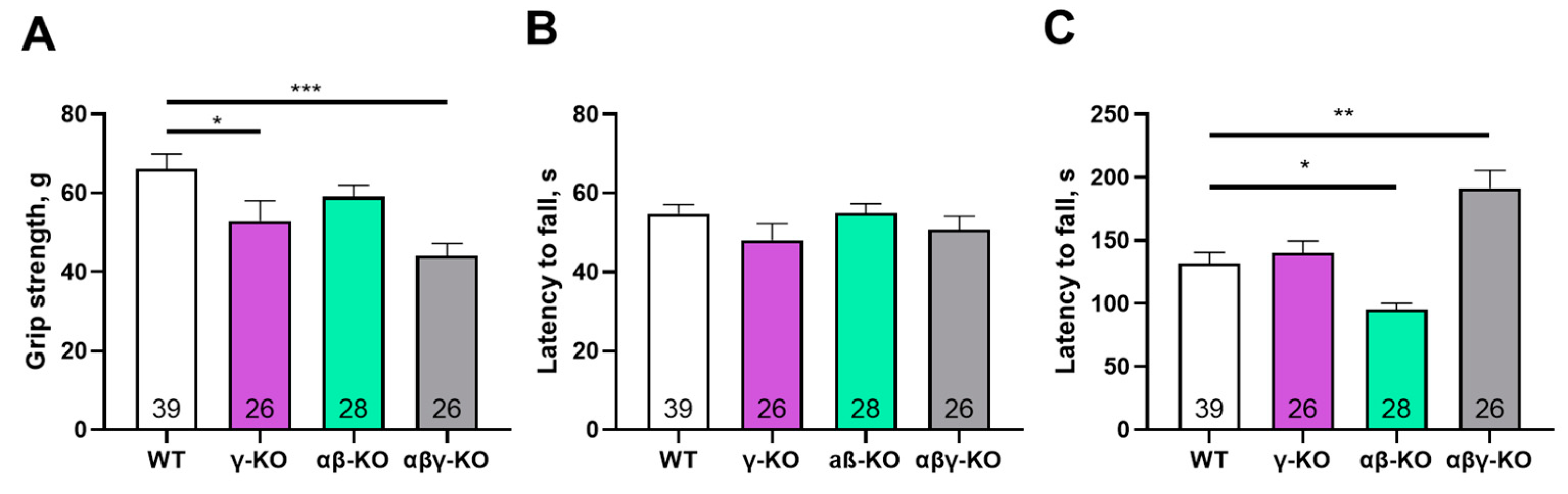

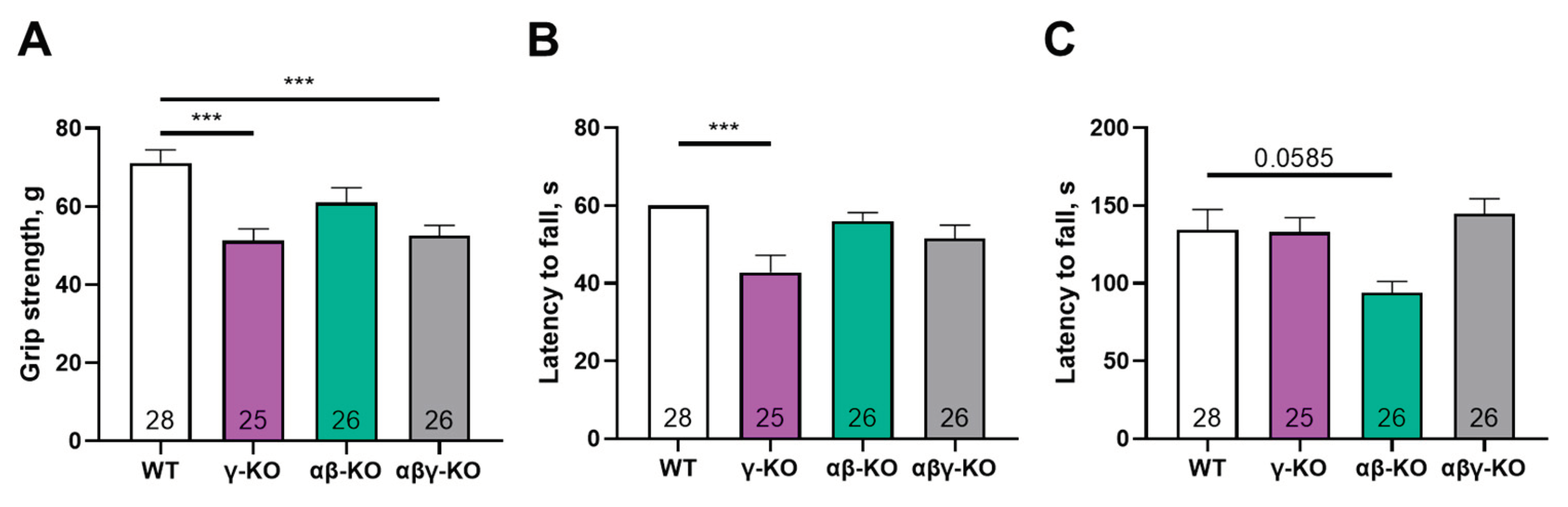

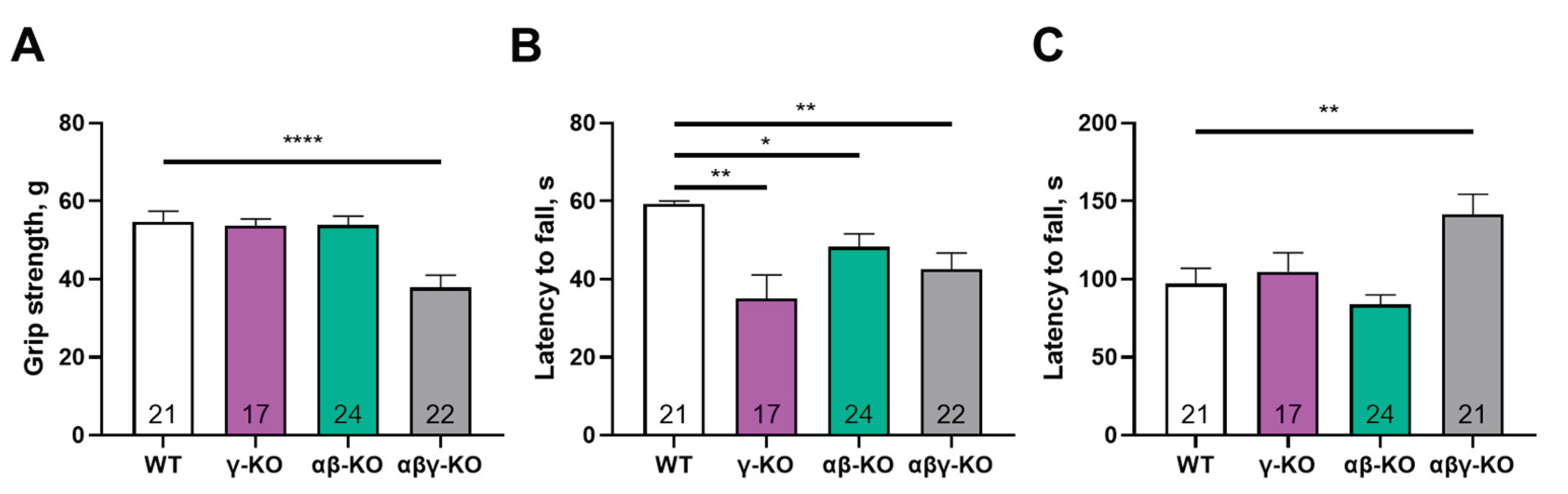

3.2. γ-Synuclein KO Mice Exhibit Decreased Muscle Strength

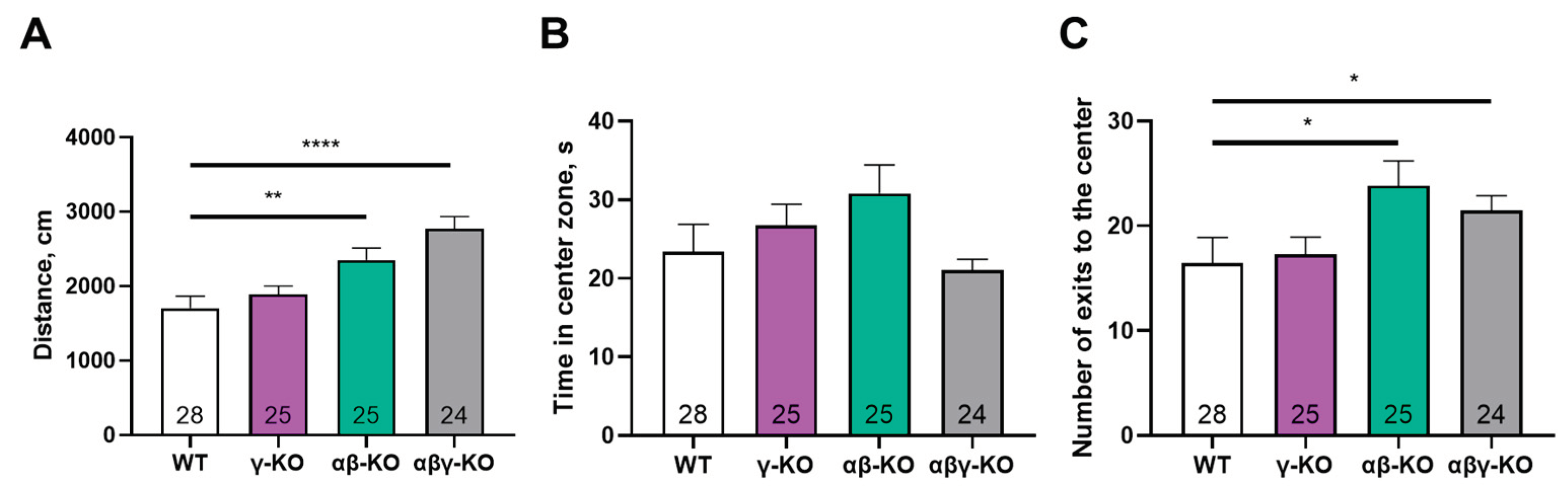

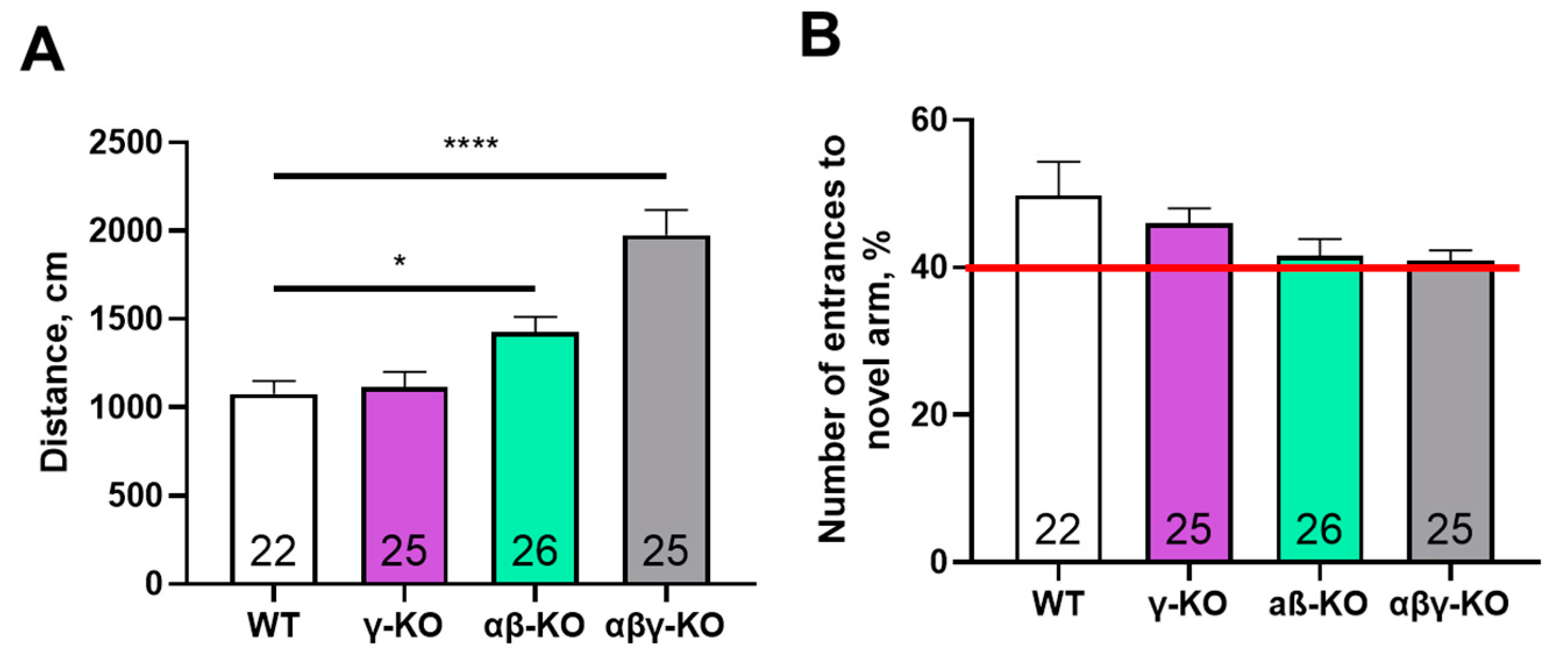

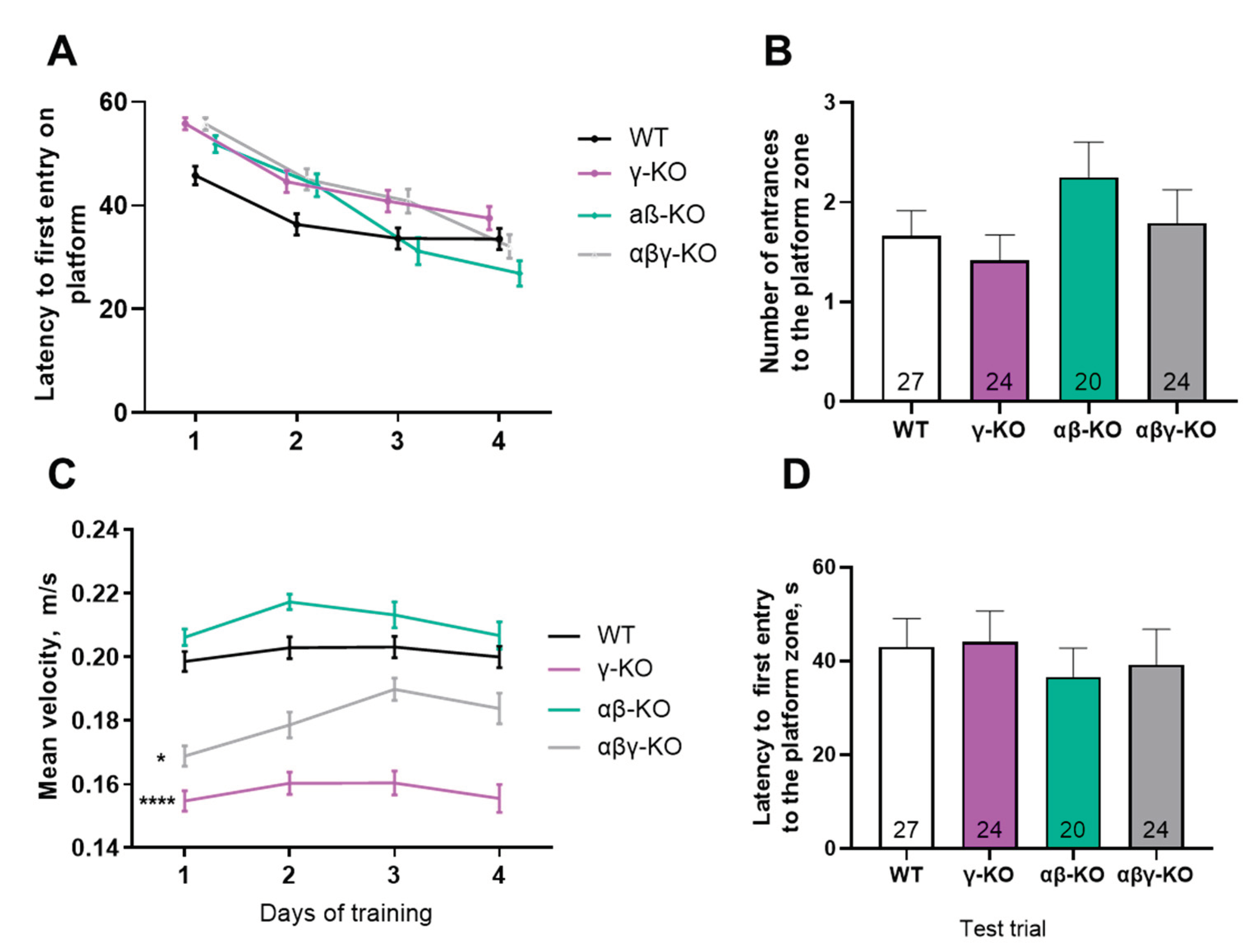

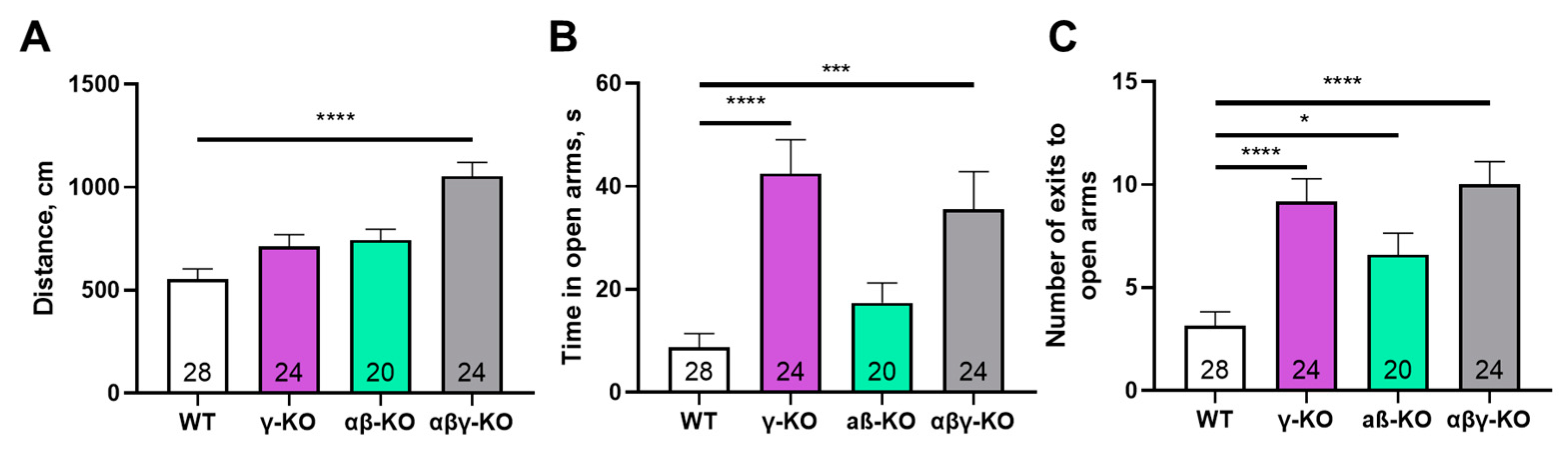

3.3. γ-Synuclein KO Mice Display Reduced Anxiety-Like behavior and no Memory Impairments

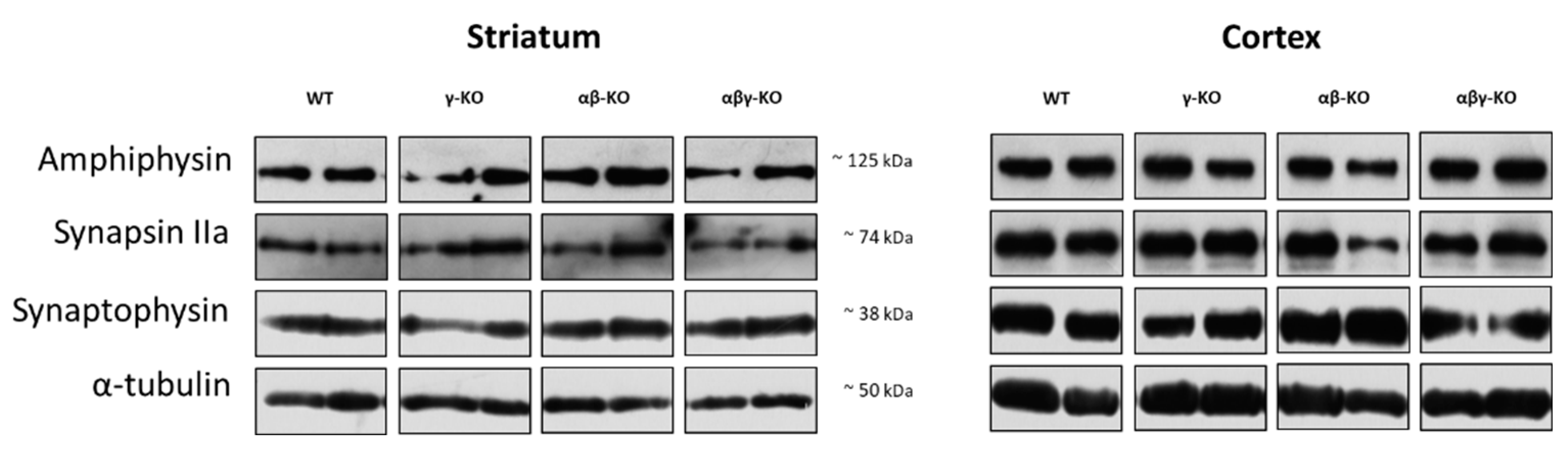

3.4. Absence of Synucleins Does not Alter Synaptic Marker Levels in the Striatum and Cortex

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ECL | Enhanced chemiluminescence |

| EPM | Elevated plus maze |

| KO | Knockout |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 |

| WT | Wild type |

| αβ-KO | double knockoutfor α- and β-synucleins (Snca−/−; Sncb−/−) |

| αβγ-KO | triple knockout for α-, β- and γ-synucleins (Snca−/−; Sncb−/−; Sncg−/−) |

| γ-KO | γ-synuclein knockout mice (Sncg−/−) |

References

- Carnazza, K.E.; Komer, L.E.; Xie, Y.X.; Pineda, A.; Briano, J.A.; Gao, V.; Na, Y.; Ramlall, T.; Buchman, V.L.; Eliezer, D.; et al. Synaptic Vesicle Binding of α-Synuclein Is Modulated by β- and γ-Synucleins. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanisms of Alpha-Synuclein Toxicity: An Update and Outlook. In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 252, pp. 91–129. ISBN 978-0-444-64260-8.

- Intracellular Dynamics of Synucleins. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Elsevier, 2015; Vol. 320, pp. 103–169. ISBN 978-0-12-802277-1.

- Baltic, S.; Perovic, M.; Mladenovic, A.; Raicevic, N.; Ruzdijic, S.; Rakic, L.; Kanazir, S. α-Synuclein Is Expressed in Different Tissues During Human Fetal Development. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004, 22, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burré, J. The Synaptic Function of α-Synuclein. J. Park. Dis. 2015, 5, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malatynska, E.; Pinhasov, A.; Crooke, J.; Horowitz, D.; Brenneman, D.E.; Ilyin, S.E. Levels of mRNA Coding for α-, β-, and γ-Synuclein in the Brains of Newborn, Juvenile, and Adult Rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burré, J.; Sharma, M.; Südhof, T.C. Cell Biology and Pathophysiology of α-Synuclein. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a024091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. α-Synuclein in Lewy Bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uéda, K.; Fukushima, H.; Masliah, E.; Xia, Y.; Iwai, A.; Yoshimoto, M.; Otero, D.A.; Kondo, J.; Ihara, Y.; Saitoh, T. Molecular Cloning of cDNA Encoding an Unrecognized Component of Amyloid in Alzheimer Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 11282–11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkina, N.; Peters, O.; Millership, S.; Salem, H.; Van Der Putten, H.; Buchman, V.L. γ-Synucleinopathy: Neurodegeneration Associated with Overexpression of the Mouse Protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1779–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, O.M.; Millership, S.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Soto, I.; Keeling, L.; Hann, A.; Marsh-Armstrong, N.; Buchman, V.L.; Ninkina, N. Selective Pattern of Motor System Damage in Gamma-Synuclein Transgenic Mice Mirrors the Respective Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, O.M.; Shelkovnikova, T.; Highley, J.R.; Cooper-Knock, J.; Hortobágyi, T.; Troakes, C.; Ninkina, N.; Buchman, V.L. Gamma-synuclein Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2015, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surgucheva, I.; Newell, K.L.; Burns, J.; Surguchov, A. New α- and γ-Synuclein Immunopathological Lesions in Human Brain. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, R.; Luo, C.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, J.-D.; Liu, J. Loss of Epigenetic Control of Synuclein-γ Gene as a Molecular Indicator of Metastasis in a Wide Range of Human Cancers. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 7635–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkina, N. Organization, Expression and Polymorphism of the Human Persyn Gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998, 7, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surguchov, A. γ-Synuclein as a Cancer Biomarker: Viewpoint and New Approaches. Oncomedicine 2016, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, L.C.; Malizia, F.; Cesatti Laluce, N.; Avila, A.; Mamberto, M.; Anselmino, L.E.; Menacho-Márquez, M. Synuclein Proteins in Cancer Development and Progression. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biere, A.L.; Wood, S.J.; Wypych, J.; Steavenson, S.; Jiang, Y.; Anafi, D.; Jacobsen, F.W.; Jarosinski, M.A.; Wu, G.-M.; Louis, J.-C.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease-Associated α-Synuclein Is More Fibrillogenic than β- and γ-Synuclein and Cannot Cross-Seed Its Homologs. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 34574–34579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi Di Patti, M.C.; Meoni, M.; Toni, M. Comparative Analysis of Aggregation of β- and γ-Synucleins in Vertebrates. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giasson, B.I.; Murray, I.V.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y. A Hydrophobic Stretch of 12 Amino Acid Residues in the Middle of α-Synuclein Is Essential for Filament Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 2380–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.P.; Buell, A.K.; Michaels, T.C.T.; Meisl, G.; Carozza, J.; Flagmeier, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Knowles, T.P.J.; Dobson, C.M.; Galvagnion, C. β-Synuclein Suppresses Both the Initiation and Amplification Steps of α-Synuclein Aggregation via Competitive Binding to Surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Shi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, L.; Li, N.; Liu, X.; et al. β-Synuclein Regulates the Phase Transitions and Amyloid Conversion of α-Synuclein. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Lansbury, P.T. β-Synuclein Inhibits Formation of α-Synuclein Protofibrils: A Possible Therapeutic Strategy against Parkinson’s Disease. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 3696–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Fornai, F.; Kwon, H.-B.; Yazdani, U.; Atasoy, D.; Liu, X.; Hammer, R.E.; Battaglia, G.; German, D.C.; Castillo, P.E.; et al. Double-Knockout Mice for α- and β-Synucleins: Effect on Synaptic Functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 14966–14971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten-Harrison, B.; Polydoro, M.; Morimoto-Tomita, M.; Diao, L.; Williams, A.M.; Nie, E.H.; Makani, S.; Tian, N.; Castillo, P.E.; Buchman, V.L.; et al. Aβγ-Synuclein Triple Knockout Mice Reveal Age-Dependent Neuronal Dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 19573–19578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokhan, V.S.; Afanasyeva, M.A.; Van’kin, G.I. α-Synuclein Knockout Mice Have Cognitive Impairments. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 231, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Peters, O.; Millership, S.; Ninkina, N.; Doig, N.; Connor-Robson, N.; Threlfell, S.; Kooner, G.; Deacon, R.M.; Bannerman, D.M.; et al. Functional Alterations to the Nigrostriatal System in Mice Lacking All Three Members of the Synuclein Family. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 7264–7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Robson, N.; Peters, O.M.; Millership, S.; Ninkina, N.; Buchman, V.L. Combinational Losses of Synucleins Reveal Their Differential Requirements for Compensating Age-Dependent Alterations in Motor Behavior and Dopamine Metabolism. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 46, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burré, J.; Sharma, M.; Tsetsenis, T.; Buchman, V.; Etherton, M.R.; Südhof, T.C. α-Synuclein Promotes SNARE-Complex Assembly in Vivo and in Vitro. Science 2010, 329, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Oliver, Y.; Buchman, V.L.; Dalley, J.W.; Robbins, T.W.; Schumann, G.; Ripley, T.L.; King, S.L.; Stephens, D.N. Deletion of Alpha-synuclein Decreases Impulsivity in Mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2012, 11, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Hart, D.W.; Boyle, G.E.; Brown, T.G.; LaCroix, M.; Baraibar, A.M.; Pelzel, R.; Kim, M.; Sherman, M.A.; Boes, S.; et al. SNCA Genetic Lowering Reveals Differential Cognitive Function of Alpha-Synuclein Dependent on Sex. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Oliver, Y.; Buchman, V.L.; Stephens, D.N. Lack of Involvement of Alpha-Synuclein in Unconditioned Anxiety in Mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 209, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, V.S.; Van’kin, G.I.; Bachurin, S.O.; Shamakina, I.Y. Differential Involvement of the Gamma-Synuclein in Cognitive Abilities on the Model of Knockout Mice. BMC Neurosci. 2013, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeckl, P.; Metzger, F.; Nagl, M.; Von Arnim, C.A.F.; Halbgebauer, S.; Steinacker, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Otto, M. Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-Synuclein Quantification in Cerebrospinal Fluid by Multiple Reaction Monitoring Reveals Increased Concentrations in Alzheimer′s and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease but No Alteration in Synucleinopathies. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2016, 15, 3126–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B.; Milne, J.; Andras, A.; Abdel-All, Z.; Cerejeira, J.; Greally, E.; Robson, J.; Jaros, E.; Perry, R.; McKeith, I.G.; et al. Alpha- and Gamma-Synuclein Proteins Are Present in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Are Increased in Aged Subjects with Neurodegenerative and Vascular Changes. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 26, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkina, N.; Connor-Robson, N.; Ustyugov, A.A.; Tarasova, T.V.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Buchman, V.L. A Novel Resource for Studying Function and Dysfunction of α-Synuclein: Mouse Lines for Modulation of Endogenous Snca Gene Expression. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkina, N.; Papachroni, K.; Robertson, D.C.; Schmidt, O.; Delaney, L.; O’Neill, F.; Court, F.; Rosenthal, A.; Fleetwood-Walker, S.M.; Davies, A.M.; et al. Neurons Expressing the Highest Levels of γ-Synuclein Are Unaffected by Targeted Inactivation of the Gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8233–8245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arudkumar, J.; Chinn Joshua Chey, Y.; Piltz, S.; Quinton Thomas, P.; Adikusuma, F. Forelimb Grip Strength Testing V1 2024.

- Chaprov, K.D.; Teterina, E.V.; Roman, A.Yu.; Ivanova, T.A.; Goloborshcheva, V.V.; Kucheryanu, V.G.; Morozov, S.G.; Lysikova, E.A.; Lytkina, O.A.; Koroleva, I.V.; et al. Comparative Analysis of MPTP Neurotoxicity in Mice with a Constitutive Knockout of the α-Synuclein Gene. Mol. Biol. 2021, 55, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakkamsetti, V.; Scudder, W.; Kathote, G.; Ma, Q.; Angulo, G.; Dobariya, A.; Rosenberg, R.N.; Beutler, B.; Pascual, J.M. Quantification of Early Learning and Movement Sub-Structure Predictive of Motor Performance. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellért, L.; Varga, D. Locomotion Activity Measurement in an Open Field for Mice. BIO-Protoc 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestakova, N.; Puzserova, A.; Kluknavsky, M.; Bernatova, I. Determination of Motor Activity and Anxiety-Related Behaviour in Rodents: Methodological Aspects and Role of Nitric Oxide. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2013, 6, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatem, K.S.; Quinn, J.L.; Phadke, A.; Yu, Q.; Gordish-Dressman, H.; Nagaraju, K. Behavioral and Locomotor Measurements Using an Open Field Activity Monitoring System for Skeletal Muscle Diseases. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 51785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.-H.; Jang, E.-H.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, H.-R.; Bakes, J.; Kong, Y.-Y.; Kaang, B.-K. Basal Anxiety during an Open Field Test Is Correlated with Individual Differences in Contextually Conditioned Fear in Mice. Anim. Cells Syst. 2013, 17, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellu, F.; Contarino, A.; Simon, H.; Koob, G.F.; Gold, L.H. Genetic Differences in Response to Novelty and Spatial Memory Using a Two-Trial Recognition Task in Mice. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2000, 73, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walf, A.A.; Frye, C.A. The Use of the Elevated plus Maze as an Assay of Anxiety-Related Behavior in Rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, M.; Xu, J.; Sakic, B. The Water Maze Paradigm in Experimental Studies of Chronic Cognitive Disorders: Theory, Protocols, Analysis, and Inference. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsa, L.; Goda, Y. Synaptophysin Regulates Activity-Dependent Synapse Formation in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmann, B.; Franke, W.W. Identification and Localization of Synaptophysin, an Integral Membrane Glycoprotein of Mr 38,000 Characteristic of Presynaptic Vesicles. Cell 1985, 41, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujise, K.; Mishra, J.; Rosenfeld, M.S.; Rafiq, N.M. Synaptic Vesicle Characterization of iPSC-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons Provides Insight into Distinct Secretory Vesicle Pools. Npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitler, D.; Augustine, G.J. Synapsins and Regulation of the Reserve Pool. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 709–717. ISBN 978-0-08-045046-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stavsky, A.; Parra-Rivas, L.A.; Tal, S.; Riba, J.; Madhivanan, K.; Roy, S.; Gitler, D. Synapsin E-Domain Is Essential for α-Synuclein Function. eLife 2024, 12, RP89687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Chin, L.-S.; Li, L.; Lanier, L.M.; Kosik, K.S.; Greengard, P. Distinct Roles of Synapsin I and Synapsin II during Neuronal Development. Mol. Med. 1998, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerfeind, R.; Takei, K.; De Camilli, P. Amphiphysin I Is Associated with Coated Endocytic Intermediates and Undergoes Stimulation-Dependent Dephosphorylation in Nerve Terminals. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30984–30992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.; McPherson, P.S.; Mundigl, O.; De Camilli, P. A Role of Amphiphysin in Synaptic Vesicle Endocytosis Suggested by Its Binding to Dynamin in Nerve Terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontaxi, C.; Kim, N.; Cousin, M.A. The Phospho-regulated Amphiphysin/Endophilin Interaction Is Required for Synaptic Vesicle Endocytosis. J. Neurochem. 2023, 166, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, V.; Briano, J.A.; Komer, L.E.; Burré, J. Functional and Pathological Effects of α-Synuclein on Synaptic SNARE Complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeliovich, A.; Schmitz, Y.; Fariñas, I.; Choi-Lundberg, D.; Ho, W.-H.; Castillo, P.E.; Shinsky, N.; Verdugo, J.M.G.; Armanini, M.; Ryan, A.; et al. Mice Lacking α-Synuclein Display Functional Deficits in the Nigrostriatal Dopamine System. Neuron 2000, 25, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somayaji, M.; Cataldi, S.; Choi, S.J.; Edwards, R.H.; Mosharov, E.V.; Sulzer, D. A Dual Role for α-Synuclein in Facilitation and Depression of Dopamine Release from Substantia Nigra Neurons in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 32701–32710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkina, N.; Millership, S.J.; Peters, O.M.; Connor-Robson, N.; Chaprov, K.; Kopylov, A.T.; Montoya, A.; Kramer, H.; Withers, D.J.; Buchman, V.L. β-Synuclein Potentiates Synaptic Vesicle Dopamine Uptake and Rescues Dopaminergic Neurons from MPTP-Induced Death in the Absence of Other Synucleins. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Xiong, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, S.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Z. Chronic Stress Induces Depression-like Behaviors and Parkinsonism via Upregulating α-Synuclein. Npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, V.S.; Bolkunov, A.V.; Ustiugov, A.A.; Van’kin, G.I.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Redkozubova, O.M.; Strekalova, T.V.; Buchman, V.L.; Ninkina, N.N.; Bachurin, S.O. Targeted Inactivation of the Gene Encoding Gamma-Synuclein Affects Anxiety Levels and Investigative Activity in Mice. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2012, 42, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wandi, A.; Ninkina, N.; Millership, S.; Williamson, S.J.M.; Jones, P.A.; Buchman, V.L. Absence of α-Synuclein Affects Dopamine Metabolism and Synaptic Markers in the Striatum of Aging Mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yang, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.-S.; Hyun, S.-H.; Moon, C. Upregulation of γ-Synuclein in the Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampus Following Dopamine Depletion: A Study Using the Striatal 6-Hydroxydopamine Hemiparkinsonian Rat Model. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 839, 137936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, F.; Dreyer, J. The Role of Gamma-synuclein in Cocaine-induced Behaviour in Rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 27, 2938–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).