1. Introduction

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is an umbrella diagnosis for symptomatic primary antibody deficiencies [

1,

2,

3]. Its clinical phenotype is complex and heterogeneous. CVID disorders are characterized by impaired B cell differentiation, resulting in defective immunoglobulin (Ig) production and a diminished or absent antibody response, which increases the risk of severe recurrent infections [

56,

57]. Progress in the understanding of the disease indicates that approximately 70% of cases are associated with one or more noninfectious complications, including autoimmunity, enteropathy, polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration (such as splenomegaly and granulomatous infiltration) and malignancy, all stemming from immune dysregulation [

2,

4]. Consequently, CVID involves defective B cell function, systemic immune activation with abnormal T cell function and dysregulation of other innate immune cells, as well as microbial translocation due to impaired gastrointestinal (GI) barrier function [

58]. These abnormal immune responses culminate with a milieu of persistent systemic inflammation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This updated modern scientific view recognizes CVID as a heterogeneous collection of immune dysregulation disorders rather than an infectious complication from low immunoglobulin count [

4]. Lifelong treatment with immunoglobulin replacement (IgRT) is essential for managing humoral inborn errors of immunity (IEI) to reduce the risk and severity of infectious complications. However, data on its benefits for noninfectious manifestations remain insufficient [

11]. Despite IgRT, patients with noninfectious complications face an 11-fold higher risk of mortality with lung disease being the leading cause of death, followed by lymphoma and liver disease [

12].

Lung disease complicates CVID in up to 90% of cases and includes bronchitis (70%), bronchiectasis (30–40%), obstructive ventilatory disease—such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (30–50%), granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD) (up to 20% of cases), and rarely, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) B-cell lymphoma [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Secondary amyloidosis is another possible complication in CVID patients [

18].

Amyloidosis is a rare condition wherein proteins are abnormally deposited into extracellular tissue, leading to disruption of existing structures and manifesting in a variety of clinical presentations depending on the organ involved [

19]. It can be classified based on quantity, type, and location of these proteins. The most common types of amyloidosis are AL (primary) localized or systemic, systemic amyloid A (AA) and systemic wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (wt)ATTR. While AL amyloidosis occurs with plasma cell dyscrasias, the AA type accompanies chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatic pathologies (familial Mediterranean fever, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis), chronic infections (tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, and osteomyelitis), and some malignancies that are observed in patients diagnosed with CVID [

52]. Current evidence is largely limited to case reports and small case series, and there is no comprehensive synthesis of the spectrum of amyloidosis subtypes, organ involvement, or patient outcomes. To date, no published cases describing the association of different types of amyloidosis in patients diagnosed with CVID have been identified in the literature. However, the coexistence of different types of amyloidosis in a single patient is a rare but possible occurrence [

20].

Given the heterogeneity and limited nature of the existing literature, a scoping review is appropriate to map the available evidence, identify knowledge gaps, and provide an overview of reported cases of amyloidosis occurring as a complication of CVID and also to identify the predominantly affected organs. The main questions were the following. Which types of amyloidosis occur in CVID patients, which organs are most frequently involved, are there cases of coexisting amyloidosis subtypes, and what gaps exist in the current literature? The objectives were to provide an overview of reported cases, identify rare clinically significant events, and highlight areas for future research.

Thus, knowing these data, we want to draw attention to the importance of careful evaluation of CVID patients in order to detect amyloidosis in its early stages in case of persistent symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

This review included case reports and case series published on the PubMed platform between 1996 to present. The keywords we used were airway [all fields] OR lung [all fields] OR pulmonary [all fields] OR respiratory [all fields] AND amyloidosis [all fields] AND CVID [all fields] and also amyloidosis [all fields] AND CVID [all fields]. In the first part of the review, we identified case reports and case series in which amyloidosis was diagnosed in patients with CVID. We included thirteen case reports and one retrospective study that reported patients diagnosed with CVID complicated by amyloidosis. Also, this paper reports a challenging case of CVID, initially complicated by features of AA amyloidosis, later confirmed as AL systemic amyloidosis. We aim to emphasize the importance of actively screening for amyloidosis as a potential complication in CVID patients with atypical symptoms and to discuss existing data on this rare co-occurrence. Considering the particularity of the index case presented, in the second part of the review we included four case reports and four case series focused on reports describing the coexistence of two types of amyloidosis in the same patient. These criteria were chosen to concentrate the analysis on the population of interest, in which the coexistence of multiple amyloidosis subtypes represents a rare but clinically significant phenomenon. Studies were eligible if they provided individual patient data (age, sex, organ involvement and the type of amyloidosis). Unavailable information was recorded as “Not available (N/A)” in the summary tables. This restriction allowed for a precise synthesis of clinically relevant cases and a clear comparison between different types of amyloidosis in this particular category of patients.

Given that most of the included studies were case reports and small observational studies, a formal critical appraisal using standard tools was not applicable. However, we considered potential sources of bias such as incomplete patient descriptions.

3. Results

Using the search strategy described earlier, we identified a total of seventeen cases of amyloidosis associated to CVID, with renal involvement (n = 11), GI involvement (n = 5), thyroid involvement (n = 1), salivary gland involvement (n = 1), and pulmonary involvement (n = 1). All cases were of the AA subtype (

Table 1). In some patients, multiple organ systems were affected simultaneously, reflecting the heterogeneity of clinical presentations. Long-term follow-up data were generally scarce, limiting conclusions about prognosis. Notably, no cases of systemic AL amyloidosis have been described in CVID patients without an associated plasma cell dyscrasia, highlighting the exceptional nature of our observation. These findings emphasize that although uncommon, amyloidosis is a serious complication in CVID with a predominant renal pattern and a potential for systemic progression.

No formal critical appraisal of the included sources of evidence was undertaken as the purpose of this scoping review was to provide an overview of the existing literature rather than assess the methodological quality of individual studies.

Also, We report the case of a 71-year-old male patient with CVID complicated by recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections, bronchiectasis, and infectious complications. He had been receiving IgRT for the past 10 years. The patient developed progressive exertional dyspnea over six months, along with decreased exercise tolerance and fatigue. However, he denied fever, chills, chest pain, hemoptysis, rash, joint pain, or muscle aches. In addition, the past medical history is consistent with cardiovascular disease (primary hypertension and ascending aorta ectasia), cerebral ischemic disease of small vessels, overweight, and impaired fasting glucose.

The patient is monitored through a multidisciplinary approach with follow-up by immunology, pulmonology, hematology, cardiology, diabetes and metabolic diseases, and neurology specialists. He has no history of smoking, no significant environmental or occupational exposures, and no family history of pulmonary, connective tissue, or hematological diseases.

Physical examination revealed a patient in no acute distress, able to speak without shortness of breath. All vital signs—including temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate—were within normal ranges, with a pulse oximetry reading of 94% in ambiental air. The patient was overweight with a body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, which has remained stable since his CVID diagnosis. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal and respiratory assessment unremarkable with no crackles suggestive of interstitial lung disease. There was no peripheral edema, palpable lymphadenopathy, digital clubbing, or other signs of connective tissue disease.

The initial laboratory work-up is outlined below. Complete blood count, C-reactive protein, liver and renal function tests, coagulation studies, serum sodium and potassium levels, total serum protein, albumin, serum iron, ferritin, vitamin B12, and biomarkers for myocardial ischemia (N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitivity troponin (hsTroponin)), as well as D-dimers, are all within normal ranges. Viral serology (HIV, hepatitis B and C tests) and autoimmune tests (anti-dsDNA antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, cytoplasmic-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) and perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA)) were negative, as were tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohidrat antigen 19-9) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). IgA and IgM serum levels were undetectable while the IgG level was 827 mg/dL (normal range, 700–1600 mg/dL).

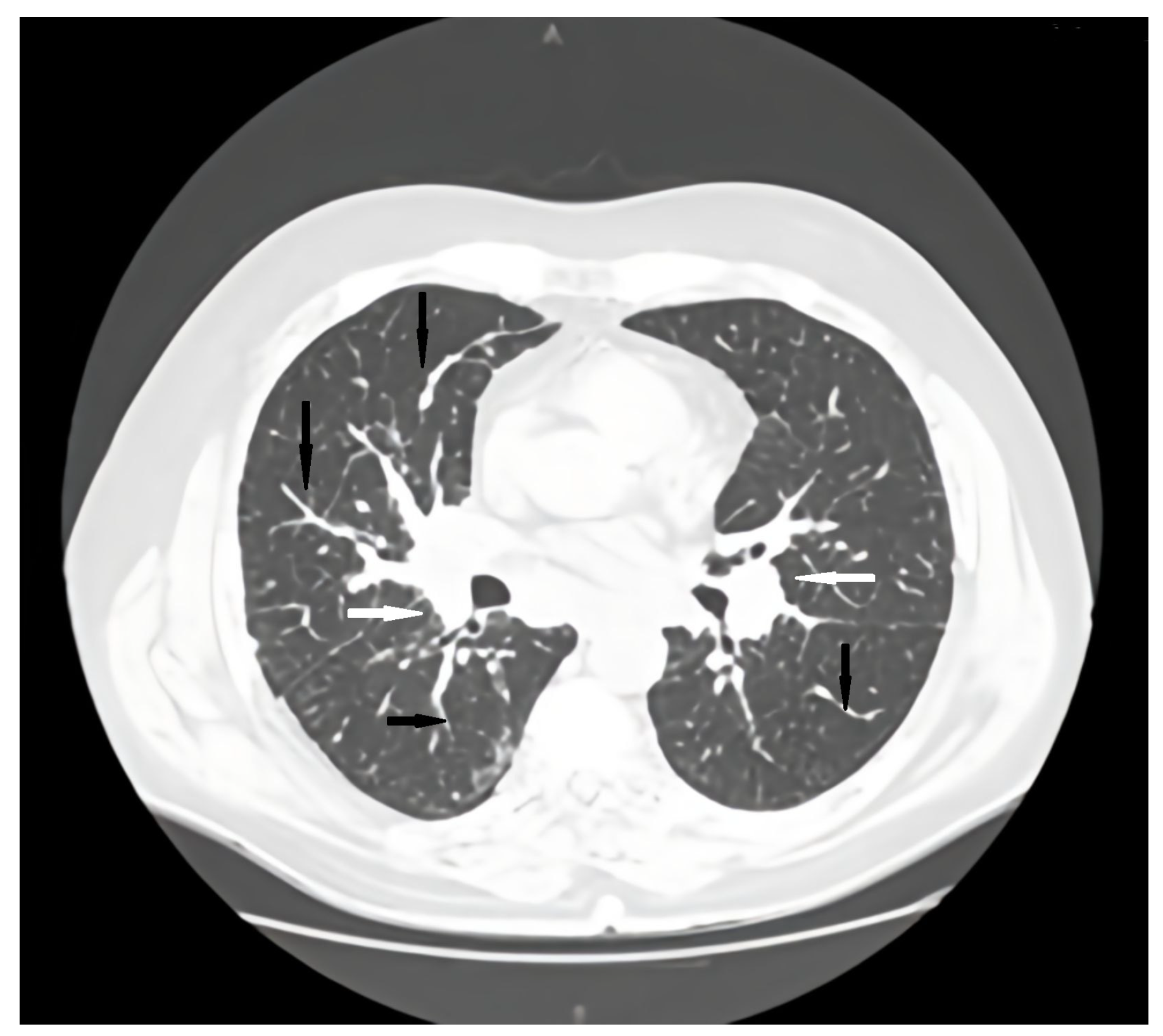

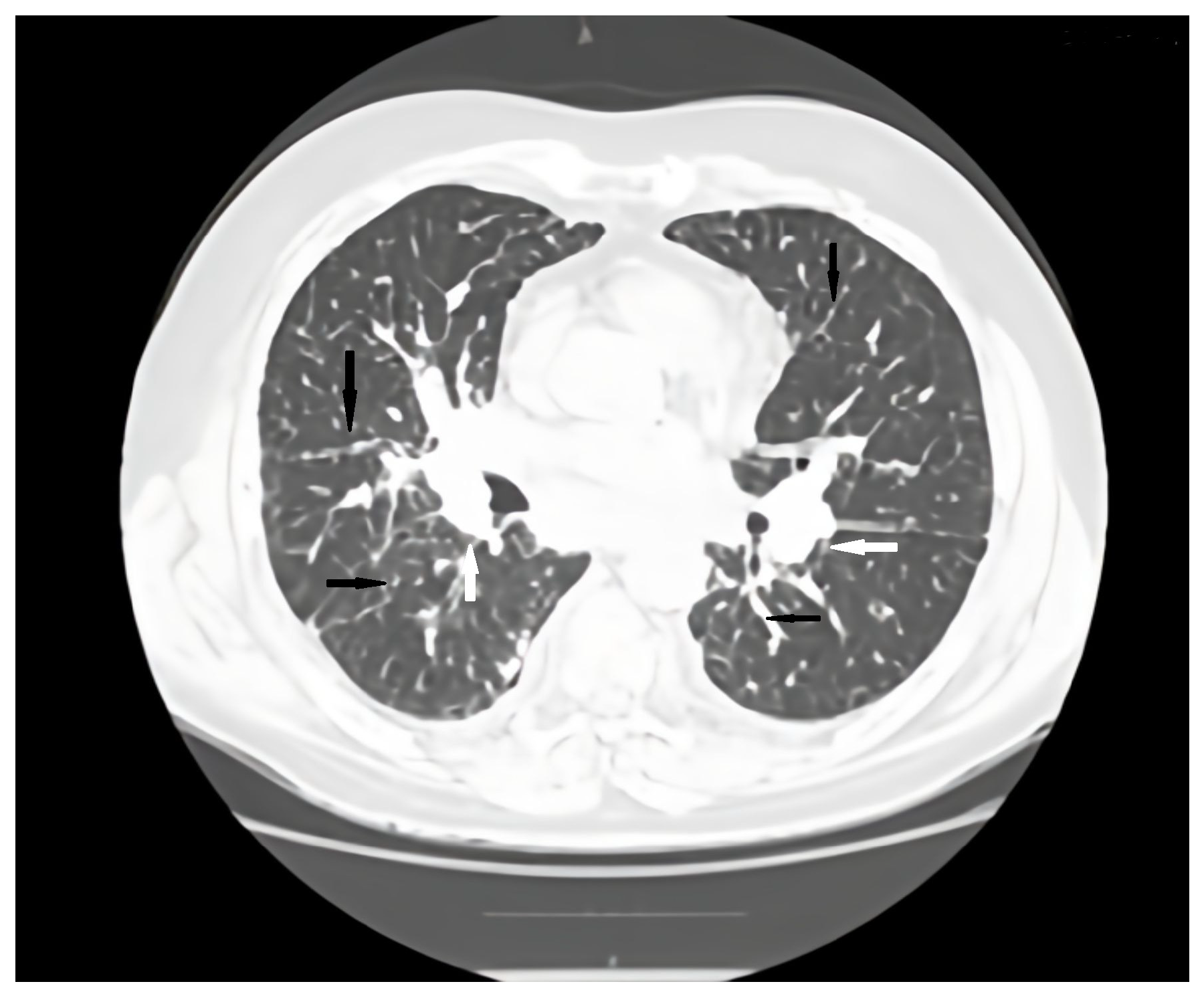

Regular pulmonology follow-up and periodic lung computed tomography (CT) scans showed a stable pattern over the years following the CVID diagnosis, characterized by a bilateral centrilobular micronodular pattern, irregular peribronchovascular thickening, bronchiectasis with mucoid impactations in the lower lobes, alveolar infiltrates, and mediastino-hilar adenopathies. After the onset of respiratory symptoms, a follow-up lung CT revealed similar interstitial findings suggestive of interstitial lung disease along with stable mediastinal-hilar adenopathies (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

At this point, the CT scan was suggestive for an interstitial lung disease (ILD), but its etiology was still unknown. Several differential diagnoses have been considered including GLILD and sarcoidosis. GLILD has been defined as a distinct clinico-radio-pathological ILD occurring in patients with CVID, associated with a lymphocytic infiltrate or granuloma in the lung. Also, carcinomatous lymphangitis was considered in the context of a suspicious gastric lesion.

Pulmonary function tests indicated a mixed pattern with mild restriction (forced vital capacity (FVC) = 61%, 2.36 L) and moderate central obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second FEV1 = 50%, 1.69 L). Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) remained normal at 84% and lung volumes were preserved with alveolar volume (AV) at 80% of the predicted value.

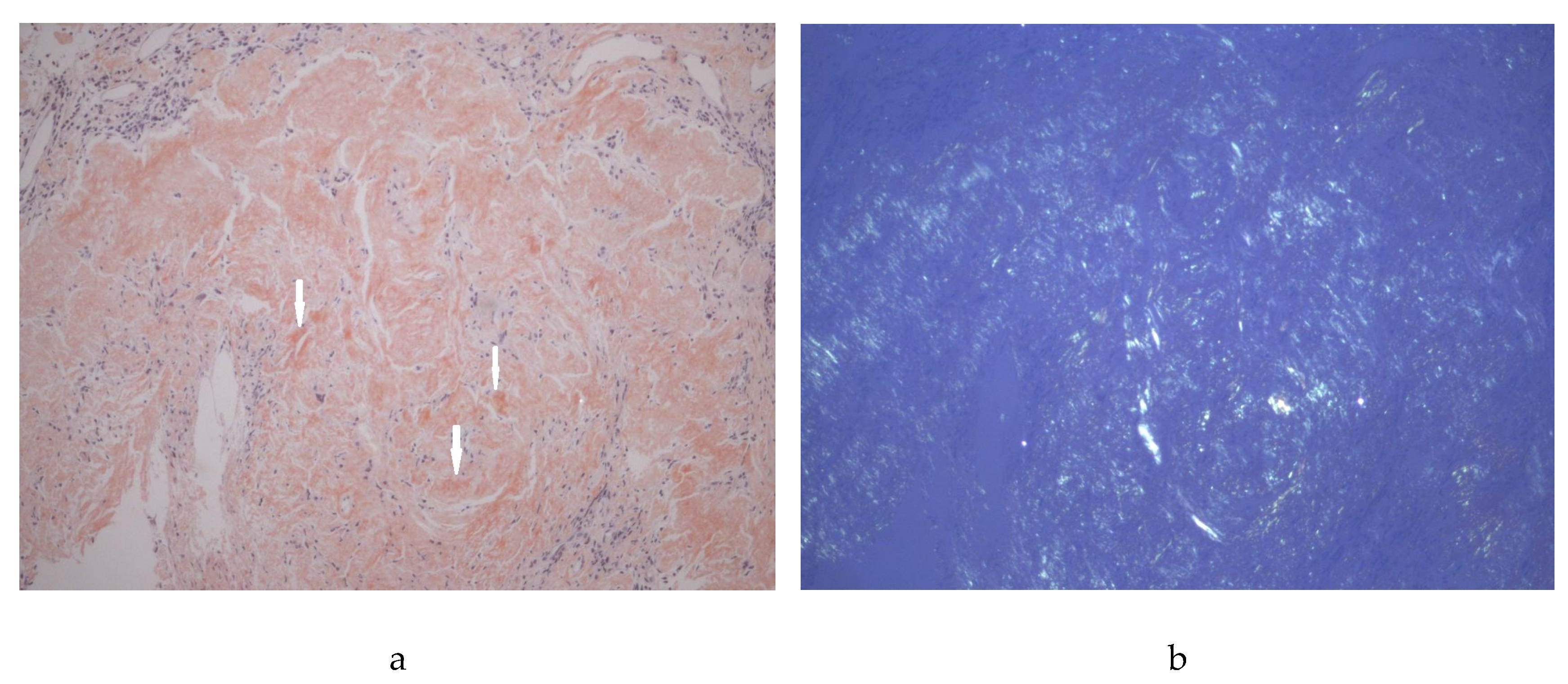

In order to establish the diagnosis, bronchoscopy was performed. The macroscopic findings such as hyperemic mucosa and mucous secretions were consistent with chronic bronchitis. Additionally, two slightly elevated, translucent, congested lesions measuring 2–3 mm in diameter were observed on the medial and lateral walls of the intermediate bronchus and subsequently biopsied. Histopathological analysis revealed amyloid depositions with Congo red – positive staining in a nodular pattern within the subepithelial stroma and vessel walls confirming nodular pulmonary amyloidosis, but immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical staining for AA protein and for kappa and lambda light chains were not performed. Bronchial aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) showed no lymphocytosis nor cytological evidence of malignancy. Cultures did not reveal any pathogens including common germs Aspergillus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Upper digestive endoscopy revealed diffusely infiltrated gastric mucosa with nodular, serpiginous, and confluent ulcers. Biopsies from both the duodenum and gastric corpus confirmed amyloid depositions with Congo red – positive staining, thus ruling out the suspicion of malignancy (

Figure 3). The patient declined a colonoscopy. At this stage, he remained asymptomatic for digestive issues.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) for a primary immunodeficiency panel of 575 genes was performed with support from the Jeffrey Modell Foundation (JMF). The results confirmed carrier status for thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome and identified several variants of uncertain significance (Appendix A.1).

Serum electrophoresis with immunofixation revealed absent monoclonal bands for IgG, IgA, and IgM, as well as absent monoclonal kappa and lambda light chains. Immunophenotyping of lymphocytes showed decreased B cell counts with a value of 20 cells/µL (normal range, 78–899 cells/µL) while the total lymphocyte count and CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts were within normal limits. Serum amyloid A protein was slightly elevated at 16 mg/L (normal value, <10 mg/L). Genetic testing was negative for the hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis pathogenic mutation on the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) platform (105210).

Taking into consideration the association between clinical manifestations, history of CVID, the CT and histopathological findings, and the complementary tests performed, the diagnosis at that point was thought to be secondary amyloidosis (AA) with pulmonary and gastric involvement. The triggering factor of secondary amyloidosis in a patient with CIVD was considered to be the history of recurrent respiratory infections. In addition to regular IgRT (600 mg/body weight/month), pulmonologists initiated immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone (40 mg/day) and prophylactic antibiotherapy with azithromycin on alternate days, three times per week, leading to immediate improvement in respiratory symptoms.

At three-month follow-up, in addition to worsening severe dyspnea, now present even during speech, the patient reported early satiety and unintentional weight loss. Subsequently, he developed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate, prompting the initiation of treatment with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors (ACEIs), digoxin, and anticoagulants. Pulmonary hypertension (PHT) was deemed unlikely based on cardiac echocardiographic studies. CT scan of the lungs and abdomen revealed a stable appearance of the lungs, adenopathies, and gastric wall.

At this moment, moderate normochromic normocytic anemia, an inflammatory syndrome (C-reactive protein value of 4.9 mg/dL), mild hypoproteinemia (6.28 g/dL, normal range, 6.6–8.3 g/dL), and hypoalbuminemia are documented. A 24 h urine protein test confirms renal protein loss with a value of 193.5 mg/24 h (normal range, <150 mg/24 h). Fecal calprotectin was elevated (354 μg/g, normal range, <50), indicating intestinal inflammation. Liver function tests showed mild hepatic cytolysis and cholestasis. Serum IgG levels were low, ranging from 400–600 mg/dL, despite a high-dose of IgRT (600 mg/body weight), in the context of renal protein loss and possibly liver and digestive disease. Since the onset of dyspnea, there have been no infectious episodes.

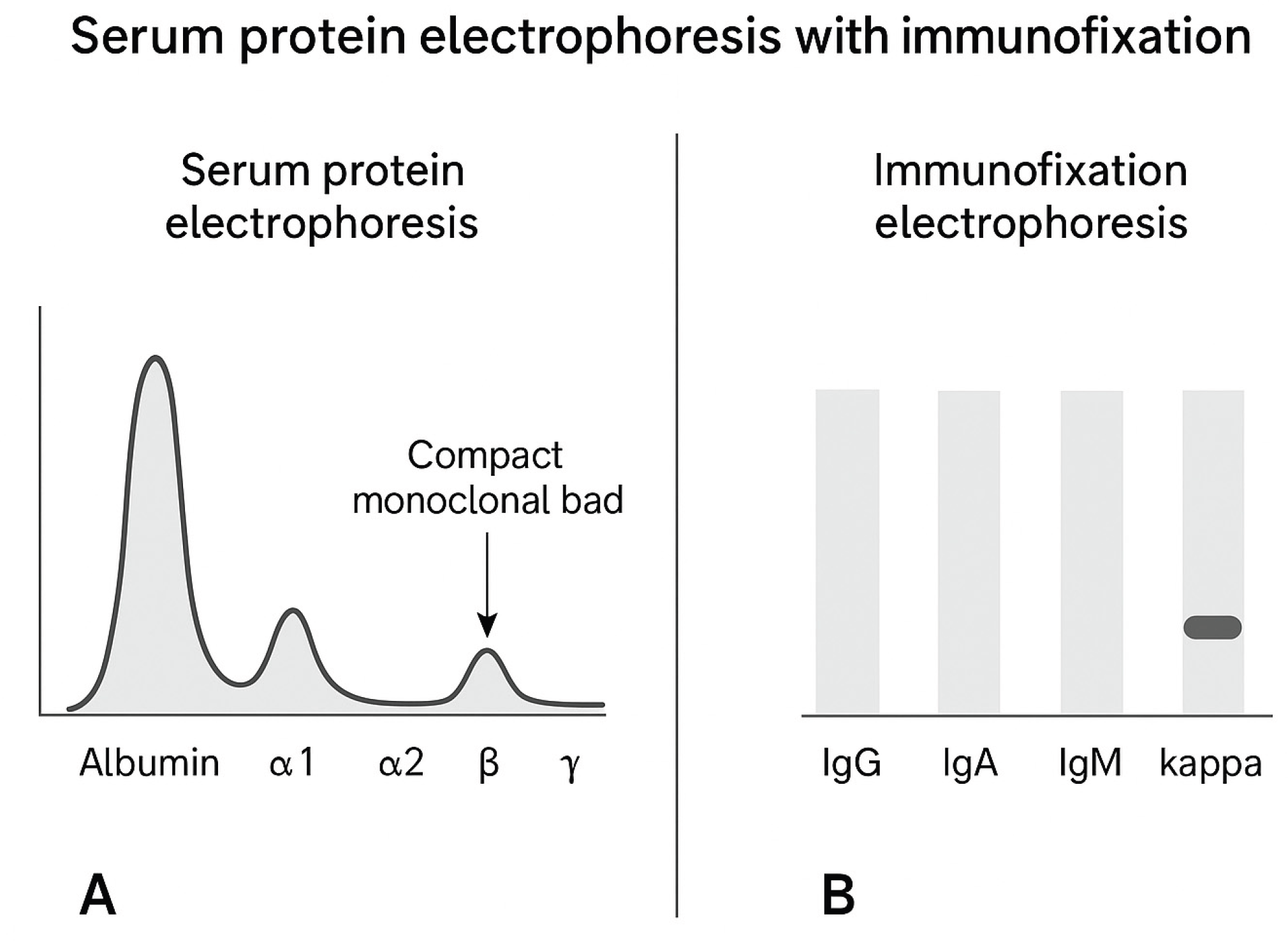

The patient was reevaluated in the haematology department where other suggestive signs of multiple organ involvement were identified including cardiac (orthostatic hypotension), neurological (peripheral neuropathy), soft tissue (tongue enlargement) and salivary gland involvement (sicca syndrome), all of them being characteristic symptoms for systemic AL amyloidosis. An extended workup was performed including serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation where a compact band in the Ig area for kappa light chain was detected (

Figure 4). Serum immunofixation showed an elevated free kappa light chain (1057.44 mg/dL) and a normal free lambda light chain (5.5 mg/dl), kappa:lambda ratio, 196.2.

Bone marrow biopsy done to rule out multiple myeloma or other lymphoproliferative disorders showed no signs of plasma cell dyscrasia. Multiorgan involvement, deranged serum kappa:lambda ratio and elevated serum kappa levels rendered AL amyloidosis with pulmonary and GI involvement as an obvious diagnosis.

Treatment with Daratumumab and Cyclophosphamide was initiated. The use of Bortezomib was considered but postponed at this time.

One year after the diagnosis of pulmonary amyloidosis and 4 months after the initiation of chemotherapy, the patient was urgently hospitalized for sepsis and acute respiratory failure and died three days later due to multiple organ failure caused by Candida albicans fungemia.

Table 2.

Summary of case patient features.

Table 2.

Summary of case patient features.

| Category |

Features of the Present Case |

| Patient demographics |

71-year-old male |

| Underlying condition |

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) |

| Initial presentation |

Dyspnea on exertion, oxygen desaturation, decreased exercise tolerance and fatigue |

| Laboratory findings |

Complete blood count, C-reactive protein, liver and renal function tests, coagulation studies, serum sodium and potassium levels, total serum protein, albumin, serum iron, ferritin, vitamin B12, and biomarkers for myocardial ischemia (N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitivity troponin (hsTroponin)), as well as D-dimers, are all within normal ranges

Viral serology (human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C tests) and autoimmune tests (anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, cytoplasmic-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA), perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA)) are negative

tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohidrat antigen (CA 19-9) – negative

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) – negative

IgA and IgM serum levels are undetectable, while the IgG level is 827 mg/dL (normal range, 700–1600 mg/dL) |

| Chest computed tomography (CT) scan |

bilateral centrilobular micronodular pattern, irregular peribronchovascular thickening, bronchiectasis with mucoid impactations in the lower lobes, alveolar infiltrates and mediastino-hilar adenopathies |

| Pulmonary function tests |

Forced vital capacity (FVC) = 61%, 2.36 L, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) = 50%, 1.69 L,

alveolar volume (AV) = 80%

|

| Histopathology |

Pulmonary biopsy: amyloid deposits with apple-green birefringence on Congo red staining

Duodenum and gastric corpus biopsy: amyloid depositions with Congo red-positive staining |

| Initial interpretation |

Secondary (AA) amyloidosis complicating CVID |

| Disease evolution |

After 6 months: clinical and laboratory features of systemic AL amyloidosis; Serum immunofixation: elevated kappa light chains |

| Final diagnosis |

Coexistence of AA amyloidosis and systemic AL amyloidosis as a complication of CVID |

| Treatment/Management |

Supportive management; hematologic evaluation; therapy directed according to amyloidosis subtype |

| Prognosis |

Poor prognosis due to systemic involvement and coexistence of two amyloidosis subtypes |

Even if most cases describe the association of secondary AA amyloidosis in CVID, taking into consideration the overlap of clinical presentation, there is the potential for two different types of amyloidosis to coexist in the same patient, a phenomenon rarely reported in the literature.

After reviewing the literature, we identified four case reports and four case series describing the co-existence of two types of amyloidosis (

Table 3). Twenty-two cases were reported with ages ranging from 31 to 90 years and a predominance of male patients. The underlying conditions were variable, including monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), chronic kidney disease, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, smoldering myeloma, and heart failure, although several patients had no reported comorbidities. The most frequently observed combinations involved AL amyloidosis coexisting with ATTR (wild-type or hereditary) or SAA amyloidosis. Cardiac involvement was common, either as part of systemic amyloidosis or in combination with other organ involvement such as the kidneys, liver, duodenum, or bone marrow.

The temporal relationship between the diagnoses of the two amyloidosis subtypes varied widely, ranging from simultaneous detection to intervals of several years (up to 21 years), suggesting both synchronous and metachronous presentations. These cases highlight the heterogeneity in clinical presentation, organ involvement, and underlying conditions among patients with coexisting amyloidosis, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive evaluation and long-term monitoring

Overall, the results emphasize that the current evidence is largely based on case reports and small case series, with limited systematic data. This highlights the need for larger cohort studies to better characterize the prevalence, risk factors, and long-term outcomes of amyloidosis in CVID.

4. Discussion

CVID is an umbrella term for symptomatic primary antibody deficiencies, affecting approximately 1 in 25,000 individuals, with a higher prevalence in northern Europe [

1]. It does not show a predilection for race or gender. Most cases of CVID manifest during adulthood, with peak prevalence occurring between the second and fourth decades of life [

1,

2,

3].

In our patient, the diagnosis of CVID was based on severe hypogammaglobulinemia, with low serum levels of IgG (427 mg/dl – cut-off value for age 670 mg/dl), IgM (14.12 mg/dl), and IgA (21.20 mg/dl), along with recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections (3–4 cases of pneumonia per year). These infections had begun approximately six years before the diagnosis of CVID and were initially managed by the family physician and other specialists. However, a detailed clinical history revealed that the patient had experienced recurrent respiratory tract infections since childhood. The diagnosis of CVID, while obvious to a clinician trained in primary immunodeficiencies, was made late, at the age of 62, representing a significant delay of over 20 years, assuming the disease began in adulthood. Serum immunoglobulin levels were first tested by the immunology department when the patient was 62 years old. By the time of diagnosis, the patient had already developed bronchiectasis, which further complicated the treatment approach and negatively impacted the patient’s quality of life. As a result, there was a significant delay in initiating the correct treatment with IgRT. It is well known that delays in diagnosis and IgRT for patients with CVID significantly increase morbidity and mortality [

41]. Bronchiectasis is one of the most common complications seen in IEI patients [

41]. In such cases, the goal of treatment is to normalize serum IgG levels and reduce infectious complications [

40]. In addition, prophylactic and therapeutic antibiotics and complementary vaccinations with inactive antigens are recommended in these patients as well as in patients with protein loss diseases and pregnant patients [

42].

Although IgG serum levels were initially within normal ranges, in later months, the IgG trough level has not been controlled despite increasing doses of immunoglobulin replacement due to protein loss secondary to systemic amyloidosis with renal, digestive, and most likely liver involvement.

In the presented case, the coexistence of two amyloidosis subtypes could not initially be excluded as additional immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical analyses for AA protein and kappa and lambda light chains were not performed. However, the patient’s clinical course suggested this possibility. Following the detection of amyloid deposits in pulmonary biopsies, further investigations were undertaken to characterize the amyloidosis subtype. Currently, there is no standardized approach regarding the timing or methodology for evaluating amyloidosis in CVID patients, particularly with respect to pulmonary involvement.

Based on the investigations performed—including serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation which revealed no monoclonal IgG, IgA, or IgM bands, and absent monoclonal kappa and lambda light chains, elevated serum amyloid A, and the absence of gene mutations associated with ATTR amyloidosis—the findings were interpreted in the context of secondary (AA) amyloidosis as a complication of CVID. According to contemporary amyloidosis guidelines, primary immunodeficiency is recognized among the potential causes of AA amyloidosis, alongside inflammatory rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis), chronic inflammatory bowel disease, monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes (including familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic (VEXAS), and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS)), tuberculosis, hematologic disorders, Castleman disease, and obesity, the latter being considered a diagnosis of exclusion [

48].

Over a six-month period the patient developed additional clinical and laboratory features suggestive of systemic AL amyloidosis (cardiac signs, peripheral neuropathy, tongue enlargement, sicca syndrome). Repeat hematologic evaluation identified a compact band in the Ig area for kappa light chain on serum immunofixation. Quantitative testing showed marked elevation of free kappa light chains with a severely deranged kappa:lambda ratio, while bone marrow biopsy did not reveal a plasma cell dyscrasia. Taken together, these results supported the diagnosis of systemic AL amyloidosis evolving in a patient initially considered to have AA amyloidosis, consistent with coexistence of AA and AL amyloid in the same patient.

Based on the clinical course and investigations performed in this case, it was not possible to definitively exclude the coexistence of two amyloid subtypes at the time of the initial diagnostic workup because targeted immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence (AA, kappa, lambda) on tissue was not performed initially. The subsequent hematologic findings, however, along with multiorgan involvement, led to reinterpretation and classification as coexistence of AA amyloidosis and systemic AL amyloidosis complicating CVID.

Beyond this individual case, the broader context of CVID and its complications provides key insights into disease heterogeneity, mechanisms of immune dysregulation, and the pathophysiology of amyloidosis in primary immunodeficiencies.

According to the current scientific view, CVID is a heterogeneous collection of disorders characterized by immune dysregulation rather than an infectious complication of low immunoglobulin counts [

4]. The two primary features of the disease are impaired B cell differentiation with defective immunoglobulin production and a reduced or absent antibody response, along with immune dysregulation of both innate and adaptive cells. These factors are likely interconnected through abnormal microbiota and microbial translocation due to impaired GI barrier function. Together, these features contribute to a milieu of persistent systemic inflammation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. It is now accepted that not only B cells are affected but also certain T cell subsets, dendritic cells, monocytes, innate immune lymphoid cells, and natural killer T cells (NKT cells) [

11]. Several defects in innate and adaptive immune responses have been shown to play a role in the development of this wide range of infectious and noninfectious complications, although the exact molecular defects leading to disease remain a topic of study and interpretation [

11].

CVID disorders present a unique challenge, as they fall under an umbrella diagnosis currently governed by non-universal diagnostic criteria as presented in

Table 4. Also differential diagnosis of hypogammaglobulinemia are listed below in

Table 5.

In recent years, several monogenic disorders leading to the CVID phenotype have been identified in less than 20% of patients in nonconsanguineous cohorts and in approximately 70% of patients in consanguineous cohorts [

42]. State of the art diagnosis of IEI involves genetic testing of patients, with next generation sequencing being the gold standard. [

43]

Secondary amyloidosis, resulting from ongoing inflammation due to recurrent infections and autoimmunity, is an expected clinical presentation in patients with CVID. There are few cases in the literature describing the coexistence of two forms of amyloidosis [

36,

37,

38,

49,

50,

51,

52], but no case reported this association in patients with CVID. The low prevalence can be attributed to several factors, starting with the non-specific clinical signs, which can easily be mistaken for other conditions. Additionally, some CVID patients may be at higher risk of developing amyloidosis due to chronic and recurrent infections, often resulting from a delayed CVID diagnosis or patient negligence.

Considering that ATTR amyloidosis was excluded following genetic testing, the discussion focused on the two remaining possible forms, AL and AA.

AL (primary) amyloidosis showed a male predominance with a median age at diagnosis of 64 years and a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:2 [

44]. The estimated incidence in Western Europe and the United States is 6–10 cases per 100,000 individuals annually [

45], although precise figures remain unknown. Early mortality remains high, reflecting persistent diagnostic delays, with nearly 20% of patients dying within six months of diagnosis—a statistic that has not improved over the past four decades despite advances in therapy [

45,

49].

Secondary amyloidosis (AA) in CVID typically arises from chronic inflammation due to recurrent infections or autoimmune processes. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the organs involved with up to 70% of patients presenting with multi-organ involvement at diagnosis [

66]. The heart (71%), kidneys (58%), and nervous system (23%) are the most frequently affected organs, followed by the liver (16%) and, less commonly, the GI tract, joints, thyroid, gums, and lungs [

45,

46].

Pulmonary amyloidosis, although rare, is most often associated with AL rather than AA amyloidosis and can occur as a localized or systemic form [

59]. Autopsy studies indicate that pulmonary involvement is present in 88% of systemic amyloidosis cases with a poor median survival of 16 months [

46].

Three main patterns of pulmonary amyloidosis have been described, tracheobronchial, nodular parenchymal, and diffuse parenchymal, with the latter being the least common (approximately 3% of pulmonary amyloidosis cases) and often associated with multiple myeloma and poor prognosis [

19]. Diffuse alveolar-septal amyloidosis is characterized by amyloid deposits in alveolar septa and vessel walls and is usually linked to systemic AL amyloidosis, though cases caused by systemic AA or hereditary ATTR amyloidosis have also been reported [

19].

Bronchoscopy with biopsy (transbronchial lung biopsy or cryobiopsy) is considered one of the diagnostic gold standards for certain diffuse alveolar-septal or tracheobronchial disease forms, especially when imaging and non-invasive tests are inconclusive [

53]. Histopathology typically reveals amorphous eosinophilic amyloid deposits in alveolar septa, especially around capillaries, demonstrating apple-green birefringence with Congo Red staining under polarized light [

19].

The differential diagnosis of pulmonary amyloidosis includes metastatic disease, congestive heart failure, miliary tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, silicosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and other interstitial lung diseases [

60]. In CVID, GLILD represents a distinct entity characterized by lymphocytic infiltration or granuloma formation in the lungs [

19].

Accurate typing of the amyloid protein is critical for guiding treatment. Clinical presentations range from incidental asymptomatic findings on biopsy to severe multi-organ dysfunction [

20]. AL amyloidosis predominantly affects the kidneys, heart, and liver, whereas AA commonly involves the kidneys, liver, and intestines [

50].

Therapeutic strategies differ according to the amyloid subtype. Systemic AL amyloidosis is primarily managed with chemotherapy targeting plasma cell clones — with the goal of eradicating the pathogenic clone [

54] while AA amyloidosis treatment focuses on controlling the underlying inflammatory process to reduce SAA levels [

55]. Diagnosis of AA amyloidosis requires tissue confirmation via biopsy—abdominal fat aspirate is preferred, though biopsy of a clinically affected organ is acceptable [

61]. Immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical staining is then performed to differentiate AA from AL amyloidosis with monospecific anti-AA protein antibodies confirming AA amyloidosis and the absence of kappa or lambda light chain staining supporting AL amyloidosis [

62].

The findings of this scoping review demonstrate that the current evidence on amyloidosis in CVID is predominantly derived from case reports and small case series, with no large prospective studies available. Within the literature, AA amyloidosis was the most frequently reported subtype among CVID patients, whereas AL amyloidosis was more commonly observed in cases where two types of amyloidosis coexisted. Renal involvement emerged as the most consistent clinical manifestation in CVID patients while cardiac amyloidosis was the predominant feature in cases of coexisting amyloid subtypes.

These results directly address the review objectives by delineating the spectrum of amyloidosis types and organ involvement in CVID while also highlighting critical gaps in the existing evidence. For clinicians, the findings emphasize the importance of vigilant monitoring for amyloidosis in CVID patients. For researchers, they underscore the need for systematic studies and larger cohorts to better characterize the epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of amyloidosis in this population.

This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the number of published cases of amyloidosis in patients with CVID is very limited and most of the available evidence derives from isolated case reports or small case series. This makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions and increases the risk of publication bias as unusual or severe cases are more likely to be reported. Finally, long-term follow-up data are scarce across reported cases.

From a methodological perspective, the search strategy was limited to the PubMed database and studies indexed in other databases such as Embase [

63], Scopus [

64], or Web of Science [

65] may have been missed. Moreover, a formal review protocol was not registered which may reduce the transparency and reproducibility of the process.

These limitations highlight the need for more systematic reporting of amyloidosis in CVID and for multicenter studies that use standardized diagnostic and reporting approaches. Despite these limitations, the synthesis emphasizes the need for heightened clinical vigilance for amyloidosis in CVID patients presenting with atypical organ dysfunction, for routine consideration of amyloid typing (including immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence on tissue and appropriate hematologic evaluation), and for multicenter systematic studies to better define epidemiology and optimal diagnostic-therapeutic pathways.

5. Conclusions

IEIs remain largely undiagnosed and any delays in treatment greatly increase the risk of complications. Amyloidosis of the lower respiratory tract is rare and often undiagnosed, yet it can present a significant clinical challenge in both systemic and organ-limited amyloidosis. Although the number of reported cases is low, amyloidosis is a critical complication and may be more common in patients with CVID than previously recognized.

The results are relevant to clinicians who should remain vigilant for amyloidosis in CVID, to researchers who need to generate higher-level evidence, and to patient communities concerned with improving care and awareness for rare disease complications.

Determining the type of amyloidosis is necessary because even if secondary amyloidosis is the most frequent form associated with CVID, primary AL amyloidosis should still be considered. Identifying the nature and source of the amyloidogenic protein is critical given therapy varies significantly for the different types of amyloidosis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the post-mortem nature of this report.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

AA – Secondary amyloidosis

ACE – Angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACEIs – ACE inhibitors

AV – Alveolar volume

BALF – Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

BMI – Body mass index

CAPS – Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes

CHF – Chronic heart failure

CKD – Chronic kidney disease

CMV – Cytomegalovirus

COPD – Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CRP – C-reactive protein

CT – Computed tomography

CVID – Common variable immunodeficiency

c-ANCA – Cytoplasmic-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

DLCO – Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

ds-DNA – Double-stranded DNA

EBV – Epstein-Barr virus

ESID – European Society of Immune Deficiencies

FEV1 – Forced expiratory volume in 1 second

FMF – Familial Mediterranean fever

FVC – Forced vital capacity

GI – Gastrointestinal

GLILD – Granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease

HIV – Human immunodeficiency virus

hs-Troponin – High-sensitivity troponin

ICON – International consensus document

ID – Interstitial lung disease

IEI – Inborn errors of immunity

IFE – Immunofixation electrophoresis

IgRT – Treatment with immunoglobulin replacement

ILD – Interstitial lung disease

JMF – Jeffrey Modell foundation

MALT – Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

MGUS – Monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance

MM – Multiple myeloma

N/A – Not available

NKT cells – Natural killer T cells

NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

NYHA – New York Heart Association

OMIM – Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

p-ANCA – Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

PHT – Pulmonary hypertension

SAA – Serum amyloid A

SPEP – Serum protein electrophoresis

TRAPS – Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome

VEXAS – Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic

WES – Whole-exome sequencing

wtATTR – Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis

XLA – X-linked agammaglobulinemia

References

- Chapel, H; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Update in understanding common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVIDs) and the management of patients with these conditions. Br J Haematol 2009, 145(6), 709–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bonilla, FA; Barlan, I; Chapel, H; Costa-Carvalho, BT; Cunningham-Rundles, C; de la Morena, MT; Espinosa-Rosales, FJ; Hammarström, L; Nonoyama, S; Quinti, I; Routes, JM; Tang, ML; Warnatz, K. International Consensus Document (ICON): Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016, 4(1), 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oksenhendler, E; Gérard, L; Fieschi, C; Malphettes, M; Mouillot, G; Jaussaud, R; Viallard, JF; Gardembas, M; Galicier, L; Schleinitz, N; Suarez, F; Soulas-Sprauel, P; Hachulla, E; Jaccard, A; Gardeur, A; Théodorou, I; Rabian, C; Debré, P. DEFI Study Group. Infections in 252 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46(10), 1547–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, SL; Jang, HS; Li, J. The Immune Dysregulation of Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. Immunol Lett.;Epub 2021, 230, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ramón, S; Radigan, L; Yu, JE; Bard, S; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Memory B cells in common variable immunodeficiency: clinical associations and sex differences. Clin Immunol 2008, 128(3), 314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arumugakani, G; Wood, PM; Carter, CR. Frequency of Treg cells is reduced in CVID patients with autoimmunity and splenomegaly and is associated with expanded CD21lo B lymphocytes. J Clin Immunol 2010, 30(2), 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhmanov, M; Keller, B; Gutenberger, S; Foerster, C; Hoenig, M; Driessen, G; van der Burg, M; van Dongen, JJ; Wiech, E; Visentini, M; Quinti, I; Prasse, A; Voelxen, N; Salzer, U; Goldacker, S; Fisch, P; Eibel, H; Schwarz, K; Peter, HH; Warnatz, K. Circulating CD21low B cells in common variable immunodeficiency resemble tissue homing, innate-like B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106(32), 13451–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cols, M; Rahman, A; Maglione, PJ; Garcia-Carmona, Y; Simchoni, N; Ko, HM; Radigan, L; Cerutti, A; Blankenship, D; Pascual, V; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Expansion of inflammatory innate lymphoid cells in patients with common variable immune deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 137(4), 1206–1215.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jørgensen, SF; Trøseid, M; Kummen, M; Anmarkrud, JA; Michelsen, AE; Osnes, LT; Holm, K; Høivik, ML; Rashidi, A; Dahl, CP; Vesterhus, M; Halvorsen, B; Mollnes, TE; Berge, RK; Moum, B; Lundin, KE; Fevang, B; Ueland, T; Karlsen, TH; Aukrust, P; Hov, JR. Altered gut microbiota profile in common variable immunodeficiency associates with levels of lipopolysaccharide and markers of systemic immune activation. Mucosal Immunol 2016, 9(6), 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadlallah, J; Sterlin, D; Fieschi, C; Parizot, C; Dorgham, K; El Kafsi, H; Autaa, G; Ghillani-Dalbin, P; Juste, C; Lepage, P; Malphettes, M; Galicier, L; Boutboul, D; Clément, K; André, S; Marquet, F; Tresallet, C; Mathian, A; Miyara, M; Oksenhendler, E; Amoura, Z; Yssel, H; Larsen, M; Gorochov, G. Synergistic convergence of microbiota-specific systemic IgG and secretory IgA. J Allergy Clin Immunol Epub. 2019, 143(4), 1575–1585.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdani, R.; Habibi, S.; Sharifi, L.; Azizi, G.; Abolhassani, H.; Olbrich, P.; Aghamohammadi, A. Common Variable Immunodeficiency: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Classification, and Management. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer; Provot, J.; Jais, J.P.; Alcais, A.; Mahlaoui, N. members of the CEREDIH French PID study group, Autoimmune and inflammatory manifestations occur frequently in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 140(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham-Rundles, C. Common variable immune deficiency: Dissection of the variable. Immunol Rev 2019, 287(1), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galant-Swafford, J; Catanzaro, J; Achcar, RD; Cool, C; Koelsch, T; Bang, TJ; Lynch, DA; Alam, R; Katial, RK; Fernández Pérez, ER. Approach to diagnosing and managing granulomatous-lymphocytic interstitial lung disease. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riaz, IB; Faridi, W; Patnaik, MM; Abraham, RS. A Systematic Review on Predisposition to Lymphoid (B and T cell) Neoplasias in Patients With Primary Immunodeficiencies and Immune Dysregulatory Disorders (Inborn Errors of Immunity). Front Immunol 2019, 10, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wehr, C; Houet, L; Unger, S; Kindle, G; Goldacker, S; Grimbacher, B; Caballero Garcia de Oteyza, A; Marks, R; Pfeifer, D; Nieters, A; Proietti, M; Warnatz, K; Schmitt-Graeff, A. Altered Spectrum of Lymphoid Neoplasms in a Single-Center Cohort of Common Variable Immunodeficiency with Immune Dysregulation. J Clin Immunol 2021, 41(6), 1250–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kralickova, P; Milota, T; Litzman, J; Malkusova, I; Jilek, D; Petanova, J; Vydlakova, J; Zimulova, A; Fronkova, E; Svaton, M; Kanderova, V; Bloomfield, M; Parackova, Z; Klocperk, A; Haviger, J; Kalina, T; Sediva, A. CVID-Associated Tumors: Czech Nationwide Study Focused on Epidemiology, Immunology, and Genetic Background in a Cohort of Patients With CVID. Front Immunol 2019, 9, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopes, J; Peixoto, M; Antunes, E; Silva, I; Caridade, S. Secondary Amyloidosis and Common Variable Immunodeficiency: A Rare Association. Cureus 2022, 14(11), e31976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moy, L.N.; et al. ‘Pulmonary Al Amyloidosis: A review and update on treatment options’. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 2022, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiqi, MH; McPhail, ED; Theis, JD; Dasari, S; Vrana, JA; Drosou, ME; Leung, N; Hayman, S; Rajkumar, SV; Warsame, R; Ansell, SM; Gertz, MA; Grogan, M; Dispenzieri, A. Two types of amyloidosis presenting in a single patient: a case series. Blood Cancer J 2019, 9(3), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Balwani, Manish R; et al. Secondary renal amyloidosis in a patient of pulmonary tuberculosis and common variable immunodeficiency. Journal of nephropharmacology 2015, vol. 4, 2 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, Z; Gursu, M; Ozturk, S; Kilicaslan, I; Kazancioglu, R. A case of primary immune deficiency presenting with nephrotic syndrome. NDT Plus Epub. 2010, 3(5), 456–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SOYSAL, D; TÜRKKAN, E; KARAKUŞ, V; TATAR, E; KABAYEĞİT, Ö. Y; AVCI, A. A case of common variable immunodeficiency disease and thyroid amyloidosis. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 2009, 39(3), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borte, Stephan; et al. Novel NLRP12 mutations associated with intestinal amyloidosis in a patient diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.) 2014, vol. 154(2), 105–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik; Ferhat, Aykut; et al. Association of secondary amyloidosis with common variable immune deficiency and tuberculosis. Yonsei medical journal 2005, vol. 46(6), 847–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiroğlu, AK; Yıldırım, Y; Yılmaz, Z; Kayabaşı, H; Avcı, Y; Yıldırım, MS; Yılmaz, ME. A rare cause of secondary amyloidosis: common variable immunodeficiency disease. Case Rep Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 860208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Firinu, D; et al. Systemic reactive (AA) amyloidosis in the course of common variable immunodeficiency. Amyloid: the international journal of experimental and clinical investigation: the official journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis 2011, vol. 18 Suppl 1, 214–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delplanque, Marion; et al. AA Amyloidosis Secondary to Primary Immune Deficiency: About 40 Cases Including 2 New French Cases and a Systematic Literature Review. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice 2021, vol. 9(2), 745–752.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan; Sevket; et al. Common variable immunodeficiency and pulmonary amyloidosis: a case report. Journal of clinical immunology 2015, vol. 35(4), 344–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira, T; Sousa, R; Cordeiro, A; Ilgenfritz, R; Borralho, P. Intestinal Amyloidosis in Common Variable Immunodeficiency and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2015, 2015, 405695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kotilainen, P; et al. Systemic amyloidosis in a patient with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Journal of internal medicine 1996, vol. 240(2), 103–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, K; Anil, M; Solak, Y; Atalay, H; Esen, H; Tonbul, HZ. A hepatitis C-positive patient with new onset of nephrotic syndrome and systemic amyloidosis secondary to common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Saudi Med. 2010, 30(5), 401–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aghamohammadi, A; et al. Renal amyloidosis in common variable immunodeficiency. Nefrologia: publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola Nefrologia 2010, vol. 30(4), 474–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caza, T.N.; Hassen, S.I.; Larsen, C.P. ‘Renal manifestations of common variable immunodeficiency’. Kidney360 2020, 1(6), 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, S; Gilbertson, JA; Rendell, N; Whelan, CJ; Lachmann, HJ; Wechalekar, AD; Hawkins, PN; Gillmore, JD. Two types of amyloid in a single heart. Blood 2014, 124(19), 3025–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jhaveri; Tulip; et al. Once AL amyloidosis: not always AL amyloidosis. Amyloid: the international journal of experimental and clinical investigation: the official journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis 2018, vol. 25(2), 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, Riccardo; et al. Two types of systemic amyloidosis in a single patient. Amyloid: the international journal of experimental and clinical investigation: the official journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis 2020, vol. 27(4), 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, M.G.; Kindle, G.; Gathmann, B.; Quinti, I.; Buckland, M.; van Montfrans, J.; Scheible, R.; Rusch, S.; Gasteiger, L.M.; Grimbacher, B.; et al. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) Registry Working Definitions for the Clinical Diagnosis of Inborn Errors of Immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S; Chapel, H; Litzman, J. When to initiate immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IGRT) in antibody deficiency: a practical approach. Clin Exp Immunol 2017, 188(3), 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Resnick, ES; Moshier, EL; Godbold, JH; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Morbidity and mortality in common variable immune deficiency over 4 decades. Blood. Published online. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, M; Aghamohammadi, A; Rezaei, N. Evaluation of immunoglobulin levels and infection rate in patients with common variable immunodeficiency after immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010, 43(1), 11–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Soon Sung; et al. Genetic diagnosis of inborn errors of immunity using clinical exome sequencing. Frontiers in immunology 2023, vol. 14 1178582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandham, AK; Gayathri, AR; Sundararajan, L. Pulmonary amyloidosis: A case series. Lung India 2019, 36(3), 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasib Sidiqi, M; Gertz, Morie A. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis diagnosis and treatment algorithm 2021 Patterns of pulmonary involvement in systemic amyloidosis. Blood cancer journal 2021, vol. 11, 5 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (No date) UpToDate. 17 July 2025. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-laboratory-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-immunoglobulin-light-chain-al-amyloidosis?search=al+amyloidosis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~97&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H143177.

- Resnick, E.S.; Cunningham-Rundles, C. The many faces of the clinical picture of common variable immune deficiency. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 12, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quock, TP; Yan, T; Chang, E; Guthrie, S; Broder, MS. Epidemiology of AL amyloidosis: a real-world study using US claims data. Blood Adv 2018, 2(10), 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martini, Francesca; et al. Different types of amyloid concomitantly present in the same patients. Hematology reports 2019, vol. 11, 4 7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, An-Li; et al. Two Kinds of Cardiac Amyloidosis in One Patient: A Case Report. Acta Cardiologica Sinica 2022, vol. 38(6), 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, Yuko; et al. Coexistence of variant-type transthyretin and immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis: a case report. European heart journal. Case reports 2024, vol. 8, 6 ytae264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gami, Abhishek; et al. Coexistence of Light Chain and Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC. Case reports 2024, vol. 29, 7 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esenboga, S; Çagdas Ayvaz, D; Saglam Ayhan, A; Peynircioglu, B; Sanal, O; Tezcan, I. CVID Associated with Systemic Amyloidosis. Case Reports Immunol. 2015, 2015, 879179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peralta, AR; Shadid, AM. The Role of Bronchoscopy in the Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. J Clin Med 2025, 14(9), 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al Hamed, R.; Bazarbachi, A.H.; Bazarbachi, A.; et al. Comprehensive Review of AL amyloidosis: some practical recommendations. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirioglu, S; Uludag, O; Hurdogan, O; Kumru, G; Berke, I; Doumas, SA; Frangou, E; Gul, A. AA Amyloidosis: A Contemporary View. Curr Rheumatol Rep.;Epub 2024, 26(7), 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cunningham-Rundles, C; Bodian, C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol 1999, 92(1), 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouillot, G; Carmagnat, M; Gérard, L; Garnier, JL; Fieschi, C; Vince, N; Karlin, L; Viallard, JF; Jaussaud, R; Boileau, J; Donadieu, J; Gardembas, M; Schleinitz, N; Suarez, F; Hachulla, E; Delavigne, K; Morisset, M; Jacquot, S; Just, N; Galicier, L; Charron, D; Debré, P; Oksenhendler, E; Rabian, C; DEFI Study Group. B-cell and T-cell phenotypes in CVID patients correlate with the clinical phenotype of the disease. J Clin Immunol 2010, 30(5), 746–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreau, M; Vigano, S; Bellanger, F; Pellaton, C; Buss, G; Comte, D; Roger, T; Lacabaratz, C; Bart, PA; Levy, Y; Pantaleo, G. Exhaustion of bacteria-specific CD4 T cells and microbial translocation in common variable immunodeficiency disorders. J Exp Med. 2014, 211(10), 2033–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khoor, A; Colby, TV. ‘Amyloidosis of the lung’. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 2017, vol. 141(no. 2), 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A; Lawton, E; Smith, S; Kalro, A; Geake, J. Pulmonary AL amyloidosis and multiple myeloma presenting as cough with diffuse pulmonary opacities. Respirol Case Rep. 2021, 9(7), e00786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mirioglu, S; Uludag, O; Hurdogan, O; Kumru, G; Berke, I; Doumas, SA; Frangou, E; Gul, A. AA Amyloidosis: A Contemporary View. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2024, 26(7), 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, JD; Benson, MD; Buxbaum, JN; et al. Nomenclature 2014: Amyloid fibril proteins and clinical classification of the amyloidosis. Amyloid 2014, 21(4), 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. Embase. n.d. Available online: https://www.embase.com/.

- Elsevier. Scopus. n.d. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/.

- Clarivate Analytics. Web of Science [online]. n.d. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/.

- Bou Zerdan, M; Nasr, L; Khalid, F; Allam, S; Bouferraa, Y; Batool, S; Tayyeb, M; Adroja, S; Mammadii, M; Anwer, F; Raza, S; Chaulagain, CP. Systemic AL amyloidosis: current approach and future direction. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).