Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design and Grouping

2.3. Sample Collection and Measurements

2.4. Data Processing and Formulas

2.5. Ethics and Data Reliability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inflammatory and Oxidative Changes Under Different Diets

3.2. Gene Expression and Pathway Response

3.3. Oxidative Balance and Antioxidant Capacity

3.4. Gut Barrier and Overall Metabolic Response

4. Conclusion

References

- Oguntibeju, O. O. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation: examining the links. International journal of physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacology 2019, 11(3), 45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mansoor, G.; Tahir, M.; Maqbool, T.; Abbasi, S. Q.; Hadi, F.; Shakoori, T. A.; …; Ullah, I. Increased expression of circulating stress markers, inflammatory cytokines and decreased antioxidant level in diabetic nephropathy. Medicina 2022, 58(11), 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, H. Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Glucose Homeostasis through High-Fiber Dietary Intervention in Type 2 Diabetes Management. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, A. M. Endothelial response to glucose: dysfunction, metabolism, and transport. Biochemical Society Transactions 2021, 49(1), 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Zhou, J. R. Gut microbiota dysbiosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and epigenetic alterations in metabolic diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13(8), 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Zelig, R.; Brown, T.; Radler, D. R. A review of the effect of the ketogenic diet on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Precision Nutrition 2025, 4(1), e00100. [Google Scholar]

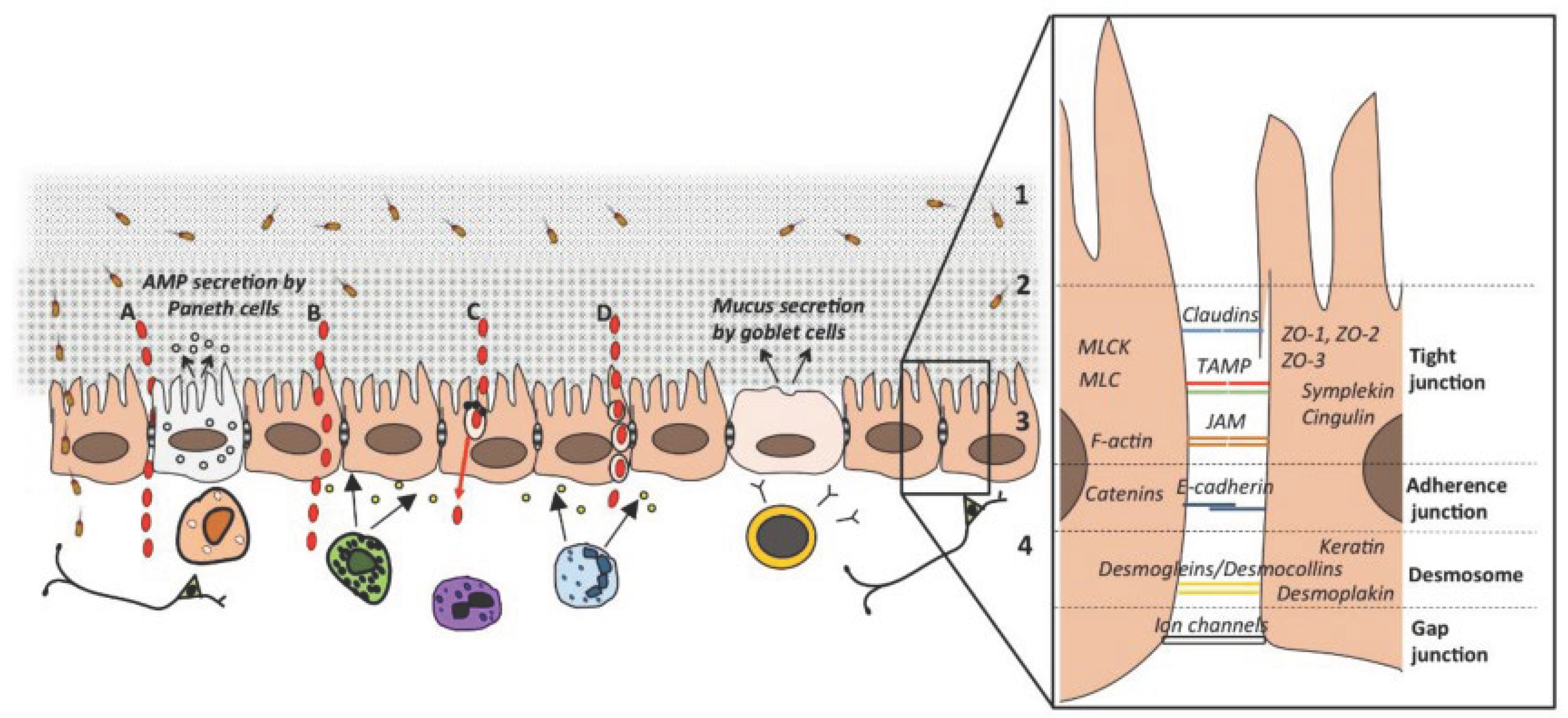

- Beukema, M.; Faas, M. M.; de Vos, P. The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells. Experimental & molecular medicine 2020, 52(9), 1364–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Suk, J. S. Enhancing nanoparticle penetration through airway mucus to improve drug delivery efficacy in the lung. Expert opinion on drug delivery 2021, 18(5), 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, S.; Hajir, J.; Sukhobaevskaia, V.; Weickert, M. O.; Pfeiffer, A. F. Impact of dietary fiber on inflammation in humans. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

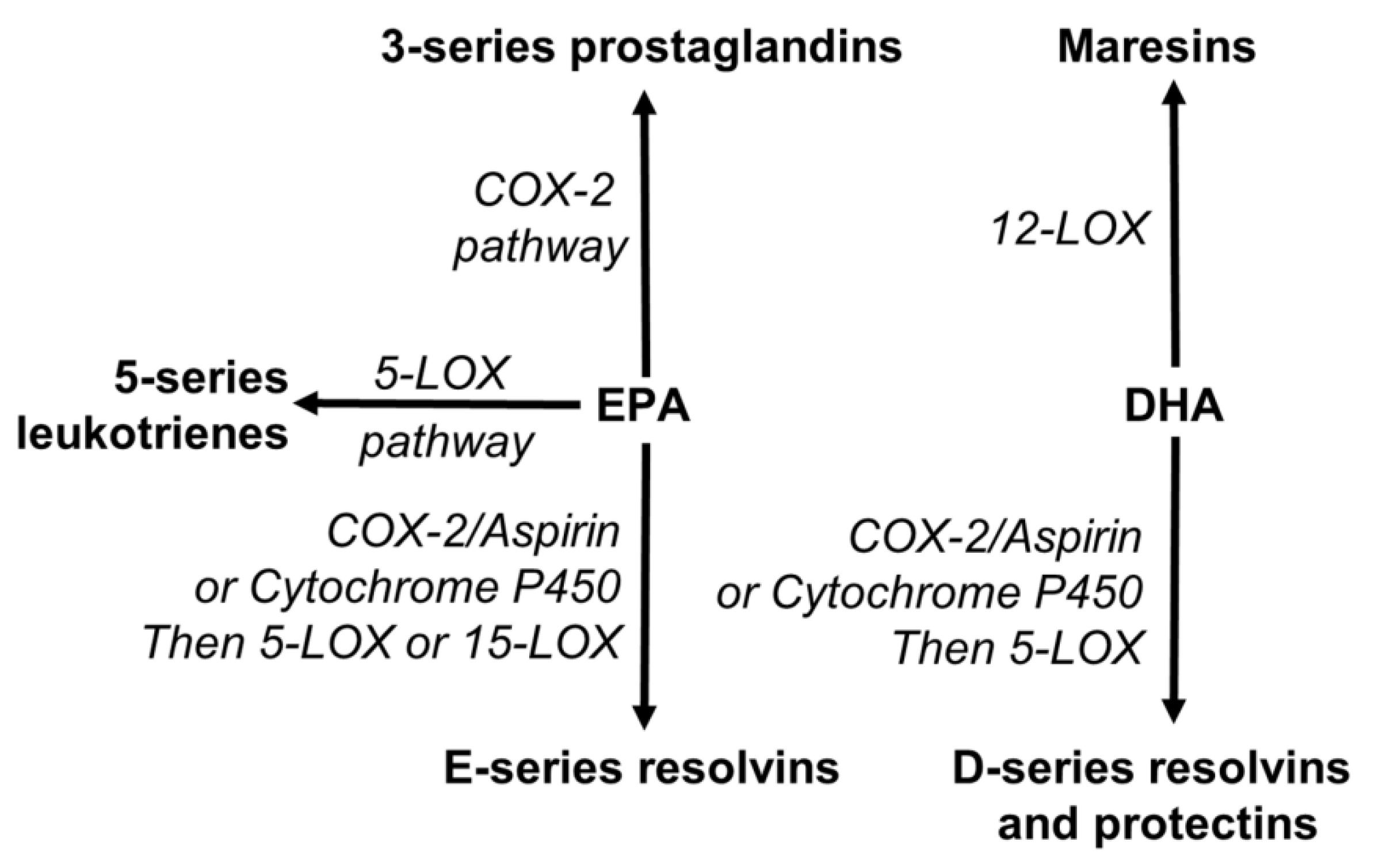

- Siriwardhana, N.; Kalupahana, N. S.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Health benefits of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Advances in food and nutrition research 2012, 65, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T.; Huang, M.; Xu, K.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; …; Sun, X. LEGEND: Identifying Co-expressed Genes in Multimodal Transcriptomic Sequencing Data. bioRxiv 2024. 2024-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, H. Application of Ultrasonic Treatment to Enhance Antioxidant Activity in Leafy Vegetables. International Journal of Advance in Applied Science Research 2024, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, Z. E.; Ribnicky, D. M.; Raskin, I.; Hsia, D. S.; Rood, J. C.; Gurley, B. J. Designing a clinical study with dietary supplements: it’s all in the details. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 8, 779486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Trimbach, H. An OWL ontology representation for machine-learned functions using linked data. In 2016 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress); IEEE, June 2016; pp. 319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J. The Effects of SCFAs and EPA on Ethanol Toxicity in Sh-SY5Y Cells. Master’s thesis, Lamar University-Beaumont, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Mao, H.; Qin, W.; Wang, B. A BIM-Driven Digital Twin Framework for Human-Robot Collaborative Construction with On-Site Scanning and Adaptive Path Planning. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Metrani, R.; Shivanagoudra, S. R.; Jayaprakasha, G. K.; Patil, B. S. Review on bile acids: effects of the gut microbiome, interactions with dietary fiber, and alterations in the bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2019, 67(33), 9124–9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ning, P.; Li, J.; Mao, Y. Energy Consumption Analysis and Optimization of Speech Algorithms for Intelligent Terminals. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Korunes, K. L.; Liu, J.; Huang, R.; Xia, M.; Houck, K. A.; Corton, J. C. A gene expression biomarker for predictive toxicology to identify chemical modulators of NF-κB. PLoS One 2022, 17(2), e0261854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y. Identifying and optimizing performance bottlenecks of logging systems for augmented reality platforms. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, P. C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? British journal of clinical pharmacology 2013, 75(3), 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Lu, Y.; Hou, S.; Liu, K.; Du, Y.; Huang, M.; …; Sun, X. Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications 2024, 15(1), 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).