Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

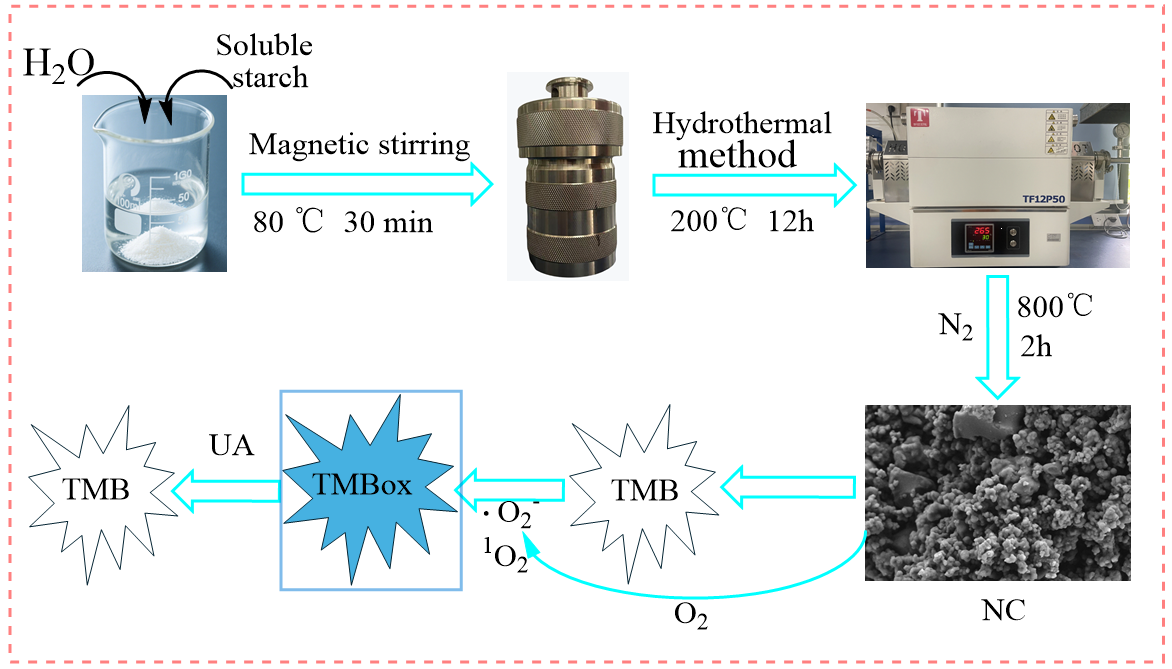

2.2. Preparation of Starch-Based Nitrogen-Doped Biochar

2.3. Colorimetric Determination of UA

2.4. Pretreatment of Human Serum and Urine

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of NC

3.2. Feasibility of UA Colorimetric Assay

- Centrifuge tube a: 200 μL H2O2 (200 μmol·L-1).

- Centrifuge tube b: 200 μL H2O2 (200 μmol·L-1), 60 μL TMB (8 mmol·L-1).

- Centrifuge tube c: 60 μL TMB (8 mmol·L-1), 8 mg NC.

- Centrifuge tube d: 200 μL H2O2 (200 μmol·L-1), 60 μL TMB (8 mmol·L-1), 8 mg NC.

- Centrifuge tube e: 60 μL TMB (8 mmol·L-1), 8 mg NC.

- No absorption at 652 nm was observed in the H2O2 system (Figure 4a).

- The colorless solution and a minimal A652 nm were observed in the H2O2 + TMB system (Figure 4b), confirming the limited oxidizing capacity of H2O2 toward TMB.

- The addition of UA to the filtrate of the TMB + NC system resulted in a significant decrease in A652 nm and a lighter color of the solution (Figure4f). This indicates that UA could reduce blue TMBox to colorless TMB and confirms the feasibility of utilizing the reduction in A652 nm of TMBox for the colorimetric detection of UA concentration.

3.3. Optimization of Color Development Conditions and Stability

3.4. Optimization of UA Reduction Time

3.5. Stability of NC

3.6. Linear Response Range and Sensitivity for UA Sensing

3.7. Selectivity of UA Sensing

3.8. UA Detection Mechanism

3.9. Actual Urine Sample Testing

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.; Wen, X.; Kong, J. Recent Progress on Uric Acid Detection: A Review. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 50, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Jiang, N.; Sun, X.; Kong, L.; Liang, T.; Wei, X.; Wang, P. Progress in Optical Sensors-Based Uric Acid Detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2023, 237, 115495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Arakawa, H.; Tamai, I. Uric Acid in Health and Disease: From Physiological Functions to Pathogenic Mechanisms. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2024, 256, 108615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Gao, J. Hyperuricemia and Its Related Diseases: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, A.P.; Lopez-Candales, A. Uric Acid and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Reappraisal. Postgraduate Medicine 2024, 136, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copur, S.; Demiray, A.; Kanbay, M. Uric Acid in Metabolic Syndrome: Does Uric Acid Have a Definitive Role? European Journal of Internal Medicine 2022, 103, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Jia, X.; Liu, H.; Wei, M.; Lyu, Z. Effects of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors on Serum Uric Acid in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2022, 24, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhong, J.; Lai, J.; Peng, Z.; Lian, T.; Tang, X.; Li, P.; Qiu, P. Enhancing Catalytic Performance of Fe and Mo Co-Doped Dual Single-Atom Catalysts with Dual-Enzyme Activities for Sensitive Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide and Uric Acid. Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1273, 341543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Z. Rational Atomic Engineering of Prussian Blue Analogues as Peroxidase Mimetics for Colorimetric Urinalysis of Uric Acid. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 6211–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, P.; Ma, G.; Song, Z.; Tang, B.Q.; Li, T. Simultaneous Determination of Cellular Adenosine Nucleotides, Malondialdehyde, and Uric Acid Using HPLC. Biomedical Chromatography 2021, 35, e5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Kang, D.; Jin, C.H.; Shi, Q.; Jin, T.; Inoue, K.; Todoroki, K.; Toyo’oka, T.; et al. Human Nails Metabolite Analysis: A Rapid and Simple Method for Quantification of Uric Acid in Human Fingernail by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with UV-Detection. Journal of Chromatography B 2015, 1002, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, T.; Wang, T. Influence of Boron Doped Level on the Electrochemical Behavior of Boron Doped Diamond Electrodes and Uric Acid Detection. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2016, 494, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Peng, H.; Qi, R.; Luo, C. A Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with MoS2 Nanosheets and Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene) for Simultaneous Electrochemical Detection of Ascorbic Acid, Dopamine and Uric Acid. Microchim Acta 2016, 183, 2517–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravčík, O.; Dvořák, M.; Kubáň, P. Autonomous Capillary Electrophoresis Processing and Analysis of Dried Blood Spots for High-Throughput Determination of Uric Acid. Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1267, 341390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Luo, Y.-X.; Liu, W.-P.; Li, Y.-S.; Gao, X.-F. Enzyme-Free Fluorescence Determination of Uric Acid and Trace Hg(II) in Serum Using Si/N Doped Carbon Dots. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2021, 263, 120182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, L.; Lu, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. A Dual-Signal Colorimetric and Ratiometric Fluorescent Nanoprobe for Enzymatic Determination of Uric Acid by Using Silicon Nanoparticles. Microchim Acta 2019, 186, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Xia, S.; Sang, X.; Zeid, A.M.; Hussain, A.; Li, J.; Xu, G. Enhanced Luminol Chemiluminescence with Oxidase-like Properties of FeOOH Nanorods for the Sensitive Detection of Uric Acid. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 3267–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Su, Y.; Duan, Y.; Chen, S.; Zuo, W. A Nanocomposite Prepared from Copper(II) and Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Quantum Dots with Peroxidase Mimicking Properties for Chemiluminescent Determination of Uric Acid. Microchim Acta 2019, 186, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Qi, F.; Niu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Pan, J. Uricase-Free on-Demand Colorimetric Biosensing of Uric Acid Enabled by Integrated CoP Nanosheet Arrays as a Monolithic Peroxidase Mimic. Analytica Chimica Acta 2018, 1021, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; Pelt, S. van Enzyme Immobilisation in Biocatalysis: Why, What and How. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6223–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernerová, A.; Krčmová, L.K.; Heneberk, O.; Radochová, V.; Strouhal, O.; Kašparovský, A.; Melichar, B.; Švec, F. Chromatographic Method for the Determination of Inflammatory Biomarkers and Uric Acid in Human Saliva. Talanta 2021, 233, 122598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, N.; Ajmal, R.; Afzal, A. Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Sensors for Accurate and Accessible Uric Acid Detection. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 097505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, G.; Mu, X.; Zhao, S.; Tian, J. Simple Enzyme-Free Detection of Uric Acid by an in Situ Fluorescence and Colorimetric Method Based on Co-PBA with High Oxidase Activity. Analyst 2024, 149, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xie, C.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y. Enzyme-Free Colorimetric Assay for the Detection of Uric Acid in Urine by Cobalt Tetroxide. Microchemical Journal 2024, 204, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Tang, X.; Xu, P.; Qiu, P. Calcium Fluoride/Manganese Dioxide Nanocomposite with Dual Enzyme-like Activities for Uric Acid Sensing: A Comparative Study of Enzyme and Nonenzyme Methods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yuan, C.; Geng, G.; Shi, R.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y. Enzyme-Free Colorimetric Determination of Uric Acid Based on Inhibition of Gold Nanorods Etching. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 333, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadi, M.; Hallaj, T.; Nasirloo, E. In Situ Formation of Ag/Au Nanorods as a Platform to Design a Non-Aggregation Colorimetric Assay for Uric Acid Detection in Biological Fluids. Microchemical Journal 2020, 154, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Qin, S.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Enzyme-Free Colorimetric Detection of Uric Acid on the Basis of MnO2 Nanosheets - Mediated Oxidation of 3, 3′, 5, 5′- Tetramethylbenzidine. Microchemical Journal 2023, 190, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, T.; Chen, J.; Tang, X.; Qiu, P.; Hu, Y. Bifunctional Fe-MOF@Fe3O4NPs for Colorimetric and Ratiometric Fluorescence Detection of Uric Acid in Human Urine. Microchemical Journal 2024, 196, 109538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Song, D. A Pure Near-Infrared Platform with Dual-Readout Capability Employing Upconversion Fluorescence and Colorimetry for Biosensing of Uric Acid. Talanta 2025, 291, 127900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ruditskiy, A.; Xia, Y. Rational Design and Synthesis of Noble-Metal Nanoframes for Catalytic and Photonic Applications.

- Wang, Y.-L.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chou, C.-L.; Chang, Y.-S.; Liu, W.-C.; Chiu, H.-W. Oxidative Stress and Potential Effects of Metal Nanoparticles: A Review of Biocompatibility and Toxicity Concerns. Environmental Pollution 2024, 346, 123617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, J.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, Y. Magnetic Microsphere to Remove Tetracycline from Water: Adsorption, H2O2 Oxidation and Regeneration. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 330, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, M.; Su, X.; Sun, J. High-Efficiency Degradation of Organic Pollutants with Fe, N Co-Doped Biochar Catalysts via Persulfate Activation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 397, 122764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.-M.; Chen, C.-W.; Huang, C.-P.; Dong, C.-D. N-Doped Metal-Free Biochar Activation of Peroxymonosulfate for Enhancing the Degradation of Antibiotics Sulfadiazine from Aquaculture Water and Its Associated Bacterial Community Composition. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Peng, W. Facile Synthesis of Iron Oxide Supported on Porous Nitrogen Doped Carbon for Catalytic Oxidation. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 785, 147296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Cui, K.; Cui, M.; Ding, Y.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Li, X. Enhanced Norfloxacin Degradation by Iron and Nitrogen Co-Doped Biochar: Revealing the Radical and Nonradical Co-Dominant Mechanism of Persulfate Activation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 420, 129902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Dong, X.; Xie, C.; Xiao, C.; Wu, Y.; Shoulian, W. Preparation of Nitrogen-Doped Magnetic Carbon Microspheres and Their Adsorption and Degradation Properties of Tetracycline Hydrochloride. Chemical Engineering Science 2024, 300, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, X.J.; Zhu, Y.; Muhammad, F.; Tan, S.; Cao, W.; Lin, S.; Jin, Z.; Gao, X.; Wei, H. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanomaterials as Highly Active and Specific Peroxidase Mimics. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6431–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Wang, X.; Qin, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, H. Nucleobase-Mediated Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanozymes as Efficient Peroxidase Mimics. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 1993–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Xi, J.; Fan, L.; Wang, P.; Zhu, C.; Tang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, M.; Jiang, B.; Yan, X.; et al. In Vivo Guiding Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanozyme for Tumor Catalytic Therapy. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ge, M.; Wang, S. Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbon Nanomaterials Synthesized Using a Magadiite Template as Efficient Peroxidase Mimics for Colorimetric Detection of Ascorbic Acid as an Antioxidant. ANAL. SCI. 2023, 39, 1727–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, J.; Pang, J.; Cao, G.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Feng, X.; Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Sub-Millisecond Lithiothermal Synthesis of Graphitic Meso–Microporous Carbon. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Fan, S.; Xu, H. Effect of Fe–N Modification on the Properties of Biochars and Their Adsorption Behavior on Tetracycline Removal from Aqueous Solution. Bioresource Technology 2021, 325, 124732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Z.-H.; Shao, L.; Chen, J.-J.; Bao, W.-J.; Wang, F.-B.; Xia, X.-H. Catalyst-Free Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Graphene via Thermal Annealing Graphite Oxide with Melamine and Its Excellent Electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4350–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, K.; Du, F.; Xia, Z.; Durstock, M.; Dai, L. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotube Arrays with High Electrocatalytic Activity for Oxygen Reduction. Science 2009, 323, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Liao, Z.; Zeng, M.; Zhong, J.; Tang, X.; Qiu, P. Rapid Colorimetric Detection of H2O2 in Living Cells and Its Upstream Series of Molecules Based on Oxidase-like Activity of CoMnO3 Nanofibers. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2023, 382, 133540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, N.; Wen, J.; Yang, D.; Chen, H.; Long, Y.; Zheng, H. Detecting Uric Acid Base on the Dual Inner Filter Effect Using BSA@Au Nanoclusters as Both Peroxidase Mimics and Fluorescent Reporters. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2023, 293, 122504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, F.; Plessas, A.K.; Economou, A.; Thomaidis, N.; Papaefstathiou, G.S.; Kokkinos, C. Graphite Paste Sensor Modified with a Cu(II)-Complex for the Enzyme-Free Simultaneous Voltammetric Determination of Glucose and Uric Acid in Sweat. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2022, 917, 116393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipekci, H.H. Holey MoS2-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Simultaneous Dopamine and Uric Acid Detection. Anal. Methods 2023, 15, 2989–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Qin, C. Degradation of P-Nitrophenol Using a Ferrous-Tripolyphosphate Complex in the Presence of Oxygen: The Key Role of Superoxide Radicals. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2019, 259, 118030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Enzyme | Linear Range (μmol·L-1) | LOD (μmol·L-1) | Detection Time (min) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe/Mo DSACs | uricase | 0.5-200 | 0.13 | 45 | [8] |

| TMB-CoP/NF | peroxidase mimic | 1-200 | 1.00 | 40 | [19] |

| CaF2/MnO2 | uricase | 0.3-70 | 0.137 | 55 | [25] |

| CoMnO3 | uricase | 0.6-200 | 0.38 | 25 | [47] |

| BSA@Au nanoclusters | uricase | 0.5-50 | 0.39 | 75 | [48] |

| CaF2/MnO2 | no enzyme | 0.1~30 | 0.039 | 3 | [25] |

| AuNRs-MnO2-KI | no enzyme | 0.8~30 30~300 |

0.76 2.04 |

15 | [26] |

| Ag/Au nanorods | no enzyme | 0.1~1.0 | 0.065 | 2 | [27] |

| MnO2 nanosheets | no enzyme | 0.5~30 | 0.21 | 20 | [28] |

| Cu(II)-complex | no enzyme | 50-500 | 4.6 | 6 | [49] |

| Holey MoS2 | no enzyme | 400-7000 | 5.62 | 0.8 | [50] |

| NC | no enzyme | 10-500 | 4.87 | 25 | This work |

| Samples | Measurement Results (μmol·L-1) | Measured Quantity Average (μmol·L-1) | Marked Quantity (μmol·L-1) | Total Amount Measured (μmol·L-1) | Recovery rate (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum 1 | 380.25 376.36 385.49 |

380.70 | 100 | 476.20 | 95.5 | 1.20 |

| Serum 2 | 260.28 251.37 262.16 |

257.94 | 100 | 360.13 | 102.2 | 2.23 |

| Serum 3 | 302.60 308.58 303.20 |

307.46 | 100 | 406.31 | 98.9 | 1.43 |

| Urine 1 | 316.54 322.22 327.30 |

322.02 | 100 | 425.65 | 103.6 | 1.67 |

| Urine 2 | 164.44 174.44 170.03 |

169.64 | 100 | 267.78 | 98.14 | 2.95 |

| Urine 3 | 246.60 238.56 242.22 |

242.46 | 100 | 340.25 | 97.8 | 1.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).