Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAPLIFE | Nanoplasmonic Laser Ignited Fusion Experiment |

| NKFIH | Hungarian National Office for Reseearch, Development and Innovation |

References

- https://www.iter.org (assesed October 26, 2025.).

- Clery, Daniel. Giant international fusion project is in big trouble. ITER operations delayed to 2034, with energy-producing reactions expected 5 years later. Science 2021 Jul.03.

- Beyond Ignition. Science & Technology Review, 2025, July/August https://str.llnl.gov/str-julyaugust2025 (assesed October 26, 2025.).

- Lawson, J.D. Some criteria for a power producing thermonuclear reactor. Proc.Phys.Soc.Lond. Sect.B 1957, 70, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Shawareb, H.; et al. (Indirect Drive ICF Collaboration) Lawson criteria for ignition exceeded in an inertial fusion experiment. Phys.Rev.Lett. 2022, 129, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITER applauds NIF Fusion Breakthrough. ITER Newsline 2022, December 12th.

- Fusion Industry Association Report. https://www.fusionindustryassociation.org.

- Helion Energy. https://www.helionenergy.com/technology.

- Chudokowski, T; et.al. High efficiency of laser energy conversion with cavity pressure acceleration. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21863. [CrossRef]

- Hungarian Office for Research, Development and Innovation, NKFIH. https://nkfih.gov.hu/about-the-office (assesed on October 26, 2025).

- Kroó, N.; Varró, S.; Rácz, P.; Dombi, P. Surface plasmons: a strong alliance of electrons and light. Phys.Scr. 2016, 91, 053010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, S.W.J.; Emmas, E.D.; Gharaibeh, H.F.; Phaneuf, R.A.; Kilayne, A.L.D.; Schlachter, A.S.W.; Shippers, S.; Muller, A.; Chakrabarty, H.S.; Madjet, M.E.; Rost, J.M. Photoexcitation of a Volume Plasmon in C60 Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 065503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, K.E.; Jha, P.K.; Vovorine, D.V.; Genavet, P.; Capasso, F.; Scully, M.O. Quantum-coherence-enhanced surface plasmon amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 043601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroo, N.; Racz, P.; Varro, S. Surface-plasmon-assisted electron pair formation in strong electromagnetic field. Eur. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 67003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronine, D.V.; Huo, W.; Sally, M. Ultrafast dynamics of surface plasmon nanolayers with quantum coherence and external plasmonic feedback. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 114013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernai, L.P.; Kroó, N.; Papp, I. Radiation dominated implosion with nano-plasmonics. Laser and Particle Beams 2018, 36, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernai, L.P.; Csete, M.; Mishustin, I.N.; Motornenko, A.; Papp, I.; Satarov, L.M.; Stöcker, H.; Kroó, N.; (NAPLIFE Collaboration). Radiation dominate dimplosion with flat target. Phys. Wave Phenomena 2020, 28, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, I.; Zsukovszky, K.; (part of NAPLIFE Collaboration). Particle simulation of various gold nanoantennas in laser irradiated matter for fusion production. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

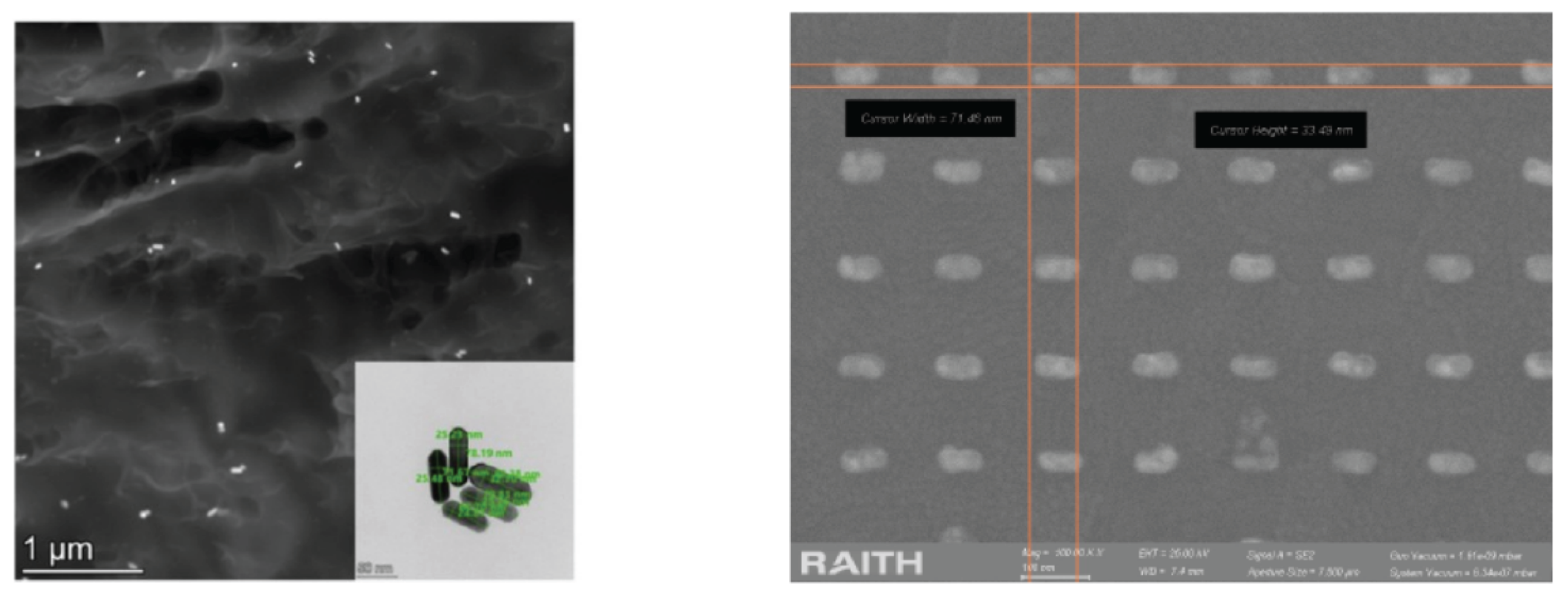

- Bukovszky, K.; Szalóki, M.; Csarnovics, I.; Bonyár, A.; Petrik, P.; Kalas, B.; Daróczi, L.; Kéki, S.; Kökényesi, S.; Hegedus, C. Optimization of plasmonic gold nanoparticle concentration in green LED light active dental photopolymer. Polymers 2021, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasani, S.; Curtin, K.; Wu, N. A review of 2D and 3D plasmonic nanostructure array patterns: fabrication, light management and sensing applications. Nanophotonics 2019, 8, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Tae-In; Oh, Dong Kyo; Kim, San; Park, Jongkyoon; Kim, Yeseul; Mun, Jungho; Kim, Kyujung; Chew, Soo Hoon; Rho, Junsuk; Kim, Seungchul. Deterministic nanoantenna array design for stable plasmon-enhanced harmonic generation. Nanophotonics 2023, 12, 619.

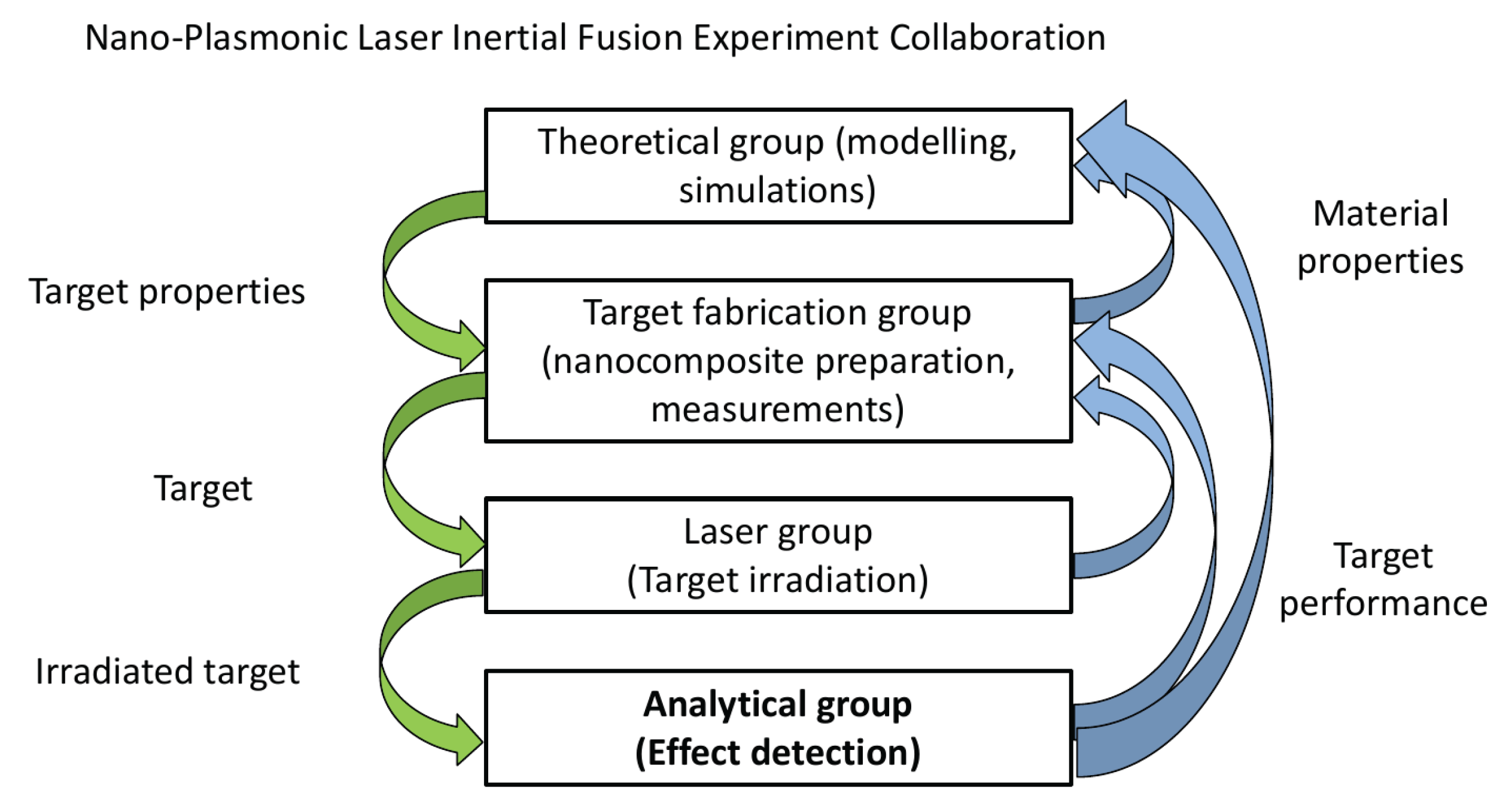

- Biró, T.S.; for the NAPLIFE Collaboration. Nanotechnology and plasmonics for fusion. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroó, N.; Aladi, M.; Kedves, M.; Ráczkevi, B.; Kumari, A.; Rácz, P.; Veres, M.; Galbács, G.; Csernai, L.P.; Biró, T.S.; (NAPLIFE Collaboration). Monitoring of nanoplasmonics assisted deuterium production in a polymer seeded with resonant Au nanorods using in situ femtosecond laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Sci.Rep. 2024, 14, 18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

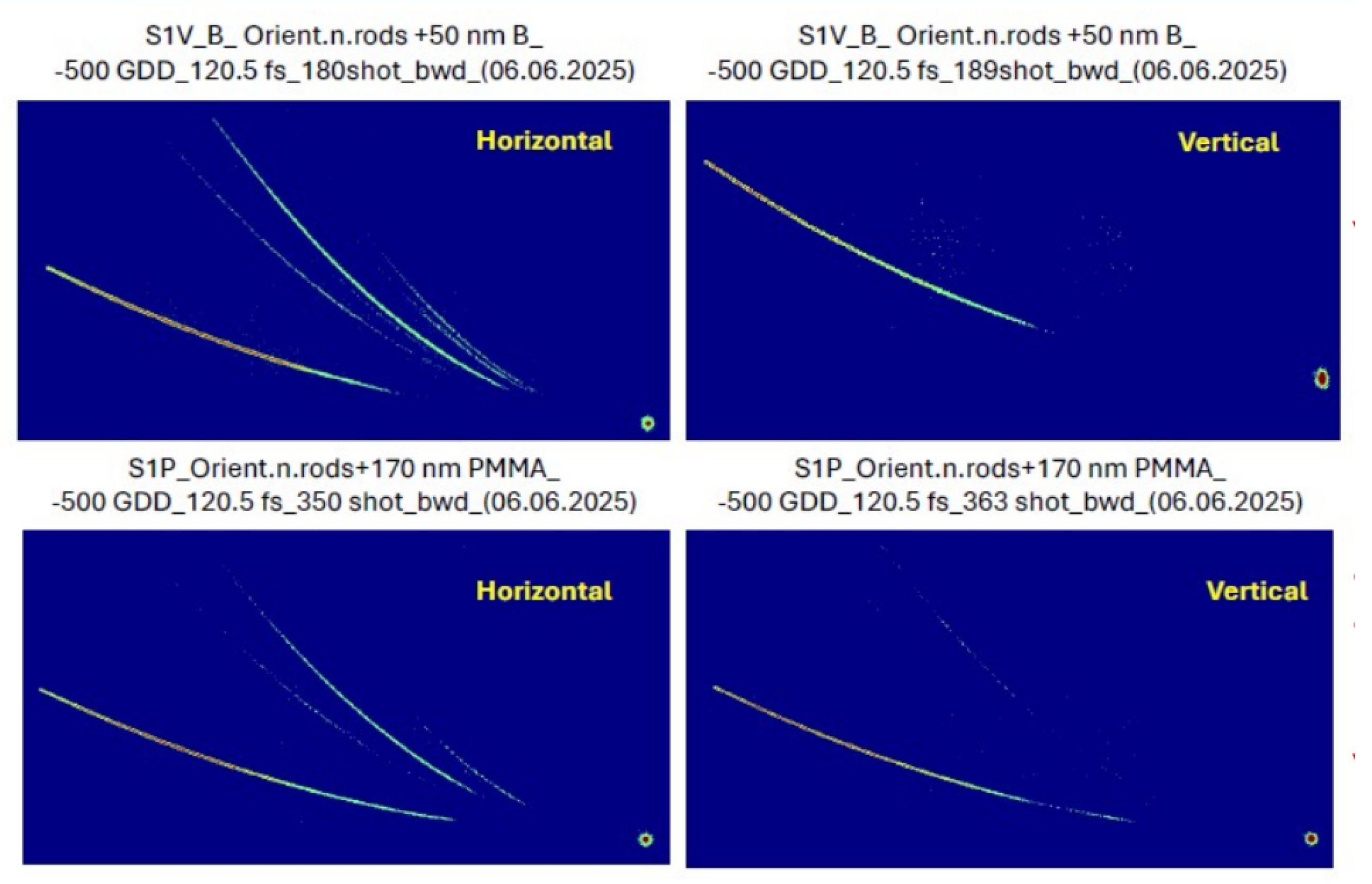

- Rigó, I.; Kámán, J.; Nagyné Szokol, Á.; Holomb, R.; Bonyár, A.; Szalóki, M.; Borók, A.; Zangana, S.; Rácz, P.; Aladi, M.; Kedves, M.Á.; Galbács, G.; Csernai, L.P.; Biró, T.S.; Kroó, N.; Veres, M.; (NAPLIFE Collaboration). Raman spectroscopic characterization of crater walls formed upon single-shot high-energy femtosecond laser irradiation of dimethacrylate polymer doped with plasmonic gold nanorods. Sci.Rep. 2025, 15, 14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

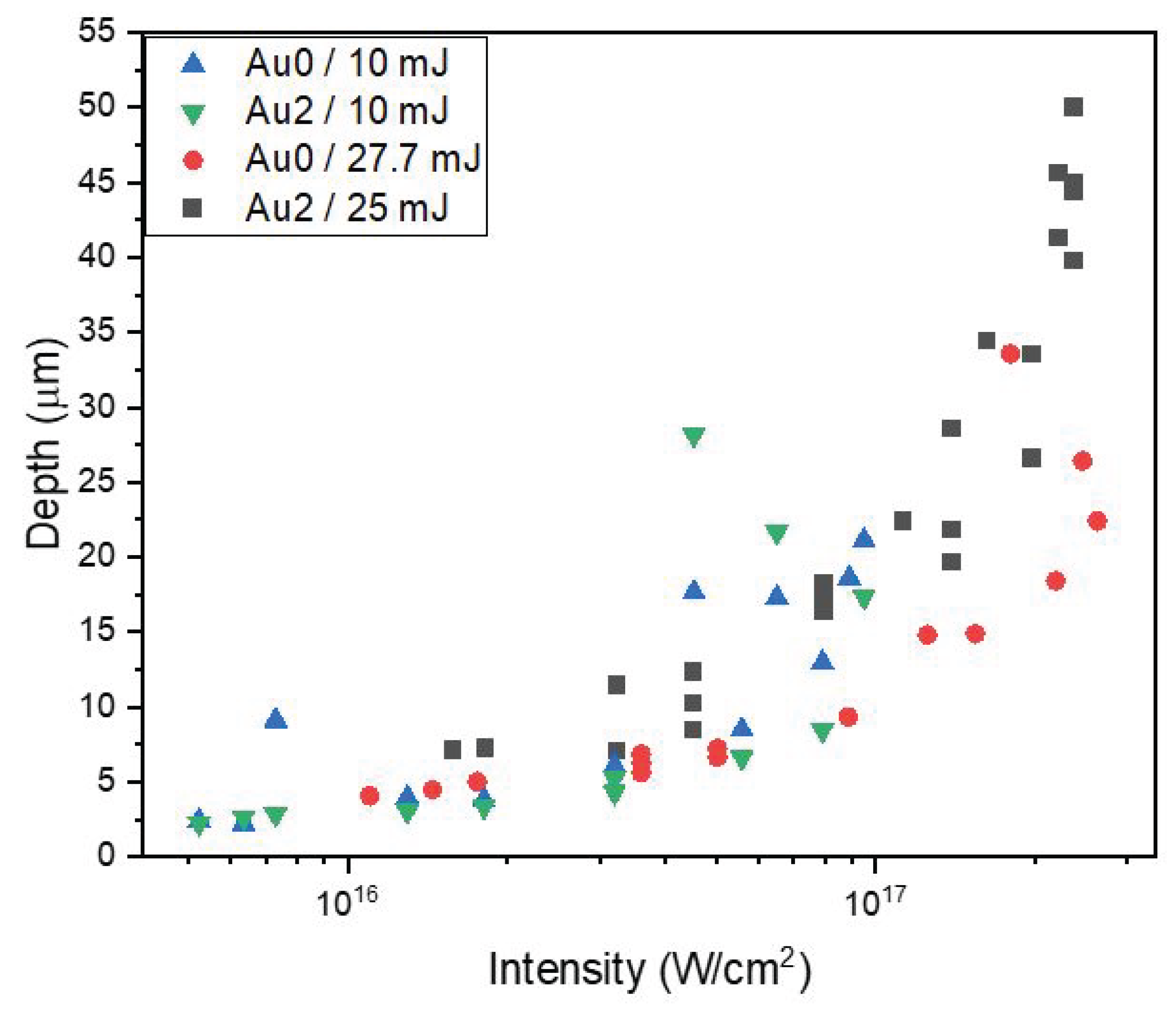

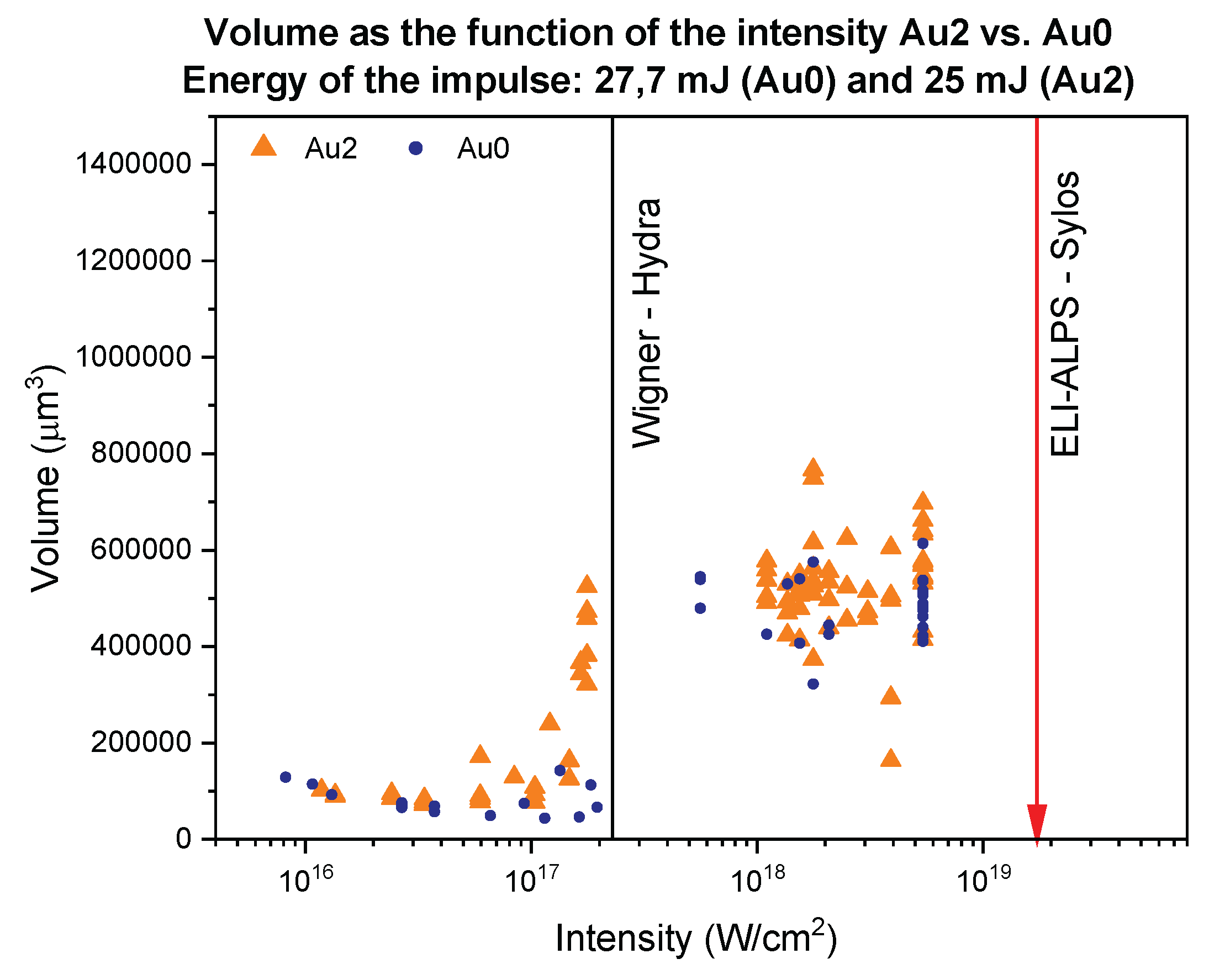

- Nagyné Szokol, Á.; Kámán, J.; Holomb, R.; Rigó, I.; Aladi, M.; Kedves, M.; Ráczkevi, B.; Rácz, P.; Bonyár, A.; Borók, A.; Zangana, S.; Szalóki, M.; Papp, I.; Galbács, G.; Biró, T.S.; Csernai. L.P.; Kroó, N.; Veres, M.; (NAPLIFE Collaboration). Morphology studies on craters created by femtosecond laser irradiation in UDMA polymer targets embedded with plasmonic gold nanorods. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 3007.

- Casian-Plaza, F.A.; Janovszky, P.M.; Palásti, D.J.; Kohut, A.; Geretovszky, Z.; Kopniczky, J.; Schubert, F.; Zivkovic, S.; Galbács, Z.; Galbács, G. Comparison of three nanoparticle deposition techniques potentially applicable to elemental mapping by nanoparticle-enhanced laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 657, 159844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kámán, J. private communication, 2023.

- Bonyár, A. private communication, 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deuterium (accessed on 25. 10. 2025.).

- Sikora, M.H.; Weber, H.R. A new evaluation of the 11B(p,α)αα reaction rates. J. Fusion Energy 2016, 35, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, R.M.; Ogawa, K.; Tajima, T.; Allfrey, I.; Gota, H.; McCaroll, P.; Oholachi, S.; Isobe, M.; Kamio, S.; Klumper, V.; Nuga, H.; Shoji, M.; Ziaei, S.; Binderbauer, H.W.; Osakabe, M. First measurement of p11B fusion in magnetically confined plasma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Wu, D.; Hu, T.X.; Liang, T.Y.; Niag, X.C.; Liang, J.H.; Liu, Y.C.; Liu, P.; Liu, X.; Sheng, Z.M.; Zhao, Y.T.; Hoffmann, D.H.H.; He, K.T.; Zhanf, J. Proton-boron fusion scheme taking into account the effects of target degeneracy. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 013323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

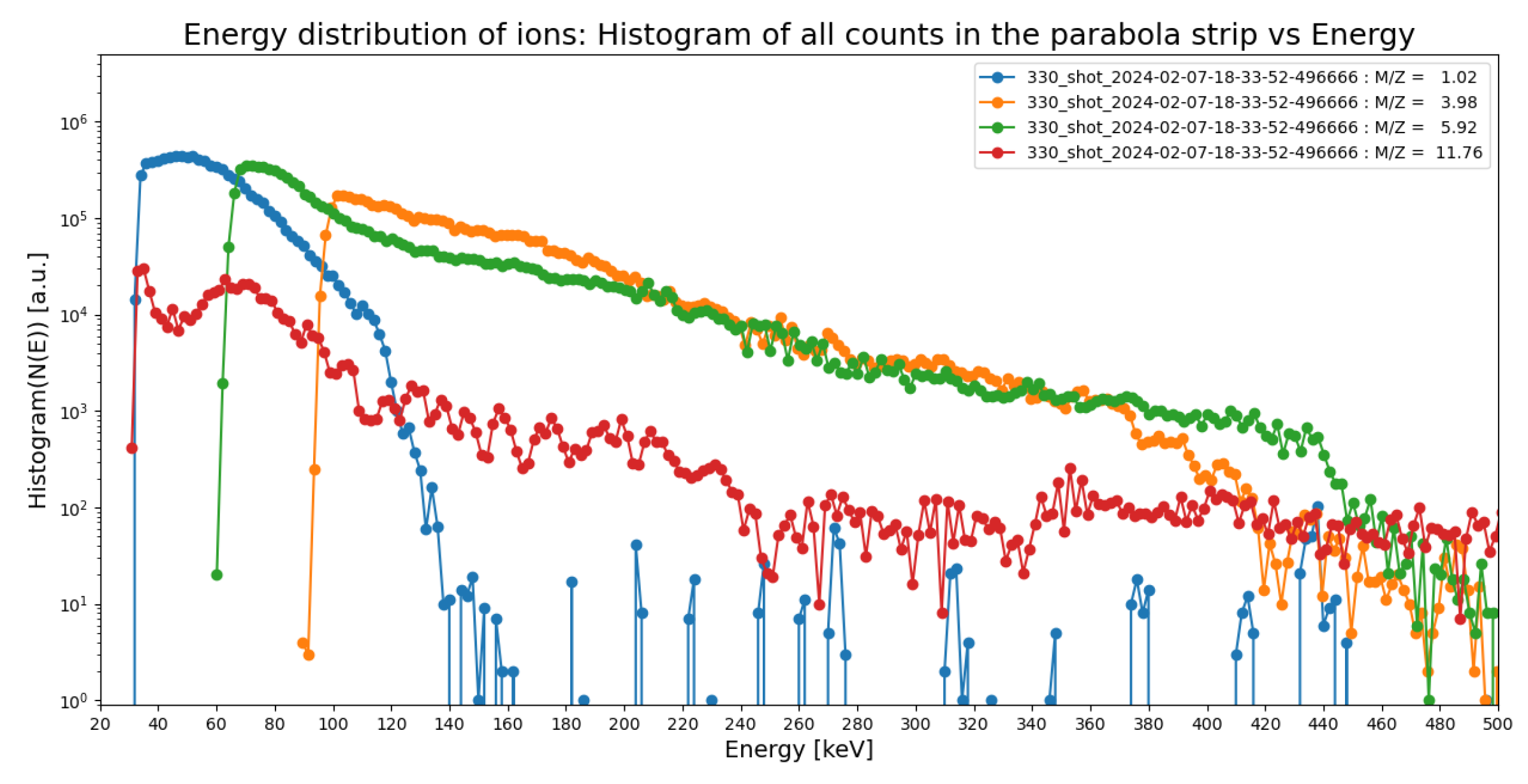

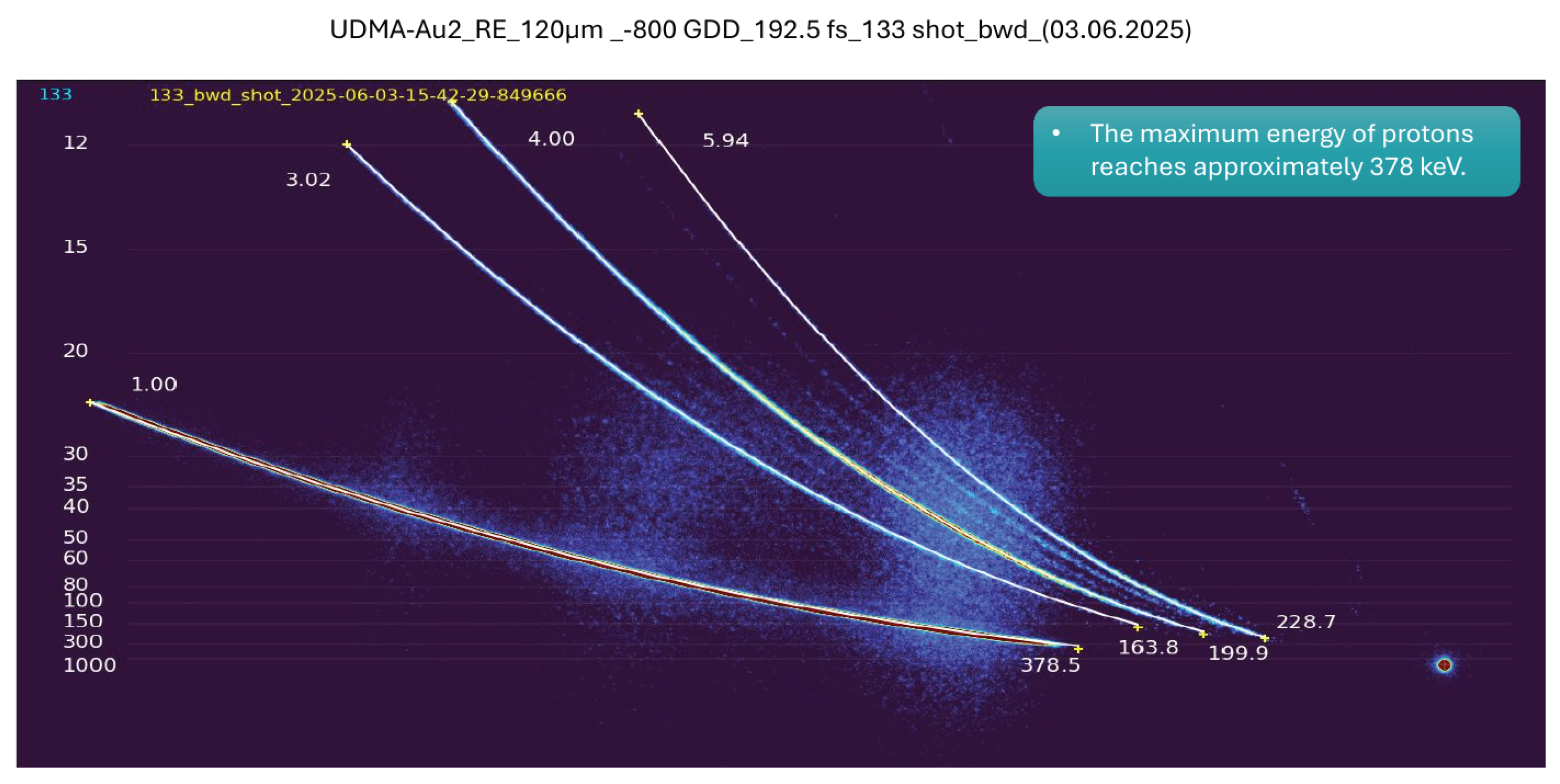

- Kroó, N.; Csernai, L.P.; Papp, I.; Kedves, M.A.; Aladi, M.; Bonyár, A.; Szalóki, M.; Osvay, K.; Varmazyar, P.; Biró, T.S.; (NAPLIFE Collaboration). Indication of p+11B reaction in laser induced nanofusion experiment. Sci.Rep. 2024, 14, 30087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, Gabriel. Aneutronic Nuclear Fusion Energy (and references therein). 2022. https://large.stanford.edu/courses/2022/ph241/ruiz2 (assesed October 26, 2025.).

- G. Gamow. Zur Quantentheorie des Atomkernes. Zeitcshrift für Physik 1928, 51, 204.

- Yoon, Jin-Hee Yoon; Wong, Cheuk-Yin. Relativistic Modification of the Gamow Factor. Phys. Rev. C 1999, 61, 044905.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).