Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

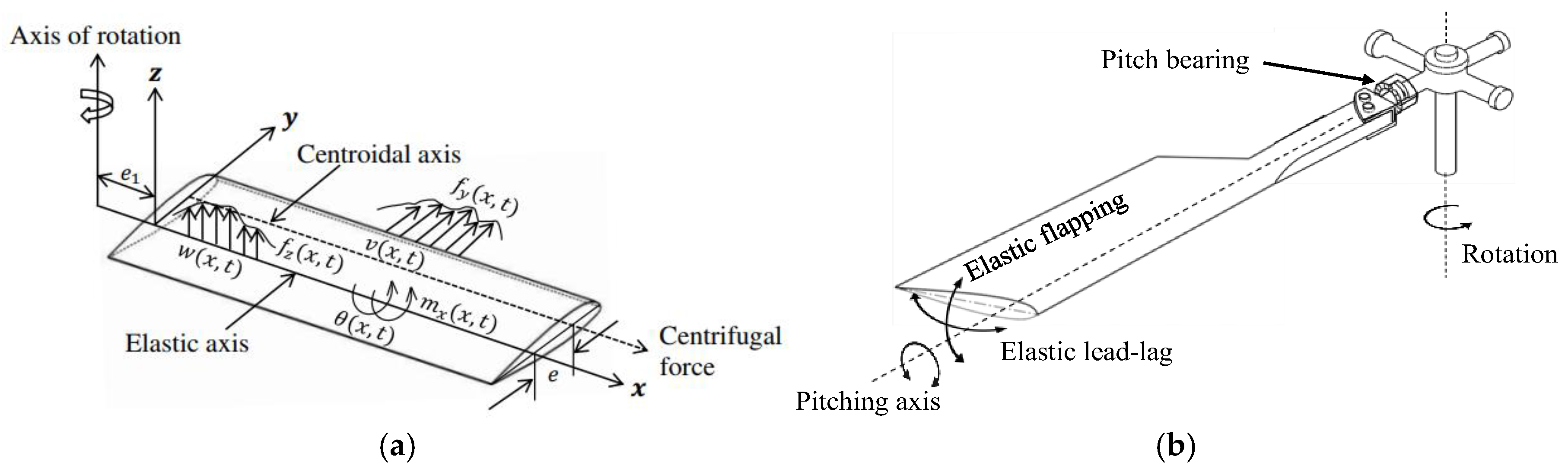

2.1. Modeling of the Composite Helicopter Rotor Blade

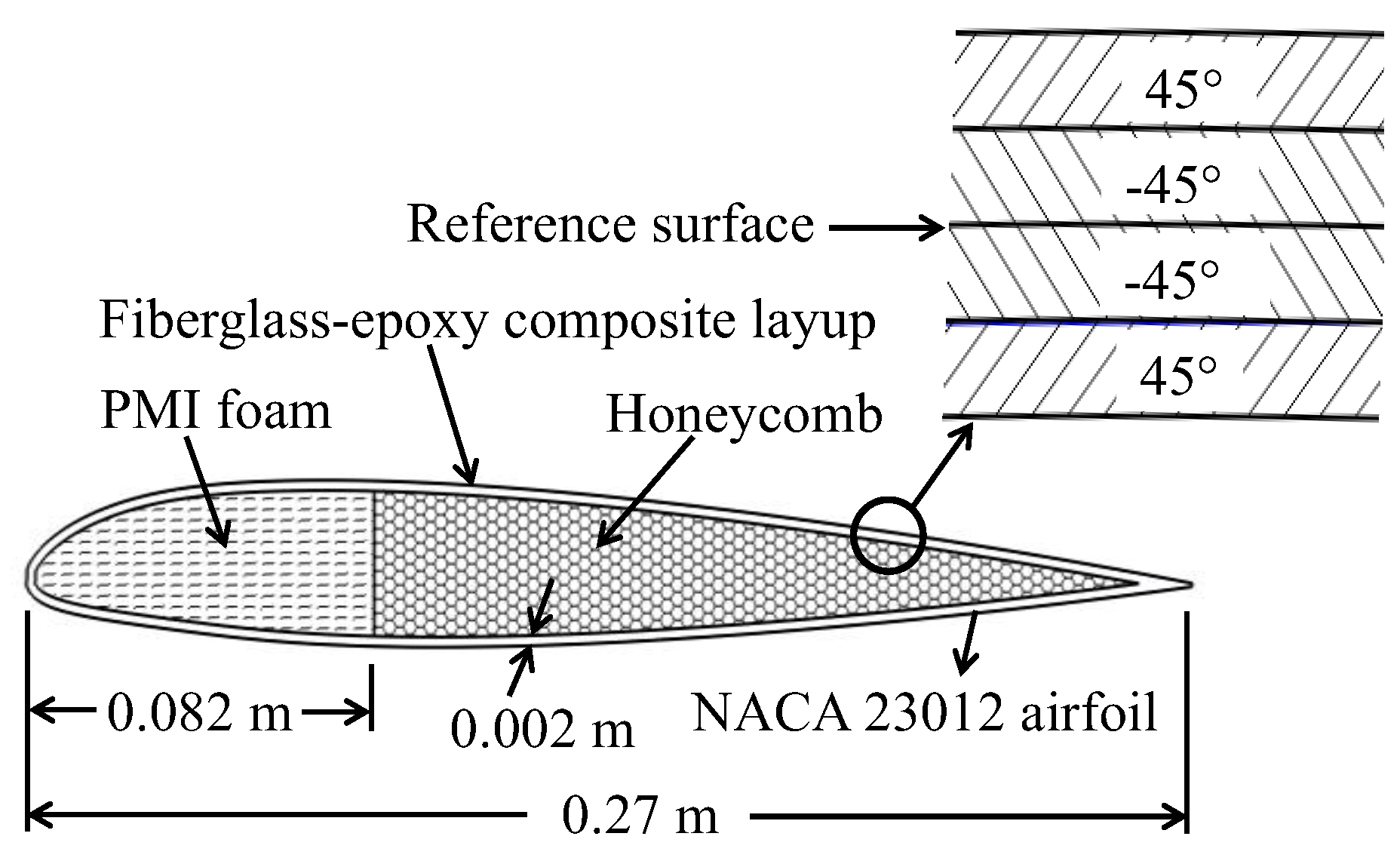

2.1.1. Physical model: The Bo 105 Helicopter Rotor Blade

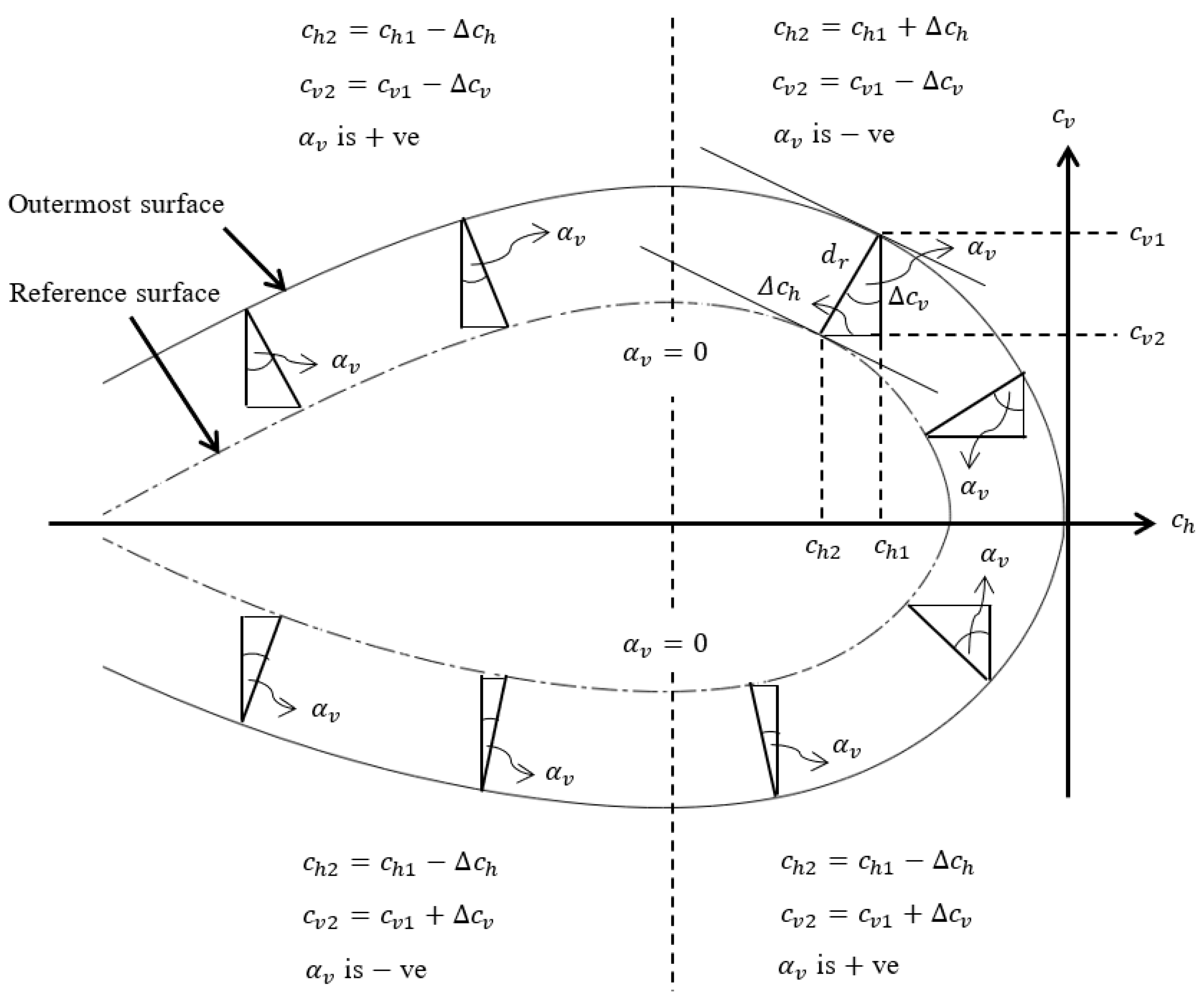

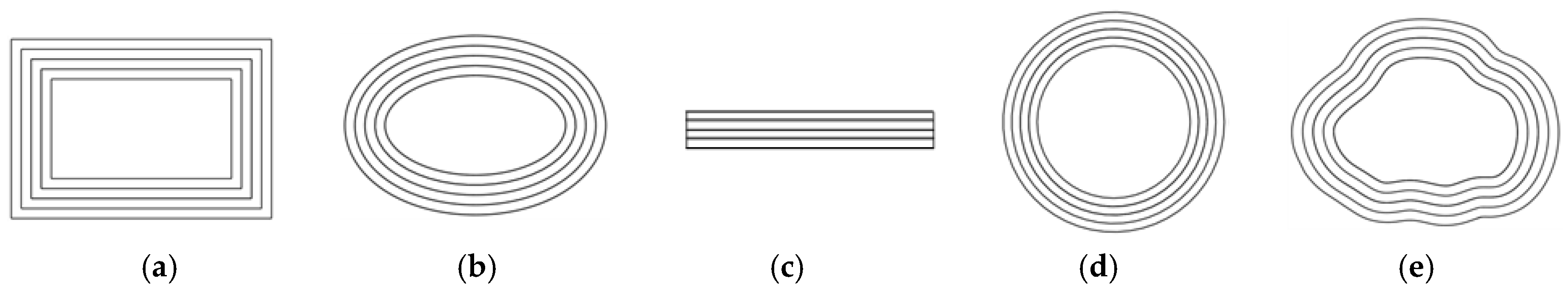

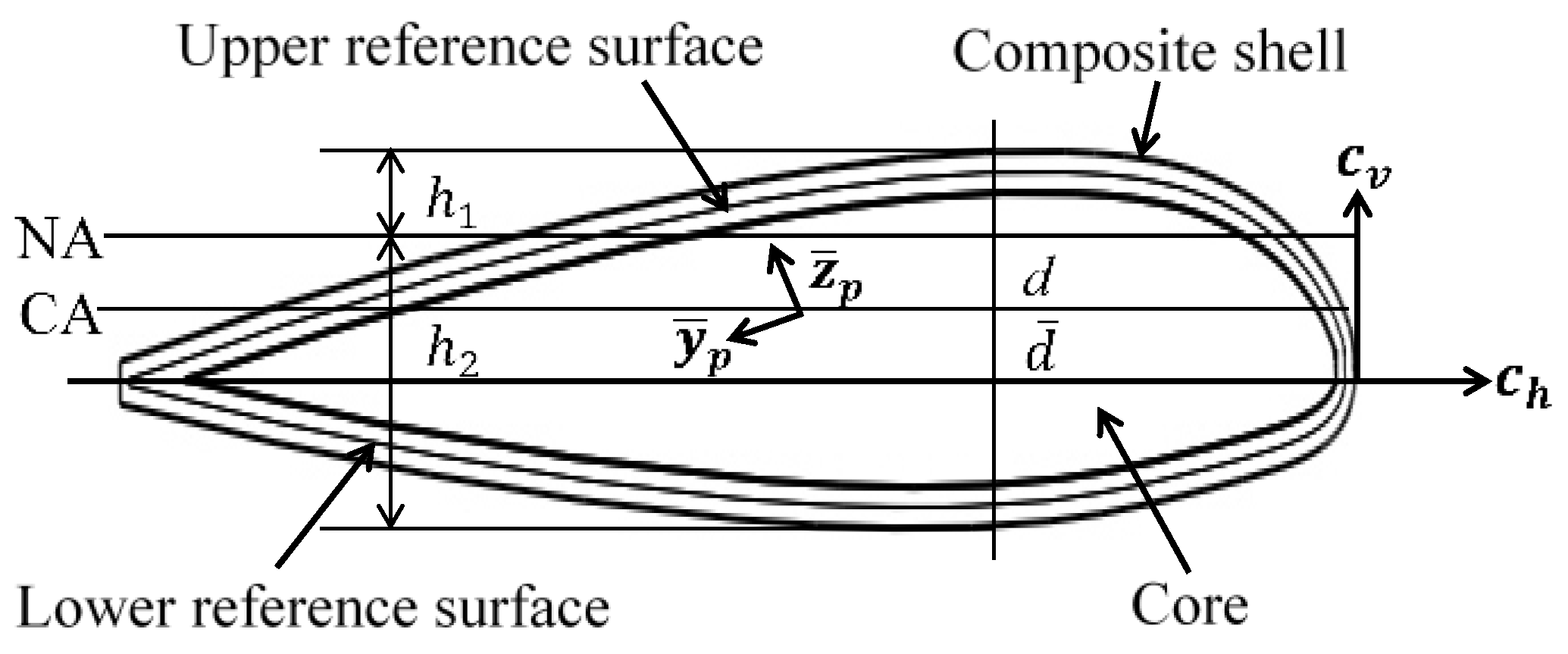

2.1.2. Cross-Sectional Analysis

2.1.3. Extensional Stiffness Per Unit Width

2.1.4. Out-of-Plane Bending (Flapping) and In-Plane Bending (Lead-Lag) Stiffness

2.1.5. Torsional Stiffness

2.1.6. Mass Per Unit Length

2.2. Modeling of Free Vibration for the Composite Helicopter Rotor Blade

2.2.1. Governing Equations of Motion

2.2.2. Boundary Conditions

2.2.3. Natural Frequencies of Free Vibration from the Modified Galerkin Method

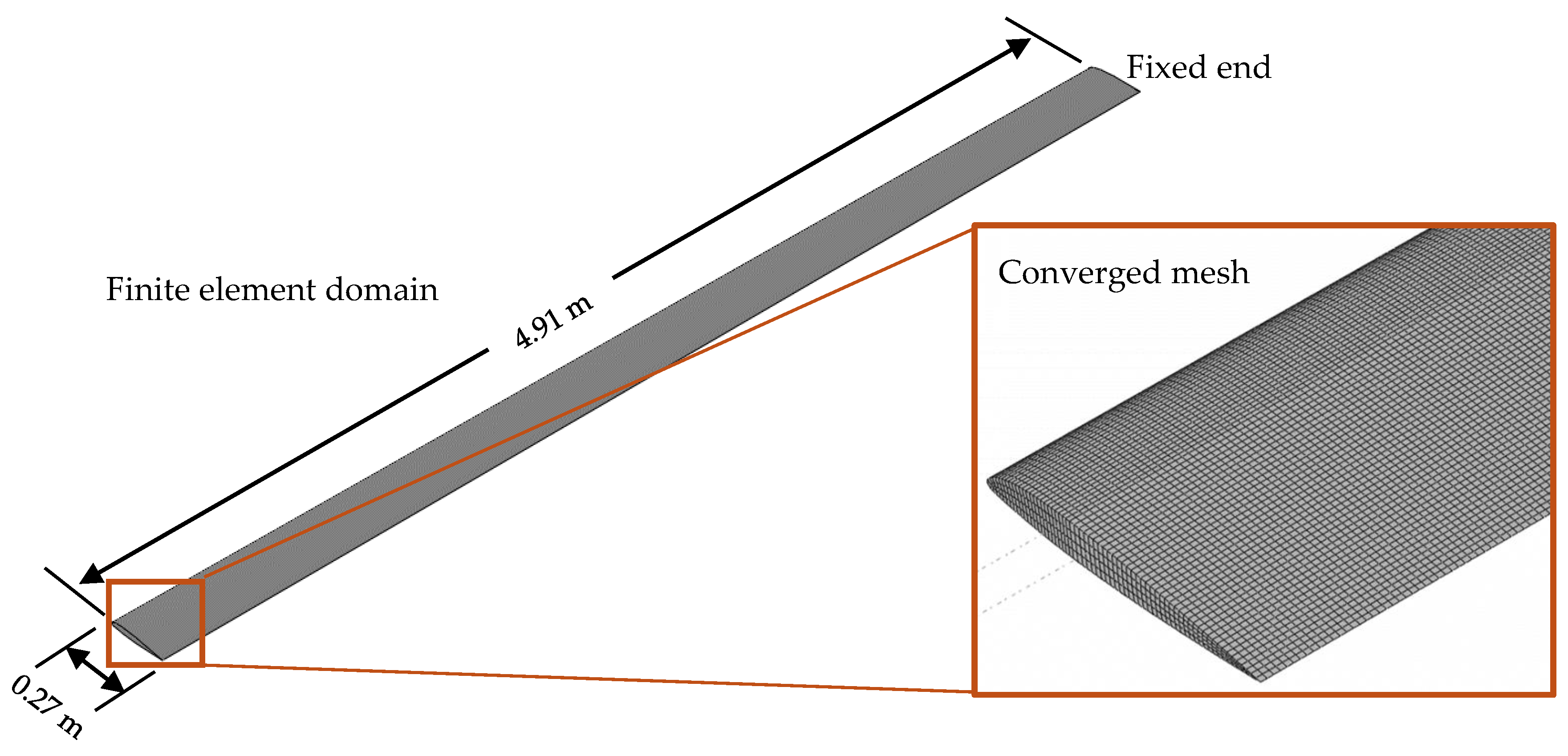

2.2.4. Natural Frequencies of Free Vibration from Finite Element Analysis

2.3. Orthogonality Condition for Triply Couple Vibration and the State Space Model

2.3.1. Generalized Force and Moment for Coupled Vibration of the Rotor Blade

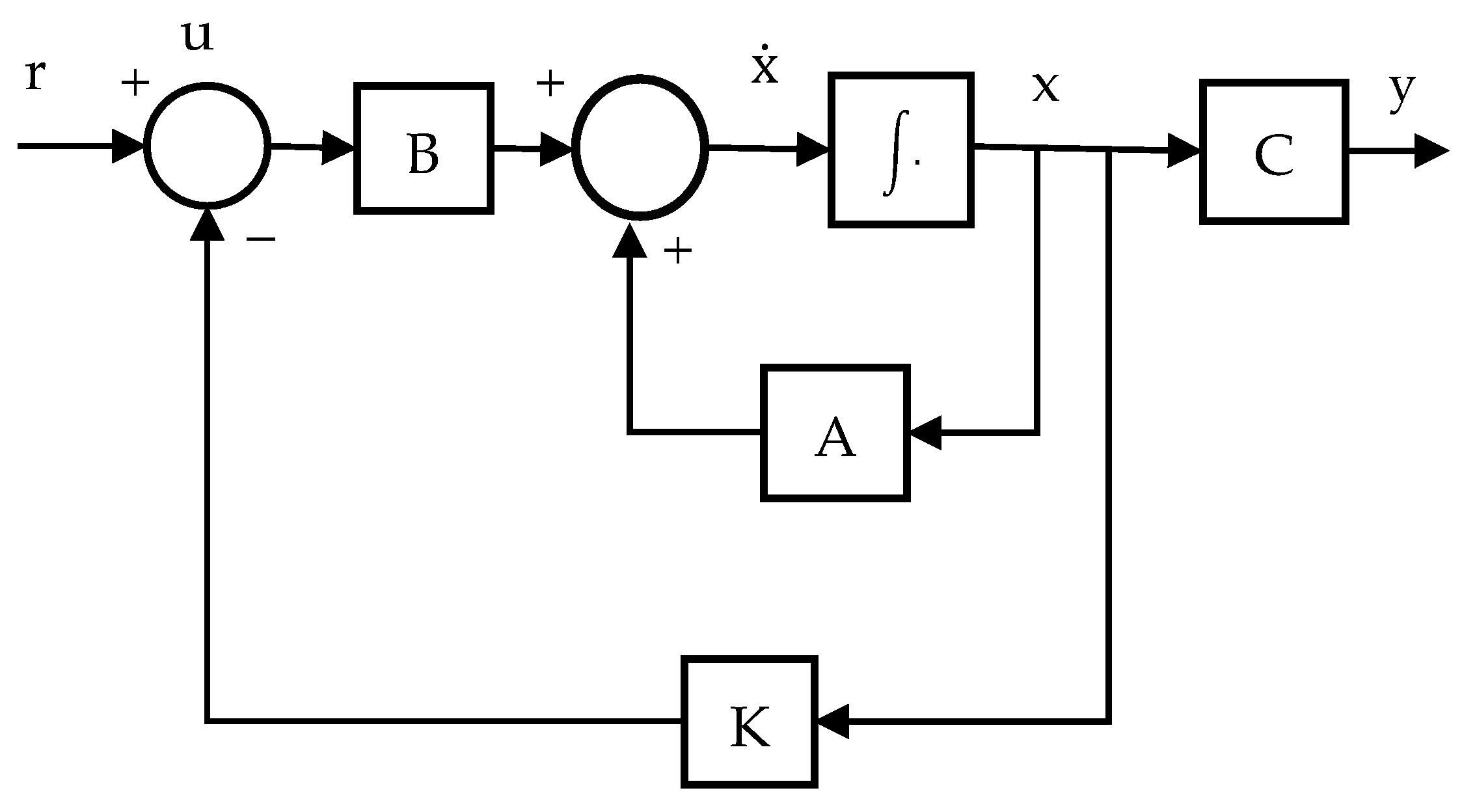

2.3.2. The State-Space Model

2.4. Aerodynamic Force and Moment

2.5. Controller Design

2.5.1. Optimal Vibration Control Framework

2.5.2. Linear Quadratic Regulator

3. Model Validation

3.1. Experimental Validation of Natural Frequencies

3.2. Validation for Vibration Control

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Vibration Analysis

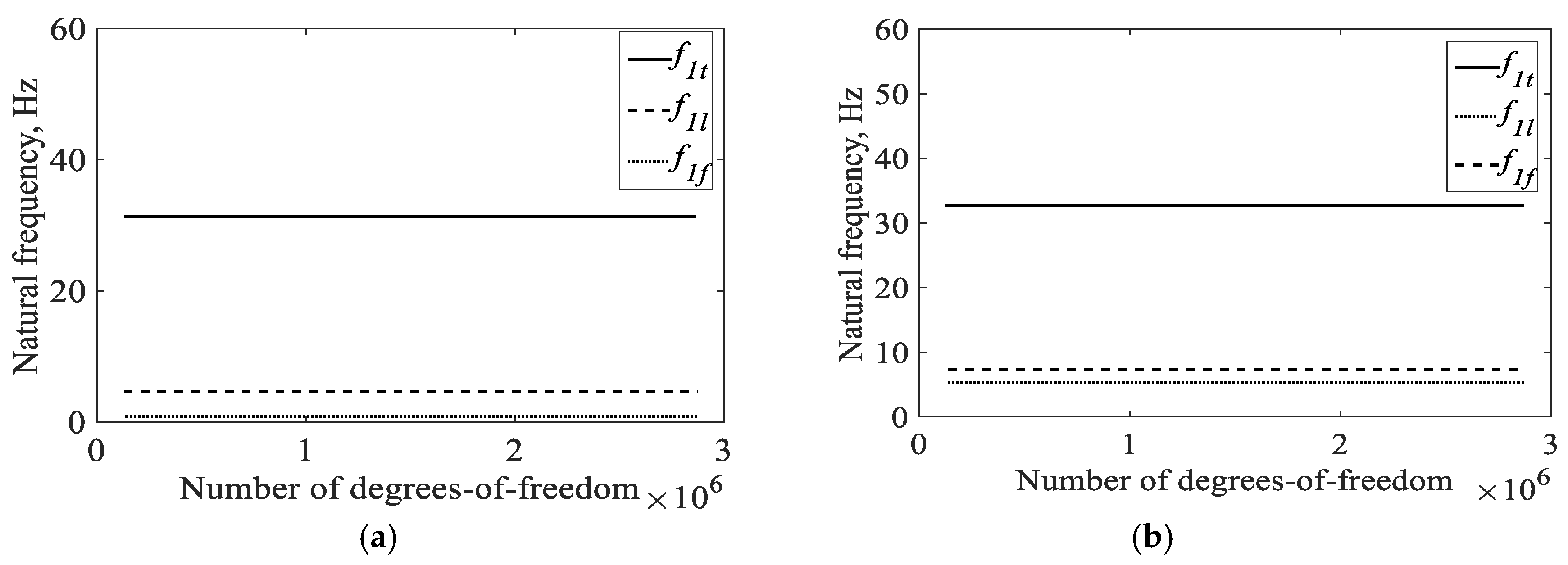

4.1.1. Convergence Study

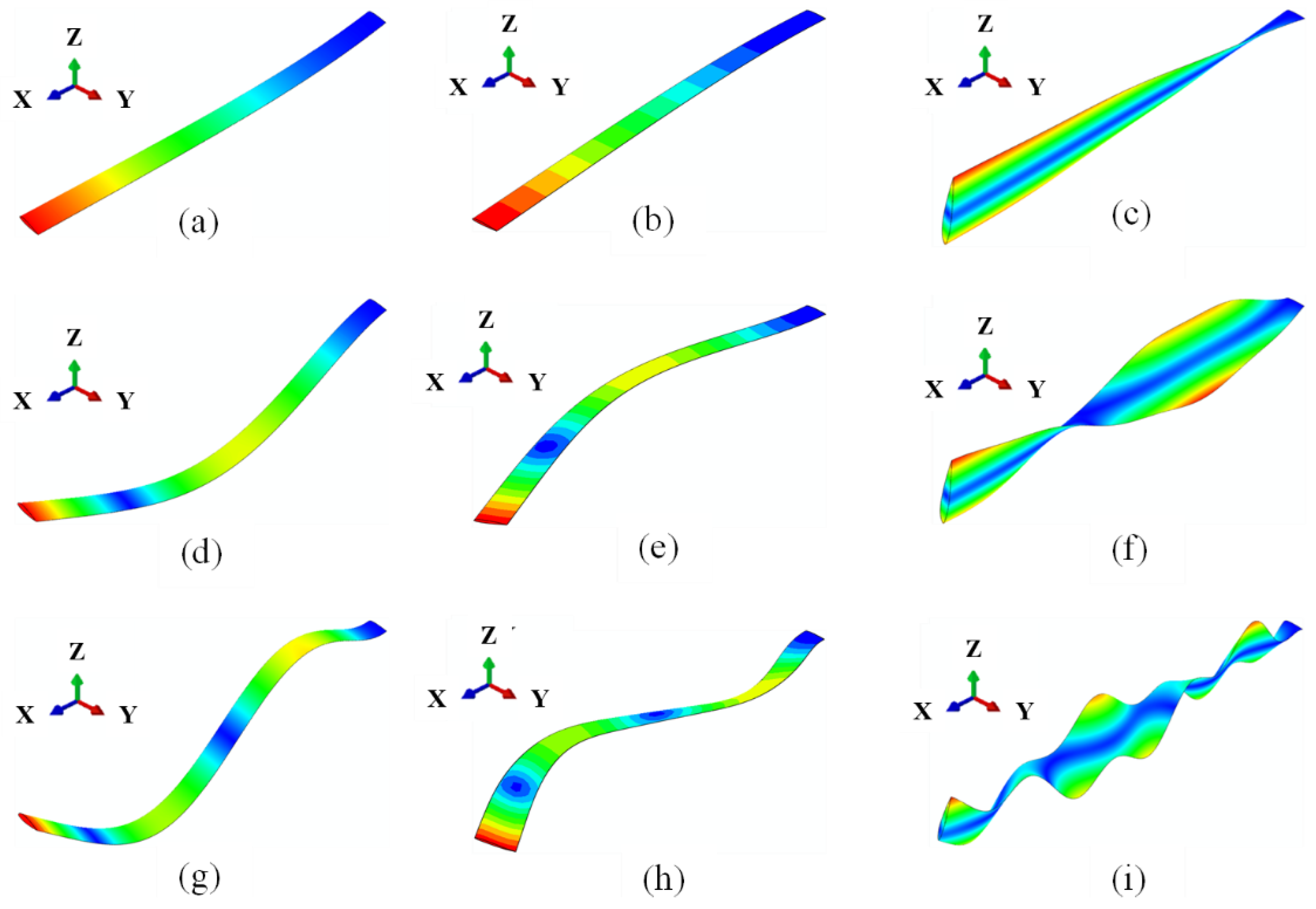

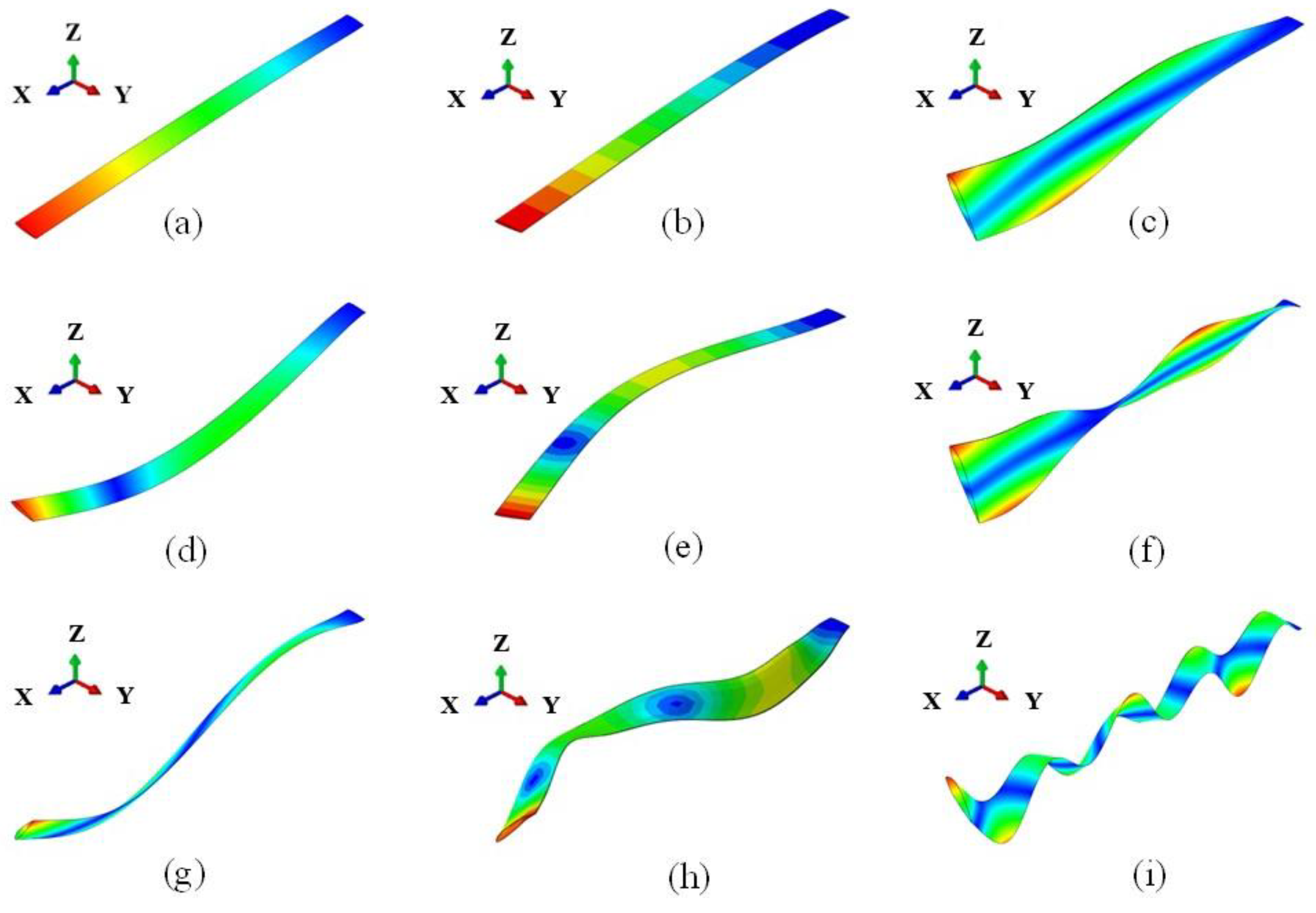

4.1.2. Natural Frequencies and Mode Shapes-Nonrotating Case

4.1.3. Natural Frequencies and Mode Shapes-Rotating Case

4.2. Rotor-Blade Vibration Control

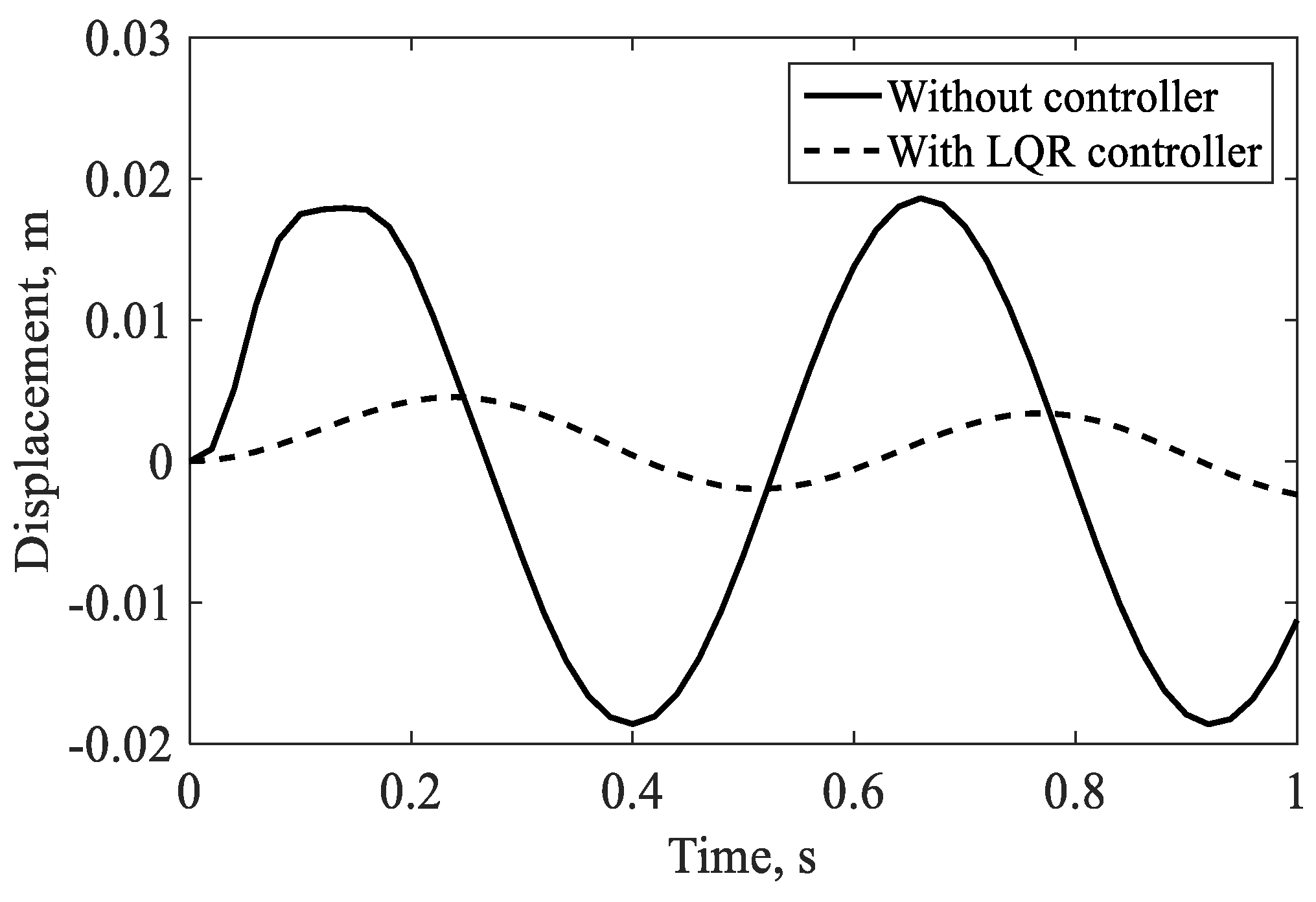

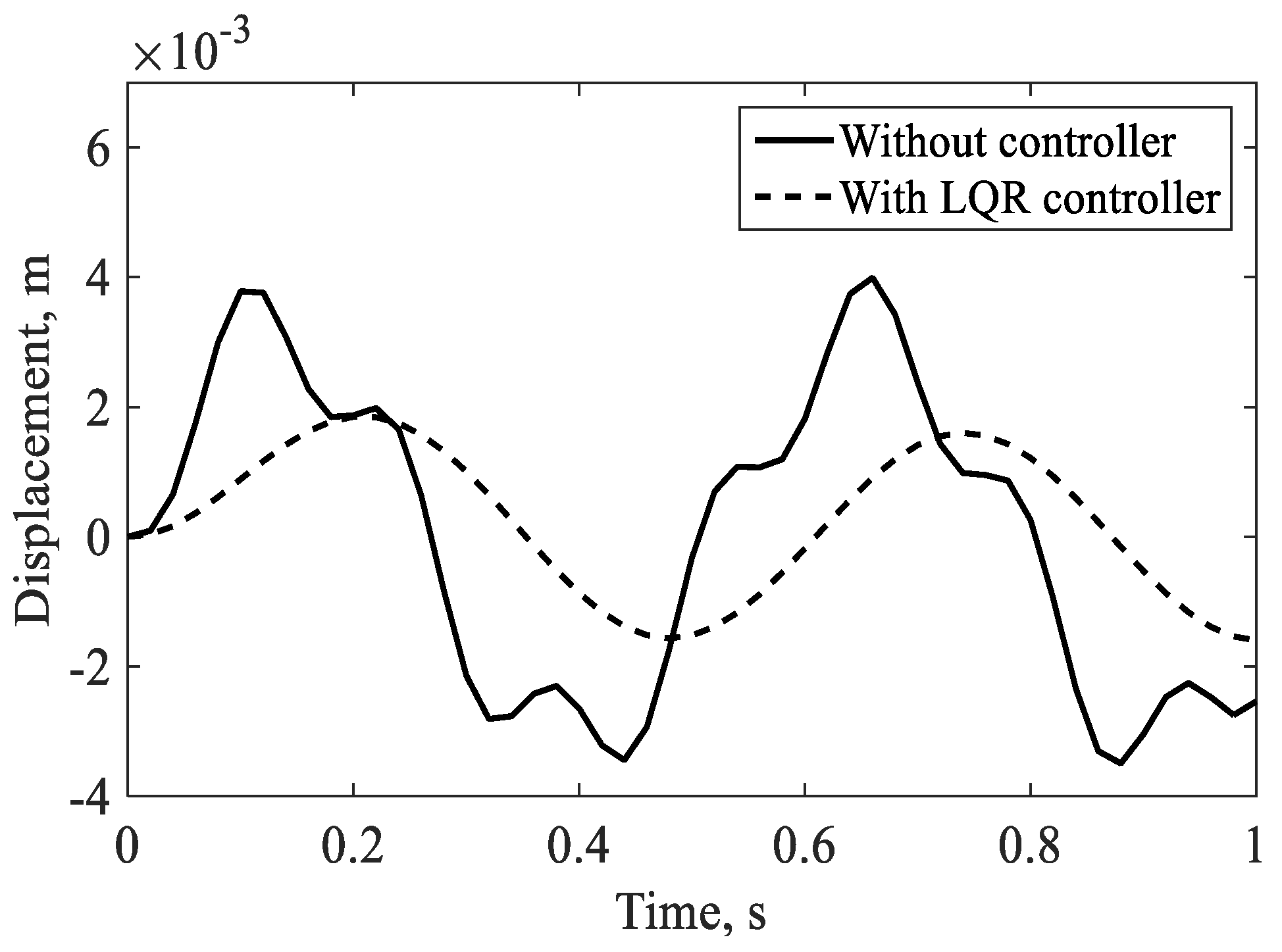

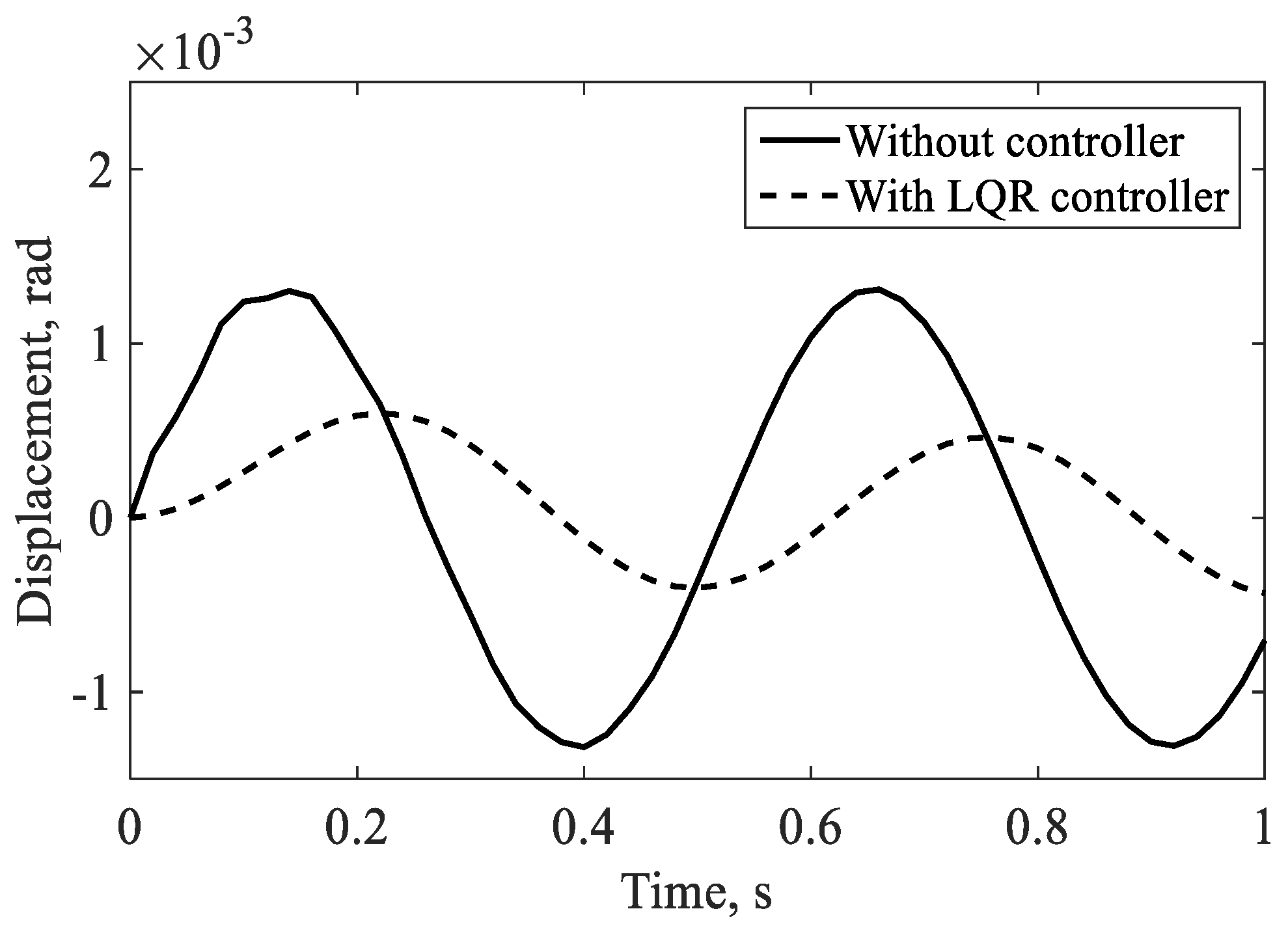

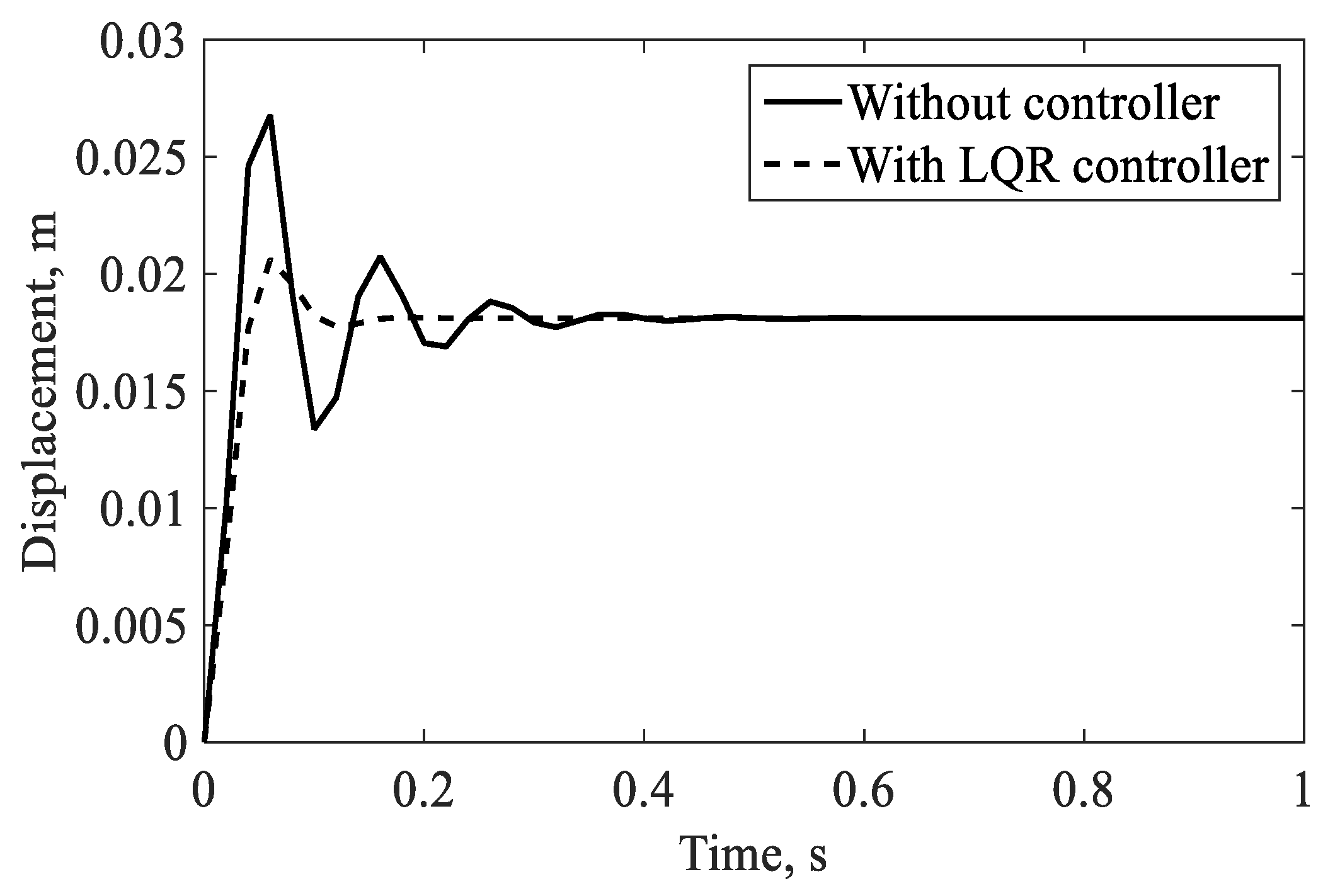

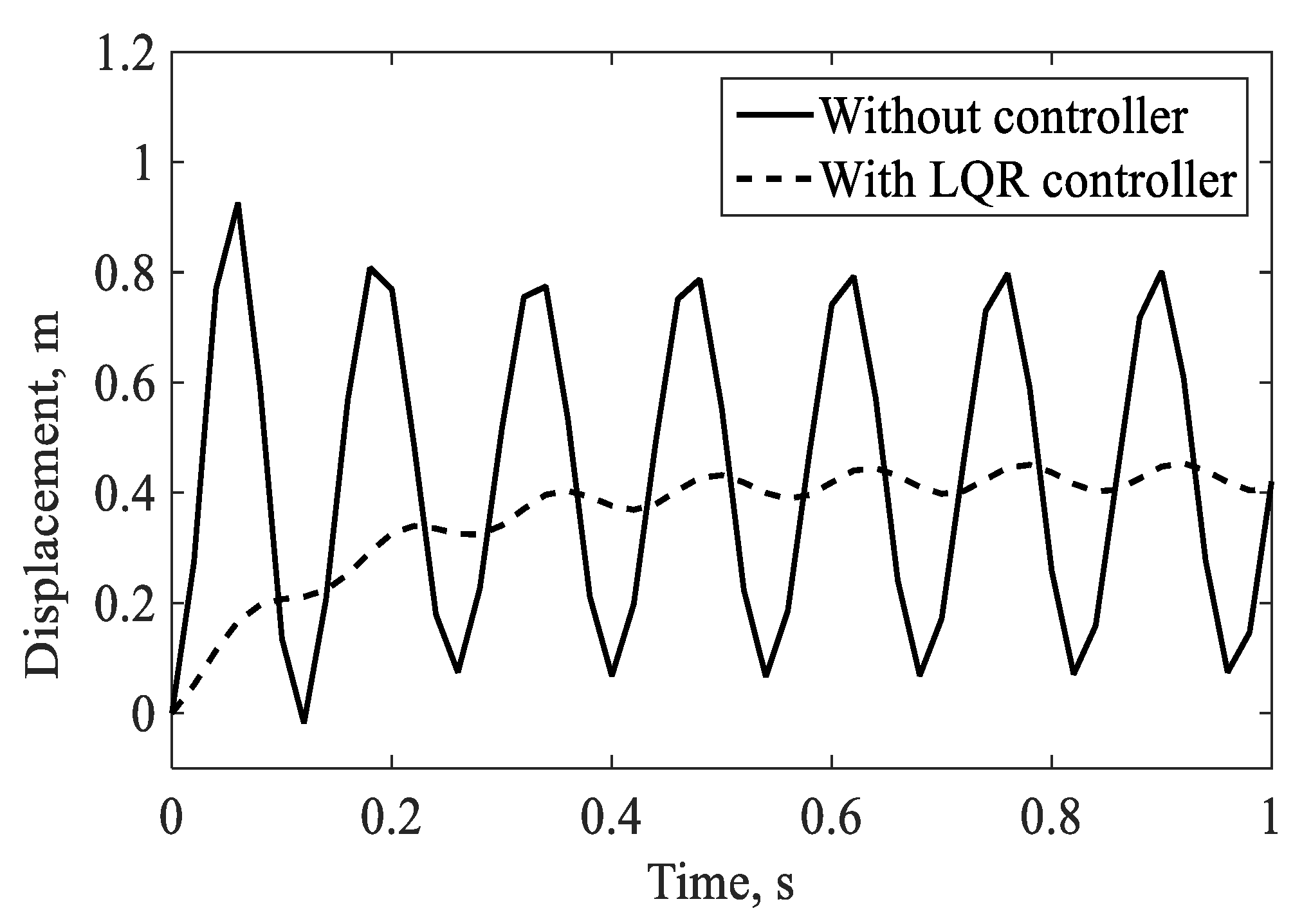

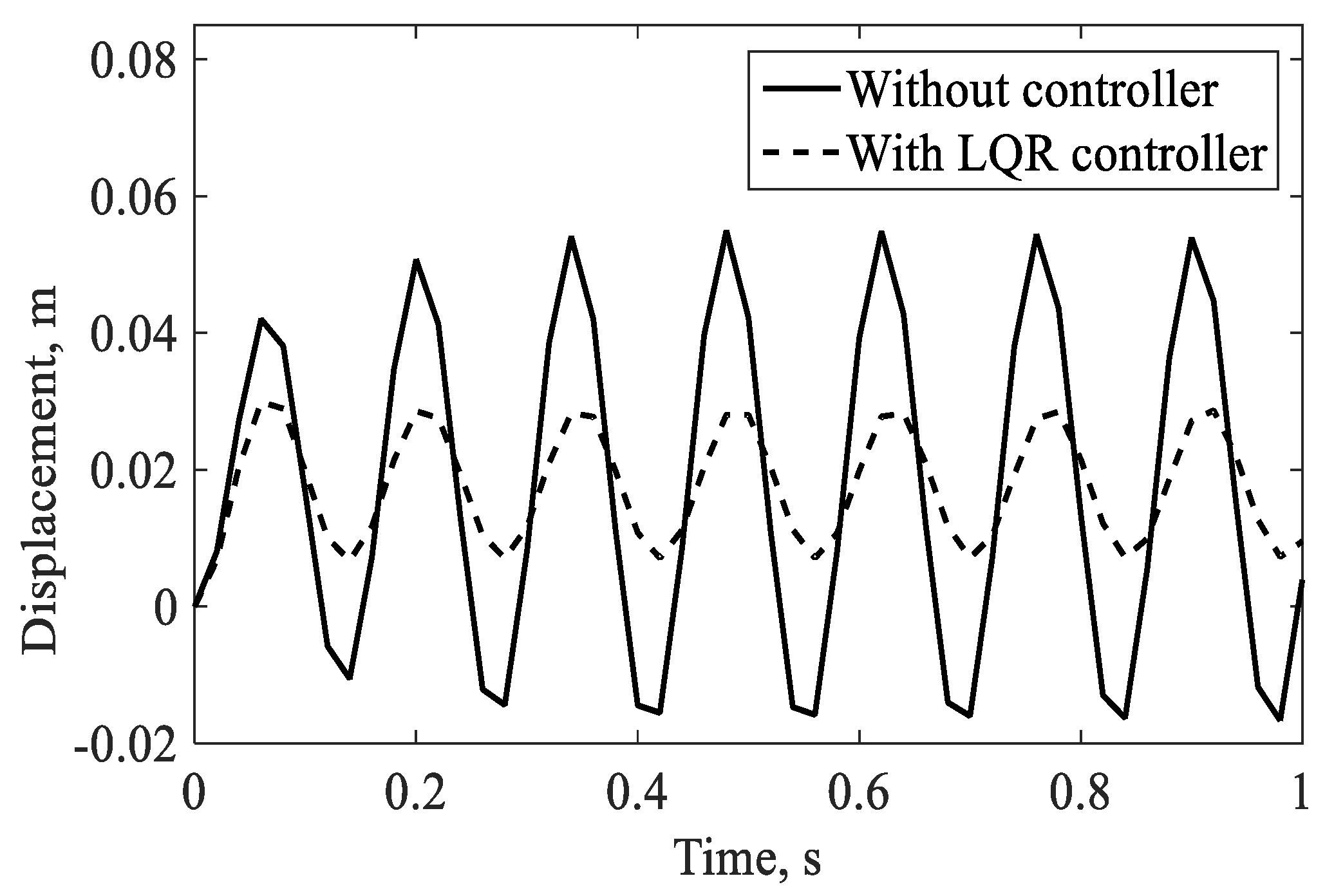

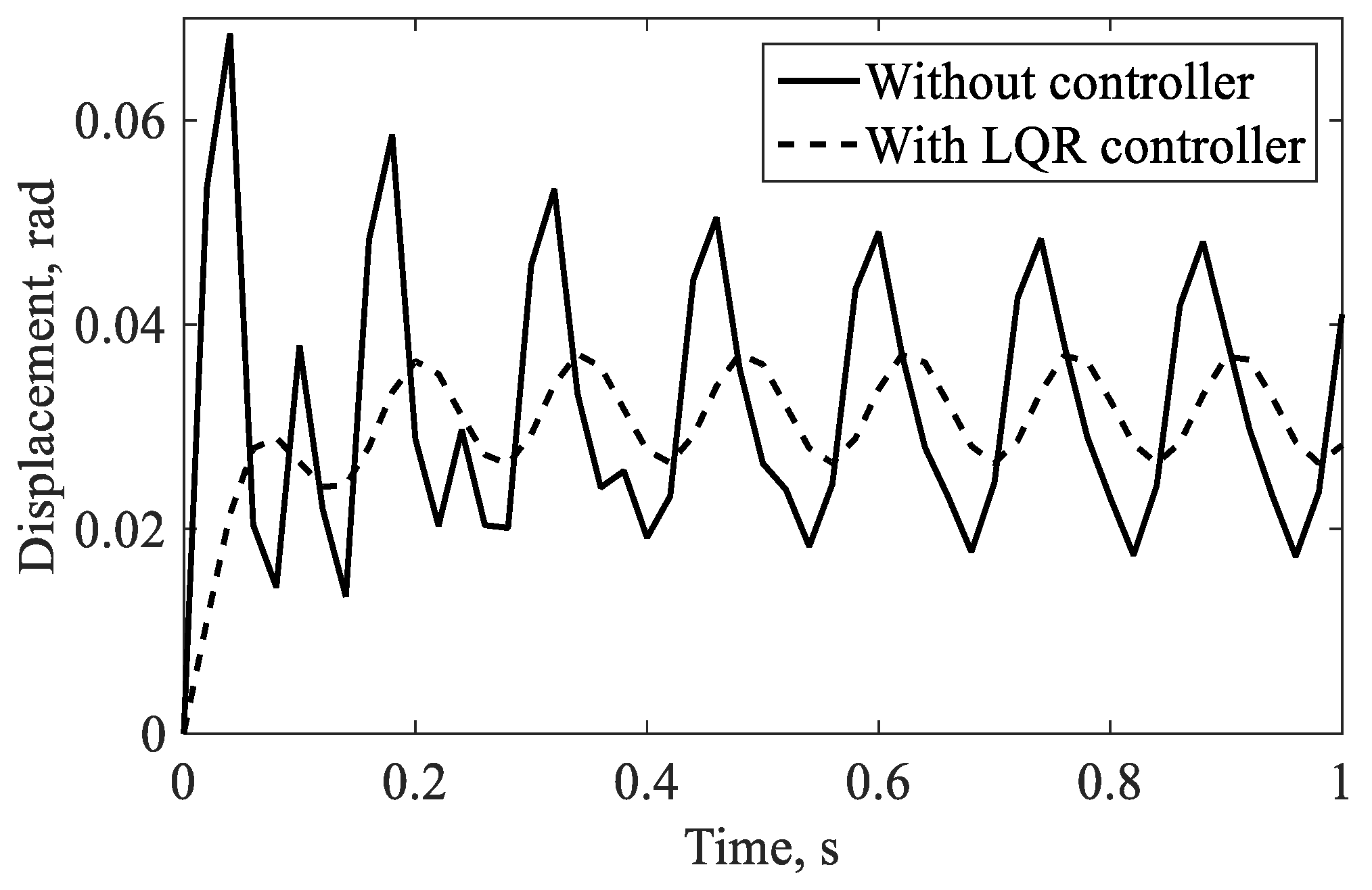

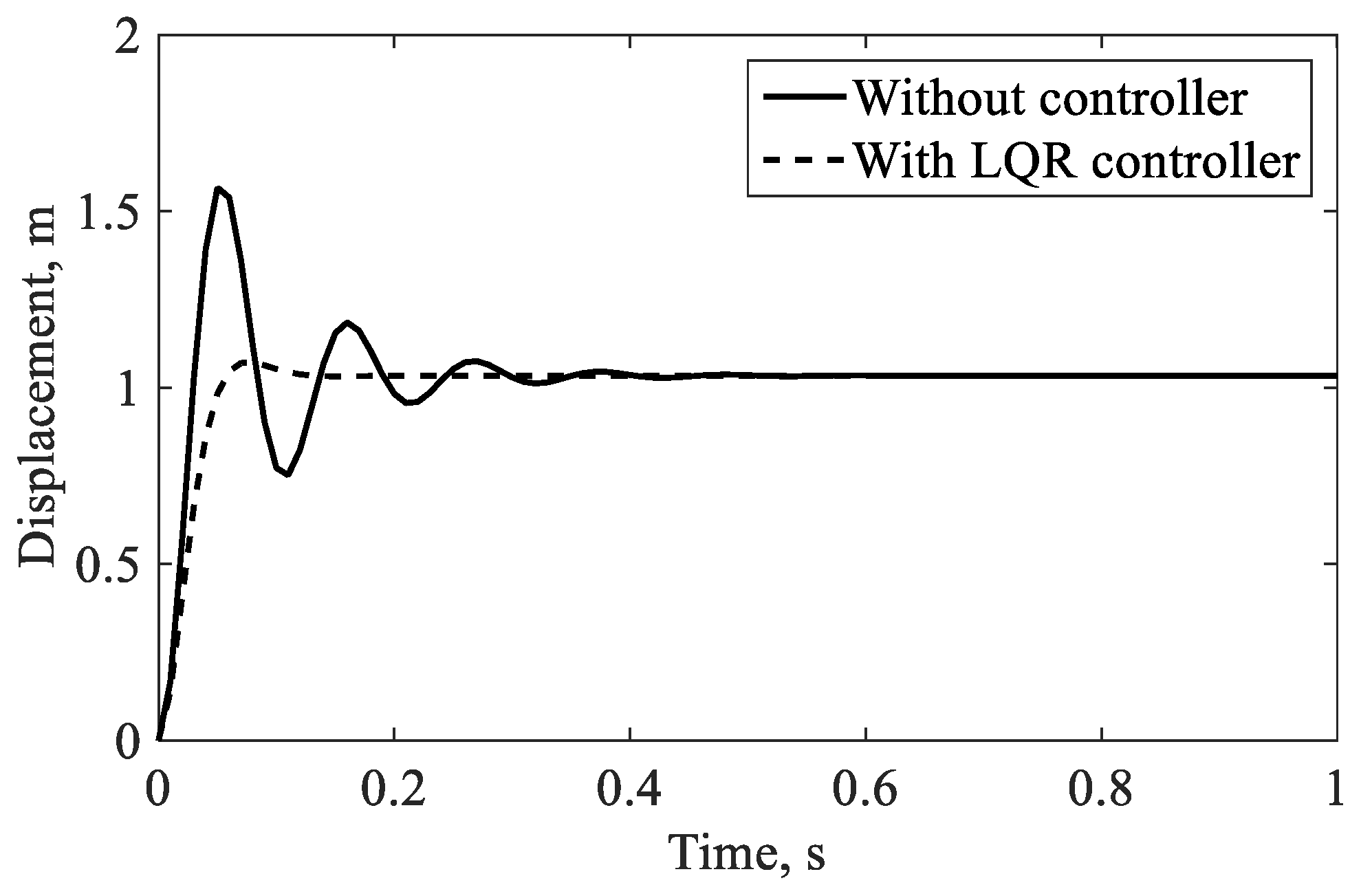

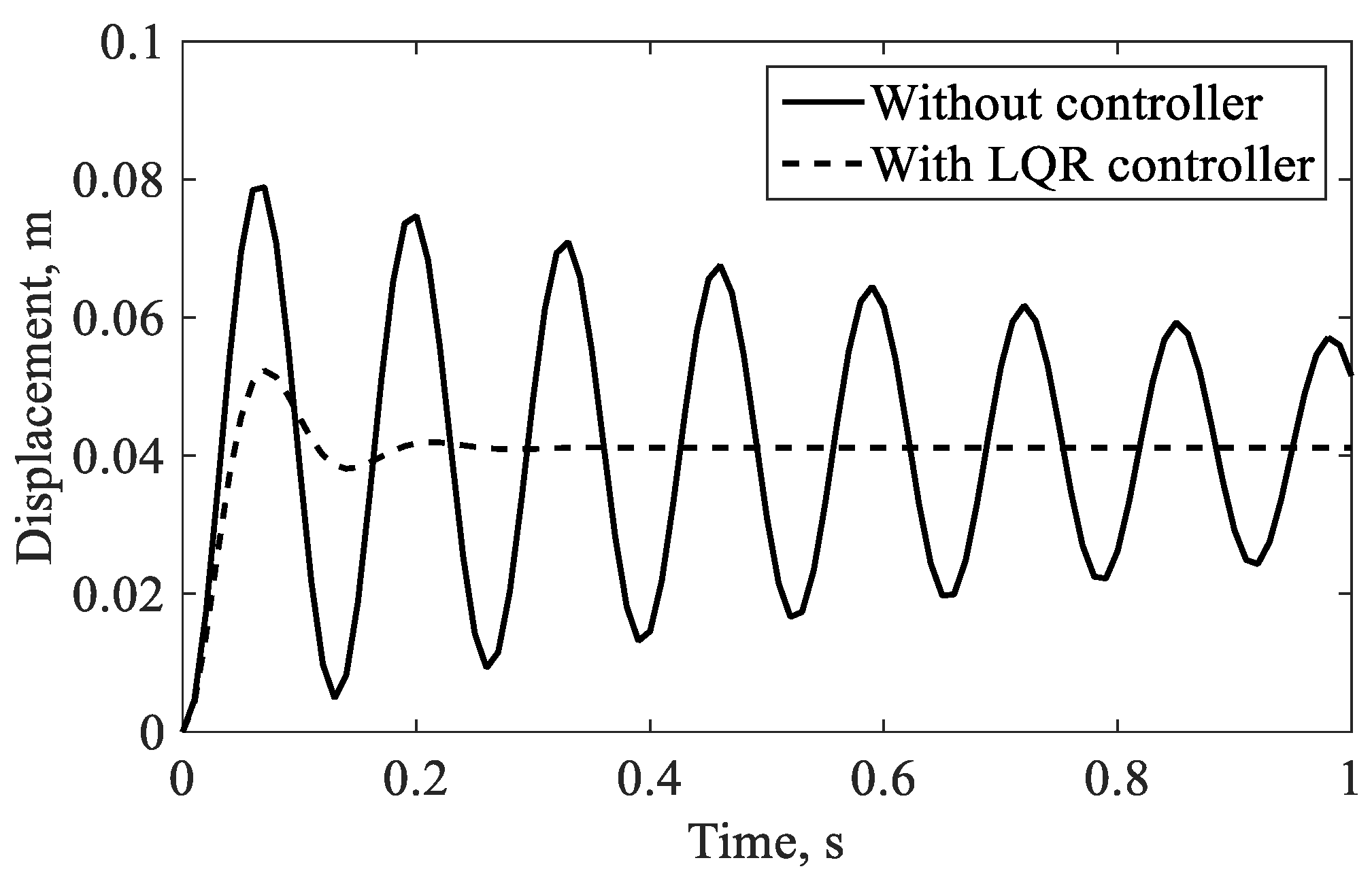

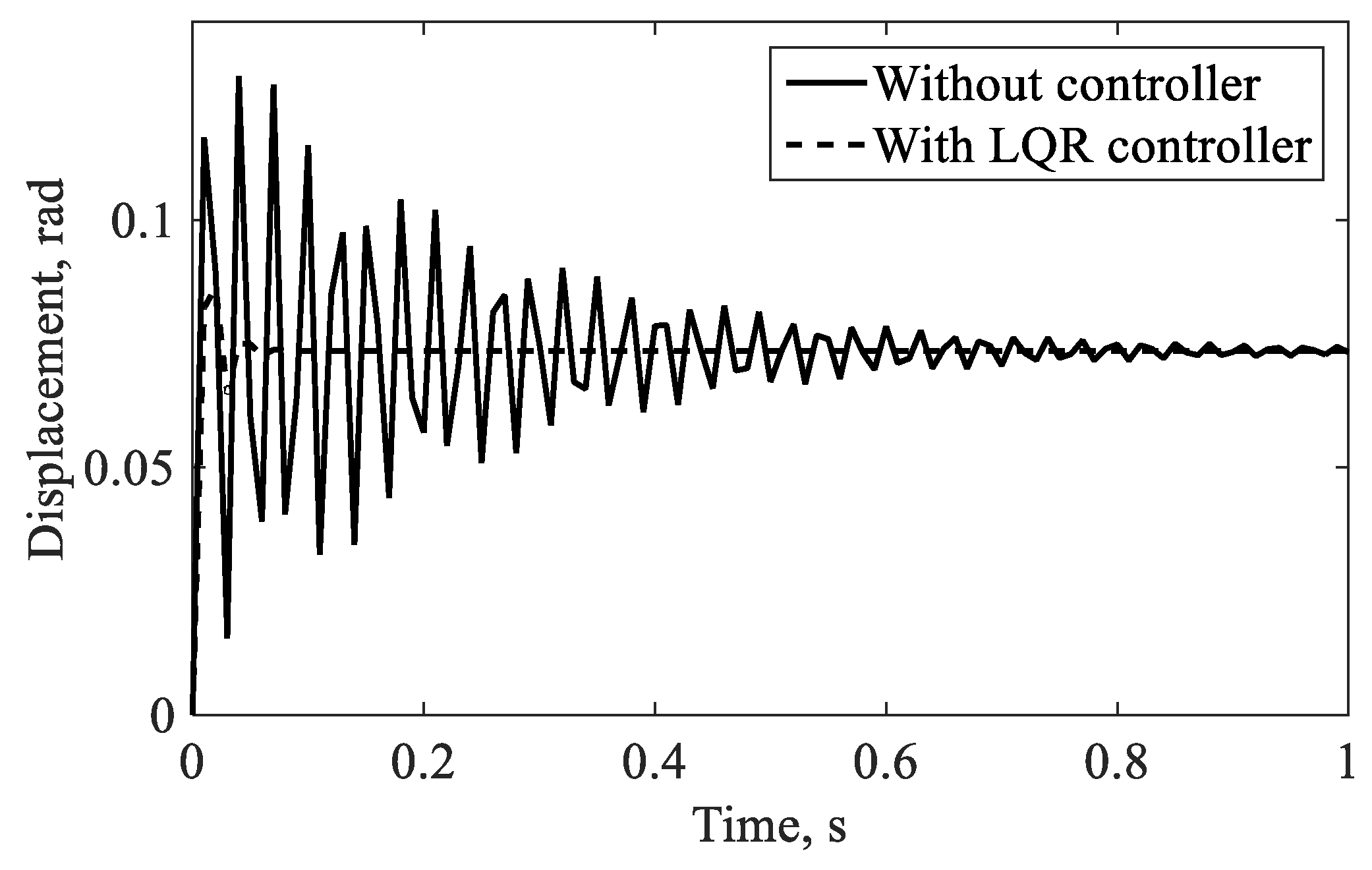

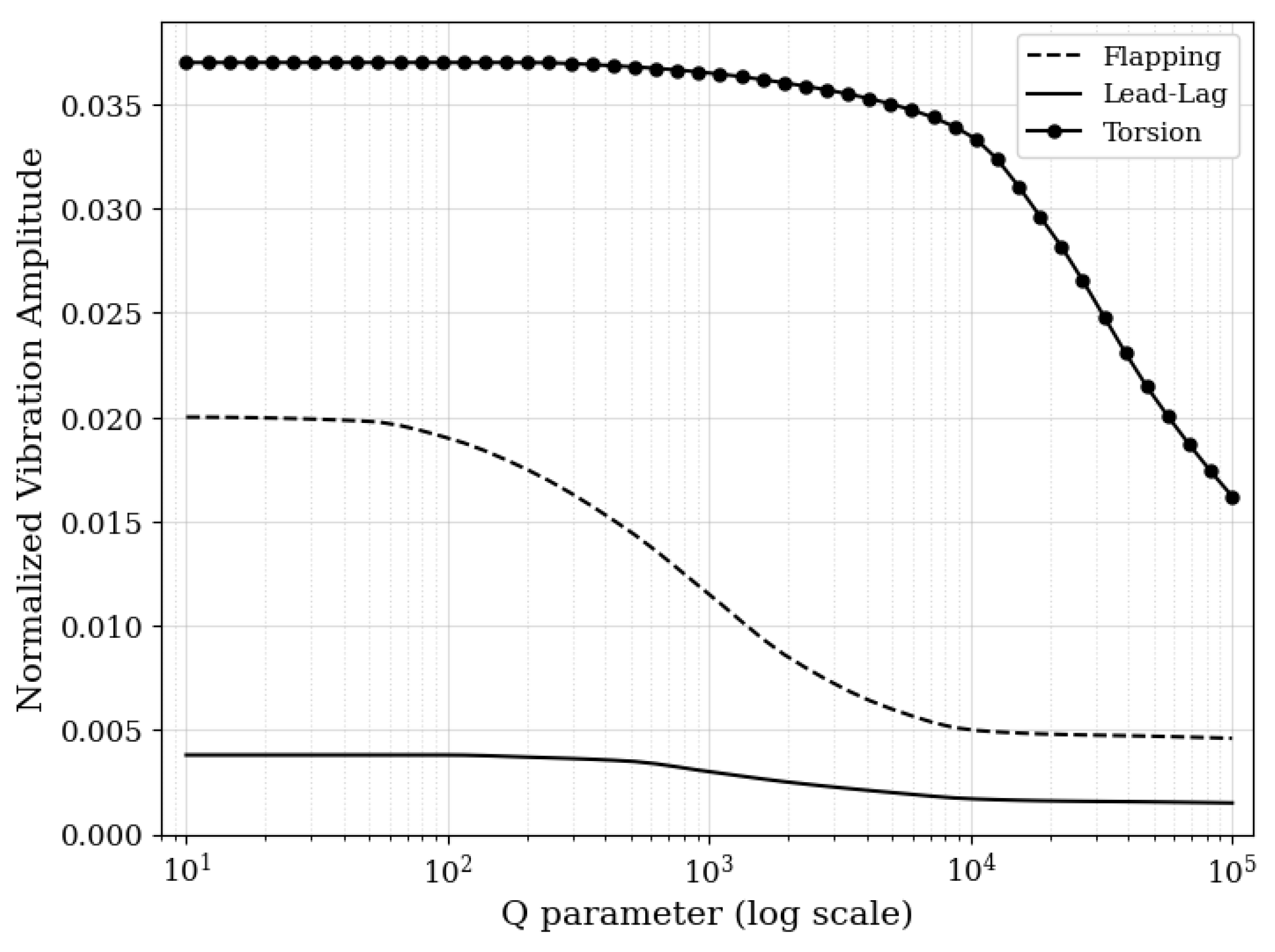

4.2.1. Controlled Response in the Hovering Flight

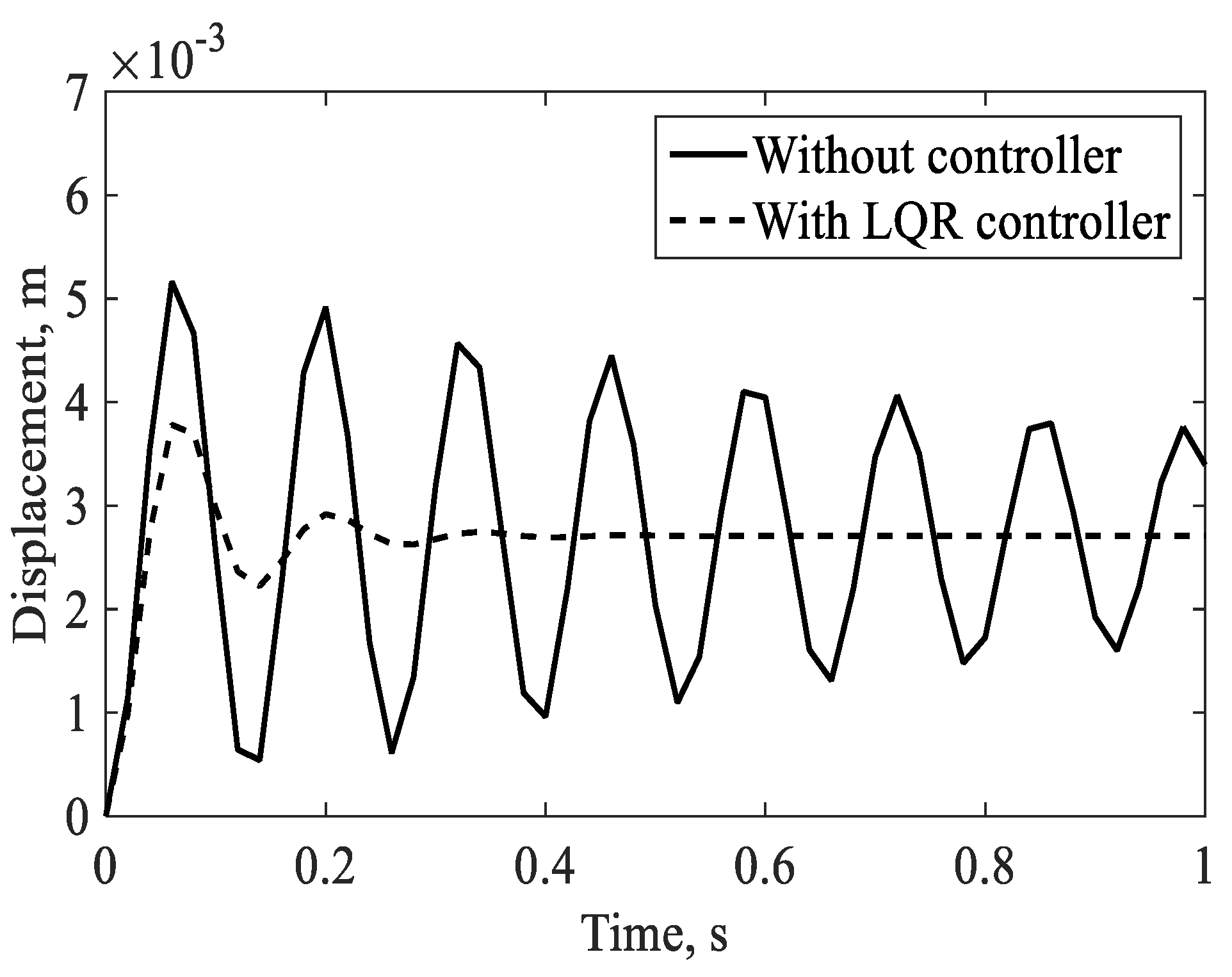

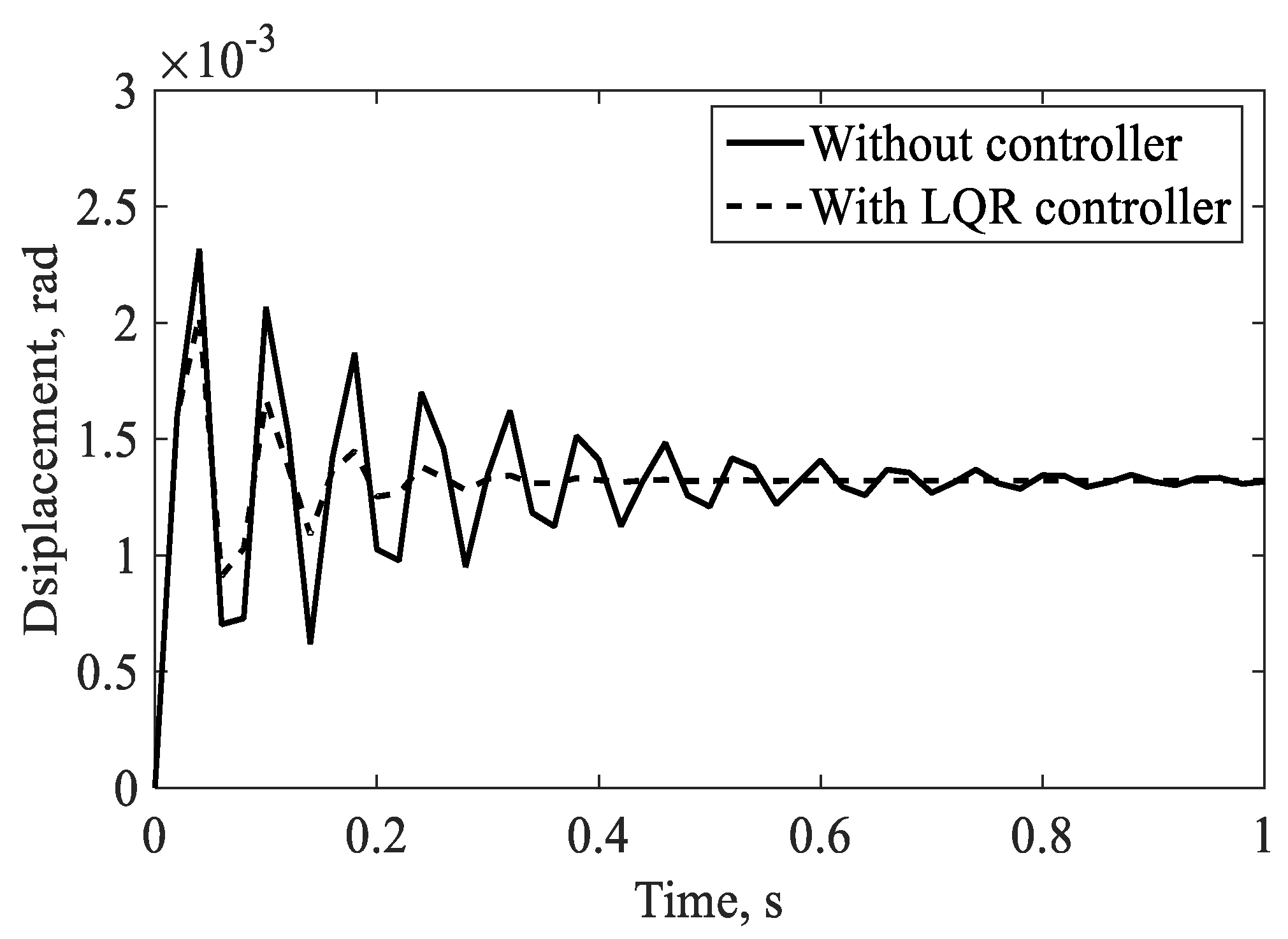

4.2.2. Controlled Response in the Forward Flight

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| , | time-invariant matrices |

| cross-sectional area | |

| , | cross-sectional area of composite core, shell |

| , | cross-sectional area of Honeycomb structure, Rohacell foam |

| , , , | elements of the extensional stiffness matrix of a composite laminate |

| extensional stiffness of composite shell per unit width | |

| , | time-invariant matrices |

| out-of-plane bending stiffness with respect to neutral axis | |

| overall drag force | |

| , | out-of-plane, in-plane bending stiffness with respect to global axis, global axis through the shear center |

| , | out-of-plane, in-plane bending stiffness with respect to axis, axis |

| torsional stiffness about the shear center/elastic axis/global axis | |

| , | elastic modulus of composite shell in fiber direction, transverse direction |

| , | elastic modulus of the isotropic Honeycomb core, Rohacell core |

| , | equivalent extensional elastic modulus of composite shell, inner core |

| , | nth generalized force for in-plane/lead-lag, out-of-plane/flapping motion |

| in-plane shear modulus | |

| , | equivalent shear modulus of the composite core, the composite shell |

| identity matrix | |

| area moment of inertia with respect to neutral axis | |

| , | area moment of inertia of composite core, shell with respect to neutral axis |

| area moment of inertia with respect to principal centroidal axis | |

| , | area moment of inertia about the , axis |

| quadratic cost function | |

| state feedback controller gain matrix | |

| overall lift force | |

| pitching moment | |

| nth generalized moment for torsional motion | |

| , | bending moment about axis, axis |

| positive semi-definite unique matrix, weight matrices for state and inputs | |

| , | weighting matrix, torque about the elastic axis |

| weighting matrix | |

| , | shear force along axis, axis |

| centrifugal tension in the rotor blade | |

| , , | normal mode, th normal mode, th normal mode for lead-lag motion of the rotor blade |

| forward speed of the helicopter | |

| , , | normal mode, th normal mode, th normal mode for flapping motion of the rotor blade |

| lift curve slope | |

| chord length of the airfoil | |

| drag coefficient | |

| , | ordinate of the point on the upper reference curve, lower reference curve |

| , | ordinate of the point on the outermost lower, outermost upper surface along axis from the centroid of the whole composite cross-section |

| , | difference between the abscissa, ordinate of points at the intersections of the common normal and outermost/reference surface of the composite shell |

| , | known coordinates of the points on the outermost surface of the composite shell |

| , | unknown coordinates of the points on the reference surface of the composite shell |

| lift coefficient | |

| pitching moment coefficient | |

| distance between the neutral axis and centroidal axis | |

| , , | empirically derived coefficients |

| distance of the centroidal axis measured from axis | |

| radial distance between the outermost surface and reference surface of the composite shell | |

| distance between the neutral axis and centroidal axis of the cross-section of the composite core | |

| distance between the neutral axis and centroidal axis of the cross-section of the composite shell | |

| distance between the centroid and shear center of the rotor blade | |

| distance between the root and the center of rotation of the helicopter rotor blade | |

| natural frequency in Hz | |

| in-plane bending/drag force on helicopter rotor blade per unit length along axis | |

| out-of-plane bending/lift force on helicopter rotor blade per unit length along axis | |

| total thickness of the composite shell | |

| , | distance of the topmost point, the bottommost point, from the neutral axis of the proposed cross-section |

| complex number | |

| length of the helicopter rotor blade | |

| mass per unit length of the blade | |

| , | empirically derived coefficients |

| pitching/torsional moment on the helicopter rotor blade per unit length about axis | |

| generalized time coordinate for th mode of vibration | |

| reference signal | |

| , | arc length of the lower reference curve, upper reference curve of the composite shell |

| Time | |

| input signal | |

| linear blade velocity parallel to the rotor disk plane | |

| in-plane deflection due to lead-lag motion of helicopter rotor blade along y-axis | |

| out-of-plane deflection due to flapping motion of helicopter rotor blade along z-axis | |

| , | position measured along axis, state vector |

| , | position measured along axis, output vector |

| , | principal axes through the centroid of the proposed composite cross-section |

| position measured along the axis of the helicopter rotor blade | |

| normal mode due to torsional vibration of the helicopter rotor blade | |

| angular velocity of the helicopter rotor blade in rad/s | |

| total blade twist angle at any location in the blade section prior to any deformation | |

| angle of attack | |

| slope angle for the outermost surface of the composite shell | |

| angle of twist between center of rotation and tip of helicopter rotor blade | |

| torsional constant of a thin cross section | |

| damping ratio | |

| , , | damping ratio in flapping, lead-lag, and torsional motion |

| torsional deflection of the helicopter rotor blade about axis | |

| polar mass radius of gyration about the elastic axis | |

| , | mass radius of gyration about neutral axis, about axis normal to chord through shear center |

| , | Poisson’s ratio, major Poisson’s ratio |

| , , , | density of air, honeycomb core, rohacell core, composite shell |

| solidity ratio of the rotor blade | |

| azimuth angle | |

| , , | natural frequency, th natural frequency, th natural frequency for rotating blade in rad/s, |

| differentiation with respect to | |

| differentiation with respect to |

References

- Pulok, M.K.H. and Chakravarty, U.K., Modal Characterization, Aerodynamics, and Gust Response of an Electroactive Membrane. AIAA Journal, 2022. 60(5): p. 3194-3205. [CrossRef]

- Lei, R. and Chen, L., Dual power non-singular fast terminal sliding mode fault-tolerant vibration-attenuation control of the flexible space robot subjected to actuator faults. Acta Mechanica, 2024. 235(2): p. 1255-1269. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. and Chen, M., Computational fluid dynamics trimming of helicopter rotor in forward flight. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2020. 12(5): p. 1687814020925252. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari-Jovin, S., Firouz-Abadi, R.D., and Roshanian, J., L1 adaptive aeroelastic control of an unsteady flapped airfoil in the presence of unmatched nonlinear uncertainties. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2024. 578: p. 118334.

- Kamalirad, A.M. and Fotouhi, R., Vibration Control of a Two-Link Manipulator Using a Reduced Model. Vibration, 2025. 8(4): p. 58. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.Y., et al., A finite-element model for piezoelectric composite laminates. Smart Materials and Structures, 1997. 6(5): p. 583. [CrossRef]

- Chuaqui, T.R., Roque, C.M., and Ribeiro, P., Active vibration control of piezoelectric smart beams with radial basis function generated finite difference collocation method. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures, 2018. 29(13): p. 2728-2743. [CrossRef]

- Selim, B.A., Zhang, L.W., and Liew, K.M., Active vibration control of CNT-reinforced composite plates with piezoelectric layers based on Reddy’s higher-order shear deformation theory. Composite Structures, 2017. 163: p. 350-364. [CrossRef]

- Vindigni, C.R., Orlando, C., and Milazzo, A., Computational Analysis of the Active Control of Incompressible Airfoil Flutter Vibration Using a Piezoelectric V-Stack Actuator. Vibration, 2021. 4(2): p. 369-394. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.G., Zhang, L.W., and Liew, K.M., Active vibration control of CNT-reinforced composite cylindrical shells via piezoelectric patches. Composite Structures, 2016. 158: p. 92-100. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, C., Active rotor control for helicopters: motivation and survey on higher harmonic control. CEAS Aeronautical Journal, 2011. 1(1): p. 3-22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., et al., Fuzzy Neural Network PID Control Used in Individual Blade Control. Aerospace, 2023. 10(7): p. 623. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S., et al., Vibration and Performance Analyses Using Individual Blade Pitch Controls for Lift-Offset Rotors. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2019. 2019(1): p. 9589415. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., et al., Reducing Helicopter Vibration Loads by Individual Blade Control with Genetic Algorithm. Machines, 2022. 10(6): p. 479. [CrossRef]

- Küfmann, P.M., et al., The First Wind Tunnel Test of the Multiple Swashplate System: Test Procedure and Principal Results. Journal of the American Helicopter Society, 2017. 62(4): p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Jacklin, S.A., et al., Investigation of a Helicopter Individual Blade Control (IBC) System in Two Full-Scale Wind Tunnel Tests: Volume I in Technical Publication. 2020, NASA Ames Research Center. p. 1-214.

- Jacklin, S.A., et al., Investigation of a Helicopter Individual Blade Control (IBC) System in Two Full-Scale Wind Tunnel Tests: Volume II—Tabulated Data in Technical Publication. 2020, NASA Ames Research Center. p. 1-690.

- Chia, M.H., et al., An Efficient Approach for the Simulation and On-Blade Control of Helicopter Noise and the Impact on Vibration. Journal of the American Helicopter Society, 2017. 62(4): p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Study on the Vibration Characteristics of Composite Rotor Blades in Humid Environment. Polymer Composites, 2025: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tian, S., et al., Structural Design Optimization of Composite Rotor Blades with Strength Considerations, in AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum.

- Amoozgar, M.R., Shaw, A.D., and Friswell, M.I., The effect of curved tips on the dynamics of composite rotor blades. Aerospace Science and Technology, 2020. 106: p. 106197. [CrossRef]

- Taymaz, H.A., Helicopter rotor blade vibration reduction with optimizing the structural distribution of composite layers. Journal of Measurements in Engineering, 2022. 10(1): p. 27-37. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P., Dynamic Response of a Hingeless Helicopter Rotor Blade at Hovering and Forward Flights. 2018, University of New Orleans: Theses and Dissertations. p. 134.

- Sarker, P. and Chakravarty, U.K., On the dynamic response of a hingeless helicopter rotor blade. Aerospace Science and Technology, 2021. 115: p. 106741. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P., Theodore, C.R., and Chakravarty, U.K. Vibration Analysis of a Composite Helicopter Rotor Blade at Hovering Condition. in ASME 2016 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. 2016.

- Goulos, I., Pachidis, V., and Pilidis, P., Flexible rotor blade dynamics for helicopter aeromechanics including comparisons with experimental data. The Aeronautical Journal, 2015. 119(1213): p. 301-342. [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, V.V. and Morozov, E.V., Advanced Mechanics of Composite Materials and Structural Elements. 3 ed. 2013, United Kingdom: Elsevier. 832.

- Yu, A.M., et al., An improved model for naturally curved and twisted composite beams with closed thin-walled sections. Composite Structures, 2011. 93(9): p. 2322-2329. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.H., et al., Free-Vibration Analysis of Composite Beams. Journal of the American Helicopter Society, 1991. 36(3): p. 36-47.

- Hashemi, S.M. and Richard, M.J., Free vibrational analysis of axially loaded bending-torsion coupled beams: a dynamic finite element. Computers & Structures, 2000. 77(6): p. 711-724. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M., et al. Active Vibration Control of a Helicopter Rotor Blade by Using a Linear Quadratic Regulator. in ASME 2018 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. 2018.

- Leishman, J.G., Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics. 2 ed. 2016, USA: Cambridge University Press. 866.

- Johnson, W., Helicopter Theory. Revised ed. 1994, USA: Dover Publications. 1120.

- Sarker, P., Dynamic Response of a Hingeless Helicopter Rotor Blade at Hovering and Forward Flights, in Mechanical Engineering. 2018, University of New Orleans: Thesis and Dissertations. p. 134.

- Tsushima, N. and Su, W., A study on adaptive vibration control and energy conversion of highly flexible multifunctional wings. Aerospace Science and Technology, 2018. 79: p. 297-309. [CrossRef]

- Su, W. and Spencer, H.J., Active Camber Control of Flexible Airfoils using Artificial Hair Sensors, in AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference. 2017.

- Brahem, M. and Chouchane, M., GA tuned LQR controller for active vibration control of a rotor bearing system using piezoelectric actuators. Engineering Research Express, 2024. 6(2): p. 025562. [CrossRef]

- Camino, J.F. and Santos, I.F., A periodic linear–quadratic controller for suppressing rotor-blade vibration. Journal of Vibration and Control, 2019. 25(17): p. 2351-2364. [CrossRef]

| Properties | Value | Properties | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2100 kg/m3 | 0.28 | ||

| 45 GPa | 5.5 GPa | ||

| 12 GPa | 0.002 m |

| Rohacell | Honeycomb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Properties | Value | Properties | Value |

| 75 kg/m3 | 48 kg/m3 | ||

| 105 MPa | 128 MPa | ||

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blade length | 4.61 m | Rotor speed | 44.5 rad/s |

| Chord length | 0.27 m | Blade root offset | 0.30 m |

| Rotor disk area | 75.73 m2 | Number of blades | 4 |

| Blade tip speed | 218.50 m/s | Airfoil | NACA 23012 |

| Fundamental Natural Frequencies, Hz | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| This study (MGM) | Experimental study | % Error | |

| 7.76 | 7.93 | 2.19 | |

| 5.65 | 5.18 | 8.31 | |

| 29.37 | 25.22 | 14.13 | |

| Mode | This Study (Hovering, Periodic Excitation) | Camino and Santos [38] (Periodic LQR, Full-State Feedback) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flapping | 0.020 m−0.0046 m (77% reduction) | Primary bending mode: 70–80% reduction | Within same range |

| Lead–Lag | 0.0038 m−0.0016 m (58% reduction) | Secondary bending mode: 50–65% reduction | Similar range |

| Torsion | 0.037 rad−0.012 rad (68% reduction) | Not reported | Not applicable |

| Trend with | Higher → greater attenuation, higher control effort | Higher → greater attenuation, higher actuator demand | Identical qualitative behavior |

| Natural Frequencies, Hz | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | This study (MGM) | FEA | This study (MGM) | FEA | This study (MGM) | FEA |

| = 1 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 4.74 | 4.61 | 29.37 | 31.36 |

| = 2 | 4.33 | 4.04 | 29.72 | 28.73 | 88.03 | 93.93 |

| = 3 | 12.13 | 11.27 | 83.22 | 79.48 | 146.60 | 157.10 |

| % Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | |||

| = 1 | 5.79 | 2.74 | 6.77 |

| = 2 | 6.69 | 3.33 | 6.47 |

| = 3 | 7.08 | 4.49 | 7.16 |

| Natural Frequencies, Hz | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | This study (MGM) | FEA | This study (MGM) | FEA | This study (MGM) | FEA |

| = 1 | 7.76 | 7.27 | 5.65 | 5.42 | 29.37 | 32.88 |

| = 2 | 18.53 | 18.06 | 34.05 | 32.95 | 88.03 | 95.45 |

| = 3 | 32.29 | 30.17 | 88.16 | 83.96 | 146.62 | 161.02 |

| % Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| = 1 | 6.32 | 4.07 | 10.67 |

| = 2 | 2.54 | 3.23 | 7.77 |

| = 3 | 6.57 | 4.76 | 8.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).