1. Introduction

Several countries engage in collecting data about physical development in children and youth [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Studies in this field from the pre-big-data era describe problems arising from the scarcity of data needed to conduct such research [

5,

6]. Nowadays, the problem is still the same, at least with data from high-quality and representative surveys. These data are sensitive, and public sharing is sometimes not encouraged. Researchers are generally entitled to obtaining such data, but problems with technical incompatibility may hinder their usage.

To overcome these obstacles, we propose a solution initially developed in the manufacturing industry where various organizations and people decided to organize a regime of sharing their data, which would guarantee the rights of all involved entities, called Sovereign Data Sharing [

7]. It has since been promoted by European institutions all over Europe and worldwide. It has been implemented in other branches of human activity, such as transportation, logistics, mobility, tourism, etc., and is intended to be used among different branches. It is embodied in Data Spaces [

8,

9]. This approach breaks “data silos” where data are constrained inside a single organization or a single branch. On the other hand, many existing data exchanges operate bilaterally, which, however, do not scale well, so novel approaches to multilateral associations of stakeholders are needed [

10]. The technical, organizational, legal, and ethical aspects of data sharing are being addressed to overcome obstacles to data sharing [

11]. Though the final goal is to have a single European Data Space, current steps are still made at the sectoral level. The ACDSi data could, based on the fact that they describe the developmental status of young people and are therefore personal data, be shared inside the European Health Data Space [

12]. There, they would benefit of the same governance, protection and support as other, predominantly medical data.

In this work, we are interested in the technical aspect, which is called semantic interoperability. To achieve this goal, all the needed standards and technologies already exist. Therefore, the novelty of the Data Spaces approach is in the combination of means necessary to solve all the technical problems that may hinder efficient data sharing. The adoption process (e.g. selection of standards, protocols and tools) runs in parallel on the standardization level in formal bodies (e.g. in standardization institutes, like European Telecommunications Standardization Institute (ETSI)) and on the informal level, which means intense inclusion and well-steered collaboration of scientific, developer, and user communities. The output of this process are specifications of the necessary tools and procedures. The reference implementations of the tools are the software components, which cover the needs that have been identified in the specification phase and include at least the minimal required capabilities. They are being developed under open-source licenses to lower the barrier to acquiring the technologies. These implementations are often mature enough to be used in production, at least in less demanding environments (e.g. participants with small quantities of data). If needed, they can be adapted to the specific needs due to the openness of their source code.

To leverage the potential of the data, Europe has initiated a process of enabling participants to share their data in a trustworthy manner. This will encourage those entities in possession of the data (data providers), who are hesitant to share it due to concerns of giving away trade secrets or other sensitive information, to offer the data for the common good, benefitting them on one side and the consumers of the data on the other side and also the society as a whole. Data providers must know that data will be used in accordance to the conditions they set in advance and that all the relevant regulations will be respected. Data consumers on the other side must be assured that the data came from valid sources and its contents are trustworthy. This is also needed in our use case and in public health data in general. The data in these cases come from physical persons and are protected by important European and national legislation that both data providers and data consumers must abide by.

The trust is assured by providing common guidelines and trustworthy technical means for executing the data exchange. These guidelines and technical means will allow for automatic compliance with the conditions of data usage proscribed by the data provider without manual intervention. Such tools need to be certified as compliant with the Data Spaces specifications. Recently, two major European associations have undertaken to define the necessary specifications, and these will be briefly presented in this work. The first is the International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) [

13] specification with the IDS Rulebook [

14] and IDS Reference Architecture Model (IDS RAM) [

15,

16]. The second is the FIWARE [

17] specification with the Generic Enablers for Data Spaces, combined with iSHARE security components [

18,

19]. These definitions currently have limitations as they were meant to demonstrate participants’ ability, initially in limited numbers, to share data. They have been later included in a definition process of the GAIA-X initiative [

20], which currently works to adapt them into a broader infrastructure suitable for large-scale cloud deployments. Both associations are now, along with the GAIA-X initiative and the Big Data Value Association (BDVA) [

21], founding members of the Data Spaces Business Alliance (DSBA), which steers these efforts further in a more strictly organized manner [

22].

We are presenting two prevailing architectures of the data-sharing technologies developed by two associations: IDSA [

8] and FIWARE [

17]. The central component of the former is called the Connector, and the one of the latter is called the Context Broker. They offer similar features, but each may be more suitable for some use cases than others. In this work, we use Context Broker to verify the generated artifacts, as will be presented in later sections.

Two prevailing architectures of the data-sharing technologies are developed by two associations: IDSA [

8] and FIWARE [

17]. The central component of the former is called the Connector, and the one of the latter is called the Context Broker. They offer similar features, but each may be more suitable for some use cases than others. In this work, we use Context Broker to verify the generated artifacts, as will be presented in later sections.

Both architectures extend the access control mechanisms from the internal information systems inside organizations onto the World Wide Web scale. Data providers can define usage policies (simple or complex rules) that data consumers must follow. If agreed upon by both parties, the technologies involved in these architectures will enforce these policies on data usage without human intervention. Usage policies consist of usual access rights and more complex use cases (e.g., time limiting of the use, an obligation to delete data after use, logging or notifying about data use, etc.) [

23]. Some policies are, at present, only executable on a contractual and juridical level as technical enforcement is not mature enough, or a combination of both measures is needed.

The technical enforcement of the policies is implemented as the capacity of the IDS Connector component to run a Data App – a certified application that can perform predefined operations on the data received from the Data Provider – inside the Data Consumer’s IDS Connector. Using this technique, it is possible to guarantee that unprocessed data never leaves the internal storage of the IDS Connector.

It has been shown that the Context Broker could play the role of a Data App in the data exchange managed by IDS Connectors. IDS Connectors on both sides of the data exchange would provide the necessary protection, whereas Context Broker would guarantee the semantic interoperability capabilities [

18]. The original approach was later completed with a more scalable execution environment and additional security components [

24]. A prototype combining IDS-compliant and FIWARE-provided components in the data exchange infrastructure was developed by the Engineering Ingegneria Informatica [

25] and demonstrated in a Horizon 2020 project, PLATOON [

26].

However, despite the protection of the IDS Connector, the data may still be vulnerable to so-called “Side Channel Attacks,” where the attacker can infer the protected data contents from specially crafted interactions with the computer components. A possible solution to this problem is the Trusted Hardware Enclave inside the main processing unit that only the predefined process could access, in our case, the IDS Connector. However, it has been shown that even this solution can be exploited by side-channel attacks. So, a cryptographic method called Oblivious Computing has been proposed to overcome this potential data exposure [

27,

28].

Enhancing the basic flow of data from the Data Provider to one or more Data Consumers, further ways of data exploitation are envisioned: Federated Learning, Secure Multi-Party Computation, and privacy-preserving techniques (homomorphic encryption, etc.) [

29]. These techniques build upon the principle that the data does not need to leave the Data Provider to be analyzed. Instead, if there are multiple Data Providers, the algorithm is trained on each Data Provider’s part of data inside their infrastructure and then adjusted from learning on data from other Data Providers. Some algorithms can be decoupled to perform selected steps (preferably the first and the last) inside the Data Provider infrastructure. This approach is called Split Learning. According to the IDS architecture, these algorithms, or part of them, are built as Data Apps [

30].

Data sharing principles of Data Spaces can also be implemented in scenarios where no specific data usage limitation is needed, like in publishing open data. Technologies otherwise used to protect and enforce the data usage policies can still be used. Still, the only policy enforced would be the simplest one: that everybody can access the data without limitations. This way, the security measures built into the technological components can protect the Data Space from malicious data alteration or deletion. Other infrastructure features like federated computing and Data Apps in general can also be utilized.

Currently, the Data Spaces components are in the early development stages and typically require expert knowledge to install and configure properly. To attract a wider audience to participate in data exchange through Data Spaces (e.g., Small and Medium Enterprises), the usability of these tools will need to be improved so that installation and configuration would only be as demanding as in an ordinary office application.

Besides the technologies that enable machines to communicate and transport the data between them, it is necessary for them and for people to have a common understanding of the data that is being shared. To achieve this, data models are being developed, which organize the data about real world entities, encompassing as many facets of the real world entity as possible or necessary. Like the software used in the data-sharing process, the data models are published openly.

A broader and more conceptual notion than data models are ontologies that are used to describe knowledge in terms of concepts and relations among them and are often defined inside a particular field of knowledge. Interesting efforts have been made to enable interoperability at the ontology level by formalizing the ontology-building process with a common set of principles and basic or reference ontologies as foundations. In the biosciences domain, the Open Biological and Biomedical Ontologies (OBO) Foundry has been developed [

31]. Another known foundation is Dublin Core [

32].

In the World Wide Web domain, the Semantic Web emerged [

33]. It aims to specify additional notation elements in HTML for the machines to infer the semantics of data and their relationships (linked data) from the web pages themselves. Several well-known components have been developed that support this concept. The eXtensible Markup Language (XML) was defined earlier and allows to define custom tags that can supplement additional meaning to the document contents [

34].

Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a model used to represent the contents by encoding it into statement-like structures (subject-predicate-object) called triplets [

35]. This allows for any software to discern a meaning regardless of the particular data model that the software is based on. An ontology can be expressed as a set of statements, in this case RDF triples, that describe a given subject and relationships among its inner concepts. RDF can represent a graph structure where subjects and objects represent nodes in a graph and the predicates represent directed links among nodes. Such structure is called RDF graph. RDF Schema (RDFS) is an extension to RDF for describing classes and their relations and serves as a language to express data models [

36]. Web Ontology Language (OWL) is a language for defining and instantiating Web ontologies and is more comprehensive than RDFS in expressing relations among classes and their other characteristics [

37]. SPARQL is a query language for searching through the semantic web or databases containing triples [

38]. Besides XML as the initial RDF serialization format, the JavaScript Object Notation-Linked Data (JSON-LD) [

39] serialization has been developed, providing a more concise serialization of objects and their relationships compared to XML.

In order to facilitate finding particular data on the World Wide Web, special websites emerged that list available data and the associated metadata, called data catalogs. Several tools exist to define data catalogs. CKAN is a tool used to publish open-access data, predominantly by public institutions [

40]. It allows for uploading or linking to datasets, which can then be consumed by downloading the file from the CKAN server or from the provided link. Using the DataStore extension, uploading the dataset to a relational database connected to the CKAN server is also possible. This extension allows the user to define a data dictionary describing individual data elements (e.g., columns in a table), which could be regarded as a data model. The data dictionary is also the control mechanism because new data can only be ingested if compliant with this dictionary. This extension is not mandatory, however. The Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT) is an RDF vocabulary designed to facilitate interoperability between data catalogs published on the Web [

41]. It provides RDF classes and properties to allow datasets and data services to be described and included in a catalog. However, it defines the metadata to the level of datasets only; the individual data points (features) are not covered.

In the Telecommunications and Internet of Things domain, the research in context management (automatic alignment of data about the same subject from different sources) led to the standardization of Next Generation Systems Interface (NGSI) by Open Mobile Alliance and, in newer versions (extended with linked data capability, hence NGSI-LD), by ETSI and its Context Information Management (CIM) committee [

42]. The FIWARE Foundation led the development of NGSI-LD under the European Commission’s support. It is now used in several projects and specifications (Connected Europe Facility, Living-in.eu project, IoT Big Data Framework Architecture by GSM Association, etc.). It has been proposed for use in the GAIA-X initiative [

43]. The NGSI-LD API uses JSON-LD as a main serialization format, so the NGSI-LD data payloads are serialized as JSON-LD [

44].

The ETSI standard GS CIM 006 defines NGSI-LD information model as a graph similar to an RDF graph, with a practical difference that in NGSI-LD, not only the entities (vertices) but also the relationships (edges, arcs) can have properties, which means that an RDF graph can be translated to an NGSI-LD one.

The use of data models differs in presented technologies. In the IDSA case, the data model is optional at the time of data provisioning, and a special component to host the model (called Vocabulary Provider) is needed [

16]. In the FIWARE case, the data model is mandatory and has to be known in advance. The central component (Context Broker) needs the data model in advance, before the data contents are provided, so the Context Broker ensures that the data provided conform to the data model. Both the data and the model are structured according to the NGSI-LD standard and they are hosted in the Context Broker, so no additional component is needed [

45]. In both the IDSA and the FIWARE cases, the model has to be known at the time of data consumption.

To better support the use of NGSI standard, FIWARE, and TM Forum have established, together with Indian Urban Data Exchange (IUDX) and Open and Agile Smart Cities (OASC), the Smart Data Models initiative [

46], which aims to engage the community to develop and publish data models emanating from real use cases of data exchange. The process is agile and open and based on established standards.

Loebe [

47] (Section 2.4) proposes a fundamental set of elements sufficient to express any ontology, consisting of categories and relations. NGSI-LD defines a similar concept framework where entities (acting as categories) have elementary properties describing them and properties describing relations with other entities.

Data models are a constituent part of Digital Twins (DT), which are comprehensive digital models of (physical or intangible) real-world objects. They add the real-time data to the data model, and so are an accurate digital representation of their physical or otherwise existing counterpart – the entity they describe. They were initially developed in the manufacturing industry to represent the products and the whole manufacturing processes [

48]. The DT comprises both the real-world object’s structure and the data describing its state in the real or near-real time. This allows for an analysis of the real-world object’s current state and simulation and prediction of its future state. ETSI advocates the use of NGSI-LD property graphs as holistic Digital Twins [

49]. They propose several use cases where the NGSI-LD specification is mature enough for use in DTs and provide recommendations for further NGSI-LD specification evolution. Recent research is demonstrating a feasibility of building complex DTs using the NGSI-LD specification [

50].

In the recent years, a major breakthrough in the field of Artificial Intelligence was achieved with the development of Large Language Models (LLM) that are very successful at understanding and following instructions, perform various linguistic tasks (translation, summarization, paraphrasing, etc.), assisting developers at programming and many others. However, they struggle at performing complex reasoning tasks and in continuous improvement of their knowledge, among other problems. The current research proposes agentic systems to alleviate these problems. Among others, an Ontology Matching agentic system was proposed [

51]. An important type of agents are memory agents that can manage the knowledge retained from the history of performed tasks and also the information obtained during these tasks from outside of these systems, called external knowledge [

52]. An important source of external knowledge can be DT [

53] and we are confident that also information about our use case could be exploited in such agentic systems as an external knowledge through the data models that we propose.

The main goal of this work is to present an automatic creation of a NGSI-LD data model from an existing RDF ontology. As no tool capable of authoring a NGSI-LD data model from scratch is known to us and a manual process is always error prone, we decided to use a tool (Protégé) to create a RDF ontology and then perform an automatic generation of a NGSI-LD data model.

There exists already a tool, similar to our proposal: SDMX to JSON-LD Parser [

54]. However, it is only capable of transforming the data models compliant with STAT-DCAT-AP 1.0.1 specification. Consequently, it is not applicable to our case. Our approach also makes use of the SPARQL Property Path queries, whereas their tool uses different algorithm.

In the Materials and Methods section, we describe the necessary tools used in our work and the algorithm structure that has been developed. In the Results section, we demonstrate the products developed and the final result of published fictitious data. In the Discussion section, we present the current study’s limitations and envision possible directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

The set of tools used in this work consists of commonly used software systems and applications. The source ontology was developed in the Protégé tool, version 5.6.3 [

55]. Next, the translation tool was developed in Python, version 3.10, using the package rdflib, version 7.0.0, and relied on the package pysmartdatamodels

1, version 0.6.3 [

56]. After the NGSI-LD data model was constructed, it was tested on the Context Broker that FIWARE recommends as a reference implementation, which is Orion-LD, version 1.4.0 [

57].

2.1. Data Model for ACDSi Measurements

We propose a data model concerning the subset of the ACDSi data, containing the features assessed as important in the study [

58]. These features are part of the EUROFIT [

59] and SLOfit [

60] test batteries.

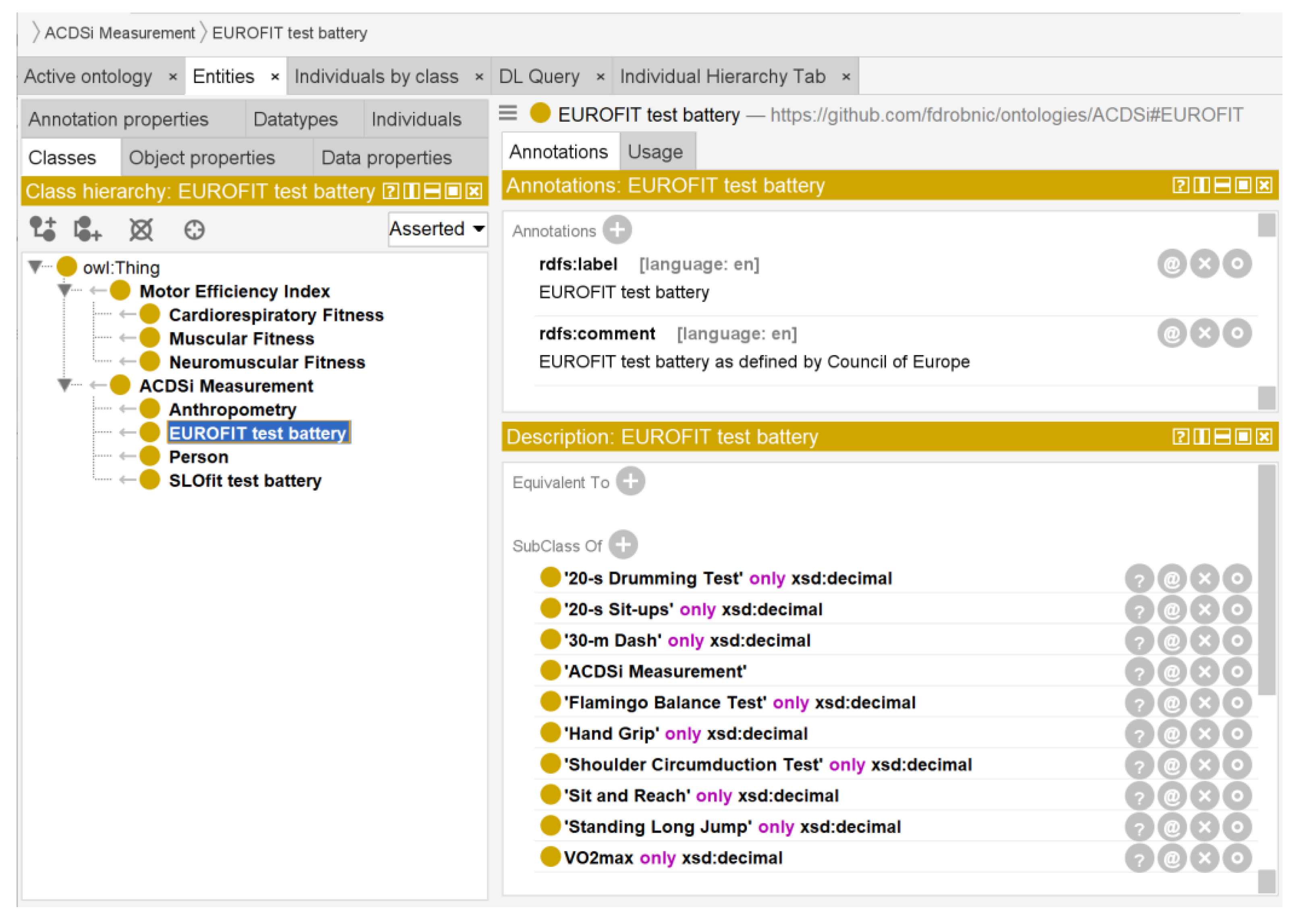

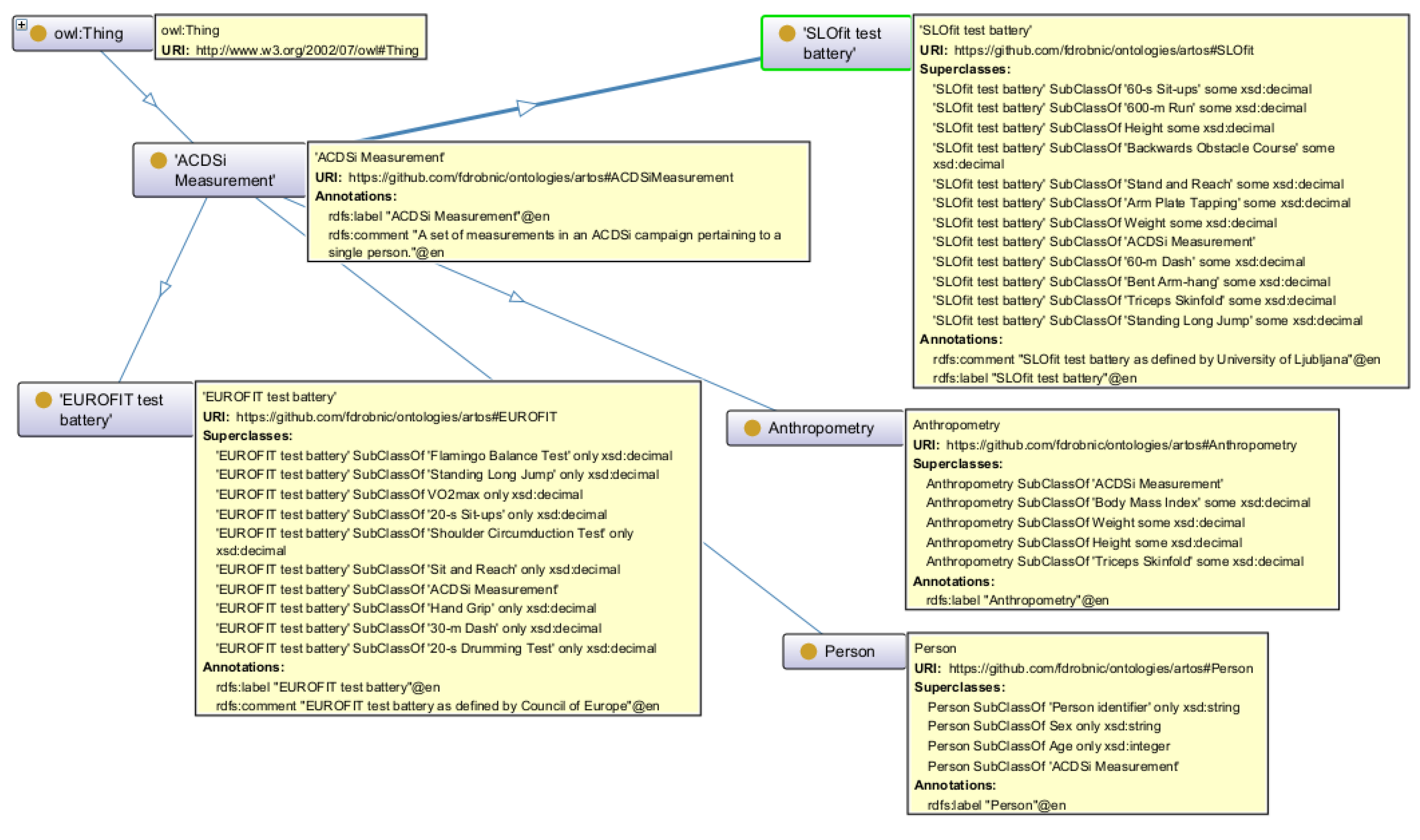

The ontology describing the ACDSi data was conceived using the Protégé tool [

55]. It consists of one root class named ACDSiMeasurement and two subordinate classes, EUROFIT and SLOfit, each containing measurements from their respective test batteries. The overall structure was conceived similarly to the Smart Applications REFerence ontology (SAREF) ontologies standardized by ETSI [

61]. All the numerical data properties (features) were constrained to xsd:decimal datatype, except for the Age, which is assumed to be xsd:integer.

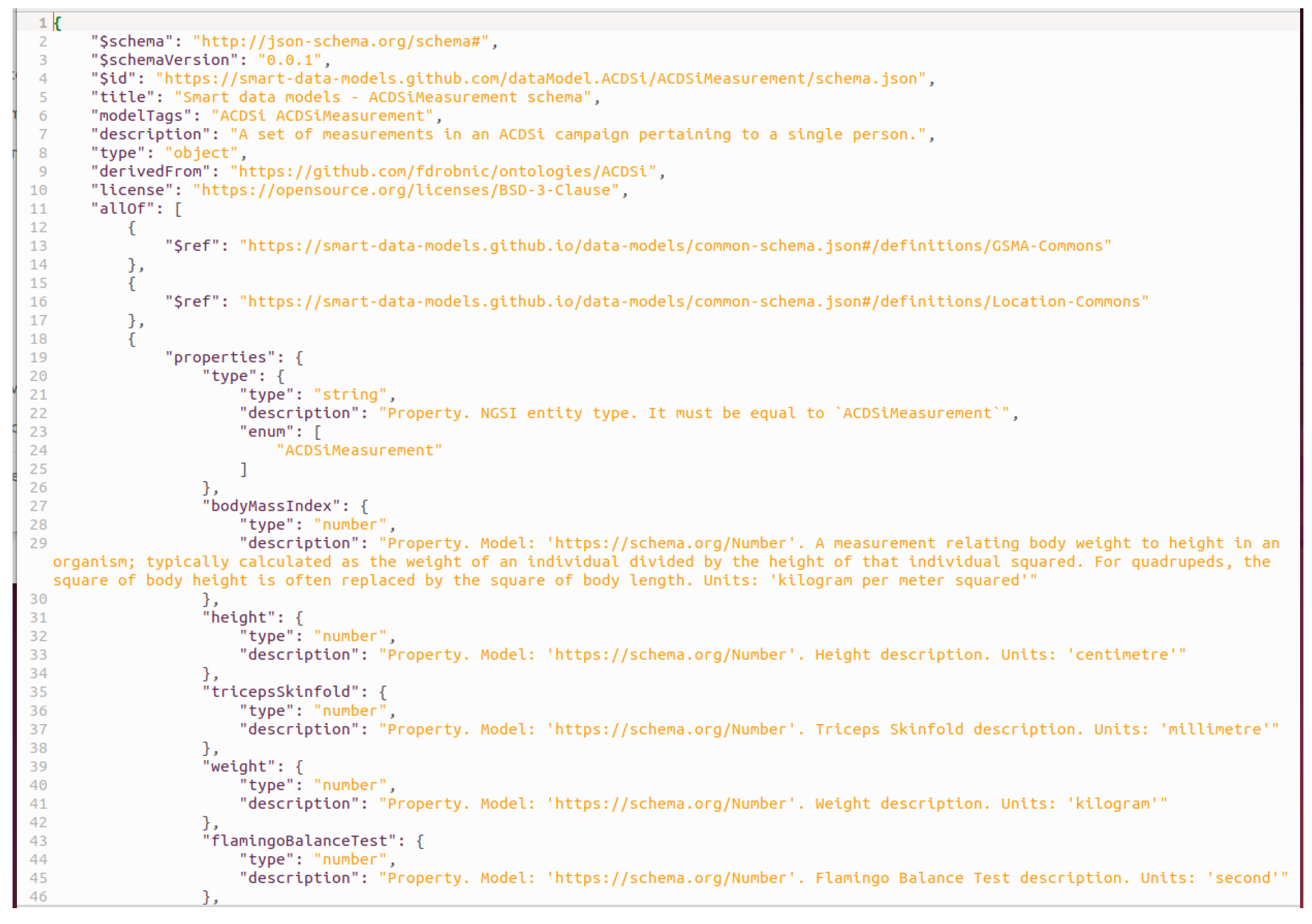

Next, we developed a tool that uses information from this ontology and creates a NGSI-LD data model in a format suitable for publication on the Smart Data Models repository. The publication process as described on the Smart Data Models web page [

46] requires submitting five documents, from which three can be generated from the ontology (schema.json, notes_context.jsonld, and example-normalized.jsonld), and the rest are filled manually. As the ETSI standard GS CIM 006 explains, the NGSI-LD information model follows the graph structure of RDF, so it is feasible to translate the RDF graph to the NGSI-LD graph.

Initially, the RDF ontology was read into a set of triples using the rdflib package. The triples consist of three elements, subject, predicate, and object, in that order. The set of triples can be queried against using the rdflib triples() function with a triple pattern as an argument. In the pattern, any triple element can be unconstrained using the keyword “None”, fixed with a constant, or, for the predicate, constrained with a path pattern equivalent to the SPARQL 1.1 Property path operators [

62].

The algorithm accepts an identification of the root class from the RDF ontology for which the data model will be generated as a parameter of type Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI). This class constitutes the entity in the NGSI-LD terms. In our case, the root class is acdsi:ACDSiMeasurement and is defined as follows (in the Turtle syntax):

acdsi:ACDSiMeasurement rdf:type owl:Class ;

rdfs:comment “A set of measurements in an ACDSi campaign pertaining to a single person.”@en ;

rdfs:label “ACDSi Measurement”@en .

Each line represents a triple and consists of three elements: subject, predicate, and object. Lines ending with semicolon are continued in the next line and all the following lines share the same subject with the first line, up to the line that ends with a dot. The first line declares that acdsi:ACDSiMeasurement is a class, the second line defines a class description and the third line defines a label, both in English language.

The first step in the translation process is to find all the data properties of the root class (these are defined on the “Data properties” tab in the Protégé editor). They are defined on the subordinate classes to the root class and are included in the NGSI-LD data model as properties of the entity. For example, acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest is one of the data properties and is defined as follows:

acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest rdf:type owl:DatatypeProperty ;

rdfs:range xsd:decimal ;

rdfs:comment “Flamingo Balance Test description. Units: ‘second’“@en ;

rdfs:label “Flamingo Balance Test”@en .

Again, the first line declares that acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest is a data property, the second line defines its data type, and the following two lines define the description and the label. This data property is associated with the root class via an intermediate class acdsi:EUROFIT and is defined as one of the properties of this intermediate class. Additionally, its data type is defined as a restriction:

acdsi:EUROFIT rdf:type owl:Class ;

rdfs:subClassOf acdsi:ACDSiMeasurement ,

[ rdf:type owl:Restriction ;

owl:onProperty acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest ;

owl:allValuesFrom xsd:decimal

] ,

...

The ontology ACDSi is shown in

Figure 1 as presented in the Protégé GUI. The left side shows the class hierarchy, where the base class ACDSi Measurement is divided into four subordinate classes: EUROFIT, SLOfit, Anthropometry, and Person. The right-hand side lists the EUROFIT class’s annotations on the top and its subordinate class structure at the bottom, which consists of the data properties and their restricted data types. The OntoGraf diagram depicting all four classes with their annotations and data properties is shown in

Figure 2.

The data properties, which are subordinate classes to the root class, are found using the eval_path() function with a triple pattern as an argument. In the triple pattern, the object is fixed to the root class, and the path pattern consists of one or more concatenated rdfs:subClassOf predicates. The concatenation of predicates into variable-length paths is denoted as a combination of asterisk operator and the rdflib.paths.OneOrMore quantifier:

For example, the acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest data property is found because it is a subclass of acdsi:EUROFIT, which is in turn a subclass of the root class acdsi:ACDSiMeasurement. This method is flexible as such data property would be also found if it were nested deeper in the class hierarchy. Note that the intermediate classes (e.g. acdsi:EUROFIT) are not included in the results of this query. So they are not created as properties in NGSI-LD.

Next, the data properties connected to those classes are found as objects connected with the owl:onProperty predicate to the classes as subjects (see the acdsi:EUROFIT definition above):

Their data types are found through the restriction predicates owl:allValuesFrom or owl:someValuesFrom linked to the class as the subject. The allowed alternative predicates are denoted as separated with vertical bar:

If such a predicate is not found, the data type is found on the triple with rdfs:range predicate linked to the data property as the subject (see the acdsi:flamingoBalanceTest definition above):

The root class’s object properties are mapped to NGSI-LD references. They are found as subclasses of the root class:

The object properties are found through the owl:onProperty or owl:maxCardinality predicate linked to the object property as the subject:

There may be more than one object linked to an object property as the subject. They are found by searching through all the paths of various lengths containing the predicates owl:allValuesFrom, owl:unionOf, rdf:first, rdf:rest, or owl:maxCardinality:

rdflib.paths.eval_path(self.g, (pr [0][0], (OWL.allValuesFrom | OWL.unionOf | RDF.first | RDF.rest | OWL.maxCardinality) * rdflib.paths.OneOrMore, None))

If the object found is of type URI, it is transformed into an NGSI-LD reference. If it is of the Literal type, it is transformed into a data property.

For the classes that have an annotation rdfs:isDefinedBy among their superclasses, this annotation points to another ontology. This ontology is then parsed similarly to the primary one, and the superclass’s data properties are included in the final data properties list.

All the data properties’ names, descriptions, and data types and references and their descriptions are then put into a flat list. They are then serialized into the allOf.properties field of the generated schema.json file as a dictionary structure. All the IRIs of the root class and all the data properties are written to the notes_context.jsonld file.

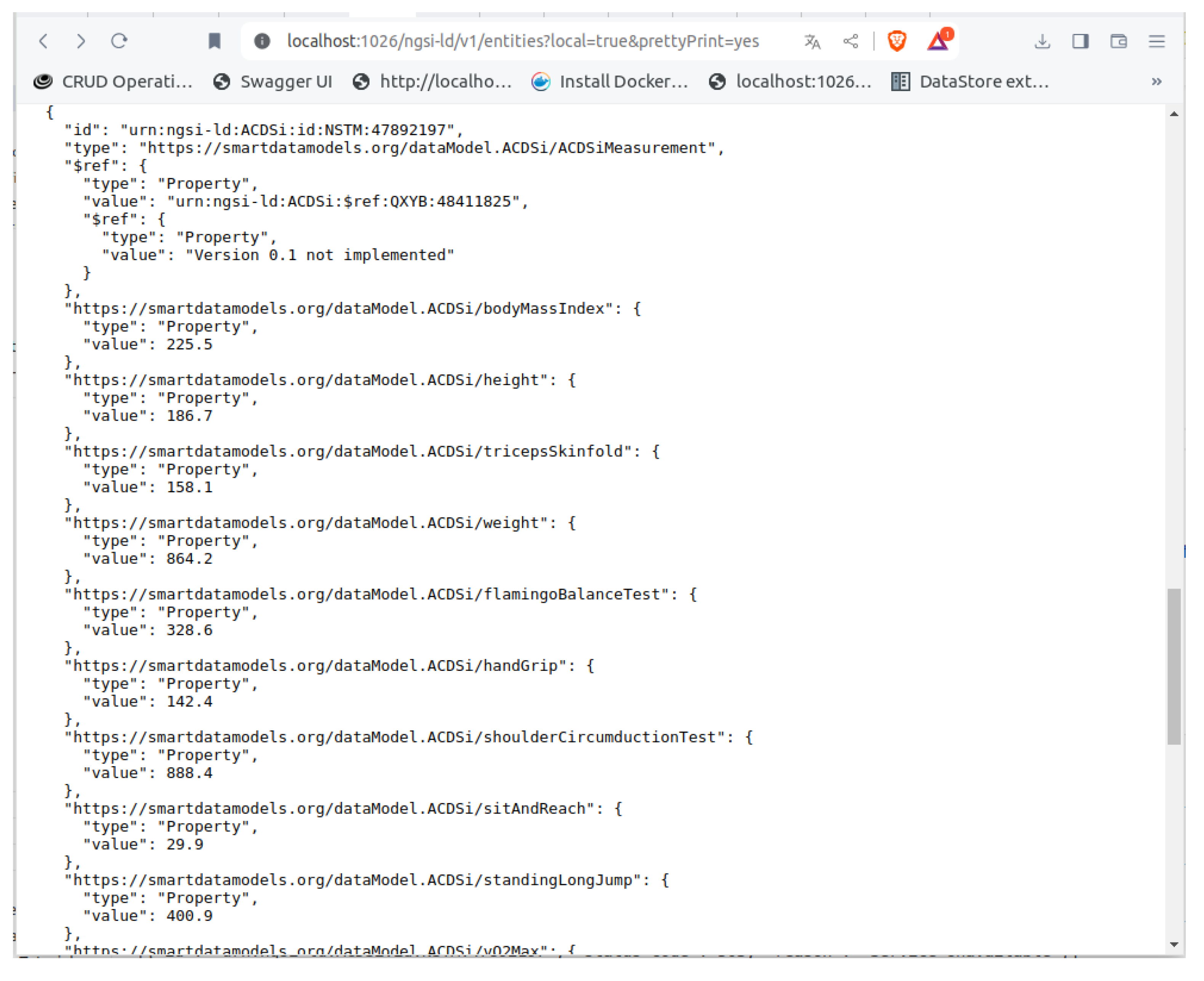

The third file, example-normalized.jsonld, is generated using the ngsi_ld_example_generator_str() function from the pysmartdatamodels package. The function takes the generated schema.json file contents and constructs a fictitious data structure conformant to the specification.

As the model had not yet been published on the smartdatamodels.org website, our local deployment had to provide the schema.json file as a locally served file. Additionally, a local context.jsonld file was needed. It was generated from the classes and data properties lists from the source RDF ontology in parallel and from the same data structure as the schema.json file.

After all the files were generated and the necessary files published locally, the generated example payload was uploaded successfully to a locally deployed Orion-LD Context Broker using the POST command to the “/ngsi-ld/v1/entities” endpoint.