1. Introduction

Lung cancer is with 1.8 million deaths the leading cause of cancer related deaths [

1]. As the data indicate, lung carcinoma is one of the top aggressive cancers with poor outcomes. Almost half of the non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients have stage IV at initial diagnosis [

2]. The 5-year survival rate persists at a very low level [

3] and roughly 75% of patients diagnosed with advanced lung cancer have a bad prognosis [

4]. Chemotherapy only achieves median survival rates up to 14 months [

5]. The approval of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) led to a decrease of mortality and transformed the landscape of NSCLC treatment and prognosis [

6,

7]. According to phase III clinical trials, EGFR-TKIs are superior to chemotherapy regarding to prolonging progression-free survival (PFS) [

8,

9] and overall survival (OS) [

10].

EGFR mutations are the second most prevalent oncogenic drivers in NSCLC. The most common activating mutations (exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation) comprise the vast majority of EGFR mutations (80-85%), whereas uncommon mutations (Exon 18, 20, 19 and 21) are less frequent (15-20%) [

11,

12]. EGFR exon 20 insertions are the third most common genotype and occur in 1-10% of NSCLC patients [

13]. Since most of the patients with EGFR positive NSCLC carry either an exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R point mutation, data of uncommon EGFR genotypes are lacking[

14].

Common mutations are defined as predictors for good clinical response to EGFR-TKIs [

15]. As reported by previous studies, NSCLC patients with exon 19 deletion showed better OS and PFS than patients with L858R mutation [

16,

17]. Based on a meta-analysis, the EGFR mutation prevalence is higher in the Asian population (49.1%) than in Western countries (12.8%) [

7]. Therefore, data on survival outcome for patients in Europe harboring advanced NSCLC and treated with EGFR-TKIs in first-line palliative treatment have been lacking.

It is expected that the results of this prospective real-world study will bring more evidence for the use of EGFR-TKIs in first-line treatment in European advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations. Additionally, the comparison of the EGFR genotypes regarding survival outcome will deliver important prognostic information.

2. Materials and Methods

This observational cohort study evaluated real-world overall survival (rwOS) and real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) survival outcome of EGFR-positive advanced (stage IIIB or higher) NSCLC patients who were treated with TKIs in first-line regarding to EGFR subtype. The study followed a prospective design, all patients signed an Informed Consent Form (ICF). Patient data were collected at two high-volume clinics in Austria (Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Klinik Floridsdorf, Vienna; Department of Internal Medicine with Pulmonology, Klinik Ottakring, Vienna) between November 2020 and the last follow-up in February 2025. The EGFR mutation status was ascertained by next generation sequencing from tumor tissue (ThermoFisher OncomineTM Focus assay, Ion AmpliSeqTM lung cancer panel). The clinical characteristics and treatment data were predefined and retrospectively extracted from Longitudinal Analysis of LUng CAncer registry data (LALUCA, EK 20-061-VK, city of Vienna) [

18], which was implemented by the Karl Landsteiner Institute for Lung Research and Pulmonary Oncology in Vienna, Austria.

The survival analysis was estimated with Kaplan-Meier curves for rwOS and rwPFS. For both, rwOS and rwPFS, EGFR exon 19 deletion was compared with EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation and each of them with uncommon mutations in EGFR exon 18-21.

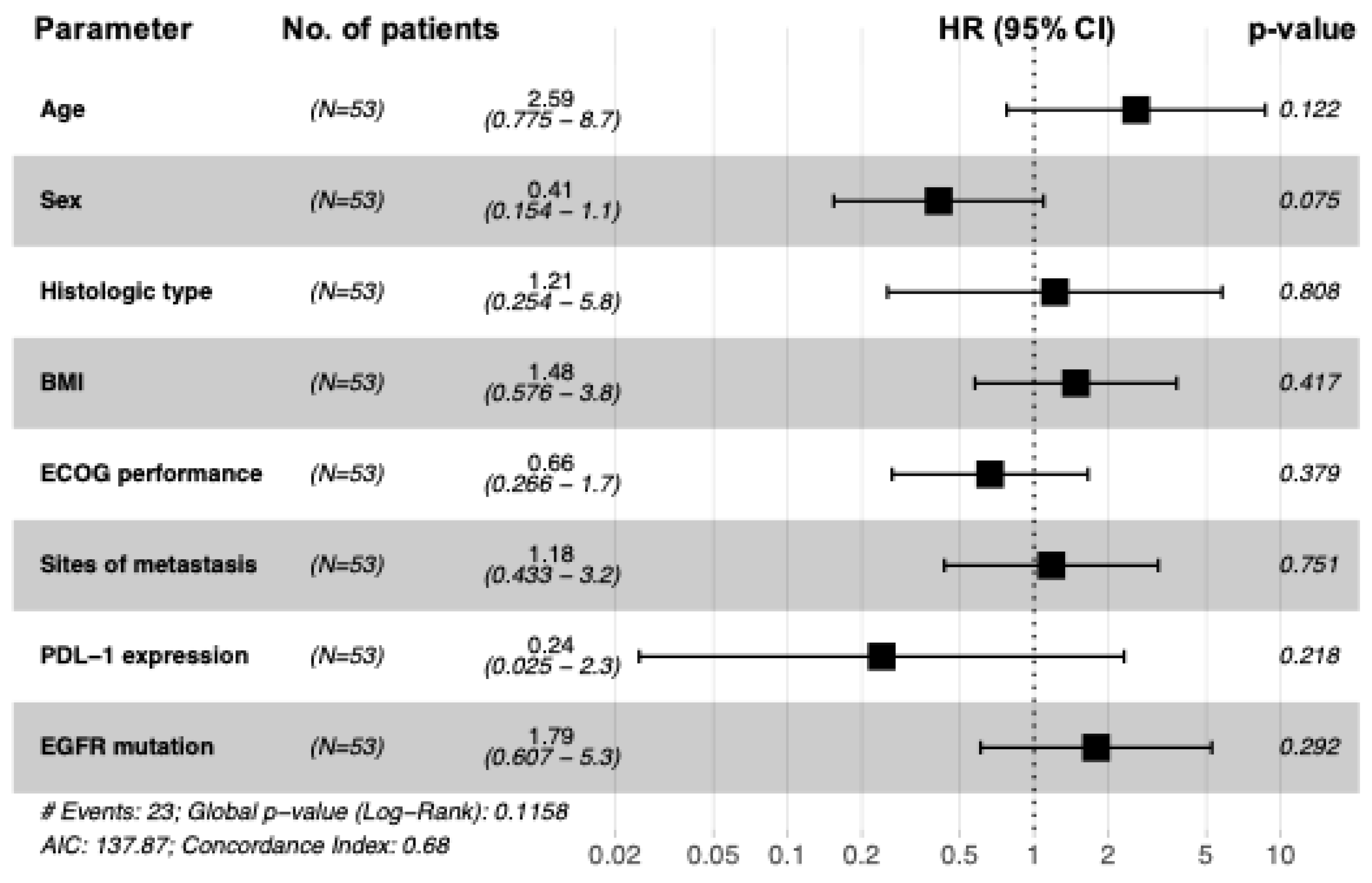

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was calculated to identify independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS, the results were additionally demonstrated in a forest plot for visualization.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in the open-source software R-4.4.1 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 30.0. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (n = 53), as well as the results of the corresponding group comparisons, were conducted with Fisher’s exact test.

The influence of TKIs as well as EGFR mutation subtypes upon OS and PFS in EGFR-positive NSCLC patients was estimated with Kaplan-Meier analyses. The potential differences between the survival curves were analyzed by using the log-rank test. OS was calculated from the start of first-line EGFR-TKI treatment to death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time between initiation of first-line EGFR-TKI treatment and disease progression or death. Participants who were alive were censored at the last date known alive. Cox proportional hazard regression model was assessed for the identification of possible independent prognostic factors of OS and PFS. For p-values, the established 5% α-level was used in order to draw conclusions about statistical significance.

3. Results

In total, 145 patients with an EGFR mutation (11%)were identified out of 1,267 patients (844 adenocarcinoma, 302 squamous cell carcinoma, 117 NOS or large cell carcinoma, 4 adenosquamous carcinoma) with NSCLC . The diagnosed EGFR variants were categorized into EGFR common und EGFR uncommon mutations, shown in

Table 1. Of the 145 patients with an EGFR mutation, 87 (60%) had a common EGFR mutation and 58 (40%) harbored an uncommon EGFR mutation.

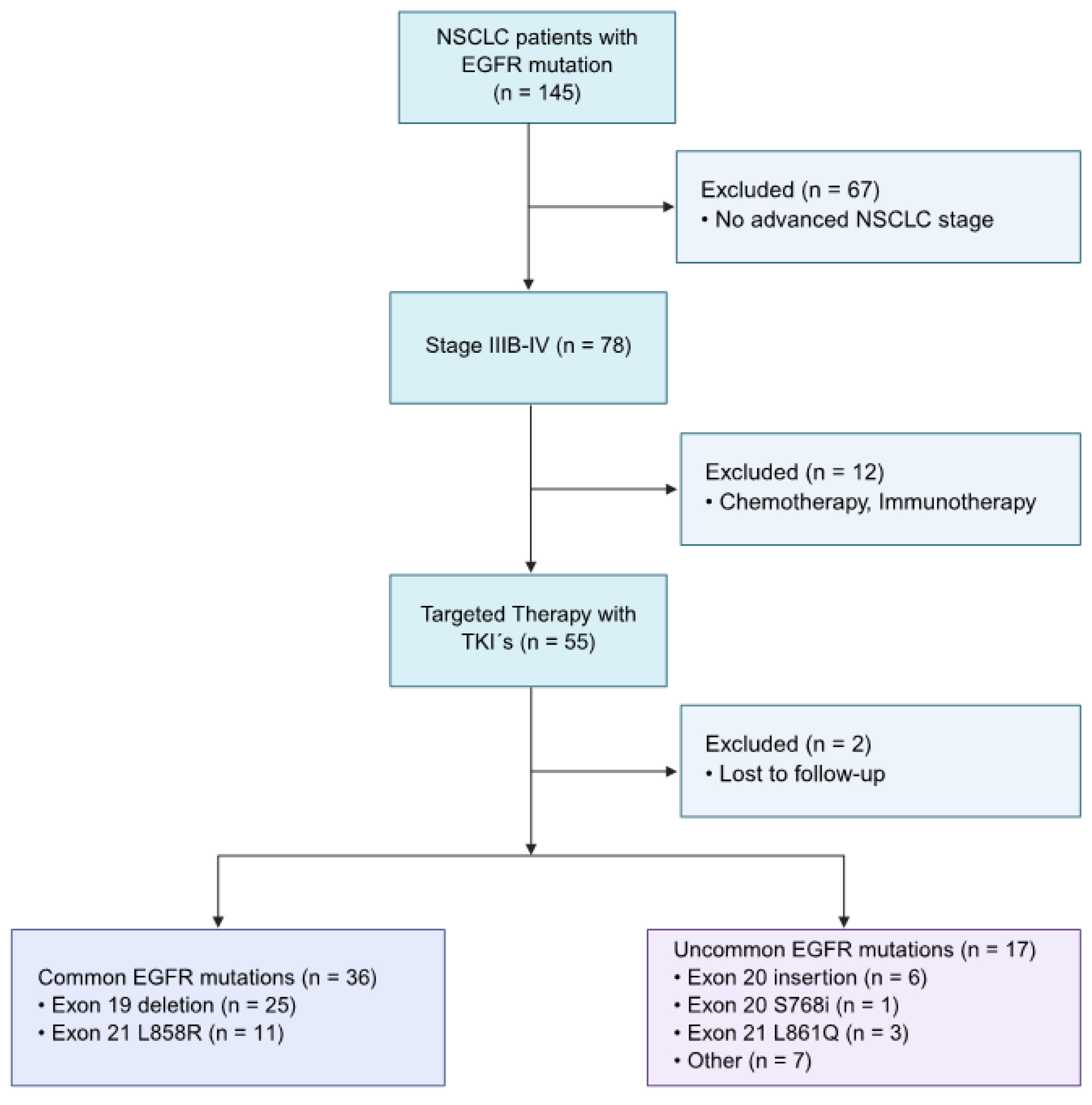

Among 145 patients with pathologically confirmed advanced NSCLC with known EGFR mutation status, 53 cases were included for evaluation, based on the following eligibility criteria: harboring advanced NSCLC, somatic EGFR mutation and having received TKIs as first-line-treatment (palliative therapy), illustrated in

Figure 1. The final sample size was subdivided into the common mutations (n = 36) and uncommon mutations (n = 17) groups.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in

Table 2., tumor characteristics, including the stage at initial diagnosis, location of metastasis, sites of metastasis, histologic subtype and PD-L1 status are presented in

Table 3. The patients received second-generation and third-generation TKIs in first-line, which is summarized in

Table 4, including response.

The median age at initial diagnosis was 73 years (range, 52-85 years), patients ≥ 65 years (66%) were predominant. The vast majority of the patients were Caucasian (91%) and female (60%). Approximately half of the patients (57%) had a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 18.5 to 24.9. Most of the patients were never smoker (43%) or former smoker (38%); 19% were heavy smokers (≥ 30 pack years). Based on the performance status (ECOG), the majority of the patients had ECOGs of 0 (60%), 30% had ECOGs of 1, 6% had ECOGs ≥ 2 and 4% were not evaluated. Most of the patients with exon 19 deletion were female (68%), whereas the gender dissemination of patients with an exon 21 L858R mutation or uncommon mutations was almost equally distributed.

All variables (age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, pack years, BMI and ECOG performance status) did not significantly differ between the EGFR exon 19 deletion, EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations. (p > 0.05) groups.

As shown in

Table 3, most of the patients (93%) had stage IVA (42%) or stage IVB (51%), only 8% had stage IIIB. Most patients harbored an adenocarcinoma (91%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (6%) and large cell carcinoma (4%). A negative PDL-1 expression (< 1%) was found in 25 patients (47%), 21 patients (40%) had a PDL-1 expression of 1-49%. In total, 6% had a high (50-89%) or a very high PDL-1 expression (≥90%). The primary sites of metastasis were pleura (42%), brain (26%), and bones (34%). Rare locations of metastasis were distant lymph nodes (9%), adrenal gland (6%) and the liver (11%). The cumulative percentages for metastatic locations will not sum to 100%, since patients can exhibit multiple metastatic sites simultaneously.

All variables (stage at initial diagnosis, histologic type, PDL-1 status, location and site of metastasis) did not significantly differ between the EGFR exon 19 deletion, EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations. (p > 0.05) groups.

Patients included in this study received second-generation and third-generation TKIs in the first-line. Details regarding the treatment pattern are summarized in

Table 4. Most of the study population received Osimertinib (third-generation TKI) (58%) or Afatinib (second-generation TKI) (32%). Of the 53 patients, four (8%) out of six patients with an exon 20 insertion were treated with Mobocertinib. One patient harbored additionally an ALK translocation and was treated with Brigatinib, a second-generation ALK TKI.

None of the patients had a complete response in the first-line, 36% had a partial response, followed by 11% with a stable disease and 4% with progressive disease.

3.1. Survival Analysis

3.1.1. Overall Survival Analysis

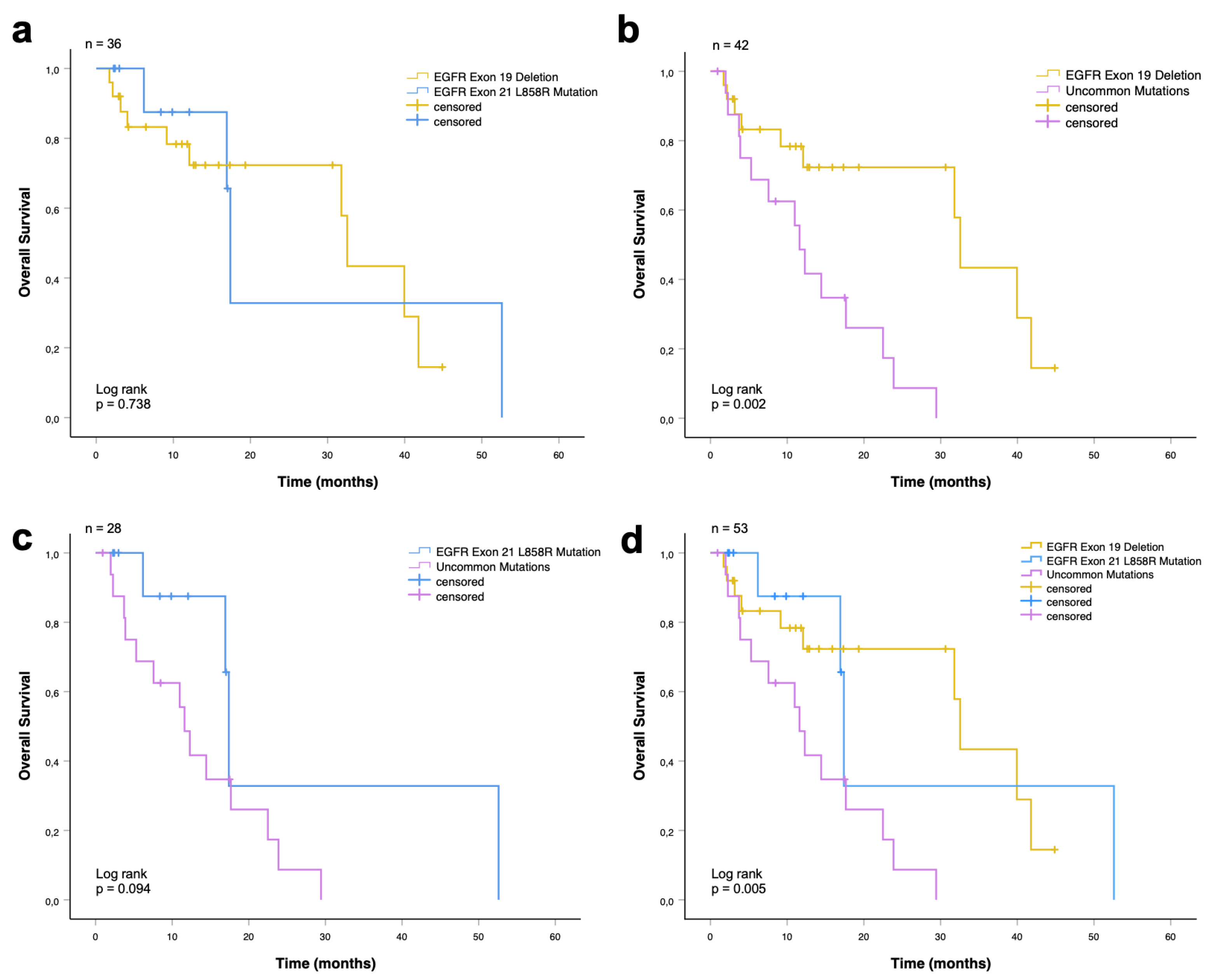

The median rwOS for the whole cohort (n = 53) was 17.7 months (95% CI, 10.4-24.9 months). Patients harboring an EGFR exon 19 deletion had a significantly longer overall survival compared with patients with EGFR uncommon mutations (32.5 vs. 11.6 months,

p = 0.002;

Figure 2b). There was no significant difference in the median overall survival between patients with EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (17.4 vs. 11.6 months,

p = 0.094;

Figure 2c), and between the EGFR exon 19 deletion and EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation groups (32.5 vs. 17.4 months,

p = 0.74; Figure. 2a).

A summary of the median OS times are shown in

Table 5, including the respective 95% CI. EGFR exon 19 deletion showed the longest median overall survival with 32.5 months (CI: 30.8-34.3 months), followed by EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation with 17.4 months (CI: 17.0 – 18.1 months). The shortest overall survival was of patients with uncommon mutations with 11.6 months (CI: 9.2-14.0 months).

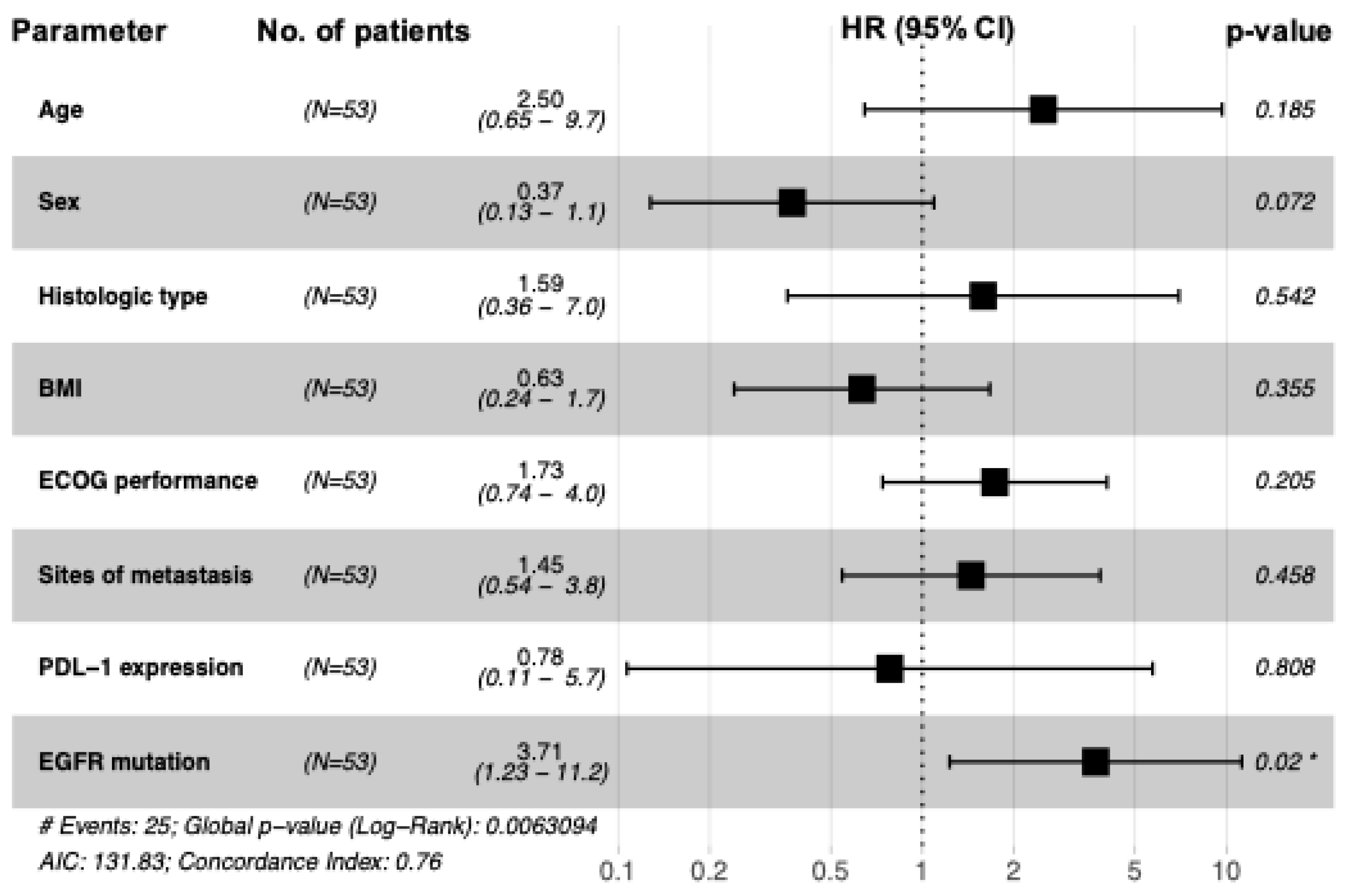

The univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis of overall survival, including the variables age, sex, histologic type, BMI, ECOG performance status, sites of metastasis, PDL-1 expression and EGFR mutation subtype is shown in

Table 6. The univariate analysis revealed that overall survival was longer in patients with common mutation (HR: 3.7; 95% CI: 1.6-8.7;

p = 0.002), ECOG status of 0 (HR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.1-4.5;

p = 0.018) and patients with adenocarcinoma (HR: 4.3; 95% CI: 1.4-14;

p = 0.013). In accordance with the univariate analysis, the multivariable analysis showed that NSCLC patients with a common mutation had a longer overall survival compared to the uncommon mutation subgroup (HR: 3.7; 95% CI: 1.23-11.2;

p = 0.02). No significant difference regarding OS could be identified for age, sex, histologic type, ECOG status, sites of metastasis, PDL-1 expression and BMI.

In conclusion, an EGFR common mutation subtype (HR = 3.71) was an independent predictor of better overall survival. The results are visualized in

Figure 3.

3.1.2. Progression-Free Survival Analysis

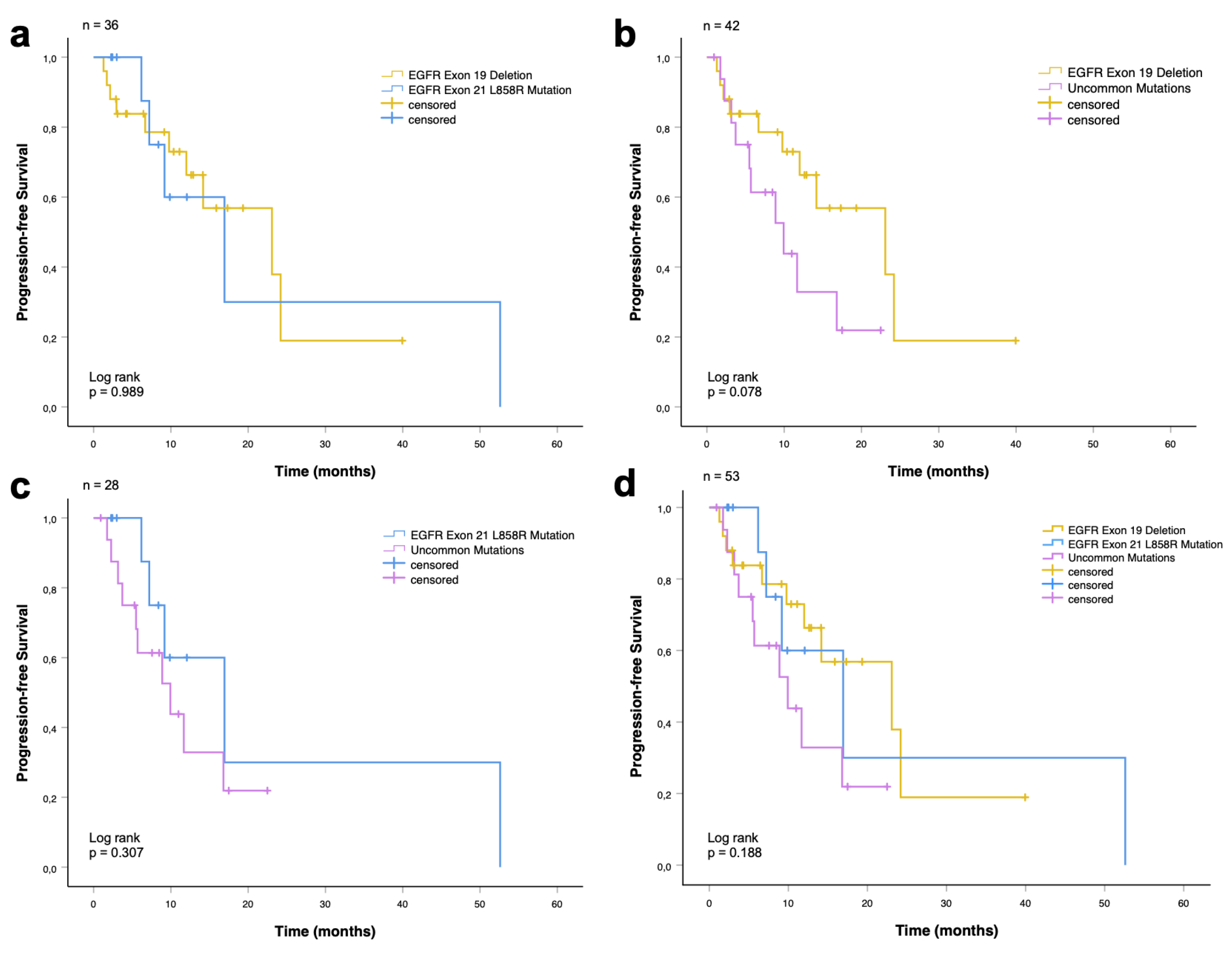

The median rwPFS in the entire cohort (n = 53) was 14.2 months (95% CI: 7.4-20.9 months). There was no significant difference in the median progression-free survival between all groups: patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion and EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation (23.1 vs. 17.0 months,

p = 0.989;

Figure 4a), patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion and EGFR uncommon mutations (23.1 vs. 10.0 months,

p = 0.078;

Figure 4b), patients with EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (17.0 vs. 10.0 months,

p = 0.307;

Figure 4c).

Median PFS times are shown in

Table 7, including the respective 95% CI. EGFR exon 19 deletion showed the longest median progression-free survival with 23.1 months (CI: 6.8-39.4 months), followed by EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation with 17.0 months (CI: 5.2 – 28.7 months). The shortest OS (10 months) had also patients with uncommon mutations (CI: 3.4-16.4 months).

The univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis of progression-free survival, including the variables age, sex, histologic type, BMI, ECOG performance status, sites of metastasis, PDL-1 expression and EGFR mutation subtype is demonstrated in

Table 8. Both, univariate and multivariable analysis revealed no significant associations.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined a prospective cohort of 53 patients with advanced NSCLC harboring an EGFR exon 18-21 mutation from two high-volume institutions in Vienna, Austria.

The beneficial survival outcome of EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC patients in first-line as well as the prognostic impact of clinicopathological characteristics and EGFR subtype differences have been examined previously, but predominantly in the Asian, Middle East and North Africa, Moroccan and especially in the Chinese population [

19,

20,

21]. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first real-world analyses to investigate the survival outcome after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment (second and third-generation) as well as the prognostic role of EGFR genotypes and clinical and pathological characteristics in advanced NSCLC patients in Austria.

In the present cohort, the majority of the patients were female (60%), Caucasians (91%) and never or former smoker (81%). Differences between common and uncommon EGFR mutations failed to reach significance between age groups, sexes, ethnicities, smokers and non-smokers, pack-years, or for varying ECOG status and BMI. Previous studies unveiled an association between distinct EGFR genotypes and smoking habits. Albeit not nominally significant, more than half of the patients with EGFR uncommon mutations are smokers or former smokers in contrast to patients harboring common mutations, where more than half of the patients are never smokers, supporting prior evidence [

15,

19,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The higher number of females in our sample reflects the previously shown [

19,

22,

25,

26,

27] increased likelihood in women with NSCLC of developing EGFR mutation compared to men. Also in line with previous findings, we provide tentative evidence for higher rates of EGFR exon 19 deletion within females [

19,

22,

28]. A substantial number of the patients had adenocarcinoma (91%), stage IV (93%) and one metastasis (55%). For both, the clinicopathological characteristics, as well as tumor characteristics, no significant differences in the number of common and uncommon mutations could be found.

Within the scope of the present study, we also investigated potential prognostic factors. Multivariable cox regressions revealed that an EGFR common genotype is an independent prognostic factor for improved median overall survival (mOS). No significant association could be found concerning age, sex, histologic type, ECOG performance status, BMI, sites of metastasis and PDL-1 expression. The observations align with a previous study, where female gender is additionally mentioned as an independent prognostic factor for improved overall survival [

19]. The strongest independent factor for prolonged overall survival is the EGFR common genotype, which is consistent with previous investigations [

2,

29]. Regarding to median progression-free survival (mPFS), independent prognostic factors could not be identified.

The survival analysis of the study demonstrated that patients with common EGFR mutations exhibited significantly longer mOS compared with those with an uncommon EGFR genotype. Moreover, within EGFR common mutations, exon 19 deletion surpassed (although not nominally significant) the mOS compared to exon 21 L858R mutation cohort. These results are concordant with previous real-world studies and clinical trials [

4,

19,

20,

29,

30]. Patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion achieved better mPFS, followed by EGFR exon 21 L858R; uncommon mutations had the poorest mPFS. These findings are overall in line with foregoing studies [

16,

17,

30].

Limitations

Some limitations have to be acknowledged. Firstly, the relatively small sample size may restrict the statistical power for various of the subgroup analyses conducted. Furthermore, the treatment options have changed over the period the data were collected. The vast majority of patients were treated with Afatinib (second-generation) or Osimertinib (third-generation), which may have had an impact on survival outcome. According to previous study data, the treatment with Osimertinib in first-line resulted in a significantly longer mPFS and mOS than with comparator TKIs [

10,

31,

32]. Moreover, therapy options for patients harboring rare EGFR mutations are more restricted than those for common mutations, which may be one reason for poorer survival outcome. In addition, patients carrying rare EGFR mutations are less responsive to TKIs [

22,

24].

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present survival analysis in a real-world setting are in agreement with the results of clinical trials. Our results underline the prognostic role of distinct EGFR genotypes and the relevance of corresponding analyses in NSCLC patients. The study also highlights the challenges regarding to EGFR uncommon mutations and the resulting need for further research to investigate alternative treatment options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.B., H.F., and D.K.; methodology, C.B., H.F. and D.K.; formal analysis, C.B.; investigation, C.B., H.F., V.R., M.H., O.I., L.A., C.W., J.K., N.M.., A.V. and D.K.; resources, C.B., H.F., V.R., M.H., O.I., L.A., C.W., J.K., N.M.., A.V. and D.K.; data curation, A. L-S, V.R., J.K..; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., H.F., V.R., M.H., O.I., L.A., C.W., J.K., N.M., A.V. and D.K; supervision, H.F., V.R. and D.K.; project administration, H.F. and D.K.; funding acquisition, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The LALUCA registry received funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeOne, Böhringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi and Takeda.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or human tissue were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant institutional and/or national research committees, as well as the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical guidelines. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Vienna (EK-20-061-VK).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Leyla Ay received speaker fees from Roche, AstraZeneca, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Maximilian Hochmair, received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb,Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche, and has had consulting or advisory roles with Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Novartis, and Roche. Oliver Illini received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Menarini, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche. Received honoraria for advisory boards from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche. Received research grants (institution) from Amgen, and AstraZeneca outside of the submitted study. Nino Müser reports personal fees for lectures, consultancy and participation in advisory boards from MSD, Roche, MEDCH. Additionally, registration fee, travel and accommodation from Sanofi, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Lilly Oncology. Arschang Valipour has received honoraria for lectures at national and international meetings and served as a consultant for Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GLAXOSMITHKLINE, Menarini, Sanofi, and Zentiva. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Yu, J.; Chen, D. Global Burden of Lung Cancer in 2022 and Projections to 2050: Incidence and Mortality Estimates from GLOBOCAN. Cancer Epidemiology 2024, 93, 102693. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. Prognostic Factors Influencing Overall Survival in Stage IV EGFR-Mutant NSCLC Patients Treated with EGFR-TKIs. BMC Pulm Med 2025, 25, 114. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.J.; Mokánszki, A.; Méhes, G. The Rapidly Changing Field of Predictive Biomarkers of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res 2024, 30, 1611733. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, X.; Qin, N.; Su, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Jin, M.; Wang, J. The Prognostic Role of EGFR-TKIs for Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40374. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Hu, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Ma, Z.; Lu, B.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. The Survival Outcomes and Prognosis of Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Thoracic Three-Dimensional Radiotherapy Combined with Chemotherapy. Radiat Oncol 2014, 9, 290. [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Forjaz, G.; Mooradian, M.J.; Meza, R.; Kong, C.Y.; Cronin, K.A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Lowy, D.R.; Feuer, E.J. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 640–649. [CrossRef]

- Melosky, B.; Kambartel, K.; Häntschel, M.; Bennetts, M.; Nickens, D.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Kayser, A.; Moran, M.; Cappuzzo, F. Worldwide Prevalence of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Mol Diagn Ther 2022, 26, 7–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Chen, G.; Feng, J.; Liu, X.-Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Ren, S.; et al. Erlotinib versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Patients with Advanced EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Study. The Lancet Oncology 2011, 12, 735–742. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.L.; Chen, G.; Feng, J.; Liu, X.-Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Ren, S.; et al. Final Overall Survival Results from a Randomised, Phase III Study of Erlotinib versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment of EGFR Mutation-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802). Annals of Oncology 2015, 26, 1877–1883. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; He, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, C.; Walding, A.; Saggese, M.; Huang, X.; et al. Osimertinib Versus Comparator EGFR TKI as First-Line Treatment for EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC: FLAURA China, A Randomized Study. Targ Oncol 2021, 16, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.T.; Vyse, S.; Huang, P.H. Rare Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2020, 61, 167–179. [CrossRef]

- Pretelli, G.; Spagnolo, C.C.; Ciappina, G.; Santarpia, M.; Pasello, G. Overview on Therapeutic Options in Uncommon EGFR Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): New Lights for an Unmet Medical Need. IJMS 2023, 24, 8878. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lu, H. EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Transl Cancer Res 2020, 9, 2982–2991. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, E.; Feld, E.; Horn, L. Driven by Mutations: The Predictive Value of Mutation Subtype in EGFR -Mutated Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2017, 12, 612–623. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, P.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, C.; et al. Comprehensive Profiling of EGFR Mutation Subtypes Reveals Genomic-Clinical Associations in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients on First-Generation EGFR Inhibitors. Neoplasia 2023, 38, 100888. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-Y.; Yu, S.-F.; Wang, S.-H.; Bai, H.; Zhao, J.; An, T.-T.; Duan, J.-C.; Wang, J. Clinical Outcomes of EGFR-TKI Treatment and Genetic Heterogeneity in Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients with EGFR Mutations on Exons 19 and 21. Chin J Cancer 2016, 35, 30. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liao, Z. Real-World Data Analysis of First-Line Targeted Therapy for Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Different EGFR Mutation Status in a Tertiary Care Hospital. JCO 2024, 42, e20586–e20586. [CrossRef]

- Lang-Stöberl, A.; Fabikan, H.; Hochmair, M.; Kirchbacher, K.; Rodriguez, V.M.; Ay, L.; Weinlinger, C.; Rosenthaler, D.; Illini, O.; Müser, N.; et al. The Landsteiner Lung Cancer Research Platform (LALUCA): Objectives, Methodology and Implementation of a Real-World Clinical Lung Cancer Registry. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2024. [CrossRef]

- Boukansa, S.; Mouhrach, I.; El Agy, F.; El Bardai, S.; Bouguenouch, L.; Serraj, M.; Amara, B.; Ouadnouni, Y.; Smahi, M.; Alami, B.; et al. Clinicopathological and Prognostic Implications of EGFR Mutations Subtypes in Moroccan Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A First Report. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298721. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Si, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, T.; Song, Z. The Effect of EGFR-TKIs on Survival in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with EGFR Mutations: A Real-World Study. Cancer Medicine 2023, 12, 5630–5638. [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.-K.; Choi, H.C.-W.; Lee, V.H.-F. Overall Survival Benefits of First-Line Treatments for Asian Patients with Advanced Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Mutated NSCLC Harboring Exon 19 Deletion: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 3362. [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann-Guerrero, D.; Huber, R.M.; Reu, S.; Tufman, A.; Mertsch, P.; Syunyaeva, Z.; Jung, A.; Kahnert, K. NSCLC Patients Harbouring Rare or Complex EGFR Mutations Are More Often Smokers and Might Not Benefit from First-Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy. Respiration 2018, 95, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.-W.; Shie, S.-S.; Wang, C.-W.; Chiu, C.-T.; Wang, C.-L.; Yang, T.-Y.; Chou, S.-C.; Liu, C.-Y.; Kuo, C.-H.S.; Lin, Y.-C.; et al. Association of Smoking Status with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Harboring Uncommon Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1011092. [CrossRef]

- Lohinai, Z.; Hoda, M.A.; Fabian, K.; Ostoros, G.; Raso, E.; Barbai, T.; Timar, J.; Kovalszky, I.; Cserepes, M.; Rozsas, A.; et al. Distinct Epidemiology and Clinical Consequence of Classic Versus Rare EGFR Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2015, 10, 738–746. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, F.; Fernandes, G.; Queiroga, H.; Machado, J.C.; Cirnes, L.; Souto Moura, C.; Hespanhol, V. Overall Survival Analysis and Characterization of an EGFR Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Population. Archivos de Bronconeumología 2018, 54, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Ten Berge, D.M.H.J.; Aarts, M.J.; Groen, H.J.M.; Aerts, J.G.J.V.; Kloover, J.S. A Population-Based Study Describing Characteristics, Survival and the Effect of TKI Treatment on Patients with EGFR Mutated Stage IV NSCLC in the Netherlands. European Journal of Cancer 2022, 165, 195–204. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Li, N.; Wu, G.; Liu, W.; Liao, G.; Cai, K.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of EGFR Mutations in Asian Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer of Adenocarcinoma Histology – Mainland China Subset Analysis of the PIONEER Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143515. [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, H.; Lin, L.; Takahashi, T.; Nomura, M.; Suzuki, M.; Wistuba, I.I.; Fong, K.M.; Lee, H.; Toyooka, S.; Shimizu, N.; et al. Clinical and Biological Features Associated With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene Mutations in Lung Cancers. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2005, 97, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Cardarella, S.; Lydon, C.A.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Jackman, D.M.; Jänne, P.A.; Johnson, B.E. Five-Year Survival in EGFR -Mutant Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma Treated with EGFR-TKIs. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2016, 11, 556–565. [CrossRef]

- Syrigos, K.; Kotteas, I.; Paraskeva, M.; Gkiozos, I.; Boura, P.; Tsagouli, S.; Grapsa, D.; Charpidou, A. Prognostic Value of EGFR Genotype in EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, PA2852. [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.S.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Planchard, D.; Cho, B.C.; Gray, J.E.; Ohe, Y.; Zhou, C.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Cheng, Y.; Chewaskulyong, B.; et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR -Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.-C.; Ohe, Y.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Chewaskulyong, B.; Lee, K.H.; Dechaphunkul, A.; Imamura, F.; Nogami, N.; Kurata, T.; et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR -Mutated Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 113–125. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria: NSCLC at an advanced stage (IIIB or higher), TKI therapy as first-line with known start and end date and harboring an EGFR mutation. The eligible patients (n = 53) who are included in the study were stratified into the two categories: common (n = 36) and uncommon EGFR mutations (n = 17).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria: NSCLC at an advanced stage (IIIB or higher), TKI therapy as first-line with known start and end date and harboring an EGFR mutation. The eligible patients (n = 53) who are included in the study were stratified into the two categories: common (n = 36) and uncommon EGFR mutations (n = 17).

Figure 2.

Overall survival among advanced NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) according to EGFR mutations. (a) Patients with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation (p = 0.74). (b) Patients with exon 19 deletion and uncommon mutations (p = 0.002). (c) Patients with exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (p = 0.094). (d) Patients with common (exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation) and uncommon mutations (p = 0.005).

Figure 2.

Overall survival among advanced NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) according to EGFR mutations. (a) Patients with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation (p = 0.74). (b) Patients with exon 19 deletion and uncommon mutations (p = 0.002). (c) Patients with exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (p = 0.094). (d) Patients with common (exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation) and uncommon mutations (p = 0.005).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for overall survival (OS) for subgroup analysis (n = 53). The forest plot was used to show the prognostic association in different subgroups for overall survival. Patient numbers (n = 53), hazard ratios (HR), p values and 95% CIs (confidence intervals) are shown. Subgroups: Age (<60 vs. ≥ 60), sex (male vs. female), histologic type (ADC vs. other), BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25), ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2), Sites of metastasis (≤ 1 vs. > 1), PDL-1 expression (0-49% vs. 50-100%) and EGFR mutation (common vs. uncommon).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for overall survival (OS) for subgroup analysis (n = 53). The forest plot was used to show the prognostic association in different subgroups for overall survival. Patient numbers (n = 53), hazard ratios (HR), p values and 95% CIs (confidence intervals) are shown. Subgroups: Age (<60 vs. ≥ 60), sex (male vs. female), histologic type (ADC vs. other), BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25), ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2), Sites of metastasis (≤ 1 vs. > 1), PDL-1 expression (0-49% vs. 50-100%) and EGFR mutation (common vs. uncommon).

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival among advanced NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) according to EGFR mutations. (a) Patients with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation (p = 0.989). (b) Patients with exon 19 deletion and uncommon mutations (p = 0.078). (c) Patients with exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (p = 0.307). (d) Patients with common (exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation) and uncommon mutations (p = 0.188).

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival among advanced NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) according to EGFR mutations. (a) Patients with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation (p = 0.989). (b) Patients with exon 19 deletion and uncommon mutations (p = 0.078). (c) Patients with exon 21 L858R mutation and uncommon mutations (p = 0.307). (d) Patients with common (exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation) and uncommon mutations (p = 0.188).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for progression-free survival (PFS) for subgroup analysis (n = 53). The forest plot was used to demonstrate the prognostic association in different subgroups for progression-free survival. Patient numbers (n = 53), hazard ratios (HR), p values and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Subgroups: Age (<65 vs. ≥ 65), sex (male vs. female), histologic type (ADC vs. other), BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25), ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2), sites of metastasis (≤1 vs. <1), PDL-1 expression (0-49% vs. 50-100%) and EGFR mutation (common vs. uncommon).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for progression-free survival (PFS) for subgroup analysis (n = 53). The forest plot was used to demonstrate the prognostic association in different subgroups for progression-free survival. Patient numbers (n = 53), hazard ratios (HR), p values and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Subgroups: Age (<65 vs. ≥ 65), sex (male vs. female), histologic type (ADC vs. other), BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25), ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2), sites of metastasis (≤1 vs. <1), PDL-1 expression (0-49% vs. 50-100%) and EGFR mutation (common vs. uncommon).

Table 1.

Occurrence of different EGFR mutations in the study population. Mutation types are subdivided in EGFR common mutations and uncommon mutations.

Table 1.

Occurrence of different EGFR mutations in the study population. Mutation types are subdivided in EGFR common mutations and uncommon mutations.

| EGFR mutation |

All Patients (N = 145) |

|

Common, n (%) |

|

| Exon 19 deletion |

58 (40) |

| Exon 21 L858R mutation |

29 (20) |

|

Uncommon, n (%) |

|

| Exon 20 insertion |

28 (19) |

| Exon 21 L861Q mutation |

6 (4) |

| Exon 20 S768i mutation |

2 (1) |

| Other 1

|

22 (14) |

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (n = 53).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (n = 53).

| Demographic and clinical Characteristics |

No. of Patients |

Exon 19

Deletion |

L858R

Mutation |

Uncommon

Mutations |

p value1

|

| Total |

53 |

25 (47%) |

11 (21%) |

17 (32%) |

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

| Median (range) |

73 (52-85) |

66 (52-82) |

74 (59-85) |

73 (57-83) |

|

| Age groups, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.1584 |

| < 65 |

18 (34) |

12 (48) |

2 (18) |

4 (24) |

|

| ≥ 65 |

35 (66) |

13 (52) |

9 (82) |

13 (76) |

|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.5824 |

| Male |

21 (40) |

8 (32) |

5 (45) |

8 (47) |

|

| Female |

32 (60) |

17 (68) |

6 (55) |

9 (53) |

|

| Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.3823 |

| Asian |

2 (4) |

1 (4) |

- |

1 (6) |

|

| Caucasian |

48 (91) |

24 (96) |

10 (91) |

14 (82) |

|

| Unknown |

3 (5) |

- |

1 (9) |

2 (12) |

|

| Smoking status, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.2252 |

| Never smoker |

23 (43) |

13 (52) |

6 (55) |

4 (24) |

|

| Former smoker |

20 (38) |

7 (28) |

3 (27) |

10 (59) |

|

| Smoker |

9 (17) |

5 (20) |

2 (18) |

2 (12) |

|

| Unknown |

1 (2) |

- |

- |

1 (6) |

|

| Pack-years, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.4331 |

| Light smoker (1-29 py) |

18 (34) |

8 (32) |

2 (18) |

8 (47) |

|

| Heavy smoker (≥ 30 py) |

10 (19) |

4 (16) |

2 (18) |

4 (24) |

|

| Unknown |

25 (47) |

13 (52) |

7 (64) |

5 (29) |

|

| ECOG status at diagnosis, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.6057 |

| 0 |

32 (60) |

17 (68) |

6 (55) |

9 (53) |

|

| 1 |

16 (30) |

5 (20) |

4 (36) |

7 (41) |

|

| ≥ 2 |

3 (6) |

1 (4) |

1 (9) |

1 (6) |

|

| Unknown |

2 (4) |

2 (8) |

- |

- |

|

| BMI, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.2433 |

| Underweight (<18.5) |

1 (2) |

1 (4) |

- |

- |

|

| Normal range (18.5-24.9) |

30 (57) |

14 (56) |

8 (73) |

8 (47) |

|

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) |

14 (26) |

5 (20) |

1 (9) |

8 (47) |

|

| Obese Class I (30.0-34.9) |

8 (15) |

5 (20) |

2 (18) |

1 (6) |

|

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics of the study population (n = 53).

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics of the study population (n = 53).

| Tumor Characteristics |

No. of

Patients |

Exon 19

Deletion |

L858R

Mutation |

Uncommon Mutations |

p value1

|

| Total |

53 |

25 (47%) |

11 (21%) |

17 (32%) |

|

|

Stage at initial diagnosis, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.1449 |

| Stage IIIB |

4 (8) |

1 (4) |

- |

3 (18) |

|

| Stage IVA |

22 (42) |

8 (32) |

5 (45) |

9 (53) |

|

| Stage IVB |

27 (51) |

16 (64) |

6 (55) |

5 (29) |

|

|

Histologic type, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.341 |

| Adenocarcinoma |

48 (91) |

24 (96) |

10 (91) |

14 (82) |

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

3 (6) |

- |

1 (9) |

2 (12) |

|

| NOS |

2 (4) |

1 (4) |

- |

1 (6) |

|

|

PDL-1 status, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.5045 |

| Negative (< 1%) |

25 (47) |

11 (44) |

8 (73) |

6 (35) |

|

| Low expression (1-49%) |

21 (40) |

11 (44) |

3 (27) |

7 (41) |

|

| High expression (50-89%) |

2 (4) |

1 (4) |

- |

1 (6) |

|

| Very high expression (≥ 90%) |

1 (2) |

1 (4) |

- |

- |

|

| Unknown |

4 (8) |

1 (4) |

- |

3 (18) |

|

Location of metastasis,

n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.8236 |

| Pleura effusion |

22 (42) |

12 (48) |

4 (36) |

6 (35) |

|

| Brain |

14 (26) |

9 (36) |

2 (18) |

3 (18) |

|

| Bones |

18 (34) |

10 (40) |

3 (27) |

5 (29) |

|

| Distant lymph nodes |

5 (9) |

3 (12) |

- |

2 (12) |

|

| Adrenal gland |

3 (6) |

1 (4) |

1 (9) |

1 (6) |

|

| Liver |

6 (11) |

4 (16) |

1 (9) |

1 (6) |

|

| Other |

5 (9) |

1 (4) |

3 (27) |

1 (6) |

|

|

Sites of metastasis, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.1079 |

| No distant metastasis |

4 (8) |

1 (4) |

- |

3 (18) |

|

| 1 |

29 (55) |

11 (44) |

9 (82) |

9 (53) |

|

| 2-3 |

20 (38) |

13 (52) |

2 (18) |

5 (29) |

|

Table 4.

Treatment pattern and response of the study population (n = 53).

Table 4.

Treatment pattern and response of the study population (n = 53).

| Treatment Pattern and Response |

No. of Patients |

Common |

Uncommon |

| Total |

53 |

36 (68%) |

17 (32%) |

|

TKI, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Afatinib (second-generation) |

17 (32) |

11 (31) |

6 (35) |

| Brigatinib1 (second-generation) |

1 (2) |

- |

1 (6) |

| Osimertinib (third-generation) |

31 (58) |

25 (69) |

6 (35) |

| Mobocertinib2 (second-generation) |

4 (8) |

- |

4 (24) |

|

Best response, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Complete response (CR) |

- |

- |

- |

| Partial response (PR) |

19 (36) |

10 (28) |

9 (53) |

| Stable disease (SD) |

6 (11) |

3 (8) |

3 (18) |

| Progressive disease (PD) |

2 (4) |

2 (6) |

- |

| Unknown |

26 (49) |

21 (58) |

5 (29) |

Table 5.

Median overall survival time in months according to EGFR subtypes (exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R mutation, uncommon mutations).

Table 5.

Median overall survival time in months according to EGFR subtypes (exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R mutation, uncommon mutations).

| EGFR subtype |

|

95% Confidence Interval |

| |

Median |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| Exon 19 deletion |

32.5 |

30.8 |

34.3 |

| L858R mutation |

17.4 |

17.0 |

18.1 |

| Uncommon1

|

11.6 |

9.2 |

14.0 |

| Overall (n = 53) |

17.7 |

10.4 |

25.0 |

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for overall survival of NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) and harboring an EGFR common or uncommon mutation (n = 53).

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for overall survival of NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) and harboring an EGFR common or uncommon mutation (n = 53).

| Variable |

Overall survival |

|

| |

Univariate |

|

Multivariable |

| |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

| Age (<65 vs. ≥ 65) |

1.0 (0.99-1.1) |

0.099 |

|

2.50 (0.65-9.7) |

0.185 |

| Sex (male vs. female) |

0.55 (0.26-1.2) |

0.128 |

|

0.37 (0.13-1.1) |

0.072 |

| Histologic type (ADC vs. other) |

4.3 (1.4-14) |

0.013 |

|

1.59 (0.36-7.0) |

0.542 |

| BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25) |

0.77 (0.35-1.7) |

0.517 |

|

0.63 (0.24-1.7) |

0.355 |

| ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2) |

2.3 (1.1-4.5) |

0.018 |

|

1.73 (0.74-4.0) |

0.205 |

| Sites of metastasis (≤1 vs. >1) |

1.1 (0.52-2.4) |

0.75 |

|

1.45 (0.54-3.8) |

0.458 |

PDL-1 expression

(0-49% vs. 50-100%) |

0.8 (0.19-3.4) |

0.765 |

|

0.78 (0.11-5.7) |

0.808 |

EGFR mutation*

(common vs. uncommon) |

3.7 (1.6-8.7) |

0.002 |

|

3.71 (1.23-11.2) |

0.02 |

Table 7.

Median progression-free survival time in months according to EGFR subtypes (exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R mutation, uncommon mutations).

Table 7.

Median progression-free survival time in months according to EGFR subtypes (exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R mutation, uncommon mutations).

| EGFR subtype |

|

95% Confidence Interval |

| |

Median |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| Exon 19 deletion |

23.1 |

6.8 |

39.4 |

| L858R mutation |

17.0 |

5.2 |

28.7 |

| Uncommon1

|

10.0 |

3.4 |

16.4 |

| Overall |

14.2 |

7.4 |

21.0 |

Table 8.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for progression-free survival of NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) and harboring an EGFR common or uncommon mutation (n = 53).

Table 8.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for progression-free survival of NSCLC patients who received EGFR-TKI (first-line) and harboring an EGFR common or uncommon mutation (n = 53).

| Variable |

Progression-free survival |

|

| |

Univariate |

|

Multivariable |

| |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

| Age (<65 vs. ≥ 65) |

2.2 (0.86-5.6) |

0.1 |

|

2.59 (0.78-8.7) |

0.122 |

| Sex (male vs. female) |

0.58 (0.26-1.3) |

0.184 |

|

0.41 (0.15-1.1) |

0.075 |

| Histologic type (ADC vs. other) |

2.5 (0.7-8.6) |

0.16 |

|

1.21 (0.25-5.8) |

0.808 |

| BMI (<25 vs. ≥ 25) |

1.1 (0.47-2.4) |

0.883 |

|

1.48 (0.58-3.8) |

0.417 |

| ECOG status (0 vs. 1-2) |

1.2 (0.56-2.5) |

0.654 |

|

0.66 (0.27-1.7) |

0.379 |

| Sites of metastasis (≤1 vs. >1) |

0.76 (0.32-1.8) |

0.529 |

|

1.18 (0.43-3.2) |

0.751 |

PDL-1 expression

(0-49% vs. 50-100%) |

0.38 (0.05-2.9) |

0.35 |

|

0.24 (0.03-2.3) |

0.218 |

EGFR mutation*

(common vs. uncommon) |

2.2 (0.97-5.2) |

0.06 |

|

1.79 (0.60-5.3) |

0.292 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).