Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. NMR Method of µ(X) Measurements

2.2. Gas Phase NMR Measurements

2.3. State-Of-The-Art Quantum Mechanical Computations

2.4. Absolute Shielding Scales

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| NMM | Nuclear Magnetic Moment |

Appendix A

| Isotope | μlength/μN | gX | γ(X)×107 s-1T-1 | γ(X)/2π MHzT-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | +4.837353498(1) | +5.585694689(2) | +26.752218759(8) | 42.57747854(1) |

| 2H | +1.212600779(3) | +0.857438234(2) | +4.10662889(1) | 6.53590288(2) |

| 3H | +5.159714352(2) | +5.95792494(2) | +28.53498451(1) | 45.4148384(2) |

| 3He | +3.685155205(3) | +4.255250700(3) | +20.38016826(1) | +32.43604519(2) |

| 10B | +2.0789963(9) | +0.6001545(3) | +2.8743899(1) | +4.574734(2) |

| 11B | +3.470681(1) | +1.7922521(7) | +8.583842(4) | +13.661609(6) |

| 13C | +1.216540(1) | +1.404739(1) | +6.727879(7) | +10.70775(1) |

| 14N | +0.5707394(1) | +0.40357368(7) | +1.9328824(3) | +3.076278(1) |

| 15N | -0.49027068(5) | -0.56611582(6) | -2.711364(3) | -4.3152706(5) |

| 17O | -2.240482(2) | -0.7574212(8) | -3.627605(4) | -5.773512(6) |

| 19F | +4.55241(2) | +5.25667(2) | +25.1764(1) | +40.0695(2) |

| 21Ne | -0.854351(1) | -0.4411849(7) | -2.113018(3) | -3.362973(5) |

| 29Si | -0.961378(2) | -1.110103(2) | -5.31675(1) | -8.46187(2) |

| 31P | +1.958819(8) | +2.26185(1) | +10.83294(5) | +17.241156(8) |

| 33S | +0.830439(2) | +0.428837(1) | +2.053879(3) | +0.32688500(5) |

| 35Cl | +1.060837(7) | +0.547814(3) | +2.62371(2) | +4.17576(3) |

| 37Cl | +0.883036(5) | +0.455998(3) | +2.18396(1) | +3.47589(2) |

| IX | Nucleus example | |

|---|---|---|

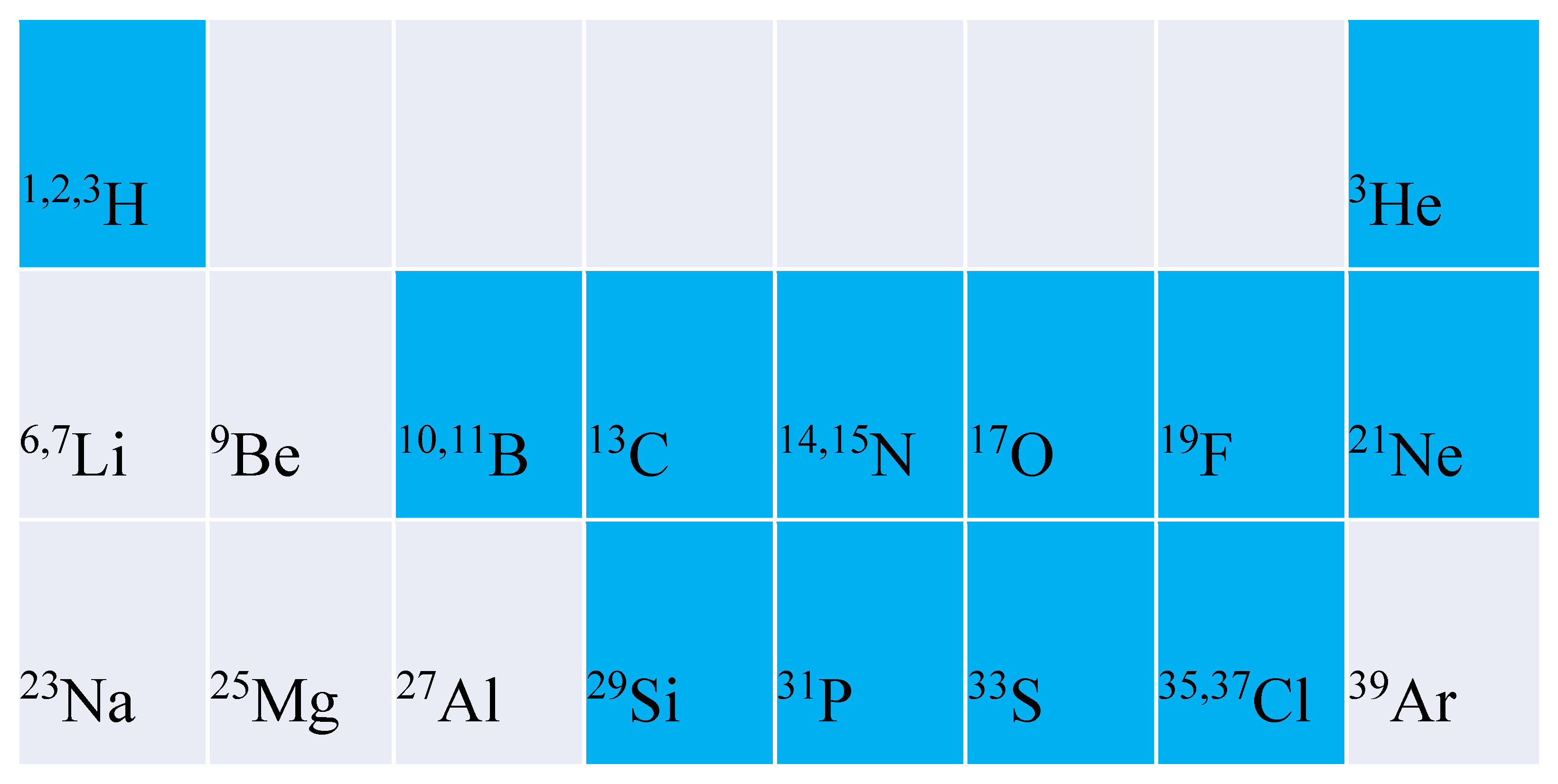

| 1/2 | 1H,3H,3He,13C,15N,19F,29Si,31P | 1.7320508076 |

| 1 | 2H,14N | 1.4142135624 |

| 3/2 | 11B,21Ne,33S,35Cl,37Cl | 1.2909944487 |

| 2 | 204Tl | 1.2247448714 |

| 5/2 | 17O | 1.1832159566 |

| 3 | 10B | 1.1547005384 |

| 7/2 | 39Ar,45Sc,49Ti,51V | 1.1338934190 |

| 4 | 40K | 1.1180339887 |

| 9/2 | 73Ge,83Kr | 1.1055415968 |

References

- Jaszuński M., Antušek A., Garbacz P., Jackowski K., Makulski W., Wilczek M., The determination of accurate nuclear magnetic dipole moments and direct measurement of NMR shielding constants, Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc., 2012, 67, 49-63. [CrossRef]

- Antušek A., Jackowski K., Jaszuński M., Makulski W., Wilczek M., Nuclear magnetic dipole moments from NMR spectra, Chem. Phys. Lett., 2005, 411, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Jackowski K., Wilczek M., Measurements of Nuclear Magnetic Shielding in Molecules, Molecules, 2024, 29, 2617. [CrossRef]

- Antušek A., Jaszuński M., Accurate Nonrelativistic Calculations of NMR Shielding Constants, in Gas Phase NMR, Eds.: Jackowski K. & Jaszuński M., RSC., London, § 6., 2016. pp. 186-217. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Deuterium isotope effects on 17O nuclear shielding in a single water molecule from NMR gas phase measurements”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2020, 22, 17777-17780. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Aucar J.J., Aucar G.A., Ammonia: the molecule for establishing 14N and 15N absolute shielding scales and a source of information on nuclear magnetic moments, J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 157(8), 084306. [CrossRef]

- Jackowski K., Makulski W., Szyprowska A., Antušek A., Jaszuński M., Jusélius J., NMR shielding constants in BF3 and magnetic dipole moments of 10B and 11B nuclei, J. Chem. Phys., 2009, 130, 044309. [CrossRef]

- Jaszuński M., Repisky M., Demissie T.B., Komorovsky S., Malkin E., Ruud K., Garbacz P., Jackowski K., Makulski W., Spin-rotation and NMR shielding constants in HCl, J. Chem. Phys., 2013, 139, 234302-1-6. [CrossRef]

- Garbacz P., Jackowski K., Makulski W., Wasylishen R.E., Nuclear Magnetic Shielding for Hydrogen in Selected Isolated Molecules, J. Phys. Chem.A, 2012, 116, 11896. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Absolute 13C Nuclear Magnetic Shielding of Simple Isolated Molecules from Gas Phase Measurements, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2022, 24, 8950-8961. [CrossRef]

- Jameson C.J., Fundamental Intramolecular and Intermolecular Information from NMR in Gas Phase, Eds.: Jackowski K.& Jaszuński M., RSC., London, § 1, 2016, pp.1-51. [CrossRef]

- Bajac D.F.E., Aucar I.A., Aucar G.A., Absolute NMR shielding scales in methyl halides obtained from experimental and calculated nuclear spin-rotation constants, Phys. Rev. A, 2021, 104, 012805. [CrossRef]

- Aucar G.A., Aucar I.A., Recent Developments in Absolute Shielding Scales for NMR Spectroscopy, Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc., 96 (2019) pp. 77-141. [CrossRef]

- Stone N.J., Table of Recommended Nuclear Magnetic Dipole Moments: Part 1, Long-Lived States, INDC International Nuclear Data Committee, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 100, 1400 Vienna, Austria. https://nds.iaea.org/publications/indc/indc-nds-0794.pdf.

- Schneider G., Mooser A., Bohman M., Schön N., Harrington J., Higuchi T., Nagahama H., Sellner S., Smorra C., Blaum K., Matsuda Y., Quint W., Walz J., Ulmer S., Double-trap measurement of the proton magnetic moment at 0.3 parts per billion precision. Science, 2017, 358 (6366), 1081-1084. [CrossRef]

- Puchalski M., Komasa J., Spyszkiewicz A., Pachucki K., Nuclear magnetic shielding in HD and HT, Phys. Rev.A, 2022, 105, 042802. [CrossRef]

- Schneider A., Sikora B., Dickopf S., Müller M., Oreshkina N.S., Rischka A., Valuev I.A., Ulmer S., Walz J., Harman Z., Keitel C.H., Mooser A., Blaum K., Direct measurement of the 3He+ magnetic moments, Nature, 2022, 606, 878–883. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Szyprowska A., Jackowski K., Precise determination of the 13C nuclear magnetic moment from 13C, 3He and 1H NMR measurements in the gas phase, Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 511, 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Wilczek M., Jackowski K., 17O and 1H NMR spectral parameters in isolated water molecules, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2018, 20, 22468. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Garbacz P., Gas-phase 21Ne NMR studies and the nuclear magnetic dipole moment of neon-21, Magn. Reson. Chem., 2020, 58, 648-652. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Jackowski K., Antušek A., Jaszuński M., Gas-phase NMR measurements, absolute shielding scales and magnetic dipole moments of 29Si and 73Ge nuclei, J. Phys. Chem.A., 2006, 110, 11462.

- Lantto P., Jackowski K., Makulski W., Olejniczak M., Jaszuński M., NMR shielding constants in PH3, absolute shielding scale and the nuclear magnetic moment of 31P , J. Phys. Chem.A, 2011, 115, 10617. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Probing nuclear dipole moments and magnetic shielding constants through 3-helium NMR spectroscopy, Physchem. (MDPI) 2(2) (2022) 116-130. [CrossRef]

- Traub W., Roesler F.L., Robertson M.M., Cohen V.W., Spectroscopic Measurement of the Nuclear Spin and Magnetic Moment of 39Ar, J. Opt. Soc. Am., 1967, 57(12), pp. 1452-1458. [CrossRef]

- Klein A., Brown B.A., Georg U., Keim M., Lievens P., Neugart R., Neuroth M., Silverans R.E., Vermeeren L., ISOLDE Collaboration, Moments and mean square charge radii of short-lived argon isotopes, Nucl. Phys.A, 1996, 602, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Explorations of Magnetic Properties of Noble Gases: the Past, Present and Future, Magnetochemistry, 2020, 6(4), 46. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., 83Kr nuclear magnetic moment in terms of that of 3He, Magn. Reson. Chem., 2014, 52, 430-434. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., 129Xe and 131Xe Nuclear Magnetic Dipole Moments from Gas Phase NMR Spectra, Magn. Reson. Chem., 2015, 53, 273-279. [CrossRef]

- Garbacz P., Makulski W., 183W nuclear dipole moment determined by gas-phase NMR spectroscopy, Chem. Phys., 2017, 498-499, 7-11.

- Makulski W., Tetramethyltin study by NMR Spectroscopy in the gas and liquid phase, J. Mol. Struct., 2012, 1017, 45. [CrossRef]

- Adrian B., Makulski W., Jackowski K., Demissie T.B., Ruud K., Antušek A., Jaszuński M., NMR shielding scale and the nuclear magnetic dipole moment of 207Pb, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2016, 18, 16483-90. [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., The Radiofrequency NMR Spectra of Lithium Salts in Water; Reevaluation of Nuclear Magnetic Moments for 6Li and 7Li, Magnetochemistry, 2018, 4, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pachucki K., Patkóš V., Yerokhin V.A., Accurate determination of 6,7Li nuclear magnetic moments, Phys. Lett.B, 2023, 846, 138189. [CrossRef]

- Neronov Yu.I. Determination of the magnetic moments of 6Li and 7Li nuclei using an NMR spectrometer that records signals from two nuclei simultaneously. Izmeritel`naya Tekhnika. 2020, 9, 3-8. (In Russ.) . [CrossRef]

- Makulski W., Multinuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Sodium Salts in Water Solutions, Magnetochemistry, 2019, 5, 68. [CrossRef]

- Yu. I. Neronov Yu. I., Determination of the Magnetic Moment of a 23Na Nucleus Using an NMR Spectrometer with Simultaneous Detection of Signals from Two Nuclei, Technical Physics, 2021, 66(1) 93-97. [CrossRef]

- Neronov Yu. I., Pronin A. N., Study of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of Potassium Ions in Aqueous Solutions and Estimation of the Magnetic Moment of the 39K Nucleus, Measurement Techniques, 2021, 64(6), 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Hurajt A., Antušek A., NMR shielding constants and rederivation of accurate magnetic dipole moments of 77Se, 123Te, and 125Te nuclei, J. Chem. Phys. 2025, 163, 144306. [CrossRef]

- Gryff-Keller A., Molchanov S., Wodyński A., Scalar relaxation of the second kind - a potential source of information on the dynamics of molecular movements. 2. Magnetic dipole moments and magnetic shielding of bromine nuclei. J Phys Chem.A., 2014, 118(1), 128-33. [CrossRef]

- Hurajt A., Kędziera D., Kaczmarek-Kędziera A., Antušek A., Nuclear magnetic dipole moments of 75As, 121Sb, and 123Sb from ab initio calculations of NMR shielding constants and existing NMR experiments, Phys. Rev.A, 2024, 109, 042815. [CrossRef]

- Neronov Yu. I., Pronin A.N., Study of NMR Signals of Rubidium in Aqueous Solutions and Determination of the Magnetic Moments of Rb-85 and Rb-87 Nuclei, Technical Physics, 2024, 68(S3), S478-S484. [CrossRef]

- Neronov, Yu. I., Pronin, A. N., NMR Spectra of Cesium in Aqueous Solutions. Determination of the Magnetic Moment of Cesium-133 Nucleus, Measurement Techniques, 2022, 64(11) 865-870. [CrossRef]

- Antušek A., Jaszuński M., Misiak M., Makulski W., Jackowski K., Nuclear magnetic dipole moment of 209Bi from NMR experiments, Phys. Rev. A., 2018, 98, 052509. [CrossRef]

- Skripnikov L.V., Schmidt S., Ullmann J., Geppert C., Kraus F., Kresse B., Nörtershäuser W., Privalov A.F., Scheibe B., Shabaev V.M., Vogel M., Volotka A.V., New Nuclear Magnetic Moment of 209Bi: Resolving the Bismuth Hyperfine Puzzle, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2018, 120(9), 093001. [CrossRef]

- Smorra C., Sellner S., Borchert M.J., Harrington J.A., Higuchi T., Nagahama H., Tanaka T., Mooser A., Schneider G., Bohman M., Blaum K., Matsuda Y., Ospelkaus C., Quint W., Walz J., Yamazaki Y., Ulmer S., A parts-per-billion measurement of the antiproton magnetic moment, Nature, 2017, 550, 371–374. [CrossRef]

- Arima A., A short history of nuclear magnetic moments and GT transitions, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron., 2011, 54, 188–193. [CrossRef]

- Wang T., Lattice Calculation of Nuclear Magnetic Dipole Moment. https://indico.ihep.ac.cn/event/24637/attachments/88211/113819/Dipole%20Moment.pdf.

- Zhao E., Recent progress in theoretical studies of nuclear magnetic moments, Chin. Sci. Bull., 2012, 57(34). [CrossRef]

- Li J., Meng J., Nuclear magnetic moments in covariant density functional theory, Front. Phys. 2018, 13, 132109. [CrossRef]

- Castel B., Towner I.S., Modern Theories of Nuclear Moments, (1990) Oxford, 1990; online edn, Oxford Academic, 31 Oct. 2023), accessed 18 Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T.J. Mertzimekis, An online database of nuclear electromagnetic moments, Phys. Res. A, 2016, 807, 56-60. [CrossRef]

- Stone N.J., Nuclear moments: recent developments, Interactions, 2024, 245, 50. [CrossRef]

| NMR spectra | NMM. transfer | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| 1H and 2H(D) | 1H → 2H(D) | HD |

| 1H and 3H(T) | 1H → 3H(T) | HT |

| 19F and 10B | 19F → 10B | BF3 |

| 19F and 3He | 3He → 10B | BF3/3He |

| 19F and 11B | 19F → 11B | BF3 |

| 19F and 3He | 3He → 11B | BF3/3He |

| 1H and 13C | 1H → 13C | 13CH4 |

| 3He and 13C | 1H → 13C | 13CH4/3He |

| 1H and 14N | 1H → 14N | NH3 |

| 3He and 14N | 3He → 14N | NH3/3He |

| 1H and 15N | 1H → 15N | NH3 |

| 3He and 15N | 3He → 15N | NH3/3He |

| 1H and 17O | 1H → 17O | H2O |

| 1H and 19F | 1H → 19F | CH3F |

| 1H and 29Si | 1H → 29Si | SiH4 |

| 1H and 31P | 1H → 31P | PH3 |

| 3He and 31P | 3He → 31P | PH3/3He |

| 3He and 33S | 3He → 33S | SF6/3He |

| 1H and 35/37Cl | 1H → 35/37Cl | HCl |

| 3He and 35/37Cl | 3He → 35/37Cl | HCl/3He |

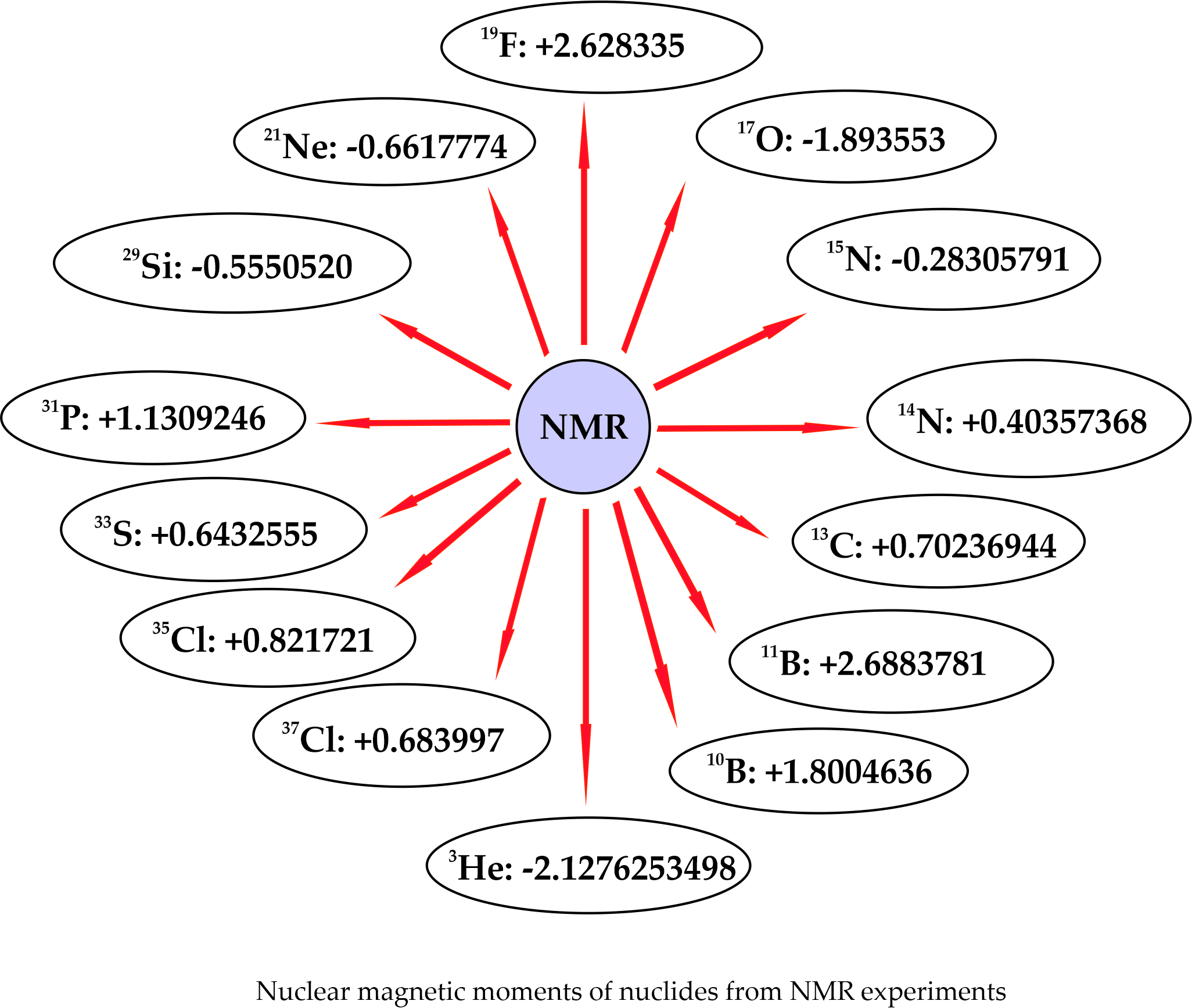

| Isotope | I(X) | µ(X)µN Ref.[14] | µ(X)µN | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 1/2+ | +2.792847351(9) | +2.79284734462(82) | Schneider et al./2017 [15] |

| 2H | 1+ | +0.857438231(5) | +0.8574382335(22) | Puchalski et al./2015 [16] |

| 3H | 1/2+ | +2.978962460(14) | +2.978962471(10) | Puchalski et al./2015 [16] |

| 3He | 1/2+ | -2.12762531(3) | -2.1276253498(15) | Schneider et al./2022 [17] |

| 10B | 3+ | +1.8004636(8) | +1.8004636(8) | Jackowski et al./2009 [7] |

| 11B | 3/2+ | +2.688378(1) | +2.6883781(11) | Jackowski et al./2009 [7] |

| 13C | 1/2- | +0.702369(4) | +0.70236944(68) | Makulski et al./2011 [18] |

| 14N | 1+ | +0.403573(2) | +0.40357368(7) | Makulski et al./2022 [6] |

| 15N | 1/2- | -0.2830569(14) | -0.28305791(3) | Makulski et al./2022 [6] |

| 17O | 5/2+ | -1.893543(10) | -1.893553(2) | Makulski et al./2018 [19] |

| 19F | 1/2+ | +2.628321(4) | +2.628335(11) | Jaszuński et al./2012 [1] |

| 21Ne | 3/2+ | -0.66170(3) | -0.6617774(10) | Makulski et al./2020 [20] |

| 29Si | 1/2+ | -0.555052(3) | -0.5550516(31) | Makulski et al./2006 [21] |

| 31P | 1/2+ | +1.130925(5) | +1.1309246(50) | Lantto et al./2011 [22] |

| 33S | 3/2+ | +0.64325(1) | +0.6432555(10) | Makulski/2022 [23] |

| 35Cl | 3/2+ | +0.82170(2) | +0.821721(5) | Jaszuński et al./2013 [8] |

| 37Cl | 3/2+ | +0.68400(1) | +0.683997(4) | Jaszuński et al./2013 [8] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).