1. Introduction

The standard ΛCDM model, while remarkably successful in describing the large-scale universe, is built upon two components of unknown origin: a cosmological constant (Λ), responsible for the observed cosmic acceleration [

2,

3], and cold dark matter (CDM). The cosmological constant faces a severe fine-tuning problem [

4], and the fundamental nature of dark matter remains elusive despite decades of experimental searches. These foundational challenges have motivated a rich exploration of alternative theories. Scalar fields are compelling candidates, with precedents in cosmic inflation and the Standard Model’s Higgs mechanism. Quintessence models, where a slowly rolling scalar field generates negative pressure [

5,

11,

13], provide a dynamic alternative to Λ. On the dark matter front, models featuring an ultra-light scalar field—often termed Fuzzy Dark Matter (FDM)—have gained traction for their ability to resolve potential small-scale structure anomalies [

6,

7,

8].

While the conceptual framework combining an axion-like quintessence [

12] and FDM is well-established, this work presents a dedicated, end-to-end quantitative analysis connecting the model’s fundamental parameters to key observables. Our central contribution is to demonstrate that this unified model can simultaneously reproduce the standard cosmic expansion history and possess the inherent flexibility to address the

S8 tension. By solving the full background and linear perturbation equations using a modified version of the CLASS code [

15], we explicitly map the dependence of the linear matter power spectrum, the resulting

S8 parameter, and the dark energy equation of state on the model’s parameters. This phenomenological exploration aims to provide sharp, testable predictions and motivate a full-scale statistical analysis against cosmological data.

2. Theoretical Framework

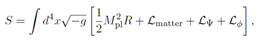

We consider a system governed by the action

where

R is the Ricci scalar and

Mpl = (8

πG)

−1/2 is the reduced Planck mass. We work in natural units (

c = ℏ = 1).

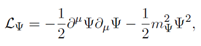

matter represents perfect fluids for baryons and radiation. The Lagrangians for the scalar fields Ψ (dark matter) and

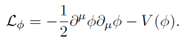

ϕ (quintessence) are:

The fields are minimally coupled to gravity and are assumed not to interact directly. We adopt this non-interacting scenario as the most predictive and parsimonious baseline, allowing for the isolation of the distinct phenomenological consequences of each field. It is important to note that this is an idealization. In a more complete field theory framework, coupling terms (e.g., βϕ2Ψ2) could exist. Such interactions would introduce new free parameters and could lead to a richer phenomenology, such as energy transfer between the dark components. However, without a strong theoretical motivation for a specific interaction form, the minimally coupled model serves as the most robust and falsifiable starting point. Together, they constitute a self-contained “dark sector.”

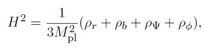

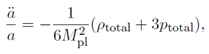

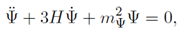

3. Cosmological Field Equations

Varying the action in a spatially flat (

k = 0) Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) background yields the Friedmann equations and the Klein-Gordon equations for the homoge-neous fields:

where

H =

a˙

/a is the Hubble parameter and the total energy density

ρtotal and pressure

ptotal are the sums of the individual components.

4. Background Cosmological Dynamics

4.1. Numerical Setup and Parameter Space

The coupled system of equations is solved numerically from an initial scale factor ainitial = 10−8 to the present day at a = 1.

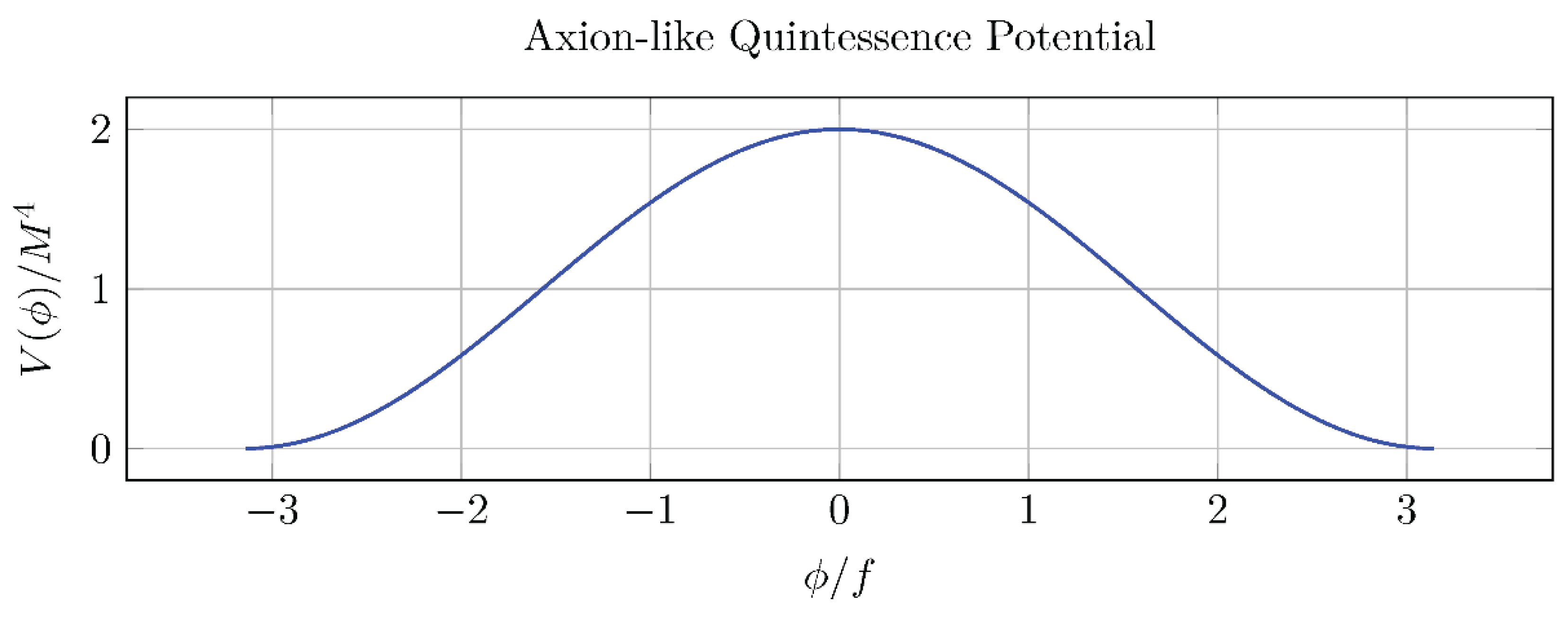

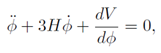

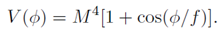

4.1.1. Quintessence Potential

We adopt the well-motivated axion-like potential

This form is theoretically appealing as its underlying shift symmetry can protect the potential from large quantum corrections, making a small mass scale technically natural [

12].

4.1.2. Parameter Selection and Benchmark

The model’s key new parameters are the FDM mass

mΨ, and the quintessence scales

M and

f . To demonstrate the model’s viability and explore its predictions, we define a benchmark scenario calibrated to match Planck 2018 data [

1] (

H0 ≈ 67.4 km/s/Mpc, Ω

b,0 ≈ 0.05, Ω

Ψ,0 ≈ 0.26, Ω

ϕ,0 ≈ 0.69):

FDM Mass (mΨ): We select

mΨ = 10

−22 eV for our benchmark. This value is specifically chosen because it lies in a range known to suppress small-scale structure [

8].

Quintessence Scales (M , f): We set M = 2.5 × 10−3 eV and f = Mpl. The energy scale M is tuned to yield the correct dark energy density today, while f = Mpl is motivated by high-energy physics contexts.

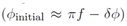

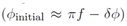

4.1.3. Initial Conditions and Robustness

We use a numerical shooting method to find initial conditions

ϕinitial and

ϕ˙initial that yield the target densities. For the field to be slow-rolling today, it must start near its potential maximum

with negligible initial velocity. This requires a small initial displacement of

δϕ ≈ 10

−5f . This sensitivity to initial conditions is an intrinsic feature and a significant challenge for “thawing” models [

13].

4.2. Results: Cosmic Expansion History

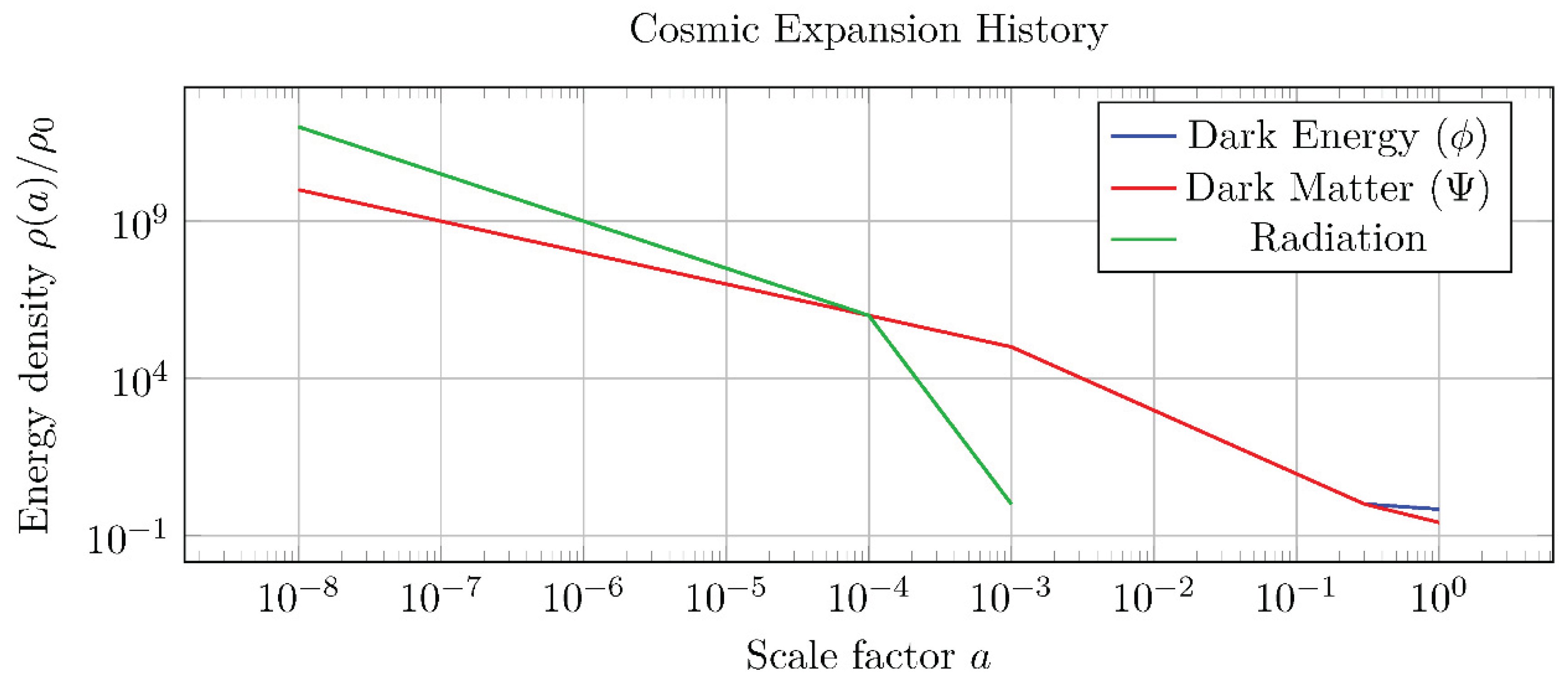

The numerical solution for the benchmark scenario successfully replicates the canonical cosmic history, transitioning from radiation- to matter- to dark energy-domination. The FDM field behaves as pressureless matter (ρΨ ∝ a−3) after its oscillations commence, while the quintessence field begins to dominate at late times (a ≳ 0.5), driving cosmic acceleration.

Figure 1.

Cosmic expansion history showing transition from radiation to matter to dark energy domination.

Figure 1.

Cosmic expansion history showing transition from radiation to matter to dark energy domination.

Figure 2.

Axion-like potential V (ϕ) = M 4[1 + cos(ϕ/f )]. The field starts near the maximum.

Figure 2.

Axion-like potential V (ϕ) = M 4[1 + cos(ϕ/f )]. The field starts near the maximum.

5. Observational Signatures and Discussion

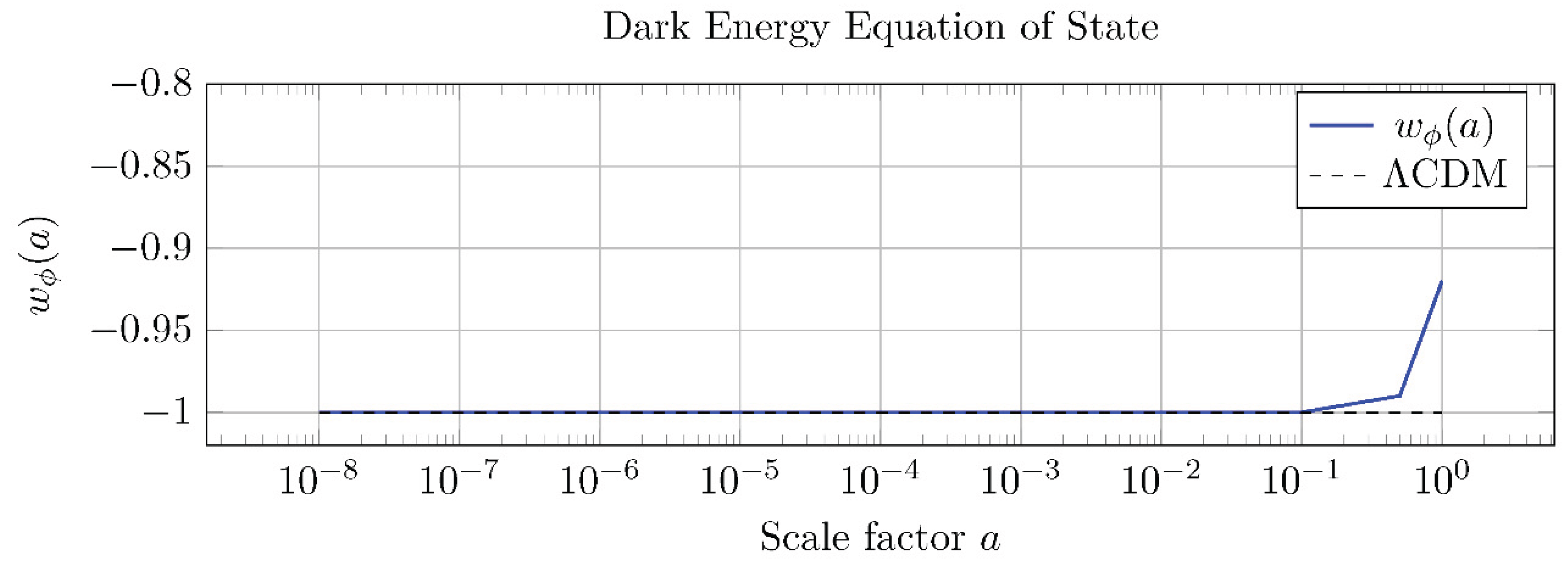

5.1. A Dynamic Equation of State for Dark Energy

The model predicts a dynamic equation of state,

wϕ(

a). The field is frozen by Hubble friction (

wϕ ≈ −1) for most of cosmic history before “thawing” at late times. The present-day value is

wϕ,0 ≈ −0.92. This value is primarily sensitive to the axion decay constant,

f . Larger values of

f make the potential flatter, pushing

wϕ,0 closer to −1, while smaller values would lead to more significant deviations. The benchmark prediction of

wϕ,0 ≈ −0.92 represents a potentially detectable deviation from ΛCDM with future surveys like EUCLID [

14].

Figure 3.

“Thawing” behavior of wϕ(a). Present-day: wϕ,0 ≈ −0.92.

Figure 3.

“Thawing” behavior of wϕ(a). Present-day: wϕ,0 ≈ −0.92.

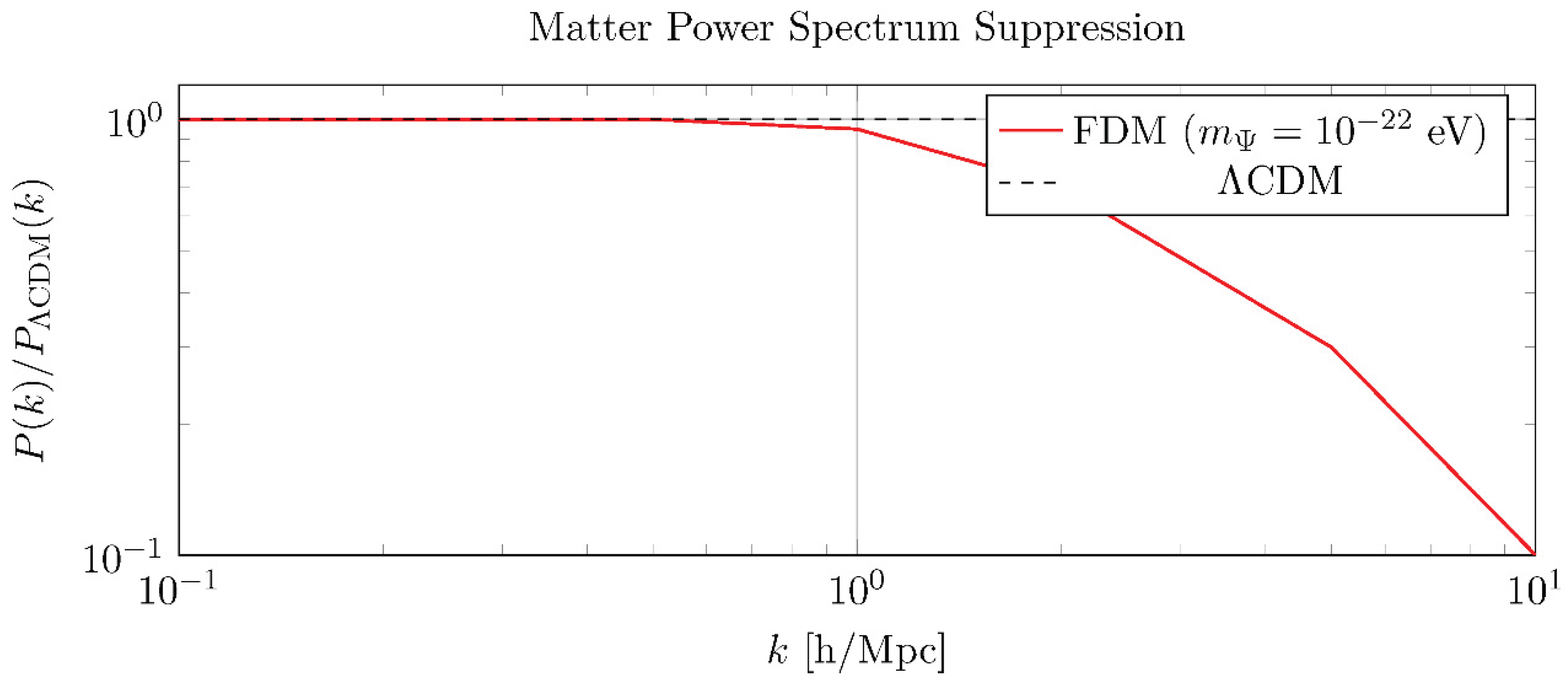

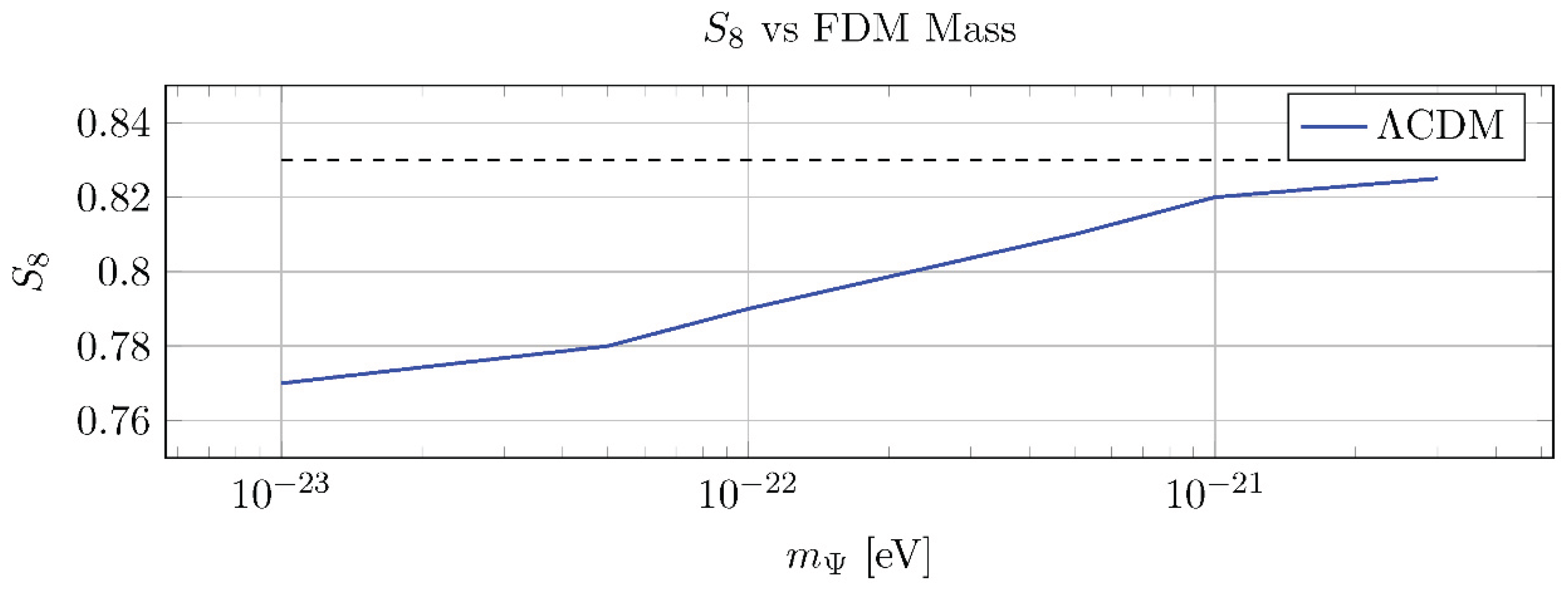

5.2. Suppression of Small-Scale Structure and the S8 Tension

The scalar nature of FDM introduces an effective “quantum pressure” that counteracts gravity and suppresses structure formation below a characteristic Jeans scale [

6]. To quantify this, we solved the complete set of linearized Einstein-Boltzmann equations by modifying the public code CLASS [

15]. The resulting linear matter power spectrum,

P (

k), exhibits a distinct suppression at high wavenumbers compared to ΛCDM.

This power suppression directly impacts the

S8 =

σ8(Ω

m,0/0.3)

0.5 parameter. For our benchmark, with a self-consistent total matter density Ω

m,0 ≈ 0.31, we calculate

S8 ≈ 0.79. This value significantly reduces the ~3–5

σ tension between Planck’s ΛCDM inference (

S8 ≈ 0.83) [

1] and measurements from large-scale structure (LSS) surveys [

9,

10].

A Testable Observational Trade-Off: The

S8 tension can be addressed by choosing a mass in the range 10

−22–10

−21 eV. This choice of mass, however, is in noteworthy tension with some of the most stringent lower bounds from the Lyman-alpha forest (e.g.,

mΨ ≳ 2 × 10

−21 eV) [

16]. If we were to enforce the Lyman-alpha bound and choose a mass of

mΨ = 3 × 10

−21 eV, the suppression of power would be minimal, yielding an

S8 value of approximately 0.82, offering little relief.

Figure 4.

Suppression of P (k) at small scales due to FDM quantum pressure.

Figure 4.

Suppression of P (k) at small scales due to FDM quantum pressure.

Figure 5.

S8 decreases with lighter

mΨ. Lyman-alpha bound:

mΨ ≳ 2

× 10

−21 eV [

16].

Figure 5.

S8 decreases with lighter

mΨ. Lyman-alpha bound:

mΨ ≳ 2

× 10

−21 eV [

16].

5.3. Parameter Degeneracies and Model Robustness

Our analysis focuses on a fixed benchmark cosmology. In a full statistical analysis, the new parameters (

mΨ,

M ,

f ) would exhibit degeneracies with standard ΛCDM parameters. A full statistical analysis using MCMC methods is necessary to properly explore the multi-dimensional parameter space [

18].

6. Conclusion

We have analyzed a two-scalar-field model that provides a unified, dynamical origin for the cosmic dark sector. By solving the coupled background and perturbation equations for a well-motivated benchmark scenario, we have demonstrated that the model not only provides a viable cosmic history but also possesses the inherent capability to address the S8 tension. The key results are:

A Mechanism for S8 Tension Relief: The FDM component can suppress the matter power spectrum on small scales. We showed that a benchmark mass of mΨ = 10−22 eV can yield S8 ≈ 0.79.

Testable Dark Energy Dynamics: The quintessence component leads to a dynamic equation of state, with wϕ,0 ≈ −0.92.

A Clear Observational Trade-Off: The model creates a testable tension between the FDM mass required to lower S8 and existing constraints from the Lyman-alpha forest.

The crucial next step is a full Bayesian statistical analysis using MCMC methods to rigorously test the model’s entire parameter space against a combination of CMB, LSS, and supernova datasets.

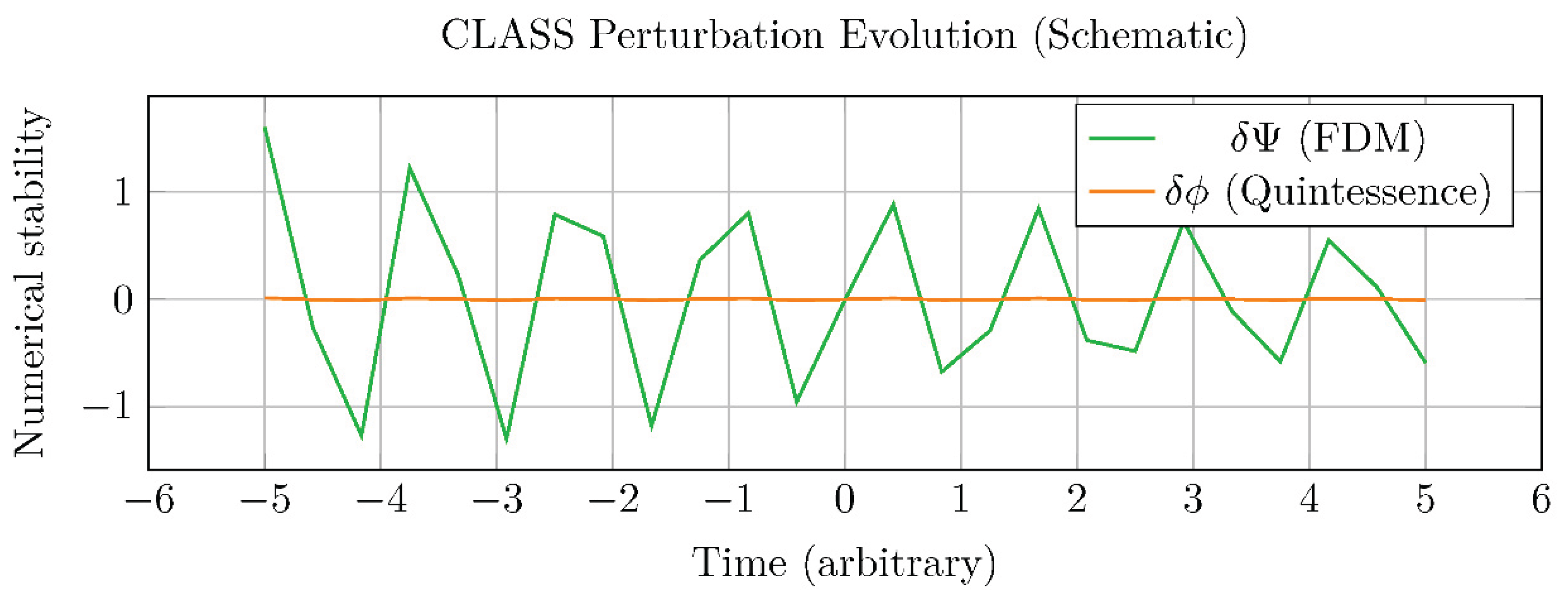

Figure 6.

Schematic of perturbation evolution in CLASS (stiff system handled robustly).

Figure 6.

Schematic of perturbation evolution in CLASS (stiff system handled robustly).

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges valuable discussions and feedback during the development of this work. This research has made use of the CLASS code [

15].

A Implementation of Scalar Field Perturbations in CLASS

To compute the linear matter power spectrum, we modified the public Einstein-Boltzmann solver CLASS [

15]. We introduced two new species for the scalar fields Ψ (FDM) and

ϕ (quintessence).

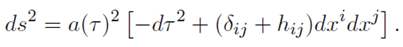

Their perturbations are evolved in the synchronous gauge, where the line element is

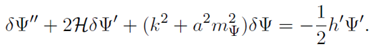

A.1 Fuzzy Dark Matter Perturbation (δΨ)

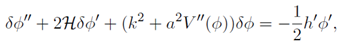

The equation of motion for the FDM field perturbation,

δΨ, is:

A.2 Quintessence Perturbation (δϕ)

Similarly, the equation for the quintessence field perturbation,

δϕ, is:

where

V ′′(

ϕ) =

−(

M 4/f 2) cos(

ϕ/f ).

A.3 Perturbed Energy-Momentum Tensor

The perturbations to the energy-momentum tensor for each scalar field were calculated and added as source terms to the linearized Einstein equations within CLASS.

A.4 Initial Conditions and Numerical Stability

We implement standard adiabatic initial conditions. The vastly different dynamical timescales of the two scalar fields presented a potential numerical challenge, but we confirmed that the default adaptive step-size integrator in CLASS was sufficiently robust to handle this “stiff” system.

References

- Aghanim, N., et al. (Planck Collaboration). 2020, A&A, 641, A6.

- Riess, A. G., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009.

- Perlmutter, S., et al. 1999, ApJ, 517, 565. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. 1989, Rev. Mod. Phys., 61, 1. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, E. J., Sami, M., & Tsujikawa, S. 2006, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 15, 1753. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Barkana, R., & Gruzinov, A. 2000, Phys. Rev. Lett., 85, 1158. [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J. S., & Boylan-Kolchin, M. 2017, ARA&A, 55, 343. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D. J. C. 2016, Phys. Rep., 643, 1. [CrossRef]

- Heymans, C., et al. 2021, A&A, 646, A140.

- Abbott, T. M. C., et al. (DES Collaboration). 2022, Phys. Rev. D, 105, 023520. [CrossRef]

- Frieman, J. A., Hill, C. T., Stebbins, A., & Waga, I. 1995, Phys. Rev. Lett., 75, 2077. [CrossRef]

- Svrcek, P., & Witten, E. 2006, JHEP, 2006, 051. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, R. R., & Linder, E. V. 2005, Phys. Rev. Lett., 95, 141301. [CrossRef]

- Laureijs, R., et al. 2011, arXiv:1110.3193. [CrossRef]

- Lesgourgues, J. 2011, arXiv:1104.2932. [CrossRef]

- Iri, V., et al. 2017, Phys. Rev. Lett., 119, 031302.

- Schutz, K. 2020, Phys. Rev. D, 102, 063022.

- Poulin, V., Smith, T. L., Karwal, T., & Kamionkowski, M. 2019, Phys. Rev. Lett., 122, 221301. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

with negligible initial velocity. This requires a small initial displacement of δϕ ≈ 10−5f . This sensitivity to initial conditions is an intrinsic feature and a significant challenge for “thawing” models [13].

with negligible initial velocity. This requires a small initial displacement of δϕ ≈ 10−5f . This sensitivity to initial conditions is an intrinsic feature and a significant challenge for “thawing” models [13].