Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Defining Objectives

- examine and categorize known barriers to effective adoption,

- carry out thematic review of emerging AI innovation systems with potential for enterprise adoption vis-à-vis alignment, enhancement and/or strategic replacement of features of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), a mainstream organizational technology integration pattern,

- propose an approach to effective adoption

- create a tool that exemplifies our adoption proposal which could facilitate well-informed adoption decisions and further impact research.

1.2. Methodology

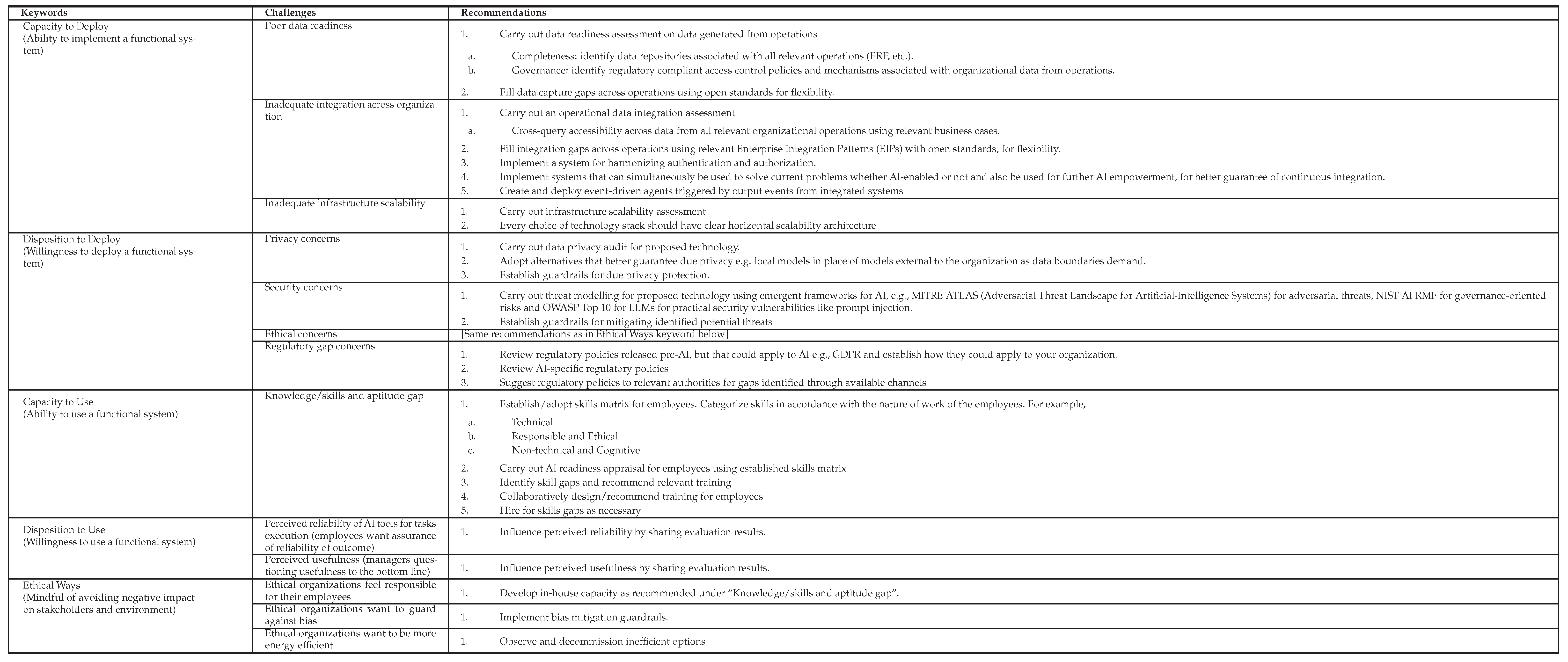

2. Observed Barriers to Effective Adoption

2.1. Weak or Non-Existent Strategy

2.2. Poor Data Readiness and Privacy Concerns

2.3. Inadequate Human Knowledge Skills and Attitudes/Abilities (KSA)

2.4. Scalable and Secure Infrastructure Challenges

2.5. Ethical Governance Concerns

2.6. Regulatory Framework Lag

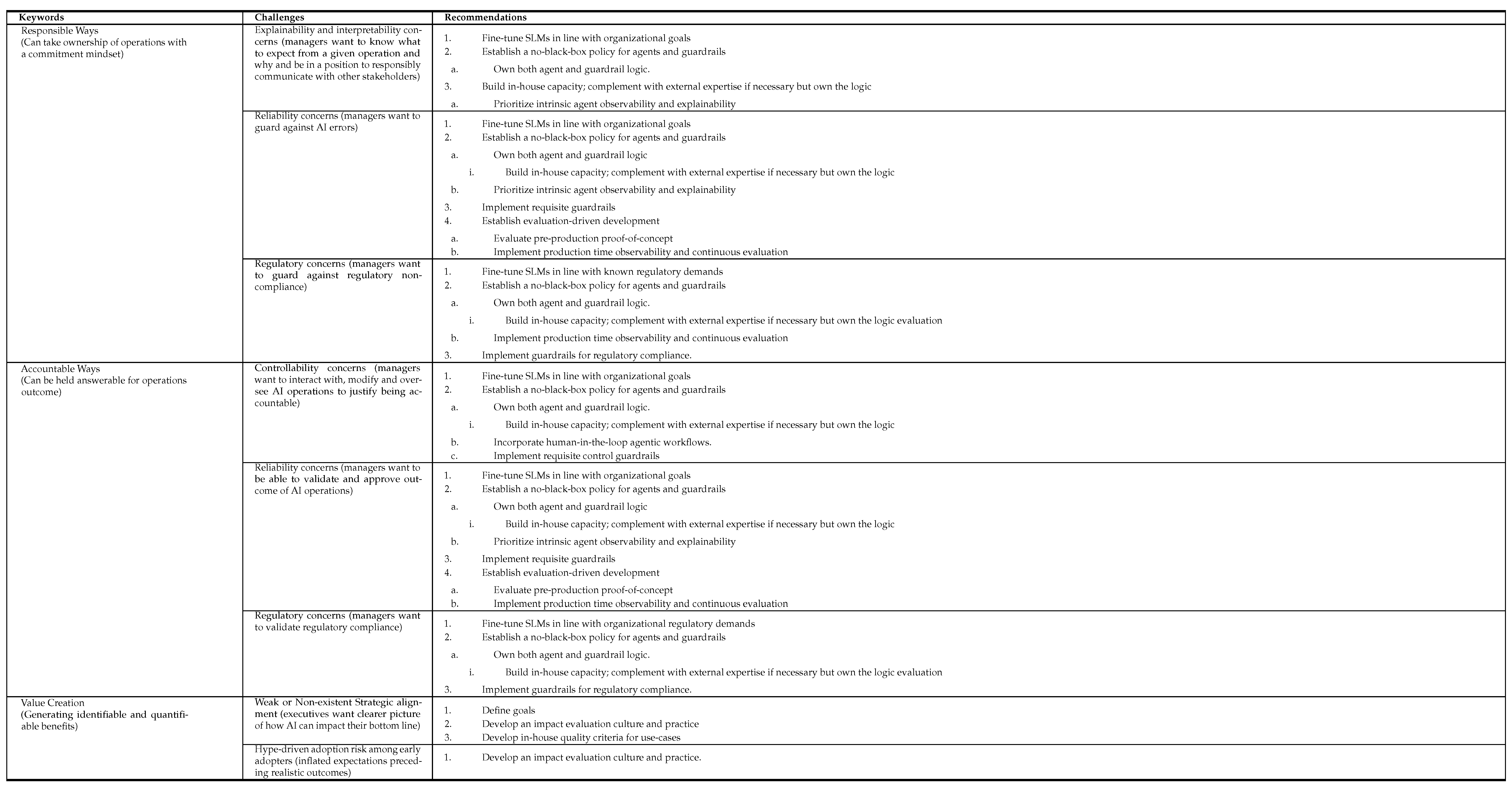

2.7. Responsibility and Accountability Concerns

2.8. Reliability Concerns

3. Milestone AI Innovations with Organizational Adoption Potential Vis-à-Vis ERP Integration

3.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

3.1.1. Embedding Models

3.1.2. Retrieval Models

3.1.3. Vector Databases

3.2. GraphRAG

3.3. Small Language Models Creation

3.4. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT)

3.5. Document Understanding

3.6. Agentic AI

3.7. Authentication, Authorization and Guardrails

3.8. AI Operations Transparency: Observability, Explainability and Evaluability

3.8.1. Observability

3.8.2. Explainability

3.8.3. Evaluating AI Operations

3.8.4. Combined Tooling

4. Synthesis of an Adoption Approach

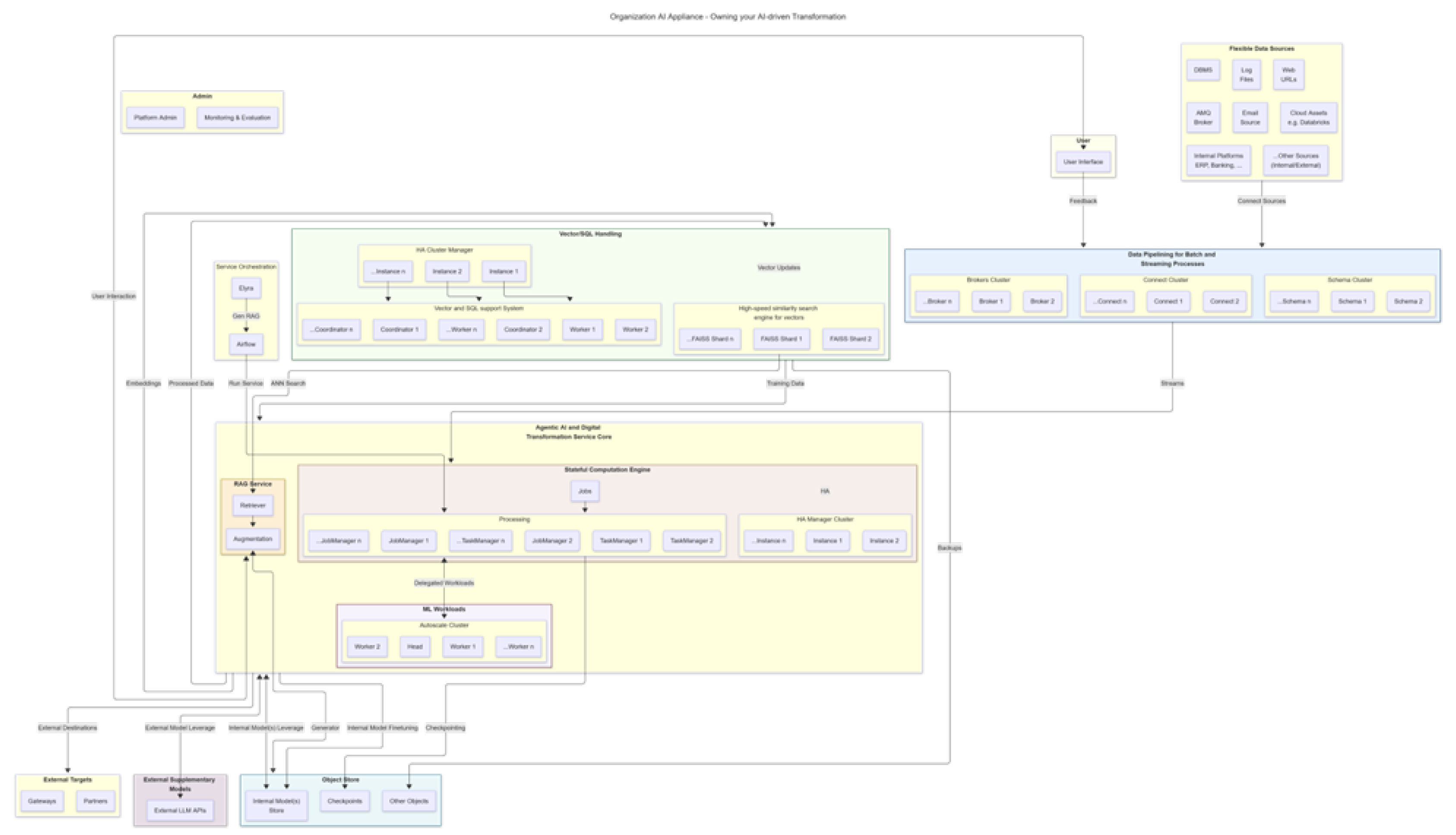

4.1. Organizational AI Appliance Deployer (OAAD)

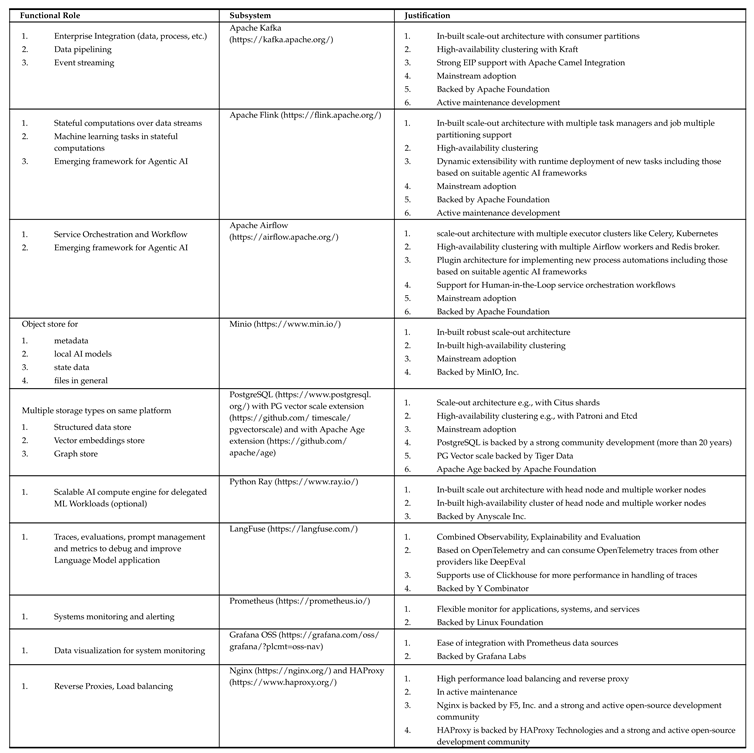

4.1.1. Choosing Subsystems

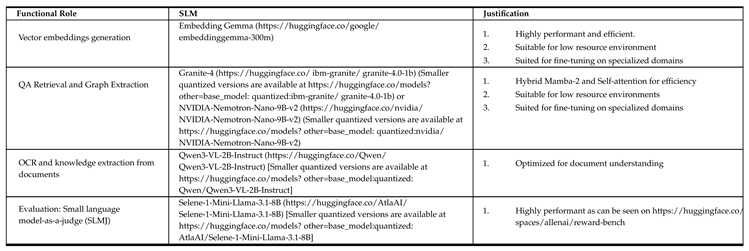

4.2. Choosing Foundational Models

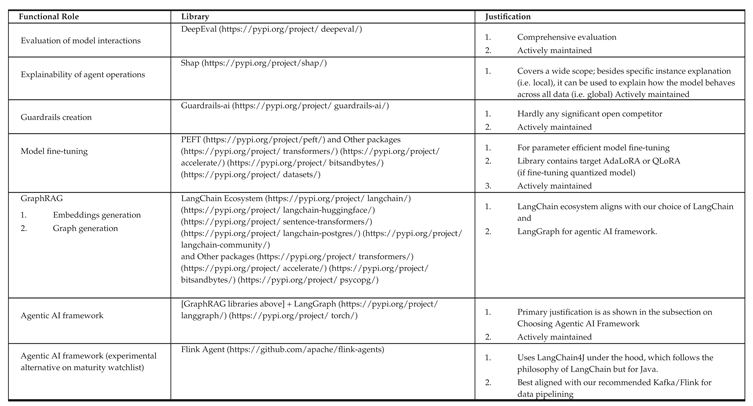

4.3. Choosing Key Python Libraries

4.4. Choosing Agentic AI Framework

- Use of local SLMs (external LLMs as supplementary).

- Locally run LangFuse for observability, eval, metrics, etc., as well as use of python libraries like shap and judge models like https://huggingface.co/AtlaAI/Selene-1-Mini-Llama-3.1-8B

- Kafka and Flink-based data pipelines for real-time data

- Agents as airflow plugins or agents as flink UDF as may be necessary for no real-time or real-time data pipelining

- GPU usage support

- Guardrails using https://github.com/guardrails-ai/guardrails

- RAG/GraphRAG using pgvectorscale for vector embeddings and Apache age for graph databases and integrated tools for knowledge graph creation

- Model fine-tuning - batch and real-time - with AdaLoRA or QLoRA

- Locally run Google’s embedding_gemma from hugging face for embeddings generation

- Locally run Granite-4 (or Nvidia-nemotron-v2) for Retrieval QA

- Human-in-the-loop workflow support

- Enterprise SSO support

- “No black-box” policy

- Openness

- Battle-tested

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

- Take an integrated platform approach to AI technology adoption akin to experience with ERP. The integrated system should include clearly defined points of data integration with existing technology solutions as exemplified by OAAD, especially with ERP that typically has wide stakeholder reach in organizations.

- Establish an approach to authentication and authorization that harmonizes with existing infrastructure.

- Have preference for integrated platform that seamlessly enables you to solve dynamic business problems, whether your digital solutions require AI or not.

- Your integrated infrastructure should include a flexible way to store, fine-tune and use local language models with a privacy-first philosophy, complemented by external LLMs.

- Build IT capacity (in-house and/or consultants) to identify strengths and limitations of available models for in-house adoption and monitor progressive evolution of model algorithms as limitations are overcome. In other words, know when and why you should upgrade.

- Regarding Agentic AI, operate with a no-black-box philosophy.

- Strategically identify and implement standard guardrails for security, ethical and regulatory compliance.

- Adopt agentic frameworks and tools that support fine-grained observability, explainability and evaluability.

- Build IT capacity (in-house and/or consultants) that enables you dynamically create agents in response to dynamic business needs and deploy on your integrated platform.

- In creating agents, use agents workflow type as default for more control, rather than ReAct type agents. Use the latter when you see value in giving the agents workflow decision autonomy.

- Strategically identify where you can use AI agents to enhance, replace or complement your existing technology solutions.

- Develop an impact research culture for continuous improvement.

5.1. Limitations and Future Work

References

- A. A. Abdullah, A. Zubiaga, S. Mirjalili, A. H. Gandomi, F. Daneshfar, M. Amini, A. S. Mohammed, and H. Veisi. Evolution of Meta’s Llama models and parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large language models: a survey. Technical report, October 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.12178v1. Preprint.

- D. B. Acharya, K. Kuppan, and B. Divya. Agentic AI: Autonomous intelligence for complex goals—a comprehensive survey. IEEE Access, 13:18912–18936, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Monika Agrawal. Implementing enterprise observability for success: strategically plan and implement observability using real-life examples. Packt Publishing Ltd., 1 edition, 2023.

- A. Alexandru, A. Calvi, H. Broomfield, J. Golden, K. Dai, M. Leys, M. Burger, M. Bartolo, R. Engeler, S. Pisupati, T. Drane, and Y. S. Park. Atla Selene Mini: A general-purpose evaluation model. Technical report, January 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.17195v1. Preprint.

- E. Anderson, G. Parker, and B. Tan. The hidden costs of coding with generative AI. MIT Sloan Management Review, 67(1), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Introducing the model context protocol, November 25 2024. URL https://www.anthropic.com/news/model-context-protocol.

- Anthropic. Effective context engineering for AI agents, September 29 2025. URL https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/effective-context-engineering-for-ai-agents.

- Adam Badman. How observability is adjusting to generative AI. https://www.ibm.com/think/insights/observability-gen-ai. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- Chester I. Barnard. The functions of the executive. Harvard University Press, 1968.

- P. Belcak, G. Heinrich, S. Diao, Y. Fu, X. Dong, S. Muralidharan, Y. C. Lin, and P. Molchanov. Small language models are the future of agentic AI. Technical report, June 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.02153. Preprint.

- BetterUp Labs. Workslop: The hidden cost of AI-generated busywork, September 2025. URL https://www.betterup.com/workslop.

- Francesco Bianchini. Retrieval-augmented generation. In F. De Luzi, F. Monti, and M. Mecella, editors, Engineering Information Systems with Large Language Models, pages 139–172. Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Carlson, J. Bauer, and Christopher D. Manning. A new pair of GloVEs. Technical report, July 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.18103. Preprint.

- Paul Carter. Observability for large language models: understanding and improving your use of LLMs. O’Reilly Media, Inc., first edition, 2023.

- A. Challapally, C. Pease, R. Raskar, and P. Chari. The GenAI divide STATE OF AI IN BUSINESS 2025, July 2025. URL https://example.com/genai-divide-2025.

- J. Chen, Y. Lu, X. Wang, H. Zeng, J. Huang, J. Gesi, Y. Xu, B. Yao, and D. Wang. Multi-agent-as-judge: Aligning LLM-agent-based automated evaluation with multi-dimensional human evaluation. Technical report, July 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.21028. Preprint.

- R. Chinni. Authentication and authorization for AI agents and risks involved. TechRxiv, July 19 2025. URL https://www.techrxiv.org/users/939863/articles/1310017-authentication-and-authorization-for-ai-agents-and-risks-involved.

- Cristina Criddle and Madhumita Murgia. AI pioneers turn to small language models: Technology less complex products target clients with cost and data privacy concerns. The Financial Times (London Ed.), 2024.

- Tri Dao and Albert Gu. Transformers are SSMs: Generalized models and efficient algorithms through structured state space duality. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, volume 235, pages 10041–10071, 2024.

- Victoria Davies. Rushing out AI likely to backfire, report, September 25 2025. URL https://www.computing.co.uk/news/2025/ai/rushing-out-ai-likely-to-backfire-report.

- S. Demigha. Decision support systems (DSS) and management information systems (MIS) in today’s organizations. In European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, pages 92–100, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Dev, N. B. Akhuseyinoglu, G. Kayas, B. Rashidi, and V. Garg. Building guardrails in AI systems with threat modeling. Digital Government (New York, N.Y. Online), 6(1):1–18, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.04805.

- M.-E. Dinculeana. Transforming banking customer service: A detailed exploration of AI adoption with lessons from european countries. Finance: Challenges of the Future, 1(26):138–159, 2024.

- Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In ICLR 2021 - 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Matthijs Douze, Alexandr Guzhva, Chengda Deng, Jeff Johnson, Gergely Szilvasy, Pierre-Emmanuel Mazaré, Maria Lomeli, Lucas Hosseini, and Hervé Jégou. The Faiss library. Technical report, January 2024.

- Sylvain Duranton. Beyond accuracy: The changing landscape of AI evaluation. Forbes, March 14 2024. URL https://www.forbes.com/sites/sylvainduranton/2024/03/14/beyond-accuracy-the-changing-landscape-of-ai-evaluation/.

- Pouyan Esmaeilzadeh. Challenges and strategies for wide-scale artificial intelligence (AI) deployment in healthcare practices: A perspective for healthcare organizations. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 151:102861, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sean Falconer. The future of AI agents is event-driven. Medium, March 12 2025a. URL https://seanfalconer.medium.com/the-future-of-ai-agents-is-event-driven-9e25124060d6.

- Sean Falconer. A guide to event-driven design for agents and multi-agent systems, 2025b.

- Stefan Feuerriegel, Jochen Hartmann, Christian Janiesch, and Patrick Zschech. Generative AI. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 66(1):111–126, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tom Fitz. Vector databases - what’s our vector, victor? Zenoss Blog, December 21 2023. URL https://www.zenoss.com/blog/ai-explainer-whats-our-vector-victor.

- Jianping Gou, Baosheng Yu, Stephen J. Maybank, and Dacheng Tao. Knowledge distillation: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision, 129(6):1789–1819, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Maria J. Grant and Andrew Booth. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2):91–108, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ruiqi Guo, Philip Sun, Erik Lindgren, Quan Geng, David Simcha, Felix Chern, and Sanjiv Kumar. Accelerating large-scale inference with anisotropic vector quantization. In 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2020), pages 3845–3854, 2019. Two entries with same PDF – using same eprint for both.

- K. Gurjar, A. Jangra, H. Baber, M. Islam, and S. A. Sheikh. An analytical review on the impact of artificial intelligence on the business industry: Applications, trends, and challenges. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 52(2):84–102, 2024. doi: 10.1109/EMR.2024.3355973. URL. [CrossRef]

- H. Han, H. Shomer, Y. Wang, Y. Lei, K. Guo, Z. Hua, B. Long, H. Liu, and J. Tang. RAG vs. GraphRAG: A systematic evaluation and key insights. Technical report, February 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2502.11371. Preprint.

- Y. He, E. Wang, Y. Rong, Z. Cheng, and H. Chen. Security of AI agents. Technical report, June 2024. v2.

- Geoffrey Hinton, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. Technical report, 2015.

- Gregor Hohpe. Enterprise integration patterns: designing, building, and deploying messaging solutions. Addison-Wesley, 1 edition, 2003.

- K. Hong, A. Troynikov, and J. Huber. Context rot: How increasing input tokens impacts LLM performance. Chroma Research, 2025. URL https://research.trychroma.com/context-rot.

- Tim Hornyak. Agentic AI is here—but are we ready? Research Technology Management, 68(5):57–58, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Hou, Y. Zhao, S. Wang, and H. Wang. Model context protocol (MCP): Landscape, security threats, and future research directions. Technical Report 1, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.23278.

- D. Hradecky, J. Kennell, W. Cai, and R. Davidson. Organizational readiness to adopt artificial intelligence in the exhibition sector in western europe. International Journal of Information Management, 65:102497, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kevin Huang. Agentic AI: Theories and Practices. Springer, 1 edition, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nathalie Japkowicz and Zois Boukouvalas. MACHINE LEARNING EVALUATION: Towards Reliable and Responsible AI. Cambridge University Press, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jeff Johnson, Matthijs Douze, and Hervé Jégou. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 7(3):535–547, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lukas Kastner, Miriam Langer, Viktoria Lazar, Annika Schomacker, Timo Speith, and Stefan Sterz. On the relation of trust and explainability: Why to engineer for trustworthiness. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Requirements Engineering, pages 169–175, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Khandabattu. The 2025 hype cycle for artificial intelligence goes beyond GenAI. Gartner, July 8 2025. URL https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/hype-cycle-for-artificial-intelligence.

- A. Khanna and A. Bhusri. Navigating AI adoption - an “AI verse” framework for enterprises. In 2025 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), pages 1488–1491, 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Koc, J. Verre, D. Blank, and A. Morgan. Mind the metrics: Patterns for telemetry-aware in-ide AI application development using the model context protocol (MCP). Technical report, June 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.11019v1. Preprint.

- D. Kundaliya. UK workers say AI agents are “unreliable”, September 25 2025. URL https://www.computing.co.uk/news/2025/ai/uk-workers-say-ai-agents-are-unreliable.

- J. Lang, Z. Guo, and S. Huang. A comprehensive study on quantization techniques for large language models. Technical report, November 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.02530v1. Preprint.

- James Larson and Sarah Truitt. GraphRAG: Unlocking LLM discovery on narrative private data. Microsoft Research Blog, February 13 2024. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/graphrag-unlocking-llm-discovery-on-narrative-private-data/.

- L. Leoni, G. Gueli, M. Ardolino, M. Panizzon, and S. Gupta. AI-empowered KM processes for decision-making: empirical evidence from worldwide organisations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(11):320–347, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Patrick Lewis, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen-tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, Sebastian Riedel, and Douwe Kiela. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In ArXiv.org, 2021.

- Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, Veselin Stoyanov, and Peter G. Allen. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. Technical report, 2019.

- Mitra Madanchian and Hamed Taherdoost. Barriers and enablers of AI adoption in human resource management: A critical analysis of organizational and technological factors. Information (Basel), 16(1):51, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Manditereza. A2A for enterprise-scale AI agent communication: Architectural needs and limitations. HiveMQ Blog, August 25 2025. URL https://www.hivemq.com/blog/a2a-enterprise-scale-agentic-ai-collaboration-part-1/.

- S. Marocco, B. Barbieri, and A. Talamo. Exploring facilitators and barriers to managers’ adoption of AI-based systems in decision making: A systematic review. AI, 5(4):2538–2567, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bernard Marr. A short history of ChatGPT: How we got to where we are today. Forbes, May 19 2023. URL https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2023/05/19/a-short-history-of-chatgpt-how-we-got-to-where-we-are-today/.

- Ronald E. McGaughey and Angappa Gunasekaran. Enterprise resource planning (ERP): Past, present and future. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems, 3(3):23–35, 2007. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. What are AI guardrails?, November 14 2024. URL https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-are-ai-guardrails.

- McKinsey. The state of AI: Global survey, March 12 2025. URL https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai.

- J. P. Mendes, M. Marques, and C. Guedes Soares. Risk avoidance in strategic technology adoption. Journal of Modelling in Management, 19(5):1485–1509, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Patrick Mikalef, Kieran Conboy, Jon Erik Lundström, and Aleš Popovič. Thinking responsibly about responsible AI and “the dark side” of AI. European Journal of Information Systems, 31(3):257–268, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tomas Mikolov, Kai Chen, Greg Corrado, and Jeffrey Dean. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. In 1st International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2013 - Workshop Track Proceedings, 2013.

- Prateek Mishra. Practical explainable AI using Python: artificial intelligence model explanations using Python-based libraries, extensions, and frameworks. Apress, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Nazemi, M. J. Tarokh, and G. R. Djavanshir. ERP: a literature survey. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 61(9–12):999–1018, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Oliver Neumann, Katharina Guirguis, and Reto Steiner. Exploring artificial intelligence adoption in public organizations: a comparative case study. Public Management Review, 26(1):114–141, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Andrew Ng. Autonomous coding agents, instability at stability AI, Mamba mania, and more. The Batch (DeepLearning.AI), April 10 2024a. URL https://www.deeplearning.ai/the-batch/issue-244/.

- Andrew Ng. Four AI agent strategies that improve GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 performance. The Batch (DeepLearning.AI), March 20 2024b. URL https://www.deeplearning.ai/the-batch/how-agents-can-improve-llm-performance.

- Kasey Panetta. Gartner’s top 10 technology trends 2017. Gartner, October 18 2016. URL https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartners-top-10-technology-trends-2017.

- Bo Peng, Eric Alcaide, Quentin Anthony, Alon Albalak, Samuel Arcadinho, Stella Biderman, Hao Cao, Xin Cheng, Michael Chung, Xingjian Du, Matteo Grella, G. V. Kranthi Kiran, Xuzheng He, Haowen Hou, Jiaxi Lin, Przemysław Kazienko, Jan Kocon, Jiaming Kong, Bartłomiej Koptyra, et al. RWKV: Reinventing RNNs for the transformer era. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pages 14048–14077, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Eric G. Poon, Christy Harris Lemak, Javier C. Rojas, John Guptill, and David Classen. Adoption of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Survey of health system priorities, successes, and challenges. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, 32(7):1093–1100, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Potluri and D. Serikbay. Artificial intelligence (AI) adoption in HR management: Analyzing challenges in kazakhstan corporate projects. International Journal of Asian Business and Information Management, 16(1):1–18, 2025. 1. [CrossRef]

- R. Praveen, A. Shrivastava, G. Sharma, A. M. Shakir, M. Gupta, and S. S. S. R. G. Peri. Overcoming adoption barriers strategies for scalable AI transformation in enterprises. In 2025 International Conference on Engineering, Technology & Management (ICETM), pages 1–6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rob Procter, Peter Tolmie, and Mark Rouncefield. Holding AI to account: Challenges for the delivery of trustworthy AI in healthcare. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 30(2):1–34, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Qian and D. Klabjan. A probabilistic approach to neural network pruning. Technical report, 2021.

- Alec Radford, Jong Wook Kim, Chris Hallacy, Aditya Ramesh, Gabriel Goh, Sandhini Agarwal, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Pamela Mishkin, Jack Clark, Gretchen Krueger, and Ilya Sutskever. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, volume 139, pages 8748–8763, 2021.

- Alec Radford, Jong Wook Kim, Tao Xu, Greg Brockman, Christine McLeavey, and Ilya Sutskever. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, volume 202, pages 28492–28518, 2022.

- C. K. Kumar Reddy. The Power of Agentic AI: In Industry 6.0. Springer, 1 edition, 2025.

- Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using siamese BERT-networks. In EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019 - 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, pages 3982–3992, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reuters, Thomson. What an ERP system is and how it impacts your business, April 15 2025. URL https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/what-is-an-erp-system-and-why-does-it-matter-for-your-business/.

- F. Robert Jacobs and F. C. Ted Weston. Enterprise resource planning (ERP)—a brief history. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2):357–363, 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Romeo and J. Lacko. Adoption and integration of AI in organizations: a systematic review of challenges and drivers towards future directions of research. Kybernetes, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Azad M. Salih, Zahra Raisi-Estabragh, Ilaria B. Galazzo, Petia Radeva, Steffen E. Petersen, Karim Lekadir, and Gloria Menegaz. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Friederike Selten and Bram Klievink. Organizing public sector AI adoption: Navigating between separation and integration. Government Information Quarterly, 41(1):101885, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Shah, J. Soldatos, M. Hinkle, N. Hoher, N. von I. Seip, V. Just, K. Kechichian, K. Benkrid, M. McDonagh, V. Jesaitis, and W. Abbey. Arm AI readiness index, 2024.

- Mahak Sharma, Sunil Luthra, Sudhanshu Joshi, and Anil Kumar. Implementing challenges of artificial intelligence: Evidence from public manufacturing sector of an emerging economy. Government Information Quarterly, 39(4):101624, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Song. Flink agents: The agentic AI framework based on Apache Flink. Community Over Code Asia 2025, July 25 2025. URL https://asia.communityovercode.org/sessions/streaming-913378.html.

- K. Soule and D. Bergmann. IBM Granite 4.0: Hyper-efficient, high performance hybrid models for enterprise. IBM Announcements, October 2 2025. URL https://www.ibm.com/new/announcements/ibm-granite-4-0-hyper-efficient-high-performance-hybrid-models.

- K. M. Stief. Artificial? yes. intelligent? not really, October 1 2025. URL https://www.computing.co.uk/analysis/2025/artificial-yes-intelligent-not-really-copy.

- Suhas Jayaram Subramanya, Rohan Devvrit, Kadekodi, Ravishankar Krishnaswamy, and Harsha Vardhan Simhadri. DiskANN: Fast accurate billion-point nearest neighbor search on a single node. In NeurIPS 2019, 2019. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/diskann-fast-accurate-billion-point-nearest-neighbor-search-on-a-single-node/.

- S. Sumathi. Fundamentals of relational database management systems. Springer, 1 edition, 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Sánchez, R. Calderón, and F. Herrera. Artificial intelligence adoption in SMEs: Survey based on TOE–DOI framework, primary methodology and challenges. Applied Sciences, 15(12):6465, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Araz Taeihagh. Governance of artificial intelligence. Policy and Society, 40(2):137–157, 2021. [CrossRef]

- The Linux Foundation. Linux foundation launches the Agent2Agent protocol project to enable secure, intelligent communication between AI agents, June 23 2025. URL https://www.linuxfoundation.org/press/linux-foundation-launches-the-agent2agent-protocol-project-to-enable-secure-intelligent-communication-between-ai-agents.

- Zhan Tong, Yibing Song, Jue Wang, and Limin Wang. VideoMAE: Masked autoencoders are data-efficient learners for self-supervised video pre-training. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 2022.

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. 2023.

- Gregory Vial, Ann-Frances Cameron, Theodore Giannelia, and Jing Jiang. Managing artificial intelligence projects: Key insights from an AI consulting firm. Information Systems Journal, 33(3):669–691, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, S. Chen, L. Jiang, S. Pan, R. Cai, S. Yang, and F. Yang. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning in large language models: a survey of methodologies. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58(8):1–64, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Wei, Y. Sun, and Y. Li. DeepSeek-OCR: Contexts optical compression. Technical report, October 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.18234.

- Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Brian Ichter, Fei Xia, Ed H. Chi, Quoc V. Le, and Denny Zhou. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 2022.

- S. Williams. Surge in AI adoption amongst sales challenges in Singapore. CFOTech Asia, August 5 2024. URL https://cfotech.asia/story/surge-in-ai-adoption-amongst-sales-challenges-in-singapore.

- World Economic Forum. AI governance trends: How regulation, collaboration, and skills demand are shaping the industry, 2024. URL https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/ai-governance-trends-to-watch/.

- Jie Yang, Yvette Blount, and Alireza Amrollahi. Artificial intelligence adoption in a professional service industry: A multiple case study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 201:123251, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shunyu Yao, Jeffrey Zhao, Dian Yu, Nan Du, Izhak Shafran, Karthik Narasimhan, and Yuan Cao. ReAct: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. In 11th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, 2022.

- YCombinator Hacker News. Is there a half-life for the success rates of AI agents?, June 2025. URL https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=44308711.

- Ted Young and Austin Parker. Learning OpenTelemetry. O’Reilly Media, Incorporated, 1 edition, 2024.

- F. Yu. When AIs judge AIs: The rise of agent-as-a-judge evaluation for LLMs. Technical report, August 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2508.02994.

- Alex L. Zhang. Recursive language models, October 15 2025. URL https://alexzhang13.github.io/blog/2025/rlm/.

- Q. Zhang, Z. Liu, S. Pan, and C. Wang. The rise of small language models. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 40(1):30–37, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yutao Zhu, Hao Yuan, Shujin Wang, Jinyi Liu, Wenjie Liu, Chao Deng, Haonan Chen, Zhicheng Liu, Zhiyuan Dou, and Ji-Rong Wen. Large language models for information retrieval: A survey. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhuge, C. Zhao, D. R. Ashley, W. Wang, D. Khizbullin, Y. Xiong, Z. Liu, E. Chang, R. Krishnamoorthi, Y. Tian, Y. Shi, V. Chandra, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. Agent-as-a-judge: Evaluate agents with agents. Technical report, October 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.10934.

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).