Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

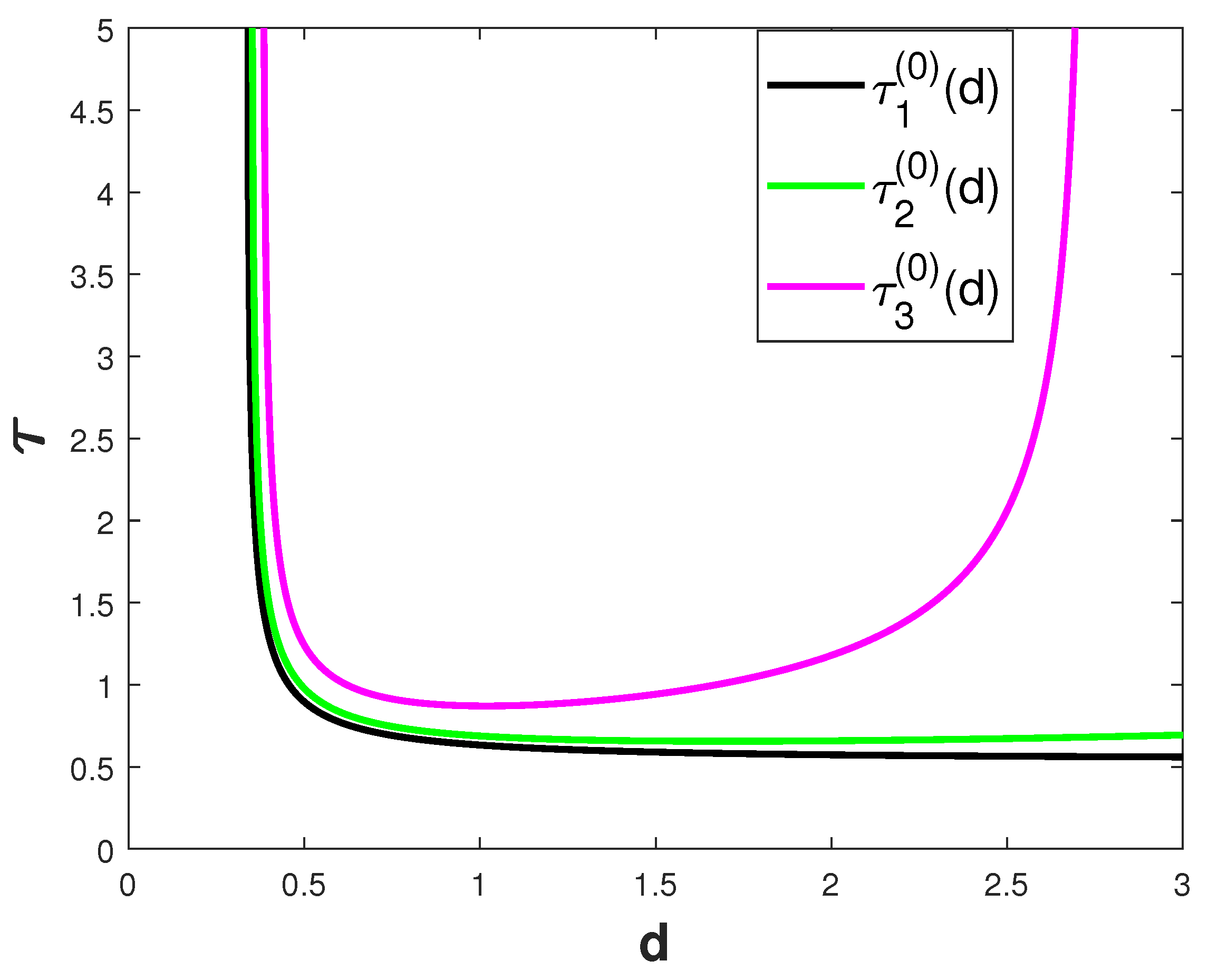

2. Stability and Bifurcations Analysis

3. Property of Bifurcating Periodic Solutions

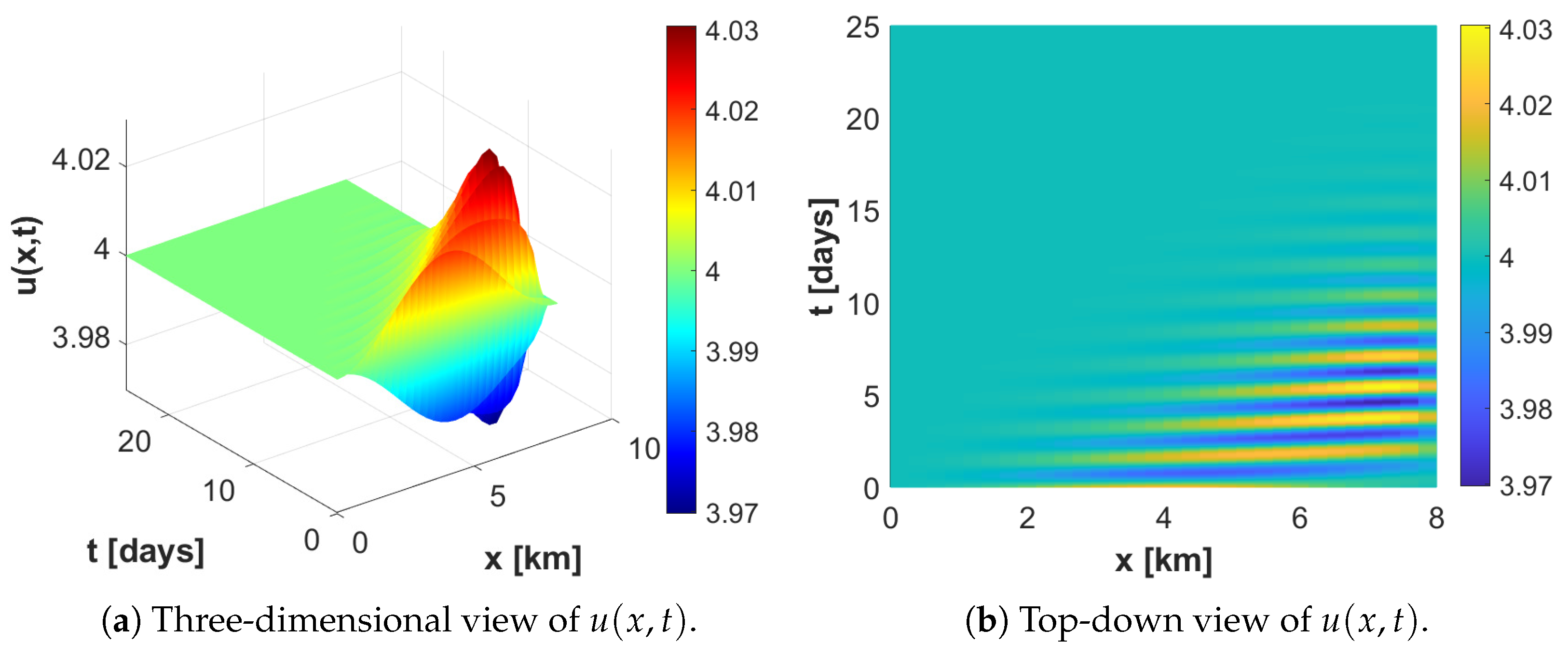

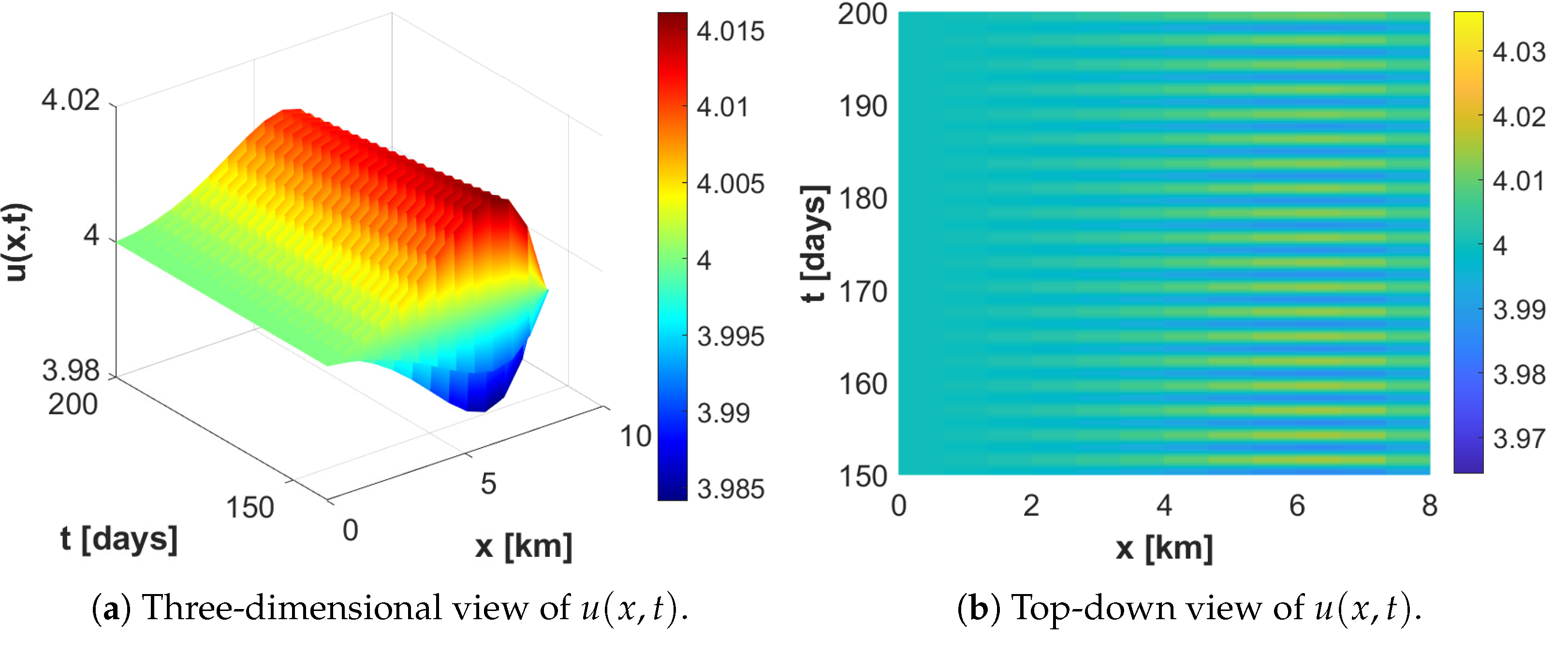

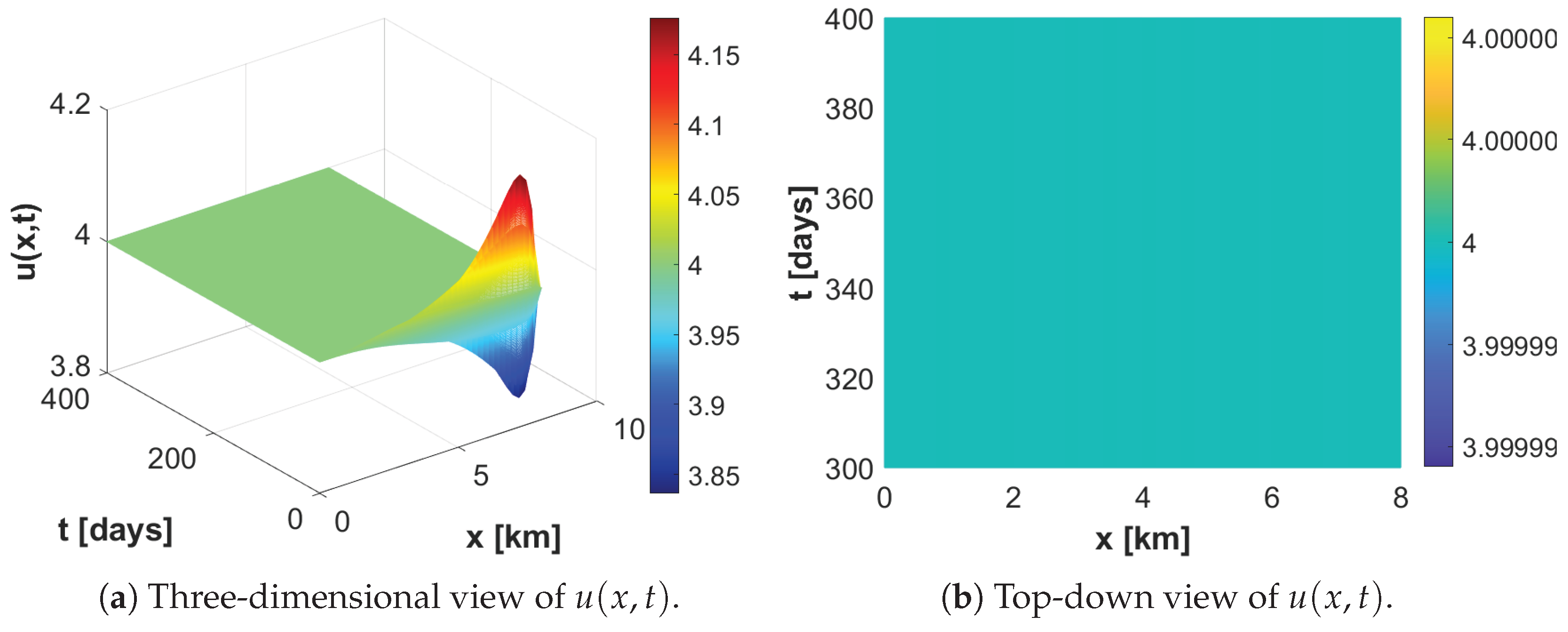

4. Numerical Simulations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allee, W.C. Animal Aggregations: A study in General Sociology; Publisher: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. A.; Petrovskii, S. V.; Potts, R. The Mathematics Behind Biological Invasions; Publisher: Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2016.

- Courchamp, F.; Berec, L.; Gascoigne, J. Allee Effect in Ecology and Conservation; Oxford University Press, NY, USA,2008.

- Jankovic, M.; Petrovskii, S. Are time delays always destabilizing? revisiting the role of time delays and the Allee effect. Theor. Ecol. 2014, 7, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Wei, J. Dynamics and pattern formation in a diffusive predator prey system with strong Allee effect in prey. J. Differ. Equ. 2011, 251, 1276–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Basir, F.A.; Ray, S. Additive Allee effect of top predator in a mathematical model of three species food chain. Energ. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 6(5), 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu. Y.; Wei, J. Double Hopf bifurcation of a diffusive predator-prey system with strong Allee effect and two delays. Nonlin. Anal. Model. Control. 2021, 26, 72–92. [CrossRef]

- Beretta, E.; Kuang, Y. Convergence results in a well-known delayed predator-prey system. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1996, 204, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, K.L.; Grossman, Z. Discrete delay, distributed delay and stability switches. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1982, 86, 592–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shi, J.; Wei, J. The effect of delay on a diffusive predator-prey system with holling type-II predator functional response. Commun. Pure Appl. Anal. 2013, 12, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dai, B.; Zou, X. Stability and bifurcation of a reaction-diffusion-advection model with nonlinear boundary condition. J. Differ. Equ. 2023, 363, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.; Fatma, R. Diffusion-driven instability and bifurcation in the predator–prey system with Allee effect in prey and predator harvesting. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2024, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wei, J.; Zhang, X. Bifurcation analysis for a delayed diffusive logistic population model in the advective heterogeneous environment. J. Dynam. Differ. Equ. 2020, 32, 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Lutscher, F. Evolution of dispersal in open advective environments. J. Math. Biol. 2014, 69, 1319–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Pham, V.T.; Alam, Z. Bifurcation analysis and circuit realization for multiple-delayed Wang–Chen system with hidden chaotic attractors. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 85, 1635–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zheng, S.; Alam, Z. Dynamics analysis and cryptographic application of fractional logistic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 96(1), 615–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shi, J. Stability and Hopf bifurcation in a diffusive logistic population model with nonlocal delay effect. J. Differential Equations. 2012, 253(12), 3440–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.P.; Zhang, C.H. Properties of Hopf bifurcation to a reaction-diffusion population model with nonlocal delayed effect. J. Differential Equations. 2024, 385, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfifi, H.Y. Stability analysis and Hopf bifurcation for two-species reaction-diffusion-advection competition systems with two time delays. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 474, 128684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, S. Bifurcation and stability of a reaction-diffusion-advection model with nonlocal delay effect and nonlinear boundary condition. Nonlinear Anal.-Real World Appl. 2024, 78, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).