Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

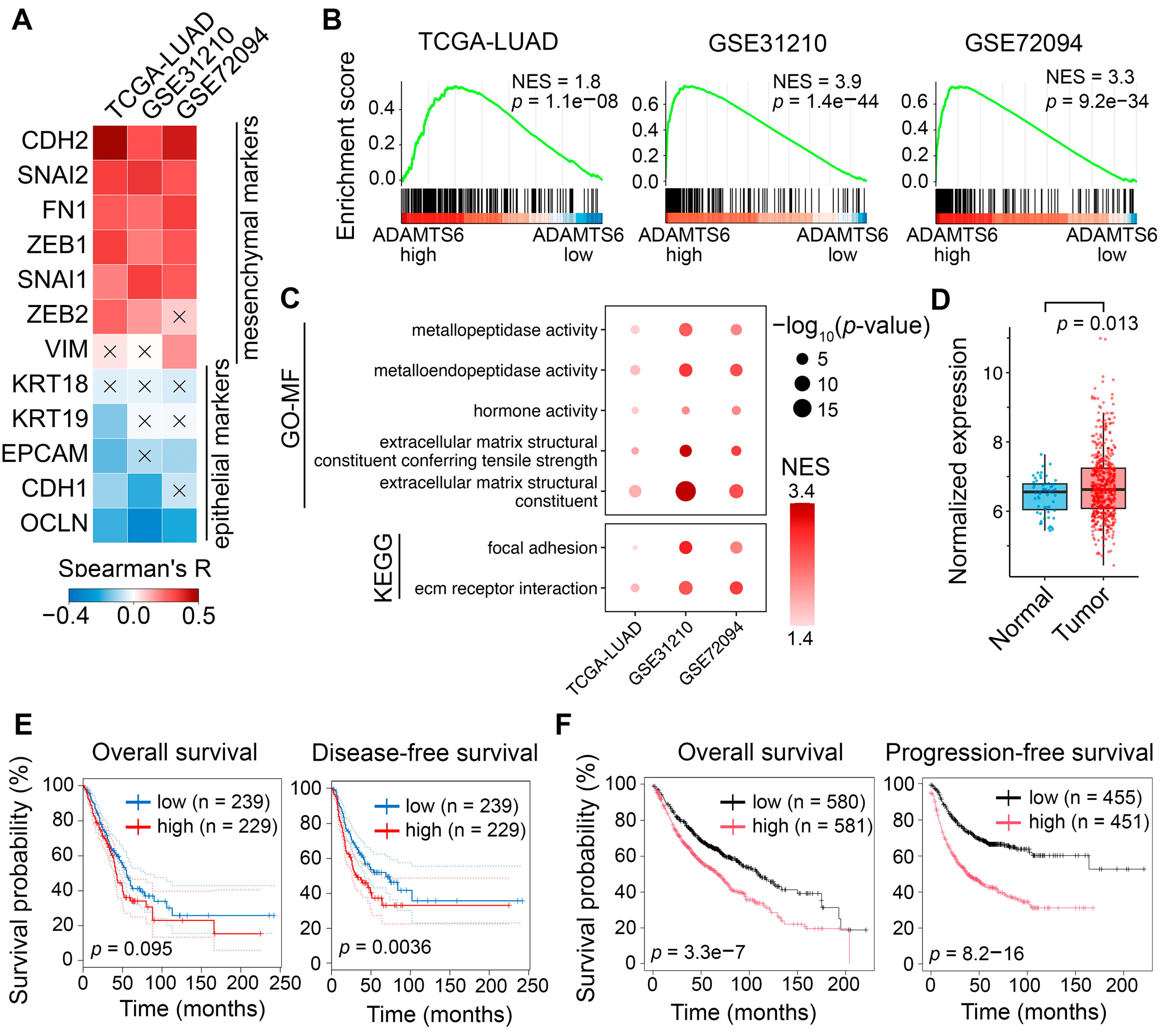

2.1. Assessing the EMT Regulatory Potential of ADAMTS6 in LUAD Cells

2.2. Validation the Link Between ADAMTS6 and EMT Induction in Pulmonary Epithelial Cells

2.3. Reconstruction of the EMT-Associated Upstream Regulatory Network for ADAMTS6 in LUAD Cells

2.4. The Development of a CRISP/Cas9 System Targeting ADAMTS6

2.5. Assessing the Effects of ADAMTS6 Knockout on EMT Characteristics of Human LUAD Cells

2.6. Validating Associations of ADAMTS6 with EMT in Patient Cohort

3. Discussion

- One of the enriched terms is “ECM-receptor interactions” (Figure 6C). ADAMTS6 cleaves the ECM-interacting receptor syndecan-4, as well as ECM components such as fibronectin and fibrillin-1 [13]. Syndecan-4, upregulated by TGF-β1 or delivered via extracellular vesicles, induces EMT in A549 cells [87,88]. Although syndecan-4 shedding does not directly drive EMT [87], it may influence EMT indirectly, as syndecan-4 binds TGF-β1 and attenuates SMAD3 activation [89]. Fibronectin proteolysis affects EMT in multiple ways, depending on the specific proteins released from its binding: the release of integrin α5β1 inhibits FAK activation and cell invasion [90], whereas the release of latent TGF-β1 activates the SMAD2/3 pathway in breast cancer cells [91]. Fibrillin-1 likely has little influence on EMT, acting downstream of syndecan-4 and fibronectin. Notably, fibronectin replaces syndecan-4 as the key regulator of fibrillin-1 deposition during TGF-β1-induced EMT [92]. Fibrillin-1 knockdown does not affect fibronectin expression or EMT-associated processes, including migration, invasion, and marker expression, in breast cancer cells [93].

- Another enriched term is “extracellular matrix structural constituent conferring tensile strength” (Figure 6C). ADAMTS6-mediated ECM cleavage may alter matrix stiffness, inducing EMT in LUAD cells though mechanical forces. Consistently, ADAMTS6 increases mechanotension in TC28a/2 chondrocytes, promoting YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation [17], a hallmark of EMT triggered by mechanical stress [79]. Together, latent TGF-β1, syndecan-4, fibronectin, and ECM stiffness are potential ADAMTS6 targets regulating EMT in LUAD cells and require further investigation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Acquisition

4.2. Microarray Analysis

4.3. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

4.4. Gene Network Analysis

4.5. Text Mining

4.6. scRNA-Seq Analysis

4.7. sgRNA Design and Cloning Strategy

4.8. Cell Lines and Transfection

4.9. Verification of CRISP/Cas9-Generated Mutation

4.10. Sanger Sequencing

4.11. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.12. Cell Viability Analysis

4.13. Wound Healing Assay

4.14. Transwell Assays

4.15. Evaluation of Cell Morphology

4.16. Adhesion Assay

4.17. Colony Formation

4.18. Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis

4.19. Survival Analysis

4.20. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Bao, X.; Chen, M.; Lin, R.; Zhuyan, J.; Zhen, T.; Xing, K.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, S. Mechanisms and Future of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Metastasis. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10, 585284. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; and Morris, J.C. Transforming Growth Factor-β: A Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2017, 13, 1741–1750. [CrossRef]

- Nurmagambetova, A.; Mustyatsa, V.; Saidova, A.; Vorobjev, I. Morphological and Cytoskeleton Changes in Cells after EMT. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 22164. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.N.; Ahn, D.H.; Kang, N.; Yeo, C.D.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, M.S.; Yim, H.W.; et al. TGF-β Induced EMT and Stemness Characteristics Are Associated with Epigenetic Regulation in Lung Cancer. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 10597. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Li, C.; Jin, E.; Su, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, H. Quaking 5 Suppresses TGF-β-induced EMT and Cell Invasion in Lung Adenocarcinoma. EMBO reports 2021, 22, e52079. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, E.L.; Kazenwadel, J.; Bert, A.G.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Ruszkiewicz, A.; Goodall, G.J. Down-Regulation of the miRNA-200 Family at the Invasive Front of Colorectal Cancers with Degraded Basement Membrane Indicates EMT Is Involved in Cancer Progression. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Cortes, E.; Lachowski, D.; Oertle, P.; Matellan, C.; Thorpe, S.D.; Ghose, R.; Wang, H.; Lee, D.A.; Plodinec, M.; et al. GPER Activation Inhibits Cancer Cell Mechanotransduction and Basement Membrane Invasion via RhoA. Cancers 2020, 12, 289. [CrossRef]

- Morelli, A.P.; Tortelli, T.C.; Mancini, M.C.S.; Pavan, I.C.B.; Silva, L.G.S.; Severino, M.B.; Granato, D.C.; Pestana, N.F.; Ponte, L.G.S.; Peruca, G.F.; et al. STAT3 Contributes to Cisplatin Resistance, Modulating EMT Markers, and the mTOR Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 1048–1058. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Pang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, L.; Ma, N.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Contributes to Docetaxel Resistance in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncology Research 2014, 22, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Shu-Ling, W.; Jing-Bo, H.; Ying, Z.; Rong, H.; Xiang-Qun, L.; Wen-Jie, C.; Lin-Fu, Z. MiR-451a Attenuates Doxorubicin Resistance in Lung Cancer via Suppressing Epithelialmesenchymal Transition (EMT) through Targeting c-Myc. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 125, 109962. [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, R.; Yuan, S.; Rainero, E. ADAMTS Proteases: Their Multifaceted Role in the Regulation of Cancer Metastasis. Diseases & Research 2024, 4, 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Cain, S.A.; Mularczyk, E.J.; Singh, M.; Massam-Wu, T.; Kielty, C.M. ADAMTS-10 and -6 Differentially Regulate Cell-Cell Junctions and Focal Adhesions. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 35956. [CrossRef]

- Mead, T.J. ADAMTS6: Emerging Roles in Cardiovascular, Musculoskeletal and Cancer Biology. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2022, 9, 1023511. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Mi, J. Calcium Channel TRPV6 Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis by NFATC2IP. Cancer Lett 2021, 519, 150–160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.J.; Kong, X.L. A Metalloproteinase of the Disintegrin and Metalloproteinases and the Thrombospondin Motifs 6 as a Novel Marker for Colon Cancer: Functional Experiments. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2020, 43, e20190266. [CrossRef]

- Cain, S.A.; Woods, S.; Singh, M.; Kimber, S.J.; Baldock, C. ADAMTS6 Cleaves the Large Latent TGFβ Complex and Increases the Mechanotension of Cells to Activate TGFβ. Matrix Biology 2022, 114, 18–34. [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Bruyère, D.; Etcheverry, A.; Aubry, M.; Mosser, J.; Warda, W.; Herfs, M.; Hendrick, E.; Ferrand, C.; Borg, C.; et al. EZH2 and KDM6B Expressions Are Associated with Specific Epigenetic Signatures during EMT in Non Small Cell Lung Carcinomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 3649. [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.-T.-T.; Bach, D.-H.; Kim, D.; Hu, R.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.K. Overexpression of AGR2 Is Associated With Drug Resistance in Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers. Anticancer Research 2020, 40, 1855–1866. [CrossRef]

- Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Nocoń, Z.; Pietrzak, J.; Krygier, A.; Balcerczak, E. Assessment of Methylation in Selected ADAMTS Family Genes in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 934. [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, J.; Świechowski, R.; Wosiak, A.; Wcisło, S.; Balcerczak, E. ADAMTS Gene-Derived circRNA Molecules in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Expression Profiling, Clinical Correlations and Survival Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 1897. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Yuan, X.; et al. ADAMTS16 Drives Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis through a Feedback Loop upon TGF-Β1 Activation in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15, 837. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, C.; Hu, N.; Hong, S. ADAMTS1 Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Regulating TGF-β. Aging 2023, 15, 2097–2114. [CrossRef]

- Gordian, E.; Welsh, E.A.; Gimbrone, N.; Siegel, E.M.; Shibata, D.; Creelan, B.C.; Cress, W.D.; Eschrich, S.A.; Haura, E.B.; Muñoz-Antonia, T. Transforming Growth Factor β-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Signature Predicts Metastasis-Free Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 810–824. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Daemen, A.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; Arnott, D.; Wilson, C.; Zhuang, G.; Gao, M.; Liu, P.; Boudreau, A.; Johnson, L.; et al. Metabolic and Transcriptional Profiling Reveals Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4 as a Mediator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Drug Resistance in Tumor Cells. Cancer & Metabolism 2014, 2, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kitai, H.; Ebi, H.; Tomida, S.; Floros, K.V.; Kotani, H.; Adachi, Y.; Oizumi, S.; Nishimura, M.; Faber, A.C.; Yano, S. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Defines Feedback Activation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling Induced by MEK Inhibition in KRAS-Mutant Lung Cancer. Cancer Discovery 2016, 6, 754–769. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, H.-H.; Ho, C.-W.; Ko, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. cytoHubba: Identifying Hub Objects and Sub-Networks from Complex Interactome. BMC Systems Biology 2014, 8, S11. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-L.; Feng, P.-H.; Lee, K.-Y.; Chen, K.-Y.; Sun, W.-L.; Van Hiep, N.; Luo, C.-S.; Wu, S.-M. The Role of EREG/EGFR Pathway in Tumor Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 12828. [CrossRef]

- Tauriello, D.V.F.; Sancho, E.; Batlle, E. Overcoming TGFβ-Mediated Immune Evasion in Cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2022, 22, 25–44. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, M. Transcriptional Regulation of EMT Transcription Factors in Cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2023, 97, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Qi, J.; Hou, Y.; Chang, J.; Ren, L. Upregulation of IL-11, an IL-6 Family Cytokine, Promotes Tumor Progression and Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 45, 2213–2224. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Hayakawa, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Saiki, I.; Yokoyama, S. Mesenchymal-Transitioned Cancer Cells Instigate the Invasion of Epithelial Cancer Cells through Secretion of WNT3 and WNT5B. Cancer Science 2014, 105, 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Li, S.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. CCL20 Promotes Lung Adenocarcinoma Progression by Driving Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 18, 4275–4288. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, D.M.; Han, R.; Deng, Y.Y.S.H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y. Low-Dose Radiation Promotes Invasion and Migration of A549 Cells by Activating the CXCL1/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. OncoTargets and Therapy 2020, 13, 3619–3629. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Song, Z.; Cao, C. MicroRNA-148a-3p Directly Targets SERPINE1 to Suppress EMT-Mediated Colon Adenocarcinoma Progression. Cancer Management and Research 2021, 13, 6349–6362. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xing, B. THBS1 Facilitates Colorectal Liver Metastasis through Enhancing Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2020, 22, 1730–1740. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fu, X.; Li, R. CNN1 Regulates the DKK1/Wnt/Β-catenin/C-myc Signaling Pathway by Activating TIMP2 to Inhibit the Invasion, Migration and EMT of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2021, 22, 855. [CrossRef]

- Kurppa, K.J.; Liu, Y.; To, C.; Zhang, T.; Fan, M.; Vajdi, A.; Knelson, E.H.; Xie, Y.; Lim, K.; Cejas, P.; et al. Treatment-Induced Tumor Dormancy through YAP-Mediated Transcriptional Reprogramming of the Apoptotic Pathway. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 104-122.e12. [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.; Meister, M.; Muley, T.; Thomas, M.; Sültmann, H.; Warth, A.; Winter, H.; Herth, F.J.F.; Schneider, M.A. Pathways Regulating the Expression of the Immunomodulatory Protein Glycodelin in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. International Journal of Oncology 2019, 54, 515–526. [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome Engineering Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Nature Protocols 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [CrossRef]

- Lykke-Andersen, S.; Jensen, T.H. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay: An Intricate Machinery That Shapes Transcriptomes. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 16, 665–677. [CrossRef]

- Gerstberger, S.; Jiang, Q.; Ganesh, K. Metastasis. Cell 2023, 186, 1564–1579. [CrossRef]

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Implications for Cancer. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2019, 20, 69–84. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-Y.; Fattet, L.; Tsai, J.H.; Kajimoto, T.; Chang, Q.; Newton, A.C.; Yang, J. Apical–Basal Polarity Inhibits Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Tumour Metastasis by PAR-Complex-Mediated SNAI1 Degradation. Nature Cell Biology 2019, 21, 359–371. [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, M.; Morales, X.; Castilla, C.; Pena, A.R.; Ederra, C.; Martínez, M.; Ariz, M.; Esparza, M.; Amaveda, H.; Mora, M.; et al. The Use of Mixed Collagen-Matrigel Matrices of Increasing Complexity Recapitulates the Biphasic Role of Cell Adhesion in Cancer Cell Migration: ECM Sensing, Remodeling and Forces at the Leading Edge of Cancer Invasion. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0220019. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K.; Wiktorska, M.; Sacewicz-Hofman, I.; Boncela, J.; Lewiński, A.; Kowalska, M.A.; Niewiarowska, J. Filamin A Upregulation Correlates with Snail-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Cell Adhesion but Its Inhibition Increases the Migration of Colon Adenocarcinoma HT29 Cells. Experimental Cell Research 2017, 359, 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, L.; Gao, G.; Liu, R.; Einaga, Y.; Zhi, J. Nanodiamonds Inhibit Cancer Cell Migration by Strengthening Cell Adhesion: Implications for Cancer Treatment. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 9620–9629. [CrossRef]

- Debaugnies, M.; Rodríguez-Acebes, S.; Blondeau, J.; Parent, M.-A.; Zocco, M.; Song, Y.; de Maertelaer, V.; Moers, V.; Latil, M.; Dubois, C.; et al. RHOJ Controls EMT-Associated Resistance to Chemotherapy. Nature 2023, 616, 168–175. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Saitoh, M.; Miyazawa, K. TGF-β Enhances Doxorubicin Resistance and Anchorage-Independent Growth in Cancer Cells by Inducing ALDH1A1 Expression. Cancer Science 2025, 116, 2176–2188. [CrossRef]

- Ashja Ardalan, A.; Khalili-Tanha, G.; Shoari, A. Shaping the Landscape of Lung Cancer: The Role and Therapeutic Potential of Matrix Metalloproteinases. International Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 4, 661–679. [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.R.; Mackay, A.R. Gelatinase B/MMP-9 in Tumour Pathogenesis and Progression. Cancers 2014, 6, 240–296. [CrossRef]

- Shoari, A.; Ashja Ardalan, A.; Dimesa, A.M.; Coban, M.A. Targeting Invasion: The Role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 35. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Stamenkovic, I. Cell Surface-Localized Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Proteolytically Activates TGF-β and Promotes Tumor Invasion and Angiogenesis. Genes and Development 2000, 14, 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, D.; Spinetti, G.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.-Q.; Pintus, G.; Monticone, R.; Lakatta, E.G. Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 Activation of Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 (TGF-Β1) and TGF-Β1–Type II Receptor Signaling Within the Aged Arterial Wall. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2006, 26, 1503–1509. [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.; Goel, S.; Al Khashali, H.; Darweesh, B.; Haddad, B.; Wozniak, C.; Ranzenberger, R.; Khalil, J.; Guthrie, J.; Heyl, D.; et al. Regulation of Soluble E-Cadherin Signaling in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells by Nicotine, BDNF, and β-Adrenergic Receptor Ligands. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2555. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Huo, Z.-X.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.-Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S.-S.; Lu, B. LRRC45 Promotes Lung Cancer Proliferation and Progression by Enhancing C-MYC, Slug, MMP2, and MMP9 Expression. Advances in Medical Sciences 2024, 69, 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Yu, N.; Han, Y.; Ainiwaer, J. The Long Non-Coding RNA MIAT/miR-139-5p/MMP2 Axis Regulates Cell Migration and Invasion in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Biosciences 2020, 45, 51. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, K.; Qu, Z.; Xie, Z.; Tian, F. ADAMTS8 Inhibited Lung Cancer Progression through Suppressing VEGFA. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 598, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Yang, W.; Ge, J.; Xiao, X.; Wu, K.; She, K.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, Y.; Wu, L.; Luo, S.; et al. ADAMTS4 Exacerbates Lung Cancer Progression via Regulating C-Myc Protein Stability and Activating MAPK Signaling Pathway. Biology Direct 2024, 19, 94. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, W.; Tan, R.; Li, T.; Chen, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, J.; et al. ADAMTS12 Promotes Oxaliplatin Chemoresistance and Angiogenesis in Gastric Cancer through VEGF Upregulation. Cellular Signalling 2023, 111, 110866. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Chen, J.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Mao, G.; Gai, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, J.; et al. Overexpression of ADAMTS5 Can Regulate the Migration and Invasion of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Tumor Biology 2016, 37, 8681–8689. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Mu, J.; Guo, S.; Ye, L.; Li, D.; Peng, W.; He, X.; Xiang, T. Inactivation of ADAMTS18 by Aberrant Promoter Hypermethylation Contribute to Lung Cancer Progression. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2019, 234, 6965–6975. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wu, K.-L.; Chiang, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Liu, L.-X.; Huang, Y.-C.; Hung, J.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of ADAMTS8 in Lung Adenocarcinoma without Targetable Therapy. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 902. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wu, K.-L.; Chiang, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Liu, L.-X.; Hung, J.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; et al. Downregulated ADAMTS1 Incorporating A2M Contributes to Tumorigenesis and Alters Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Biology 2022, 11, 760. [CrossRef]

- Cuffaro, D.; Ciccone, L.; Rossello, A.; Nuti, E.; Santamaria, S. Targeting Aggrecanases for Osteoarthritis Therapy: From Zinc Chelation to Exosite Inhibition. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 13505–13532. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Ni, W.; Xuan, Y. ADAMTS-6 Is a Predictor of Poor Prognosis in Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Experimental and Molecular Pathology 2018, 104, 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Wu, W.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, X. Molecular Mechanism of CD163+ Tumor-Associated Macrophage (TAM)-Derived Exosome-Induced Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Ascites. Annals of Translational Medicine 2022, 10, 1014. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gou, Q.; Xie, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H. ADAMTS6 Suppresses Tumor Progression via the ERK Signaling Pathway and Serves as a Prognostic Marker in Human Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 61273–61283. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Percevault, F.; Ryder, K.; Sani, E.; Le Cun, J.-C.; Zhadobov, M.; Sauleau, R.; Le Dréan, Y.; Habauzit, D. Effects of Radiofrequency Radiation on Gene Expression: A Study of Gene Expressions of Human Keratinocytes From Different Origins. Bioelectromagnetics 2020, 41, 552–557. [CrossRef]

- Kawata, M.; Koinuma, D.; Ogami, T.; Umezawa, K.; Iwata, C.; Watabe, T.; Miyazono, K. TGF-β-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Is Enhanced by pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Derived from RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. The Journal of Biochemistry 2012, 151, 205–216. [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, L.A.; Gardner, A.; De Soyza, A.; Mann, D.A.; Fisher, A.J. Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 (TGF-Β1) Driven Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Is Accentuated by Tumour Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) via Crosstalk Between the SMAD and NF-κB Pathways. Cancer Microenvironment 2012, 5, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Bevitt, D.J.; Mohamed, J.; Catterall, J.B.; Li, Z.; Arris, C.E.; Hiscott, P.; Sheridan, C.; Langton, K.P.; Barker, M.D.; Clarke, M.P.; et al. Expression of ADAMTS Metalloproteinases in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Derived Cell Line ARPE-19: Transcriptional Regulation by TNFα. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression 2003, 1626, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhao, W.; Vallega, K.A.; Sun, S.-Y. Managing Acquired Resistance to Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Through Co-Targeting MEK/ERK Signaling. Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy 2021, 12, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lei, Y.; Chu, Y.; Yu, X.; Tong, Q.; Zhu, T.; Yu, H.; Fang, S.; Li, G.; et al. NNMT Contributes to High Metastasis of Triple Negative Breast Cancer by Enhancing PP2A/MEK/ERK/c-Jun/ABCA1 Pathway Mediated Membrane Fluidity. Cancer Letters 2022, 547, 215884. [CrossRef]

- Ulanovskaya, O.A.; Zuhl, A.M.; Cravatt, B.F. NNMT Promotes Epigenetic Remodeling in Cancer by Creating a Metabolic Methylation Sink. Nature Chemical Biology 2013, 9, 300–306. [CrossRef]

- Wedler, A.; Bley, N.; Glaß, M.; Müller, S.; Rausch, A.; Lederer, M.; Urbainski, J.; Schian, L.; Obika, K.-B.; Simon, T.; et al. RAVER1 Hinders Lethal EMT and Modulates miR/RISC Activity by the Control of Alternative Splicing. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, 3971–3988. [CrossRef]

- Sławińska-Brych, A.; Mizerska-Kowalska, M.; Król, S.K.; Stepulak, A.; Zdzisińska, B. Xanthohumol Impairs the PMA-Driven Invasive Behaviour of Lung Cancer Cell Line A549 and Exerts Anti-EMT Action. Cells 2021, 10, 1484. [CrossRef]

- Abera, M.B.; Kazanietz, M.G. Protein Kinase Cα Mediates Erlotinib Resistance in Lung Cancer Cells. Molecular Pharmacology 2015, 87, 832–841. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Zang, G.; Song, S.; Sun, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, G.; Gui, N.; et al. Pin1/YAP Pathway Mediates Matrix Stiffness-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Driving Cervical Cancer Metastasis via a Non-Hippo Mechanism. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2023, 8, e10375. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Tong, X. CRTC2 Activates the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Diabetic Kidney Disease through the CREB-Smad2/3 Pathway. Molecular Medicine 2023, 29, 146. [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Tong, S.; Gao, L. Identification of MDK as a Hypoxia- and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition-Related Gene Biomarker of Glioblastoma Based on a Novel Risk Model and In Vitro Experiments. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 92. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, L.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Ji, Z. POLR3G Promotes EMT via PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Bladder Cancer. The FASEB Journal 2023, 37, e23260. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Fang, Z.; Tan, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W. TRIM66 Promotes Malignant Progression of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells via Targeting MMP9. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine 2022, 2022, 6058720. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Guan, J.-L. Compensatory Function of Pyk2 Protein in the Promotion of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK)-Null Mammary Cancer Stem Cell Tumorigenicity and Metastatic Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 18573–18582. [CrossRef]

- Tsujioka, M.; Miyazawa, K.; Ohmuraya, M.; Nibe, Y.; Shirokawa, T.; Hayasaka, H.; Mizushima, T.; Fukuma, T.; Shimizu, S. Identification of a Novel Type of Focal Adhesion Remodelling via FAK/FRNK Replacement, and Its Contribution to Cancer Progression. Cell Death & Disease 2023, 14, 256. [CrossRef]

- Sommerova, L.; Ondrouskova, E.; Vojtesek, B.; Hrstka, R. Suppression of AGR2 in a TGF-β-Induced Smad Regulatory Pathway Mediates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 546. [CrossRef]

- Toba-Ichihashi, Y.; Yamaoka, T.; Ohmori, T.; Ohba, M. Up-Regulation of Syndecan-4 Contributes to TGF-Β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2016, 5, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Thakur, C.; Bi, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ji, H.; Venkatesan, A.K.; Cherukuri, S.; Liu, K.J.; Haley, J.D.; et al. 1,4-Dioxane Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Carcinogenesis in an Nrf2-Dependent Manner. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2025, 14, e70072. [CrossRef]

- Tanino, Y.; Wang, X.; Nikaido, T.; Misa, K.; Sato, Y.; Togawa, R.; Kawamata, T.; Kikuchi, M.; Frevert, C.W.; Tanino, M.; et al. Syndecan-4 Inhibits the Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis by Attenuating TGF-β Signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 4989. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.V.; Madzharova, E.; Tan, A.C.; Allen, M.D.; Keller, U. auf dem; Louise Jones, J.; Carter, E.P.; Grose, R.P. ADAMTS3 Restricts Cancer Invasion in Models of Early Breast Cancer Progression through Enhanced Fibronectin Degradation. Matrix Biology 2023, 121, 74–89. [CrossRef]

- Belitškin, D.; Pant, S.M.; Munne, P.; Suleymanova, I.; Belitškina, K.; Hongisto, H.; Englund, J.; Raatikainen, T.; Klezovitch, O.; Vasioukhin, V.; et al. Hepsin Regulates TGFβ Signaling via Fibronectin Proteolysis. EMBO reports 2021, 22, e52532. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Cain, S.A.; Lennon, R.; Godwin, A.; Merry, C.L.R.; Kielty, C.M. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Status Influences How Cells Deposit Fibrillin Microfibrils. Journal of Cell Science 2014, 127, 158–171. [CrossRef]

- Lien, H.-C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Juang, Y.-L.; Lu, Y.-T. Fibrillin-1, a Novel TGF-Beta-Induced Factor, Is Preferentially Expressed in Metaplastic Carcinoma with Spindle Sarcomatous Metaplasia. Pathology 2019, 51, 375–383. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Q. Full-Length ADAMTS-1 and the ADAMTS-1 Fragments Display pro- and Antimetastatic Activity, Respectively. Oncogene 2006, 25, 2452–2467. [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Cho, M.; Wang, X. OncoDB: An Interactive Online Database for Analysis of Gene Expression and Viral Infection in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D1334–D1339. [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An Update to the Integrated Cancer Data Analysis Platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.P.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Context Specificity of the EMT Transcriptional Response. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2142. [CrossRef]

- Nitschkowski, D.; Vierbuchen, T.; Heine, H.; Behrends, J.; Reiling, N.; Reck, M.; Rabe, K.F.; Kugler, C.; Ammerpohl, O.; Drömann, D.; et al. SMAD2 Linker Phosphorylation Impacts Overall Survival, Proliferation, TGFβ1-Dependent Gene Expression and Pluripotency-Related Proteins in NSCLC. British Journal of Cancer 2025, 133, 52–65. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Pirooznia, M.; Li, Y.; Xiong, J. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Acetate Modulates Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2022, 33, br13. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.-S.; Kwon, E.-J.; Kong, H.-J.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, E.-W.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.; Cha, H.-J. Systematic Identification of a Nuclear Receptor-Enriched Predictive Signature for Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis. Redox Biology 2020, 37, 101719. [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.Y.; Hong, S.K.; Park, J.R.; Kwon, O.S.; Kim, K.T.; Koo, J.H.; Oh, E.; Cha, H.J. Chronic TGFβ Stimulation Promotes the Metastatic Potential of Lung Cancer Cells by Snail Protein Stabilization through Integrin Β3-Akt-GSK3β Signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 25366–25376. [CrossRef]

- Dvornikov, D.; Schneider, M.A.; Ohse, S.; Szczygieł, M.; Titkova, I.; Rosenblatt, M.; Muley, T.; Warth, A.; Herth, F.J.; Dienemann, H.; et al. Expression Ratio of the TGFβ-Inducible Gene MYO10 Is Prognostic for Overall Survival of Squamous Cell Lung Cancer Patients and Predicts Chemotherapy Response. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 9517. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Li, X.; Kalita, M.; Widen, S.G.; Yang, J.; Bhavnani, S.K.; Dang, B.; Kudlicki, A.; Sinha, M.; Kong, F.; et al. Analysis of the TGFβ-Induced Program in Primary Airway Epithelial Cells Shows Essential Role of NF-κB/RelA Signaling Network in Type II Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 529. [CrossRef]

- Gladilin, E.; Ohse, S.; Boerries, M.; Busch, H.; Xu, C.; Schneider, M.; Meister, M.; Eils, R. TGFβ-Induced Cytoskeletal Remodeling Mediates Elevation of Cell Stiffness and Invasiveness in NSCLC. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7667. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ong, S.L.; Tran, L.M.; Jing, Z.; Liu, B.; Park, S.J.; Huang, Z.L.; Walser, T.C.; Heinrich, E.L.; Lee, G.; et al. Chronic IL-1β-Induced Inflammation Regulates Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Memory Phenotypes via Epigenetic Modifications in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 377. [CrossRef]

- Ware, K.E.; Hinz, T.K.; Kleczko, E.; Singleton, K.R.; Marek, L.A.; Helfrich, B.A.; Cummings, C.T.; Graham, D.K.; Astling, D.; Tan, A.-C.; et al. A Mechanism of Resistance to Gefitinib Mediated by Cellular Reprogramming and the Acquisition of an FGF2-FGFR1 Autocrine Growth Loop. Oncogenesis 2013, 2, e39–e39. [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Jia, W.; Gong, Q.; Cui, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Targeting GFPT2 to Reinvigorate Immunotherapy in EGFR-Mutated NSCLC. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.03.01.582888. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mayo, M.W.; Xiao, A.; Hall, E.H.; Amin, E.B.; Kadota, K.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Jones, D.R. Loss of BRMS1 Promotes a Mesenchymal Phenotype through NF-κB-Dependent Regulation of Twist1. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2015, 35, 303–317. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).