1. Introduction

The incidence of gastric subepithelial lesions (SELs) is on the rise, attributed to the widespread use of gastroscopy.[

1] Approximately 1.9% of patients who undergo gastroscopy are found to have SELs.[

2] A subset of these lesions originates from the muscularis propria (MP) layer, which includes gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), leiomyomas, and schwannomas. It is imperative to identify SELs with malignant potential, such as GISTs, for timely management. Certain characteristics observed in computed tomography (CT) scans, including location of the lesions, size, presence of necrosis, and enhancement during various phases, may assist in distinguishing GISTs from leiomyomas.[

3] Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) serves as a superior modality for characterizing the features of SELs; however, it still demonstrates a limited accuracy of 43% in predicting histological diagnoses.[4, 5] Notable features on EUS that may aid in differentiating GISTs from leiomyomas include heterogeneity, irregular borders, echogenic foci, cystic (or anechoic) spaces, and the presence of dimpling or ulceration.[4, 6]

Histological assessment is essential for the definitive diagnosis of SELs, necessitating tissue acquisition for effective risk stratification. Proposed methods for obtaining tissue include mucosal incision-assisted biopsy (MIAB), bite-on-bite stacked biopsy, and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration or biopsy.[

5] However, the yield rates of these techniques have proven inadequate, failing to provide the mitotic rate necessary for assessing malignant potential.[

7] Furthermore, the incidence of bleeding complications associated with forceps biopsy methods can reach as high as 8%, and the small size of the lesions complicates EUS-guided tissue acquisition.[

8] Recent advancements in endoscopic resection (ER) and wound closure techniques, such as endoscopic muscularis dissection (EMD), endoscopic subserosal dissection (ESSD), submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER), and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), have been developed to excise SELs that extend beyond the submucosal layer, facilitating both definitive histological diagnosis and curative resection.[9-11] The clinical guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recognize ER as an alternative to surgical intervention for small gastric GISTs.[4, 12] Additionally, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines recommend considering ER—specifically STER, EFTR, or endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE)—as a treatment option when there is a clinical indication or when attempts to obtain a diagnosis for the resection of SELs have failed.[

13] The objective of this study was to assess the

GAstric

Stromal

Tumor

Resection

Outcomes (GASTRO Trial) by different ER techniques and identify EUS predictors for diagnosis of GISTs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Enrollment

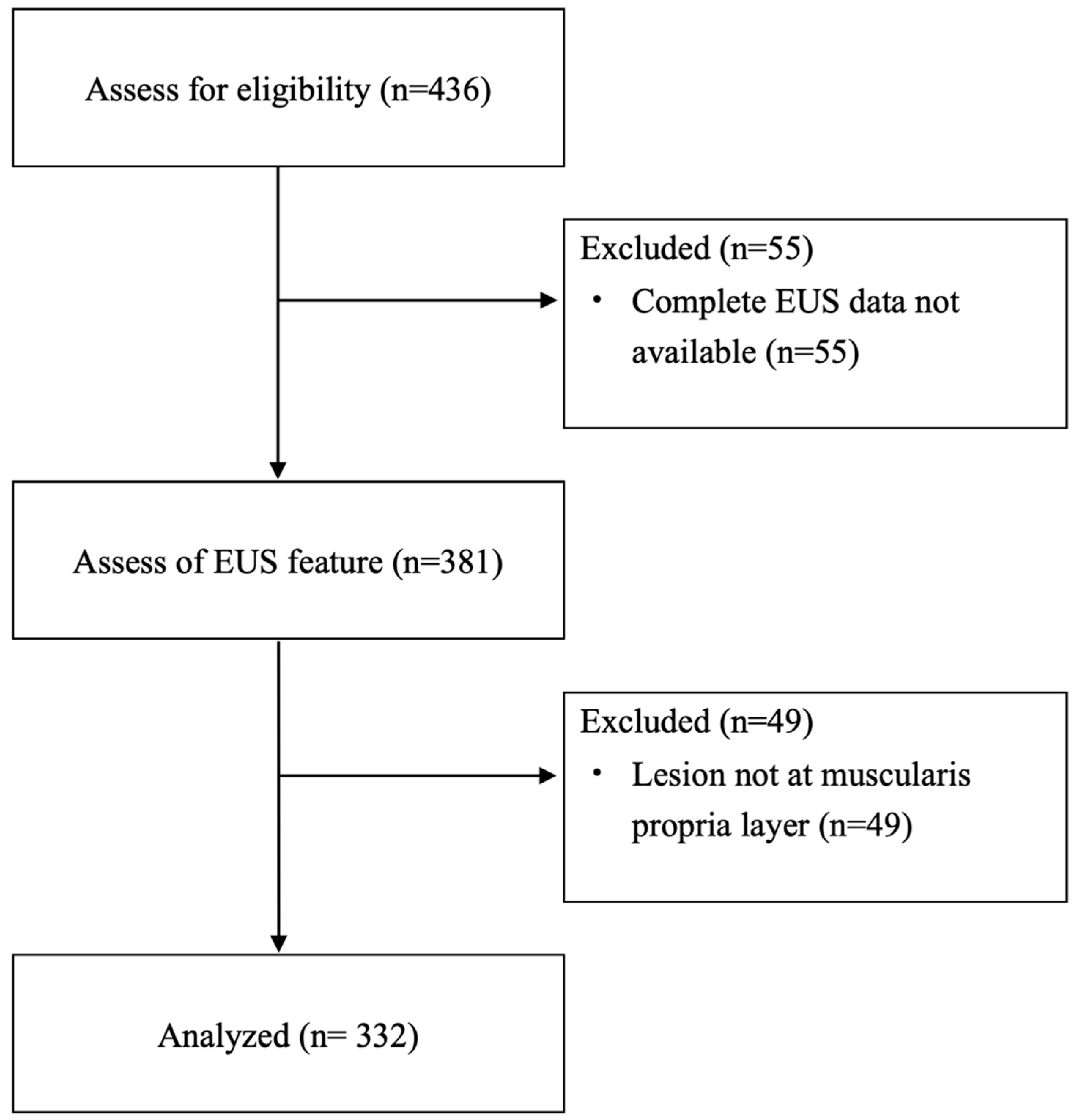

This multicenter study was conducted from January 2012 to April 2024 across nine tertiary-care referral centers in Taiwan. The study included patients aged 18 years and older who had EUS-documented SELs originating from the muscularis propria layer of the stomach and who underwent ER. The criteria for ER included an initial lesion size greater than 20 mm, an increase in size during follow-up, the presence of high-risk features (such as heterogeneous echotexture, exophytic growth, and irregular borders) observed on EUS, known malignant histology, symptomatic presentation, and patient preference. Patients were excluded from the study if complete EUS or pathological data were unavailable (

Figure 1). The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Far Eastern Memorial Hospital (FEMH-109047-E), and the requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the anonymized nature of the data analyzed.

2.2. Outcome Measurements

Medical records were reviewed to gather demographic and procedure-related information. Technical success was defined as the successful removal of the SELs through ER, either as an en-bloc or piecemeal procedure. The total procedure time was measured from the initial mucosal incision until complete wound closure. Complications were classified as either intraprocedural or delayed perforation and bleeding. Early bleeding was defined as any bleeding occurring within 48 hours after the resection, while delayed bleeding referred to bleeding that happened more than 48 hours after the procedure.

2.3. Procedures in the ER Techniques

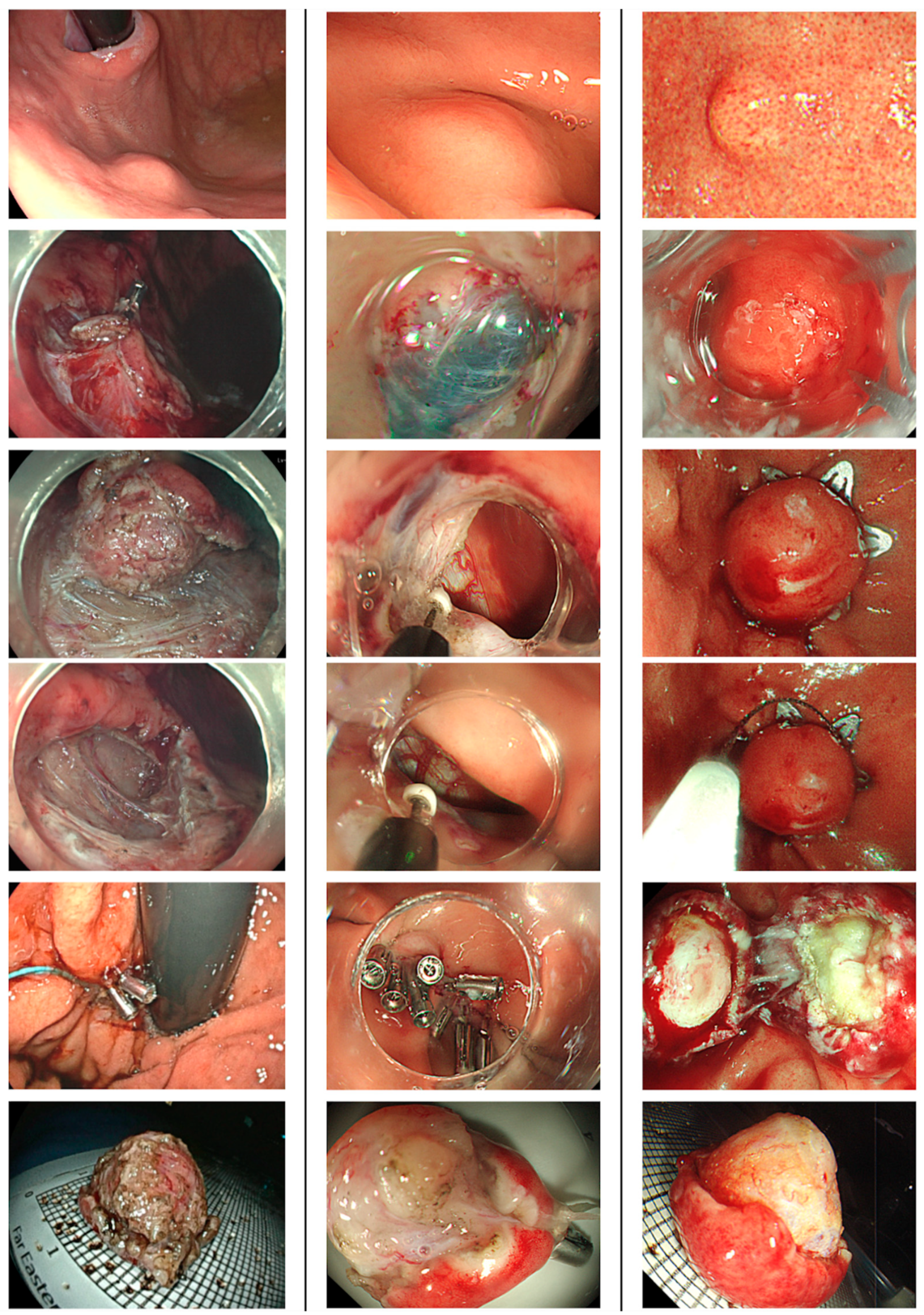

Patients underwent ER under either intravenous or general anesthesia after preoperative prophylactic antibiotic. Proton pump inhibitors were prescribed for 8~12 weeks after the procedure. They resumed enteral feeding after ER if there were no peritoneal signs noticed. ER technique included EMD, ESSD, STER and EFTR (

Figure 2). EMD and ESSD involved making a mucosal incision, followed by submucosal dissection and muscular or subserosal dissection beneath the visibly discernible tumor margin. EFTR was executed using either a non-exposed method with over-the-scope clips or an exposed method via conventional endoscopic dissection techniques. The choice of traction methods for dissection was left to the discretion of the endoscopists, tailored to the growth pattern of the SELs to facilitate en-bloc removal. STER was performed by creating a 2-cm mucostomy away from the tumor, followed by submucosal tunneling to locate the SELs, after which tumor dissection, retrieval, and closure of the mucosal entry ensued. All gastric wall defects resulting from ER were securely closed using various techniques, including simple closure with endoclips, purse-string closure with detachable endoloops and endoclips, over-the-scope clips, or an endoscopic suturing system.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The basic characteristics of the patients were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Discrete data were presented as counts and percentages, while continuous variables are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD), along with the maximum and minimum values. To evaluate categorical variables, the chi-squared test was employed. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, a logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between various risk factors and outcomes. Factors associated with histology were identified using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Variables that yielded p-values less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. Moreover, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated using the Littenberg and Moses linear model. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS for Mac OS, version 29.0.1.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data of Enrolled Patients

The demographic data was presented in

Table 1. A total of 325 patients (219 females and 106 males; mean age 55.4 ± 12.5 years) with 332 lesions were enrolled in the study (

Figure 1). The mean size (range) ± SD of the myogenic tumors measured under endoscopy was 15.8 (4~50) ± 8.2 mm, while the size under EUS was 14.5 (3~45) ± 7.7 mm. Most lesions were predominantly located in the upper body (41.0%), followed by the cardia (22.9%) and fundus (21.7%). Under EUS examination, the proportions of lesions with irregular borders, heterogeneous echotexture, and exophytic growth were 27.1%, 54.8%, and 33.4%, respectively. The most common pathology identified was leiomyoma (46.1%), followed closely by GISTs at 45.8%. Other histologic types accounting for 8.1% of the tumors and including 8 schwannomas, 5 calcified fibrous tumors. Three lesions were ectopic pancreas and two were spindle cell tumors. The remaining 9 lesions were tubular adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, lipoma, ectopic spleen, gastritis cystica polyposa, fundic gland polyp, fibrotic tissue, AV malformation, and one vessel tissue with atherosclerosis. Among the GISTs, the majority (77.6%) were classified as very low risk, while the remaining tumors were categorized as low risk (9.2%), intermediate risk (9.9%), and high risk (3.3%).

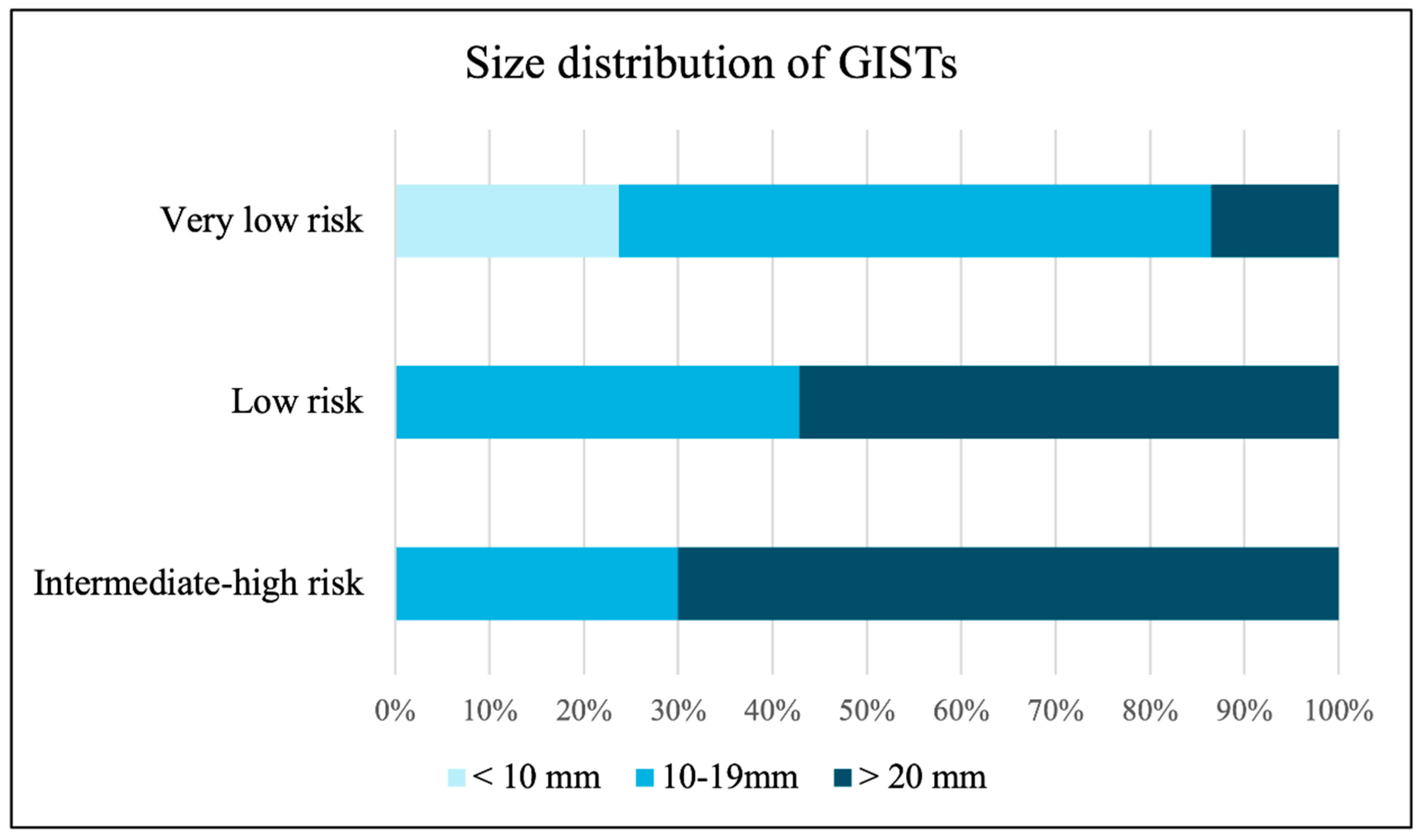

Figure 3 illustrates the size distribution of GISTs according to risk stratification, showing that tumors larger than 20 mm were found in 13.6% of very low-risk, 57.1% of low-risk, and 70.0% of intermediate to high-risk lesions.

3.2. Efficacy and Safety of ER in Myogenic SELs

The technical success rate was 97.0%, and the en-bloc rate was 94.3% across the 332 procedures, which included EMD, ESSD, STER, and EFTR performed in 58.1%, 13.9%, 8.4%, and 19.6% of cases, respectively. A total of 24 procedures (9.0%) were unintentionally shifted to EFTR. The mean ± SD procedure time was 60.6 ± 44.5 minutes, which included a resection time of 45.3 ± 39.2 minutes and a closure time of 11.7 ± 11.0 minutes (

Table 2).

The R0 resection rate was 88.9%. Among the 28 patients who had R1 resection, 25 patients (89.3%) were with GISTs. Of these, 6 patients (24.0%) underwent surgical intervention, and 1 patient (4.0%) received adjuvant chemotherapy due to a high mitotic count risk. The remaining 18 patients (72.0%) were monitored with follow-up alone, which included endoscopy and CT scans every 6 to 12 months for the first 3 years, followed by annual surveillance until 5 years. Notably, none of the patients with R1 resection experienced recurrence during the follow-up period (Table A1).

The mean ± SD hospital stay was 5.0 ± 2.9 days. A total of 21 complications (6.3%) were recorded, with intra-procedural inadvertent perforation being the most common (15 patients, 4.5%), followed by delayed bleeding (2 patients, 0.6%). In total, 16 patients (4.8%) required surgery following the primary procedure. The complication rates for SELs smaller and larger than 20 mm were 3.8% and 17.7%, respectively (p = 0.001). Regarding mortality, one 81-year-old patient with a 2.8 cm GIST experienced microperforation with bleeding after ESSD and subsequently underwent surgery. Unfortunately, the patient passed away due to pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome one month later. Another patient with a 3.0 cm GIST died from underlying lung cancer after 5 years of follow-up. No recurrence was observed during the mean follow-up period of 921.4 ± 947.5 days.

3.3. Comparison Between Leiomyoma and GIST

We compared demographic data and outcomes between patients with GISTs and leiomyomas. In the univariate analysis, significant differences were observed in EUS features (irregular border, heterogeneous echotexture, and exophytic growth), sex, age, tumor located at fundus and EUS tumor size between the two groups (

Table 3). As for the outcomes, ER for GISTs had longer procedure time (71.3 ± 47.7 vs. 46.9 ± 37.1 minutes, p < 0.001), lower proportion of R0 resection (90.4% vs. 98%, p < 0.001), higher complication (7.9% vs. 2%, p = 0.027) and unintentional EFTR (12.5% vs. 0%) (

Table 3). We also analyzed predictors for higher risk group within GISTs. We compared demographic factors between very low risk GISTs and higher grade (low, intermediate and high) of GISTs. Larger size in both EUS (OR = 1.160, p < 0.001) and endoscopic (OR = 1.161, p < 0.001) size are related to higher grade of GISTs. EUS characteristics were not significantly associated with the grading of GISTs (

Table A2).

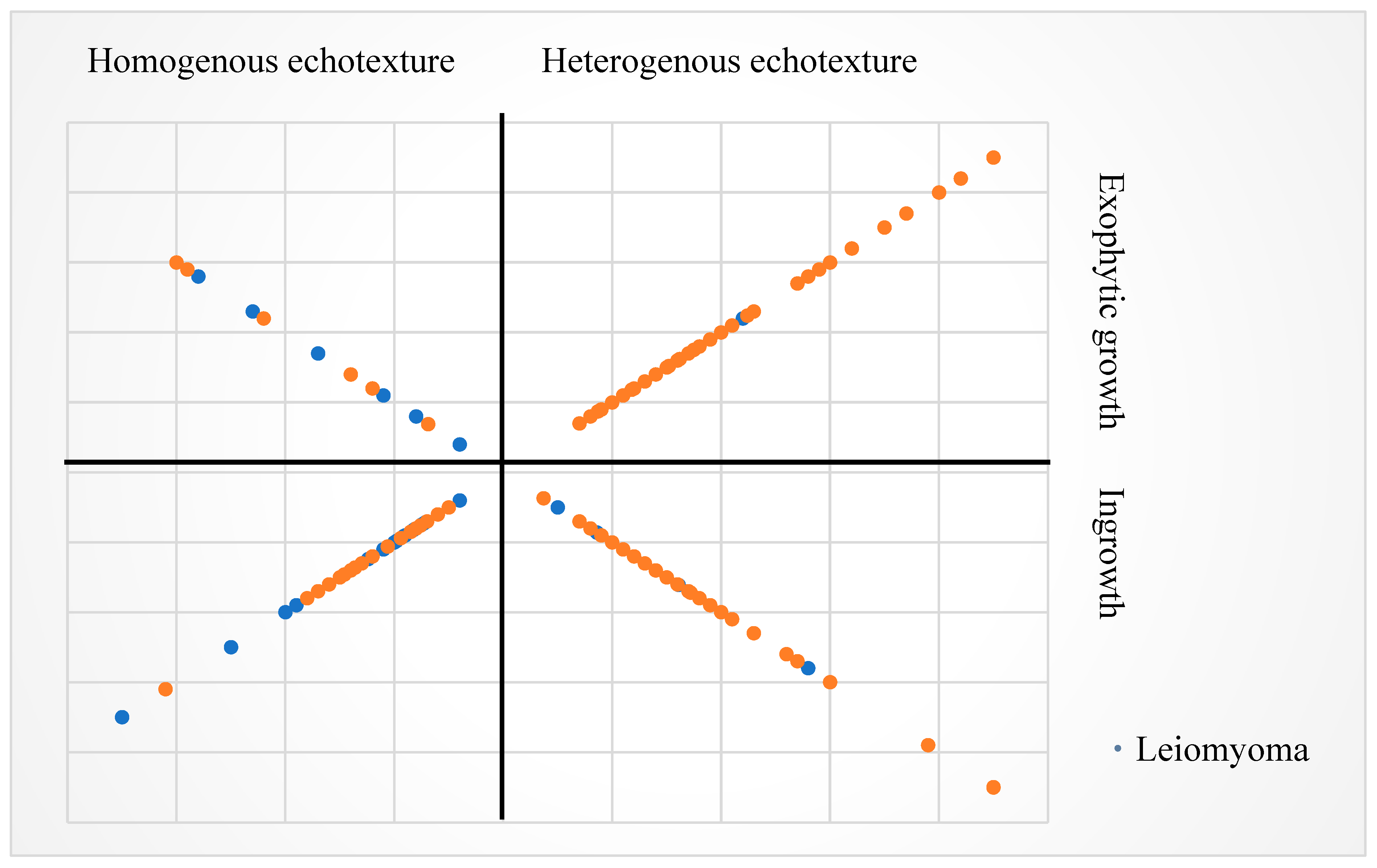

The distribution of EUS size and features is illustrated in

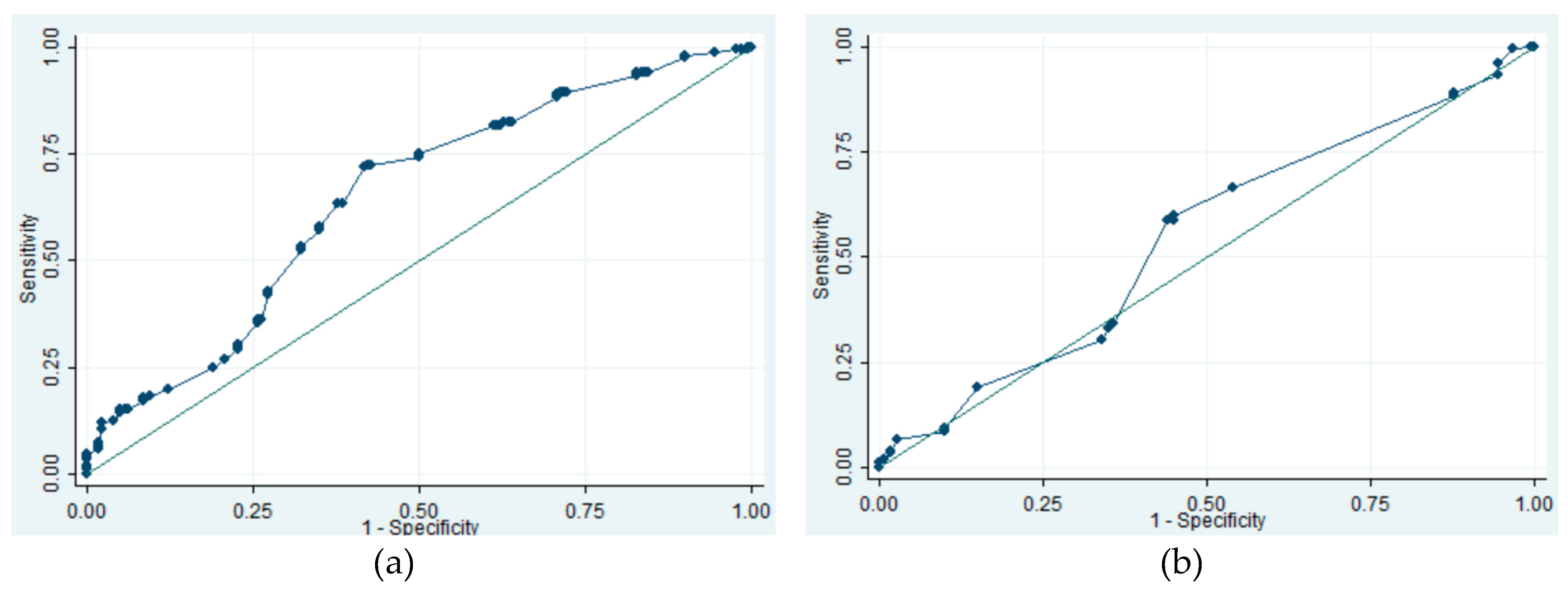

Figure A1. We also analyzed the threshold for continuous variable (tumor size and age) in prediction of GISTs. When using age 72 as the cutoff level, the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve (AUC) were 15.1%, 98.9% and 0.7329, respectively. For EUS size, a threshold of 12 mm resulted in a sensitivity of 71.7%, specificity of 58.3%, and AUC of 0.6471. In comparison, using endoscopic size threshold of 15 mm yielded sensitivity of 58.6%, specificity of 56.1%, and AUC of 0.5444 (

Figure A2 and A3).

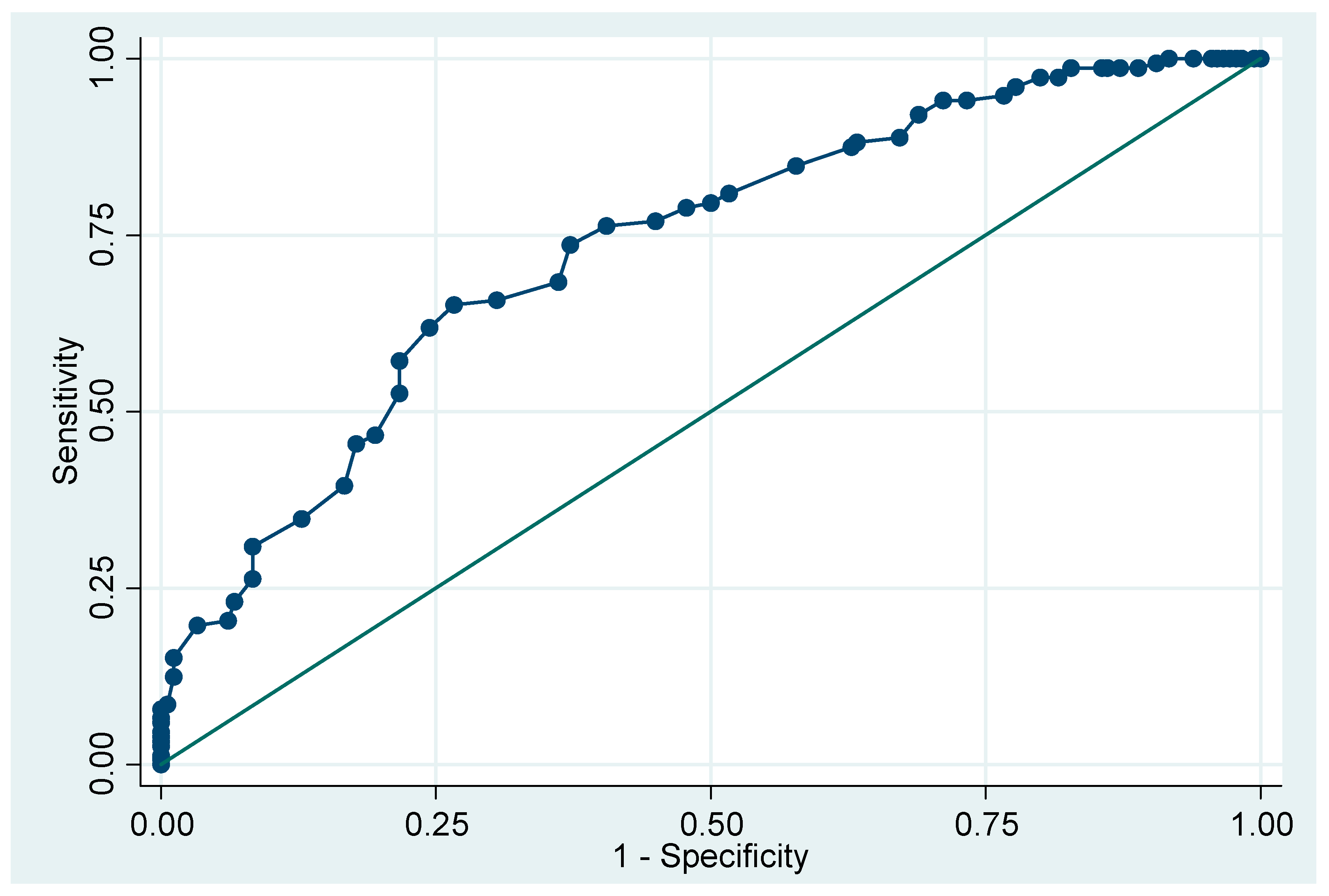

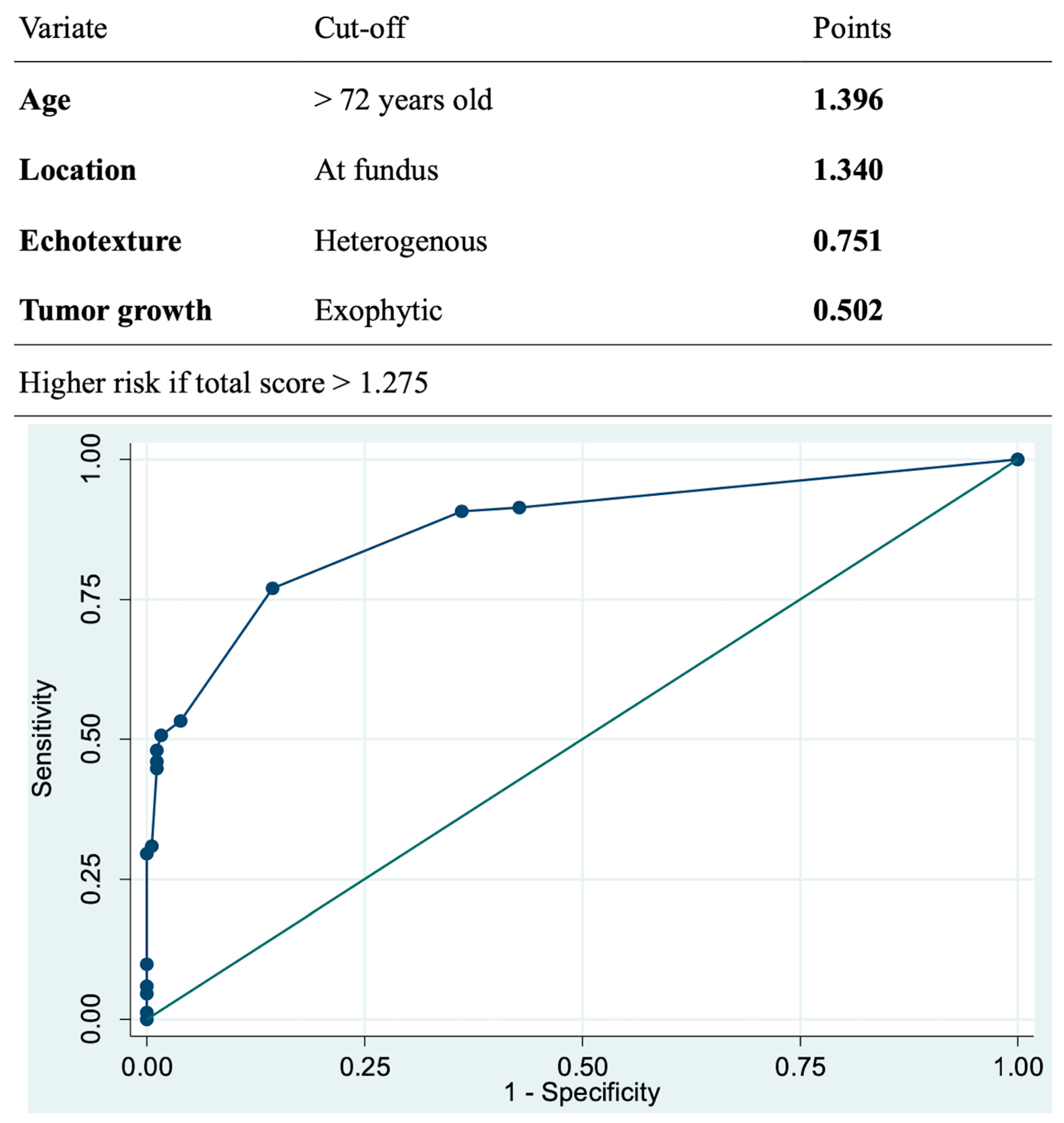

The multivariate analysis revealed that GISTs were more prevalent in elderly patients, fundus location, exhibiting heterogeneous echotexture and exophytic growth under EUS (

Table 4). Using the logarithm of odds ratio based on the multivariate analysis, we built-up a model to predict malignant potential of the SELs. This model could achieve sensitivity of 77.0%, specificity of 85.6%, and AUC of 0.8771 using threshold of total score 1.275 (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This retrospective study demonstrates ER being a valid and reliable strategy for the management of gastric SELs originating from MP layer, with high technical successful and en-bloc rates as well as low complication rate. In addition, EUS features, including heterogeneous echotexture and exophytic growth rather than the tumor size, could be used to predict malignant potential of gastric myogenic tumors. A model with factors of age, location at fundus, and EUS features aid in predicting malignant potential of gastric myogenic tumors.

The prevalence of GISTs is estimate to be 10 to 15 per 100,000 in general population and counts for up to 3% for malignancies in GI tract.[

14] The incidence of GISTs was reported as high as up to 2 per 100,000 in some literatures.[

15] The natural course of gastric SELs is still poorly understood, yet, about 8.4% of the lesions were found with enlargement during serial endoscopy follow up.[

2] Proportions with malignant potential within gastric SELs were reported in some studies around 23-34%.[

16] One cohort revealed that 35.1% small (i.e. less than 2 cm) gastric SELs were GISTs.[

17] In updated international guidelines, the malignant potential of GISTs was emphasized.[12, 18] World Health Organization (WHO) classified GIST as malignant tumor, disregarding location, tumor size and mitotic count.[

19] Within our cases, almost half (45.8%) of gastric SELs origin from MP layer are GISTs, even in smaller size. Resection of all gastric myogenic tumors disregarding tumor size, particularly in those with high risk EUS features should be taken into consideration as the appropriate initial management.

Resection is recommended as standard treatment for GISTs larger than 20 mm.[4, 18] In recent evidences, the ESGE guideline suggests that surveillance or resection are both acceptable in small (< 20 mm) proven GISTs in stomach.[

13] Nevertheless, ESMO guideline suggests complete excision of all GISTs regardless of size, and ER could be considered in small tumors to minimize morbidity.[

12] The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and ESGE guidelines also describe ER as alternatives therapy in gastric GISTs < 20 mm to avoid long-term surveillance.[4, 13] More evidences support ER in managing GISTs, due to shorter procedure time, better post operative recovery without increased of recurrence or complication compared with operation.[

20] Nevertheless, higher proportion of R1 resection in ER than surgery was observed, while this phenomenon was not relate to higher recurrence rate.[21, 22] In our study, the R0 resection rate is slightly lower than 90 % while there was no recurrence noted during the following up. We believed that the electrocauterization artifacts contributed to the pathological findings of R1 resection. As a result, there was no recurrence after such R1 resection rate. Another possible reason for low recurrence was that the predominance of lesions were very low-risk group GISTs in this study, which are characterized by slow growth rate. Complication rate for ER in GISTs was disclosed between 0% to 14.4%.[23, 24] Pneumoperitoneum was described about 10.6% in a large-scaled study of EFTR.[

25] However, perforation may not be seemed as severe adverse event if successful closure, especially in EFTR with intentional perforating gastric wall. Therefore, the true “complication” is hard to defined. The complication rate in our cohort is 6.3% while inadvertent perforation as the most common one. About one third of patients with perforation needed following operation while another two third patients underwent either intra-procedure needle decompression with successful endoscopic closure and conservative treatment with antibiotics. Two mortalities are recorded during follow up but none of them were related to the procedure or the tumor.

Advancements in techniques of ER beyond the submucosal layer provides alternative minimally-invasive treatment options for GISTs. EMD was found to have complete resection rate with 96% while some chance of perforation that could managed by endoscopic techniques.[

9] ESSD was reported to have similar complete resection, en-bloc rate and adverse event with EMD.[10, 26] The efficacy and safety of STER and EFTR for the management of gastric myogenic tumors were also proven.[

27] Either exposed and non-exposed EFTR were found to have technical success rate near 100% without major adverse events.[

11] One analysis compared EFTR with STER showed earlier enteric feeding and shorter stay after STER, while higher en-bloc rate in EFTR.[

28] It may be owe to the chance of breaching the tumor capsule when dissection in tunnel by STER. Total complication rate was 6.5% in the analysis and no different between these two procedures.[

24] Our study demonstrates high success and en-bloc rate using variant types of ER procedures. A total of 24 procedures are shifted to unintentional EFTR and 19 of them were with histology of GISTs. It may because of larger size and exophytic growth of GISTs. Regarding the EUS evaluation, heterogenous echotexture and exophytic growth under EUS may indicate higher risk of SELs with malignancy potential according to our analysis. EUS features for prediction of GISTs were conducted in multiple studies. A cohort found heterogeneity and marginal halo sign were more observed in GISTs while irregular border as well as cystic change under EUS didn’t reach significance difference.[

29] This is similar with our result that heterogenous echotexture was more important than irregular border. Another study with 138 patients with larger (mean size 34 mm) SELs revealed that non-smooth border, blurring of the layers, presence of blood flow or special inner structure, hypoechoic and heterogenous echotexture were related to histology of GISTs.[

30] As for correlation of EUS findings with risk stratification, one study suggested EUS features are not reliable for prediction and only tumor size related to mitotic count.[

31] The findings of our study were comparable to previous studies. Using ROC analysis, we found 15 mm for EUS size and 12 mm for endoscopic size were cut point for higher risk being SELs with malignant potential. Nevertheless, low AUC values were found in both groups. One study enrolled small SELs suspected GIST found lesion more than 9.5 mm had significant higher risk for tumor growth.[

32] The size to predict malignant potential of gastric myogenic tumor is still debatable. One study developed scoring system using CT and EUS features to differentiated GIST and schwannoma from leiomyoma, which tumor location and uneven echogenicity were also suggested as key factors.[

33]

There are some limitations in this study. First, this is a multicenter, retrospective study. Therefore, heterogenicity in determination of endoscopic procedures, including resection methods as well as closure techniques may occur. Secondly, the EUS images are evaluated by endoscopists at each study institute rather than central reading. Interobserver variations should be considered. Lastly, there is wide range of follow up periods of the patients. Recurrence in those patients with R1 resection of GISTs with lower risk may not be discernible during the study period.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, ER appears to be an efficient and safe method for precise histological assessment and for management of gastric myogenic tumor. Additionally, the malignant potential of gastric myogenic tumor could be predicted by EUS features as well as demographic characteristics. More researches on long-term data about the outcomes of patients with gastric myogenic tumors managed by ER is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of study: CTF, TYS, CSC. Acquisition of data: CTF, TYS WHH, HYC, CTL, MYC, CYL, WCT, SIS, ICC. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: CTF, CSC. Drafting the manuscript: CTF, CSC. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: CTF, TYS WHH, HYC, CTL, MYC, CYL, WCT, SIS, ICC, CSC. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published: CTF, TYS WHH, HYC, CTL, MYC, CYL, WCT, SIS, ICC, CSC.

Funding

The authors have no financial ties to disclose. This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Far Eastern Memorial Hospital (FEMH-109047-E, May 31, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Disclosure

Drs. Chih-Tsung Fan, Tze-Yu Shieh, Wen-Hung Hsu, Hsi-Yuan Chien, Ching-Tai Lee, Ming-Yao Chen, Chung-Ying Lee, Wei-Chen Tai, Sz-Iuan Shiu, I-Ching Cheng and Chen-Shuan Chung declare no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Abbreviations

| ACG |

American College of Gastroenterology |

| AUC |

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| EFTR |

Endoscopic full-thickness resection |

| EMD |

Endoscopic muscular dissection |

| ER |

Endoscopic resection |

| ESE |

Endoscopic submucosal excavation |

| ESGE |

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

| ESMO |

European Society for Medical Oncology |

| ESSD |

Endoscopic subserosal dissection |

| EUS |

Endoscopic ultrasound |

| GIST |

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| MIAB |

Mucosal incision-assisted biopsy |

| MP |

Muscularis propria |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SEL |

Subepithelial lesions |

| STER |

Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Lists of additional therapies among patients with GIST who had R1 resection.

Table A1.

Lists of additional therapies among patients with GIST who had R1 resection.

| Risk stratification of GIST |

Additional therapy |

Number |

| Very low risk |

No additional therapy |

14 |

| Operation |

4 |

| Low risk |

No additional therapy |

4 |

| High risk |

Operation |

2 |

| Chemotherapy |

1 |

Table A2.

Analyses of demographic data for prediction of staging of GIST: “Very low risk GISTs” versus “Not very low risk GISTs”*.

Table A2.

Analyses of demographic data for prediction of staging of GIST: “Very low risk GISTs” versus “Not very low risk GISTs”*.

| |

OR (95% CI) |

p value |

| Male sex |

0.693 (0.311-1.563) |

0.381 |

|

Age, year-old |

1.023 (0.985-1.063) |

0.233 |

|

Endoscopic tumor size, mm |

1.161 (1.094-1.232) |

<.001 |

|

EUS tumor size, mm |

1.160 (1.096-1.227) |

<.001 |

| EUS characteristic |

|

|

| Irregular border |

0.749 (0.334-1.680) |

0.482 |

| Heterogenous echotexture |

1.191 (0.443-3.204) |

0.728 |

| Exophytic growth |

1.016 (0.473-2.182) |

0.967 |

Figure A1.

Distribution of EUS size, echotexture and growth feature with histology. The larger size of the tumors is represented by the farther distance of the dots from the origin. EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Figure A1.

Distribution of EUS size, echotexture and growth feature with histology. The larger size of the tumors is represented by the farther distance of the dots from the origin. EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Figure A2.

The ROC curve of age for prediction of GIST, AUC 0.7329. ROC, receiver-operation characteristic; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; AUC, area under the curve.

Figure A2.

The ROC curve of age for prediction of GIST, AUC 0.7329. ROC, receiver-operation characteristic; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; AUC, area under the curve.

Figure A3.

The ROC curves of tumor size for prediction of GIST. (a) ROC curve of EUS tumor size. AUC 0.6471. (b) ROC curve of endoscopic tumor size. AUC 0.5444. ROC, receiver-operation characteristic; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; AUC, area under the curve.

Figure A3.

The ROC curves of tumor size for prediction of GIST. (a) ROC curve of EUS tumor size. AUC 0.6471. (b) ROC curve of endoscopic tumor size. AUC 0.5444. ROC, receiver-operation characteristic; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; AUC, area under the curve.

References

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.O. Management of gastric subepithelial tumors: The role of endoscopy. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 8, 418–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.-H.; A Yang, M.; Song, J.S.; Lee, W.D.; Cho, J.W. Prevalence and natural course of incidental gastric subepithelial tumors. Clin. Endosc. 2024, 57, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, F.; Ao, W.; Hu, H. Value of CT Imaging in the Differentiation of Gastric Leiomyoma From Gastric Stromal Tumor. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2020, 72, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, B.C.; Bhatt, A.; Greer, K.B.; Lee, L.S.; Park, W.G.; Sauer, B.G.; Shami, V.M. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Lesions. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 118, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, H.; Kitano, M.; Kudo, M. Diagnosis of subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J. Radiol. 2010, 2, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Kim, E.Y.; Cho, J.W.; Jeon, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, T.H.; Moon, J.S.; Kim, J.-O. the Research Group for Endoscopic Ultrasound of the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Predictive Factors for Differentiating Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors from Leiomyomas Based on Endoscopic Ultrasonography Findings in Patients with Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Clin. Endosc. 2021, 54, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.P.; Zhang, Y.P.; Li, Q.M. How to Approach Submucosal Lesions in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Different Ideas between China and USA. Gastroenterol. Res. Pr. 2022, 2022, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, Y.; Hwang, J.; Cirocco, M.; May, G.R.; Mosko, J.; Teshima, C.W. Efficacy of single-incision needle-knife biopsy for sampling subepithelial lesions. Endosc. Int. Open 2017, 05, E5–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.-R.; Song, J.-T.; Qu, B.; Wen, J.-F.; Yin, J.-B.; Liu, W. Endoscopic muscularis dissection for upper gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 3141–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Ren, W.; Yang, T.; Lv, Y.; Ling, T.; Zou, X.; Wang, L. The fourth space surgery: endoscopic subserosal dissection for upper gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 32, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Modayil, R.; Criscitelli, T.; Stavropoulos, S.N. Endoscopic resection for subepithelial lesions—pure endoscopic full-thickness resection and submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 39–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, P.; Blay, J.; Abecassis, N.; Bajpai, J.; Bauer, S.; Biagini, R.; Bielack, S.; Bonvalot, S.; Boukovinas, I.; Bovee, J.; et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO–EURACAN–GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, P.H.; Moons, L.M.; Oʼtoole, D.; Gincul, R.; Seicean, A.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Polkowski, M.; Vieth, M.; Borbath, I.; et al. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.P.; Heinrich, M.C. C.L. Corless, Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet 2007, 369(9574), 1731–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søreide, K.; Sandvik, O.M.; Søreide, J.A.; Giljaca, V.; Jureckova, A.; Bulusu, V.R. Global epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): A systematic review of population-based cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiology 2016, 40, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Xing, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, M. Feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors treatment and value of endoscopic ultrasonography in pre-operation assess and post-operation follow-up: a prospective study of 224 cases in a single medical center. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 4206–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.K.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Noh, D.S.; Jang, J.Y.; Baik, G.H.; Jang, S.; Vargo, J.; Cho, J.Y. Is it enough to observe less than 2 cm sized gastric SET? Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 6798–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, I.; Jones, R.L.; Wong, N.A.C.S.; Dileo, P.; Bulusu, R.; Smith, M.; Almond, M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST): British Sarcoma Group clinical practice guidelines. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 132, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

WHO Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th edition; 2020; Volume 3.

- Wang, C.; Gao, Z.; Shen, K.; Cao, J.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, K.; Wang, S.; Ye, Y. Safety and efficiency of endoscopic resection versus laparoscopic resection in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2020, 46, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, M.D.; Antonescu, C.R.; Ballman, K.V.; Maki, R.G.; Pisters, P.W.; Demetri, G.D.; Blanke, C.D.; von Mehren, M.; Brennan, M.F.; McCall, L.; et al. Microscopically Positive Margins for Primary Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Analysis of Risk Factors and Tumor Recurrence. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 215, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G. Interpretation of Pathologic Margin after Endoscopic Resection of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Clin. Endosc. 2016, 49, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, L.-Q.; Han, Z.-L.; Li, X.-F.; Wang, L.-H.; Liu, S.-D. Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for gastric GISTs: a systematic review. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2017, 27, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.W.Y.; Yip, H.C.; Chan, S.M.; Ng, S.K.K.; Teoh, A.Y.B.; Ng, E.K.W. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) compared to submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection (STER) for treatment of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 11, E179–E186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ni, M.; Jiang, J.; Ren, X.; Zhu, T.; Cao, S.; Hassan, S.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; et al. Comparison of endoscopic full-thickness resection and cap-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection in the treatment of small (≤1.5 cm) gastric GI stromal tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 660–670.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cho, J.; Song, J.; Yang, M.; Lee, Y.; Ju, M. Endoscopic subserosal dissection for gastric tumors: 18 cases in a single center. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 8039–8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y. The Outcome of Snare-Assisted Traction Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection for the Gastric Fundus Submucosal Tumors Originating from the Muscularis Propria. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2024, 34, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Yao, Y.; Shi, K.; Yu, M.; Ji, F. Resection of the gastric submucosal tumor (G-SMT) originating from the muscularis propria layer: comparison of efficacy, patients’ tolerability, and clinical outcomes between endoscopic full-thickness resection and surgical resection. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 4053–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaicekauskas, R.; Urbonienė, J.; Stanaitis, J.; Valantinas, J. Evaluation of Upper Endoscopic and Endoscopic Ultrasound Features in the Differential Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors and Leiomyomas in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. Visc. Med. 2019, 36, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F. Endoscopic ultrasonographic features of submucosal lesions of upper digestive tract suspected gastrointestinal stromal tumors and their correlation with progression and pathological risk grade of the lesions. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2023, 103(21), 1643–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Seven, G.; Arici, D.S.; Senturk, H. Correlation of Endoscopic Ultrasonography Features with the Mitotic Index in 2- to 5-cm Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Dig. Dis. 2021, 40, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, C.; Xue, Q.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, K.; Shen, K.; Liang, B.; Yang, X.; Xie, Q.; et al. The cut-off value of tumor size and appropriate timing of follow-up for management of minimal EUS-suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okanoue, S.; Iwamuro, M.; Tanaka, T.; Satomi, T.; Hamada, K.; Sakae, H.; Abe, M.; Kono, Y.; Kanzaki, H.; Kawano, S.; et al. Scoring systems for differentiating gastrointestinal stromal tumors and schwannomas from leiomyomas in the stomach. Medicine 2021, 100, e27520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).