Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

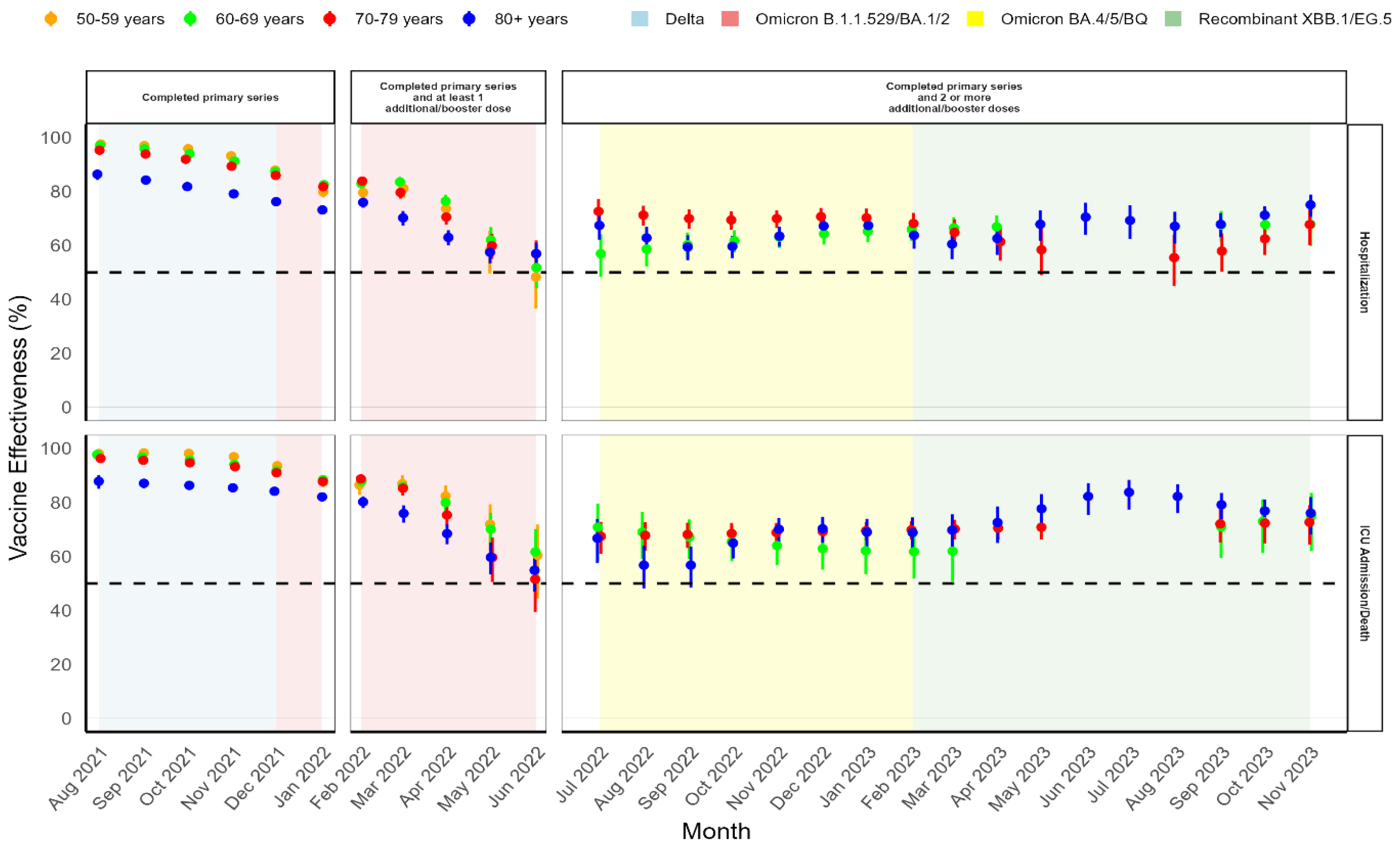

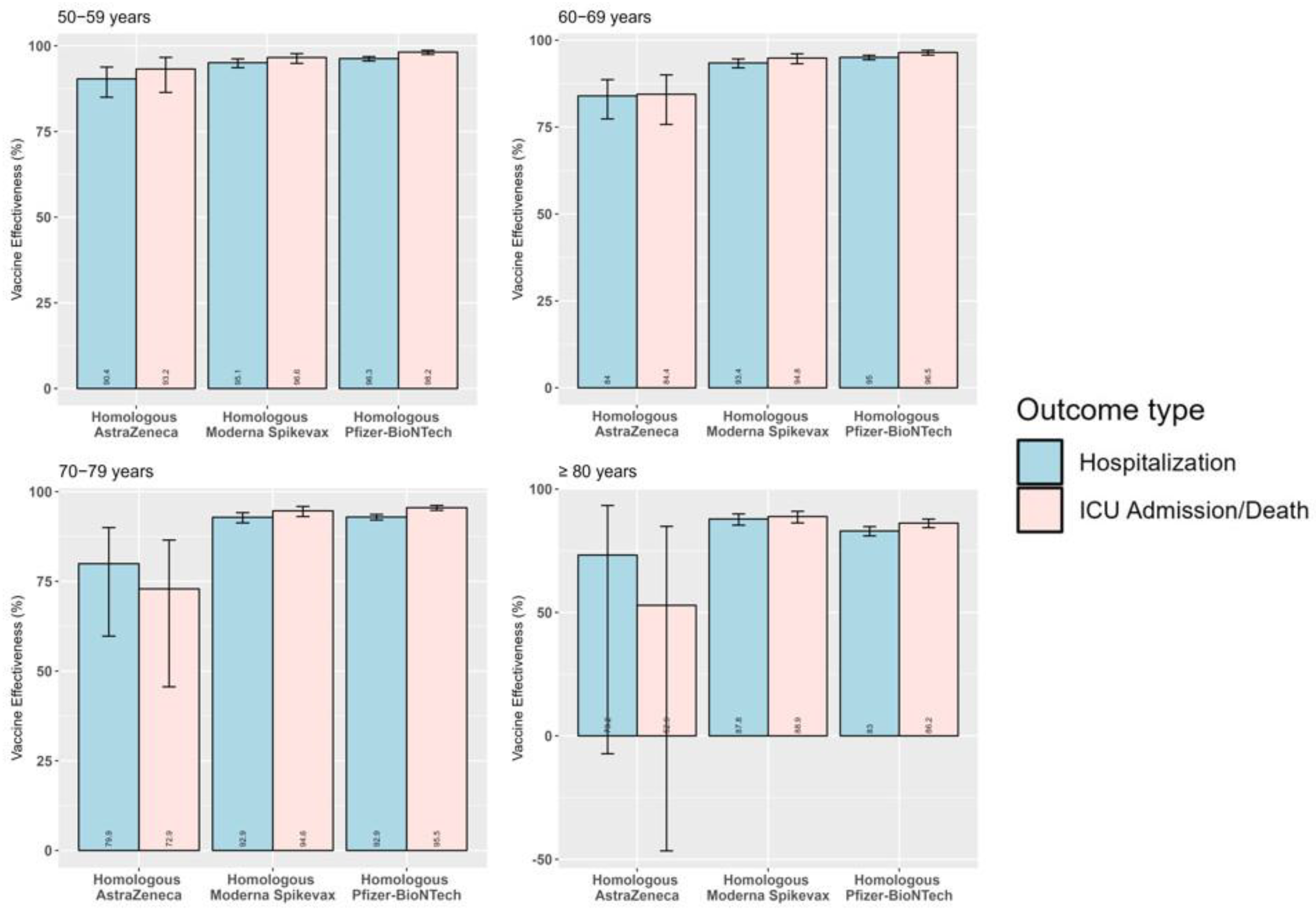

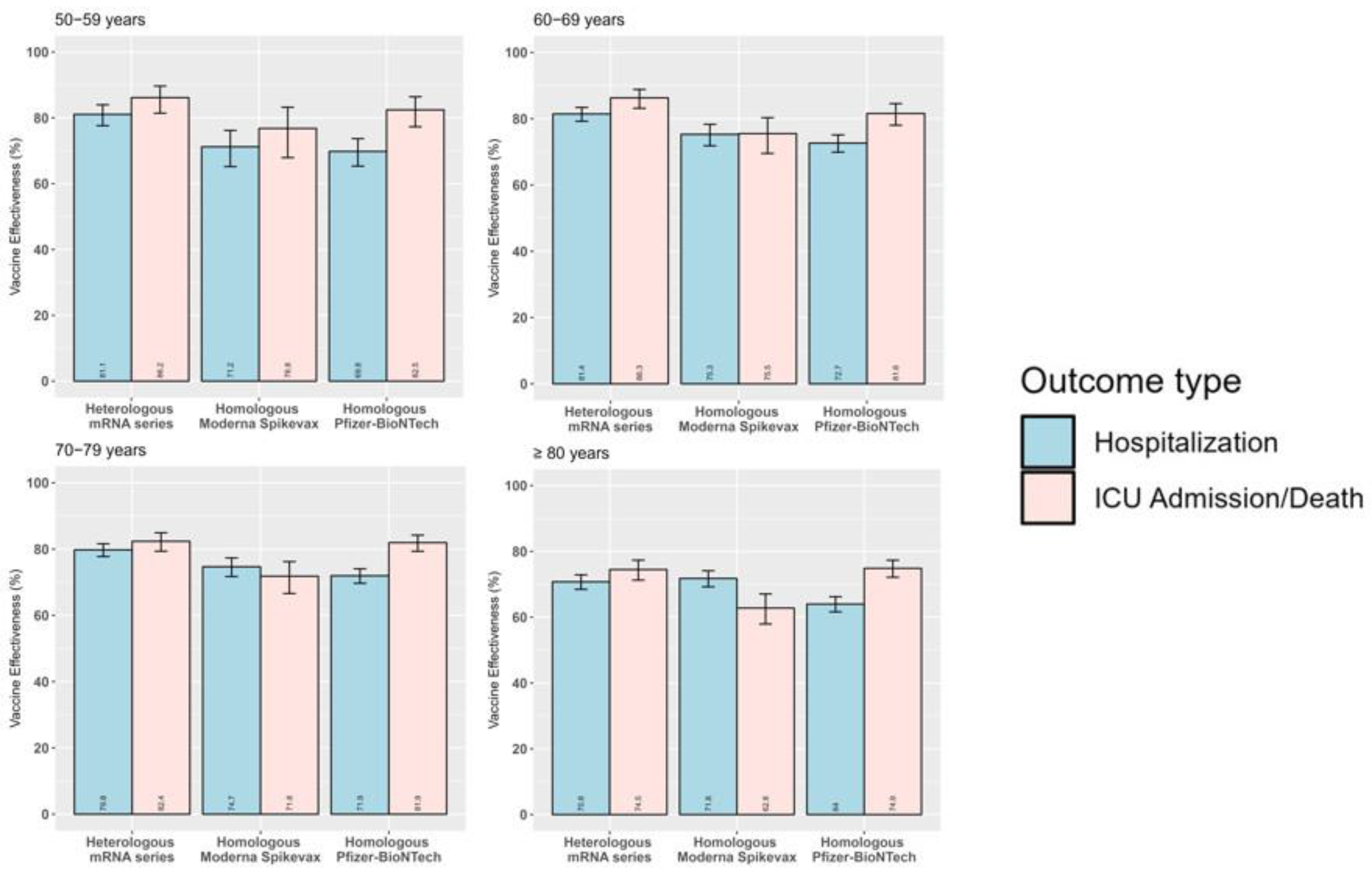

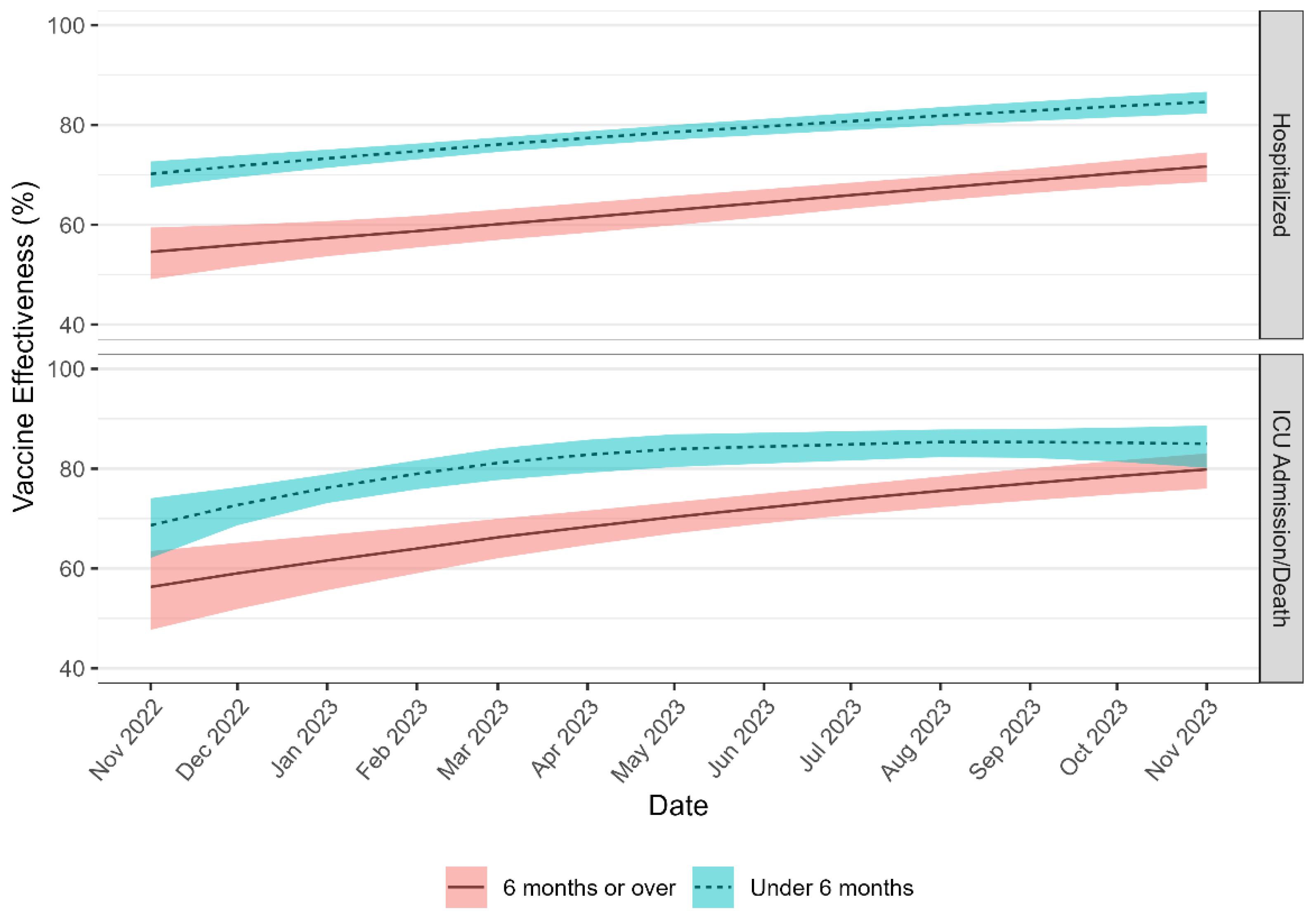

Background/Objectives: It is critical to monitor real-world COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness (VE) in older adults as they have been identified as a priority group for vaccination. This is the first study that aims to estimate national absolute vaccine effectiveness (aVE) against severe COVID-19 outcomes among Canadian older adults aged ≥ 50 years. Methods: The screening method (SM) was implemented using standard and spline-based logistic regression models to estimate aVE and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by outcome, age group, vaccination status, time since last dose, vaccine schedules, and variant of concern (VOC) period. Results: From August 1, 2021 to November 30, 2023, there were 103,822 severe COVID-19 cases, of which 72.9% were hospitalized, 8.2% were admitted to ICU, and 18.9% had died. A total of 23.1% of these cases were unvaccinated against COVID-19, 21.9% completed a primary series only, and 55.0% received at least one additional/booster dose. National aVE against severe COVID-19 outcomes remained moderate to high during Delta and original Omicron VOC predominance periods. Monthly age-specific aVE of at least two additional/booster doses remained stable during recombinant XBB.1.5/EG.5 VOC predominance, ranging from 61.0% (95% CI: 51.9–68.4%) to 69.8% (95% CI: 67.5–72.0%) against hospitalization, and 71.0% (95% CI: 62.8–77.4%) to 77.2% (95% CI: 74.2–79.9%) against ICU admission/death. Adjusted aVE was higher for last booster doses received within the past six months and with heterologous mRNA vaccine schedules. Conclusions: The SM is a useful method to estimate aVE in near real-time, enabling the assessment of temporal changes in aVE, guiding vaccine policy, and building vaccine confidence among populations at higher risk of severe outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Curation

2.3. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Predominance

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Screening Method Validation

3. Results

3.1. Severe COVID-19 Cases and Vaccination Status in Older Adults Aged ≥ 50 Years

3.2. National Absolute COVID-19 VACCINE Effectiveness

3.3. Product-Specific Absolute Vaccine Effectiveness

3.4. Absolute Vaccine Effectiveness by Time Since Last Dose

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). COVID-19 epidemiology update: Current situation. 2024. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/current-situation.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). COVID-19 vaccination: Vaccination coverage. 2024. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). National surveillance for Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/interim-guidance-surveillance-human-infection.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada COVID-19 Surveillance; Vaccine Coverage and Information System; Vaccine Effectiveness Surveillance Program; Public Health Risk Science/National Microbiology Laboratory Modelling Teams. National epidemiological analysis of the association of COVID-19 vaccination and incidence of COVID-19 cases in Canada, January to August 2021. Can Commun Dis Rep 2023, 49, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Dam, D.; Merali, S.; Chen, M.; Coulby, C.; Ho Mi Fane, B.; Bang, F.; Robson, J.; David, S. COVID-19 outcome trends by vaccination status in Canada, December 2020–January 2022. Can Commun Dis Rep 2024, 50, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Austin, P.C.; Brown, K.A.; Buchan, S.A.; Fell, D.B.; Fong, C.; Gubbay, J.B.; Nasreen, S.; Schwartz, K.L.; Sundaram, M.E.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines Over Time Prior to Omicron Emergence in Ontario, Canada: Test-Negative Design Study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022, 9, ofac449. [CrossRef]

- Widdifield, J.; Kwong, J.C.; Chen, S.; Eder, L.; Benchimol, E.I.; Kaplan, G.G.; Hitchon, C.; Aviña-Zubieta, J.A.; Lacaille, D.; Chung, H.; Bernatsky, S. Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes among individuals with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases tested between March 1 and Nov 22, 2021, in Ontario, Canada: a population-based analysis. Lancet Rheumatol 2022, 4, e430–e440. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Nguyen, L.; Buchan, S.A.; Wilson, S.E.; Costa, A.P.; Kwong, J.C. Effectiveness and Duration of Protection of a Fourth Dose of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Messenger RNA Vaccine Among Long-term Care Residents in Ontario, Canada. J Infect Dis 2023, 227, 977–980. [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, S.; Chung, H.; He, S.; Brown, K.A.; Gubbay, J.B.; Buchan, S.A.; Fell, D.B.; Austin, P.C.; Schwartz, K.L.; Sundaram, M.E.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes with variants of concern in Ontario. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 379–385. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Nguyen, L.; Austin, P.C.; Brown, K.A.; Grewal, R.; Buchan, S.A.; Nasreen, S.; Gubbay, J.; Schwartz, K.L.; Tadrous, M.; et al. Protection Conferred by COVID-19 Vaccination, Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection, or Hybrid Immunity Against Omicron-Associated Severe Outcomes Among Community-Dwelling Adults. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 78, 1372–1382. [CrossRef]

- Carazo, S.; Skowronski, D.M.; Brisson, M.; Sauvageau, C.; Brousseau, N.; Gilca, R.; Ouakki, M.; Barkati, S.; Fafard, J.; Talbot, D.; et al. Estimated Protection of Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection Against Reinfection With the Omicron Variant Among Messenger RNA-Vaccinated and Nonvaccinated Individuals in Quebec, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2236670–e2236670. [CrossRef]

- Fowokan, A.; Samji, H.; Puyat, J.; Janjua, N.; Wilton, J.; Wong, J.; Grennan, T.; Chambers, C.; Kroch, A.; Costiniuk, C.T.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people living with HIV in British Columbia and comparisons with a matched HIV-negative cohort: a test negative design. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 127, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- El Adam, S.; Zou, M.; Kim, S.; Henry, B.; Krajden, M.; Skowronski, D.M. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Effectiveness in Health Care Workers by Dosing Interval and Time Since Vaccination: Test-Negative Design, British Columbia, Canada. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022, 9, ofac178. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Nguyen, L.; Buchan, S.A.; Wilson, S.E.; Nasreen, S.; Austin, P.C.; Brown, K.A.; Fell, D.B.; Gubbay, J.B.; Schwartz, K.L.; et al. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine booster doses against Omicron severe outcomes. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1273. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Buchan, S.A.; Nguyen, L.; Nasreen, S.; Austin, P.C.; Brown, K.A.; Gubbay, J.; Lee, N.; Schwartz, K.L.; Tadrous, M.; et al. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 Monovalent and Bivalent Vaccine Booster Doses Against Omicron Severe Outcomes Among adults aged ≥50 years in Ontario, Canada: A Canadian Immunization Research Network Study. J Infect Dis 2024, 229, 394–397. [CrossRef]

- Carazo, S.; Skowronski, D.M.; Brisson, M.; Sauvageau, C.; Brousseau, N.; Fafard, J.; Gilca, R.; Talbot, D.; Ouakki, M.; Febriani, Y.; et al. Effectiveness of previous infection-induced and vaccine-induced protection against hospitalisation due to omicron BA subvariants in older adults: a test-negative, case-control study in Quebec, Canada. Lancet Healthy Longev 2023, 4, e409–e420. [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, S.; Febriani, Y.; Velásquez García, H.A.; Zhang, G.; Tadrous, M.; Buchan, S.A.; Righolt, C.H.; Mahmud, S.M.; Janjua, N.Z.; Krajden, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccines Against Hospitalization and Death in Canada: A Multiprovincial, Test-Negative Design Study. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 640–648. [CrossRef]

- Orenstein, W.A.; Bernier, R.H.; Dondero, T.J.; Hinman, A.R.; Marks, J.S.; Bart, K.J.; Sirotkin, B. Field evaluation of vaccine efficacy. Bull World Health Organ 1985, 63, 1055–1068.

- Farrington, C.P. Estimation of Vaccine Effectiveness Using the Screening Method. Int J Epidemiol 1993, 22, 742–746. [CrossRef]

- Falchi, A.; Souty, C.; Grisoni, M.-L.; Mosnier, A.; Hanslik, T.; Daviaud, I.; Varesi, L.; Kerneis, S.; Carrat, F.; Blanchon, T. Field seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013, 9, 2453–2459. [CrossRef]

- Minodier, L.; Blanchon, T.; Souty, C.; Turbelin, C.; Leccia, F.; Varesi, L.; Falchi, A. Influenza vaccine effectiveness: best practice and current limitations of the screening method and their implications for the clinic. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014, 13, 1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- Vilcu, A.M.; Souty, C.; Enouf, V.; Capai, L.; Turbelin, C.; Masse, S.; Behillil, S.; Valette, M.; Guerrisi, C.; Rossignol, L.; et al. Estimation of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness using data collected in primary care in France: comparison of the test-negative design and the screening method. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018, 24, 431.e435–431.e412. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, M.; Andrews, N.; Davison, C.; Dugbazah, B.; Boateng, J.; Lunt, R.; Hardstaff, J.; Green, M.; Blomquist, P.; Turner, C.; et al. Effectiveness of one dose of MVA–BN smallpox vaccine against mpox in England using the case-coverage method: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, 828–835. [CrossRef]

- Horváth, J.K.; Ferenci, T.; Ferenczi, A.; Túri, G.; Röst, G.; Oroszi, B. Real-Time Monitoring of the Effectiveness of Six COVID-19 Vaccines against Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19 in Hungary in 2021 Using the Screening Method. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1824. [CrossRef]

- Moline, H.L.; Whitaker, M.; Deng, L.; Rhodes, J.C.; Milucky, J.; Pham, H.; Patel, K.; Anglin, O.; Reingold, A.; Chai, S.J.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing Hospitalization Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years—COVID-NET, 13 States, February–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1088–1093. [CrossRef]

- Herlihy, R.; Bamberg, W.; Burakoff, A.; Alden, N.; Severson, R.; Bush, E.; Kawasaki, B.; Berger, B.; Austin, E.; Shea, M.; et al. Rapid Increase in Circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant—Mesa County, Colorado, April–June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1084–1087. [CrossRef]

- Mazagatos, C.; Monge, S.; Olmedo, C.; Vega, L.; Gallego, P.; Martín-Merino, E.; Sierra, M.J.; Limia, A.; Larrauri, A. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 hospitalisations and deaths in elderly long-term care facility residents, Spain, weeks 53 2020 to 13 2021. Euro Surveill 2021, 26, 2100452. [CrossRef]

- Perumal, N.; Schönfeld, V.; Wichmann, O. Application of the screening method for estimating COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness using routine surveillance data: Germany’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, July 2021 to March 2023. Euro Surveill 2024, 29, 2300329. [CrossRef]

- Nittayasoot, N.; Thammawijaya, P.; Tharmaphornpilas, P.; Sansilapin, C.; Jiraphongsa, C.; Suphanchaimat, R. Rapid method through routine data to evaluate real-world vaccine effectiveness against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: lessons from Thailand. Health Res Policy Syst 2022, 20, 29. [CrossRef]

- Suah, J.A.-O.; Tok, P.S.K.; Ong, S.M.; Husin, M.; Tng, B.H.; Sivasampu, S.A.-O.; Thevananthan, T.; Appannan, M.R.; Muhamad Zin, F.; Mohd Zin, S.; et al. PICK-ing Malaysia's Epidemic Apart: Effectiveness of a Diverse COVID-19 Vaccine Portfolio. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1381. [CrossRef]

- Rashiti-Bytyçi, A.; White Johansson, E.; Kaçaniku-Gunga, P.; Danis, K.; Schoeps, A.; Dörre, A.; Fetaj, F.; Kalaveshi, A. Estimation of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against infections and severe outcomes using routine surveillance data in Kosovo, July—September 2021. PLOS One 2024, 19, e0305629. [CrossRef]

- van Werkhoven, C.H.; Valk, A.-W.; Smagge, B.; de Melker, H.E.; Knol, M.J.; Hahné, S.J.; van den Hof, S.; de Gier, B. Early COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness of XBB.1.5 vaccine against hospitalisation and admission to intensive care, the Netherlands, 9 October to 5 December 2023. Euro Surveill 2024, 29, 2300703. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness: Interim guidance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccine_effectiveness-measurement-2021.1 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidance on conducting vaccine effectiveness evaluations in the setting of new SARS-CoV-2 variants: Interim guidance, 22 July 2021. Addendum to Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness: Interim guidance. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccine_effectiveness-variants-2021.1 (accessed on 19 Sept 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness estimation using the screening method: Operational tool for countries. 2022. Available online: https://www.technet-21.org/media/com_resources/trl/7949/multi_upload/220707COVID-19_VE_Screening method_genericprotocol.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Flannery, B.; Andrews, N.; Feikin, D.; Patel, M.K. Commentary: Estimation of vaccine effectiveness using the screening method Int J Epidemiol, 2023, 52, 19–21. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. COVID-19 epidemiology update. 2022. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/archive/2022-10-21/testing-variants.html (accessed 31 Jul 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data Definitions for COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/reporting-vaccinations.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Wood, S.N. Thin Plate Regression Splines. J R Stat Soc, B: Stat Methodol 2003, 65, 95–114. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S. Origin, virological features, immune evasion and intervention of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 241. [CrossRef]

- Feikin, D.R.; Higdon, M.M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Andrews, N.; Araos, R.; Goldberg, Y.; Groome, M.J.; Huppert, A.; O'Brien, K.L.; Smith, P.G.; et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet 2022, 399, 924–944. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Interim analysis of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against Severe Acute Respiratory Infection due to laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 among individuals aged 65 years and older, ECDC multi-country study. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/interim-analysis-covid-19-vaccine-effectiveness-against-severe-acute-respiratory (accessed 15 July 2024).

- Cromer, D.; Steain, M.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T.E.; Khan, S.R.; Sasson, S.C.; Kent, S.J.; Khoury, D.S.; Davenport, M.P. Predicting vaccine effectiveness against severe COVID-19 over time and against variants: a meta-analysis. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1633. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Joyal-Desmarais, K.; Ribeiro, P.A.B.; Vieira, A.M.; Stojanovic, J.; Sanuade, C.; Yip, D.; Bacon, S.L. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. Lancet Respir Med 2023, 11, 439–452. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Interim analysis of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against Severe Acute Respiratory Infection due to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals aged 20 years and older – third update. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/interim-analysis-covid-19-vaccine-effectiveness-against-severe-acute-respiratory (accessed on 17 Jul 2024).

- Jacobsen, H.; Sitaras, I.; Katzmarzyk, M.; Cobos Jiménez, V.; Naughton, R.; Higdon, M.M.; Deloria Knoll, M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the factors affecting waning of post-vaccination neutralizing antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 159. [CrossRef]

- Tartof, S.Y.; Slezak, J.M.; Puzniak, L.; Hong, V.; Frankland, T.B.; Ackerson, B.K.; Xie, F.; Takhar, H.; Ogun, O.A.; Simmons, S.; et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA vaccine against a range of COVID-19 outcomes in a large health system in the USA: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2023, 11, 1089–1100. [CrossRef]

- Scobie, H.M.; Johnson, A.G.; Suthar, A.B.; Severson, R.; Alden, N.B.; Balter, S.; Bertolino, D.; Blythe, D.; Brady, S.; Cadwell, B.; et al. Monitoring Incidence of COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Vaccination Status—13 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1284–1290. [CrossRef]

- Health Canada (HC). Drug and vaccine authorizations for COVID-19: List of applications received. 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/covid19-industry/drugs-vaccines-treatments/authorization/applications.html (accessed on 13 Sep 2024).

- Adjobimey, T.; Meyer, J.; Sollberg, L.; Bawolt, M.; Berens, C.; Kovačević, P.; Trudić, A.; Parcina, M.; Hoerauf, A. Comparison of IgA, IgG, and Neutralizing Antibody Responses Following Immunization With Moderna, BioNTech, AstraZeneca, Sputnik-V, Johnson and Johnson, and Sinopharm's COVID-19 Vaccines. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 917905. [CrossRef]

- Atmar, R.L.; Lyke, K.E.; Deming, M.E.; Jackson, L.A.; Branche, A.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Rostad, C.A.; Martin, J.M.; Johnston, C.; Rupp, R.E.; et al. Homologous and Heterologous Covid-19 Booster Vaccinations. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1046–1057. [CrossRef]

- Breznik, J.A.; Rahim, A.; Kajaks, T.; Hagerman, M.; Bilaver, L.; Colwill, K.; Dayam, R.M.; Gingras, A.C.; Verschoor, C.P.; McElhaney, J.E.; et al. Protection from Omicron Infection in Residents of Nursing and Retirement Homes in Ontario, Canada. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023, 24, 753–758. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Rickeard, T.; Gallagher, E.; Gower, C.; Kall, M.; Groves, N.; O’Connell, A.-M.; et al. Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1532–1546. [CrossRef]

- Menni, C.; May, A.; Polidori, L.; Louca, P.; Wolf, J.; Capdevila, J.; Hu, C.; Ourselin, S.; Steves, C.J.; Valdes, A.M.; Spector, T.D. COVID-19 vaccine waning and effectiveness and side-effects of boosters: a prospective community study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1002–1010. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). COVID-19 vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide: For health professionals. 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-26-covid-19-vaccine.html (accessed on 16 Sep 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness: Interim guidance. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccine_effectiveness-measurement-2021.1 (accessed on 19 Sept 2023).

- Hahné, S.J.M.; Bollaerts, K.; Farrington, C.P. Vaccination programmes: Epidemiology, monitoring, evaluation, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781315166414.

| Characteristic | Overall | Unvaccinated | Primary series completed |

Primary series completed with one additional/ booster dose |

Primary series completed with two or more additional/ booster doses |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Totals | 103,822 | 100 | 24,023 | 23.1 | 22,686 | 21.9 | 33,926 | 32.7 | 23,187 | 22.3 |

| Severe COVID-19 outcome (n=103,822) | ||||||||||

| Hospitalized | 75,709 | 72.9 | 16,054 | 66.8 | 16,746 | 73.8 | 25,575 | 75.4 | 17,334 | 74.8 |

| Admitted to ICU | 8,452 | 8.2 | 2,969 | 12.4 | 1,947 | 8.6 | 2,250 | 6.6 | 1,286 | 5.5 |

| Death | 19,661 | 18.9 | 5,000 | 20.8 | 3,993 | 17.6 | 6,101 | 18 | 4,567 | 19.7 |

| Age group, years (n=103,822) | ||||||||||

| 50–59 | 10,469 | 10.1 | 4,215 | 17.5 | 3,133 | 13.8 | 2,451 | 7.2 | 670 | 2.9 |

| 60–69 | 18,653 | 18.0 | 5,842 | 24.3 | 5,045 | 22.2 | 5,350 | 15.8 | 2,416 | 10.4 |

| 70–79 | 27,979 | 26.9 | 6,336 | 26.4 | 6,124 | 27.0 | 9,253 | 27.3 | 6,266 | 27.0 |

| ≥ 80 | 46,721 | 45.0 | 7,630 | 31.8 | 8,384 | 37.0 | 16,872 | 49.7 | 13,835 | 59.7 |

| Gender (n=103,822) | ||||||||||

| Female | 47,377 | 45.6 | 11,005 | 45.8 | 10,206 | 45.0 | 15,506 | 45.7 | 10,660 | 46.0 |

| Male | 56,329 | 54.3 | 12,988 | 54.1 | 12,451 | 54.9 | 18,381 | 54.2 | 12,509 | 54.0 |

| Unknown/Other | 116 | 0.1 | 30 | 0.1 | 29 | 0.1 | 39 | 0.1 | 18 | 0.0 |

| Province/Territory (n=103,822) | ||||||||||

| Central | 42,149 | 40.6 | 10,258 | 42.7 | 8,738 | 38.5 | 12,000 | 35.4 | 11,153 | 48.1 |

| Eastern | 6,718 | 6.5 | 1,061 | 4.4 | 1,492 | 6.6 | 2,523 | 7.4 | 1,642 | 7.1 |

| Northern | 225 | 0.2 | 60 | 0.2 | 76 | 0.3 | 59 | 0.2 | 30 | 0.1 |

| Western | 54,730 | 52.7 | 12,644 | 52.6 | 12,380 | 54.6 | 19,344 | 57 | 10,362 | 44.7 |

| Circulating VOC (n=103,822) | ||||||||||

| Delta | 10,492 | 10.1 | 7,036 | 29.3 | 3,351 | 14.8 | 105 | 0.3 | – | – |

| Omicron B.1.1.529/BA.1/BA.2 | 43,411 | 41.8 | 9,777 | 40.7 | 13,164 | 58 | 19,095 | 56.3 | 1,375 | 5.9 |

| Omicron BA.4/BA.5/BQ |

32,916 | 31.7 | 4,606 | 19.2 | 4,411 | 19.4 | 11,205 | 33 | 12,694 | 54.8 |

| Recombinant XBB.1.5/EG.5 | 17,003 | 16.4 | 2,604 | 10.8 | 1,760 | 7.8 | 3,521 | 10.4 | 9,118 | 39.3 |

| Primary series |

Primary series with one additional/booster dose |

Primary series with two or more additional/booster doses |

||||||

| Delta | Omicron B.1.1.529/BA.1/BA.2 | Omicron BA.4/BA.5/BQ | Recombinant XBB.1.5/EG.5 | |||||

| aVE | 95% CI | aVE | 95% CI | aVE | 95% CI | aVE | 95% CI | |

| Hospitalization | ||||||||

| 50−59 years | 96.4 | 95.9– 96.9 | 74.9 | 71.8– 77.6 | 53.7 | 43.0– 62.3 | 61.0 | 51.9– 68.4 |

| 60−69 years | 95.2 | 94.7– 95.7 | 78.1 | 76.3– 79.8 | 68.9 | 64.5– 72.6 | 63.7 | 58.3– 68.3 |

| 70−79 years | 93.3 | 92.6– 93.9 | 74.3 | 72.3– 76.1 | 75.0 | 72.5– 77.3 | 64.3 | 60.6– 67.7 |

| ≥ 80 years | 84.5 | 82.8– 86.1 | 66.8 | 64.7– 68.8 | 69.6 | 67.4– 71.7 | 69.8 | 67.5– 72.0 |

| ICU admission/Death | ||||||||

| 50−59 years | 97.9 | 97.4– 98.4 | 83.7 | 80.1– 86.7 | 47.8 | 20.5– 65.7 | 75.8 | 61.1– 85.0 |

| 60−69 years | 96.5 | 95.9– 97.0 | 83.5 | 80.9– 85.7 | 73.6 | 66.4– 79.2 | 71.0 | 62.8– 77.4 |

| 70−79 years | 95.5 | 94.8– 96.1 | 80.4 | 77.8– 82.6 | 72.3 | 66.9– 76.9 | 71.9 | 66.1– 76.6 |

| ≥ 80 years | 87.1 | 85.4– 88.5 | 72.2 | 69.4– 74.8 | 68.9 | 65.2– 72.2 | 77.2 | 74.2– 79.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).