Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The review was aimed at exploring models across Africa that could best help Lesotho succeed in its efforts to establish a case-based surveillance (CBS) system for their HIV program. Research involved looking through several sources and databases including EBSCOHOST, Google Scholar, Science Direct and PubMed. The insights of suitable models were from the following Africa countries: South Africa, Kenya, Guinea, Tanzania, Ghana, Mozambique and Zambia. The researched models focused on infectious diseases such as measles, HIVand COVID-19. The key takeaway is that setting up electronic medical records systems (EMRs) is critical as a first step for any effective CBS. Also, using unique identifiers, establishing clear data governance policies and building strong infrastructure is a necessity in making CBS work. For a successful establishment of CBS, Lesotho should adopt these strategies that can be sustainable, improve disease tracking, response and ultimately health outcomes for Basotho.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Interventions for a Successful HIV CBS

1.2. Challenges of Existing Health Systems for HIV Program in Africa

1.3. Aim and Objectives

- 1)

- To identify and describe the existing models for case-based health programs in Africa.

- 2)

- To determine successes and challenges to implementation of these models in Africa.

- 3)

- To assess the needs for development and implementation of a case-based surveillance and to recommend a model that could be relevant for Lesotho.

- 4)

- To identify any gaps in the models that could be considered when developing a case-based surveillance for HIV in an African setting.

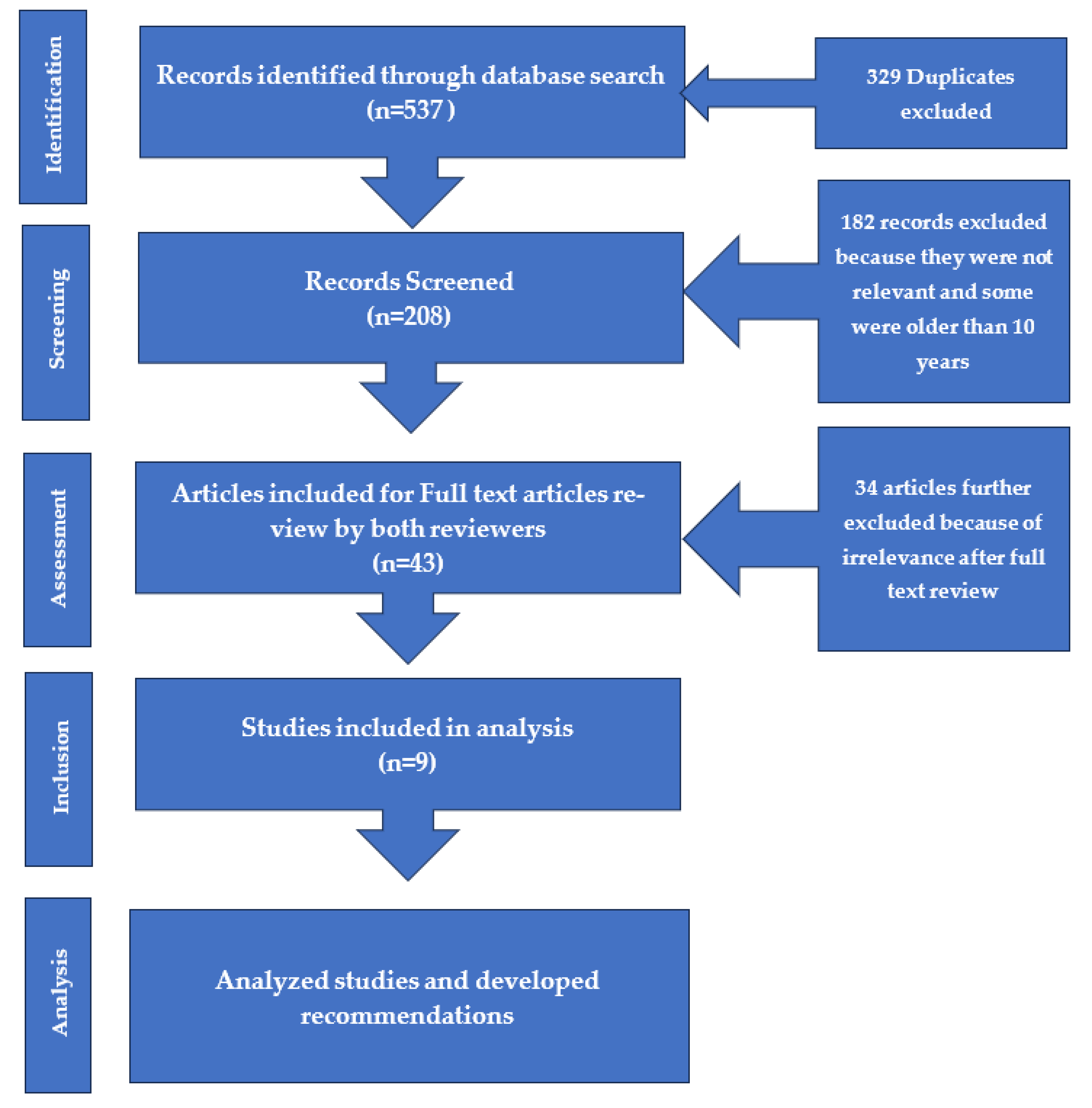

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Design

2.2. The Database Search

2.3. Inclusion of Data Sources

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

3.2. Types of Models/Systems

3.3. Challenges and Successes

3.3.1. Successes

- • Many African countries are responding to the WHO’s call of advocating for a person-centered approach of reporting through case-based surveillance as part of HIV patient monitoring guidelines.

- • System’s sensitivity was highlighted as critical in most studies to ensure that there is proper and early detection of public health threats.

- • The use of fingerprints and national ID by some countries are steps in the right direction giving hope to uniquely identify patients.

- • Some countries have developed health information systems that are interoperable which allow for secure data sharing and use which results in better care for patients and eliminates duplication.

- • Although many countries have highlighted inadequate and lack of funding for CBS, a decision to use open sources can bring some stability and continued maintenance of the systems in low-resource settings.

- • A study conducted in Rwanda proved a successful data exchange between multiple systems including EMR, Lab Information System (LIS), CR and DHIS2 tracker demonstrating a 100% match when generating a dataset for the HIV CBS.

- • This research highlighted the CBS implementation gaps which could help Lesotho to avoid when implementing CBS.

3.3.2. Challenges

- • Many countries are still struggling with finding the right UID for linking patients to the health services and tracking them in the long-term.

- • Many countries still do not have relevant policies that help ensure data security and confidentiality of patient’s information.

- • Infrastructure continues to be one of the major components hindering successful implementation of CBS especially in rural areas.

- • The use of both paper and electronics continues in many countries with paper-based systems being preferred because of lack of training and dedicated staff for electronic systems. The EMR case study done in Cape Town, South Africa, by Ohuabunwa et al. confirmed that there is resistance from the clinicians to use full EMR and some hospitals have opted to maintain paper-based systems.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| CBS | Case-Based Surveillance |

| EMRs | Electronic Medical Records |

| PLHIV | People Living with HIV |

| ART | Antiretroviral Treatment |

| UID | Unique Identification Number |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PEPFAR | President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief |

| LIS | Laboratory Information System |

| CR | Client Registry |

| DHIS2 | District Health Information System 2 |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| ECM | Enterprise Content Management |

| PMS | Patient Monitoring System |

| HL7 FHIR | Health Level Seven Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| SOPs | Standard Operating Procedures |

| SADC | Southern African Development Community |

| GPA | Global Program on AIDS |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| EBSCOHOST | A research database platform |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| STI | Sexually Transmitted Infection |

| ECM | Enterprise Content Management (also listed above) |

| N/A | Not Applicable |

References

- Ayanore et al. (2019, August). Towards Resilient Health Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of the English Language Literature on Health Workforce, Surveillance, and Health Governance Issues for Health Systems Strengthening. PubMed, 16(85(1)). [CrossRef]

- CDC. (2024). National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Retrieved April 7, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/index.html.

- Govender et al. (2023). Progress towards unique patient identification and case-based surveillance within the Southern African development Community. 29(1). doi:doi:10.1177/14604582221139058.

- Harklerode et al. (2017). Feasibility of Establishing HIV Case-Based Surveillance to Measure Progress Along the Health Sector Cascade: Situational Assessments. JMIR Public Health Surveillance. [CrossRef]

- Holmes JR, Dinh T, Farach N, et al. (2019). Status of HIV Case-Based Surveillance Implementation — 39 U.S. PEPFAR-Supported Countries, May–July 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 68:1089-1095. [CrossRef]

- Jayatilleke. (2020, August 28). Challenges in Implementing Surveillance Tools of High-Income Countries (HICs) in Low Middle Income Countries (LMICs). 191-201. [CrossRef]

- JMIR. (2018). Sustainable monitoring and surveillance systems to improve HIV programs: Review. JMIR, 4(4), e3. [CrossRef]

- Mabona et al. (2024). Evaluation of the malaria case surveillance system in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, 2022: a focus on DHIS2. [CrossRef]

- Mak S and Thomas A. (2022, Oct 5). Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J Grad Med Educ, 14(5), 565-567. [CrossRef]

- Mason, T. (2017, September). Health Information Technology is Helping Treat and Manage HIV for Patients and Providers. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://www.hiv.gov/blog/health-information-technology-helping-treat-and-manage-hiv-patients-and-providers#:~:text=Now%2C%20thanks%20to%20the%20work%20that%E2%80%99s%20been%20done,Affairs%2C%20and%20in%20a%20number%20of%20state-based%20programs.

- MOH. (2022). Lesotho Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2020. Maseru. Retrieved from http://phia.icap.columbia.edu.

- Ngangro NN, et al. (2022). An Automated Surveillance System (SurCeGGID) for the French Sexually Transmitted Infection Clinics: Epidemiological Monitoring Study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(10). [CrossRef]

- Ohuabunwa EC, Sun J, Jean Jubanyik K, Wallis LA. (2015, June). Electronic Medical Records in low to middle income countries: The case of Khayelitsha Hospital, South Africa. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Oluoch T. et al. (2023). Implementation of an HIV Case Based Surveillance Using Standards-Based Health Information Exchange in Rwanda. IOS Press. doi: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9621-5900.

- Page et. al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic review. International Journal of Surgery. Retrieved from https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/278760665/1_s2.0_S1743919121000406_main.pdf.

- Sherr et al. (2017). Measuring health systems strength and its impact: experience from the Africa Health Initiative. BMC. [CrossRef]

- Umeozuru CM et al. (2022). Performance of COVID-19 case-based surveillance system in FCT, Nigeria, March 2020 –January 2021. PLoS ONE. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2015). Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. PubMed, 11. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26020088/.

- WHO. (2023). Country Disease Outlook: Lesotho. Africa Region. Retrieved April 8, 2025, from https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2023-08/Lesotho.pdf.

- WHO. (2024). HIV statistics, globally and by WHO region, 2024. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/hq-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-library/hiv-epi-fact-sheet-march-2025.pdf?sfvrsn=61d39578_12.

- World Population Review. (2025). HIV Rates by Country. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hiv-rates-by-country.

| Author(s) | Article Type and Title | Population/health program | Study Design/Methods | Country/Region |

| Mabona et al. 2024 | Evaluation of the malaria case surveillance system in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, 2022: a focus on DHIS2 | Malaria surveillance system | A mixed-methods cross-sectional study design | South Africa/Southern Africa |

| Sherr et al. 2017 | Manuscript: Measuring health systems strength and its impact: experience from the Africa Health Initiative. | General population | Conceptual evaluative framework using World Health Organization’s health systems building block framework | African Health Initiative countries/multi-country |

| Ohuabunwa EC, Sun J, Jean Jubanyik K, Wallis LA., 2015 | Electronic Medical Records in low to middle income countries: The case of Khayelitsha Hospital, South Africa. | Trauma cases | Case study evaluating the ability and completeness of the EMR at Khayelitsha hospital to capture all emergencies classified as trauma. | South Africa/Southern Africa |

| Harklerode R, Schwarcz S, Hargreaves J, Boulle A, Todd J, Xueref S, Rice B., 2017 | Manuscript: Public Health and Surveillance. Feasibility of Establishing HIV Case-Based Surveillance to Measure Progress Along the Health Sector Cascade: Situational Assessments in Tanzania, South Africa, and Kenya. | HIV Population | A desk review of relevant materials on HIV surveillance and program monitoring, stakeholder meetings, and site visit | -Tanzania and Kenya/East Africa -South Africa/Southern Africa |

| Holmes JR, Dinh T, Farach N, et al., 2019 | Manuscript: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Status of HIV Case-Based Surveillance Implementation — 39 U.S. PEPFAR-Supported Countries, May–July 2019. | - HIV population -HIV CBS |

A survey using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) an electronic data management tool hosted at CDC and distributed to each PEPFAR-supported CDC country or regional office | 39 PEPFAR supported countries, with majority in Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Nyashadzashe Cosmas Makova et al., 2022 | Evaluation of the measles case-based surveillance system in Kwekwe city, 2017-2020: descriptive cross-sectional study | -General population -Measles CBS |

Descriptive cross-sectional study using CDC surveillance guidelines | Zimbabwe/Southern Africa |

|

Collins D, Rhea S, Diallo BI, Bah MB, Yattara F, Keleba RG, et al. (2020) |

Surveillance system assessment in Guinea: Training needed to strengthen data quality and analysis, 2016 | -General Population - Case and community-based surveillance for: cholera, meningococcal meningitis, measles, and yellow fever |

-In-depth interviews with key informants and site visits | Guinea/West Africa |

| Govender et al., 2023 | Progress towards unique patient identification and case-based surveillance within the Southern African development community | -HIV population -CBS with a unique patient identification (UPI) |

Mixed methods landscape analysis of UPI and CBS implementation | Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries |

| Oluoch et al., 2023 | Implementation of an HIV Case Based Surveillance Using Standards-Based Health Information Exchange in Rwanda | -HIV population -CBS for HIV implementation |

Quasi experimental, mixed methods | Rwanda/East Africa |

| Author | Disease Focus | Source of Funding | Countries | Model/System/Owner |

| Mabona et al. 2024 | Malaria | Internal: National Department of Health; no external donors mentioned | South Africa | -Evaluation: Malaria case surveillance system: DHIS2 -The systems in this article are DHIS2 which is used as central data management systems and malaria case surveillance flow system which supports tracking case classifications and ensures timely reporting of cases. -Data is collected by health care workers at facility level into Malaria surveillance system and then integrated into DHIS2 either manually or automatically. -Both systems are owned by the government of South Africa although managed by other partners. -The four critical components of a surveillance system are data quality, timeliness, simplicity, and acceptability -A effective surveillance system is critical in evaluating the plans to achieve elimination -Although data quality was generally accepted, timeliness of reporting cases within 24 hours remained a challenge -For optimum use and acceptability of the systems, giving feedback to lower surveillance levels is crucial |

| Sherr et al. 2017 | This article is not disease based but focused on population health with focus on child mortality | External: Doris Duke Charitable Foundation funded this study | Ghana, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Zambia | -Evaluation framework to measure health systems strength -Assessing association between health systems measures and health outcomes. -Six WHO core blocks measured were service delivery, Health workforce, information systems, medical products, vaccines and technologies, health financing and leadership and guidance. -There were some attributes of health systems that could not be evaluated and these include trust, resilience, quality, and leadership. -The six WHO health systems are limited in measuring validity, sensitivity and comprehensive metrics of health systems. -Effective evaluation of health systems strength requires sophisticated evaluation methods, indicators in context and understanding how various systems work. |

| Ohuabunwa EC, Sun J, Jean Jubanyik K, Wallis LA., 2015 | This study focuses on trauma cases | External: The study was externally funded by Down’s Fellowship and Yale School of Medicine but the donors of the system are not mentioned. | South Africa | -Electronic Medical Records system. -The assessment at KH was used as a proxy which would reflect nationwide estimates of about 40% of emergency center visits. -KH is using both Enterprise Content Management (ECM) and EMR. The systems were deployed in 2012 and are owned by the government although they are controlled by JAC Computer services because they are proprietary systems. Patient’s data is collected at the hospital through EMR, ECM and the file. -For a successful electronic medical record system, funding must be secured for adequate training and supervision of users and other necessary resources -Adequate records system is a pillar of the health facility without which it is prone to collapsing |

| Harklerode R, Schwarcz S, Hargreaves J, Boulle A, Todd J, Xueref S, Rice B., 2017 | Focused on HIV | External: The article was externally funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, WHO and Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria but the systems are public or government owned. | Tanzania, South Africa, and Kenya. | -Situational Assessment: Case-base surveillance -All systems are owned by the government -In Tanzania, data is collected at individual-level from point of entry into care on approximately two-thirds of people on ART. In SA, the system collects individual-level data at the facility and then reported to the national level including names and other personal identifiable factors. In Kenya, EMRs are used for facilities with patients greater than 500. Individual-level data are captured in the EMR, and aggregate data is reported to the central data warehouse on quarterly basis. -The systems though funded externally are owned by the government in respective countries. -All the three countries do not have policies for HIV reporting, data security and confidentiality. The only policy in SA is for vital registration data and Kenya has some policy for infectious diseases but not specific to HIV. -In Tanzania and Kenya, de-duplication of patients’ data is done using clinical identifier while SA uses an algorithm -All the three countries reported internet challenges in the rural areas. -Tanzania thought of interoperability as unnecessary because the PMS database is national. SA on the other hand uses Tier.Net which is also a national system therefore limiting interoperability issues. Kenya has 4 EMRs that are not interoperable and data in each system has not been evaluated. |

| Holmes JR, Dinh T, Farach N, et al., 2019 | The disease focus in this article was HIV | External: The study was funded by the United States Government through CDC/PEPFAR program | Angola, Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Kenya, Laos, Lesotho, Mali, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe | -CBS implementation assessment -Of the 20 countries implementing CBS, all collect date of HIV diagnosis and 85% collect sentinel event survey data and 50% of these countries use the UID to link and de-duplicate patients’ data. -Countries already implementing CBS and those planning to implement have funding, mostly from PEPFAR and they have dedicated human resource for the systems. -Of the 39 countries assessed, 20 had already implemented CBS, 15 were planning to 4 were not planning to implement -Challenges reported especially in Sub-Saharan Africa included lack of UID limiting data linkage across systems and lack of national policies and data security standards. -The 4 countries that were not planning to implement CBS indicated lack of funding and dedicated human resources as major barriers. |

| Nyashadzashe Cosmas Makova et al., 2022 | Measles | Internal: This is a public health surveillance and there is no mention of external donors. | Zimbabwe | -Descriptive cross-sectional assessment using CDC guidelines for surveillance system evaluation. The measles CBS in Zimbabwe is a government owned system integrated with other vaccine preventable diseases such as acute flaccid paralysis. -Data for all suspected cases of measles is routinely collected at all levels of health delivery using measles case surveillance form. -Data from primary health facilities is sent to the district, then to the province and finally to the national level. - This system is owned by the local Department of Health -The evaluation revealed that although most users confirmed that the CBS was simple, it lacked stability, acceptability and sensitivity. -Lack of training was shown as one of problems for underperformance of measles CBS. -Also, lack of relevant staff for the system hindered its optimum use. -Engagement of relevant stakeholders such as private sector and the community is key for the success of the system. |

|

Collins D, Rhea S, Diallo BI, Bah MB, Yattara F, Keleba RG, et al. (2020) |

The assessment focused on four (4) diseases namely: cholera, meningococcal meningitis, measles and yellow fever | External: The study was funded by the US Government through CDC but is a government owned public health surveillance system. | Guinea | -Surveillance system assessment using CDC’s guidelines for surveillance system evaluation. -This is a government owned system supported by international partners. -The assessment was focused on focused on the surveillance system’s operations, resources, and attributes particularly simplicity and data quality) -At health center level, the surveillance system is paper-based while at prefectural and central levels, it is computer spreadsheet-based. -The Ministry of Health surveillance protocol required immediate and routine weekly reporting at health and prefectural levels and then reported at central by telephone. -This is a public health system owned by the government in Guinea -The assessment revealed that the system in Boffa was simple but had limitations in documentation and data analysis. -The Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016 revealed Guinea’s weak health systems and surveillance gaps hindering proper detection and swift response to emerging disease outbreaks. -The system’s sensitivity was determined as low as no cases or the 4 diseases were identified during the assessment period although data suggested existence of cases -For a successful surveillance system, the country needs to improve capacity building for the users, improve infrastructure such as electricity and enhance feedback mechanisms to encourage data analysis and use. |

| Govender et al., 2023 | The assessment focuses on HIV although there is mention of hypertension, diabetes, and TB. | External: The assessment was funded though PEPFAR and there is strong emphasis strong US support to health information systems. | Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe |

- landscape analysis of unique patient identification (UPI) and CBS implementation within selected SADC countries -The commonly collected identifiers are patient name, date of birth, government ID, phone numbers and facility file number. -The system is owned by the government through Ministry of Health in all the countries respectively. -UPI implementation is limited by paper-based systems and lack of integration between health information systems. -Many countries still rely on paper-based systems and fragmented electronic systems that are not integrated. -Common CBS barriers include limited financial resources, lack of capacity building for staff, limited systems interoperability, data security and lack of confidentiality for patients’ information. -Most SADC countries are in the early to middle stages of developing patient-centered, case-based surveillance systems using UPIs. |

| Oluoch et al., 2023 | Disease focus is HIV | External: The HIV CBS in Rwanda is particularly PEPFAR funded | Rwanda | -Conducted an assessment of health information exchange ecosystem focusing on open-sources and standards supporting generation of complete data sets needed for HIV CBS in Rwanda. -The systems are owned by the government but financially supported by PEPFAR. -Data collection is done at health center level and collects patient -level data. -The study revealed that using open sources such as HL7 FHIR is effective and enables interoperability of systems in low-resource settings. -In the absence of national ID as UID, the study demonstrated that UID can be done with client registry linking it with demographic data and multiple identifiers to enable linkage and matching across different systems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).