Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This paper presents a fully articulated semi-presidential constitutional scheme (Scheme C) that embraces parliamentary fragmentation and minority governments as the new normal rather than pathologies requiring cure. Evolved from Schemes A and B, it strengthens prime-ministerial counterweights against the assembly. The scheme fuses (i) Westminster-style executive continuity and prime-ministerial dissolution initiative, (ii) French-style presidential authority in foreign and defence policy plus a robust legislative veto, (iii) synchronised presidential-legislative elections complemented by semi-mid-term legislative contests, and (iv) a game-based investiture rule paired with an innovative two-tier no-confidence procedure, both anchored in formal legislative confidence. Scheme C thereby achieves an unprecedented synthesis: more parliamentary than classic president-parliamentary or premier-presidential systems, more stable than Westminster models amid fragmented legislatures, and endowed with stronger mid-term democratic correctives than existing benchmarks. Its architecture simultaneously shields the prime minister from presidential overreach, the president from parliamentary extortion, and the state from governmental paralysis or authoritarian drift---even under unified political control of both branches. Scheme C is thus advanced not as theoretical speculation but as a coherent, stress-tested model ready for adoption in contemporary democracies facing persistent legislative fragmentation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Scheme B provides the prime minister with no countercheck whatsoever against parliamentary obstruction.

- Scheme A appears to grant the prime minister a dissolution threat through its “Request for Successor” procedure. In practice, however, a risk-averse assembly (throughout this paper “assembly” refers to the entire legislative body in unicameral systems or to the lower house in bicameral systems). can simply pre-empt dissolution by electing a new prime minister who, once in office, may still be denied meaningful legislative support. The originally intended countercheck is thereby neutralised.

- Assembly and presidential terms are synchronised and fixed at five years.

- The prime minister may trigger early assembly elections only during a narrowly defined mid-term window (after the assembly has served more than two years but with more than one year remaining).

- An assembly elected in a snap election serves only the remainder of the original term and, crucially, the newly appointed prime minister enjoys no further dissolution right during that shortened period.

2. Dissolution Powers and Prime-Ministerial Countercheck

2.1. Untriggered Dissolution

- Head of state retains formal discretion but almost never refuses: India, Israel (until 2022), and historically Japan. Refusal would provoke a major constitutional crisis and has therefore remained exceptional or non-existent in practice [3].

2.2. Triggered Dissolution

- Head of state has no discretion: Greece (Art. 41 § 2: after a successful constructive vote of no-confidence, the new prime minister may request dissolution if he or she wishes early elections; the president is obliged to grant it) and Papua New Guinea (similar obligatory dissolution after a successful no-confidence vote against the prime minister). The head of state acts automatically on the prime minister’s request [5].

- Head of state retains discretion: Germany (Art. 68: the chancellor may ask the Bundestag for a vote of confidence and deliberately lose it; the federal president then decides within 21 days whether to dissolve or not) and Armenia (similar procedure: after a lost confidence vote the prime minister may propose dissolution, but the president may refuse). In both cases the prime minister personally initiates the request, yet the head of state can legally deny it [5,6].

2.3. Presidential Initiative

- Russia (Art. 109–111 of the 1993 Constitution): the president may dissolve the State Duma after three failed investiture votes or a successful no-confidence vote; the prime minister’s role is limited to non-binding consultation [6].

- Romania post-2003 (Art. 89): the president may dissolve the assembly only after two failed investiture attempts within 60 days, following consultation with the parliamentary party leaders and the presidents of the chambers; the prime minister has no independent initiative [8].

- Bulgaria (Arts. 99 and 64): dissolution is automatic or presidential after three failed government-formation attempts; the president orchestrates the entire process and sets the election date with no prime-ministerial proposal right.

- Sri Lanka (pre-2015) and Peru under Fujimori (1993–2000): classic president-parliamentary designs in which the president held unilateral dissolution power, often exercised against a hostile legislature [10].

3. The Reinforced Countercheck Scheme (Scheme C)

3.1. The Core Investiture Articles

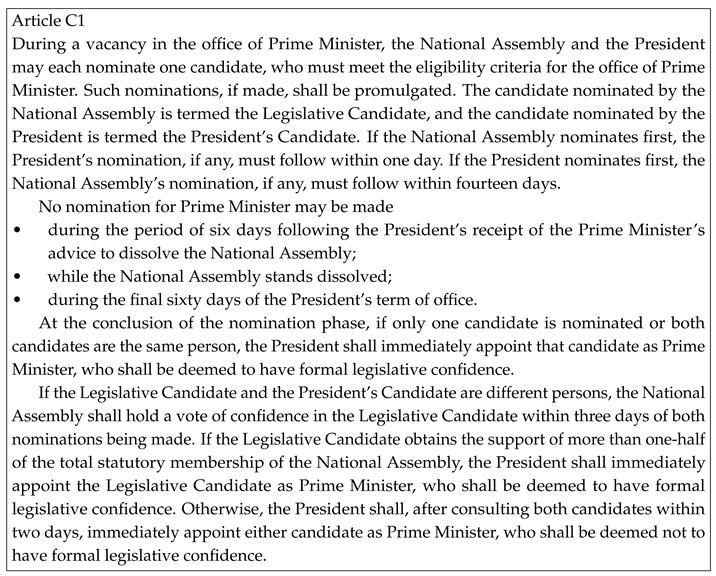

- Article C1 establishes the procedural framework governing the interaction between the assembly and the president as they vie for the appointment of their preferred candidate. This rule effectively eliminates the deadlocks commonly encountered in traditional approval processes found in many semi-presidential systems [2]. Furthermore, it proves resilient in situations where the assembly is highly fragmented [1], ensuring that the appointment process remains functional even in politically divided environments.

- Article C1 prohibits the nomination for Prime Minister in three defined circumstances. The underlying rationales for the second and third prohibitions are easy to understand, and the rationale for the first will be examined in subsection 3.4.

- Article C2 addresses situations in which the office of Prime Minister remains vacant for an extended period. As stipulated in Article C1, there are three cases in which the nomination for Prime Minister is temporarily blocked. Additionally, there is the theoretical case in which both the assembly and the president indefinitely delay making a nomination. In all such cases, Article C2 provides the mechanism for designating a caretaker Prime Minister to ensure the continuity of government.

- Article C3 imposes a strict ceiling on the number of members of the assembly who may simultaneously serve in the cabinet. Unlike the corresponding rules in the author’s earlier Schemes A and B—which severely restricted or even prohibited ministerial office for sitting MPs in order to strengthen separation of powers—Article C3 deliberately aligns the cabinet’s composition with the prevailing practice in most contemporary semi-presidential systems (France, Portugal, Poland, Romania, etc.), where a substantial share of ministers are drawn from the legislature. This shift should not, however, be understood as a core defining feature of the overall constitutional model presented here. The central innovations of the scheme continue to lie in the investiture, removal, and dissolution rules; Article C3 is an ancillary design choice to enhance coalition manageability.

3.2. The Electoral and Terming Articles

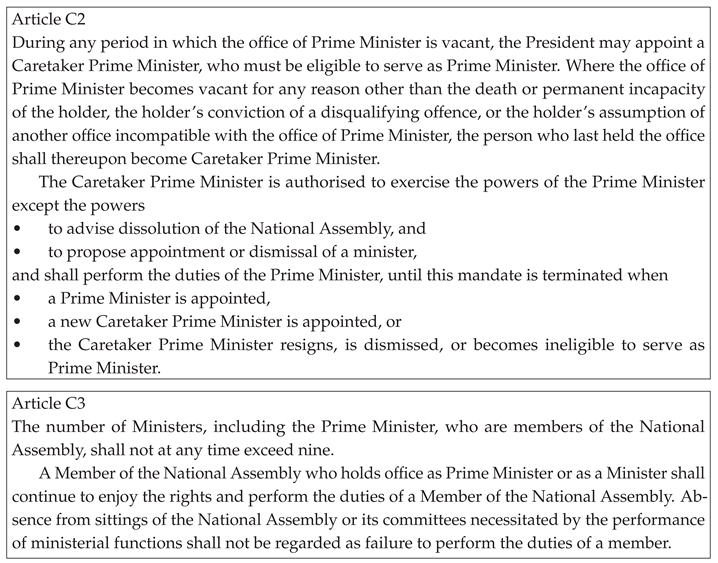

- Electoral concurrency sharply reduces the probability of cohabitation. Extraordinary general elections (the ones triggered by early dissolution) are uncommon. The overwhelming majority of general elections are therefore the ordinary ones held concurrently at the end of the regular five-year term. When a president and legislature are elected at the same time by the same voters, their political orientations are typically similar. The probability of cohabitation—the situation in which the president and the parliamentary majority belong to opposing political forces—is sharply reduced.

- Concurrent renewal strengthens the accountability of the entire regime to the electorate. In staggered systems, when a policy fails or succeeds, it is much harder for the electorate to identify who—the president, the assembly, or the cabinet—should be blamed or praised for that failure or success. Simultaneous renewal removes this ambiguity by making the entire regime jointly accountable.

- Concurrent renewal enhances cabinet stability. The prime minister and cabinet must work with both the president and the assembly for effective governance. Synchronising the two mandates eliminates nearly half of occasions that typically cause cabinet reshuffles or early terminations.

- Concurrency lowers electoral costs and raises participation. A single election day lowers administrative costs and consistently produces higher turnout, as voters make only one trip to the polling station for the two most important elections.

- Note on the specific dates: The choice of the second Tuesday of October for ordinary general elections and the December inauguration dates are not essential features of the scheme. They have been selected as realistic, turnout-friendly, and logistically convenient defaults that can be adopted without modification in most countries. They may, however, be freely adjusted to suit local traditions, climate, or administrative circumstances without affecting the core constitutional logic of the model.

- Note on possible presidential run-off: The provisions above assume that the president (and vice president) are elected in a single round. Countries that prefer a two-round majority run-off system may easily accommodate it by providing that, if no candidate obtains the required majority in the first round, a run-off between the two leading candidates shall be held two weeks thereafter. The inauguration date of the president (and vice president) requires no adjustment even if a run-off is held. The interval from a late-October or early-November run-off to mid-December remains fully sufficient for result certification, legal challenges, and an orderly transition.

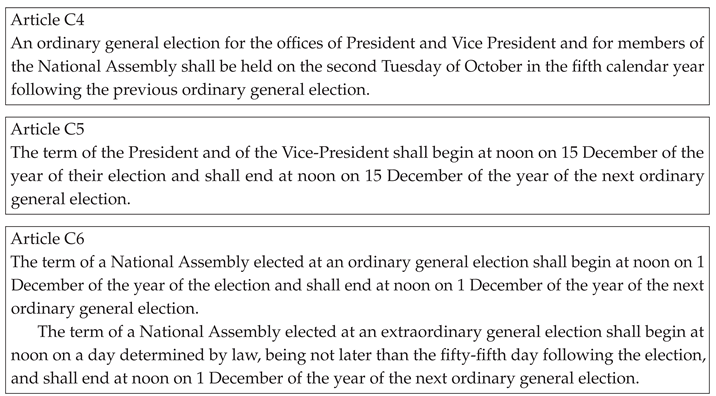

3.3. The No-Confidence Article

- This article employs a safeguard against frivolous no-confidence motions: a minimum signature threshold. Meanwhile, it is also flexible enough for the assembly to introduce further measures if needed.

-

In earlier Schemes A and B, an ordinary no-confidence vote carried by simple majority would have made minority governments extremely fragile. We therefore initially believed a constructive vote of no-confidence was the only viable protection. We now see that the same stabilising effect can be obtained more simply by raising the threshold required to actually remove the prime minister. Under the new mechanism:

- A classic absolute majority (>50 %) is still enough to withdraw formal legislative confidence and expose the prime minister to possible presidential dismissal.

- Actual removal by the assembly alone, however, requires a qualified majority of more than five-ninths (5/9 ≈ 55.56 %) of the total statutory membership.

Thus, minority governments are shielded from casual parliamentary harassment, yet a broad negative coalition can still force the prime minister out in a genuine crisis. At the same time, if the president also wishes to replace a prime minister who has lost ordinary confidence, the difficulty remains exactly the same as under a traditional no-confidence rule. - The fraction 5/9 was chosen because it is the lowest “clean” supermajority (small-integer fraction) that is unmistakably higher than 50%, yet does not make removal excessively hard. The 5/9 threshold reflects our reasoned design intuition; its optimality can only be fully assessed after extended real-world application of the scheme. Nearby fractions such as 4/7 (≈ 57.14 %) or 6/11 (≈54.55 %) may be plausible alternatives.

- Paragraph 3 allows the prime minister to remain in office for up to four full days after a motion of no-confidence has been adopted at the strong level. This brief grace period is intentional: It gives the prime minister the necessary time to arrange and hold the meeting with the president, which is required to formally advise dissolution of the assembly (should he or she so decides). Without these four days, the prime minister would be instantly removed upon the vote and would lose the constitutional authority to call an early election.

- The constructive vote of no-confidence and the core investiture rule in Article C1 share essentially the same underlying logic: the assembly can install a prime minister if it already agrees on a candidate. That is why, in the old Schemes A and B, it was equally easy (or difficult) for the assembly to install its preferred choice of Prime Minister, whether the office was vacant or not. The current scheme deliberately breaks that symmetry. Here, if the office of Prime Minister is occupied, the assembly must first clear the 5/9 supermajority required for removal, then the normal (lower-threshold) investiture process apply. We regard this asymmetry as a feature, not a bug. By making it significantly harder for the assembly alone to topple a prime minister, the new mechanism greatly strengthens government stability—an objective we place at the very top of constitutional priorities.

-

The constructive vote of no-confidence is abandoned here for three reasons:

- As we have just discussed, the threshold for such a vote should be set higher than one-half, in order to create a greater hurdle than what is required when the office is vacant. That said, since the same effect can be achieved through an ordinary vote of no-confidence, one might question the necessity of the constructive version. After all, the constructive vote of no-confidence is often considered more cumbersome and complicated than the ordinary version.

- Candidates in a constructive vote of no-confidence are typically chosen on an ad-hoc basis by parliamentary groups, without any structured selection process or presidential involvement. This tends to favour high-profile or media-savvy individuals rather than those best qualified to form a stable government.

- Perhaps most importantly, with constructive vote of no-confidence, the sitting prime minister is immediately replaced by a successor when the motion of no-confidence is (strongly) passed. This prevents the sitting prime minister from countering the motion by advising the dissolution of the assembly, which is considered an unwelcome feature as we value every mechanism to strengthen a minority government. This may also be a key reason why Westminster countries have not adopted the constructive vote of no-confidence.

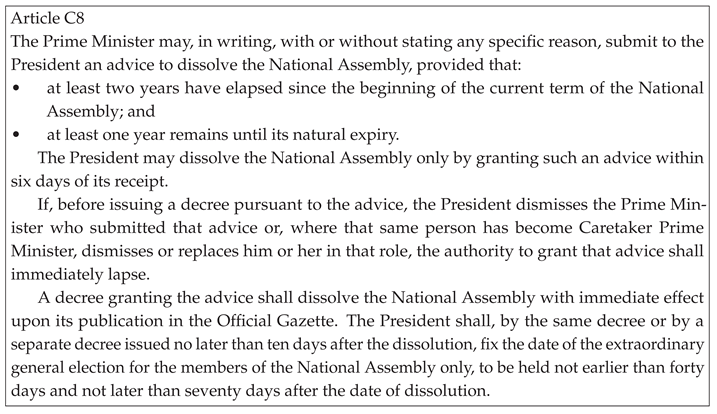

3.4. The Dissolution Article

- Although never stated outright, the twin restrictions (at least two years served and at least one year remaining) together guarantee that within a normal five-year term there can be at most one dissolution and therefore at most one snap election. We deliberately avoided an explicit “only once per term” rule. The implicit version is superior because it automatically produces two reasonably balanced parliamentary terms. This creates a genuine mid-term parliamentary election—a feature normally found only in pure presidential systems—but with two important improvements: ours is flexible (it occurs “around the middle” rather than rigidly at the halfway mark, and it is contingent and infrequent rather than automatic and guaranteed every term. Hence, the result is a hybrid mechanism that borrows the stabilising rhythm of American-style mid-terms while preserving full parliamentary logic and avoiding the forced, mechanical cadence of fixed-term presidential legislatures.

- Placing the initiative with the prime minister (rather than the president) is a deliberate and crucial safeguard. Given the president’s higher ceremonial rank, if the president had the initiative to dissolve the assembly, the prime minister’s opinion would be reduced to mere advice. A strong-willed president could easily use dissolution as a political weapon to discipline or eliminate an uncooperative parliamentary majority—reproducing the well-known “presidential conquest of parliament” problem seen in some semi-presidential systems. In our design, dissolution instead requires the active concurrence of both heads of the executive: the prime minister must take the political risk of requesting it, and the president must agree to grant it. This high double hurdle means that dissolution will almost never be used for partisan manoeuvring. The only realistic scenario in which both will agree is when the assembly has become deeply fragmented or ungovernable and the prime minister—having lost workable parliamentary support—turns to the president as an ally of last resort. Such acute deadlock is, by design, extremely uncommon. That is precisely why the article imposes no additional triggers or justifications for the prime minister’s advice.

-

A legitimate concern is that, while the probability density of dissolution at any single moment is extremely low, the two-year window is long enough for the cumulative probability to become significant. Some drafters therefore believe restrictions are needed. We remain neutral on that question, but two points deserve attention:

- General elections in the United States occur every two years. Under the present scheme, even with one snap election per five-year term, the average interval between elections is 2.5 years—meaning elections remain less frequent than in the United States.

- A prime minister who advises dissolution on insufficient grounds will face strong disapproval from deputies, sharply reducing his or her chances of re-election as prime minister. This heavy political cost serves as a powerful deterrent against abusive dissolutions.

- The current mechanism also clearly outperforms the earlier “Request for Successor” (RFS) model we considered. Under RFS, deputies who feared losing their seats could be pressured into installing a prime minister they only half-heartedly supported, simply to avoid immediate dissolution. Once the new government was in place, however, nothing stopped the same deputies from obstructing major legislation with impunity. The RFS therefore offered no lasting penalty for parliamentary obstructionism and left the prime minister without any credible counter-threat. By contrast, the present system gives the prime minister a powerful, ongoing deterrent. He or she can quietly monitor each member’s voting record and level of cooperation on ordinary legislation and, when the two-year window opens, decide—in coordination with the president and guided by public opinion—whether to advise dissolution and at the most advantageous moment. The possibility of an early election thus becomes a real, selective sanction that encourages responsible behaviour throughout most of the term. The sole period in which this lever is unavailable is the interval immediately following a snap election. This temporary asymmetry is acceptable, as prime-ministerial countercheck is not the only quality indicator of a constitutional scheme.

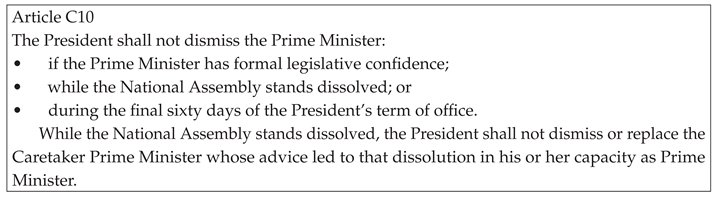

- Paragraph 3 may appear unusual at first glance, but it serves an important purpose. Once the assembly is dissolved, the prime minister (or the same person continuing as caretaker) is expected to lead the governing side’s election campaign. Retaining the office throughout the campaign is a significant political advantage. For the president to remove that person would be an act of extreme political hostility that could decisively tilt the electoral playing field. Although such presidential interference would be almost unthinkable in stable democracies, the constitution must still forbid it explicitly. No living constitution contains an identical rule, for a simple reason: every existing system that grants the prime minister genuine initiative in dissolution is a Westminster-style parliamentary country, where the head of state is ceremonial and constitutionally incapable of dismissing the prime minister. In a semi-presidential framework like ours, where the president possesses real executive power, this additional safeguard is both novel and indispensable.

- Remember in Section 3.1 that Article C1 establishes a prohibition on nomination “during the six-day period following the President’s receipt of the Prime Minister’s advice to dissolve the National Assembly”. Consider the scenario without this prohibition: The prime minister submits advice for dissolution, then suddenly resigns, and the president nominates a candidate for Prime Minister. The president then proceeds to dissolve the assembly, leaving it unable to nominate its own candidate. In this case, the president would be free to appoint his or her own choice as Prime Minister. This prohibition is intended to close that potential loophole.

3.5. The Dismissal Provisions

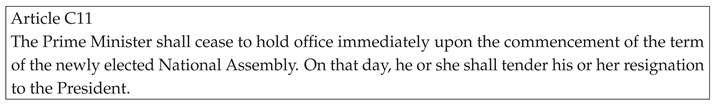

3.6. The Prime Minister Resignation Article

- When the general election is an ordinary one, the president who receives the prime minister’s resignation is still the outgoing president; the newly elected president takes office only two weeks later. Article C1 prohibits any nomination for the new prime minister during this brief interregnum. However, the newly convened assembly is free to immediately begin its own internal proceedings—including the official nomination process at parliamentary level, debates, and any required hearings or votes—while informal consultations and inter-party negotiations may of course continue in parallel.

- The present scheme deliberately avoids the traditional terms “government” and “cabinet” in formal text. The reason is simple: unlike classic parliamentary systems, the tenure of individual ministers is not tied to that of the prime minister. Ministers remain in office until they resign voluntarily or are dismissed by the president upon the proposal of a new prime minister. This decoupling can produce the seemingly odd situation in which the prime minister has already been reduced to caretaker status (or has even completely left), while the ministers he or she leads continue to hold full office and exercise their powers. Although unusual at first glance, this arrangement ensures continuity of day-to-day administration during transition periods.

-

Scheme B contained a special “prime-ministerial resignation provision” (Provision B5, treated here as Article B5). Although Article B5 and the present Article C11 appear similar at first glance, they are based on different mechanisms.

- Article B5 existed solely to enable a newly elected president to replace an incumbent prime minister, because the president otherwise normally lacked the power of dismissal. No parallel mechanism was needed for the assembly, which could appoint (or replace) a prime minister at any time, vacancy or not.

- Article C11, by contrast, is designed primarily to allow a newly elected assembly to install its own prime minister. Because presidential and legislative elections are concurrent, the same article simultaneously (and without additional machinery) empowers the newly elected president to do the same.

This elegant dual effect—serving both the new assembly and the new president through a single provision—is the direct and intended consequence of electoral synchronisation.

3.7. Implicit Semi-Presidential Background Rules

- Acts of the president that the constitution expressly subjects to the countersignature of the prime minister (or another minister) are devoid of legal effect unless countersigned. Conversely, acts of the president that the constitution does not require to be countersigned are valid without ministerial countersignature and engage only the president’s own authority.

- The president appoints and dismisses ordinary ministers solely on the proposal of the prime minister; no parliamentary approval is required for such appointments or dismissals.

- The term of the president, the tenure of the prime minister, and the tenure of ordinary ministers are mutually independent.

- Legislative veto power: The president may veto legislation (subject to the usual constitutional override mechanisms). This power, comparable to that exercised by the presidents of Poland, Portugal, and Ukraine, enables the executive to check an overreaching parliamentary majority and improves the government’s negotiating leverage with parliamentary factions.

- Reserved domain in defence and foreign affairs: The president retains final authority over the appointment of the Ministers of Defence and Foreign Affairs as well as the direction of military and foreign policy, following the well-established French model and practices in several other semi-presidential systems.

4. Comparative Analysis and Discussions

4.1. Comparison Between Scheme C and Schemes A,B

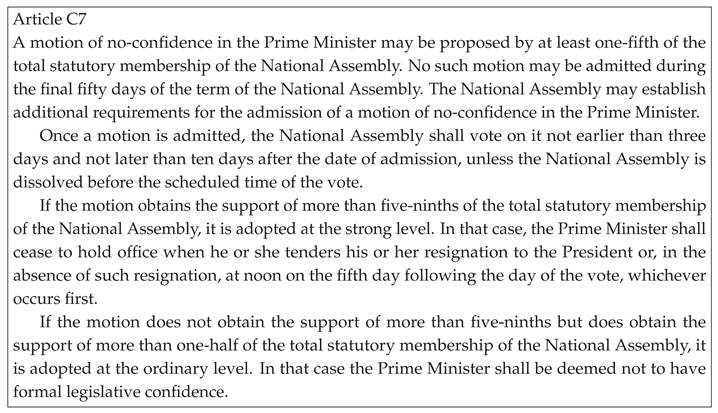

| Aspect | Article in Scheme C | Counterpart in Schemes A,B | Nature of Inheritance |

| Investiture during Vacancy | Article C1 | Article A1 | Nearly the same |

| Caretaker Prime Minister | Article C2 | Articles A2,B2 | Nearly the same |

| Composition of Cabinet | Article C3 | Articles A3,B3 | Major shift from Separation of Powers to Capped Legislative-Executive Overlap |

| Vote of No-Confidence | Article C7 | Articles A4,B4 | Major shift from constructive to ordinary vote of no-confidence, two levels of adoption, supermajority required for immediate removal |

| Dissolution of Assembly | Article C8 | Article A5 | Major shift from Request for Successor to Prime-Ministerial Advice Subject to Presidential Discretion |

| Presidential Dismissal | Article C10 | Provisions A6,B6 | Minor change, all based on formal legislative confidence |

| Prime Minister Resignation | Article C11 | Provision B5 | Seemingly similar, but in fact based on different mechanisms |

| Elections and Terming | Articles C4-C6 | None | Inspired from the American model |

4.2. Comparison Between Scheme C and the Constitutions of Westminster Countries, France, and the United States

4.3. A Note on Formal Legislative Confidence

4.4. Anti-Dictatorship Tendency of Scheme C

5. Conclusions

- a fully theorised, deadlock-proof investiture procedure capable of producing and sustaining minority governments;

- the principle of formal legislative confidence (FLC), which finally gave constitutional shape to the president’s dismissal power;

- a carefully delineated regime for the caretaker prime minister, whose value had only been discovered when designing this latest scheme.

- The short-lived “Request for Successor” device was discarded; it could not reliably compel parliamentary cooperation and merely complicated the text.

- Direct dissolution returned to the table, this time unencumbered by constructive-vote requirements or complex triggers. Among the available models, the Westminster tradition of prime-ministerial initiative offered the cleanest and most proven solution—and was therefore adopted.

- The requirement for dissolution that both heads of the executive must concur already constitutes a stringent safeguard. Any further restrictions beyond the time window were therefore discarded: to impose them would be to signal distrust in the political judgement of the two leaders.

- Dissolution is placed in the prime minister’s hands (Westminster).

- The president retains the discretion on dissolution, a reserved domain and veto (France).

- Elections follow an American-style synchronised and semi-mid-term rhythm.

- Confidence mechanism is unique among existing constitutions. Votes of confidence are constitutionally recognised only during investiture. The vote of no-confidence, by contrast, is highly innovative: it operates at two levels of adoption. Strong adoption immediately removes the prime minister; ordinary adoption merely deprives him of formal legislative confidence (FLC). The underlying procedure remains the classic (non-constructive) no-confidence vote. This two-tier design deliberately protects minority governments while preserving the ultimate parliamentary accountability.

References

- Cheng, Y. (2025b). Game-based schemes for prime minister selection in multi-party semi-presidential systems (Preprint). Preprints.org. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202507.2439. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. (2025a). A game-based scheme for prime minister approval in Korea-like presidential systems (Preprint). Preprints.org. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202501.0454.v3. [CrossRef]

- Becher, M., & Christiansen, F. J. (2015). Dissolution threats and legislative bargaining. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 641–655. [CrossRef]

- Schleiter, P., & Morgan-Jones, E. (2009). Constitutional power and competing risks: Monarchs, presidents, prime ministers, and the termination of east and west european cabinets. American Political Science Review, 103(3), 496–512. [CrossRef]

- Goplerud, M., & Schleiter, P. (2016). An index of assembly dissolution powers. Comparative Political Studies, 9(4), 427–456. [CrossRef]

- Schleiter, P., & Morgan-Jones, E. (2010). Who’s in charge? Presidents, Prime Ministers, and formal powers. Comparative Political Studies, 43(11), 1415–1442. [CrossRef]

- Strøm, K. (2000). Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 261–289. [CrossRef]

- Elgie, R. (2011). Semi-presidentialism: Sub-types and democratic performance. Oxford University Press.

- Lazardeux, S. (2005). Dissolution and cohabitation in the French Fifth Republic. West European Politics, 28(5), 1005–1026. [CrossRef]

- Shugart, M. S., & Carey, J. M. (1992). Presidents and assemblies: Constitutional design and electoral dynamics. Cambridge University Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).